Abstract

Background

Caregiver stress can pose serious health and psychological concerns, highlighting the importance of timely interventions for family caregivers of people with dementia. Single-session mindfulness-based interventions could be a promising yet under-researched approach to enhancing their mental well-being within their unpredictable, time-constrained contexts. This trial will evaluate the effectiveness and feasibility of a blended mindfulness-based intervention consisting of a single session and app-based follow-up in reducing caregiver stress.

Methods/Design

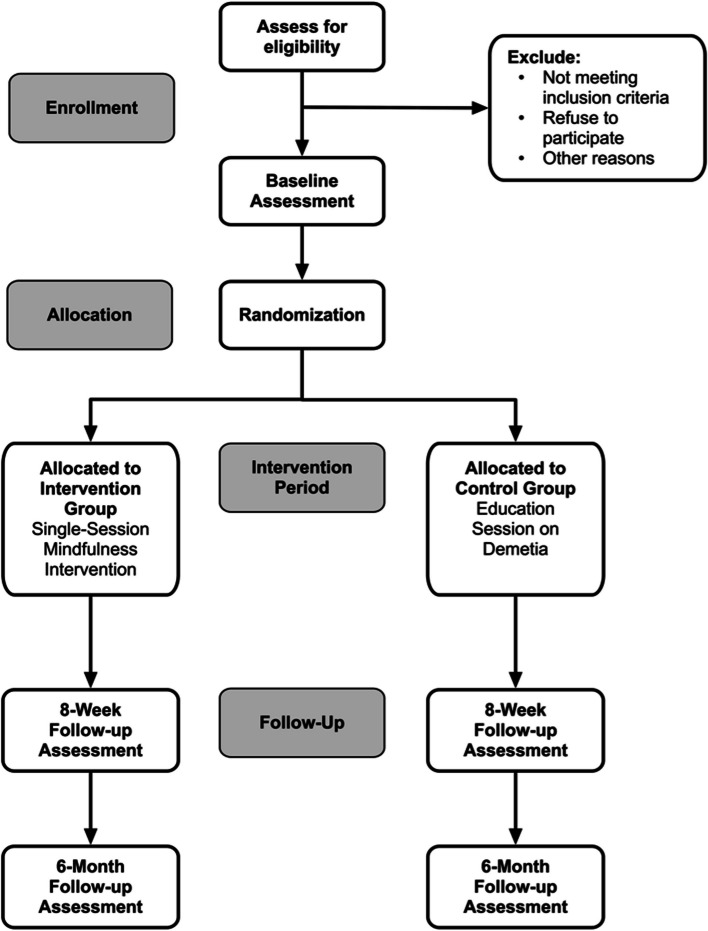

The study is a single-blinded randomized controlled trial with two arms (intervention versus an education session on dementia care) and assessments at baseline, 8 weeks, and 6 months. The eligibility criteria include: family caregivers aged 18 years or older; providing care for an individual with a confirmed medical diagnosis of dementia for at least 3 months prior to recruitment, with a minimum of 4 hours of daily contact; and exhibiting a high level of caregiver stress. The intervention comprises a 90-minute group-based session with various mindfulness practices and psychoeducation. Participants will receive a self-practice toolkit to guide their practice over a duration of 8 weeks. Sharing activities will be implemented through an online social media platform. The primary outcome is perceived caregiving stress. The secondary outcomes include depressive symptoms, positive aspects of caregiving, dyadic relationship, trait mindfulness, and neuropsychiatric symptoms of care recipients. The feasibility outcomes include eligibility and enrollment, attendance, adherence to self-practice, and retention, assessed using mixed methods.

Discussion

The study will contribute to the evidence base by investigating whether a single-session mindfulness intervention is effective and feasible for reducing caregiver stress among family caregivers of people with dementia.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT06346223. Registered on April 3, 2024.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40359-024-02027-7.

Keywords: Mindfulness, Mindfulness-based intervention, Caregiver stress, People with dementia, Family caregivers, Randomized controlled trial

Background

Dementia is a neurodegenerative disease common among older people, leading to a progressive decline in cognitive function and self-care abilities [1]. As the population continues to age, the prevalence of dementia is anticipated to increase substantially in the absence of prevention and treatment [2]. Approximately 50 million people worldwide are now living with dementia, and this number is projected to increase to 152 million by 2050 [3]. The responsibility of caring for people with dementia (PWD) primarily falls on their family members, who provide assistance with daily activities and managing illness-related behavioral problems, such as wandering and agitation [4]. The demanding nature of caregiving tasks, unpredictable symptoms related to the illness, and limited time for other social activities can lead to significant stress levels for caregivers, leading to the development of various physical and psychological conditions, including depression, insomnia, and compromised immune function [5]. Caregiver burnout is also a significant factor that can lead to the premature institutionalization of care recipients, resulting in increased healthcare costs [6]. Furthermore, the high levels of stress and poor psychosocial well-being experienced by caregivers are associated with a poor dyadic relationship and more severe behavioral and psychological symptoms in PWD [6]. Therefore, timely interventions aimed at alleviating caregiving stress are crucial for both caregivers and care recipients.

