Abstract

Intelligent biodegradable packaging has gained significant attention recently due to its great potential for food freshness monitoring. In this study, we developed intelligent labels using pea starch (PS), κ-carrageenan (KC) and black raspberry extract (BRE) and evaluated their physicochemical properties and effectiveness in pork freshness monitoring. Incorporation of KC significantly decreased tensile strength (TS) (33.43 to 19.84 MPa) and increased elongation at break (EAB) (6.26 to 7.41 %) and water vapor permeability (WVP) (2.11 to 2.48 × 10−9 g m−1 s−1 Pa−1) of PS label. Incorporation of BRE significantly decreased WVP (2.48 to 1.96 × 10−9 g m−1 s−1 Pa−1) and increased TS (19.84 to 29.68 MPa) and EAB (7.41 to 11.09 %) of PS-KC label. PS-KC-BRE labels showed increased light barrier performance, thermal stability, antioxidant activity, pH and ammonia sensitivities, and significant visible color change as pH indicators. Findings suggest PS-KC-BRE labels can be used as intelligent packaging in food industry.

Keywords: Anthocyanin, Black raspberry, Characterization, Intelligent label, κ-Carrageenan

Highlights

-

•

Intelligent labels were prepared by blending pea starch with κ-carrageenan.

-

•

The intelligent labels were based on anthocyanin-rich black raspberry extract.

-

•

The labels had excellent light barrier performance and antioxidant activity.

-

•

The labels showed great potential in monitoring pork freshness.

1. Introduction

Spoilage of protein-rich food due to enzymatic reaction and microbial metabolism has resulted in a significant food resource waste and poses a great threat to human health (Zhang, Zhang, et al., 2024). Conventional methods such as chemical assays and microbiological techniques have been extensively used in food spoilage detection, playing a vital role in safeguarding food quality. However, these approaches are time-consuming, frequently destructive, and need expert determining equipments, which are unsuitable for supermarket retails (Jiang et al., 2024). Therefore, it is greatly urgent to built a fast, visual, and non-destructive method to determine the meat freshness (Elhadef et al., 2024). Nowadays, polymer-based intelligent packaging has gained great attention due to it can real-timely detect food freshness without destroying or losing the packaged foods. These innovative labels consist of pH-sensitive materials that can undergo distinct color changes in response to shifts in the surrounding acidity or alkalinity levels.

Petrochemical-based polymers are commonly used as raw materials in intelligent packaging. However, owing to their non-biodegradable nature, there is a great inclination toward biodegradable ones (Gupta et al., 2024). Starch, as a promising biopolymer, is frequently used as packaging materials due to its low price, abundance, edible, and eco-friendliness. Pisum sativum L., known as pea, is cultivated in almost all countries around the world. Pea is rich in protein, carbohydrate, vitamin, mineral, and bioactive compounds that are beneficial to human health. Pea starch (PS), usually a by-product of protein extraction, accounts for over 50 % of the dry weight (Luo et al., 2024). Because of high amylase content, labels created using pea starches showed more enhanced structural integrity, barrier characteristics and mechanical property than that of other starches (Mueller et al., 2024). However, owning to the abundant OH groups in it, the starch-based label was hydrophilic, which limited its applications in practical fields (Zhou et al., 2021). It has been demonstrated that using of combined biopolymers can overcome some inherent drawbacks of single-component starch-based labels such as high hydrophilicity and insufficient mechanical properties (Narasagoudr et al., 2023). Carrageenan, found in several species of red seaweeds, belongs to the Rhodophyta family with large molecules of sulfated polysaccharides. Carrageenan can be classified into different types (kappa, iota or lambda) based on the galactose bond conformation and the numbers and position of the sulfate groups. As one of important natural biopolymers, kappa-carrageenan (KC) stands out as an up-and-coming option in developing of intelligent packaging labels because of its excellent natural abundance, biodegradable property and film-formation ability.

Synthetic colors such as methyl red and bromocresol green are commonly used as pH-sensitive indicators in development of intelligent packaging. However, owing to their toxicity and environmental impacts, research has moved toward the use of natural, non-toxic, eco-friendly pigments (Jebel et al., 2025). As one important kind of water-soluble flavonoids, anthocyanins exist in various vegetables, fruits and flowers with purple, magenta, orange, blue and red colors. Anthocyanins have attracted increasing interest as pH-sensitive indicators because of their good biocompatibility, potent antioxidant activity and outstanding color changing capability in a wide pH range (Liang et al., 2024). Black raspberry (Rubus occidentalis), belonging to the family of Rosaceae, is cultivated in America, China and southeast Asian countries (Xiao et al., 2017). Black raspberries are rich in various biological compounds including tannin, anthocyanin, polyphenol, phenolic acid and inorganic substances. Black raspberry is an excellent source of natural pigments and antioxidants, which is one of the major reasons for their increasing popularity in the human diet such as fresh or as-processed products including wines, syrups, jellies and jams. Till now, anthocyanins derived from various berries, including R. jamaicensis (black berry) and R. rosifolius (red raspberry) are employed for developing pH-responsive intelligent labels. Nevertheless, the use of anthocyanin-rich black raspberry extract as a pH-sensitive indicator in intelligent packaging has not been reported yet.

Therefore, in this study, the pea starch (PS), κ-carrageenan (KC) and black raspberry extract (BRE) was selected to prepare intelligent labels. The effects of the addition of KC and BRE on the physical and functional properties of the intelligent labels were evaluated. Additionally, the microstructure of the intelligent labels was analyzed using the SEM, XRD and FT-IR technologies. Finally, the intelligent labels were used to monitor the pork quality. The investigation provided a new insight for development and applications of intelligent labels for monitoring the freshness of protein-based products.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

Pea starch, black raspberry and pork were bought from a local supermarket in the Huaian city (Huaian, China). Glycerol, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazine (DPPH) and κ-carrageenan were purchased from Huaian Chinese medicine Chemical reagent Co., Ltd. (Huaian, China). 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox) was obtained from Huaian Kaitong Chemical reagent Co., Ltd. (Huaian, China). All other reagents used were of analytical grade.

2.2. Extraction of anthocyanins

The anthocyanins in black raspberry were extracted according to Jiang, Liu, Wang, Zou, Cao et al. (2023). Briefly, 50 g of black raspberry was washed well in water, homogenized and extracted twice for 24 h at 4 °C with 500 mL 80 % ethanol solution containing 1 % HCl (v/v). The extracting solution was combined together and centrifuged at 4000 rpm and 4 °C for 15 min. The obtained supernatant was purified with an AB-8 macroporous resin column, which was eluted with 80 % ethanol solution containing 1 % HCl (v/v) and concentrated using a vacuum rotatory evaporator at 30 °C, affording black raspberry extraction (BRE). The total anthocyanin contents in BRE solution and black raspberries were determined using pH differential assay. The resulting BRE solution was kept in a 5 °C refrigerator until it was used to develop intelligent labels.

