Abstract

Glioma is a deadly form of brain cancer, and the difficulty of treating glioma is exacerbated by chemotherapeutic resistance developed in the tumor cells over time of treatment. siRNA can be used to silence the gene responsible for the increased resistance, and sensitize the glioma cells to drugs. Here, iron oxide nanoparticles functionalized with peptides (NP-CTX-R10) were used to deliver siRNA to silence O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) to sensitize tumor cells to alkylating drug, temozolomide (TMZ). The NP-CTX-R10 could complex with siRNA through electrostatic interactions, and was able to deliver the siRNA to different glioma cells. The targeting ligand chlorotoxin (CTX) and cell penetrating peptide polyarginine (R10) enhanced the transfection capability of siRNA, to a level comparable to commercially available Lipofectamine. The NP-siRNA was able to achieve up to 90% gene silencing. Glioma cells transfected with NP-siRNA targeting MGMT showed significantly elevated sensitivity to TMZ treatment. This nanoparticle formulation demonstrates the ability to protect siRNA from degradation and to efficiently deliver the siRNA to induce therapeutic gene knockdown.

Keywords: siRNA, functional peptide, chlorotoxin, cell-penetrating peptide, glioma, iron oxide nanoparticle

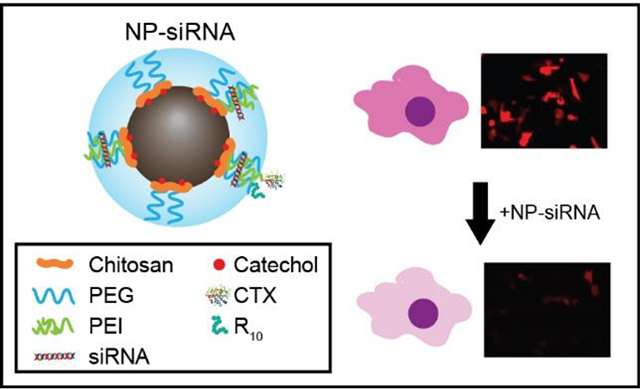

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Glioma is an aggressive cancer of glial cells, and is the most common type of primary brain tumor. Its genetic heterogeneity, invasive nature, prolonged proliferation, and rapid growth confound the management of glioma, which results in extremely poor prognosis in patients.1–3 Current treatment modalities for glioma includes aggressive neurosurgery followed by concurrent radiation and chemotherapy with alkylating agents such as temozolomide (TMZ).4–6 Despite these treatment methods, the overall survival rate of glioma remains at less than 35%, and mean survival rate for glioblastoma, the most aggressive form of glioma, is 8 to 15 months.7,8 Studies have shown that one of the barriers to effective chemotherapy is the intrinsic or acquired resistance to the alkylating agents in glioma cells.9,10 Alkylating agents such as temozolomide (TMZ) alkylate the O6 position of guanine in DNA of cancer cells, inducing mutation and ultimately, their death. However, endogenous enzymes such as O6-methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT) can ‘repair’ the damage caused by alkylating agents, counteracting their therapeutic effect.11–13 Hence, suppression of MGMT activity and subsequent mitigation of chemotherapeutic resistance is an ideal target to improve chemotherapeutic efficacy and patient survival.

Recent advances in oncogenomics revealed new possibilities of identifying and regulating specific genes for cancer therapy.14–16 Among these new opportunities, delivery of short interfering RNA (siRNA) that can silence gene expression in a highly specific manner is a potent and highly effective approach to combat glioma by targeting genetic pathways that contribute to invasion, tumorigenesis, and therapy resistance.17–19 As a promising and effective gene regulator, siRNA, a short double strand RNA with around 21 base pairs, suppresses the expression of target genes, which can allow elucidation of novel cellular & molecular mechanisms as well as inhibit disease-related genes.20–22 The sequence of a therapeutic siRNA is specific to the mRNA sequence of the target gene, eliciting little to no off-site effects.23–25 Furthermore, siRNA is not known to exhibit genotoxic effects, as it interferes only with the translation of mRNA to knockdown the target gene.26,27 Delivery of MGMT-targeting siRNA to glioma cells presents an avenue for safe and effective regulation of therapeutic resistance.

Over the past few years, many researchers have reported therapeutic siRNA candidates and their clinical potentials for the treatment of devastating diseases including brain tumors.28–30 However, its clinical translation is hindered by challenges such as poor intracellular delivery and in vivo stability. Thus, the development of proper carriers could greatly elevate therapeutic effects of RNA therapeutics and accelerate their pharmaceutical development. Nanoparticles are an attractive platform for siRNA delivery due to their small size and flexible surface chemistry that can be easily formulated for specific applications. Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs), in particular, have often been used in biological applications due to their excellent biocompatibility and degradability.22,31,32 In addition, the superparamagnetism exhibited by the Fe3O4 core allows them to be utilized as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).33 Previously, we have shown that short-chain chitosan functionalized with polyethylene glycol (PEG) could be used to synthesize chitosan-coated IONPs via a simple co-precipitation method.34,35 Due to its small size of IONPs, the polymers could passivate the surface of iron oxide cores that were precipitated from iron chlorides and titrated base. The coprecipitation of nanoparticles presents advantages to other methods of nanoparticle synthesis such as thermal decomposition as it does not require harsh reaction conditions such as high temperature and use of organic solvents, and can be scaled up with relative ease. The resulting nanoparticles have demonstrated good dispersion in aqueous environments, and have been used to deliver chemotherapeutic agents, as well as in MRI applications.34–36 Versatile surface properties of IONPs can be achieved through application of polymeric coatings. Specifically, cationic polymers such as polyethyleneimine (PEI) has been used to deliver therapeutic nucleic acids including siRNA,37,38 mRNA,39,40 and DNA.41–44 PEI can form polyplexes with the negatively charged nucleic acid and has shown to be an effective transfection agent. While the reported cytotoxicity of PEI, especially for PEI of high molecular weights, has hindered its clinical translation, it has been shown to be mitigated when PEI is conjugated with biocompatible polymers, such as chitosan.45,46

In order to impart further functionality to the IONPs, short peptides such as cell targeting peptides (CTPs) and cell penetrating peptides (CPPs) can be conjugated onto the surface of IONPs through the chemical functional groups on the polymeric coating.47–49 In this study, we present a IONP-based system for delivery of therapeutic siRNA to glioma cells. This delivery system is functionalized with two peptides: chlorotoxin and polyarginine to enable its dual function. Chlorotoxin (CTX), a 36-mer peptide derived from scorpion venom, has shown to preferentially bind to matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) surface protein which is overexpressed on the surface of glioma cells.50–54 Arginine-rich peptides have been explored as CPPs due to their ability to interact with cell membranes.55,56 Recent studies have shown that in addition to cell-penetration, arginine-rich CPPs can assist endosomal escape, which would allow siRNA to escape endosomal entrapment and degradation, and become available in the cytosol to form the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC).57,58 The IONP is synthesized by a coprecipitation method using a catechol-chitosan-PEG-PEI copolymer. The catechol group, which has high affinity for iron, increases the stability of the nanoparticle by improving the interaction between the polymer coating and the iron oxide core. The surface of the IONP is then conjugated with functional peptides CTX and polyarginine (n = 10) (R10) to improve its function as a siRNA transfection vector. The resulting nanoparticles (NP-CTX-R10) were able to effectively deliver siRNA, as demonstrated by silencing of red fluorescent protein (RFP). The NP-CTX-R10 were then used to deliver siRNA in order to silence MGMT, and improve the therapeutic effect of TMZ on glioma cells. This unique design harnesses the functionality of two different functional peptides, and the synergistic effect of the peptides was demonstrated on glioma cells.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Materials

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise specified. The heterobifunctional linker 2-iminothiolane (Traut’s reagent) was purchased from Molecular Biosciences (Boulder, CO). Zeba™ Spin Desalting Columns, temozolomide (TMZ), poly(arginine) (R10), and heterobifunctional linker succinimidyl-([N-maleimidopropionamido]-(ethyleneglycol)12) ester (smPEG12) were purchased from Thermo Scientific Inc. (Rockford, IL). Chitosan (2.3k MW) was obtained from Acmey Industrial (Shanghai, China). Anti MGMT siRNA (siMGMT) was purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). S-200 chromatography resin was purchased from GE Healthcare (Chicago, IL). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and antibiotic–antimycotic were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA). Chlorotoxin (CTX) was purchased from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Seattle, WA). Plasmid pDsRed-Max-N1 was purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA).

2.2. Preparation and conjugation of IONPs with functional peptides

Catechol-chitosan-PEG (CCP) coated IONPs were synthesized via co-precipitation method as previously reported.43 Briefly, purified chitosan (2.3k MW) and aldehyde-activated methoxy PEG were reacted via reductive amination to produce a PEG-grafted chitosan copolymer. The copolymer was functionalized with catechol group by reacting 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde and the copolymer via reductive amination to obtain CCP. Polyethyleneimine (PEI) (800, 10k, 25k MW) functionalized with Traut’s reagent and CCP functionalized with succinimidyl iodoacetate were reacted to form CCP-PEI copolymer via thioester linkage.

To synthesize the nanoparticles (NP), CCP (25 mg), iron (II) chloride (9 mg), and iron (III) chloride (15 mg) were dissolved in degassed deionized water (2.18 mL). Ammonia solution (36%) was titrated into the solution while being sonicated and stirred vigorously for 25 min under N2 atmosphere. The ammonia was evaporated from the solution by continued sonication and stirring for addition 20 min. Aqueous solution of CCP-PEI (50 mg) was added to the resulting intermediate nanoparticle solution and cured for 16 h at room temperature. The resulting NP were purified via size exclusion chromatography using S-200 resin.

To modify the NP with peptides, the amine groups on the surface of NP were activated using smPEG12. Chlorotoxin (CTX) and poly(arginine) (R10) were activated with Traut’s reagent. The activated peptides were added to the maleimide-functionalized NP and reacted for 2 h at room temperature. The resulting NP-CTX-R10 was purified via size exclusion chromatography using S-200 resin.

2.3. Preparation of nanoparticle-siRNA complex

NP-siRNA complex was prepared through titration of siRNA solution into a solution of NP-CTX-R10. The sequence of siRFP used was 5’-CCUUCAUCUACCACGUGAAdTdT-3’ (sense strand). NP-CTX-R10 was dispersed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4). siRNA solution in PBS was prepared, and was titrated using a peristaltic pump into the NP-CTX-R10 solution under constant stirring, at various NP:siRNA ratios. The resulting NP-siRNA were transferred to sterile PBS using a 0.2 μm syringe filter.

2.4. Characterization of NP-CTX-R10 and NP-siRNA complex

NP-CTX-R10 and NP-siRNA were prepared in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) to measure the hydrodynamic size and zeta potential with a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (Worcestershire, U.K.). In order to assess the stability of the NP-CTX-R10, the nanoparticles were suspended in PBS and DMEM, and stored at 4°C and 37°C, respectively. The hydrodynamic size of the nanoparticles was measured daily for 14 days. The morphology of the NP-CTX-R10 was analyzed by a FEI Tecnai G2 F20 transmission electron microscope (TEM) (Hillsboro, OR) operating at 200 kV. Samples for FTIR analysis were prepared by lyophilizing the nanoparticles. Pellets consisting of potassium bromide and the lyophilized nanoparticles (0.2 wt%) were prepared. FTIR spectra were obtained using a Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer. Polymer samples for NMR analysis were prepared by dissolving polymer and trimethylsilylpropanoic acid standard in D2O. NMR spectra were obtained using a Bruker Avance 300 spectrometer operating at 300.13 MHz (1H) and 298K (number of scans 64, acquisition time 3.9 s, delay (D1) = 2 s).

