Abstract

Background.

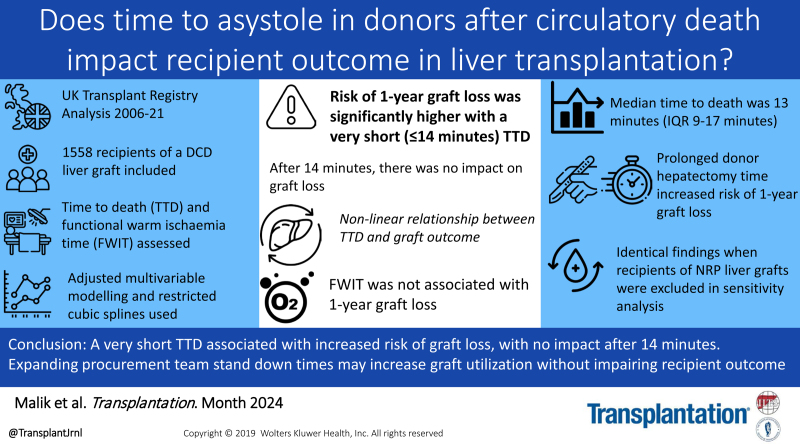

The agonal phase can vary following treatment withdrawal in donor after circulatory death (DCD). There is little evidence to support when procurement teams should stand down in relation to donor time to death (TTD). We assessed what impact TTD had on outcomes following DCD liver transplantation.

Methods.

Data were extracted from the UK Transplant Registry on DCD liver transplant recipients from 2006 to 2021. TTD was the time from withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment to asystole, and functional warm ischemia time was the time from donor systolic blood pressure and/or oxygen saturation falling below 50 mm Hg and 70%, respectively, to aortic perfusion. The primary endpoint was 1-y graft survival. Potential predictors were fitted into Cox proportional hazards models. Adjusted restricted cubic spline models were generated to further delineate the relationship between TTD and outcome.

Results.

One thousand five hundred fifty-eight recipients of a DCD liver graft were included. Median TTD in the entire cohort was 13 min (interquartile range, 9–17 min). Restricted cubic splines revealed that the risk of graft loss was significantly greater when TTD ≤14 min. After 14 min, there was no impact on graft loss. Prolonged hepatectomy time was significantly associated with graft loss (hazard ratio, 1.87; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-2.83; P = 0.003); however, functional warm ischemia time had no impact (hazard ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.44-2.27; P > 0.9).

Conclusions.

A very short TTD was associated with increased risk of graft loss, possibly because of such donors being more unstable and/or experiencing brain stem death as well as circulatory death. Expanding the stand down times may increase the utilization of donor livers without significantly impairing graft outcome.

INTRODUCTION

Liver transplantation remains the standard of care for patients with end-stage liver disease. As a consequence, more patients are eligible to be listed with demand for liver transplantation far exceeding the number of available deceased donor liver grafts, particularly for grafts donated after brain stem death (DBD). In the United Kingdom, over the past 15 y, there has been a steady increase in liver grafts donated after circulatory death,1-4 and the need to use these grafts has become essential because of increasing pressure on the deceased donor liver waiting list. From 2017, there has been a steady rise in the number of patients on the active liver transplant list in the United Kingdom (excluding the COVID pandemic in 2020–2021). In 2022–2023, 697 patients were awaiting a deceased donor liver graft, representing a 94% increase in the waiting list compared with 2017–2018.5 Methods to optimize liver graft utilization are necessary to prevent excess deaths on the waiting list, balancing against the risk of morbidity and mortality posttransplantation.

Early single-center studies demonstrated inferior outcomes,6,7 and donor after circulatory death (DCD) liver grafts historically had higher discard rates because of the perceived risks regarding biliary complications and recipient morbidity2,8-12 when compared with DBD liver grafts. However, there are numerous reports demonstrating DCDs are an acceptable and growing source of liver grafts with comparable outcomes to DBD grafts in selected circumstances1,2,4,13 and can particularly benefit UK patients with hepatocellular carcinoma14 or variant syndromes who have limited access to transplantation because of prioritization practices.15 Although posttransplant outcomes may be inferior with DCD versus DBD livers, overall survival is improved by accepting a DCD offer compared with remaining on the waiting list.15

Inferior outcomes are thought to be secondary to the prolonged donor warm ischemia time (DWIT). DWIT consists of an agonal phase (withdrawal of treatment to asystole) and an asystolic phase (from asystole until cold perfusion of the liver graft). Functional warm ischemia time (FWIT) is thought to capture the true ischemic time a liver graft experiences and is defined as either the time from donor systolic blood pressure dropping below 50 mm Hg or oxygen saturations (Spo2) below 70% to the time of cold aortic perfusion. In the UK retrieval of the DCD liver graft is usually abandoned if FWIT exceeds 30 min,16 similar to the American Society of Transplant Surgeons guidelines.17 To mitigate against the potentially increased ischemic injury (which could impact posttransplant outcomes), a “super-rapid” organ retrieval is performed, where the aorta is cannulated and flushed first to cool the organs followed by dissection and organ recovery,18,19 and there is evidence that optimizing donor hepatectomy time may reduce the risk of posttransplant graft loss.20,21

Following withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (WOLST), donor time to asystole (referred to as time to death [TTD]) can differ significantly between donors, leading to a variable degree of warm ischemic damage to the liver graft.22 Donors may demonstrate a gradual decline in hemodynamic parameters, maintain stable hemodynamics followed by a rapid decline, or decline rapidly following WOLST.23 Resource constraints limit the ability and efficacy of organ procurement teams waiting indefinitely for donor asystole. Additionally, a prolonged TTD may result in a sustained period of hypotension, hypoxia, and/or vascular shunting away from abdominal viscera, which may not be captured by systolic blood pressure or Spo2 measurements. A preclinical DCD porcine model demonstrated impaired hepatic perfusion with associated ischemia before cessation of cardiac electrical activity.24

