Abstract

Background

Early-onset rectal cancer (EORC) is characterized by a unique disease process with different clinicopathological features compared with late-onset rectal cancer (LORC). Research on the risk of recurrence in EORC patients, however, is limited. We aim to develop a predictive model to accurately predict EORC recurrence risk.

Materials and methods

Rectal cancer patients who underwent radical surgery and T2-weighted imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were retrospectively enrolled from three medical institutions from November 2012 to November 2018. Differences in clinicopathological characteristics between EORC and LORC were compared. Five prediction models for disease-free survival were constructed based on clinicopathological variables and five radiomic features from pretreatment MRI of the EORC. A fixed cut-off value calculated in the training set was used to stratify EORC patients into high-risk and low-risk groups of post-operative recurrence. Model performance was evaluated by concordance index (C-index) and receiver operating characteristic curve.

Results

A total of 264 EORC patients (median age, 43 years, 163 males) and 778 LORC patients (median age, 62 years, 520 males) were enrolled. Pretreatment positive carcinoembryonic antigen [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.84, P = 0.006], pathological positive lymph node status (pN positive) [HR = 2.86, P = 0.011] and MRI-based radiomics score [HR = 2.72, P < 0.001] are independent risk factors for disease-free survival in EORC patients. The EORC-ClinPathRadiom model, constructed by integrating the clinicopathological characteristics and MRI-based radiomics features of EORC, showed C-index of 0.82, 0.82, and 0.81 in the training, internal, and external test sets, respectively. This model effectively stratified EORC patients into high risk and low risk of recurrence (HRs for the training, internal, and external test sets were 8.96, 6.81, and 7.46, respectively).

Conclusion

The EORC-ClinPathRadiom model can effectively predict and stratify the risk of post-operative recurrence in EORC patients.

Key words: rectal cancer, early-onset, recurrence, magnetic resonance imaging, radiomics

Highlights

-

•

Pretreatment positive CEA and positive pN are independent risk factors for DFS in patients with EORC.

-

•

EORC patients had a lower rate of pretreatment positive CEA, and those with positive CEA had a higher recurrence risk.

-

•

The EORC-ClinPathRadiom model showed excellent predictive performance for DFS and effectively stratified EORC patients.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide. Although improvements in screening methods and treatment strategies have led to an overall decrease in the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer,1,2 the incidence and mortality of early-onset rectal cancer (EORC, i.e. cancer diagnosed before the age of 50 years) have increased by approximately 2% and 1.2% per year, respectively,1, 2, 3 posing a significant public health challenge. EORC has been shown to have different clinicopathological and molecular characteristics compared with late-onset rectal cancer (LORC, i.e. cancer diagnosed after the age of 50 years),1,4 which is more common in the distal colon and rectum,5,6 advanced disease stage,7 and unfavorable histopathological features, such as perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, poor differentiation, mucinous adenocarcinoma or signet ring cell carcinoma, all of which are associated with worse outcomes.8 In addition, patients with EORC are more likely to receive additional neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies beyond guideline recommendations,9 but have no greater survival benefit than patients with LORC who receive less therapy.9, 10, 11 As a result, some clinicians have questioned the appropriateness of overtreating patients with low-risk EORC. How to effectively guide the treatment of EORC patients is a challenging problem in clinical practice. The TNM (tumor–node–metastasis) staging system for tumor (T), lymph node (N), and metastasis (M) is the main basis for guiding treatment decisions. Guidelines, such as the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO, Europe), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN, USA), and others, however, do not provide targeted solutions for the management and evaluation of patients with EORC.12,13 Therefore, finding more accurate ways to identify patients with high-risk EORC is essential to prevent overtreatment.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the first-line imaging modality for rectal cancer (RC). T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), to some extent, can reflect the differences in tumor tissue components such as water content and fibrosis. High b-value DWI can reflect the differences in tumor tissue structure due to the diffuse motion of water molecules. In addition, MRI-based radiomics can better reflect the tumor tissue structure and biological characteristics through high-throughput extraction and quantification of image features.14,15 These MRI-based radiomics models have been applied to the diagnosis, staging, response assessment, and prognostic prediction of RC.16, 17, 18, 19 Unfortunately, existing RC radiomics models are based on MRI data of all RC patients,18,20, 21, 22 and specific MRI radiomics models for the evaluation and screening of patients with EORC are lacking.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the following aspects using radiomics methods based on MRI T2WI and DWI images: (i) to compare the differences in clinicopathological characteristics between patients with EORC and LORC, and to analyze the risk factors affecting post-operative recurrence of EORC; (ii) to develop and evaluate postoperative recurrence prediction models for EORC patients, hoping to effectively screen high-risk EORC, thereby providing more decision support for individualized and precise treatment plans.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients who underwent radical rectal surgery between November 2012 and November 2018 were collected from three medical institutions (institution 1: The Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University; institution 2: The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University; institution 3: Yunnan Cancer Hospital, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University). Inclusion criteria were: (i) histopathologically confirmed primary rectal adenocarcinoma; (ii) no treatments such as neoadjuvant radiation and chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy, etc. before baseline MRI examination; (iii) MRI sequences including T2WI and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), b value ≥800 s/mm2. Exclusion criteria were the following: (i) poor imaging quality; (ii) distant metastasis before surgery; (iii) history of other malignancies; (iv) complete bowel obstruction; (v) mucinous adenocarcinoma or signet ring cell carcinoma. The study flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. EORC, early-onset rectal cancer; LORC, late-onset rectal cancer. MR, magnetic resonance.

