Abstract

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common monogenic kidney disorder and the fourth leading cause of kidney failure (KF) in adults. Characterized by a reduction in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and increased kidney size, ADPKD exhibits significant variability in progression, highlighting the urgent need for reliable and predictive biomarkers to optimize management and treatment approaches. This review explores the roles of diverse biomarkers—including clinical, genetic, molecular, and imaging biomarkers—in evaluating disease progression and customizing treatments for ADPKD. Clinical biomarkers such as biological sex, the predicting renal outcome in polycystic kidney disease (PROPKD) score, and body mass index are shown to correlate with disease severity and progression. Genetic profiling, particularly distinguishing between truncating and non-truncating pathogenic variants in the PKD1 gene, refines risk assessment and prognostic precision. Advancements in imaging significantly enhance our ability to assess disease severity. Height-adjusted total kidney volume (htTKV) and the Mayo imaging classification (MIC) are foundational, whereas newer imaging biomarkers, including texture analysis, total cyst number (TCN), cyst-parenchyma surface area (CPSA), total cyst volume (TCV), and cystic index, focus on detailed cyst characteristics to offer deeper insights. Molecular biomarkers (including serum and urinary markers) shed light on potential therapeutic targets that could predict disease trajectory. Despite these advancements, there is a pressing need for the development of response biomarkers in both the adult and pediatric populations, which can evaluate the biological efficacy of treatments. The holistic evaluation of these biomarkers not only deepens our understanding of kidney disease progression in ADPKD, but it also paves the way for personalized treatment strategies aiming to significantly improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: ADPKD, polycystic kidney disease, biomarkers, predictive model, prognosis, total kidney volume

ADPKD, the most common monogenic kidney disorder, ranks as the fourth leading cause of KF in adults.1,2 Pathogenic variants in 2 primary genes, PKD1 and PKD2, represent around 78% and 15% of cases, respectively.3,4 Additional genes, including IFT140, GANAB, ALG5, ALG8, ALG9, DNAJB11, and NEK8 are associated with polycystic kidney disease, underscoring the genetic complexity of this disease.5, 6, 7 ADPKD exhibits a vast array of clinical outcomes, with half of the patients developing KF by their sixth decade of life.2 Kidney cysts, which develop as early as in utero,8 grow gradually throughout the life of patients.9 The decline in kidney function typically occurs at variable rates depending on age and severity of cystic burden, averaging an estimated GFR (eGFR) decline of 4 to 6 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr.10 Rapid progressors are patients who reach KF at an earlier age, and is defined by Chebib and Torres as the age at which a patient reaches kidney failure before the 75th percentile of the overall ADPKD population who will eventually reach kidney failure. This method accounts for variations in KF onset as it could change over time and geography and may be considered superior to an arbitrary age cutoff, such as age < 55 years, as it ensures that the definition evolves with the population data.11 These patients may significantly benefit from disease-modifying therapies. Given the high phenotypic variability in ADPKD combined with the delayed onset of GFR decline, biomarkers play a vital role in evaluating disease severity and progression.12 Serving as indicators of biological states, pathological processes, or responses to therapeutic interventions, biomarkers are categorized into several types: prognostic biomarkers forecast the disease trajectory; predictive biomarkers identify individuals who are likely to benefit from a specific treatment; and response biomarkers reflect the biological activity of an intervention.13 These biomarkers are instrumental by pinpointing patients at risk of progression, facilitating targeted monitoring, and enabling early intervention for personalized care. They are also vital in clinical trials, enhancing the selection of participants more likely to achieve primary outcomes.13 In 2015, the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency qualified total kidney volume (TKV) as a prognostic biomarker.14, 15, 16, 17 Our review focuses on the clinical, genetic, molecular, and imaging biomarkers in ADPKD, highlighting their role in evaluating the condition, predicting its progression, and informing treatment decisions (Figure 1).

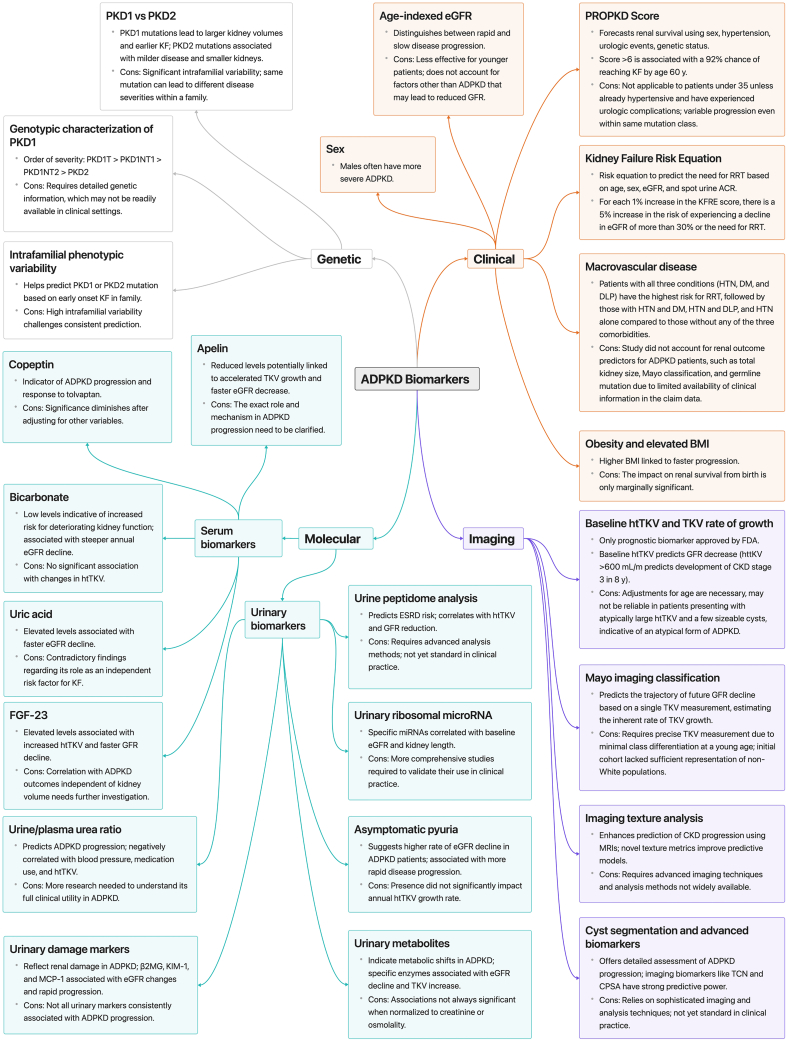

Figure 1.

Comprehensive Overview of ADPKD Biomarkers and Progression Categories. This comprehensive diagram categorizes ADPKD biomarkers into four distinct groups: genetic, clinical, imaging, and molecular. Genetic biomarkers encompass the type of genetic pathogenic variant, the genotypic characterization of PKD1 and intrafamilial variability. They play a pivotal role, with PKD1 pathogenic variants associated with more severe presentation. Further stratification within PKD1 pathogenic variants reveals genotypic variations, such as PKD1T being more severe than PKD1NT1, followed by PKD1NT2 and PKD2. However, genetic factors are limited by variability within families and necessitate detailed genetic information. Clinical markers encompass age-indexed eGFR, with males experiencing more severe ADPKD. Scores like PROPKD, kidney failure risk equation, and considerations of macrovascular diseases highlight risk factors. Additionally, elevated BMI is linked to accelerated progression. Imaging biomarkers include baseline htTKV and TKV growth rate, the only FDA-approved prognostic biomarker. The Mayo imaging classification, texture analysis, cyst segmentation, and advanced imaging biomarkers provide nuanced insights into disease progression. Molecular markers are divided into serum and urinary categories. Serum biomarkers such as apelin, copeptin, bicarbonate, uric acid, and FGF23 offer systemic insights. Urinary biomarkers encompass asymptomatic pyuria, urine/plasma urea ratio, urinary damage markers, metabolites, ribosomal microRNA, and peptidome analysis, shedding light on renal function and disease state. This comprehensive classification facilitates a holistic understanding of ADPKD progression, aiding in prognostication and personalized management. ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio; ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CPSA, cyst parenchymal surface area; DM, diabetes mellitus; DLP, dyslipidemia; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FGF-23, fibroblast growth factor-23; HTN, hypertension; htTKV, height-adjusted total kidney volume; KF, kidney failure; KFRE, kidney failure risk equation; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule 1; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; PROPKD, predicting Renal Outcome in Polycystic Kidney Disease; RRT, renal replacement therapy; TCN, total cyst number; TKV, total kidney volume; β2MG, β2 microglobulin.

