Abstract

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) airway disease is characterized by impaired mucociliary clearance, chronic, polymicrobial infections and robust, neutrophil-dominated inflammation. Pulmonary disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in people with CF and is due to progressive airflow obstruction and ultimately respiratory failure. One of the earliest abnormalities in CF airway disease is the recruitment of neutrophils to the lungs. Neutrophil activation leads to the release of their intracellular content, including neutrophil elastase (NE), that damages lung tissues in CF. Our goal is to characterize a known bacterial NE inhibitor, ecotin, in the CF airway environment. Our results indicate that ecotins cloned from four Gram-negative bacterial species (Campylobacter rectus, Campylobacter showae, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) inhibit NE activity in CF sputum samples in a dose-dependent manner. Although we observed differences in the NE-inhibitory activity of the tested ecotins with the Campylobacter homologs being the most effective in NE inhibition in CF sputa, none of the ecotins impaired the ability of human neutrophils to kill major CF respiratory pathogens, P. aeruginosa or S. aureus, in vitro. Overall, we demonstrate that bacterial ecotins inhibit NE activity in CF sputa without compromising bacterial killing by neutrophils.

1. Introduction

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) is a recessive genetic disease affecting about 80,000 people worldwide [1]. Severe lung disease causes the majority of the morbidity and mortality in people with CF (PwCF). Progression of CF lung disease has been primarily associated with chronic inflammation, partially mediated by neutrophils, and with the persistence of polymicrobial infections [2]. Persistent inflammatory signals in the CF airways cause activation of recruited neutrophils which contributes to lung tissue damage overtime [3]. Neutrophils contain many antimicrobial proteins and enzymes capable of limiting infections. In general, neutrophils kill and trap microbes in two major ways, via the intracellular mechanism of phagocytosis and the extracellular mechanism of neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation [[4], [5], [6]]. In CF, neutrophils accumulate in large numbers in the airways and release their intracellular cargo which has been associated with tissue damage and lung disease progression. Several studies underscore the importance of neutrophils and neutrophil-derived products driving CF airway disease progression. For example, the number of neutrophils and the levels of DNA, myeloperoxidase (MPO), NE, and neutrophil chemoattractants (IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1β) in the sputum all correlate with CF lung disease severity [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]].

Neutrophil elastase (NE) is a serine protease that is a requisite for the normal antimicrobial function of neutrophils [19]. Extracellular NE degrades interstitial collagen fibers enabling neutrophil cell migration, while intracellular NE kills bacteria within the phagosome [19]. In CF, however, NE is released from neutrophils in the airways in large quantities, causes harm by targeting host proteins within the lung tissue, irreversibly damages the airways over time, and is one of the several host components that are thought to drive chronic inflammation and lung disease progression [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24]]. NE is one of the amplest host enzymes found in the CF lung that degrades elastin, fibronectin, and collagen [25]. NE has also been shown to impair other host defenses by injuring bronchial epithelial cells and destroying the lung extracellular matrix [23,26]. The chronic release of NE by neutrophils causes airway remodeling contributing to worsened lung damage and function in PwCF [23,27]. NE is elevated in the bronchoalveolar fluid of CF infants and toddlers, and is the best predictor of future bronchieactasis [28,29].

There are only a few clinical studies testing NE inhibitors in CF and the results are variable. For example, AZD9668, a reversible and selective NE inhibitor, significantly reduced sputum inflammatory biomarkers in PwCF, but failed to decrease sputum neutrophil counts and NE activity, and did not improve lung function [30]. Another phase II clinical trial using inhaled alpha-1-antitrypsin in CF showed no impact on lung function, but did diminish free NE activity, neutrophil counts, P. aeruginosa loads and IL-8 levels [31]. Thus, the potential efficacy of NE inhibitors in CF still needs to be explored, since it remains insufficiently clear whether the recently developed highly effective modulator therapies (HEMT) are effective in controlling the inflammatory response and whether HEMTs would require adjunct, anti-inflammatory therapies in the future [32].