Caregiving stress and mindfulness-based interventions

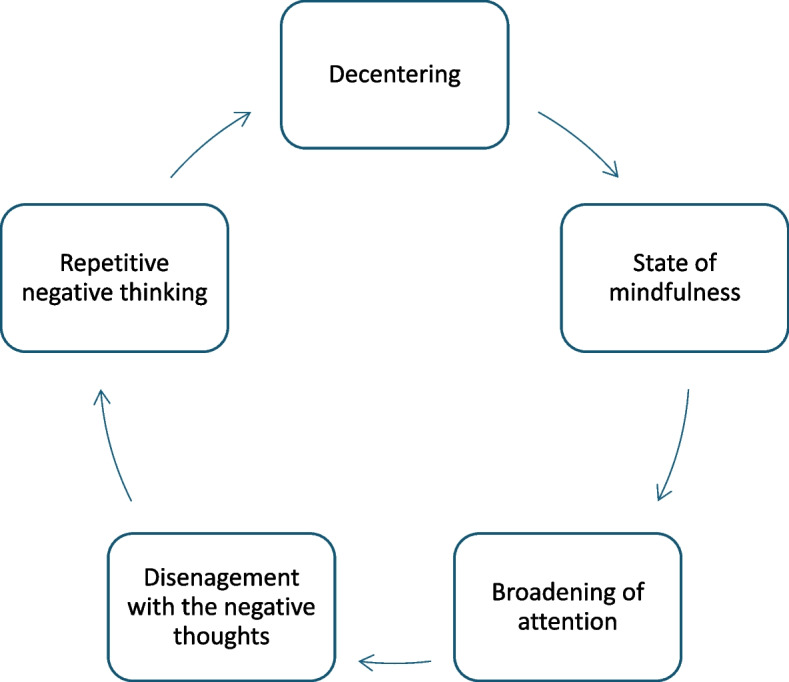

According to the stress appraisal and coping theory, caregiving stress is a two-way process involving the presence of caregiving stressors and the response and appraisal from the caregiver [7]. Currently, the majority of supportive services or interventions, such as respite care and educational talks, adopt a problem-solving approach to alleviate caregiving stress; however, this approach typically produces only a short-term effect (e.g., immediately after the intervention) in reducing stress [8]. Stress arising from caregiving is often chronic, with many of the stressors being linked to the illness of PWD, making them challenging to modify [8]. It is recommended that caregivers be empowered to manage stress through an emotion-focused approach, such as a mindfulness-based intervention [7]. The mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) is an evidence-based psychosocial intervention aimed at enhancing the self-awareness of participants in the present moment and fostering inner calm and a non-judgmental mind. This empowers participants to observe their thoughts and feelings from a distance, accepting them as they are without judgment of their quality [9]. By enhancing caregivers’ self-awareness in the present moment through mindfulness practice, caregivers can detach themselves from negative experiences and thoughts through the process of decentering, leading to stress reduction (for a conceptual model, see Fig. 1) [9].

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis have provided further evidence that the MBI can be an effective standalone intervention for enhancing the psychological well-being of caregivers [10]. Specifically, the MBI has the potential to significantly reduce stress in family caregivers of PWD, as indicated in another systematic review and meta-analysis [11]. Mindfulness practices emphasize the importance of caregivers responding calmly to stressors (i.e., different neuropsychiatric symptoms in the care recipients) and accepting them without judgment [12]. By cultivating mindfulness through regular practices, caregivers can develop a calmer response towards their care recipients, potentially improving their dyadic relationship. This, in turn, may result in improvements in the neuropsychiatric symptoms of the care recipients. For example, a modified mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), specifically tailored to the needs of family caregivers, has been implemented in a feasibility study and a large clinical trial, demonstrating positive effects on caregiving stress [13, 14]. However, there are a few limitations in these interventions. First, an intensive MBI, such as an 8-week program, may not be cost-effective, especially considering the increasing number of caregivers that need to be accommodated. Second, family caregivers, who are typically occupied with caregiving tasks, may encounter difficulties in attending intensive training programs. Third, MBI are well-suited to target various psychological symptoms, such as high levels of stress, and a brief mindfulness intervention protocol could also be adopted as a program for the preventative intervention for psychological distress in community-dwelling caregivers. A comprehensive narrative review has indicated that there is no significant dose-response relationship between mindfulness and participants’ psychological outcomes, suggesting that more MBI sessions may not necessarily produce a larger effects on psychological outcomes once participants have learned and mastered mindfulness skills [15].

Single-session intervention

The single-session intervention (SSI) is an umbrella term that describes different therapeutic interventions conducted within a single visit by an interventionist to address clients’ problems and/or help them achieve their goals [16]. The SSI can be flexibly modified to incorporate core elements of different evidence-based treatments, into a single treatment package, such as psychoeducation, mindfulness, and behavioral activation [17]. The primary aim of the SSI is to ensure that the client receives a plan to resolve their issue, gains confidence in possessing the skills and resources to address it, and acquires the knowledge to solve it following a single session [16]. The SSI has been widely utilized in managing mental health problems, with its effectiveness supported by decades of research involving diverse populations, such as adolescents with anxiety [18]. A recent systematic review that included 18 trials demonstrated that the SSI was superior to no treatment in reducing anxiety symptoms, and similar results were observed while comparing the SSI to multi-treatment sessions (ranging from 3 to 5 sessions) [18]. During an SSI, the interventionist assists the client in identifying specific problems, exploring potential solutions, and considering how to implement these solutions post-session.

It is crucial to understand that the term SSI does not solely refer to a single session but rather to the premise that the initial session is approached as a distinct treatment package [16]. Clients must address their challenges, such as stress, by practicing the skills learned and utilizing the resources obtained during the SSI, such as contact points for any further questions or concerns. It is essential to equip clients with the active components of the skills necessary for positive outcomes through the SSI [16].

