Abstract

Background

The variables that contribute to positive and negative experiences of clinical education amongst student physiotherapists are well established. Multiple stakeholders are invested in the ongoing success of physiotherapy clinical placements given workforce challenges within the profession and the emerging relationship between clinical placements and new‐graduate recruitment. However, little is known about the relationship between clinical placement experiences and the career decisions of new‐graduate physiotherapists.

Purpose

To explore the influence of clinical placement experiences on new‐graduate physiotherapists' career intentions and decision making.

Methods

A qualitative study which used a general inductive approach. New‐graduate physiotherapists (n = 18) were recruited through a snowball sampling approach and participated in semi‐structured interviews. Ethical approval was obtained from The University of Queensland.

Results

Four overarching themes were generated; (1) clinical placements impact career decisions, (2) placements as a trial for future employment to identify professional preferences, (3) feeling valued as a team member, and (4) clinical educators’ shape placement experiences.

Discussion and Conclusion

Clinical placements play a significant role in directing new‐graduate physiotherapists’ careers, with clinical placement viewed as an opportunity to explore one's career options. A complex interplay of clinical and nonclinical variables was acknowledged by new‐graduates, with positive experiences during clinical placements considered to increase new‐graduate physiotherapist intentions to work in similar settings or contexts. Factors that contributed to positive experiences included accessible mentorship from clinical educators with regular feedback, and opportunities for the students’ contribution and clinical capacity to be acknowledged and valued. Recommendations are made for creating supportive workplace environments for clinical education and include prioritizing supportive mentorship.

Implications for Physiotherapy Practice

Clinical placement providers intending to recruit new‐graduates who have attended their workplace as students may benefit from implementing strategies that assist students to feel supported as valued members of the team. Additionally, the findings of this study may guide education providers when considering the training delivered to new and existing clinical placement sites with the aim of providing supported student learning environments.

Keywords: career decisions, clinical placement, new‐graduates, physiotherapy

1. INTRODUCTION

Physiotherapy is a profession in considerable demand, with growth in workforce required to meet the future needs of the Australian population. 1 However, it has been reported that “many physiotherapists leave the workforce and the profession early in their careers” (p.438), 2 with physiotherapists themselves predicting careers of 10 years or less. 3 Factors including limited career progression, perceived unsustainable clinical workloads, and poor remuneration have been identified as contributors to intentions for short careers amongst physiotherapists. 4 , 5 Whilst research has shed light upon variables that influence the career decisions of physiotherapists, little is known about the influence of pre‐professional clinical training experiences on new‐graduates early career decisions.

Clinical placements constitute a significant proportion of students’ exposure to the various areas of physiotherapy practice. In Australia, clinical placements occur in a range of settings to ensure students develop competencies required for practice, with full‐time placements across acute, community and rehabilitation settings. 6 Hall et al. 7 undertook a survey exploring the factors that influenced career decisions amongst recent physiotherapy graduates in Canada and identified clinical placement experiences as having a significant impact on these decisions. Of the new‐graduates surveyed, 46% changed their initial career intentions based on their clinical placement experiences. Key factors that shaped participants career decisions included exposure to new clinical areas or client cohorts, the workplace environment, and the positive influence of clinical educators. 7 Despite advances in understanding the influences of clinical placements on early career decisions, further exploration is warranted to explore how and why placement experiences can influence career decisions and the intersection of these factors, specifically in the Australian context.

