Highlights

-

•

Concurrent endometrial and ovarian carcinomas can be challenging to diagnosis as synchronous primaries or metastatic disease.

-

•

Pathology alone is not always sufficient due to overlapping morphologic features and immunohistochemistry biomarkers among tumors.

-

•

Next generation sequencing may unequivocally determine clonality and properly separate metastatic from synchronous tumors.

Keywords: Synchronous tumors, Next generation sequencing, Immunohistochemistry, Genetic landscape, Clonality

Abstract

Background

Synchronous endometrial and ovarian carcinomas represent up to 10% of all endometrial and ovarian tumors. These are diagnostically challenging cases to determine if they represent dual primary tumors or related metastatic tumors.

Case

A 48-year-old was diagnosed with synchronous primary ovarian and endometrial malignancies on pathology based on traditional morphological parameters. However, following next generation sequencing (NGS) of tumors from both the uterus and ovary, the malignancies were unequivocally recognized as primary uterine tumor metastatic to the ovary using mismatch repair protein expression profile and tumor clonality.

Conclusion

NGS using FDA-approved commercially available platforms is becoming increasingly utilized to understand the genetic landscape of tumors and select the appropriate targeted therapies for improved outcomes. Simultaneous sequencing of synchronous endometrial and ovarian carcinomas may represent the new gold standard to unequivocally demonstrate tumor clonal relationships, properly classify disease as well as guide the most appropriate adjuvant treatment in these challenging cases.

1. Introduction

Endometrioid ovarian cancer commonly co-occurs with endometrioid endometrial cancer making the diagnosis of synchronous or metastatic cancer challenging (Cybulska et al., 2019). In fact, the relatively common co-occurrence of carcinomas in the endometrium and ovary, estimated between 3.1–10 %, led to the development of the Scully criteria in order to distinguish synchronous primary endometrial and ovarian cancers from metastatic disease (Alhilli et al., 2012, Scully et al., 1998). Scully criteria uses 8 components including histology, size, presence of precursor lesions, location, and invasion pattern to distinguish between synchronous and metastatic endometrioid tumors (Scully et al., 1998). However, increasing evidence has suggested that these criteria are not completely accurate, with an increasing proportion of cases initially considered to be dual primaries to be reclassified as metastatic disease when molecular analysis is carried out (Chao et al., 2016). While the prognosis for patients with stage I synchronous endometrioid endometrial and endometrioid ovarian cancers is generally good and similar to stage I endometrioid endometrial cancer, identifying/separating concurrent early stage cancers from metastatic disease is important for proper staging, the selection of the most appropriate adjuvant treatment and evaluation of patients’ eligibility for clinical trials (Reijnen et al., 2020). Accordingly, the recent approval by the FDA of multiple commercially available next generation sequencing (NGS) platforms to test tumor gene mutations (ie. tumor clonality) may represent a novel and effective approach in combination with traditional pathologic criteria to unequivocally establish the diagnosis of synchronous vs metastatic endometrial and ovarian cancers.

We present the case of a patient who was initially considered harboring synchronous endometrial and ovarian tumors before being subsequently diagnosed, unequivocally, with a uterine malignancy metastatic to the ovary by NGS (ie. Foundation Medicine). Simultaneous evaluation/sequencing of both synchronous uterine and ovarian tumors by commercially available genetic platforms may allow a more precise diagnosis and should be implemented to validate conventional pathology reports in these challenging patients.

2. Case

The patient is a 48-year-old premenopausal woman that underwent an extensive gastrointestinal work up beginning in August 2023 for abdominal discomfort, dyspareunia, pelvic bloating and pressure. While undergoing a colonoscopy in December of 2023, difficulty was encountered with colonic insufflation with subsequent pain and discomfort following the procedure, raising concern for a colonic perforation with the recommendation for immediate emergency room evaluation. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis performed revealed a 16.1 by 13.4-centimeter mass likely arising from the adnexa causing a mild hydronephrosis. There was also a small amount of ascites, nonspecific induration of the omentum, and several subcentimeter pelvic sidewall lesions.