2.3. Preparation of labels

The PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels were prepared following the method of Cao et al. (2023) with some modifications. Firstly, PS (4.5 g) and glycerol (1.25 g) were dissolved in distilled water (150 mL), stirring-heated in a 95 °C water bath for 30 min to obtain gelatinized PS blend. Subsequently, 1.35 g of KC was incorporated to PS blend with constant stirring at 95 °C for 30 min. When these mixtures were cooled below 35 °C, BRE solution with various amounts (0, 2, 3 and 4 mL/g, on PS basis) was incorporated and stirred in a homogenizer for 30 min. The obtained blends containing 0, 2, 3 and 4 mL/g of BRE solution were termed as PS-KC, PS-KC-BRE-I, PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III, respectively. Meanwhile, blend of PS without BRE solution and KC was prepared in the same manner and termed as SP label. After ultrasonic degassing, the blends were cast on a 24 cm × 24 cm Plexiglas plate. All the plates were dried in a water bath at 30 °C for 48 h. Dried labels were peeled off and stored in a desiccator with 4 °C and 50 % relative humidity (RH) for 36 h before testing.

2.4. Determination of the physical properties of labels

2.4.1. Thickness and color

Label thickness was measured by a WD caliper with accuracy of 0.001 mm. Color parameters of labels, expressed as L⁎, a⁎, b⁎ values, were recorded by a NR10QC chromometer (3NH, Shenzhen, China). The total color difference (ΔE) for each label was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where ΔL, Δa and Δb were difference between each color value of labels and white plate with L (92.6), a (−0.92) and b (−2.24). For ΔE < 2.3 labels were equal in terms of color and if ΔE > 2.3 then labels were different in colors.

2.4.2. Light transmittance

The light transmittance through the labels was assessed on a Shimadzu UV 3600 spectrometer. The spectra were recorded from 200 to 700 nm.

2.4.3. Water vapor permeability (WVP)

A 50 mL centrifuge tube containing 30 g of anhydrous silica gels was capped with 5 cm × 5 cm label samples and put into a desiccator containing distilled water at 25 °C and 100 % RH. Weight was recorded every 24 h for a week. WVP of label samples was calculated as follows:

| (2) |

Where A was permeation area (m2), ΔP was saturated vapor pressure at 20 °C, t was time (s), W was the weight gain of tube (g), and x was label thickness (m).

2.4.4. Mechanical property

Tensile strength (TS) and elongation at break (EAB) of labels were evaluated by following the Chinese national standard of GB/T 1040.3–2006. Label samples were cut into rectangular shapes of 1 cm × 4 cm and tested using a Brookfield CT3 Texture Analyzer. The clamp speed and gauge length used were 1 mm/s and 40 mm, respectively.

2.4.5. Thermogravimetric property

The thermogravimetric property of labels was measured by a thermal gravimetric analyzer of TG 209 from the Netzsch company. Label samples were weighed in a platinum dish and subjected to heating at a heating rate of 10 K/min from 20 to 800 °C.

2.5. Determination of the functional properties of labels

2.5.1. Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant ability of labels was evaluated by determining their scavenging ability on DPPH radicals. Label samples (4–20 mg) were added into 4.0 mL of DPPH ethanol solution with a concentration of 100 μM. After 30 min of reaction time in darkness at room temperature, the absorbance at 517 nm was measured using a Shimadzu UV 3600 spectrometer. The scavenging percentage of labels was calculated as the following equation:

| (3) |

where A0 was the absorbance of blank solution, and A1 was for reaction solution. Percent values of the test samples were transformed in Trolox Equivalents (μg/mL) by using the calibration curve which was prepared using Trolox ethanolic solution (4–24 μg/mL) (y = 3.4455x – 2.7202, R2 > 0.99).

2.5.2. pH-sensitivity

Pieces of the label sample (2 cm × 2 cm) were in put into pH value 2–13 of buffer solution for 1 min at 25 °C. The sample color was photographed with a digital camera.

2.5.3. Ammonia-sensitivity

To test the ammonia-sensitivity of labels, samples were cut into pieces (2 cm × 2 cm), which were attached to the headspace of petri dish filled with 15 mL 0.1 M ammonia solution for 1 h. Color of the labels was photographed every 10 min with a digital camera.

2.6. Structural characterization of labels

The PS, PS-CK as well as PS-CK-BRE labels were characterized according to the methods of Cao et al. (2023) with some modifications. The cross-section microstructure of labels was examined by SEM (Phenom Pro, Phenom World, Netherlands) at an accelerating voltage of 5 KV. X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra were conducted on a D8 Discover diffractometer (Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany) using CuK-α radiation scanning from 5° to 80° (2θ). FT-IR spectra of labels were scanned from 4000 to 650 cm−1 on a Nicolet 5700 FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet Corporation, USA).

2.7. Application of labels

Fresh samples (20 ± 0.1 g) were put into a transparent plastic box (15 cm × 10 cm × 8 cm). Meanwhile, the 1 cm × 2 cm label strip was put on the headspace of the box and did not contact with meat samples. The box was sealed and the packaged samples were placed in a constant temperature and humidity chamber at 20 °C and 50 %RH for 60 h. At different storage times, the color of label samples was captured with a digital camera. Total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N) was measured every 12 h by using a Kjeldahl method.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All the data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software 8.0.1) was used for the statistical analysis including one-way analysis and Duncan test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of BRE