2.5. siRNA transfection study

C6 rat glioma cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic at 37ºC and 5% CO2, and were seeded at 35,000 cells per well in a 48-well plate. The cells were transfected with pDsRed-Max for expression of RFP using Lipofectamine 3000 transfection agent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 24 h, the cells were then transfected with siRFP using Lipofectamine 3000, NP, or NP-CTX-R10. After 48 h, the cells were washed with PBS, and the fluorescence intensity of RFP was analyzed using fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. The extent of gene silencing was calculated by comparing the relative fluorescence intensities of the treated cells to that of control cells without siRFP transfection. Only RFP-expressing subsets in each population, as analyzed through flow cytometry, were analyzed for the RFP intensity. The experiment was repeated with SF763 and U87 human glioma cells using the same method.

2.6. MGMT knockdown and evaluation of resistance to TMZ

MGMT-proficient C6 cells and SF763 cells were seeded at 35,000 cells per well in a 48-well plate. The cells were transfected with siMGMT using Lipofectamine 3000 and NP-CTX-R10. Transfection with siRFP was used as a control to observe target-specific effects. After 48 h, the MGMT expression levels were analyzed using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). RNA was extracted from the cells using the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Germantown, MD). cDNA was prepared using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA), which was then used as a template for PCR. Rat and human β-actin were used as a reference gene for C6 and SF763 cells, respectively. SYBR Green PCR Master mix (Bio-Rad) was used for template amplification with a primer for each of the transcripts in a Bio-Rad CFX96 RT-PCR detection system. Solutions of 10 μL containing 0.5μM of primers, 2 ng mL−1 of cDNA, and SYBR Green Master mix according to manufacturer instruction were placed in a thermal cycler. Thermocycling was performed under the following conditions: 95°C for 2 min, 40 cycles of denaturation (15 sec, 95°C), annealing (30 sec, 56°C), and extension (30 sec, 72°C).

For western blot assay, transfected cells were collected, washed with PBS, then lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The lysate was diluted 1:1 with Laemmli sample loading buffer. After heating at 100°C for 10 min, 20 μL of samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated in 5% BSA in TBST (Tris-buffered saline + 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h, then incubated overnight at 4°C with 1 μg mL−1 antibody against MGMT or β-actin in TBST. The membranes were then washed with TBST three times, and incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG diluted 10 μL in 20 mL TBST. Antibody binding was visualized by chemiluminescence and quantified using a ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad).

To evaluate the effect of MGMT knockdown on the chemoresistance of glioma cells, MGMT-proficient C6 and SF763 cells were seeded at 35,000 cells per well in a 48 well plate. After 24 h, the cells were transfected with siMGMT as described above. After 48 h, the cells were then trypsinized, and then transferred to a 96-well plate at 10,000 cells per well. TMZ was added to the cell culture media at various concentrations to obtain final concentrations ranging from 0 to 500 M TMZ. After 48 h, Alamar blue assay was used to evaluate cell viability according to manufacturer’s protocol.

3. Results

3.1. Design and preparation of peptide modified IONP

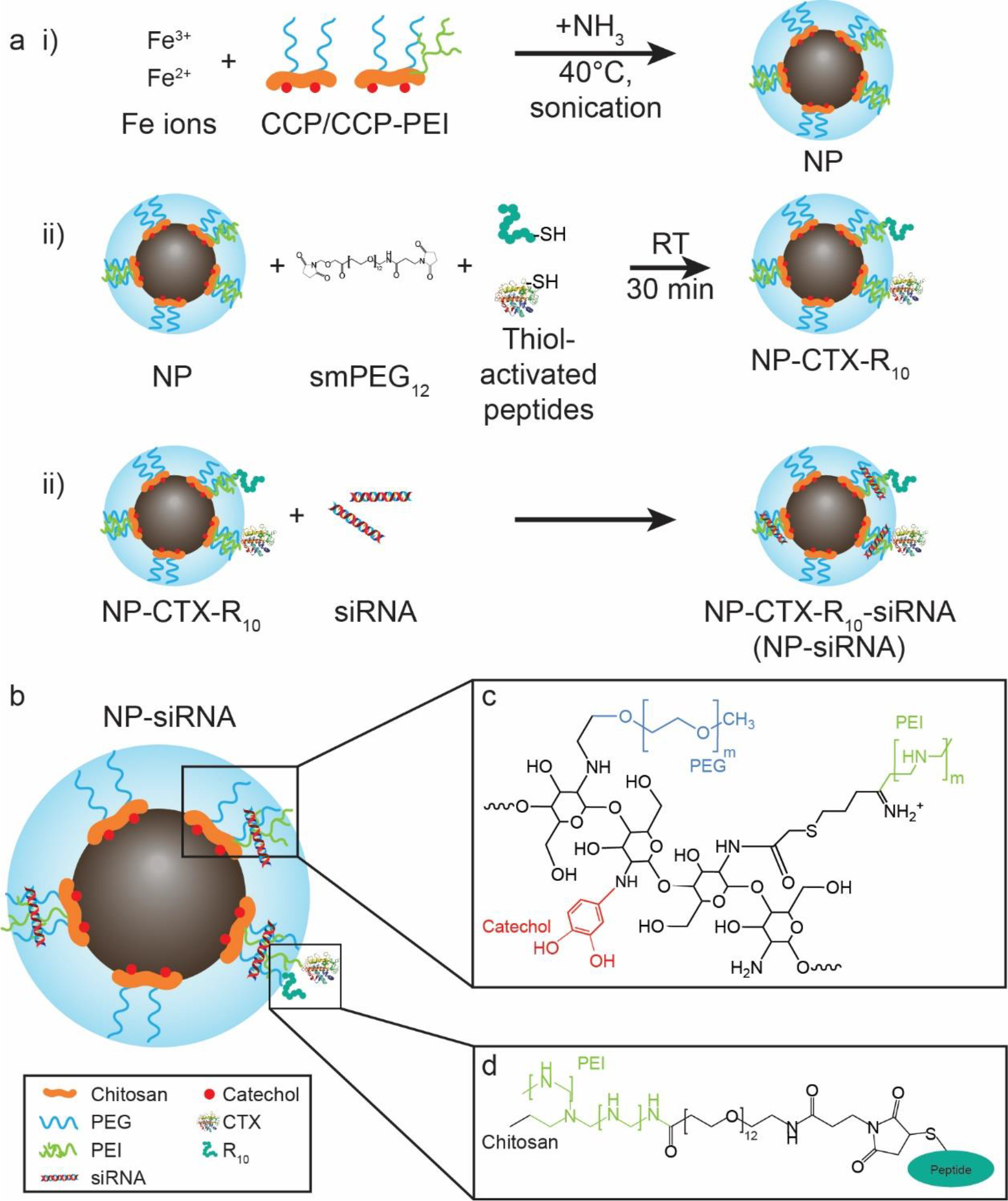

The IONP system is based on coprecipitation of iron oxide core protected by a biocompatible copolymer. The schematic representation of the IONP conjugated with peptides is presented in Figure 1a. Cationic polymer PEI confers a net positive surface charge to the nanoparticle, which facilitates electrostatic attraction between the nanoparticle surface and the negatively charged phosphate backbone of the siRNA. The amine-rich PEI also acts as conjugation sites for the peptides. Figure 1b shows the schematic diagram of the complex formed between the IONP and siRNA through electrostatic interaction. As shown in Figure 1c, the chitosan backbone is grafted with PEG for steric stability, catechol for affinity to the iron oxide surface, and PEI for the positive charge. The peptides CTX and R10 contain amine groups that are functionalized with Traut’s reagent to form thiol groups, which were then linked to the amine groups on PEI using amine- and thiol-reactive smPEG12, as shown in Figure 1d.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for the preparation of NP-CTX-R10. a) Synthesis procedure for the NP and NP-siRNA complex. i) Ferric and ferrous ions and catechol-chitosan-PEG(-PEI) (CCP/CCP-PEI) polymers are mixed and sonicated at 40°C, with continuous titration of ammonia to synthesize the base NPs. ii) CTX and R10 are thiol-activated using Traut’s reagent and are conjugated onto the surface of the NP using succinimidyl-maleimide-PEG linker. iii) The peptide-modified NPs are complexed with siRNA through electrostatic interaction. b) A schematic diagram of the siRNA delivery vector design. c) Chemical structure of CCP-PEI copolymer. d) Detailed structure of the linkage between CCP-PEI and conjugated peptide.

3.2. Physicochemical characterization of NP-siRNA

Physical and chemical characterization of the NPs were performed to verify the structure of NP-siRNA complex, and to determine if the characteristics of the nanoparticles are suitable for biological application. TEM was used to analyze the size and morphology of the iron oxide core of the nanoparticles. The core was observed to be roughly spherical, and the average diameter was measured to be 4.7 ± 1.1 nm. (Figure 2a) The lattice fringe was measured to be 0.29 nm, which corresponds to the d-spacing of the (200) planes in Fe3O4. The planar spacings measured via selected area electron diffraction further demonstrated that Fe3O4 phase was present in the NP core. (Figure 2c and Table 1)

Figure 2.

Physicochemical characterization of NP, NP-CTX-R10, and NP-siRNA. a) TEM image and HR-TEM image (inset) of NP. (Scale bar = 20 nm, 1 nm, respectively)) b) Size distribution of iron oxide cores. (n=36) c) Selected area electron diffraction pattern of NP. (Scale bar = 2 nm−1) d) 1H-NMR spectra of CCP, PEI, and CCP-PEI. The methoxy hydrogens on PEG (I) and the aromatic hydrogens on catechol (II) were used to determine the extent of grafting on the chitosan. The characteristic peaks of PEI (III) were used to validate the presence of PEI on the CCP-PEI copolymer. e) FTIR spectra of NP and NP-CTX-R10. f) Hydrodynamic size distributions of NP, NP-CTX-R10, and NP-siRNA in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4). g) Average hydrodynamic size of NP in PBS (4°C) and DMEM (37°C) over 14 days. h) Zeta potential distributions of NP, NP-CTX-R10, and NP-siRNA. h) Zeta potential distributions of NP, NP-CTX-R10, and NP-siRNA.

Table 1.

Diffraction data d-spacings in Å, based on the rings (Figure 2c) and standard atomic spacing for Fe3O4

| n-th ring from center | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Calculated d-spacing (Å) | 2.94 | 2.54 | 2.10 | 1.72 | 1.62 | 1.49 |

| Powder diffraction values43 | 2.96 | 2.54 | 2.11 | 1.74 | 1.63 | 1.50 |

The composition of the CCP-PEI copolymer was varied to explore the effect of the molecular weight of PEI on the physicochemical properties of the NP. PEI of various molecular weight (800, 10k, 25k g mol−1) were conjugated onto CCP, and were used to synthesize NP. The conjugation of PEI onto the CCP was confirmed by observation of increased intensity in the N-H bend peak in the FTIR spectra (Figure S1a in Supporting Information). Dynamic light scattering was used to measure the hydrodynamic size of the NP synthesized with varying PEI MW. NP containing 800 MW PEI exhibited hydrodynamic size of 25.22 nm, while NP containing 10k PEI and 25k PEI showed hydrodynamic size of 29.91 and 30.37 nm (Figure S1b in Supporting Information). While the hydrodynamic sizes were largely unaffected by the difference in the molecular weight of PEI, the zeta potentials of the NP varied significantly. The zeta potentials of the NPs increased with the molecular weight of PEI used, and were measured to be 8.92, 18.2, and 23.1 mV for 800, 10k, and 25k PEI used, respectively (Figure S1c in Supporting Information). The molecular weight of PEI used to synthesize the CCP-PEI copolymer did not lead to substantial changes in the hydrodynamic size of the NP or formation of aggregates; however, by increasing the molecular weight of PEI, greater zeta potential values were measured on the resulting NP. The zeta potential measurements suggest that the 10k MW is the optimal size of the PEI for applications in siRNA transfection, as NPs with low zeta potential will not be able to efficiently condense siRNA, while NPs with zeta potential that is too high can lead to delay in dissociation of siRNA from PEI, as well as cause cytotoxicity.59 Hence, NP containing 10k MW PEI was used in the optimization of NP-siRNA complexation.

