Abstract

Introduction

Despite the establishment of a national strategy and plan to eliminate all harmful traditional practices, traditional uvulectomy remains widely practiced in Ethiopia, and there is a lack of comprehensive summary of national data on uvulectomy complications and associated malpractices. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the pooled complications of uvulectomy and concurrent occurrences of traditional malpractices in Ethiopia.

Methods

The following databases were used to retrieve studies: PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Google Scholar, Web of Science, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, SCOPUS, and Google Search. Manual searches were also utilized to identify relevant articles. Studies reporting traditional uvulectomy complications and malpractices in Ethiopia were considered. STATA Version 17 was utilized for statistical analyses, while heterogeneity and publication bias were assessed using I2 statistics.

Results

From a total of 259 studies found in electronic databases, 19 studies (23,559 study participants) were incorporated in the analysis. The pooled incidence of complications following traditional uvulectomy in Ethiopia was 29 % (95 % CI: 14%–44 %). Hemorrhage, transmission of communicable infections, and sepsis are the most common complications of traditional uvulectomy. Concurrent to uvulectomy female genital cutting (23 %), milk tooth extraction (29 %), bloodletting (“mebtat” in Amharic) (11 %), eyebrow incision (10 %), and body tattooing (16 %) were found to be widely practiced in Ethiopia.

Conclusions

The overall pooled results of this study revealed that three out of ten children who underwent traditional uvulectomy experienced complications such as hemorrhage, the spread of contagious infections, and sepsis. Children underwent uvulectomy are also victim to other traditional malpractices including milk teeth extraction, bloodletting, eyebrow incision, tonsillectomy, and body tattooing. Efforts should be made to update strategies to avert malpractices through awareness-creation, social mobilization, and controlling traditional practitioners.

Keywords: Uvulectomy, Traditional/cultural malpractices, Concurrent occurrence, Ethiopia

1. Introduction

Traditional uvulectomy is a potentially dangerous surgical procedure involves removing part or all of the uvula by traditional healers [1,2]. It is performed as part of local cultural beliefs usually among under-five children, and entails surgical resection of the uvula traditionally. The procedure includes pulling the tongue, with a string and then cutting it with a sharp object. This often uses unsterile materials and can lead to serious immediate and delayed complications. In Africa, neonatal uvulectomy by traditional practitioners has been an age-long practice [[3], [4], [5]]. Harmful traditional practice was deeply rooted in the community; more than 80 % of Middle East and European immigrants residents, still participated in this practice [6].

Different traditional malpractices are practiced (concurrently with uvulectomy) in Africa including Ethiopia. Female genital cutting is widely performed in Ethiopia and has a significant association with birth complications [[7], [8], [9], [10]]. Similarly, milk tooth extraction [11], eyebrow incision with uvula cutting [6] and bloodletting [12] were among some of the cultural malpractice in Ethiopia.

Even though it has varieties of complications traditional uvulectomy is still practiced in different African countries like Uganda [13], Tanzania [14], Kenya [15], Sudan [16], Cameroon [17], and others. The reasons for uvula removal in many African countries vary, but it is generally believed to cure various diseases by the community and traditional practitioners.

Uvulectomy is a dangerous harmful custom that have various complications among Ethiopian communities. The procedure lacks sterile technique and results in short and long-term complications like excessive bleeding, infections, the transmission of infectious disease, anemia, tetanus meningitis, and death [[18], [19], [20], [21], [22]]. Similarly, hospital admission secondary to sepsis and anemia after uvulectomy was a common problem in Ethiopia [23]. Additionally, acute malnutrition, human immune deficiency (HIV) infections, septicemia, dental complications, torticollis, difficulty swallowing, and obstructive sleep apnoea (secondary to palatal stenosis) were among commonly reported complications [[24], [25], [26], [27]].

Ethiopia has implemented a national strategy to put an end to all harmful malpractices, like uvulectomy, by 2025 [28]. This practice has been associated with various complications, and therefore, the country has made significant efforts to raise awareness about its negative consequences. Health education campaigns have been launched, and community mobilization efforts are underway to increase awareness among social help providers such as “Shengo” and religion front-runners, and malpractitioners. These efforts will attract customers and enhance service provision capacity, which is essential in achieving the national plan [[28], [29], [30]].

Despite those efforts, traditional uvulectomy is still widely practiced in Ethiopia [31]. There are different study reports on complications of uvulectomy and co-occurrences of other traditional malpractices in Ethiopia. A national summary of evidence that indicates the burden of uvulectomy complications and concurrent occurrences is needed to provide the reader with up-to-date information and support for those who are interested in tackling these traditional practices. Consequently, the study assessed the pooled traditional uvulectomy complications and concurrent occurrences of malpractices within Ethiopia. It sheds light on health implications and enriches the understanding of cultural traditions, ethics in healthcare, and global health discourse.

2. Methods

2.1. Study protocol and registration

The following steps were taken to conduct this systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA): initially, articles has been searched, then the titles and abstracts were assessed, and finally, full texts were evaluated to determine if they are eligible. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guideline were followed [32] [Supplementary File 1]. Additionally, the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) criteria were applied to present the findings [33]. Registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023459734).

2.2. Inclusion of the studies

Ethiopian studies that reported the complications of traditional uvulectomy and/or co-occurrence of traditional malpractices were considered. This SRMA includes observational researchs, including cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies, that investigate the complications of uvulectomy and/or concurrent malpractices. The articles considered in this review were published in Ethiopia and available until June 1, 2023, and were written in English. The search for articles took place between August 20 and August 31, 2023. Note that this review does not include case series/reports, editorials, reviews, commentaries, or experimental investigations.

