Abstract

Maternal stress and depression during pregnancy and the first year of the infant’s life affect a large percentage of mothers. Maternal stress and depression have been associated with adverse fetal and childhood outcomes as well as differential child DNA methylation (DNAm). However, the biological mechanisms connecting maternal stress and depression to poor health outcomes in children are still largely unknown. Here we aim to determine whether prenatal stress and depression are associated with differences in cord blood mononuclear cell DNAm (CBMC-DNAm) in newborns (n = 119) and whether postnatal stress and depression are associated with differences in peripheral blood mononuclear cell DNAm (PBMC-DNAm) in children of 12 months of age (n = 113) from the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) cohort. Stress was measured using the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and depression was measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Questionnaire (CESD). Both stress and depression were measured longitudinally at 18 weeks and 36 weeks of pregnancy and six months and 12 months postpartum. We conducted epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) using robust linear regression followed by a sensitivity analysis in which we bias-adjusted for inflation and unmeasured confounding using the bacon and cate methods. To quantify the cumulative effect of maternal stress and depression, we created composite prenatal and postnatal adversity scores. We identified a significant association between prenatal stress and differential CBMC-DNAm at 8 CpG sites and between prenatal depression and differential CBMC-DNAm at 2 CpG sites. Additionally, we identified a significant association between postnatal stress and differential PBMC-DNAm at 8 CpG sites and between postnatal depression and differential PBMC-DNAm at 11 CpG sites. Using our composite scores, we further identified 2 CpG sites significantly associated with prenatal adversity and 7 CpG sites significantly associated with postnatal adversity. Several of the associated genes, including PLAGL1, HYMAI, BRD2, and ERC2 have been implicated in adverse fetal outcomes and neuropsychiatric disorders. These data further support the finding that differential DNAm may play a role in the relationship between maternal mental health and child health.

Subject terms: Genomics, Psychology

Introduction

Psychosocial factors such as maternal stress and depression during pregnancy and the first year of the infants’ life affect a large percentage of mothers (pre- and postnatal depression: ~12%; pre- and postnatal stress: ~25% [1, 2]). Gestation and the first years of life are critical and particularly sensitive periods for child development [3]. Psychosocial stress during this time can affect the developmental trajectory of the child and increase susceptibility to adverse fetal and childhood outcomes [4–7]. Maternal stress and depression during pregnancy have been associated with adverse fetal outcomes such as low birth weight and preterm birth [8, 9] as well as adverse childhood outcomes [10–15]. Prenatal stress has been previously associated with neurodevelopmental disorders in children, including an increased risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), cognitive delay, and schizophrenia [10–12]. Prenatal depression has been associated with variations in white matter integrity, with implications for emotional and behavioral function, cognitive development, language development, and motor development in children [13–15]. Mother-infant interactions during the first year of life play a major role in the behavioral and cognitive development of the child [16–18]. Maternal postpartum stress or depression during this time has been associated with behavioral dysfunction (anger, withdrawal) and delayed cognitive development in infants [19, 20]. Additionally, infants may express abnormal attachment patterns in response to maternal disengagement [21].

While maternal stress and depression during the perinatal period have been linked to the etiology of a range of health outcomes in children, the biological mechanisms are still unknown. In the prenatal period, it has been hypothesized that maternal stress and depression affect the fetus through the mother’s hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which produces cortisol in response to stressors [22]. Cortisol is a glucocorticoid (GC) hormone that crosses the placenta and plays a key role in fetal development [23]. While physiological concentrations of GCs are critical for fetal brain development, excess exposure to GCs are neurotoxic and negatively affect fetal development [24]. Other biological pathways have also been proposed, including catecholamines, oxidative stress, pro-inflammatory cytokines, serotonin, and the maternal gut-brain axis [6]. Postnatally, it has been hypothesized that cortisol may be passed to the child via breastmilk which can in turn affect child development [25]. However, postpartum maternal stress and depression seem to manifest in the child as behavioral and cognitive dysfunction even after accounting for breastfeeding status [26, 27]. At the biological level, high stress and depression levels may induce epigenetic modifications which in turn can increase the production of maternal cortisol and other potential biological mediators [6, 28, 29]. Epigenetic modifications, such as differential DNA methylation (DNAm) are malleable and sensitive to psychosocial factors [30]. Epigenetic regulation plays an important role in cell differentiation and development, as well as in mediating adaptive responses to psychosocial influences. Additionally, DNAm is potentially reversible, suggesting that the methylome could be a therapeutic target for disease treatment and prevention [31].

Despite widespread interest in the role of epigenetics as a potential nexus between the mother and the child, the literature on maternal psychosocial stress and child DNA methylation is incomplete and contradictory. Several EWAS have identified associations between prenatal depression and differential cord blood DNAm [32–35], while only a few EWAS have investigated the associations between prenatal stress and DNA methylation, and the associations they report are inconsistent. For example, one study found null associations between prenatal perceived stress and cord blood DNAm [36]. Another study did find an association between prenatal perceived stress and neonatal saliva DNAm using a prenatal distress questionnaire and cortisol as measures of prenatal stress [37]. Meta-analyses of large-scale EWAS have also been inconsistent in their findings regarding the nature and strength of the associations between prenatal stress, depression, and variations in DNAm [38–41]. In contrast, several candidate gene studies have investigated differential DNAm in genes such as 11β-HSD2, FKBP5, and NR3C1 as potential mediating factors [40, 42, 43]. For example, differential DNAm in 11β-HSD2 and NR3C1 and their respective interaction with prenatal depression have been associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in children [42]. During the postnatal period, associations between postpartum stress and depression and child DNA methylation have not been extensively studied despite the established relationship between postpartum maternal mental health and child development. While evidence of an association between postpartum depressive symptoms and numerous differentially methylated gene regions have been identified in two studies using next-generation sequencing [44] and the Illumina EPIC array [45] respectively, more EWASs, candidate gene studies, and large-scale meta-analyses have yet to be conducted.

Here, we conducted a prospective EWAS of maternal psychosocial status and child DNAm in a study of 131 children from the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) cohort, using well-established measures of stress and depression [46]. Specifically, we investigated whether prenatal stress and depression are associated with variations in cord-blood mononuclear cell DNAm (CBMC-DNAm) in newborns (n = 119) and whether postnatal stress and depression are associated with differences in peripheral blood mononuclear cell DNAm (PBMC-DNAm) among one-year-olds (n = 113). Stress and depression were analyzed separately, as well as in combination using composite adversity scores to explore the cumulative effect of stress and depression on DNAm. Additionally, to validate the robustness of our findings across exposure timepoints, we 1) investigated the associations between prenatal stress and depression and infant DNA methylation (PBMC-DNAm) at 12 months of age and 2) adjusted for prenatal stress in the postnatal stress model and for prenatal depression in the postnatal depression model to control for possible confounding by prenatal exposure.

Materials and methods

Study population

The CHILD cohort is a Canadian population-based birth cohort [46, 47]. Mothers (N = 3624) were enrolled during their second trimester of pregnancy between 2008 and 2012 and followed through pregnancy at four sites in Canada (Vancouver, Edmonton, Winnipeg, and Toronto). Mother-child pairs were then followed from birth through at least five years of age. Because the primary aim of the overall CHILD cohort study is to identify genetic and environmental determinants of atopic disease, DNAm samples were selected based on the child’s atopy status. All cases were included for DNAm sampling as well as controls randomly sampled from the underlying CHILD cohort. Therefore, the present study is a secondary analysis consisting of 131 mother-child pairs from an atopy-enriched subset of CHILD participants with DNAm data from cord blood and peripheral blood, genotype data, and either or both prenatal and postnatal mental health measures, and important covariates. Of these, there were 119 infants with complete information for the prenatal models and 113 infants with complete information for the postnatal models. Ethical approval for human subject research was given by the research ethics board at each study site: McMaster University, University of British Columbia, University of Manitoba, University of Alberta, and The Hospital for Sick Children. Written consent for participation was obtained from the mother at enrollment on behalf of herself and the infant.

DNA methylation measurements

DNA methylation was measured from cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMC) at birth and from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) at 12 months of age using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (450K) array. Details regarding the collection of cord blood and whole blood, preparation of CBMC and PBMC, and DNA extraction and methylation profiling are described elsewhere [47–49]. Briefly, CBMC and PBMC preparation removes granulocytes including neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils, leaving the sample enriched in immune cell types that are more relevant for the adaptive immune system. Background subtraction and color correction were performed with Illumina GenomeStudio software before data was imported to R for preprocessing. All subsequent preprocessing was performed using R version 3.5.1.

