Abstract

Objective Suprameatal tubercle (SMT), a bony prominence located above the internal acoustic meatus, is reported to impede the microscopic view during microvascular decompression (MVD) for trigeminal neuralgia (TN). For an enlarged SMT, removal of the SMT may be required in addition to the routine MVD to precisely localize the offending vessels. The objective of this study is to investigate the predictive factors influencing the requirement of SMT removal during trigeminal MVD.

Methods We retrospectively reviewed 197 patients who underwent MVD for TN, and analyzed the correlation of the SMT height and other clinicosurgical data with the necessity to remove the SMT during MVD. The parameters evaluated in the statistical analyses included maximum SMT height, patient's clinical characteristics, surgical data including the type and number of offending vessels, and surgical outcomes.

Results SMT removal was required for 20 patients among a total of enrolled 197 patients. In the univariate analysis, maximum SMT height, patient's age, and number (≥ 2) of offending vessels were associated with the requirement for SMT removal. Multivariate analysis with binary logistic regression revealed that the maximum SMT height and number (≥ 2) of offending vessels were significant factors influencing the necessity for SMT removal. A receiver operating characteristic curve analysis revealed that an SMT height ≥ 4.8 mm was the optimal cutoff value for predicting the need for SMT removal.

Conclusion Large SMTs and the presence of multiple offending vessels are helpful in predicting the technical difficulty of trigeminal MVD associated with the necessity of SMT removal.

Keywords: suprameatal tubercle, trigeminal neuralgia, microvascular decompression, petrous bone, offending vessels

Introduction

Microvascular decompression (MVD) is a widely performed microsurgical procedure for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (TN). 1 An enlarged suprameatal tubercle (SMT), the bony prominence above the internal acoustic meatus, may potentially obscure the view of the neurovascular conflict (NVC) site on the affected trigeminal nerve, although optimal exposure of the NVC site is crucial for a safe and complete MVD. 2 In such cases, the removal of the enlarged SMT may improve the surgeon's visualization of the NVC site. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 SMT removal, however, is a technically demanding procedure, which requires meticulous maneuvers and experience, due to the potential risk of injuring the surrounding neurovasculature and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 12 13 Of 197 consecutive patients who underwent MVD at our institute over 7 years (2011–2017), 20 required SMT removal to complete the MVD. The estimated incidence of an enlarged SMT affecting trigeminal nerve visualization during MVD is reported to range from 1.7 to nearly 10% 4 8 9 10 ; however, the predictive SMT height cutoffs and the impact of associated clinicosurgical variables on the need for SMT removal remain poorly defined. The authors, therefore, retrospectively analyzed these clinical cases to determine the impact of SMT height and other clinicosurgical parameters influencing the need for SMT removal during trigeminal MVD, with the predictive SMT height cutoff value requiring SMT removal. Surgical nuances are also described to perform safe and complete MVD with fewer potential complications of injuring the surrounding neurovasculature and CSF leakage.

Methods

Patient Population

Of 204 consecutive patients who underwent MVD for TN at our institute between January 2011 and December 2017, 197 were enrolled in the present study after excluding those who were recurrent cases or lacked offending vessels during surgery. All patients presented with primary TN and no other unusual neurological signs or symptoms, and all patients were refractory to medical treatment (primarily carbamazepine) and/or Gamma Knife therapy prior to undergoing MVD. We retrospectively evaluated the medical records, radiographic data, operative findings, and treatment outcomes of the included patients.

