Abstract

Epilepsy, a widespread neural ailment considered by prolonged neuronal depolarization and repetitive discharge, has been linked to extreme stimulus of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs). Despite the availability of approved anti-seizure medications (ASMs) in many developed nations, approximately 30% of epilepsy patients continue to experience drug-resistant seizures. Thus, a growing interest in discovering natural compounds as potential sources for new medications is growing. Sinapinic acid, a natural derivative of cinnamic acid found in food sources, is known for its neuroprotective properties. This study investigated how sinapinic acid interacts with NMDA receptors and its potential role in providing anticonvulsant effects. Male mice were randomly allocated into nine groups: a control group receiving normal saline (1 ml/kg), groups treated with sinapinic acid at doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg, a group treated with diazepam at 10 mg/kg, a group treated with an NMDA agonist at 75 mg/kg, a group treated with an NMDA antagonist at 0.5 mg/kg, a group receiving the ineffective dose of sinapinic acid (1 mg/kg) along with the NMDA antagonist, and a group receiving the effective dose of sinapinic acid (10 mg/kg) along with the NMDA agonist. Sinapinic acid and other treatments were administered intraperitoneally 30 min prior to inducing seizures with PTZ injection. Seizure onset time was recorded following PTZ injection. Blood and brain samples were collected after anesthesia to determine serum and brain nitrite levels. Real-time PCR assessed NMDAR gene expression in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Data were analyzed using Prism software. The time seizures began was notably extended in groups treated with sinapinic acid at doses of 3 and 10 mg/kg compared to those treated with saline (P < 0.05). Additionally, in the receiving group of an ineffective dose of sinapinic acid alongside ketamine, the beginning of seizure time was significantly prolonged compared to the group that received the ineffective dose of sinapinic acid alone (P < 0.05). Serum and prefrontal cortex (PFC) nitrite levels were significantly lower in mice treated with sinapinic acid at doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg compared to the saline-treated group (P < 0.05). The gene expression of the NMDAR NR2B subunit in the PFC was decreased in groups treated with sinapinic acid at 1 and 10 mg/kg compared to the saline-treated group. Furthermore, co-administration of sinapinic acid (10 mg/kg) with NMDA resulted in significantly lower NR2A gene expression than the group treated with 10 mg/kg of sinapinic acid alone. Conversely, co-administration of ketamine with sinapinic acid (1 mg/kg) significantly increased NR2B subunit gene expression compared to the group treated with sinapinic acid at 1 mg/kg alone. Sinapinic acid showed anticonvulsant effects through reduced serum and PFC nitrite and modulation of glutamatergic signaling.

Keywords: Sinapinic acid, Natural product, Seizure, Medicinal plant, Oxidative stress, NMDA

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Neurology

Introduction

After migraine headaches, strokes, and Alzheimer’s illness, epilepsy is the fourth most common ailment of the nervous system. Epilepsy is a significant part of the world’s disease burden and affects about 50 million people worldwide. The Population from national registers is estimated to provide epilepsy incidence of about 0.6–0.7%1,2. Seizures involve a complex pathophysiological cascade involving various neurotransmitters, ion channels, and neuronal systems. The procedure typically launches into an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission, leading to hyper-excitability within neurons. This imbalance can emerge from genetic mutations affecting ion channels, neurotransmitter receptors, or synaptic proteins or from acquired damages such as brain injury, infection, or metabolic disturbances. Subsequent depolarization of neuronal membranes triggers the release of stimulating neurotransmitters, like glutamate, amplifying the depolarization and propagating aberrant electrical activity across neuronal networks3. Given the critical part of NMDA receptors in excitotoxicity and related diseases, including epilepsy, it seems that the barricade of NMDA receptors can effectively treat these related diseases4–6. Studies have also observed amplified expression of NMDA receptor subunits subsequent to seizure disease. For this reason, ionotropic NMDA receptors have received much attention for mechanistic and therapeutic aspects7. Additionally, it has been reported that some medicinal plants with antagonistic activity on NMDA receptors show significant anticonvulsant effects8,9.

An emerging line of evidence recommends a role for nitric oxide (NO) in the pathophysiology of seizures. NO, built by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzymes, acts as a signaling molecule, regulating synaptic transmission and plasticity. Increased NO production during seizures may lend to neuronal hyper-excitability by amplifying glutamatergic neurotransmission and reducing GABAergic inhibition. Furthermore, NO is able to respond by superoxide radicals to form peroxynitrite, a potent oxidant implicated in neuronal injury and neuroinflammation. Thus, dysregulation of NO signaling may intensify seizure action and neuronal damage10,11.