We aimed to ascertain the relationship between donor TTD and recipient outcomes in DCD liver transplantation. We hypothesize that a prolonged donor TTD is associated with worse recipient outcomes as a surrogate to increased ischemic injury.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Setting

We performed a retrospective review of adult (≥17 y) DCD liver graft recipients in the United Kingdom from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2021. As this was a retrospective review of anonymized data, ethical approval was not required. Data were extracted from a registry prospectively maintained by National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) from all 7 UK liver transplant centers. Recipients were included if they were receiving a whole liver graft. Multiorgan and split transplant recipients were excluded. Eligibility for listing for a liver graft is based on the UK Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (UKELD) score (based on serum sodium, creatinine, bilirubin, and prothrombin time), first introduced in 2008.25 Eligibility is defined by a score >49 (from 2013), with specific criteria for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma or variant syndromes, where the UKELD score may not entirely reflect the risk of waiting list mortality. For recipients before 2008, UKELD scores immediately pretransplantation were calculated using submitted data on serum sodium, creatinine, bilirubin, and prothrombin time.

All donors were controlled Maastricht category III. DCD liver grafts are allocated to one of 7 liver transplant centers in the United Kingdom, with recipients being chosen at the discretion of the transplanting team.

Organ Retrieval and Transplantation

In the United Kingdom, following the onset of asystole, a 5-min no-touch (standoff)17 period is observed for confirmation of donor death. Before confirmation of death, medical interventions to facilitate organ donation and retrieval cannot be performed (eg, systemic heparinization or vascular cannulation). Once death has been confirmed and the 5-min no-touch period has been observed, organ retrieval is commenced. Steatosis was graded as “none,” “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe” purely based on the subjective assessment of the retrieval surgeon—liver biopsy is not part of the national protocol assessment. Normothermic regional perfusion (NRP) was used variably by the organ retrieval teams. Implanting centers variably used normothermic machine perfusion and hypothermic machine perfusion before transplantation; however, the standard in this time period was static cold storage

Definitions

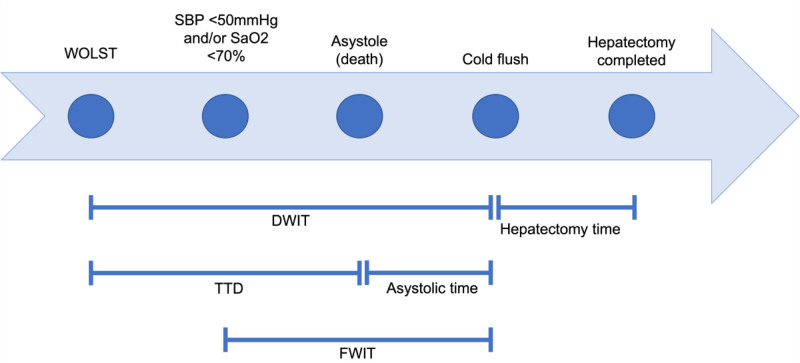

TTD was defined as the time from WOLST to asystole (Figure 1), and donor hepatectomy time was defined as the time from cold perfusion to the end of hepatectomy. FWIT was the time from systolic blood pressure dropping below 50 mm Hg and/or Spo2 dropping below 70% to cold perfusion (based on the UK definition16). The 5-min no-touch period is included in the FWIT. Cold ischemic time was the time from in situ cold perfusion to when the liver graft was removed from ice before implantation. Reperfusion time (second warm ischemic time) was the time from the liver being taken out of ice to reperfusion of the liver graft in the recipient. Primary nonfunction (PNF) was defined as the need for retransplantation within 14 d of initial liver implantation. Our primary outcome was 1-y graft survival, censored for death with a functioning graft. Graft failure was defined as retransplantation or death because of liver failure. The NHSBT registry records biliary complications occurring within 3 mo of liver transplantation, beyond 3 mo the incidence of biliary complications is not available.

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of events following WOLST in a donor after circulatory. DWIT, donor warm ischemia time; FWIT, functional warm ischemia time; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TTD, time to death; WOLST, withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R v4.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables are presented as median values with interquartile range and were compared using the t test or Mann-Whitney U test. Chi-squared tests were performed to compare categorical variables. Missing data were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations using 10 imputed datasets. Potential predictors for 1-y graft survival and 1-y recipient mortality were fitted into a hierarchal Cox proportional hazards regression model with recipient center as the random effect. TTD and donor hepatectomy time were kept as continuous variables and log-transformed before inclusion in models because of the skew of the residuals. A sensitivity analysis was performed examining if donor TTD >30 min (as a categorical predictor) had any impact on recipient outcomes. Sensitivity analyses removing recipients of grafts where the donor had undergone abdominal NRP or thoracoabdominal NRP (TA-NRP) were performed. TTD and FWIT were also examined in separate models to avoid multicollinearity within the analyses. A crude and adjusted Cox proportional hazard model was plotted against the primary predictor of interest, TTD, using restricted cubic splines (4 knots at 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles) for which the median or mode of all imputed datasets was used. All statistical tests were 2-tailed, with significance set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Donor, Recipient, and Retrieval Characteristics

From January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2021, 1558 adult patients underwent DCD liver transplantation (of whom 12 were super-urgent recipients and 14 were undergoing repeat liver transplantation, demographics are presented in Table S1 [SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/D69] for the entire cohort, and broken down by TTD category in Table S2 [SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/D69]). TTD was not available in 533 recipients (34.2%). Median TTD in the whole cohort was 13 min (9–17 min), median asystolic time was 13 min (11–15 min), median donor hepatectomy time was 37 min (29–47 min), median FWIT was 17 min (14–20 min), median cold ischemic time was 441 min (381–503 min), and median reperfusion time was 36 min (28–44 min). TTD exceeded 30 min in 43 donors (4.2%), with a median TTD 40 min (interquartile range, 35–61 min) in this subgroup. Table S3 (SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/D69) provides a further comparison of variables between donors with TTD ≤30 min and donors with TTD >30 min, and Table S4 (SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/D69) provides a comparison of variables between donors with a FWIT ≤30 min and donors with a FWIT >30 min. NRP was performed in 41 donors and TA-NRP was performed in 10 donors.