Rationale and objectives

Given the increasing numbers of caregivers of PWD, there may be insufficient resources to implement intensive MBI with prolonged durations. Additionally, the majority of family caregivers of PWD are heavily engaged in various caregiving tasks; hence, a single-session mindfulness-based intervention (SSMI) may be more suitable for this population than a traditional mindfulness program. There is growing evidence indicating that the SSI is effective in enhancing mental health across diverse populations [17, 19]. The SSI has shown promise in enhancing accessibility and reducing the financial constraints typically associated with longer-term treatments/interventions, and has been adopted as the primary prevention intervention program in certain community care settings [16]. While a few pilot studies have demonstrated preliminary effects of SSMI on promoting mental health, these studies primarily focused on adolescents or adults in general, rather than family caregivers of PWD who often experience chronic caregiver stress [17, 19]. This highlights the need for further research to examine the effectiveness of the SSMI on reducing stress in family caregivers of PWD. Moreover, several limitations were observed in previous SSI and SSMI studies, including small sample sizes, unclear lasting effects (e.g., lack of follow-up measurements), and insufficient information on adherence rates during mindfulness practice.

The primary objective of this proposed randomized controlled trial (RCT) is to assess the effectiveness of a SSMI, specifically designed for family caregivers of PWD, in comparison to an education session on dementia care on caregiver stress at two time points: 8 weeks after the intervention (T1) and at the 6-month follow-up (T2). Secondary objectives are to evaluate the impact of the SSMI compared to the education session on other caregiver outcomes, including depression, dyadic relationship quality, positive aspects of caregiving, trait mindfulness, and feasibility-related measures. The effect of the SSMI on the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in the care recipients will be evaluated too.

Research questions and specific hypotheses

The proposed trial aims to address the following research questions:

Is the SSMI more effective than an education session on dementia care in reducing caregiver stress for family caregivers of PWD at T1 and T2?

Hypotheses: Participants in the SSMI will demonstrate greater post-intervention improvement in caregiver stress at T1 (8 weeks after the intervention) compared to participants in the education session on dementia care. Gains will be maintained at T2 (6 months following the intervention).

-

2.

Is the SSMI more effective than an education session on dementia care in reducing depression and improving dyadic relationship quality, positive aspects of caregiving, and levels of mindfulness for family caregivers of PWD at T1 and T2?

Hypotheses: Participants in the SSMI will exhibit greater post-intervention improvement in depression, dyadic relationship quality, positive aspects of caregiving, and levels of mindfulness at T1 (8 weeks after the intervention) compared to participants in the education session on dementia care. Gains will be maintained at T2 (6 months following the intervention).

-

3.

Is the SSMI more effective than an education session on dementia care in reducing the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in care recipients at T1 and T2?

Hypotheses: Care recipients of participants in the SSMI will show greater post-intervention improvement in the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia at T1 (8 weeks after the intervention) compared to participants in the education session on dementia care. Gains will be maintained at T2 (6 months following the intervention).

Methods

Study design

The study is a two-arm, single-blinded, parallel-group RCT with a 1:1 allocation ratio of participants and a repeated measure design. The Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) checklist can be found in Additional File 1. Participant evaluations will be conducted at three time points: baseline (T0; 0 weeks), 8 weeks after the intervention (T1; 8 weeks), and at follow-up (T3; 6 months) (Fig. 2). Any amendments to the trial will be reported to the trial registry.

Fig. 2.

Study flow diagram

Participants

The target population will consist of community-dwelling family caregivers of PWD. Recruitment will take place at five elderly centers affiliated with two local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Hong Kong, which currently serve more than 2,000 members with a confirmed medical diagnosis of dementia and their caregivers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible participants are family caregivers aged 18 or above who provide care for an individual residing in the community with a confirmed medical diagnosis of any type of dementia, as verified from the NGO record or the care recipients’ medical record. Participants must have been providing care for at least 3 months prior to recruitment, with a minimum of 4 h of daily contact. They must exhibit a high level of caregiver stress, defined as a summed score of 25 or higher on the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) [20]. Additional inclusion criteria include the ability to speak, read, and write Chinese.

Exclusion criteria include having participated in any structured mind-body intervention or structured psychosocial intervention within the 6 months prior to recruitment, as well as having an acute psychiatric condition that is potentially life-threatening that would limit the caregiver’s participation in the study, which is determined by an affirmative response to any item on the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) [21]. Unwillingness to be randomized will also be considered as an exclusion criterion. A detailed description of all measures is provided below.

Procedures

During the recruitment process, potential participants will be referred to the research team by the collaborators. A research assistant will screen all potential participants to determine their eligibility for participation in this study. The researcher will train three research assistants on how to use all the outcome instruments with reference to the latest user guidelines for the instruments. The inter-intra-rater reliabilities will be evaluated using intra-class correlations (ICC). Acceptable levels of reliability (ICC > 0.90) will be established by comparing the scores rated by the assessor and the researcher prior to the start of the study and checking them throughout the data collection period. To maximize data completeness, data will be collected through an online portal and double entry will be performed when possible. If necessary, two registered clinical psychologists will provide their opinion and/or conduct assessments during the screening process. Written informed consent will then be obtained by the research assistant from all participants after explaining all aspects of the study and addressing any questions they may have. Participants have the right to refuse participation and can withdraw from the study at any time. Following the eligibility screening, participants will be interviewed and undergo a baseline assessment.