Due to the concerning imaging findings, she was directed to a consultation with gynecologic oncology. In addition to her gastrointestinal symptoms, she was also reported to have experienced abnormal uterine bleeding in the prior months. Her physical exam was found to correlate with the imaging findings, with a large palpable mass occupying the posterior cul-de-sac, with limited mobility and of uncertain etiology. Lab work obtained at the time of presentation to gynecologic oncology was notable for a CA-125 of 5,240 U/mL and a CA 19–9 of 2,426 U/mL. The patient was recommended to undergo surgical management of this presumed complex adnexal mass with features concerning for a gynecologic malignant process. She subsequently underwent an exploratory laparotomy, total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, appendectomy, and optimal tumor cytoreduction in January 2024. The operative findings were significant for a 20 cm mass arising from the right fallopian tube and ovary with extensive retroperitoneal fibrosis and a thickened appendix, with no evidence of carcinomatosis in the upper abdomen. Her final pathology revealed a stage IIIB moderately differentiated ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma with ovarian surface and appendiceal involvement, and a synchronous stage IA FIGO Grade 2 endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma with superficial myometrial invasion and without lymphovascular invasion (Fig. 1). Using Scully’s pathologic criteria tumors were reported as most likely synchronous independent primaries. Due to loss of MSH-6 expression on immunohistochemistry concerning for Lynch syndrome she was referred to genetics. However, genetic testing revealed no germline mutations in any of the MMR genes. Accordingly, she was started on carboplatin and paclitaxel for her advanced stage (ie. stage IIIB). Foundation Medicine (FM) testing was initially requested on the ovarian specimen at time of discussion of the gynecologic oncology tumor board. Subsequently, after additional discussion of the case at the Precision Medicine clinical trial meeting, the uterine specimen was also sent to Foundation Medicine to analyze/compare tumor gene mutations and clonality in both samples and determine future eligibility for personalized targeted therapies and possible enrollment in clinical trials.

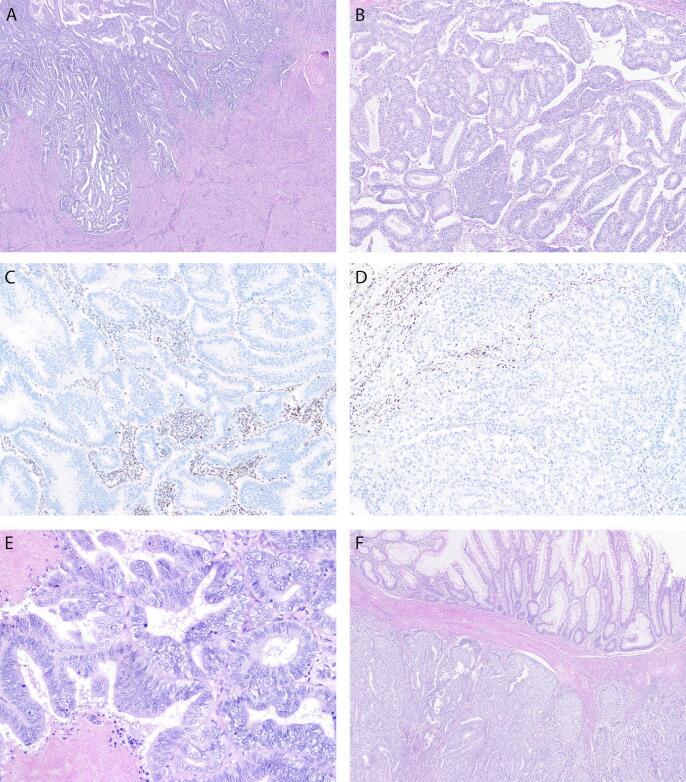

Fig. 1.

Pathologic features. The endometrial tumor (A) shows superficial myometrial invasion and shares morphologic similarities with the endometrioid adenocarcinoma in the ovary (B). Identical loss of nuclear MSH6 protein expression by immunohistochemistry is seen in both endometrial (C) and ovarian tumors (D). Admixed stromas cells and lymphocytes serve as internal positive control. Higher magnification image of the ovary (E) with pseudo-stratified columnar tumor cells exhibiting moderate nuclear atypia and focal necrosis. Sections from the appendix (F) demonstrate identical tumor morphology with serosal and muscularis propria invasion. Note the uninvolved appendiceal mucosa on the top portion of image.