Recipient Outcomes

Overall 90-d, 1-y, 3-y, and 5-y transplant survival was 92.3%, 88.5%, 82.7%, and 78.6%, respectively. Overall 90-d, 1-y, 3-y, and 5-y patient survival was 95.5%, 93.1%, 86.9%, and 81.0%, respectively. The incidence of PNF was 52 (5.1%). Postoperative bile leak occurred in 52 recipients, of whom 20 (2.0%) underwent a surgical intervention and 24 (2.4%) underwent a radiological intervention. Biliary strictures occurred in 63 recipients (6.3%) within 3 mo of DCD liver transplantation. Graft loss or recipient mortality within 30 d occurred in 86 patients (8.4%). Recipient outcomes are broken down by TTD category and are presented in Table 1, with no significant differences between categories.

TABLE 1.

Recipient outcomes broken down by TTD

| Variable | Entire cohort (n = 1025, 100%), n (%) | TTD ≤10 min (n = 347, 33.9%), n (%) | TTD 10–16 min (n = 382, 37.3%), n (%) | TTD >16 min (n = 296, 28.9%), n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNF | 52 (5.1) | 23 (6.6) | 14 (3.7) | 15 (5.1) | 0.193 |

| Postoperative bile leak | 52 (5.1) | 12 (3.5) | 22 (5.8) | 18 (6.1) | 0.382 |

| Managed surgically | 20 (2.0) | 4 (1.2) | 7 (1.8) | 9 (3.0) | |

| Managed radiologically | 24 (2.3) | 6 (1.7) | 10 (2.6) | 8 (2.7) | |

| Posttransplant biliary stricture | 63 (6.3) | 17 (5.0) | 25 (6.7) | 21 (7.3) | 0.451 |

| 30-d mortality or graft loss | 86 (8.4) | 39 (11.3) | 25 (6.6) | 22 (7.5) | 0.059 |

PNF, primary nonfunction; TTD, time to death.

Impact of Donor Time to Death on Recipient Outcomes

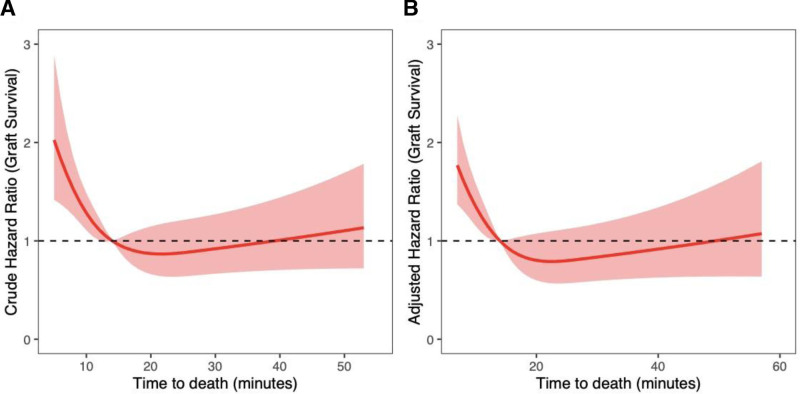

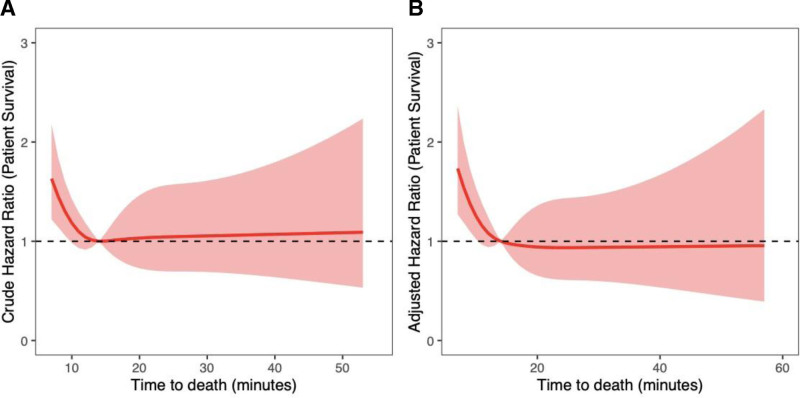

Donor TTD was not significantly associated with liver graft failure (hazard ratio [HR], 0.79; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53-1.18; P = 0.2) or increased recipient mortality at 1 y (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.53-1.32; P = 0.4) on multivariable analysis (Table 2). Increasing hepatectomy time was significantly associated with worse 1-y graft survival (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.23-2.83; P = 0.003) but was not significantly associated with 1-y recipient mortality (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.82-2.48; P = 0.2). Recipient age was the only significant predictor of 1-y patient mortality (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.06; P = 0.002). Severe liver graft steatosis as a predictor of graft loss at 1 y approached statistical significance (HR, 3.55; 95% CI, 0.99-12.7; P = 0.052). On sensitivity analysis TTD >30 min was not significantly associated with graft survival (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.34-2.27; P = 0.8) or recipient survival (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.38-3.52; P = 0.8) at 1 y. Predictors of graft loss and recipient mortality were no different on sensitivity analyses removing recipients of grafts that had undergone NRP or TA-NRP (analyses not shown). When modeling the nonlinear relationship between graft survival and TTD, risk of graft loss significantly increased with TTD ≤14 min (Figure 2). After 14 min, TTD did not have a significant impact on graft survival. Table S5 (SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/D69) shows donor and recipient characteristics, comparing TTD ≤14 min with TTD >14 min. Similarly, recipient mortality was significantly higher when donor TTD was ≤7 min (Figure 3), with no significant differences after 7 min.

TABLE 2.

