Abstract

Moral injury has emerged as a construct of interest in healthcare workers’ (HCW) occupational stress and health. We conducted one of the first multidisciplinary, longitudinal studies evaluating the relationship between exposure to potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs), burnout, and turnover intentions. HCWs (N = 473) completed surveys in May of 2020 (T1) and again in May of 2021 (T2). Generalized Linear Models (robust Poisson regression) were used to test relative risk of turnover intentions, and burnout at T2 associated with PMIE exposure, controlling for T1 covariates. At T1, 17.67% reported they had participated in a PMIE, 41.44% reported they witnessed a PMIE and 76.61% reported feeling betrayed by healthcare or a public health organization. In models including all T1 PMIE exposures and covariates, T2 turnover intentions were increased for those who witnessed a PMIE at T1 (Relative Risk [RR] = 1.66, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 1.17–2.34) but not those that participated or felt betrayed. T2 burnout was increased for those who participated in PMIE at T1 (RR = 1.38, 95%CI 1.03–1.85) but not those that witnessed or felt betrayed. PMIE exposure is highly prevalent among HCWs, with specific PMIEs associated with turnover intentions and burnout. Organizational interventions to reduce and facilitate recovery from moral injury should account for differences in the type of PMIE exposures that occur in healthcare work environments.

Keywords: Moral injury, Moral distress, Healthcare workers, Occupational health, Turnover, Burnout, Value congruence

Subject terms: Occupational health, Risk factors, Health policy

Introduction

The National Academy of Medicine published a landmark report in 2019 on clinician burnout and well-being, citing serious problems connected to workforce shortages, quality care, and adverse impacts on training and recruitment1. Recommended actions focused on systems approaches (changing healthcare settings, education environments, and policy/regulation) that have been largely lost to the pandemic crucible. Only five years since its publication, health systems in the United States face worse workforce shortages, more burnout, and higher risk of care systems collapsing, all of which will take years to resolve2–4.

Burnout and turnover have been widely studied, with predictors most strongly related to systemic problems involving workplace environments, administrative burden, high workload, and reduced staffing1. Though many components of burnout are driven by environmental factors, to date most healthcare systems have largely focused intervention resources on resilience for individual healthcare workers (HCW) rather than the necessary system-level change1,2. This is despite evidence that the majority of HCWs lack interest in individually-focused well-being and resilience programs, and that they are not experiencing a deficit of personal resilience2,4,5. Conversely, HCWs endorse systemic factors likely to more closely map to improved retention and burnout. For example, 52% of HCWs endorse a goal for flexible schedules, 51% for increased wages, and (most pertinent to the current paper) 37% endorse wanting alignment of personal and organizational values2. In a recent national study in the United States of 21,000 nurses and physicians, management interventions to improve care delivery were identified as more vital for improving mental health than programming that seeks to directly target mental health6.

Multiple system factors must be addressed to reduce occupational distress in HCWs including attention to workload, teamwork, leader behavior, value alignment, and electronic health record/technology characteristics. Moral distress and moral injury created by events in the work environment are an additional factor that contributes to HCW distress, with more than 56 editorial articles within the past 3 years in the literature7. Despite the relative novelty of this variable in healthcare, a promising metric appears to be potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs). PMIEs are defined as specific experiences where individuals; (1) participate in something that transgresses their own beliefs because of what they personally did or failed to do, (2) perceive another persons’ behavior as a moral violation, or (3) experience actions from leaders as a betrayal of what is right in a high stakes situation (e.g. covering up a safety issue)8,9.

The contextual features of the pandemic brought PMIE exposures to the forefront as a signature HCW experience10–12. For example, throughout the pandemic, HCWs experienced PMIEs when they delivered care that was at least partially determined by something other than a patient’s medical needs (e.g., financial considerations, supply and staffing shortages, infection control protocol) that contradict HCWs’ commitment to optimize outcomes for patients13. Table 1 gives a range of examples of HCWs PMIEs.

Table 1.

Moral injury factors/types, and examples of experiences by frontline healthcare workers and leaders.

| Type of PMIE | As experienced by HCWs | As experienced by leadership |

|---|---|---|

| Personally participating (self-injury) |

Incorrectly assessing a clinical issue Not getting key clinical notes done in time Being required to provide futile care that causes pain |

Underestimating needed staff or supplies Missing organizational requirements for accreditation Assigning unrealistic workloads to compensate for staffing shortages |

| Witnessing |

Observing others withhold needed care Experiencing value discrepancies between personal/professional values and organizational values Patients unable to obtain needed care due to lack of resources or bureaucratic obstacles |

Impossible to secure needed supplies to do supply chain problems Trying to collaborate with other administrators to solve problems, but being left out of key communication necessary to meet needs Patients unable to obtain needed care due to lack of resources or bureaucratic obstacles |

| Betrayal |

Assigned too many patients to be able to provide adequate care Caring for patients without appropriate supply of PPE Colleagues abusing sick time to the point that care is compromised Health systems that tolerate HCW mistreatment by patients/visitors Work rules about breaks, workload, overtime not adhered to Health systems and/or insurers pursing monopolistic behavior that compromises staffing and patient care Politicization/misinformation about medical care by elected leaders |

Higher organizational levels prevent access to staffing or other resources necessary to provide safe care Being asked to cover up rather than address patient safety concerns Health systems and/or insurers pursing monopolistic behavior that compromises patient care Politicization/misinformation about medical care by elected leaders |