Current pharmacotherapies in seizures offer symptomatic relief for many individuals with epilepsy. Still, there remains a crucial need to identify novel therapeutic agents capable of healing treatment-resistant seizures and reducing adverse effects. Investigation of natural compounds from medicinal plants holds promise in this regard. These compounds often possess diverse pharmacological activities like neuroprotective properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, changing the levels of neurotransmitters, as well as the expression of their related receptors, making them attractive candidates for drug discovery of antiepileptic drugs with improved efficacy and safety profiles. Moreover, identifying and characterizing these compounds may provide valuable insights into the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of seizures and possibly the development of targeted therapies12,13.

Sinapinic acid is a phenylpropanoid compound abundantly in various medicinal plants and foods such as mustard seeds, broccoli, black sesame seeds, whole grains, and red cabbage. Regarding pharmacology, sinapinic acid has numerous beneficial properties and shows neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, memory improvement, and anti-anxiety activities. Sinapinic acid also shows anticonvulsant effects and reduces hippocampal neuronal damage by activating the glutamatergic pathway or oxidative stress14–16.

Given the compelling findings from prior research and the imperative to advance new and complementary treatment modalities for epilepsy, the main aim of this research is to study the effect of sinapinic acid on NMDA receptors as well as nitrite levels in regulating seizures.

Materials and methods

This study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Animals and ethics

This research involved 72 male NMRI mice, aged between 8 and 12 weeks and weighing 20–30 g, obtained from the Pasteur Institute of Iran in Tehran. The mice were housed in the Basic Health Sciences Research Institute animal lab at Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, where they were kept under standard light (12 h light/12 hours dark) and temperature (23 ± 1 °C). The mice had unrestricted access to water and standard laboratory food. Each mouse participated in the experiments only once. All techniques in this experiment adhered to the Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences standards and the guidelines provided by the NIH for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition, National Academies Press). Maximum efforts were made to minimize animal usage and promote their welfare. The study protocols received approval from the ethics committee of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences (Ethics committee reference: IR.SKUMS.REC.1397.86).

Study design

For the experimental procedure, the mice were randomly distributed in nine groups. The first group was administered normal saline at a 1 ml/kg dose, and the second through fourth groups were administered sinapinic acid in doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg, respectively15. The fifth group was treated with diazepam at a dose of 10 mg/kg17. The sixth group received an NMDA (NMDA agonist) at a 75 mg/kg dose. The seventh group was administered a dose of the ketamine (NMDA antagonist )at 0.5 mg/kg18. The eighth group received an effective dose of sinapinic acid alongside the NMDA. Lastly, the ninth group received an ineffective dose of sinapinic acid alongside the ketamine. Sinapinic acid, diazepam, ketamine, and NMDA agonist were intraperitoneally injected 30 min before PTZ administration. The dose and time of injections were used based on previous studies as well as our pilot study15,17,18.

At the conclusion of the experiment, the mice were euthanized under deep anesthesia with ketamine (60 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.)19. Blood samples were collected, and the serum was deposited at -80 °C after centrifugation. Furthermore, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) was extracted from the mice and kept at -80 °C till biochemical investigations and NMDAR gene expression evaluation using Real-time PCR. Finally, Animal carcasses were disposed of following the protocols outlined in the ethical guidelines for working with laboratory animals.

Induction of seizure

Seizures were induced in mice by injecting PTZ (0. 5% solution ) intravenously, using a Syringe Infusion Pump at a rate of 1 ml/min. The injection was stopped as soon as clonus of the anterior limb was observed, and the onset time of seizures was recorded for each mouse.

Measurement of PFC and serum nitrite level

Initially, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) was carefully dissected from the brains on ice and immediately transferred to liquid nitrogen for preservation. Subsequently, the tissue was homogenized in tris buffer (pH 7.4). The homogenized tissue was centrifuged at 3000 g for one minute at 4 °C, and nitrite levels were assessed using the Griess method. This method involves the diazotization of a sulfonamide by nitrite under acidic conditions, followed by coupling with N-(1-Naphthyl) ethylenediamine to produce a colored product. Each sample was initially mixed with Griess reagent in a 1:1 ratio (100 µL each). After incubation at room temperature for 10 min, the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using an automatic plate reader (LQ-300+ІІ-Epson, USA). Nitrite concentrations were determined by comparison to a standard reference (Sigma, USA)20.