Baseline assessment

If no exclusionary criteria are met, participants will be asked to complete a battery of questionnaires that assess health-socio-demographic data for both family caregivers and their recipients. Additionally, effect-related outcome measurements will be collected, which include perceived caregiving stress, depressive symptoms, positive aspects of caregiving, dyadic relationship quality, trait mindfulness, and neuropsychiatric symptoms of the care recipients. All baseline measures will be collected prior to the randomization process.

Intervention

Single-session mindfulness intervention

The SSMI was developed based on the toolkit of brief interventions in mental health [22] and the MBI protocol that was tested and adopted in our two local studies [13, 14], which has provided us with evidence about the barriers that caregivers face when learning mindfulness, as well as the facilitators to doing so, and their habits (e.g., duration, form of mindfulness). Based upon this knowledge, we selected and integrated different active components of mindfulness into the SSMI. The SSMI comprises a 90-minute group-based session that incorporates various mindfulness practices. These practices are designed to assist caregivers in cultivating mindfulness skills through formal and informal exercises, enabling them to integrate these skills into their daily lives. The psychoeducation and group sharing activities within the SSMI aim to boost caregivers’ confidence in managing stress and aid them in devising a plan for ongoing practice. Participants will receive a self-practice toolkit containing teaching materials, such as recordings of guided mindfulness activities, for daily home practice lasting 20 min, facilitated through an online platform. They will be instructed to establish this practice as a daily routine [23, 24]. All instructional content will be closely aligned with dementia caregiving, focusing on topics like responding mindfully to the care recipient to minimize the trigger of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. The sessions will be led by a mindfulness instructor who has undergone 40 h of training in dementia caregiving based on our previous research. Participants will receive weekly mindfulness practice reminders via SMS over an 8-week period. The duration of 8 weeks was chosen based on previous studies indicating that participants tend to establish a regular mindfulness practice habit within this timeframe [13, 14]. Drawing from insights gained in our pilot studies, each SSMI session will consist of 10 to 12 participants to ensure sufficient group interactions between the mindfulness instructor and caregivers. Additionally, caregivers will have access to an online social media platform to share their practice experiences with peers. The interventionist, a psychologist not part of the research team, will address any difficulties or challenges raised on the platform to reinforce skill development. Caregivers will be encouraged to report their daily practice duration in a provided logbook and share their experiences on the platform. An interactive reward chart will be distributed daily via the platform by the research assistant to motivate caregivers in their mindfulness practice. Appreciation messages will be sent to caregivers who achieve the goal of daily mindfulness practice throughout a week.

Ten family caregivers who meet the same sampling criteria as mentioned above will be recruited to provide qualitative feedback from both the caregivers and the mindfulness instructor prior to the proposed RCT. The feedback gathered will be used to make minor refinements to the intervention protocol.

Control condition

As the SSMI is a group-based intervention, an active control group will be implemented to mitigate the socialization and interaction effects that could potentially mask the stress reduction effects of the SSMI. Caregivers in the control group will receive a brief education session on dementia care, structured with the same group size and duration (90 min) as the SSMI sessions. To avoid contaminating the caregiving competency in the control group, a nurse will deliver a concise dementia education segment (15 min) during the session, followed by group sharing and discussions on their daily caregiving experiences. A similar control group was utilized and validated in our previous mindfulness research [13, 14]. Similar to the intervention group, caregivers in the control group will be provided with an educational toolkit covering common health issues in older adults. They will also have access to a social media platform for communication and sharing of caregiving experiences with their peers.

Screening, primary, secondary, and other outcome measures

Screening measure

Caregiving burden

The Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) will be employed as a screening tool to evaluate caregiving stress [20]. It comprises 24 items loaded into five factors: time-dependence burden (5 items, reflecting the burden due to time constraints on the caregiver), developmental burden (5 items, indicating the caregiver’s perception of being “off-time” in personal development compared to peers), physical burden (4 items, representing the caregiver’s experiences of chronic fatigue and physical health deterioration), social burden (5 items, capturing the caregiver’s feelings of role conflict), and emotional burden (5 items, describing the caregiver’s negative emotions towards the care recipient). Caregivers rate their responses on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not descriptive at all) to 4 (highly descriptive), with a higher score indicating a greater level of caregiving burden. The Chinese version of the CBI has been validated in the Chinese caregiving context [25].

Suicidal ideation

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) Screener will be utilized for screening suicidal risks [21]. It consists of six items divided into two subscales: ideation (5 items) and behavioral scales (1 item). Each item is rated with a binary response (yes or no). Participants who answer affirmatively to any of the six items will be excluded from the study. Moreover, the Chinese version of the C-SSRS has been validated in Chinese patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder [26].

Primary outcome

Perceived caregiving stress

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) will be used to measure self-reported caregiving stress [27]. It consists of 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert Scale (0 = never to 4 = very often). The total score ranges from 0 to 40, with a higher score indicating higher perceived stress levels. The Chinese version of the PSS-10 has been validated in various Chinese contexts, with a satisfactory internal consistency of 0.75 in the community-based general population in China and 0.79 among Chinese caregivers [28, 29].

Secondary outcomes

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) will be employed to assess depressive symptoms over a one-week recall period [30]. This scale comprises 20 items, each rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = less than a day, 1 = 1–2 days, 2 = 3–4 days, and 3 = 5–7 days). The total score ranges from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The CES-D has been validated among family caregivers of PWD with an excellent internal consistency of 0.92 [31]. In addition, the Chinese version of the CES-D has been validated in the Hong Kong Chinese population, with an internal consistency of 0.86 and a two-week test-retest reliability of 0.91 [32].

