Abstract

After a primary infection, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) establishes lifelong latency in myeloid lineage cells, and the virus has developed several mechanisms to avoid immune recognition and destruction of infected cells. In this study, we show that HCMV utilizes two different strategies to reduce the constitutive expression of HLA-DR, -DP, and -DQ on infected macrophages and that infected macrophages are unable to stimulate a specific CD4+ T-cell response. Downregulation of the HLA class II molecules was observed in 90% of the donor samples and occurred in two phases: at an early (1 day postinfection [dpi]) time point postinfection and at a late (4 dpi) time point postinfection. The early inhibition of HLA class II expression and antigen presentation was not dependent on active virus replication, since UV-inactivated virus induced downregulation of HLA-DR and inhibition of T-cell proliferation at 1 dpi. In contrast, the late effect required virus replication and was dependent on the expression of the HCMV unique short (US) genes US1 to -9 or US11 in 77% of the samples. HCMV-treated macrophages were completely devoid of T-cell stimulation capacity at 1 and 4 dpi. However, while downregulation of HLA class II expression was rather mild, a 66 to 90% reduction in proliferative T-cell response was observed. This discrepancy was due to undefined soluble factors produced in HCMV-infected cell cultures, which did not include interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor β1. These results suggest that HCMV reduces expression of HLA class II molecules on HCMV-infected macrophages and inhibits T-cell proliferation by different distinct pathways.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is a widespread infectious agent that is carried by 70 to 100% of healthy adults (1, 8). While HCMV infections generally are subclinical in immunocompetent hosts, the virus can cause severe morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients, such as transplant patients and AIDS patients. After a primary infection, HCMV establishes lifelong latency in myeloid lineage cells (31). The virus has developed several immune evasion strategies to coexist with its host, including escape from recognition by CD4+ (17, 33) and CD8+ (2, 11–12, 34, 36) T cells as well as NK cells (4, 7, 10, 24, 32). A number of previous studies have demonstrated that the cellular immune response plays an important role in the control of a primary infection, in reactivation of latent HCMV, and in the development of HCMV disease in immunocompromised patients (23, 25, 26).

Although CD8+ T cells have been shown to be important in the control of disease in immunocompromised patients, CD4+ T cells play a key role in the early activation of CD8+ T cells as well as B-cell development. Thus, immune evasion strategies affecting HLA class II expression and antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells would be of utmost importance for the virus to avoid early immune recognition. HCMV immediate-early (IE) antigen-specific CD4+ T cells produce cytokines that inhibit HCMV replication in U373 MG cells (5), and CD4+ T cells can control and clear murine CMV (MCMV) infection in mice (15, 18). Previous studies have demonstrated both upregulation and downregulation of HLA class II expression on HCMV-infected endothelial cells (16, 29) and epithelial cells (21). Increased HLA class II expression is mainly believed to be mediated indirectly by cytokines produced during an inflammatory response (27). In contrast, downregulation of HLA class II molecules would instead be mediated by HCMV gene products similar to HCMV's effect on HLA class I expression by the unique short (US) genes US2, US3, US6, and US11 (2, 13–14, 36). In support of this hypothesis, a recent study demonstrated that stably HLA-DR-transfected U373 cells downregulate HLA-DR upon transfection of the HCMV US2 gene, which also resulted in an inhibition of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production by a CD4+ T-cell clone (33). While HLA class II molecules are constitutively expressed on professional antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, monocytes/macrophages, B cells, epithelial cells in the thymus, and Langerhans cells in the skin, IFN-γ can induce expression of HLA class II molecules on endothelial cells and fibroblasts (3). IFN-γ-induced HLA class II molecule expression on endothelial cells has also been shown to be blocked during HCMV infection, possibly through interference with the JAK/STAT pathway and prevention of the function of the class II transactivator (CIITA) (17, 19). However, the HCMV gene that mediates this transcriptional effect on HLA class II expression is still unknown. Furthermore, in a paper by Fish et al. (6), there was an indication that the expression of the constitutive HLA-DR expression on HCMV-infected macrophages was decreased. However, since HCMV's impact on HLA class II molecule expression and T-cell proliferation has been examined only with experimental cell systems, these findings may not reflect the in vivo response to HCMV-infected cells. Thus, mimicking the in vivo response will give us an insight into the effects of HCMV infection on T-cell activation, which include different strategies to affect HLA class II expression and cytokine-mediated effects on T-cell proliferation in individual donors.

In this study, we examined the ability of HCMV to affect the constitutive expression of HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP on macrophages from different donors and the viral effect on a specific CD4+ T-cell response. We demonstrate that HCMV infection leads to reduced expression of HLA-DR, -DP, and -DQ on infected macrophages from 90% of the donors. HCMV utilized different mechanisms to decrease the expression of HLA class II molecules on infected macrophages at 1 (independent of virus replication) and 4 (dependent on virus replication) days postinfection (dpi). Furthermore, HCMV-infected macrophages exhibited a 66 to 90% reduced capacity to stimulate an antigen-specific proliferative CD4+ T-cell response, which was dependent on undefined cytokines not involving interleukin-10 (IL-10) or transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Establishment of macrophage cultures.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 65 healthy donors were isolated as previously described (30) to examine HCMV's effect on HLA class II expression. The cells were plated onto petri dishes (Primaria; Falcon, Becton Dickinson) at a cell concentration of 10× 106 to18 × 106 cells/ml in Iscove's modified medium mixed with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.), and 10% AB serum and incubated at 37°C overnight. The following day, the nonadherent cells were removed, the cultures were extensively washed, and the monocyte-enriched cells were stimulated by addition of a 24-h allo-supernatant. The allo-supernatant was prepared as follows. PBMCs from different donors were mixed and incubated for 24 h in Iscove's complete medium. Thereafter, the supernatant was collected, cleared by centrifugation, and used to stimulate single monocyte cultures. At 2 to 3 days poststimulation, the cultures were washed with Iscove's medium and thereafter cultured in 60% AIM-V medium (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.), 30% Iscove's modified medium, and 10% AB serum, with the addition of l-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin (complete 60/30 medium). The medium was changed to fresh complete 60/30 medium every 3 to 4 days.