Surgical Procedures

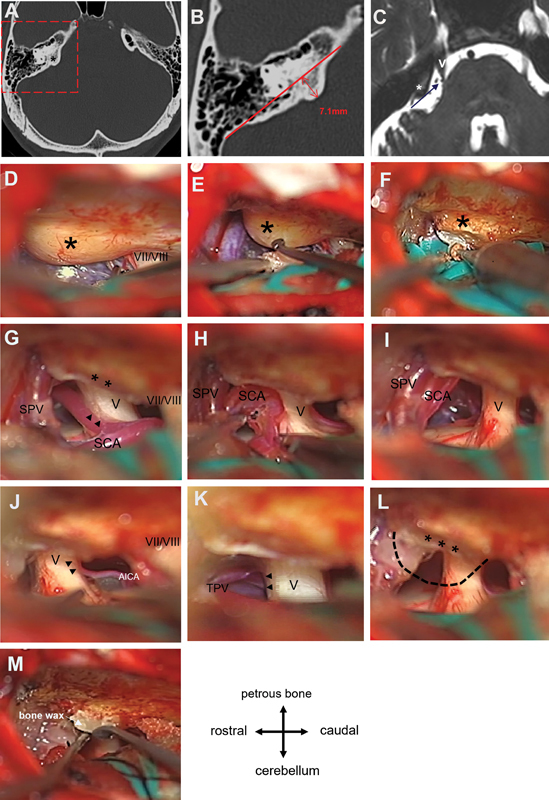

All MVDs were performed via standard suboccipital retrosigmoid craniotomy, as previously described. 1 14 All microsurgical procedures were performed by the first author (K.I.) and the senior author (H.T.), while the first author (K.I.) supervised every microsurgical procedure and made a decision on the necessity of SMT removal to reduce operator-based variability. The key steps of the surgical procedures utilized for trigeminal MVD combined with SMT removal were as follows: (1) skeletonization and preservation of the superior petrosal vein (SPV) complex via the meticulous dissection of the surrounding arachnoid membrane, if present; (2) retraction of the dura mater over the SMT, followed by careful drilling of the SMT using a high-speed drill or ultrasonic aspirator while protecting the surrounding neurovascular structures to avoid mechanical or thermal injury. The cerebellar surface and the surrounding neurovascular structures, including the SPV and the trigeminal, facial, and vestibulocochlear nerves, were covered with silicone rubber sheets for protection from potential mechanical and/or thermal injury generated by the high-speed drill. Gentle brain retraction was crucial to avoid excessive stress to the SPV. Drilling was performed using a 2-mm cutting or diamond drill with continuous saline irrigation. Notably, an ultrasonic aspirator can also generate mechanical and/or thermal injury. Subsequently, the enlarged SMT was shaved toward the posterior edge of the petrosal bone, enabling the precise identification of the NVC site on the trigeminal axis from the root entry zone to the juxta-petrous portion; (3) resolution of the NVC after thorough inspection of all offending vessels throughout the entire length of the trigeminal nerve; and (4) sealing the surface of the drilled petrous edge with bone wax or muscle fragments to minimize the risk of CSF leakage, if necessary. A representative example of the detailed surgical procedures is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Representative example of preoperative radiographic examinations and key steps of microvascular decompression (MVD) combined with suprameatal tubercle (SMT) resection. ( A ) Axial slice of the bone-window computed tomography (CT) showing an enlarged SMT (asterisk) with no pneumatization under the bone cortex on the right side. ( B ) Magnified view of the area indicated by the dotted line in ( A ). The height of the SMT was measured as the maximum width of the protuberance superior to the posterior edge of the petrosal ridge (7.1 mm, double-headed arrow). ( C ) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image showing an enlarged SMT (asterisk). Blue arrow projected through the top of the SMT (asterisk) on the trigeminal nerve (V), indicating the operative view of the suboccipital retrosigmoid craniotomy during trigeminal MVD. SMT blocks the view of the trigeminal nerve (V). ( D ) Large SMT (asterisk), markedly projecting and obstructing the operative corridor. VII/VIII: facial/vestibulocochlear nerves. ( E ) Dura mater over the SMT (asterisk) peeled off with a microdissector. ( F ) Careful drilling of the SMT (asterisk) under adequate protection of surrounding neurovascular structures. ( G–I ) Partial resection of the SMT (double asterisks) enabling inspection of the contact (double arrows) between the trigeminal nerve (V) and superior cerebellar artery (SCA). The SCA was meticulously dissected for adequate mobilization and was successfully transposed on the tentorium. The superior petrosal vein (SPV) being carefully preserved via meticulous skeletonization. ( J ) A small branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) contacting the trigeminal nerve (V) from the caudal side (double arrows), which was successfully mobilized and transposed. ( K ) Transverse pontine vein (TPV) running near the juxta-petrous portion of the trigeminal nerve (V) with mild compression (double arrows), which was successfully mobilized and transposed. ( L ) All three offensive vessels were transposed to confirm complete resolution from vascular compression. The dotted line below the stamp of the shaved bone (triple asterisks) indicates the outline of the SMT prior to drilling. ( M ) Surface of the drilled petrous edge sealed with bone wax.

