Resumo

Fundamento

A associação entre a duração do sono e a aterosclerose foi relatada em muitos estudos observacionais. No entanto, pouco se sabe sobre a sua importância como fator de risco para aterosclerose ou como consequência negativa da aterosclerose.

Objetivo

Este estudo teve como objetivo avaliar a associação causal entre a duração do sono e o risco de aterosclerose usando estatísticas resumidas de estudos de associação genômica ampla (GWAS) disponíveis publicamente.

Métodos

Empregamos um método de randomização mendeliana (RM) de duas amostras com 2 coortes do MRC-IEU (n = 460.099) e do UK Biobank (n = 361.194) para investigar a associação causal entre a duração do sono e o risco de aterosclerose. Três métodos, incluindo a técnica de variância inversa ponderada (IVW), escore de perfil ajustado robusto (RAPS) e abordagem de mediana simples e ponderada, foram usados para obter resultados confiáveis, e uma razão de chances com intervalo de confiança (IC) de 95% foi calculada. P<0,05 foi considerado diferença estatística. Além disso, foram utilizadas análises de regressão: MR-Egger regression, Radial MR, MR-PRESSO e leave-one-out para avaliar os possíveis efeitos de pleiotropia.

Resultados

Não foi encontrada associação causal entre duração do sono e aterosclerose [OR (IC95%): 0,90 (0,98-1,00), p = 0,186]. As análises Leave-one-out, MR-Egger, e MR-PRESSO não conseguiram detectar pleiotropia horizontal.

Conclusões

Esta análise de RM não indicou nenhuma associação causal entre a duração do sono geneticamente prevista e a aterosclerose nas populações europeias.

Palavras-chave: Duração do Sono, Aterosclerose, Análise da Randomização Mendeliana

Introdução

A aterosclerose é uma doença multifatorial e a principal causa de eventos cardiovasculares e cerebrovasculares.1 A aterosclerose é uma característica multifatorial complexa com uma etiologia genética enigmática. Sendo uma doença crónica que ameaça gravemente a saúde humana, tem despertado grande atenção, especialmente a aterosclerose coronária. Assistimos a uma "transição epidemiológica".2 O aumento do saneamento e o tratamento de infecções agudas reduziram a prevalência de doenças infecciosas nos países em desenvolvimento, e mais indivíduos sofrem agora de doenças crónicas, como a aterosclerose.3 A aterosclerose pode levar a uma variedade de doenças cardiovasculares (DCV), que têm sido reconhecidas como uma das principais causas de morbidade e mortalidade.4 É urgente interpretar o seu mecanismo, avançar na sua gestão e desenvolver perspectivas para mitigar o seu impacto.

O sono é um processo fisiológico complexo produzido pelo cérebro, que desempenha um papel muito importante na regulação das funções fisiológicas de vários sistemas do corpo. Com a contínua extensão do horário de trabalho na sociedade moderna, a forma como as pessoas trabalham e os hábitos de sono das pessoas também estão em constante mudança, e a redução do tempo de sono está a tornar-se um problema grave.5 Na verdade, descobriu-se que a duração curta e longa do sono está associada ao cálcio da artéria coronária6-8 e à espessura médio-intimal da carótida (CIMT),9,10 que são indicadores de aterosclerose em grandes artérias que alimentam o coração e o cérebro. Além disso, alguns estudos descobriram que um tempo de sono muito longo ou muito curto ainda aumentará a incidência de eventos cardiovasculares após o controle de fatores mistos, como obesidade, hipertensão e diabetes.11 Vários estudos observacionais também mencionaram a relação entre a duração do sono e a aterosclerose subclínica das artérias coronárias ou carótidas.12,13 No entanto, ainda não está claro se dormir pouco ou dormir demais contribui para a ocorrência de aterosclerose.

Até onde sabemos, a associação causal entre a duração do sono e a aterosclerose não foi avaliada. A randomização mendeliana (RM) é um método para verificar a causalidade, evitando confusão residual e superando a causalidade reversa em um cenário retrospectivo, que pode revelar estimativas causais de fatores de risco em doenças complexas usando variantes genéticas como variáveis instrumentais.14,15 Aqui, conduzimos um estudo de RM para avaliar a associação causal entre a duração do sono e o risco de aterosclerose.