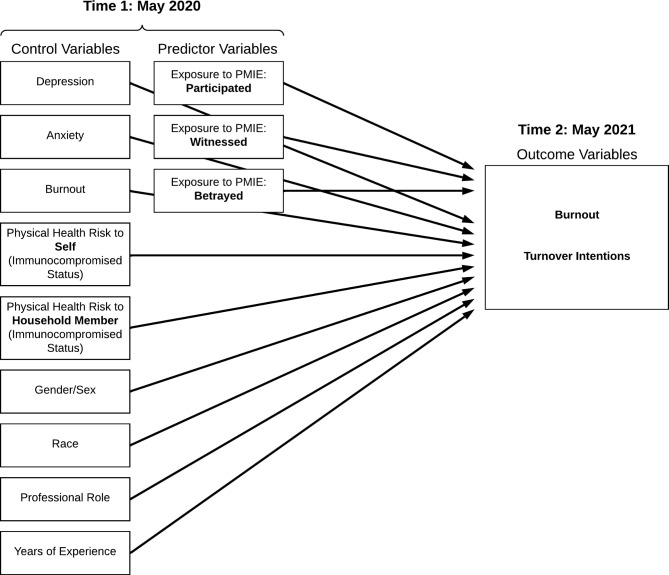

Experiences that are incongruent with one’s moral values are common in healthcare, as estimates show that 20–50% of HCWs report PMIE exposure14. PMIEs are also impactful, as about half of those exposed develop levels of distress that significantly erode psychiatric, psychosocial, and occupational health15. Preliminary studies associate greater PMIE exposure with greater risk for mental health disorders16,17, greater job dissatisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention18–23. The generalizability of the existing data connecting PMIEs to behavioral and economic consequences (e.g., burnout, turnover, cost of retraining new staff, cost of traveling nurses) is limited by methodology, including non-causal cross-sectional designs and lack of robust controls for known associates of moral injury and occupational dysfunction, such as HCWs’ mental health (e.g., anxiety, depression)24; increased threat risk factors (e.g., physical health concerns from immunocompromised status)25,26, and demographics (e.g., gender and race)27–30. More rigorous evidence is needed to understand the relationship between PMIE exposure and occupational health and system outcomes; longitudinal designs that account for important covariates enable this enhanced rigor. The current study addresses these gaps by examining the risk that PMIE exposures confer for poor occupational health across one year (from May 2020 to May 2021) while controlling for key covariates, including mental health and physical health status. We hypothesized that HCWs who endorsed PMIE exposure by witnessing, participating, and feeling betrayed would be more likely to develop symptoms of occupational burnout and turnover intentions one year later than those who denied PMIE exposure (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Moral Injury Exposure Theoretical Model.

Methods

Procedure

All procedures were approved by University of Utah IRB. Participants were drawn from a larger study of frontline worker mental health and resilience entitled Resilience and Adaptation in Stress (RAISe) conducted in the western United States. From this study, 752 HCWs completed a survey in May 2020 of whom 473 completed a second follow up survey in May 2021, referred to as Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2), respectively. This study uses data from the HCW who had completed surveys at both T1 and T2 (see25,30–32).

Measures

Dependent variables

Turnover Intentions. The Turnover Intentions scale33 includes three items answered in a Likert format (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). Overall scores are determined by summing scores of the three individual items. A cutoff of 10 was established as an indicator of considering leaving their position. The variable was then re-coded to indicate 0 (no turnover intentions [< 10]) or 1 (yes, turnover intentions [≥ 10]).

Burnout. Time 1 and 2 burnout was assessed with a novel 3-item measure developed to approximately capture the three theorized dimensions of burnout in the WHO definition (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, competence; see34). At time 1, we chose to ‘approximate’ burnout rather than use a longer, more established measure based on our goal to reduce participant burden in the midst of an ongoing disaster. The three questions were: “I am losing my ability to be compassionate when at work” (depersonalization); “At my job I am very mentally and physically exhausted” (emotional exhaustion); and “I am losing the belief that I am effective at my job” (personal accomplishment). Response options ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Previously published research using this 3-item measure of burnout reported high internal consistency35, and analyses with the current sample also showed high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.76. For modeling purposes, we re-calculated a burnout cutoff based on participant agreeing with at least two out of three aspects of burnout. Time 1 burnout was also modeled as a covariate control in each model.

Independent and control variables

Exposure to Potentially Morally Injurious Events. The Moral Injury Events Scale36 was used to measure exposure to potentially morally injurious events through participating in (acts of commission or omission) witnessing events that violated sincerely held values, and experiences of betrayal. Example items included ‘I am troubled by having witnessed immoral acts,’ and ‘I feel betrayed by healthcare or public health organizations,’ and ‘I violated my own morals by failing to do something that I felt I should have done.’ Scores range from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. We used the same recoding strategy as Maguen and colleagues37, wherein scores from one to three on each subscale were recoded 0 (i.e., no exposure to PMIEs), and scores from four to six were recoded 1 (i.e., yes, exposure to PMIEs).

Mental Health Distress. We included separate measures of depression and anxiety distress. Depression was measured with The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2)38 containing two questions answered on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day). The two items were summed to obtain a total score, and a recommended clinical cutoff score of three or higher was used to indicate significant depression-related distress. Anxiety was measured with The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-2 (GAD-2)39 containing two of the items answered on a Likert scale format (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day). The items were summed to obtain a total score; a total score of three or higher was used as the clinical cutoff indicating significant anxiety-related distress.

Physical Health Risk. Two questions were included to assess COVID related health concerns for self or a household member in a yes/no answer format: (1) ‘do you have a compromised immune system due to a medical condition’, and (2) ‘does someone in your household have a compromised immune system due to a medical condition’25. We included binary indicators for whether each respondent was immunocompromised and whether someone in their household was immunocompromised.