Bacteria have also evolved mechanisms to resist the antimicrobial properties of neutrophils. Specifically, Gram-negative bacteria have developed strategies to evade harm by immune cell-derived serine proteases, such as NE, through the production of a protein called ecotin [33,34]. Ecotin was first described in E. coli as a protease inhibitor [34,35]. Ecotin is a small, homodimeric protein of approximately 38 kDa that is resistant to boiling and stable at pH 1.0, demonstrating exceptional stability [36]. In bacteria expressing ecotin, the protein translocates to the periplasmic space and protects the bacterium from host proteases. Since its first discovery in E. coli, ecotin homologs have been observed in over 300 organisms including P. aeruginosa, which is a dominant pathogen in CF airways [34,[37], [38], [39]]. We recently identified and characterized ecotin homologs in Campylobacter rectus and Campylobacter showae and showed that they inhibit free or NET-bound NE in a dose-dependent manner [37]. Our previous research showed that recombinantly expressed ecotins cloned from two Campylobacter species, C. rectus and C. showae, and cloned from E. coli were able to inhibit human NE [37]. In this study we also recombinantly expressed the P. aeruginosa ecotin. The objective of this study was to determine whether ecotins from four different, Gram-negative bacteria are capable of inhibiting NE enzymatic activity in CF airway samples.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Human subjects

All human subject studies were performed according to the guidelines of the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. Healthy (non-CF) human subjects were recruited at the University of Georgia (UGA) and provided informed consent for blood donation for neutrophil isolation according to the IRB protocol UGA# 2012-10769-06. Based on self-report, the healthy volunteers donating blood in our study did not suffer from CF, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, tuberculosis, asthma, diabetes or acute airway infections. Volunteers of ages between 18 and 50 years and of both sexes were recruited. Pregnant women were excluded from the study. The vaccination status of the volunteers was not considered as one of the exclusion/inclusion criteria.

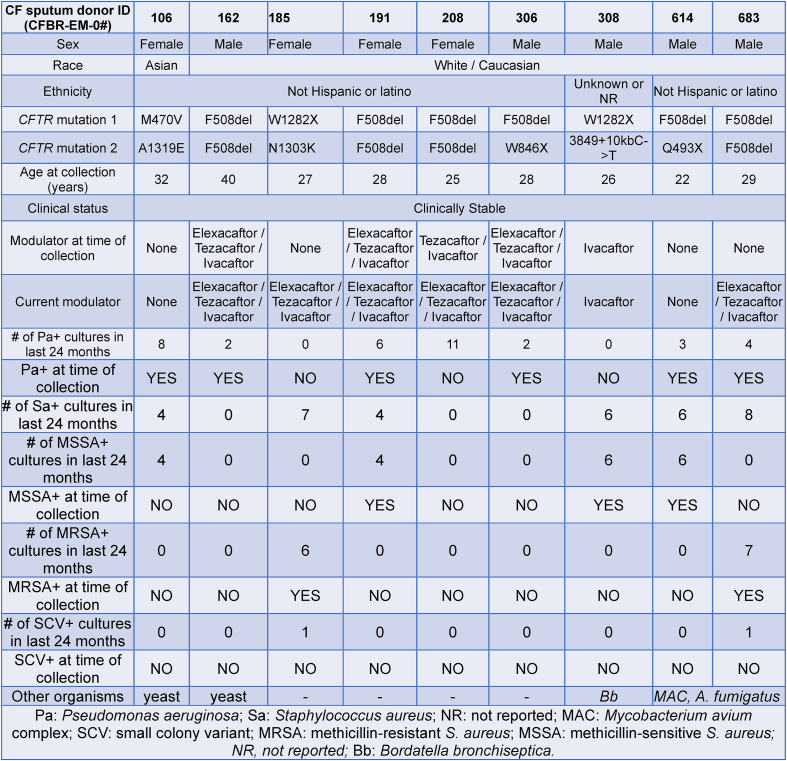

2.2. CF subjects

CF subjects were recruited at the Adult CF Clinic at the Children's Healthcare of Atlanta and Emory University CF Care Center (see Table 1). These patients provided informed consent to obtain sputum samples (IRB00042577). All human studies involving sputum collection from CF subjects were approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and were in accordance with institutional guidelines. CF diagnosis was confirmed by pilocarpine iontophoresis sweat testing and/or CFTR gene mutation analysis to show the presence of two disease causing mutations. CF subjects were selected for sputum collection only if they were clinically stable (no pulmonary exacerbations at the time of specimen collection) and on no new medications within the previous three weeks of the study visit. The vaccination status of the volunteers was not considered as one of the exclusion/inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the CF sputum donors participating in this study.

2.3. Sputum processing

Expectorated sputum samples were processed as described earlier [40]. The sputa were kept at 4 °C throughout the processing procedure. The sputum was weighed and for every 1.0 g of sputum, 3 mL of cold PBS-EDTA (1xPBS with 5 mM EDTA) were added. Sputum was then repeatedly passed through a sterile 18-gauge needle for homogenization and then centrifuged at 800×g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet the cells. To ensure removal of cells, mucus, and bacteria, the sputum supernatant was transferred into new tubes and centrifuged at 3000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The clear sputum supernatants were stored at −80 °C until further use.