Clinical Biomarkers

eGFR

Age-indexed eGFR distinguishes between rapidly and slowly progressive disease.18 According to a position statement from the European Renal Association Working Group on Inherited Kidney Disease and the European Rare Kidney disease reference NETwork, patients with ADPKD are considered fast progressors if criteria for both age-indexed eGFR and the rate of eGFR decline are met. Patients qualify as rapid progressors based on the following age-specific eGFR thresholds: 18 to 39 years with any eGFR, 40 to 44 years with an eGFR <90 ml/min per 1.73 m2, 45 to 49 years with an eGFR <75 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and 50 to 55 years with an eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. In addition to these criteria, patients must also show a historical eGFR decline of at least 3.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr over a period of ≥4 years. This combined criterion ensures that both current eGFR levels and the rate of decline are considered to accurately identify patients likely to experience fast disease progression.18 However, the rate of related metrics requires knowledge of several prior eGFR values. Furthermore, age-indexed eGFR cannot effectively distinguish rapid from slow progression in younger ADPKD patients, especially those aged between 18 and 30 years, because these patients might have preserved eGFR despite significant cystic burden and increased risk of rapid progression.19

Sex

Biological sex affects ADPKD progression, with males exhibiting higher TKV and more severe kidney disease, reaching KF ∼5 years earlier than females.2,20, 21, 22 Although Chapman et al.22 found that differences in TKV between sexes diminished after height adjustment, Shukoor et al.23 reported that men have higher htTKV at the time of KF. Male sex is also an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality in ADPKD, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.54.24 This sexual dimorphism was attributed to the deteriorating effect of testosterone on renal cell proliferation and cyst enlargement, as well as the renoprotective role of estrogen in rodent models of ADPKD.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30

The PROPKD Score

The PROPKD score, utilizing sex, hypertension (HTN) and/or urologic events before the age of 35 years, and genotype, predicts kidney survival on a subpopulation level.20 The score sums up points assigned to these variables: 4 points for truncating PKD1 pathogenic variants, 2 points for nontruncating PKD1 pathogenic variants, none for PKD2 pathogenic variants; 2 points for the onset of HTN before the age of 35; 2 points for the onset of urologic complications before the age of 35 years, and 1 point for male sex. Scores range from 0 to 9, categorizing patients into low (0–3), intermediate (4–6), and high (7–9) risk groups for KF, with a high precision in disease progression prediction, represented by a time-dependent area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.84 ± 0.02 at 65 years. A PROPKD score of ≤3 indicated no KF onset before the age of 60 years with an 81.4% negative predictive value. Conversely, a PROPKD score of >6 predicted KF onset before age of 60 years with a 90.9% positive predictive value (PPV).20 Notably, its application is limited in patients aged <35 years who have not yet manifested HTN or urological events. A post-hoc analysis of the TEMPO 3:4 trial indicated that participants with intermediate and high, but not low, PROPKD scores had significantly lesser eGFR loss with tolvaptan compared with placebo. This confirmed the predictive value of the PROPKD score and potential in enhancing patient selection for clinical trials.31

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Higher BMI is a risk factor for disease progression in ADPKD. In the HALT Group A study, annual TKV growth rates increased across BMI categories: 6.1% (normal weight), 7.9% (overweight), and 9.4% (obese).32 The study also found that each 5-unit BMI increase significantly accelerated TKV growth and negatively impacted eGFR.32 Further analysis on the TEMPO 3:4 study strengthened these observations, demonstrating that for every 5-unit BMI increase, an additional 1.2% annual percent change in TKV was observed.33 Additionally, the odds of experiencing an annual TKV growth of ≥7% versus <5% were significantly higher for overweight (OR = 2.04) and obese (OR = 4.31) individuals compared to those of normal weight.33 While there was a strong association between BMI and increased TKV, the variation in eGFR decline across BMI categories was not statistically significant, secondary to the studies’ early disease stage cohorts and shorter duration of observation. Additionally, the effect of tolvaptan on TKV rate of growth and eGFR rate of decline was similar across different BMI groups.33 However, a study by Nowak et al.,34 which examined visceral adipose tissue instead of BMI in ADPKD patients, found different results. Among 1053 ADPKD patients from the TEMPO 3:4 trial, the effect of tolvaptan on TKV rate of growth and eGFR rate of decline was reduced with increasing visceral adiposity, suggesting that visceral adiposity may serve as a more sensitive biomarker compared to BMI.34

Macrovascular Diseases

Macrovascular diseases are associated with a decline in kidney function in ADPKD. In a retrospective study characterizing patients with ADPKD who reached KF, htTKV was smaller with age, whereas the prevalence of macrovascular disease including HTN, cerebrovascular accidents, and cardiovascular diseases significantly increased from 8% in patients <47 years of age to 40% in patients >61 years of age.23 Additionally, macrovascular diseases were associated with a lower htTKV at KF in women.23 This study hypothesized that cystic growth is the predominant mechanism in younger patients with KF, whereas aging-related factors, including vascular disease, gain importance as patients age, particularly in women.23 In another study, it was found that cardiometabolic comorbidities such as HTN, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia significantly increased the risk of all-cause mortality and kidney replacement therapy.24

Salt Intake

Higher salt intake is associated with faster disease progression.35 In a multivariate analysis accounting for, age, sex, body surface area, htTKV, PKD genotype, and urea excretion, each additional gram of salt intake was associated with a −0.11 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr change in eGFR (95% CI: [−0.20 to −0.02]; P = 0.02). Furthermore, sodium excretion was significantly associated with an increase in htTKV by 0.63%/yr per 18 mmol of sodium (95% CI: [0.40–0.87]; P <0.001).35

Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE)

The kidney failure risk equation is a validated tool that uses a patient’s age, gender, eGFR, and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio to predict the 2- and 5-year need for kidney replacement therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).36 When applied to the ADPKD population in a retrospective cohort study, kidney failure risk equation improved prediction of ≥30% decline in eGFR or KF beyond TKV alone at 1, 3, and 5 years.37 Clinical biomarkers are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical biomarkers in ADPKD

| Biomarkers | Description | Comments | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR indexed for age and eGFR rate of decline18,19 | Slow progressors | Patients aged 40–44 yr with eGFR ≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 OR patients aged 45–49 yr with eGFR ≥75 ml/min per 1.73 m2 OR Patients aged 50–55 yr with eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. |

Cannot distinguish rapid from slow progression in those aged 18–30 yr. |

| Rapid progressors |

eGFR decline ≥3.0 ml/min per yr over ≥4 yrs. |

||

| Demographics | Sex20, 21, 22,24 | Adult males have a higher TKV than adult females. Males tend to reach KF earlier than females. |

|

| BMI32 | Annual % change in TKV:

|

||

| PROPKD score20 | 0–3 Low risk |

Time dependent area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve, AUC of 0.846 ± 0.02 at 65 yr of age.PROPKD score ≤3 has an 81.4% NPV of the absence of KF before 60 yr of age.PROPKD score >6 has a 90.9% PPV of KF before 60 yr. | PROPKD score is not applicable to patients under 35 yr unless they are hypertensive or have experienced urologic complications. |

| 4–6 Intermediate risk | |||

| 7–9 High risk | |||

| Macrovascular diseases23,24 | Correlation between macrovascular disease scores and lower htTKV at KF in women when accounting for age in the multivariate model. ADPKD patients with all three conditions (HTN, DM, and DLP) had the highest risk for RRT (HR: 4.15, 95% CI: 3.27–5.27), followed by those with HTN and DM (HR: 3.62, 95% CI: 2.82–4.65), HTN and DLP (HR: 3.54, 95% CI: 2.91–4.31), and HTN alone (HR: 3.10, 95% CI: 2.62–3.66) compared to those without any of the three comorbidities. |

||

| Dietary salt intake35 | Higher dietary salt intake is linked to accelerated disease progression in ADPKD patients. Each additional gram of salt intake was associated with an eGFR change of −0.11 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per yr (95% CI: −0.20 to −0.02; P = 0.02). | ||

| Kidney failure risk equation37 | Risk equation based on age, sex, eGFR, and spot urine ACR | KFRE independently predicted an eGFR decline of >30% or the need for RRT, with a hazard ratio of 1.05 (95% confidence interval: 1.04–1.05 per 1% increase in KFRE score) |

ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; AUC, area under the curve; BMI, body mass index; DLP, dyslipidemia; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HTN, hypertension; htTKV, height-adjusted total kidney volume; KF, kidney failure; KFRE, kidney failure risk equation; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; RRT, renal replacement therapy; TKV, total kidney volume.

Imaging Biomarkers

TKV and htTKV

The Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease (CRISP) study established that TKV is a valuable prognostic biomarker in ADPKD.9,22 Over a 3-year period, TKV increased significantly, by an average of 204 ± 246 ml, in patients with ADPKD.9 A significant GFR decline was observed only in those with the largest kidneys (>1500 ml).9 htTKV emerged as a more precise predictor of kidney function decline. It showed a consistent negative correlation with GFR over time and effectively predicted CKD stage 3 development within 8 years.22 The odds of reaching CKD stage 3 increased by 1.48-fold for each 100 ml increment in baseline htTKV.22 HtTKV increase significantly preceded GFR decline, with GFR changes becoming apparent after the sixth year of follow-up, whereas htTKV continued to increase significantly within 1 year reaching >55% from baseline after 8 years.22 These findings led the Food and Drug Administration to qualify TKV as a prognostic biomarker.2,38 Additionally, height-adjusted kidney length, measured via ultrasound, can be used as a valuable alternative to TKV in time- and resource-limited circumstances. A kidney length of >16.5 cm on US predicted the development of CKD stage 3 within 8 years with an AUC of 0.86.39 A recent cross-sectional study found that combining height-adjusted mean kidney length (>9.5 cm/m) with PKD1 truncating genotype increases the PPV of reaching KF by the age of 60 years to 100%.40

The Mayo Imaging Classification (MIC)

