Abstract

Objectives:

The illicit cigarette trade endangers public health because it increases access to cheaper tobacco products, hence fueling the tobacco epidemic and undermining tobacco control policies. The objective of this study was to evaluate the execution of an illicit cigarette eradication program under the jurisdiction of the local government in Indonesia. We sought to provide insights into the effectiveness of current policies and their impact on the illicit cigarette trade in line with the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) protocol to eliminate illicit trade in tobacco products.

Methods:

We conducted semistructured interviews with key policy-makers and semistructured FGDs with consumers and small- to medium-scale cigarette manufacturers at the district level. We indentified Pasuruan and Kudus as the districts or cities with the highest proportion of DBH CHT, and Jepara and Malang as a district with a highest illicit cigarette incident. We used reflective thematic analysis to identify the important opportunities and challenges facing illicit cigarette eradication programs in the three districts.

Results:

We identified four opportunities and four challenges related to illicit cigarette eradication program implementation under the local government. The opportunities for illicit cigarette eradication lie in strong central government regulatory and multisectoral authority support, consumer awareness, and local governments’ commitment to tobacco supply chain control. The key challenges facing illicit cigarette eradication include ineffective public dissemination programs, rapidly changing regulatory designs, consumers’ preferences for illicit products, and a lack of industrial involvement in tobacco supply chain control programs.

Conclusion:

In addition to significant budget allocation and increasing consumer awareness, local programs to eradicate illicit cigarette production require considerable evaluation to rethink the program’s design and external stakeholders’ engagement within the local government’s scope.

Key Words: illicit cigarette, eradication, DBH CHT, tobacco excise, legal enforcement

Introduction

Article 15 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) recognizes the threat of growing illicit trade in tobacco products. Illicit cigarettes are circulated or traded in an illegal manner, including those that are domestically produced (hereafter referred as domestic illicit cigarettes) or being smuggled across countries border (hereafter referred as smuggled cigarettes), with the intent to avoid taxes and regulations. The illicit cigarette trade endangers public health because it increases access to – often less expensive – tobacco products, thus fueling the tobacco epidemic and undermining tobacco control policies; it also causes substantial losses in government revenues and contributes to the funding of international criminal activities [1].

The tobacco industry’s main argument for interfering with the tax reform process in various countries is that a higher tobacco tax rate will increase the illicit cigarette trade [2]. Although tobacco taxation has been well documented as an effective strategy for decreasing the smoking prevalence in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [3], the government should anticipate the trade-off between the illicit cigarette threat and the rising tobacco tax. Some empirical evidence shows no linkages between illicit cigarette trade levels and tobacco tax increases, as recorded in Mongolia and Vietnam [4, 5], and implies that sharing information to identify brands and transaction hotspots is the most critical measure to combat illicit trade.

Due to its economic and health impacts, tobacco has been a controversial commodity in Indonesia for decades. Indonesia has a long history of tobacco smoking since Europeans introduced it in the sixteenth century, and tobacco smoking has quickly spread among the population [6]. Traditional cigarette production relied on the hand-rolling method until machinery invention and automation by the end of the 19th century [7]. However, the hand-rolling method is still popular. While the industry is still producing hand-rolled cigarettes (approximately 29.8% of the total cigarette market share), the hand-rolling method has become popular among consumers who manufacture the product for noncommercial use (known as tingwe or linting dewe) [8], which currently has no regulation; this has become another concern regarding tobacco control in Indonesia, as there is currently no regulation of tingwe activities.

According to Law No. 39/2007, cigarettes produced for noncommercial use are nonexcisable, preventing the authorities from making any legal enforcement on these types of products. In addition to the absence of penalties for tingwe consumers, there is currently no sanction on purchasing illicit cigarettes. Legal sanctions are only applicable for commercially produced illicit products. According to Law No. 39/2007, there are two types of penalties for selling illicit cigarettes: administrative and criminal provisions. Administrative enforcement involves the payment of fines, while criminal enforcement involves imprisonment or the payment of fines [9].

The number of smokers in Indonesia is continuously increasing, and the tax loss due to illicit cigarette consumption is estimated to reach over 27% of total tobacco excise revenue in 2018 in Indonesia [10]. This number is sharply increased compared to the 2013 figure of 13% [11] . Nonetheless, the study did not account for value added tax and local cigarette tax which explains the discrepancies with the more recent evidence. Another study in 2019 reported a far lower estimate, whereby of the 1,201 packs of cigarettes taken from adults of active smokers, only 1.6% were illicit cigarettes [12]. However, this survey was limited to six provinces and may not be nationally representative, potentially underestimating the actual illicit cigarette consumption. With the recent evidence, the illicit cigarette consumption in Indonesia remains a concern.