Multivariable analysis of potential predictors of 1-y graft loss and 1-y recipient mortality modeling time to death

| Variable | 1-y graft loss | 1-y recipient mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| TTD, min | 0.79 (0.53-1.18) | 0.2 | 0.84 (0.53-1.32) | 0.4 |

| Recipient male sex | 1.06 (0.75-1.50) | 0.7 | 1.17 (0.73-1.87) | 0.5 |

| Recipient age, y | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | 0.7 | 1.04 (1.01-1.06) | 0.002 |

| UKELD score | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 0.8 | 1.00 (0.96-1.04) | 0.8 |

| Donor cause of death | ||||

| Other | – | – | – | – |

| Cardiovascular | 3.78 (0.98-14.6) | 0.054 | 1.85 (0.39-8.64) | 0.4 |

| Intracranial | 1.63 (0.51-5.27) | 0.4 | 0.98 (0.30-3.25) | >0.9 |

| Respiratory | 2.58 (0.59-11.2) | 0.2 | 1.43 (0.27-7.47) | 0.7 |

| Trauma | 2.49 (0.71-8.74) | 0.2 | 0.97 (0.24-3.87) | >0.9 |

| Donor male sex | 1.09 (0.79-1.51) | 0.6 | 1.07 (0.70-1.63) | 0.8 |

| Donor age, y | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.2 | 1.00 (0.99-1.02) | 0.8 |

| Donor BMI, kg/m2 | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 0.2 | 1.04 (1.00-1.09) | 0.067 |

| Donor hypertension | 1.28 (0.89-1.83) | 0.2 | 0.88 (0.54-1.44) | 0.6 |

| Liver graft steatosis | ||||

| None | – | – | – | – |

| Mild | 0.90 (0.63-1.29) | 0.6 | 1.34 (0.89-2.09) | 0.2 |

| Moderate | 1.42 (0.88-2.32) | 0.2 | 1.13 (0.55-2.34) | 0.7 |

| Severe | 3.55 (0.99-12.7) | 0.052 | 3.77 (0.82-17.4) | 0.087 |

| Cold ischemia time, min | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.13 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.7 |

| Donor hepatectomy time, min | 1.87 (1.23-2.83) | 0.003 | 1.43 (0.82-2.48) | 0.2 |

–, reference category for analysis; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; TTD, time to death; UKELD, UK Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

FIGURE 2.

Risk of graft loss is significantly higher in recipients of grafts from donors with TTD ≤14 min. After 14 min, there was no significant impact on graft outcome. Restricted cubic splines modeling (A) unadjusted graft survival and (B) adjusted graft survival as a function of time to death.

FIGURE 3.

Risk of mortality was significantly greater in recipients of grafts with TTD ≤7 min. After 7 min, there was no significant impact on outcome. Restricted cubic splines modeling (A) unadjusted patient survival and (B) adjusted patient survival as a function of time to death.

Impact of Donor Functional Warm Ischemia Time on Recipient Outcome

In separate models donor FWIT was not significantly associated with 1-y graft failure (HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.44-2.27; P > 0.9) or 1-y recipient mortality (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.19-1.16; P = 0.10) on multivariable analysis (Table 3). Similar to the TTD model, donor hepatectomy time was significantly associated with graft failure at 1 y (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.25-2.87; P = 0.003) but not with recipient mortality at 1 y (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 0.84-2.52; P = 0.2). Severe steatosis in the liver graft predicted graft loss at 1 y (HR, 3.56; 95% CI, 1.01-12.5; P = 0.048) but was not significantly associated with recipient mortality at 1 y (HR, 3.90; 95% CI, 0.83-18.3; P = 0.084). Recipient age (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01-1.06; P = 0.003) and donor body mass index (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.00-1.10; P = 0.049) were associated with 1-y recipient mortality. Again, predictors of graft loss and recipient mortality were no different on sensitivity analyses removing recipients of grafts that had undergone NRP or TA-NRP (analyses not shown). Time to onset of functional warm ischemia was not associated with graft loss or recipient mortality at 1 y (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.77-1.35; P = 0.9). Kaplan-Meier curves comparing graft and patient survival by FWIT are presented in Figures S1 and S2 (SDC, http://links.lww.com/TP/D69).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable analysis of potential predictors of 1-y graft loss and 1-y recipient mortality modeling functional warm ischemia time

| Variable | 1-y graft loss | 1-y recipient mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| FWIT, min | 1.00 (0.44-2.27) | >0.9 | 0.47 (0.19-1.16) | 0.10 |

| Recipient male sex | 1.06 (0.75-1.50) | 0.7 | 1.16 (0.72-1.85) | 0.5 |

| Recipient age, y | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | 0.6 | 1.04 (1.01-1.06) | 0.003 |

| UKELD score | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 0.9 | 0.99 (0.96-1.04) | 0.8 |

| Donor cause of death | ||||

| Other | – | – | – | – |

| Cardiovascular | 3.82 (1.00-14.7) | 0.051 | 1.98 (0.42-9.24) | 0.4 |

| Intracranial | 1.54 (0.48-4.91) | 0.5 | 0.94 (0.29-3.09) | >0.9 |

| Respiratory | 2.32 (0.53-10.1) | 0.3 | 1.53 (0.29-8.02) | 0.6 |

| Trauma | 2.33 (0.67-8.12) | 0.2 | 0.89 (0.23-3.53) | 0.9 |

| Donor male sex | 1.13 (0.81-1.56) | 0.5 | 1.08 (0.71-1.65) | 0.7 |

| Donor age, y | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.3 | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | >0.9 |

| Donor BMI, kg/m2 | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 0.14 | 1.05 (1.00-1.10) | 0.049 |

| Donor hypertension | 1.28 (0.89-1.83) | 0.2 | 0.86 (0.53-1.41) | 0.5 |

| Liver graft steatosis | ||||

| None | – | – | – | – |

| Mild | 0.93 (0.65-1.33) | 0.7 | 1.38 (0.89-2.14) | 0.15 |

| Moderate | 1.41 (0.87-2.30) | 0.2 | 1.28 (0.62-2.64) | 0.5 |

| Severe | 3.56 (1.01-12.5) | 0.048 | 3.90 (0.83-18.3) | 0.084 |

| Cold ischemia time, min | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.11 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.8 |

| Donor hepatectomy time, min | 1.89 (1.25-2.87) | 0.003 | 1.45 (0.84-2.52) | 0.2 |

–, reference category for analysis; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; FWIT, functional warm ischemia time; HR, hazard ratio; UKELD, UK Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

Although use of machine preservation is not routinely collected by NHSBT, we recognize that its use has increased particularly in the past 5 y. To address this, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding DCD liver graft recipients’ post-2017 (analysis not shown). Predictors of graft loss and recipient mortality were no different in this analysis, and FWIT was not identified as a predictor of graft loss (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.18-1.18; P = 0.11) or recipient mortality (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.35-1.61; P = 0.5).