Measurement of NMDARgene expression

NMDAR subunit gene expression (Nr2a, Nr2b) was assessed using real-time PCR. RNA was extracted from samples using RNX (Cinagen Company) and converted to cDNA with a Thermofisher kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific primers were designed with Vector ATI software (Table 1) and used in quantitative PCR reactions. The B2m gene served as a normalizer, and target gene expression changes were compared to the control group. QRT-PCR was performed on a Light Cycler with SYBR Premix EX Taq technology (Takara Bio, Japan) after reverse transcribing one microgram of RNA from each sample using a PrimeScript RT kit (Takara Bio Co., Japan). Expression changes were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt relative expression formula8.

Table 1.

Sequence of primers.

| Gene name | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| B2m | GGAAGTTGGGCTTCCCATTCT | CGTGATCTTTCTGGTGCTTGTC |

| NR2A | CTCAGCATTGTCACCTTGGA | GCAGCACTTCTTCACATTCAT |

| NR2B | CTACTGCTGGCTGCTGGTGA | GACTGGAGAATGGAGACGGC |

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into PRISM statistical software version 8 and checked for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test were used to analyze the data. Results were expressed as Mean ± SD, with significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

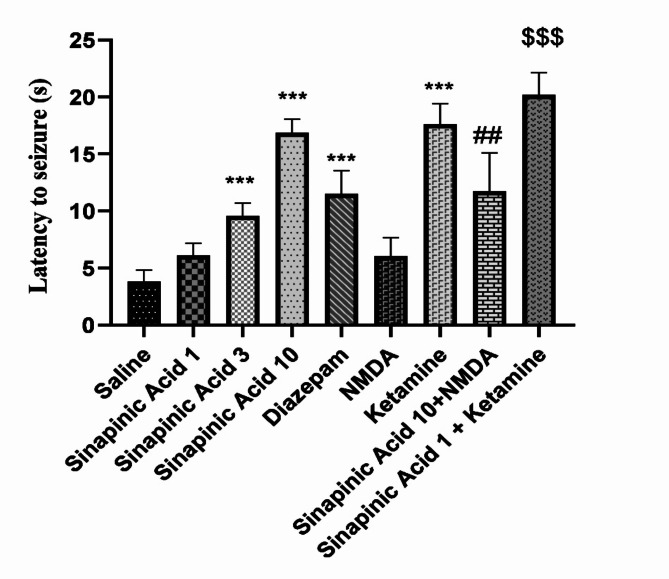

Comparison of the onset time of seizures in the studied groups

Based on the ANOVA results and Tukey’s post hoc analysis depicted in Fig. 1, the average time taken for seizures to initiate showed a significant increase in groups given sinapinic acid at doses of 3 and 10 mg/kg compared to those receiving normal saline (P < 0.001). Moreover, mice treated with the NMDA antagonist ketamine exhibited significantly delayed seizure onset times compared to the normal saline-treated group (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the onset time was notably prolonged in the diazepam-treated group compared to the normal saline-treated group (P < 0.001). Additionally, the group treated with ketamine in combination with the ineffective dose of sinapinic acid (1 mg/kg) had significantly delayed onset times compared to the group treated only with the ineffective dose of sinapinic acid (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the onset time was significantly shorter in the group treated with NMDA alongside the effective dose of sinapinic acid (10 mg/kg) compared to the group treated only with the effective dose of sinapinic acid (P < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of seizure onset times among experimental groups. Results are presented as Mean ± SD from 8 samples and were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. ***Indicates a significant difference compared to the normal saline-treated group at P < 0.001. ##Indicates a significant difference compared to the group treated with 10 mg/kg of sinapinic acid at P < 0.01. $$$Indicates a significant difference compared to the group treated with 1 mg/kg of sinapinic acid at P < 0.001. In the experimental design, ‘saline’ refers to the control group treated with normal saline, while ‘Sinapinic Acid 1, 3, 10’ refers to groups treated with sinapinic acid at 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg, respectively.