The consumption in Indonesia is mainly domestically produced cigarettes, which account for 99.38% of the total market share [13]. Indonesia’s consumer strongly prefers kretek cigarettes [7], which are traditional local cigarettes containing tobacco and clove. While transnational tobacco companies have found it difficult to penetrate the domestic market, Phillip Morris International (PMI) and British American Tobacco (BAT) have been able to infiltrate this Kretek market and are now involved in domestic cigarette manufacturing in Indonesia [14]. With the consumer’s preference for kretek, smuggled cigarettes account for only 5% of the total the illegal trade estimates [10].

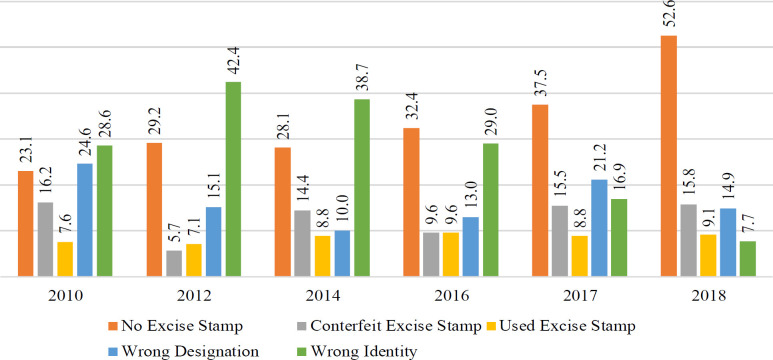

According to the Ministry of Finance definition, there are five types of domestic illicit cigarettes in Indonesia: (i) no excise stamp (known as rokok polos) – unpacked cigarettes without excise stamp; (ii) counterfeit excise stamps; (iii) used excise stamps; (iv) wrong identity – cigarettes packed with excise stamps but with incorrect business excise identification numbers; and (v) wrong designation (for example, the excise stamp is for the machine-made kretek category, but the producers label the cigarette as hand-rolled kretek instead) [9]. Figure 1 below illustrates the estimate of illicit cigarette production by type.

Figure 1.

Estimated Illicit Cigarette Production by Type (in Million Sticks), 2010 – 2018. Source: Ahsan (2019)

To account for the illicit cigarette trade, the Ministry of Finance gradually increased tobacco tax tariffs and allowed a certain proportion of tobacco excise as the Revenue Sharing Fund of Tobacco Products Excise (DBH CHT/Dana Bagi Hasil Cukai Hasil Tembakau). DBH CHT is a portion of excise tax revenue from tobacco products that is allocated to provincial and local governments. It was initially stated in Articles 6A and 6B of Law No. 39 of 2007 on Excise and was set at 2% (effective since 2008) for five allocations, one of which was for law enforcement against illegal cigarettes. Following the revision in the Omnibus Law of 2020, the DBH CHT allocation has been raised to 3% of the total cigarette excise revenue.

According to the Ministry of Finance Regulation (PMK) No. 215/2021 Article 11, the allocation for legal enforcement programs is 10%, comprising of three activities, e.g., industry development, socialization on excise regulations, and illicit cigarette eradication. According to article 6 of PMK No. 215/2021, industry development activities may include establishing, managing, and developing the Industrial Estate of Tobacco Products (which was later known as Kawasan Industri Hasil Tembakau/KIHT). KIHT is an integrated industrial estate dedicated to tobacco production activities developed and supervised by the local government in coordination with the local Customs and Excise Agency. In KIHT, tobacco producers can share their equipment, utilities, and other supporting facilities for production purposes. One of the primary purposes of KIHT development is to prevent illicit cigarette production [15]. With KIHT, small- and medium-sized enterprises can lower their production costs by sharing technologies and facilities. In addition, KIHT allows a more straightforward supervision process by the local Customs and Excise Agency.

Articles 7 and 8 of PMK No. 215/2021 each regulated the details of socialization and illicit cigarette eradication activities. The socialization of excise regulations may include the following activities: (i) informing the public and other stakeholders about the current excise regulatory framework (e.g., via printed, electronic, or online platforms) and (ii) monitoring and evaluating the implementation of excise regulation. At the same time, illicit cigarette eradication may include the following activities: (i) sharing and collecting information about illicit cigarette transactions; (ii) joint operation and prosecutions between local Customs and Excise Agency and local government to seize illicit products, which has been increasingly common in the past; and (iii) procurement and/or maintenance for supporting infrastructure and facilities to support illicit cigarette eradication activities.

Throughout the years of its implementation, few studies have documented the actual practice of DBH CHT earmarking for illicit cigarette eradication. In addition, few studies have been conducted to explore industry and consumer perspectives on illicit cigarette use in the Indonesian context. The aim of this study was to fill this void by evaluating the implementation of the DBH CHT for illicit cigarette eradication in Indonesia.