2.4. “Cystic Fibrosis (CF) sputum model”

Our established CF sputum model was used to mimic the CF airway environment [40,41]. Briefly, sputum supernatants obtained from five PwCF were pooled and PMNs were exposed to 30 % (v/v) CF sputum cocktail for 3.5 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, PMNs were washed twice with 1 x HBSS and resuspended in “assay medium” (1 x HBSS, 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose, and 1 % (v/v) autologous serum). The CF sputum cocktail was also diluted in “assay medium” to reach the desired 30 % concentration. Due to the washes, the CF sputum did not get in direct touch with bacteria.

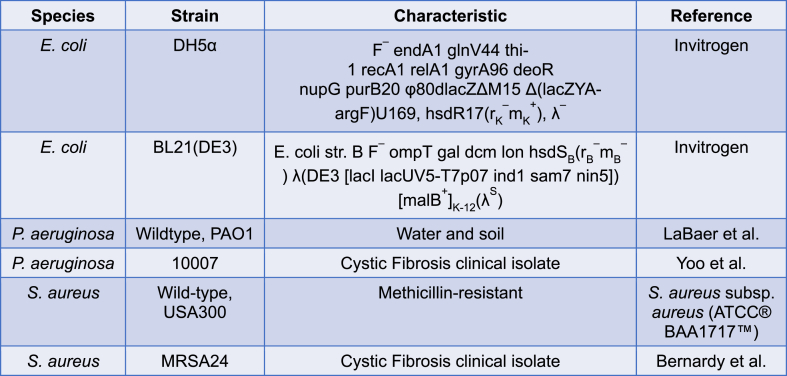

2.5. Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions for ecotin expression

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. E. coli was grown on Luria Bertani (LB) agar or in LB broth at 37 °C with shaking overnight. Expression of ecotin from E. coli, C. rectus and C. showae used in this study has been described in our prior publication (34). The expression plasmid of ecotin from P. aeruginosa was constructed as follows. The full length ecotin gene was amplified from genomic DNA of P. aeruginosa PAO1 with oligonucleotides PAO1-eco-NdeI-F-(5′-AAGGAGATATACATATGAAAGCACTACTGATCGCCGCCGGCGTTG-3′) and PAO1-eco-SalI-R-(5′-ATACTCGTGTCGACTTCGCTGACCGCTTTCTCGACCTTTTCG-3′), introducing NdeI and SalI restriction sites, respectively. The obtained PCR product was inserted into plasmid pET24b after restriction with NdeI and SalI and candidate plasmids isolated from colonies obtained after transformation of the ligation reaction in E. coli DH5alpha were analyzed by restriction digests. One positive clone that carries the PAO1 ecotin-His6 gene under the control of the T7 promoter was used as a template to amplify the PAO1 ecotin-His6 encoding sequence using oligonucleotides ecotin-temp-pET22b-BamHI-F (5′-ATATGGATCCGGCGTAGAGGATCGAGATCTCG-3) and ecotin-temp-pET22b-SalI-R (5′-TAGCAGTCGACTCAGCTTCCTTTCGGGCTTTGTTAGC-3′), and was subsequently inserted into the EcoRV restriction site on plasmid pBBR1-MCS4. One candidate plasmid that expresses the PAO1 ecotin under the control of the constitutive pLac promoter was transferred into the overexpression strain E. coli BL21 eco:kan. Expression, purification and serine protease activity were confirmed for each ecotin from P. aeruginosa, E. coli, C. rectus and C. showae in a trypsin inhibition assay described previously [37].

Table 2.

Bacterial strains used in this study.

2.6. Neutrophil elastase activity assay

NE enzymatic activity in CF sputum supernatants was measured with the NE activity kit following the manufacturer's protocol (Cayman Chemical, cat #600610). CF sputum was diluted to a measurable range based upon the NE bulk standard that contained 18 U/ml human NE activity. The standard curve was generated with human NE ranging from 0 mU/ml to 10 mU/ml in NE activity assay buffer. CF sputa and standards were added to a 96-well fluorometric microplate and ecotin was added to the CF sputum at varying doses. Ecotins from C. rectus, C. showae, and E. coli were added at a range from 0 to 1666.67 nM, whereas ecotin from P. aeruginosa was added at a range from 0 to 555.56 nM due to its limited availability. Sivelestat (MedChemExpress, cat#127373-66-4), a known NE inhibitor [31,36,[42], [43], [44], [45]], was used as a reference. The NE-specific substrate (Z-Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala) 2Rh110 is selectively cleaved by NE to yield the highly fluorescent compound R110. Fluorescence was read at 485/525 nm (excitation/emission wavelengths) every 2 min for 2 h in a Varioskan Flash™ fluorescent microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). For analysis, the average relative fluorescence unit (RFU) values were recorded for each well (standard and unknown samples), and the blank was subtracted. NE activity (mU/ml) was calculated based upon the equation generated with the help of the standard curve: NE (mU/ml) = [(RFU – y-intercept)/slope] x dilution factor.