Métodos

Design de estudo

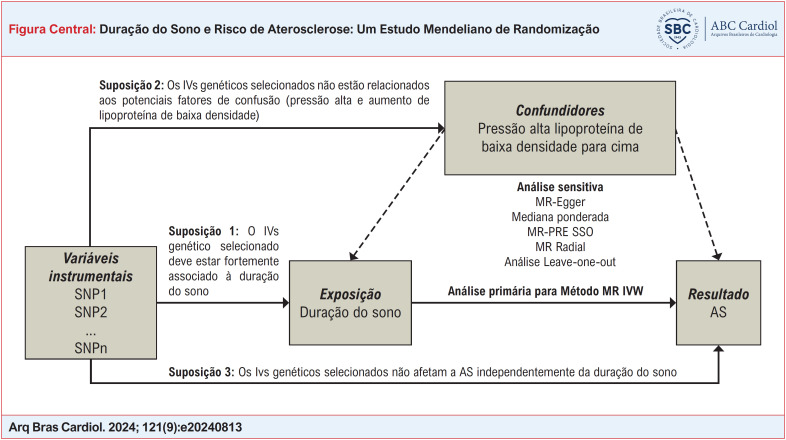

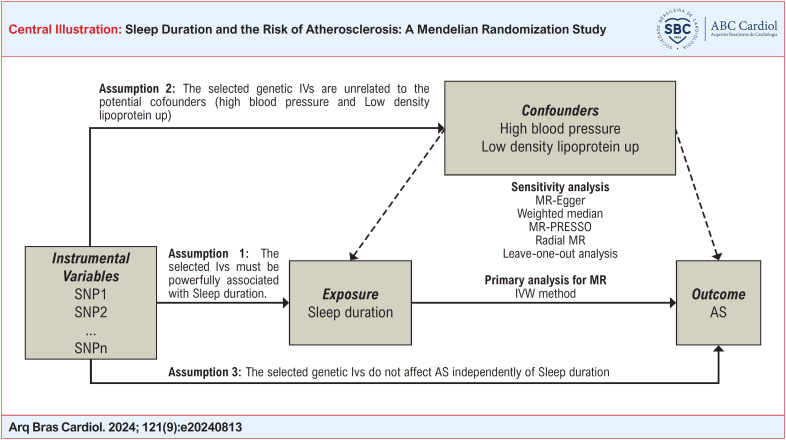

Supondo que a estimativa causal dos estudos de RM seja credível. Três suposições cruciais precisam ser atendidas: 1) Deve haver uma forte associação entre as variáveis instrumentais genéticas (IVs) selecionadas e a exposição.16 2) A escolha dos IVs genéticos não influencia o resultado sem considerar a exposição (ou seja, a pleiotropia horizontal é inexistente).17 3) Os IVs genéticos selecionados não estão associados aos possíveis confundidores. A Figura Central fornece uma visão geral. Como a pesquisa foi baseada em conjuntos de dados acessíveis ao público e em estudos publicados anteriormente, a aprovação ética e o consentimento dos participantes não foram necessários para o estudo.

Fontes de dados

As IVs para a duração do sono foram baseadas numa meta-análise de um estudo de associação genómica ampla (GWAS) de 460.099 pessoas de ascendência europeia. A duração habitual do sono autorreferida foi a principal exposição do presente estudo. Foi obtido a partir de questionários touchscreen na avaliação inicial. A duração do sono foi avaliada de acordo com uma pergunta padronizada: "Quantas horas você dorme a cada 24 horas?". Os participantes que responderam "Não sei" e "Prefiro não responder", e aqueles que forneceram durações de sono implausíveis (< 4 horas ou > 11 horas por dia) foram excluídos para minimizar a duração do sono implausível e potencial confusão por problemas de saúde. Uma descrição completa do desenho do estudo, dos participantes e dos métodos de controle de qualidade (CQ) foi descrita em detalhes anteriormente.18 O UK Biobank recebeu aprovação ética do Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa (a referência REC para o UK Biobank é 11/NW/0382).

A aterosclerose foi identificada com base nas 8ª e 10ª edições da Classificação Internacional de Doenças (CID). Os dados sobre aterosclerose foram coletados de participantes do United Kingdom Biobank (GWAS ID: ukb-d-I9_CORATHER, disponível em https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/ukb-d-I9_CORATHER/). Este conjunto de dados incluiu 361.194 pessoas de ascendência europeia (um total de 14.334 casos e 346.860 controles) e incluiu 13.586.589 polimorfismos de nucleotídeo único (SNPs). Introduzimos a regressão de pontuação LD ajustada por covariável (cov-LDSC), um método para estimar com precisão a herdabilidade genética (h2g) e seu enriquecimento em populações homogêneas e misturadas com estatísticas resumidas e estimativas de LD na amostra. A divulgação completa dos dados continha a coorte de amostras genotipadas com sucesso (n=488.377). 49.979 indivíduos foram genotipados usando o arranjo UK BiLEVE e 438.398 usando o arranjo axioma UK Biobank. Um total de 9.851.867 SNPs de duração do sono em 460.099 indivíduos foram extraídos do MRC-IEU (GWAS ID: ukb-b-4424, disponível em https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets/ukb-b-4424/). CQ pré-imputação, faseamento e imputação foram conduzidos pelo estudo anterior.19