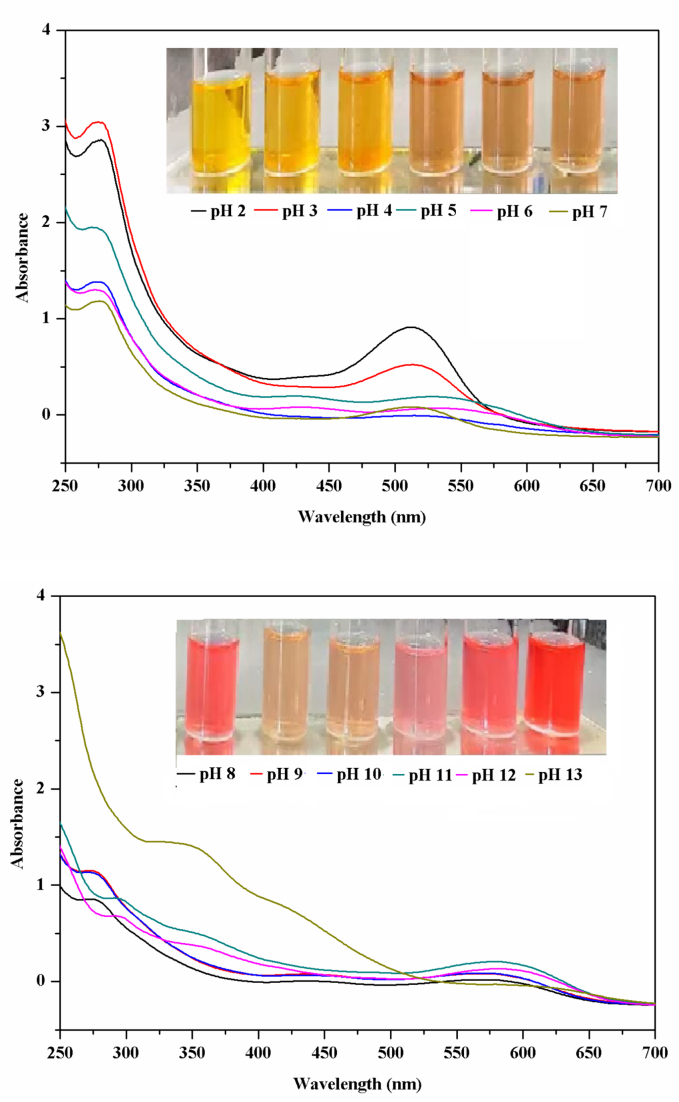

The anthocyanin in black raspberries was 4.47 mg/g, consistent with the results found in our previous report on the anthocyanin content of black currant fruit (3.58 mg/g) (Jiang et al., 2024). To assess the feasibility of BRE as pH-sensitive indicators in label fabrication, the color change of BRE was tested when immersed in various pH buffers (pH 2–13). As shown in Fig. 1, BRE presented different colors from yellow to red at various pHs from 2 to 13. In high acid conditions (pH 2–3), color of BRE was rich yellow. It became light yellow when the pH was 5 and 7. When pH values increased from 8 to 10, the solution turned its color from red to orange. When pH was increased to 12 and 13, the BRE solution presented red color again. The color change of BRE in different pH buffer solutions was resulted from structural transformations of the anthocyanin molecules. Fig. 1 shows the UV–vis spectrum of BRE solution under different pHs. The BRE solution showed obvious absorption in the UV region of 270–330 nm when pH was 2–13. Similar result was obtained in our earlier research on black currant extract's pH-sensitivity (Jiang et al., 2024). The largest absorption peak appeared between 400 and 700 nm at various pHs from 2 to 6, indicating that the predominant form of anthocyanins in the acidic solution was the flavylium cation (AH+), which gave the solution a yellow color. As the BRE solution pH was at 7–13, the maximum absorption peak became dropped off and shifted to 585 nm. Similar phenomenon was found in a previously reported study (Wu, Yan, Zhang, Wu, Luan, & Zhang, 2024). These findings further confirmed the close relationship between the color changes and structural transformations of anthocyanins under different acid-base solutions. And the properties of color response to pH change highlighted its potential as a practical pH-sensitive color indicator.

Fig. 1.

Color change and UV–vis spectra of BRE in different buffer solutions (pH 2 to 13).

3.2. Physicochemical properties of labels

3.2.1. Thickness and color

As shown in Table 1, the PS label had a thickness of 0.079 mm, while the thickness of PS-KC label was 0.066 mm, indicating significant difference in thickness between the PS and PS-KC labels. This might be due to the fact that the hydrophilic KC could be better distributed and bind to the matrix in the label solution, resulting in the decreased thickness of the composite label. The thickness of the PS-KC-BRE labels (0.083–0.085 mm) was markedly increased compared to that of the PS-KC label (0.066 mm) (p < 0.05). The increased thickness of the PS-KC-BRE labels was due to that the incorporation of BRE prolonged the spatial distance of label substrate and destroyed the original crystal structures of labels. No difference was found in thickness among PS-KC-BRE-I, PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III labels, indicating the thickness of PS-KC-BRE labels was not affected by the BRE addition content when the BRE addition content was ranged from 2 mL/g to 4 mL/g. Kan et al. (2022) found that there were no significant differences in thickness between the starch-based labels with and without plant extract. Nogueira et al. (2024) also found the thickness of arrowroot starch based labels did not change as different amounts of grape pomace extract were added into the label. However, significant thickness increase was found by Zhang, Huang, et al. (2020) when 1.0 % of purple sweet potato extract or red cabbage extract was added into starch/polyvinyl alcohol labels.

Table 1.

Thickness, WVP and mechanical property of PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels.

| Films | Thickness (mm) |

WVP (10−9 g m−1 s−1 Pa−1) |

Mechanical property |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS (MPa) |

EAB (%) |

|||

| PS | 0.079 ± 0.01 a | 2.11 ± 0.2 b | 33.43 ± 2.13 a | 6.26 ± 0.43 d |

| PS-KC | 0.066 ± 0.05 b | 2.48 ± 0.2 a | 19.84 ± 1.35 e | 7.41 ± 0.21 c |

| PS-KC-BRE-I | 0.083 ± 0.01 a | 2.57 ± 0.5 a | 29.68 ± 1.49 b | 8.23 ± 1.11 c |

| PS-KC-BRE-II | 0.084 ± 0.01 a | 1.96 ± 0.2 b | 27.51 ± 1.74 c | 9.72 ± 1.07 b |

| PS-KC-BRE-III | 0.085 ± 0.00 a | 1.98 ± 0.1 b | 24.73 ± 0.88 d | 11.09 ± 1.12 a |

PS: pea starch label; PS-KC: pea starch/κ-carrageenan label; PS-KC-BRE-I, PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III: pea starch/κ-carrageenan labels containing 2, 3 and 4 mL/g of black raspberry extraction (on pea starch basis), respectively. Values are given as mean ± standard deviation. Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

The color of PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels is shown in Table 2. PS and PS-KC labels were visually transparent. However, the color of PS-KC-BRE labels was brown. And the color was deepened when the content of BRE incorporated was increased. Color parameters of labels were further measured using a white paper with L (89.98), a (−0.6) and b (−3.4) as blank control. The label color parameters including L⁎, a⁎, b⁎ and ΔE are shown in Table 2. ΔE values of PS and PS-KC labels were 0.53 ± 0.03 and 3.73 ± 0.13 (> 2.3) respectively, indicating significant differences in colors between PS and PS-KC labels. The significant total difference between PS and PS-KC labels was contributed to the decreased L value of PS label after incorporation of KC (from −0.14 ± 0.07 to −3.65 ± 0.12). PS-KC-BRE labels were higher in values of ΔE, a⁎, and b⁎ and lower in L⁎ values when compared to PS and PS-KC labels (p < 0.05), indicating PS-KC-BRE labels turned into dark, red and yellow colors. Incorporation of BRE could significantly alter the color of PS-KC label (p < 0.05). However, no significant effect was found with the increased addition amount of BRE (from 2 mL/g to 4 mL/g) probably due to higher concentrations of BRE used in PS-KC-BRE labels. As expected, ΔE of labels was markedly influenced by incorporation of BRE and its addition amounts (p < 0.05). Prietto et al. (2017) found that corn starch labels with red cabbage anthocyanins showed positive a⁎ and negative b⁎ values while the labels with black bean anthocyanins showed positive a⁎ and b⁎ values. Therefore, colors of anthocyanin-rich labels were associated with the content and composition of anthocyanins in pigment extracts.

Table 2.