MIC was proven valuable in identifying patients with rapid disease progression. This system adjusts htTKV to age and categorizes ADPKD patients, aged ≥ 15, into 5 subclasses (1A–1E) based on estimated kidney growth rates, with classes 1C to 1E, representing rapid progression.41 Data analysis from the Mayo Clinic Translational Polycystic Kidney Disease Center and CRISP patients showed significant differences in kidney survival between these subclasses. Patients in the 1E subclass exhibited the most rapid disease progression and the highest risk of KF, with HRs indicating increased risk as patients moved from 1A to 1E.41 Additionally, analyses of the HALT and CRISP studies support that the rate of kidney growth predicts long-term GFR trajectory in adults with ADPKD with a coefficient b = −0.89 (P < 0.001).42 This finding underscores a curvilinear, age- and class-specific acceleration in GFR decline, where each progression from class 1B to 1E correlates with an increase in the rate of decline by 0.89 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr. Notably, the decline is most pronounced in class 1E, starting from −3.25 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr for individuals aged 20 to 30, increasing to −6.05 ml/min per 1.73 m2 year by ages 50 to 60.42 Additionally, the average (± SD) age of KF onset was 43.4 (± 7), 52.5 (± 8.6), 58.4 (± 7.9) and 65 (± 6.8) years for MIC1E, 1D, 1C, and 1B respectively.23 Another study examined the influence of genotype and imaging information on predicting functional and structural outcomes in ADPKD.21

Imaging Texture

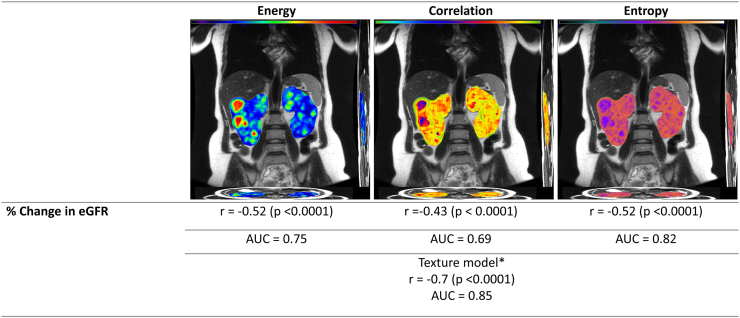

Imaging texture may add value to prognostication in ADPKD. Texture refers to the structural arrangement and the appearance of various intensity levels within an image. In a study by Kline et al.,43 using an ADPKD patients’ cohort with T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and baseline eGFR >70 ml/min per 1.73 m2, 9 texture features including entropy, gradient, contrast, dissimilarity, homogeneity, energy, correlation, and Angular Second Moment were calculated (Figure 2). The addition of these texture metrics, particularly entropy, correlation, and energy, to traditional predictors (age, eGFR, htTKV) significantly improved the model’s performance. These features correlated well with ≥30% decrease in eGFR and accurately differentiated patients who progressed to CKD stages 3A or 3B. For instance, entropy held the strongest predictive power, with AUC values of 0.93, 0.86, and 0.82 for predicting progression to CKD stages 3A and 3B and a 30% or more reduction in eGFR, respectively. Combining these novel texture features with other non-image-based biomarkers holds promise for enhancing personalized clinical decision-making in ADPKD. Further studies are required to validate this novel biomarker, which is not yet widely available, and to expand its accessibility.

Figure 2.

Imaging texture analysis. This figure showcases MRI images analyzed for texture features—energy, correlation, and entropy—illustrating their correlation with the percentage change in eGFR. Energy measures the total of the squared values in the gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) and serves as an indicator of tissue homogeneity. It is inversely related to entropy. Correlation assesses the dependency of grayscale values in kidney voxels, indicating the likelihood of specific pixel pairs occurring together. Entropy measures the level of disorganization in the kidney. Kidneys displaying cyst distributions that appear random will have greater entropy values. The correlations (r) for energy, correlation, and entropy with % change in eGFR is −0.52, −0.43, and −0.52, respectively, all with significant P-values (<0.0001), and AUC values of 0.75, 0.69, and 0.82. Additionally, the texture model, which includes age, eGFR, height-adjusted total kidney volume (htTKV), plus the aforementioned texture features, demonstrates a strong correlation (r = −0.7, P < 0.0001) with an AUC value of 0.85, highlighting its enhanced predictive power for assessing the rate of kidney function decline. ∗Texture model: Age + eGFR + height-adjusted total kidney volume (ht TKV) + energy + correlation+ entropy. AUC, area under the curve; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; KF, kidney failure; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

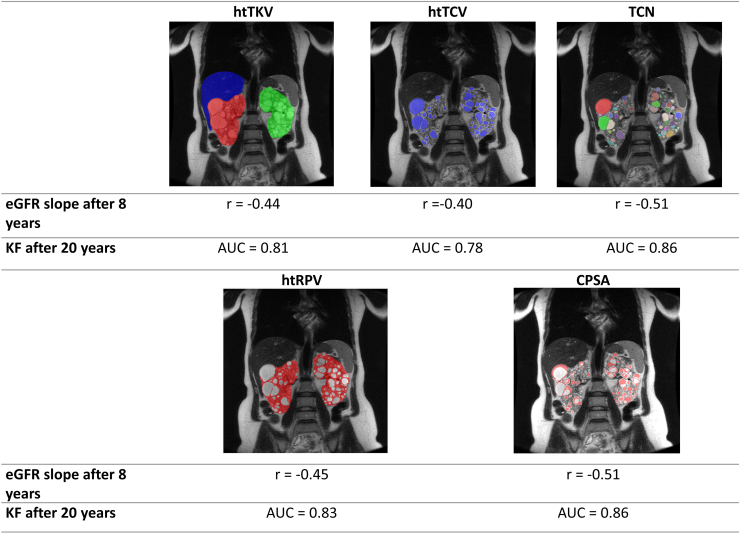

Cyst Segmentation and Advanced Imaging Biomarkers

Cyst segmentation and granular details on cyst-derived imaging biomarkers offer a novel way to assess the progression of ADPKD. These biomarkers, including TCV, renal parenchyma volume (RPV), TCN, and CPSA were applied in a study of 232 ADPKD patients from the CRISP cohort.44 The study found strong negative correlations between the imaging biomarkers, and eGFR slope after an 8-year follow-up, including htTKV (r = −0.44), height-adjusted TCV (htTCV) (r = −0.40), height-adjusted RPV (htRPV) (r = −0.45), TCN (r = −0.51), and CPSA (r = −0.51) (Figure 3). The receiver operating characteristic analysis demonstrated that these had a strong predictive power, with CPSA significantly outperforming htTKV in predicting kidney function. Furthermore, net reclassification improvement analysis indicated that these imaging biomarkers, especially TCN and CPSA, improved predictions compared to traditional htTKV methods, which include htTKVe (ellipsoid) and htTKVs (stereology).44 Additionally, a study based on the ADPKD Tolvaptan Treatment Registry introduced Cyst Fraction, which measures the proportion of the kidney occupied by cysts.45 Over 1 year, the Cyst Fraction increased significantly from 50.82% to 52.71% (P = 0.004) and was positively correlated with age and cysts’ volume. It was also negatively correlated with kidney function and emerged as an independent predictor of ADPKD progression. Additionally, advanced imaging biomarkers identified high TCN, large cysts and stretched parenchyma in patients who reached KF before the age of 46.46 Conversely, those who reached KF after 56 exhibited a lower cystic burden, vascular comorbidities and parenchymal atrophy.46

Figure 3.

Height-adjusted total kidney volume and advanced imaging biomarkers. This figure presents a series of MRI images assessing the relationship between various imaging parameters and the progression of kidney disease. The top row features MRI images highlighting height-adjusted total kidney volume (htTKV), height-adjusted total cyst volume (htTCV), and total cyst number (TCN), with corresponding eGFR slope values after 8 years (r = −0.44, r = −0.40, r = −0.51, respectively) and predictive AUC values for kidney failure (KF) after 20 years (0.81, 0.78, 0.86, respectively). The bottom row displays MRI images focusing on height-adjusted total parenchymal volume (htTPV) and cystic parenchymal surface area (CPSA), with eGFR slope values of −0.45 and −0.51 and AUC values for KF after 20 years of 0.83 and 0.86. This figure demonstrates the prognostic significance of these imaging biomarkers in forecasting long-term outcomes in kidney disease. AUC, area under the curve; CPSA, cyst-parenchymal surface area; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; htRPV, height-adjusted renal parenchymal volume; htTCV, height-adjusted total cyst volume; htTKV, height-adjusted total kidney volume; KF, kidney failure; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TCN, total cyst number.

Genetic Biomarkers

PKD Genotype and Intrafamilial Variability

ADPKD exhibits significant variability in its progression, with genetic factors playing a crucial role (Table 2). A study by Barua et al.47 highlighted the predominance of PKD1 and PKD2 pathogenic variants, accounting for 74% and 26% of families, respectively.47 The distribution of PKD1 and PKD2 variants among APDKD families will continue to change as other ADPKD variants such as ADPKD-IFT140 and ADPKD-GANAB are identified. PKD1 or PKD2 variants significantly impact disease severity and progression. In fact, patients with PKD2 pathogenic variants were shown to have smaller TKVs across all age groups, with an average TKV of 711 ± 298 ml, significantly lower than the 1197 ± 683 ml observed in patients with PKD1 variants (P = 0.001).9 Over 3 years, TKV increased substantially in both groups, but PKD1 pathogenic variant carriers had a larger increase (245 ± 268 ml) compared to PKD2 pathogenic variant carriers (136 ± 100 ml) (P = 0.03).9 Additional analysis from the CRISP cohort found that PKD1 pathogenic variants have a more aggressive early-onset cytogenesis compared to PKD2 pathogenic variants, evidenced by the significantly larger number of cysts found at baseline in patients with PKD1 pathogenic variants with a mean of 30.79 cysts compared to a mean of 18.76 cysts in patient with PKD2 pathogenic variants (P <0.0001).48

Table 2.