HCMV infection of macrophage cultures.

At day 7 poststimulation, the macrophage cultures were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and challenged with the HCMV AD169 strain at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 to 5 (generally an MOI of 3 to 5), for 4 h at 37°C. CMV strains were used for infection of macrophages: AD169 and the mutant HCMV strain RV670 (AD169 deletion mutant; deletion of US1 to -9 and US11, kindly provided by Thomas Jones, Infectious Diseases Section, Pearl River, N.Y.). Experiments were also performed with UV-irradiated or intravenous gamma globulin (IVIG; Immuno AG, Vienna, Austria)-neutralized AD169. The efficiency of the UV irradiation of virus and the IVIG treatment to prevent virus replication or fusion, was tested on human lung fibroblasts (HL cells) and resulted in a >99% inhibition of viral infectivity. Cell-free virus stocks were prepared from supernatants of infected HL cells, frozen and stored until use at −70°C. Virus titers were determined by plaque assays as previously described (35).

Immunocytochemistry.

Uninfected, HCMV (AD169)-infected, and RV670 (US1 to -9 and US11 deletion mutant of AD169)-infected macrophages were collected for immunocytochemical analysis at 4 and 7 dpi. The cells were washed with PBS and fixed with ice-cold 1:1 methanol-acetone for 10 min at room temperature. To decrease nonspecific binding, the macrophage cultures were treated with a blocking solution (Protein Block, serum free; Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Thereafter, the macrophage cultures were incubated at 4°C overnight with a rabbit polyclonal antiserum against HCMV IE protein and glycoprotein B (mouse anti-gB; gpUL55, kindly provided by William Britt, University of Alabama, Birmingham). Binding of primary antibodies was detected with one of the following secondary antibodies: fluorescein isothiocyanate tetramethyl (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse (GAM-FITC; Dakopatts) and phycoerythrin-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (DAR-RPE; Dakopatts). Stained cells were washed with PBS and mounted with a slow fade kit (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.) to reduce fluorescence fading. The number of HCMV-positive cells was quantified with an inverted fluorescence microscope.

Detection of HCMV replication in allo-stimulated macrophages.

RNA from uninfected and HCMV-infected macrophages at 4 or 7 dpi was prepared by lysing cells with Trizol (Gibco BRL), and thereafter RNA was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized with a first-strand cDNA kit (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HCMV-specific primer pairs for the major IE (MIE) and pp150 genes were used in the nested reverse transcription (RT)-PCR as previously described (30). As a positive control for the detection of DNA or RNA, primers specific for the glucose-6-phosphatase dehydrogenase (G6PD) gene were used for each sample. DNA and cDNA samples from uninfected and HCMV-infected HL cells were included as positive and negative controls. The PCR products were visualized on 2% agarose gels.

Flow cytometric analysis of macrophages.

A fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS; FACSort; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) was used to analyze uninfected and HCMV-infected macrophages for the expression of HLA class II molecules. The adherent macrophages were harvested by preincubation of cells in EDTA (Versene; Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) at 4°C for 30 min followed by scraping. The cells were stained with antibodies recognizing the different HLA class II molecules, HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP (all from Becton Dickinson), the cell surface markers CD14 (Dakopatts), or isotype controls (immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1] and IgG2a; Dakopatts) followed by appropriate secondary antibodies. The CD14+ cells were gated and analyzed for the expression of HLA class II molecules. The expression of HLA class II molecules on uninfected and HCMV-infected macrophages was measured as the mean channel fluorescence value following treatment with the respective antibody compared to that of the isotype control. In addition, unstimulated and phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated PBMCs were examined for the expression of CD69 and CD45RO (Becton Dickinson) at 3 days poststimulation. The difference in the histogram mean channel values for uninfected and HCMV-infected cells was calculated on a linear scale, and a more than 10-channel difference between uninfected and HCMV-infected cells was considered to be a positive or negative change, based on variations among controls.

Generation of CD4+ tetanus-specific T-cell clones.

PBMCs from tetanus-immunized blood donors were isolated as described above and washed twice in PBS with 4 mM EDTA and once in RPMI medium (Gibco BRL). The PBMCs were resuspended at a cell concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml (Gibco BRL), and 25 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (termed CTL medium) and plated in 24-well plates (1 ml/well). To each well, 1 ml of CTL medium containing 50 μl of tetanus toxoid (final concentration of tetanus toxoid, 1/40) was added. The cells were harvested after 7 days in culture, and the CD8+ cells were depleted with magnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). The CD4+ T cells were cloned by limiting dilution, by seeding 0.5 T cell/well with irradiated autologous PBMCs (7.5 × 104/well), irradiated autologous Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B cells (1 × 104/well; termed LCL), tetanus toxoid (1/40) (3 mg/ml; Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark), and IL-2 (40 U/ml) (recombinant human-IL-2; Novakemi AB, Enskede, Sweden). Positive clones were harvested after 13 days in culture and transferred to 48-well plates with fresh irradiated PBMCs, LCL, and tetanus toxoid at a final volume of 1 ml. IL-2 was added at days 2 and 4 after stimulation with tetanus toxoid. The clones were thereafter transferred to 24-well plates and restimulated as described above. The T-cell clones were harvested after 9 days in culture and tested for specificity against tetanus toxoid. The CD4+ T-cell clones were washed twice in RPMI medium, and the T cells (1 × 105) and irradiated autologous PBMCs (2 × 105 cells) were plated in triplicate in 96-well plates at a final volume of 200 μl of CTL medium. Triplicates with or without tetanus toxoid (negative control) were incubated for 78 h and thereafter pulsed with 1 μCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) for 18 h. The cells were harvested onto filters with a plate harvester (Harvester 996; Tomtec, Hamden, Conn.) according to the manufacturer's instructions and counted in an automated counter (1450 MicroBeta Trilux; WALLAC, Upplands Vasby, Sweden), and the results were expressed as cpm. Tetanus toxoid-specific CD4+ T-cell clones were cryopreserved in RPMI with 20% AB serum and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide.