Materials and Methods

Study design

In this study, we employed a qualitative approach through in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs). We conducted interviews and focus group discussions from July to September 2021. The methodological orientation underpinning this study was qualitative analysis was conducted through a reflective thematic analysis [16]. The researcher systematically organized the data into four structured formats: consumers’ perceptions of illicit cigarettes, illicit cigarette eradication programs, opportunities, and critical challenges related to illicit cigarette eradication.

Case study selection

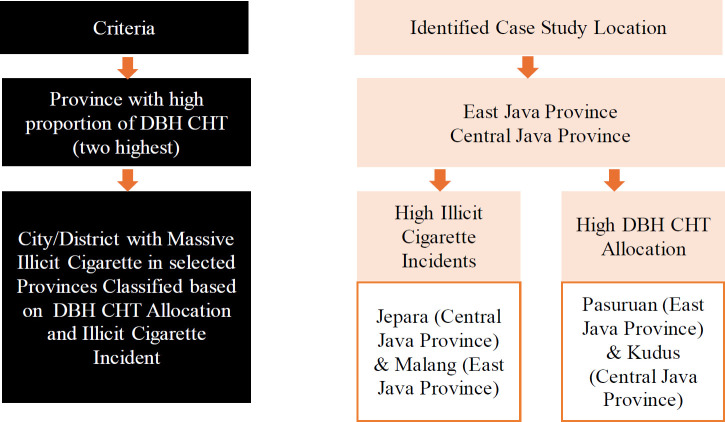

We selected case study locations purposefully based on the allocation of DBH CHT and the illicit cigarette incidents in those areas. To support our choice of case study, we looked at rules from the central government about how to divide up DBH CHT.

Additionaly The Minister of Finance, Republic of Indonesia, set these rules in Number 13/PMK.07/2020, explaining DBH CHT details based on province and city/region. We observed that the allocation of DHBCHT in 2020 was based on each region’s tobacco production, with East Java Province and Central Java Province receiving the highest allocation. Out of the total DBH CHT allocation of Rp 3.462.912.000.000 in 2020, East Java Province received the highest amount of Rp 1.842.770.283.000, while Central Java Province received the second highest amount of Rp 748.364.526.000. Pasuruan Regency and Malang Regency are the two regencies in East Java with the highest portion of DHBHT in this province, while Kudus Regency will have the highest DHBCHT in Central Java in 2020.

Then, we considered the illicit cigarette incident an important aspect of this study because it aims to examine the budget allocation of these two funds to a specific programme of illicit cigarette eradication. According to an online observation of the Ministry of Finance website, the study discovered that districts such as Jepara and Malang have massively identified illicit cigarette production (see official news published by Customs and Governments related to the illicit cigarette in those areas, for example: Customs of Kudus, 2021, Industry and Trade Agency East Java Province, 2021) [17, 18].

The study, considering the allocation of DBH CHT, selected East Java Province and Central Java Province as case studies. After district and city reviews, we selected Pasuruan and Kudus as the districts or cities with the highest proportion of DBH CHT, and Jepara and Malang as a district with a highest illicit cigarette incident in these two provinces. Map of selected case study location in various possibility of case study selection considering those three criteria, as follow (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Case Study Selection

Data Collection

We conducted two types of FGD which are FGD with smokers and tobacco industry. For smokers FGDs, we recruited active smokers in each location who had previously purchased illicit cigarettes—the methodology used to recruit these smokers through purposive and snowball sampling. We also invited eligible cigarette consumers and small (legal) cigarette entrepreneurs to participate in the FGDs. For policy-makers’ interviews, we selected participants through purposive sampling and recruited participants by delivering letters of information and invitations as participants to publicly available contacts. For each district, we interviewed relevant stakeholders from the Excise and Customs Service and Surveillance Agency, the Economic Division of the District Secretariat Agency, the District Development Planning Agency, the Municipal Police Agency, the Industrial Division of the District Industry and Trade Agency, and the Key Opinion Leaders/Cigarette Producers Association (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of FGD and Interviews Informants

| Kudus | Jepara | Malang | Pasuruan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of FGD Participants | ||||

| Consumers | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| Tobacco Industry | 4 | 7 | 4 | 8 |

| Number of Interview Participants | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

Data analysis

We inductively transcribed the FGDs and interviews, and the transcripts were coded and analyzed via thematic analysis in NVivo software. The author coded initial categories/themes from both interviews and FGDs.

Results

Consumers’ perceptions of illicit cigarettes

Most cigarette consumers are able to distinguish between licit and illicit cigarettes based on their physical characteristics, i.e., excising stamps and packaging. Cigarette consumers recognize that most illicit cigarettes have no excise stamps. Furthermore, most illicit cigarettes have unstandardized packaging (using only plastic wrap). However, some illicit cigarette producers have imitated licit cigarette excise stamps (using used excise stamps from licit products or printing fake excise stamps/counterfeit excise stamps) and packaging. Based on its excise stamp’s appearance, there are five types of illicit cigarettes: (i) no excise stamp; (ii) counterfeit excise stamp; (iii) wrong identity; (iv) wrong designation; and (iv) used excise stamp.