This multicenter retrospective study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees of institution 1 (2023ZSLYEC-109), institution 2 (II2023-115-01), and institution 3 (KYCS2021189), and the requirement for informed consent was waived in all the three institutions. This study was designed under the Transparent Reporting of Multivariable Prediction Models for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) guidelines.23

The clinical and pathological data

EORC is defined as RC in patients younger than 50 years of age, and LORC is defined as in patients 50 years of age and older.3,4 Clinical and pathological characteristics were collected. Detailed characteristics are shown in Table 1. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) were collected within 2 weeks before treatment. CEA levels <5 ng/ml were defined as negative, and ≥5 ng/ml as positive.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinicopathological characteristics between EORC and LORC

| Characteristics | All N = 1042 | EORC N = 264 | LORC N = 778 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agea, years | 58.00 [49.00-66.00] | 43.00 [37.00-46.00] | 62.00 [57.00-68.00] | <0.001∗ |

| Gender | 0.153 | |||

| Female | 359 (34.45) | 101 (38.26) | 258 (33.16) | |

| Male | 683 (65.55) | 163 (61.74) | 520 (66.84) | |

| BMIa | 22.60 [20.73-24.75] | 22.68 [20.54-24.73] | 22.58 [20.78-24.75] | 0.898 |

| Location | 0.076 | |||

| Upper | 153 (14.68) | 28 (10.61) | 125 (16.07) | |

| Mid | 495 (47.50) | 127 (48.11) | 368 (47.30) | |

| Low | 394 (37.81) | 109 (41.29) | 285 (36.63) | |

| Clinical stage | 0.190 | |||

| I | 147 (14.11) | 32 (12.12) | 115 (14.78) | |

| II | 313 (30.04) | 72 (27.27) | 241 (30.98) | |

| III | 582 (55.85) | 160 (60.61) | 422 (54.24) | |

| cT stage | 0.415 | |||

| ≤T2 | 185 (17.75) | 42 (15.91) | 143 (18.38) | |

| >T2 | 857 (82.25) | 222 (84.09) | 635 (81.62) | |

| cN stage | 0.066 | |||

| Negative | 467 (44.82) | 105 (39.77) | 362 (46.53) | |

| Positive | 575 (55.18) | 159 (60.23) | 416 (53.47) | |

| Pretreatment CEA | 0.021∗ | |||

| Negative | 626 (62.79) | 174 (69.05) | 452 (60.67) | |

| Positive | 371 (37.21) | 78 (30.95) | 293 (39.33) | |

| Pretreatment CA19-9 | 0.542 | |||

| Negative | 867 (87.31) | 215 (86.00) | 652 (87.75) | |

| Positive | 126 (12.69) | 35 (14.00) | 91 (12.25) | |

| Differentiation | 0.005∗ | |||

| Well/moderately | 865 (97.30) | 198 (94.29) | 667 (98.23) | |

| Poor/undifferentiated | 24 (2.70) | 12 (5.71) | 12 (1.77) | |

| pT stage | 0.698 | |||

| ≤T2 | 402 (38.58) | 105 (39.77) | 297 (38.17) | |

| >T2 | 640 (61.42) | 159 (60.23) | 481 (61.83) | |

| pN stage | 0.165 | |||

| Negative | 728 (69.87) | 175 (66.29) | 553 (71.08) | |

| Positive | 314 (30.13) | 89 (33.71) | 225 (28.92) | |

| pTNM | 0.155 | |||

| 0/I | 357 (34.29) | 93 (35.23) | 264 (33.98) | |

| II | 371 (35.64) | 82 (31.06) | 289 (37.19) | |

| III | 371 (35.64) | 89 (33.71) | 224 (28.83) | |

| LVI | 0.757 | |||

| Negative | 884 (92.86) | 225 (92.21) | 659 (93.08) | |

| Positive | 68 (7.14) | 19 (7.79) | 49 (6.92) | |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 0.003∗ | |||

| No | 585 (56.14) | 127 (48.11) | 458 (58.87) | |

| Yes | 457 (43.86) | 137 (51.89) | 320 (41.13) | |

| Adjuvant therapy | <0.001∗ | |||

| No | 419 (40.21) | 73 (27.65) | 346 (44.47) | |

| Yes | 623 (59.79) | 191 (72.35) | 432 (55.53) | |

| Local recurrence | 0.516 | |||

| No | 976 (93.67) | 250 (94.70) | 726 (93.32) | |

| Yes | 66 (6.33) | 14 (5.30) | 52 (6.68) | |

| Distant metastasis | 0.680 | |||

| No | 836 (80.23) | 209 (79.17) | 627 (80.59) | |

| Yes | 206 (19.77) | 55 (20.83) | 151 (19.41) | |

| Total recurrence | >0.999 | |||

| No | 806 (77.35) | 204 (77.27) | 602 (77.38) | |

| Yes | 236 (22.65) | 60 (22.73) | 176 (22.62) | |

| DFSa | 63.60 [34.44-74.95] | 64.85 [38.30-75.93] | 63.17 [33.38-74.72] | 0.298 |

Unless stated otherwise, data are numbers of patients, with percentages in parentheses. P values represent the comparison of clinicopathologic variables between two groups.

BMI, body mass index; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; cN stage, clinical nodal stage; cT stage, clinical tumor stage; DFS, disease-free survival; EORC, early-onset rectal cancer; LORC, late-onset rectal cancer; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; pN stage, pathological nodal stage; pT stage, pathological tumor stage; pTNM, pathological TNM stage.

Data are medians, with IQRs in parentheses.

