Highlights

-

•

HCMV poses significant risks to newborns and immunocompromised individuals.

-

•

Verteporfin is an FDA-approved medication used in photodynamic therapy.

-

•

Verteporfin inhibits HCMV progeny virus production.

-

•

Verteporfin suppresses HCMV gene expression from the immediate-early stages.

-

•

Verteporfin has the potential to be repurposed as a drug against HCMV infection.

Keywords: Human cytomegalovirus, Verteporfin, Drug repositioning, Antiviral activity

Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a double-stranded DNA virus from the Betaherpesvirinae subfamily, constitutes significant risks to newborns and immunocompromised individuals, potentially leading to severe neurodevelopmental disorders. The purpose of this study was to identify FDA-approved drugs that can inhibit HCMV replication through a drug repositioning approach. Using an HCMV progeny assay, verteporfin, a medication used as a photosensitizer in photodynamic therapy, was found to inhibit HCMV production in a dose-dependent manner, significantly reducing replication at concentrations as low as 0.5 µM, approximately 1/20th of the concentration used in anti-cancer research. Further analysis revealed that verteporfin did not interfere with HCMV host cell entry or nuclear transport but reduced viral mRNA and protein levels throughout the HCMV life cycle from the immediate-early stages. These results suggest that verteporfin has the potential to be rapidly and safely developed as a repurposed drug to inhibit HCMV infection.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the Betaherpesvirinae subfamily within the Herpesviridae, is widespread, with a seroprevalence rate of up to 90 % among adults in the United States (Staras et al., 2006). While often asymptomatic in healthy individuals, HCMV causes significant risks, particularly to newborns and those with compromised immune systems, manifesting in various diseases. Fetal HCMV infection, for instance, can lead to severe neurodevelopmental disorders such as hearing loss, cerebral palsy, mental retardation, and microcephaly (Cheeran et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011; Teissier et al., 2014). Despite its clinical importance, there is still no safe and effective treatment strategy for HCMV infection.