2.3. Study searching strategies

The systematic review and meta-analysis utilizes several databases including PubMed, EMBASE, CINHAL (EBSCO), Google Scholar, Web of Sciences, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, SCOPUS, and Google search. Boolean logic operators (AND, OR, NOT), Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and keywords were utilized to locate articles. Searching terms “Complications/risk” AND “Uvulectomy/uvula cutting” AND “co-occurrence/concurrent occurrences” AND “traditional practices/malpractices” AND “Ethiopia” were used to retrieve relevant articles.

Advanced PubMed searches utilize (((((((((((Uvulectomy) OR (“traditional uvulectomy")) OR (“Uvula cutting")) OR (“Uvula removal")) AND (Complications)) OR (Risks) AND (“Co-occurrence")) OR (“Concurrent occurrences")) AND (malpractices)) OR (“traditional malpractices")) OR (“Cultural malpractices")) AND (Ethiopia). The detail comprehensive searchs is located under “Supplementary File 2."

2.4. Study selection

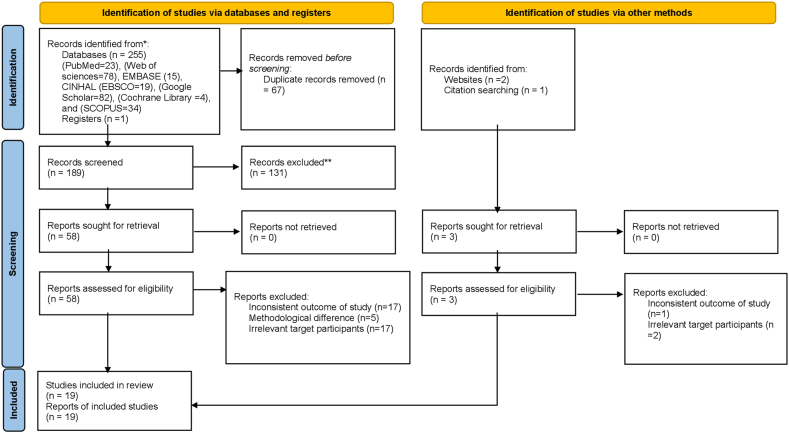

EndNote X8 was mainly used to merge database search results and eliminate duplicates. However, some references were manually managed owing to variations in citation styles across various sources. Afterward, 3 authors (TG, AE, and AN) individually went through the titles and abstracts of the papers. The other two authors (SM and AC) examined the full texts and independently analyzed each study considering its objectives, research design, population, and primary outcomes. The main objective was to assess the complications of traditional uvulectomy and the occurrence of concurrent traditional malpractices in Ethiopia. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the entire study selection process (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA statement flow diagram that display the study selection procedure.

2.5. Abstraction of data

Following the identification of relevant articles, TG and AN extracted the data independently. They used a pre-defined Microsoft Excel 2016 sheet with headings: authors and study year, setting, area, design of study, sample size, the main outcome (complications of uvulectomy), and concurrent occurrences of other traditional malpractices to extract data from the selected papers. Quantitative data, including total sample size (N), frequency of occurrence (n), and effect size, were compiled using Microsoft Excel 2016. These data were taken from the included papers and used for pooled-analysis.

2.6. Study outcome

Complications arising from traditional uvulectomy procedures were the main results for the given SRMA, with secondary finding being the co-occurrence of traditional malpractices in Ethiopia.

2.7. Risk of bias

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), the tool for assessment of quality was utilized and assessed the likelihood of bias in observational studies [34]. To minimize potential bias, comprehensive searches through manual and electronic/database searches, such as published/unpublished and institutional/community-based research were conducted. We authors collaborated to establish a timetable for selecting studies as per specific aims and suitability requirements, assessing quality of studies, routinely assessing review procedure, and gathering and extracting the data.

2.8. Methodological quality (risk bias) assessment

The JBI methodology was used to evaluate the quality of the research methods and findings in the selected observational studies, including cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort studies [34] [Supplementary file 3]. Two independent groups of authors, TG and AN, and AE and SM, evaluated the quality of the studies. The final decision on study inclusion was based on the average score of the two groups. If there were disagreements about including a study, they were resolved through discussion. The studies were assessed against each criterion of the quality assessment tool and categorized as high, moderate, or low quality. A score above 80 % was considered high quality, while a score between 60 % and 80 % was considered moderate quality, and a score below 60 % was considered low quality. Only studies with a score of 60 % or higher were included in the analysis. The purpose of this quality assessment was to evaluate the internal validity (systematic error) and external validity (generalizability) of the studies and to minimize the risk of bias.

2.9. Statistical analysis and publication bias

STATA 17 software was used to synthesize data and conduct statistical analyses. The results of meta analysis, which were accustomed demonstrate the complications of uvulectomy and co-occurrences of traditional malpractices, were showed by forest plots. To reduce heterogeneity among the incorporated studies, a random effects model was utilized. Additionally, The data were analyzed by subgroups defined by different study variables including study settings, study environment (community-settings/facility-based), and years of publications. Finally, Meta-regression analysis was performed to explore heterogeneity sources.