A seleção das variáveis instrumentais relevantes

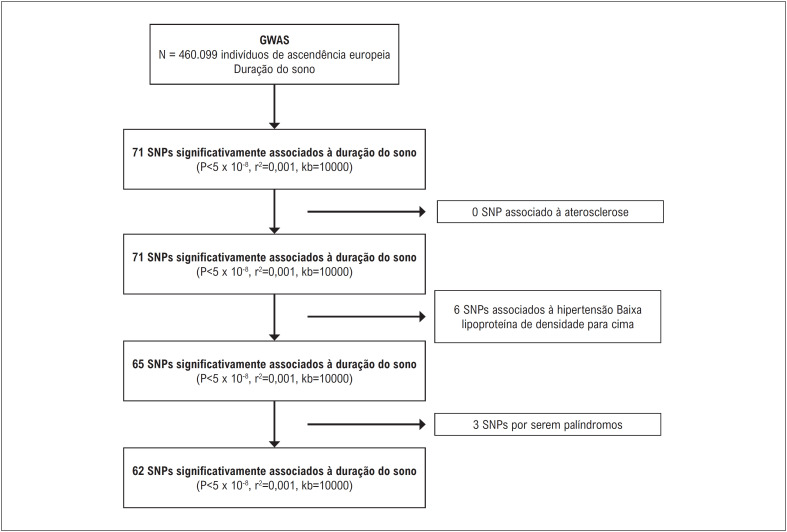

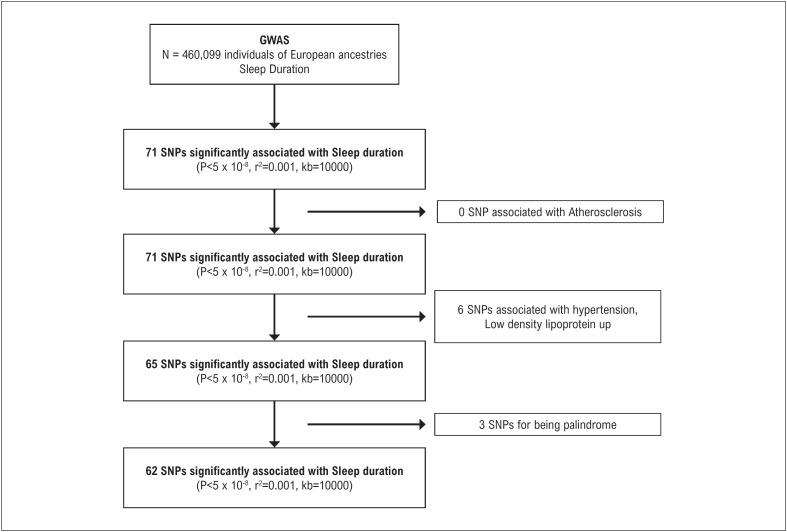

SNPs foram considerados IVs para este estudo.16 Os seguintes critérios foram satisfeitos por cada SNP solicitado: 1. Houve uma correlação substancial com a quantidade de exposição com base na relevância do genoma como um todo; 2. Sem desequilíbrio de ligação (LD) (r2 pareado = 0,001, tamanho da janela = 10.000kb); 3. Não contém estruturas palindrômicas. Um total de 65 SNPs foram encontrados após considerar as três suposições e critérios acima. Não conseguimos encontrar os SNPs apropriados no GWAS de aterosclerose, portanto, para obter estimativas precisas, empregamos SNPs proxy que tinham LD substancial (r2> 0,8) para substituir os SNPs escolhidos, o que nos permitiu obter resultados mais precisos. A regressão de primeiro estágio, ou estatística F, foi utilizada para avaliar a força dos instrumentos e foi calculada pela seguinte equação: F= (R2/k)/ ([1-R2]/[n-k-1]), onde R2 é a proporção da variabilidade da duração do sono contabilizada pelo SNP, k é o número de instrumentos utilizados no modelo e n é o tamanho da amostra.20 Para limitar a influência de um possível viés IV fraco, esperava-se que uma estatística F superior a 10 tivesse força suficiente para o estudo principal.21 O fluxograma para seleção de IVs está representado na Figura 1.

Figura 1. Fluxograma de seleção das variáveis instrumentais.