Sixty-five single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) probes were used to check concordances between paired samples and the corresponding probes were removed from the dataset. Next, probes not detected above the background or with fewer than three beads contributing to the signal in at least one sample (n = 5464), X/Y chromosome probes (n = 11,186), and poorly designed probes (n = 31, 076) were removed [50]. Invariant probes as identified from a meta-analysis by Edgar et al. were also removed (n = 111,193) [51].

Samples were determined to be outliers if detected using the detectOutlier function from the lumi package [52]. One CBMC-DNAm sample was detected as an outlier and it and its corresponding PBMC-DNAm sample were removed. The probe design bias was removed using beta-mixture quantile normalization (BMIQ) [53] and batch effects (sentrix ID, sentrix position, and run) were removed using the ComBat function from the sva package [54]. After sampling and probe filtering, 131 samples (overlap of 113 CBMC samples and 119 PBMC samples), 307,566 CBMC probes, and 309,620 PBMC probes remained for analysis. Cell type composition estimates were calculated using the most recent reference data for cord blood [55] and whole blood [56]. Genetic principal components were calculated to adjust for population stratification.

Maternal stress and depression measurements

Prenatal and postnatal stress were measured using the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [57]. The PSS scale is a widely used instrument for measuring psychological stress based on respondents’ impressions of stressful, uncontrollable, and unpredictable situations in the last month. Questions were asked on a 5-point Likert scale to assess how often participants felt stressed during situations, where a score of 0 meant “Never” and a score of “4” meant “Very Often”. All responses were summed to compute a total score ranging from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher psychological stress. Prenatal and postnatal depression were measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Questionnaire (CESD) [58]. The CESD assesses depressive symptoms during the last seven days. Questions were asked on a 4-point Likert scale, where a score of 0 meant “rarely or none of the time” and a score of 3 meant “all of the time”. Responses were summed to compute a total score ranging from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating more depression symptomatology. Prenatal stress and depression were measured at 18 weeks and 36 weeks of pregnancy and postnatal stress and depression were measured at six months and 12 months postpartum. Pearson correlations were calculated between all stress and depression timepoints (Figure S1). To assess the accumulation of stress and depression we combined the two prenatal timepoints and the two postnatal timepoints to create a single composite measure for each period. For prenatal stress and depression, continuous measurements at 18 weeks and 36 weeks were z-transformed and collapsed by addition to create continuous composite prenatal stress and prenatal depression variables. For postnatal stress and depression, continuous measurements at 6 months and 12 months were z-transformed and collapsed by addition to create continuous composite postnatal stress and postnatal depression variables. These continuous measures were assessed as the primary exposures of interest in our regression model.

Statistical analysis

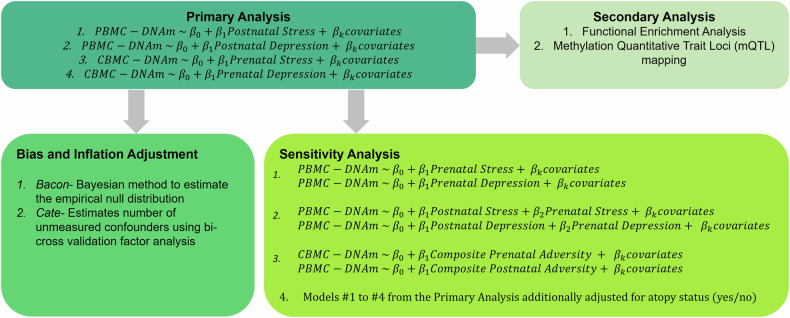

Our analysis pipeline consisted of a primary analysis, bias and inflation adjustment, and a series of sensitivity analyses (Fig. 1). In our primary analyses, we investigated the associations between prenatal stress (z-score) and CBMC-DNAm, prenatal depression (z-score) and CBMC-DNAm, postnatal stress and PBMC-DNAm, and postnatal depression and PBMC-DNAm. Next, we adjusted the estimates from the primary analysis for bias and inflation (e.g., due to unmeasured confounding) to assess the robustness of our primary findings. Additionally, we further explored the relationship between maternal stress and depression on infant DNA methylation at birth and the first year of life using a composite adversity score. Finally, we conducted functional enrichment analyses and methylation quantitative trait loci (mQTL) mapping as secondary analyses for all significant CpG sites to support our findings.

Fig. 1. Overview of the statistical analysis pipeline.

PBMC-DNAm peripheral blood mononuclear cell DNAm, CBMC-DNAm cord blood mononuclear cell DNAm.

Primary analysis: epigenome-wide association studies

We conducted EWAS for the associations between prenatal stress and CBMC-DNAm and prenatal depression and CBMC-DNAm, postnatal stress and PBMC-DNAm, and postnatal depression and PBMC-DNAm. Robust linear regression was performed for each model, in which the stress and depression scores were the predictors of interest and DNAm was the dependent variable. All models were adjusted for the confounders described below. To correct for multiple testing, we applied the Bonferroni threshold (CBMC-DNAm models: 0.05/307566 = 1.6e-07; PBMC-DNAm models: 0.05/309620 = 1.6e-07).

Confounding assessment

Confounding was assessed by constructing directed acyclic graphs (DAGs). DAGs were created for each timepoint: prenatal stress and depression—CBMC-DNAm and postnatal stress and depression—PBMC-DNAm (Figure S2). Potential confounders were selected based on existing literature. All models were adjusted for cell-type proportions and population stratification as represented by the first five genetic principal components, which explained >90% of the variation. Prenatal models were additionally adjusted for prenatal smoking, household income, child sex, maternal age, and study center. Postnatal models were additionally adjusted for postnatal tobacco exposure, prenatal smoking, household income, child sex, birth weight, maternal age, and study center. Prenatal smoking was ascertained at the 18th week of pregnancy and was dichotomized into a binary variable (0 = zero cigarettes smoked per day, 1 = at least 1 cigarette smoked per day). Postnatal tobacco exposure was ascertained at 3, 6, and 12 months postpartum using the average number of cigarettes smoked in the household per day (Table S1). Total postnatal tobacco exposure scores were calculated as the weighted average across the three timepoints.

Bias and inflation adjustment

To adjust for bias due to unmeasured and residual confounding, we implemented the bacon and cate methods for bias adjustment. Bacon adjusts for inflation by utilizing a Bayesian method to estimate the empirical null distribution [59]. Cate adjusts for unmeasured confounding by first estimating the number of unmeasured confounders using bi-cross validation factor analysis and then correcting for this bias [60].

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted four sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of our primary analysis. First, to assess whether effects persist over time and whether associations are robust across different tissues, we investigated the associations between prenatal stress and depression and infant DNA methylation (PBMC-DNAm) at 12 months of age. Second, we adjusted for prenatal stress in the postnatal stress model and for prenatal depression in the postnatal depression model to control for possible confounding by prenatal exposure. Multicollinearity between covariates was evaluated by calculating the variance inflation factors for each predictor (Table S2). Third, to investigate the cumulative effects of stress and depression, we created a composite adversity score for each timepoint. For the prenatal adversity score, prenatal stress and depression were z-transformed and collapsed. Similarly, for the postnatal adversity score, postnatal stress and depression were z-transformed and collapsed. Finally, to assess whether atopy status may confound the relationship between maternal stress/depression and DNAm in this atopy-enriched cohort, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which additionally adjusted our primary EWAS models for atopy status (yes/no).

Functional enrichment analysis

To support our findings, we conducted follow-up analyses for all significant CpG sites. To identify potential biological pathways that may be altered by differential DNAm, we conducted gene ontology functional enrichment analysis using the gometh function of the missMethyl package [61]. We utilized both the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) gene set collections available from the R package. Gometh identifies GO terms and KEGG pathways that are overrepresented among genes containing differentially methylated CpG sites.

Methylation quantitative trait loci (mQTL) mapping

To quantify the potential genetic influence on DNAm levels at significant CpG sites, we identified mQTLs using the GoDMC API [62]. GoDMC is a database comprising of mQTLs from over 32,000 participants from 36 cohorts using the 450K array. We filtered the results by a stringent p-value threshold of 1E-14, as the authors recommended.