The NP-siRNA complexes were formed by titrating siRNA solution into NP solution under constant stirring. Thus, the parameters such as concentration and reaction ratio used in this mixing process can affect the size of the resulting complex. The initial concentration of NP did not have a significant effect on the final size of the NP-siRNA complex as it was varied from 0.125 to 1 mg Fe mL−1 (Figure S2a in Supporting Information). However, when the feed siRNA concentration was increased from 5 to 50 μM, the hydrodynamic size increased from 31.2 to 42.7 nm (Figure S2b in Supporting Information). And finally, decreasing the NP to siRNA mass ratio from 20:1 to 5:1 resulted in gradual increase in hydrodynamic size, which sharply rose to 70.4 nm when the ratio reached 2:1 (Figure S2c in Supporting Information). At 1 mg Fe mL−1, the NPs were well dispersed and were able to form stable complexes with siRNA as it was added to the NP solution. When the feed siRNA concentration was increased, the instantaneous concentration of siRNA around the NP in the solution was also increased, reducing the chances of siRNA interacting with free amines to form small complexes, resulting in a slight growth in the hydrodynamic size of the NP-siRNA. Finally, as the NP:siRNA ratio was decreased, the NPs were not able to efficiently bind to and condense the siRNA, resulting in aggregation and increased hydrodynamic size. While NP:siRNA ratio of 20:1 showed the smallest hydrodynamic size, the NP:siRNA ratio of 5:1 was used for the remainder of the study as no significant aggregation was observed, and utilized less NP to condense the same amount of siRNA.

The chemical composition of CCP-PEI and the surface of the nanoparticle was analyzed using NMR spectroscopy and FTIR spectroscopy. The peaks from the terminal methoxy hydrogens on the PEG and the aromatic hydrogens on the catechol group were used to calculate the amount of PEG and catechol grafted onto the chitosan backbone (Figure 2d). It was determined that there were ~4 PEG and ~2 catechol per chitosan molecule (Equation S1 in supporting information). Using this information, the final composition of the CCP-PEI copolymer was determined to contain ~2 PEI, ~4 PEG, and ~2 catechol per chitosan backbone. Peptides CTX and R10 were conjugated onto the surface onto the NP by first, modifying the peptides with thiol groups using Traut’s reagent, then, linking the thiol to the amine groups on the NP using the heterobifunctional linker smPEG12. The successful conjugation of the peptides CTX and R10 was confirmed using FTIR spectroscopy. Upon conjugation of the peptides, peaks corresponding to C=O stretching (1640 cm−1), N-H bending (1590 cm−1), and C-N stretching (1113 cm−1) modes were observed, as shown in the FTIR transmission spectra of NP-CTX-R10 in Figure 2e. The degree of conjugation was found to be ~20 CTX/NP and ~29 R10/NP through BCA protein quantification assay.

Nanomaterials are susceptible to nonspecific aggregation during conjugation reaction due to high surface area to volume.60 For long term circulation in blood and efficient intracellular delivery, NPs should be stable in aqueous media. Particles that are too large will be cleared out by the liver prior to arriving to the intended site of therapeutic delivery, and will reduce the efficiency of the NPs.61,62 The hydrodynamic sizes of NP after peptide conjugation and complexation with siRNA in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) were measured to assess the stability of the structures at physiological pH. As can be seen in Figure 2f, the average hydrodynamic size of NP, NP-CTX-R10, and NP-siRNA were 29.91, 30.72, and 34.11 nm, respectively. The conjugation of peptides did not result in significant size increase, and the complexation with siRNA led to a slight increase in the hydrodynamic size. This indicates that the nanoparticle can form a stable complex with siRNA at physiological pH, and effectively condense the siRNA onto the polymer coating of the nanoparticle. The stability of NP in physiological conditions was assessed by measuring the hydrodynamic size of the NP in PBS and DMEM over 14 d. As shown in Figure 2g, no significant growth in size was observed, indicating that the nanoparticles are stable in aqueous media in physiological pH. The effect of peptide conjugation and siRNA complexation on the zeta potential of NP were also studied. As expected, NP exhibits high zeta potential (18.2 mV) due to the highly cationic PEI. The zeta potential is reduced slightly to 15.7 mV upon peptide conjugation, likely due to depletion of some of the free amine groups that had contributed to the positive charge through the conjugation process. The NP-siRNA complex shows significantly reduced zeta potential (7.5 mV), due to charge neutralization from the interaction between the cationic PEI and anionic siRNA backbone. (Figure 2h) The surface charge of nanoparticles is important for nanoparticles in biological applications, as it affects how the nanoparticle will interact with the various components in the biological system. A positive surface charge has shown to be beneficial in improving cellular uptake and internalization of the nanoparticles as the positively charge nanoparticles and negatively charged heads of the phospholipids in the cell membrane can electrostatically interact, and become internalized through endocytosis.63 However, the positive charge has also been associated with acute cytotoxicity through disruption of the cellular membrane and lysosomal damage. NP-CTX-R10 exhibits positive zeta potential, which was reduced with the complexation of siRNA. While the zeta potential of NP-siRNA is still positive, it is lower than that of the base nanoparticles, suggesting that it would be easily internalized by the cell membrane, while reducing the toxicity associated with positively charge nanoparticles.

3.3. Evaluation of NP-CTX-R10 as siRNA transfection vector

To assess the capability of NP-CTX-R10 in delivering siRNA to glioma cells. red fluorescent protein (RFP) was used as a reporter gene and anti-RFP siRNA (siRFP) was delivered to silence the expression of RFP. To assess the silencing efficiency, the following equation was used:

| Equation 1. |

The fluorescence was normalized to the number of cells to consider any toxicity caused by the transfection agents.

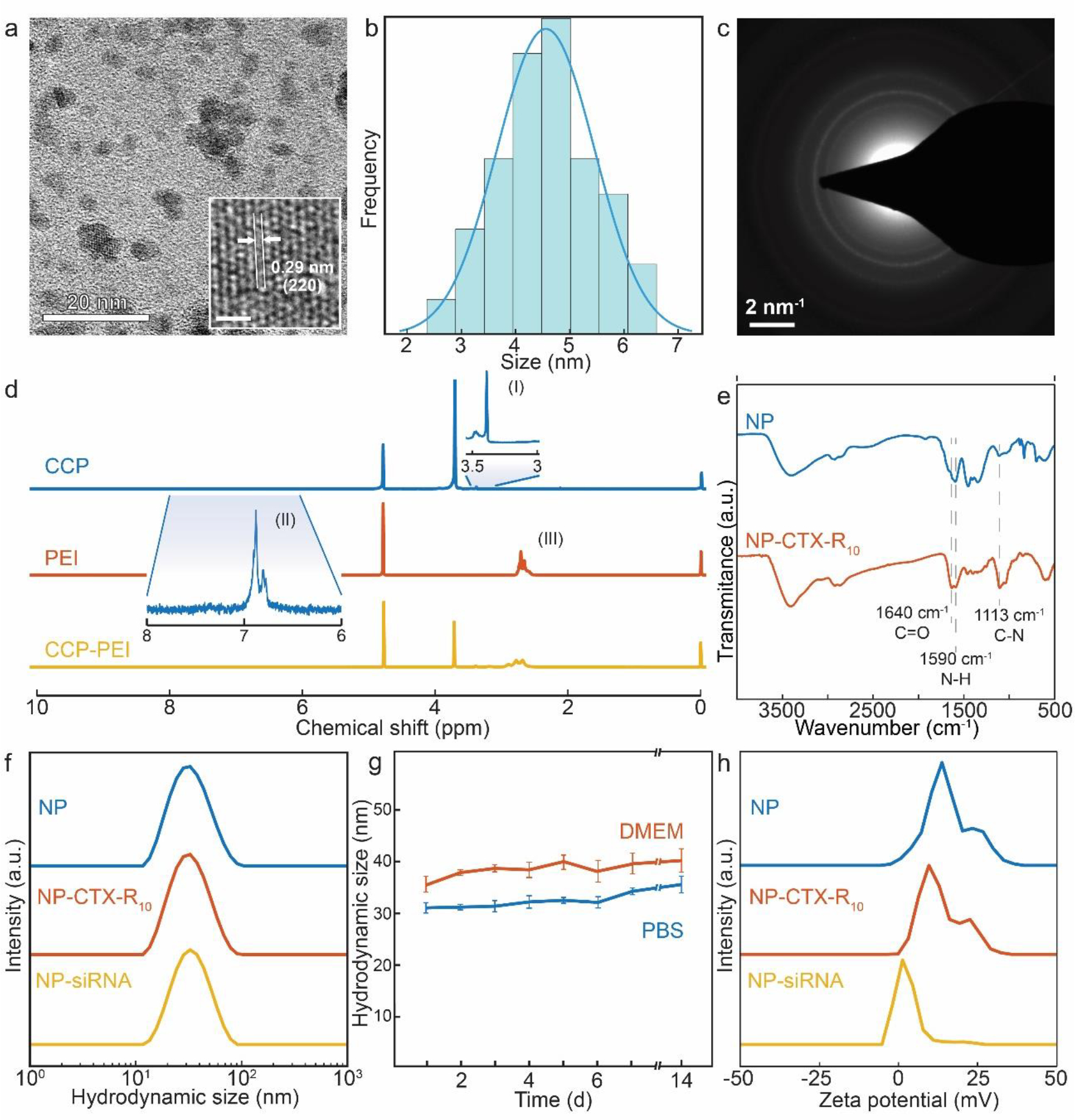

One of the challenges to siRNA delivery is the enzymatic degradation of siRNA by serum nuclease during the transport in blood; an effective transfection vector should be able to protect the therapeutic siRNA from the degradation.64 Gel electrophoresis was used to study the interaction between NP and siRNA. NP had condensed the siRNA effectively so that the siRNA was not separated from the nanoparticle by the applied electric field. At NP:siRNA ratio of 0.5:1, the binding capacity of NP was maximized, as intact siRNA was observed in the lane. (Figure 3a) To ensure that the siRNA was not degraded, heparin, which disrupts the electrostatic binding between cationic and anionic molecules, was added to the incubated complex solution. All the siRNA were then released, as indicated by the observed bands. The intensities of the bands were similar, indicating that no significant degradation of siRNA had occurred while complexed with NP. (Figure 3a) This ensures that the nanoparticle design allows for protection of siRNA from the ribonuclease-mediated degradation, as well as stable binding between the NP surface and siRNA. By condensing the siRNA onto the surface of the NP, the siRNA is ‘shielded’ from degradation mechanisms by the copolymer coating on the NP through steric interactions.65,66

Figure 3.

Optimization of transfection conditions. a) Agarose gel electrophoresis image of NP-siRNA complexed at NP:siRNA mass ratios from 20:1 to 0.5:1, then incubated in serum-containing media (top), and mixed with heparin (bottom). b) Agarose gel electrophoresis image of NP-siRNA consisting of various MW PEI (top), and mixed with heparin (bottom). c) Silencing efficiencies of NP-siRNA complexes with various NP:siRNA ratios and PEI MW compared to Lipofectamine control. Silencing efficiencies were calculated using Eq. 1

The effect of varying the molecular weight of PEI on the NP was also investigated. As shown in Figure 3b, some siRNA was able to dissociate from the NP-siRNA complex containing 800 MW PEI, whereas no siRNA was dissociated from NP-siRNA complexes containing 10k and 25k MW PEI. Due to the relatively low zeta potential, the NP containing 800 MW PEI did not exhibit efficient siRNA condensing capability. However, as noted by the difference in intensity of the band after addition of heparin, it can be seen that the NP containing 800 MW PEI is able to bind and condense some of the siRNA.