2.7. Bacterial killing

Bacterial killing measurement of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus by neutrophils was performed with a reference strain and a CF clinical isolate for each bacterial species as shown in Table 2. The P. aeruginosa strains were streaked on Pseudomonas isolation agar, while the S. aureus bacterial strains were streaked on blood agar (TSA II, 5 % sheep blood), and both were grown at 37 °C overnight. Colonies were picked the following day and grown in LB broth for about 3 h with shaking at 37 °C. The bacteria were collected, washed twice with 1xHanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) and absorbance was measured at 600 nm in a 96-well microplate using the Varioskan Flash™ microplate photometer. As previously published, optical density of 0.6 of the bacterial suspension corresponds to 1.0 × 109 CFU/ml (43). The dose of bacteria was confirmed in each experiment with serial dilution and colony counting. Prior to adding bacteria to neutrophils, bacteria were opsonized with 10 % (v/v) autologous serum of the neutrophil donor for 20 min at 37 °C. After opsonization, serum was removed from bacteria by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 min and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in assay medium [40,46,47].

Neutrophils were isolated from the blood of healthy controls as previously described and resuspended in assay medium (at 1 × 107 cells/ml) [40,46,47]. Next, neutrophils were either left untreated or treated with 555.56 nM of ecotin, and bacteria were added simultaneously to neutrophils at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 (1:1). Neutrophils were then incubated at 37 °C with shaking every 2–3 min to ensure proper mixing of bacteria and neutrophils. After 30 min of incubation, neutrophils were lysed in saponin (1 mg/ml in 1xHBSS) for 5 min and diluted 100-fold into 1xHBSS. For a bacterial input control, bacteria were added to neutrophils and neutrophils were immediately lysed to enumerate bacteria added at time = 0 (input). Serial dilutions of each bacterial strain were generated in LB broth in each experiment to produce standard curves. Bacterial samples were placed in a 384-well microplate and bacterial growth was measured over time in the Varioskan Flash™ microplate photometer at 600 nm absorbance every 4 min for 16 h with constant temperature (37 °C) and shaking. For quantification of bacterial killing by neutrophils, growth curves for each strain were generated; the initial bacterial concentrations in each sample were determined; and bacterial killing was assessed as the decrease in surviving bacteria over time as described [40,46]. To measure the effect of ecotin on bacterial survival/growth, 555.56 nM of each ecotin was added to 1 × 107 CFU/ml bacteria (that corresponds to the concentration of bacteria when co-cultured with neutrophils) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. These samples were diluted 100-fold and added to LB broth on the 384-well microplate – in the exact same manner as the neutrophil-containing samples. Rare experiments in which baseline killing was below 20 % were excluded.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Results for assessing inhibition of NE by ecotin in the CF sputa were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparison test (comparison of each ecotin concentration to untreated controls). Results for assessing the differences in inhibition by each ecotin between each CF sputum sample was analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparison test. The assessment of ecotin on neutrophil-mediated bacterial killing was analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparison test. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Statistically significant differences were considered as ns, not significant; ∗, p < 0.05; ∗∗, p < 0.01; ∗∗∗, p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗, p < 0.0001. All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 9.01 for Windows software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

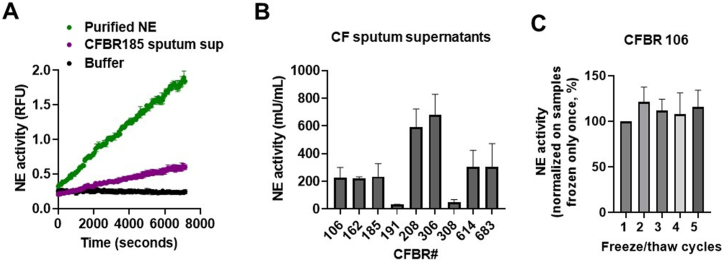

3.1. Neutrophil elastase enzymatic activities vary in CF sputa

To assess whether we can detect NE activities in CF sputa, sputum supernatants from nine PwCF (Table 1.) were assessed for NE activity (mU/ml) using a fluorescent microplate-based kit as done previously [48,49]. Fig. 1A shows representative kinetics of NE enzymatic activities in mU/ml in one CF sputum sample, in purified NE solution, and in assay buffer (control, without NE), over a time period of 2 h. NE activity is evidenced by the rise in fluorescence representing the increased concentration of the fluorescent NE cleavage product of 2Rh110 (Fig. 1A). Fig. 1B shows the comparison of NE activity levels observed in the sputum supernatants of nine PwCF. Freeze/thaw cycles (≤5) had no effect on NE activity in CF sputum (Fig. 1C). Overall, this demonstrates a certain range of variability of NE activities present in the sputa from PwCF.