Results

Study population characteristics

This analysis sample included 131 infants with DNAm data at birth and 12 months, genotype data, and other relevant covariates, with a subset of 119 infants and 113 infants that had complete cases for the prenatal and postnatal models, respectively (Table 1). This cohort is comprised primarily of children from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, with 45% of the population having a household income greater than $100,000 (CAD). Less than 4% of mothers smoked during pregnancy. The median maternal depression and stress scaled scores were generally low at both antenatal and postpartum timepoints. The median stress scaled score increased postpartum (−0.1 to 0.03), while the median depression scaled score decreased postpartum (−0.4 to −0.6). Most participants experienced low to moderate stress symptoms and no depressive symptoms (Table 1; using thresholds as defined in ref. [63]). However, approximately 1/3 of participants experienced at least moderate stress or mild depressive symptoms at any given timepoint. For example, 39.4% of participants experienced at least mild depressive symptoms at 36 weeks of gestation, with 17.6% having a minimum score of 16, which is the standard threshold to indicate high risk of a clinical depressive disorder [64]. Similarly, 40.4% of participants experienced at least moderate stress symptoms at 36 weeks of gestation.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics for the total population, prenatal sample, and postnatal sample.

| Overall population | Prenatal models | Postnatal models | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 131 | 119 | 113 |

| Child sex (%) | |||

| Male | 75 (57.2%) | 68 (57.1%) | 63 (55.8%) |

| Female | 56 (42.7%) | 51 (42.3%) | 50 (44.2%) |

| Maternal age (yrs) (median [IQR]) | 33 [30, 37] | 33 [30, 37] | 33 [30, 37] |

| Prenatal smoking (%) | |||

| No | 126 (96.2%) | 116 (97.5%) | 110 (97.3%) |

| Yes | 5 (3.8%) | 3 (2.5%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Postnatal tobacco exposure (median [IQR])a | 0 [0, 2.5] | - | 0 [0, 0] |

| Postnatal tobacco exposure yes (%) | |||

| 3 months | 13 (9.9%) | - | 11 (9.7%) |

| 6 months | 13 (9.9%) | - | 12 (10.6%) |

| 12 months | 17 (13.0%) | - | 15 (13.3%) |

| Household Income | |||

| Less than $60,000 | 23 (17.6%) | 23 (17.6%) | 22 (19.5%) |

| Between $60,000 and $100,000 | 37 (28.2%) | 37 (28.2%) | 34 (30.1%) |

| Greater than $100,000 | 59 (45.0%) | 59 (45.0%) | 57 (50.4%) |

| Missing | 12 (9.2%) | ||

| Atopy status (%) | |||

| Case | - | 36 (30.3%) | 34 (30.1%) |

| Control | - | 83 (69.7%) | 79 (69.9%) |

| Birthweight (g) (median [IQR]) | 3629 [3255, 3850] | - | 3620 [3260, 3880] |

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) (%) | 3 (2.4%) | 3 (2.7%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Study center (%) | |||

| Edmonton | 32 (24.4%) | 30 (25.2%) | 30 (26.5%) |

| Toronto | 40 (30.5%) | 36 (30.3%) | 35 (31.0%) |

| Vancouver | 21 (16.0%) | 21 (17.6%) | 20 (17.7%) |

| Winnipeg | 38 (29.0%) | 32 (26.9%) | 28 (24.8%) |

| Cell type proportions (mean (SD)) | |||

| CD8-positive T Cells | - | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.24 (0.07) |

| CD4-positive T cells | - | 0.31 (0.10) | 0.38 (0.07) |

| Natural killer cells | - | 0.08 (0.06) | 0.02 (0.04) |

| B cell | - | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.25 (0.07) |

| Monocytic cell | - | 0.10 (0.07) | 0.11 (0.07) |

| Granulocytesb | - | 0.24 (0.13) | 0.03 (0.03) |

| Nucleated red blood cells | - | 0.09 (0.13) | - |

| Prenatal stress scaled score (median [IQR]) | −0.1 [−1.3, 1.3] | −0.1 [−1.3, 1.0] | - |

| Prenatal PSS raw score (median [IQR]) | |||

| 18 weeks | 11.0 [6.0, 17.0] | 12.0 [6.0, 16.5] | - |

| 36 weeks | 11.0 [7.0, 17.0] | 11.0 [7.0, 17.0] | - |

| Prenatal PSS thresholds (%)c | |||

| 18 weeks | |||

| Low | 81 (61.8%) | 74 (62.2%) | - |

| Moderate | 48 (36.6%) | 44 (40.0%) | - |

| High | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (0.84%) | - |

| 36 weeks | |||

| Low | 78 (59.5%) | 71 (59.7%) | - |

| Moderate | 47 (35.9%) | 44 (37.0%) | - |

| High | 6 (4.6%) | 4 (3.4%) | - |

| Prenatal depression scaled score (median [IQR]) | −0.4 [−1.3, 0.9] | −0.4 [−1.3, 0.9] | - |

| Prenatal CESD raw score (median [IQR])e | |||

| 18 weeks | 6.0 [3.0, 11.0] | 6.0 [3.0, 11.0] | - |

| 36 weeks | 8.0 [3.5, 12.0] | 7.0 [3.5, 12.0] | - |

| Prenatal CESD thresholds (%)d | |||

| 18 weeks | |||

| None | 89 (67.9%) | 82 (68.9%) | - |

| Mild | 25 (19.1%) | 21 (17.6%) | - |

| Moderate | 16 (12.2%) | 16 (13.4%) | - |

| Severe | 1 (0.76%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| 36 weeks | |||

| None | 77 (58.8%) | 72 (60.5%) | - |

| Mild | 29 (22.1%) | 26 (21.8%) | - |

| Moderate | 15 (11.5%) | 13 (10.9%) | - |

| Severe | 10 (7.6%) | 8 (6.7%) | - |

| Postnatal stress scaled score (median [IQR]) | 0.03 [−1.1, 1.1] | - | −0.10 [−3.0, 1.2] |

| Postnatal PSS raw score (median [IQR]) | |||

| 6 months | 11.0 [5.0, 16.0] | - | 10.0 [5.0, 16.0] |

| 12 months | 12.0 [7.0, 17.0] | - | 12.0 [7.0, 17.0] |

| Postnatal PSS thresholds (%)c | |||

| 6 months | |||

| Low | 85 (64.9%) | - | 74 (65.5%) |

| Moderate | 30 (30.5%) | - | 33 (29.2%) |

| High | 6 (4.6%) | - | 6 (5.3%) |

| 1 year | |||

| Low | 77 (58.8%) | - | 66 (58.4%) |

| Moderate | 51 (38.9%) | - | 44 (38.9%) |

| High | 3 (2.3%) | - | 3 (2.7%) |

| Postnatal depression scaled score (median [IQR]) | −0.6 [−1.2, 0.7] | - | −0.6 [−1.3, 0.7] |

| Postnatal CESD raw score (median [IQR]) | |||

| 6 months | 4.0 [1.0, 11.5] | - | 4.0 [1.0, 11.0] |

| 12 months | 6.0 [2.0, 13.0] | - | 5.0 [2.0, 12.0] |

| Postnatal CESD Thresholds (%)d | |||

| 6 months | |||

| None | 93 (71.0%) | - | 80 (70.8%) |

| Mild | 15 (11.5%) | - | 13 (11.5%) |

| Moderate | 14 (10.7%) | - | 12 (10.6%) |

| Severe | 9 (6.9%) | - | 8 (7.1%) |

| 1 year | |||

| None | 88 (67.2%) | - | 77 (68.1%) |

| Mild | 16 (12.2%) | - | 14 (12.4%) |

| Moderate | 14 (10.7%) | - | 17 (15.0%) |

| Severe | 9 (6.9%) | - | 5 (4.4%) |

| Prenatal adversity composite score (median [IQR]) | −0.1 [0.8, 0.6] | −0.09 [−0.8, 0.6] | - |

| Postnatal adversity composite score (median [IQR]) | −0.2 [−0.7, 0.5] | - | −0.3 [−0.7, 0.6] |

aWeighted average of postnatal smoking across all three timepoints. Categorical data of postnatal smoke exposure across the three timepoints can be found in Table S1.

bFor the whole blood reference, only neutrophil cell type estimates are provided.

cPerceived stress scale (PSS) subcategories: low (0–13), moderate (14–26), high (>27).

dCenter for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CESD) subcategories of depressive symptoms: none (0–9), mild (10–15), moderate (16–24), severe (>25).

eThere was a statistically significant difference between the two prenatal timepoints for CESD (t(118) = 3.20, P = 0.002). There was no statistically significant difference between any timepoints for PSS or between the two postnatal timepoints for CESD.