The tetanus toxoid-specific T-cell clones were restimulated with anti-CD3 antibodies as follows. Cloned T cells (1 × 105) were incubated with irradiated PBMCs (25 × 106), LCL (5 × 105 cells), and OKT3 (30 ng/ml) in 25 ml of CTL medium. IL-2 was added at day 1 poststimulation, and at 4 days poststimulation, the cells were harvested, washed once with RPMI, and resuspended in 25 ml of fresh CTL medium containing IL-2 (40 U/ml). Fifty percent of the medium was replaced with fresh medium at days 7 and 10 poststimulation. The T-cell clones were used in proliferation assays at days 12 to 16 after this stimulation procedure.

The CD4+ T-cell proliferation assay.

Monocytes were isolated, plated onto 96-well plates (Primaria), and stimulated as described above. After 7 days in culture, the macrophages were mock infected or infected with HCMV for 4 h and, thereafter, washed and cultured in complete 60/30 medium overnight. The CD4+ T-cell clones were added to the wells of washed macrophages in triplicates in fresh CTL medium at 1 or 4 dpi, respectively, and incubated for 96 h. The cultures were pulsed with 1 μCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine and harvested as described above. Data were analyzed as means of the triplicates and calculated as the neat count increase in cpm values for the experiment − control cpm.

Measurement of IL-10 and TGF-β1 in cell culture supernatants.

Supernatants from uninfected, HCMV-infected, and UV-inactivate HCMV (UV-HCMV)-infected macrophages were collected and cleared by centrifugation at 4 and 7 dpi. The concentrations of IL-10 and TGF-β1 in the supernatants from the respective cultures were measured by using the Quantikine human IL-10 colorimetric sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or the Quantikine human TGF-β1 colorimetric sandwich ELISA (both from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

PHA stimulation of PBMCs.

Supernatants from uninfected and HCMV macrophages (4 dpi) were collected and cleared by centrifugation. PBMCs from different donors were stimulated with PHA (9 μg/well) and incubated with supernatants from either uninfected or HCMV-infected macrophages, diluted 1/10 in RPMI with 10% FCS. As a positive control, PBMCs were incubated with PHA and RPMI medium with 10% FCS. The cultures were pulsed with 1 μCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine at 2 days poststimulation and harvested as described above. Data were analyzed as means of triplicate determinations and calculated as the neat count increase in cpm for the experiment − control cpm.

PBMCs (105 cells/ml) were also incubated with supernatants from either uninfected or HCMV-infected macrophage cultures in the presence of antibodies directed against either the human IL-10 receptor (IL-10R) (30, 60, and 100 μg/ml) or the human TGF-βII receptor (TGF-βIIR) (50, 100, and 200 μg/ml) under saturating concentrations according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems).

RESULTS

HCMV reduces the constitutive expression of HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP on infected macrophages in a majority of the donor samples.

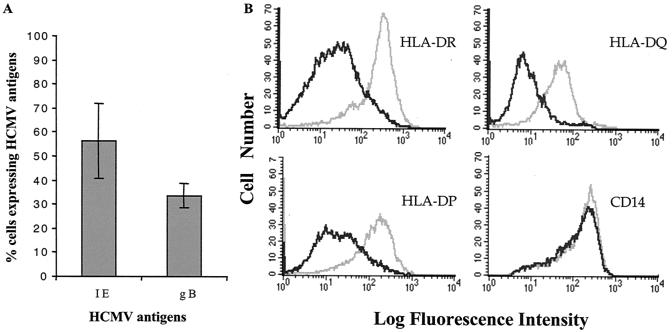

Previous studies that have examined the effect of HCMV on the expression of HLA class II molecules have demonstrated inhibition of the inducible HLA-DR expression on infected cells (19, 28). In addition, decreased expression of HLA-DR has been demonstrated in HLA-DR U373 cells stably transfected with the viral gene US2 (33). In this study, we examined whether HCMV affects the constitutive expression of the different HLA class II molecules DR, DQ, and DP on macrophages from different donors. HCMV replication in macrophages was assessed by an RT-PCR assay, which detected HCMV IE and pp150 RNA at 4 and 7 dpi (data not shown), HCMV (AD169)-infected macrophages expressed IE (56% ± 15%) and glycoprotein B (33% ± 5%) antigens as detected by immunofluorescence (Fig. 1A). The AD169 deletion mutant RV670, lacking the genes US1 to -9 and US11, which are involved in downregulation of HLA class I and class II molecules, infected macrophages to the same levels (8% ± 6% increased difference) compared to those of the wild-type virus (data not shown). HCMV reduced the expression of HLA class II molecules on infected macrophages from 42 of 48 (90%) of donors tested. A representative example of a FACS analysis of the differential expression of HLA class II molecules on infected macrophages is shown in Fig. 1B. While HCMV did not affect the expression of the macrophage marker CD14 (Fig. 1B), the reduced expression of HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP was donor specific in individual experiments. A summary of the results of all experiments is shown in Table 1, which shows that increased expression of the different HLA class II molecules was also sometimes observed on HCMV-infected cells. In macrophages from five of five experiments, a reduction in the expression of at least one of the HLA class II molecules DR, DQ, and DP was observed at 1 dpi, and the effect on the individual antigens was consistent throughout the 7-day testing period (data not shown). However, the results from repeated experiments did not consistently demonstrate an effect on the individual antigens in the same donors.

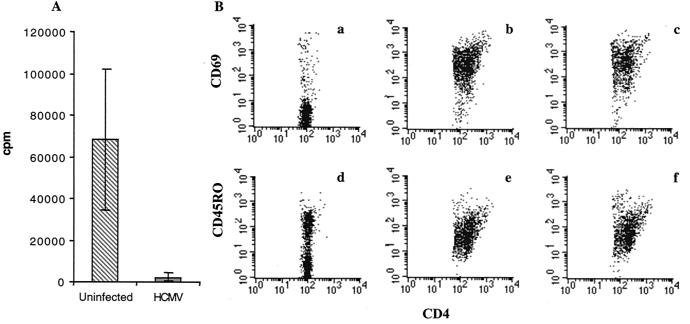

FIG. 1.