In addition to physical characteristics, the price of illicit cigarettes produced domestically is always lower than that of their counterparts. The current lowest cigarette retail price for legal products is 13,250 IDRs per pack of 20 sticks, while for the same pack, the lowest number of illicit cigarettes sold is 3,333 IDRs per pack. Based on our findings, the consumers reported that the highest price for a pack of 20 sticks is only IDR 7,500 – nearly half of the lowest price of the legal sticks. Hence, consumers who are unaware of physical characteristics should easily recognize illicit cigarettes by price.

Although some consumers are well informed about the differences between licit and illicit products, illicit cigarette use continues to meet their market demand. Our findings identified two main factors driving this behavior, i.e., price and easy access. Illicit cigarette prices range between IDR 3,333 and IDR 7,500 per pack, far below licit cigarette prices ranging from IDR 13,250 to IDR 31,650. The highly affordable price is another challenge facing tobacco control in Indonesia, as it will inevitably increase smoking prevalence.

Moreover, illicit cigarette production and transactions often occur outside of tobacco-producing areas. While these areas receive a significantly lower amount of DBH CHT allocation, they cannot control illicit cigarette consumption because they have insufficient funds for illicit cigarette eradication programs. Hence, illicit cigarettes remain a threat to the economy (through tax losses) and the health sector (increasing tobacco consumption).

Aside from their affordability, illicit cigarettes can also mimic the taste of a licit cigarette, leaving the consumer’s preference indifferent. Furthermore, illicit cigarettes are relatively easier to obtain. Compared to licit products, illicit cigarettes are widely available at the nearest market/shops, at neighborhoods, at community celebrations, or directly from illicit cigarette manufacturers. The illicit cigarette market has further expanded to include online platforms. Illicit cigarette production is primarily a home-based or often large industry with a closed marketing system, such as mouth-to-mouth marketing, making tracing difficult. Given their characteristics, illicit cigarettes are commonly popular among consumers from older populations, lower social classes, and blue-collar workers.

The illicit cigarette eradication program

The Ministry of Finance, through the Directorate General of Customs and Excise (DGCE), has become the leading institution for illicit cigarette regulation and enforcement [9]. The DGCE has local representatives (local Customs and Excise Agency), all under DGCE authorities. In addition, Article 34 of Law No. 39/2007 enables the DGCE to involve all required governmental institutions in legal enforcement to eliminate the illicit cigarette trade.

The local government is also actively engaged in illicit cigarette eradication activities. As previously discussed, the DBH CHT is used for socialization, KIHT, and legal enforcement activities. However, the local government institutions involved in the programs are unspecified in the existing regulations. Nevertheless, some of the critical local government institutions that may be engaged in illicit cigarette eradication activities as enacted by PMK No. 215/2021 are (but are not limited to) (i) the Local People’s Consultative Assembly (to determine the DBH CHT proportion for each illicit cigarette eradication program); (ii) the Economic Division of Local Secretariate Office (to determine the DBH CHT proportion for each illicit cigarette eradication program); (iii) the Local Office for Industrial and Trade Affairs (for KIHT activities); (iv) the Local Office for Public Communication and Information (for socialization activities); and (v) Local Police Institutions (for prosecution and legal enforcement).

With regulations mandating 10% DBH CHT earmarks for illicit cigarette eradication, the local government possesses sufficient resources to conduct legal enforcement actions to combat illicit cigarette production.

Based on PKM No. 13/PMK.07/2020, East Java and Central Java each received IDR 1.84 trillion and IDR 784.36 billion of DBH CHT allocation, a total of 83.96% of the national figure of IDR 3.46 trillion in 2020. Malang, Pasuruan, and Kudus acquired IDRs of 78.82 billion, 191.43 billion, and 158.11 billion, respectively. Compared to the total allocation for the 39 districts in East Java, that of the Malang and Pasuruan districts exceeded 6.11% and 14.84%, respectively. At the same time, Kudus acquired more than 28.24% of the total Central Java DBH CHT allocation for 36 districts. According to the regulation mandate, a 10% allocation of DBH CHTs should occur for illicit cigarette eradication and industrial development programs. As shown in Table 2 below, the three districts complied with the central government mandate by allocating IDR20 billion (25.38%), IDR50 billion (26.11%), and IDR38.8 billion (24.54%) to the DBH CHT. We did not obtain budget allocation details for the Jepara region.

Table 2.