Prenatal stress and depression and DNAm in newborns

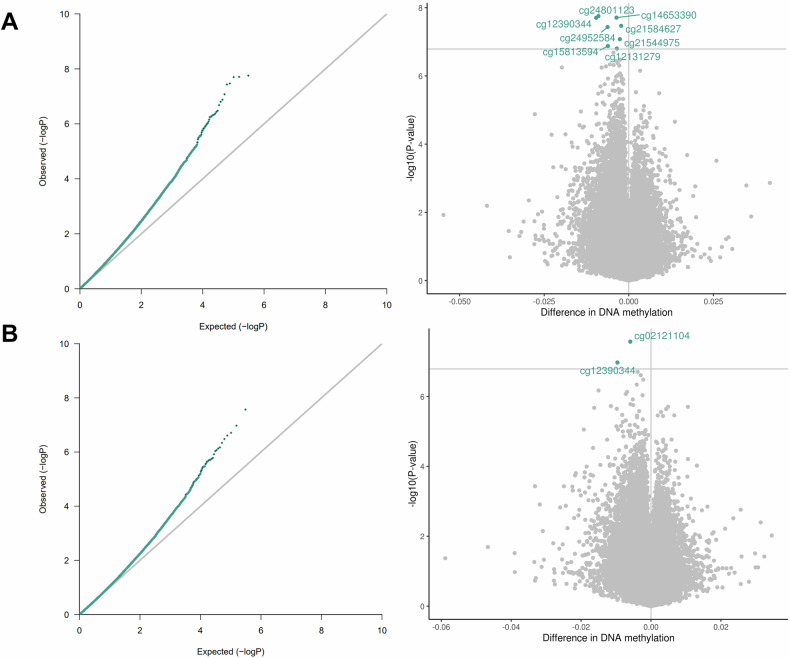

Our analysis pipeline consisted of a primary analysis, bias and inflation adjustment, and a series of sensitivity analyses (Fig. 1). We identified a significant association between prenatal stress and differential newborn CBMC-DNAm at eight CpG sites. Additionally, we identified a significant association between prenatal depression and differential CBMC-DNAm at two CpG sites (Fig. 2; Table 2; Figs. S3 and S4). One CpG site (cg12390344; LAMA3) exhibited significantly differential DNAm for both prenatal stress (β = −9.64E-03, P = 1.98E-08) and prenatal depression (β = −9.61E-03, P = 1.06E-07). Beta estimates for prenatal stress and depression were correlated for CpG sites with p-values less than 5.0E-04 (Figure S5). After adjusting effect estimates for inflation with bacon¸ none of the eight CpG sites in association with prenatal stress remained significant. Only one of two CpG sites remained significant in association with prenatal depression (cg02121104 (EIF2B2)). The remaining CpG sites exhibited suggestive p-values (suggestive threshold = 1E-05) (Table S3; Figure S6). Using cate to adjust for inflation, no CpG sites remained significant or exhibited suggestive p-values for either prenatal stress or depression (Table S3; Figure S7).

Fig. 2. QQ and volcano plots for the associations between 2 A. prenatal stress and CBMC-DNAm (lambda = 1.15) and 2B. prenatal depression and CBMC-DNAm (lambda = 1.01).

Models were adjusted for prenatal smoking, household income, child sex, maternal age, study center, genetic principal components, and cell type proportions. Bonferroni threshold = 1.6E-07.

Table 2.

Effect sizes and p values of significant CpG sites for prenatal stress and depression and CBMC-DNAm in newborns.

| Exposure | CpG (gene) | Mean effect sizea (SE) | P value | Position | Chr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenatal stress | cg12131279 (COL20A1) | −3.53E-03 (6.73E-04) | 1.57E-07 | 61951439 | 20 |

| cg12390344 (LAMA3) | −9.64E-03 (1.72E-03) | 1.98E-08 | 21270348 | 18 | |

| cg14653390 | −3.63E-03 (6.46E-04) | 1.95E-08 | 2930315 | 1 | |

| cg15813594 (EGFLAM) | −6.17E-03 (1.17E-03) | 1.33E-07 | 38445563 | 5 | |

| cg21544975 (GPR133) | −2.64E-03 (4.93E-04) | 8.37E-08 | 131526516 | 12 | |

| cg21584627 | −2.25E-03 (4.07E-04) | 3.40E-08 | 92649211 | 11 | |

| cg24801123 (ADCY1) | −8.98E-03 (1.59E-03) | 1.76E-08 | 45615503 | 7 | |

| cg24952584 (LRRC15) | −6.28E-03 (1.14E-03) | 3.69E-08 | 194080771 | 3 | |

| Prenatal depression | cg02121104 (EIF2B2) | −5.92E-03 (1.06E-03) | 2.69E-08 | 75470314 | 14 |

| cg12390344 (LAMA3) | −9.61E-03 (1.81E-03) | 1.06E-07 | 21270348 | 18 |

aThe mean effect size represents the difference in DNA methylation according to the range of the distribution of β values, which are on a 0–1 scale.

Postnatal stress and depression and DNAm in infants

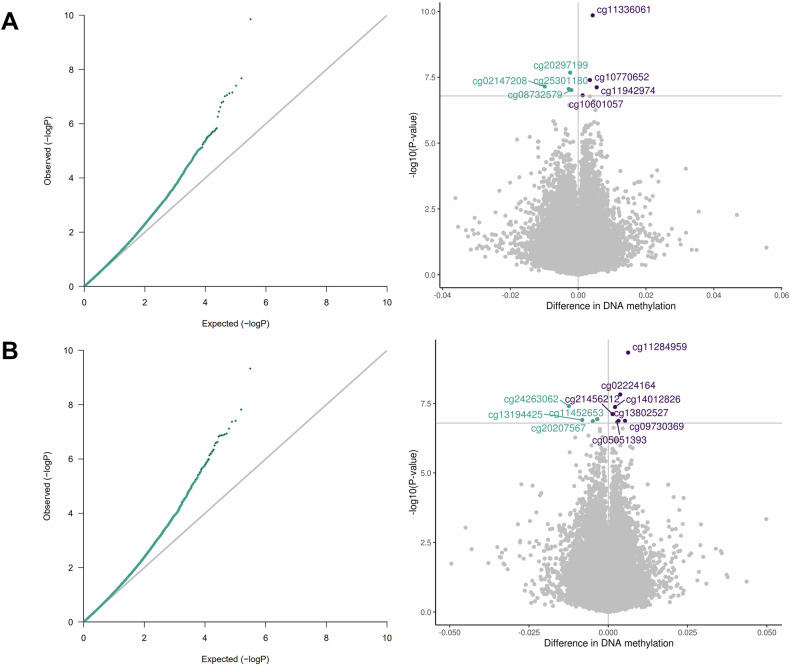

We identified a significant association between postnatal stress and differential child PBMC-DNAm at 12 months of age at eight CpG sites and between postnatal depression and differential PBMC-DNAm at 11 CpG sites (Fig. 3; Table 3; Figs. S8 and S9). There was no overlap between postnatal stress and depression CpG sites. Beta estimates for postnatal stress and depression were correlated for CpG sites with p-values less than 5.0E-04 (Figure S10). After adjusting with bacon, six of the eight CpG sites remained significant in association with postnatal stress and the other two CpG sites exhibited suggestive p-values. For postnatal depression, five of the 11 CpG sites remained significant in association with postnatal depression and the other six CpG sites exhibited suggestive p-values (Table S3; Figure S11). With cate, two CpG sites (cg10770652 (BRD2); cg25301180 (ERC2)) were suggestive in association with postnatal stress and one CpG site (cg05051393 (ASF1A)) was significant in association with postnatal depression (Table S3; Figure S12).

Fig. 3. QQ and volcano plots for the associations between 3 A. postnatal stress and PBMC-DNAm (lambda = 1.02) and 3B. postnatal depression and PBMC-DNAm (lambda = 1.03).

Models were adjusted for prenatal smoking, postnatal tobacco exposure, household income, child sex, maternal age, birth weight, study center, genetic principal components, and cell type proportions. Bonferroni threshold = 1.6E-07. Blue = negative effect estimate; purple = positive effect estimate.

Table 3.

Effect sizes and p values of significant CpG sites for postnatal stress and depression and PBMC-DNAm at 12 months of age.

| Exposure | CpG (gene) | Mean effect sizea (SE) | P value | Position | Chr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postnatal stress | cg02147208 | −9.83E-03 (1.82E-03) | 7.06E-08 | 21662648 | 6 |

| cg08732579 (RILPL1) | −1.98E-03 (3.71E-04) | 9.71E-08 | 123957442 | 12 | |

| cg10601057 (CAB39) | 1.34E-03 (2.55E-04) | 1.54E-07 | 231639268 | 2 | |

| cg10770652 (BRD2) | 3.47E-03 (6.33E-04) | 4.01E-08 | 32945243 | 6 | |

| cg11336061 (RUNX3) | 4.30E-03 (6.70E-04) | 1.40E-10 | 25254149 | 1 | |

| cg11942974 | 5.48E-03 (1.02E-03) | 7.60E-08 | 145092423 | 2 | |

| cg20297199 (BMP4) | −2.35E-03 (4.20E-04) | 2.10E-08 | 54422775 | 14 | |

| cg25301180 (ERC2) | −2.78E-03 (5.19E-04) | 8.79E-08 | 56502091 | 3 | |

| Postnatal depression | cg02224164 (MARS) | 3.77E-03 (6.67E-04) | 1.51E-08 | 57883315 | 12 |

| cg05051393 (ASF1A) | 2.81E-03 (5.35E-04) | 1.51E-07 | 119228846 | 6 | |

| cg09730369 (HYMAI;PLAGL1) | 5.29E-03 (1.00E-03) | 1.34E-07 | 144328421 | 6 | |

| cg11284959 | 6.26E-03 (1.01E-03) | 4.72E-10 | 86205515 | 5 | |

| cg11452653 (PIP5K1C) | −3.49E-03 (6.58E-04) | 1.16E-07 | 3659919 | 19 | |

| cg13194425 (FGF11) | −8.20E-03 (1.55E-03) | 1.25E-07 | 7341936 | 17 | |

| cg13802527 (C9orf80) | 3.23E-03 (6.13E-04) | 1.35E-07 | 115481039 | 9 | |

| cg14012826 (ZNF416) | 2.13E-03 (3.88E-04) | 4.27E-08 | 58083387 | 19 | |

| cg20207567 (NEIL2) | −4.88E-03 (9.26E-04) | 1.38E-07 | 11626510 | 8 | |

| cg21456212 (ATP11A) | 1.34E-03 (2.49E-04) | 7.69E-08 | 113359836 | 13 | |

| cg24263062 (EBF4) | −0.01 (2.26E-03) | 3.97E-08 | 2730191 | 20 |

aThe mean effect size represents the difference in DNA methylation according to the range of the distribution of β values which are on a 0–1 scale.