Factors that contribute to positive experiences of clinical education amongst Australian student physiotherapists have been explored in a qualitative study by Heales et al. 8 The authors found a range of factors associated with higher satisfaction, including approachable and supportive clinical educators and workplaces, opportunities for students’ clinical reasoning and practical skills to be challenged, and receiving constructive and supportive feedback. Although this research provides important insight into student satisfaction, the influence of these clinical placements on career decision‐making has not been explored. The influence of clinical placements on students’ intentions for future employment may be of interest to stakeholders who are motivated to increase workforce capacity, and furthermore, may be of interest to local clinical education providers. Clinical education providers may consider the provision of clinical education as a recruitment strategy, with students who attend a workplace for clinical placement more likely to seek and obtain employment in that workplace amongst various cohorts, for example, rural practice. 9

Given the ever‐growing demand for physiotherapists, 1 combined with the expected short career span and challenges with attrition 3 , 5 it is vital to explore factors that influence new‐graduate physiotherapists’ employment intentions early in their careers. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the influence of clinical placement experiences on new‐graduate physiotherapists’ intentions for employment and subsequent career decisions.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Design

A qualitative research methodology, employing a general inductive approach, was selected to achieve the study's objectives. 10 Semi‐structured interviews were chosen to encourage open dialog and facilitate in‐depth exploration of the topic. Ethical approval was obtained for this study from The University of Queensland – Institutional Human Research Ethics, approval number #2021002523. At the time of the study, the primary researcher (LS) was a final‐year student physiotherapist actively involved in clinical placements. The secondary researcher (RF) was a practicing physiotherapist and a qualitative researcher with substantial experience in new‐graduate physiotherapy education, research, and clinical practice.

2.2. Participants

To ensure recency of experience, the completion of an Australian physiotherapy program within the past two years was required for participants to be eligible for the study. 11 A snowball sampling approach was employed, 12 with an initial 24 potential participants purposefully selected from the research teams’ professional network and contact by a singular email. All initial 24 potential participants were graduates of The University of Queensland. The email that was sent provided information about the study's objectives and inclusion criteria, with potential participants who met these criteria invited to share their contact information and availability. Participants who responded to the researchers were also invited to share the recruitment email with other new‐graduates, who may have been outside the initial sample contacted by the research team. A consent form was attached to a subsequent email that was sent to participants to arrange a mutually convenient interview time, with particpants required to return the consent form via email. In the event of nonreceipt within a 7‐day timeframe, the snowball sampling process was recommenced. The research team persisted in this iterative process until they believed that information power had been attained. 13

2.3. Data collection & interview procedure

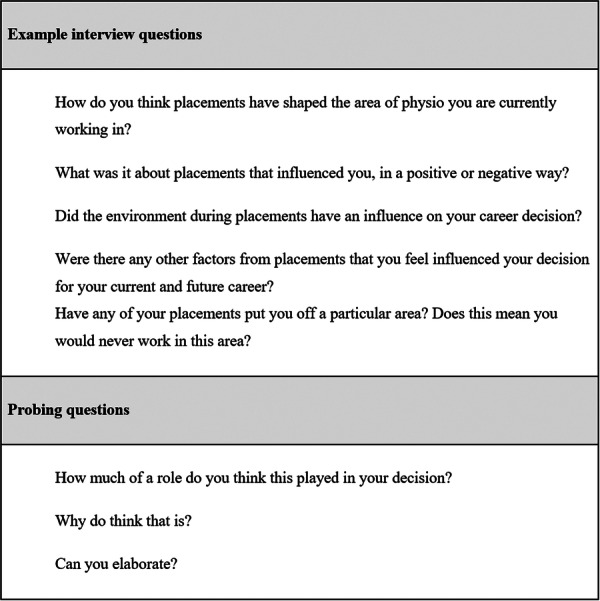

The research team devised a semi‐structured interview framework (Figure 1) that incorporated a mix of open‐ended and probing questions following a review of the existing literature. In May 2023, interviews (n = 18) were conducted by two members of the research team (LS/RP) via an online video‐conferencing platform. This approach facilitated audio recording and transcription and enabled a more diverse participant pool by offering scheduling flexibility and allowing for a geographically diverse population (Schneider et al., 2015).

Figure 1.

Example interview questions.