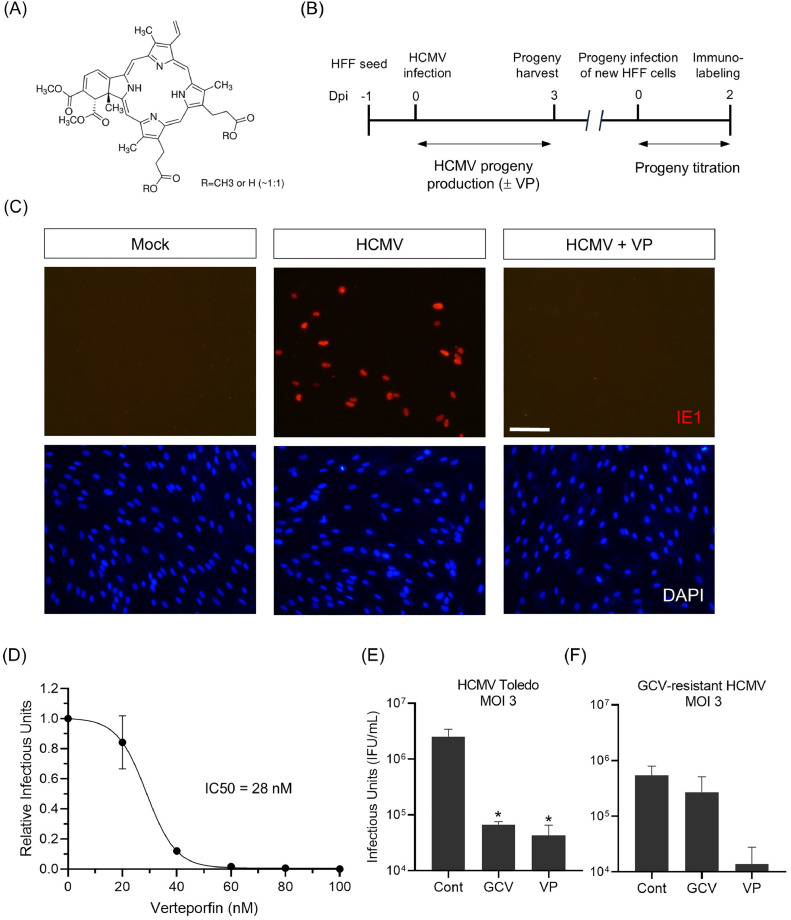

Verteporfin (Fig. 1A), a derivative of benzoporphyrin, is a medication utilized as a photosensitizer in photodynamic therapy (Stapleton, 2009). Upon intravenous injection and subsequent activation by laser light, verteporfin generates reactive oxygen radicals, leading to localized damage to the vascular endothelium and resulting in vessel occlusion. In 2000, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved verteporfin for the treatment of choroidal neovascularization associated with age-related macular degeneration, ocular histoplasmosis, and pathologic myopia (Kaiser, 2007). Shortly thereafter, verteporfin was identified as an inhibitor of the TEAD-YAP complex (Liu-Chittenden et al., 2012), which induces cell proliferation in response to cell density (Lee et al., 2022). Since its identification as a YAP/TEAD inhibitor, verteporfin has been actively studied in oncologic research as an anticancer agent, aiming to suppress the proliferation of various cancer cells, including those of colon, ovarian and breast cancers (Zhang et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2016; Wei and Li, 2020). Beyond its YAP inhibitory function, verteporfin is also being tested for its autophagy inhibitory and proteotoxic effects as an anticancer drug against osteosarcoma cells (Saini et al., 2021). Additionally, recent studies have shown that verteporfin functions as a γ-secretase inhibitor and it is thus being investigated as a potential treatment for Alzheimer's disease (Castro et al., 2022). Collectively, verteporfin is being explored as a therapeutic agent across various fields of drug discovery.

Fig. 1.

Verteporfin reduces HCMV progeny production.

(A) Chemical structure of verteporfin. (B) Schematic diagram of HCMV progeny virus titration assay used in this study. Progeny viruses were harvested at 3 dpi and titrated by infecting new HFF cells, followed by IE1 immunolabeling at 2 dpi. All infections were performed with the HCMV Towne strain at an MOI of 0.2, unless noted otherwise. (C) Titration of progeny viruses harvested from verteporfin-treated HFF cells infected with HCMV by anti-IE1 immunostaining (red). (D) Calculation of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of verteporfin on HCMV replication. (E-F) Effects of verteporfin on replication of the HCMV Toledo strain (E) and a ganciclovir-resistant strain (F). Dpi, days postinfection; GCV, ganciclovir (Sigma-Aldrich, G2536); VP, verteporfin (Sigmal-Aldrich, SML0534). Scale bar, 200 μm. Error bars represent SEM. Student's t-test was used to determine statistical significance. *P < 0.05.

This study focused on screening existing FDA-approved drugs for their ability to inhibit HCMV replication, with verteporfin being identified through an HCMV progeny assay (Fig. 1B). All infections were performed using the HCMV Towne strain at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.2, except where noted. In oncological research, verteporfin is typically used at concentrations of about 4 to 10 µM to inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells (Wang et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2023). Notably, verteporfin significantly inhibited HCMV progeny production at 0.5 µM, a concentration approximately 1/20th of that used in anti-cancer experiments (Fig. 1C). Indeed, a cell viability assay using XTT dye showed that verteporfin was not toxic to host cells up to a concentration of 0.5 µM, even after 5 days of treatment (Supplementary Fig. 1). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of verteporfin was calculated to be 28 nM (Fig. 1D).

Since ganciclovir is one of the most well-known anti-HCMV drugs, we conducted an experiment to compare verteporfin and ganciclovir. As shown in Fig. 1E, verteporfin inhibited progeny virus production at a level comparable to ganciclovir. In this experiment, we used the HCMV Toledo strain at an MOI of 3, and showed that verteporfin effectively inhibits viral replication in different HCMV strains at higher MOIs. Furthermore, verteporfin effectively suppressed the replication of a ganciclovir-resistant HCMV strain (H600L, a kind gift from Dr. Jin-Hyun Ahn, Sungkyunkwan University; Park et al., 2022) (Fig. 1F).