Sensitivity analyses

Robustness across different exposure timepoints

After investigating whether prenatal stress and depression were associated with CBMC-DNAm in newborns, we additionally assessed whether prenatal stress and depression were also associated with PBMC-DNAm at 12 months of age and whether there was overlap between both timepoints (n = 119). A significant association between prenatal stress and differential PBMC-DNAm was found at four CpG sites and between prenatal depression and differential PBMC-DNAm at eight CpG sites (Table S4; Figure S13). For one PBMC-DNAm CpG site, we found robust associations across both exposure time windows (i.e., pregnancy/prenatal and 1st year of life). CpG site cg09730369 (HYMAI; PLAGL1) exhibited significantly differential PBMC-DNAm for both prenatal depression (β = 7.33E-03, P = 1.79E-12) and postnatal depression (β = 5.29E-03, P = 1.34E-07). Beta estimates across prenatal CBMC-DNAm- and postnatal PBMC-DNAm-associated CpG sites were also correlated (Figures S14 and S15). Additionally, we identified robust associations across prenatal stress and depression and PBMC-DNAm at one CpG site. This CpG site (cg03927037 (ARGHAP20)) exhibited significantly differential PBMC-DNAm for both prenatal stress (β = -3.61E-03, P = 6.52E-08) and prenatal depression (β = −3.56E-03, P = 4.42E-08).

Adjusting for prenatal stress or depression in the postnatal models

Most of the significant CpG sites from the main analysis were still either significant (cg10601057 (CAB39) and cg10770652 (BRD2) for postnatal stress; cg11284959 (intergenic) and cg11452653 (PIP5K1C) for postnatal depression) or at least suggestive (P < 1E-05 for all but two CpG sites) after adjusting for prenatal stress or depression in the postnatal models (Table S5). The VIFs were not indicative of problematic multicollinearity (Table S2), but the results should still be interpreted with caution given the moderately high Pearson correlations between the two timepoints (prenatal and postnatal stress: 0.56; prenatal and postnatal depression: 0.65).

Using a combined adversity score to explore the cumulative effects of stress and depression on DNAm

The correlation between prenatal stress and depression (r = 0.82) and postnatal stress and depression (r = 0.86) was quite high. There was substantial overlap between the combined adversity score models and the separate stress and depression models from the main analysis. Two CpG sites were significantly associated with prenatal adversity and these CpG sites were also significantly associated with prenatal depression (cg12390344 (LAMA3)) and prenatal stress (cg12390344 (LAMA3) and cg21544975 (GPR133)) (Figures S16 and S17, Table S6a). The remaining six CpG sites significantly associated with prenatal stress and one CpG site significantly associated with prenatal depression were at least suggestive in the prenatal adversity score model (all P < 2.85E-05). Seven CpG sites were significantly associated with postnatal adversity and six of these sites were also significantly associated with either postnatal stress (three CpG sites) or postnatal depression (three CpG sites) (Figures S18 and S19, Table S6b). The CpG site that was not significantly associated with postnatal stress or depression was suggestive of an association with postnatal stress and depression (Table S7; cg23102197 (TRIM49); stress: P = 4.64E-06; depression: P = 1.02E-06). The remaining CpG sites were all at least suggestive of an association in the postnatal adversity score model (all P < 7.78E-05). Among overlapping CpG sites, the magnitude of effect was consistently stronger with the combined adversity score in comparison to the individual stress and depression models (Table S6a-S6b).

Assessing atopy status as a potential confounder of the association between prenatal stress and depression and DNAm

Most of the significant CpG sites from the main analysis retained statistical significance after additionally adjusting for atopy status (Table S8). Additionally, all effect sizes were stable, and the genomic inflation factor remained unchanged. For the association between prenatal stress and CBMC-DNAm, five of the eight CpG sites remained statistically significant, with the other three exhibiting suggestive statistical significance (P < 1E-05). Both CpG sites remained statistically significant for the association between prenatal depression and CBMC-DNAm. For the association between postnatal stress and PBMC-DNAm, six of the eight CpG sites remained statistically significant, with the other two exhibiting suggestive statistical significance. Seven of the 11 CpG sites remained statistically significant for the association between postnatal depression and PBMC-DNAm, with the remaining four exhibiting suggestive significance.

Secondary analyses

Functional enrichment analysis

After correction for multiple testing (FDR < 0.05), we did not identify any GO terms or KEGG pathways with an overrepresentation of genes containing significantly, differentially methylated CpGs that would indicate an enriched biological pathway, likely due to the limited number of significant CpG sites identified. The top GO terms and KEGG pathways for each model are included in the supplement (Tables S9a and S9b).

Methylation quantitative trait loci (mQTL) mapping

Of the eight CpG sites identified in association with prenatal stress and CBMC-DNAm, four (cg12390344 (COL20A1), cg15813594 (EGFLAM), cg21584627 (intergenic), cg21584627 (ADCY1)) were associated with at least one mQTL (Table S10). Both CpG sites (cg02121104 (EIF2B2), cg12390344 (LAMA3)) identified in association with prenatal depression were associated with at least one mQTL. Of the eight and 11 PBMC-DNAm CpG sites identified in association with postnatal stress and postnatal depression respectively, four were associated with at least one mQTL for both postnatal stress (cg02147208 (intergenic), cg11336061 (RUNX3), cg20297199 (BMP4), cg25301180 (ERC2)) and depression (cg11452653 (PIP5K1C), cg13194425 (FGF11), cg13802527 (C9orf80), cg20207567 (NEIL2)) (Table S9).

Discussion

In this prospective birth cohort, we identified significant associations between maternal psychosocial stress and differential DNA methylation in the first year of life. Maternal stress and depression were associated with variations in the CBMC and PBMC methylome for both prenatal and postnatal exposures. Additionally, cumulative stress and depression was associated with similar variations in CBMC- and PBMC-DNAm yet demonstrated larger effect estimates. In our primary analyses we identified eight CpGs significantly associated with prenatal stress and two CpGs associated with prenatal depression. Additionally, eight CpGs were significantly associated with postnatal stress and 11 CpGs were associated with postnatal depression.

While maternal mental health has been extensively studied in association with childhood outcomes, investigations of the potential epigenetic mechanisms remain sparse, and findings have been inconsistent. For example, large-scale meta-analyses have not been able to identify replicable evidence of an association due to reasons such as population heterogeneity and differences in stress/depression measures that were used. One meta-analysis investigating the association between prenatal stress (composite stress score calculated from four stress domains) and cord blood DNAm (450K) did not find any evidence of an association (N = 1740) [39]. In contrast, another meta-analysis from the Pregnancy and Childhood Epigenetics (PACE) consortium investigating the association between prenatal stress (composite stress score calculated from five stress domains) and cord blood DNAm (450K and EPIC) did find evidence of an association at five CpG sites (N = 5496) [38]. However, none of the identified CpG sites were significant in our study (Table S11a). Large-scale meta-analyses have yet to be conducted for the associations between prenatal depression, postnatal stress, postnatal depression, and child DNA methylation. Several EWAS of prenatal depression and CBMC-DNAm have identified significant associations, however, none of these associations were replicated in our study [32, 33, 35] (Table S11b). For example, an EWAS that investigated the association between prenatal depression (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II)) and cord blood DNAm (N = 248) in a South African birth cohort identified one significant CpG site after bias-adjustment, however, this was not replicated in our study [33]. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first EWAS investigating the associations between postpartum stress and depression and DNAm and therefore we are unable to compare our results to previous findings for these analyses.