Analytic approach

Analyses were conducted using Stata (Version 18). The outcomes of interest in all models were burnout and turnover intentions at T2. The primary independent variables included T1 moral injury exposure: (1) participating in a PMIE, (2) witnessing a PMIE, and (3) experiencing a betrayal related PMIE. Covariates were selected on the basis of evidence for their importance in explaining impact on professional functioning during the pandemic, including: gender/sex, race, years working in the career, professional role, depression, anxiety, immunocompromised self, and immunocompromised household status25,27,28,40–42. All covariates collected at T1 were used to predict T2 outcomes (Table 2).

We fitted Generalized Linear Models with a Poisson family and log link using robust standard errors (robust Poisson regression) to predict the risk of turnover and burnout (respectively), at T2. Each model included binary indicators for each of the 3 subtypes of PMIE and sociodemographic and health controls. Because a high proportion of healthcare workers indicated turnover intentions and burnout, we estimated relative risk rather than odds ratios43–46.

Results

Study sample/demographic characteristics

Of the 752 HCWs who completed the survey at T1, 473 also completed the survey at T2 and were included in the study population. To assess attrition bias we compared sociodemographic characteristics and included covariables of participants who completed the survey at T2 compared to those who did not. We did not find significant differences for most participant characteristics. Minor differences existed between those who completed the survey at only T1 vs those who completed at both time points. Namely, those who completed the survey at both time points were likely to have more years’ experience (RR = 1.01, 95% CI 1.01, 1.02); and of being in a non-clinical (RR = 1.19, 95% 1.03, 1.37) compared to a clinical role. The full attrition analysis is included as a supplemental file. Among our final study sample of 473 participants, 69.13% were in direct clinical roles (nurse, physician/APP/Resident, clinical staff, other role). The majority were female (82.03%) and white (91.97%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participants’ demographics and prevalence of predictor variables for the current study at T1.

| Demographic characteristic | % |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 82.03 |

| Male | 17.97 |

| Race | |

| White | 91.97 |

| Other represented race | 8.03 |

| Years career (average) | 11.74 (years) |

| Professional role | |

| Nurse | 27.7 |

| Physician/APP/Resident | 13.11 |

| Clinical staff (e.g., technician) | 13.11 |

| All other health professionals | 15.22 |

| Non-clinical professionals | 30.87 |

| Control variables | |

| Immunocompromised-self | |

| No [R] | 86.89 |

| Yes | 13.11 |

| Immunocompromised-household | |

| No [R] | 78.86 |

| Yes | 21.14 |

| Anxiety | |

| No [R] | 73.57 |

| Yes | 26.43 |

| Depression | |

| No [R] | 80.76 |

| Yes | 19.24 |

| PMIE exposure | |

| Witnessed | |

| No [R] | 58.56 |

| Yes | 41.44 |

| Participated | |

| No [R] | 82.33 |

| Yes | 17.67 |

| Betrayed | |

| No [R] | 23.39 |

| Yes | 76.61 |

APP = Advanced Practice Provider (Nurse Practitioner or Physician Assistant). R = Reference group.

(N = 473).

Prevalence of mental health concerns and PMIE exposure

At T1, 19.24% of the sample screened as having probable Major Depressive disorder and 26.43% screened as likely having Generalized Anxiety Disorder. 13.11% of participants were immunocompromised and 21.14% lived with someone who was immunocompromised.

The most frequently reported subtype of PMIE exposure at T1 was feelings of betrayal (76.61%), followed by those that witnessed a PMIE (41.44%). Moral injury attributed to those that participated in a PMIE by what one did or failed to do was less prevalent (17.67%). The mean years of experience in healthcare for participants was 11.74 years. See Table 3 for all detailed demographic information.

Risk of burnout and turnover

Table 4 presents the analysis with the relative risk with all of the T1 PMIE exposure subscales included simultaneously in the model, predicting outcomes (T2 burnout and T2 turnover intentions), adjusted for covariates.

Table 4.

Risk for turnover intentions and burnout following all PMIE exposures.

| (a) Risk for turnover intentions following all PMIE exposures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | RR | RSE | P >|z| | 95% CI | 95% CI |

| Sex | |||||

| Female [R] | |||||

| Male | 0.9782 | 0.2111 | 0.9190 | 0.6408 | 1.4933 |

| Race | |||||

| White [R] | |||||

| All other races | 0.6924 | 0.2680 | 0.3420 | 0.3242 | 1.4786 |

| Years career | 0.9866 | 0.0091 | 0.1460 | 0.9689 | 1.0047 |

| Professional role | |||||

| Nurse [R] | |||||

| Physician/APP/Resident | 0.7953 | 0.2246 | 0.4170 | 0.4572 | 1.3834 |

| Technicians | 1.0170 | 0.2095 | 0.9350 | 0.6791 | 1.5229 |

| All other clinical | 0.6182 | 0.1603 | 0.0640 | 0.3719 | 1.0276 |

| All non-clinical | 0.6554 | 0.1427 | 0.0520 | 0.4277 | 1.0043 |

| Immunocompromised-self | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.0346 | 0.2854 | 0.9020 | 0.6025 | 1.7765 |

| Immunocompromised-household | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.1949 | 0.2120 | 0.3150 | 0.8440 | 1.6917 |

| Anxiety | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.0775 | 0.1924 | 0.6760 | 0.7592 | 1.5291 |

| Depression | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.1343 | 0.2210 | 0.5180 | 0.7743 | 1.6617 |

| PMIE exposure | |||||

| Witnessed | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.6583 | 0.2916 | 0.0040 | 1.1749 | 2.3407 |