Illicit Cigarette Product and Budget Allocation in Selected Districts in Indonesia, 2020

| District | Type of Activities | Activity/Program | Budget Allocation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malang | Socialization | Face-to-Face or Media Socialization | IDR 12 billion |

| Law enforcement | Collecting information (joint activities with Municipal Police and Excise and Customs Agency) | IDR 4 billion | |

| Law enforcement | Joint operation to eradicate illegal excisable products | IDR 2.5 billion | |

| Industrial development | The development and management of KIHT | IDR 1 billion | |

| Other | DBH CHT monitoring and evaluation | IDR 500 million | |

| Total | IDR 20 billion | ||

| Pasuruan | Industrial development and socialization | Research on KIHT development and socialization on legal and regulation public socialization | ID 2.5 billion |

| Socialization | Face-to-face socialization on legal and regulation to general public audiences and relevant stakeholders | IDR 20.3 billion | |

| Socialization | Online socialisation | IDR 20.3 billion | |

| Socialization | The socialization of excise regulation | IDR 2.3 billion | |

| Law enforcement | Eradication of illegal excisable products | IDR 4.6 billion | |

| Total | IDR 50 billion | ||

| Kudus | Industrial development | KIHT development and management | IDR 32.3 billion |

| Socialization | Face-to-face and online excise regulation socialization | IDR 6.3 billion | |

| Law enforcement | Eradication of illegal excisable products | IDR 225 million | |

| Total | IDR 38,8 billion | ||

Source: authors, from interviews with policymakers

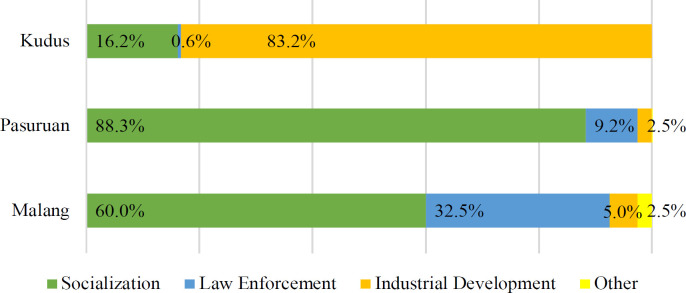

The Table above implies that, in general, activities and programs on illicit cigarette eradication vary from one district to another. The data highlight the local government’s autonomy in determining adjustable programs for their districts that are subject to their needs. However, illicit cigarette eradication programs centralize socialization, industrial development, and legal prosecution. For the three districts, legal prosecution for eradicating illicit cigarettes is a joint operation engaging multisectoral authorities. Figure 3 illustrates the district’s DBH CHT allocation for designated illicit cigarette eradication programs.

Figure 3.

Proportion of DBH CHT Allocated for Designated Illicit Cigarette Eradication Program in Three Main Tobacco Producing Districts, 2020. Source: authors, from interviews with policymakers

Figure 3 also implies that different districts may emphasize different types of activities. Socialization activities obtained the highest funding allocation in Malang and Pasuruan, with 60% and 88%, respectively. At the same time, Kudus spent nearly 84% of its budget on industrial development. Furthermore, Malang allocated a greater proportion of funds to legal prosecution activities than did Pasuruan and Kudus (i.e., 32.5%). Although which scheme or activity results in the best outcome for illicit cigarette eradication remains unclear, excise and customs agencies in each district have attempted to estimate the potential tax loss due to illicit cigarette production. Figure 4 presents the estimated government tax revenue loss due to illicit cigarette use from 2018 to 2021.

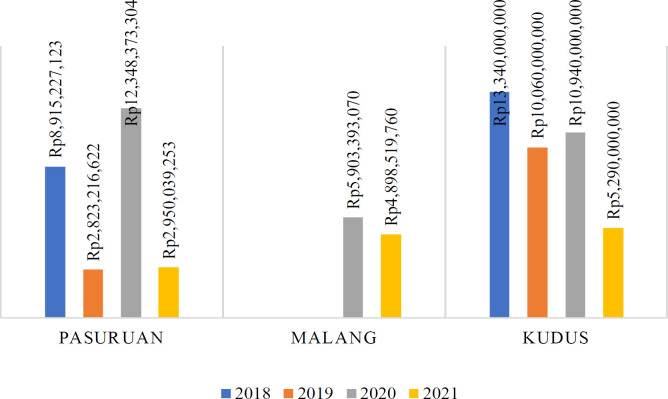

Figure 4.

Estimated Tax Revenue Loss due to Illicit Cigarette Consumption in Selected Districts in Indonesia, 2018 – 2021. Source: authors, from local Customs and Excise Agency

The information displayed in Figure 4 is derived from the official estimates of the local Customs and Excise Agency. This estimate is calculated by multiplying the number of illicit cigarettes (in stick) caught in the prosecution process by the estimated retail price. The assumption made by the government explained the rising trend in estimated tax loss as it follows the increasing number of prosecutions. Figure 4 shows that a single district loses up to IDR 13 billion a year due to the illicit cigarette trade. The effectiveness of these programs for eradicating illicit cigarettes continues to fluctuate annually. From Figure 4, we can conclude a decreasing trend for illicit cigarette production (as illustrated by the estimated tax loss) in Kudus; we cannot reach the same conclusion for Malang, as only two years were considered.