Análise estatística

A abordagem ponderada pela variância inversa (IVW) foi utilizada como principal método para determinar se havia correlação entre a duração do sono e a aterosclerose.22 Se o p do teste Q de Cochran fosse superior a 0,05, optou-se por utilizar um modelo com efeitos fixos; em todos os outros casos, utilizamos um modelo com efeitos aleatórios.23 Se os IVs selecionados não apresentassem pleiotropia direcional (e o p para o intercepto Mr-Egger fosse maior que 0,05), a técnica IVW era considerada a mais confiável.24

Escolhemos a abordagem Mr-Egger para avaliar os possíveis impactos da pleiotropia nas análises de sensibilidade. O termo de interceptação da regressão Mr-Egger, que estimou o efeito causal como a inclinação da regressão ponderada das relações IVs-resultado na relação IVs-exposição, refletiu o efeito pleiotrópico médio.25,26 Para determinar se havia pleiotropia, também utilizamos as técnicas de teste de outlier de mediana básica, mediana ponderada, Radial MR e MR-PRESSO (Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy Residual Sum and Outlier).26 Se mais de cinquenta por cento dos SNPs estudados fossem IVs eficazes, então a mediana ponderada oferecerá as estimativas mais confiáveis do impacto causal. Além da detecção de pleiotropia, o MR-PRESSO também pode reavaliar estimativas de efeitos e eliminar SNPs discrepantes.26 Para avaliar o impacto dos dados periféricos, foi entretanto realizada uma análise de exclusão. Investigamos ainda a pleiotropia de cada SNP escolhido usando o banco de dados PhenoScanner V2 (//www. pen scanner. medschl. cam. ac. uk/) no nível de significância estatística GWAS (p <5×10-8) para excluir o impacto de outras variáveis.27

Salvo indicação em contrário, todos os testes foram bilaterais e as diferenças foram consideradas estatisticamente significativas (p <0,05). Os pacotes Two Sample MR (V 0.5.6), Radial MR e MR-PRESSO (V 1.0)24 do software R foram usados para todas as análises estatísticas (4.0.5).

Resultados

Mais informações sobre os SNPs escolhidos são fornecidas na Tabela Suplementar S1-S2. Três SNPs no total (duração do sono: rs1611719, rs17732997 e rs2186122) foram eliminados da pesquisa de RM porque eram palíndromos. No final, 62 SNPs, incluindo 1 SNP proxy, foram escolhidos como IVs (todos p < 5×10-8, r2=0,001).

Estimativas de RM

Os resultados do teste Q de Cochran para o tempo de sono mostraram heterogeneidade mínima (p = 0,108). De acordo com os achados do método IVW, houve pouca evidência de ligação entre a duração do sono e o risco de aterosclerose (OR (IC 95%), 0,992 (0,979-1,004); p = 0,186) (Tabela Suplementar S3).

Análises de sensibilidade

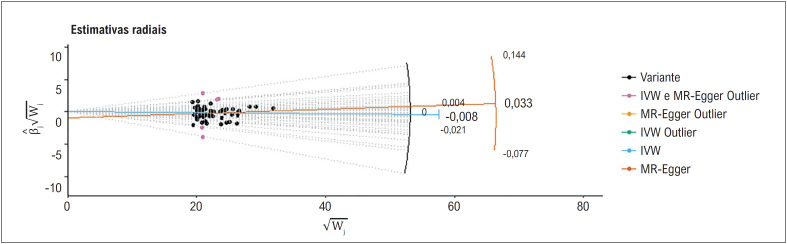

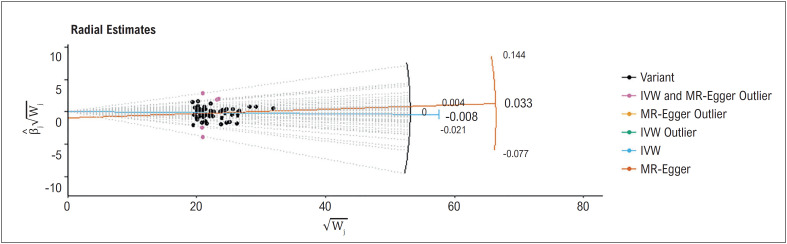

Os resultados da mediana simples e da mediana ponderada foram comparáveis aos da abordagem IVW. Enquanto isso, a pleiotropia horizontal não foi detectada pela regressão MR-Egger (interceptação p = 0,071 para duração do sono) (Tabela Suplementar S3). Embora o MR Radial sugerisse a existência de outliers (Figura 2), o MR-PRESSO mostrou que os outliers não afetaram os resultados do estudo (Tabela 1). Da mesma forma, a pleiotropia não foi detectada pelo RAPS (Tabela 2) e pelo banco de dados PhenoScanner V2. Quando a pleiotropia horizontal apresentou p > 0,05, o método IVW (efeitos fixos) (Tabela 2) foi utilizado para avaliar os dados. Para a duração do sono, as Figuras Suplementares S1-S4 apresentam gráficos de floresta, gráficos de dispersão, gráficos de funil e gráficos de exclusão de RM.