P value was <0.05 and considered statistically significant.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was disease-free survival (DFS), defined as the time between radical resection of RC and local recurrence, distant metastasis, death from any cause, or the last date of follow-up. A definitive diagnostic approach to determine local recurrence or distant metastases is based on the appearance of new lesions on computed tomography, MRI, or positron emission tomography images and/or histological confirmation on biopsy.24 Patients were followed post-operatively every 3-6 months for the first 2 years and every 6 months after that. Routine visits included medical history, physical examination, and measurement of serum CEA and CA19-9 levels. Chest and abdominal CT were scheduled every 6-12 months for the first 5 years.

MRI protocol and image segmentation

Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735, summarizes the detailed MRI protocols used by the three institutions. T2WI and DWI imaging data were collected from all patients. Three-dimensional tumor regions of interest (ROI) were determined by two board-certified radiologists (TX, with 5 years of experience in rectal MRI, and JY Zhu, with 8 years of experience in rectal MRI) using ITK-SNAP software (version 3.8.0, www.itksnap.org). ROIs were delineated along the tumor contour, taking care to avoid intestinal gas, fat around the intestinal wall, necrotic tumor tissue, tumor blood vessels, etc. All segmentations were confirmed by another senior board-certified radiologist (PY Xie, with 10 years of experience in rectal MRI). Disagreements were resolved by consensus-based discussion. All three radiologists were blinded to the clinicopathological information and the prognosis of the patients. Thirty-five rectal lesions were randomly selected for tumor segmentation to analyze interobserver reproducibility.

Radiomics analysis

Dataset

To build the EORC prediction model, 223 EORC patients in institution 1 were divided into two groups according to the time of surgery: patients who underwent MRI from November 2012 to December 2015 were included in the training set (n = 158), and patients who underwent MRI from January 2016 to April 2018 were classified into the internal test set (n = 65). The external test set included patients who underwent surgery in institutions 2 and 3 (n = 41) (Figure 1).

Feature extraction

The IBSI-compliant Pyradiomics software package (version 3.0.1, https://pyradiomics.readthedocs.io/en/latest/) was used for image preprocessing and feature extraction.25 Before feature extraction, z-score normalization of MRI signal intensities for T2WI and DWI, gray level discretization with a fixed bin width of 5, and voxel size resampling of 1 × 1 × 1 mm were carried out to reduce image noise and differences between images. Some 1218 radiomics features (14 shape features, 18 first-order features, 22 glcm features, 16 glrlm features, 16 glszm features, 14 gldm features, 430 log transform features, 688 wavelets transform features) were extracted from each three-dimensional ROI of T2WI and DWI sequence images, resulting in a total of 2436 extracted features.

Feature selection and model construction

First, after performing mean-variance normalization of all features, a three-step feature selection including repeatability analysis, univariate prognostic analysis and correlation analysis was carried out on all EORC features to select radiomics features with prognostic value (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Radiomics pipeline for predicting DFS in patients with EORC. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; DFS, disease-free survival; EORC, early-onset rectal cancer; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; ROC, receiver operating characteristic curve.

Then, five multivariable models were developed and compared based on radiomics features of pretreatment MRI and clinicopathological variables of EORC patients: (1) pTNM model was constructed based on postoperative pathological TNM staging; (2) EORC-ClinPath model was based on the pretreatment clinical and postoperative pathological variables of EORC; (3) EORC-Radiom model was developed based on radiomics score calculated from final selected radiomics features of pretreatment MRI; (4) EORC-ClinRadiom model was developed based on the radiomics features and pretreatment clinical variables; (5) EORC-ClinPathRadiom model included data from both pretreatment clinical and postoperative pathological variables and radiomics features of pretreatment MRI.

Model assessment and comparison

Correlations between selected radiomics features and clinicopathologic variables were investigated using Spearman correlation coefficients. The optimal threshold in the training set was used to classify EORC patients into high-risk and low-risk groups. The association of risk groups with DFS was evaluated using Kaplan–Meier analysis, and the log-rank test was used to assess the survival difference. For patients with the same clinical stage, subgroup analysis was carried out to stratify EORC patients into high-risk and low-risk groups, respectively. The predictive performance was assessed using Harrell’s concordance index (C-index) and receiver operating characteristic curve analysis at each time point (1, 3, 5 years). The DeLong test was carried out to compare the areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUCs) of different models. Calibration curves were used to measure predictive accuracy, while decision curve analysis was used to assess clinical utility. Net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) values were used to quantify improvements in prognostic utility.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean (mean ± standard deviation) or medians (quartiles); categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages). Differences in continuous variables (age, BMI, DFS) were compared using the t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. Statistical analysis was carried out using R software (version 4.2.2, http://www.R-project.org) and SPSS software (version 25.0, IBM). The R package is shown in Supplementary Material Appendix A1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735, and the code is available on github (https://github.com/ZM50149/Radiomics-EORC). A P value <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinicopathological difference between EORC and LORC

A total of 1042 patients were included in this study, including 264 EORC patients {median age, 43 years [interquartile range (IQR), 37-46 years], 163 males} and 778 LORC patients [median age, 62 years (IQR, 57-68 years), 520 males]. There was no difference in body mass index (BMI), tumor location, clinical stage, clinical T stage, clinical N stage, pretreatment CA19-9, pathological T stage, pathological N stage, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), DFS, and overall recurrence rate between LORC and EORC (all P > 0.05, Table 1). Compared with the LORC group, the EORC group had a significantly lower proportion of patients with pretreatment positive CEA (P = 0.021) and a significantly higher proportion of poorly differentiated or undifferentiated tumors (P = 0.005). And the EORC patients also received more neoadjuvant (P = 0.003) and adjuvant (P < 0.001) therapy. In addition, there were no significant differences in age, gender, and recurrence rate among the training, internal test, and external test sets of EORC patients (all P > 0.05, Supplementary Table S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735).

