Abstract

Objective:

To describe the landscape of needs for housing assistance among people with HIV (PWH) and availability of Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS (HOPWA) funding with respect to housing service needs, nationally and for 17 US jurisdictions.

Design:

The CDC Medical Monitoring Project (MMP) is an annual, cross-sectional survey designed to report nationally and locally representative estimates of characteristics and outcomes among adults with diagnosed HIV in the United States.

Methods:

We analyzed 2015–2020 data from MMP and 2019 funding data from HOPWA. Weighted percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for national and jurisdiction-level estimates were reported.

Results:

Nationally, 1 in 4 (27.7%) PWH had shelter or housing service needs. Among those who needed housing services, 2 in 5 (40.4%) did not receive them (range: 21.3% in New York to 62.3% in Georgia). Reasons for unmet needs were multifactorial and varied by jurisdiction. Available 2019 HOPWA funding per person in need would cover up to 1.24 months of rent per person nationally (range: 0.53 months in Virginia to 9.54 months in Puerto Rico), and may not have matched housing assistance needs among PWH in certain jurisdictions.

Conclusion:

Addressing housing service needs necessitates a multipronged approach at the provider, jurisdiction, and national level. Locally, jurisdictions should work with their partners to understand and address housing service needs among PWH. Nationally, distribution of HOPWA funding for housing services should be aligned according to local needs; the funding formula could be modified to improve access to housing services among PWH.

Keywords: HIV, Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS, housing instability, housing services

Graphical Abstract

Background

Adequate housing is a basic human right and serves as a foundation for maintaining physical and mental health [1]. Yet, 17% of people with HIV (PWH) recently experienced homelessness or other forms of unstable housing [2], which are associated with suboptimal outcomes [3,4]. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy underscores the importance of addressing unstable housing in meeting national HIV goals [5]. However, jurisdictions have room for improvement in reducing unstable housing among PWH, indicating that housing service needs in this population are not being fully met [6].

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funds the Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS (HOPWA) Program, the only federally funded program dedicated to addressing housing service needs among PWH [7]. Overall, 90% of HOPWA funds are allocated to jurisdictions based on a formula accounting for number of HIV cases, poverty rates, and fair market rent (FMR) prices – defined as the basic cost of rent for adequate housing in a specified area [8].

Access to shelter or housing assistance is a function of many individual-level, community-level, and systems-level factors, including stigma associated with receiving services; service availability; logistical challenges such as required documentation and waitlist length; and funding availability [9]. To help address gaps in housing assistance services for PWH, we used representative data to describe: the prevalence of needs for shelter or housing assistance among PWH, reasons for unmet needs, and availability of HOPWA funding with respect to need, nationally and for 17 US jurisdictions.

Methods

Data source

The CDC Medical Monitoring Project (MMP) collects annual, cross-sectional data and is the only source of representative data on social determinants of health and barriers to care and viral suppression among US adults with diagnosed HIV. During the 2015–2019 annual data cycles, interview data were collected during June of each cycle year through May of the following year. MMP uses a complex sample survey design that allows for reporting of nationally and locally representative estimates among PWH. More details on MMP methodology are described elsewhere [2]. MMP is part of routine surveillance and considered nonresearch; institutional review board approval was obtained as needed, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Participants were asked whether they received shelter or housing assistance during the past 12 months; those who did not receive it were asked if they needed shelter or housing assistance. Met need was defined as receiving shelter or housing assistance; unmet need was defined as not receiving, but needing, shelter or housing assistance. Total need included met and unmet need. Participants who reported having an unmet need were asked about reasons for not receiving services. Participants could report more than one reason.

Analytical methods

We reported weighted percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for national and jurisdiction-level estimates of needs for shelter or housing assistance – including total need, unmet need, and met need – and reasons for unmet needs.

Jurisdiction-level estimates of unmet needs for shelter or housing assistance were calculated among PWH who needed services (i.e. those who had a met or unmet need). Jurisdictional estimates for total need, unmet need, and met need were categorized into: ‘high’ needs: those with 95% CI bounds exceeding the 95% CI bounds of the national estimate, ‘medium’ needs: those with 95% CI bounds overlapping with that of the national estimate, and ‘low’ needs: those with 95% CI bounds falling below the 95% CI bounds of the national estimate.