Verbal consent for audio recording was re‐confirmed before each interview, with participants also given a reminder of their right to withdraw before sharing demographic information (Table 1). To ensure in‐depth responses, all interviews adhered to the interview framework (Figure 1), 14 with interviews approximately 20 min in duration. The data collection approach followed reflexive methodology, where the research team consistently refined the interview guide to capture data that was yet to be obtained. 15

Table 1.

Participant Demographics.

| Participant reference | Age (Years) | Gender | Time since graduation (months) | Current workplace setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 32 | M | 6 | Private practice |

| P2 | 29 | M | 6 | Public hospital |

| P3 | 23 | M | 6 | Public hospital |

| P4 | 22 | M | 6 | Private practice |

| P5 | 23 | M | 18 | Private practice and public hospital |

| P6 | 26 | M | 18 | Private practice |

| P7 | 22 | F | 6 | Private practice |

| P8 | 25 | F | 6 | Private practice |

| P9 | 27 | F | 6 | Private practice |

| P10 | 24 | F | 6 | Public hospital |

| P11 | 21 | M | 6 | Public hospital |

| P12 | 24 | F | 6 | Public education |

| P13 | 23 | M | 6 | Private practice |

| P14 | 23 | M | 6 | Public hospital |

| P15 | 25 | M | 6 | Private practice |

| P16 | 22 | M | 18 | Private practice, hospital, community rehabilitation |

| P17 | 21 | M | 6 | Public hospital |

| P18 | 22 | F | 6 | Public hospital |

2.4. Data analysis

All audio recordings underwent transcription using automatic speech‐to‐text software. Subsequently, the transcriptions were reviewed by the principal researcher (LS) and manually corrected. Hesitation words, for example ‘like’ and ‘um’ were removed from the text for clarity. The analysis adopted a general inductive approach, which entailed forming concise summaries from extensive raw data and establishing clear connections with the research objectives. 10 Data analysis was performed by following the steps outlined by Thomas 10 : (1) cleaning raw data files; (2) closely scrutinizing the text; (3) generating categories; (4) integrating coded and uncoded text; and (5) iteratively refining categories. The primary researcher (LS) conducted numerous in‐depth readings of each transcript to ensure immersion with the data and assigned meaningful ideas with corresponding codes. Codes were then grouped into categories based on similar underlying concepts before subsequently being organisedinto preliminary themes. The research team engaged in open discussions to resolve disparities in data interpretation and establish the final themes during five separate meetings. The second researcher provided support and oversight at every stage of the analysis.

Several strategies were employed to uphold the validity and reflexivity of data analysis. Participants were emailed interview transcripts for member checking to ensure accuracy of data. The interviewers (LS/RP) were not acquainted with the participants, with careful consideration taken to avoid leading questions. Additional strategies encompassed following a pre‐established interview framework for systematic data collection, precise interview transcription to minimize assumptions, along with regular team meetings to deliberate on analytical procedures.

3. RESULTS

A total of 18 participants were interviewed (Table 1). Four overarching themes were generated (1) clinical placements impact career decisions, (2) placements as a trial for future employment to identify professional preferences, (3) feeling valued as a team member, and (4) clinical educators’ shape placement experiences.

-

1)

Clinical placements impact career decisions.

Many participants expressed that their experience on clinical placement significantly influenced their intentions for employment and subsequent career path. Most participants reflected on feeling indecisive about their employment intentions throughout their university study, with clinical placement viewed as the stimulus that “made me realize where I want to work” (P14), and ultimately “contributed to my career choices” (P12). Placements were viewed as having a significant influence because student felt it was their “first round of exposure” (P16) to clinical practice, in contrast to their university learning.I think a huge factor that can lead people one way or the other when they're choosing their sort of career path… is the experiences they have [on clinical placement]. (P8)Why does placement affect us? I think it's because that's the only place you're really exposed to [practice]… 3 years you study something and you're so interested in it. And then you finally get an opportunity to put your skills into practice. (P7)

Some participants felt they associated positive and negative experiences of clinical placement, with the overall area or setting of clinical practice. Negative experiences in an organization resulted in some participants avoiding employment there as a new‐graduate and in some instances avoiding the whole area of practice. For example, some participants expressed not wanting to work in hospitals due to their negative experiences, and as a result they “did not even apply to a hospital” (P7).