Positive aspects of caregiving

The Positive Aspects of Caregiving Scale (PAC) will be used to measure caregivers’ positive role appraisals [33]. The PAC consists of nine items that load onto two factors: self-affirmation (comprising six items, reflecting the confident and capable self-image derived from the caregiving role) and outlook on life (including three items, indicating enhanced interpersonal relationships and a positive life orientation). Respondents rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with a higher PAC score indicating a more positive caregiving experience. The Chinese version of the PAC has been validated among Chinese dementia caregivers, with an internal consistency of 0.89 [34].

Dyadic relationship

The Dyadic Relationship Scale (DRS) will be employed to evaluate both negative and positive dyadic interactions from the perspectives of care recipients (DRS-patient) and family caregivers (DRS-caregiver) [35]. This scale comprises two versions: the patient version (10 items) and the caregiver version (11 items). Each version includes two subscales: dyadic strain (5 items for caregivers and 4 items for patients) and positive dyadic interaction (6 items for caregivers and 6 items for patients). Participants assess each item on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Higher scores on each scale indicate elevated levels of strain and positive interaction, respectively. The Chinese versions of DRS-patient and DRS-caregiver have been validated among Chinese caregivers, with Cronbach’s α coefficients of 0.82 and 0.83, and two-week test-retest reliabilities of 0.97 and 0.96, respectively [36].

Trait mindfulness

The Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (FFMQ-SF) will be employed to evaluate trait mindfulness [37, 38]. These domains encompass observing (being aware of both internal and external stimuli such as sensations, emotions, thoughts, and visual perceptions), describing (using words to label internal experiences), acting with awareness (paying attention to present activities and avoiding mindlessness), nonjudging (adopting a non-evaluative attitude towards one’s experiences), and nonreacting (allowing thoughts and feelings to come and go without suppressing them). Each domain consists of four items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = very often). The facet score for each domain is computed as the average of the four items, with higher scores (ranging from 1 to 5) indicating increased levels of mindfulness. The Chinese version of the FFMQ-SF has been validated in the Chinese population, with an internal consistency of 0.83 and a two-week test-retest reliability of 0.88 [38].

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) will be used to measure neuropsychiatric symptoms present in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders [39]. Administered by the family caregiver, the NPI comprises various domains including delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression/dysphoria, anxiety, elation/euphoria, apathy/indifference, disinhibition, irritability/lability, and aberrant motor behavior. Each domain is evaluated based on frequency (1 = rarely – less than once per week, 2 = sometimes – about once per week, 3 = often – several times per week but less than every day, 4 = very often – once or more per day) and severity (1 = mild – causing little distress in the patient, 2 = moderate – more disturbing to the patient but can be redirected by the caregiver, 3 = severe – very disturbing to the patient and challenging to redirect). A total score for each domain is calculated by multiplying the frequency and severity ratings. The overall NPI score is derived by summing the scores across all domains, with a higher score indicating more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms. The internal consistency of the Chinese version of the NPI was 0.84 [40].

Health-socio-demographic data

Data will be collected from both family caregivers and care recipients, including: (1) socio-demographic information such as age, gender, marital status, living conditions, and level of education; (2) health-related details (of PWD only? ), including past medical history, activities of daily living, cognitive status, and medication usage; and (3) the utilization of social and caregiving support services, including respite care, daycare centers, and assistance from domestic helpers.

Feasibility-related outcomes

Feasibility-related measures will be implemented to explore the viability of the proposed RCT. To determine eligibility and enrollment, we will analyze the number of eligible participants and the proportion of those who enrol. The attendance rate will be evaluated by analyzing the number and proportion of participants who attend the scheduled sessions. Adherence to self-practice will be assessed by tracking the frequency and duration of mindfulness practice, which will be measured through the number of views and downloads of self-learning materials on an online platform, as well as the duration of practice recorded in a provided logbook on a weekly basis. Additionally, the retention rate will be examined by calculating the number and proportion of participants who successfully complete all assessments at T0, T1, and T2.

Qualitative methods

Focus group interviews will be conducted by a trained research associate experienced in conducting such interviews with caregivers, following the RE-AIM process evaluation framework [41]. This framework encompasses the domains of Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance of the SSMI. Thirty-six participants from the intervention group will be purposively selected to form six focus groups with each comprising six participants. Purposive sampling will be guided by three levels of change in stress experienced by participants post-SSMI: decreased level, no changes, and increased level. Given the likelihood of a limited number of participants experiencing no changes or increased stress levels after the SSMI, all available participants in these categories will be interviewed. The focus group interviews, lasting approximately 1–1.5 h, will be conducted via a semi-structured interview, focusing on the domains of Reach (e.g., motivations for program participation), Effectiveness (e.g., program efficacy), Adoption (e.g., barriers and facilitators to integrating mindfulness into daily life), Implementation (e.g., mindfulness learning and practice indicators), and Maintenance (e.g., strategies for sustaining mindfulness practice in the future) of the SSMI. Informed consent will be obtained prior to audio-recording the focus group interviews, which will subsequently be transcribed verbatim. According to G Guest, E Namey and K McKenna [42], conducting six focus groups with a total of 36 participants should be sufficient to reach data saturation. If data saturation is not reached after these initial six focus groups, the research team will consider recruiting additional participants for further focus group interviews.