Publicly available 2019 HUD data were obtained on total awarded HOPWA funds and FMR prices [10,11]. Using these HUD data and weighted MMP estimates of total PWH who needed shelter or housing assistance during the 2019 data cycle, we calculated: the estimated dollar amount from HOPWA funds available for each person who needed housing assistance, and the estimated number of months of rent covered based on this dollar amount, using a comparison with the average cost of FMR per month. Point estimates and 95% CIs were presented nationally and by jurisdiction.

Data were weighted based on known probabilities of selection, were adjusted for person nonresponse, and poststratified to known population totals from the National HIV Surveillance System by age, race/ethnicity, and sex, based on previously described, standard methodology [2]. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Needs for shelter or housing assistance

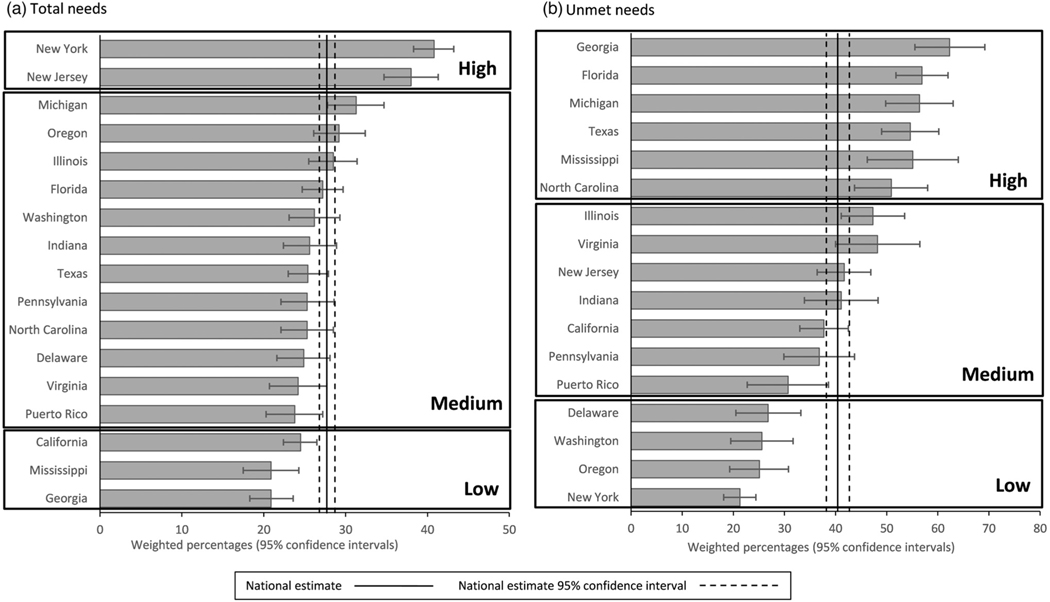

Nationally, over 1 in 4 (27.7%) PWH had shelter or housing service needs; jurisdiction-level estimates ranged from 20.9% in Georgia and Mississippi to 40.8% in New York (Fig. 1a). Among those with shelter or housing service needs, 40.4% had a need that was not met (Fig. 1b; Appendix Table 1, http://links.lww.com/QAD/C787).

Fig. 1. Prevalence of (a) total needs and (b) unmet needs for housing or shelter assistance among adults with diagnosed HIV, by jurisdiction–—United States, 2015–2020.

(a) Total need was defined as the sum of met and unmet needs for shelter or housing assistance. Jurisdictions were ordered in decreasing order of prevalence of total need for housing or shelter assistance. (b) Unmet need was defined as needing, but not receiving shelter or housing assistance, and was calculated among those who reported any need for shelter or housing assistance. Jurisdictions were ordered in decreasing order of prevalence of unmet needs for housing or shelter assistance. Jurisdictions are grouped into three categories: ‘High’ includes jurisdictions for which the bounds of the 95% CIs exceed the bounds of the 95% CI of the national estimate; ‘Medium’ includes jurisdictions for which the 95% CI overlaps with that of the national estimate; ‘Low’ includes jurisdictions for which the bounds of the 95% CIs fall below the bounds of the 95% CIs of the national estimate. CI, confidence interval.