Fig. 1.

Neutrophil elastase (NE) activities in sputum supernatants of PwCF. NE enzymatic activity measurements were performed in CF sputum supernatants obtained from nine PwCF using an NE fluorometric assay kit. Fluorescence was measured in a microplate reader (Ex/Em = 485/525 nm). (A) A representative kinetic curve of NE activity obtained using the CFBR185 patient sputum. Relative fluorescence units (RFU) of NE activity are shown in diluted (1/500) CF sputum over time compared to purified NE and assay buffer alone. The mean ± S.D of (n = 3) samples is shown (B) NE activity in each CF sputum sample. (C) The sputum supernatant obtained from CFBR 106 patient was frozen and thawed at the indicated times (freeze/thaw cycles, X-axis) and NE activity was measured. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. of (n = 2–16) samples. RFU, relative fluorescent unit.

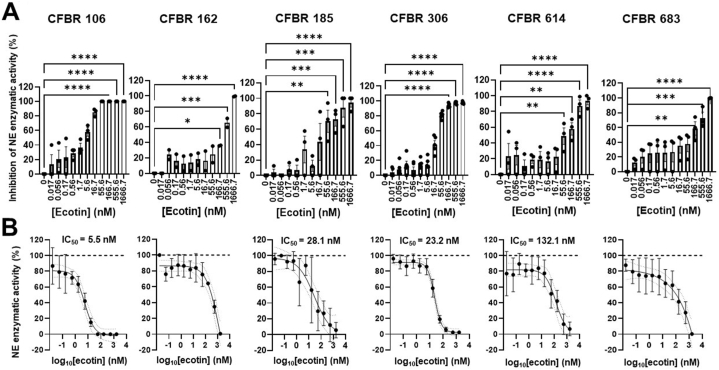

3.2. C. rectus ecotin inhibits NE in CF sputa

Our primary goal was to determine whether ecotin can inhibit NE present in CF sputa. We have previously cloned and expressed recombinant ecotins from three Gram-negative bacteria: Campylobacter rectus, C. showae and E. coli [37]. All three ecotins inhibited the enzymatic activities of purified human NE in a dose-dependent and identical fashion under the conditions tested [37]. Based on these observations, we planned to test these recombinant ecotins for their potential NE-inhibitory effect in CF sputa. First, we tested ecotin isolated from C. rectus, a bacterium that is typically present in the human oral microbiome and can cause oral abscesses, but is not associated with CF lung disease [50]. C. rectus ecotin was added to the sputum supernatants of six CF subjects in increasing doses (0–1.67 μM) and percent inhibition of NE activity was determined relative to the ecotin-free sputum. C. rectus ecotin significantly inhibited NE enzymatic activities in all six CF sputa in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Sivelestat, a known NE inhibitor (5 mM), yielded complete inhibition of NE activities in all CF sputum samples tested (data not shown) [51]. NE-inhibitory curves could be generated (Fig. 2B) and allowed us to determine 50 percent inhibitory concentration values (IC50 values) for C. rectus ecotin in four out of six CF samples. IC50 values of C. rectus ecotin demonstrated a relatively wide range (5.5–132.1 nM) as indicated in Fig. 2B. IC50 values could not be calculated in the case of two CF samples (CFBR 162 and 683) due to wide 95 % confidence intervals. Altogether, C. rectus ecotin can achieve complete inhibition of NE activity in CF sputum and the dose needed for 50 % inhibition varies from subject to subject, but was in the nM range.

Fig. 2.

C. rectus ecotin inhibits neutrophil elastase activity in CF sputa. (A)C. rectus ecotin was added in increasing concentrations (0–1666.7 nM) to the sputum supernatants of six PwCF and NE activity was measured. Percent inhibition of NE activity for each sputum sample was determined by dividing NE activity (mU/ml) at each dose of ecotin with NE activity without ecotin (represented as 0 nM on the graph). Mean ± S.E.M. of (n = 2–5) samples is shown. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparison test. (B) Summary graphs for the IC50 values (nM) for C. rectus ecotin on its inhibitory effect of NE activity, represented as percent of untreated CF sputum. IC50 values for each CF sputum were determined by interpolation of standard curves, Sigmoidal, 4 PL, X is log(concentration) with 95 % confidence interval bands. Mean ± S.D. of (n = 2–5) is shown. Statistical differences were considered as ∗, p < 0.05; ∗∗, p < 0.01; ∗∗∗, p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗, p < 0.0001.