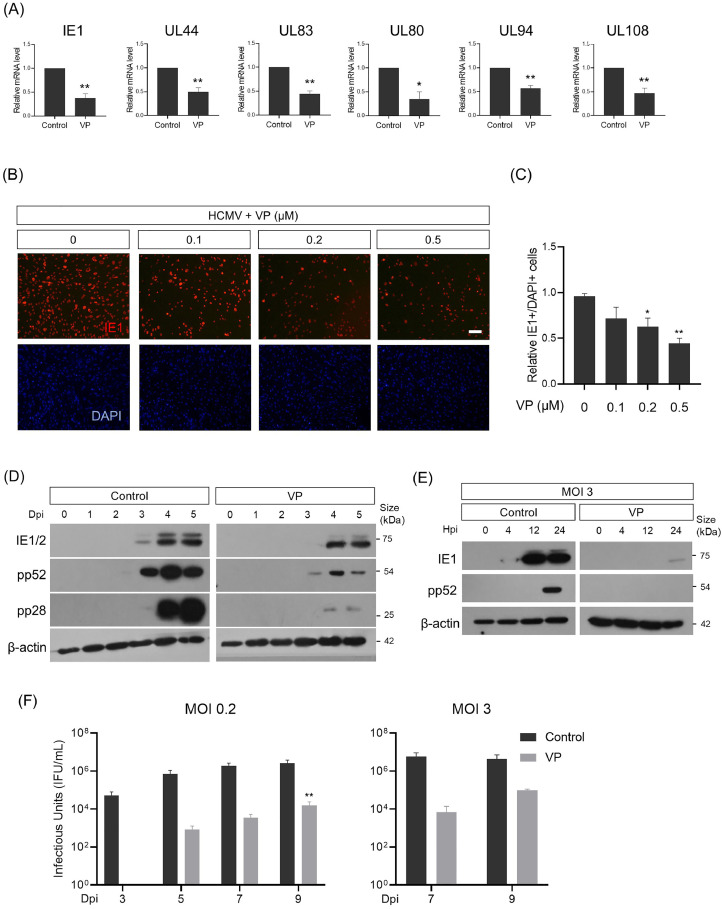

To determine which steps of HCMV replication were affected by verteporfin, we performed quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis to measure the mRNA levels of HCMV viral genes. The HCMV replication cycle lasts approximately 4 days in fibroblast cultures, resulting in the production of infectious virions and the eventual destruction of the host cell (Monti et al., 2022). Based on this information, we initially harvested HCMV-infected cells at 5 days postinfection (dpi), well after one complete infection cycle, and conducted mRNA analysis. As shown in Fig. 2A, mRNA levels of representative immediate-early (IE1), early (UL44 and UL83), and late (UL80, UL94 and UL108) stage-specific HCMV genes were reduced in verteporfin-treated host cells. We also observed that the number of IE1-expressing cells remained low in a verteporfin concentration-dependent manner, even at 5 dpi (Fig. 2B and C).

Fig. 2.

Verteporfin reduces HCMV gene expression from the immediate-early stages.

(A) qPCR analysis for representative immediate-early (IE1), early (UL44 and UL83) and late (UL80, UL94 and UL108) HCMV viral gene expression in verteporfin-treated HFF cells infected with HCMV at an MOI of 0.2 and harvested at 5 dpi. The mRNA level of each gene was normalized to β-actin mRNA. (B) Anti-IE1 immunostaining of HFF cells infected with HCMV at an MOI of 0.2 at 5 dpi, either in the presence or absence of verteporfin. Cells were counterstained with DAPI to visualize nuclei (blue). (C) Quantification of (B). (D) Western blot analyses of HCMV IE1, pp52, and pp28 proteins in verteporfin-treated HFF cells infected with HCMV at an MOI of 0.2 and harvested at the indicated dpi. (E) Detection of IE1 and pp52 proteins in HFF cells infected with HCMV at an MOI of 3 and harvested at the indicated hpi. (F) Titration of HCMV progeny virus harvested at the indicated time points over a 9-day long-term infection period. Dpi, days postinfection; Hpi, hours postinfection; VP, verteporfin. Scale bar, 50 μm. Error bars represent SEM. Student's t-test (for A, C), one-way ANOVA with Turkey's multiple comparison test (for F) was used to determine statistical significance. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

To characterize the changes in HCMV gene expression kinetics induced by verteporfin, HFF cells infected with HCMV were harvested for viral protein analysis over a time course of 5 dpi. Western blot analysis confirmed impaired HCMV gene expression at the protein level (Fig. 2D). For instance, treatment with verteporfin delayed initial detection and reduced the expression levels of IE1, pp52, and pp28 proteins. When infected at an MOI of 3, verteporfin treatment showed a marked difference in IE1 expression within a 24 h postinfection (hpi) period (Fig. 2E). Given that HCMV immediate-early genes are essential for the transcription of early and late-stage genes, facilitating progression into the later phases of the infectious cycle (Nevels et al., 2004), these data suggest that verteporfin interferes with HCMV replication at the immediate-early stages of the viral life cycle.