Figura 2. Uma visão geral do valor discrepante das estimativas radiais de RM.

Tabela 1. Estimativas MR-PRESSO entre duração do sono e aterosclerose.

| Característica | Estimativa bruta | Estimativa corrigida de outlier | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | IC 95% | p | N | OR | IC 95% | p | |

| Duração do sono | 62 | 0,991 | 0,979-1,003 | 0,163 | 62 | 0,991 | 0,979-1,003 | 0,163 |

SNP: polimorfismo de nucleotídeo único; MR-PRESSO: soma residual de pleiotropia de randomização mendeliana e teste de outlier. OR: razão de chances; IC95%: intervalo de confiança de 95%.

Tabela 2. Estimativas de RAPS e IVW (efeitos fixos) entre duração do sono e aterosclerose.

| Característica | RAPS | IVW (efeitos fixos) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | IC 95% | p | N | OR | IC 95% | p | |

| Duração do sono | 62 | 0,992 | 0,980-1,004 | 0,193 | 62 | 0,992 | 0,980-1,004 | 0,135 |

SNP: polimorfismo de nucleotídeo único; RAPS: escore de perfil ajustado robusto; IVW (efeitos fixos), variância inversa ponderada (efeitos fixos). OR: razão de chances; IC: intervalo de confiança.

Análises de viés e poder

O viés dos instrumentos genéticos foi de 0,000 para a duração do sono. A estatística F dos SNPs selecionados foi de 15.671, o que se esperava ter força suficiente para o estudo principal (Tabela Suplementar S3). A estimativa derivada da técnica de razão foi próxima da razão de chances condicional sob certas condições particulares e se aproximou de uma razão de chances média populacional.28,29 A consistência do estimador sob o valor nulo não foi afetada pela estimativa do odds ratio utilizada. Realizamos os cálculos de potência e o valor do erro Tipo 1 para a duração do sono foi de 0,05. Para o valor do poder estatístico do sono, a duração foi de 95%. De acordo com o tamanho da amostra utilizado na meta-análise de aterosclerose GWAS, houve poder> 80% para identificar a relação entre a quantidade de sono e o risco de aterosclerose para tamanho de efeito (OR) de 0,992 (Tabela Suplementar S4). Em recentes investigações adicionais de RM, todos os IVs para a duração do sono geneticamente prevista foram autorizados e utilizados.30,31 Além disso, nenhum deles teve qualquer influência na hipertensão arterial ou níveis elevados de lipoproteína de baixa densidade (Tabela Suplementar S3).

Discussão

No presente estudo, tentamos explorar a associação causal entre duração do sono e aterosclerose usando um método de RM. As nossas descobertas não mostraram nenhuma evidência de que a duração do sono geneticamente prevista esteja ligada ao risco de aterosclerose nas populações europeias. Além disso, estudos de sensibilidade mostraram que os resultados eram geralmente confiáveis.

Os escores de cálcio arterial coronariano (CACS), CIMT e velocidade da onda de pulso braquial-tornozelo (baPWV) foram os principais indicadores substitutos de aterosclerose e preditores de eventos cardiovasculares.6,32 Alguns estudos exploraram o efeito da duração do sono na incidência de aterosclerose, analisando a relação entre a duração do sono e CACS, CIMT e baPWV. Um estudo recente com 1.968 homens saudáveis com idades entre 40 e 60 anos indicou que o aumento ou diminuição da duração do sono estava associado a um aumento na incidência de aterosclerose coronariana e avaliou o efeito da duração do sono na incidência de arteriosclerose subclínica medindo a CACS, encontrando pessoas que dormiam por 7 horas teve a menor incidência de aterosclerose coronariana subclínica.33 Para pessoas com fatores de risco para aterosclerose, a duração do sono também foi significativamente correlacionada com a incidência de aterosclerose. Da mesma forma, a CIMT foi mais baixa quando o tempo de sono foi de 7 a 8 horas, e o aumento ou diminuição do tempo de sono levará a um aumento da CIMT.12

Estudos anteriores não mostraram relação entre a duração do sono e marcadores de dano vascular e aterosclerose.9,34-38 Uma pesquisa transversal com 1.093 homens japoneses relatou que a duração do sono autorreferida não estava associada ao aumento da CAC ou da CIMT.33 Souza et al.35 também não encontraram associações independentes da duração objetiva do sono com a CIMT. Nenhuma evidência demonstrou que a associação entre sintomas de insônia e pontuação CAC> 0 diferiu de acordo com o status objetivo de curta duração do sono.36 Além disso, um estudo sobre o Estudo Multiétnico de Aterosclerose (MESA) mostrou que a apneia obstrutiva do sono grave não estava associada a alta carga de CAC ou ITB anormal.37 Os investigadores do MESA não relataram associações entre durações de sono curtas (<6 horas) e longas (>8 horas) e CAC.38 Estes foram consistentes com nossas descobertas.