Expression of HCMV antigens, CD14, and HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP in HCMV-infected macrophages. (A) HCMV-infected macrophages were fixed at 7 dpi and stained for the IE and glycoprotein B (gB) antigens. The figure shows the mean percentage (± standard error) of HCMV-infected macrophages at 7 dpi (n = 6). (B) Flow cytometric analysis was performed with uninfected (gray line) and HCMV-infected (black line) macrophages by using antibodies directed against HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP and CD14. The figure shows a representative example of an analysis of HCMV's effect on the expression of HLA class II molecules and CD14 on macrophages from one donor at 4 dpi.

TABLE 1.

HCMV-induced downregulation of HLA class II molecules DR, DQ, and DP

| Molecule | No. of donor samples with expressiona

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced | Increased | Not affected | |

| HLA-DR | 9 (−41 ± 31) | ||

| HLA-DQ | 6 (−32 ± 22) | ||

| HLA-DP | 4 (−18 ± 3) | ||

| HLA-DR, -DP | 4 (−28 ± 6; −55 ± 37) | 1 | |

| HLA-DR, -DQ | 6 (−40 ± 30; −24 ± 10) | ||

| HLA-DP, -DQ | 6 (−35 ± 21; −38 ± 28) | ||

| HLA-DR, -DQ, -DP | 7 (−38 ± 18; −35 ± 21, −41 ± 25) | 5 (33 ± 14, 41 ± 27, 55 ± 29) | 0 |

| Totalb | |||

| HLA-DR | 26 (−36 ± 26) | 17 (29 ± 15) | 5 (1 ± 7) |

| HLA-DP | 21 (−38 ± 27) | 15 (46 ± 24) | 12 (−1 ± 3) |

| HLA-DQ | 25 (−32 ± 19) | 16 (32 ± 18) | 7 (1 ± 6) |

Values in parentheses are mean channels ± standard errors.

HLA-DR total includes HLA-DR alone and together with HLA-DP and/or -DQ. HLA-DP total includes HLA-DP alone and together with HLA-DR and/or -DQ. HLA-DQ total includes HLA-DQ alone and together with HLA-DR and/or -DP.

To examine whether the donor-specific downregulation of the different HLA class II molecules DR, DQ, and DP in individual experiments was associated with certain HLA class II phenotypes, 33 donors were typed for HLA-DR, and 24 donors were also typed for HLA-DP and HLA-DQ by the PCR-sequence-specific primer (SSP) method. HCMV's inhibitory effect on the respective HLA class II antigens was correlated with the donor's HLA class II phenotype. The HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP typing did not reveal any significant association between a particular DR, DQ, or DP phenotype and susceptibility to HCMV-induced decrease in HLA class II surface expression (data not shown).

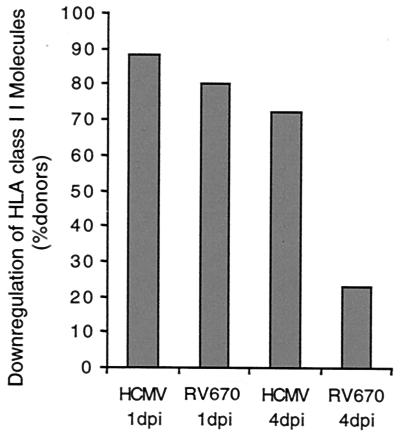

HCMV utilizes at least two different mechanisms for downregulation of HLA class II molecules at 1 and 4 dpi.

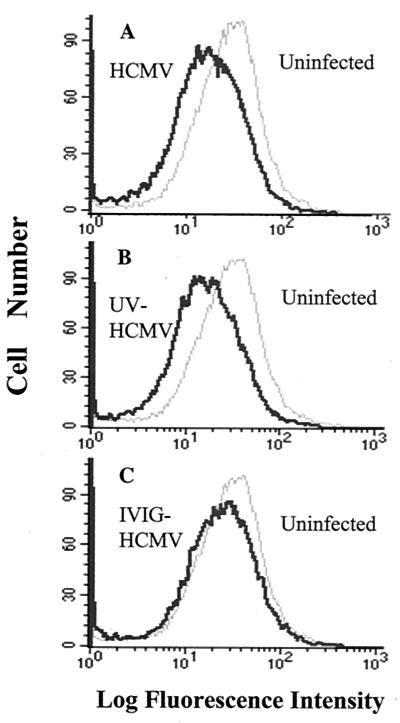

The kinetic analysis suggested that HCMV already induces a decrease in HLA class II expression at 1 dpi. Therefore, we examined the effects on HLA class II expression on infected macrophages from 17 donors at both 1 and 4 dpi. HCMV (AD169) infection resulted in decreased expression of HLA-DR in 12 of 17 (71%), HLA-DQ in 10 of 17 (59%), and HLA-DP in 7 of 17 (41%) of the donor samples at 1 dpi. Furthermore, the mutant HCMV AD169 strain RV670, which lacks the US1 to -9 and US11 genes, was also able to downregulate the expression of the different HLA class II molecules at 1 dpi (Fig. 2). In summary, decreased expression of any of the HLA class II molecules DR, DQ, and DP was observed in 15 of 17 (88%) of the donors at 1 dpi. In 12 of these 15 donors (80%), an effect on the expression of HLA class II molecules was also demonstrated when cells were infected with the mutant HCMV strain RV670 (Fig. 2). Interestingly, while treatment of cells with UV-irradiated and nonreplicative HCMV resulted in a relatively mild decreased expression of HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP on macrophages from three of four of the donors tested (−33 ± 19 mean channel decrease), IVIG treatment of virus did not affect the expression of HLA class II molecules at 1 dpi (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Importance of the HCMV US1 to -9 and US11 genes for downregulation of HLA class II molecules at 4 dpi, but not at 1 dpi. Macrophages were infected with HCMV AD169 or the HCMV AD169 mutant strain RV670, which lacks the genes US1 to -9 and US11 (n = 17). At 1 dpi, HCMV infection or HCMV RV670 infection resulted in decreased expression of HLA-DR, -DQ, or -DP in 88 and 80% of the samples, respectively. A decreased expression of HLA class II molecules was observed in 72% of the donors at 4 dpi. In 77% of these samples, RV670 did not affect the expression of HLA class II molecules.