MRI-based EORC-Radiom model

We screened five features from the pretreatment MRI radiomics features based on the EORC patients and developed the EORC-Radiom model. The contribution of the five selected radiomics features to EORC-Radiom is shown in Supplementary Figure S1A, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735. The selected radiomics features were not highly correlated with the clinicopathological variables of the patients (Supplementary Figure S1B, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735). All the C-indexes of the EORC-Radiom model for predicting DFS in EORC patients in the training set, internal and external test sets were 0.71 (C-index: training set, 0.71; internal test set, 0.71; external test set, 0.71) (Table 3). Based on the optimal threshold obtained in the training set, EORC patients were divided into two groups: those with high risk of recurrence (rad-score ≥0.475) and those with low risk of recurrence (rad-score <0.475). The Kaplan–Meier survival curve confirmed a significant difference in DFS between the patients with high-risk and low-risk EORC not only in all EORC patients [hazard ratios (HRs) in the training set, internal and external test sets were 3.93, 4.93, and 6.81, respectively] (Supplementary Figure S2D-F, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735), but also in the subgroups of patients with stage 0/I and stage II/III EORC (Supplementary Figure S2G-L, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735).

Table 3.

The C-index values of the models in the training and test sets

| Data Set | pTNM | EORC-ClinPath | EORC-Radiom | EORC-ClinRadiom | EORC-ClinPathRadiom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | 0.69 [0.62-0.76]a,b | 0.71 [0.62-0.79]a,b | 0.71 [0.64-0.79]a,b | 0.77 [0.70-0.85]b | 0.82 [0.75-0.88] |

| Internal test set | 0.63 [0.50-0.76]a,b | 0.75 [0.63-0.87]a,b | 0.71 [0.61-0.82]a,b | 0.81 [0.71-0.92] | 0.82 [0.74-0.91] |

| External test set | 0.61 [0.38-0.84]a,b | 0.72 [0.49-0.95] | 0.71 [0.54-0.89]b | 0.77 [0.60-0.94] | 0.81 [0.63-0.99] |

Data in the brackets are 95% CI.

C-index, concordance index; CI, confidence interval; EORC, early-onset rectal cancer; pTNM, pathological TNM stage.

The EORC-ClinRadiom model outperformed the corresponding model (P < 0.05 and considered statistically significant).

The EORC-ClinPathRadiom model outperformed the corresponding model (P value <0.05 and considered statistically significant).