A ligação clínica e fisiologicamente significativa entre o sono prolongado e o risco de DCV em adultos não é apoiada por dados experimentais suficientes. Nossa hipótese, com base nas informações atuais, é que o mecanismo subjacente era de natureza metabólica e operava por via inflamatória. Especificamente, o sono prolongado pode levar a níveis baixos de HDL,39,40 hiperglicemia, hipertrigliceridemia41 e resistência à insulina,42 os quais podem levar à disfunção endotelial vascular e à inflamação subclínica, promovendo ainda mais a aterosclerose.43,44 Questões sociais, de estilo de vida e comportamentais relacionadas, como o abuso de drogas, a inatividade física ou a falta de acesso a refeições nutritivas, podem exacerbar este ambiente pró-aterogénico.45,46 Independentemente da real relação de causa e efeito, apoiamos o exame da duração do sono nas avaliações clínicas, uma vez que a duração curta ou longa do sono pode indicar risco de doenças crônicas. As DCV e a diabetes são doenças potencialmente fatais que prevalecem na nossa sociedade e podem levar à doença precoce e à morte, pelo que é importante investigar a relação entre o sono e as doenças crónicas ao longo do tempo. Isto inclui encontrar a melhor estratégia de prevenção para alertar contra a aterosclerose, que pode estimular DCV e outras doenças. Este é um passo importante para uma população mais saudável, tanto a nível nacional como global.

De acordo com o nosso conhecimento, este estudo foi a primeira investigação de RM a examinar a associação causal entre a duração do sono e o risco de aterosclerose utilizando conjuntos de dados GWAS disponíveis. Além disso, para esta investigação de RM de duas amostras, escolhemos pessoas da Europa para diminuir o preconceito demográfico. A atual pesquisa de RM também apresentou várias deficiências. Primeiro, como utilizamos dados genéticos acessíveis ao público para a nossa investigação, não fomos capazes de fazer análises estratificadas ou levar em consideração fatores adicionais. Em segundo lugar, os SNPs instrumentais escolhidos como IVs explicaram apenas parcialmente (0,001% -0,01%) a variação na duração do sono. Isto pode resultar de um baixo poder estatístico para identificar relações fracas. Terceiro, numa análise de RM de duas amostras, qualquer viés devido a instrumentos fracos foi na direção do nulo. O viés na direção do nulo foi menos sério do que o viés na direção da associação observacional, pois é conservador e não levará a taxas de erro tipo 1 inflacionadas e a resultados falso-positivos. Havia de fato uma possibilidade de sobreposição entre as duas amostras.28 Em última análise, uma vez que o nosso conjunto de dados era composto por pessoas de herança europeia, as nossas conclusões podem não se aplicar a outros grupos fora da Europa.

Conclusões

No presente estudo, a duração do sono geneticamente prevista entre as populações europeias não estava causalmente ligada ao risco de aterosclerose. Mais estudos são necessários para investigar a associação causal entre aterosclerose e duração do sono.

Agradecimentos

Agradecemos imensamente ao MRC-IEU e ao UK Biobank por fornecerem dados genéticos sobre o estudo de RM.

*Material suplementar

Para informação adicional da Tabela Suplementar, por favor, clique aqui.

Para informação adicional da Figura Suplementar, por favor, clique aqui.

Footnotes

Fontes de financiamento: O presente estudo foi financiado por Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20181505), Phase III Scientific Research Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine Superior Discipline in Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (No. ZYX03KF032), the Special Plan for the Science and Technology Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Jiangsu Province (No. 2020ZX08), the Leader Scientific Research Project of the Geriatric Clinical Technology Application Research Project of Jiangsu Provincial Health Comission (No LR202202), the Jiangsu Province Posgratuate Practice Innovation Program (No SJCX22 0766 and SJCX21 0670).

Vinculação acadêmica: Não há vinculação deste estudo a programas de pós-graduação.

Aprovação ética e consentimento informado: Este artigo não contém estudos com humanos ou animais realizados por nenhum dos autores.