Comparison of serum nitrite levels in the studied groups

ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test showed that (Fig. 2) serum nitrite levels in mice receiving sinapinic acid at 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg were significantly lower than in the control group (P < 0.05, P < 0.001, and P < 0.001, respectively). Mice treated with the NMDA antagonist ketamine also had significantly lower nitrite levels compared to the saline group (P < 0.001). Additionally, the group receiving 1 mg/kg sinapinic acid combined with ketamine had significantly lower nitrite levels than the group receiving 1 mg/kg sinapinic acid alone (P < 0.001). However, nitrite levels in the group receiving 10 mg/kg sinapinic acid combined with an NMDA agonist did not differ significantly from the group receiving 10 mg/kg sinapinic acid alone (P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of serum nitrite levels across the experimental groups. Results are presented as Mean ± SD from 8 samples and were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. ***Indicates a significant difference compared to the normal saline-treated group at P < 0.001. *Indicates a significant difference compared to the normal saline-treated group at P < 0.05. $$$Indicates a significant difference compared to the group treated with 1 mg/kg of sinapinic acid at P < 0.001. In this context, ‘saline’ denotes the control group treated with normal saline, while ‘Sinapinic Acid 1, 3, 10’ refers to groups treated with sinapinic acid at 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg, respectively.

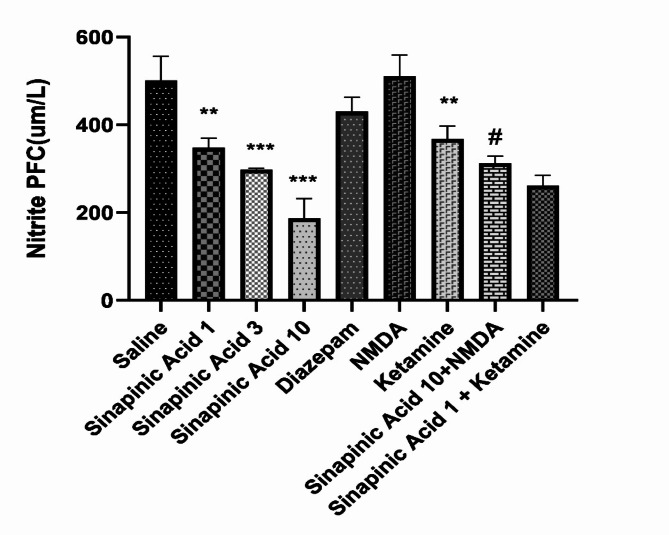

Comparison of PFC nitrite levels in the studied groups

According to the results of ANOVA analysis and Tukey’s post-hoc test, and based on Fig. 3, the brain nitrite level in mice receiving sinapinic acid in doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg was significantly lower than the control group (P < 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.001). PFC nitrite level in mice who received ketamine was significantly different from the saline-received group (P < 0.01).PFC nitrite level in mice who received diazepam and NMDA was not significantly different from the saline-received group (P > 0.05). Also, the PFC nitrite level in the group received the ineffective dose of sinapinic acid (1 mg/kg) alongside the ketamine was not significantly different from the group received the ineffective dose of sinapinic acid (P > 0.05). In addition, the level of PFC nitrite in the group received the effective dose of sinapinic acid (10 mg/kg) with NMDA was significantly increased compared to the group received the effective dose of sinapinic acid (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of prefrontal cortex (PFC) nitrite levels among the experimental groups. Data are presented as Mean ± SD from 8 samples and were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. ***Indicates a significant difference compared to the normal saline-treated group at P < 0.001. **Indicates a significant difference compared to the normal saline-treated group at P < 0.01. #Indicates a significant difference compared to the group treated with 10 mg/kg of sinapinic acid at P < 0.05. In this study, ‘saline’ refers to the control group treated with normal saline, while ‘Sinapinic Acid 1, 3, 10’ denotes groups treated with sinapinic acid at doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg, respectively.