Reduced levels of IE1 mRNA and protein suggest that verteporfin impacts the early stages of the HCMV replication cycle, possibly even acting before the initiation of viral gene expression. Thus, we examined the initial phase of viral infection: the entry process. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2A, the relative quantities of viral DNA entering the cells examined at 1 hpi remained unaltered by verteporfin treatment. We then tested the next stage of viral infection by harvesting HCMV-infected cells at 4 hpi for nuclear fractionation. qPCR analysis showed that viral genome levels in the nucleus were not significantly different between the verteporfin-untreated and -treated samples (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Immunostaining of pp65, a tegument protein that translocates to the nucleus early in infection, using samples collected 4 hpi, also revealed that nuclear translocation of HCMV was not affected by verteporfin (Supplementary Fig. 2C). These data suggest that the reduction in HCMV gene expression by verteporfin from the immediate-early stages is not due to inhibition of viral entry into host cells or inhibition of the nuclear translocation of viral components.

Finally, we tested whether verteporfin reduces peak replication or delays viral replication. We harvested progeny virus at 2-day intervals until 9 dpi. Fig. 2F shows that the inhibitory effect of verteporfin persisted for up to 9 days, during which the viral progeny from verteporfin-treated samples remained strikingly lower than untreated controls; even at its highest, progeny virus production of the verteporfin-treated group was only 1/350 of that of the untreated group. Similarly, in experiments with an MOI of 3, even the highest number of HCMV viral progeny produced in verteporfin-treated samples was as low as 1/150 of the control. These data suggest that verteporfin suppresses peak HCMV replication.

Beyond its initial use in treating ophthalmic diseases, verteporfin is now being investigated as a therapeutic agent for various conditions, including cancer and Alzheimer's disease. In this paper, we demonstrated that verteporfin effectively inhibits HCMV progeny virus production, providing evidence that this is due to a reduction in the production of HCMV viral gene products within host cells. Furthermore, we showed that the decrease in HCMV viral gene product by verteporfin was not due to inhibition of HCMV entry into the host cell.

We emphasize that the use of verteporfin as a drug to suppress HCMV infection has two major benefits. Verteporfin, in our study, showed anti-HCMV activity at concentrations (Fig. 1D) much lower than those used in anticancer research (4 to 10 µM) (Wang et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2023). This means that it can be used clinically with minimal systemic toxicity. Another is that verteporfin itself inhibits HCMV infection without the need for additional steps such as light activation, which is required in photodynamic therapy treatment for choroidal neovascularization.

Given the well-known inhibitory effect of verteporfin on YAP-dependent transcription, it is reasonable to question whether the verteporfin-repressed HCMV replication observed in this study results from impaired YAP function. We have clear evidence to address this question; we have observed that YAP activation, similar to verteporfin treatment, inhibits HCMV replication (Lee et al., 2022). This strongly suggests that verteporfin inhibition of HCMV replication occurs through a YAP-independent mechanism.

While screening various FDA-approved drugs for their potential anti-HCMV activity, the Eichler group suggested that verteporfin might negatively regulate HCMV replication by inhibiting the HCMV core nuclear egress complex, specifically by disrupting the interaction between the HCMV pUL50 and pUL53 proteins (Alkhashrom et al., 2021). Nuclear egress is a crucial process that enables the migration of newly formed viral capsids from the nucleus to the cytoplasm during the late stages of virus replication (Marschall et al., 2017). However, they were unable to provide experimental evidence. Additionally, their proposed mechanism of HCMV inhibition by verteporfin (inhibition of viral protein interactions at late stages) differs significantly from the mechanism we demonstrated experimentally in this study (inhibition of viral gene expression from the immediate early stages). However, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that, in addition to the inhibition of viral gene expression, inefficient nuclear egress may have also contributed to the decrease in HCMV progeny production caused by verteporfin.

Viruses within the same family frequently exhibit similar drug responses. Specifically, viruses in the Herpesviridae family often respond similarly to antiviral treatments. For instance, ganciclovir, initially developed as an inhibitor of HCMV, also shows antiviral activity against HSV types 1 and 2, Epstein-Barr virus, varicella-zoster virus, and human herpesvirus 6 (Crumpacker, 1996). Therefore, future studies should investigate the effectiveness of verteporfin against these various herpes viruses. Additionally, efforts should be made to develop more potent antiviral analogs or derivatives of verteporfin.