Among PWH who indicated having a shelter or housing service need, jurisdiction-level estimates for unmet need ranged from 21.3% in New York to 62.3% in Georgia. Five out of seven reporting Southern jurisdictions had high unmet need (range: 50.9–62.3%), despite all seven having low or medium total need.

Reasons for unmet needs for shelter or housing assistance

Of PWH with an unmet need for shelter or housing assistance, 51% reported not being able to find the information needed to get the service or they did not know the service existed; 40% said the service did not meet their needs or they were not eligible for the service; 21% cited personal reasons, such as fear or embarrassment, or having other things going on in life that made it difficult to receive the service; and 23% reported more than one reason for not receiving housing assistance (Appendix Table 2, http://links.lww.com/QAD/C788). Reasons for unmet needs varied by jurisdiction.

Estimated funding availability for shelter or housing assistance through Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS

Based on an estimated 267 350 PWH who needed shelter or housing assistance during 2019, $1416 of HOPWA funding was available per person who needed services during 2019 (Table 1). Given the national cost of FMR per month was $1143, HOPWA funding per person in need would cover up to 1.24 months of rent overall (95% CI 1.08–1.45). The number of months of rent covered per person varied by jurisdiction, ranging from 0.53 months (95% CI 0.41–0.74) in Virginia to 9.54 months in Puerto Rico (95% CI 6.70–16.58). Funding availability may not have matched needs for housing assistance in certain jurisdictions.

Table 1.

Distribution of Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS (HOPWA) program funds per person with HIV in need of shelter or housing assistance with respect to fair market rent (FMR) prices, nationally and by jurisdiction–—United States, 2019.

| Region | State | HOPWA funds awarded for FY 2019 | Estimated number of people with HIV who needed shelter or housing assistance |

Available HOPWA funds per person with HIV who needed shelter or housing assistance |

Fair market rent/month | Number of months of rent covered per person, based on available HOPWA funds and fair market rent/month |

Category of total need | Category of unmet need | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point estimate | 95% Cl | Point estimate | 95% Cl | Point estimate | 95% Cl | ||||||

| National | $378,435,991 | 267,350 | (227,841–306,859) | $1,415.51 | ($1,233.26-$1,660.97) | $1143.11 | 1.24 | (1.08, 1.45) | – | – | |

| South | Delaware | $1,846,472 | 643 | (437–813) | $2,871.43 | ($2,271,18-$4,225.34) | $1137.72 | 2.52 | (2.00, 3.71) | Medium | Low |

| Florida | $43,123,614 | 22,327 | (16,441–28,212) | $1,931.46 | ($1,528.56-$2,622.93) | $1171.78 | 1.65 | (1.30, 2.24) | Medium | High | |

| Georgia | $28,411,051 | 11,619 | (8,482–14,756) | $2,445.22 | ($1,925.39-$3,349.57) | $952.08 | 2.57 | (2.02, 3.52) | Low | High | |

| Mississippi | $2,930,861 | 1,335 | (578–2,091) | $2,195.40 | ($1,401,66-$5,070.69) | $743.16 | 2.95 | (1.89, 6.82) | Low | High | |

| North Carolina | $7,643,040 | 6,705 | (4,666–8,744) | $1,139.90 | ($874.09-$1,638.03) | $867.93 | 1.31 | (1.01, 1.89) | Medium | High | |

| Texas | $27,646,794 | 21,403 | (16,398–26,407) | $1,291.73 | ($1,046.95-$1,685.99) | $1,029.24 | 1.26 | (1.02, 1.64) | Medium | High | |

| Virginia | $3,995,258 | 6,330 | (4,524–8,136) | $631.16 | ($491,06-$883.13) | $1,196.52 | 0.53 | (0.41, 0.74) | Medium | Medium | |

| Midwest | Illinois | $12,629,511 | 8,487 | (6,580–10,395) | $1,488.10 | ($1,214.96-$1,919.38) | $1,070.91 | 1.39 | (1.13, 1.79) | Medium | Medium |

| Indiana | $2,829,351 | 4,054 | (3,169–4,940) | $697.92 | ($572.74-$892.82) | $823.35 | 0.85 | (0.70, 1.08) | Medium | Medium | |

| Michigan | $5,189,991 | 4,834 | (3,495–6,173) | $1,073.64 | ($840.76-$1,484.98) | $883.46 | 1.22 | (0.95, 1.68) | Medium | High | |