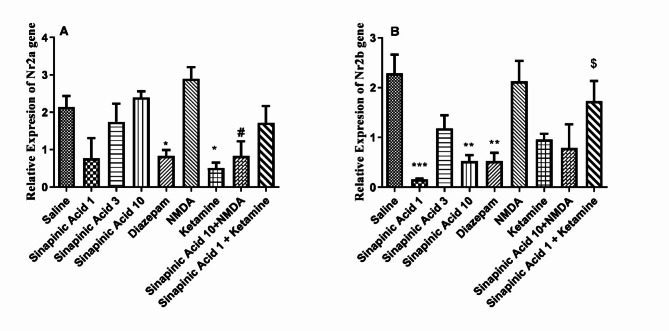

Expression level of subunits of NMDARs genes

According to the data presented in Fig. 4A, the expression of the NR2A subunit of NMDAR in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of mice administered sinapinic acid at doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg appeared lower compared to the control group, although this difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The group treated with an ineffective dose of sinapinic acid alongside ketamine showed no significant difference in NR2A subunit expression compared to the group treated with the ineffective dose of sinapinic acid alone (P > 0.05). However, NR2A subunit expression was significantly lower in the group treated with the effective dose of sinapinic acid in combination with NMDA compared to the group treated with the effective dose of sinapinic acid alone (P < 0.05). Additionally, treatment with diazepam and ketamine significantly reduced NR2A subunit gene expression compared to the saline-treated group (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of NR2A (A) and NR2B (B) subunit expressions in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) among the experimental groups. Data from this figure were presented as Mean ± SD from 8 samples and were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. ***Indicates a significant difference compared to the normal saline-treated group at P < 0.001. **Indicates a significant difference compared to the normal saline-treated group at P < 0.01. *Indicates a significant difference compared to the normal saline-treated group at P < 0.05. #Indicates a significant difference compared to the group treated with 10 mg/kg of sinapinic acid at P < 0.05. $ Indicates a significant difference compared to the group treated with 1 mg/kg of sinapinic acid at P < 0.05. In this study, ‘saline’ refers to the control group treated with normal saline, while ‘Sinapinic Acid 1, 3, 10’ denotes groups treated with sinapinic acid at 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg, respectively.

In Fig. 4B, the expression of the NR2B subunit in mice treated with sinapinic acid at doses of 1 and 10 mg/kg was significantly lower than in the saline-treated group (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively). Similarly, NR2B subunit expression was significantly lower in mice treated with diazepam compared to the saline-treated group (P < 0.01). However, there was no significant difference in NR2B subunit expression between mice treated with ketamine and NMDA compared to the saline-treated group (P > 0.05). Furthermore, the group treated with the ineffective dose of sinapinic acid alongside ketamine exhibited increased NR2B subunit gene expression compared to the group treated with the ineffective dose of sinapinic acid alone (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Understanding the changing aspects of seizure and its mechanism through pharmacological interventions is crucial for developing effective therapies for epilepsy. Still, a vital need remains to identify novel therapeutic agents capable of healing seizures and reducing adverse effects. Investigation of natural compounds from medicinal plants holds promise in this regard. Sinapinic acid is a phenylpropanoid compound widely present in plants and has anticonvulsant and neuroprotective effects16. Based on the potential activity of sinapinic acid, this study investigates the impact of sinapinic acid as a probable NMDA receptor modulator on seizure onset time, serum and PFC nitrite levels, and the expression of NMDARs subunits.

The onset time of seizures is a critical parameter in evaluating the efficacy of various compounds in seizure models. The study investigates the onset time of seizures in experimental groups treated with diazepam, different doses of sinapinic acid, NMDA, and ketamine alone or in combination with sinapinic acid. This delay may be attributed to sinapinic acid’s modulation of neurotransmitter systems, potentially involving glutamatergic pathways targeted by NMDA receptors. In this regard, Kim et al. (2010) showed that the oral administration of sinapinic acid (10 mg/kg) showed anticonvulsant effects against kainic acid-induced seizures and increased the delay time of seizure onset15. Ketamine, acting as an NMDAR antagonist, also prolongs seizure onset. This is consistent with the known mechanism of ketamine, which blocks NMDA receptors and inhibits glutamatergic neurotransmission, thereby reducing excitatory synaptic activity. Diazepam, a benzodiazepine enhancing GABAergic inhibition, similarly delays seizure onset, confirming its standard anticonvulsant effect21.

In addition, combining ketamine with an ineffective dose of sinapinic acid further prolonged seizure onset times compared to administering sinapinic acid alone at the ineffective dose. The observed enhanced anticonvulsant effect suggests a potential synergistic interaction between ketamine and sinapinic acid in delaying seizure onset, possibly through complementary mechanisms of action. Conversely, combining an effective dose of sinapinic acid with an NMDA agonist results in a shorter seizure onset compared to sinapinic acid alone, indicating a possible counteracting effect of NMDA agonists on sinapinic acid’s anticonvulsant activity.