Genetic biomarkers in ADPKD

| Genetic biomarker | Description |

|---|---|

| PKD121 |

|

PKD1T

| |

PKD1NT1

| |

PKD1NT2

| |

| PKD221 |

|

| Family history & Intrafamilial variability21,47,49 |

PKD1

|

ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; KF, kidney failure.

Patients with PKD1 truncating (PKD1T) pathogenic variants reach KF at a median age of 55.6 years, compared with 67.9 years in PKD1 non-truncating (PKD1NT) carriers.22 There’s a noticeable difference in kidney structure among genotypes, with PKD1T and PKD1NT1 (nontruncating, fully penetrant) variants associated with larger kidney volumes compared to PKD1NT2 (nontruncating, hypomorphic) and PKD2 variants.21 It is also observed that PKD1T and PKD1NT1 variants have a relatively linear decrease in eGFR over time from a younger age, compared to PKD1NT2 variants which maintain initial stability but experiences a sharper decline in later years.21 Incorporating genotypic factors along with sex, baseline eGFR, and BMI provided significant prognostic accuracy for time to KF, achieving a C-index of 0.824.21 This level of precision closely parallels the one seen in the MIC model. Furthermore, integrating genotype with the MIC model slightly increased its discriminative ability in predicting time to KF or a 50% eGFR reduction/KF, elevating the C-index to 0.845.21

Whereas family history may offer valuable clues to disease progression in individual ADPKD patients, its utility is often limited by the significant variability in disease progression among family members. Early onset of KF in a family member, specifically at or before the age of 55, suggests the presence of a PKD1 pathogenic variant.47 Conversely, KF occurring at or after age 70 in a family member indicates a PKD2 pathogenic variant.47 This distinction, however, does not take into account the less severe disease course caused by PKD1NT pathogenic variants, especially PKD1NT2, whose carriers reach KF at a median age of 66.2 years.21 Additionally, the occurrence of kidney disease discordance within families also becomes more common as family size increases, highlighting significant variability in disease progression, even among same family members of the same family.49 The extended Toronto Genetic Epidemiology Study of Polycystic Kidney Disease cohort analysis revealed a moderate heritability (35% to 70%) for the age at KF onset among different pathogenic variants, highlighting the variable influence of PKD1 or PKD2 variants on disease severity and progression.49 This was further demonstrated in another cohort by the significant familial variability in the age of KF onset, despite sharing identical PKD pathogenic variants, with an average difference of KF onset among family members close to 14 years.23 Mosaicism can result in wide range of disease severity, even within the same family. Essentially, not all cells carry the genetic mutation responsible for ADPKD, leading to variability in the expression of the disease.50 In a study by Elhassan et al.,51 at least 13% of families exhibited marked intrafamilial variability defined as having at least 1 severe and 1 mild case within the family, 66.6% of those with PKD1 nontruncating (PKD1NT) pathogenic variants compared to 16.6% with PKD1 protein truncating (PKD1T) pathogenic variants. Severity was assessed according to prespecified criteria related to the age at KF, PROPKD score, MIC, and ultrasound findings. Possible genetic factors influencing phenotypic severity and intrafamilial variability include haploinsufficiency and “two-hit models,” the presence of “cis” versus “trans” PKD variants, digenic and polygenic inheritance, epigenetics, and differences in expression between sex.52

Molecular Biomarkers

Serum Bicarbonate

With the progression of CKD, the per-nephron excretion of ammonium fails to handle the daily acid load generated, resulting in metabolic acidosis.53 ADPKD patients with a preserved GFR excrete less ammonium after an acid challenge than their healthy counterparts secondary to the structural alterations inherent to ADPKD.54 In the DIPAK intervention trial cohort study which consisted of ADPKD patients with an eGFR of 30 to 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, serum bicarbonate was positively correlated with eGFR and diuretic usage but inversely associated with male sex, BMI, serum potassium, and MIC.55 Low levels of serum bicarbonate indicated a heightened risk of kidney function deterioration, with the lowest tertile showing a significantly increased risk (HR = 2.95, 95% CI: [1.21–7.19]). Each mmol/l decrease in serum bicarbonate raised the risk of worsening kidney function by 21%. However, no significant associations were identified between serum bicarbonate and changes in either htTKV or total liver volume. Although the role of serum bicarbonate has been well established in CKD, further longitudinal studies in ADPKD patients with an eGFR >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 are required to validate its role as a prognostic biomarker in ADPKD, and to establish causality between lower serum bicarbonate and faster kidney function decline.

Serum Copeptin

Molecular biomarkers such as copeptin, an established surrogate for vasopressin levels, are linked with ADPKD severity and progression. Copeptin, part of the vasopressin precursor hormone pre-pro-vasopressin, is released in equimolar amounts with vasopressin from the pituitary gland and then is filtered into the urine.56 In a post-hoc exploratory analysis of the TEMPO 3:4 trial, the relationship between initial copeptin change and annual TKV growth and eGFR decline was examined.57 Baseline copeptin predicted kidney growth and eGFR decline over a 3-year period, independent of sex, age, or baseline eGFR. However, this association disappeared when adjustments were made to TKV. Moreover, a higher baseline level of copeptin was linked with higher effect of tolvaptan on TKV growth and eGFR decline. Intriguingly, a larger percentage increase in copeptin after 3 weeks of tolvaptan treatment compared with baseline (21.9 vs. 6.3 pmol/l, respectively) was associated with a better disease outcome, characterized by reduced TKV growth and lesser eGFR decline.57 These findings highlight the importance of serum copeptin as a predictive biomarker, useful for identifying patients likely to benefit from tolvaptan therapy. Serum copeptin levels could be measured before and during tolvaptan treatment, as those with higher baseline levels or with an increase in copeptin after 3 weeks of treatment are expected to respond better. Regular monitoring of copeptin levels can thus help personalize and optimize treatment strategies for ADPKD patients.

Serum Uric Acid

Serum uric acid (SUA) has emerged as a potential biomarker in ADPKD progression, with historical associations to conditions like HTN and CKD in large cohort studies.58, 59, 60, 61, 62 Recent research highlights SUA's independent role in causing hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovascular complications.58, 59, 60,63 A retrospective study found that each 1 mg/dl increase in UA was linked to a 5.8% increase in TKV, even after accounting for age, sex, and kidney function (P < 0.01).64 Elevated SUA levels also correlated with declining kidney function and an increased risk of KF. The study suggested that early-onset HTN serves as a mediator between SUA levels and KF onset. Another retrospective study found that SUA levels were negatively correlated with initial eGFR but positively correlated with albuminuria, and TKV.65 Patients with hyperuricemia showed a faster annual eGFR decline than those with normal SUA levels. However, a secondary analysis of the HALT PKD trials did not support these findings, showing no significant link between SUA levels and accelerated TKV growth or eGFR decline.66

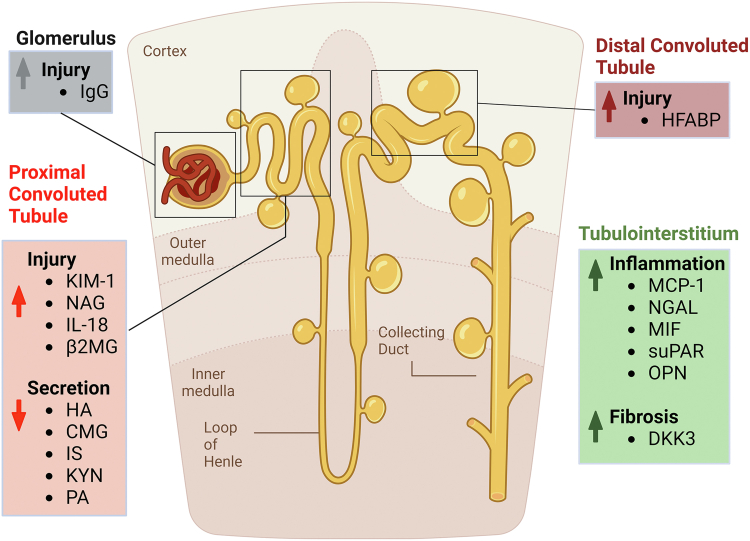

Urinary Inflammatory, Glomerular and Tubular Injury Markers

Urinary biomarkers are invaluable for early disease detection and prognosis (Figure 4). In the Developing Intervention Strategies to Halt Progression of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (DIPAK-1) study, researchers identified key urinary markers for kidney damage: albumin, IgG, β2-microglobulin (β2MG), kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1), heart-type fatty acid-binding protein, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), N-acetyl-b-D-glucosaminidase (NAG), and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL).67 At baseline, all urinary damage and inflammation markers demonstrated a significant association with baseline eGFR. Additionally, all markers, except for β2MG and heart-type fatty acid-binding protein, showed a significant correlation with baseline htTKV.67 Furthermore, β2MG, KIM-1, heart-type fatty acid-binding protein, and MCP-1 were significant indicators of annual eGFR changes and rapid progression with β2MG and MCP-1 being the strongest indicators. A urinary biomarker score, based on β2MG and MCP-1 tertile rankings, demonstrated high predictive potential, surpassing the MIC and the PROPKD score, although the latter did not reach statistical significance.67 These findings were confirmed by Messchendorp et al.68 in a cohort of 104 included ADPKD patients from the University Medical Center Groningen, noting strong associations of β2MG and MCP-1 with annual eGFR change (β2MG: standardized β = −0.35, P = 0.001; MCP-1: standardized β = −0.29, P = 0.009), and a weaker but significant connection for KIM-1 (standardized β = 0.24, P = 0.02). Subsequent analyses revealed that a combination of β2MG and MCP-1, along with conventional risk markers, provided the most robust predictive capability for eGFR changes. Regarding htTKV, initial analyses suggested links between KIM-1, MCP-1, and annual htTKV changes.68 Additionally, a focused subanalysis of the TEMPO 3:4 trial, highlighted the effect of tolvaptan on urinary MCP-1 excretion.69 This revealed that tolvaptan led to a significant reduction in uMCP1 excretion, showcasing a decrease of 13.8 ± 4.4% at 24 months (P < 0.0001) and 14.4 ± 3.7% at 36 months (P < 0.0001), compared to placebo. This effect was consistent across both sexes and in patients with CKD stage 2 and 3.69

Figure 4.