If you have a good experience or a bad experience, you're going to associate it to that particular field…in the sense that we're more likely to want to pursue something we enjoy more. (P17)

Conversely, several participants felt that placements did not significantly influence their intentions for employment and subsequent career path, as they had previously established strong preferences regarding their careers. One participant stated that he “set out pretty early with what [I] wanted to do” (P1), however also acknowledged that a positive placement experience in a different area of practice to his established preference resulted in him applying for jobs in that setting. Initially these few participants perceived placements as having minimal or no impact on their career choices however on deeper reflection they acknowledged the placement had played a role, alongside other factors.

-

2)

Placements as a trial for future employment to identify professional preferences.

Participants conveyed that clinical placements offered them the opportunity to determine their professional preferences for variables such as flexibility, consistency, team structure, policies and procedures, client cohorts, and commute time. With clinical placements as a trial for professional preferences, they were viewed by all participants as contributing to intentions for future employment, which for most participants, included intentions to be employed across multiple organizations throughout their career. For some participants their preferences were unrelated to the clinical work, for example “[I] actually liked the long drive to process my thoughts and stuff, so, I definitely knew I wanted to work at a very far location” (P7). Whereas others’ preferences were specific to a workplace, for example “really loved the team there” (P8), or a setting of practice, for example “I like the pace of a hospital much more than I like the pace of musculoskeletal practice” (P11).I really liked how variable MSK [musculoskeletal] was and the different sort of presentations, different kinds of people, different kinds of personalities, different ages. I really, really liked the variety there. (P8)

Participants who valued flexibility commonly voiced that their experience of flexible working hours during private practice clinical placements had led them to seek employment in that setting, and similarly participants who valued consistent working hours identified preferences for hospital‐based employment.

I think hospital work as a physio was a big appeal to me because you start at 7:30, and you finish at 4:00, and that is your day. (P10)

I like working my own hours…working in the hospital, you have to show up at a certain time…you can only have your break at a certain time, for me, on placement, that's fine, because I'm a student, right? But now that I have the choice…I feel like that lifestyle factor is a big, the biggest thing for me. (P16)

I quite like having that flexibility and variability in my day. In the acute setting, it can be quite different every day, whereas I saw that in the community setting it was a bit more repetitive and much of the same. (P18)

Placements made some participants more aware of the importance of a good environment and “team culture” (P10, P3), and for some participants led them to seek employment at the workplace where they undertook clinical placement. Having “supportive” teammates (P9, P11, P8, P14) was also important in creating a positive environment which enhanced the student experience and positively impacted career decisions. In contrast, one participant described the private setting generally as having a different culture, and for her “placements consolidated that I probably didn't want to work in a private setting” (P10).

-

3)

Feeling valued as a team member with some autonomy.

Participants felt strongly that being valued as part of the team by the clinical placement workplace, and their work and capabilities being valued by their clinical educator positively contributed to their perceptions of the clinical placement. These perceptions then subsequently informed their intentions to seek employment in that workplace or area of practice, as participants felt that their experience as a new‐graduate would likely reflect their experience as students. For example, one participant who felt that their capabilities were not valued stated that “after my inpatient placement, I knew that I was craving a little bit more in terms of autonomy or flexibility, so that kind of actually ruled out going into [deidentified] as a new‐grad” (P9).