FIG. 3.

Importance of viral replication for downregulation of HLA class II surface expression at 1 dpi. Flow cytometric analysis of HLA-DR expression was performed at 1 dpi on uninfected and HCMV-, UV-HCMV-, and HCMV-IVIG-infected macrophages. The reduced expression of HLA-DR on HCMV AD169-infected macrophages (A) was similar to the reduced expression induced by UV-irradiated HCMV (B). However, an effect on the HLA-DR expression was not detected on macrophages infected with IVIG-neutralized HCMV (C).

At 4 dpi, HCMV-infected macrophages expressed significant less HLA-DR in 8 of 17 (47%), HLA-DQ in 10 of 17 (59%), and HLA-DP in 10 of 17 (59%) of the donors tested. While downregulation of either of the HLA class II molecules was observed in macrophages from 13 of 18 (72%) of the donors at 4 dpi, the mutant HCMV strain RV670 decreased the expression of any of the HLA class II molecules in 3 of these 13 donors (23%) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, UV-irradiated nonreplicative virus did not inhibit the expression of HLA class II molecules at 4 dpi (data not shown). Thus, in macrophages from 77% of the donors, active virus replication and the presence of US1 to -9 or US11 genes were required for the HLA class II inhibition at 4 dpi. However, in 23% of the cases, another gene(s) or mechanism was responsible for the reduced expression of HLA class II molecules at this time point. These observations suggest that at least two distinct mechanisms are responsible for the modulation of HLA class II expression at early and late times after infection.

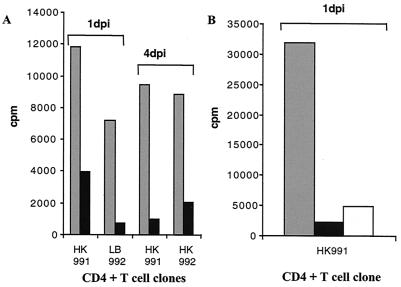

HCMV-infected macrophages cannot elicit a proliferative T-cell response.

To test the biological relevance of downregulation of HLA class II molecules on infected macrophages, tetanus toxoid-specific CD4+ T-cell clones were generated, and uninfected and HCMV-infected macrophages were tested for their ability to present tetanus toxoid peptides to the T-cell clones. Tetanus toxoid-specific CD4+ T-cell clones from two different individuals were added to mock-infected or HCMV-infected macrophages at 1 and 4 dpi. Figure 4A demonstrates that the T-cell proliferative response to tetanus toxoid antigens presented by HCMV-infected macrophages was reduced by 66 to 90% (n = 7) at 1 dpi and by 76 to 89% (n = 5) at 4 dpi compared to the level in uninfected macrophages. Interestingly, treatment of macrophages with UV-irradiated HCMV also resulted in a reduced capacity to present tetanus toxoid peptides to CD4+ T cells (72 to 86%, n = 3) at 1 dpi (Fig. 4B). These experiments show that HCMV-infected cells are able to evade immune recognition by CD4+ T cells.

FIG. 4.

Decreased CD4+ T-cell proliferation in HCMV-infected macrophage cultures. Uninfected (gray) and HCMV-infected (black) macrophages were tested at 1 and 4 dpi for their ability to present tetanus peptides to specific CD4+ T-cell clones. Panels A and B show representative examples of the experiments. (A) The proliferative T-cell response was reduced by 66 to 90% at 1 dpi and by 76 to 89% at 4 dpi in HCMV-infected macrophage cultures. (B) Macrophages were infected with UV-treated HCMV (white) and tested for their ability to present tetanus toxoid peptides to CD4+ T-cell clones. The proliferative T-cell response was reduced by 72 to 86% by UV-treated HCMV at 1 dpi. Thus, UV treatment of HCMV also results in inhibition of CD4+ T-cell proliferation.

Soluble factors produced by HCMV-infected cells suppress CD4+ T-cell proliferation.

A discrepancy was observed between the viral effect on HLA class II expression and the inhibition of T-cell proliferation, in particular for UV-inactivated virus. To further examine whether blocking of antigen presentation was mediated by a soluble factor or factors produced by HCMV-infected macrophages, PBMCs from different donors were incubated with supernatants from uninfected or HCMV-infected macrophages and stimulated with PHA. PBMCs incubated with PHA in the presence of fresh medium or medium containing supernatants from uninfected macrophage cultures induced a strong T-cell response (Fig. 5A). In contrast, cellular proliferation was inhibited by 97% when PBMCs were incubated with PHA in the presence of supernatants from HCMV-infected macrophage cultures (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that HCMV-infected cells produce one or several soluble factors that suppress CD4+ T-cell proliferation or that HCMV inhibits T-cell activation. To further examine the effect of HCMV-induced soluble factors on the expression of T-cell activation markers, the expression of CD69 and CD45RO on PHA-stimulated PBMCs was measured in the presence of supernatants from uninfected or HCMV-infected macrophage cultures. HCMV did not inhibit the expression of CD69 and CD45RO (Fig. 5B) on PHA-stimulated PBMCs. However, the relative number of T cells present in PHA-stimulated PBMCs was unchanged in samples in the presence of supernatants from HCMV-infected macrophages compared to that in unstimulated cells (data not shown). In contrast, the relative number of T cells in PHA-stimulated PBMCs was increased multiple times (data not shown). These results imply that HCMV mediates inhibition of T-cell proliferation, yet T-cell activation markers are present on these cells.

FIG. 5.

Soluble factor or factors produced by HCMV-infected macrophages suppress T-cell proliferation. Supernatants from uninfected or HCMV-infected macrophage cultures were incubated with PBMCs and PHA. T-cell proliferation was measured (A), and expression of the activation markers CD69 and CD45RO was analyzed by flow cytometry (B) at 3 days poststimulation. Panel A shows inhibition of PHA-induced T-cell proliferation by 97% in the presence of supernatants from HCMV-infected macrophage cultures (gray), compared to that in uninfected macrophages (hatched bar). In panel B; CD4 + T cells express the activation markers CD69 and CD45RO after PHA stimulation in the presence of supernatants from uninfected or HCMV-infected macrophage cultures; unstimulated PBMCs (a and d), PHA-stimulated PBMCs in the presence of supernatants from uninfected macrophage cultures (b and e), and PHA-stimulated PBMCs in the presence of supernatants from HCMV-infected macrophage cultures (c and f).