Urinary biomarkers. The graph provides a comprehensive overview of the urinary biomarkers associated with the progression of ADPKD. It highlights the different aspects of renal injury, inflammation, and structural changes characteristic of the disease. In the glomerulus, the presence of IgG is a biomarker for injury. The proximal convoluted tubule shows injury through elevated levels of KIM-1, NAG, IL-18, and β2MG, while reduced secretion of HA, CMG, IS, KYN, and PA indicates tubular dysfunction. The distal convoluted tubule's injury is identified by increased HFABP. In the tubulointerstitium, markers such as MCP-1, NGAL, MIF, suPAR, and OPN signal inflammation, and DKK3 denotes fibrosis. These urinary biomarkers are critical in reflecting the various pathophysiological changes in ADPKD, aiding in the diagnosis and monitoring of the disease. β2MG, beta-2-microglobulin; CMG, cinnamoylglycine; DKK3, Dickkopf-3; HA, hippuric acid; HFABP, heart-type fatty acid-binding protein; IL-18, Interleukin-18; IS, indoxyl sulfate; IgG, immunoglobulin G; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; KYN, kynurenic acid; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MIF, macrophage migration inhibitory factor; NAG, N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin; OPN, osteopontin; PA, pyridoxic acid; suPAR, soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor.

In a CRISP cohort study, urine IL-18 and NGAL were assessed as biomarkers for kidney injury in ADPKD over 3 years.70 Both biomarkers demonstrated a significant linear and quadratic trend over time (P ≤ 0.05), suggesting an initial increase followed by a decrease in subsequent years. Despite these patterns, no association was found between baseline tertiles and quartiles for IL-18 and NGAL concentrations and the percent change in TKV or change in eGFR at 3 years. Additionally, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (an inflammatory marker) was shown to be a significant predictor of GFR decline and CKD stage 3 onset.71

Although these markers show promising applications in predicting disease progression, their clinical use is limited by their restricted availability and challenges associated with standardizing them.

Endogenous Markers of Tubular Secretion

Tubular secretion is the primary method by which the kidneys eliminate endogenous substances that are not filtered by the glomerulus, especially those that are highly protein bound. Reduced kidney tubule clearance of endogenous secretory metabolites by the organic anion transporters is associated with higher KF and mortality risk, independent of eGFR, and is also strongly associated with fibrosis in the tubulo-interstitium.72,73 Some of those secretion markers are hippuric acid, cinnamoylglycine, indoxyl sulfate, kynurenic acid and pyridoxic acid (PA). In 1 study among patients with and without ADPKD, tubular secretion was lower by as much as 30% to 70% in CKD patients with ADPKD demonstrating that this marker may be particularly altered in ADPKD.74 These impairments in tubular secretion were not associated with differences in htTKV indicating the importance of independent functional information that would be missed by relying solely on kidney volume by imaging. Additionally, tubular secretion is critical for delivery of several drugs (including metformin and micro-RNA inhibitors) that are being evaluated as potential therapies for ADPKD.75,76

Urine-to-Plasma Urea Ratio

In ADPKD, while GFR remains stable in early stages, cyst formation alters kidney’s structure, affecting urine-concentrating capacity.77, 78, 79 The urine-to-plasma urea ratio, a predictor of ADPKD progression, correlates with this capacity.80 Maximal urine-concentrating capacity showed a positive correlation with eGFR (standardized β = 0.50; P < 0.001) and a negative correlation with htTKV (standardized β = −0.57; P = 0.03). Both fasting and unstandardized spot urine samples were significantly associated with urine-concentrating capacity (R = 0.90; P <0.001, and R = 0.67; P < 0.001, respectively). The study further revealed that lower urine-to-plasma urea ratios were associated with faster disease progression and higher risk of adverse kidney outcomes. This was evident from the correlation of the early morning fasting spot urine-to-plasma urea ratio with the rate of kidney function decline, both unadjusted (per 1-natural log-transformed unit, β = 1.66; P = 0.05) and adjusted for age, sex, and eGFR (β = 5.56; P <0.001).80 A risk score including this ratio, PKD pathogenic variant, and MIC provided enhanced predictive accuracy for disease progression, with the Harrell C-statistic significantly improved by including the urine-to-plasma urea ratio (C = 0.82, P = 0.03).80

Asymptomatic Pyuria

Inflammation and fibrosis, despite not directly influencing cystic measurements, can crucially affect the kidney parenchyma and kidney function81 and are thus distinguishing pathological hallmarks of ADPKD.82,83 Moreover, heightened levels of inflammatory cell migration alongside the upregulation of chemokines and cytokines have been reported in ADPKD patients.83, 84, 85 Asymptomatic pyuria was suggested as a potential surrogate marker for inflammation when there's no urinary infection.86 In patients with MIC 1C-1D-1E, Asymptomatic pyuria was significantly associated with earlier KF (median 55 yr vs. 59 yr, P = 0.02), with a steeper annual eGFR decline (−3.81 vs. −2.33, P <0.001) when compared to those without pyuria.87 Asymptomatic pyuria presence did not significantly impact the annual htTKV growth rate.87

Urinary Metabolites and Glycolytic Enzymes

Metabolic derangements in ADPKD have been tied to increased aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect), diminished fatty-acid oxidation, and reduced AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity. These metabolic shifts may underlie cyst genesis and expansion.88,89 Researchers explored the relationships between key urinary biomarkers and metabolites, focusing on glycolytic versus oxidative pathways. In the TAME-PKD trial, significant associations were found between certain urinary markers and eGFR decline.90 The urinary excretion of the glycolytic enzyme PKM2, adjusted for osmolality, had a negative relationship with eGFR (r = −0.26, P = 0.009).90 Conversely, urinary cAMP levels, when adjusted for creatinine, were positively associated with eGFR (r = 0.25, P = 0.02). Regarding htTKV, there was a positive link with urinary total protein excretion, adjusted by creatinine (r = 0.20, P = 0.06) and osmolality (r = 0.19, P = 0.07). The ratios of PKM2/creatinine, PKM2/osmolality, LDHA/creatinine, and LDHA/osmolality displayed significant associations.90 In a separate study from the DIPAK Consortium, urinary metabolites were quantified using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.91 The alanine-to-citrate ratio showed a strong connection with eGFR changes, even after adjusting for htTKV. Another study further reinforced this finding, linking a high alanine/citrate level to rapid disease progression.92 Increased betaine levels and reduced phenylacetyl glycine levels were also associated with rapid progression. Notably, the urinary myoinositol/citrate ratio increased significantly more in fast progressors (68%) compared to slow progressors in the DIPAK cohort (6%).92

Table 3 and Table 4 show the current understanding and predictive powers of various biomarkers in ADPKD and to compare the accuracy of different biomarkers in predicting disease progression and outcomes.

Table 3.

Additional molecular biomarkers

| Biomarker | eGFR rate of decline | TKV rate of growth | Validation status | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Apelin93, 94, 95 | ↓a | ↓a | Not validated | Decreased serum apelin levels in ADPKD patients are linked to a more rapid rate of eGFR decline and accelerated TKV growth93 |

| Serum FGF-2396, 97, 98, 99, 100 | ↑a | ↑a | Not validated | The highest quartile of FGF-23 demonstrated a −1.03 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr greater decline in GFR compared to the lowest quartile, and a 0.95% per yr higher growth rate in ln (htTKV) (P = 0.0016).99 For every 1-pg/ml increase in serum FGF-23, the GFR slope declines further by −0.009 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per yr (P = 0.03).99 Additionally, high FGF23 levels are linked to an increased risk of critical outcomes like KF, doubling of serum creatinine, or death, with a hazard ratio of 2.45 (P = 0.03).99 |

| Urinary Osteopontin101 | ↓a | ↔ | Not validated | Urinary OPN levels in ADPKD patients were significantly decreased compared to controls. Among a cohort of 22 patients with an eGFR of >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, urinary OPN levels were notably lower in patients with rapid progression of ADPKD (classified as MIC 1C-1E) compared to slow progressors (classified as MIC 1A-1B) (0.1217 ± 0.06629 μg/mg creatinine; P = 0.03). |

| Urinary DKK3102 | ↑a | ↑a | Not validated | Urinary DKK3 levels in ADPKD patients were significantly higher than controls. A strong positive correlation was found between age and uDKK3 levels in ADPKD patients (P = 0.0013) and a negative correlation with eGFR. The increase in uDKK3 was associated with higher htTKV and advanced CKD stages. Incorporating uDKK3 in predictive models improved their R2 from 0.13–0.16, and further to 0.4991 when combined with copeptin. |