Measurement of SMT Height

Using thin-sliced (1 mm slice thickness) axial bone window computed tomography (CT) images, the SMT height was measured as the maximum width of the bony protuberance superior to the posterior edge of the petrosal ridge at the slice just above the internal acoustic meatus, as previously described ( Fig. 1 ). 8 Measurements were obtained by a single investigator (M.U.), who was blinded to the patients' clinical information. Bone window CT images were also used to determine the presence of pneumatization in the SMT.

Assessment of Clinical Characteristics and Surgical Data

Clinical characteristics were assessed using medical records. Patient's age was defined as the age at the time of the surgery. Offensive vessels (vessel type and number) were evaluated based on preoperative radiographic and intraoperative data. Surgical outcomes were assessed at a median follow-up duration of 3.6 years after surgery (range, 18 months–10 years), and categorized according to the Barrow Neurological Institute (BNI) pain intensity score, as follows: I—no pain; II—occasional pain without medications; III—some pain, adequately controlled with medications; IV—some pain, not adequately controlled with medications; and V—severe pain or no pain relief with medications. 15 The study population was divided into two groups: patients who underwent SMT removal ( n = 20) and those who did not ( n = 177). Variables, including SMT height, clinical characteristics, surgical findings, and outcomes, were evaluated and compared between the two groups.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 4.2.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts, United States). Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation, whereas categorical variables were presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Univariate and multivariate analyses were both performed. The unpaired t -test was used for quantitative variables, whereas Fisher's exact test or chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Univariate analysis was initially performed to identify significant associations between individual variables, and those with a p -value ≤ 0.05 on univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis with binary logistic regression. The corresponding odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was included, with significance set at p ≤ 0.05. Furthermore, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to determine the optimal cutoff value (sensitivity and specificity) of SMT height for predicting the need for SMT removal.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Enrolled Patients

The baseline characteristics of the total 197 patients who underwent MVD for TN are shown in Table 1 . Patient's age ranged from 25 to 89 (63.3 ± 13.2) years, and 126 (64.0%) of the patients were female. SMT height of the affected side ranged from 1.3 to 7.4 (4.1 ± 1.2) mm, and SMT removal was required in a total of 20 (10.2%) patients. Superior cerebellar artery (SCA) was the most frequent (153 patients, 77.7%) offending vessel. Single and multiple offending vessels were found in 58.4 and 41.6% of the patients, respectively. The mean postoperative BNI score of the 197 patients was 1.42, and CSF leakage occurred in 2 (1.0%) patients as a complication.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 197 patients undergoing microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 63.3 (13.2) |

| Female gender | 126 (64.0) |

| Pain distribution | |

| V1 | 35 (17.8) |

| V2 | 138 (70.0) |

| V3 | 114 (57.9) |

| SMT height, mm, mean (SD) | 4.1 (1.2) |

| SMT removal | |

| Yes | 20 (10.2) |

| No | 177 (89.8) |

| Offensive vessels, type | |

| SCA | 153 (77.7) |

| AICA | 48 (24.4) |

| VBA | 4 (2.0) |

| Vein | 80 (40.6) |

| Others a | 4 (2.0) |

| Offensive vessels, no. | |

| 1 | 115 (58.4) |

| ≥2 | 82 (41.6) |

| Outcome, BNI pain score, mean (SD) | 1.42 (0.86) |

| Complication, CSF leak | 2 (1.0) |

Abbreviations: AICA, anterior inferior cerebellar artery; BNI, Barrow Neurological Institute; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; SCA, superior cerebellar artery; SD, standard deviation; SMT, suprameatal tubercle; VBA, vertebrobasilar artery.

Note: Unless otherwise indicated, the values are expressed as the number of patients (%).

Two posterior cerebellar artery and two primitive trigeminal artery variant.

Characteristics of the Patients with SMT Removal

SMT removal was required in a total of 20 patients (10.2%) ( Table 2 ). Age of the patients with SMT removal ranged from 29 to 73 (53.0 ± 13.2) years, and 15 (75.0%) of the patients were female. SMT height of the affected side ranged from 4.3 to 7.4 (5.7 ± 0.9) mm. SCA was the most frequent (18 patients, 90.0%) offending vessel. Single and multiple offending vessels were found in 30.0 and 70.0% of the patients, respectively. The mean postoperative BNI score of these 20 patients was 1.45, and no patient suffered from CSF leakage as a complication.