One way that particpants felt valued in the workplace was when they were perceived to be a contributing member of the team, for example, one participant stated that clinical placement providers should “emphasize that they're part of the team, rather than a student who happens to be there” (P15). Another participant reflected, “it's so important you have a good relationship with the team, otherwise you won't enjoy being at the workplace” (P5). Ways that participants felt that they were valued as team members included involving students in “team meetings, or team building activities” (P15), and informal staff activities such shared locations for breaks.We're encouraged to go as students to lead multi‐disciplinary team discussions with the rest of the team, and the other physios were really inclusive, always asking you to come along experiencing the different areas. So, you felt like you were an active team member rather than just watching from the side. (P10)

Approaches that facilitated particpants feeling that their work and capabilities were valued by their clinical educator included allowing the students ownership and autonomy of their caseload within safe reasonable limits and allowing students opportunities to be challenged. When participants felt that they were not allowed reasonable ownership and autonomy, it was perceived to negatively impact their experience and their learning.

You have full on 80% to 90% ownership of your caseload with like a close supervision of your CE…it gives you a sense of like… A, you feel reward[ed]…. B, you feel like you learn a lot, it's a steep learning curve and, C, you feel that sense of accomplishment. (P12)

I felt very much like a student until the last day… so I think it made me definitely less competent in MSK [musculoskeletal] because I didn't really know how to link all the components together… I was leaning a little bit more towards hospitals. (P8)

There's too big of a division between what the students are doing, and what the other physios are doing. I think, when you start to trust the student within their later placement and start to trust them with more complex sort of tasks, it makes the student feel more inclined to choose that sort of career and to follow that sort of path. (P11)

-

4)

Clinical educators’ shape placement experiences.

Interestingly, the supervision style of the clinical educators was considered by participants to significantly influence their experiences of the clinical content, and subsequently, influence their intentions for future employment in similar contexts. The professional relationships between particpants and educators was acknowledged to “affect where you end up working as well” (P11), with clinical educators viewed as gate‐keepers to participants feeling as though they were contributing to the team. One participant voiced that they would not consider a new‐graduate role with their previous clinical educator who “always seemed very busy and not have time to [provide] a little bit of mentoring” (P9), as they believed that the experience may be similar in a new‐graduate role. Not being able to access support as a student was a negative influence for participants employment intentions, as they strongly desired new‐graduate roles where they perceived that they would be able to access support.

The educator definitely matters… there was a different educator in the same environment, same patients, none of these patients discharged, and my whole mood completely changed…I think it's not even the hospital, I think it's the educator. (P7)

Clinical educators who had a positive influence on participants’ placement experience were described as “supportive” (P9, P2, P18, P8, P17, P12, P3) and “encouraging” (P2), with a “willingness to give feedback” (P17, P3) whilst “not putting pressure [on the student]” (P12). Communication styles which included “a good amount of firmness, humor, [and] feedback” (P3) were considered to create a safe learning environment, with the communication of clear expectations viewed as fundamental for positive experiences. ‘I know we have a reputation. And it's hard. But this is why, and these are my expectations for you’… [hearing that] was really, really beneficial. I knew right from the start because [of] her honesty, because she was very straight up from the get‐go. I knew exactly what I needed to do, so I felt really, really supported that way.” (P8)

Conversely, clinical educators who had a negative influence on participants’ placement experience were perceived as “lacking support and empathy” (P4) and having poor communication skills.

My placement at [deidentified] sort of taught me that an educator could really make a difference to a placement experience and a communication style, someone being blunt can really make your days hard. (P3)

4. DISCUSSION

This study has explored the influence of clinical placement experiences on new‐graduate physiotherapists’ intentions for employment and career decisions. The findings of the study suggest that clinical placements play a significant role in directing new‐graduate physiotherapists careers, with clinical placement viewed as an exploration for one's career. Opportunities to trial a variety of workplace structures and expectations, client cohorts, and other nonclinical variables were viewed by new‐graduates as particularly valuable. Ultimately, positive experiences during clinical placements were considered to increase new‐graduate physiotherapist intentions to work in similar settings or contexts, with the inverse holding true for negative experiences and decreasing intentions. Factors that contributed to positive experiences of clinical placements included accessible mentorship from clinical educators with regular feedback, and opportunities for the students’ contribution and clinical capacity to be acknowledged and valued.