DISCUSSION

We found prolonged TTD and FWIT were not significantly associated with graft loss or recipient mortality at 1 y based on their current definition, suggesting that expansion of the 30-min cutoff time for FWIT (or redefinition) may be achieved without harming recipient outcome provided donor hepatectomy time is kept short. We identified that TTD had a nonlinear relationship with recipient outcome at 1 y, with graft loss significantly worse with liver grafts from donors with TTD ≤14 min and no impact beyond 14 min. There was no difference between recipients of grafts with a longer TTD (>30 min) compared with <30 min including incidence of PNF, postoperative bile leak, posttransplantation biliary stricture at 3 mo, and 30-d posttransplantation graft loss or mortality. However, NHSBT only routinely collects data on biliary complications up to 3 mo postliver transplantation; therefore, we cannot comment on what impact TTD and FWIT may have on biliary complications beyond 3 mo postliver transplantation.

A retrospective single center study from the United States26 compared survival in kidney transplant recipients by TTD category and concluded that by expanding the cutoff from 1 to 2 h increased kidney utilization by up to 10% without impairing recipient outcome. A UK-based study in 2006 also found no difference in short-term outcome in kidney grafts retrieved from donors where the TTD exceeded 5 h.27 More recently, a retrospective study investigated outcomes from 101 DCD liver grafts retrieved from donors with extended agonal times who underwent NRP.28 The authors reported no difference when comparing recipient or transplant survival in donors with TTD <60 min with donors who had a TTD 60 min and did not identify TTD as an independent predictor of outcome on Cox regression. There was no comment on the outcome of DCD grafts from donors with a very short TTD. Additionally, the Cox proportional hazards model assumes that each variable provides a linear contribution to the model, which is unlikely to be true for TTD based on our analyses. However, NRP is likely to have a protective effect from ischemic injury towards the liver graft, with increasing nonrandomized evidence suggesting lower rates of ischemic cholangiopathy compared with non-NRP liver grafts.29-34

FWIT has previously been associated with posttransplantation biliary complications.10,35-38 It is unclear whether hypotension or hypoxia is a more significant determinant.16,22 Multiple definitions of FWIT exist,16,22,35,37,39-41 further confounding the available evidence and comparisons between studies. The International Liver Transplantation Society Consensus Conference on DWIT in DCD liver transplantation proposed that FWIT should be defined as from the time Spo2 drops below 80% and/or mean arterial pressure falls below 60 mm Hg based on previous studies into tissue perfusion in sepsis.16,42,43 It is unclear what impact, if any, employing this definition would have on the number of DCD liver grafts retrieved and posttransplant outcome. However, there is no data available to suggest that donor Spo2 < 80% is physiologically equivalent to a mean arterial pressure <60 mm Hg, further confounding the issue. Pulse oximetry may have reduced accuracy in critically ill patients (and during the agonal phase) with low peripheral perfusion44; therefore, recorded saturations may not accurately represent donor physiology. However, a retrospective analysis of 1114 DCD liver transplant recipients explored the relationship between donor hypoxia time (defined as from the onset of Spo2 < 80% in the donor to aortic cross clamp) and graft outcome.45 The authors identified a nonlinear relationship, with increasing risk of graft loss up to 16 min, after which risk plateaued. Therefore, an over-reliance on FWIT may detrimentally impact graft utilization, with implications for waiting list outcome.

The precise number of donors that do not proceed to liver graft retrieval because of a prolonged TTD and/or FWIT (based on current criteria) exceeding the 30-min cutoff in the United Kingdom is unknown. However, in the 2021/2022 financial year, 49.3% circulatory death donors in the United Kingdom did not undergo liver graft retrieval,5 demonstrating a wide gap between donation and utilization of DCD liver grafts. For obvious reasons, it is not possible to know what the outcome would have been for liver grafts that were declined because of a prolonged donor TTD or FWIT. However, prospective evaluation of recipients of liver grafts from donors with a prolonged TTD and/or FWIT, with well-defined endpoints, could help determine what impact expansion of cutoff times has on recipient outcome. A randomized control trial in this context could be very informative but would be difficult to design and maintain clinical equipoise as the decision to implant a liver graft is multifactorial. Furthermore, if a liver graft from such a donor is retrieved, undergoes ex situ machine perfusion, and demonstrates adequate functional performance, this may introduce bias into the trial through potential reconditioning of the liver graft ameliorating the associated potential ischemic injury. Redefining FWIT based on the International Liver Transplantation Society recommendation may lead to fewer DCD liver grafts being retrieved because of the more stringent criteria, however, as the evidence base favoring in situ and/or ex situ perfusion increases29,31,46-49 (with use of such technologies becoming more widespread), a reevaluation of definitions and practice may be required to maximize organ utilization.