Color photograph and color parameters of PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels.

| Films | Color | L⁎ | a⁎ | b⁎ | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS |  |

−0.14 ± 0.07a | −0.05 ± 0.06d | 0.57 ± 0.07b | 0.53 ± 0.03e |

| PS-KC |  |

−3.65 ± 0.12b | 0.24 ± 0.10d | 0.84 ± 0.04b | 3.75 ± 0.13 d |

| PS-KC-BRE-I |  |

−4.01 ± 0.07b | 3.11 ± 0.13c | 1.22 ± 0.08a | 5.31 ± 0.21c |

| PS-KC-BRE-II |  |

−5.11 ± 0.18c | 5.01 ± 0.29b | 0.39 ± 0.16b | 7.16 ± 0.33b |

| PS-KC-BRE-III |  |

−8.02 ± 0.18d | 7.50 ± 0.29a | −0.23 ± 0.11c | 10.98 ± 0.32a |

A white paper with L (89.98), a (−0.6) and b (−3.4) is used as control. Values are given as mean ± standard deviation. Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.2.2. Light transmittance

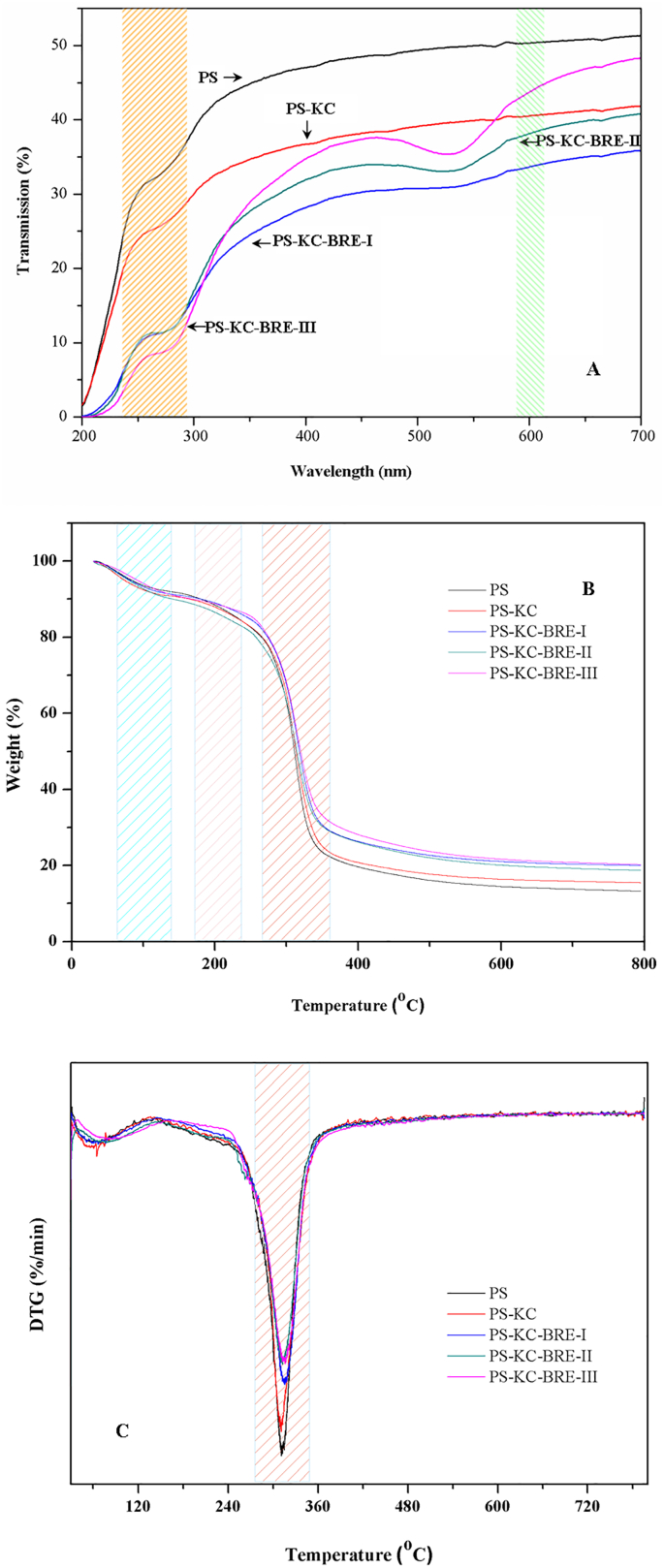

Light transmittance of labels is one of important indicators for assessing the quality of food packaging. Labels with high light transmittance may expose food to ultraviolet light, accelerate the oxidation and degradation of vitamins and result in nutrient destruction, color loss and toxic substance formation that pose a threat to human health (Wu, Yan, Zhang, Wu, Zhang, & Zhang, 2024). As a result, creating labels with the proper light transmittance is essential to guaranteeing the quality and safety of food. The light transmittance of PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels scanned at 200–700 nm is present in Fig. 2A. PS label showed a higher light transmittance than PS-KC-BRE labels in the wavelength range (200–400 nm) because of lacking the UV-light absorption groups (Zhang, Liu, et al., 2020). The incorporation of BRE or KC significantly reduced the light transmittance of PS label (Fig. 2A). The reason might be that KC dispersed in the labels scattered or blocked the light transmission of labels and the anthocyanins in BRE had strong absorption ability against UV radiation (Jiang, Liu, et al., 2023). The light transmission was significantly different between PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE-I labels in the wavelength range of 430–700 nm. And the PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III labels showed enhanced light transmission than PS-KC-BRE-I label in the visible wavelength range (Fig. 2A). The result demonstrated that the UV–vis light barrier property of PS label was markedly increased after addition with BRE or KC, which was helpful in protecting the packaged foods from visible and ultraviolet light, avoiding nutrient losses, discoloration and off-flavor of packaging foods.

Fig. 2.

UV–vis light transmittance (A), TGA (B) and DTG (C) curves of the PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels (PS: pea starch label; PS-KC: pea starch/κ-carrageenan label; PS-KC-BRE-I, PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III: pea starch/κ-carrageenan labels containing 2, 3 and 4 mL/g of black raspberry extraction (on pea starch basis), respectively).

3.2.3. Water vapor permeability (WVP)

The WVP values of PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels are given in Table 1. The WVP of the PS and PS-KC labels was (2.11 ± 0.2) and (2.48 ± 0.2) × 10−9 g m−1 s−1 Pa−1, respectively, indicating the label of PS-KC possessed a better water vapor barrier ability than PS (p < 0.05). No significant differences were found in WVP between the PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE-I label with a WVP of 2.57 ± 0.5 × 10−9 g m−1 s−1 Pa−1. However, the WVP of PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III labels was (1.96 ± 0.2) and (1.98 ± 0.1) × 10−9 g m−1 s−1 Pa−1, respectively, which was significantly lower than that of PS-KC label (p < 0.05). The decreased WVP of the PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III labels was resulted from strong intermolecular interactions formed between anthocyanins and PS/KC. Our findings suggested that BRE could significantly improve the water vapor barrier ability of PS-KC label. Similar results have been observed by Wang et al. (2019).