In order to optimize the conditions for siRFP transfection, NP:siRNA consisting of various ratios of NP:siRNA and molecular weight of PEI was used to silence RFP expression in C6 cells. The silencing efficiencies were calculated using Eq. 1. NP:siRNA ratios up to 2:1 were used as it has previously been shown that the siRNA binding capability of NP diminishes at lower ratios. The optimal condition was found for NP-siRNA complexed at a ratio of 5:1 ofNP:siRNA, with NP consisting of 10k MW PEI (Figure 3c). Generally, NP containing 10k PEI outperformed NP containing other MW PEI at all NP:siRNA ratios. With 800 MW PEI, as demonstrated in Figure 3b, siRNA is less compactly bound to the NP, which would decrease the amount of siRNA delivered by the NP as dissociation will occur prior to cellular uptake. NP consisting of 25k PEI was less effective than NP consisting of 10k PEI due to increased cytotoxicity, as well as strong interaction between the PEI and siRNA, delaying the dissociation of the complex. At NP:siRNA ratios greater than 5:1, the overabundance of NP relative to siRNA would require cells to internalize more NP to achieve the same level of siRNA in the cytosol. Complexes prepared with NP:siRNA ratio 2:1 were less effective than complex prepared with 5:1 ratio. This is likely due to the aggregates that formed during the mixing process, as demonstrated in Figure S2c, which would be more difficult for cells to internalize through endocytosis, and the structural irregularities would leave siRNA vulnerable to degradation. NP consisting of 10k MW PEI was conjugated with CTX and R10, then complexed with siRNA at a 5:1 ratio for the following studies.

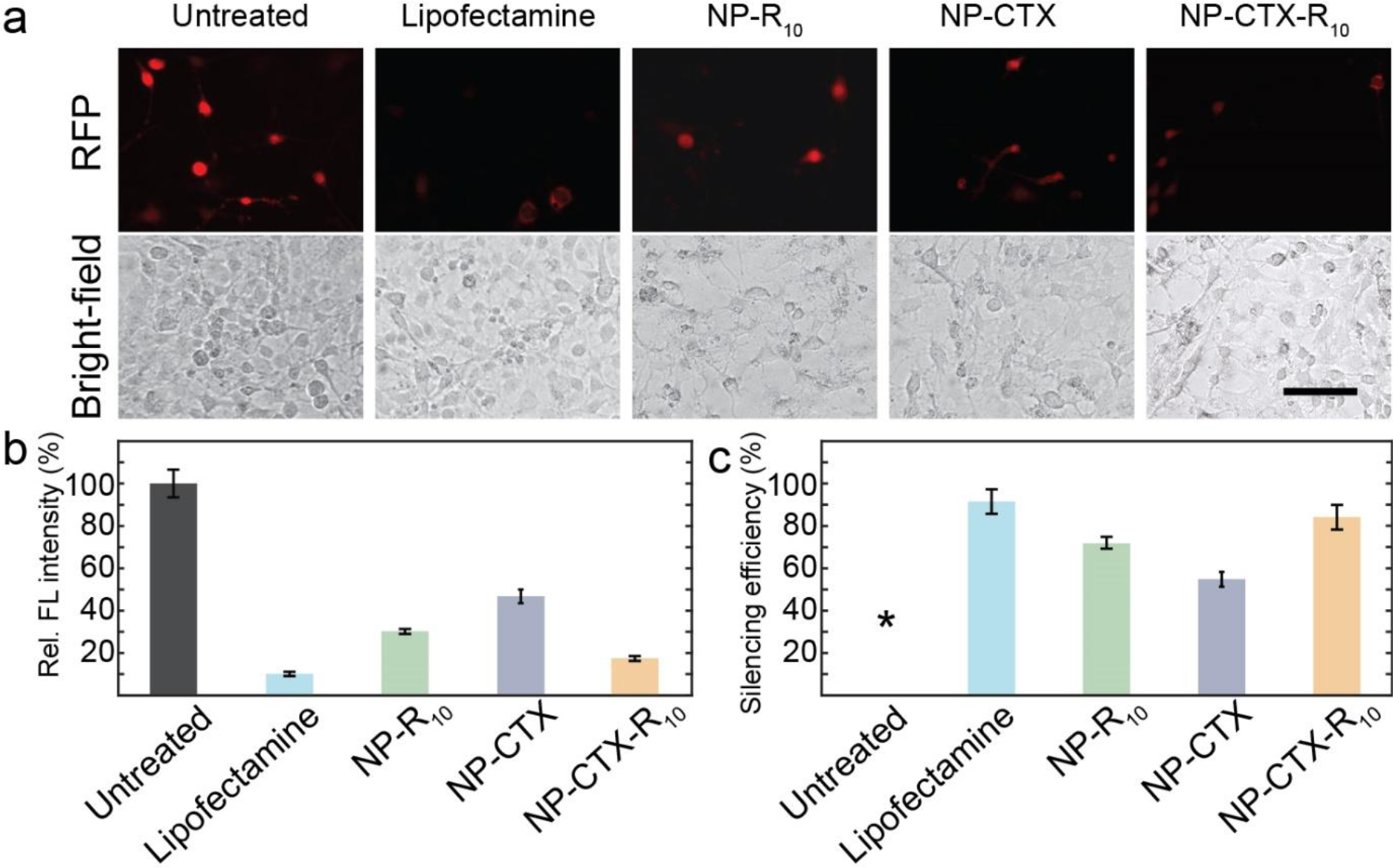

The NPs were then conjugated with peptides and complexed with siRNA. The resulting NP-siRNA complex was used to transfect C6 rat glioma cells. As shown in Figure 4a, NP-CTX-R10 was able to silence RFP expression in C6 cells. The silencing efficiencies, as calculated using Eq. 1 using the fluorescence intensities (Figure 4b), were 91.5% for Lipofectamine and 90.5% for NP-CTX-R10. (Figure 4c) The effects of each functional peptide on the silencing efficiency were also explored. The silencing efficiency was calculated to be 71.7% in cells transfected with NP-R10 and 54.8% in cells transfected with NP-CTX. While both NP formulations with a single type of peptide were able to silence the RFP expression, NP-CTX-R10 was able to achieve a greater degree of silencing comparable to a commercially available transfection agent. As the C6 cells are transiently transfected with RFP, it is of interest to confine the analysis of RFP knockdown to cells that have been successfully transfected with RFP pDNA initially. Through flow cytometry, the subpopulations of treated cells with successful RFP expression were identified using untreated cells as negative control and cells without siRNA transfection as positive control. As seen in Figure S3, the mean fluorescence intensity of cells transfected with NP-siRNA is comparable to that of cells transfected with Lipofectamine + siRNA.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of NP as siRNA transfection in C6 cells via fluorescence microscopy a) Fluorescent micrographs of C6 glioma cells transfected with siRNA via Lipofectamine, NP-R10, NP-CTX, or NP-CTX-R10. Brightfield micrographs of cells are provided directly under the fluorescent micrographs. Cells without siRNA transfection are used as untreated control. (Scale bar = 100 μm) b) Relative fluorescence intensity of RFP in C6 cells transfected with Lipofectamine, NP-R10, NP-CTX, and NP-CTX-R10. c) Silencing efficiency as calculated through Equation 1. *By default, the untreated cells exhibit silencing efficiency of 0%.

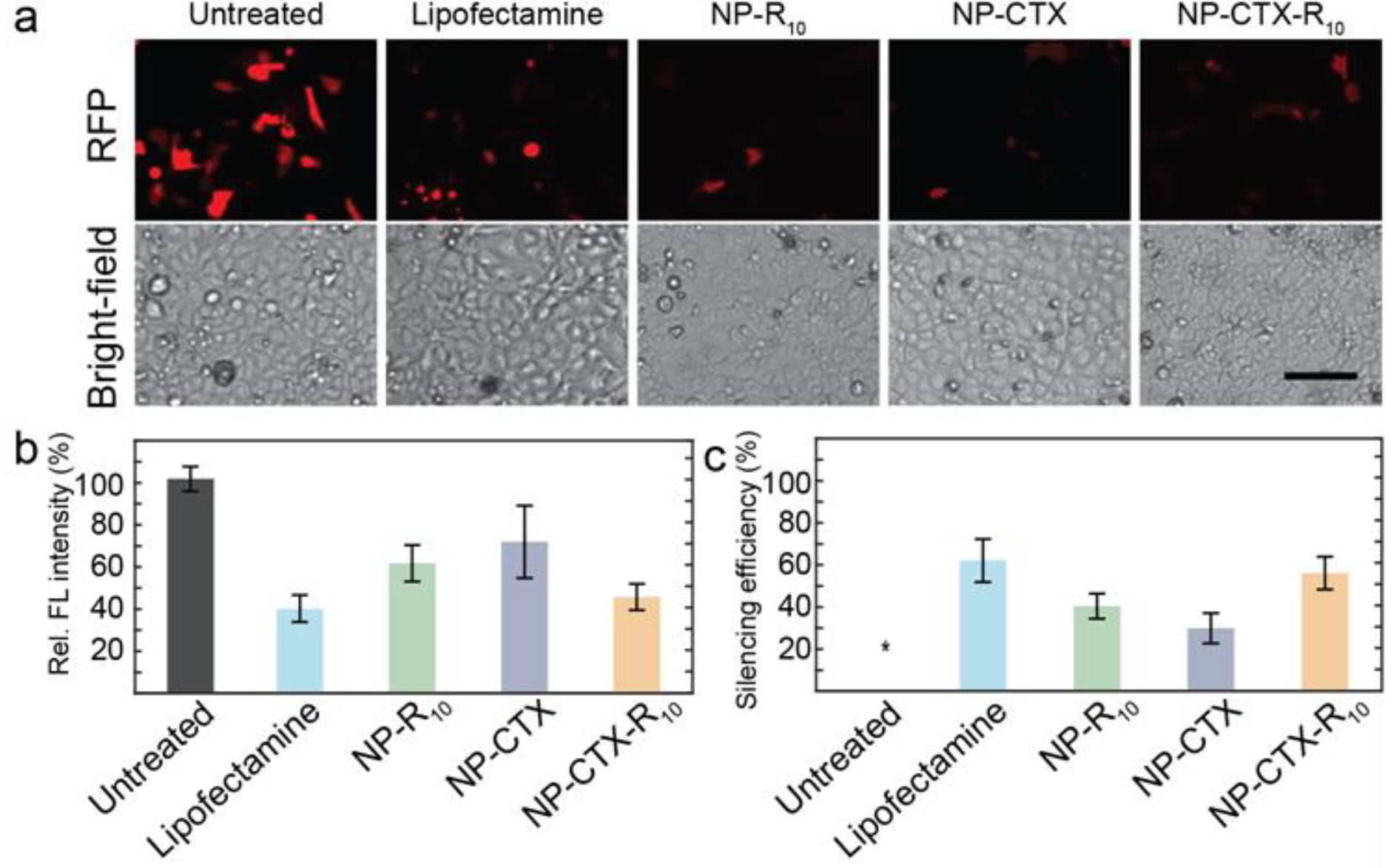

The silencing efficiency of siRNA delivered with NP-CTX-R10 was also tested in SF763 human glioblastoma cells to assess the efficacy of NP-mediated transfection in various cell lines. As can be seen in Figure 5a, RFP expression was knocked down in human glioma cells as well. The RFP silencing efficiencies were calculated to 62.1% for Lipofectamine, and 60.9% for NP-CTX-R10 in SF763 cells. (Figure 5c). Similarly, lesser degree of silencing was observed when NP-R10 or NP-CTX was used, with silencing efficiency of 40.1% and 29.7%, respectively. While the silencing efficiency varies across different cell lines, our nanoparticle demonstrated efficient delivery of siRNA to achieve silencing levels similar to that obtained by commercially available transfection reagents. The silencing efficiency was significantly improved when peptides CTX and R10 were both conjugated on the surface of the NP. It can be seen that no fluorescence can be observed in most cells, and any remaining RFP fluorescence is at a lower intensity than that in the untreated cells.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of NP as siRNA transfection in SF763 cells via fluorescence microscopy a) Fluorescent micrographs of SF763 glioma cells transfected with siRNA via Lipofectamine, NP-R10, NP-CTX, or NP-CTX-R10. Brightfield micrographs of cells are provided directly under the fluorescent micrographs. Cells without siRNA transfection are used as untreated control. (Scale bar = 100 μm) b) Relative fluorescence intensity of RFP in SF763 cells transfected with Lipofectamine, NP-R10, NP-CTX, and NP-CTX-R10. c) Silencing efficiency as calculated through Equation 1. *By default, the untreated cells exhibit silencing efficiency of 0%.

