Abstract

In this study, a landslide susceptibility assessment is performed by combining two machine learning regression algorithms (MLRA), such as support vector regression (SVR) and categorical boosting (CatBoost), with two population-based optimization algorithms, such as grey wolf optimizer (GWO) and particle swarm optimization (PSO), to evaluate the potential of a relatively new algorithm and the impact that optimization algorithms can have on the performance of regression models. The Kerala state in India has been chosen as the test site due to the large number of recorded incidents in the recent past. The study started with 18 potential predisposing factors, which were reduced to 14 after a multi-approach feature selection technique. Six susceptibility models were implemented and compared using the machine learning algorithms alone and combining each of them with the two optimization algorithms: SVR, CatBoost, SVR-PSO, CatBoost-PSO, SVR-GWO, and CatBoost-GWO. The resulting maps were validated with an independent dataset. The performance rankings, based on the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) metric, are as follows: CatBoost-GWO (AUC = 0.910) had the highest performance, followed by CatBoost-PSO (AUC = 0.909), CatBoost (AUC = 0.899), SVR-GWO (AUC = 0.868), SVR-PSO (AUC = 0.858), and SVR (AUC = 0.840). Other validation statistics corroborated these outcomes, and the Friedman and Wilcoxon-signed rank tests verified the statistical significance of the models. Our case study showed that CatBoost outperformed SVR both in case the models were optimized or not; the introduction of optimization algorithms significantly improves the results of machine learning models, with GWO being slightly more effective than PSO. However, optimization cannot drastically alter the results of the model, highlighting the importance of setting up of a rigorous susceptibility model since the early steps of any research.

Keywords: Kerala, Landslide susceptibility, Machine learning, Metaheuristic algorithms, Regression, Western Ghats

Subject terms: Natural hazards, Hydrology

Introduction

Landslides are among the most devastating geological disasters occurring in mountainous terrain around the world and may be triggered by rainfall1,2, seismic activity3,4, volcanic activity5, variations in groundwater level6, toe erosion7,8, and anthropogenic activities that alter the stability of the terrain, such as mining or blasting9, hill slope cutting for road widening or constructing new roads7, and unscientific construction of structures7,10,11. These triggering (external) factors, depending on the intrinsic or predisposing factors (topography, soil, geology, and land use) of the area, can result in slope failures or landslides12,13. An investigation by Froude and Petley14 listed 55,997 deaths worldwide due to 4862 rainfall-induced landslides from 2004 and 2016. Their investigation found that around 75% of the incidences occurred in Asia alone, with India being the hotspot (highest incidences). A recent study by Gómez et al. 15 reported 185,753 deaths worldwide due to 37,946 landslides between 1903 and 2020, with the highest fatalities recorded in Asia. As per the study15, India ranks third in terms of the highest number of small (1–10 deaths) and moderate (11–100 deaths) landslide disasters and second in terms of the number of large (100 + deaths) landslide disasters. Moreover, according to Wang et al.16, India stands third, after China and Afghanistan, in the list of the top 10 nations where landslides pose the highest risk of casualties. Around 12.6% (approximately 0.42 million sq. km) of the total area of India is prone to landslides17, including the Himalayas (Northeast and Northwest), the Western Ghats (WG), the Konkan Hills, and the Eastern Ghats18. The Western Ghats are a mountain range that runs parallel to the west coast of India and encompasses Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra, and Gujarat states of India19,20. Kerala is an ideal site to study landslide susceptibility, as it is a landslide-prone area with old and recent landslide disasters. According to Hao et al.21, 4728 landslide incidences have been reported in the WG region in Kerala alone during the 2018 southwest monsoon.

Landslide susceptibility assessment can be defined as the spatial probability of landslide occurrence and is regarded as a basic and crucial step for landslide risk assessment and management22,23. Although landslide susceptibility studies date back to the 80 s of the last century and several approaches have been proposed since then, several recent literature reviews highlighted that, at present, Machine Learning (ML) algorithms are consolidated and cutting-edge methods to implement into landslide susceptibility models24–28. ML models such as random forest29,30, support vector machine (SVM)31, decision trees32, Naïve Bayes33, k-nearest neighbours34, gradient boosting algorithms35, support vector regression36, k-means clustering37, classification and regression tree38, multi-layer perceptron34, and neural networks39–42 have been extensively and effectively utilized by researchers for identifying landslide susceptibility. However, the development of newer and more powerful algorithms is constantly progressing, with the results of proposing ML algorithms that must be tested and evaluated in real case study applications. Support vector regression (SVR) and Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) can be included among recently developed algorithms. Support vector regression (SVR) has several advantages over other ML models: its computational complexity remains constant regardless of the dimensions of the input space, it exhibits exceptional generalization potential, and achieves high prediction accuracy43. The Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) regressor is an ensemble model based on the Gradient Boosting algorithm44. Boosting is an ensemble strategy that increases the accuracy of any given machine learning algorithm for both regression and classification tasks45,46. CatBoost can avoid overfitting, facilitates quick learning, and is well-suited for ML applications with categorical or heterogeneous data44,47. Being an ensemble model, CatBoost integrates various models to improve prediction accuracy and robustness, reduce uncertainties, and address the weak generalization of standalone ML models44,48. However, complex ML methods are sensitive to hyperparameters, which regulate the behaviour of ML algorithms and, ultimately, affect the final results. For instance, if the default values proposed by computing software are used, often optimal results are not obtained49,50. One effective solution is to utilize an optimization algorithm to adjust these hyperparameters and improve the models’ accuracy, speed, and scalability51–53.

Optimization is the iterative process of enhancing an ML model’s accuracy by reducing the error level. Optimization algorithms are of two types: individual-based and population-based54,55. Individual-based algorithms use a single randomly produced search agent to initiate the optimization process to find and locate the global optimum of the optimization issue55. Individual-based algorithms begin the process in the search space at a random starting point. Typically, they can only find the best solution in the immediate vicinity of that random point and cannot leave that area to look for other possible high-fitness regions inside the issue domain. Premature convergence that appears in two kinds of problems, known as uni-modal and multi-modal functions, is the primary drawback of the individual-based algorithm55. Premature convergence in uni-modal functions typically happens when the optimization process proceeds too slowly55. On the other hand, local optima entrapment is the primary reason behind premature convergence in multi-modal functions55. Population-based optimization algorithms offer several advantages, including the ability to search the solution space through multiple points (individuals or solutions) at the same time, the ability to share information and facilitate interactive learning between individuals with different search behaviours, and the fact that they are stochastic due to the inherent incorporation of randomness into search behaviours54.

Researchers integrated optimization algorithms such as bat algorithm56, cuckoo optimization algorithm56, grey wolf optimizer56, invasive weed optimization57, particle swarm optimization58, satin bowerbird optimizer59, teaching–learning-based optimization59, and whale optimization algorithm60 to different ML models for landslide susceptibility modelling. Particle swarm optimization (PSO) and grey wolf optimizer (GWO) are two such population-based optimization algorithms61. PSO’s fundamental concept is to mimic a swarm of fish, birds, or bees in search of food62. These species communicate with one another when searching for food to find their targets separately and stochastically and eventually advance towards the goal from different directions62. Finding the global optimum solution is more likely since a larger portion of the design space is examined, and the search pathways differ for various particles62. PSO offers notable benefits, such as greater precision and rapid convergence63. GWO mimics a pack of grey wolves’ hunting strategy and leadership hierarchy and can be applied to network optimization54. To replicate the leadership hierarchy, four different sorts of grey wolves—alpha, beta, delta, and omega—are used 64. Several notable benefits of the GWO algorithm include its minimal number of algorithm parameters, robust global optimization capability, simplicity of use, and superior convergence64,65.

This investigation sought to evaluate the landslide susceptibility of Kerala state in India by applying two ML regression algorithms such as SVR and CatBoost, integrating population-based metaheuristic optimization algorithms such as PSO and GWO, verifying whether the integration of these two metaheuristics improves the prediction capability of the ML regression models, comparing the predictive capability of all six models, and identifying the important predisposing factors. This study is relevant as ML and optimization algorithms are continuously evolving, and their joint use needs to be corroborated by applications in appropriate test sites, like Western Ghats. Though many researchers58,66–71 employed ML regression algorithms (MLRA) to assess the landslide susceptibility of different areas within the WG region, only Saha et al.58 integrated an optimization algorithm to enhance the prediction accuracy. Moreover, the novelty of this work lies also in the pioneering combination of different ML and optimization algorithms: to the best of our knowledge, it is the first time that PSO and GWO have been combined with ML-based standalone (SVR) and ensemble (CatBoost) regression models to assess landslide susceptibility. Furthermore, the relevance of the final results is enhanced by the fact that the existing susceptibility map (produced in the year 2010) used by the Kerala State Disaster Management Authority72 needs to be updated; hence, the methodology adopted in this modelling is of utmost importance.