A systematic synthesis of observational evidence was undertaken utilizing Higgins et al.'s I2 statistic. If the I2 value was equal to or higher than 75/100 %, it indicated significant heterogeneity. A funnel plot and Egger's regression test were used to assess publication bias. Asymmetry in the funnel plot and/or a statistically significant Egger's regression test (P < 0.05) indicated the presence of publication bias. The results of the included studies were initially summarized narratively, followed by a meta-analysis chart.

3. Results

3.1. Screening flow

After conducting various source searches, totally 259 studies were identified through extensive searchs, from different data sources. However, 67 of these were removed as duplicates. The rest 192 publications were filtered using study title and summaries. From these, 131 studies have been excluded, with 58 being rejected based on their titles, 69 after reviewing their abstracts, and 4 not conducted in Ethiopia. Other, 42 papers were also excluded (inconsistent outcome of study (n = 18), methodological difference (n = 5), irrelevant target participants (n = 19)). Ultimately, 19 publications fulfilled an inclusion standards and were retained for inclusion in the review (Fig. 1).

3.2. Characteristics of the studies

This meta-analysis and systematic review included 19 papers with a total of 23559 study participants [6,21,23,30,[35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49]], of which 11354 children underwent uvulectomy. Nearly fifty percent of the research studies included in this review were carried out in the Amhara [21,23,30,35,37,39,40,43,49], followed by Tigray (21 %) [6,38,41,42], Oromia (10 %) [36,45], and Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Regional state (SNNPR) regions (10 %) [44,46]. The remaining 10 % of studies were national [47,48]. Except for one study which had a prospective cohort design, all others were cross-sectional [46]. In review, half of the investigations were carried out in hospital settings, and the other half were conducted in community settings. One study was carried out in a community and an institutional context. A summary of the key characteristics of the papers that were chosen for this review is found in Table 1.

Table 1.

General characteristics of included studies that reported complications of traditional uvulectomy and co-occurrences of traditional malpractices in Ethiopia.

| Author, Year | Region | Setting | Study design | sample size | Prevalence | Complications of traditional Uvulectomy | Co-occurrences of other traditional malpractices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abera B, 2014 | Amhara | Hospital based | cross-sectional | 253 | 21 | Transmission of communicable infections (HIV, Hep B) | Female genital cutting (FGC): (20.8 %) of the children who had had uvulectomy were also victim for FGC) |

| Addis G, 2002 | Oromia | Institution and community based | cross-sectional | 80 | 37.5 | NR | Concurrent to traditional uvulectomy, other malpractices like FGC (55 %), Milk tooth extraction(32 %), bloodletting/mebtat (7.5 %) were also practiced |

| Bayih A, 2020 | Amhara | Institution-based | cross sectional | 422 | 15.9 | Transmission of communicable infections (HIV, Hep B), Hemorrhage, wound infection, fever, difficulty of breathing, and Tetanus | NR |

| Dagnew M, 1990 | Amhara | Institution-based | cross-sectional | 853 | 85.7 | wound infection, fever, difficulty of breathing, and Tetanus | Milk -teeth extraction (70.2 %), Eyelid incision (19.2 %), Female circumcision (6.1 %) |

| Gebrekirstos K, 2014 | Tigray | Community based | cross sectional | 752 | 86.9 | Wound infection, fever, difficulty of breathing, and Tetanus | Milk teeth extraction (12.5 %), eye borrows incision (2.4 %), FGM (0.7 %), bloodletting (2.13 %) |

| Gebrekirstos K, 2014 | Tigray | Community based | cross sectional | 752 | 72.9 | Hemorrhage, wound infection, fever, difficulty of breathing, and Tetanus | Milk teeth extraction (11.8 %), eye borrows incision (2.3 %), FGM (0.7 %), bloodletting (2.13 %) |

| Gedefaw G, 2019 | Amhara | Institution-based | cross-sectional | 338 | 28.7 | Transmission of communicable infections (HIV, Hep B) | NR |

| Kiflu G, 2014 | Amhara | Community based | cross-sectional | 503 | 22.9 | NR | Milk teeth extraction (10.9 %), FGC 3 (1.3 %) |

| Getu D, 2010 | Amhara | Community based | cross-sectional | 1747 | 89 | NR | Milk-teeth extraction (58.2), Eyebrow incision (16.7 %), bloodletting (2.3 %), FGC (4.3 %), Tonsillectomy (20 %) |

| Hadush A, 2016 | Tigray | Institution-based | cross-sectional | 290 | 20 | NR | NR |

| Hailu A, 2019 | Tigray | Community based | cross-sectional | 1298 | 71.6 | NR | NR |

| Kebede K, 2017 | Amhara | Community based | cross-sectional | 456 | 23.7 | Hemorrhage, wound infection, fever, difficulty of breathing, and Tetanus | NR |

| Kefelew E, 2023 | SNNPR | Institution-based | cross-sectional | 402 | 36.6 | wound infection, fever, difficulty of breathing, and Tetanus | NR |

| Mamuye B, 2020 | Oromia | Institution-based | cross-sectional | 363 | 12.4 | Transmission of communicable infections (HIV, Hep B) | FGC (77.1 %), Body tattooing (5.7 %) |

| Medhin G, 2010 | SNNPR | Community based | prospective Cohort | 1799 | 4.8 | NR | FGC (1.5 %), milk teeth extraction (3.9 %) |

| Mitke Y, 2010 | National | Institution-based | cross-sectional | 1163 | 19.9 | Transmission of communicable infections (HIV, Hep B) | Milk tooth extractions (16 %), tonsillectomy (11.6 %) |

| Sentjens R, 2002 | National | Institution based | cross-sectional | 4830 | 42.2 | Transmission of communicable infections (HIV, Hep B) | Eye brow incision (11.5 %), FGC (91.7 %), Tattooing (22.1 %) |

| Tadesse T, 2011 | Amhara | Community based | cross-sectional | 6624 | 85.5 | NR | Milk teeth extraction (42.3 %), tattooing (21.5 %), and FGC (1.1 %) |

| Yirdaw B, 2022 | Amhara | Community based | cross-sectional | 634 | 52.5 | wound infection, fever, difficulty of breathing, and Tetanus | NR |

∗ AOR = adjusted odds ratio, NR: not reported, SNNPR = southern nations, nationalities and peoples region.