3.4. Evaluation of cellular uptake and siRNA release

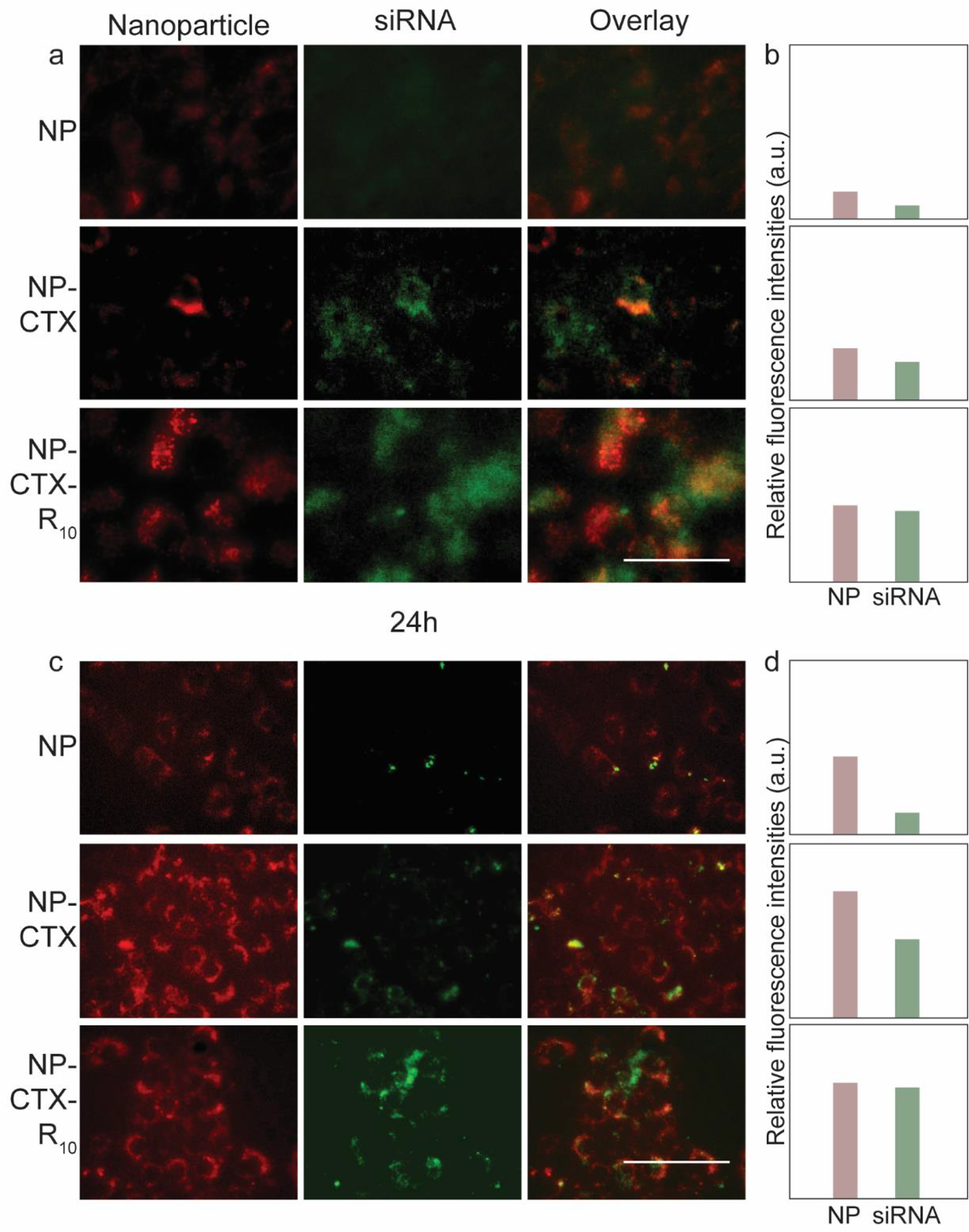

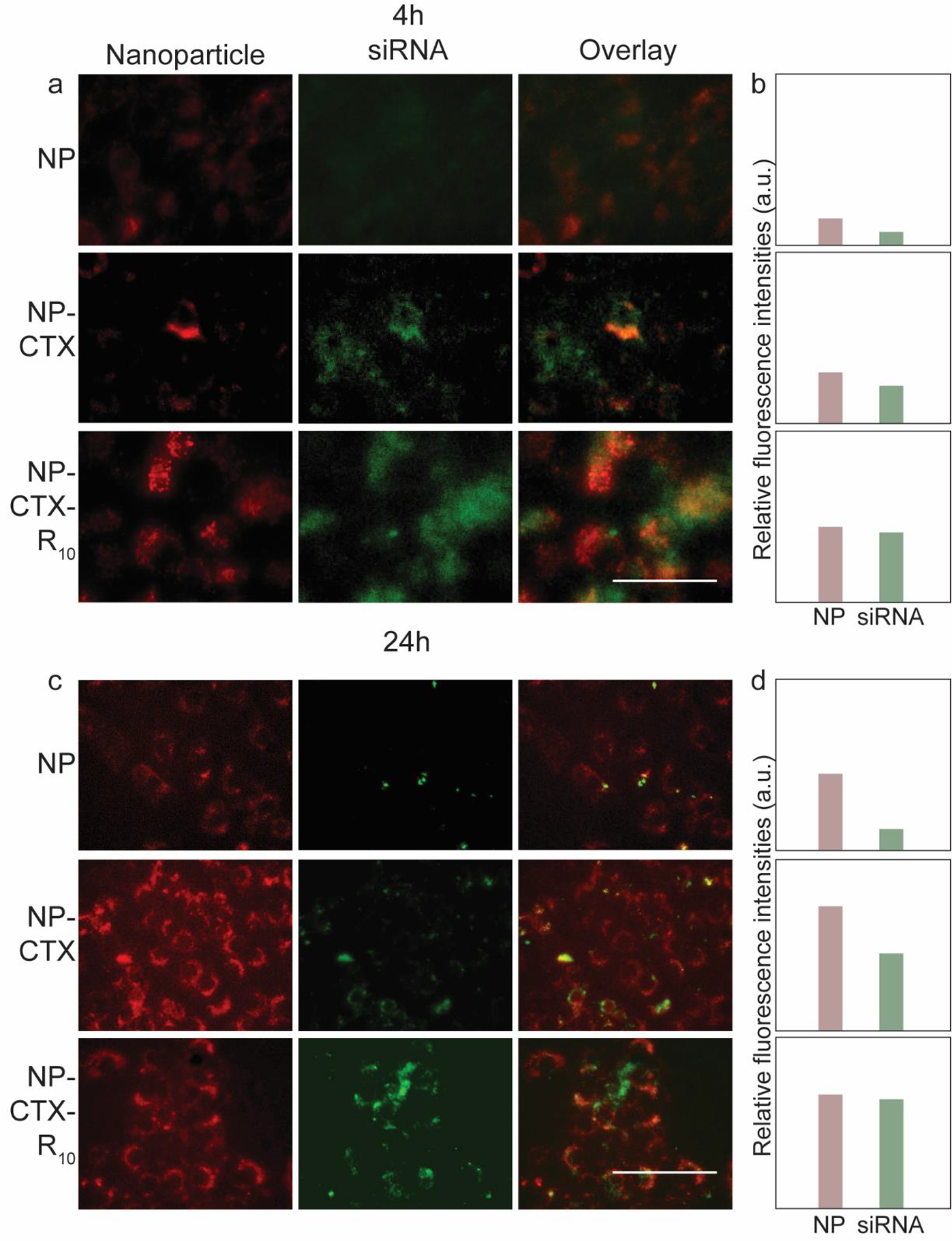

While the NP-mediated delivery of siRFP was successful in silencing the expression of the target protein, the mechanism of interaction between the peptides CTX and R10 with the cellular membrane release of the siRNA was to be elucidated. To investigate the role of the functional peptides in these processes, fluorescent labelled NP (NP-Cy5) and siRNA (siRNA-BDP FL) were used to observe the cellular uptake of the NP-siRNA complex and the release of siRNA. The cells were observed 4 h and 24 h after transfection with NP-siRNA. Fluorescence intensities from NP-CTX and NP-CTX-R10 treated C6 cells were greater than that from NP treated cells at both 4 h (Figure 6a,b) and 24 h (Figure 6c,d). There were no discernable differences in siRNA fluorescence in the three groups at 4 h; however, at 24 h, the NP-CTX-R10 treated cells exhibited greater siRNA fluorescence compared to NP and NP-CTX treated cells. (Figure 6d) Similar trends were observed in SF763 transfected with fluorescent labelled NP and siRNA complex. (Figure 7) Greater fluorescence was observed in cells transfected with peptide-conjugated NP, and siRNA fluorescence was the brightest in cells transfected with NP-CTX-R10 after 24 h.

Figure 6.

Fluorescent microscopy images of C6 rat glioma cells transfected with fluorescent labelled nanoparticles (red) and siRNA (green). a) Fluorescence images taken at 4 h after transfection. Overlaid fluorescent images are provided on the right-most columns. (Scale bar = 50 μm) b) Relative intensities of fluorescence from NP and siRNA in micrographs. c) Fluorescence images taken 24 h after transfection. (Scale bar = 50 μm) d) Relative intensities of fluorescence from NP and siRNA in micrographs in c).

Figure 7.

Fluorescent microscopy images of SF763 human glioma cells transfected with fluorescent labelled nanoparticles (red) and siRNA (green). a) Fluorescence images taken at 4 h after transfection. Overlaid fluorescent images are provided on the right-most columns. (Scale bar = 50 μm) b) Relative intensities of fluorescence from NP and siRNA in micrographs. c) Fluorescence images taken 24 h after transfection. (Scale bar = 50 μm) d) Relative intensities of fluorescence from NP and siRNA in micrographs in c).