Materials and methods

Study area

Kerala is situated in the southwestern region of peninsular India, with the Arabian Sea to the west and the Western Ghats (WG) to the east. The rock types include hard crystalline metamorphic rocks (charnockites, gneisses, and khondalites) of the Achaean age in the WG73. The mean annual precipitation is approximately 300 cm, which was brought about by two monsoon seasons: the southwest (June–September) and the northeast (October–November)21,74. In addition to this climatic condition, land use practices, deforestation, and soil erosion accelerate the weathering and, thereby, the occurrence of landslides75. The predominant lateritic soils result from chemical weathering of the underlying charnockites73,75. Administratively, the state (with 38,863 km2 of area) shares its boundary with the Tamil Nadu and Karnataka states (Fig. 1). Some of the notable landslide disasters that occurred in Kerala are displayed in Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Location of the study area and the devastating landslide disasters. Figure created with ArcGIS Pro software (Version 3.1; ESRI, Redlands, California, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

Table 1.

Some of the notable landslide disasters occurred in Kerala.

| Sl. No | Landslide disaster | District | Date | Fatalities | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amboori landslide | Thiruvananthapuram | November 9th, 2001 | 38 | Naidu et al.76 |

| 2 | Kavalappara landslide | Malappuram | August 8th, 2019 | 59 | Vasudevan et al.77 |

| 3 | Puthumala landslide | Wayanad | August 8th, 2019 | 17 | Vasudevan et al.77 |

| 4 | Pettimudi landslide | Idukki | August 6th, 2020 | 70 | Sajinkumar and Oommen78 |

| 5 | Kokkayar landslide | Idukki | October 16th, 2021 | 7 | Ajin et al.79 |

| 6 | Plappally and Kavali landslides | Kottayam | October 16th, 2021 | 10 | Ajin et al.79 |

| 7 | Kudayathoor landslide | Idukki | August 29th, 2022 | 5 | George et al.80 |

| 8 | Wayanad landslide | Wayanad | July 30th, 2024 | 452 deaths and 67 missing (As on September 9th, 2024) | District Emergency Operations Centre (DEOC), Wayanad |

Methodological framework

This modelling applied two-stage feature selection techniques, followed by two MLRAs, such as CatBoost and SVR, and integrated two population-based optimization algorithms, such as GWO and PSO, to assess the landslide susceptibility, different validation techniques, and finally assessed the factor importance. The flowchart of the susceptibility modelling is displayed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the susceptibility modelling.

Landslide inventory

The landslide inventory was extracted from two sources: the Bhukosh portal of the Geological Survey of India and the incidence data for the year 2018, published by Hao et al.21. The dataset of Hao et al.21 comprises 4728 incidence locations. This is a reconstructed inventory that utilized the incidence data of the year 2018 compiled by the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC)81 and derived based on the object-based image analysis (OBIA) algorithm82. The incidence data for 2018 prepared by the GSI was based on a detailed survey21. The inventory derived from the Bhukosh portal recorded 3164 landslide incidences in Kerala. This study combined these two datasets after removing 117 duplications. Thus, the final landslide inventory employed in this modelling comprises 7775 events (Fig. 3), mainly slides and flows68. This data was randomly separated into 70% (5443 landslides) and 30% (2332 landslides) as training and validation datasets, respectively83, with an equal number of non-landslide points. While comparing different data-splitting approaches, previous studies84,85 identified the 70:30 ratio as the best-performing split. At the same time, the 50:50 landslide and non-landslide sampling strategy is widely employed to maintain an equilibrium between positive and negative samples in the modelling83,86. A field survey was conducted to validate the accuracy of the landslide incidence locations, especially the ones identified by the GSI. This on-the-ground verification process provided first-hand information to confirm the presence of landslides and ensure the reliability of the inventory (Figs. 3a-c).

Fig. 3.

Landslide inventory – training and validation datasets – a., b., and c. Landslide sites. Figure created with ArcGIS Pro software (Version 3.1; ESRI, Redlands, California, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

Predisposing factors

As a starting point, the modelling considered 18 potential predisposing factors, selected based on existing literature68,87–91. Data were extracted from diverse sources (DEM, data portals, and published maps), as reported in Table 2. Predisposing factors such as slope angle, slope aspect, elevation, curvature, plan and profile curvatures, terrain ruggedness index (TRI), and topographic wetness index (TWI) were derived from the ALOS PALSAR DEM utilizing ArcGIS Pro spatial analyst and map algebra tools. Equations (1)92 and (2)93,94 were utilized to compute the TRI and TWI, respectively. Factors such as lineaments, lithology, and geomorphology were extracted from the Bhukosh portal, whereas soil bulk density and soil clay content were collected from the Soil Grids portal. The latest road networks were derived from the Planet OSM portal, and built-up area data was downloaded from the GHSL portal. The land use/land cover data (updated on the year 2022) was extracted from the Esri Land Cover portal. The soil texture and stream channels were derived from the soil map (NBSS&LUP) and topographic map (SoI), respectively95. The Euclidean distance tool in ArcGIS Pro was used to compute the distance from the lineaments, road networks, and stream channel raster layers.

| 1 |

where = elevation of each neighbour cell to cell (0,0)

| 2 |

where α = specific catchment area, β = local slope.

Table 2.

The data source of the predisposing factors (categorical factors are in bold).

| Data | Source | Data format | Potential predisposing factors | Spatial resolution/Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALOS PALSAR DEM | https://search.asf.alaska.edu/ | Raster |

Slope Elevation Aspect Curvature Plan curvature Profile curvature Terrain ruggedness index (TRI) Topographic wetness index (TWI) |

12.5 m |

| Bhukosh Portal | https://bhukosh.gsi.gov.in/Bhukosh/Public | Vector |

Distance from the fault Geomorphic units Lithology |

1:250,000 |

| Topographic map | Survey of India (SoI) | Vector | Distance from the stream channel | 1:50,000 |

| Soil map | National Bureau of Soil Survey & Land Use Planning (NBSS & LUP) | Vector | Soil texture | 1:250,000 |

| Soil Grids portal | https://soilgrids.org/ | Raster |

Soil bulk density Soil clay content |

250 m |

| Planet OpenStreetMap (OSM) portal | https://planet.openstreetmap.org/ | Vector | Distance from the road (2023) | Multiscale |

| European Commission’s Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL) portal | https://ghsl.jrc.ec.europa.eu/datasets.php | Raster | Built-up area (2023) | 100 m |

| Esri Land Cover portal | https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/landcover/ | Raster | Land use/land cover (2022) | 10 m |

Feature selection

Feature selection eliminates irrelevant or redundant predisposing factors, especially useful in case of a large number of input predisposing factors96,97. The presence of redundant factors will negatively influence the performance and accuracy of the algorithms29,98,99. In this study, we used a two-step procedure based on multicollinearity analysis and Information gain (IG) method to identify and discard the less important predisposing factors and to objectively define a selection of the optimal parameters for the susceptibility assessment.

Multicollinearity arises when a predisposing factor is very similar (highly correlated) to another100,101: this is a problem since it undermines the significance of a predisposing factor and adds unnecessary complexity to the model parameterization, which in turn may lead to overfitting issues. Similarly, the existence of multicollinearity will reduce the stability and performance of regression models102. Hence, similar factors should be excluded or redefined to distinguish them from others101. The most common techniques to evaluate multicollinearity are tolerance (TOL) and variance inflation factor (VIF), which were computed employing Eqs. (3) and (4)68,88. A predisposing factor has a multicollinearity problem when its VIF value exceeds 10, and its TOL value is lower than 0.188.

| 3 |

| 4 |

where = coefficient of determination of the jth predisposing factor.

IG is a metric that evaluates how much information a particular feature provides 103. The information entropy of sample set R, expressed as H(R), for random variables R and S, where R = {, , , …, } and S = {, , , …,}, will be computed by applying Eq. (5)104. H(R) is the prevailing metric for quantifying the purity of a set of samples103. As the value of decreases, the purity of R increases103.

| 5 |

where

The conditional entropy, denoted as , and joint entropy, denoted as , were computed utilizing equations (6) and (7)104.

| 6 |

| 7 |

The IG for class C and attribute A was computed using Eq. (8)104,105.

| 8 |

In this modelling, the threshold is set to be 0.05105, and any predisposing factor with an IG score below 0.05 will be discarded.