| Urine Peptidome103, 104, 105, 106 | ↑a | ↔ | Validated | Urine peptidome analysis in ADPKD identified 20 peptides with altered excretion in KF vs. controls, 16 of which remained significant in younger KF patients.104 Prognostic models based on these peptides showed high accuracy for KF risk, with AUCs of 0.95 in the development cohort and 0.83 (95% CI: 0.60–0.96; P = 0.0011) in the validation cohort.104 For patients under 24 yr, predicting a GFR reduction >30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 over 8 yr, the AUC was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.76–0.99; P < 0.0001), comparable to the AUC of 0.96 for htTKV. In the CRISP cohort with over 10 yr of follow-up, the AUC was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.79–0.91; P < 0.0001).104 Many identified peptides are products of proteins like antithrombin III and fibrinogen alpha chain, linking them to protease activity and suggesting a direct origin from cystic kidney tissue.106 |

| Urinary MMP-7107 | ↑a | ↔ | Validated | MMP-7 protein abundance was significantly higher in uEVs from ADPKD patients with rapid disease progression (eGFR decline ≥4 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) compared to those with stable disease (eGFR decline ≤2 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr). In spot urine samples, whole-urine MMP-7/creatinine were higher in patients with rapid disease progression compared with patients with stable disease, but this difference did not reach statistical significance. AUC of uEV-MMP-7 for predicting rapid progression was equal to 0.77 and 0.83 in the DIPAK cohort and the Cologne cohort, respectively. |

| Urine Exosome and microRNAs108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114 | ↔ | ↔ | Not validated | Differentially expressed miRNAs, notably from the miR-192/miR-194-2 and miR-30 families, were identified between ADPKD patients and healthy controls. These miRNAs, particularly downregulated in late-stage ADPKD, correlated with clinical markers.114 The miR-30 family showed a significant correlation with baseline eGFR.114 miR-192-5p correlated with mean kidney length (MKL), a surrogate for kidney volume.114 ROC curve analysis of miR-30e-5p yielded an AUC of 0.826. Combining all five targeted miRNAs improved the AUC to 0.889, outperforming MKL alone (AUC 0.634).114 Integrating miRNA with MKL reached an AUC of 0.914, indicating the potential of urinary exosomal miRNAs, in combination with MKL, as biomarkers for ADPKD progression.114 |

↑: Positive association between the biomarker and GFR rate of decline or TKV rate of growth.

↓: Negative association between the biomarker and GFR rate of decline or TKV rate of growth.

↔: Absence of specific directional association between the biomarker and GFR rate of decline or TKV rate of growth.

AUC, area under the curve; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CRISP, Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FGF-23, fibroblast growth factor-23; htTKV, height-adjusted total kidney volume; KF, kidney failure; MKL, mean kidney length; MMP-7, matrix metalloproteinase-7; ROC, receiver operating characteristics; TKV, total kidney volume; uDKK3, urinary Dickkopf-3; uEVs, urinary extracellular vesicles.

Association remains significant after adjusting for other factors.

Table 4.

Comparison of biomarkers’ performance in predicting outcomes in ADPKD

| Biomarker | Type of study | Study population | Metrics used | Clinical significance | Validation status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROPKD Score | Point distribution

|

Cross-sectional study20 | Genkyst cohort of ADPKD patients (n = 1341) | AUC = 0.84 ± 0.02 for predicting renal survival at 65 yr of age | High | Validated |

| Post-hoc exploratory analysis31 | TEMPO 3/4 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an estimated creatinine clearance >60 ml/min, TKV >750 ml, and identified pathogenic variants in PKD1 or PKD2 (n = 749) | Low-risk patients: eGFR rate of decline = −2.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr Intermediate-risk patients: eGFR rate of decline = −3.30 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr High-risk patients: eGFR rate of decline = −3.94 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr |

||||

| Post-hoc exploratory analysis67 | DIPAK-1 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR of 30-60 ml/min per 1.73 m2

|

AUC = 0.65 (0.55–0.75) for predicting rapid progression (eGFR decline rate < −3.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) AUC = 0.60 (0.48–0.73) for predicting rapid progression (eGFR decline rate < −4.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) |

||||

| Body mass index | Post-hoc exploratory analysis32 | HALT study A cohort of nondiabetic ADPKD patients with either hypertension or high-normal BP and an eGFR >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n = 441) | β-estimates = −0.03 (−0.05 to 0.00, per 5-unit increase in BMI) after adjustment | High | Validated | |

| Post-hoc exploratory analysis33 | TEMPO 3/4 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an estimated creatinine clearance >60 ml/min, and TKV >750 ml (n = 1312) | eGFR rate of decline = −0.95 (−2.32 to 0.40, per 5-unit increase in BMI) after adjustment (not significant) | ||||

| Retrospective longitudinal cohort study21 | Analysis cohort:

|

HR = 1.246 (1.125–1.378, per 5-unit increase in BMI) for KF risk | ||||

| Cardiometabolic comorbidities | Retrospective longitudinal cohort study24 | ADPKD patients diagnosed before KF from Taiwan’s NHIRD population-level data (n = 6142) | After adjustment for sex and age:

|

High | Validated | |

| Kidney failure risk equation | Retrospective longitudinal cohort study37 | ADPKD patients with at least one renal US and eGFR value available referred to a Nephrology tertiary care center in Canada (n = 221) | HR = 1.05 (1.04–1.05 per 1% increase in KFRE score) for predicting an eGFR decline of >30% or RRT | Moderate | Validated | |

| Genotype scoring | PKD1T vs. PKD1NT1 vs. PKD1NT2 vs. PKD2 | Retrospective longitudinal cohort study21 | Analysis cohort:

|

Harrel C-statistic: c = 0.824 (P < 0.001) for predicting KF after adjustment for sex, baseline BMI, baseline eGFR | High | Validated |

| Patients with PKD2 pathogenic variant = 1 point Patients with nontruncating PKD1 pathogenic variants = 2 points Women with truncating PKD1 pathogenic variants = 3 points Men with truncating PKD1 pathogenic variants = 4 points |

Cross-sectional study20 | Genkyst cohort of ADPKD patients (n = 1341) | AUC = 0.79 ± 0.02 for predicting renal survival at 65 yr of age | |||

|

PKD2 or non-classified pathogenic variant = 1 point PKD1 non-truncating = 2 points PKD1 truncating = 3 points |

Post-hoc Exploratory analysis80 |

DIPAK1 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR of 30-60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 AND DIPAK observational cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR ≥15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n = 583) | Harrel C-statistic: c = 0.63 for predicting fast progression (eGFR rate of decline <−3.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) | |||

| PKD1 vs. PKD2 or NMD | Retrospective longitudinal cohort study42 | Development cohort:

|

eGFR rate of decline = −1.44 (−1.92 to −0.96) when adjusted for age eGFR rate of decline = −0.61 (−1.08 to −0.13) when adjusted for age and MIC |

|||

| Height-adjusted total kidney volume (htTKV) | Prospective longitudinal cohort22 | CRISP cohort of ADPKD patients with creatinine clearance >70 ml/min (n = 241) | OR = 1.48 (1.23–1.61, per 100 ml increase in baseline htTKV) for CKD stage 3 AUC = 0.84 (0.79–0.90) for predicting CKD stage 3 within 8 yr with a cut-off htTKV >600 cc/m |

High | Validated | |

| Retrospective longitudinal cohort44 | CRISP cohort of ADPKD patients with creatinine clearance >70 ml/min and identified T2-weighted MRIs (n = 232) | AUC = 0.81 (0.72–0.88) for predicting KF after 20 yr with a cut-off htTKV >457.55 ml/m | ||||

| Retrospective longitudinal cohort43 | CRISP cohort of ADPKD patients with creatinine clearance >70 ml/min, identified T2-weighted MRIs, and typical presentation of the disease (n = 122) | AUC = 0.73 (0.64–0.80) for predicting a 30% change in eGFR with a cut-off htTKV >423 ml/m AUC = 0.81 (0.75–0.87) for predicting CKD stage 3A with a cut-off htTKV >457 ml/m |

||||

| Mayo Imaging Classification (MIC) | Retrospective longitudinal cohort41 | Development and internal validation cohort:

|

MTPC patients: HR = 1.84 (1.49–2.26) with progression from subclass 1A to 1E CRISP patients: HR = 4.67 (1.03–21.20) with progression from subclass 1A to 1E |

High | Validated | |

| Retrospective longitudinal cohort study42 | Development cohort:

|

eGFR rate of decline: Coefficient β = −0.89 (−1.07 to −0.71) for each consecutive step up in class from A to E after adjustment for age | ||||

| Post-hoc exploratory analysis67 | DIPAK-1 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR of 30-60 ml/min per 1.73 m2

|

AUC = 0.61 (0.51–0.71) for predicting rapid progression (eGFR decline rate < −3.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) AUC = 0.58 (0.47–0.70) for predicting rapid progression (eGFR decline rate < −4.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) |

||||

| Retrospective case-control study21 | Analysis cohort:

|

Harrel C-statistic: c = 0.830 for predicting ESRD (adjusted for sex, baseline BMI, baseline eGFR) | ||||

| MIC 1A and 2 = 1 point MIC 1B and 1C = 2 points MIC 1D and 1E = 3 points |

Post-hoc Exploratory analysis80 |

DIPAK1 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR of 30–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 AND DIPAK observational cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR ≥15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n = 583) | Harrel C-statistic: c = 0.65 for predicting fast progression (eGFR rate decline < −3.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr | |||

| Texture Analysis | Entropy | Retrospective longitudinal cohort43 | CRISP cohort of ADPKD patients with creatinine clearance >70 ml/min, identified T2-weighted MRIs, and typical presentation of the disease (n = 122) | AUC = 0.93 (0.88–0.97) for predicting CKD stage 3A with a cut-off entropy >9.2 AUC = 0.82 (0.73–0.88) for predicting a 30% change in eGFR with a cut-off entropy >9.1 |