Maternal stress and depression have been hypothesized to exert their effects through multiple, similar biological pathways such as oxidative stress, cortisol transmission through breastmilk, and a dysregulated HPA axis [6, 22, 43]. Such alterations can lead to changes in child neurodevelopment and long-term neurocognitive and psychopathological dysfunction [65]. While maternal stress and depression are hypothesized to share biological pathways, there was no substantial overlap in results between the stress and depression models, despite the high correlation. This suggests that while stress and depression may share some biological pathways, there are also mechanisms through which they uniquely act. Additionally, there was substantial overlap between the combined adversity score models and the individual stress and depression models. The magnitude of effect for overlapping CpG sites was consistently larger among the combined adversity score models both prenatally and postnatally, which may indicate that cumulative stressors have a stronger effect on differential DNAm than either stress or depression alone. Nevertheless, due to the small sample size and high correlation between the stress and depression measures in this cohort, future studies should test the replicatability of these findings and further try to disentangle the biological mechanisms between stress and depression and their cumulative effects.

While the bias-adjustment with bacon was generally robust with our main analysis, adjusting with the cate method yielded no significant or suggestive results. However, with our relatively small sample size and comprehensive list of included covariates cate, which adds additional surrogate variables as covariates, may be slightly conservative with the potential of losing true positive signals. Three CpG sites exhibited robust suggestive or significant p-values across the unadjusted and bias-adjusted estimates for the postnatal models (postnatal stress: cg10770652 (BRD2); cg25301180 (ERC2); postnatal depression: cg05051393 (ASF1A)). BRD2 (bromodomain-containing protein 2) is a transcriptional regulator that plays a role in nucleosome assembly, DNA damage repair, and chromatin remodeling [66]. Mutations in BRD2 have been implicated in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy and there is some evidence from animal models that exposure to maternal stress in combination with other teratogens may be associated with comorbid ASD and epilepsy [67, 68]. Additionally, an epigenome-wide meta-analysis from the PACE consortium (N = 2190) identified differential DNAm at this gene in association with general psychopathology in school-age children [69]. ERC2 (ELKS/RAB6-interacting/CAST family member 2) is a gene that is primarily expressed in the brain and plays a role in regulating neurotransmitter release [70]. A genome-wide association study identified ERC2 as a locus that may induce neuronal excitability in association with febrile seizures [71]. Additionally, differential cord-blood DNAm at ERC2 was associated with ADHD symptoms in school-age children [72]. ASF1A (anti-silencing function 1 A histone chaperone) is a histone chaperone that is involved in chromatin assembly during DNA replication and repair. ASF1A is regulated by tousled-like kinases, a family of serine-threonine kinases that are involved in many regulatory functions including DNA replication and repair, chromatin structure, and genomic and epigenomic stability [73]. Dysfunction in TLK-regulated pathways has been associated with neurodevelopmental disorders such as ASD [74]. Further research is necessary to determine whether differential DNAm at BRD2, ERC2, or ASF1A mediate the relationship between maternal stress and neuropsychiatric outcomes in children.

A few CpG sites overlapped between timepoints and exposures. One CpG site exhibited differential CBMC-DNAm in association with both prenatal stress and depression (cg12390344 (LAMA3)). Additionally, cg03927037 (ARHGAP20) was differentially methylated in PBMC-DNAm in association with both prenatal stress and depression. Finally, cg09730369 (HYMAI; PLAGL1) was differentially methylated in PBMC-DNAm in association with both prenatal and postnatal depression. The gene LAMA3 (laminin subunit alpha 3) is involved in cell growth, motility, and adhesion [75]. It is primarily expressed in the epidermis and pancreatic endocrine cells and has been associated with diseases such as atopic dermatitis and pancreatic cancer [76, 77]. ARHGAP20 (RHO GTPase Activating Protein 20) is involved in neurite outgrowth, differentiation, and maturation, however, not many studies have investigated this gene in association with disease [78]. Overexpression of HYMAI and PLAGL1, maternally imprinted genes, has been strongly associated with 6q24-related transient neonatal diabetes mellitus (6q24-TNDM), a rare type of diabetes that presents at birth, resolves after the first year of life and may recur in adolescence or adulthood [79, 80]. Maternally imprinted genes are genes in which the maternal allele is epigenetically suppressed, and the paternal allele is epigenetically expressed through DNA and histone methylation during gametogenesis [81]. Because only one allele is expressed, imprinted genes are especially vulnerable to mutations and epigenetic changes due to environmental perturbations and can subsequently affect fetal growth and development [82–84]. One study investigated the mediation of maternal prenatal depression and birth weight by cord blood DNAm of PLAGL1 (N = 922) [85]. While no evidence was found of mediation or an association with prenatal depression, they did identify significantly increased methylation (3.6%) at the PLAGL1 differentially methylated region among high birth weight infants. Furthermore, another candidate gene study that investigated the mediation of maternal prenatal stress and preterm birth by cord blood DNAm of PLAGL1 (N = 537) also did not find evidence of mediation or an association with maternal stress at this gene [86]. Larger studies and mediation analyses should be conducted to further investigate potential associations between maternal mental health and differential methylation of HYMAI/PLAGL1 and its potential role in 6q24-TNDM.

Our study has a few limitations. First, we were unable to replicate any of our findings in previous studies due to a lack of comparability across studies. Studies that have been conducted on prenatal depression and stress use various measures of depression and stress and therefore may capture different constructs. Additionally, using cord blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cell tissue which are largely missing granulocytes, rather than unmanipulated cord or peripheral whole blood which most studies typically use may also in part explain challenges in replicating our results. Additionally, while the stress response is physiologically systematic, DNAm changes that may be exerted by maternal stress and depression may not be fully captured by blood tissue alone and could also be exerting effects in another relevant tissue such as brain [87]. Next, this study had a small sample size for both the prenatal (n = 119) and postnatal (n = 113) analyses, which likely limited our statistical power to detect associations. However, only two of the previous studies had sample sizes greater than 1000 [38, 39], indicating the need for future studies to conduct more powered analyses to help validate our and previous study findings. Furthermore, we did not adjust for maternal intake of anti-depressant and anti-anxiety medications, a potentially important confounder. Another potential limitation is the small-magnitude effect sizes, which is common and expected in studies of early-life exposures [88]. However, even small differences in DNAm could cause differences in transcriptional regulation of gene expression [88]. Additionally, many studies of early-life exposures, such as maternal smoking during pregnancy, have found consistently small yet robust effect sizes, suggesting that small differences in DNAm may persist across populations and throughout the life-course [88]. More studies of prenatal mental health exposures need to be conducted to determine the generalizability and biological relevance of these small effect sizes. Lastly, several of our significant CpG sites were associated with at least one known mQTL, an indicator of the genetic influence on DNAm [62]. However, only a proportion of variation in DNAm is due to genetic effects. Further, the joint effect of environmental factors and SNPs may have a larger association with differential DNAm than SNPs alone [89, 90].

Despite these limitations, our study contributes to the sparse literature on maternal mental health and child DNAm. To our knowledge, this is one of the first EWAS to investigate the association between postpartum stress and depression and child DNAm. Additionally, we conducted a bias analysis to assess the effects of unmeasured confounding. Finally, we were able to look at multiple timepoints of stress, depression, and DNAm, which allowed us to investigate the possible effects of maternal mental health on DNAm across the child’s first year of life, a critical window for development.

In summary, these findings suggest that prenatal and postnatal stress and depression are associated with epigenomic changes in the fetus and the first year of life. Differential DNA methylation can lead to differences in gene expression which can subsequently affect downstream biological pathways and child health and developmental outcomes. Larger studies need to be conducted to replicate our findings, to disentangle the biological mechanisms of maternal stress and depression, and to investigate whether differences in DNAm in response to maternal mental health problems increase the risk of adverse birth and childhood outcomes.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the families and children who participated in the CHILD study. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Allergy, Genes, and Environment (AllerGen) Network of Centres of Excellence (NCE) provided core funding for the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development cohort study. AH is supported by the HERCULES Center (NIEHS P30ES019776). MSK was supported by AllerGen NCE (ALLERGEN 12GxE2) and is the Edwin S.H. Leong UBC Healthy Aging Chair—A UBC President’s Excellence Chair. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

SA: formal analysis; interpretation of findings; visualization of findings; methodology; preparation of the original manuscript. BCZ: formal analysis; visualization of findings. MT: conceptualization; methodology. NG, JLM, MJJ: Methodology. ES, TJM, PM, JRB, PS, SET, EC, GEM, MSK: conceptualization; methodology; supervision; funding acquisition. AH: conceptualization; methodology; supervision. All authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All software and packages used for statistical analyses are freely available through the following links: R (V.4.2.1 https://www.r-project.org/); Bioconductor (V.3.15 https://bioconductor.org/news/bioc_3_15_release/); cate (V.1.1.1 https://rdrr.io/cran/cate/) GoDMC (http://www.godmc.org.uk/). The participant data are available under restricted access for the protection of CHILD participants. Access may be obtained by contacting the corresponding author, MSK. The EWAS summary statistics used in this study are available in the EWAS Catalog.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Michael S. Kobor, Anke Hüls.