Machine learning regression algorithms

Support Vector Regression (SVR)

SVR is an SVM-based regression tool 106. SVR possesses a notable benefit in its ability to effectively handle nonlinear processes by utilizing a kernel function, which facilitates the projection of the original data into a linearly separable space of higher dimensionality 107. SVR utilizes a symmetrical loss function throughout the training process, which equally penalizes both overestimation and underestimation errors 43. For a training dataset where , , SVR seeks to identify a regression function capable of accurately fitting all training samples employing Eq. (9) 107.

| 9 |

where w = coefficient vector, Φ(x) = kernel function, and b = intercept

Categorical Boosting (CatBoost)

CatBoost is an ML ensemble algorithm based on Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT) and is particularly suitable for heterogeneous and categorical data47,108. The CatBoost algorithm inherently incorporates a mechanism to efficiently convert non-numerical data values into numerical ones without the need for parametric tuning and yields good results in a single execution109. Like other basic gradient lifting algorithms, the CatBoost algorithm creates a new tree and can improve the overfitting issues other traditional algorithms face110. The CatBoost algorithm employs a random sorting technique to arrange the data and subsequently assigns a numerical value to each attribute inside the categorical variables110. The utilization of priority factors and weight coefficients restricts the impact of low-frequency and noise data110. Equation (10)110 was employed for the training dataset D.

| 10 |

where j = number of samples (1,2, …n), = jth target value of X (, and = jth target value of Y.

Equation (11)109,110 was utilized for implementing the model.

| 11 |

where = indicator function, α = initial weight, and p = initial value.

CatBoost was also utilized for assessing the important predisposing factors. The feature importance was assessed using Eq. (12)111,112.

| 12 |

where = relevance of predictor variable in separating class h from the other classes, and = tree induced for the hth class at iteration n.

Population-based optimization algorithms

Optimization algorithms were introduced to reduce the likelihood of errors or losses arising from these predictions while enhancing the accuracy of the model52.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

The swarm behaviour of birds in flocks in nature served as the model for the PSO113. The particles (possible solutions) in PSO move by following the current optimum particles114. PSO requires less memory and is computationally fast114. The two main steps of PSO are as follows115:

Step 1: Velocity and position formulation: A swarm of particles can find a high-quality solution by updating their positions and velocities as they search through the feasible space. Each particle’s position indicates a potential solution for the optimisation issue. The position and velocity of particle are shown by m-dimensional vectors and , considering the decision contains variables. To regulate the velocities and direct the swarm, PSO defines two positions: the personal-best position, depicted as and the global-best position, depicted as . The velocity and position were computed employing Eqs. (13) and (14)115.

| 13 |

| 14 |

where = cognitive factor, = social factor, = inertia weight, = real numbers, and t = current generation.

Step 2: Linearly decreasing inertia weight: The careful choice of ω can effectively attain a balance between global search and local exploitation during the evolutionary process. A high ω value can enhance the global search, whilst a low ω value can facilitate local exploitation. Linearly decreasing ω can enhance the performance and be computed by applying Eq. (15)115.

| 15 |

where T = maximal generation, and = upper and lower limits.

Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)

GWO is a metaheuristic algorithm that draws inspiration from the behaviour of grey wolves54,65 and emulates the hierarchical structure of leadership and the hunting mechanism observed in grey wolves54. Furthermore, the implementation of the hunting process involves three primary stages, including the search for prey, the encirclement of prey, and the subsequent attack on prey54,116. The four types of wolves—alpha (α), beta (β), delta (δ), and omega (ω) —are meant to resemble the internal leadership hierarchy of wolves117. The top, second, and third-best wolves are recorded as α, β, and δ, while the others are classified as ω117. The α, β, and δ wolves exhibit a higher degree of proximity to their prey, while the ω wolves assume a secondary role by accompanying and assisting those above three in the tasks of searching, tracking, and surrounding their prey118. Once the circumference of the surrounding circle reaches a sufficiently reduced size, the predators initiate their attack and successfully capture the prey118. The three stages of GWO are as follows118:

Stage 1. Search for prey: The process of hunting commences with the act of searching for potential prey, and their behavioural patterns can be succinctly characterised by Eqs. (16) and (17)118.

| 16 |

| 17 |

where D = distance between the wolf and the prey, t = current iteration, = current position of the prey, = position vector, = updated position vector, and A, C = coefficient vectors

A was computed by applying Eq. (18), while C was computed by employing Eq. (19)118.

| 18 |

| 19 |

where a = , and = random vectors

Stage 2. Encirclement of prey: The prey will be encircled under the leadership of α, β, and δ wolves. The distance between these three wolves was computed employing Eqs. (20) to (21), and Eq. (26) was applied to assess how the individual wolf approaches the prey 118.

| 20 |

| 21 |

| 22 |

| 23 |

| 24 |

| 25 |

| 26 |

where are location of α, β, and δ wolves, respectively, and are random vectors.

Stage 3. Attack on prey: Upon the cessation of the prey’s motion, the pack of wolves initiates an attack on the prey. The individual wolf moves away from the prey and conducts a global search when |A|> 1. The grey wolf begins attacking its victim when |A|≤ 1.

Implementation of the models

The ArcGIS tool used the landslide and non-landslide locations to sample the thematic layers representing the predisposing factors and to create the training and validation datasets fed into the ML algorithms. The Python programming language was utilized in the Google Colab (https://colab.research.google.com/) to implement the models. Two metaheuristic algorithms (PSO and GWO) were utilized to fine-tune the hyperparameters of the SVR and CatBoost algorithms, and the optimized hyperparameters are displayed in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Optimized hyperparameters of the SVR algorithm.

| Algorithms | Kernel | Degree | Tolerance | Regularization parameter | Epsilon | shrinking | Size of the kernel cache | Fitness function (MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSO | rbf | 10 | 1 | 3 | 0 | True | 350 | 0.154 |

| GWO | rbf | 3 | 1 | 8 | 0 | False | 100 | 0.146 |

Table 4.

Optimized hyperparameters of the CatBoost algorithm.

| Algorithms | Iterations | Learning rate | Depth | Fitness function (MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSO | 71 | 0.0899 | 8 | 0.0665 |

| GWO | 97 | 0.0699 | 8 | 0.0656 |

Validation techniques

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve

The ROC curve is a two-dimensional graph which plots 1-specificity (false positive rate) on the abscissa and sensitivity (true positive rate) on the ordinate to determine the performance of a classification 119,120. Area under the ROC curve (AUC) is a scalar value that ranges between 0.5 and 1.0, depicting the overall performance of a model 121. AUC values between 0.5 and 0.6, 0.6 and 0.7, 0.7 and 0.8, 0.8 and 0.9, and 0.9 and 1.0 depict failure, poor, acceptable, excellent, and outstanding performance, respectively 122. AUC is the most employed performance metric to quantitatively determine the performance of landslide susceptibility models 123 since it is easy to calculate and interpret 124. The AUC provides a good scalar performance measure without relying on a specific threshold 125. AUC is useful for imprecise settings because it operates independently of class distributions and misclassification costs 124,125.

MAE, MSE, and RMSE

MAE, MSE, and RMSE can be effectively employed to validate the models by assessing the errors 126. MAE, MSE, and RMSE values can range from 0 to + ∞, and the model’s accuracy is higher when values are close to 0 127. MAE was computed utilizing Eq. (27) 128, while MSE and RMSE were computed utilizing Eqs. (28) and (29) 128,129, respectively.

| 27 |

| 28 |

| 29 |

where = actual value, = predicted value, and n = number of observations.

R-squared

The coefficient of determination (R-squared or R2) is the ratio of the explained variation to the total variation 130. The R2 value varies from 0 to 1 131, with 1 recommending perfect correlation and 0 specifying no correlation 127. Jierula et al. 127 listed five degrees of correlation for R2 values: 0 to 0.2 (very weak), 0.2 to 0.4 (weak), 0.4 to 0.6 (moderate), 0.6 to 0.8 (strong), and 0.8 to 1 (very strong). R2 was computed by applying Eq. (30) 127.

| 30 |

where = actual value, = predicted value, = mean, and n = sample size.

Friedman test

The Friedman non-parametric test assessed the significance employing Eq. (31) 132,133. A significance level (often denoted by α) of 0.05 (5% risk) is set as the threshold 134,135, and to determine the significance, α should be compared with the probability value (often denoted by P). When the P-value ≤ α, the null hypothesis (i.e., no difference between variables) can be rejected, and if the P-value > α, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected due to lack of evidence 136. In simple words, a P-value < 0.05 is considered significant (factors are significantly different), and a P-value > 0.05 is considered insignificant 137.

| 31 |

where n = number of density fractions, and k = number of samples.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test

Wilcoxon signed-rank, another non-parametric test utilized to compare two related or matched samples 138, can be employed to assess the statistical significance of the models 134,135. The Wilcoxon test computes the difference between the two values (d) and the absolute value of this difference (), sorts the pair based on the , and assigns numerical ranking (Rank 1 to the pair with the lowest 139. The ranks will be assigned + ve and –ve sign based on the deviation 140. Samples with values zero will not assigned ranks and excluded from the analysis 139. Finally, the and values will be computed as the sum of ranks assigned to samples with d < 0 and d > 0, respectively 139. The smaller and values will be the final z-statistic (T) 140 and were computed employing Eq. (32) 141. The performance of models varies significantly when the values are higher than + 1.96 or -1.96 134,135.

| 32 |

where = sample, and = rank.