3.3. Complications of traditional uvulectomy

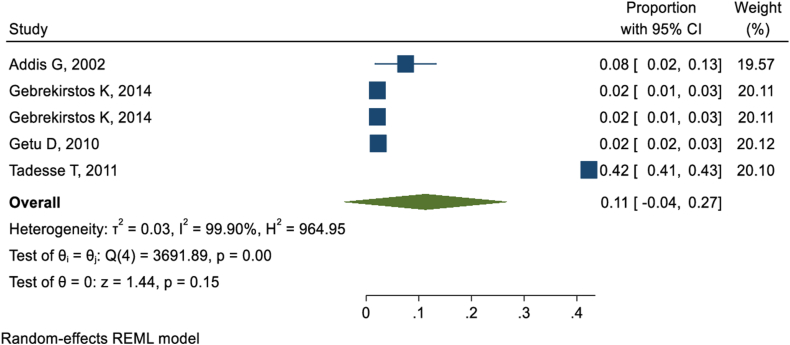

A meta-analysis found the overall prevalence of uvulectomy/uvula cutting in Ethiopia found to be 44 %. For a comprehensive understanding of the pooled prevalence and associated factors, please refer to Ref. [31]. Of nineteen studies reported about traditional practices in Ethiopia ten of them reported the complications of traditional uvulectomy. Based on those ten studies [21,23,30,35,37,[43], [44], [45],47,48], the pooled incidence of complications following traditional uvulectomy in Ethiopia was 29 % (95 % CI: 14%–44 %). Hemorrhage as a complication of traditional uvulectomy was reported by three studies [23,38,43]. The pooled incidence of hemorrhage was 31 % (95 % CI: 5%–68 %). Six studies [21,23,35,45,47,48] reported that traditional uvulectomy risked victims to communicable infections like HIV and Hepatitis virus mainly through contaminated devices used for this procedure. The Pooled result revealed that 23 % (95 % CI: 1%–44 %) of victims encountered communicable infections including HIV and Hepatitis virus. The pooled result from other six studies [6,23,30,37,43,44] also revealed that 34 % (95 % CI: 5%–62 %) of children exposed to traditional uvulectomy developed one or more complications like wound infection, fever, difficulty of breathing, and tetanus (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Systematic and Meta-analysis review showing complications of traditional uvulectomy in Ethiopia.

3.4. Concurrent traditional malpractices

3.4.1. Female genital cutting (FGC)

Traditional malpractices are mostly practiced simultaneously. A total of twelve studies [6,[35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40],[45], [46], [47], [48], [49]] reported that FGC was practiced concurrently with traditional uvulectomy. The pooled prevalence of FGC among participants who were victims of traditional uvulectomy was 23 % (95 % CI: 4%–41 %) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of FGC prevalence in individuals with a history of traditional uvulectomy, visualized in a forest plot.

3.4.2. Milk tooth extraction

Nine studies [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40],46,47,49,50] revealed that milk tooth extraction was practiced concurrently with traditional uvulectomy in Ethiopia. The pooled concurrent practice of milk tooth extraction in Ethiopia was found to be 29 % (95 % CI: 13%–44 %) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest-plot presentation of magnitude of milk tooth extraction concurrent to traditional uvulectomy.

3.4.3. Bleeding/bloodletting (mebtat in Amharic)

Bloodletting, what we call “mebtata” in Amharic, was also practiced simultaneously among victims of traditional uvulectomy as reported by five studies [6,36,38,40,49] conducted on traditional uvulectomy. Thus, the pooled prevalence of bloodletting/bleeding practice among those who encountered traditional uvulectomy/uvula cutting was 11 % (95 % CI: 11%–27 %) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Forest-plot indicating magnitude of bloodletting practice concurrent to traditional uvulectomy.