In contrast, the figure in Pasuruan fluctuated greatly. The different figures of estimated tax loss illustrated in Figure 4 might indicate the activity/programme that is most likely to contribute to the success of illicit cigarette eradication. As shown in Figure 3, Kudus allocated nearly 84% of the total budget to illicit cigarette eradication for industrial development programs. In contrast, 86% of Pasuruan’s budget was spent on socialization programs. According to the FGD findings, small industries producing illicit cigarettes are well informed about regulating illicit cigarettes and tobacco excise. Despite this, tough competition and complex legal procedures encourage small industries to produce illicit cigarettes; they further recognize that KIHT which enables small- and medium-scale industries to produce in the center of industrial activities and lower their production cost might be a win‒win solution for small industries.

The development of KIHT in major tobacco-producing regions is one of the leading strategies used by the government for illicit cigarette eradication. KIHT is regulated by the Minister of Finance Regulation (PMK/Peraturan Menteri Keuangan) No. 21/2020. KIHT is considered one of the most effective strategies for controlling local illicit cigarette production. Illicit cigarette production by small- to medium-scale industries was due to complex legal procedures concerning cigarette production. PMK No. 200/2011 required the cigarette industry to have a minimum of 200 meters square to be eligible for a legal manufacturing operation. In addition, tight competition with the large-scale cigarette industry contributes to illicit cigarette production by small- to medium-scale industries. Hence, the government expects KIHT to allow illicit cigarette supply control by facilitating ease of business and lowering production cost/cost efficiency for small- to medium-scale industries; it also relates to law enforcement activity/programme, as the authority could easily detect and locate small/home ill industries outside the industrial estate industry.

However, KIHT could control illicit cigarette production by providing production facilities for small industries (often unable to pay excise). Cigarette production facilities promoted by small industries attenuate tobacco control activities, leading to increased tobacco consumption.

While KIHT could help authorities control the tobacco supply chain, several challenges remain in the Indonesian context. Industries and manufacturers acknowledge that, despite budget allocation, the current government KIHT implementation is ineffective. Many warehouses remain empty while the government plans to extend the KIHT, which implies a lack of government communication with local manufacturers, particularly small- to medium-scale industries (the main target of KIHT). In addition, some industries are still unaware of the roles and benefits of KIHT.

Combatting illicit cigarettes in Indonesia: Opportunities and challenges

Based on these findings, we identified four key opportunities and challenges for illicit cigarette eradication in Indonesia. The first opportunity came from the central government (e.g., the Ministry of Finance), which provides full legal and regulatory support for the program. According to the latest Ministry of Finance regulation on DBH CHT utilization, 25% of DBH CHT is for illicit cigarette eradication. This figure has increased from the preceding regulation. With a sufficient budget available, the local government should be able to execute and evaluate activities to eradicate illicit cigarette production.

Second, the joint operation program has shown multisectoral actors’ commitment to eliminating illicit trade. The data from the local Customs and Excise Agency in East Java have shown that from January to December 2020 alone, there were 352 prosecutions for an illicit cigarette, resulting in the seizure of 27.8 million cigarette sticks. When the number of prosecutions increased to 390 in the following year, the total number of illicit cigarette seizures decreased significantly by 8.5 million sticks (only 19.5 million). This trend is consistent with the decrease in legal cigarette production from 322 billion sticks in 2020 to 320.2 billion sticks in 2021 [8].

The third opportunity concerns consumer awareness. Our findings suggest that consumers are increasingly aware of the illicit cigarette trade and can quickly identify products. Finally, the fourth opportunity lies in the government’s commitment to KIHT extensification and intensification. This measure is one of the most widely applied strategies for combatting illicit cigarette use in other countries, e.g., supply chain control.

Similarly, there are four main challenges to implementing illicit cigarette eradication at the district level. First, a considerable proportion of DBH CHTs are still for socialization activities. The socialization program designed by the local government is still considered inefficient. Hence, the local government should rethink DBH CHT allocation when designing illicit cigarette eradication programs. An appropriate evaluation for each program should follow this measure.