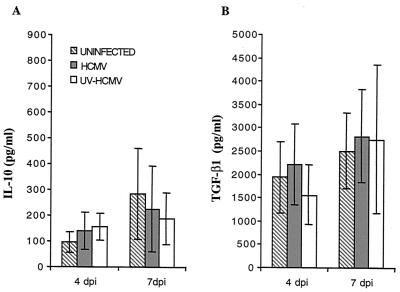

IL-10 and TGF-β1 are the two main cytokines produced by macrophages that are known to negatively influence antigen presentation and T-cell responses. In addition, MCMV was recently shown to interfere with HLA class II molecule expression and inhibition of T-cell proliferation by an autocrine induction of IL-10 (22). To examine whether HCMV-infected macrophages also induced production of IL-10 and TGF-β1, supernatants from uninfected, HCMV-infected, and UV-HCMV-infected macrophage cultures were collected at 4 and 7 dpi and measured for the concentration of IL-10 and TGF-β1 by ELISA. Supernatants from HCMV- and UV-HCMV-infected macrophages did not demonstrate a significantly increased level of either IL-10 or TGF-β1 at 4 or 7 dpi compared to uninfected cells (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

IL-10 (A) and TGF-β1 (B) production is not affected by HCMV infection in macrophages. The production of IL-10 or TGF-β1 was measured in supernatants from uninfected (hatched bars) or HCMV (gray bars)- and UV-HCMV (white bars)-infected macrophages at 4 and 7 dpi. A significant difference in the production of IL-10 or TGF-β1 was not demonstrated in supernatants obtained from uninfected or HCMV- and UV-HCMV-infected macrophages.

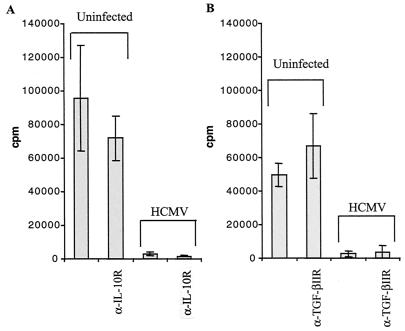

Since HCMV encodes an IL-10 homologue, inhibition of T-cell proliferation may be due to binding of this homologue to IL-10Rs on T cells. Therefore, PBMCs were stimulated with PHA in the presence of an anti-IL-10R antibody, in the presence of supernatants from uninfected or HCMV-infected macrophage cultures. Since TGF-β1 can exist in either an active or an inactive form, which the ELISAs cannot distinguish between, cells were also incubated with an antibody blocking TGF-β1R and TGF-βIIR. Neither blocking of IL-10R nor blocking of TGF-β1R or TGF-βIIR resulted in increased proliferation of PBMCs incubated with supernatants from HCMV-infected cells (Fig. 7). Thus, the reduced expression of HLA class II molecules and the suppressive effects on T-cell proliferation observed in HCMV-infected cultures were not mediated by induction of IL-10, TGF- β1, or the HCMV-encoded IL-10 homologue.

FIG. 7.

Blocking of the IL-10R or the TGF-βIIR does not affect T-cell proliferation. IL-10R and TGF-βIIR on PBMCs were blocked with polyclonal antibodies and then stimulated with PHA in the presence of supernatants from uninfected or HCMV-infected macrophages. Antibody blocking of the IL-10R (A) or the TGF-βIIR (B) did not enhance T-cell proliferation in the presence of supernatants from HCMV-infected macrophage cultures.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we examined the ability of HCMV to modulate the expression of HLA class II molecules on infected monocyte-derived-macrophages and the viral effect on a tetanus-specific T-cell proliferative response. We present three important findings. (i) HCMV infection induces decreased expression of HLA-DR, -DQ, or -DP on infected macrophages in a majority of the experiments. (ii) HCMV utilizes at least two different mechanisms to decrease HLA class II molecule expression on infected macrophages at an early phase (1 dpi, independent of virus replication) and at a late phase (4 dpi, dependent on virus replication) after infection. (iii) A profound inhibition of a tetanus-specific proliferative CD4+ T-cell response was observed in HCMV-infected cultures, which was mainly mediated by soluble factors, which did not include IL-10 or TGF-β1. The mechanisms of HCMV's effect on HLA class II expression and the identification of the cytokines that mediate inhibition of T-cell activation were not clarified in this study. Despite this fact, these experiments, which try to mimic the in vivo situation in patients, are very informative.