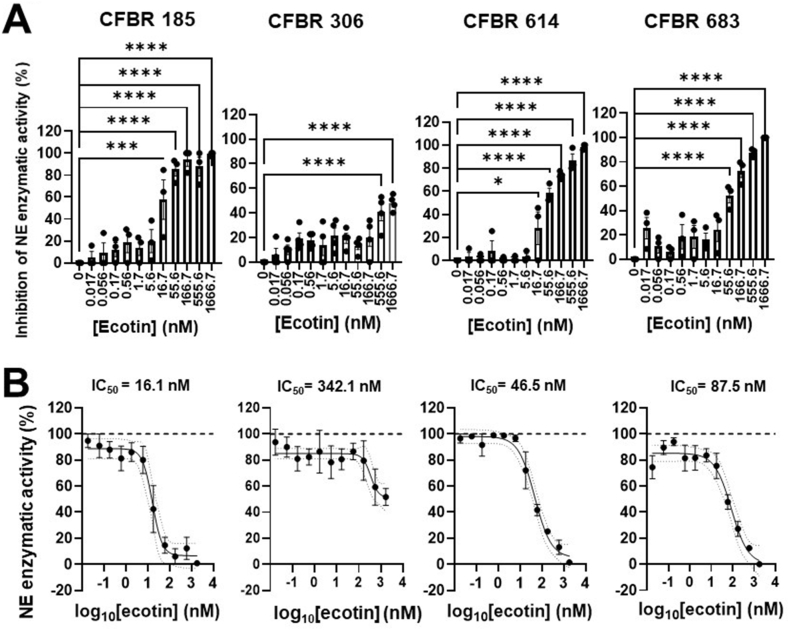

3.3. C. showae ecotin inhibits NE in CF sputa

C. showae is a species closely related to C. rectus also producing ecotin that inhibits the activities of human NE in a similar manner in vitro [37,52]. We tested whether C. showae ecotin is a potent inhibitor of NE in CF sputa. C. showae ecotin also significantly inhibited NE enzymatic activities in the sputa collected from the indicated four PwCF (Fig. 3A). C. showae ecotin displays complete inhibition of NE at the high dose of 1666.67 nM in three out of the four tested sputa (Fig. 3A–B). C. showae ecotin shows a close-to-complete inhibition of NE activities in the sputum from patient CFBR185 at a dose as low as 55.56 nM (Fig. 3A). In sputum samples CFBR 614 and 185, C. showae ecotin significantly inhibits NE at a concentration as low as 16.67 nM (Fig. 3A). The level of inhibition of NE by C. showae ecotin does differ between the four CF sputa tested as it is also reflected in their IC50 values (16.1, 46.5, 87.5 and 342.1 nM) (Fig. 3B). Overall, C. showae ecotin inhibits NE in CF sputa, in a similar nM concentration range observed for the C. rectus ecotin.

Fig. 3.

C. showae ecotin inhibits neutrophil elastase activity in CF sputa. A)C. showae ecotin was added in increasing concentrations (0–1666.7 nM) to the sputum supernatant obtained from four PwCF and NE activity was measured (mU/ml). Percent inhibition of NE activity for each CF sputum sample was determined. Mean ± S.E.M. of (n = 3–4) samples is shown. Data were analyzed by One-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparison test. B) Summary data for percent inhibition of NE activity by the addition of increasing concentrations of C. showae ecotin to each CF sputum sample is shown. IC50 values for each CF sputum were determined for (n = 3–4) samples. Statistical differences were considered as ∗, p < 0.05; ∗∗∗, p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗, p < 0.0001.