Table 2. Univariate analysis between the patients either with or without SMT removal.

| Parameter | With SMT removal | Without SMT removal | p -Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 20 (10.2) | 177 (89.8) | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 53.0 (13.2) | 64.5 (12.8) | 0.00068 |

| Female gender | 15 (75) | 111 (62.7) | 0.33 |

| Pain distribution | |||

| V1 | 2 (10.0) | 33 (18.6) | 0.55 |

| V2 | 13 (65.0) | 125 (70.6) | |

| V3 | 11 (55.0) | 103 (58.2) | |

| SMT height, mm, mean (SD) | 5.7 (0.9) | 3.9 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Offensive vessels, type | |||

| SCA | 18 (90.0) | 135 (76.3) | 0.26 |

| AICA | 10 (50.0) | 38 (21.5) | |

| VBA | 0 | 4 (2.3) | |

| Vein | 8 (40.0) | 72 (40.7) | |

| Others | 0 | 4 (2.3) | |

| Offensive vessels, no. | |||

| 1 | 6 (30.0) | 109 (61.6) | 0.0069 |

| ≥2 | 14 (70.0) | 68 (38.4) | |

| Outcome, BNI pain score, mean (SD) | 1.45 (0.69) | 1.42 (0.88) | 0.43 |

| Complication (CSF leak) | 0 | 2 (1.1) | |

Abbreviations: AICA, anterior inferior cerebellar artery; BNI, Barrow Neurological Institute; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; SCA, superior cerebellar artery; SD, standard deviation; SMT, suprameatal tubercle; VBA, vertebrobasilar artery.

Notes: Boldface type indicates statistical significance ( p < 0.05). Unless otherwise indicated, the values are expressed as the number of patients (%).

Factors Influencing the Requirement of SMT Removal

In the univariate analysis, the patients who underwent SMT removal ( n = 20) were significantly younger (53.0 ± 13.2 vs. 64.5 ± 12.8 years old; p = 0.00068) and had significantly taller SMT heights (5.7 ± 0.9 vs. 3.9 ± 1.3 mm; p < 0.0001) than the patients without SMT removal ( n = 177). The patients who underwent SMT removal had significantly higher incidence (70.0% [14 of 20] vs. 38.4% [68 of 177]; p < 0.0069) of multiple offensive vessels than those who did not. Females and right-sided lesions were predominant in both groups ( p > 0.05), and no statistically significant differences were noted for pain distribution, offensive vessel type, surgical outcomes, or other variables ( Table 2 ). Multivariate analysis with binary logistic regression revealed that the maximum SMT height (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.098–1.267; p < 0.0001) and the presence of multiple offending vessels (OR, 12.72; 95% CI, 3.480–59.620; p = 0.004) were significant factors influencing the need for SMT removal ( Table 3 ).

Table 3. Multivariate analysis using a binary logistic regression for requirement of SMT removal during microvascular decompression.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p -Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient's age | 0.96 | 0.915–1.004 | 0.0824 |

| SMT height | 1.17 | 1.098–1.267 | <0.0001 |

| Multiplicity of the offensive vessels | 12.72 | 3.480–59.620 | 0.0004 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SMT, suprameatal tubercle.

Note: Boldface type indicates statistical significance ( p < 0.05).