| Participated | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.0783 | 0.2007 | 0.6850 | 0.7487 | 1.5531 |

| Being Betrayed | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.5735 | 0.4165 | 0.0870 | 0.9367 | 2.6435 |

| Burnout | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.4202 | 0.2482 | 0.0450 | 1.0083 | 2.0002 |

| (b) Risk for burnout following all PMIE exposures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | RR | RSE | P >|z| | 95% CI | 95% CI |

| Sex | |||||

| Female [R] | |||||

| Male | 1.0618 | 0.1833 | 0.7280 | 0.7570 | 1.4893 |

| Race | |||||

| White [R] | |||||

| All other races | 0.7506 | 0.2453 | 0.3800 | 0.3956 | 1.4242 |

| Years career | 1.0005 | 0.0065 | 0.9440 | 0.9879 | 1.0132 |

| Professional role | |||||

| Nurse [R] | |||||

| Physician/APP/Resident | 1.1923 | 0.2859 | 0.4630 | 0.7452 | 1.9077 |

| Technicians | 1.0217 | 0.2049 | 0.9150 | 0.6897 | 1.5136 |

| All other clinical | 1.2894 | 0.2333 | 0.1600 | 0.9044 | 1.8383 |

| All non-clinical | 0.6731 | 0.1424 | 0.0610 | 0.4446 | 1.0188 |

| Immunocompromised-self | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.1867 | 0.2586 | 0.4320 | 0.7741 | 1.8191 |

| Immunocompromised-household | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 0.9378 | 0.1636 | 0.7130 | 0.6662 | 1.3200 |

| Anxiety | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.2065 | 0.1942 | 0.2440 | 0.8800 | 1.6542 |

| Depression | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.4059 | 0.2330 | 0.0400 | 1.0160 | 1.9455 |

| PMIE exposure | |||||

| Witnessed | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.2491 | 0.1857 | 0.1350 | 0.9334 | 1.6716 |

| Participated | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.3776 | 0.2061 | 0.0320 | 1.0275 | 1.8469 |

| Being Betrayed | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 1.3233 | 0.2656 | 0.1630 | 0.8929 | 1.9611 |

| Burnout | |||||

| No [R] | |||||

| Yes | 2.5237 | 0.4100 | 0.0000 | 1.8354 | 3.4701 |

Generalized Linear Models (Poisson family with robust standard errors) as possible factors that may increase risk for burnout and turnover across a 1-year span among healthcare workers. RR = Relative Risk; RSE = Robust Standard Errors.

On multivariate analysis, among the variables assessed, PMIE exposure stood as the strongest predictor of turnover intentions at T2. Specifically, those that reported they had witnessed a PMIE at T1 were at higher risk for T2 turnover intentions (RR = 1.66, 95% CI 1.17, 2.34). T1 burnout also predicted greater risk for T2 turnover intentions (RR = 1.42, 95% CI 1.01, 2.00). Models that showed significance with individual PMIE predictors (witnessed, feeling betrayed) of turnover intentions found that feeling betrayed also predicted turnover intentions when it was the only moral injury exposure included in the model. These individual models are available as a supplemental table. No statistically significant association between participation or betrayal PMIEs and T2 turnover intentions was observed when all PMIE exposures were included simultaneously in the model.

On multivariate analysis, T1 burnout was the strongest predictor of T2 burnout (RR = 2.52, 95% CI 1.84, 3.47). Those that screened positive for depression at T1 were at higher risk for T2 burnout (RR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.02, 1.95). Individuals who reported they had participated in a PMIE at T1 were also at higher risk for T2 burnout (RR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.03, 1.85). Models that showed significance with individual PMIE predictors (participated, feeling betrayed) of burnout found that feeling betrayed also predicted burnout when it was the only moral injury exposure included in the model. These individual models are available as a supplemental table. No statistically significant association between witnessing or betrayal PMIEs and T2 burnout was observed when all PMIE exposures were included simultaneously in the model.

Using Stata’s margins command, Table 5 shows the prevalence of turnover intentions and burnout in those that did not endorse PMIE exposure, compared to those that did. Among those that did not endorse a witnessed PMIE in the turnover intentions model with all three PMIE exposures, 18.85% of HCWs screened positive for turnover intentions; if a witnessed PMIE was endorsed, 31.26% screened above the threshold for turnover intentions. This equates to a 12.41% increased prevalence of turnover intentions among those exposed to a witnessed PMIE relative to those unexposed. In the burnout model, 26.68% of HCWs met the screened positive for burnout among those that did not endorsing participating in a PMIE. For those that participated in a PMIE (i.e., personally participated/self PMIEs), 36.75% screened positive for burnout. This equates to a 10.07% increased prevalence of burnout for HCWs that participated in a PMIEs (i.e., personally participated/self PMIEs) relative to those unexposed.

Table 5.

Prevalence differences of turnover and burnout between healthcare workers exposed and not exposed to potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs).

| PMIE exposure | Prevalence% | DMSE | P > chi2 | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Witnessed a PMIE (from Turnover Model) | |||||

| No [R] | 18.85 | 0.0258 | 0.1380 | 0.2391 | |

| Yes | 31.26 | 0.0316 | 0.2507 | 0.3746 | |

| Prevalence difference turnover | 12.41 | 0.0422 | 0.0033 | 0.0414 | 0.2068 |

| Participated in a PMIE (from Burnout Model) | |||||

| No [R] | 26.68 | 0.0214 | 0.2249 | 0.3086 | |

| Yes | 36.75 | 0.0455 | 0.2783 | 0.4567 | |

| Prevalence difference burnout | 10.07 | 0.0509 | 0.0478 | .0010 | 0.2005 |

Prevalence difference in significant exposures of interest from Stata’s margins command following Generalized Linear Models (Poisson family with robust standard errors) as possible factors that may increase risk for burnout and turnover across a 1-year span among healthcare. DMSE = Delta Method Standard Errors.