Several studies have shown that NO may be involved in the pathogenesis of various neuroinflammatory/degenerative diseases. NO has a destructive effect on myelination in diseases such as multiple sclerosis. Excessive levels of NO in the brain are associated with tissue damage caused by cerebral ischemia and other neurodegenerative processes22. The results of comparing serum nitrite levels among experimental groups in this research showed that administering sinapinic acid in doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg significantly reduced serum nitrite levels compared to the control group. This reduction suggests a potential mechanism of action involving modulation of nitric oxide (NO) production or metabolism. Sinapinic acid may inhibit NO synthesis or increase its breakdown, leading to a decrease in serum nitrite levels.

Similarly, treatment with ketamine also significantly reduced serum nitrite levels compared to saline-treated mice, suggesting a potential role for NMDA receptors in NO regulation. The combination of an ineffective dose of sinapinic acid (1 mg/kg) with ketamine significantly reduced serum nitrite compared to the group that received an ineffective dose of sinapinic acid alone, indicating a possible synergistic interaction between the two compounds in modulating NO levels. However, when an effective dose of sinapinic acid (10 mg/kg) was combined with an NMDA agonist, there was no significant difference in serum nitrite levels compared to the group that received an effective dose of sinapinic acid alone. This suggests that the NMDA agonist may counteract the effects of sinapinic acid on NO regulation. These results showed that possibly another mechanism of sinapinic acid’s anticonvulsant activity is the inhibition of nitric oxide production, measured as end product, nitrite, similar to the animal studies of other researchers such as Kim et al. (2010) that showed the oral administration of sinapinic acid (10 mg/kg) to mice convulsed by kainic acid could decrease in the expression of the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) gene in the hippocampus15. Also, in the study of Lee et al. (2012), sinapinic acid (10 mg/kg/day, daily) showed neuroprotective effects in mice receiving amyloid protein in Parkinson’s model, causing a significant decrease in hippocampal iNOS expression23.

A comparison of PFC nitrite levels showed that administering sinapinic acid in doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg significantly reduced PFC nitrite levels compared to the saline-received animals. This reduction suggests a potential mechanism of action, such as its effect on serum nitrite levels.

Indeed, sinapinic acid may inhibit NO synthesis or enhance its degradation, specifically in the PFC, leading to decreased nitrite levels in this brain region. This is in line with the study of Zare et al. (2015), who reported that administering doses of 10 and 20 mg/kg of sinapinic acid in the 6-hydroxydopamine-induced hemi-parkinsonian rat caused a significant decrease in brain nitrite levels24. Similarly, treatment with the ketamine results in significantly different PFC nitrite levels compared to the saline-received group, suggesting a role for NMDA receptors in NO regulation in this brain region. Interestingly, treatment with diazepam, a GABA agonist, did not significantly alter PFC nitrite levels compared to its counterpart. This suggests that these compounds may not directly affect NO levels in the PFC or their effects on NO signaling are region-specific. In this regard, Vipin Sharma et al. (2015) presented that diazepam could not cause any change in plasma nitrite levels in non-stressed and stressed rats, which confirms the results observed in this study25.

Furthermore, combining an ineffective dose of sinapinic acid (1 mg/kg) with ketamine did not significantly alter PFC nitrite levels compared to the group received a non-effective dose of sinapinic acid alone, indicating no synergistic interaction between these compounds in modulating NO levels in the PFC. However, when an effective dose of sinapinic acid (10 mg/kg) is combined with NMDA, there is a significant increase in PFC nitrite levels compared to sinapinic acid alone, indicating a potential counteracting effect of NMDA agonists on sinapinic acid’s modulation of NO levels. In general, the findings of nitrite levels in serum and PFC show that sinapinic acid could modulate NO levels in PFC and serum, and its anticonvulsant effect can probably be exerted through this route in the brain region.

Previous studies have found that PTZ increases the concentration of intracellular calcium ions, and NMDARs play a role in this increase in concentration26. Also, in clinical studies, increased expression of NR2A and NR2B subunits has been shown in epilepsy associated with focal cortical dysplasia27. The expression of the NR2A subunit in mice receiving sinapinic acid at various doses shows a trend towards lower expression compared to the control group, although this difference is not statistically significant. This suggests that sinapinic acid may have a subtle modulatory effect on NR2A expression in the PFC. Interestingly, when the effective dose of sinapinic acid is combined with an NMDA agonist, NR2A subunit expression significantly decreases compared to sinapinic acid alone. This suggests a potential interaction between sinapinic acid and NMDARs, leading to the downregulation of NR2A subunit expression. Decreased NR2A expression may also be associated with neuroprotective effects against seizure. Additionally, treatment with diazepam and ketamine significantly reduces NR2A expression compared to the saline-received group, highlighting their impact on NMDAR gene expression.

