Abstract

Background

Auranofin is an approved anti-rheumatic drug that has a broad-range inhibitory action against several microorganisms, including human pathogenic fungi. The auranofin activity against Histoplasma capsulatum, the dimorphic fungus that causes histoplasmosis, has not been properly addressed. Since there are few therapeutic options for this life-threatening systemic mycosis, this study evaluated the effects of auranofin on H. capsulatum growth and expression of virulence factors.

Methodology/principal findings

Minimal inhibitory and fungicidal concentrations (MIC and MFC, respectively) of auranofin against 15 H. capsulatum strains with distinct genetic backgrounds were determined using the yeast form of the fungus and a microdilution protocol. Auranofin activity was also assessed on a macrophage model of infection and on a Tenebrio molitor invertebrate animal model. Expression of virulence-related genes was compared between auranofin treated and untreated H. capsulatum yeast cells using a quantitative PCR assay. Auranofin affected the growth of different strains of H. capsulatum, with MIC and MFC values ranging from 1.25 to 5.0 μM and from 2.5 to >10 μM, respectively. Auranofin was able to kill intracellular H. capsulatum yeast cells and conferred protection against the fungus in the experimental animal model of infection. Moreover, the expression of catalase A, HSP70, superoxide dismutase, thioredoxin reductase, serine proteinase, cytochrome C peroxidase, histone 2B, formamidase, metallopeptidase, Y20 and YPS3 proteins were reduced after six hours of auranofin treatment. CONCLUSIONS/SIGNIFICANCE: Auranofin is fungicidal against H. capsulatum and reduces the expression of several virulence-related genes, which makes this anti-rheumatic drug a good candidate for new medicines against histoplasmosis.

Author summary

Histoplasmosis is a serious disease caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, which can be life-threatening and has limited treatment options. In this study, we investigated the potential of auranofin, a drug originally approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis, to combat H. capsulatum. We tested auranofin against different strains of the fungus and found that it effectively inhibited fungal growth. This drug was also effective in killing the fungus within cells from the immune system and provided protection in an experimental animal model. Furthermore, auranofin reduced the expression of several genes associated with the fungus’s ability to cause disease. These genes are involved in critical functions such as detoxifying harmful substances and maintaining cellular structures. By suppressing these genes, auranofin hampers the fungus’s ability to survive and cause infection. These findings suggest that auranofin could be repurposed as a treatment for histoplasmosis, offering a new avenue for therapy against this challenging infection. This research is significant because it highlights the potential of existing drugs to treat other diseases, broadening our arsenal of available treatments and contributing to better healthcare solutions.

1 Introduction

Auranofin is a gold-containing orally administered approved drug used for more than 40 years to treat rheumatoid arthritis. However, since the introduction of biological therapies for this disease, such as the chimeric monoclonal antibody infliximab, the original use of auranofin has remarkedly decreased. Due to the auranofin safety, guaranteed by its four decades of use with low contraindications, this drug became an interesting target for drug repurposing [1]. In fact, studies, in different stages of clinical research, are in development to repurpose auranofin to several diseases, infectious or not [2–4].

Several studies have demonstrated the broad-range antimicrobial activity of auranofin against several bacteria [5], protozoa [3,6], viruses [7] and fungi [8]. The list of auranofin-susceptible fungi includes certain Candida species, Cryptococcus neoformans, Blastomyces dermatitidis, Aspergillus fumigatus, Paecylomyces variotii, Scedosporium apiospermum, Lomentospora prolificans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and several chromoblastomycosis agents such as Fonsecaea pedrosoi and Cladophialophora carrionii [8–10]. Despite the great auranofin antifungal properties, its activity against some important human pathogenic fungi remains unelucidated.

Histoplasma capsulatum is the etiological agent of histoplasmosis, a systemic mycosis that is often related to outbreaks, usually reported in caves, mines, chicken coops and abandoned places [11]. This mycosis can affect immunocompetent people, usually as a chronic pulmonary disease [12], and immunosuppressed patients, especially people living with HIV/AIDS, who develop a life-threatening disseminated disease [13]. The infection starts with the inhalation of mycelial propagules, especially microconidia, which convert to the yeast form inside or outside phagocytes present in the lungs. These phagocytes may be vehicles for fungal dissemination into the host, since the H. capsulatum yeast form is highly adapted to mammalian hosts [14]. Histoplasmosis is a prevalent opportunistic infection among people living with HIV in the Latin America region, as indicated by various studies [15–17].

A proper management of histoplasmosis depends on rapid diagnosis and specific treatment [18]. Currently, liposomal amphotericin B is the first-choice induction therapy for disseminated and moderate-to-severe histoplasmosis, followed by a consolidation regimen using itraconazole. Itraconazole alone is also the alternative for mild infections [19]. These two antifungal drugs present a series of adverse effects and drug interactions [20,21], which is a serious problem in critically ill immunosuppressed patients who receive several medications.

The antifungal pipeline includes three potential new antifungal drugs with antifungal activity against H. capsulatum: fosmanogepix, a drug that affects trafficking and anchoring mannoproteins to the fungal cell membrane and wall; ibrexafungerp, a triterpenoid that inhibits glucan synthase; and olorofim, an orotomide that targets pyrimidine synthesis. However, none of them have undergone specific clinical trials for histoplasmosis [22]. In this scenario, drug repurposing is an interesting alternative, since drugs with proven administration safety may skip some stages of clinical research [23]. As auranofin administration is safe [1] and it demonstrated antifungal activity against many fungi [24], we studied whether this anti-rheumatic drug can affect H. capsulatum growth and expression of genes that enhance fungal virulence during infection.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Strains

The reference strain H. capsulatum G217B (ATCC 26032) was used throughout the study. In addition, other 14 H. capsulatum strains, with different genotypes determined by MLST analyses in previous publications [25–28], were included in the in vitro antifungal susceptibility studies. All strains are maintained at the Pathogenic Fungal Collection of Fiocruz (WDCM 951). Fungal strains were maintained in the yeast-like form on ML-Gema agar medium [29] at 37°C.