Low | Not validated |

| Correlation | AUC = 0.72 (0.64–0.79) for predicting CKD stage 3A with a cut-off correlation >0.53 AUC = 0.69 (0.62–0.78) for predicting a 30% change in eGFR with a cutoff correlation >0.53 |

|||||

| Energy | AUC = 0.80 (0.74–0.87) for predicting CKD stage 3A with a cut-off energy >1.74 AUC = 0.75 (0.69–0.83) for predicting a 30% change in eGFR with a cut-off energy >1.81 |

|||||

| Advanced Imaging Biomarkers | htTCV | Retrospective longitudinal cohort44 | CRISP cohort of ADPKD patients with creatinine clearance >70 ml/min and identified T2-weighted MRIs (n = 232) | AUC = 0.78 (0.69–0.87) for predicting KF after 20 yr with a cut-off htTCV >212.12 ml/m | Moderate | Not validated |

| htRPV | AUC = 0.83 (0.75–0.89) for predicting KF after 20 yr with a cut-off htRPV >311.78 ml/m | |||||

| TCN | AUC = 0.86 (0.78–0.91) for predicting KF after 20 yr with a cut-off TCN >307 cyst unit | |||||

| CPSA | AUC = 0.86 (0.79–0.92) for predicting KF after 20 yr with a cut-off CPSA >8.51 dm2 | |||||

| Urinary biomarker score (β2MG and MCP-1) | β2MG: • Lower tertile of β2MG excretion = 1 • Middle tertile β2MG excretion = 2 • Upper tertile of β2MG excretion = 3 MCP-1: • Lower tertile of MCP-1 excretion = 1 • Middle tertile MCP-1 excretion = 2 • Upper tertile of MCP-1 excretion = 3 Urinary biomarker score = Sum of points from both β2MG and MCP-1 |

Post-hoc exploratory analysis67 | DIPAK-1 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR of 30–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2

|

AUC = 0.73 (0.64–0.82) for predicting fast progression (annual eGFR decline rate < -3.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) AUC = 0.75 (0.63–0.87) for predicting fast progression (annual eGFR decline rate < −4.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) |

Low | Validated |

| Urine-to-plasma urea ratio |

Post-hoc Exploratory analysis80 |

DIPAK1 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR of 30-60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 AND DIPAK observational cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR ≥15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n = 583) | OR = 1.33 (1.19–1.48, per every 10-U decrease in urine-to-plasma urea ratio) for rapidly progressive disease when analyzed crude OR = 1.35 (1.19–1.52, per every 10-U decrease in urine-to-plasma urea ratio) for rapidly progressive disease when adjusted for sex, PKD pathogenic variant, and Mayo Clinic htTKV class. |

Moderate | Not validated | |

| Upper tertile of urine-to-plasma urea ratio = 1 Middle tertile of urine-to-plasma urea ratio = 2 Lower tertile of urine-to-plasma urea ratio = 3 |

Harrel C-statistic: c = 0.61 for predicting rapid progression (eGFR rate decline < −3.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) | |||||

| Serum Bicarbonate | Post-hoc exploratory analysis55 | DIPAK-1 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR of 30-60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and available serum bicarbonate (n = 296) | HR = 1.21 (1.06–1.37, per each mmol/l decrease in serum bicarbonate) | Low | Not validated | |

| Asymptomatic pyuria | Retrospective longitudinal cohort87 | ADPKD patients seen at Mayo Clinic with at least 1 available CT scan or MRI, available urinalysis, and sequential eGFR values before KF or cyst intervention (n = 807) | Asymptomatic pyuria: eGFR rate of decline = −3.81 (−4.11 to −3.15) Non pyuria: eGFR rate of decline = −2.33 (−2.58 to −2.09) |

Low | Not validated | |

| Combined models | Age + eGFR + HtTKV + entropy + correlation + energy | Prospective longitudinal cohort43 | CRISP cohort of ADPKD patients with creatinine clearance >70 ml/min, identified T2-weighted MRIs, and typical presentation of the disease (n = 122) | AUC = 0.94 for predicting CKD stage 3A AUC = 0.85 for predicting a 30% change in eGFR |

Low | Not validated |

| Sex, PKD pathogenic variant, MIC, and urine-to-plasma urea ratio |

Post-hoc Exploratory analysis80 |

DIPAK1 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR of 30-60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 AND DIPAK observational cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR ≥15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n = 583) | Harrel C-statistic: c = 0.72 for predicting rapid progression (eGFR rate decline < −3.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) | Moderate | Not validated | |

| Age + sex + eGFR + urinary biomarker score | Post-hoc exploratory analysis67 | DIPAK-1 trial cohort of ADPKD patients with an eGFR of 30–60 ml/min per 1.73 m2

|

AUC = 0.73 (0.65–0.81) for predicting fast progression (annual eGFR decline rate < -3.5 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) | Low | Validated | |

| Sex + baseline eGFR + baseline MIC + PKD pathogenic variant + Baseline BMI | Retrospective case-control study21 | Analysis cohort:

|

Harrel C-statistic: c-index = 0.845 for predicting KF | High | Validated | |

Clinical significance was assessed based on several factors including study type, sample size, statistical analysis and adjustment for possible confounders, and clinical availability.

AUC, area under the curve; β2MG, beta-2 microglobulin; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CPSA, cyst-parenchymal surface area; CRISP, Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease; DLP, dyslipidemia; DM, diabetes mellitus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; HTN, hypertension; htTCV, height-adjusted total cyst volume; htTKV, height-adjusted total kidney volume; htRPV, height-adjusted renal parenchymal volume; KF, kidney failure; KFRE, kidney failure risk equation; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MIC, Mayo imaging classification; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MTPC, Mayo Clinic Translational Polycystic Kidney Disease Center; NMD, no mutation detected; RRT, renal replacement therapy; TCN, total cyst number; TKV, total kidney volume.

Special Consideration in Pediatric ADPKD

Animal and human research indicates that younger ages are critical for cyst development and growth, with these processes occurring more rapidly than in adults.115 Consequently, early-life events significantly impact the progression of cysts and CKD in later life, which underscores the urgent need for identifying biomarkers to predict the progression of ADPKD in children. Such biomarkers would enable early patient stratification for preemptive treatment and the identification of therapeutic targets.

MCP-1

In a pediatric ADPKD study by Janssens et al.116 at the University Hospital of Leuven, urinary MCP-1 emerged as a key biomarker for disease progression.116 The study showed higher median urinary MCP-1 levels in ADPKD patients (185.4 pg/mg) compared to controls (154.7 pg/mg, P = 0.010). MCP-1 levels were notably higher in PKD1 variant carriers (192.2 pg/mg) compared to controls (159.7 pg/mg, P = 0.004) but lower in PKD2 carriers (82.6 pg/mg vs. 135.2 pg/mg, P = 0.02). MCP-1 correlated positively with eGFR but not with BMI, urine osmolality, htTKV, or cyst score. Significantly higher MCP-1 levels were found in very early onset or symptomatic ADPKD patients compared to asymptomatic ones (265.2 pg/mg vs. 144.5 pg/mg, P = 0.009), even after adjusting for age, sex, and BMI (P = 0.035). This indicates the utility of urinary MCP-1 in identifying more aggressive forms of ADPKD in children.116

Glomerular Hyperfiltration

In a study involving 180 children with ADPKD aged 4 to 18 years, glomerular hyperfiltration (GH), defined as creatinine clearance ≥ 140 ml/min per 1.73 m2, was linked to a faster increase in renal volume over 5 years (β = +19.3 cm3/yr for GH vs. β= −4.3 cm3/yr for no GH, P = 0.008) and a quicker decline in creatinine clearance for those with GH (β = −5.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr) compared to those without GH (β = +1.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr, P <0.0001).117

The Leuven Imaging Classification (LIC)

In a longitudinal study involving pediatric ADPKD patients younger than 19 years old from the University Hospitals, Leuven, researchers sought to establish the effectiveness of htTKV measured using 3 dimensional ultrasound as a biomarker for distinguishing between slow and fast disease progressors in children.118 The study initially applied the adult MIC model to this cohort, which resulted in significant underestimations of disease severity, particularly in children under 10 years. After adjusting the MIC model parameters, the patient distribution improved across severity scores, but it still did not effectively cover all pediatric ages. A new model called the LIC Pediatric ADPKD Model was proposed, employing a formula htTKV(ml/m) = AxB (age × 1.6), with varying A and B values. The LIC Pediatric ADPKD model more accurately distributed patients across severity scores. The analysis showed an overall eGFR decline of −2.47 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr across the cohort, with different rates observed across LIC classes ranging from −0.63 to −4.74 ml/min per 1.73 m2/yr. Additional data validation demonstrated that the LIC model offered a more nuanced patient categorization compared to the MIC model, which tended to predominantly score young adults in the highest severity class.