Taylor diagram

The Taylor diagram can be effectively utilized to determine the efficacy of multiple models 142. Taylor diagram is a graphical depiction of the bias, correlation, and variance of the predictions with respect to the actual ones 143. The Taylor diagram provides a concise representation of three often employed metrics: the correlation coefficient, standard deviation, and RMSE 144. The plot consists of three axes: radial (correlation coefficient), angular (standard deviation), and concentric circles (RMSE) 143. In its standard configuration, the Taylor diagram displays the centred root mean square error (CRMSE) values 145.

The correlation coefficient (R) assesses the correlation between actual and predicted values and was computed using Eq. (33) 127. The value of R varies from -1 to + 1, with -1 specifying perfect inverse correlation and + 1 recommending perfect positive correlation 127. The R-value between 0 and 0.2 (or 0 and -0.2), 0.2 and 0.4 (-0.2 and -0.4), 0.4 and 0.6 (-0.4 and -0.6), 0.6 and 0.8 (-0.6 and -0.8), and 0.8 and 1 (-0.8 and -1) depicting very weak, weak, moderate, strong, and very strong correlations, respectively 127.

| 33 |

where = actual value, = predicted value, = mean, = mean, and n = sample size.

CRMSE will be computed by employing Eq. (34) 146. A model with the lowest CRMSE value will be better 147.

| 34 |

where = actual value, = observed value, = mean of actual values, and = mean of observed values.

Standard deviation (σ) computes the variability or dispersion of a dataset, compared to the mean value, and varies between 0 and ∞ 148. A high σ signifies that the observations deviate significantly from the mean, while a minimal σ suggests that they are closely packed around the mean 148. Standard deviation will be computed utilizing Eq. (35) 149.

| 35 |

where = sample value, = mean of sample values, and n = sample size.

Equation (36) 145 depicts the relationship between R, CRMSE, and σ. The geometric relationship between these three metrics highlights the performance of each model relative to a reference model, which can be depicted in the Taylor diagram 150. It is clear how the models and the reference model are spatially correlated when looking at a symbol’s azimuthal position in the Taylor diagram 150. The CRMSE is highlighted by the distance (along the concentric circle) each symbol has from the reference model 150. The symbol denoting the top-performing models will be placed closest to the reference point 150. The Taylor diagram was produced using MATLAB 2017b software.

| 36 |

where = CRMSE, = σ of observed values, = σ of simulated values, and = correlation coefficient.

Results

Feature selection

The multicollinearity test showed collinearity issues for the following predisposing factors: curvature, plan curvature, and profile curvature since the VIF values are above ten and TOL values are below 0.1 (Table 5). Hence, these three factors were excluded from the modelling. Among the other predisposing factors, lithology has the lowest VIF (1.104) and highest TOL (0.905) values, whereas soil clay content has the highest VIF (2.761) and lowest TOL (0.362) values.

Table 5.

Multicollinearity test results of the predisposing factors.

| Predisposing factors | VIF | TOL |

|---|---|---|

| Elevation | 2.424 | 0.412 |

| Aspect | 1.183 | 0.845 |

| Built-up area | 1.136 | 0.880 |

| Curvature | 42.569 | 0.023 |

| Fault | 1.140 | 0.877 |

| Geomorphic units | 1.625 | 0.615 |

| LULC | 1.167 | 0.856 |

| Lithology | 1.104 | 0.905 |

| Plan curvature | 17.828 | 0.056 |

| Profile curvature | 14.828 | 0.067 |

| Road | 1.149 | 0.870 |

| Slope | 2.334 | 0.428 |

| Soil texture | 1.476 | 0.677 |

| Soil bulk density | 2.649 | 0.377 |

| Soil clay content | 2.761 | 0.362 |

| Stream | 1.364 | 0.733 |

| TRI | 2.072 | 0.482 |

| TWI | 2.463 | 0.406 |

The information gain (IG) analysis led to the exclusion of another predisposing factor, namely the ‘built-up area’, which has an IG score of 0.035 (i.e., below the threshold of 0.05). IG metric defined that elevation (IG = 0.521), geomorphic units (IG = 0.480), slope (IG = 0.421), soil bulk density (IG = 0.356), and TWI (IG = 0.264) are the most important predisposing factors (Table 6). Factors such as distance from the road (0.065), distance from the faults (0.066), and soil clay content (0.099) have the lowest IG scores (i.e., below 0.1).

Table 6.

Information gain (IG) scores of the predisposing factors.

| Predisposing factors | IG values |

|---|---|

| Elevation | 0.521 |

| Aspect | 0.224 |

| Built-up area | 0.035 |

| Fault | 0.066 |

| Geomorphic units | 0.480 |

| LULC | 0.174 |

| Lithology | 0.157 |

| Road | 0.065 |

| Slope | 0.421 |

| Soil texture | 0.255 |

| Soil bulk density | 0.356 |

| Soil clay content | 0.099 |

| Stream | 0.133 |

| TRI | 0.159 |

| TWI | 0.264 |

After this double-step feature selection procedure, the 14 predisposing factors selected for the modelling are slope, elevation, aspect, terrain ruggedness index, topographic wetness index, distance from the stream channel, distance from the road, LULC, distance from the fault, soil texture, soil clay content, soil bulk density, lithology, and geomorphic units (see Supplementary Figure S1). The discarded factors are displayed in Supplementary Figure S2.

Landslide susceptibility maps

The landslide susceptibility maps created utilizing the six models are displayed in Fig. 4. The AUC scores affirmed that all the models are effective, with CatBoost, SVR, SVR-PSO, and SVR-GWO models having excellent performance (AUC score above 0.80). In contrast, CatBoost-PSO and CatBoost-GWO models have outstanding performance (AUC scores above 0.90), according to Hosmer and Lemeshow122. The AUC scores also ascertained that the CatBoost model is more effective than the SVR model. Also, integrating the optimization models improved the performance of both the CatBoost and SVR models (Table 7). Among the two optimization algorithms, GWO is slightly better than the PSO (Fig. 5). The MAE, MSE, RMSE, and R2 scores for both the training and validation datasets confirmed the above statement. (Tables 8 and 9).

Fig. 4.

Landslide susceptibility maps. Figure created with ArcGIS Pro software (Version 3.1; ESRI, Redlands, California, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

Table 7.

AUC scores of the models.

| Models | AUC | Standard error | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 0.899 | 0.00459 | 0.890 to 0.907 |

| CatBoost-PSO | 0.909 | 0.00432 | 0.900 to 0.917 |

| CatBoost-GWO | 0.910 | 0.00426 | 0.901 to 0.918 |

| SVR | 0.840 | 0.00606 | 0.829 to 0.851 |

| SVR-PSO | 0.858 | 0.00562 | 0.848 to 0.868 |

| SVR-GWO | 0.868 | 0.00541 | 0.858 to 0.878 |

Fig. 5.

ROC curve and AUC scores of the models.

Table 8.

Validation scores (training dataset).

| Models | MAE | MSE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 0.065 | 0.027 | 0.165 | 0.890 |

| CatBoost-PSO | 0.055 | 0.020 | 0.142 | 0.919 |

| CatBoost-GWO | 0.054 | 0.019 | 0.140 | 0.921 |

| SVR | 0.179 | 0.063 | 0.251 | 0.746 |

| SVR-PSO | 0.147 | 0.044 | 0.211 | 0.821 |

| SVR-GWO | 0.138 | 0.042 | 0.205 | 0.830 |

Table 9.