New‐graduates in this study expressed intentions to pursue careers with organizations or areas of practice, to which they associated positive experiences during placements, and avoid settings and areas of practice in which they associated negative experiences. Similarly, in a cross‐sectional study of 873 health professional students, Fatima et al. 16 found a strong association between a positive rural clinical placement experience and intention to work in a rural setting, with students who were satisfied with their rural placements twice as likely to seek a career in a rural setting. New‐graduates in the current study highlighted the influence of the workplace environment, their clinical educators, and the perception of value in their contribution and capability as a member of the team as contributors to positive experiences. When participants had positive experiences due to these factors, they viewed the clinical practice area and workplace favorably, increasing their likelihood of pursuing careers in similar settings, generally regardless of their initial personal interests. For instance, those with a strong interest in one area of practice, who had a positive placement experience in an unrelated area they had not previously considered, applied for new‐graduate positions in the unconsidered field. Conversely, negative experiences due to these factors lead to some participants avoiding workplaces, and in some instances, entire areas of clinical practice. Importantly, these perspectives resulted from participants perceiving placements to be a trial of the workplace and its environment, in that if such factors were undesirable, i.e., if they did not feel valued, or clinical educators and staff were not supportive, it would be perceived as an expectation of their potential experience as a new‐graduate. Educational theory that underpins clinical placements provides some guidance to explain these experiences where placements are often viewed and experienced as career exploration, as placements are considered to provide opportunities to not only learn but build career identity (p.318). 17 Our study revealed that the perceived experience of being valued and having autonomy within reasonable limits during placements plays a pivotal role for new‐graduates in their early career decisions, expanding on prior research that highlighted the importance of perceived control over practice on job satisfaction. 18 , 19

Placements can shape students’ short and long‐term career expectations and attitudes. 17 Reflecting the same notion, our study found that participants viewed placements as valuable in increasing their awareness of factors important to them within their future workplace. Variables related to both the clinical (i.e., client cohort, caseload variability) and nonclinical (i.e., teamwork culture, commute time) features of clinical education experiences were taken into consideration by all participants when deliberating on employment intentions. Interestingly, new‐graduates considered both clinical and nonclinical variables in relation to work‐life balance and lifestyle impacts, a similar finding to recent research in the Australian context. 5 Previous research has also reported that work‐life balance in younger health professionals is a primary influencer of workplace intentions. 5 The findings of our study may be attributed to new‐graduates being mostly Gen Z, born approximately between 1997 and 2012, as evidence suggests people from this cohort are more inclined towards careers with organizations which align more closely with their personal values, compared to earlier generations. 20 , 21 It is important to note that new‐graduates in our study were receptive to exploring other workplaces and areas of practice in the longer‐term future. This finding also reflects the characteristics of the Gen Z workforce, including in physiotherapy, who are generally more open to transitioning between different employers and organizations throughout their careers. 5 , 22

Adding to the established research about the benefits of mentorship in physiotherapy, 23 , 24 the findings of our study indicate that successful mentorship from clinical educators may impact career decisions. Clinical educators and clinical staff who are perceived to be supportive during clinical education of student physiotherapists have previously been associated with higher levels of student satisfaction. 8 Factors that were considered to contribute to positive experience of mentorship in our study included accessibility of feedback opportunities, invitation to partake in all elements of client care for example, multidisciplinary meetings, and clear communication of expectations; themes which echo the work of Heales et al. 8

Clinical placement providers intending to recruit new‐graduates who have attended their workplace as students may benefit from implementing strategies to create environments where students can be welcomed and supported as valued members of the team. 25 Furthermore, clinical educators are encouraged to provide easily assessable opportunities for feedback on student performance and facilitate student autonomy within safe reasonable limits. These findings also have important implications for education providers and the wider profession when considering the development and training delivered to new and existing clinical placement sites with the aim of providing supported student learning environments. Further research investigating the impact of training for clinical education providers may be beneficial in building on the findings of this study.