3.2.4. Mechanical property

The mechanical properties of materials, usually assessed as strength (TS) and elongation at break (EAB), are a kind of ability of withstanding external force and maintaining their integrity without rupturing. TS and EAB are the fundamental investigating parameters for a material to be employed for food packaging applications (Zhang et al., 2021). TS and EAB of the PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels are present in Table 1. TS and EAB of PS label were 33.43 ± 2.13 MPa and 6.26 ± 0.43 %; while TS and EAB of PS-KC label were 19.84 ± 1.35 MPa and 7.41 ± 0.21 %, respectively. Significant difference was found in EAB between PS-KC and PS labels. TS of PS-KC label wassignificantly lower than that of PS label. The decrease in TS for PS-KC label might be due to the aggregation of the KC destroyed the uniformity and compactness of the label network. The PS-KC-BRE-I label had significantly higher TS when compared with PS-KC label. The increased TS for PS-KC-BRE-I label was due to stronger interfacial adhesion between PS and BRE, which was resulted from strong hydrogen interactions of hydroxyl groups between anthocyanin and PS molecules. However, PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III labels had decreased TS than PS-KC-BRE-I label, attributed to that excessive BRE (3 and 4 mL/g) aggregated together, disrupting the compactness of PS-KC networks. In addition, PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III labels presented increased EAB as compared to PS and PS-KC labels (p < 0.05). The increase in EAB might be due to the fact that BRE caused the disordering of the starch matrix and resulted in an increase in EAB. This result agreed with the findings of Zhai et al. (2017) who found the mechanical properties of the starch/poly vinyl alcohol labels were enhanced after incorporation with roselle anthocyanins, due to the fact that anthocyanins enhanced the compatibility of the starch and poly vinyl alcohol molecules, making the labels more homogenous.

3.2.5. Thermal property

TGA was performed to analyze the thermal decomposition behavior of starch label. As present in Fig. 2B, the weight loss process of each label could be divided into three stages. The fist stage of weight loss (6.1–8.3 %) occurring approximately at 100–120 °C was mainly attributed to the evaporation of free water in the label, accompanied by the breakage of intermolecular and intramolecular hydrogen bonds (Yao et al., 2022). The second stage with a weight loss of 10.1–12.3 % was found at 200–230 °C, owning to the glycerol decomposition (Martins et al., 2012). The third stage was at 240–330 °C with a weight loss of 17.7–72.6 %, primarily due to the removal of polyhydroxyl groups from starches, as well as the disintegration and depolymerization of the label matrix (Yao et al., 2022). When the temperature was increased to 500 °C, the residual weight ratio for PS label was 16.1 %, while that for the PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels was 17.7–23.7 % (Fig. 2B). The result indicated the thermal stability of PS label was enhanced after incorporation with KC and BRE, which was resulted from the intermolecular interaction between PS, KC and BRE. The DTG curve, representing mass loss rate, was obtained by plotting the first derivative of mass loss with respect to temperature versus temperature. As shown in Fig. 2C, the PS-KC or PS-KC-BRE label showed relatively lower DTG than the PS label. The finding indicated incorporation of KC and BRE was able to alter the maximum weight loss rate of the PS label. Similar results were also obtained in the chitosan/purple-fleshed sweet extract label (Yong et al., 2019).

3.3. Functional properties of labels

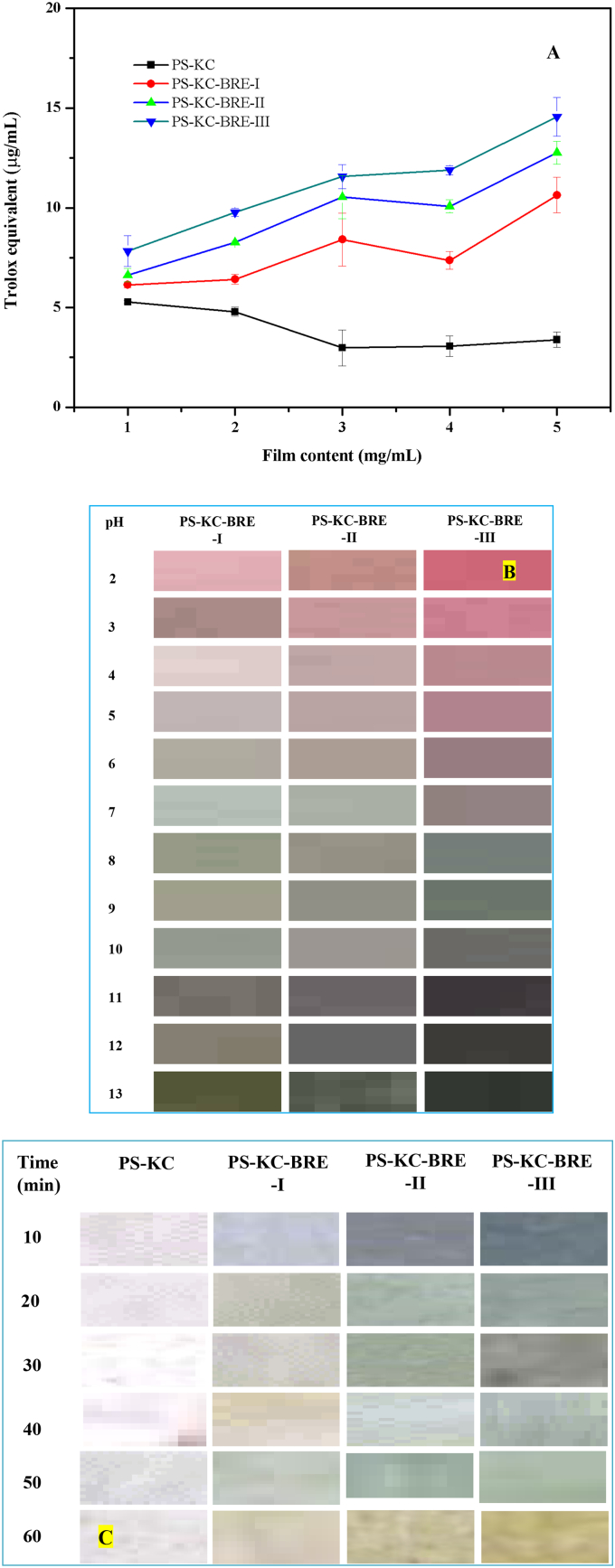

3.3.1. Antioxidant activity of labels

Free radicals, as one of the most reactive chemicals, have the great potential to oxidize different food ingredients and cause spoiling. Any material used in food packaging needs to inhibit protein and lipid from radical oxidation and extended storage period by scavenging free radicals. Therefore, antioxidant activity of labels is crucial for active food packaging. As a stable free radical, DPPH was widely used as a tool for testing the free radical-scavenging capacity of antioxidant labels (Kumar et al., 2024). Fig. 3A reports the DPPH scavenging activity of the PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels in units of Trolox equivalent (μg/mL). There were no significant differences in DPPH scavenging activity for PS-KC when the label concentration was increased. However, the scavenging activity of PS-KC-BRE labels was greatly enhanced with the increase of label concentration. The scavenging activity of the PS-KC-BRE labels was mostly resulted from the polyphenols released from label matrix, which could eliminate the DPPH radical through donating hydrogen atoms. The DPPH radical scavenging ability of PS-KC-BRE-I, PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III labels at 5 mg/mL of addition amount was 10.63 ± 0.89 μg/mL, 12.76 ± 0.58 μg/mL and 14.56 ± 0.97 μg/mL, respectively (Fig. 3A). The PS-KC-BRE-III label with the highest BRE addition amount had the largest DPPH radical scavenging ability, which was near 6 times compared with that of PS-KC label (3.39 ± 0.38 μg/mL). The result indicated that incorporation of BRE increased the antioxidant activity of the label and provided strong support for the application of PS-KC-BRE labels in safeguarding food qualities.