The second key challenge relies on uncertain and fast-changing regulatory design. The local governments have stated that the Ministry of Finance regulation on tobacco excise continues to change, resulting in policy uncertainty for the local governments. Third, the main challenge for illicit cigarette eradication lies in consumers’ perspectives and preferences. Consumers prefer affordable products over legal ones, so the demand and market for illicit cigarettes continue to exist. Finally, the lack of government communication with the industry – particularly for illicit cigarette eradication programs – could attenuate the government’s efforts toward such programs.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the perspectives of consumers, policy-makers, and small industries on the current state of illicit cigarette eradication activities under DBH CHT funding. This research confirmed and contrasted with previous studies. According to previous studies in EU countries, the price factor is the primary determinant of illicit cigarette consumption [19] . In contrast, the findings in Vietnam suggested that some consumers are willing to pay more for illicit products due to their strong preferences for imported products [5].

Regarding cigarette consumer characteristics, the findings of this study are consistent with the findings of several South African townships where the illicit cigarette market is popular among low-SES consumers [20]. A national survey in Indonesia revealed that low-income families still place cigarette spending as a second priority, and illicit cigarette consumption by these low-income groups indicates that efforts to protect them from the effects of cigarette consumption are becoming increasingly difficult [21]. While some regions in Indonesia perceive illicit cigarette consumption as disgraceful, as evidenced by other countries where illicit cigarette consumption is commonplace [22], the government should anticipate a strong price preference for illicit cigarettes. To address this, they should strengthen existing non-fiscal measures to complement price controls. These non-fiscal measures can raise awareness about quitting tobacco use [23, 24], even with price changes. Indonesia currently has a minimal measure on smoke-free environments with the smoke-free laws exist only for health-care and educational facilities, as well as public transport. Additionally, Indonesia has an extremely weak tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship (TAPS) ban. With these poor non-fiscal measures, tobacco consumption among adults will likely remain strong regardless of tobacco tax increases. The relatively affordable price of illicit cigarettes compared to legal options will continue to fuel the illicit market, as consumers seek cheaper alternatives.

Regarding policy-makers’ priorities and program designs, we concluded that some districts might be on track and are giving the proper priority to the most effective activity. Under the World Health Organization (WHO) Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products, the KIHT strategy relates to supply chain control [1], an effective measure for combatting illicit trade. The licensing strategy, which includes engaging in any activity within the tobacco supply chain, is one of the most common illicit cigarette eradication strategies applied by countries globally [25]. Furthermore, tobacco supply chain control has successfully handled cigarette smuggling in other countries [26] . However, one must note that the tobacco supply chain controlled by the tobacco industry will result in otherwise [27]. Therefore, controlling the supply chain requires the government to be heavily in charge of supervising and monitoring the KIHT. To further strengthen the KIHT strategy, a robust implementation including a stricter licensing procedures, advanced tracking and tracing within the supply chain, and a solid monitoring system to avoid industry interference. In addition to KIHT, the joint operation of and prosecutions for illicit cigarette eradication as it has become more common in recent decades provides multisectoral stakeholder support for these programs. This measure has also proven effective in law enforcement in European Union (EU) countries [28]. To enhance the existing joint operations, the government needs to develop an improved inter-agency cooperation, information sharing, and resources allocation. Finally, the central governemnt should lead a multi-pronged measures including price control, non-fiscal measures, robust supply chain monitoring and management, and strength law enforcement, to be implemented and engage the stakeholders at both national and sub-national level.

In conclusion, only a few attempts have been made to evaluate illicit cigarette eradication programs in Indonesia, despite recent studies documenting rising transaction volume figures. Using thematic analysis from FGDs and interviews with key stakeholders, we found that local programs to eradicate illicit cigarette production are facing considerable challenges amidst budget allocation from the central government and increasing consumer awareness. These challenges imply a need to evaluate the program’s design and external stakeholders’ engagement in district-level programs.

Acknowledgements

General

The authors would like to thank Universitas Indonesia for providing the grant to conduct this research. This project would not have been possible without support from the Customs and Excise Directorate, the Ministry of Finance and all regional representatives in Malang, Pasuruan, Jepara, and Kudus.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Universitas Indonesia Indonesian Collaborative Research Program.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee (MHREC) Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing Universitas Gadjah Mada (No. KE/FK/0433/EC/2021).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author Contribution Statement

AA, YSP, and SM conceptualized the study. KPR, MV, SR, and AMY conducted the data collection process. AA, KPR, NA, MGU, AD drafted the manuscript.