CTX is a tumor cell-targeting peptide which binds to MMP-2 overexpressed in glioma cells. The role of CTX in our design was to selectively target glioma cells and enhance the cellular uptake of the NP-siRNA complex. As can be seen in Figures 6 and 7, conjugation of CTX had a noticeable effect on the internalization of the NP-siRNA complex, as demonstrated by the increased fluorescence intensity of the nanoparticle. The improvement in cellular uptake is further demonstrated through flow cytometry (Figure S4). However, improved cellular uptake alone may not be enough to effectively deliver siRNA. As nanoparticles are internalized through endocytosis, they are transported to the cytoplasm via endosomes. The internal environment of the endosome acidifies as it matures into late endosome and lysosome. Therefore, endosomal escape of nanoparticles is critical as the low pH may degrade the internal cargo of the endosomes if not released earlier.67–69 Arginine-rich peptides have been explored as CPPs due to their ability to interact with and disrupt the plasma membrane of cells. Because of this capability, they have also shown to destabilize the endosomal membrane, resulting in endosomal escape. The R10 moiety of the NP-CTX-R10 interacts with the inner membrane of the endosome, which releases the NP-siRNA and allows the formation of RISC with the RISC-associated proteins and the target mRNA to silence the target gene.57,70 Greater fluorescence intensity from siRNA was observed from cells transfected with NP-CTX-R10, compared to cells transfected with NP-CTX, indicating greater availability of siRNA in the cytosol to participate in gene silencing. The exact mechanism of endosomal escape and factors that hinder or promote the process remain to be fully uncovered. In addition to the role of CPP in destabilization of endosomal membrane, other methods such as the ‘proton sponge’ effect and fusogenic peptides have been explored to elucidate the mechanism of endosomal escape.71,72 The ‘proton sponge’ effect is based on the ability of amines in PEI to absorb protons, which in turn induces an influx of anions and water into the endosome. Combined with the increased repulsion within PEI due to the now-positively charged amines, the endosome would rupture and release the cargo. Our results suggest that rather than the ‘proton sponge’ effect, the use of functional peptides may enhance the endosomal escape of siRNA transfection vectors.

The NP-CTX-R10 system has shown to enhance the efficiency of siRNA delivery into glioma cells, and induce knockdown of target gene through the use of targeting peptides and CPP, as well as protecting the siRNA from degradation.

3.5. MGMT silencing and sensitization of glioma cells to TMZ

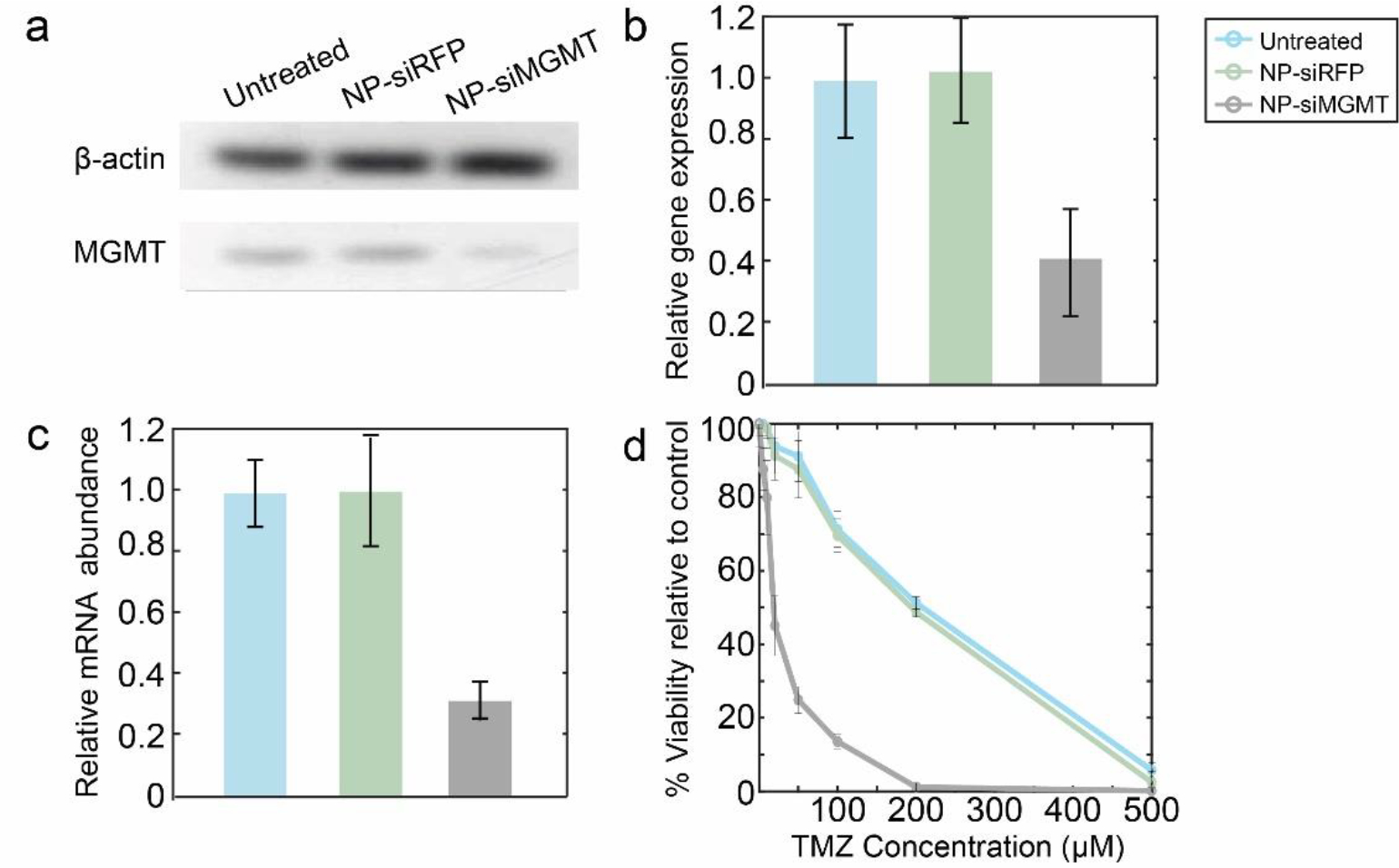

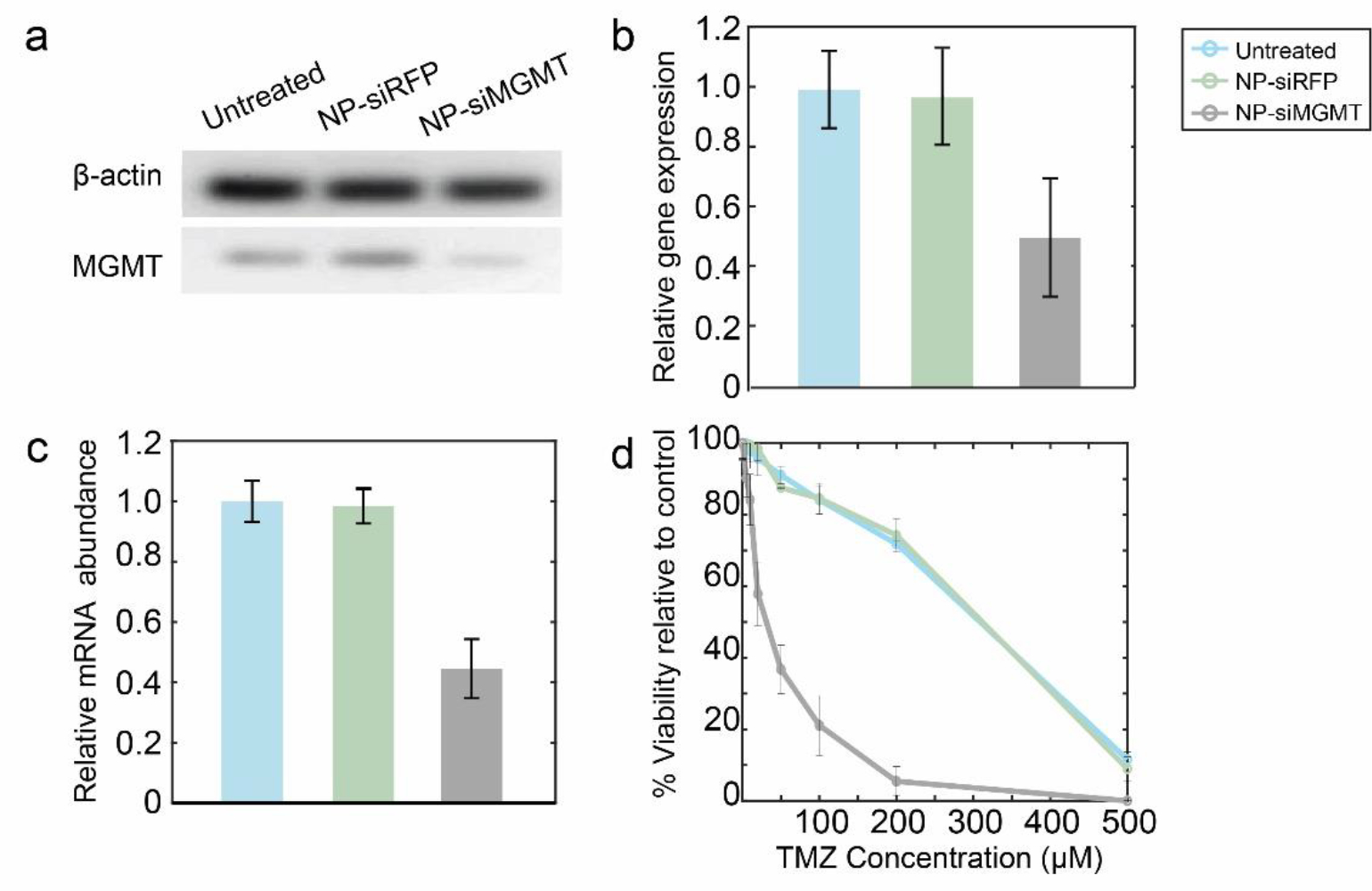

Finally, the ability of the NP-CTX-R10 system to deliver therapeutically relevant genes to enhance chemotherapeutic results was investigated. To evaluate MGMT expression levels after transfection with NP-siMGMT, Western blot was used to assess gene expression (Figure 8a). NP-siMGMT was able to reduce the expression of MGMT by 60% in SF763 cells (Figure 8b). siRFP transfected cells were used as a negative control to observe the target-specific knockdown, and the MGMT expression levels remained unchanged with delivery of siRFP. The knockdown of MGMT expression was confirmed through qRT-PCR. Cells transfected with NP-siMGMT had around 69% lower expression of MGMT compared to untreated cells, while NP-siRFP transfected cells had no significant decrease in MGMT expression (Figure 8c). To assess the change in TMZ sensitization after gene knockdown, glioma cells were transfected with siMGMT, then treated with TMZ. The relative viability of the SF763 cells after TMZ treatment measured through Alamar blue assay is shown in Figure 8d. It can be seen that after transfection with NP-siMGMT, the therapeutic effect of TMZ is significantly enhanced. The LD50 of TMZ in SF763 cells transfected with NP-siMGMT was extrapolated to be 18.1 μM, which was more than 10-fold greater than that in control cells (LD50 = 213.9 μM). In C6 cells transfected with siMGMT, MGMT expression was reduced by 50%, as determined by Western blot (Figure 9 a,b) and 54%, as determined by qRT-PCR (Figure 9c). Significant improvement in TMZ efficacy was also observed, as the LD50 was reduced to 30.6 μM from 314.4 μM when cells were transfected with NP-siMGMT prior to TMZ treatment. (Figure 9d)

Figure 8.

MGMT knockdown and chemosensitization in SF763 cells. a) MGMT and β-actin protein expression of SF763 cells transfected with NP-siRFP, or NP-siMGMT, or untreated cells. b) Relative protein expression as determined by intensities of Western blot bands normalized to β actin protein. c) Relative expression of MGMT determined via qRT-PCR compared to β-actin expression in SF763 cells after transfection with NP-siRFP or NP-siMGMT. d) Relative metabolic viability of SF763 transfected with NP-siRFP or NP-siMGMT treated with TMZ for 48 h.

Figure 9.

MGMT knockdown and chemosensitization in C6 cells. a) MGMT and β-actin protein expression of C6 cells transfected with NP-siRFP, or NP-siMGMT, or untreated cells. b) Relative protein expression as determined by intensities of Western blot bands normalized to β-actin protein. c) Relative expression of MGMT in C6 cells after transfection with NP-siRFP or NP-siMGMT. d) Relative metabolic viability of C6 transfected with NP-siRFP or NP-siMGMT treated with TMZ for 48 h.