Fig. 3.

Antioxidant activity (A) and pH- and ammonia-sensitivities (B and C) of the PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels (PS-KC: pea starch/κ-carrageenan label; PS-KC-BRE-I, PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III: pea starch/κ-carrageenan labels containing 2, 3 and 4 mL/g of black raspberry extraction (on pea starch basis), respectively).

3.3.2. pH-sensitivity

The pH-sensitive packaging films present extensive potential applications in food packaging and freshness monitoring because the process of food spoilage is usually accompanied by a pH change. The pH-sensitivity of PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE films was evaluated by the pH differential method with different buffer solutions (pH 2–13). The PS-KC label was kept colorless and transparent as immersed in different pH buffers (data not shown). The colors of the PS-KC-BRE labels in different buffers are present in Fig. 3B. The results showed that the PS-KC-BRE-I label was pastel violet while the PS-KC-BRE-III label was red violet when the pH was 2. When pH altered from 3 to 7, the color of PS-KC-BRE labels was faded little by little and became olive green at pH 8 (Fig. 3B). With the increased addition amount of BRE, the olive green color of PS-KC-BRE label was deepened. As pH was changed from 9 to 12, the color became sea green (Fig. 3B). The results indicated that incorporation of BRE could significantly enhance pH-sensitivity of the PS-KC label, which coincided with the results of color pH-response of BRE (Fig. 1). The color change of the PS-KC-BRE labels was attributed to the structural transformation of anthocyanins with alteration of environment pH. Some similar results were reported previously for the pH-sensitive labels combined with anthocyanin-rich natural extracts (Kaewprachu et al., 2024).

3.3.3. Ammonia-sensitivity

Based on the pH-colorimetric properties of PS-KC-BRE labels, the intelligent labels showed greatly potential application in packaging protein-rich food. The volatile nitrogen compounds generated during meat spoilage were regarded as indicators to detect freshness level of meat. To simulate the sensitivity to volatile nitrogen compounds, the ammonia-sensitivity of the PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels was examined by placing these labels in an ammonia vapor environment. As depicted in Fig. 3C, the color of PS-KC label was unchanged with prolong of time exposed in ammonia gas. PS-KC-BRE-I, PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III labels showed different color that could be detected by naked eyes. As the time exposed to NH3 gas was prolonged, colors of the PS-KC-BRE labels were altered from red-blue to yellow-green. The color change of PS-KC-BRE labels might be attributed to differential protonation states of anthocyanins in different pH environments. Tavakoli et al. (2023) reported that ammonia vapor absorbed by the labels could produce an alkaline environment via reacting with water molecules, cause alterations in the structure of the anthocyanins and ultimately lead to colorimetric response. Zheng et al. (2023) observed a similar phenomenon in the starch/chitosan-based labels incorporated with anthocyanin-encapsulated amylopectin nanoparticles. In general, incorporation of BRE endowed the PS-KC-BRE labels a significant ammonia-sensitivity, supporting the potential usage of the PS-KC-BRE labels as a pH-sensitive indicator for detecting the freshness of protein-rich food.

3.4. Structural properties

3.4.1. SEM

There is a close association between the microstructure of label and its physical and functional performances. The cross-sectional images of PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels are shown in Fig. 4A. A rough cross-section was found in the PS label image with obvious separation of the starch-rich and glycerol-rich phases. Generally, high compatibility materials often have a homogeneous cross-section, while low compatibility materials have a textured cross-section with granular features. Our results clearly indicated that there was a certain degree of immiscibility between glycerol and starches. As Wu, Yan, Zhang, Wu, Luan, and Zhang (2024) noted, this immiscibility between glycerol and starch could be resulted from the contrasting densities of the two compounds. The PS-KC label presented a homogeneous cross-section profile, which indicated KC was evenly dispersed in PS label. The findings were attributed to the strong intermolecular interactions formed between PS and KC molecules. With incorporation of BRE, a notable difference was observed in microstructure between the PS-KC-BRE-I and PS-KC-BRE-II labels. Specifically, its cross-section image of PS-KC-BRE-II label was uniform and had no visible phase separation. This suggested that incorporation of appropriate level of BRE enhanced the compatibility of KC and PS, due to the H-bond formation between PS, KC and BRE. However, as the addition level of BRE was increased, the cross-section of PS-KC-BRE-II label became rougher, and some immiscibility were observed. The reason might be that the excessive BRE was clustered together and disrupt the integrity of the label network.

Fig. 4.

SEM (A), XRD (B) and FT-IR (C) of the PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels (PS: pea starch label; PS-KC: pea starch/κ-carrageenan label; PS-KC-BRE-I, PS-KC-BRE-II and PS-KC-BRE-III: pea starch/κ-carrageenan labels containing 2, 3 and 4 mL/g of black raspberry extraction (on pea starch basis), respectively).

3.4.2. XRD

X-ray diffraction is a powerful tool to reveal information about intermolecular interactions between different components of labels. The XRD spectra of PS, PS-KC and PS-KC-BRE labels are given in Fig. 4B. The X-ray diffraction patterns of PS label had characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ = 5.6°, 15.5° and 23.5° (Xie et al., 2024). No significant difference was found in the position and intensity between the PS and PS-KC labels, demonstrating that the addition of KC did not change the amorphous structure of PS-KC label. The PS-KC-RNE-I label exhibited similar XRD patterns with the PS-KC label, which was probably due to the low content of RNE in the PS-KC-RNE-I label. The PS-KC-RNE-II label showed significantly decreased intensities of diffraction peaks at 2θ = 15.5°, 17.1°, 19.5° and 22°, which was probably due to intermolecular H bonds newly formed between PS, KC and anthocyanins in BRE. Similarly, Qin et al. (2020) reported that the diffraction peak intensities of the cassava starch/polyvinyl alcohol label became lowered when the anthocyanin-rich Lycium ruthenicum extract was incorporated. Our results suggested the crystallinity nature of PS-KC-BRE labels was related to the content of anthocyanins added.