Hepatectomy time was the strongest predictor of graft failure at 1 y in our analysis in both the TTD model and FWIT model. This is consistent with previous studies,20,21 demonstrating that warm ischemic injury is likely to continue following cold aortic perfusion until the liver graft is placed in ice. The core temperature of the liver has been shown to demonstrate a rapid decline on aortic perfusion, followed by a plateau for the remainder of the dissection50 with a variable degree of ischemic injury depending on the duration of the hepatectomy and susceptibility of the liver graft to ischemia. In a porcine model, liver grafts reached a core temperature of 0–1 °C only after 3 h of preservation suggesting that up to that point graft metabolism will continue, leading to ischemic injury.50 Hepatectomy time may be prolonged by increased donor body mass index limiting access, previous surgery in the donor, or simultaneous cardiothoracic retrieval, with a previous study into hepatectomy time and posttransplantation outcomes recommending a 1-h target for “knife to skin and liver placement in ice box.”20 A retrospective study on recipients in the Eurotransplant area51 identified incremental increase in implantation time (defined as time from liver out of ice to restoration of blood flow to the graft in the recipient) as a significant predictor of graft loss. This was not replicated in our study, with reperfusion time not significantly associated with outcome during model-fitting (analysis not presented). Implantation time is likely to be a surrogate of other confounding variables which may independently be associated with outcome, such as need for multiple arterial anastomoses and/or reconstruction, and recipient portal vein thromboses. Additionally, recipients with missing data were excluded from the Eurotransplant analyses, further confounding the analysis. Identification of target times for donor hepatectomy and reperfusion in the recipient would be beneficial but were beyond the scope of our work.

The impact of TTD on posttransplantation outcome may be affected by the hemodynamic trajectory of the donor following WOLST. A single-center retrospective study examined 87 DCD liver graft recipients, categorizing donor livers into 1 of 3 groups based on their hemodynamic trajectory following treatment withdrawal.23 The study found that liver grafts from donors who demonstrated a gradual decline in hemodynamic parameters (rather than an immediate rapid decline or a period of stability followed by rapid decline following WOLST) with a prolonged agonal phase demonstrated worse posttransplantation graft outcomes. This differs from our observation that liver grafts from donors who rapidly decline following WOLST demonstrate worse recipient outcomes. Transforming continuous variables into categorical variables results in a loss of information and may mask nonlinear relationships between variables,52 possibly accounting for the observed difference.

DCDs with very short TTD may demonstrate worse graft and recipient survival as such donors may be more unstable and possibly more reliant on organ support (with vasopressor use leading to splanchnic ischemia), which could lead to pre-withdrawal ischemic damage. This is supported by a prospective multicenter observational study of DCD donors in the United Kingdom identifying predictors of TTD after withdrawal of treatment.53 The authors reported that inotrope use, a higher fraction of inspired oxygen and younger age were all predictors of a shorter TTD. Additionally, DCDs demonstrating a very short TTD post-WOLST may well have been brain stem dead and suffering with the associated proinflammatory state.54,55 Data on donor treatment before organ retrieval was not available; therefore, we were unable to analyze how such factors may impact TTD in our cohort. Despite our observation that a rapid TTD was associated with worse graft survival, this should not be used in isolation as an absolute contraindication to retrieval and transplantation (particularly in the context of viability assessment during ex situ machine perfusion) but taken into account alongside all real variables to risk stratify potential liver grafts. Particularly in the context of viability assessment before transplantation.

Further exploration into the cytokine profile and clinical characteristics of DCDs who rapidly decline post-WOLST may provide further insight into why a very short TTD may be associated with worse graft survival. Elucidating a targetable pathway or mechanism may have implications in ameliorating ischemic and/or inflammatory injury in donors to improve posttransplant graft outcome. Currently, in the UK medical interventions that do not directly benefit the donor before death is diagnosed are not legal; however, a “Donation Actions Framework” has been published,56 which allows some measures that may facilitate donation wishes to be implemented.

Notably, in contrast to our presented analyses, other studies have found cold ischemia time to be a significant predictor of posttransplantation outcome. Farid et al20 found that a cold ischemia time exceeding 8 h was significantly associated with PNF and graft loss in DCD liver transplantation. It is likely that ischemic injury has an incremental impact in DCD liver grafts, with variable cutoff values for ischemic times suited to the specific level of risk acceptable to transplant clinicians and waiting list patients. Interpretation and management of risk regarding accepting a DCD liver graft was investigated in a Markov model simulation, determining that in patients with a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score >15 acceptance of a DCD liver graft led to a better outcome compared with remaining on the waiting list for a DBD liver graft offer.57 In certain waiting list patients, transplantation of a liver graft with a prolonged FWIT (exceeding 30 min) may be acceptable in the context of a sick patient at risk of dropout or waiting list mortality. Novel preservation methods are likely to prove pivotal in expanding risk tolerance with expanded FWITs, as NRP, normothermic machine perfusion, hypothermic machine perfusion, or a combination of these methods may mitigate against (or eliminate)29,31,46-49 the ischemic injury associated with a prolonged FWIT.

We acknowledge the following limitations of our study. As a retrospective analysis of registry data, missing data were inevitable with TTD missing for one-third of recipients. We believe that the data was missing at random and performed multiple imputation for missing data to mitigate this impact. The reason for missing data is likely to be because of the relevant field not being completed on the registry forms, which was unavoidable in a retrospective registry analysis. It was not possible to capture use of ex situ liver graft hypothermic or normothermic perfusion at the transplanting center, which may represent unmeasured confounders. Liver grafts from donors with a prolonged TTD may have undergone normothermic machine perfusion at the recipient center and transplanted following viability assessment; however, it was not possible to capture this data. However, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding patients who were transplanted post-2017 (when use of ex situ machine perfusion increased) with no difference in our results identified. Variations in hemodynamic parameters following WOLST were not recorded and may provide further information on the degree of ischemic injury to the liver graft. The inevitable limitation of the present analyses is the selection bias associated with the retrospective nature of the study, and as such, further prospective studies would be useful.