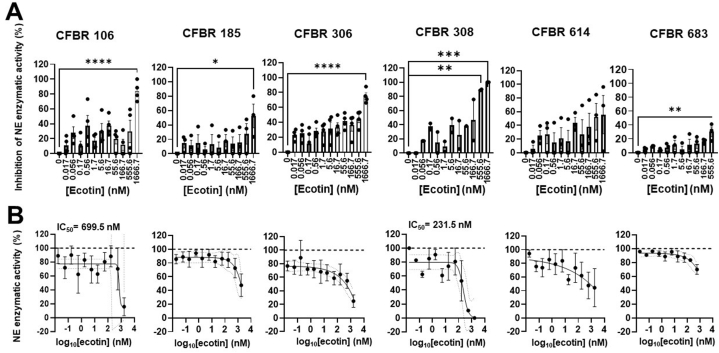

3.4. E. coli ecotin is a less potent inhibitor of NE in CF sputa than Campylobacter ecotins

Next we compared the efficacy of Campylobacter ecotins on NE activity in CF sputa to that of E. coli ecotin. E. coli ecotin significantly inhibited NE in five of the six CF sputum supernatants tested, showing significant inhibition for CFBR106, 185, 306 and 683 at 1666.7 nM and for CFBR308 at 555.6 nM (Fig. 4A). However, inhibition was only moderate for CFBR185 and just at one dose and minimal to none for sputa from CFBR 614 and 683. This failure of E. coli ecotin to inhibit NE for these latter 2 subjects was in sharp contrast to the high degree of inhibition observed for the Campylobacter ecotins (Fig. 4 vs. Fig. 2, Fig. 3). Since there are differences in the NE-inhibitory effect of the E. coli ecotin among the six CF sputa tested, reliable IC50 values could only be calculated for CFBR106 (699.5 nM) and CFBR308 (231.5 nM) (Fig. 4B). Overall, E. coli ecotin does inhibit NE in some CF sputa at doses higher relative to the Campylobacter ecotins.

Fig. 4.

E. coli ecotin is a weak inhibitor of neutrophil elastase activity in CF sputa. A)E. coli ecotin was added in increasing concentrations (0–1666.7 nM) to the sputum supernatants of six PwCF and NE activity was measured (mU/ml). Percent inhibition of NE activity for each sputum sample was determined. Mean ± S.E.M. of (n = 2–4) samples is shown. Data were analyzed by One-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparison test. B) summary data for inhibition of NE activity by the addition of increasing concentrations of E. coli ecotin to each CF sputum sample is shown. IC50 values for each CF sputum were determined for (n = 2–4) samples. Statistical differences were considered as ∗, p < 0.05; ∗∗, p < 0.01; ∗∗∗, p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗, p < 0.0001.

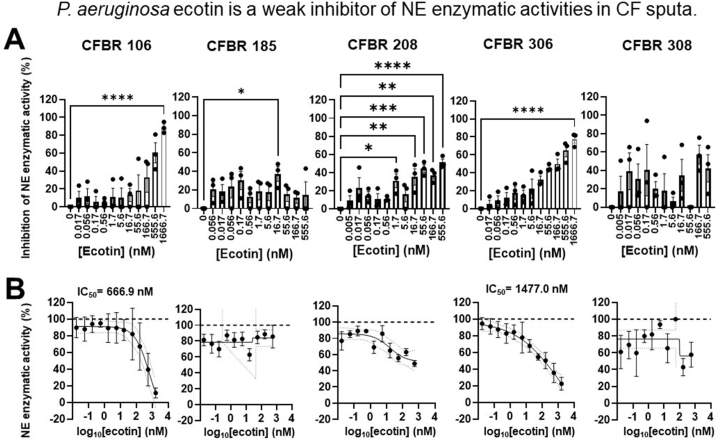

3.5. P. aeruginosa ecotin is the least potent inhibitor of NE activity in the CF sputa

Ecotin from P. aeruginosa was found to inhibit NE in vitro [52]. Therefore, we cloned and expressed the P. aeruginosa ecotin and explored its effect on NE activities in CF sputa. P. aeruginosa ecotin significantly inhibited NE activities in three (CFBR 106, 208 and 306) of the five CF sputa tested (Fig. 5A) and displayed inhibitory action at higher concentrations in a dose-dependent manner. In the CFBR 208 sputum, P. aeruginosa ecotin was able to significantly inhibit NE at a concentration as low as 1.7 nM (Fig. 5A). While P. aeruginosa ecotin significantly inhibited NE in the sputum from CFBR185 at a concentration of 16.7 nM, at higher ecotin concentrations it did not display significant inhibition and overall a clear dose-dependent trend could not be observed (Fig. 5A). P. aeruginosa ecotin was also unable to inhibit NE in the sputum of patient CFBR308. P. aeruginosa ecotin inhibits NE enzymatic activities by more than 50 % in only two of the five CF sputa tested (CFBR106 and 306), hence IC50 values could only be determined for those two (Fig. 5B). Altogether, P. aeruginosa ecotin is the weakest NE inhibitor in CF sputa tested in this study. Finally, only two of the six sputa (CFBR106 and 306) appeared to be sensitive to NE inhibition by three ecotins: Campylobacter, P. aeruginosa and E. coli.

Fig. 5.