Validation scores (validation dataset).

| Models | MAE | MSE | RMSE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 0.071 | 0.032 | 0.180 | 0.869 |

| CatBoost-PSO | 0.066 | 0.029 | 0.171 | 0.881 |

| CatBoost-GWO | 0.065 | 0.029 | 0.170 | 0.883 |

| SVR | 0.181 | 0.063 | 0.252 | 0.745 |

| SVR-PSO | 0.154 | 0.050 | 0.224 | 0.798 |

| SVR-GWO | 0.146 | 0.047 | 0.219 | 0.808 |

According to the Friedman test, models are considered significantly different when the P-value < 0.05 and insignificantly different when the P-value > 0.05. Since the P-value is below 0.05 for all the models, the null hypothesis (i.e., all models provide similar results) can be rejected (Table 10). This implies a statistically significant difference in performance among the models. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied to assess the performance of paired models. In the case of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, a statistically significant difference between models exists when the z-statistic is between − 1.96 and + 1.96. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test shows that the CatBoost-PSO and CatBoost-GWO models do not exhibit a statistically significant difference (i.e., z-statistic = 1.017). However, all other model comparisons demonstrate significant differences (i.e., z-statistic > 1.96) (Table 11). A statistically significant difference between the results of the two models indicates that the observed difference in their performances is unlikely to result from random chance. In other words, it suggests that the models provide significantly different maps. From the Taylor diagram (Fig. 6), it is affirmed that the CatBoost-GWO model with a higher correlation coefficient and lower standard deviation scores has higher accuracy than other models.

Table 10.

Friedman test results.

| Models | Mean rank | Chi-square | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 3.43 | 61.31 | 0.0001 |

| CatBoost-PSO | 3.42 | ||

| CatBoost-GWO | 3.47 | ||

| SVR | 3.18 | ||

| SVR-PSO | 3.74 | ||

| SVR-GWO | 3.73 |

Table 11.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test results.

| Models | z-statistic | Significance level (α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|

| CatBoost ~ CatBoost-PSO | 6.04 | Yes |

| CatBoost ~ CatBoost-GWO | 6.39 | Yes |

| CatBoost ~ SVR | 14.40 | Yes |

| CatBoost ~ SVR-PSO | 10.51 | Yes |

| CatBoost ~ SVR-GWO | 8.74 | Yes |

| CatBoost-PSO ~ CatBoost-GWO | 1.017 | No |

| CatBoost-PSO ~ SVR | 17.17 | Yes |

|

CatBoost-PSO ~ SVR-PSO CatBoost-PSO ~ SVR-GWO |

13.17 12.12 |

Yes Yes |

|

CatBoost-GWO ~ SVR CatBoost-GWO ~ SVR-PSO CatBoost-GWO ~ SVR-GWO |

17.32 13.14 12.63 |

Yes Yes Yes |

|

SVR ~ SVR-PSO SVR ~ SVR-GWO SVR-PSO ~ SVR-GWO |

4.70 7.85 2.52 |

Yes Yes Yes |

Fig. 6.

The Taylor diagram.

Discussion

The two-stage feature selection approach discarded four predisposing factors (curvature, plan curvature, profile curvature, and built-up area). The exclusion of all curvature related parameters can have manifold reasons. Even if theoretically each curvature parameter provides unique information about terrain features, they are all sensitive to changes in terrain slope and shape and in areas with steep slopes or complex terrain features, curvature factors tend to be highly correlated due to their shared sensitivity to terrain morphology151. Moreover, the spatial resolution of the DEM used to compute the curvature factors probably influences their effectiveness as explanatory variables. This can be ascertained from the study by Catani et al.29, where the curvature factors are found to be weak predictors when the spatial resolution is 10 m, which is close to the 12.5 m resolution considered in this study. It should also be considered that curvature is commonly linked to hydrological processes, surface and subsurface water distribution and soil moisture29,152. In the study area, and at this spatial resolution of the DEM, other factors may better describe similar processes, such as the TWI or the distance from the streams. Also, the effect of thick vegetative cover may overshadow the influence of curvature on landslide occurrence, especially in areas with dense vegetation, like the WG region in Kerala.

Discarding the built-up area by the second step of the feature selection process may be misleading, as this factor is commonly strongly related to the occurrence of landslides and higher landslide hazard levels83,153–155. The outcomes of the feature selection are not intended to deny this relationship; on the contrary, we acknowledge a relevant connection between landslide locations and road network and LULC (which identifies among its classes also urbanized areas). Our interpretation is that built-up area is identified as an uninfluential predisposing factor because LULC (including urbanized areas) and road networks are already included in the optimal feature ensemble and already describe the effect of the urban environment on landslide activation without the need to account for a third factor.

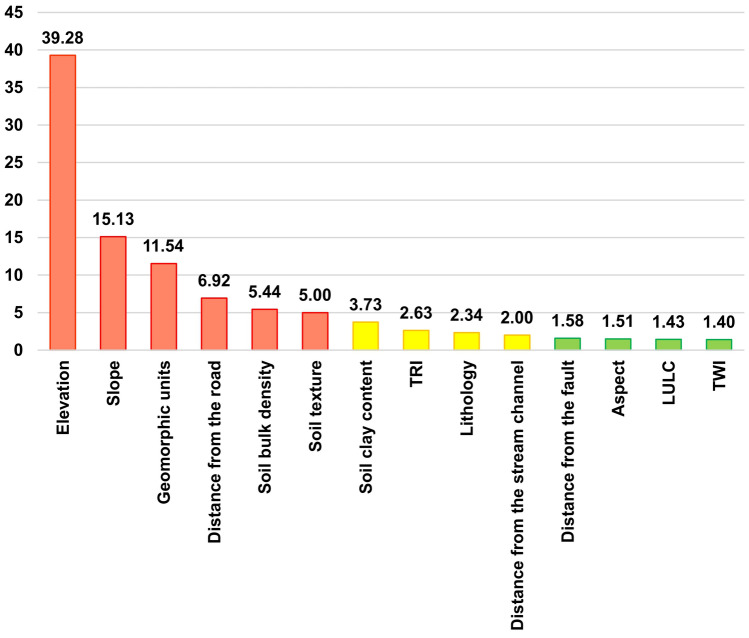

Predisposing factors such as elevation, slope, geomorphic units, distance from the road, soil bulk density, and soil texture have higher (scores ≥ 5.00) importance, whereas soil clay content, TRI, lithology, and distance from the stream channel have moderate (scores ≥ 2.00) importance (Fig. 7). Factors such as distance from the fault, aspect, LULC, and TWI have lower (scores < 2.00) importance. Elevation (39.28), slope (15.13), geomorphic units (11.54), distance from the road (6.92), and soil bulk density (5.44) are the top five important predisposing factors. On the other hand, predisposing factors such as TWI (1.40), LULC (1.43), aspect (1.51), and distance from the fault (1.58) are the least important. Previous landslide susceptibility studies conducted in different areas in the WG region by Abraham et al.67 found slope, rainfall, elevation, distance from the road, and TWI as the top five important factors, while Jennifer156 identified rainfall, elevation, slope, displacement, and distance from the road as the top five factors. Similar to the findings of this modelling, factors such as slope, elevation, and distance from the road are also included in the list of the top five factors of these previous studies.

Fig. 7.

Importance of predisposing factors.

The higher influence of elevation can be attributed to higher precipitation and resulting soil moisture in the WG region. The WG is one of the rainiest regions in the tropics and receives heavy rainfall with a seasonal mean of more than 25 mm/day157,158. The studies by Abraham et al.159 and Yunus et al.160 reported the short-duration, intense rainfall in the highly elevated terrain of the WG as one of the predominant causes of landslide initiation. The high ranges of Kerala have a slope as steep as 83.24°, and this is the most important landslide predisposing factor161–163 because a less intense hydrological trigger is required at steeper slopes to trigger landslides 164. The landslides in the study area are predominant in the geomorphic units such as denudational hills and valleys and structural hills and valleys. Denudational hills and valleys result from weathering and erosional processes, whereas structural hills and valleys are the combined effect of denudation and tectonism165. Gneiss and charnockite are the predominant rock types in these areas. Though these are Precambrian crystalline rocks, the extent of chemical weathering and erosional processes and the presence of fractures and joints can facilitate landslides68,166. Moreover, a significant level of chemical weathering has been reported in these rock types due to high temperature and abundant rainfall, resulting in thick soil covers, a widely consolidated predisposing factor for shallow landslides7,75,167.