This large dataset demonstrates that prolonged TTD does not impact graft loss or recipient mortality at 1-y posttransplantation and donor teams should consider waiting up to 40 min from the onset of FWIT before abandoning the DCD liver. Of note, we identified that a very short donor TTD was associated with worse 1-y graft loss and recipient mortality, and we propose that such donors may have also undergone brain stem death with its associated proinflammatory state. Further investigation of this finding is warranted and may aid decision-making regarding graft utilization. Prolonged hepatectomy time appears to be harmful to outcome and should be considered in assessment of liver grafts for implantation. Prospective study is warranted to determine whether liver grafts with a prolonged FWIT (based on current definition) can be transplanted without adversely impacting recipient outcome, particularly where hepatectomy time is optimized. With increased use of novel in situ and ex situ preservation methods aimed at reducing ischemic injury, the definition of FWIT and the current 30-min threshold may require reevaluation to maximize DCD liver graft utilization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Christopher Watson (Consultant Transplant Surgeon) for providing the donor identification numbers for liver grafts that underwent NRP. Also, the authors thank Ms Jennifer Mehew (statistician at NHSBT) for reviewing the statistical methods employed in this study. Finally, the authors thank the UK Liver Advisory Group for providing the data for this study.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This study is funded by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Blood and Transplant Research Unit in Organ Donation and Transplantation (NIHR203332), a partnership between National Health Service Blood and Transplant, University of Cambridge, and Newcastle University.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Previous Presentation: This work was presented at the British Transplantation Society Meeting in March 2023 in Edinburgh, United Kingdom as a poster and as an oral presentation at the European Society for Organ Transplantation Congress in September 2023 in Athens, Greece.

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of National Institute of Health and Care Research, National Health Service Blood and Transplant, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

A.K.M., S.J.T., and C.H.W. were involved in concept and design. A.K.M., S.J.T., C.V., S.A.W., and C.H.W. were involved in data analysis and interpretation. A.K.M., S.J.T., C.V., B.M., R.O., and C.H.W. were involved in drafting of article. A.K.M., S.J.T., C.V., B.M., R.O., R.F., A.O.A., I.S.C., S.A.W., D.M.M., and C.H.W. were involved in critical review of article. A.K.M., S.J.T., C.V., B.M., R.O., R.F., A.O.A., I.S.C., S.A.W., D.M.M., and C.H.W. were involved in revision of article. A.K.M., S.J.T., C.V., and C.H.W. were involved in preparation of final article for submission.

The data used in preparation of this article is under the jurisdiction of National Health Service Blood and Transplant, therefore, cannot be provided by the authors on request. A formal data request to National Health Service Blood and Transplant is required for data release.