3.4.3. FT-IR

FT-IR spectra of PS, PS-KC, and PS-KC-BRE labels were analyzed to verify chemical interactions between polymers and BRE (Fig. 4C). the characteristic peaks at about 3330 cm−1 were assigned to O—H stretching vibration of the hydroxyl groups provided by water, starches, plant extracts in labels (Jiang, Zhang, et al., 2023). The peaks in the range of 1200 cm−1 to 1370 cm−1 were attributed to C—O stretching vibrations in starch (Ranjbar et al., 2023). The peaks found from 1647 to 1651 cm−1 were corresponded to the C O stretching vibrations. The peak at 1412 cm−1 was assigned to C-O-H stretching vibration of glycerol in labels (Abdillah et al., 2024). The band at 1230 cm−1 was formed by asymmetric stretching of the O=S=O in KC. The bands at 845 cm−1, 1030 cm−1 and 1410 cm−1 were attributed to the C—H bending vibration, C O and C—C tensile vibrations in anthocyanins, respectively (Zhang, Sun, et al., 2020). The band at 1025 cm−1 was assigned to C—O—C bond stretching, while the bands found at 929 cm−1, 857 cm−1, and 763 cm−1 were associated with the stretching vibration of the glucose ring (Dong et al., 2023). The PS-KC label had similar FT-IR patterns with PS-KC label, indicating the chemical structure of PS-KC label was unchanged and no covalent interactions occurred in labels with the addition of KC. With the addition of BRE, an obvious increase was observed in the intensity of peaks at 3330 cm−1 and 1006 cm−1. The increased intensity of peaks was related to the possible physical interactions formed between the hydroxyl groups of BRE and PS and KC. Similarly phenomenon was observed in the longan seed starch based labels, for which the intensity of the band at 1647 cm−1 and 1336 cm−1 was found to be improved after adding the anthocyanin-rich banana flower bract extracts (Jiang, Zhang, Cao and Jiang, 2023).

3.5. Application of labels in detecting pork spoilage

During the storage of pork, the decomposition of proteins and fats can generate some volatile nitrogen-containing compounds and leads to an increase in TVB-N values. Therefore, by determining the TVB-N value, the freshness of pork can be evaluated indirectly (Qin et al., 2021). Owning to the strong antioxidant activity and significant pH and ammonia sensitivities of PS-KC-BRE labels, they were further used to monitor the freshness changes in pork meat at 20 °C for 60 h. As presented in Table 3, the amount of TVB-N was continuously enhanced during the storage periods. In the first 36 h, the TVB-N of pork reached 15.17 ± 0.28 mg/100 g. According to GB 2707–2016 (China National Standard), 15 mg/100 g was the rejection limitation of TVB-N level for pork. Our results suggested pork used in the experiment was not fresh and could not consumed at a of storage time of 36 h. At 60 h, the TVB-N value of pork was found to be 40.67 ± 0.66 mg/100 g. The results indicated that the spoilage rate of pork was accelerated at the later stage of storage, attributed to the increased microbial growth rate and endogenous enzyme degradation rate of pork during storage, leading to the generation of large amounts of volatile base nitrogen (Zhang, Shu, & Liu, 2024). The color change of PS-KC-BRE labels is present in Table 3. The PS-KC-BRE labels showed no significant color change within the first 24 h of storage. However, after 36 h, the pink color of the labels was changed to brown one, making it easy to discern with naked eyes. Recently, Zhang, Shu, and Liu (2024) reported the konjac glucomannan labels incorporated with curcumin and alizarin showed great potential in fresh pork monitoring. Our result indicated PS-KC-BRE labels were suitable to indicate the freshness of pork. Among these PS-KC-BRE labels, the PS-KC-BRE-III label showed the most significant color change from pink to red and olive green due to its highest anthocyanin content. Our results indicated that anthocyanin-rich BRE could be incorporated into starch-based labels to monitor the freshness of pork.

Table 3.

Changes in the TVB-N level of pork meat and the color of labels with different storage times.

| Time (h) | TVB-N level (mg/100 g) | PS-KC | PS-KC-BRE-I | PS-KC-BRE-II | PS-KC-BRE-III |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 2.17 ± 0.59 e |  |

|

|

|

| 24 | 8.95 ± 0.42 d |  |

|

|

|

| 36 | 15.17 ± 0.28 c |  |

|

|

|

| 48 | 21.96 ± 0.34 b |  |

|

|

|

| 60 | 40.67 ± 0.66 a |  |

|

|

|

Values are given as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

4. Conclusion

Intelligent packaging has sparked interest due to their capacity to indicate food freshness. In this study, active and intelligent packaging labels were successfully fabricated by solution casting method using anthocyanin-rich black raspberry extract as pH indicator, and PS and KC as label-forming substrates. It was found black raspberry extract had a profound effect on the physical, structural and functional properties of the PS and PS-KC label. The incorporation of BRE could significantly enhance the thickness, thermal stability, EAB and pH sensitive properties, antioxidant activity of label, however, reduce the light transmittance and TS of PS label. Data on the antioxidant experiment in vitro demonstrated a significant potent DPPH free radical scavenging activity of PS-KC-BRE labels in dose-dependent manners. Structural characterization based on SEM, XRD and FT-IR confirmed some degree intermolecular interactions between BRE and PS/KC in PS-KC-BRE labels. Due to pH-sensitive and ammonia-sensitivity, PS-KC-BRE labels showed visible color alteration as the pork deteriorated. The PS-KC-BRE labels could be applied for intelligent packaging labels in the quality testing of high-protein foods. However, due to intelligent packaging is still in the experimental phase, extensive research is needed on the consumer acceptance and development of commercial production methods for intelligent labels in future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Changxing Jiang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Gang Liu: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Conceptualization. Qian Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation. Siyu Wang: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Yufei Zou: Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Science & Technology Special Project of North Jiangsu (SZ-HA2021037).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abdillah A.A., Lee R.-C., Charles A.L. Improving physicomechanical properties of arrowroot starch films incorporated with kappa-carrageenan: Sweet cherry coating application. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2024;277 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Wang C., Zou Y., Xu Y., Wang S., Jiang C., Liu T., Zhou X., Zhang Q., Li S. Colorimetric and antioxidant films based on biodegradable polymers and black nightshade (Solanum nigrum L.) extract for visually monitoring Cyclina sinensis freshness. Food Chemistry: X. 2023;18 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.100661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F., Gao W., Liu P., Kang X., Yu B., Cui B. Digestibility, structural and physicochemical properties of microcrystalline butyrylated pea starch with different degree of substitution. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2023;314:120927. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.120927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhadef K., Chaari M., Akermi S., Ben Hlima H., Ennouri M., Abdelkafi S.…Smaoui S. pH-sensitive films based on carboxymethyl cellulose/date pits anthocyanins: A convenient colorimetric indicator for beef meat freshness tracking. Food Bioscience. 2024;57 [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R.K., Rout S., Guha P., Srivastav P.P., Jadhav H.B. In: Intelligent packaging. Bangar S.P., Trif M., editors. 2024. Chapter 2 - intelligent versus another packaging; pp. 31–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jebel F.S., Roufegarinejad L., Alizadeh A., Amjadi S. Development and characterization of a double-layer smart packaging system consisting of polyvinyl alcohol electrospun nanofibers and gelatin film for fish fillet. Food Chemistry. 2025;462 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.140985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Liu T., Wang S., Zou Y., Cao J., Wang C., Hang C., Jin L. Antioxidant and ammonia-sensitive films based on starch, κ-carrageenan and Oxalis triangularis extract as visual indicator of beef meat spoilage. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023;235 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Yang H., Liu T., Zhang Q., Zou Y., Wang S. Fabrication, characterization and evaluation of Manihot esculenta starch based intelligent packaging films containing gum ghatti and black currant (Ribes nigrum) extract for freshness monitoring of beef meat. Food Chemistry: X. 2024;23 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Zhang W., Cao J., Jiang W. Development of biodegradable active films based on longan seed starch incorporated with banana flower bract anthocyanin extracts and applications in food freshness indication. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023;251 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaewprachu P., Romruen O., Jaisan C., Rawdkuen S., Klunklin W. Smart colorimetric sensing films based on carboxymethyl cellulose incorporated with a natural pH indicator. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2024;259 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.129156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan J., Liu J., Xu F., Yun D., Yong H., Liu J. Development of pork and shrimp freshness monitoring labels based on starch/polyvinyl alcohol matrices and anthocyanins from 14 plants: A comparative study. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;124 [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H., Deshmukh R.K., Gaikwad K.K., Negi Y.S. Physicochemical characterization of antioxidant film based on ternary blend of chitosan and Tulsi-Ajwain essential oil for preserving walnut. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2024;134880 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang T., Wang H., Shu Y., Khan S., Li C., Zhang Z. An intelligent film based on self-assembly of funoran and Ophiopogon japonicus seed anthocyanins and its application in monitoring protein rich food freshness. Food Control. 2024;159 [Google Scholar]