Both the construction of roads by cutting the mountain slopes and the widening of existing roads can affect the stability of the slopes. Yunus et al.160 reported cutting mountain slopes for road construction as one of the major causes of sliding in the WG region. The importance of road networks is in contrast with other studies83. However, it is supported by the studies of Ajin et al.68, Anchima et al.168, and Thomas et al.169 in different parts of the WG region in Kerala, which reported road cuttings as one of the crucial landslide inducing factors. The lack of drainage facilities along the mountain roads intensifies the slope failure in the WG region of Kerala68. Kanungo et al.7 reported that unscientific road construction, i.e., unprotected road cuttings and roads without drainage channels to divert excess water, is common in the WG region of Kerala. Soil bulk density indicates soil compaction and negatively correlates with landslide susceptibility91. This is because soil bulk density is roughly inversely proportional to soil moisture, porosity, and hydraulic conductivity170,171. A major portion of the WG region in Kerala is dominated by clayey soil. However, the soil bulk density varies along the clayey soil. This can be attributed to land use practices and the extent of chemical weathering. In the study area, the landslide incidences are concentrated in the WG region, which has a comparatively lower soil bulk density. Clay is the dominant soil type in the high ranges of Kerala. The lateritic soil in the WG region, which is rich in clay content, will retain water and enhance pore water pressure 7. Sajinkumar et al.75 reported a significant association between laterite soil and landslide occurrences in the WG. Also, clay acts as a potential slip zone, resulting in landslides172,173. Therefore, regions with higher clay content are more susceptible to slope failures. The high ranges of Kerala are rugged. Ruggedness implies the variation of slope and the undulation of relief174. The probability of sliding is high in rugged terrain since the shear stress will be greater than a smoother surface. Toe cutting (erosion) by streams and subsequent slope failures is common in the WG region of Kerala during the monsoon season7. All 44 major rivers in Kerala originate from the WG region, and the perennial streams with high erosive power are one of the prime factors for landslide initiation in the WG region160. Faults have a lesser importance since this predisposing factor does not play a relevant role in the case of rainfall-induced landslides. Aspect influences moisture retention and vegetative cover; however, this factor has a lesser influence due to the thick vegetative cover in the WG region. LULC is also less important since the incidences are more in vegetated areas. The study conducted by Hao et al.175 in the WG region of Kerala also reported that more than 50% of landslides happened in densely vegetated terrain, and, thus, LULC had a lesser influence on the landslides reported in 2018. TWI has the least importance since the wetness is focused on the study area’s lower portion; hence, the impact on the highly elevated WG region is negligible.

This study affirmed that the CatBoost regression algorithm is superior to the SVR algorithm in identifying the landslide susceptibility of the terrain. The AUC score of the CatBoost model is 0.059 more than that of the SVR model, whereas MAE, MSE, and RMSE scores (validation dataset) are respectively 0.110, 0.031, and 0.072 less, and R2 score (validation dataset) is 0.124 higher than the SVR model. This is because CatBoost is an ensemble model integrated with a boosting algorithm, which will reduce bias and variance and thereby enhance performance. The studies by Gupta et al.176 and Li et al.177 also ascertained that the CatBoost model is more effective than the SVR model. This modelling underlined that the integration of optimization algorithms improved the performance of both ML regression models, and among the two optimization algorithms, GWO is more efficient. In the case of optimization algorithms, the integration of the PSO algorithm improved the AUC score of the SVR model from 0.840 to 0.858 (a 0.018 increase) and the AUC score of the CatBoost model from 0.899 to 0.909 (a 0.010 increase). For the GWO algorithm, there is an increase of 0.028 for the SVR model and 0.011 for the CatBoost model. Jia et al.178 also found GWO to be the better algorithm when compared to the PSO algorithm. This results from the fact that the GWO algorithm has better exploration and exploitation performance, convergence performance, and optimization accuracy than the PSO algorithm179,180. However, it is important to stress that this study shows that an optimization algorithm cannot enhance the performance of a low-performing model to the level of a high-performance model. Indeed, in our study, the optimized SVR still had worse validation scores than the unoptimized CatBoost, demonstrating that selecting a good modelling algorithm and designing a proper model implementation scheme is paramount in guiding good susceptibility assessment. However, optimization algorithms can undoubtedly help to refine the results.

To thoroughly compare the results of the models, we followed the procedure proposed by Xiao et al.181, which includes the subtraction of the susceptibility raster values obtained by the different models from a benchmark susceptibility map (the one defined by the model with the highest AUC metric) and inspecting the factor classes responsible for the overestimation and underestimation. The CatBoost-GWO, being the model with the highest AUC metric, is the benchmark model. Hence, the susceptibility raster layers of the other five models were subtracted from the CatBoost-GWO model susceptibility raster layer. The differences in the mapped susceptibility values were contained in the case of CatBoost-GWO and CatBoost-PSO (-0.12 to 0.12) and higher for the other pairs of maps: CatBoost-GWO – CatBoost (-0.35 to 0.35), CatBoost-GWO – SVR-GWO (-0.43 to 0.45), CatBoost-GWO – SVR-PSO (-0.41 to 0.48), and CatBoost-GWO – SVR (-0.38 to 0.77) (Fig. 8). The mean value of the “difference maps” (Fig. 8) was calculated to assess if, in some cases, an overestimation or an underestimation systematically prevails. From Fig. 8, it is affirmed that the difference is larger for the CatBoost-GWO – SVR map, while the difference is smaller for the CatBoost-GWO – CatBoost-PSO, which agrees well with the AUC scores and proves that optimization algorithms can help the models converge towards optimal results.

Fig. 8.

The comparison maps (with uniform legend ranging from -1 to + 1). Figure created with ArcGIS Pro software (Version 3.1; ESRI, Redlands, California, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

Finally, it is important to discuss the main limitations of the present work. It is widely acknowledged that the performance of ML algorithms depends on the quantity and quality of data182,183. Therefore, our susceptibility assessment can be ameliorated by improving the training and validation dataset (e.g., by timely updates or surveys with different techniques). The inventory of GSI used in this study was often generated by surveying the landslides that damaged roads, buildings, and other infrastructure21. Hence, many landslides in remote and rugged terrain may have gone unnoticed. The inventory for 2018 created by Hao et al.21 was verified by employing satellite images and field surveys. Hence, detailed verification of the GSIs landslide inventory with remote sensing techniques will help to derive accurate inventories with a high degree of completeness, at least concerning the landslides large and recent enough to be still distinguishable despite vegetation growth, human intervention on the hillsides and geomorphic process that could conceal the landslide morphology.

Another limitation of the study is the combined use of a landslide inventory with a point-like geometry (a point represents each landslide) and a pixel-based approach for the susceptibility assessment. In this case, the approximation of the landslide location could lead to approximations in sampling predisposing factors over a not-very-representative pixel. Ultimately, that could bring uncertainties and errors in the results. For this reason, further research developments in this study area could consider a slope unit-based approach, which may yield better results when working with point-geometry landslide inventories162,184.

Conclusion

This study identified the WG region of Kerala (India) as a test site to perform a landslide susceptibility assessment testing two novel ML algorithms (CatBoost and SVR) and the integration of two optimization algorithms. A multi-stage feature selection procedure identified the most important predisposing factors: elevation, slope, geomorphic units, distance from the road, and soil bulk density, whereas TWI, LULC, aspect, and distance from the fault had lesser importance. Concerning the susceptibility maps, the study found that CatBoost and SVR alone can provide good results (with the former outperforming the latter). However, the integration of optimization algorithms such as PSO and GWO improved the overall results of the ML algorithms, with GWO having slightly higher performance. Among the six models, CatBoost-GWO had the best performance as defined by several validation metrics, including an AUC score equal to 0.910. It is important to note that optimized SVR models did not outperform non-optimized CatBoost. This study ascertained the relevance of optimization algorithms in enhancing the performance of ML algorithms and producing better susceptibility maps; however, at the same time, the study pointed out that the role of optimization algorithms is refining the results, helping the original model to converge towards optimal predictions; it cannot radically change the predictions of a low-performing model, thus highlighting the importance of setting up a rigorous susceptibility model since the early steps of any research. From a practical standpoint, this work proposes an updated and cutting-edge susceptibility for an Indian state that, despite being very prone to landslides, is covered only by a former work dating back to 2010. The study output will aid the decision-makers in Kerala and other regions with similar geo-environmental conditions in land-use planning, infrastructure development, emergency response planning, community resilience building, insurance and risk management, and long-term planning and adaptation. In light of climate change’s impact on precipitation patterns and extreme weather events, landslide susceptibility studies are essential for informing long-term planning and adaptation strategies, especially in the Global South countries where the impacts are expected to be particularly severe. By integrating landslide susceptibility information into various planning and management initiatives, disaster managers can effectively mitigate the detrimental impacts of landslides and safeguard the well-being of individuals, assets, and the environment.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (PDF 1194.8 kb)

Author contributions

RSA performed the analysis and prepared Figs. 1–8 and supplementary data, RSA and SS wrote the manuscript, SS and RF revised the manuscript, and SS and RF supervised the study.

Funding

This study was carried out within the RETURN Extended Partnership and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (National Recovery and Resilience Plan - NRRP, Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.3 - D.D. 1243 2/8/2022, PE0000005).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-72663-x.