Supplemental digital content (SDC) is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.transplantjournal.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wallace D, Cowling TE, Suddle A, et al. National time trends in mortality and graft survival following liver transplantation from circulatory death or brainstem death donors. Br J Surg. 2021;109:79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaghan CJ, Charman SC, Muiesan P, et al. ; UK Liver Transplant Audit. Outcomes of transplantation of livers from donation after circulatory death donors in the UK: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giorgakis E, Ivanics T, Khorsandi SE, et al. Disparities in the use of older donation after circulatory death liver allografts in the United States versus the United Kingdom. Transplantation. 2022;106:e358–e367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croome KP, Lee DD, Keaveny AP, et al. Improving national results in liver transplantation using grafts from donation after cardiac death donors. Transplantation. 2016;100:2640–2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health Service Blood and Transplant. Annual report on the National Organ Retrieval Service (NORS) report for 2021/2022. Available at https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/27441/annual-report-on-the-national-organ-retrieval-service-202122.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Vera ME, Lopez-Solis R, Dvorchik I, et al. Liver transplantation using donation after cardiac death donors: long-term follow-up from a single center. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foley DP, Fernandez LA, Leverson G, et al. Donation after cardiac death: the University of Wisconsin experience with liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2005;242:724–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitarch Martinez M, Sanchez Perez B, Leon Diaz FJ, et al. Donation after cardiac death in liver transplantation: an additional source of organs with similar results to donation after brain death. Transplant Proc. 2019;51:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hessheimer AJ, Cardenas A, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, et al. Can we prevent ischemic-type biliary lesions in donation after circulatory determination of death liver transplantation? Liver Transpl. 2016;22:1025–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du Z, Dong S, Lin P, et al. Warm ischemia may damage peribiliary vascular plexus during DCD liver transplantation. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:758–763. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muiesan P, Fisher S. The bile duct in donation after cardiac death donor liver transplant. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2014;19:447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White SA, Prasad KR. Liver transplantation from non-heart beating donors. BMJ. 2006;332:376–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jay C, Ladner D, Wang E, et al. A comprehensive risk assessment of mortality following donation after cardiac death liver transplant—an analysis of the national registry. J Hepatol. 2011;55:808–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace D, Walker K, Charman S, et al. Assessing the impact of suboptimal donor characteristics on mortality after liver transplantation: a time-dependent analysis comparing HCC with non-HCC patients. Transplantation. 2019;103:e89–e98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor R, Allen E, Richards JA, et al. ; Liver Advisory Group to NHS Blood and Transplant. Survival advantage for patients accepting the offer of a circulatory death liver transplant. J Hepatol. 2019;70:855–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalisvaart M, Croome KP, Hernandez-Alejandro R, et al. Donor warm ischemia time in DCD liver transplantation-working group report from the ILTS DCD, liver preservation, and machine perfusion consensus conference. Transplantation. 2021;105:1156–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reich DJ, Mulligan DC, Abt PL, et al. ; ASTS Standards on Organ Transplantation Committee. ASTS recommended practice guidelines for controlled donation after cardiac death organ procurement and transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2004–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casavilla A, Ramirez C, Shapiro R, et al. Experience with liver and kidney allografts from non-heart-beating donors. Transplantation. 1995;59:197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SC, Foley DP. Strategies to improve the utilization and function of DCD livers. Transplantation. 2024;108:625–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farid SG, Attia MS, Vijayanand D, et al. Impact of donor hepatectomy time during organ procurement in donation after circulatory death liver transplantation: the United Kingdom experience. Transplantation. 2019;103:e79–e88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jochmans I, Fieuws S, Tieken I, et al. The impact of hepatectomy time of the liver graft on post-transplant outcome: a Eurotransplant cohort study. Ann Surg. 2019;269:712–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalisvaart M, de Haan JE, Polak WG, et al. Onset of donor warm ischemia time in donation after circulatory death liver transplantation: hypotension or hypoxia? Liver Transpl. 2018;24:1001–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Firl DJ, Hashimoto K, O’Rourke C, et al. Role of donor hemodynamic trajectory in determining graft survival in liver transplantation from donation after circulatory death donors. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:1469–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhee JY, Alroy J, Freeman RB. Characterization of the withdrawal phase in a porcine donation after the cardiac death model. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1169–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neuberger J, Gimson A, Davies M, et al. ; Liver Advisory Group. Selection of patients for liver transplantation and allocation of donated livers in the UK. Gut. 2008;57:252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scalea JR, Redfield RR, Arpali E, et al. Does DCD donor time-to-death affect recipient outcomes? Implications of time-to-death at a high-volume center in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sohrabi S, Navarro A, Asher J, et al. Agonal period in potential non-heart-beating donors. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2629–2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richards JA, Gaurav R, Upponi SS, et al. Outcomes of livers from donation after circulatory death donors with extended agonal phase and the adjunct of normothermic regional perfusion. Br J Surg. 2023;110:1112–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hessheimer AJ, de la Rosa G, Gastaca M, et al. Abdominal normothermic regional perfusion in controlled donation after circulatory determination of death liver transplantation: outcomes and risk factors for graft loss. Am J Transplant. 2022;22:1169–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oniscu GC, Mehew J, Butler AJ, et al. Improved organ utilization and better transplant outcomes with in situ normothermic regional perfusion in controlled donation after circulatory death. Transplantation. 2023;107:438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson CJE, Hunt F, Messer S, et al. In situ normothermic perfusion of livers in controlled circulatory death donation may prevent ischemic cholangiopathy and improve graft survival. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:1745–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaurav R, Butler AJ, Kosmoliaptsis V, et al. Liver transplantation outcomes from controlled circulatory death donors: SCS vs in situ NRP vs ex situ NMP. Ann Surg. 2022;275:1156–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schurink IJ, de Goeij FHC, Habets LJM, et al. Salvage of declined extended-criteria DCD livers using in situ normothermic regional perfusion. Ann Surg. 2022;276:e223–e230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savier E, Lim C, Rayar M, et al. Favorable outcomes of liver transplantation from controlled circulatory death donors using normothermic regional perfusion compared to brain death donors. Transplantation. 2020;104:1943–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taner CB, Bulatao IG, Perry DK, et al. Asystole to cross-clamp period predicts development of biliary complications in liver transplantation using donation after cardiac death donors. Transpl Int. 2012;25:838–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coffey JC, Wanis KN, Monbaliu D, et al. The influence of functional warm ischemia time on DCD liver transplant recipients’ outcomes. Clin Transplant. 2017;31:e13068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mateo R, Cho Y, Singh G, et al. Risk factors for graft survival after liver transplantation from donation after cardiac death donors: an analysis of OPTN/UNOS data. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathur AK, Heimbach J, Steffick DE, et al. Donation after cardiac death liver transplantation: predictors of outcome. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:2512–2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan EY, Olson LC, Kisthard JA, et al. Ischemic cholangiopathy following liver transplantation from donation after cardiac death donors. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:604–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ho KJ, Owens CD, Johnson SR, et al. Donor postextubation hypotension and age correlate with outcome after donation after cardiac death transplantation. Transplantation. 2008;85:1588–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Croome KP, Barbas AS, Whitson B, et al. ; American Society of Transplant Surgeons Scientific Studies Committee. American Society of Transplant Surgeons recommendations on best practices in donation after circulatory death organ procurement. Am J Transplant. 2023;23:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunser MW, Takala J, Ulmer H, et al. Arterial blood pressure during early sepsis and outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1225–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kato R, Pinsky MR. Personalizing blood pressure management in septic shock. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van de Louw A, Cracco C, Cerf C, et al. Accuracy of pulse oximetry in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1606–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee DD, Joyce C, Duehren S, et al. Oxygen saturation during donor warm ischemia time and outcome of donation after circulatory death (DCD) liver transplantation with static cold storage: a review of 1114 cases. Liver Transpl. 2023;29:1192–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Rijn R, Schurink IJ, de Vries Y, et al. ; DHOPE-DCD Trial Investigators. Hypothermic machine perfusion in liver transplantation—a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1391–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Czigany Z, Pratschke J, Fronek J, et al. Hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion reduces early allograft injury and improves post-transplant outcomes in extended criteria donation liver transplantation from donation after brain death: results from a multicenter randomized controlled trial (HOPE ECD-DBD). Ann Surg. 2021;274:705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nasralla D, Coussios CC, Mergental H, et al. ; Consortium for Organ Preservation in Europe. A randomized trial of normothermic preservation in liver transplantation. Nature. 2018;557:50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mergental H, Laing RW, Kirkham AJ, et al. Transplantation of discarded livers following viability testing with normothermic machine perfusion. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hertl M, Howard TK, Lowell JA, et al. Changes in liver core temperature during preservation and rewarming in human and porcine liver allografts. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jochmans I, Fieuws S, Tieken I, et al. The impact of implantation time during liver transplantation on outcome: a Eurotransplant cohort study. Transplant Direct. 2018;4:e356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gauthier J, Wu QV, Gooley TA. Cubic splines to model relationships between continuous variables and outcomes: a guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:675–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suntharalingam C, Sharples L, Dudley C, et al. Time to cardiac death after withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment in potential organ donors. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2157–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walweel K, Boon AC, See Hoe LE, et al. Brain stem death induces pro-inflammatory cytokine production and cardiac dysfunction in sheep model. Biomed J. 2022;45:776–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schwarz P, Custodio G, Rheinheimer J, et al. Brain death-induced inflammatory activity is similar to sepsis-induced cytokine release. Cell Transplant. 2018;27:1417–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.National Health Service Blood and Transplant. Donation actions framework. Available at https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/27065/donation-actions-framework-v10-june-2022.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2024.

- 57.McLean KA, Camilleri-Brennan J, Knight SR, et al. Decision modeling in donation after circulatory death liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2017;23:594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.