Methods to protect against sources of bias

Randomization and allocation

The unit of randomization in this study will be the participant, and the randomization process will utilize computer-generated group assignment with a 1:1 allocation ratio by an independent statistician. To increase the likelihood of achieving balanced group sizes, permuted block randomization with a block size of 4 will be implemented, using the following allocation concealment mechanism. Participants will be informed of their group allocation through NGOs, using opaque sealed envelopes. The group allocation lists will be kept concealed from the researchers, staff at the elderly centers, and outcome assessors. The trial research team will only have access to the blinded dataset.

Sample size

The sample size estimation is based on the level of perceived stress, which is the primary outcome measure. Given the utilization of a simplified version of mindfulness training in the proposed RCT, which is distinct from the protocol employed in our previous pilot studies involving the traditional MBI lasting 8 weeks, the effect size was derived from existing literature on the impact of SSMIs on psychological outcomes [19, 43, 44]. The effect sizes reported in these studies varied from 0.32 to 0.68. We adopted a conservative effect size of 0.40 (small to moderate) to detect the mean difference in stress reduction between the intervention and control groups. Considering a 20% attrition rate observed at the 6-month mark in our pilot study, a sample size of 160 family caregivers (80 per group) is deemed necessary to achieve 80% power at a two-sided 5% level of significance.

Ethical considerations

To our knowledge, there are no known risks associated with the SSMI or the control conditions for both family caregivers and care recipients participating in this study. Ethics approval for the study has been obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Ref.: HSEARS20230928006) and access approval will be obtained from the study venues. The research team will comply with all requirements involving human subjects outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and subsequent updates, as well as the Good Clinical Practice Guideline. To ensure participant safety and protection from harm resulting from the intervention, a data monitoring committee comprising three independent experts specializing in mental health nursing and gerontology will be established. To protect the confidentiality of participants, all data will be securely stored and will be destroyed five years after the publication of the trial results.

Intervention fidelity control

The SSMI sessions will be audio-recorded for intervention fidelity checks. A fidelity checklist will be developed based on the recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium [45]. An independent mindfulness researcher will listen to the recordings and compare them against the fidelity checklist. According to the NIH Behavior Change Consortium, achieving a fidelity rate exceeding 90% will be deemed acceptable [45].

Data analyses

Statistical analyses

SPSS version 25.0 will be utilized for data analysis in this study. An intention-to-treat analysis approach will be employed. Descriptive statistics will be computed for the demographic data. The normality assumptions for the variables will be assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To compare similarities in socio-demographic and baseline outcome variables between the two study groups, independent sample t-tests (2-tailed) or Chi-square tests will be conducted. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) will be utilized to investigate the study outcomes across the three time points (T0, T1, and T2) between the intervention and control groups. In the GEE analysis, the mean total scores of the psychological health outcomes will serve as the dependent variables, while the independent variables will include group, time points, and the interaction between group and time. If a statistically significant interaction effect is detected, indicating that the group differences depend on the time point, estimated marginal means will be computed to further probe the nature of the interaction. Missing data will be handled within the GEE model using maximum likelihood estimation without using other imputation methods like group means replacement or last observation carried forward. Given the absence of known covariates in this study, an assessment of homogeneity will be conducted to identify any potential covariates influencing the outcomes. Possible covariates such as age, gender, education level, compliance, and psychiatric comorbidity will be put forward as covariates in a secondary analysis. All data analyses will be conducted as two-tailed with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Qualitative analyses

Since the focus group interviews aim to conduct process evaluation, which is descriptive in nature, verbatim transcriptions will be analyzed inductively using a content analysis approach following the steps outlined by HF Hsieh and SE Shannon [46]. Initially, two qualitative researchers from the team will repeatedly read the transcripts. After conducting double-coding and collaborative discussions, initial codes will be organized into themes and sub-themes related to the strengths, weaknesses, barriers, and facilitators of the SSMI. The research team acknowledges their own presumptions regarding the strengths, weaknesses, barriers, and facilitators based on previously conducted 8-week MBI studies. Therefore, preliminary findings will be shared with the focus groups in a follow-up interview to allow participants to challenge these presumptions and provide specific information on the SSMI. Subsequently, the themes and sub-themes will be collaboratively discussed and reviewed with other team members to present a structured analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, barriers, and facilitators of the SSMI. Other research team members are expected to question and discuss any presumptions regarding the strengths, weaknesses, barriers, and facilitators of the MBI and to uncover the unique aspects of the SSMI. The researchers will analyze the data until the point of data saturation is reached, when no new findings emerged. The findings will be presented narratively in a thematic format. The research team has successful experience in conducting various types of collaborative qualitative analysis [47]. To ensure the trustworthiness of the qualitative study, a third researcher proficient in qualitative content analysis will evaluate the study’s compliance to the guidelines by YS Lincoln and EG Guba [48] for establishing credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility will be maintained by challenging the research team’s presumptions through collaborative content analysis and by achieving data saturation. Dependability will be ensured by seeking participants’ feedback on the preliminary findings of the content analysis. For confirmability, the research team will thoroughly explore any unique aspects of the SSMI that were not identified in other MBI modalities previously studied by the team. To enhance transferability, the aim is to achieve data saturation and support thematic findings with representative quotes or stories from participants.