Risk factors in EORC

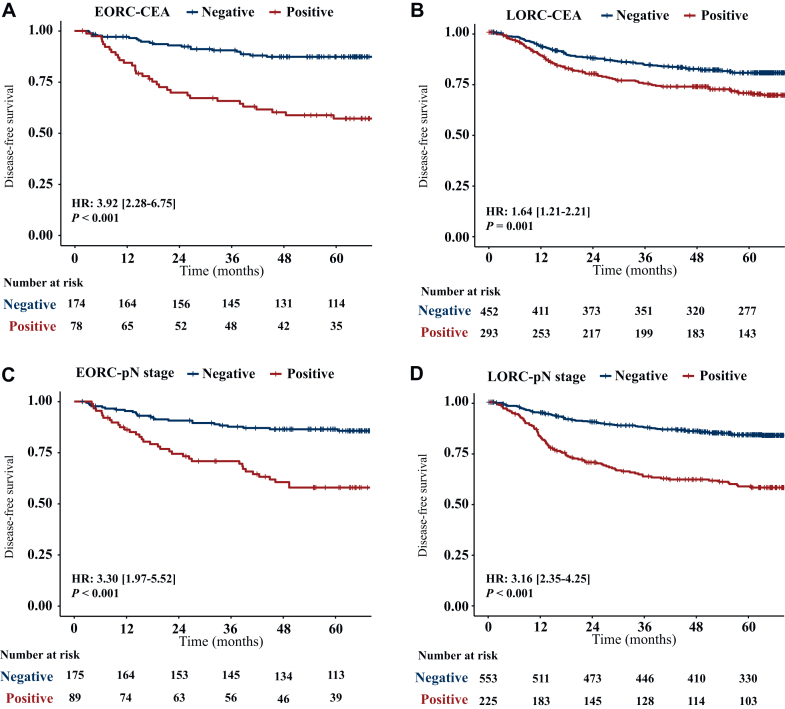

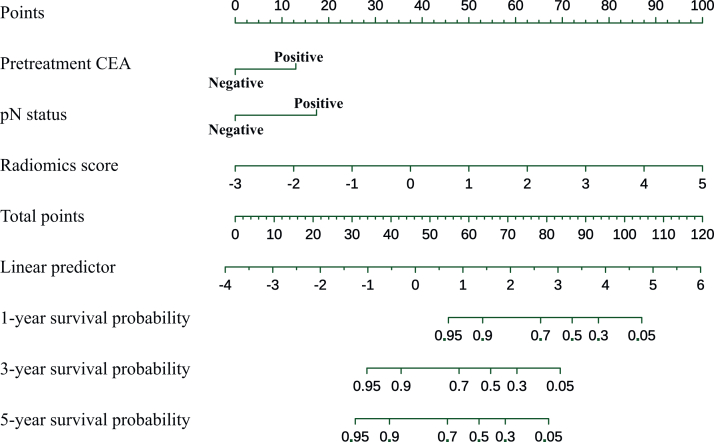

Univariate analysis showed that pretreatment positive CEA, pathologically confirmed poorly differentiated or undifferentiated tumors, T stage greater than T2 (pT >2) and positive lymph node status (pN positive) were significantly associated with post-operative recurrence in EORC patients. Multivariate analysis confirmed that pretreatment positive CEA (HR = 2.84, P = 0.006) and positive pN (HR = 2.86, P = 0.011) were independent risk factors for DFS in EORC patients (Table 2). Kaplan–Meier curves showed shorter DFS in both EORC and LORC patients with pretreatment positive CEA than in those with negative CEA {in EORC patients: HR = 3.92 [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.28-6.75], P < 0.001; in LORC patients: HR = 1.64 [95% CI 1.21-2.21], P = 0.001) (Figure 3A and B). And the HR of recurrence for positive pN status was significantly higher than that for negative pN status in both EORC patients [HR = 3.30 (95% CI 1.97-5.52), P < 0.001] and LORC patients [HR = 3.16 (95% CI 2.35-4.25), P < 0.001] (Figure 3C and D). In patients with pretreatment negative CEA, Kaplan–Meier curves showed longer DFS in EORC patients than in LORC patients (HR = 0.62, P = 0.045); whereas in patients with pretreatment positive CEA, Kaplan–Meier curves showed shorter DFS in EORC patients than in LORC patients (HR = 1.49, P = 0.053) (Supplementary Figure S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735). Moreover, univariate analysis showed that MRI-based radiomics scores [HR = 2.72 (95% CI 1.93-3.84), P < 0.001] was an independent predictor of tumor recurrence in EORC patients (Table 2). By incorporating the above independent predictors of DFS in EORC patients, including radiomics features, pretreatment CEA and pathological lymph node status, the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model was developed and presented as a nomogram (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the correlation between clinico-pathological characteristics and DFS in EORC patients

| Characteristic | Univariate cox regression |

Multivariate cox regression |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR [95% CI] | P value | HR [95% CI] | P value | |

| Age | 1.01 [0.96-1.07] | 0.693 | ||

| Gender male | 0.88 [0.46-1.68] | 0.692 | ||

| BMI | 0.97 [0.88-1.08] | 0.603 | ||

| Location mid | 0.62 [0.32-1.20] | 0.152 | ||

| Location upper | 0.47 [0.11-2.02] | 0.312 | ||

| Clinical stage I | 1.01 [0.96-1.07] | 0.693 | ||

| Clinical stage II | 0.88 [0.46-1.68] | 0.692 | ||

| cT >T2 | 0.83 [0.38-1.81] | 0.643 | ||

| cN positive | 1.03 [0.54-1.97] | 0.932 | ||

| Pretreatment CEA positive | 3.18 [1.65-6.13] | 0.001∗ | 2.84 [1.35-5.99] | 0.006∗ |

| Pretreatment CA19-9 positive | 1.99 [0.87-4.54] | 0.103 | ||

| Differentiation poor/undifferentiated | 4.22 [1.46-12.15] | 0.008∗ | 2.39 [0.79-7.21] | 0.122 |

| pT >T2 | 2.35 [1.16-4.73] | 0.017∗ | 1.52 [0.54-4.26] | 0.423 |

| pN positive | 3.75 [1.97-7.11] | <0.001∗ | 2.86 [1.28-6.38] | 0.011∗ |

| LVI positive | 1.30 [0.40-4.23] | 0.663 | ||

| Neoadjuvant therapy yes | 1.03 [0.54-1.98] | 0.928 | ||

| Adjuvant therapy yes | 0.87 [0.42-1.79] | 0.700 | ||

| MRI-based radiomics score | 2.72 [1.93-3.84] | <0.001∗ | ||

BMI, body mass index; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CI, confidence interval; cN stage, clinical nodal stage; cT stage, clinical tumor stage; DFS, disease-free survival; EORC, early-onset rectal cancer; HR, hazard ratio; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; pN stage, pathological lymph node stage; pT stage, pathological tumor stage.

P value was <0.05 and considered statistically significant.

Figure 3.

DFS in EORC and LORC patients with negative versus positive pretreatment CEA (A and B) and pN status (C and D).P value was calculated using a two-sided log-rank test. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; DFS, disease-free survival; EORC, early-onset rectal cancer; HR, hazard ratio; LORC, late onset rectal cancer; pN, pathological lymph node stage.

Figure 4.

The EORC-ClinPathRadiom for predicting DFS in patients with EORC. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; DFS, disease-free survival; EORC, early-onset rectal cancer; pN, pathological lymph node stage.