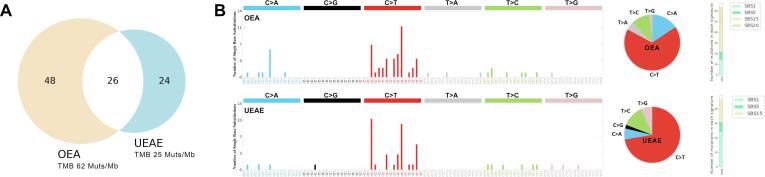

Importantly, the originally diagnosed synchronous primary tumor in the ovary was unequivocally appreciated by NGS to represent a metastasis of the endometrial primary. Testing on tumor from the ovary and uterus revealed a common deleterious hotspot mutation in MSH6 F1088fs*5 as well as multiple shared mutations including ERBB2, APC, ARID1A, ERBB3, FBXW7, NRAS, PTEN, DNMT3A, and FLT1 (Fig. 2). Consistent with the MSH6 F1088fs*5 findings, both tumor samples were reported as MSI-H (by NGS) and showed loss of MSH6 expression by immunohistochemistry. Mutational signatures were extracted using base substitutions and additionally included information on the sequence context of each mutation using SigProfilerMatrixGenerator reference signatures using SigProfilerAssignment (Bergstrom et al., 2019, Díaz-Gay et al., 2023). Obtained signature matrices were then fitted to COSMIC version 3.4 (Alexandrov et al., 2020). The metastatic ovarian tumor demonstrated a higher tumor mutation burden (TMB) of 65 Mut/Mb compared to the primary uterine tumor with 25 Mut/Mb while both tumors demonstrated typical genetic signatures consistent with MMRd tumors (Fig. 1) (Alexandrov et al., 2020). In light of the NGS data, the diagnosis was revised to a stage IVB MMRd endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma and the adjuvant treatment plan was expanded to include use of pembrolizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in accordance with NCCN guidelines for advanced stage endometrial cancer.

Fig. 2.

Repertoires of somatic mutations in the uterine (UEAE) vs the ovarian (OEA) endometrioid tumors. A) The Venn diagram represents the total number of somatic mutations (silent single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), nonsynonymous SNVs, and insertions/deletions) that are unique to the uterine and ovarian cancers and that are shared between them. B) Mutational signatures of all somatic SNVs in the uterine and ovarian cancer are displayed according to the 96 substitution classification defined by the substitution classes (C > A, C > G, C > T, T > A, T > C, and T > G bins) and the 5′ and 3′ sequence context, the overall distribution of substitutions, and their assignment to single base substitutions signatures according to COSMIC version 3.4. OEA: ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma; UEAE: uterine endometrial adenocarcinoma endometrioid; SBS: single base substitution signature; SBS1 & SBS5: related to aging; SBS15 & SBS20: related to MSI.

3. Discussion

Identification of the primary tumor origin in synchronous ovarian and uterine cancers is often a challenge in the daily practice of gynecologic oncology but is critical to provide appropriate treatment recommendations. Fundamental to diagnostic pathology is the use of H&E-stained tissue samples and immunohistochemistry (IHC), which may be adequate to establish the differential diagnosis. However significant morphologic/phenotypic overlap often exists among gynecologic primaries and between histologic subtypes requiring additional workup to definitively finalize the diagnosis of synchronous vs metastatic tumors (Buza and Hui, 2017).

Molecular characterization provides clinically relevant information beyond tumor grade and histology provided by pathology. Molecular profiling facilitates prognostication and tailored treatment decision making based on the identification of actionable genomic alterations. The Cancer Genome Atlas was pivotal in bringing molecular characterization of endometrial cancers into the spotlight. It exemplified that genomic based classifications of tumors can lead to improved management, while also emphasizing that molecular differences require individualized treatment paradigms (Getz et al., 2013). It led way for multiple organizations to promote molecular characterization, has influenced the design of clinical trials, and defined prognostic groups. As such, The FIGO Committee on Women’s Cancer updated endometrial cancer staging in 2023 to include histology and molecular findings to better reflect the underlying nature of endometrial carcinoma (Berek et al., 2023). Complete molecular classification including POLEmut, MMRd, NSMP, and p53abn is utilized to stratify patients into stages that both reflect prognosis and guide treatment decisions (Berek et al., 2023).