2.2 In vitro antifungal tests

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of auranofin against the H. capsulatum strains was verified through the broth microdilution method according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guideline [30], with a few modifications to test this dimorphic fungus and the antirheumatic drug, which are described herein: two-fold serial dilutions of a stock auranofin solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (2 mM) were made to obtain the final testing concentrations (range: 10 to 0.02 μM) in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), supplemented with 2% glucose (Neon Química, Susano, Brazil) and buffered (pH 7.2) with 3-N-morpholinopropanesulfonic acid (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Fungal suspensions (1 × 106 yeast-like cells/mL) were prepared in sterile 0.9% saline solution after five days of growth. Fungal suspensions were then added to the wells of a flat-bottom 96-well plate (Corning, Glendale, AZ, USA) containing the different auranofin concentrations. For each strain, a drug-free and a cell-free control wells were included, as positive and negative growth controls, respectively. Plates were incubated at 35°C for five days. The MIC was determined as the lowest auranofin concentration that completely inhibited fungal growth (100% inhibition), as the EUCAST method suggest for amphotericin B. Additionally, to determine the minimal fungicidal concentration (MFC) as previously published for auranofin and fungal cells [9], 5 μL from each well without visual fungal growth from the plates used for MIC determinations and incubated at 37°C were plated on potato dextrose agar (Beckton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA) and incubated for 21 days at 25°C. The lowest auranofin concentration without H. capsulatum growth after this incubation was defined as the MFC. Interpretations whether auranofin is fungicidal or fungistatic was as follows: if the MFC/MIC ratio was 1 or 2, it was considered fungicidal, otherwise, it was classified as fungistatic [31]. MIC and MFC determinations were performed in triplicate.

2.3 Synergism studies

The synergistic activity of auranofin with conventional antifungal agents was verified using the checkerboard method [32]. In this method, two drugs were loaded into a single 96-well plate, with varying concentrations of the auranofin-antifungal combination in each well. Initially, this experiment was conducted using the G217B reference strain to evaluate the synergistic effects of the combinations between auranofin and the antifungal drugs amphotericin B, itraconazole, and caspofungin (all from Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Subsequently, the experiment was replicated for the drug combinations that presented synergism using representative strains from different H. capsulatum phylogenetic species. The auranofin and antifungal dilutions were prepared following the methodology proposed by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), starting from a 100-fold concentrated stock auranofin and antifungal solution [30]. The final concentrations of the auranofin and antifungal drug ranged from 0.156 to 10 μM and 0.0004 to 2 μM, respectively. The fungal inoculum and incubation conditions remained the same as those described for the in vitro antifungal tests. The interaction between the drugs was classified using the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) [33]. The types of interactions between the drug combinations were classified as synergism if FICI ≤ 0.5, indifference if 0.5 < FICI < 4, and antagonism if FICI ≥ 4 [32,33].

2.4 Morphology studies

The H. capsulatum G217B yeast-like cells were treated with a subinhibitory auranofin concentration (1/2 MIC) in HAM’s F12 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and incubated at 37°C for three days. A control culture without auranofin was made under the same conditions. Cells were harvested, washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and visualized with an AXIO Lab.A1 bright-field light microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The diameter of 100 cells of each condition was measured using the ImageJ 1.40 g software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Three replicates were performed for each condition.

2.5 Regulation of gene expression

We treated H. capsulatum G217B yeast-like cells (1 × 106 cells/mL) with a subinhibitory concentration (1/2 MIC) of auranofin in HAM’s F12 medium for three and six hours. The cells were harvested and subjected to total RNA extraction by mechanical cell rupture using a BeadBeater (BioSpec, Bartlesville, OK, United States), 0.5 μm diameter glass beads and TRIzol (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Equal amounts of RNA (1 μg) of the RNAs were used to synthesize single stranded cDNAs (DNA complementary) using the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and oligo (dT) primer. Prior to PCR reactions, the cDNAs were diluted (1:5) by adding water. Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using the SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States), in the AriaMx real-time PCR system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), with 10 pmol of each specific primer and 4 μL of template cDNA in a final volume of 20 μl. The genes encoding the virulence-related proteins catalase A (HCAG_05109), catalase B (HCAG_08064), heat shock protein (HSP) 70 (HCAG_01398), superoxide dismutase (HCAG_01543), thioredoxin reductase (HCAG_07019), serine proteinase (HCAG_00635), cytochrome C peroxidase (HCAG_08658), Histone 2B (HCAG_03525), formamidase (HCAG_08831), metallopeptidase (HCAG_04252), Y20 protein (HCAG_04745), and yeast phase specific protein 3 (YPS 3) (Q00950) were selected for analysis. The constitutively expressed glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (HCAG_04910) gene [34–36] was selected to normalize the samples. Intron spanning primers were designed using the Primer 3 tool and are listed at the S1 Table. A cDNA aliquot from each sample diluted serially at 1:5 was mixed and used to generate a relative standard curve. All analyses were performed in triplicate. The relative expression levels of selected genes were obtained using the standard curve method for relative quantification [37]. Transcription levels of cells treated with auranofin were normalized in relation to transcription levels of the untreated control condition.

2.6 Intracellular antifungal activity

The intracellular activity of auranofin on the H. capsulatum reference strain was determined by counting colony-forming units (CFUs) recovered from macrophage infection. J774 1.6 macrophages (Rio de Janeiro Cell Bank–BCRJ/UFRJ, accession number 0273) were employed. Macrophages (less than 10 passages) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum and MEM non-essential amino acid solution (Sigma Aldrich), at 37°C in a CO2 incubator (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) until the cells were confluent. A total of 106 J774 macrophages were plated per well of a 96-well plate in RPMI medium containing IFN-γ (1 U/mL) (Sigma Aldrich) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. In parallel, H. capsulatum yeast cells were grown in HAM’s F12 medium for 72 h. Next, 5 × 106 yeast-like cells were added per well, to give a yeast:macrophage cell ratio of 5:1. After two hours of yeast/macrophage interaction, non-phagocytosed/non-adhered yeast-like cells were removed after three washes with PBS [38]. In addition, auranofin was added to the wells at the following concentrations: ¼ MIC, MIC, and 4× MIC. Controls consisted in: (i) culture medium only (sterility control); (ii) macrophages only (macrophage control); (iii) H. capsulatum yeast-like cells only (planktonic control); and (iv) H. capsulatum yeast-like cells with macrophages (5:1 ratio) without auranofin (intracellular control). Cultures were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. After this incubation, macrophages were lysed with cold water and fungal cells were recovered. The number of viable H. capsulatum cells was determined based on CFUs counting. The lysates were cultured in ML-Gema agar medium and CFUs were determined after growth at 37°C for 10 days. Four technical replicates were performed for three biological replicates.