Discussion

We conducted one of the only longitudinal studies to examine the relationship between PMIE exposure and occupational health among HCWs7. Our findings show that exposure to PMIEs by witnessing (41%), participating (17%), and feeling betrayed (76%) was common in a large, organization-based sample of HCWs in the Rocky Mountain region of the United States collected during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Similar rates of exposure have previously been reported across the US47 and internationally16 among samples of HCWs collected during the pandemic. While it is possible that rates of exposure might decrease during periods when healthcare systems are under less strain than was the case during the pandemic, it is likely that many HCWs will continue to experience PMIE exposure. This is especially true given qualitative studies that attribute PMIE exposure to enduring issues in healthcare, such as inherent conflicts between healthcare systems that prioritize efficient use of resources and frontline clinicians that prioritize individual patient outcomes48.

Furthermore, we found that specific PMIE exposure conferred risk for turnover and burnout one year later, extending prior cross-sectional work that primarily has focused on the association between PMIE exposure and mental health symptom severity49. After adjusting for demographic and occupational characteristics as well as physical and mental health status, HCWs in our sample who endorsed witnessing others in the organization act in ways that they perceived to be morally wrong had 66% greater risk of turnover versus those who denied exposure by witnessing. Notably, the association between PMIE and turnover was specific to type of PMIE, whereas significant association with turnover was not observed for participation or betrayal PMIE. Specific PMIEs were also associated with T2 burnout. Those who reported participating in a PMIE because of what they did or failed to do had 38% greater risk of screening positive for burnout versus those who denied exposure by participating. No statistically significant association between witness or betrayal PMIE and T2 burnout in this analysis after adjusting for other types of PMIE exposure, individual characteristics, and health status. Taken together, although being betrayed was the most commonly endorsed type of exposure, feeling personally responsible for participating in a PMIE or witnessing PMIE by the team to which one belongs appears to be more pernicious. This is consistent with prior work illustrating that PMIE exposure is linked to functional impairment, particularly for male military veterans who endorsed participating in a PMIE50.

The finding that greater risk of screening positive for turnover intentions was associated with witnessing a PMIE but not being the victim of others’ wrongful facts (i.e., being betrayed) is notable. It will be important to determine if future studies replicate what we observed. These findings raise the question of what it is about witnessing a PMIE that might motivate a HCW to leave their organization. One explanation might be that HCWs who witness others’ engage in acts that they perceive as morally wrong may feel that they do not share fundamental beliefs with the coworkers in their organization which may lead them to seek a different work group. Holistic efforts to improve retention should therefore include system-based interventions focused on shared values, psychologic safety, confidential professionalism reporting system, just culture and structure and process for an appropriate organizational response in addition to emotional support for individuals who have witnessed such events51.

Additionally, the finding that higher risk for burnout was associated with participating in a PMIE by what one did or failed to do is notable. Distinct from witnessing a PMIE by a colleague or coworker and its association with turnover, participating in a PMIE appears to cause personal occupational distress (i.e., burnout). While leaving an environment where you witness PMIEs may be viewed as strategy to avoid future PMIE exposure, when you directly participated in the PMIE there is “no where to go”. This situation has the potential to directly impact the depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and personal accomplishment domains of burnout. According to Griffin and colleagues7, in such circumstances HCWs might respond to PMIE exposure by withdrawing (e.g., by relocating to different health systems or leaving the profession) but also by over-functioning. They might take on additional patient care duties or practice more defensively by ordering unnecessary tests in an attempt to do more good than harm, especially given barriers to amend-making, such as when rules about patient privacy prohibit healthcare from offering an apology or reparation to patients who are impacted by suboptimal care. Thus, organizations must also create structures to support individual HCWs who feel they have participated in PMIE. Although there currently is no gold-standard psychotherapy for HCWs affected by moral injury, numerous protocols are in various stages of development and testing with military veterans that could be adapted including the following: Adaptive Disclosure, Building Spiritual Strength, Impact of Killing, MC3 (Mental Health Clinician Community Clergy Collaboration), and Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction, and the Mindful Ethical Practice and Resilience Academy developed for HCWs52–58.

Also, there are numerous team and unit level interventions that could prove fruitful in reducing the impact of PMIE exposure. Exposure to PMIEs cultivate social disillusionment, unit cohesion problems, and alienation8. Accordingly, interventions such as RECONN (Reflection and Reconnection)59 and RE-WIRE (Re-engaging Worthy Interpersonal Relationships)60 could facilitate moral repair by targeting team cohesion, authentic and honest sharing, mutual support amidst PMIEs, and values-congruent behavior. Additionally, improving psychological safety, communication, and leadership behaviors are key elements of protection from PMIEs; intervention structures such as ‘positive rounding’ and ‘safety rounding’ would be appropriate and helpful61–63. Further, models already exist to embed help within units to come from trusted fellow frontline workers, including quality or well-being champions or ambassadors with training to build capacity to deal with local deficits, using evidence-based interventions and resources supported via randomized trials64–68. Pending the need for future reviews (scoping, systematic, meta-analytic), these are all viable start points for units and healthcare systems looking for evidence-supported ways to begin to address pervasive PMIEs and impact on staffing and quality care.