Recently, several commercially available NGS platforms have been approved by the FDA and accordingly, have become popular options to analyze multigene panels in endometrial cancer patients. Targeted or whole exome genome sequencing results provide an understanding of the molecular classifications outlined by the Cancer Genome Atlas including information on somatic and germline mutations, substitution, deletions, insertions, chromosomal rearrangements and genetic signatures. Importantly, tumor mutation burden (TMB), an information commonly reported in NGS reports, can aid in predicting response to immunotherapy, with a higher TMB generating more neoantigens that can provoke a more effective T-cell response (Sha et al., 2020). Importantly, when determining if endometrial and ovarian endometrioid carcinomas are synchronous independent primaries or represent metastatic tumors, mutational analysis can consistently reveal shared somatic mutations to determine clonality (Chao et al., 2016). During the process of carcinogenesis, subclones have the same inherited genetics, therefore the patterns of somatic mutations and epigenetic alterations can be used to identify clonality. However, tumors that originate from the same progenitor cells will continue to dedifferentiate through clonal evolution and transform leading to the subsequent subpopulations with additional genetic alterations (Cheng et al., 2013). Accordingly, this is commonly reflected in a higher TMB in metastatic disease sites when compared to primary tumors as we demonstrated in the genetic analysis of the uterine and ovarian tumors of this patient as well as previously using WES in multiple matched primary vs metastatic ovarian cancers (Li et al., 2019). Clonality can be established by similar patterns of loss of heterozygosity, identical genomic mutations, or chromosomal alterations (Cheng et al., 2013). Of interest, in endometrial cancer, MSI has been shown to reliably confirm clonality (Kaneki et al., 2004). In this patient, similar features on histology prompted sequencing of both the ovarian and endometrial tumor to determine the existence of clonality and was successfully covered by insurance.

As we strive to provide enhanced care to our patients and novel treatments to improve outcomes, molecular profiling of tumors plays a paramount role. Its use is not only imperative for ascertaining a correct diagnosis in certain situations, but also facilitates directed treatment at targetable mutations. This case demonstrates how the use of NGS (ie Foundation Medicine testing) both clarified the patient’s diagnosis and subsequently led to a change in adjuvant treatment. Although the use of established histological parameters may be adequate in many cases, in situations where it is difficult to distinguish the relationship of tumors, genomic analysis remains paramount to establishing clonality and lead to a precise diagnosis. In this case presented, the clonal relationship and MSI-H characteristics proved the connection between the primary and metastatic tumor endometrioid tumor. The increasingly important role of molecular classification, reflected in the updated endometrial cancer FIGO staging, is pivotal for understanding of prognosis and guidance of treatment, and as such requires providers to advocate for the financial authorization of molecular testing of both tumor sites. In conclusion, we demonstrate the importance of profiling synchronous uterine and ovarian tumors using FDA approved NGS platforms to unequivocally determine the primary site of disease and establish the most appropriate plan for subsequent management of these challenging cases/patients.

4. Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Michelle Greenman: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization. Stefania Bellone: Writing – review & editing. Tobias Hartwitch: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal analysis. Natalia Buza: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Formal analysis, Data curation. Alessandro D. Santin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: [A.D.S. reports grants from GILEAD, grants and personal fees from MERCK, grants from BOEHINGER-INGELHEIM, grants and personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo and grants and personal fees from EISAI and R-Pharm USA. The other authors declare no conflict of interest].

Acknowledgement

We thank the patient for allowing us to publish this case report. This work was supported in part by grants from NIH U01 CA 176067-01A1, the Deborah Bunn Alley Foundation, the Domenic Cicchetti Foundation, and Discovery to Cure Foundation, and the Guido Berlucchi Foundation to AS. This investigation was also supported by NIH Research Grant CA-16359 from NCI and Standup-to-cancer (SU2C) convergence grant 2.0 to AS.