Contributor Information

Michael S. Kobor, Email: michael.kobor@ubc.ca

Anke Hüls, Email: anke.huels@emory.edu.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-024-03148-8.

References

- 1.Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, Whiteford HA, Harris MG. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gokoel AR, Abdoel Wahid F, Zijlmans WCWR, Shankar A, Hindori-Mohangoo AD, Covert HH et al. Influence of perceived stress on prenatal depression in Surinamese women enrolled in the CCREOH study. Reprod Health 2021;18:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Wadhwa PD, Buss C, Entringer S, Swanson JM. Developmental origins of health and disease: brief history of the approach and current focus on epigenetic mechanisms. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27:358–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrishamcar S, Chen J, Feil D, Kilanowski A, Koen N, Vanker A, et al. DNA methylation as a potential mediator of the association between prenatal tobacco and alcohol exposure and child neurodevelopment in a South African birth cohort. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen GM, Rowcliffe C, Chen J, Vanker A, Koen N, Jones MJ et al. In-utero exposure to indoor air pollution or tobacco smoke and cognitive development in a South African birth cohort study. Sci Total Environ 2022;834:155394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Rakers F, Rupprecht S, Dreiling M, Bergmeier C, Witte OW, Schwab M. Transfer of maternal psychosocial stress to the fetus. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;117:185–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh K, McCormack CA, Webster R, Pinto A, Lee S, Feng T, et al. Maternal prenatal stress phenotypes associate with fetal neurodevelopment and birth outcomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:23996–4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lilliecreutz C, Larén J, Sydsjö G, Josefsson A. Effect of maternal stress during pregnancy on the risk for preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ronald A, Pennell CE, Whitehouse AJO. Prenatal maternal stress associated with ADHD and autistic traits in early childhood. Front Psychol 2011;1:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Fineberg AM, Ellman LM, Schaefer CA, Maxwell SD, Shen L, Chaudhury NH, et al. Fetal exposure to maternal stress and risk for schizophrenia spectrum disorders among offspring: differential influences of fetal sex. Psychiatry Res. 2016;236:91–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Bergh BRH, Mulder EJH, Mennes M, Glover V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2005;29:237–58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Roos A, Wedderburn CJ, Fouche JP, Joshi SH, Narr KL, Woods RP, et al. Prenatal depression exposure alters white matter integrity and neurodevelopment in early childhood. Brain Imaging Behav. 2022;16:1324–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giallo R, Woolhouse H, Gartland D, Hiscock H, Brown S. The emotional–behavioural functioning of children exposed to maternal depressive symptoms across pregnancy and early childhood: a prospective Australian pregnancy cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24:1233–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers A, Obst S, Teague SJ, Rossen L, Spry EA, MacDonald JA, et al. Association between maternal perinatal depression and anxiety and child and adolescent development: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:1082–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingston D, McDonald S, Austin M-P, Tough S. Association between prenatal and postnatal psychological distress and toddler cognitive development: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck CT. The effects of postpartum depression on child development: a meta-analysis. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1998;XII:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. 2014;384:1800–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunham P, Dunham F, Hurshman A, Alexander T. Social contingency effects on subsequent perceptual-cognitive tasks in young infants. Child Dev. 1989;60:1486–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koutra K, Chatzi L, Bagkeris M, Vassilaki M, Bitsios P, Kogevinas M. Antenatal and postnatal maternal mental health as determinants of infant neurodevelopment at 18 months of age in a mother-child cohort (Rhea Study) in Crete, Greece. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:1335–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart S, Field T, del Valle C, Pelaez-Nogueras M. Depressed mothers’ interactions with their one-year-old infants. Infant Behav Dev. 1998;21:519–25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bleker LS, De Rooij SR, Roseboom TJ. Programming effects of prenatal stress on neurodevelopment—the pitfall of introducing a self- fulfilling prophecy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Davis EP, Sandman CA. The timing of prenatal exposure to maternal cortisol and psychosocial stress is associated with human infant cognitive development. Child Dev. 2010;81:131–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uno H, Eisele S, Sakai A, Shelton S, Baker E, DeJesus O, et al. Neurotoxicity of glucocorticoids in the primate brain. Horm Behav. 1994;28:336–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grey KR, Davis EP, Sandman CA, Glynn LM. Human milk cortisol is associated with infant temperament. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1178–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pope CJ, Mazmanian D. Breastfeeding and postpartum depression: an overview and methodological recommendations for future research. Depress Res Treat. 2016;2016:4765310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Bernard-Bonnin A-C. Maternal depression and child development. Paediatr Child Health. 2004;9:575–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ávila JGO, Echeverri I, de Plata CA, Castillo A. Impact of oxidative stress during pregnancy on fetal epigenetic patterns and early origin of vascular diseases. Nutr Rev. 2015;73:12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monk C, Feng T, Lee S, Krupska I, Champagne FA, Tycko B. Distress during pregnancy: epigenetic regulation of placenta glucocorticoid-related genes and fetal neurobehavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:705–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feinberg AP. Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature. 2007;447:433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moosavi A, Ardekani AM. Role of epigenetics in biology and human diseases. Iran Biomed J. 2016;20:246–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cardenas A, Faleschini S, Cortes Hidalgo A, Rifas-Shiman SL, Baccarelli AA, Demeo DL et al. Prenatal maternal antidepressants, anxiety, and depression and offspring DNA methylation: epigenome-wide associations at birth and persistence into early childhood. Clin Epigenetics 2019;11: 10.1186/s13148-019-0653-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Drzymalla E, Gladish N, Koen N, Epstein MP, Kobor MS, Zar HJ et al. Association between maternal depression during pregnancy and newborn DNA methylation. Transl Psychiatry 2021;11: 10.1038/s41398-021-01697-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Viuff AC, Sharp GC, Rai D, Henriksen TB, Pedersen LH, Kyng KJ et al. Maternal depression during pregnancy and cord blood dna methylation: findings from the avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Transl Psychiatry 2018;8. 10.1038/s41398-018-0286-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Non AL, Binder AM, Kubzansky LD, Michels KB, Genome-wide DNA. methylation in neonates exposed to maternal depression, anxiety, or SSRI medication during pregnancy. Epigenetics. 2014;9:964–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polinski KJ, Putnick DL, Robinson SL, Schliep KC, Silver RM, Guan W et al. Periconception and prenatal exposure to maternal perceived stress and cord blood DNA methylation. Epigenet Insights 2022;15: 10.1177/25168657221082045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Sharma R, Frasch MG, Zelgert C, Zimmermann P, Fabre B, Wilson R et al. Maternal–fetal stress and DNA methylation signatures in neonatal saliva: an epigenome-wide association study. Clin Epigenetics 2022;14:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Brunst K, Ruehlmann AK, Sammallahti S, Cortes Hidalgo AP, Bakulski K, Binder E et al. Epigenome-wide meta-analysis of prenatal maternal stressful life events and newborn DNA methylation. 2022; 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1906930/v1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Rijlaarsdam J, Pappa I, Walton E, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Mileva-Seitz VR, Rippe RCA, et al. An epigenome-wide association meta-analysis of prenatal maternal stress in neonates: a model approach for replication. Epigenetics. 2016;11:140–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sosnowski DW, Booth C, York TP, Amstadter AB, Kliewer W. Maternal prenatal stress and infant DNA methylation: a systematic review. Dev Psychobiol. 2018;60:127–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kotsakis Ruehlmann A, Sammallahti S, Cortés Hidalgo AP, Bakulski KM, Binder EB, Campbell ML et al. Epigenome-wide meta-analysis of prenatal maternal stressful life events and newborn DNA methylation. Mol Psychiatry 2023. 10.1038/s41380-023-02010-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Conradt E, Lester BM, Appleton AA, Armstrong DA, Marsit CJ. The roles of DNA methylation of NR3C1 and 11β-HSD2 and exposure to maternal mood disorder in utero on newborn neurobehavior. Epigenetics. 2013;8:1321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, Devlin AM. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics. 2008;3:97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robakis TK, Roth MC, King LS, Humphreys KL, Ho M, Zhang X et al. Maternal attachment insecurity, maltreatment history, and depressive symptoms are associated with broad DNA methylation signatures in infants. Mol Psychiatry 2022; 10.1038/s41380-022-01592-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Lapato DM, Roberson-Nay R, Kirkpatrick RM, Webb BT, York TP, Kinser PA. DNA methylation associated with postpartum depressive symptoms overlaps findings from a genome-wide association meta-analysis of depression. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Subbarao P, Anand SS, Becker AB, Befus AD, Brauer M, Brook JR, et al. The Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) Study: examining developmental origins of allergy and asthma. Thorax. 2015;70:998–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moraes TJ, Lefebvre DL, Chooniedass R, Becker AB, Brook JR, Denburg J, et al. The Canadian healthy infant longitudinal development birth cohort study: biological samples and biobanking. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015;29:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolsun KP, Lee S, MacIsaac JL, Subbarao P, Moraes TJ, Mandhane PJ et al. DNA methylation is not associated with sensitization to or dietary introduction of highly allergenic foods in a subset of the CHILD cohort at age 1 year. J Allergy Clin Immunol Glob 2023;2: 10.1016/j.jacig.2023.100130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Sbihi H, Jones MJ, MacIsaac JL, Brauer M, Allen RW, Sears MR, et al. Prenatal exposure to traffic-related air pollution, the gestational epigenetic clock, and risk of early-life allergic sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:1727–9.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Price ME, Cotton AM, Lam LL, Farré P, Emberly E, Brown CJ et al. Additional annotation enhances potential for biologically-relevant analysis of the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array. Epigenetics Chromatin 2013;6: 10.1186/1756-8935-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Edgar RD, Jones MJ, Robinson WP, Kobor MS. An empirically driven data reduction method on the human 450 K methylation array to remove tissue specific non-variable CpGs. Clin Epigenet 2017;9: 10.1186/s13148-017-0320-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Du P, Kibbe WA, Lin SM. lumi: a pipeline for processing Illumina microarray. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1547–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teschendorff AE, Marabita F, Lechner M, Bartlett T, Tegner J, Gomez-Cabrero D, et al. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:189–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen C, Grennan K, Badner J, Zhang D, Gershon E, Jin L et al. Removing batch effects in analysis of expression microarray data: An evaluation of six batch adjustment methods. PLoS One 2011;6: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Gervin K, Salas LA, Bakulski KM, van Zelm MC, Koestler DC, Wiencke JK, et al. Systematic evaluation and validation of reference and library selection methods for deconvolution of cord blood DNA methylation data. Clin Epigenet. 2019;11:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salas LA, Koestler DC, Butler RA, Hansen HM, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT et al. An optimized library for reference-based deconvolution of whole-blood biospecimens assayed using the Illumina HumanMethylationEPIC BeadArray. Genome Biol 2018;19: 10.1186/s13059-018-1448-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Iterson M, van Zwet EW, the BIOS Consortium. Controlling bias and inflation in epigenome- and transcriptome-wide association studies using the empirical null distribution. Genome Biol 2017;18:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Wang J, Zhao Q, Hastie T, Owen AB. Confounder adjustment in multiple hypothesis testing. Ann Stat. 2017;45:1863–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phipson B, Maksimovic J, Oshlack A. MissMethyl: an R package for analyzing data from Illumina’s HumanMethylation450 platform. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:286–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Min JL, Hemani G, Hannon E, Dekkers KF, Castillo-Fernandez J, Luijk R, et al. Genomic and phenotypic insights from an atlas of genetic effects on DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2021;53:1311–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moon JR, Huh J, Song J, Kang I-S, Park SW, Chang S-A, et al. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale is an adequate screening instrument for depression and anxiety disorder in adults with congential heart disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chow A, Dharma C, Chen E, Mandhane PJ, Turvey SE, Elliott SJ, et al. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and perceived stress from pregnancy to the postnatal period among canadian women: impact of employment and immigration. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:S197–S204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu Y, De Asis-Cruz J, Limperopoulos C. Brain structural and functional outcomes in the offspring of women experiencing psychological distress during pregnancy. Mol Psychiatry 2024;29:2223–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Cheung KL, Kim C, Zhou MM. The Functions of BET proteins in gene transcription of biology and diseases. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:728777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Pathak S, Miller J, Morris EC, Stewart WCL, Greenberg DA. DNA methylation of the BRD2 promoter is associated with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy in Caucasians. Epilepsia. 2018;59:1011–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bercum FM, Rodgers KM, Benison AM, Smith ZZ, Taylor J, Kornreich E, et al. Maternal stress combined with terbutaline leads to comorbid autistic-like behavior and epilepsy in a rat model. J Neurosci. 2015;35:15894–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rijlaarsdam J, Cosin-Tomas M, Schellhas L, Abrishamcar S, Malmberg A, Neumann A, et al. DNA methylation and general psychopathology in childhood: an epigenome-wide meta-analysis from the PACE consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28:1128–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kiyonaka S, Nakajima H, Takada Y, Hida Y, Yoshioka T, Hagiwara A, et al. Physical and functional interaction of the active zone protein CAST/ERC2 and the β-subunit of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel. J Biochem. 2012;152:149–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Skotte L, Fadista J, Bybjerg-Grauholm J, Appadurai V, Hildebrand MS, Hansen TF, et al. Genome-wide association study of febrile seizures implicates fever response and neuronal excitability genes. Brain. 2022;145:555–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Neumann A, Walton E, Alemany S, Cecil C, González JR, Jima DD et al. Association between DNA methylation and ADHD symptoms from birth to school age: a prospective meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry 2020;10:398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Gao Y, Gan H, Lou Z, Zhang Z. Asf1a resolves bivalent chromatin domains for the induction of lineage-specific genes during mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E6162–E6171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Segura-Bayona S, Stracker TH. The Tousled-like kinases regulate genome and epigenome stability: implications in development and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76:3827–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Feng L, Huang Y, Zhang W, Li L. LAMA3 DNA methylation and transcriptome changes associated with chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2021;14:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tian C, Li X, Ge C. High expression of LAMA3/AC245041.2 gene pair associated with KRAS mutation and poor survival in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a comprehensive TCGA analysis. Mol Med. 2021;27:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stemmler S, Parwez Q, Petrasch-Parwez E, Epplen JT, Hoffjan S. Association of variation in the LAMA3 gene, encoding the alpha-chain of laminin 5, with atopic dermatitis in a German case-control cohort. BMC Dermatol. 2014;14:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamada T, Sakisaka T, Hisata S, Baba T., Takai Y. RA-RhoGAP, rap-activated Rho GTPase-activating protein implicated in neurite outgrowth through Rho. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33026–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mackay DJG, Temple IK. Transient neonatal diabetes mellitus type 1. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2010;154C:335–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Temple IK, Mackay DJ. Diabetes Mellitus, 6q24-related transient neonatal. University of Washington: Seattle, 2005. [PubMed]