Diazepam and sinapinic acid administration at 1 and 10 mg/kg doses significantly decreases NR2B subunit expression compared to the normal saline-received group. Reducing NR2B subunit expression by sinapinic acid and diazepam suggests a potential mechanism of downregulating NMDAR activity in the PFC, which could contribute to anticonvulsant effects. However, there is no significant difference in NR2B expression between the groups that received NMDA agonist/antagonist and the saline-received group. However, the lack of substantial changes in NR2B expression with NMDA agonist/antagonist treatment suggests a complex interplay between these compounds and NMDAR subunits, and these compounds may not directly influence NR2B expression. Interestingly, combining an ineffective dose of sinapinic acid with ketamine leads to an increase in NR2B expression compared to sinapinic acid alone, suggesting a potential counteracting effect or modulation of NR2B expression by ketamine in this context that necessitates further investigation into compensatory mechanisms or differing effects on receptor function.

Moreover, the differential effects of sinapinic acid on NR2A and NR2B NMDAR subunits, despite its anticonvulsant effects, likely reflect the complex and multifaceted regulation of NMDAR function. Further researches are needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms of these effects and their implications for the development of targeted therapies for epilepsy and other neurological disorders. One limitation of our study is that it only assessed NR2A and NR2B at the gene expression level. Future research should consider employing techniques such as Western blot analysis, immunohistochemistry, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to measure these markers’ protein levels to confirm these transcriptional changes at the protein level.

Conclusion

In conclusion, sinapinic acid increased the seizure onset time in mice. The NMDA antagonist potentiated while NMDA attenuated the anticonvulsant activity of sinapinic acid. Sinapinic acid decreased serum and PFC nitrite levels as well as decreased gene expression of NR2B subunit of NMDARs. These results indicate that sinapinic acid exhibits anticonvulsant effects through the reduction of nitrite as well as the modulation of glutamatergic signaling. However, results obtained from interventional therapies with NMDAR agonist/antagonists showed that anticonvulsant activity of sinapinic acid may did not mediated eactly via NMDAR alterations. Nevertheless, considering the limitations of this study, it is suggested that higher doses of sinapinic acid will be investigated, as well as its chronic effect in several animal models of seizures. In addition, if the impact of this natural compound is confirmed, future clinical studies are necessary to resolve the complexity of interventions in neurological disorders.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Research and Technology Deputy of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences for their valuable support. Additionally, the authors extend their thanks to the staff of the Medicinal Plants Research Center, particularly Mrs. Fatemeh Amini, for her assistance in conducting this study.

Abbreviations

- PTZ

Pentylenetetrazole

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- PFC

Prefrontal cortex

Author contributions

M.Gh: Performed the experiments; wrote the paper.E.B: Performed the experiments; wrote the paper. H.A-K, M.R and A. S: Analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the paper. ZL: Conceived and designed the experiments; contributed reagents, materials, and analysis data; performed the experiments; wrote the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by grant No. 3579 from the Research Council of Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences. A. Sureda was supported by the Spanish Government, Instituto de Salud Carlos III through the Fondo de Investigación para la Salud (CIBEROBN CB12/03/30038).

Data availability

At the Medical Plants Research Center, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, data concerning the current study can be obtained. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Zahra Lorigooini repository, [z.lorigooini@gmail.com].

Declarations

Consent for publication

All authors have agreed to publish this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Christensen, J. et al. Estimates of epilepsy prevalence, psychiatric co-morbidity and cost. Seizure. 107, 162–171 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paneth, N. The contribution of epidemiology to the understanding of neurodevelopmental disabilities. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 65, 1551–1556 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss, D. J., Day, S. M., Shavelle, R. M. & Wu, Y. W. Remote symptomatic epilepsy: does seizure severity increase mortality? Neurology. 60, 395–399 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourgeois, B. F., Dodson, E., Nordli, D. R. Jr, Pellock, J. M. & Sankar, R. Pediatric Epilepsy: Diagnosis and Therapy (Demos Medical Publishing, 2007).