Optimal Cutoff Value for Predicting the Need of SMT Removal

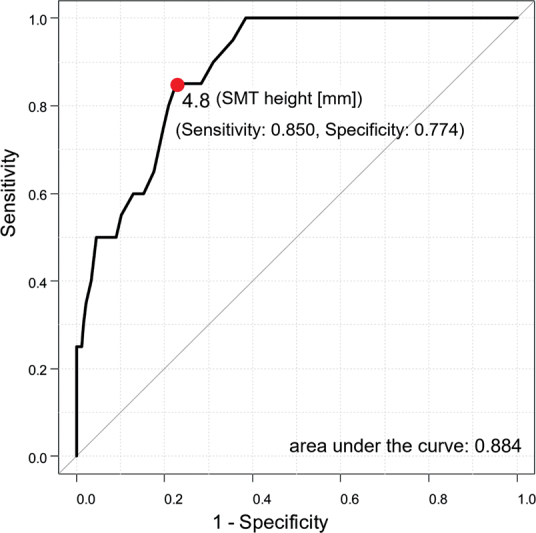

The ROC curve analysis revealed that an SMT height ≥ 4.8 mm was the optimal cutoff value for predicting the need for SMT removal (area under the curve, 0.884; 95% CI, 0.824–0.945) with a sensitivity of 85.0% and specificity of 77.4% ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis for the optimal cutoff value of maximum suprameatal tubercle (SMT) height for the need for SMT removal. SMT height ≥ 4.8 mm was the optimal cutoff value for predicting the need for SMT removal (area under the curve, 0.884; 95% confidence interval: 0.824–0.945) with a sensitivity of 85.0% and specificity of 77.4%.

Discussion

The SMT was first described by Seoane and Rhoton 2 in 1999, who defined it as the most prominent bony elevation on the posterior surface of the petrous bone, which is surrounded medially by the trigeminal notch, superiorly by the petrous ridge, and inferolaterally by the internal acoustic meatus. 2 Their microanatomical measurements from 15 cadaver heads demonstrated an average SMT height of 4.1 (2.8–6.0) mm above the posterior surface of the petrous ridge. 2 The results of the CT-based measurements on 197 operative cases in the present study revealed an average SMT height of 4.1 (1.3–7.4) mm, which was comparable to that of Seoane and Rhoton. 2 In a later study using 50 cadaver temporal bones, Acerbi et al 13 classified the variability of the prominence of the SMT into three major types: large size (> 6 mm; 9/50 cases); medium size (3–6 mm; 37/50 cases); and almost absent tubercles (< 3 mm; 4/50 cases). Oiwa et al 6 reported, via analysis of the SMT height of 106 patients who underwent three-dimensional CT, a mean SMT height of 1.4 to 1.7 mm, 5.2% of which were > 3 mm.

Surgical resection of the SMT with a petrous apex via a retrosigmoid approach was proposed to provide a surgical corridor from the posterior to the middle fossa through Meckel's cave. 11 12 13 16 The retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach has been utilized for resecting skull base tumors, such as petroclival meningiomas and trigeminal neurinomas. 11 12 13 16 The significance of an enlarged SMT as an obstacle obscuring the surgical view during trigeminal MVD was first described by Shenouda and Coakham 9 in 2007, who described an extremely enlarged SMT as a petrous endostosis, and reported 15 surgical cases of petrous endostosis which required bone drilling to precisely identify the NVC site during trigeminal MVD. 9 Since then, an increasing number of clinical case reports concerning SMT removal during MVD have been published. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Literature review of the cohort studies of such cases is summarized in Table 4 . Additionally, as an unusual case, there are very few reports documenting TN patients with enlarged SMTs causing the direct bony compression of the trigeminal nerve. 15

Table 4. Literature review of the cohort studies for SMT removal in microvascular decompression surgery.

| Author (year) | Incidence of SMT removal (%) | Age, mean (y) | SMT height a /imaging device | Offensive vessels, number | Outcome, pain relief | Complication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shenouda and Coakham (2007) 9 | 15/440 (3.4) | 44.3 | NA | Single or none: 6/15 (40%) Multiple: 9/15 (60%) |

15/15 (100%) | CSF leak (27%) |

| Inoue et al (2020) 4 | 8/461 (1.7) | 52.0 | 6.0 mm/MRI (3D reconstructed) | Single: 8/8 (100%) Multiple: 0/8 (0%) |

7/8 (88%) | Facial numbness (12.5%) Recurrence (12.5%) CSF leak (0%) |

| Rennert et al (2021) 8 | 4/43 (9.3) | 55.2 | 3.4 mm/MRI | Single: 2/4 (50%) Multiple: 2/4 (50%) |

NA | CSF leak (0%) |

| Yang et al (2022) 10 | 3/80 (3.8) | NA | 9.0 mm/NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Present study | 20/197 (10.2) | 53.0 | 5.7 mm/thin-slice CT | Single: 6/20 (30%) Multiple: 14/20 (70%) |

20/20 (100%) | CSF leak (0%) |

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; NA, not available; SMT, suprameatal tubercle.