2.7 Invertebrate model for in vivo activity

For in vivo activity studies, we adapted a previously published invertebrate model [39], using Tenebrio molitor larvae of at least 1 cm, with regular motility, without dark spots or gray marks. Ten animals were inoculated in the last left proleg with 1 × 104 H. capsulatum yeast-like cells. Animals were treated with an injection of 10 μL of a 5.7 mg/kg auranofin solution, two and 24 hours after fungal injection (auranofin group). Other animal groups consisted in: (i) non-injected larvae (sham group); (ii) traumatized with the syringe (trauma group); (iii) injected with sterile PBS (non-infected group); (iv) infected with H. capsulatum and treated with PBS (infected group); (v) infected with H. capsulatum and treated with itraconazole (Sigma-Aldrich) at the same doses and times (itraconazole group); and (vi) injected with PBS, instead of H. capsulatum cells and treated with auranofin (auranofin control group). Drug concentrations in the experiments were based a safe itraconazole dose to treat Galleria mellonella larvae, previously described [40]. Then, the animals were kept in Petri dishes at room temperature and were fed ad libitum on bran flour. Mortality and phenotypic changes were recorded for 14 days. Larvae that convert to pupa were censored. This experiment was performed in three biological replicates.

2.8 Statistical analyses

The Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for data analyses. The normality of the data was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test to decide between parametric or non-parametric tests. The comparison of cellular diameter was performed using the Student´s t test. qPCR data was evaluated using the Student’s t test. Intracellular antifungal activity was evaluated with the Wilcoxon test. Survival curves were compared using the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. A 0.05 significance level was adopted for all analyses.

3 Results

3.1 Auranofin has anti-Histoplasma activity

Table 1 presents MIC and MFC data for the in vitro auranofin susceptibility test of the 15 H. capsulatum strains. Median MIC value (MIC50) was 2.5 μM, while the MIC90 was 5 μM (range: 1.25–5.0 μM / geometric mean: 2.74 μM). Median MFC was 5.0 μM (range: 2.5->10 μM). MFC:MIC ratio was equal or lower than two for nine strains (60%), indicating that auranofin was fungicidal against some H. capsulatum strains located into different genetic clades.

Table 1. Antifungal susceptibility data of auranofin against 15 Histoplasma capsulatum strains from distinct genetic clades.

| Strain | Genetic clade | Auranofin MIC a (μM / μg/mL) | Auranofin MFC b (μM) | MFC/MIC ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G217B | NAm2 | 1.25 / 0.84 | 10 / 6.72 | 8 |

| G184A | Panama | 5 / 3.36 | 5 / 3.36 | 1 |

| 39942 | Panama | 1.25 / 0.84 | 5 / 3.36 | 4 |

| CÃO 4 | RJ | 5 / 3.36 | 10 / 6.72 | 2 |

| IGS 4/5 | RJ | 5 /3.36 | 5 / 3.36 | 1 |

| TI01 | RJ | 5 / 3.36 | >10 / >6.72 | >2 |

| 39439 | RJ | 1.25 / 0.84 | 2.5 / 1.68 | 2 |

| IPEC 24_11 | RJ | 5 / 3.36 | 10 / 6.72 | 2 |

| IPEC 28_11 | RJ | 2.5 / 1.68 | >10 / >6.72 | >4 |

| CE 25/14 | Northeast BR1 | 1.25 / 0.84 | 10 / 6.72 | 4 |

| INI 02/16 | LAmB1 | 5 /3.36 | 10 / 6.72 | 2 |

| IPEC 11_12 | LAmB1 | 2.5 1.68 | 5 / 3.36 | 2 |

| EH394H | LamA1 | 5 / 3.36 | 5 / 3.36 | 1 |

| EH53 | LAmA | 1.25 / 0.84 | 5 /3.36 | 4 |

| 20231 | Unknown1 | 2.5 / 1.68 | 5 / 3.36 | 2 |

a MIC: Minimal inhibitory concentration

b MFC: Minimal fungicidal concentration

3.2 Auranofin presents synergism with amphotericin B against H. capsulatum

The initial checkerboard experiment conducted using the H. capsulatum G217B reference strain revealed indifferent interactions between auranofin and itraconazole or caspofungin (FICI values of 0.548 and 2.0, respectively). Conversely, the interaction between auranofin and amphotericin B exhibited synergy for this strain (FICI = 0.176). Subsequently, we performed checkerboard assays with auranofin and amphotericin B on five additional strains from distinct genotypes. Table 2 describes the checkerboard results of auranofin and amphotericin B for these six strains. Notably, this interaction demonstrated synergy in five strains and indifference in one.

Table 2. Checkerboard assay data of auranofin and amphotericin B against Histoplasma capsulatum strains from distinct genetic clades.

| Strain | Genetic clade | MIC a (μM) | FICI d | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUR b | AMB c | AUR/AMB | ||||