Author statement

We certify that all authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and contributed significantly to the work. The manuscript has not been published previously and is not being considered for publication elsewhere.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Woo Young Lim: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology. Ju Hyun Lee: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Youngju Choi: Formal analysis, Investigation. Keejung Yoon: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Republic of Korea (2021R1A2C1009018 to K.Y.).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2024.199475.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Alkhashrom S., Kicuntod J., Häge S., Schweininger J., Muller Y.A., Lischka P., Marschall M., Eichler J. Exploring the human cytomegalovirus core nuclear egress complex as a novel antiviral target: a new type of small molecule inhibitors. Viruses. 2021;13(3) doi: 10.3390/v13030471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro M.A., Parson K.F., Beg I., Wilkinson M.C., Nurmakova K., Levesque I., Voehler M.W., Wolfe M.S., Ruotolo B.T., Sanders C.R. Verteporfin is a substrate-selective γ-secretase inhibitor that binds the amyloid precursor protein transmembrane domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2022;298(4) doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeran M.C.J., Lokensgard J.R., Schleiss M.R. Neuropathogenesis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: disease mechanisms and prospects for intervention. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009;22(1):99–126. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00023-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhang L.F., Miao Y., Xi Y., Li X., Liu M.F., Zhang M., Li B. Verteporfin Suppresses YAP-Induced Glycolysis in Breast Cancer Cells. J. Invest. Surg. 2023;36(1) doi: 10.1080/08941939.2023.2266732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumpacker C.S. Ganciclovir. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996;335(10):721–729. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609053351007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J., Gou J., Jia J., Yi T., Cui T., Li Z. Verteporfin, a suppressor of YAP-TEAD complex, presents promising antitumor properties on ovarian cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:5371–5381. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S109979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser P.K. Verteporfin photodynamic therapy and anti-angiogenic drugs: potential for combination therapy in exudative age-related macular degeneration. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2007;23(3):477–487. doi: 10.1185/030079907X167624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.H., Kwon M., Lim W.Y., Yoo C.R., Yoon Y., Han D., Ahn J.H., Yoon K. YAP inhibits HCMV replication by impairing STING-mediated nuclear transport of the viral genome. PLoS Pathog. 2022;18(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu-Chittenden Y., Huang B., Shim J.S., Chen Q., Lee S.J., Anders R.A., Liu J.O., Pan D. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes Dev. 2012;26(12):1300–1305. doi: 10.1101/gad.192856.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschall M., Muller Y.A., Diewald B., Sticht H., Milbradt J. The human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress complex unites multiple functions: recruitment of effectors, nuclear envelope rearrangement, and docking to nuclear capsids. Rev. Med. Virol. 2017;27(4) doi: 10.1002/rmv.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti C.E., Mokry R.L., Schumacher M.L., Dash R.K., Terhune S.S. Computational modeling of protracted HCMV replication using genome substrates and protein temporal profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2022;119(35) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2201787119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevels M., Paulus C., Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 1 protein facilitates viral replication by antagonizing histone deacetylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101(49):17234–17239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407933101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K.R., Kim Y.E., Shamim A., Gong S., Choi S.H., Kim K.K., Kim Y.J., Ahn J.H. Analysis of novel drug-resistant human cytomegalovirus DNA polymerase mutations reveals the role of a DNA binding loop in phosphonoformic acid resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.771978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini H., Sharma H., Mukherjee S., Chowdhury S., Chowdhury R. Verteporfin disrupts multiple steps of autophagy and regulates p53 to sensitize osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1) doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton M. In: xPharm: The Comprehensive Pharmacology Reference. Enna S.J., Bylund D.B., editors. Elsevier; New York: 2009. Verteporfin; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Staras S.A.S., Dollard S.C., Radford K.W., Flanders W.D., Pass R.F., Cannon M.J. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988–1994. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;43(9):1143–1151. doi: 10.1086/508173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teissier N., Fallet-Bianco C., Delezoide A.-L., Laquerrière A., Marcorelles P., Khung-Savatovsky S., Nardelli J., Cipriani S., Csaba Z., Picone O., Golden J.A., Abbeele T.V.D., Gressens P., Adle-Biassette H. Cytomegalovirus-induced brain malformations in fetuses. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014;73(2):143–158. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Shao W., Shi Y., Liao J., Chen X., Wang C. Verteporfin induced SUMOylation of YAP1 in endometrial cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020;10(4):1207–1217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Zhang X., Bialek S., Cannon M.J. Attribution of congenital cytomegalovirus infection to primary versus non-primary maternal infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52(2):e11–e13. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C., Li X. Verteporfin inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in different subtypes of breast cancer cell lines without light activation. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07555-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Ramakrishnan S.K., Triner D., Centofanti B., Maitra D., Győrffy B., Sebolt-Leopold J.S., Dame M.K., Varani J., Brenner D.E., Fearon E.R., Omary M.B., Shah Y.M. Tumor-selective proteotoxicity of verteporfin inhibits colon cancer progression independently of YAP1. Sci. Signal. 2015;8(397) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aac5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.