Mean SMT height of the patients with requirement of SMT removal.

Several factors are known to be associated with the technical difficulty of trigeminal nerve MVD, including the involvement of dolichoectatic vertebrobasilar arteries as an offending vessel, 17 well-developed SPV complexes as a vascular obstacle, 14 and enlarged SMTs as a bony obstacle. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Multivariate analysis with logistic regression, performed in the present study, indicated that an enlarged SMT and a multiple number of offending vessels are indicative of the need for SMT removal during trigeminal MVD. Shenouda and Coakham 9 reported that multiple offending vessels (SCA in combination with vein) were involved in 9 of 15 (60%) cases who underwent SMT removal ( Table 4 ). To the best of the authors' knowledge, however, the present study is the first report indicating that the multiplicity of offending vessels is a predictive factor for the need for SMT removal during MVD via detailed statistical analysis. Furthermore, ROC curve analysis in the present study revealed that an SMT height of ≥ 4.8 mm is the optimal cutoff value for predicting the need for SMT removal. Recently, Inoue et al 4 reported that the mean SMT height which obscures the NVC site was 5.0 mm above the petrous surface, by analyzing preoperative three-dimensional reconstructed images of 461 patients undergoing trigeminal MVD. They reported that the NVC site was obscured by an enlarged SMT in 48 patients (10.4%) via the retrosigmoid approach. 4 The result of the ROC curve analysis performed in the present study is consistent with that of Inoue et al. 4

The surgical outcomes of the 20 cases in the present study in which the SMT was removed during the MVD were favorable, with no major perioperative complications including CSF leak. Drilling the SMT, however, requires meticulous maneuvers and experience, due to the potential risk of injury to the surrounding neurovasculature or CSF leak. 3 4 5 7 8 9 The working corridor for SMT removal is restricted by important neurovascular structures: superiorly by the SPV and trigeminal nerve, and inferiorly by the facial and vestibulocochlear nerves. Therefore, special attention is required, to avoid injury to these important neurovascular structures. Injury to these important neurovascular structures during SMT drilling may cause severe complications, including venous insufficiency, facial numbness, facial palsy, hearing impairment, and cerebellar dysfunction. Furthermore, sacrificing the SPV complex may cause venous outflow-related complications, including sinus thrombosis, intracranial hemorrhage, and brain stem/cerebellar infarction. 8 We skeletonized the SPV complex by meticulously dissecting the surrounding arachnoid membrane to preserve it whenever possible. Moreover, we covered the SPV complex with rubber sheets to protect it from mechanical and thermal injuries during SMT shaving. The main trunk of the SPV could be preserved in all cases resulting in the absence of venous outflow-related complications, although small tributaries of the SPV were uneventfully sacrificed in five cases. Shenouda and Coakham 9 reported 4 cases of CSF leak as a perioperative complication out of 15 surgeries. Thorough inspection and reconstruction of the exposed petrous air cells with bone wax or muscle grafts with fibrin glue is essential to minimize the risk of CSF leak, when necessary. 3 5 7 8 9 Several authors 4 5 8 9 16 have speculated that endoscopic assistance may be helpful in MVD with SMT removal. To our knowledge, however, no report has described actual endoscopic use in MVD surgery for TN patients with enlarged SMT. In two cases in this cohort, endoscopic assistance was used to better visualize the NVC site behind the enlarged SMT. Nevertheless, the key procedures of resolving the NVC necessitated manipulation under microscope after the removal of the enlarged SMT. Special instruments such as curved bipolar and scissors may be necessary to endoscopically manage NVC sites hidden behind large obstacles. If SMT removal results in insufficient exposure of the trigeminal nerve, endoscopic assistance or another surgical approach, such as an anterior petrosal approach, should be considered as an alternative. 4

Study Limitations

We recognize several limitations to our study. First, this was a single-center, retrospective study. A prospective, multicenter trial would provide more generalizable data. Second, two different surgeons performed MVD, and this might introduce operator-based variability. However, the first author (K.I.) supervised every microsurgical procedure and made a decision on the necessity of SMT removal to reduce operator-based variability. Third, other potential confounding variables including the patient comorbidities were not evaluated. Although these factors could have influenced our results, these limitations likely did not crucially attenuate the impact of this study.