TMZ is a chemotherapeutic drug whose function in cancer therapy is to perform O6 methylation of guanine, which is mutagenic and can trigger apoptosis in tumor cells.73 MGMT is a genomic repair enzyme which can undo the damage done to the DNA by alkylating agents such as TMZ. Hence, elevated levels of MGMT expression and activity have been associated with chemotherapeutic resistance of the tumor cells.74–76 By delivering siMGMT into the cytosol of glioma cells, MGMT expression would be silenced, and therefore allow TMZ-mediated alkylation of DNA to occur, resulting in tumor cell apoptosis. It can be seen that siMGMT delivered to glioma cells using NP-CTX-R10 was able to silence MGMT expression remarkably. No change in MGMT expression level was observed upon delivery of siRFP, indicating not only that siRNA-based therapy is target specific, but also indicating that the NP-CTX-R10 does not induce significant cytotoxicity on its own. The degree of chemosensitization was assessed by monitoring the viability of the siMGMT-transfected cells after TMZ treatment. The dramatically reducedLD50 of the glioma cells after treatment with NP-siMGMT was phenomenal, given that the gene knockdown levels indicated by qRT-PCR was no more than 70%. This may be attributed to the fact that qRT-PCR measures the mRNA expression encoded by a specific primer for the MGMT gene. The actual protein levels, as well as the activity of the MGMT enzymes may have been reduced further, leading to the 10-fold increase in the sensitivity of the transfected glioma cells to TMZ treatment. NP-CTX-R10 was able to sensitize different MGMT proficient glioma cell lines to TMZ treatment by effectively delivering siMGMT.

4. Conclusion

In this study, peptide-modified polymer coated IONPs were synthesized for targeted delivery of siRNA in glioma cells. The siRNAs were bound to NPs via electrostatic interaction. The use of targeting ligand CTX and cell-penetrating R10 enhanced the transfection capability of the PEI-coated NP by increasing the cellular uptake of the NP-siRNA complex. The polyarginine R10 also facilitated the endosomal escape of the NP-siRNA complex to allow sufficient presence of the siRNA in the cytosol while avoiding endosomal degradation. The resulting nanoparticles have a small hydrodynamic size of 34.11 nm and positive zeta potential of 7.5 mV. The NP-siRNA complex demonstrated efficient gene knockdown in different glioma cell lines, as indicated by decreasing RFP fluorescence. Finally, the NP-CTX-R10 was able to transfect glioma cells with siMGMT, and enhance their sensitivity to TMZ-mediated chemotherapy.

As nucleic-acid based therapeutics have become more viable options at the clinical stage with the onset of widespread distribution mRNA-based vaccines, development of vessels that can protect the nucleic acids from degradation and efficiently deliver the therapeutic nucleic acid to the target site has become ever more important. In the present study, we demonstrated an iron oxide nanoparticle-based system that can deliver siRNA into tumor cells. By utilizing biocompatible materials, as well as a facile co-precipitation synthesis method, this nanoparticle system presents a method that could be fine-tuned to deliver other genetic materials for applications in cancer therapy as well as other gene therapies. While further studies are required to validate the translation of the efficacy of the NP-CTX-R10 in vivo, this presents an exciting potential for overcoming current hurdles in the field of nucleic acid delivery.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health Grant (NIH/NIBIB R01EB026890). M. Z. acknowledges the support of Kyocera Chair Professor Endowment.

Funding Sources

This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health Grant (NIH/NIBIB R01EB026890).

ABBREVIATIONS

- siRNA

short interfering ribonucleic acid

- NP

nanoparticle

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

- CTX

chlorotoxin, R10, polyarginine

- MGMT

O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase

- TMZ

temozolomide

Footnotes

Supporting Information:

Supporting methods, optimization of polymer coating, optimization of nanoparticle and siRNA complexation ratio, and calculation of copolymer constituents using 1H-NMR.