Referências

- 1.Gao W, Sun Y, Cai M, Zhao Y, Cao W, Liu Z, et al. Copper Sulfide Nanoparticles as a Photothermal Switch for TRPV1 Signaling to Attenuate Atherosclerosis. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):231–231. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02657-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai H, Much AA, Maor E, Asher E, Younis A, Xu Y, et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Ischaemic Heart Disease and its Attributable Risk Factors, 1990-2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2022;8(1):50–60. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcaa076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libby P, Buring JE, Badimon L, Hansson GK, Deanfield J, Bittencourt MS, et al. Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):56–56. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0106-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mensah GA, Roth GA, Fuster V. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors: 2020 and Beyond. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(20):2529–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep Duration Predicts Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prospective Studies. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(12):1484–92. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim CW, Chang Y, Zhao D, Cainzos-Achirica M, Ryu S, Jung HS, et al. Sleep Duration, Sleep Quality, and Markers of Subclinical Arterial Disease in Healthy Men and Women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(10):2238–45. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King CR, Knutson KL, Rathouz PJ, Sidney S, Liu K, Lauderdale DS. Short Sleep Duration and Incident Coronary Artery Calcification. JAMA. 2008;300(24):2859–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthews KA, Strollo PJ, Jr, Hall M, Mezick EJ, Kamarck TW, Owens JF, et al. Associations of Framingham Risk Score Profile and Coronary Artery Calcification with Sleep Characteristics in Middle-aged Men and Women: Pittsburgh SleepSCORE Study. Sleep. 2011;34(6):711–6. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma CC, Burchfiel CM, Charles LE, Dorn JM, Andrew ME, Gu JK, et al. Associations of Objectively Measured and Self-reported Sleep Duration with Carotid Artery Intima Media Thickness Among Police Officers. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56(11):1341–51. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sands MR, Lauderdale DS, Liu K, Knutson KL, Matthews KA, Eaton CB, et al. Short Sleep Duration is Associated with Carotid Intima-media Thickness Among Men in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Stroke. 2012;43(11):2858–64. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuehn BM. Sleep Duration Linked to Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2019;139(21):2483–4. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolff B, Völzke H, Schwahn C, Robinson D, Kessler C, John U. Relation of Self-reported Sleep Duration with Carotid Intima-media Thickness in a General Population Sample. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196(2):727–32. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abe T, Aoki T, Yata S, Okada M. Sleep Duration is Significantly Associated with Carotid Artery Atherosclerosis Incidence in a Japanese Population. Atherosclerosis. 2011;217(2):509–13. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies NM, Holmes MV, Smith GD. Reading Mendelian Randomisation Studies: a Guide, Glossary, and Checklist for Clinicians. BMJ. 2018;362:k601–k601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carreras A, Zhang SX, Peris E, Qiao Z, Gileles-Hillel A, Li RC, et al. Chronic Sleep Fragmentation Induces Endothelial Dysfunction and Structural Vascular Changes in Mice. Sleep. 2014;37(11):1817–24. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Smith GD. Mendelian Randomization: Using Genes as Instruments for Making Causal Inferences in Epidemiology. Stat Med. 2008;27(8):1133–63. doi: 10.1002/sim.3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowden J, Smith GD, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent Estimation in Mendelian Randomization with Some Invalid Instruments Using a Weighted Median Estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40(4):304–14. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins R. What Makes UK Biobank Special? Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1173–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K, et al. The UK Biobank Resource with Deep Phenotyping and Genomic Data. Nature. 2018;562(7726):203–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer TM, Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sheehan NA, Tobias JH, Timpson NJ, et al. Using Multiple Genetic Variants as Instrumental Variables for Modifiable Risk Factors. Stat Methods Med Res. 2012;21(3):223–42. doi: 10.1177/0962280210394459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierce BL, Ahsan H, Vanderweele TJ. Power and Instrument Strength Requirements for Mendelian Randomization Studies Using Multiple Genetic Variants. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(3):740–52. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgess S, Smith GD, Davies NM, Dudbridge F, Gill D, Glymour MM, et al. Guidelines for Performing Mendelian Randomization Investigations: Update for Summer 2023. Wellcome Open Res. 2023;4:186–186. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15555.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes MV, Ala-Korpela M, Smith GD. Mendelian Randomization in Cardiometabolic Disease: Challenges in Evaluating Causality. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(10):577–90. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowden J, Smith GD, Burgess S. Mendelian Randomization with Invalid Instruments: Effect Estimation and Bias Detection Through Egger Regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(2):512–25. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, Ingelsson E, Thompson SG. Sensitivity Analyses for Robust Causal Inference from Mendelian Randomization Analyses with Multiple Genetic Variants. Epidemiology. 2017;28(1):30–42. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamat MA, Blackshaw JA, Young R, Surendran P, Burgess S, Danesh J, et al. PhenoScanner V2: An Expanded Tool for Searching Human Genotype-phenotype Associations. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(22):4851–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgess S. Sample Size and Power Calculations in Mendelian Randomization with a Single Instrumental Variable and a Binary Outcome. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):922–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harbord RM, Didelez V, Palmer TM, Meng S, Sterne JA, Sheehan NA. Severity of Bias of a Simple Estimator of the Causal Odds Ratio in Mendelian Randomization Studies. Stat Med. 2013;32(7):1246–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.5659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabrera JLR, Sotos-Prieto M, Ríos AG, Moffatt S, Christophi CA, Pérez-Martínez P, et al. Sleep and Association With Cardiovascular Risk Among Midwestern US Firefighters. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:772848–772848. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.772848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan XL, Nie L, Zhao SY, Zhang XB, Zhang S, Su ZF. The Association between Insomnia and Atherosclerosis: A Brief Report. Nat Sci Sleep. 2022;14:443–8. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S336318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aziz M, Ali SS, Das S, Younus A, Malik R, Latif MA, et al. Association of Subjective and Objective Sleep Duration as well as Sleep Quality with Non-Invasive Markers of Sub-Clinical Cardiovascular Disease (CVD): A Systematic Review. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24(3):208–26. doi: 10.5551/jat.36194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blasco-Colmenares E, Moreno-Franco B, Latre ML, Mur-Vispe E, Pocovi M, Jarauta E, et al. Sleep Duration and Subclinical Atherosclerosis: The Aragon Workers’ Health Study. Atherosclerosis. 2018;274:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki S, Arima H, Miyazaki S, Fujiyoshi A, Kadota A, Takashima N, et al. Self-reported Sleep Duration and Subclinical Atherosclerosis in a General Population of Japanese Men. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2018;25(2):186–98. doi: 10.5551/jat.40527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Souza SP, Santos RB, Santos IS, Parise BK, Giatti S, Aielo AN, et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Sleep Duration, and Associated Mediators With Carotid Intima-Media Thickness: The ELSA-Brasil Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41(4):1549–57. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.315644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertisch SM, Reid M, Lutsey PL, Kaufman JD, McClelland R, Patel SR, et al. Gender Differences in the Association of Insomnia Symptoms and Coronary Artery Calcification in the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2021;44(10):zsab116–zsab116. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagayoshi M, Lutsey PL, Benkeser D, Wassel CL, Folsom AR, Shahar E, et al. Association of Sleep Apnea and Sleep Duration with Peripheral Artery Disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Atherosclerosis. 2016;251:467–75. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lutsey PL, McClelland RL, Duprez D, Shea S, Shahar E, Nagayoshi M, et al. Objectively Measured Sleep Characteristics and Prevalence of Coronary Artery Calcification: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Sleep Study. Thorax. 2015;70(9):880–7. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams CJ, Hu FB, Patel SR, Mantzoros CS. Sleep Duration and Snoring in Relation to Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Women with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1233–40. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall MH, Muldoon MF, Jennings JR, Buysse DJ, Flory JD, Manuck SB. Self-reported Sleep Duration is Associated with the Metabolic Syndrome in Midlife Adults. Sleep. 2008;31(5):635–43. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi KM, Lee JS, Park HS, Baik SH, Choi DS, Kim SM. Relationship between Sleep Duration and the Metabolic Syndrome: Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey 2001. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(7):1091–7. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pyykkönen AJ, Isomaa B, Pesonen AK, Eriksson JG, Groop L, Tuomi T, et al. Sleep Duration and Insulin Resistance in Individuals Without Type 2 Diabetes: The PPP-Botnia Study. Ann Med. 2014;46(5):324–9. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.902226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dandona P, Aljada A, Bandyopadhyay A. Inflammation: The Link between Insulin Resistance, Obesity and Diabetes. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(1):4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Hypertension: A Novel Regulator of Adaptive Immunity in Atherosclerosis? Hypertension. 2004;44(3):257–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000140270.26523.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krueger PM, Friedman EM. Sleep Duration in the United States: A Cross-sectional Population-based Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(9):1052–63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stranges S, Dorn JM, Shipley MJ, Kandala NB, Trevisan M, Miller MA, et al. Correlates of Short and Long Sleep Duration: A Cross-cultural Comparison between the United Kingdom and the United States: The Whitehall II Study and the Western New York Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(12):1353–64. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]