4.1. Limitations

Participants may have provided responses that they perceived to be socially desirable to the researchers, which may have introduced bias or skewed the results of the study. Additionally, the primary researcher's immersion in clinical experience throughout the conduction of this study may have introduced observer bias, potentially affecting data interpretation. Finally, participants were recruited through the professional networks of the research team, with some snowballing recruitment outside of The University of Queensland. The skewed nature of the sample to one geographic location in Australia may limit the generalizability of the results.

5. CONCLUSION

The findings of this study highlight the interplay of factors within clinical placements that influence new‐graduate physiotherapists’ employment intentions and career decisions. These findings underscore the importance of providing students with a range of clinical placement experiences and fostering supportive workplace environment. Strategies for creating supportive workplace environments for clinical education include valuing the contribution and capability of the student as a member of the team and providing supportive mentorship with constructive feedback.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lakhvir Singh: Conceptualization; writing—review and editing; writing—original draft; formal analysis; investigation; data curation; methodology; project administration. Romany Martin: Conceptualization; writing—review and editing; writing—original draft; project administration; formal analysis; methodology; supervision. Allison Mandrusiak: Conceptualization; writing—review and editing; writing—original draft; formal analysis; methodology; supervision. Rachel Phua: Conceptualization; writing—review and editing; formal analysis; data curation; investigation. Hussan Al‐Hashemy: Conceptualization; writing—review and editing; formal analysis; data curation; investigation. Roma Forbes: Conceptualization; writing—review and editing; writing—original draft; formal analysis; project administration; methodology; supervision.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from The University of Queensland's Institutional Human Research Ethics under approval number #2021002523.

TRANSPARENCY‐STATEMENT

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Lakhvir Singh, the lead author, had full access to all of the data in this study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Romany Martin, the corresponding author, affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Participants were required to provide written consent via a written consent form approved by the ethics committee. Verbal consent for audio recording was re‐confirmed before each interview.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

To the authors best knowledge, this manuscript contains no material from other sources, as such, no permissions were sought to reproduce material from other sources.

STUDY REGISTRATION

Given the design of the study, the authors choose not to register the study with any peripheral organizations or registers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the physiotherapists involved for generously sharing their time and insights with the study. No fundings was received for this project, outside of the employment of some authors by the University of Tasmania (RM) and the University of Queensland (AM/RF) and the expectation that these authors undertake research within their allocated workloads. Open access publishing facilitated by University of Tasmania, as part of the Wiley ‐ University of Tasmania agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Singh L, Martin R, Mandrusiak A, Phua R, Al‐Hashemy H, Forbes R. How do clinical placements influence the career decisions of new‐graduate physiotherapists in Australia? A qualitative exploration. Health Sci Rep. 2024;7:e70132. 10.1002/hsr2.70132

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared. The authors have chosen not to share data, in efforts to ensure the anonymity of the participants who were included in this research.

REFERENCES

- 1. Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency & National Boards . Physiotherapy Workforce Analysis. 2021. Retrieved on 12 April 2024, from: https://www.ahpra.gov.au/documents/default.aspx?record=WD23%2F32504&dbid=AP&chksum=Zt8pYVO1T5wozSq8yPCK8A%3D%3D