References

- Alexandrov L.B., Kim J., Haradhvala N.J., Huang M.N., Tian Ng A.W., Wu Y., Boot A., Covington K.R., Gordenin D.A., Bergstrom E.N., Islam S.M.A., Lopez-Bigas N., Klimczak L.J., McPherson J.R., Morganella S., Sabarinathan R., Wheeler D.A., Mustonen V., Boutros P., Chan K., Fujimoto A., Getz G., Huang M.N., Kazanov M., Lawrence M., Martincorena I., Morganella S., Nakagawa H., Polak P., Prokopec S., Roberts S.A., Rozen S.G., Saini N., Shibata T., Shiraishi Y., Stratton M.R., Teh B.T., Vázquez-García I., Yousif F., Yu W. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature. 2020;578 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1943-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhilli M.M., Dowdy S.C., Weaver A.L., St. Sauver J.L., Keeney G.L., Mariani A., Podratz K.C., Gamez J.N.B. Incidence and factors associated with synchronous ovarian and endometrial cancer: a population-based case-control study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012;125 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berek J.S., Matias-Guiu X., Creutzberg C., Fotopoulou C., Gaffney D., Kehoe S., Lindemann K., Mutch D., Concin N., Berek J.S., Wilailak S., Kehoe S., Anorlu R., Cain J., Creutzberg C., Fotopoulou C., Lindeque G., Matias-Guiu X., McNally O., Okamoto A., Pareja R., Pomerantz T., Scambia G., Schmalfeld B., Tahlak M.A., Berek J., Concin N., Creutzberg C., Fotopoulou C., Gaffney D., Kehoe S., Lindemann K., Matias-Guiu X. FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023;162 doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom E.N., Huang M.N., Mahto U., Barnes M., Stratton M.R., Rozen S.G., Alexandrov L.B. SigProfilerMatrixGenerator: A tool for visualizing and exploring patterns of small mutational events. BMC Genomics. 2019;20 doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6041-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buza N., Hui P. Immunohistochemistry in gynecologic pathology an example-based practical update. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2017;141 doi: 10.5858/arpa.2016-0541-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao A., Wu R.C., Jung S.M., Lee Y.S., Chen S.J., Lu Y.L., Tsai C.L., Lin C.Y., Tang Y.H., Chen M.Y., Huang H.J., Chou H.H., Huang K.G., Chang T.C., Wang T.H., Lai C.H. Implication of genomic characterization in synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancers of endometrioid histology. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016;143 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.07.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L., Zhang, S., Monzon, F.A., Jones, T.D., Eble, J.N., 2013. Clonality analysis and tumor of unknown primary: Applications in modern oncology and surgical pathology, in: Molecular Genetic Pathology: Second Edition. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4800-6_6.