The need for paradigm shifts toward culture change does not mean our current predicament is the sole responsibility or fault of healthcare leaders, as moral challenges exist across all levels of healthcare69,70. Framing problems related to PMIE exposure solely as problems between healthcare leaders and front-line workers is overly simplistic, non-productive, and risks furthering “us vs. them” divides71. The way forward necessitates the ability to tolerate complexity, of the shared burden from embeddedness in profit driven healthcare systems that are largely misaligned with the values and goals of clinicians. Application of a psychospiritual developmental model72 may clarify the competing moral demands of healthcare workers/leaders face without placing blame, but rather in the context of more productive “developmental” processes that must be co-owned and co-solved. Through a developmental lens, we can work towards acknowledging and understanding the natural existence of PMIEs across all levels of healthcare, especially in areas where value discrepancies exist between organizational leadership and frontline HCWs73.

Much of the existing moral injury theory and intervention literature has focused on Veterans9,74,75. But there are key differences in the phenomenology of PMIEs between HCWs and veterans that may have implications for policy, prevention, and intervention. For HCWs, PMIEs involve ongoing chronic exposures that occur in their own communities at “home,” whereas military based PMIEs occur largely in past tense in geolocations far from “home." Further, our data here suggest that the most frequent source of moral injury is different: HCWs largely derive moral injury from witnessing and betrayal (i.e., immersion in social perpetrations by others), whereas military moral injury largely derives from participating in events that violate sincerely held beliefs. Adapting existing interventions will benefit from studying implementation barriers and facilitators in healthcare contexts. For example, given the understaffed and overtaxed healthcare workplace context, increasing accessibility, utilization, and effectiveness may require implementation of interventions at the workplace during work hours on paid time.

Limitations

This study is limited in several ways. First, the sample largely consists of white, female nurses with an average of a decade of career experience. Additional research is needed for broader generalizability, reduced inequities, and building more inclusive and accurate evidence bases (diverse racial, gender, professional, and career stages). Additionally, results should be considered in the context of data collected during a disaster period (pandemic).

The Moral Injury Events scale is a measure of exposure, not symptoms or functional problems that may result from PMIEs. Future studies will be better served by using a measure that can differentiate exposure from ways that exposures impact functioning. Examples of moral injury functioning severity measures include the Expressions of Moral Injury Scale76, Moral Injury Outcome Scale77, and the Moral Injury and Distress Scale78. Additionally, our choice to recode exposure to a binary variable limits more nuanced understanding of PMIEs relative to volume of exposure that can be addressed in future research. Burnout in the present study was also assessed using three novel questions based on the three dimensions of the burnout construct rather than established, validated burnout assessment instrument. Because we focused on moral injury exposure, we did not incorporate a moral distress measure. Moral distress has been long studied in HCWs and further work is needed to conceptualize and integrate the moral injury and moral distress constructs.

Lastly, note that we do not interpret a null finding for being betrayed as a factor of null effect; rather, it is possible that the ubiquity and limited variability in the betrayal PMIE exposure experience (i.e., ~ 76% of the sample) yielded this a null finding in our models. Trust rebuilding between frontline workers, community, and organizations seems an issue of paramount import in the current climate.

Conclusion

Holistic organizational efforts to address system factors contributing to HCW well-being must address PMIE exposure at the individual, unit, organizational, and system levels of our healthcare infrastructure79. Further research is needed to understand and address the impact of PMIEs on HCWs’ occupational health. Given our results related to witnessing a PMIE, much of this research needs to include an organizational lens, which would benefit from a developmental model approach. Moreover, our findings raise significant questions and invite reflection on current health system and insurance industry practices. In the United States, horizontal/vertical merger “culture,” monopolistic behaviors, and permeation of profit motives in health care may contribute to value discrepancies between those carrying out healthcare on the ground and those who profit. Our results underscore the need for a new healthcare system and organizational leadership paradigm that includes clinician and HCW well-being (even at the policy and regulatory levels) as a core component to high quality care80.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Susan and Richard Levy Healthcare Delivery Incubator and Human Resources Services Administration (U3M45388). The expressed opinions are those of the authors and not necessarily the official positions of the Levy Healthcare Delivery Levy Healthcare Delivery Incubator, HRSA or the Department of Veterans Affairs. The lead author would like to thank: Rebecca Wurtz, Mark Linzer, Mary Butler, Nathan Shippee, Stuart Grande, and Jeffrey Pyne for their feedback and guidance.

Author contributions

Paper design, conceptualization, and analytic plan: TU, LB, BG, AS. Data analysis: TU, LB, AS. Manuscript writing, editing, and refinement: All authors.

Data availability

A limited codebook and analytic code are available upon request (requests can be sent to: usse0006@umn.edu). The RAISe study is not a public access dataset.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts/competing (financial and non-financial) of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Timothy J. Usset, Email: usse0006@umn.edu

Andrew J. Smith, Email: andrew.j.smith-2@dartmouth.edu

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-74086-0.

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. Taking action against clinician burnout: a systems approach to professional well-being. (2019). [PubMed]

- 2.Shanafelt, T. & kuriakose, c. widespread Clinician Shortages Create a Crisis that Will Take Years to Resolve. NEJM Catalyst Innov. Care Deliv.10.1056/CAT.23.0044 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanafelt, T. D. et al.Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Integration in Physicians During the First 2 Years of the COVID-19 Pandemic (Elsevier, 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sexton, J. B. et al. Emotional exhaustion among US health care workers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2019–2021. JAMA Netw. Open5(9), e2232748–e2232748 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West, C. P. et al. Resilience and burnout among physicians and the general US working population. JAMA Netw. Open3(7), e209385–e209385 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiken, L. H. et al. Physician and nurse well-being and preferred interventions to address burnout in hospital practice: factors associated with turnover, outcomes, and patient safety. In JAMA Health Forum (Vol. 4, No. 7, pp. e231809–e231809). American Medical Association. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Griffin, B. J., Weber, M. C., Hinkson, K.D. et al. Toward a dimensional contextual model of moral injury: A scoping review on healthcare workers. Curr. Treatment Opt. Psychiatry. 10(3), 199–216 (2023).