- 2. Pretorius A, Karunaratne N, Fehring S. Australian physiotherapy workforce at a glance: a narrative review. Aust Health Rev. 2016;40(4):438‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mulcahy AJ, Jones S, Strauss G, Cooper I. The impact of recent physiotherapy graduates in the workforce: a study of curtin university entry‐level physiotherapists 2000–2004. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34(2):252‐259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bacopanos E, Edgar S. Identifying the factors that affect the job satisfaction of early career notre dame graduate physiotherapists. Aust Health Rev. 2016;18 40(5):538‐543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Forbes R, Wilesmith S, Dinsdale A, et al. Exploring the workplace and workforce intentions of early career physiotherapists in Australia. Physiother Theory Pract. 2023:1‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Physiotherapy Board of Australia and Physiotherapy board of New Zealand . Physiotherapy practice thresholds in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. 2015. Retrieved on 12 April 2024, from: https://cdn.physiocouncil.com.au/assets/volumes/downloads/Physiotherapy‐Board‐Physiotherapy‐practice‐thresholds‐in‐Australia‐and‐Aotearoa‐New‐Zealand.PDF

- 7. Hall M, Mori B, Norman K, Proctor P, Murphy S, Bredy H. How do I choose a job? factors influencing the career and employment decisions of physiotherapy graduates in Canada. Physiother Can. 2021;73(2):168‐177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heales LJ, Bonato K, Randall S, et al. Factors associated with student satisfaction within a regional student‐led physiotherapy clinic: a retrospective qualitative study. Aust J Clin Educ. 2021;10(1):1‐7. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seaman CE, Green E, Freire K. Effect of rural clinical placements on intention to practice and employment in rural Australia: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9):5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Evaluat. 2006;27(2):237‐246. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chipchase LS, Williams MT, Robertson VJ. Preparedness of new graduate Australian physiotherapists in the use of electrophysical agents. Physiotherapy. 2008;94(4):274‐280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Naderifar M, Goli H, Ghaljaie F. Snowball sampling: a purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides Dev Med Educ. 2017;14(3):1‐6. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753‐1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Family Med Community Health. 2019;7(2):e000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pessoa ASG, Harper E, Santos IS, Gracino MCS. Using reflexive interviewing to foster deep understanding of research participants’ perspectives. Int J Qualitat Methods. 2019;18:1609406918825026. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fatima Y, Kazmi S, King S, Solomon S, Knight S. Positive placement experience and future rural practice intentions: findings from a repeated cross‐sectional study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:645‐652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inceoglu I, Selenko E, McDowall A, Schlachter S. (How) do work placements work? scrutinizing the quantitative evidence for a theory‐driven future research agenda. J Vocat Behav. 2019;110:317‐337. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Graham KR, Davies BL, Woodend AK, Simpson J, Mantha SL. Impacting Canadian public health nurses’ job satisfaction. Can J Public Health. 2011;102:427‐431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Halcomb E, Bird S. Job satisfaction and career intention of Australian general practice nurses: a cross‐sectional survey. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(3):270‐280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bohdziewicz P. Career anchors of representatives of generation Z: some conclusions for managing the younger generation of employees. Zarządzanie Zasobami Ludzkimi;. 2016;6:57‐74. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deloitte Global . The Deloitte Global 2022: Gen Z & Millennial Survey. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited; 2022. Retrieved on 12 April 2024, from. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/at/Documents/human‐capital/at‐gen‐z‐millennial‐survey‐2022.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22. Benítez‐Márquez MD, Sánchez‐Teba EM, Bermúdez‐González G, Núñez‐Rydman ES. Generation Z within the workforce and in the workplace: a bibliometric analysis. Front Psychol. 2022;12:736820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Forbes R, Lao A, Wilesmith S, Martin R. An exploration of workplace mentoring preferences of new‐graduate physiotherapists within Australian practice. Physiother Res Int. 2021;26(1):e1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martin RA, Mandrusiak A, Lu A, Forbes R. Mentorship and workplace support needs of new graduate physiotherapists in rural and remote settings: a qualitative study. Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi‐Professional Journal. 2021;22(1):15‐32. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Forbes R, Dinsdale A, Dunwoodie R, Birch S, Brauer S. Exploring strategies used by physiotherapy private practices in hosting student clinical placements. Aust J Clin Educ. 2020;7(1):1‐3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared. The authors have chosen not to share data, in efforts to ensure the anonymity of the participants who were included in this research.