REFERENCES

- (1).Liu H; Hu H; Li G; Zhang Y; Wu F; Liu X; Wang K; Zhang C; Jiang T Ferroptosis-Related Gene Signature Predicts Glioma Cell Death and Glioma Patient Progression. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2020, 8:538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Li X; Liu M; Zhao J; Ren T; Yan X; Zhang L; Wang X Research Progress About Glioma Stem Cells in the Immune Microenvironment of Glioma. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12:750857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Rynkeviciene R; Simiene J; Strainiene E; Stankevicius V; Usinskiene J; Miseikyte Kaubriene E; Meskinyte I; Cicenas J; Suziedelis K Non-Coding RNAs in Glioma. Cancers 2019, 11 (1), 17. 10.3390/cancers11010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).van Opijnen MP; van der Meer PB; Dirven L; Fiocco M; Kouwenhoven MCM; van den Bent MJ; Taphoorn MJB; Koekkoek JAF The Effectiveness of Antiepileptic Drug Treatment in Glioma Patients: Lamotrigine versus Lacosamide. J Neurooncol 2021, 154 (1), 73–81. 10.1007/s11060-021-03800-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Yang Z; Chen Z; Wang Y; Wang Z; Zhang D; Yue X; Zheng Y; Li L; Bian E; Zhao B A Novel Defined Pyroptosis-Related Gene Signature for Predicting Prognosis and Treatment of Glioma. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12:717926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Becker KP; Yu J Status Quo--Standard-of-Care Medical and Radiation Therapy for Glioblastoma. Cancer J 2012, 18 (1), 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Chao B; Jiang F; Bai H; Meng P; Wang L; Wang F Predicting the Prognosis of Glioma by Pyroptosis-Related Signature. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2022, 26 (1), 133–143. 10.1111/jcmm.17061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Anjum K; Shagufta BI; Abbas SQ; Patel S; Khan I; Shah SAA; Akhter N; Hassan S. S. ul. Current Status and Future Therapeutic Perspectives of Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) Therapy: A Review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 92, 681–689. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hu Y-H; Jiao B-H; Wang C-Y; Wu J-L Regulation of Temozolomide Resistance in Glioma Cells via the RIP2/NF-ΚB/MGMT Pathway. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 2021, 27 (5), 552–563. 10.1111/cns.13591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Jovanović N; Mitrović T; Cvetković VJ; Tošić S; Vitorović J; Stamenković S; Nikolov V; Kostić A; Vidović N; Jevtović-Stoimenov T; Pavlović D Prognostic Significance of MGMT Promoter Methylation in Diffuse Glioma Patients. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2019, 33 (1), 639–644. 10.1080/13102818.2019.1604158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Yu W; Zhang L; Wei Q; Shao A O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase (MGMT): Challenges and New Opportunities in Glioma Chemotherapy. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Moitra P; Chatterjee A; Kota PK; Epari S; Patil V; Dasgupta A; Kowtal P; Sarin R; Gupta T Temozolomide-Induced Myelotoxicity and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the MGMT Gene in Patients with Adult Diffuse Glioma: A Single-Institutional Pharmacogenetic Study. J Neurooncol 2022, 156 (3), 625–634. 10.1007/s11060-022-03944-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Haque W; Thong E; Andrabi S; Verma V; Brian Butler E; Teh BS Prognostic and Predictive Impact of MGMT Promoter Methylation in Grade 3 Gliomas. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2021, 85, 115–121. 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).SiRNA-Conjugated Nanoparticles to Treat Ovarian Cancer. SLAS Technology 2019, 24 (2), 137–150. 10.1177/2472630318816668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Lu Z-R; Laney VEA; Hall R; Ayat N Environment-Responsive Lipid/SiRNA Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2021, 10 (5), 2001294. 10.1002/adhm.202001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Huang X; Wu G; Liu C; Hua X; Tang Z; Xiao Y; Chen W; Zhou J; Kong N; Huang P; Shi J; Tao W Intercalation-Driven Formation of SiRNA Nanogels for Cancer Therapy. Nano Lett. 2021, 21 (22), 9706–9714. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c03539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Yang Y; Zhang X; Wu S; Zhang R; Zhou B; Zhang X; Tang L; Tian Y; Men K; Yang L Enhanced Nose-to-Brain Delivery of SiRNA Using Hyaluronan-Enveloped Nanomicelles for Glioma Therapy. Journal of Controlled Release 2022, 342, 66–80. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wang X; Hua Y; Xu G; Deng S; Yang D; Gao X Targeting EZH2 for Glioma Therapy with a Novel Nanoparticle–SiRNA Complex. IJN 2019, 14, 2637–2653. 10.2147/IJN.S189871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Teixeira FC; Bruxel F; Azambuja JH; Berenguer AM; Stefani MA; Sévigny J; Spanevello RM; Battastini AMO; Teixeira HF; Braganhol E Development and Characterization of CD73-SiRNA-Loaded Nanoemulsion: Effect on C6 Glioma Cells and Primary Astrocytes. Pharmaceutical Development and Technology 2020, 25 (4), 408–415. 10.1080/10837450.2019.1705485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lin G; Revia RA; Zhang M Inorganic Nanomaterial-Mediated Gene Therapy in Combination with Other Antitumor Treatment Modalities. Advanced Functional Materials 2021, 31 (5), 2007096. 10.1002/adfm.202007096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Revia RA; Stephen ZR; Zhang M Theranostic Nanoparticles for RNA-Based Cancer Treatment. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52 (6), 1496–1506. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wang K; Kievit FM; Sham JG; Jeon M; Stephen ZR; Bakthavatsalam A; Park JO; Zhang M Iron-Oxide-Based Nanovector for Tumor Targeted SiRNA Delivery in an Orthotopic Hepatocellular Carcinoma Xenograft Mouse Model. Small 2016, 12 (4), 477–487. 10.1002/smll.201501985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Osipova O; Zakharova N; Pyankov I; Egorova A; Kislova A; Lavrentieva A; Kiselev A; Tennikova T; Korzhikova-Vlakh E Amphiphilic PH-Sensitive Polypeptides for SiRNA Delivery. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2022, 69, 103135. 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Tai W Chemical Modulation of SiRNA Lipophilicity for Efficient Delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 307, 98–107. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Travella S; Klimm TE; Keller B RNA Interference-Based Gene Silencing as an Efficient Tool for Functional Genomics in Hexaploid Bread Wheat. Plant Physiol 2006, 142 (1), 6–20. 10.1104/pp.106.084517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Rajeev A; Siby A; Koottungal MJ; George J; John F Knocking Down Barriers: Advances in SiRNA Delivery. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6 (46), 13350–13362. 10.1002/slct.202103288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zheng Y; Tai W Insight into the SiRNA Transmembrane Delivery—From Cholesterol Conjugating to Tagging. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2020, 12 (3), e1606. 10.1002/wnan.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wei L; Guo X-Y; Yang T; Yu M-Z; Chen D-W; Wang J-C Brain Tumor-Targeted Therapy by Systemic Delivery of SiRNA with Transferrin Receptor-Mediated Core-Shell Nanoparticles. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2016, 510 (1), 394–405. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.06.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zou Y; Sun X; Wang Y; Yan C; Liu Y; Li J; Zhang D; Zheng M; Chung RS; Shi B Single SiRNA Nanocapsules for Effective SiRNA Brain Delivery and Glioblastoma Treatment. Advanced Materials 2020, 32 (24), 2000416. 10.1002/adma.202000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Karlsson J; Rui Y; Kozielski KL; Placone AL; Choi O; Tzeng SY; Kim J; Keyes JJ; Bogorad MI; Gabrielson K; Guerrero-Cazares H; Quiñones-Hinojosa A; Searson PC; Green JJ Engineered Nanoparticles for Systemic SiRNA Delivery to Malignant Brain Tumours. Nanoscale 2019, 11 (42), 20045–20057. 10.1039/C9NR04795F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Chung S; Revia RA; Zhang M Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Immune Cell Labeling and Cancer Immunotherapy. Nanoscale Horiz. 2021, 6 (9), 696–717. 10.1039/D1NH00179E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kievit FM; Wang FY; Fang C; Mok H; Wang K; Silber JR; Ellenbogen RG; Zhang M Doxorubicin Loaded Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Overcome Multidrug Resistance in Cancer in Vitro. Journal of Controlled Release 2011, 152 (1), 76–83. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Jeon M; Halbert MV; Stephen ZR; Zhang M Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as T1 Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Fundamentals, Challenges, Applications, and Prospectives. Advanced Materials 2021, 33 (23), 1906539. 10.1002/adma.201906539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Stephen ZR; Chiarelli PA; Revia RA; Wang K; Kievit F; Dayringer C; Jeon M; Ellenbogen R; Zhang M Time-Resolved MRI Assessment of Convection-Enhanced Delivery by Targeted and Nontargeted Nanoparticles in a Human Glioblastoma Mouse Model. Cancer Res 2019, 79 (18), 4776–4786. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Stephen ZR; Kievit FM; Veiseh O; Chiarelli PA; Fang C; Wang K; Hatzinger SJ; Ellenbogen RG; Silber JR; Zhang M Redox-Responsive Magnetic Nanoparticle for Targeted Convection-Enhanced Delivery of O6-Benzylguanine to Brain Tumors. ACS Nano 2014, 8 (10), 10383–10395. 10.1021/nn503735w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).James M; Revia RA; Stephen Z; Zhang M Microfluidic Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2020, 10 (11), 2113. 10.3390/nano10112113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lipka J; Semmler-Behnke M; Wenk A; Burkhardt J; Aigner A; Kreyling W Biokinetic Studies of Non-Complexed SiRNA versus Nano-Sized PEI F25-LMW/SiRNA Polyplexes Following Intratracheal Instillation into Mice. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2016, 500 (1), 227–235. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Ndong Ntoutoume GMA; Grassot V; Brégier F; Chabanais J; Petit J-M; Granet R; Sol V PEI-Cellulose Nanocrystal Hybrids as Efficient SiRNA Delivery Agents—Synthesis, Physicochemical Characterization and in Vitro Evaluation. Carbohydrate Polymers 2017, 164, 258–267. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ren J; Cao Y; Li L; Wang X; Lu H; Yang J; Wang S Self-Assembled Polymeric Micelle as a Novel MRNA Delivery Carrier. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 338, 537–547. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Li M; Li Y; Peng K; Wang Y; Gong T; Zhang Z; He Q; Sun X Engineering Intranasal MRNA Vaccines to Enhance Lymph Node Trafficking and Immune Responses. Acta Biomaterialia 2017, 64, 237–248. 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Zhang X; Duan Y; Wang D; Bian F Preparation of Arginine Modified PEI-Conjugated Chitosan Copolymer for DNA Delivery. Carbohydrate Polymers 2015, 122, 53–59. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Firoozi B; Nasser Z; Sofalian O; Sheikhzade-Mosadegh P Enhancement of the Transfection Efficiency of DNA into Crocus Sativus L. Cells via PEI Nanoparticles. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2018, 17 (8), 1768–1778. 10.1016/S2095-3119(18)61985-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Stephen ZR; Dayringer CJ; Lim JJ; Revia RA; Halbert MV; Jeon M; Bakthavatsalam A; Ellenbogen RG; Zhang M Approach to Rapid Synthesis and Functionalization of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for High Gene Transfection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8 (10), 6320–6328. 10.1021/acsami.5b10883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Kievit FM; Veiseh O; Bhattarai N; Fang C; Gunn JW; Lee D; Ellenbogen RG; Olson JM; Zhang M PEI-PEG-Chitosan Copolymer Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Safe Gene Delivery: Synthesis, Complexation, and Transfection. Adv Funct Mater 2009, 19 (14), 2244–2251. 10.1002/adfm.200801844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Narayanasamy KK; Price JC; Merkhan M; Elttayef A; Dobson J; Telling ND Cytotoxic Effect of PEI-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles on the Regulation of Cellular Focal Adhesions and Actin Stress Fibres. Materialia 2020, 13, 100848. 10.1016/j.mtla.2020.100848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Saqafi B; Rahbarizadeh F Effect of PEI Surface Modification with PEG on Cytotoxicity and Transfection Efficiency. Micro & Nano Letters 2018, 13 (8), 1090–1095. 10.1049/mnl.2017.0457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Kong X; Xu J; Yang X; Zhai Y; Ji J; Zhai G Progress in Tumour-Targeted Drug Delivery Based on Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Journal of Drug Targeting 2022, 30 (1), 46–60. 10.1080/1061186X.2021.1920026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Worm DJ; Els-Heindl S; Beck-Sickinger AG Targeting of Peptide-Binding Receptors on Cancer Cells with Peptide-Drug Conjugates. Peptide Science 2020, 112 (3), e24171. 10.1002/pep2.24171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Huey R; Rathbone D; McCarron P; Hawthorne S Design, Stability and Efficacy of a New Targeting Peptide for Nanoparticulate Drug Delivery to SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells. Journal of Drug Targeting 2019, 27 (9), 959–970. 10.1080/1061186X.2019.1567737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Deshane J; Garner CC; Sontheimer H Chlorotoxin Inhibits Glioma Cell Invasion via Matrix Metalloproteinase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278 (6), 4135–4144. 10.1074/jbc.M205662200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Sun C; Fang C; Stephen Z; Veiseh O; Hansen S; Lee D; Ellenbogen RG; Olson J; Zhang M Tumor-Targeted Drug Delivery and MRI Contrast Enhancement by Chlorotoxin-Conjugated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2008, 3 (4), 495–505. 10.2217/17435889.3.4.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Veiseh O; Kievit FM; Fang C; Mu N; Jana S; Leung MC; Mok H; Ellenbogen RG; Park JO; Zhang M Chlorotoxin Bound Magnetic Nanovector Tailored for Cancer Cell Targeting, Imaging, and SiRNA Delivery. Biomaterials 2010, 31 (31), 8032–8042. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Mu Q; Lin G; Patton VK; Wang K; Press OW; Zhang M Gemcitabine and Chlorotoxin Conjugated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Glioblastoma Therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 4 (1), 32–36. 10.1039/C5TB02123E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Asphahani F; Zheng X; Veiseh O; Thein M; Xu J; Ohuchi F; Zhang M Effects of Electrode Surface Modification with Chlorotoxin on Patterning Single Glioma Cells. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2011, 13 (19), 8953–8960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Sun P; Huang W; Kang L; Jin M; Fan B; Jin H; Wang Q-M; Gao Z SiRNA-Loaded Poly(Histidine-Arginine)6-Modified Chitosan Nanoparticle with Enhanced Cell-Penetrating and Endosomal Escape Capacities for Suppressing Breast Tumor Metastasis. IJN 2017, 12, 3221–3234. 10.2147/IJN.S129436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- (56).Hu J; Lou Y; Wu F Improved Intracellular Delivery of Polyarginine Peptides with Cargoes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123 (12), 2636–2644. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b10483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Najjar K; Erazo-Oliveras A; Mosior JW; Whitlock MJ; Rostane I; Cinclair JM; Pellois J-P Unlocking Endosomal Entrapment with Supercharged Arginine-Rich Peptides. Bioconjug Chem 2017, 28 (12), 2932–2941. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Erazo-Oliveras A; Muthukrishnan N; Baker R; Wang T-Y; Pellois J-P Improving the Endosomal Escape of Cell-Penetrating Peptides and Their Cargos: Strategies and Challenges. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2012, 5 (11), 1177–1209. 10.3390/ph5111177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Sun H; Jiang C; Wu L; Bai X; Zhai S Cytotoxicity-Related Bioeffects Induced by Nanoparticles: The Role of Surface Chemistry. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2019, 7:414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Fang C; Bhattarai N; Sun C; Zhang M Functionalized Nanoparticles with Long-Term Stability in Biological Media. Small 2009, 5 (14), 1637–1641. 10.1002/smll.200801647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Shilo M; Sharon A; Baranes K; Motiei M; Lellouche J-PM; Popovtzer R The Effect of Nanoparticle Size on the Probability to Cross the Blood-Brain Barrier: An in-Vitro Endothelial Cell Model. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2015, 13 (1), 19. 10.1186/s12951-015-0075-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Wang J; Liu G Imaging Nano–Bio Interactions in the Kidney: Toward a Better Understanding of Nanoparticle Clearance. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2018, 57 (12), 3008–3010. 10.1002/anie.201711705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Foroozandeh P; Aziz AA Insight into Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking of Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res Lett 2018, 13. 10.1186/s11671-018-2728-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Tatiparti K; Sau S; Kashaw SK; Iyer AK SiRNA Delivery Strategies: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Developments. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2017, 7 (4), 77. 10.3390/nano7040077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Mu Q; Hu T; Yu J Molecular Insight into the Steric Shielding Effect of PEG on the Conjugated Staphylokinase: Biochemical Characterization and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. PLoS One 2013, 8 (7). 10.1371/journal.pone.0068559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Nguyen N-TT; Yun S; Lim DW; Lee EK Shielding Effect of a PEG Molecule of a Mono-PEGylated Peptide Varies with PEG Chain Length. Preparative Biochemistry & Biotechnology 2018, 48 (6), 522–527. 10.1080/10826068.2018.1466157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Lönn P; Kacsinta AD; Cui X-S; Hamil AS; Kaulich M; Gogoi K; Dowdy SF Enhancing Endosomal Escape for Intracellular Delivery of Macromolecular Biologic Therapeutics. Scientific Reports 2016, 6 (1), 32301. 10.1038/srep32301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Smith SA; Selby LI; Johnston APR; Such GK The Endosomal Escape of Nanoparticles: Toward More Efficient Cellular Delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30 (2), 263–272. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).An R; Jia Y; Wan B; Zhang Y; Dong P; Li J; Liang X Non-Enzymatic Depurination of Nucleic Acids: Factors and Mechanisms. PLOS ONE 2014, 9 (12), e115950. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Qian Z; LaRochelle JR; Jiang B; Lian W; Hard RL; Selner NG; Luechapanichkul R; Barrios AM; Pei D Early Endosomal Escape of a Cyclic Cell-Penetrating Peptide Allows Effective Cytosolic Cargo Delivery. Biochemistry 2014, 53 (24), 4034–4046. 10.1021/bi5004102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Benjaminsen RV; Mattebjerg MA; Henriksen JR; Moghimi SM; Andresen TL The Possible “Proton Sponge ” Effect of Polyethylenimine (PEI) Does Not Include Change in Lysosomal PH. Molecular Therapy 2013, 21 (1), 149–157. 10.1038/mt.2012.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Teo SLY; Rennick JJ; Yuen D; Al-Wassiti H; Johnston APR; Pouton CW Unravelling Cytosolic Delivery of Cell Penetrating Peptides with a Quantitative Endosomal Escape Assay. Nat Commun 2021, 12 (1), 3721. 10.1038/s41467-021-23997-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Dresemann G Temozolomide in Malignant Glioma. OTT 2010, 3, 139–146. 10.2147/OTT.S5480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Liu H; Liao Y; Tang M; Wu T; Tan D; Zhang S; Wang H Trps1 Is Associated with the Multidrug Resistance of Lung Cancer Cell by Regulating MGMT Gene Expression. Cancer Medicine 2018, 7 (5), 1921–1932. 10.1002/cam4.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).McCormack AI; Wass JAH; Grossman AB Aggressive Pituitary Tumours: The Role of Temozolomide and the Assessment of MGMT Status. European Journal of Clinical Investigation 2011, 41 (10), 1133–1148. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Shi Y; Wang Y; Qian J; Yan X; Han Y; Yao N; Ma J MGMT Expression Affects the Gemcitabine Resistance of Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Life Sciences 2020, 259, 118148. 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.