References

- 1.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control DGO. World Health Organization & WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, editor. World Health Organization; 2013. Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products [Internet] Available from: https://fctc.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241505246 Available from: https://fctc.Who.Int/publications/i/item/9789241505246. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liutkutė-Gumarov V, Galkus L, Miščikienė L, Petkevičienė J, Štelemėkas M, Telksnys T, et al. Estimating the size of illicit tobacco market in lithuania: Results from the discarded pack collection method. Nicotine Tob Res. 2023;25(8):1431–9. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntad013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malone RE, Warner KE. Tobacco control at twenty: Reflecting on the past, considering the present and developing the new conversations for the future. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):74–6. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross H, Vellios N, Batmunkh T, Enkhtsogt M, Rossouw L. Impact of tax increases on illicit cigarette trade in mongolia. Tob Control. 2020;29(Suppl 4):s249–s53. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen A, Nguyen HT. Tobacco excise tax increase and illicit cigarette consumption: Evidence from vietnam. Tob Control. 2020;29(Suppl 4):s275–s80. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid A. From betel-chewing to tobacco-smoking in Indonesia. J Asian Stud. 1985 ;44(3):529–47. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priyatna CC. The invisible cigarette, the production of smoking culture and identity in Indonesia (Doctoral dissertation, Monash University) 2013:303. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santoso R. Dilemma of tobacco control policy in Indonesia. [Internet] Study. 2016;21(3):201–19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahsan A. Ch15 Indonesia tackling illicit cigarettes. 2019. pp. 439–67. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasri R, Ahsan A, Wiyono N, Jacinda A, Kusuma D. New evidence of illicit cigarette consumption and government revenue loss in indonesia. Tob Induc Dis. 2021;19:1–8. doi: 10.18332/tid/142778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahsan A, Wiyono NH, Setyonaluri D, Denniston R, So AD. Illicit cigarette consumption and government revenue loss in indonesia. Global Health. 2014;10(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12992-014-0075-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kartika W, Thaariq RM, Ningrum DR, Ramdlaningrum H, Martha LF, Budiantoro S. The Illicit Cigarette Trade in Indonesia. INITIATIVE Association; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.IAKMI. INDONESIA Tobacco Facts 2020 Empirical Data for Tobacco Control. Indonesian Public Health Experts Association; 2020. p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurt RD, Ebbert JO, Achadi A, Croghan IT. Roadmap to a tobacco epidemic: Transnational tobacco companies invade indonesia. Tob Control. 2012;21(3):306–12. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.036814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bogor Customs and Excise. Tobacco Products Industrial Area (KIHT) [Internet] 2022 . [[cited 2022 Oct 30]]. Available from: https://bcbogor.beacukai.go.id/kawasan-industri-hasil-tembakau-kiht/

- 16.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kudus Customs and Excise. Kudus Customs Traces Illicit Cigarette Packaging in Jepara [Internet] [2020 [cited 2024 Jun 4]]. Available from: https://bckudus.beacukai.go.id/2020/09/17/bea-cukai-kudus-bongkar-pengepakan-rokok-ilegal.

- 18.Industry and Trade Agency of East Java Province. Assessing the Potential of East Java Province as Tobacco Industry Areas [Internet] 2021. Available from: https://disperindag.jatimprov.go.id/post/detail?content=menakar-potensi-jawa-timur-sebagai-kawasan-industri-hasil-tembakau.

- 19.Aziani A, Calderoni F, Dugato M. Explaining the consumption of illicit cigarettes. J Quant Criminol. 2021;37(3):751–89. [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Zee K, Vellios N, van Walbeek C, Ross H. The illicit cigarette market in six south african townships. Tob Control. 2020;29(Suppl 4):s267–s74. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kompas. Bps: Cigarettes are the second largest contributor to the poverty line [internet] 2020. Available from: https://money.Kompas.Com/read/2020/01/15/163637326/bps-rokok-penyumbang-terbesar-kedua-pada-garis-kemiskinan.

- 22.Stead M, Jones L, Docherty G, Gough B, Antoniak M, McNeill A. ‘No‐one actually goes to a shop and buys them do they?’: attitudes and behaviours regarding illicit tobacco in a multiply disadvantaged community in England. Addiction. 2013 ;108(12):2212–9. doi: 10.1111/add.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayasinghe R, Amarasinghe H. Assessment of the effectiveness of an intervention to quit tobacco use. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medawela RMS, Ratnayake DRDL, Premathilaka N, Jayasinghe R. Attitudes, confidence in practices and perceived barriers towards the promotion of tobacco cessation among clinical dental undergraduates in sri lanka. Asian Pac J Cancer Care. 2021;6:175–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross H, Husain MJ, Kostova D, Xu X, Edwards SM, Chaloupka FJ, et al. Approaches for controlling illicit tobacco trade--nine countries and the european union. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(20):547–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joossens L, Raw M. Progress in combating cigarette smuggling: Controlling the supply chain. Tob Control. 2008;17(6):399–404. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.026567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joossens L, Merriman D, Ross H, Raw M. The impact of eliminating the global illicit cigarette trade on health and revenue. Addiction. 2010;105(9):1640–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schröder d. Combatting illicit tobacco trade: What is the role of eu law enforcement training? Tob prev cessat [internet] [2021 mar 5;7(march):1–2]. Available from: http://www.Tobaccopreventioncessation.Com/combatting-illicit-tobacco-trade-what-is-the-role-of-eu-law-enforcement-training,133572,0,2.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.