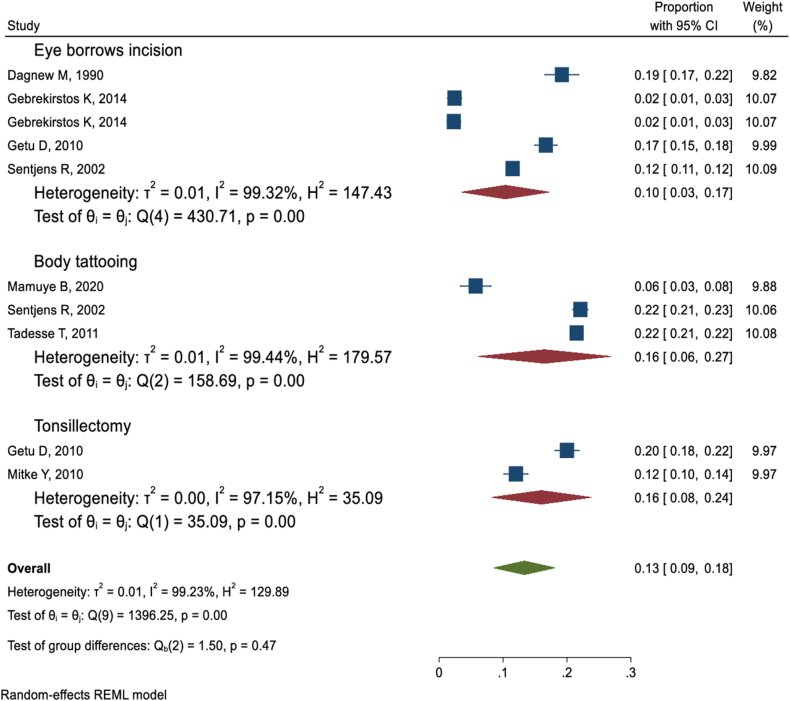

3.4.4. Eyebrow incision, tattooing, and tonsillectomy

Simultaneous to traditional uvulectomy other traditional malpractices including eyebrow incision, body tattooing, and tonsillectomy were reported by five [6,37,38,40,48], three [45,48,49], and two [40,47] studies, respectively. The pooled prevalence of eyebrow incision, body tattooing, and tonsillectomy among those who were victims of traditional uvulectomy was 10 % (95 % CI: 3%–17 %), 16 % (95 % CI: 6%–27 %), and 16 % (95 % CI: 8%–24 %), respectively (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of factors associated with uvulectomy.

3.5. Factors driving uvulectomy practice in Ethiopia

Seven studies [6,30,38,39,43,44,47] conveyed the primary reasons why mothers opt for a traditional uvulectomy. These studies involved 4662 mothers, out of which 2136 mothers gave one or more reasons related to uvulectomy. The commonly cited reasons include preventing uvula swelling, pus, and rapture [6,38,39,43], improving medical treatment [30,38], avoiding sore throats [30,47], avoiding coughs [43,47], due to religious beliefs [43], and pressure from traditional practitioners [44,47]. It was commonly believed that a uvulectomy was necessary for infants who could not eat, exhibited an abnormal presentation of the anterior fontanel, spoke harshly, salivated excessively, and feared tonsil/uvula rupture [47]. Additional reasons mentioned by participants were prior success, fever, coughing, sneezing, and fatigue [43,44,47].

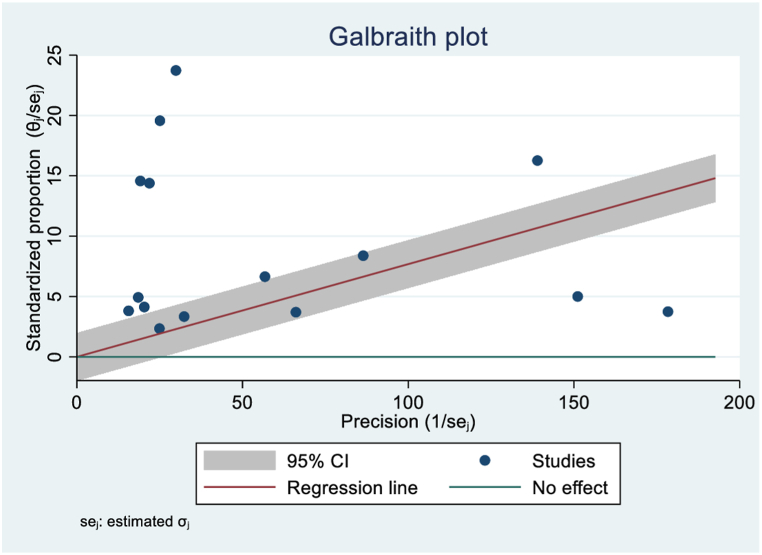

3.6. Heterogeneity and publications biases

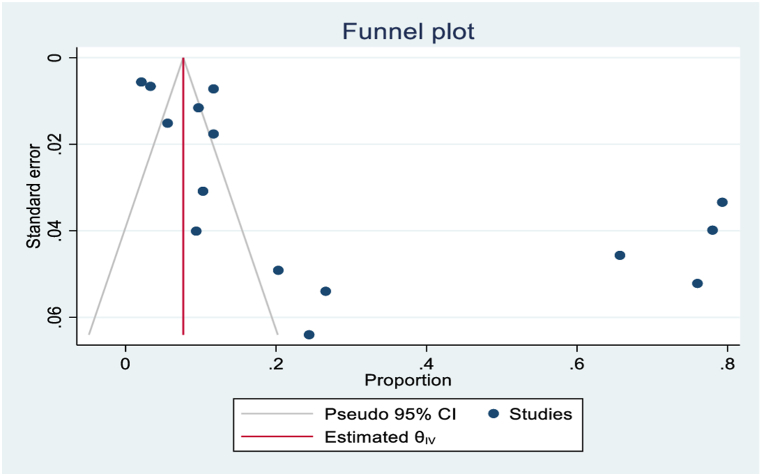

To evaluate potential publication bias in the included studies, funnel plots and Egger's tests were conducted at a 5 % significance level, accounting for heterogeneity. Moreover, Galbraith plots were used to identify heterogeneity sources based on factors including sample size and publication year (Fig. 7). The presence of publication bias was confirmed by Egger's test suggesting that studies with non-significant or negative results may have been underreported, as shown by ‘Fig. 8’ asymmetric funnel plot. Random-effects sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the influence of individual studies on the overall pooled outcome. However, these analyses did not reveal substantial evidence of such an impact.