| West | California | $50,696,231 | 31,173 | (25,677–36,670) | $1,626.29 | ($1,382.50-$1,974.38) | $1,754.88 | 0.93 | (0.79, 1.13) | Low | Medium |

| Oregon | $4,380,390 | 2,414 | (1,846–2,981) | $1,814.58 | ($1,469.44-$2,372.91) | $1,182.50 | 1.53 | (1.24, 2.01) | Medium | Low | |

| Washington | $3,680,884 | 2,806 | (1,914–3,698) | $1,311.79 | ($995.37-$1,923.14) | $1,399.35 | 0.94 | (0.71, 1.37) | Medium | Low | |

| Northeast | New Jersey | $12,566,464 | 14,159 | (11,553–16,766) | $887.52 | ($749.52-$1,087.72) | $1,485.42 | 0.60 | (0.50, 0.73) | High | Medium |

| New York | $51,611,858 | 49,875 | (41,922–57,827) | $1,034.82 | ($892,52-$1,231.14) | $1,519.84 | 0.68 | (0.59, 0.81) | High | Low | |

| Pennsylvania | $11,961,448 | 6,983 | (4,709–9,258) | $1,712.94 | ($1,292.01-$2,540.12) | $995.78 | 1.72 | (1.30, 2.55) | Medium | Medium | |

| Territory | Puerto Rico | $8,375,890 | 1,766 | (1,016–2,516) | $4,742.86 | ($3,329.05-$8,243.99) | $497.21 | 9.54 | (6.70, 16.58) | Medium | Medium |

CI, confidence interval; HOPWA, Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS. Notes: FY 2019 HOPWA funding data were obtained from the HUD website: https://www.hudexchange.info/grantees/allocations-awards/?csrf_token=0562DAC9–3B5A-4B1F-A3249538FD5AEF1D¶ms=%7B%22limit%22%3A20%2C%22COC%22%3Afalse%2C%22sort%22%3A%22%22%2C%22min%22%3A%22%22%2C%22years%22%3A%5B%7B%22year%22%3A2019%2C%22%24%24hashKey%22%3A%22object%3A102%22%7D%5D%2C%22dir%22%3A%22%22%2C%22grantees%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22state%22%3A%22%22%2C%22programs%22%3A%5B8%5D%2C%22max%22%3A%22%22%2C%22searchTerm%22%3A%22%22%2C%22multiStateAwards%22%3A0%2C%22orgid%22%3A%22%22%2C%22orgname%22%3A%22%22%7D##granteeSearch. Data on county-level fair market rent (FMR) prices for 2019 were available here: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/fmr/fmrs/FY2019_code/select_Geography.odn. FMRs were calculated by HUD for all U.S. counties and municipalities in Puerto Rico to determine the amount of housing funds per person, based on the cost of a 2-bedroom unit (because of assumptions made for the HOPWA funding formula). FMRs were weighted based on county (municipality, for Puerto Rico) population size to account for differences in cost of living by urbanicity. Some counties in New England were further divided into town-based metro area definitions; these were assumed to be separate and distinct entities in FMR calculations. Jurisdictions are grouped into three categories: “High” includes jurisdictions for which the bounds of the 95% CIs exceed the bounds of the 95% CI of the national estimate; “Medium” includes jurisdictions for which the 95% CI overlaps with that of the national estimate; “Low” includes jurisdictions for which the bounds of the 95% CIs fall below the bounds of the 95% CIs of the national estimate.

Discussion

Nationally, over one in four PWH had a need for shelter or housing assistance, of whom two in five had a need that was not met; unmet needs varied by jurisdiction, with the highest unmet needs in Georgia. Reasons for unmet needs were often multifactorial and varied by jurisdiction. Federal housing funds per PWH in need varied by jurisdiction and may not have matched housing assistance needs in certain jurisdictions – potentially contributing to substantial unmet need in some areas.

Addressing housing service needs early, such as through rapid-rehousing programs, is critical and cost effective [12]. A multipronged approach may be needed to address barriers to housing assistance services. At the facility level, providers should routinely assess housing status among HIV patients, per clinical guidelines [13]. Co-locating housing services within ‘one-stop shop’ facilities that offer other services ensures provision of wraparound services to address needs among PWH. Onsite patient navigation could also help address logistical challenges to receiving services, including documentation requirements. Local availability of housing assistance services should also be geographically located based on need and could be co-located with other services (e.g. HIV care) to ensure a ‘whole person’ approach. If housing services are not co-located with HIV care services, strong, well-established referral relationships between HIV providers and local housing programs could facilitate seamless provision of services.