| G217B | Nam2 | 1.25 | 0.125 | 0.156/0.008 | 0.1875 | Synergism |

| G184A | Panama | 5 | 0.03 | 0.625/0.008 | 0.375 | Synergism |

| IGS 4/5 | RJ | 5 | 0.062 | 0.312/0.015 | 0.3125 | Synergism |

| CE 25/14 | Northeast BR1 | 2.5 | 0.03 | 0.312/0.008 | 0.375 | Synergism |

| IPEC 11_12 | LAmB | 5 | 0.03 | 0.312/0.008 | 0.3125 | Synergism |

| EH394H | LAmA1 | 5 | 0.015 | 5/0.008 | 1.5 | Indifference |

a MIC: Minimal inhibitory concentration

b AUR: Auranofin

c AMB: Amphotericin B

d FICI: fractional inhibitory concentration index

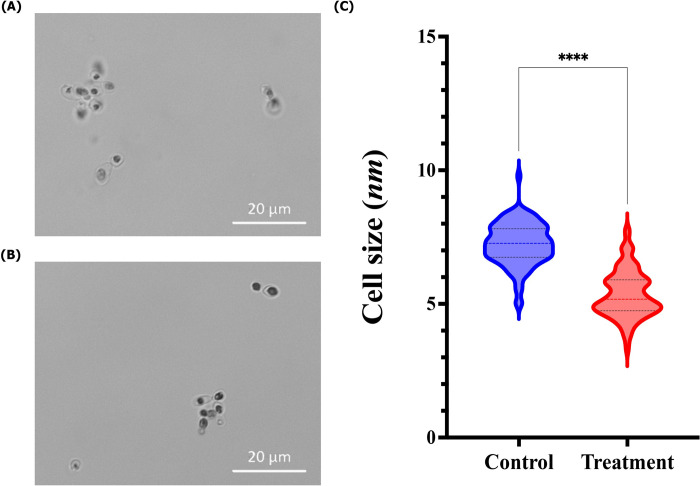

3.3 Auranofin changes H. capsulatum cellular size

Both auranofin-treated (Fig 1A) and -untreated (Fig 1B) H. capsulatum yeast cells presented a similar spherical to ovoid format. However, the diameter of H. capsulatum yeast cells treated with a subinhibitory concentration of auranofin showed a lower size when compared to the untreated control (P < 0.05, Fig 1C).

Fig 1. Influence of auranofin in the morphology of Histoplasma capsulatum G217B reference strain.

(A) H. capsulatum yeast cells after 72 h incubation at 37°C in Ham´s F-12 drug-free medium; (B) H. capsulatum yeast cells after treatment with auranofin (0.625 μM) (Bars: 20 μm); (C) Comparison of the diameter size of H. capsulatum yeast cells, treated or not with auranofin. Optical microscopy images are representative of three independent experiments. The color line inside the violins represent the median diameter size and the black lines the interquartile ranges of 100 measurements performed in triplicate. **** P < 0.0001, Student´s t test.

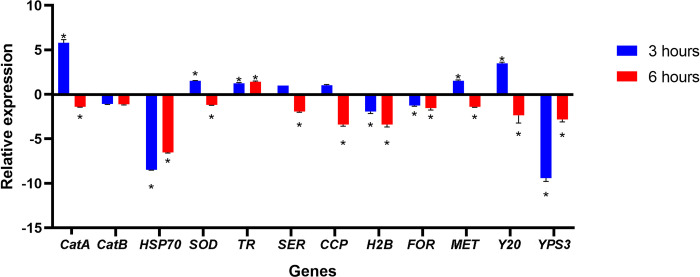

3.4 Auranofin regulates the expression of virulence-related genes

PCR efficiencies ranged between 90% and 110% for each of the primer pairs, indicating that all real time assays had similar good efficiencies, confirming the validation of the primers and the precision of experiments. These data are presented in S1 Table. Fig 2 presents the transcriptional levels of 12 genes related to fungal virulence. In general, the transcripts expression levels, except for catalase B, were significant altered in at least one of the two time points evaluated. After three hours of auranofin interaction, the genes coding for HSP70, serine proteinase, histone 2B, formamidase, and YPS3 were down-regulated, while the genes encoding catalase A, superoxide dismutase, thioredoxin reductase, metallopeptidase, and Y20 protein were up-regulated. On the other hand, after six hours of auranofin exposure, the gene encoding thioredoxin reductase was up-regulated, while all other genes, except for the catalase B gene, which was not affected by auranofin, were down-regulated.

Fig 2. Influence of auranofin in the expression of some virulence-related genes by the Histoplasma capsulatum G217B reference strain.

Results are presented as the mean and standard deviations derived from three independent experiments. The mean and standard deviations of the relative expression levels of each gene following three (blue bars) or six (red bars) hours of exposure to auranofin (0.625 μM) are illustrated. CatA: catalase A; CatB: catalase B; HSP70: heat shock protein 70 kDa; SOD: superoxide dismutase; TR: thioredoxin reductase; SER: serine proteinase; CCP: cytochrome C peroxidase; H2B: histone 2B; FOR: formamidase; MET: metallopeptidase; Y20: Y20 protein; YPS3: yeast phase specific protein 3. * P < 0.05, Student´s t test.

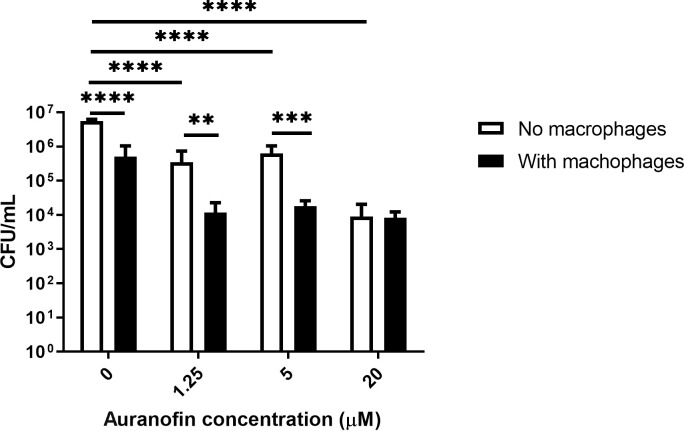

3.5 Auranofin is effective against intracellular H. capsulatum yeast cells

Fig 3 presents the intracellular anti-Histoplasma activity of auranofin using a macrophage model. A reduced intracellular H. capsulatum CFU counts was observed as compared to the planktonic control, that is, same culture medium, but no macrophages (P < 0.0001). Auranofin at subinhibitory (1.25 μM / 0.84 μg/mL) and inhibitory concentrations (5 μM / 3.36 μg/mL) reduced H. capsulatum CFU counts as compared with the planktonic (P < 0.0001) and intracellular controls, without auranofin supplementation (P < 0.05). Moreover, intracellular H. capsulatum CFU counts were lower than planktonic H. capsulatum in the presence of subinhibitory and inhibitory auranofin concentrations (P < 0.05). High auranofin concentration (20 μM / 13.4 μg/mL) also reduced H. capsulatum CFU counts compared to the planktonic (P < 0.0001) and intracellular control (P < 0.05), but CFU counts of intracellular and planktonic H. capsulatum cells at this drug concentration were similar (P = 0.7077).