Macrophages are believed to play an important role in HCMV dissemination and latency (31) and are key cell types in the immune system, since these cells function as antigen-presenting cells and thereby orchestrate the activation of different subsets of lymphocytes. Thus, HCMV's effect on macrophages to inhibit antigen presentation and T-cell activation in macrophage cultures may have a considerable impact on immunological clearance of the infection. Our study extends previous findings regarding HCMV's effect on the expression of HLA class II expression, to describe a viral effect on the constitutive expression of all three HLA class II molecules, DP, DQ, and DR. These results show that HCMV is capable of affecting all three HLA class II molecules in a majority of the experiments (90%). On the other hand, increased expression of HLA class II molecules was sometimes observed on infected macrophages from certain donors. For example, HCMV-infected macrophages with reduced expression of HLA-DR could demonstrate increased expression of HLA-DP and/or -DQ. In order to try to explain the variation in the effect on HLA class II expression, HLA class II typing was performed, but did not reveal a significant effect, or absence of an effect, for certain HLA class II alleles. Instead, this result may be dependent on the cellular infection level, undefined bystander factors, or biological variation between individuals. In addition, HCMV infection of macrophages is difficult to study in vitro, which limits the ability to control infection levels, the virus effect on individual alleles in individual cells, and the effect on T-cell proliferation other than in parallel culture dishes. Despite these problems, a profound effect on cellular PHA-induced proliferation in the presence of supernatants from HCMV-infected macrophage cultures was constantly observed. Specific T-cell proliferation against tetanus toxoid peptides was inhibited by 66 to 90%, and HLA class II expression was reduced but still well detectable in cultures in which 28 to 70% of the macrophages were HCMV infected. In the case of the effect on HLA-DR expression by UV-inactivated virus, the inhibition of HLA-DR expression was significant but low, yet the effect on T-cell proliferation was profound. The discrepancy between the effects of the surface expression of HLA class II molecules on HCMV-infected macrophages and the inability of HCMV-infected macrophages to induce a CD4+ T-cell response was not dependent on a reduction in HLA class II molecule expression, but rather on soluble factors produced in the infected cultures. In support of this hypothesis, MCMV was recently shown to downregulate MHC class II expression by an autocrine induction of IL-10 (22), which was dependent on active virus replication. In addition, a functional IL-10 homologue, UL111a, was recently identified in the HCMV genome. However, in this study, HCMV's effect on HLA class II expression and inhibition of antigen presentation was not mediated by induction of IL-10 or TGF-β1, the two main cytokines produced by macrophages, which negatively influence antigen presentation and T-cell responses. Furthermore, we present indirect evidence that suggests that the recently identified HCMV IL-10 homologue (UL111a) was not involved in inhibition of T-cell proliferation, since antibodies blocking the IL-10R did not reverse the negative effect on T-cell proliferation in HCMV-infected macrophage cultures. Thus, other cellular cytokines induced upon HCMV infection or undefined cytokine homologues produced by HCMV most likely interfere with antigen presentation and T-cell proliferation. Interestingly, we here observed that HCMV did not inhibit the expression of T-cell activation markers, but the virus did mediate inhibition of T-cell proliferation, as demonstrated by 3H incorporation and by examining the relative number of cells in individual samples. Thus, it is unlikely that HCMV interferes with the expression of costimulatory or cell adhesion molecules in infected cells or that HCMV-encoded proteins interfere specifically with presentation of tetanus toxoid peptides, which results in profound inhibition of T-cell proliferation in this experimental setting.

The HCMV genes involved in downregulation of HLA class II expression could not be identified in these experiments, since other cell systems will be more suitable for such studies. However, our results suggest that the two different mechanisms utilized by HCMV to reduce expression of HLA class II molecules at early and late time points after infection are most likely mediated by different HCMV proteins. We have demonstrated an effect on HLA-DR expression by UV-inactivated virus at an early time point after infection. Presumably, HCMV utilizes a structural component carried by the virus to decrease HLA class II expression on infected cells immediately after virus entry, since UV-inactivated virus, but not IVIG-neutralized virus, was able to reduce HLA-DR expression. In support of this finding, the structural HCMV protein pp65 has been shown to be involved in inhibition of IE peptide presentation to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (9). HCMV is also known to interfere with the early action of the JAK/STAT pathway of IFN-γ-induced HLA class II expression on endothelial cells (19, 20), but the viral gene that mediates this effect is yet unknown. In contrast, the late effect was dependent on one or several genes in the US region in a majority of the experiments. This finding is supported by the study by Tomazin et al. (33), who recently demonstrated that downregulation of HLA-DR expression on stable HLA-DR-transfected U373 cells was mediated by the HCMV gene US2. US2 expression led to a degradation of the HLA-DR α-chain and HLA-DM α-chain, which affected the ability of a CD4+ T-cell clone to produce IFN-γ. However, in 23% of the cases in this study, virus replication, but not the presence of US1 to -9 or US11, induced downregulation of HLA class II molecules. The identification of these genes will be a future goal of our studies.