Discussion

With an aging population and an increased prevalence of dementia, an increase in the number of family caregivers for PWD is anticipated. Due to the demanding nature of caregiving tasks, the unpredictable symptoms associated with the illness, and limited time for other social activities, caregivers often experience significant stress levels and are at increased risk of developing various physical and psychological conditions, including depression, insomnia, and compromised immune function [5]. Therefore, it is imperative to provide timely interventions to alleviate caregiving stress for this vulnerable population. MBIs offer a promising approach to reduce stress in family caregivers of PWD [11]. However, they may not be a cost-effective strategy to accommodate the growing number of family caregivers [13, 14]. Additionally, family caregivers, often preoccupied with caregiving duties, may encounter challenges in attending traditional MBIs. An alternative approach could be the SSMI, which empowers caregivers by providing support, resources, and skills in a single session to help them manage caregiving stress. However, further evidence is needed to contribute to the evidence base of the SSMI for this population. Therefore, this proposed RCT can establish the effectiveness of the SSMI in empowering caregivers to reduce caregiving stress.

A potential limitation of this proposal may arise from the unique characteristics of the caregiver population. Caregivers, who are often heavily involved in caregiving responsibilities as well as work-related duties, might encounter challenges in attending the program, adhering to mindfulness self-practice, or completing follow-up assessments [49]. To address potential enrollment challenges, we have partnered with two NGOs that operate five elderly centers, serving over 2,000 individuals diagnosed with dementia and their caregivers. To promote adherence, participants will receive SMS reminders for their weekly mindfulness practice. Additionally, we have established an online social media platform to encourage participants to engage in practice and share their experiences with peers. If there are any challenges or difficulties reported by the caregivers, our interventionists will offer timely support through this platform. Moreover, an interactive chart will be shared daily via the platform to enhance motivation for practice with appreciation messages sent to those who fulfill the goal of daily mindfulness practice throughout the week. To account for potential attrition, we have conservatively estimated a 20% attrition rate to ensure that the study will maintain sufficient statistical power (1 − β = 80%, p < 0.05) to detect significant changes in our outcome measures.

Despite the limitations, the proposed study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first RCT to employ the SSMI in reducing caregiving stress for this vulnerable group. Compared to traditional MBIs, the SSMI is a flexible and cost-effective method that can be accommodated for caregivers, who are often constrained by their caregiving duties. Another strength is the comprehensive nature of our evaluation, which will not be limited to psychometric scales alone. The feasibility assessment for the SSMI could serve as the groundwork for both medium- and long-term implementations, in which enrollment and attendance rates, adherence to self-practice, and retention rates are critical aspects of MBIs that must be carefully considered [50]. By utilizing the RE-AIM process evaluation framework [41], which focuses on the domains of Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance, we can gain unique insights into the sustainability of the SSMI and allow us to further refine the SSMI for this population.

Anticipated results and research knowledge translation strategies

Results will be disseminated through non-governmental organizations that provide gerontological services, media channels, peer-reviewed conferences, journal articles, and special interest groups such as caregiver support groups. The principal investigators, co-investigators, and collaborators on this proposal will provide support and networking for other interested parties who wish to implement similar interventions for their communities. The study results will also be disseminated to stakeholders such as healthcare professionals, healthcare administrators, and policymakers in Hong Kong.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CBI

Caregiver Burden Inventory

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale

- DRS

Dyadic Relationship Scale

- FFMQ-SF

Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- ICC

intra-class correlations

- MBCT

mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

- MBI

mindfulness-based intervention

- NGO

non-governmental organization

- NPI

Neuropsychiatric Inventory

- PAC

Positive Aspects of Caregiving Scale

- PSS-10

Perceived Stress Scale

- PWD

people with dementia

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SPIRIT

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials

- SSI

single-session intervention

- SSMI

single-session mindfulness-based intervention

Authors’ contributions

PPKK, KLC, SHZ, JG, WCC, JYWL, DSKC, KHMH had the initial idea and developed the original study plan. PPKK, DLLL and APLT drafted the intervention protocol and manuscript. PPKK, DLLL and APLT supported the development and implementation of the interventions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This trial is supported by the Health Medical and Research Fund (No. 21221491). The Hong Kong Polytechnic University takes responsibility for the research. The sponsor and funders had no role in study design; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. They do not have ultimate authority over any of these activities.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Ref.: HSEARS20230928006). All participants will give their consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Brayne C, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO): Ageing and health. 2022. Available from: [https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health]. [Cited: April 8 2024].

- 3.Alzheimer’s Disease International: World Alzheimer Report. 2018. 2018. Available from: [https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2018.pdf]]. [Cited: April 8 2024].