- 81.Lobo I. Genomic imprinting and patterns of disease inheritance. Nat Educ. 2008;1:66. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Crespi BJ. Why and how imprinted genes drive fetal programming. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;10:940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Kappil M, Lambertini L, Chen J. Environmental influences on genomic imprinting. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015;2:155–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Robles-Matos N, Artis T, Simmons RA, Bartolomei MS. Environmental exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals influences genomic imprinting, growth, and metabolism. Genes (Basel). 2021;12:1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Liu Y, Murphy SK, Murtha AP, Fuemmeler BF, Schildkraut J, Huang Z, et al. Depression in pregnancy, infant birth weight and DNA methylation of imprint regulatory elements. Epigenetics. 2012;7:735–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vidal AC, Neelon SEB, Liu Y, Tuli AM, Fuemmeler BF, Hoyo C, et al. Maternal stress, preterm birth, and DNA methylation at imprint regulatory sequences in humans. Genet Epigenet. 2014;1:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bakulski KM, Halladay A, Hu VW, Mill J, Fallin MD. Epigenetic research in neuropsychiatric disorders: the “tissue issue”. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2016;3:264–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Breton CV, Marsit CJ, Faustman E, Nadeau K, Goodrich JM, Dolinoy DC, et al. Small-magnitude effect sizes in epigenetic end points are important in children’s environmental health studies: the children’s environmental health and disease prevention research center’s epigenetics working group. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:511–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Czamara D, Eraslan G, Page CM, Lahti J, Lahti-Pulkkinen M, Hämäläinen E, et al. Integrated analysis of environmental and genetic influences on cord blood DNA methylation in new-borns. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yuan V, Robinson WP. Epigenetics in development. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:1144–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All software and packages used for statistical analyses are freely available through the following links: R (V.4.2.1 https://www.r-project.org/); Bioconductor (V.3.15 https://bioconductor.org/news/bioc_3_15_release/); cate (V.1.1.1 https://rdrr.io/cran/cate/) GoDMC (http://www.godmc.org.uk/). The participant data are available under restricted access for the protection of CHILD participants. Access may be obtained by contacting the corresponding author, MSK. The EWAS summary statistics used in this study are available in the EWAS Catalog.