References

- 1.Donnini, M. et al. Landslides triggered by an extraordinary rainfall event in Central Italy on September 15, 2022. Landslides20, 2199–2211 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martha, T. R. et al. Landslides triggered by the June 2013 extreme rainfall event in parts of Uttarakhand state, India. Landslides12, 135–146 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausilio, E., Silvestri, F., Tropeano, G. & Zimmaro, P. Landslides triggered by recent earthquakes in Italy. in Coseismic Landslides (eds. Towhata, I., Wang, G., Xu, Q. & Massey, C.) 263–302 (Springer Nature Singapore, 2022). 10.1007/978-981-19-6597-5_10.

- 4.Tiwari, B. & Ajmera, B. Landslides triggered by earthquakes from 1920 to 2015. in Advancing Culture of Living with Landslides (eds. Mikos, M., Tiwari, B., Yin, Y. & Sassa, K.) 5–15 (Springer International Publishing, 2017). 10.1007/978-3-319-53498-5_2.

- 5.Marui, H. & Nadim, F. Landslides and multi-hazards. in Landslides – Disaster Risk Reduction (eds. Sassa, K. & Canuti, P.) 435–450 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2009). 10.1007/978-3-540-69970-5_23.

- 6.Panda, S. D. et al. Effect of groundwater table fluctuation on slope instability: a comprehensive 3D simulation approach for Kotropi landslide, India. Landslides20, 663–682 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanungo, D. P., Singh, R. & Dash, R. K. Field observations and lessons learnt from the 2018 landslide disasters in Idukki district, Kerala, India. Curr. Sci.119(11), 1797–1806 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia, Z., Motagh, M., Li, T. & Roessner, S. The June 2020 Aniangzhai landslide in Sichuan Province, Southwest China: slope instability analysis from radar and optical satellite remote sensing data. Landslides19, 313–329 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkash, S. Lessons learned from landslides of socio-economic and environmental significance in India. in Progress in Landslide Research and Technology, Volume 1 Issue 2, 2022 (eds. Alcántara-Ayala, I. et al.) 309–315 (Springer International Publishing, 2023). 10.1007/978-3-031-18471-0_23.

- 10.Gatto, A., Clò, S., Martellozzo, F. & Segoni, S. Tracking a decade of hydrogeological emergencies in Italian municipalities. Data8, 151 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segoni, S., Barbadori, F., Gatto, A. & Casagli, N. Application of empirical approaches for fast landslide hazard management: The case study of Theilly (Italy). Water14, 3485 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachri, S. et al. Mapping landform and landslide susceptibility using remote sensing, GIS and field observation in the Southern Cross Road, Malang Regency, East Java, Indonesia. Geosciences11, 4 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahal, B. K. & Dahal, R. K. Landslide hazard map: tool for optimization of low-cost mitigation. Geoenviron. Disasters4, 8 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Froude, M. J. & Petley, D. N. Global fatal landslide occurrence from 2004 to 2016. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci.18, 2161–2181 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gómez, D., García, E. F. & Aristizábal, E. Spatial and temporal landslide distributions using global and open landslide databases. Nat. Hazards117, 25–55 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, X., Wang, Y., Lin, Q. & Yang, X. Assessing global landslide casualty risk under moderate climate change based on multiple GCM projections. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci.14, 751–767 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma, V. K. Landslides in India: Issues and perspective. J. Geol. Soc. India95, 110–110 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 18.NDMA. National Landslide Risk Management Strategy (National Disaster Management Authority, Government of India, 2019).

- 19.Biswas, A. & Praveen Karanth, K. Role of geographical gaps in the Western Ghats in shaping intra- and interspecific genetic diversity. J. Indian Inst. Sci.101, 151–164 (2021).

- 20.Kasturirangan, K. & Babu, C. R. Western Ghats—Broad contours of the study and outcomes. in Space and Beyond (ed. Suresh, B. N.) 343–350 (Springer Singapore, 2021). 10.1007/978-981-33-6510-0_17.

- 21.Hao, L. et al.s> Constructing a complete landslide inventory dataset for the 2018 monsoon disaster in Kerala, India, for land use change analysis. Earth Syst. Sci. Data12, 2899–2918 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brabb, E. E. Innovative approaches to landslide hazard and risk mapping. in Proceedings of the 4th International Conference and Field Workshop on Landslides, 17–22. (Japan Landslide Society, 1985). 10.1016/0148-9062(87)91363-5

- 23.Corominas, J. et al.s> Recommendations for the quantitative analysis of landslide risk. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ.73, 209–263 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ado, M. et al. Landslide susceptibility mapping using machine learning: A literature survey. Remote Sens.14, 3029 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang, Y. & Zhao, L. Review on landslide susceptibility mapping using support vector machines. CATENA165, 520–529 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lima, P., Steger, S., Glade, T. & Murillo-García, F. G. Literature review and bibliometric analysis on data-driven assessment of landslide susceptibility. J. Mt. Sci.19, 1670–1698 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merghadi, A. et al. Machine learning methods for landslide susceptibility studies: A comparative overview of algorithm performance. Earth-Sci. Rev.207, 103225 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichenbach, P., Rossi, M., Malamud, B. D., Mihir, M. & Guzzetti, F. A review of statistically-based landslide susceptibility models. Earth-Sci. Rev.180, 60–91 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catani, F., Lagomarsino, D., Segoni, S. & Tofani, V. Landslide susceptibility estimation by random forests technique: sensitivity and scaling issues. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci.13, 2815–2831 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segoni, S. et al. New explanatory variables to improve landslide susceptibility mapping: testing the effectiveness of soil sealing information and multi-criteria geological parametrization. Ital. J. Eng. Geol. Environ. 209–220 (2021) 10.4408/IJEGE.2021-01.S-19.

- 31.Lee, S., Hong, S.-M. & Jung, H.-S. A support vector machine for landslide susceptibility mapping in Gangwon Province, Korea. Sustainability9, 48 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nefeslioglu, H. A., Sezer, E., Gokceoglu, C., Bozkir, A. S. & Duman, T. Y. Assessment of landslide susceptibility by decision trees in the metropolitan area of Istanbul, Turkey. Math. Probl. Eng.2010, 1–15 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, S., Lee, M.-J., Jung, H.-S. & Lee, S. Landslide susceptibility mapping using Naïve Bayes and Bayesian network models in Umyeonsan, Korea. Geocarto Int.35, 1665–1679 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adnan, M. S. G. et al. Improving spatial agreement in machine learning-based landslide susceptibility mapping. Remote Sens.12, 3347 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahin, E. K. Comparative analysis of gradient boosting algorithms for landslide susceptibility mapping. Geocarto Int.37, 2441–2465 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panahi, M., Gayen, A., Pourghasemi, H. R., Rezaie, F. & Lee, S. Spatial prediction of landslide susceptibility using hybrid support vector regression (SVR) and the adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) with various metaheuristic algorithms. Sci. Total Environ.741, 139937 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yimin, M. et al. Innovative landslide susceptibility mapping portrayed by CA-AQD and K-Means clustering algorithms. Adv. Civ. Eng.2021, 1–17 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng, T., Chen, Y. & Chen, W. Landslide susceptibility modeling using remote sensing data and Random SubSpace-based functional tree classifier. Remote Sens.14, 4803 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azarafza, M., Azarafza, M., Akgün, H., Atkinson, P. M. & Derakhshani, R. Deep learning-based landslide susceptibility mapping. Sci. Rep.11, 24112 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nanehkaran, Y. A. et al. Riverside landslide susceptibility overview: Leveraging artificial neural networks and machine learning in accordance with the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals. Water15, 2707 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nikoobakht, S., Azarafza, M., Akgün, H. & Derakhshani, R. Landslide susceptibility assessment by using convolutional neural network. Appl. Sci.12, 5992 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sevgen, Kocaman, Nefeslioglu & Gokceoglu. A novel performance assessment approach using photogrammetric techniques for landslide susceptibility mapping with logistic regression, ANN and random forest. Sensors19, 3940 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Awad, M. & Khanna, R. Support vector regression. in Efficient Learning Machines 67–80 (Apress, 2015). 10.1007/978-1-4302-5990-9_4.

- 44.Ahn, J. M., Kim, J. & Kim, K. Ensemble machine learning of Gradient Boosting (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) and attention-based CNN-LSTM for harmful algal blooms forecasting. Toxins15, 608 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanamori, T., Hatano, K. & Watanabe, O. Boosting. in Computer Vision 1–7 (Springer International Publishing, 2020). 10.1007/978-3-030-03243-2_836-1.

- 46.Schapire, R. E. The boosting approach to machine learning: an overview. in Nonlinear Estimation and Classification (eds. Denison, D. D., Hansen, M. H., Holmes, C. C., Mallick, B. & Yu, B.) vol. 171 149–171 (Springer New York, 2003).