- 5.Ghasemi, M. & Schachter, S. C. The NMDA receptor complex as a therapeutic target in epilepsy: a review. Epilepsy Behav. 22, 617–640 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeiler, F., Teitelbaum, J., Gillman, L. & West M. NMDA antagonists for refractory seizures. Neurocrit. Care. 20, 502–513 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho, Y. H. et al. Peripheral inflammation increases seizure susceptibility via the induction of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in the hippocampus. J. Biomed. Sci. 22, 1–14 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nasiri-Boroujeni, S. et al. NMDA receptor mediates the anticonvulsant effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Artemisia persica in PTZ-induced seizure in mice. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2021). (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Rosa-Falero, C. et al. Citrus aurantium increases seizure latency to PTZ induced seizures in zebrafish thru NMDA and mGluR’s I and II. Front. Pharmacol. 5, 284 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banach, M., Piskorska, B., Czuczwar, J., Borowicz, K. & S. & Nitric oxide, epileptic seizures, and action of antiepileptic drugs. CNS Neurol. Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Curr. Drug Targets-CNS Neurol. Disorders). 10, 808–819 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eghbali, F., Dehkordi, H. T., Amini-Khoei, H., Lorigooini, Z. & Rahimi-Madiseh, M. The potential role of nitric oxide in the anticonvulsant effects of betulin in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures in mice. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Keshavarzi, Z. et al. Medicinal plants in traumatic brain injury: neuroprotective mechanisms revisited. Biofactors. 45, 517–535 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohebbati, R., Khazdair, M. R. & Hedayati, M. Neuroprotective effects of medicinal plants and their constituents on different induced neurotoxicity methods: a review. J. Rep. Pharm. Sci. 6, 34–50 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hameed, H., Aydin, S. & Başaran, N. Sinapic acid: is it safe for humans? FABAD J. Pharm. Sci. 41, 39 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, D. H. et al. Sinapic acid attenuates kainic acid-induced hippocampal neuronal damage in mice. Neuropharmacology. 59, 20–30 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nićiforović, N. & Abramovič, H. Sinapic acid and its derivatives: natural sources and bioactivity. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 13, 34–51 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahmoudi, T. et al. Effect of Curcuma zedoaria hydro-alcoholic extract on learning, memory deficits and oxidative damage of brain tissue following seizures induced by pentylenetetrazole in rat. Behav. Brain Funct. 16, 1–12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahimi-Madiseh, M., Lorigooini, Z., Boroujeni, S. N., Taji, M. & Amini-Khoei, H. The role of the NMDA receptor in the anticonvulsant effect of ellagic acid in pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures in male Mice. Behav. Neurol. (2022). (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Ghasemi-Dehnoo, M. et al. Anethole ameliorates acetic acid-induced colitis in mice: Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2022). (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Granger, D. L., Taintor, R. R., Boockvar, K. S. & HibbsJr J. B. in Methods in enzymology Vol. 268 142–151Elsevier, (1996). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Gale, K. GABA and epilepsy: basic concepts from preclinical research. Epilepsia. 33, S3–12 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Łukawski, K. & Czuczwar, S. J. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration in animal models of seizures and epilepsy. Antioxidants. 12, 1049 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, H. E. et al. Neuroprotective effect of sinapic acid in a mouse model of amyloid β1–42 protein-induced Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 103, 260–266 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zare, K., Eidi, A., Roghani, M. & Rohani, A. H. The neuroprotective potential of sinapic acid in the 6-hydroxydopamine-induced hemi-parkinsonian rat. Metab. Brain Dis. 30, 205–213 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma, V., Gilhotra, R., Dhingra, D. & Gilhotra, N. Possible underlying influence of p38MAPK and NF-κB in the diminished anti-anxiety effect of diazepam in stressed mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 116, 257–263 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kłodzińska, A. et al. Roles of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in modulation of seizure activity. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 361, 283–288 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikuni, N. et al. NMDA-receptors 1 and 2A/B coassembly increased in human epileptic focal cortical dysplasia. Epilepsia. 40, 1683–1687 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

At the Medical Plants Research Center, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, data concerning the current study can be obtained. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Zahra Lorigooini repository, [z.lorigooini@gmail.com].