Conclusion

The results of the present study indicated that large SMTs and the presence of multiple offending vessels are helpful in predicting whether the prominence of the tubercle necessitates additional intraoperative SMT drilling. Insight into the preoperative prediction of the need for SMT removal can facilitate surgical planning, patient risk estimation, and even the selection of an alternative surgical strategy or use of endoscopic assistance. We would like to emphasize the importance of recognizing this anatomic variation of the SMT when predicting operative difficulty and performing a safe and complete MVD with fewer potential complications.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Drs. Wataru Yoshizaki, Zyunpei Sugiyama, Takashi Hanyu, and Masahito Yamashita, Department of Neurosurgery, Tazuke Kofukai Medical Research Institute and Kitano Hospital for their assistance in data collection.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Toda H, Goto M, Iwasaki K. Patterns and variations in microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2015;55(05):432–441. doi: 10.2176/nmc.ra.2014-0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seoane E, Rhoton A L., Jr Suprameatal extension of the retrosigmoid approach: microsurgical anatomy. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(03):553–560. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199903000-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal N, Kumar A, Singh P, Chandra P S, Kale S S. Suprameatal extension of retrosigmoid approach in microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia with petrous endostosis: case report and literature review. Neurol India. 2022;70(03):1240–1243. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.349582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue T, Goto Y, Prasetya M, Fukushima T. Resection of the suprameatal tubercle in microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2020;162(05):1089–1094. doi: 10.1007/s00701-020-04242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreira-Holguin J C, Revuelta-Gutierrez R, Monroy-Sosa A, Almeida-Navarro S. Suprameatal extension of retrosigmoid approach for microvascular decompression of trigeminal nerve: case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;15:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oiwa Y, Hirohata Y, Okumura H et al. [Bone drilling in microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia: high morphological variety of the petrous bone] Neurol Surg. 2013;41(07):601–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peris-Celda M, Perry A, Carlstrom L P, Graffeo C S, Link M J. Intraoperative management of an enlarged suprameatal tubercle during microvascular decompression of the trigeminal nerve, surgical and anatomical description: 2-dimensional operative video. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2019;17(06):E247. doi: 10.1093/ons/opz027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rennert R C, Brandel M G, Stephens M L, Rodriguez A, Morris T W, Day J D. Surgical relevance of the suprameatal tubercle during superior petrosal vein-sparing trigeminal nerve microvascular decompression. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2021;20(06):E410–E416. doi: 10.1093/ons/opab046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shenouda E F, Coakham H B.Management of petrous endostosis in posterior fossa procedures for trigeminal neuralgia Neurosurgery 200760(2, suppl 1):ONS63–ONS69., discussion ONS69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang K, Shao M, Turpin J, Dehdashti A R.Suprameatal tubercle drilling during microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 202283(S01):S1–S270. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebner F H, Koerbel A, Roser F, Hirt B, Tatagiba M. Microsurgical and endoscopic anatomy of the retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach to lesions extending from the posterior fossa to the central skull base. Skull Base. 2009;19(05):319–323. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebner F H, Koerbel A, Kirschniak A, Roser F, Kaminsky J, Tatagiba M. Endoscope-assisted retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach to the middle fossa: anatomical and surgical considerations. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(01):109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acerbi F, Broggi M, Gaini S M, Tschabitscher M. Microsurgical endoscopic-assisted retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach: anatomical considerations. J Neurosurg Sci. 2010;54(02):55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toda H, Iwasaki K, Yoshimoto N et al. Bridging veins and veins of the brainstem in microvascular decompression surgery for trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;45(01):E2. doi: 10.3171/2018.4.FOCUS18122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibrahim B, Muhsen B A, Najera E, Borghei-Razavi H, Adada B. Case report of unusual cause of trigeminal neuralgia: trigeminal neuralgia secondary to enlarged suprameatal tubercle. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2021;66:102308. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chanda A, Nanda A.Retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach: advantages and disadvantages from an anatomical perspective Neurosurgery 200659(1, suppl 1):ONS1–ONS6., discussion ONS1–ONS6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honey C M, Kaufmann A M. Trigeminal neuralgia due to vertebrobasilar artery compression. World Neurosurg. 2018;118:e155–e160. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.06.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]