- 47.Hancock, J. T. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. CatBoost for big data: an interdisciplinary review. J. Big Data7, 94 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou, F., Fan, H., Liu, Y., Zhang, H. & Ji, R. Hybrid model of machine learning method and empirical method for rate of penetration prediction based on data similarity. Appl. Sci.13, 5870 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elgeldawi, E., Sayed, A., Galal, A. R. & Zaki, A. M. Hyperparameter tuning for machine learning algorithms used for arabic sentiment analysis. Informatics8, 79 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, J. et al. Hyperparameter optimization for machine learning models based on bayesian optimization. J. Electron. Sci. Technol. (2019).

- 51.Daviran, M., Shamekhi, M., Ghezelbash, R. & Maghsoudi, A. Landslide susceptibility prediction using artificial neural networks, SVMs and random forest: hyperparameters tuning by genetic optimization algorithm. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol.20, 259–276 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hassan, E., Shams, M. Y., Hikal, N. A. & Elmougy, S. The effect of choosing optimizer algorithms to improve computer vision tasks: a comparative study. Multimed. Tools Appl.82, 16591–16633 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kavzoglu, T. & Teke, A. Advanced hyperparameter optimization for improved spatial prediction of shallow landslides using extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost). Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ.81, 201 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw.69, 46–61 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rezaei, F. et al. Diversity-based evolutionary population dynamics: a new operator for grey wolf optimizer. Processes10, 2615 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Balogun, A.-L. et al. Spatial prediction of landslide susceptibility in western Serbia using hybrid support vector regression (SVR) with GWO, BAT and COA algorithms. Geosci. Front.12, 101104 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tien Bui, D. et al. New Hybrids of ANFIS with several optimization algorithms for flood susceptibility modeling. Water10, 1210 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saha, S. et al. Integrating the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with machine learning methods for improving the accuracy of the landslide susceptibility model. Earth Sci. Inform.15, 2637–2662 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen, W., Chen, X., Peng, J., Panahi, M. & Lee, S. Landslide susceptibility modeling based on ANFIS with teaching-learning-based optimization and Satin bowerbird optimizer. Geosci. Front.12, 93–107 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen, W. et al. Spatial prediction of landslide susceptibility using GIS-based data mining techniques of ANFIS with whale optimization algorithm (WOA) and grey wolf optimizer (GWO). Appl. Sci.9, 3755 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rajwar, K. & Deep, K. Uncovering structural bias in population-based optimization algorithms: A theoretical and simulation-based analysis of the Generalized Signature Test. Expert Syst. Appl.240, 122332 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen, T.-Y. & Chi, T.-M. On the improvements of the particle swarm optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw.41, 229–239 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang, J., Zhai, Y., Han, Z. & Lu, J. Improved particle swarm optimization based on entropy and its application in implicit generalized predictive control. Entropy24, 48 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ghalambaz, M., Jalilzadeh Yengejeh, R. & Davami, A. H. Building energy optimization using Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO). Case Stud. Therm. Eng.27, 101250 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yan, F., Xu, J. & Yun, K. Dynamically dimensioned search grey wolf optimizer based on positional interaction information. Complexity2019, 1–36 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abraham, M. T., Satyam, N., Lokesh, R., Pradhan, B. & Alamri, A. Factors affecting landslide susceptibility mapping: Assessing the influence of different machine learning approaches, sampling strategies and data splitting. Land10, 989 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abraham, M. T., Satyam, N., Jain, P., Pradhan, B. & Alamri, A. Effect of spatial resolution and data splitting on landslide susceptibility mapping using different machine learning algorithms. Geomat. Nat. Haz. Risk12, 3381–3408 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ajin, R. S. et al. Enhancing the accuracy of the REPTree by integrating the hybrid ensemble meta-classifiers for modelling the landslide susceptibility of Idukki district, South-western India. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens.50, 2245–2265 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jacinth Jennifer, J. & Saravanan, S. Artificial neural network and sensitivity analysis in the landslide susceptibility mapping of Idukki district, India. Geocarto Int.37, 5693–5715 (2022).

- 70.Jones, S., Kasthurba, A. K., Bhagyanathan, A. & Binoy, B. V. Landslide susceptibility investigation for Idukki district of Kerala using regression analysis and machine learning. Arab. J. Geosci.14, 838 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shameem Ansar A., Sudha, S. & Francis, S. Identification and classification of landslide susceptible zone using geospatial techniques and machine learning models. Geocarto Int.37, 18328–18355 (2022).

- 72.KSDMA. Hazard maps. Kerala State Disaster Management Authority (KSDMA) websitehttps://sdma.kerala.gov.in/hazard-maps/ (2010).

- 73.Ramasamy, S. M. et al. Geomorphology and landslide proneness of Kerala, India A geospatial study. Landslides18, 1245–1258 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hunt, K. M. R. & Menon, A. The 2018 Kerala floods: a climate change perspective. Clim. Dyn.54, 2433–2446 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sajinkumar, K. S., Anbazhagan, S., Pradeepkumar, A. P. & Rani, V. R. Weathering and landslide occurrences in parts of Western Ghats, Kerala. J. Geol. Soc. India78, 249–257 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Naidu, S. et al. Early warning system for shallow landslides using rainfall threshold and slope stability analysis. Geosci. Front.9, 1871–1882 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vasudevan, N., Ramanathan, K. & Syali, T. S. Land degradation in the Western Ghats: The case of the Kavalappara landslide in Kerala, India. in Environmental Restoration (eds. Ashish, D. K. & De Brito, J.) vol. 232 199–207 (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

- 78.Sajinkumar, K. S. & Oommen, T. Landslide atlas of Kerala. Geological Society of India, pp. 34 (2021).

- 79.Ajin, R. S. et al. The tale of three landslides in the Western Ghats, India: lessons to be learnt. Geoenviron. Disasters9, 16 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 80.George, K. A., Sunil, P. S., Anish, A. U., Gopinath, G. & Mini, V. K. A pilot assessment of the fatal landslide on 29 August 2022 in Kudayathoor, Idukki, Kerala. J. Geol. Soc. India99, 141–144 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Martha, T. R., Roy, P., Khanna, K., Mrinalni, K. & Vinod Kumar, K. Landslides mapped using satellite data in the Western Ghats of India after excess rainfall during August 2018. Curr. Sci.117(5), 804–812 (2019).

- 82.Martha, T. R., Kerle, N., van Westen, C. J., Jetten, V. & Kumar, K. V. Segment optimization and data-driven thresholding for knowledge-based landslide detection by object-based image analysis. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens.49, 4928–4943 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Luti, T., Segoni, S., Catani, F., Munafò, M. & Casagli, N. Integration of remotely sensed soil sealing data in landslide susceptibility mapping. Remote Sens.12, 1486 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nguyen, Q. H. et al. Influence of data splitting on performance of machine learning models in prediction of shear strength of soil. Math. Probl. Eng.2021, e4832864 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nurwatik, N., Ummah, M. H., Cahyono, A. B., Darminto, M. R. & Hong, J.-H. A comparison study of landslide susceptibility spatial modeling using machine learning. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf.11, 602 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guo, Z., Tian, B., Zhu, Y., He, J. & Zhang, T. How do the landslide and non-landslide sampling strategies impact landslide susceptibility assessment? — A catchment-scale case study from China. J. Rock Mech. and Geotech. Eng.16, 877–894 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Babitha, B. G. et al. A framework employing the AHP and FR methods to assess the landslide susceptibility of the Western Ghats region in Kollam district. Saf. Extreme Environ.4, 171–191 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bhagya, S. B. et al. Landslide susceptibility assessment of a part of the Western Ghats (India) employing the AHP and F-AHP models and comparison with existing susceptibility maps. Land12, 468 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meena, S. R., Puliero, S., Bhuyan, K., Floris, M. & Catani, F. Assessing the importance of conditioning factor selection in landslide susceptibility for the province of Belluno (region of Veneto, northeastern Italy). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci.22, 1395–1417 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Puente-Sotomayor, F., Mustafa, A. & Teller, J. Landslide susceptibility mapping of urban areas: Logistic Regression and sensitivity analysis applied to Quito, Ecuador. Geoenviron. Disasters8, 19 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 91.Temme, A. J. A. M. Relations between soil development and landslides. in Geophysical Monograph Series (eds. Hunt, A., Egli, M. & Faybishenko, B.) 177–185 (Wiley, 2021). 10.1002/9781119563952.ch9.

- 92.Riley, S. J., DeGloria, S. D. & Elliot, R. A terrain ruggedness index that quantifies topographic heterogeneity. Intermountain J. Sci.5(1–4), 23–27 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 93.Beven, K. J. & Kirkby, M. J. A physically based, variable contributing area model of basin hydrology. Hydrol. Sci. Bull.24, 43–69 (1979). [Google Scholar]