Fig 3. Antifungal activity of auranofin against intracellular H. capsulatum G217B reference strain. Results are presented as the mean and standard deviations derived from three independent experiments.

The mean and standard deviations of the colony count units per milliliter (CFU/mL) of H. capsulatum planktonic (white bars) and intracellular (black bars) yeast cells after treatment with different auranofin concentrations (0, 0.125, 5, and 20 μM) are illustrated. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon test.

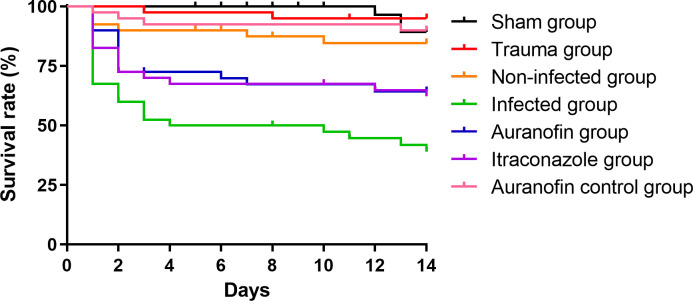

3.6 Auranofin is effective in an experimental model of H. capsulatum infection

Fig 4 presents the survival curves of T. molitor larvae challenged with the reference H. capsulatum G217B strain. As expected, the sham, trauma, and non-infected groups presented more than 80% survival at the end of the experiment, as well as the auranofin control group that presented similar survival to the other control groups (P = 0.4265). Non-treated infected larvae presented 80% deaths, with a median survival of seven days. Animals treated with both itraconazole and auranofin were significantly protected, as compared to the infected group (P = 0.0407 and 0.0227, respectively). Moreover, survival curves of animals treated with itraconazole and auranofin did not present significant differences (P = 0.7969).

Fig 4. Antifungal activity of auranofin in the Tenebrio molitor infection model.

Survival curves illustrate larvae infected with Histoplasma capsulatum G217B and treated with auranofin or itraconazole (5.7 mg/kg), represented by the blue and purple lines, respectively. Controls consisted in non-injected larvae (sham group, black line); larvae traumatized with the syringe (trauma group, red line); larvae injected with sterile PBS (non-infected group, orange line); infected with H. capsulatum and inoculated with PBS instead of auranofin or itraconazole (infected group, green line); and injected with PBS, instead of H. capsulatum cells and treated with auranofin 5.7 mg/kg (auranofin control group, pink line). Each curve represents a group of 30 larvae, monitored daily for survival for up to 14 days after infection. Larvae that converted to pupa were censored.

4 Discussion

Currently, drug repurposing is a promising subject into the drug discovery field, as it identifies new therapeutic opportunities for old drugs, already approved to treat another disease [41]. This strategy has gained importance to discover new drugs for neglected, rare or emerging diseases [42]. One of the strategies described to advance into the treatment of disseminated histoplasmosis is the drug repurposing approach, which would benefit individuals with histoplasmosis and other comorbidities [43]. Here, we present auranofin as a good candidate for the treatment of this life-threatening systemic mycosis. Besides anti-Histoplasma activity, this anti-rheumatic drug is also effective against other diseases that can occur in patients with histoplasmosis, such as neurotoxoplasmosis [3], drug-resistant bacterial infections [44], several types of cancer [45], candidiasis, and cryptococcosis [46], which improves the attractiveness towards auranofin repurposing.

The first evidence for the auranofin repurposing potential for histoplasmosis was its good in vitro activity against H. capsulatum strains of different genetic genotypes, such as NAm2, LAmA, LAmB1, Panama, RJ, Northeast BR1, and Unknown1. The MIC herein described, 1.25 to 5 μM (0.85 to 3.4 μg/mL), are similar to those found for other fungi. For instance, auranofin MICs against Scedosporium spp. ranged from 1 to 8 μg/mL [47], against black fungi that cause chromoblastomycosis from 1.25 to 2.5 μM [9], against Candida spp. from 0.25 to >16 μg/mL, and from 1 to 2 μg/mL against both Cryptococcus neoformans and Blastomyces dermatitidis [8]. Moreover, it has been described that auranofin at 32 μg/mL reduces the viability rate of mammalian cells by no more than 50%, indicating that auranofin toxicity is higher for H. capsulatum [48]. In addition to its isolated anti-Histoplasma activity, auranofin also demonstrated in vitro synergism with amphotericin B, a medication commonly employed in the treatment of histoplasmosis, among the majority of strains tested. This observation indicates a promising prospect for future therapeutic interventions against this mycosis. It is important to emphasize that the low bioabsorption of auranofin, estimated to be around 25% [45], underscores the need for adjustments in the formulation of this drug to effectively translate the results of this study in clinical practice.

Good candidates for drug repurposing against mycotic diseases should have a fungicidal, rather than a fungistatic nature [49]. In the present study, auranofin was fungicidal against 53.8% of the H. capsulatum strains tested, which is another advantage of this drug in the context of histoplasmosis treatment. Auranofin has also showed a fungicidal profile against Phialophora verrucosa and Exophiala dermatitidis [9].

Treatment of fungal cells with repurposed drugs may induce modifications in their cellular morphology [50]. For this reason, we investigated whether auranofin may induce this phenotypic change and it was observed that despite retaining the original shape, auranofin-treated cells were significantly smaller. This result was intriguing, as previous studies have described an alternative mechanism of action for auranofin in fungal cells involving the Mia40–Erv1 pathway. According to this model, auranofin induces a metabolic shift from respiration to fermentation without disrupting membrane potential or mitochondrial function [45]. However, yeast cells undergoing fermentation are typically larger than those undergoing respiration [51], This observation suggests that either the Mia40–Erv1 pathway is not involved in auranofin’s mechanism of action in H. capsulatum, or the relationship between cell size and metabolic state (fermentation versus respiration) in H. capsulatum differs from that observed in S. cerevisiae.

Cellular size is connected with virulence in some fungal species. For instance, smaller cells of C. neoformans, Mucor circinelloides, and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis are more likely to be phagocytosed and killed by macrophages [52–54]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies linking H. capsulatum virulence with its cellular size, but it is possible that a similar behavior occurs with this dimorphic fungus, thus auranofin may contribute to reduce H. capsulatum virulence. In our in vitro model of macrophage / H. capsulatum interaction, auranofin at inhibitory and subinhibitory concentrations enhanced macrophage killing of fungal yeast-like cells. This may have occurred by a direct action of auranofin in intracellular H. capsulatum cells or indirectly, by a reduction of yeast size, facilitating macrophage killing.