Within jurisdictions, facilitating collaborations between local housing providers and HIV care providers may help in addressing barriers to care and learning from others’ experiences. In addition, appropriate allocation and oversight of resources maximizes benefit for those in need and promotes trust in local government. For instance, Georgia had the lowest total need but the highest unmet need of those who needed housing assistance services. Based on a 2019 HUD investigation, Atlanta has had documented issues with meeting certain federal requirements or standards while providing housing resources to PWH using HOPWA funds [14,15]. The existing infrastructure for provision of housing services in Atlanta, which has a substantial number of PWH [16], limits the number of people who receive services based on dedicated federal housing funds.

Nationally, the HOPWA funding formula could be modified to ensure that funds are distributed equitably based on need. For instance, eligibility criteria for receiving HOPWA funds include living at or below 80% of the area median income, even though people living above that threshold may also need housing services. FMR prices also dictate the available housing units that can be rented using HOPWA funds, which could limit the ability to find rental units that are adequate, well tolerated, and clean. Recent increases in households competing for rental units with respect to housing availability, as well as increases in rental prices over time, have contributed to a general lack of affordable housing [17,18], which may have been exacerbated following the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [18,19]. The HOPWA funding formula does not account for local poverty rates among PWH, which may be higher than among the general population [2,7,20]. Future formulas could incorporate poverty rates among PWH using data from MMP or the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. HOPWA funding also does not account for cost of living, which is vastly different across jurisdictions, and even within a jurisdiction. Granular data on FMR prices weighted by population size and urbanicity would more accurately portray local housing costs and could also be incorporated into the formula.

This analysis had some limitations. Estimates on available funding for shelter or housing assistance per person did not account for other funding sources, so were likely an underestimate of overall available funds. Nationally, approximately 71% of HOPWA funds [8,21–23] were spent on housing assistance during 2017–2019, and therefore the allocated funding amount represents an upper limit of available housing assistance resources for PWH. Distribution of other expenditures (e.g. administration and management) could depend on local circumstances [9]. Not all sampled persons participated in MMP, but results were adjusted for nonresponse using standard methodology [2]. Persons experiencing unstable housing may have been less likely to participate, resulting in a lower bound of estimates for housing assistance needs.

In conclusion, addressing housing service needs is essential for meeting national HIV goals. However, this analysis demonstrated that over one in four PWH needed housing assistance, and 40% of PWH who needed housing assistance did not receive it; unmet needs were particularly high in Southern reporting jurisdictions. Addressing shelter and housing service needs necessitates a multipronged approach at the facility, jurisdiction, and national level. Locally, jurisdictions should work with their partners to address housing service needs among PWH. Nationally, the HOPWA funding formula could be modified to ensure distribution of funds aligns with local need.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge local MMP staff, health departments, and participants, without whom this research would not be possible. We also acknowledge Linda Koenig from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Rita Harcrow, Rebecca Blalock, and Claire Donze from the Department of Housing and Urban Development for their insightful consultation on this analysis.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: the findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/03/udhr.pdf.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral and Clinical Characteristics of Persons with Diagnosed HIV Infection–—Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2020 Cycle (June 2020–May 2021). 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcus R, Tie Y, Dasgupta S, Beer L, Padilla M, Fagan J, et al. Characteristics of adults with diagnosed HIV who experienced housing instability: findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2018. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2021; 33:283–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wainwright JJ, Beer L, Tie Y, Fagan JL, Dean HD, Medical Monitoring Project. Socioeconomic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of persons living with HIV who experience homelessness in the United States, 2015–2016. AIDS Behav 2020; 24:1701–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The White House. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States 2022–2025. 2021. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/national-hiv-aids-strategy/national-hiv-aids-strategy-2022-2025.

- 6.Dasgupta S, Tie Y, Beer L, Johnson Lyons S, Shouse RL, Harris N. Geographic differences in reaching selected national HIV strategic targets among people with diagnosed HIV: 16 US States and Puerto Rico, 2017–2020. Am J Public Health 2022; 112:1059–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Housing and Urban Development. HOPWA Eligibility Requirements. https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/hopwa/hopwa-eligibility-requirements/.