Additional Pediatric Biomarkers

In a cohort of 15 children with ADPKD with a similar number of age- and gender-matched controls, there was no significant difference in urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin levels between ADPKD patients and controls (ADPKD: 26.36 ng/ml; controls: 27.24 ng/ml; P = 0.96).119 Furthermore, urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin did not correlate with TKV (t [13] = 0.41; r = 0.11; P = 0.68) or htTKV (t [13] = 0.36; r = 0.10; P = 0.71), underscoring its limited value as an early biomarker for disease progression in pediatric ADPKD patients.119 In another cohort, metabolic profiling and pathway analysis revealed significant shifts in metabolites related to arginine metabolism (including the urea and nitric oxide cycles), asparagine and glutamine metabolism, the methylation cycle, and the kynurenine pathway.120 They also correlated with changes in htTKV and were associated with disease progression.120

Integrated Interpretation of Current Clinical Use of Biomarkers and Future Directions

Predicting the onset of KF in patients with ADPKD is a key area of clinical practice and research. Accurate predictions significantly impact patients’ expectations regarding their clinical trajectory and assist clinicians in risk stratification. Effective risk stratification is essential for determining inclusion criteria in clinical trials and assessing the risk-benefit ratio when considering disease-modifying treatments once approved. ADPKD is a complex condition shaped by clinical, imaging, genetic, and molecular factors, as this review highlights. Current clinical practice primarily utilizes established biomarkers such as the genotype, htTKV, MIC, PROPKD score, and BMI to predict disease progression. Some biomarkers, such as PKD genotype or genotype-based scores, perform very well at a population level but might lack granular prediction at an individual level. In contrast, other biomarkers like BMI only partially contribute to disease progression prediction and fail to capture the complexity of interactions among all factors that could modify the PKD phenotype and severity. Imaging biomarkers are the most effective in predicting disease severity and progression, as they reflect the cumulative impact of genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors. This can be assessed through measurements such as TKV, TCN, and CPSA. Nevertheless, it is crucial to adjust these biomarkers for age, as a htTKV of 1000 ml/m at a younger age is associated with a worse prognosis than the same htTKV at an older age. Similarly, assessing the cystic burden pattern provides additional information on atypical PKD features, enhancing prognosis accuracy. For example, a large htTKV in ADPKD-IFT140 with fewer cysts may indicate a better overall prognosis compared to someone with a similar htTKV but a PKD1 pathogenic variant. Currently, the MIC, which accounts for typical and atypical presentations and adjusts htTKV for age, performs the best as a single biomarker. However, there is potential to improve individualized prediction accuracy by combining several biomarkers including imaging, clinical and genotypic data into a more granular scoring system, leading to more accurate predictions of KF onset.

A major gap in the field is the lack of tools to assess the efficacy of disease-modifying treatments at an individual level. Response biomarkers would be valuable in assessing disease activity in response to an intervention and for further individualizing treatment by tailoring the dose or drug class to prescribe to patients and assessing efficacy on an individual level, given the high phenotypic variability. An example is urinary polycystin levels in urinary exosome-like vesicles. Ideally, each disease-modifying treatment (or class) will have specific biomarkers for assessing biological activity. Slowing ADPKD and modifying its trajectory might require addressing the pathophysiology from 2 or 3 different angles. Therefore, it is foreseeable to combine treatments and have various combinations of treatments, as well as a panel of response biomarkers and a comprehensive multi-score system for prognostic and predictive biomarkers. Of note, the biomarkers detailed in this review are mostly classified as prognostic biomarkers based on the definition of biomarkers, endpoints, and other tools biomarkers from National Institutes of Health and Food and Drug Administration, as these biomarkers are used to identify the likelihood of a clinical event, disease recurrence or progression in patients who have the disease of interest.13 To date, the only biomarker qualified by regulatory agencies (both Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency) is TKV.

It is also noteworthy to acknowledge that many associations between biomarkers and disease progression are derived from observational studies, which inherently limit the ability to establish causality. Even though these associations highlight potential indicators of disease progression, they should not be interpreted as definitive pathogenic processes. The distinction between association and causality underscores the need for further validation through prospective studies and randomized controlled trials to confirm causative relationships. In addition to validation, challenges in biomarkers include standardization, reproducibility, and improved access for general use. As new biomarkers are discovered and validated, enhancing reproducibility and accessibility will increase their clinical utility.

Future research should prioritize the development of combined scoring systems to enhance prediction accuracy and include early-stage and pediatric ADPKD patients to refine treatment strategies and improve patient outcomes. Innovations in imaging technologies, combined with artificial intelligence models for cyst segmentation, and the integration of molecular biomarkers—such as serum copeptin, urinary metabolites, urinary markers, and urinary exosomes—show significant potential to advance our understanding and management of ADPKD. To fully leverage these biomarkers, continuous validation, incorporation of novel biomarkers, and expanded application across diverse patient populations are essential.

Disclosure

PH receives grants from Espervita, Navitor, Acceleron, Jemincare, and Regulus, receives royalties from Bayer, Sanofi, Vertex, Mitobridge, Maze Therapeutics, Calico Life Sciences, and is a consultant for Vertex, Mitobridge, Regulus, Otsuka, Janssen, Maze Therapeutics, Caraway Therapeutics, Renasant, Sen Therapeutics, and PYC Therapeutics. PG receives speaking fees from Otsuka. ND is a consultant for Otsuka, on the advisory board of Natera and the PKD Foundation. FC has received research support from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Natera Inc., and Regulus, and an educational fellowship grant from Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. All the other authors declared no competing interests. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Grantham J., Cowley B.J., Torres V.E. Progression of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) to renal failure. Kidney Physiol Pathophysiol. 2000;2:2513–2536. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chebib F.T., Torres V.E. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: core curriculum 2016. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:792–810. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters D.J., Sandkuijl L.A. Genetic heterogeneity of polycystic kidney disease in Europe. Contrib Nephrol. 1992;97:128–139. doi: 10.1159/000421651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobin A., Kimberling W.J., Pettinger W., Bailey-Wilson J.E., Shugart Y.Y., Gabow P. Segregation analysis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Genet Epidemiol. 1993;10:189–200. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang A.R., Moore B.S., Luo J.Z., et al. Exome sequencing of a clinical population for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. JAMA. 2022;328:2412–2421. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.22847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porath B., Gainullin V.G., Cornec-Le Gall E., et al. Mutations in GANAB, encoding the glucosidase IIα subunit, cause autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:1193–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claus L.R., Chen C., Stallworth J., et al. Certain heterozygous variants in the kinase domain of the serine/threonine kinase NEK8 can cause an autosomal dominant form of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2023;104:995–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grantham J.J., Cook L.T., Wetzel L.H., Cadnapaphornchai M.A., Bae K.T. Evidence of extraordinary growth in the progressive enlargement of renal cysts. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:889–896. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00550110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grantham J.J., Torres V.E., Chapman A.B., et al. Volume progression in polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2122–2130. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa054341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franz K.A., Reubi F.C. Rate of functional deterioration in polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1983;23:526–529. doi: 10.1038/ki.1983.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chebib F.T., Torres V.E. Assessing risk of rapid progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and special considerations for disease-modifying therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78:282–292. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chebib F.T., Perrone R.D. Drug development in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: opportunities and challenges. Adv Kidney Dis Health. 2023;30:261–284. doi: 10.1053/j.akdh.2023.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Library of Biomarkers BEST (Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools) Resource. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326791/

- 14.Amur S., LaVange L., Zineh I., Buckman-Garner S., Woodcock J. Biomarker qualification: toward a multiple stakeholder framework for biomarker development, regulatory acceptance, and utilization. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;98:34–46. doi: 10.1002/cpt.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Food and Drug Administration Qualification of biomarker total kidney volume in studies for treatment of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease draft guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/qualification-biomarker-total-kidney-volume-studies-treatment-autosomal-dominant-polycystic-kidney

- 16.US Food and Drug Administration Biomarker Qualification Program. FDA. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-development-tool-ddt-qualification-programs/biomarker-qualification-program

- 17.European Medicines Agency Opinions and letters of support on the qualification of novel methodologies for medicine development. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/research-development/scientific-advice-protocol-assistance/opinions-letters-support-qualification-novel-methodologies-medicine-development

- 18.Müller R.U., Messchendorp A.L., Birn H., et al. An update on the use of tolvaptan for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: consensus statement on behalf of the ERA Working Group on Inherited Kidney Disorders, the European Rare Kidney Disease Reference Network and Polycystic Kidney Disease International. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37:825–839. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfab312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chebib F.T., Perrone R.D., Chapman A.B., et al. A practical guide for treatment of rapidly progressive ADPKD with tolvaptan. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:2458–2470. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018060590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gall E.C.L., Gall E.C.L., Audrézet M.P., et al. The PROPKD score: a new algorithm to predict renal survival in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:942–951. doi: 10.1681/asn.2015010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavu S., Vaughan L.E., Senum S.R., et al. The value of genotypic and imaging information to predict functional and structural outcomes in ADPKD. JCI Insight. 2020;5 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.138724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman A.B., Bost J.E., Torres V.E., et al. Kidney volume and functional outcomes in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:479–486. doi: 10.2215/cjn.09500911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shukoor S.S., Vaughan L.E., Edwards M.E., et al. Characteristics of patients with end-stage kidney disease in ADPKD. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;6:755–767. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L.C., Chu Y.C., Lu T., Lin H.Y.H., Chan T.C. Cardiometabolic comorbidities in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a 16-year retrospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2023;24:333. doi: 10.1186/s12882-023-03382-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith L.A., Bukanov N.O., Husson H., et al. Development of polycystic kidney disease in juvenile cystic kidney mice: insights into pathogenesis, ciliary abnormalities, and common features with human disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2821–2831. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]