Prediction model construction and model performance evaluation

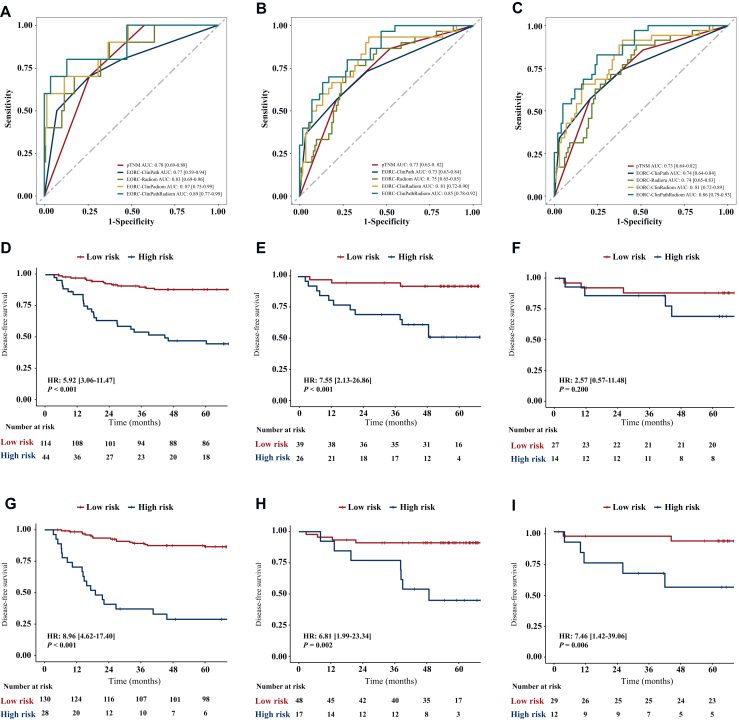

The predictive performances of the five prediction models including pTNM, EORC-ClinPath, EORC-Radiom, EORC-ClinRadiom, and EORC-ClinPathRadiom are shown in Table 3. The predictive performance of the EORC-Radiom model is comparable to that of the EORC-ClinPath model (C-index in: training set 0.71 versus 0.71, P = 0.535; internal test set 0.71 versus 0.75, P = 0.090; external test set 0.71 versus 0.72, P = 0.891). The C-index of the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model was significantly higher than that of the EORC-ClinRadiom model in the training set [0.82 (95% CI 0.75-0.88) versus 0.77 (95% CI 0.70-0.85), P < 0.001] and had no significant difference in the internal and external test sets [internal test set: 0.82 (95% CI 0.74-0.91] versus 0.81 (95% CI 0.71-0.92), P = 0.753; external test set: 0.81 (95% CI 0.63-0.99] versus 0.77 [95% CI 0.60-0.94], P = 0.345) (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735). The AUCs of the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model at 1, 3, and 5 years were slightly higher than those of the EORC-ClinRadiom model at 1 year (training set 0.89 versus 0.87; internal test set 0.76 versus 0.84; external test set 0.79 versus 0.77), 3 years (training set 0.85 versus 0.81; internal test set 0.79 versus 0.83; external test set 0.81 versus 0.74), and 5 years (training set 0.86 versus 0.81, internal test set 0.86 versus 0.90; external test set 0.86 versus 0.81) (Figure 5A-C and Table 4).

Figure 5.

The receiver operating characteristic curves and Kaplan–Meier curves of the models. Data in the brackets are 95% CI. (A-C) AUCs of the models for predicting DFS in the training set at 1 year (A), 3 years (B), and 5 years (C). (D-I) Kaplan–Meier curves of DFS prediction by the EORC-ClinRadiom model (D-F) and EORC-ClinPathRadiom model (G-I) in the training set (D and G), internal test set (E and H) and external test set (F and I). P value was calculated using a two-sided log-rank test. AUC, area under the curve; DFS, disease-free survival; EORC, early-onset rectal cancer; HR, hazard ratio; pTNM, pathological TNM stage.

Table 4.

AUC values of the models in the training and test sets

| Data set | Parameter | pTNM | EORC-ClinPath | EORC-Radiom | EORC-ClinRadiom | EORC-ClinPathRadiom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | 1-Year AUC | 0.78 [0.69-0.88] | 0.77 [0.59-0.94] | 0.83 [0.69-0.96] | 0.87 [0.75-0.99] | 0.89 [0.77-0.99] |

| 3-Year AUC | 0.73 [0.63-0.82] | 0.73 [0.63-0.84] | 0.75 [0.65-0.85] | 0.81 [0.72-0.90] | 0.85 [0.78-0.92] | |

| 5-Year AUC | 0.73 [0.64-0.82] | 0.74 [0.64-0.84] | 0.74 [0.65-0.83] | 0.81 [0.72-0.89] | 0.86 [0.79-0.93] | |

| Internal test set | 1-Year AUC | 0.47 [0.09-0.85] | 0.66 [0.38-0.94] | 0.67 [0.52-0.83] | 0.84 [0.74-0.95] | 0.76 [0.62-0.91] |

| 3-Year AUC | 0.57 [0.36-0.77] | 0.68 [0.52-0.85] | 0.70 [0.55-0.85] | 0.83 [0.67-0.98] | 0.79 [0.66-0.92] | |

| 5-Year AUC | 0.58 [0.38-0.77] | 0.72 [0.54-0.91] | 0.89 [0.78-0.99] | 0.90 [0.80-0.99] | 0.86 [0.73-0.99] | |

| External test set | 1-Year AUC | 0.63 [0.29-0.97] | 0.74 [0.39-0.99] | 0.74 [0.47-0.99] | 0.77 [0.50-0.99] | 0.79 [0.48-0.99] |

| 3-Year AUC | 0.69 [0.40-0.97] | 0.80 [0.52-0.99] | 0.64 [0.37-0.92] | 0.74 [0.50-0.97] | 0.81 [0.58-0.99] | |

| 5-Year AUC | 0.65 [0.37-0.92] | 0.76 [0.50-0.99] | 0.74 [0.52-0.96] | 0.81 [0.64-0.98] | 0.86 [0.68-0.99] |

Data in brackets are 95% CIs.

AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; EORC, early-onset rectal cancer; pTNM, pathological TNM stage.

Kaplan–Meier curves showed that both the EORC-ClinRadiom and EORC-ClinPathRadiom models could discriminate between patients at high risk and low risk of recurrence (Figure 5D-I). The EORC-ClinPathRadiom model (Figure 5G-I) showed higher hazard ratios and more stable performance than the EORC-ClinRadiom model (Figure 5D-F) in the training set, internal test set, and external test set [HR in: the training set, 8.96 (95% CI 4.62-17.40), P < 0.001; internal test set, 6.81 (95% CI 1.99-23.34), P = 0.002; external test set, 7.46 (95% CI 1.42-39.06), P = 0.017].

At 1, 3, and 5 years after surgery, the calibration curve of the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model for predicting DFS could reflect the actual observed results very well (Supplementary Figure S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735). NRI and IDI also confirmed that the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model improved DFS prediction in EORC patients (Supplementary Table S4, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735). Decision curve analysis showed that the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model had an excellent overall net benefit, with advantages across the most reasonable threshold probability ranges (Supplementary Figure S5, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735).