In summary, we demonstrate that HCMV infection generally induced downregulation, and in some cases also induced upregulation of the HLA class II molecules DR, DQ, and DP. While the increased expression of the individual HLA class II molecules may be mediated indirectly by cytokine production upon viral infection, downregulation of HLA class II molecules most likely is mediated by viral proteins as discussed above. More importantly, we consistently show a profound inhibition of T-cell activation in infected cell cultures, which may mimic the in vivo situation in HCMV-infected patients. Since the observed inhibition of T-cell activation was not dependent on IL-10, TGF-β1, or the effect of the HCMV IL-10R homologue on the IL-10R, identification of soluble proteins induced by HCMV infection will require further studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stanley Riddell and David Johnson for initial fruitful discussions and Erna Möller for helpful discussions during the course of the study and for carefully reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council (K98–06X-12615–01A), the Tobias Foundation (1313/98), the Swedish Childrens Cancer Research Foundation (1998/065), and the Emil and Wera Cornells Foundation. C.S.-N. is a fellow of the Wenner-Gren Foundation, Sweden.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahlfors K. IgG antibodies to cytomegalovirus in a normal urban Swedish population. Scand J Infect Dis. 1984;16:335–337. doi: 10.3109/00365548409073957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn K, Gruhler A, Galocha B, Jones T R, Wiertz E J, Ploegh H L, Peterson P A, Yang Y, Fruh K. The ER-luminal domain of the HCMV glycoprotein US6 inhibits peptide translocation by TAP. Immunity. 1997;6:613–621. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boss J M. Regulation of transcription of MHC class II genes. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerboni C, Mousavi-Jazi M, Linde A, Söderström K, Brytting M, Wahren B, Kärre K, Carbone E. Human cytomegalovirus strain-dependent changes in NK cell recognition of infected fibroblasts. J Immunol. 2000;164:4775–4782. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davignon J L, Castanié P, Yorke J A, Gautier N, Clément D, Davrinche C. Anti-human cytomegalovirus activity of cytokines produced by CD4+ T-cell clones specifically activated by IE1 peptides in vitro. J Virol. 1996;70:2162–2169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2162-2169.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fish K N, Britt W, Nelson J A. A novel mechanism for persistence of human cytomegalovirus in macrophages. J Virol. 1996;70:1855–1862. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1855-1862.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher J M, Prentice H G, Grundy J E. Natural killer cell lysis of cytomegalovirus (CMV)-infected cells correlates with virally induced changes in cell surface lymphocyte function-associated antigen-3 (LFA-3) expression and not with the CMV-induced down-regulation of cell surface class I HLA. J Immunol. 1998;161:2365–2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forbes B A. Acquisition of cytomegalovirus infection: an update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:204–216. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert J M, Riddell S R, Plachter B, Greenberg P D. Cytomegalovirus selectively blocks antigen processing and presentation of its immediate-early gene product. Nature. 1996;383:720–722. doi: 10.1038/383720a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hengel H, Brune W, Koszinowski U H. Immune evasion by cytomegalovirus—survival strategies of a highly adapted opportunist. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:190–197. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hengel H, Flohr T, Hammerling G J, Koszinowski U H, Momburg F. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits peptide translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum for MHC class I assembly. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:2287–2296. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-9-2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones T R, Hanson L K, Sun L, Slater J S, Stenberg R M, Campbell A E. Multiple independent loci within the human cytomegalovirus unique short region down-regulate expression of major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chains. J Virol. 1995;69:4830–4841. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4830-4841.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones T R, Sun L. Human cytomegalovirus US2 destabilizes major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chains. J Virol. 1997;71:2970–2979. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2970-2979.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones T R, Wiertz E J, Sun L, Fish K N, Nelson J A, Ploegh H L. Human cytomegalovirus US3 impairs transport and maturation of major histocompatibility complex class I heavy chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11327–11333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonjić S, Pavić I, Lučin P, Rukavina D, Koszinowski U H. Efficacious control of cytomegalovirus infection after long-term depletion of CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1990;64:5457–5464. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5457-5464.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight D A, Waldman W J, Sedmak D D. Human cytomegalovirus does not induce human leukocyte antigen class II expression on arterial endothelial cells. Transplantation. 1997;63:1366–1369. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199705150-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Roy E, Mühlethaler-Mottet A, Davrinche C, Mach B, Davignon J-L. Escape of human cytomegalovirus from HLA-DR-restricted CD4+ T-cell response is mediated by repression of gamma interferon-induced class II transactivator expression. J Virol. 1999;73:6582–6589. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6582-6589.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lučin P, Pavić I, Polić B, Jonjić S, Koszinowski U H. Gamma interferon-dependent clearance of cytomegalovirus infection in salivary glands. J Virol. 1992;66:1977–1984. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.1977-1984.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller D M, Rahill B M, Boss J M, Lairmore M D, Durbin J E, Waldman J W, Sedmak D D. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits major histocompatibility complex class II expression by disruption of the Jak/Stat pathway. J Exp Med. 1998;187:675–683. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller D M, Zhang Y, Rahill B M, Waldman W J, Sedmak D D. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits IFN-a stimulated antiviral and immunoregulatory responses by blocking multiple levels of IFN-a signal transduction. J Immunol. 1999;162:6107–6113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng-Bautista C L, Sedmak D D. Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with absence of alveolar epithelial cell HLA class II antigen expression. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:39–44. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redpath S, Angulo A, Gascoigne N R, Ghazal P. Murine cytomegalovirus infection down-regulates MHC class II expression on macrophages by induction of IL-10. J Immunol. 1999;162:6701–6707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reusser P. Cytomegalovirus infection and disease after bone marrow transplantation: epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1991;3:52–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reyburn H T, Mandelboim O, Vales-Gomez M, Davis D M, Pazmany L, Strominger J L. The class I MHC homologue of human cytomegalovirus inhibits attack by natural killer cells. Nature. 1997;386:514–517. doi: 10.1038/386514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riddell S R, Reusser P, Greenberg P D. Cytotoxic T cells specific for cytomegalovirus: a potential therapy for immunocompromised patients. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:966–973. doi: 10.1093/clind/13.supplement_11.s966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riddell S R, Walter B A, Gilbert M J, Greenberg P D. Selective reconstitution of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in immunodeficient bone marrow transplant recipients by the adoptive transfer of T cell clones. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;14:78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rinaldo C R., Jr Modulation of major histocompatibility complex antigen expression by viral infection. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:637–650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sedmak D D, Guglielmo A M, Knight D A, Birmingham D J, Huang E H, Waldman W J. Cytomegalovirus inhibits major histocompatibility class II expression on infected endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:683–692. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sedmak D D, Roberts W H, Stephens R E, Buesching W J, Morgan L A, Davis D H, Waldman W J. Inability of cytomegalovirus infection of cultured endothelial cells to induce HLA class II antigen expression. Transplantation. 1990;49:458–462. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199002000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Söderberg C, Larsson S, Bergstedt-Lindqvist S, Möller E. Definition of a subset of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells that are permissive to human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol. 1993;67:3166–3175. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3166-3175.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Söderberg-Naucler C, Fish K N, Nelson J A. Reactivation of latent human cytomegalovirus by allogeneic stimulation of blood cells from healthy donors. Cell. 1997;91:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomasec P, Braud V M, Rickards C, Powell M B, McSharry P, Gadola S, Cerundolo V, Borysiewicz L K, McMichael A, Wilkinson G W G. Surface expression of HLA-E, an inhibitor of natural killer cells, enhanced by human cytomegalovirus gpUL40. Science. 2000;287:1031–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomazin R, Boname J, Hegde N R, Lewinsohn D M, Altschuler Y, Jones T R, Cresswell P, Nelson J A, Ridell S R, Johnson D C. Cytomegalovirus US2 destroys two compartments of the MHC class II pathway, preventing recognition by CD4+ T cells. Nat Med. 1999;5:1039–1043. doi: 10.1038/12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warren A P, Ducroq D H, Lehner P J, Borysiewicz L K. Human cytomegalovirus-infected cells have unstable assembly of major histocompatibility complex class I complexes and are resistant to lysis by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 1994;68:2822–2829. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2822-2829.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wentworth B B, French L. Plaque assay of cytomegalovirus strains of human origin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1970;135:253–258. doi: 10.3181/00379727-135-35031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiertz E J, Jones T R, Sun L, Bogyo M, Geuze H J, Ploegh H L. The human cytomegalovirus US11 gene product dislocates MHC class I heavy chains from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Cell. 1996;84:769–779. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]