- Cybulska P., Paula A.D.C., Tseng J., Leitao M.M., Bashashati A., Huntsman D.G., Nazeran T.M., Aghajanian C., Abu-Rustum N.R., DeLair D.F., Shah S.P., Weigelt B. Molecular profiling and molecular classification of endometrioid ovarian carcinomas. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019;154 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Gay M., Vangara R., Barnes M., Wang X., Islam S.M.A., Vermes I., Duke S., Narasimman N.B., Yang T., Jiang Z., Moody S., Senkin S., Brennan P., Stratton M.R., Alexandrov L.B. Assigning mutational signatures to individual samples and individual somatic mutations with SigProfilerAssignment. Bioinformatics. 2023;39 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btad756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz G., Gabriel S.B., Cibulskis K., Lander E., Sivachenko A., Sougnez C., Lawrence M., Kandoth C., Dooling D., Fulton R., Fulton L., Kalicki-Veizer J., McLellan M.D., O’Laughlin M., Schmidt H., Wilson R.K., Ye K., Li D., Ally A., Balasundaram M., Birol I., Butterfield Y.S.N., Carlsen R., Carter C., Chu A., Chuah E., Chun H.J.E., Dhalla N., Guin R., Hirst C., Holt R.A., Jones S.J.M., Lee D., Li H.I., Marra M.A., Mayo M., Moore R.A., Mungall A.J., Plettner P., Schein J.E., Sipahimalani P., Tam A., Varhol R.J., Gordon Robertson A., Cherniack A.D., Pashtan I., Saksena G., Onofrio R.C., Schumacher S.E., Tabak B., Carter S.L., Hernandez B., Gentry J., Salvesen H.B., Ardlie K., Winckler W., Beroukhim R., Meyerson M., Hadjipanayis A., Lee S., Mahadeshwar H.S., Park P., Protopopov A., Ren X., Seth S., Song X., Tang J., Xi R., Yang L., Dong Z., Kucherlapati R., Chin L., Zhang J., Todd Auman J., Balu S., Bodenheimer T., Buda E., Neil Hayes D., Hoyle A.P., Jefferys S.R., Jones C.D., Meng S., Mieczkowski P.A., Mose L.E., Parker J.S., Perou C.M., Roach J., Yan S., Simons J.V., Soloway M.G., Tan D., Topal M.D., Waring S., Wu J., Hoadley K.A., Baylin S.B., Bootwalla M.S., Lai P.H., Triche T.J., Van Den Berg D.J., Weisenberger D.J., Laird P.W., Shen H., Cho J., Dicara D., Frazer S., Heiman D., Jing R., Lin P., Mallard W., Stojanov P., Voet D., Zhang H., Zou L., Noble M., Reynolds S.M., Shmulevich I., Arman Aksoy B., Antipin Y., Ciriello G., Dresdner G., Gao J., Gross B., Jacobsen A., Ladanyi M., Reva B., Sander C., Sinha R., Onur Sumer S., Taylor B.S., Cerami E., Weinhold N., Schultz N., Shen R., Benz S., Goldstein T., Haussler D., Ng S., Szeto C., Stuart J., Benz C.C., Yau C., Zhang W., Annala M., Broom B.M., Casasent T.D., Ju Z., Liang H., Liu G., Lu Y., Unruh A.K., Wakefield C., Weinstein J.N., Zhang N., Liu Y., Broaddus R., Akbani R., Mills G.B., Adams C., Barr T., Black A.D., Bowen J., Deardurff J., Frick J., Gastier-Foster J.M., Grossman T., Harper H.A., Hart-Kothari M., Helsel C., Hobensack A., Kuck H., Kneile K., Leraas K.M., Lichtenberg T.M., McAllister C., Pyatt R.E., Ramirez N.C., Tabler T.R., Vanhoose N., White P., Wise L., Zmuda E., Barnabas N., Berry-Green C., Blanc V., Boice L., Button M., Farkas A., Green A., MacKenzie J., Nicholson D., Kalloger S.E., Blake Gilks C., Karlan B.Y., Lester J., Orsulic S., Borowsky M., Cadungog M., Czerwinski C., Huelsenbeck-Dill L., Iacocca M., Petrelli N., Rabeno B., Witkin G., Nemirovich-Danchenko E., Potapova O., Rotin D., Berchuck A., Birrer M., Disaia P., Monovich L., Curley E., Gardner J., Mallery D., Penny R., Dowdy S.C., Winterhoff B., Dao L., Gostout B., Meuter A., Teoman A., Dao F., Olvera N., Bogomolniy F., Garg K., Soslow R.A., Abramov M., Bartlett J.M.S., Kodeeswaran S., Parfitt J., Moiseenko F., Clarke B.A., Goodman M.T., Carney M.E., Matsuno R.K., Fisher J., Huang M., Kimryn Rathmell W., Thorne L., Van Le L., Dhir R., Edwards R., Elishaev E., Zorn K., Goodfellow P.J., Mutch D., Kahn A.B., Bell D.W., Pollock P.M., Wang C., Wheeler D., Shinbrot E., Gordon Robertson A., Ding L., Blake Gilks C., Mardis E.R., Ayala B., Chu A.L., Jensen M.A., Kothiyal P., Pihl T.D., Pontius J., Pot D.A., Snyder E.E., Srinivasan D., Mills Shaw K.R., Sheth M., Davidsen T., Eley G., Ferguson M.L., Yang L., Guyer M.S., Ozenberger B.A., Sofia H.J., Gordon Robertson A., Levine D.A. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497 doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneki E., Oda Y., Ohishi Y., Tamiya S., Oda S., Hirakawa T., Nakano H., Tsuneyoshi M. Frequent microsatellite instability in synchronous ovarian and endometrial adenocarcinoma and its usefulness for differential diagnosis. Hum. Pathol. 2004;35 doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., Bonazzoli, E., Bellone, S., Choi, J., Dong, W., Menderes, G., Altwerger, G., Han, C., Manzano, A., Bianchi, A., Pettinella, F., Manara, P., Lopez, S., Yadav, G., Riccio, F., Zammataro, L., Zeybek, B., Yang-Hartwich, Y., Buza, N., Hui, P., Wong, S., Ravaggi, A., Bignotti, E., Romani, C., Todeschini, P., Zanotti, L., Zizioli, V., Odicino, F., Pecorelli, S., Ardighieri, L., Silasi, D.A., Litkouhi, B., Ratner, E., Azodi, M., Huang, G.S., Schwartz, P.E., Lifton, R.P., Schlessinger, J., Santin, A.D., 2019. Mutational landscape of primary, metastatic, and recurrent ovarian cancer reveals c-MYC gains as potential target for BET inhibitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1814027116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reijnen C., Küsters-Vandevelde H.V.N., Ligtenberg M.J.L., Bulten J., Oosterwegel M., Snijders M.P.L.M., Sweegers S., de Hullu J.A., Vos M.C., van der Wurff A.A.M., van Altena A.M., Eijkelenboom A., Pijnenborg J.M.A. Molecular profiling identifies synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancers as metastatic endometrial cancer with favorable clinical outcome. Int. J. Cancer. 2020;147 doi: 10.1002/ijc.32907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully R.E., Young R.H., Clement P.B. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; Washington, DC: 1998. Atlas of tumor pathology. [Google Scholar]

- Sha D., Jin Z., Budczies J., Kluck K., Stenzinger A., Sinicrope F.A. Tumor mutational burden as a predictive biomarker in solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 2020;10 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]