Comparison of the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model with the pTNM staging

Our results showed that the C-index of the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model was significantly higher than that of the traditional pTNM model in the training set (0.82 versus 0.69, P < 0.001), internal test set (0.82 versus 0.63, P < 0.001), and external test set (0.81 versus 0.61, P < 0.001) (Table 3, Supplementary Table S3, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2024.103735). Furthermore, receiver operating characteristic curve analysis showed that the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model was superior to pTNM staging in predicting 1-, 3-, and 5-year DFS of EORC patients in the training set, and there was a significant difference in AUC values (1 year: 0.89 versus 0.78, P < 0.001; 3 years: 0.85 versus 0.73, P < 0.001; 5 years: 0.86 versus 0.73, P < 0.001) (Figure 5A-C). Subgroup analysis confirmed that the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model was effective in identifying high-risk patients in clinical stage 0/I [HR, 5.31 (95% CI 1.14-24.80), P = 0.017], clinical stage II [HR, 5.15 (95% CI 1.43-18.57), P = 0.005] and clinical stage III [HR, 7.68 (95% CI 2.97-19.89), P < 0.001] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Kaplan–Meier curves of DFS prediction by the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model for EORC patients in different pTNM subgroups.P value was calculated using a two-sided log-rank test. DFS, disease-free survival; EORC, early-onset rectal cancer; HR, hazard ratio; pTNM, pathological TNM stage.

Discussion

The morbidity and mortality of patients with EORC have increased significantly over the past 30 years.1,2 There is, however, still a lack of clear individualized treatment recommendations for patients with EORC. This study evaluated clinicopathological and MRI data from 1042 RC patients who underwent radical surgery at three medical institutions. The main findings are: (i) differences between EORC and LORC based on factors such as pretreatment CEA, tumor differentiation, neoadjuvant therapy, and adjuvant therapy; (ii) pretreatment positive CEA and positive lymph node status are risk factors for postoperative tumor recurrence in EORC patients; (iii) the new comprehensive model based on the clinicopathological variables and radiomics features of EORC, the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model, can effectively predict and stratify the recurrence risk of EORC and is superior to the traditional pTNM staging model.

It has been revealed that EORCs have different clinicopathological characteristics from those of LORCs.1,8,26 In this study, we also found that EORC patients had a higher proportion of undifferentiated and poorly differentiated tumors, and received more neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies, while there was no significant difference in DFS between EORC and LORC patients (64.85 versus 63.17, P = 0.298). Therefore, it is important to find appropriate methods to stratify the risk of poor prognosis in EORC patients and to screen out potentially high-risk patients in order to guide the selection of individualized treatment of EORC patients and to avoid overtreatment of low-risk patients.

TNM staging system has been widely adopted in clinical practice to guide therapeutic choices in patients with RC. The prognosis of RC patients with the same TNM staging, however, may differ significantly. In this study, the performance of the pTNM model for predicting DFS in EORC patients was not good enough, with a C-index of 69%, 63%, and 61% in the training set, external and internal test sets, respectively.

Serum CEA is a commonly used biomarker to detect RC, and persistently elevated CEA after treatment and re-elevated CEA after reduction are usually indicative of RC tumor survival or recurrence.27 The NCCN guideline also recommended serum CEA as a biomarker for monitoring RC tumor recurrence.12 Up to 49%-75% of RC patients show negative pretreatment CEA,28,29 however, and ∼58.7% remain negative even at the time of tumor recurrence.24 In this study, the proportion of patients with pretreatment positive CEA was significantly lower in EORC patients than in LORC patients (30.95% versus 39.33%, P < 0.05), and the proportion of patients with negative CEA reached 69.05% and 60.67% in EORC and LORC patients, respectively, so that relying on CEA level alone to predict a patient’s prognosis is bound to be inadequate. Our data suggest that pretreatment positive CEA and positive pN status are risk factors for tumor recurrence in EORC patients. On the basis of these two characteristics, our ClinPath model predicted DFS in EORC patients well with C-indexes of 0.71, 0.75, and 0.72 in the training, internal and external test sets, respectively, similar to the previous literature.30

It is well known that MRI is the preferred examination for patients with initial diagnosis of RC, and the signal of tumors on MR images may to some extent reflect the biological characteristics of tumors. Therefore, MRI-based radiomics and deep learning techniques have been increasingly used to predict the prognosis of tumor patients. To the best of our knowledge, however, no studies have been reported on the use of radiomics to predict tumor recurrence and risk stratification in EORC patients. In this study, our EORC-Radiom model showed a comparable predictive performance to the EORC-ClinPath model and stratified the risk of recurrence in patients with clinical stage 0/I and stage II/III EORC. To further improve the prediction performance, we constructed the EORC-ClinRadiom model by integrating clinical characteristics and radiomics features, which significantly outperformed the TNM, EORC-ClinPath, and EORC-Radiom models in predicting DFS and effectively stratified EORC patients in high and low risk of recurrence. This means that, independent of pathological findings, we can perform prognostic prediction and risk stratification of EORC patients preoperatively, which will be of great benefit for individualized treatment decisions. Finally, the EORC-ClinPathRadiom model was developed, which showed superior recurrence prediction ability and stratification effect compared with the pTNM staging system at 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years. This model overcomes the shortcomings of pTNM staging and is expected to provide more precise treatment and follow-up strategies for EORC patients.