- 8.Jinkerson, J. D. Defining and assessing moral injury: A syndrome perspective. Traumatology.22(2), 122 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Litz, B. T. et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin. Psychol. Rev.29(8), 695–706 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billings, J. et al. Experiences of mental health professionals supporting front-line health and social care workers during COVID-19: qualitative study. BJPsych Open.10.1192/bjo.2021.29 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billings, J. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on health-care workers. Lancet Psychiatry.10(1), 3–5 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maguen, S. & Price, M. A. Moral injury in the wake of coronavirus: Attending to the psychological impact of the pandemic. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res Practice Policy.12(S1), S131 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue, Y. et al. Potential circumstances associated with moral injury and moral distress in healthcare workers and public safety personnel across the globe during COVID-19: A scoping review. Front. Psychiatry.10.3389/fpsyt.2022.863232 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amsalem, D. et al. Psychiatric symptoms and moral injury among US healthcare workers in the COVID-19 era. BMC Psychiatry.21(1), 1–8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, Z. et al. Moral injury in Chinese health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Practice Policy.14(2), 250 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williamson, V. et al. Moral injury and psychological wellbeing in UK healthcare staff. J. Mental Health.32(5), 890–898 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, Z. et al. Moral injury in Chinese health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Practice Policy.14(2), 250 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Veer, A. J., Francke, A. L., Struijs, A. & Willems, D. L. Determinants of moral distress in daily nursing practice: a cross sectional correlational questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud.50(1), 100–108 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dale, L. P. et al. Morally distressing experiences, moral injury, and burnout in Florida healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health.18(23), 12319 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer, I. C. et al. Downstream consequences of moral distress in COVID-19 frontline healthcare workers: Longitudinal associations with moral injury-related guilt. General Hosp. Psychiatry.79, 158–161 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanojević, S. & Čartolovni, A. Moral distress and moral injury and their interplay as a challenge for leadership and management: The case of Croatia. J. Nurs. Manage.30(7), 2335–2345 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hines, S. E., Chin, K. H., Glick, D. R. & Wickwire, E. M. Trends in moral injury, distress, and resilience factors among healthcare workers at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health.18(2), 488 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Testoni, I. et al. Burnout following moral injury and dehumanization: A study of distress among Italian medical staff during the first COVID-19 pandemic period. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice Policy. 15(S2), S357 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Stein, N. R. et al. A scheme for categorizing traumatic military events. Behav. Modif.36(6), 787–807 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith, A. J. et al. Mental health risks differentially associated with immunocompromised status among healthcare workers and family members at the pandemic outset. Brain Behav. Immun Health.15, 100285 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright, H. M. et al. Pandemic-Related Mental Health Risk among Front Line Personnel. J. Psychiatr. Res. (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Barello, S., Palamenghi, L. & Graffigna, G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res.290, 113129 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grumbach, K. et al. Association of race/ethnicity with likeliness of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among health workers and the general population in the San Francisco Bay Area. JAMA Intern. Med.181(7), 1008–1011 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossen, L. M., Branum, A. M., Ahmad, F. B., Sutton, P. & Anderson, R. N. Excess deaths associated with COVID-19, by age and race and ethnicity—United States, January 26–October 3, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep.69(42), 1522 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weber, M. C. et al. Moral injury and psychosocial functioning in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Services. 10.1037/ser0000718 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith, A. J., Shoji, K., Griffin, B. J. et al. Social cognitive mechanisms in healthcare worker resilience across time during the pandemic. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. 57(7), 1457–1468 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Ehman, A. C. et al. Exposure to potentially morally injurious events and mental health outcomes among frontline workers affected by the coronavirus pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research Practice Policy. (2022) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Vigoda-Gadot, E. K. & Kapun, D. Perceptions of politics and perceived performance in public and private organisations: a test of one model across two sectors. Policy Politics33(2), 251–276 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wb, S. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud.3, 71–92 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griffin, B. J. et al. The impact of adjustment on workplace attitudes and behaviors among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Occupat. Environ. Med.10.1097/JOM.0000000000003066 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nash, W. P. et al. Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury events scale. Military Med.178(6), 646–652 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maguen, S. et al. Trajectories of functioning in a population-based sample of veterans: contributions of moral injury, PTSD, and depression. Psychol. Med. 1–10 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med. Care. 1284–1292 (2003) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Monahan, P. O. & Löwe, B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann. Intern. Med.146(5), 317–325 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai, J. et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open.3(3), e203976–e203976 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber, M. et al. Moral injury and psychosocial functioning in healthcare workers Psychological Services. 20(1), 19 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Power, K. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustain. Sci Practice Policy.16(1), 67–73 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNutt, L.-A., Wu, C., Xue, X. & Hafner, J. P. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am. J. Epidemiol.157(10), 940–943 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zou, G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am. J. Epidemiol.159(7), 702–706 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenland, S. Model-based estimation of relative risks and other epidemiologic measures in studies of common outcomes and in case-control studies. Am. J. Epidemiol.160(4), 301–305 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen, W., Qian, L., Shi, J. & Franklin, M. Comparing performance between log-binomial and robust Poisson regression models for estimating risk ratios under model misspecification. BMC Med. Res. Methodol.18(1), 1–12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amsalem, D. et al. Psychiatric symptoms and moral injury among US healthcare workers in the COVID-19 era. BMC Psychiatry.21(1), 546 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riedel, P.-L., Kreh, A., Kulcar, V., Lieber, A. & Juen, B. A scoping review of moral stressors, moral distress and moral injury in healthcare workers during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health.19(3), 1666 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greene, T. et al. Exposure to potentially morally injurious events in UK health and social care workers during COVID-19: Associations with PTSD and complex PTSD. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Practice Policy. (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Maguen, S. et al. Gender differences in prevalence and outcomes of exposure to potentially morally injurious events among post-9/11 veterans. J. Psychiatric Res.130, 97–103 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Dossary, R. et al. The public health problem of burnout in health professionals. 130 (2023).