- 4.Wu YT, Ali GC, Guerchet M, Prina AM, Chan KY, Prince M, Brayne C. Prevalence of dementia in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):709–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson TJ, Lee SJ, Berg-Weger M, Grossberg GT. Caregiver health: health of caregivers of Alzheimer’s and other dementia patients. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(7):367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindeza P, Rodrigues M, Costa J, Guerreiro M, Rosa MM. Impact of dementia on informal care: a systematic review of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMJ Support Palliat Care.; 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zarit SH, Polenick CA, DePasquale N, Liu Y, Bangerter LR. Family support and caregiving in middle and late life. APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: applications and broad impact of family psychology. Volume 2. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2019. pp. 103–19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Fredrickson BL. Positive reappraisal mediates the stress-reductive effects of Mindfulness: an upward spiral process. Mindfulness. 2011;2(1):59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng S-T, Li K-K, Losada A, Zhang F, Au A, Thompson LW, Gallagher-Thompson D. The effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for informal dementia caregivers: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2020;35(1):55–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kor PPK, Chien WT, Liu JYW, Lai CKY. Mindfulness-based intervention for stress reduction of Family caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2018;9(1):7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kor PPK, Liu JYW, Chien WT. Effects of a modified mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for family caregivers of people with dementia: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;98:107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kor PPK, Liu JYW, Chien WT. Effects of a modified mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for family caregivers of people with dementia: a Randomized Clinical Trial. Gerontologist. 2021;61(6):977–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strohmaier S. The relationship between doses of mindfulness-based programs and depression, anxiety, stress, and mindfulness: A dose-response meta-regression of randomized controlled trials. In., vol. 11. Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 1315–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell A. Single-Session approaches to Therapy: Time to review. Austr N Z J Fam Ther. 2012;33(1):15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schleider JL, Weisz JR. Little treatments, Promising effects? Meta-analysis of single-Session interventions for Youth Psychiatric problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(2):107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertuzzi V, Fratini G, Tarquinio C, Cannistrà F, Granese V, Giusti EM, Castelnuovo G, Pietrabissa G. Single-session therapy by appointment for the treatment of anxiety disorders in youth and adults: a systematic review of the literature. Front Psychol. 2021;12:721382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin J, Tang L, Dishman RK. The effects of a single session of mindful exercise on anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ment Health Phys Act. 2021;21:100403. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novak M, Guest C. Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. Gerontologist. 1989;29(6):798–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, et al. The Columbia-suicide severity rating scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenzie C, Pace N, Mann R, Schley C, Parker A. Brief interventions in youth mental health toolkit: a clinical resource for headspace centres. Parkville, Victoria: Orygen; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgess EE, Selchen S, Diplock BD, Rector NA. A brief mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) intervention as a Population-Level strategy for anxiety and depression. Int J Cogn Ther. 2021;14(2):380–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee EK, Wong B, Chan PHS, Zhang DD, Sun W, Chan DC, Gao T, Ho F, Kwok TCY, Wong SY. Effectiveness of a mindfulness intervention for older adults to improve emotional well-being and cognitive function in a Chinese population: a randomized waitlist-controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;37(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Chou K-R, Jiann-Chyun L, Chu H. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the caregiver burden inventory. Nurs Res. 2002;51(5):324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji Y, Liu X, Zheng S, Zhong Q, Zheng R, Huang J, Yin H. Validation and application of the Chinese version of the Columbia-suicide severity rating scale: suicidality and cognitive deficits in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2023;342:139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang F, Wang H, Wang Z, Zhang J, Du W, Su C, Jia X, Ouyang Y, Wang Y, Li L, et al. Psychometric properties of the perceived stress scale in a community sample of Chinese. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao T, Zhu F, Wang D, Liu X, Xi SJ, Yu Y. Psychometric validation of the perceived stress scale (PSS-10) among family caregivers of people with schizophrenia in China. BMJ Open. 2023;13(11):e076372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radloff LS, The CES-D, Scale. A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ying J, Yap P, Gandhi M, Liew TM. Validity and utility of the Center for epidemiological studies depression scale for detecting depression in family caregivers of persons with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2019;47(4–6):323–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chin WY, Choi EPH, Chan KTY, Wong CKH. The psychometric properties of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in Chinese primary care patients: factor structure, construct validity, reliability, sensitivity and responsiveness. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarlow BJ, Wisniewski SR, Belle SH, Rubert M, Ory MG, Gallagher-Thompson D. Positive aspects of caregiving: contributions of the REACH Project to the development of New measures for Alzheimer’s caregiving. Res Aging. 2004;26(4):429–53. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lou VW, Lau BH, Cheung KS. Positive aspects of caregiving (PAC): scale validation among Chinese dementia caregivers (CG). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(2):299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sebern MD, Whitlatch CJ. Dyadic relationship scale: a measure of the impact of the provision and receipt of Family Care. Gerontologist. 2007;47(6):741–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeng D, Yang C, Chien WT. Testing the psychometric properties of a Chinese version of Dyadic relationship scale for families of people with hypertension in China. BMC Psychol. 2022;10(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou J, Wong SY, Lo HH, Mak WW, Ma HS. Validation of a Chinese version of the five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in Hong Kong and development of a short form. Assessment. 2014;21(3):363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The neuropsychiatric inventory. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leung VP, Lam LC, Chiu HF, Cummings JL, Chen QL. Validation study of the Chinese version of the neuropsychiatric inventory (CNPI). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(8):789–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, Rabin B, Smith ML, Porter GC, Ory MG, Estabrooks PA. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health. 2019;7:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guest G, Namey E, McKenna K. How many focus groups are Enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods. 2017;29(1):3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mandlik GV, Siopis G, Nguyen B, Ding D, Edwards KM. Effect of a single session of yoga and meditation on stress reactivity: a systematic review. Stress Health. 2024;40(3):e3324. 10.1002/smi.3324. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Strohmaier S, Jones FW, Cane JE. One-session mindfulness of the breath meditation practice: a randomized controlled study of the effects on State hope and state gratitude in the general population. Mindfulness. 2022;13(1):162–73. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, Ogedegbe G, Orwig D, Ernst D, Czajkowski S. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):443–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho SS, Stenhouse R, Snowden A. It was quite a shock’: a qualitative study of the impact of organisational and personal factors on newly qualified nurses’ experiences. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(15–16):2373–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glueckauf RL, Ketterson TU, Loomis JS, Dages P. Online support and education for dementia caregivers: overview, utilization, and initial program evaluation. Telemed J E Health. 2004;10(2):223–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salvo V, Kristeller J, Montero Marin J, Sanudo A, Lourenço BH, Schveitzer MC, D’Almeida V, Morillo H, Gimeno SGA, Garcia-Campayo J, et al. Mindfulness as a complementary intervention in the treatment of overweight and obesity in primary health care: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.