Fig. 7.

Visualization of study heterogeneity.

Fig. 8.

Funnel diagram/plot reviewed articles.

4. Discussion

Traditional/cultural uvulectomy/uvula cutting is a longstanding tradition in Africa, with different views regarding the reasons and its benefits [23,51]. However, one of the national plans to avert deaths of newborns and under 5 children is eradicating traditional malpractices and their complications by 2025 [52]. The 2025 national strategy aims to address harmful traditional practices (HTPs), through awareness raising, establishing and updating of practitioners' registry, informing them about relevant laws, and providing training and encouraging these practitioners to become change agents, engaging community leaders, and taking legal measures against those who continue to practice secretly. This comprehensive approach aims to reduce HTPs and promote safer, lawful practices within the community.

Traditional uvulectomy is a common and hazardous procedure that poses a significant life-threatening consequence to children in Ethiopia. This study investigated the incidence of different complications following traditional uvulectomy and the co-occurrence of uvulectomy with many other traditional malpractices. Consequently, the pooled incidence of uvulectomy complications in Ethiopia was found to be 29 % (95 % CI: 14%–44 %). The summary estimate of this study revealed that hemorrhage (31 %), transmission of communicable infections including HIV and Hepatitis virus (23 %), and sepsis (34 %) are the most common complications of traditional uvulectomy mainly due to the use of unsterile instruments and exposure to blood. Traditional practitioners often lack infection control knowledge, and protective measures are rarely used. Cultural beliefs and limited healthcare access perpetuate these practices. Education, safer practices, and training in hygiene are essential to reduce these risks.

This review, pooled estimate of hemorrhage following uvulectomy/uvula cutting found to be 31 % (95 % CI: 5%–68 %). Similarly, hemorrhage as a complication of uvulectomy has also been reported in Nigeria [53] and Tanzania [54]. This finding implied that despite the efforts of non-governmental and governmental organizations in increasing access to health care, dissemination of information about harmful traditional practices, and setting legal actions for those who perform, traditional uvulectomies remain widespread and prevalent. This indicated that there is a need to design an innovative approach that can lessen the impact of uvulectomy and its consequences. Furthermore, to save the lives of those children, there should be a system which aware of those complications and can give prompt treatment, especially in the area where traditional uvulectomy is prevalent.

In this SRMA study, the overall estimate of sepsis following uvulectomy was 34 % (95 % CI: 5%–62 %). Study in Nigeria also have documented cases of sepsis following traditional uvulectomy [55]. Sepsis occurred mainly due to the materials used for cutting of uvula were sterile. Research done in Uganda indicated that sharp blade wetlands, strings, electrical lines, reaper blades, and utensils are among the instruments used to cut uvula [56]. This result still indicated that traditional uvulectomy poses significant consequences for the children. Therefore, it is necessary to amend strategies to combat the traditional harmful practices even if it is necessary to formulate a strong rule and regulations for those practitioners and families.

This study revealed that the pooled co-occurrence of female genital cutting (FGC) and traditional uvulectomy was 23 % (95 % CI: 4%–41 %). A study conducted in Nigeria similarly reported that children suffered from both uvulectomy and FGC [57]. Female genital circumcision is a common traditional malpractice in Ethiopia which is usually performed with other traditional malpractices like uvulectomy. Evidence shows that the rate of FGC in Ethiopia is from 14 to 24 % [52]. Women who cut their female genitalia suffer physical health consequences for the rest of their lives, starting when they cut as babies and continuing through adult sexuality and motherhood. Therefore, the concerned bodies should strive hard to keep those children from the unwanted consequences of those traditional malpractices.

Similarly, the pooled estimate discovered traditional malpractices including milk tooth extraction (29 %), bloodletting (“mebtata” in Amharic) (11 %), eyebrow incision (10 %), and body tattooing (16 %) were widely practiced concurrently with traditional uvulectomy in Ethiopia. This indicates that if the current situation continues, Ethiopia will not be able to achieve its national goal of eliminating all traditional harmful practices by 2025 [52].

4.1. Implication

This review is pioneering to provide a thorough evaluation of the risks and co-occurrences of typical malpractices associated with uvulectomy. The data gathered from this review is helpful for healthcare practitioners, government decision-makers, and other organizations committed to improving children's health by providing a national summary estimate of the prevalences of complications following cultural uvulectomy/uvula cutting and co-occurrences of malpractices. It can help translate health-related evidence, support informed decision-making, and compile a summary of data into a single document.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

Among the notable strengths of this review are use of multiple databases for manual and electronic article searches to prepare for meta-analyses. It also used a predetermined and validated standard format for uniform information abstraction. This format was reviewed by two separate reviewers to reduce errors. Moreover, papers from different regions of the country with both urban and rural populations were included in this meta-analysis. As a limitation: When applying the review's findings, it is important to keep in mind that the high degree of heterogeneity among the included studies may have resulted in inadequate power to identify statistically significant relationships.

5. Conclusions

Complications of traditional uvulectomy and concurrent malpractices pose significant consequences for the children. The pooled results of this SRMA revealed that three out of ten children who underwent this procedure experienced complications such as hemorrhage, the spread of contagious infections, and sepsis. In addition to uvulectomy, concurrently performed traditional practices on Ethiopian children include extraction of milk teeth, bloodletting (known as “mebtat” in Amharic), eyebrow incision, tonsillectomy, and body tattooing. Therefore, it is necessary to establish strict policies and requirements for traditional practitioners and families too. Additionally, implementing education campaigns to inform communities about the risks of traditional malpractices and the benefits of modern medicine. Establish and update a registry of practitioners, enforce laws against harmful practices, and provide alternative employment training. Engaging community leaders as change agents and developing support systems like health clinics are recommended.