- 52.Gray, M. J. et al. Adaptive disclosure: An open trial of a novel exposure-based intervention for service members with combat-related psychological stress injuries. Behav. Therapy.43(2), 407–415 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris, J. I. et al. The effectiveness of a trauma focused spiritually integrated intervention for veterans exposed to trauma. J. Clin. Psychol.67(4), 425–438 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harris, J. I. et al. Spiritually integrated care for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial of “Building Spiritual Strength”. Psychiatry Res.267, 420–428 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maguen, S. et al. Impact of killing in war: A randomized, controlled pilot trial. J. Clin. Psychol.73(9), 997–1012 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pyne, J. M. et al. Mental health clinician community clergy collaboration to address moral injury symptoms: A feasibility study. J. Relig. Health.60, 3034–3051 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norman, S. Trauma-informed guilt reduction therapy: overview of the treatment and research. Curr. Treat. Options Psych.9(3), 115–125 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Norman, S. B., Wilkins, K. C., Myers, U. S. & Allard, C. B. Trauma informed guilt reduction therapy with combat veterans. Cogn. Behav. Practice.21(1), 78–88 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Usset, TJ GC, et al. Building social support and moral healing on nursing units: Designing and testing a culture change intervention. Behavioral Sciences. 14(9), 796 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Smith, A. J., Pincus, D. & Ricca, B. Targeting social behavioral actions in the context of Trauma: Functional outcomes and mechanisms of change. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 28, 300–309 (2023).

- 61.Sexton, J. B. et al. Safety culture and workforce well-being associations with positive leadership walkrounds. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf.47(7), 403–411 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sexton, J. B. et al. Providing feedback following Leadership WalkRounds is associated with better patient safety culture, higher employee engagement and lower burnout. BMJ Qual. Saf.27(4), 261–270 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adair, K. C. et al. The Psychological Safety Scale of the Safety, Communication, Operational, Reliability, and Engagement (SCORE) Survey: a brief, diagnostic, and actionable metric for the ability to speak up in healthcare settings. J. Patient Saf.18(6), 513–520 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Profit, J. et al. Randomized controlled trial of the “WISER” intervention to reduce healthcare worker burnout. J. Perinatol.41(9), 2225–2234 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sexton, J. B., Adair, K. C., Cui, X., Tawfik, D. S. & Profit, J. Effectiveness of a bite-sized web-based intervention to improve healthcare worker wellbeing: A randomized clinical trial of WISER. Front. Public Health.10, 1016407 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Panagioti, M. et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med.177(2), 195–205 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.West, C. P., Dyrbye, L. N., Erwin, P. J. & Shanafelt, T. D. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet.388(10057), 2272–2281 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shanafelt, T., Trockel, M., Rodriguez, A. & Logan, D. Wellness-centered leadership: equipping health care leaders to cultivate physician well-being and professional fulfillment. Academic Med.96(5), 641 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hertelendy, A. J. et al. Mitigating moral distress in leaders of healthcare organizations: A scoping review. J. Healthcare Manage.67(5), 380–402 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shanafelt, T. D. et al. Healing the professional culture of medicine 1556–1566 (Elsevier, 2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shanafelt, T. D. Physician well-being 20: where are we and where are we going? 2682–2693 (Elsevier, 2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harris, J. I., Park, C. L., Currier, J. M., Usset, T. J. & Voecks, C. D. Moral injury and psycho-spiritual development: Considering the developmental context. Spirit. Clin. Practice.2(4), 256 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pavlova, A., Paine, S. J., Sinclair, S., O'Callaghan, A., Consedine, N. S. Working in value‐discrepant environments inhibits clinicians’ ability to provide compassion and reduces well‐being: A cross‐sectional study. J. Intern. Med. (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Griffin, B. J. et al. Moral injury: An integrative review. J. Traumatic Stress.32(3), 350–362 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frankfurt, S. & Frazier, P. A review of research on moral injury in combat veterans. Military Psychol.28(5), 318–330 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Currier, J. M. et al. Development and evaluation of the Expressions of Moral Injury Scale—Military Version. Clin. Psychol. Psychother.25(3), 474–488 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Litz, B. T. et al. Defining and assessing the syndrome of moral injury: Initial findings of the moral injury outcome scale consortium. Front. Psychiatry.13, 923928 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Norman, SB. et al. The Moral Injury and Distress Scale: Psychometric evaluation and initial validation in three high-risk populations. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Epstein, E. G., Whitehead, P. B., Prompahakul, C., Thacker, L. R. & Hamric, A. B. Enhancing understanding of moral distress: the measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empirical Bioethics.10(2), 113–124 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bodenheimer, T. & Sinsky, C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann. Fam. Med.12(6), 573–576 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A limited codebook and analytic code are available upon request (requests can be sent to: usse0006@umn.edu). The RAISe study is not a public access dataset.