- Luo D., Fan J., Jin M., Zhang X., Wang J., Rao H., Xue W. The influence mechanism of pH and polyphenol structures on the formation, structure, and digestibility of pea starch-polyphenol complexes via high-pressure homogenization. Food Research International. 2024;114913 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins J.T., Cerqueira M.A., Bourbon A.I., Pinheiro A.C., Souza B.W., Vicente A.A. Synergistic effects between κ-carrageenan and locust bean gum on physicochemical properties of edible films made thereof. Food Hydrocolloids. 2012;29:280–289. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller E., Hoffmann T.G., Schmitz F.R.W., Helm C.V., Roy S., Bertoli S.L., de Souza C.K. Development of ternary polymeric films based on cassava starch, pea flour and green banana flour for food packaging. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2024;256 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasagoudr S.S., Masti S.P., Hegde V.G., Chougale R.B. Cetrimide crosslinked chitosan/guar gum/gum ghatti active biobased films for food packaging applications. Journal of Polymers and the Environment. 2023;31:579–594. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira G.F., Meneghetti B.B., Soares I.H.B.T., Soares C.T., Bevilaqua G., Fakhouri F.M., de Oliveira R.A. Multipurpose arrowroot starch films with anthocyanin-rich grape pomace extract: Color migration for food simulants and monitoring the freshness of fish meat. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2024;265 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prietto L., Mirapalhete T.C., Pinto V.Z., Hoffmann J.F., Vanier N.L., Lim L.-T.…da Rosa Zavareze E. pH-sensitive films containing anthocyanins extracted from black bean seed coat and red cabbage. Lwt. 2017;80:492–500. [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y., Xu F., Yuan L., Hu H., Yao X., Liu J. Comparison of the physical and functional properties of starch/polyvinyl alcohol films containing anthocyanins and/or betacyanins. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;163:898–909. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y., Yun D., Xu F., Chen D., Kan J., Liu J. Smart packaging films based on starch/polyvinyl alcohol and Lycium ruthenicum anthocyanins-loaded nano-complexes: Functionality, stability and application. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;119 [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbar M., Azizi Tabrizzad M.H., Asadi G., Ahari H. Investigating the microbial properties of sodium alginate/chitosan edible film containing red beetroot anthocyanin extract for smart packaging in chicken fillet as a pH indicator. Heliyon. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavakoli S., Mubango E., Tian L., Bohoussou ŃDri Y., Tan Y., Hong H., Luo Y. Novel intelligent films containing anthocyanin and phycocyanin for nondestructively tracing fish spoilage. Food Chemistry. 2023;402 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Yong H., Gao L., Li L., Jin M., Liu J. Preparation and characterization of antioxidant and pH-sensitive films based on chitosan and black soybean seed coat extract. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;89:56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Yan X., Zhang J., Wu X., Luan M., Zhang Q. Preparation and characterization of pH-sensitive intelligent packaging films based on cassava starch/polyvinyl alcohol matrices containing Aronia melanocarpa anthocyanins. LWT. 2024;194 [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Yan X., Zhang J., Wu X., Zhang Q., Zhang B. Intelligent films based on dual-modified starch and microencapsulated Aronia melanocarpa anthocyanins: Functionality, stability and application. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2024;275 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao T., Guo Z., Bi X., Zhao Y. Polyphenolic profile as well as anti-oxidant and anti-diabetes effects of extracts from freeze-dried black raspberries. Journal of Functional Foods. 2017;31:179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Xie S., Li Z., Duan Q., Huang W., Huang W., Deng Y.…Xie F. Reducing oil absorption in pea starch through two-step annealing with varying temperatures. Food Hydrocolloids. 2024;150:109701. [Google Scholar]

- Yao X., Yun D., Xu F., Chen D., Liu J. Development of shrimp freshness indicating films by immobilizing red pitaya betacyanins and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in polysaccharide-based double-layer matrix. Food Packaging and Shelf Life. 2022;33 [Google Scholar]

- Yong H.M., Wang X.C., Bai R.Y., Miao Z.Q., Zhang X., Liu J. Development of antioxidant and intelligent pH-sensing packaging films by incorporating purple-fleshed sweet potato extract into chitosan matrix. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;90:216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai X., Shi J., Zou X., Wang S., Jiang C., Zhang J., Huang X., Zhang W., Holmes M. Novel colorimetric films based on starch/polyvinyl alcohol incorporated with roselle anthocyanins for fish freshness monitoring. Food Hydrocolloids. 2017;69:308–317. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Sun G., Cao L., Wang L. Accurately intelligent film made from sodium carboxymethyl starch/κ-carrageenan reinforced by mulberry anthocyanins as an indicator. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;108 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Shu Q., Liu Y. The use of novel colorimetric films to monitor the freshness of pork, utilizing konjac glucomannan with curcumin/alizarin. Journal of Food Protection. 2024;87 doi: 10.1016/j.jfp.2024.100339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Huang T.-S., Yan H., Hu X., Ren T. Novel pH-sensitive films based on starch/polyvinyl alcohol and food anthocyanins as a visual indicator of shrimp deterioration. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;145:768–776. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.12.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Zhang M., Zhao Z., Zhu J., Wan X., Lv Y., Tang C., Xu B. Preparation and characterization of intelligent and active bi-layer film based on carrageenan/pectin for monitoring freshness of salmon. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2024;276 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Zhang Y., Cao J., Jiang W. Improving the performance of edible food packaging films by using nanocellulose as an additive. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2021;166:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Liu J., Yong H., Qin Y., Liu J., Jin C. Development of antioxidant and antimicrobial packaging films based on chitosan and mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) rind powder. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;145:1129–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Liu L., Yu J., Farag M.A., Shao P. Intelligent starch/chitosan-based film incorporated by anthocyanin-encapsulated amylopectin nanoparticles with high stability for food freshness monitoring. Food Control. 2023;151 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Cheng R., Wang B., Zeng J., Xu J., Li J., Kang L., Cheng Z., Gao W., Chen K. Biodegradable sandwich-architectured films derived from pea starch and polylactic acid with enhanced shelf-life for fruit preservation. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2021;251 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.