Ethical considerations

In this study, no ethical approval was needed as the study was based on data extracted from published studies.

Funding statements

None.

Data availability statements

The data associated with this review can be found in the results section/supplementary materials/referenced articles.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tamirat Getachew: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Abraham Negash: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Sinetibeb Mesfin Kebede: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Data curation. Abera Cheru: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation. Addis Eyeberu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Abera Kenay Tura: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no any competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Our gratitude is extended to the authors of the primary studies cited in this review.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38978.

Contributor Information

Tamirat Getachew, Email: tamirget@gmail.com.

Abraham Negash, Email: harmee121@gmail.com.

Sinetibeb Mesfin Kebede, Email: sine3686@gmail.com.

Abera Cheru, Email: cheruabex@gmail.com.

Addis Eyeberu, Email: addiseyeberu@gmail.com.

Abera Kenay Tura, Email: daberaf@gmail.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Prual A., et al. Traditional uvulectomy in Niger: a public health problem? Soc. Sci. Med. 1994;39(8):1077–1082. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owibingire S.S., Kamya E.R., Sohal K.S. Beliefs about traditional uvulectomy and teething: awareness and perception among adults in Tanzanian rural setting. Ann. Int. Med. Dent. Res. 2018;4(2):25. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olajide G.T., Olajuyin O.A., Adegbiji W.A. Traditional uvulectomy: origin, perception, burden, and strategies of prevention. International Journal of Medical Reviews and Case Reports. 2018:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aaba A. National strategy and action plan on harmful traditional practices (HTPs) against women and children in Ethiopia federal democratic republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Women (MoWCYA) Children and Youth Affairs. 2013:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isa A., et al. Parental reasons and perception of traditional uvulectomy in children. Sahel Med. J. 2011;14(4):210. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gebrekirstos K., Fantahun A., Buruh G. Magnitude and reasons for harmful traditional practices among children less than 5 Years of age in axum town, north Ethiopia, 2013. Int. J. Pediatr. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/169795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gebremariam K., Assefa D., Weldegebreal F. Prevalence and associated factors of female genital cutting among young adult females in Jigjiga district, eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional mixed study. Int. J. Wom. Health. 2016:357–365. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S111091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abebe S., et al. Prevalence and barriers to ending female genital cutting: the case of Afar and Amhara Regions of Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(21):7960. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yosef Y., Borsamo A., Abeje S. vol. 11. SAGE open medicine; 2023. (Assessment of Complications Associated with Female Genital Cutting Among Postnatal Women in Chuko Primary Hospital, Sidama Region, Southern Ethiopia). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yismaw A.E., et al. Spatial distribution and associated factors of female genital cutting among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia: further analysis of EDHS 2016. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health. 2021;12 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otayto K., et al. Prevalence of milk teeth extraction and enabling community factors among under five-year-old children in alle special woreda, SNNPR, Ethiopia, 2022: community-based cross-sectional study; based on theory of planned behavior model. Pediatr. Health Med. Therapeut. 2022;13:257–269. doi: 10.2147/PHMT.S365768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodes R. Cross-cultural medicine and diverse health beliefs. Ethiopians abroad. West. J. Med. 1997;166(1):29–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kibira S.P.S., et al. Uvula infections and traditional uvulectomy: beliefs and practices in Luwero district, central Uganda. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lange S., Mfaume D. The folk illness kimeo and "traditional" uvulectomy: an ethnomedical study of care seeking for children with cough and weakness in Dar es Salaam. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022;18(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s13002-022-00533-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe K.R. Severe anemia following uvulectomy in Kenya. Mil. Med. 2004;169(9):712. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.9.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miles S.H., Ololo H. Traditional surgeons in sub-Saharan Africa: images from South Sudan. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2003;14(8):505–508. doi: 10.1258/095646203767869057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Einterz E.M., Einterz R.M., Bates M.E. Traditional uvulectomy in northern Cameroon. Lancet. 1994;343(8913):1644. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Children’s N.Y.S.t., Protecting children from harmful practices in plural legal systems with a special emphasis on. Africa. 2012:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe K.R. Severe anemia following uvulectomy in Kenya. Mil. Med. 2004;169(9):712. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.9.712. 712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eregie C. Uvulectomy as an epidemiological factor in neonatal tetanus mortality:-observations from a cluster survey. W. Afr. J. Med. 1994;13(1):56–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gedefaw G., et al. Risk factors associated with hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at Felegehiwot referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2018: an institution based cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12(1):509. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4561-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adoga A.A., Nimkur T.L. The traditionally amputated uvula amongst Nigerians: still an ongoing practice. ISRN Otolaryngol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.5402/2011/704924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alebachew Bayih W., Minuye Birhan B., Yeshambel Alemu A. The burden of traditional neonatal uvulectomy among admissions to neonatal intensive care units, North Central Ethiopia, 2019: a triangulated crossectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mbusa Kambale R., et al. Traditional uvulectomy, a common practice in South Kivu in the democratic republic of Congo. Med Sante Trop. 2018;28(2):176–181. doi: 10.1684/mst.2018.0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston N.L., Riordan P.J. Tooth follicle extirpation and uvulectomy. Aust. Dent. J. 2005;50(4):267–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elyajouri A., et al. Grisel's syndrome: a rare complication following traditional uvulectomy. Pan African Medical Journal. 2015;20(1) doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.62.5930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravesloot M., De Vries N. ‘A good shepherd, but with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome’: traditional uvulectomy case series and literature review. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2011;125(9):982–986. doi: 10.1017/S0022215111001526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ethiopia T.F.D.R.o. National Strategy and Action Plan on Harmful Traditional Practices against Women and. Children. 2019:14–29. [Google Scholar]