In fact, there are some studies reporting virulence reduction when pathogenic fungi are treated with compounds presenting antifungal activity [55–57]. To evaluate this issue, it was performed a qPCR assay targeting some genes associated with virulence in H. capsulatum or other fungal models. Two catalases were evaluated and only catalase A presented gene expression alterations in response to auranofin treatment. This is similar to what happens with transcript levels of this gene in response to cell morphology or oxidative stress [58]. Several genes related to the oxidative stress were down-regulated, especially after six hours of drug interaction. However, the thioredoxin reductase gene was the sole evaluated gene up-regulated on the two time points herein studied. In human cells, auranofin is a strong thioredoxin reductase enzymatic inhibitor [7]. The results of the current study do not allow us to conclude whether the same mechanism of action occurs in H. capsulatum. However, if this is indeed the case, the overexpression of this gene is likely a compensatory mechanism necessary because the existing enzymes are rendered non-functional as a result of auranofin action. In addition, the early up-regulation of catalase A, superoxide dismutase, and thioredoxin reductase suggests an oxidative stress mode of action of auranofin. Another interesting and strongly down-regulated gene was YPS3. This protein is located in cell surface and produced only by the pathogenic yeast-like form of the fungus, probably associated with fungal dissemination to some host organs, especially liver and spleen [59]. This is another encouraging result that drives the repurposing study of auranofin to treat histoplasmosis.[46]. A similar mechanism may occur in H. capsulatum yeast cells, which remains to be elucidated.

Finally, we used an invertebrate model to test the in vivo activity of auranofin. In last years, these animal models have gained importance in several science fields as a response to the public concern about the use of mammalian animals in research studies, with good success in several areas of biology and medicine [60]. However, some limitations of their use in drug discovery are the differences among invertebrate and human proteins, the absence of an adaptive immune response, and the lack of drug metabolism in insects [61]. In this study, auranofin showed to be as protective as itraconazole in the T. molitor larvae model. This model has gained relevance in medical mycology, including the antifungal study field, because this insect, which is susceptible to a broad range of pathogenic fungi, has a complex innate immunity, comprising cellular and humoral components [62]. Again, the auranofin activity in this experiment may be a direct result of the antifungal action of auranofin on H. capsulatum cells or an indirect result of the reduction of H. capsulatum virulence arsenal. Quantifying fungal CFU in infected animals would help clarify this issue. However, H. capsulatum is a slow-growing fungus, and recovering CFU of this species from larvae is extremely challenging due to the presence of contaminant fungi in the larvae microbiota, which grow faster than H. capsulatum. Future studies with mammalian hosts should address these hypotheses.

The repositioning of auranofin as an anti-Histoplasma drug holds significant relevance for public health. Originally developed as a gold compound for rheumatoid arthritis, auranofin emerges as a promising candidate for treating histoplasmosis, a fungal infection that can be life-threatening, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. Its potential repurposing offers a cost-effective and readily available therapeutic option, which is crucial given the high costs and limited accessibility of current antifungal treatments. By providing a viable alternative, auranofin could enhance treatment accessibility, reduce healthcare burdens, and improve patient outcomes in regions where histoplasmosis is prevalent, ultimately contributing to a more effective management of this serious infectious disease.

In addition to the limitations related to the animal model used for the in vivo study discussed above, there are other weaknesses in the current work: (i) we were unable to include H. capsulatum strains representing all known genotypes; (ii) there may be other genes with differential expression after auranofin treatment that were not evaluated in this study; and (iii) for most strains, the auranofin MIC was higher than the maximum plasma gold concentration following a daily administration of 6 mg of auranofin for one week, which is 1.584 μM [1]. This indicates that some modifications to this medication are necessary to adapt it for use in histoplasmosis patients.