The study has a number of limitations. First, it is a retrospective study with a relatively small sample size. Second, this study focused mainly on patients with rectal adenocarcinoma and did not analyze patients with pathological types of mucinous adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell carcinoma. Third, the use of different MRI scanners and parameter settings in the three centers may introduce some bias. Finally, this study only analyzed the T2WI and DWI sequence images of multimodal MRI and did not analyze the enhancement sequences, which requires future work.

Conclusion

The clinical and pathological characteristics of EORC are significantly different from those of LORC. The fusion model based on the unique clinicopathological characteristics and MRI radiomics features of EORC may help to predict and stratify the risk of postoperative recurrence in patients with EORC, thereby optimizing individualized treatment and follow-up decisions for EORC.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province [grant numbers 2021A1515011795, 2023A1515011292] and the program of Guangdong Provincial Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases [grant number 2020B1111170004].

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

S.-D. Xie, Email: xiesdong@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

X.-C. Meng, Email: mengxch3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Shen D., Wang P., Xie Y., et al. Clinical spectrum of rectal cancer identifies hallmarks of early-onset patients and next-generation treatment strategies. Cancer Med. 2023;12(3):3433–3441. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel S.G., Karlitz J.J., Yen T., Lieu C.H., Boland C.R. The rising tide of early-onset colorectal cancer: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, clinical features, biology, risk factors, prevention, and early detection. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(3):262–274. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00426-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinicrope F.A. Increasing incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(16):1547–1558. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2200869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaborowski A.M., Abdile A., Adamina M., et al. Characteristics of early-onset vs late-onset colorectal cancer: a review. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(9):865–874. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel R.L., Jemal A., Ward E.M. Increase in incidence of colorectal cancer among young men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1695–1698. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willauer A.N., Liu Y., Pereira A.A.L., et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(12):2002–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang J.T., Huang K.C., Cheng A.L., Jeng Y.M., Wu M.S., Wang S.M. Clinicopathological and molecular biological features of colorectal cancer in patients less than 40 years of age. Br J Surg. 2003;90(2):205–214. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang D.T., Pai R.K., Rybicki L.A., et al. Clinicopathologic and molecular features of sporadic early-onset colorectal adenocarcinoma: an adenocarcinoma with frequent signet ring cell differentiation, rectal and sigmoid involvement, and adverse morphologic features. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(8):1128–1139. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kneuertz P.J., Chang G.J., Hu C.Y., et al. Overtreatment of young adults with colon cancer: more intense treatments with unmatched survival gains. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(5):402–409. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.3572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saraste D., Jaras J., Martling A. Population-based analysis of outcomes with early-age colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2020;107(3):301–309. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaborowski A.M., Murphy B., Creavin B., et al. Clinicopathological features and oncological outcomes of patients with young-onset rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2020;107(5):606–612. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benson A.B., Venook A.P., Al-Hawary M.M., et al. Rectal Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(10):1139–1167. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glynne-Jones R., Wyrwicz L., Tiret E., et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl 4) doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bi W.L., Hosny A., Schabath M.B., et al. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(2):127–157. doi: 10.3322/caac.21552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillies R.J., Kinahan P.E., Hricak H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology. 2016;278(2):563–577. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng F., Ganeshan B., Kozarski R., Miles K.A., Goh V. Assessment of primary colorectal cancer heterogeneity by using whole-tumor texture analysis: contrast-enhanced CT texture as a biomarker of 5-year survival. Radiology. 2013;266(1):177–184. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng L., Liu Z., Li C., et al. Development and validation of a radiopathomics model to predict pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4(1):e8–e17. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Z., Meng X., Zhang H., et al. Predicting distant metastasis and chemotherapy benefit in locally advanced rectal cancer. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4308. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang Y., Wang H., Wu J., et al. Noninvasive imaging evaluation of tumor immune microenvironment to predict outcomes in gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(6):760–768. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao M., Feng L., Zhao K., et al. An MRI-based scoring system for pretreatment risk stratification in locally advanced rectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2023;129(7):1095–1104. doi: 10.1038/s41416-023-02384-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beets-Tan R.G., Beets G.L. MRI for assessing and predicting response to neoadjuvant treatment in rectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11(8):480–488. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng X., Xia W., Xie P., et al. Preoperative radiomic signature based on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for noninvasive evaluation of biological characteristics in rectal cancer. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(6):3200–3209. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5763-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins G.S., Reitsma J.B., Altman D.G., Moons K.G. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD Statement. Br J Surg. 2015;102(3):148–158. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen D., Wang X., Wang H., et al. Current surveillance after treatment is not sufficient for patients with rectal cancer with negative baseline CEA. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(6):653–662.e653. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.7101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Griethuysen J.J.M., Fedorov A., Parmar C., et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21):e104–e107. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spaander M.C.W., Zauber A.G., Syngal S., et al. Young-onset colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1):21. doi: 10.1038/s41572-023-00432-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang C., Zheng W., Lv Y., et al. Postoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels predict outcomes after resection of colorectal cancer in patients with normal preoperative CEA levels. Transl Cancer Res. 2020;9(1):111–118. doi: 10.21037/tcr.2019.11.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito G., Sadahiro S., Kamata H., et al. Monitoring of serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels after curative resection of colon cancer: cutoff values determined according to preoperative levels enhance the diagnostic accuracy for recurrence. Oncology. 2017;92(5):276–282. doi: 10.1159/000456075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramphal W., Boeding J.R.E., van Iwaarden M., et al. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen to predict recurrence in the follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2019;34(1):60–68. doi: 10.1177/1724600818820679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su Y., Yang D.S., Li Y.Q., Qin J., Liu L. Early-onset locally advanced rectal cancer characteristics, a practical nomogram and risk stratification system: a population-based study. Front Oncol. 2023;13 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1190327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.