- 29.UNICEF OPM. Child Well-Being in Ethiopia.Analysis of Child Poverty Using the HCE/ WMS 2011 Datasets. Addis Ababa. Ethiopia. 2015:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yirdaw B.W., Gobeza M.B., Tsegaye Gebreegziabher N. Practice and associated factors of traditional uvulectomy among caregivers having children less than 5 years old in South Gondar Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia, 2020. PLoS One. 2022;17(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Getachew T., et al. The burdens, associated factors, and reasons for traditional uvulectomy in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024;176 doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2023.111835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D., et al. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stroup D.F., et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porritt K., Gomersall J., Lockwood C. JBI's systematic reviews: study selection and critical appraisal. AJN The American Journal of Nursing. 2014;114(6):47–52. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000450430.97383.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abera B., et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C viruses and risk factors in HIV infected children at the Felgehiwot referral hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes. 2014;7:838. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Addis G., et al. Perceptions and practices of modern and traditional health practitioners about traditional medicine in Shirka District, Arsi Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2002;16(1):19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dagnew M.B., Damena M. Traditional child health practices in communities in north-west Ethiopia. Trop. Doct. 1990;20(1):40–41. doi: 10.1177/004947559002000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gebrekirstos K., Abebe M., Fantahun A. A cross-sectional study on factors associated with harmful traditional practices among children less than 5 years in Axum town, north Ethiopia, 2013. Reprod. Health. 2014;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Genet K., Solomon A., Melkie E. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of Fgm, uvulectomy, and extraction of canine milk teeth follicle among mothers of children under the age of one living in Gondar town. Ethiopian Journal of Health and Biomedical Sciences. 2014;6(1):3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Getu D.A. Harmful traditional health practices: a cross-sectional survey among under-five children in dembia district, north-west Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health and Biomedical Sciences. 2010;2(2):83. 03. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hadush A., et al. Assessment of knowledge and practice of neonatal care among post-natal mothers attending in Ayder and Mekelle Hospital in Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia 2013. SMU Medical Journal. 2016;3(1):509–525. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hailu A., et al. Community awareness of sore throat and rheumatic heart disease in Northern Ethiopia. Lancet. 2019;394(10213):1965–2038. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3369791. e38. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kebede K., et al. Prevalence and associated factors to uvula cutting on under five children in Amhara region, Debre Birhan town, 2016/2017. Int J Pediatr Child Health. 2017;5(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kefelew E., et al. Magnitude of uvulectomy and associated factors among caregivers having under five children in Arbaminch town public health facility. Gamo Zone, Southern Ethiopia. 2023;2022 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mamuye B., Gobena T., Oljira L. Hepatitis B virus infection and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in West Hararghe public hospitals, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35:128. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.35.128.17645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Medhin G., et al. Prevalence and predictors of undernutrition among infants aged six and twelve months in Butajira, Ethiopia: the P-MaMiE Birth Cohort. BMC Publ. Health. 2010;10:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitke Y.B. Bloody traditional procedures performed during infancy in the oropharyngeal area among HIV+ children: implication from the perspective of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1428–1436. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9681-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sentjens R., et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for HIV infection in blood donors and various population subgroups in Ethiopia. Epidemiol. Infect. 2002;128(2):221–228. doi: 10.1017/s0950268801006604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takele T., et al. Demographic and Health Survey at Dabat district in northwest Ethiopia: report of the 2008 baseline survey. Ethiopian Journal of Health and Biomedical Sciences. 2011;4(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gebre T., et al. The prevalence of gender-based violence and harmful traditional practices against women in the Tigray Region, Ethiopia. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2020;55(1):58–75. [Google Scholar]

- 51.UNCHR Harmful traditional practices affecting the health of women and children. Fact Sheet No. 23, U.O.o.t.H.C.f.H.R. (UNCHR) 2006 Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boyden J., Pankhurst A., Tafere Y. Harmful traditional practices and child protection. Young Lives Working Paper. 2013;93 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdullahi M., Amutta S. Traditional uvulectomy among the neonates: experience in a Nigerian tertiary health institution. Borno Medical Journal. 2016;13(1):16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sawe H., et al. Morbidity and mortality following traditional uvulectomy among children presenting to the Muhimbili National Hospital Emergency Department in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Emergency Medicine International. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/108247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ndu I.K., et al. Traditional Uvulectomy: a common and potentially life-threatening practice in a developing country. Medical Science and Discovery. 2022;9(8):450–453. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kibira S.P.S., et al. Uvula infections and traditional uvulectomy: beliefs and practices in Luwero district, central Uganda. PLOS Global Public Health. 2023;3(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oluwayemisi J.A., et al. A cross-sectional study of traditional practices affecting maternal and newborn health in rural Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal. 2018;31(1) doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.31.64.15880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data associated with this review can be found in the results section/supplementary materials/referenced articles.