In conclusion, auranofin seems to be a promising candidate for a repurposed drug to treat histoplasmosis, due to its fungicidal nature against most H. capsulatum strains and its potential to reduce H. capsulatum virulence.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Dr. Maria Lucia Taylor, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, for kindly providing two H. capsulatum strains used in this study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are deposited in BioStudies, accession number S-BSST1660, and can be found at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/studies/S-BSST1660 or under the DOI 10.6019/S-BSST1660. These data were used to generate the results presented within the manuscript and/or its supplementary file.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by a grant from an international Tripartite Fiocruz/USP/Pasteur initiative to R.A.-P., C.P.T., and A.A. The study has also received financial support from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), grant number 403627/2023-0 and Programa Jovens Pesquisadores (INI/Fiocruz), grant number INI-003-FIO-19-2-7 (both to R.A.-P.). R.M.Z-O is supported in part by CNPq, grant number 308315/2021-9 and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), grant number E-26/200.381/2023. R.A.-P. is supported in part by CNPq, grant number 307171/2023-0, and FAPERJ, grant number E-26/201.441/2021. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Yamashita M. Auranofin: Past to Present, and repurposing. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;101: 108272. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harbut MB, Vilchèze C, Luo X, Hensler ME, Guo H, Yang B, et al. Auranofin exerts broad-spectrum bactericidal activities by targeting thiol-redox homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112: 4453–4458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504022112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abou-El-Naga IF, Mogahed NMFH. Repurposing auranofin for treatment of Experimental Cerebral Toxoplasmosis. Acta Parasitol. 2021;66: 827–836. doi: 10.1007/s11686-021-00337-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdalbari FH, Telleria CM. The gold complex auranofin: new perspectives for cancer therapy. Discov Oncol. 2021;12: 42. doi: 10.1007/s12672-021-00439-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma N, Singh A, Sharma R, Kumar A. Repurposing of Auranofin Against Bacterial Infections: An In silico and In vitro Study. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2021;17: 687–701. doi: 10.2174/1386207323666200717155640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng L, Pomel S, Latre de Late P, Taravaud A, Loiseau PM, Maes L, et al. Repurposing Auranofin and Evaluation of a New Gold(I) Compound for the Search of Treatment of Human and Cattle Parasitic Diseases: From Protozoa to Helminth Infections. Molecules. 2020;25: E5075. doi: 10.3390/molecules25215075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonzogni-Desautels K, Ndao M. Will Auranofin Become a Golden New Treatment Against COVID-19? Front Immunol. 2021;12: 683694. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.683694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF, Srinivasan A, Chaturvedi AK, Fothergill AW, Wormley FL, et al. Repurposing auranofin as an antifungal: In vitro activity against a variety of medically important fungi. Virulence. 2017;8: 138–142. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1196301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coelho RA, Joffe LS, Alves GM, Figueiredo-Carvalho MHG, Brito-Santos F, Amaral ACF, et al. A screening of the MMV Pathogen Box® reveals new potential antifungal drugs against the etiologic agents of chromoblastomycosis. PLoS One. 2020;15: e0229630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gamberi T, Fiaschi T, Modesti A, Massai L, Messori L, Balzi M, et al. Evidence that the antiproliferative effects of auranofin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae arise from inhibition of mitochondrial respiration. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;65: 61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerra BT, Almeida-Silva F, Almeida-Paes R, Basso RP, Bernardes JPRA, Almeida MA, et al. Histoplasmosis Outbreaks in Brazil: Lessons to Learn About Preventing Exposure. Mycopathologia. 2020;185: 881–892. doi: 10.1007/s11046-019-00389-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capone D, Wanke B, Monteiro PC, Lazéra MS, de Noronha Andrade G, do Valle AC, et al. Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mycopathologia. 1999;145: 75–79. doi: 10.1023/a:1007016414833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nacher M, Valdes A, Adenis A, Blaizot R, Abboud P, Demar M, et al. Disseminated Histoplasmosis in HIV-Infected Patients: A Description of 34 Years of Clinical and Therapeutic Practice. J Fungi (Basel). 2020;6: E164. doi: 10.3390/jof6030164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mittal J, Ponce MG, Gendlina I, Nosanchuk JD. Histoplasma capsulatum: Mechanisms for Pathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2019;422: 157–191. doi: 10.1007/82_2018_114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nacher M, Couppié P, Epelboin L, Djossou F, Demar M, Adenis A. Disseminated Histoplasmosis: Fighting a neglected killer of patients with advanced HIV disease in Latin America. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16: e1008449. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nacher M, Leitao TS, Gómez BL, Couppié P, Adenis A, Damasceno L, et al. The Fight against HIV-Associated Disseminated Histoplasmosis in the Americas: Unfolding the Different Stories of Four Centers. J Fungi. 2019;5: 51. doi: 10.3390/jof5020051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajasingham R, Medina N, Mousquer GT, Caceres DH, Jordan A, Nacher M, et al. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of routine histoplasmosis screening among people living with advanced HIV disease in Latin America and the Caribbean. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3: e0001861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0001861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Beigelman-Aubry C, Lamoth F, Dunet V, Slavin M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of invasive fungal infections: looking ahead. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74: ii27–ii37. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson GR, Le T, Chindamporn A, Kauffman CA, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Ampel NM, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of the endemic mycoses: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21: e364–e374. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00191-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suberviola B. Seguridad clínica de la anfotericina B liposomal. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2021;38: 56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2021.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of adverse events with systemic onychomycosis medications reported to the United States Food and Drug Administration. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32: 783–787. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1708242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoenigl M, Sprute R, Egger M, Arastehfar A, Cornely OA, Krause R, et al. The Antifungal Pipeline: Fosmanogepix, Ibrexafungerp, Olorofim, Opelconazole, and Rezafungin. Drugs. 2021;81: 1703–1729. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01611-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittal N, Mittal R. Repurposing old molecules for new indications: Defining pillars of success from lessons in the past. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2021;912: 174569. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almeida-Paes R, Frases S. Repurposing drugs for fungal infections: advantages and limitations. Future Microbiol. 2023;18: 1013–1016. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2023-0108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasuga T, White TJ, Koenig G, McEwen J, Restrepo A, Castañeda E, et al. Phylogeography of the fungal pathogen Histoplasma capsulatum. Mol Ecol. 2003;12: 3383–3401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vite-Garín T, Estrada-Bárcenas DA, Cifuentes J, Taylor ML. The importance of molecular analyses for understanding the genetic diversity of Histoplasma capsulatum: an overview. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2014;31: 11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2013.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damasceno LS, Teixeira M de M, Barker BM, Almeida MA, Muniz M de M, Pizzini CV, et al. Novel clinical and dual infection by Histoplasma capsulatum genotypes in HIV patients from Northeastern, Brazil. Sci Rep. 2019;9: 11789. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48111-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almeida-Silva F, de Melo Teixeira M, Matute DR, de Faria Ferreira M, Barker BM, Almeida-Paes R, et al. Genomic Diversity Analysis Reveals a Strong Population Structure in Histoplasma capsulatum LAmA (Histoplasma suramericanum). J Fungi. 2021;7: 865. doi: 10.3390/jof7100865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fressatti R, Dias-Siqueira VL, Svidzinski TIE, Herrero F, Kemmelmeier C. A medium for inducing conversion of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum into its yeast-like form. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87: 53–58. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761992000100010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.EUCAST. EUCAST definitive document EDef 7.1: method for the determination of broth dilution MICs of antifungal agents for fermentative yeasts. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14: 398–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franconi I, Lupetti A. In Vitro Susceptibility Tests in the Context of Antifungal Resistance: Beyond Minimum Inhibitory Concentration in Candida spp. J Fungi. 2023;9: 1188. doi: 10.3390/jof9121188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dannaoui E, Afeltra J, Meis JFGM, Verweij PE, Eurofung Network. In vitro susceptibilities of zygomycetes to combinations of antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46: 2708–2711. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.8.2708-2711.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odds FC. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52: 1. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almeida MA, Baeza LC, Almeida-Paes R, Bailão AM, Borges CL, Guimarães AJ, et al. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Histoplasma capsulatum Yeast and Mycelium Reveals Differential Metabolic Shifts and Cell Wall Remodeling Processes in the Different Morphotypes. Front Microbiol. 2021;12: 640931. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.640931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edwards JA, Chen C, Kemski MM, Hu J, Mitchell TK, Rappleye CA. Histoplasma yeast and mycelial transcriptomes reveal pathogenic-phase and lineage-specific gene expression profiles. BMC Genomics. 2013;14: 695. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joehnk B, Ali N, Voorhies M, Walcott K, Sil A. Recyclable CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene disruption and deletions in Histoplasma. mSphere. 2023;8: e0037023. doi: 10.1128/msphere.00370-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bookout AL, Cummins CL, Mangelsdorf DJ, Pesola JM, Kramer MF. High-throughput real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2006;Chapter 15: Unit 15.8. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1508s73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parente-Rocha JA, Parente AFA, Baeza LC, Bonfim SMRC, Hernandez O, McEwen JG, et al. Macrophage Interaction with Paracoccidioides brasiliensis Yeast Cells Modulates Fungal Metabolism and Generates a Response to Oxidative Stress. PLoS One. 2015;10: e0137619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lozoya-Pérez NE, García-Carnero LC, Martínez-Álvarez JA, Martínez-Duncker I, Mora-Montes HM. Tenebrio molitor as an Alternative Model to Analyze the Sporothrix Species Virulence. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;Volume 14: 2059–2072. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S312553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim W, Konings M, Parel F, Eadie K, Strepis N, Fahal A, et al. Inhibiting DHN- and DOPA-melanin biosynthesis pathway increased the therapeutic value of itraconazole in Madurella mycetomatis infected Galleria mellonella. Med Mycol. 2022;60: myac003. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myac003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doan TL, Pollastri M, Walters MA, Georg GI. The Future of Drug Repositioning. Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Elsevier; 2011. pp. 385–401. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Talevi A. Drug Repurposing. Comprehensive Pharmacology. Elsevier; 2022. pp. 813–824. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pasqualotto AC, Queiroz-Telles F, Chebabo A, Leitao TMJS, Falci DR, Xavier MO, et al. The “Histoplasmosis Porto Alegre manifesto”-Addressing disseminated histoplasmosis in AIDS. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17: e0010960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mohammad H, Abutaleb NS, Seleem MN. Auranofin Rapidly Eradicates Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in an Infected Pressure Ulcer Mouse Model. Sci Rep. 2020;10: 7251. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64352-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Onodera T, Momose I, Kawada M. Potential Anticancer Activity of Auranofin. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2019;67: 186–191. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c18-00767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thangamani S, Maland M, Mohammad H, Pascuzzi PE, Avramova L, Koehler CM, et al. Repurposing Approach Identifies Auranofin with Broad Spectrum Antifungal Activity That Targets Mia40-Erv1 Pathway. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7: 4. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yaakoub H, Staerck C, Mina S, Godon C, Fleury M, Bouchara J-P, et al. Repurposing of auranofin and honokiol as antifungals against Scedosporium species and the related fungus Lomentospora prolificans. Virulence. 2021;12: 1076–1090. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1909266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu H, Lu W, Zhu Y, Wang C, Shi L, Li X, et al. Auranofin Has Advantages over First-Line Drugs in the Treatment of Severe Streptococcus suis Infections. Antibiotics. 2020;10: 26. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10010026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong SSW, Samaranayake LP, Seneviratne CJ. In pursuit of the ideal antifungal agent for Candida infections: high-throughput screening of small molecules. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19: 1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Almeida-Paes R, de Andrade IB, Ramos MLM, Rodrigues MV de A, do Nascimento VA, Bernardes-Engemann AR, et al. Medicines for Malaria Venture COVID Box: a source for repurposing drugs with antifungal activity against human pathogenic fungi. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2021;116: e210207. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760210207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maslanka R, Zadrag-Tecza R. Reproductive Potential of Yeast Cells Depends on Overall Action of Interconnected Changes in Central Carbon Metabolism, Cellular Biosynthetic Capacity, and Proteostasis. IJMS. 2020;21: 7313. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Almeida AJ, Cunha C, Carmona JA, Sampaio-Marques B, Carvalho A, Malavazi I, et al. Cdc42p controls yeast-cell shape and virulence of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Fungal Genet Biol. 2009;46: 919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li CH, Cervantes M, Springer DJ, Boekhout T, Ruiz-Vazquez RM, Torres-Martinez SR, et al. Sporangiospore size dimorphism is linked to virulence of Mucor circinelloides. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7: e1002086. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crabtree JN, Okagaki LH, Wiesner DL, Strain AK, Nielsen JN, Nielsen K. Titan cell production enhances the virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2012;80: 3776–3785. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00507-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Man A, Mare A-D, Mares M, Ruta F, Pribac M, Maier A-C, et al. Antifungal and anti-virulence activity of six essential oils against important Candida species—a preliminary study. Future Microbiol. 2022;17: 737–753. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2021-0296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang L, Zhang J, Song T, Yuan L, Zhou J, Yin H, et al. Antifungal curcumin promotes chitin accumulation associated with decreased virulence of Sporothrix schenckii. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;34: 263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Samie S, Trollope KM, Joubert L-M, Makunga NP, Volschenk H. The antifungal and Cryptococcus neoformans virulence attenuating activity of Pelargonium sidoides extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;235: 122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson CH, Klotz MG, York JL, Kruft V, McEwen JE. Redundancy, phylogeny and differential expression of Histoplasma capsulatum catalases. Microbiology. 2002;148: 1129–1142. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-4-1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bohse ML, Woods JP. RNA interference-mediated silencing of the YPS3 gene of Histoplasma capsulatum reveals virulence defects. Infect Immun. 2007;75: 2811–2817. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00304-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilson-Sanders SE. Invertebrate models for biomedical research, testing, and education. ILAR J. 2011;52: 126–152. doi: 10.1093/ilar.52.2.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ségalat L. Invert ebrate Animal Models of Diseases as Screening Tools in Drug Discovery. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2: 231–236. doi: 10.1021/cb700009m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Canteri de Souza P, Custódio Caloni C, Wilson D, Sergio Almeida R. An Invertebrate Host to Study Fungal Infections, Mycotoxins and Antifungal Drugs: Tenebrio molitor. J Fungi. 2018;4: 125. doi: 10.3390/jof4040125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are deposited in BioStudies, accession number S-BSST1660, and can be found at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/studies/S-BSST1660 or under the DOI 10.6019/S-BSST1660. These data were used to generate the results presented within the manuscript and/or its supplementary file.