- 8.Department of Housing and Urban Development. HOPWA Formula Modernization. http://www.meeting-support.com/downloads/244402/10944/PPT%20V2.pdf.

- 9.Wusinich C, Bond L, Nathanson A, Padgett DK. ‘If You’re Gonna Help Me, Help Me’: barriers to housing among unsheltered homeless adults. Eval Program Plann 2019; 76:101673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Housing and Urban Development. FY 2019 Fair Market Rents Documentation System. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/fmr/fmrs/FY2019_code/select_Geography.odn.

- 11.Department of Housing and Urban Development. HUD Awards and Allocations. https://www.hudexchange.info/grantees/allocations-awards/?csrf_token=0562DAC9-3B5A-4B1F-A3249538FD5AEF1D¶ms=%7B%22limit%22%3A20%2C%22COC%22%3Afalse%2C%22sort%22%3A%22%22%2C%22min%22%3A%22%22%2C%22years%22%3A%5B%7B%22year%22%3A2019%2C%22%24%24hashKey%22%3A%22object%3A102%22%7D%5D%2C%22dir%22%3A%22%22%2C%22grantees%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22state%22%3A%22%22%2C%22programs%22%3A%5B8%5D%2C%22max%22%3A%22%22%2C%22searchTerm%22%3A%22%22%2C%22multiStateAwards%22%3A0%2C%22orgid%22%3A%22%22%2C%22orgname%22%3A%22%22%7D##granteeSearch.

- 12.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Homelessness Resources: Housing and Shelter. https://www.samhsa.gov/homelessness-programs-resources/hpr-resources/housing-shelter.

- 13.Department of Health and Human Services. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/archive/AdultandAdolescentGL_2021_08_16.pdf.

- 14.Mariano W. Clients Scramble for Shelter as HIV Program in Limbo. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 2021. https://www.ajc.com/news/atlanta-news/clients-scramble-for-shelter-as-hiv-program-in-limbo/JM72X4LUWFGERHC3W5RQED7NYY/#:~:text=Nearly%20two%20years%20ago%2C%20a,millions%20of%20dollars%20in%20funding. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mariano W. Leaked memo shows depth of dysfunction in Atlanta’s AIDS housing crisis. Atlanta Journal-Constitution. 2019. https://www.ajc.com/news/local-govt–politics/leaked-memo-shows-depth-dysfunction-atlanta-aids-housing-crisis/B2p7JktPzSD00ncGP8tEjJ/#:~:text=Leaked%20memo%20shows%20depth%20of%20dysfunction%20in%20Atlanta’s%20AIDS%20housing%20crisis,-Caption&text=Just%20as%20a%20crisis%20in,hint%20of%20who%20sent%20it. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2020; vol. 33. Published May 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-33/index.html.

- 17.Government Accountability Office. Rental Housing: as more households rent, the poorest face affordability andhousing quality challenges. 2020. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-427.pdf.

- 18.U.S. Census Bureau. Quarterly residential vacancies and homeownership, First Quarter 2022. https://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/files/currenthvspress.pdf.

- 19.Benfer EA, Vlahov D, Long MY, Walker-Wells E, Pottenger JL Jr, Gonsalves G, et al. Eviction, health inequity, and the spread of COVID-19: housing policy as a primary pandemic mitigation strategy. J Urban Health 2021; 98:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Census Bureau. 2019 American Community Survey Statistics for Income, Poverty and health insurance available for states and local areas. 2020. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/acs-1year.html#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20the%20ACS%20national,of%20the%20ACS%20in%202005.

- 21.Department of Housing and Urban Development. HOPWA Performance Profile - Quarterly Summary (2019). https://files.hudex-change.info/reports/published/HOPWA_Perf_NatlComb_2019.pdf.

- 22.Department of Housing and Urban Development. HOPWA Performance Profile - National Q4 YTD (2017). https://files.hudexchange.info/reports/published/HOPWA_Perf_NatlComb_2017.pdf.

- 23.Department of Housing and Urban Development. HOPWA Performance Profile - National Program YTD Summary (2018). https://files.hudexchange.info/reports/published/HOP-WA_Perf_NatlComb_2018.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.