P. aeruginosa ecotin is a weak inhibitor of neutrophil elastase activity in CF sputa. A)P. aeruginosa ecotin was added in increasing concentrations (0–555.56 nM) to the sputum supernatant from three PwCF and NE activity was measured (mU/ml). Percent inhibition of NE activity for each sputum sample was determined by the quantification of NE activity (mU/ml) at each dose of ecotin over the quantification of NE activity without ecotin (shown as 0 nM on the graph). Mean ± S.E.M. of (n = 3) samples is shown. Data were analyzed by One-way ANOVA, Dunnett's multiple comparison test. (B) Summary data for inhibition of NE activity by the addition of increasing concentrations of P. aeruginosa ecotin to each CF sputum. IC50 values for each CF sputum were determined for (n = 3) samples. Statistical differences were considered as ∗, p < 0.05; ∗∗, p < 0.01; ∗∗∗, p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗, p < 0.0001.

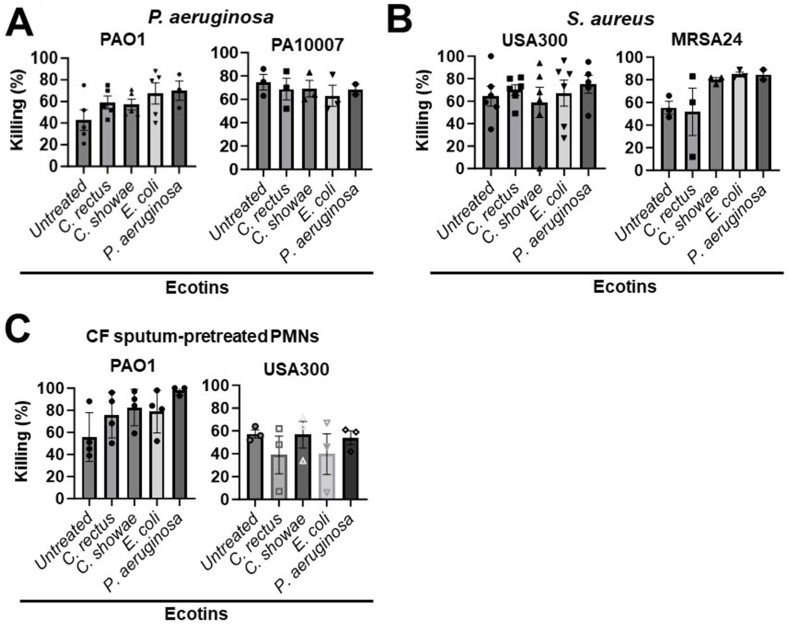

3.6. Ecotins do not impair neutrophil-mediated killing of P. aeruginosa or S. Aureus

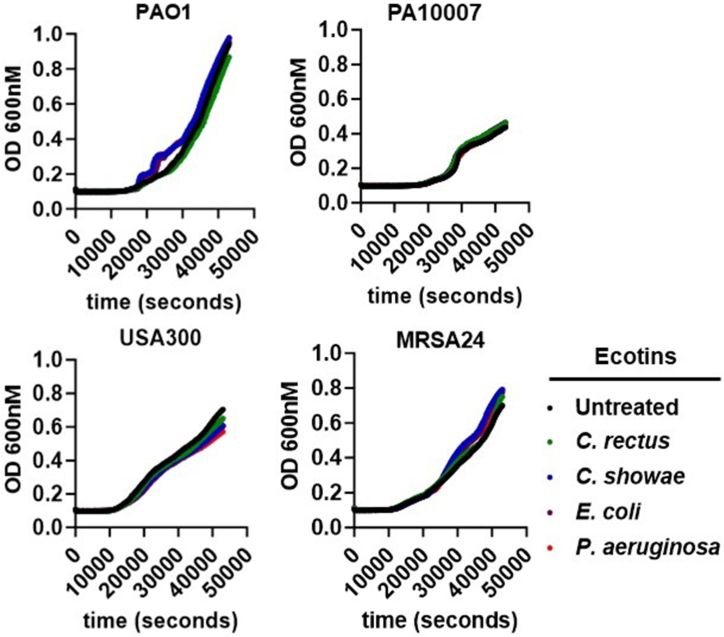

Data showcased earlier suggest that Campylobacter ecotins are potent NE inhibitors in the CF sputum (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5). To investigate whether ecotins added to neutrophils would interfere with their primary immune function, bacterial killing, the effect of ecotins on neutrophil-mediated killing of the two dominant CF pathogens, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, was explored. Ecotin was added to neutrophils and killing of bacteria opsonized in the serum of the neutrophil donor was assessed. Two P. aeruginosa strains (PAO1 and a CF isolate, PA10007) and two S. aureus strains (USA300 and a CF isolate, MRSA24) were tested (Table 2). First, bacterial killing of P. aeruginosa by neutrophils was measured after treatment with ecotins at a dose that inhibits NE activity in most CF sputum samples (555.6 nM). Overall, none of the ecotin species impaired neutrophil-mediated killing of P. aerugionsa (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Ecotin does not impair neutrophil-mediated killing of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. A) The results of P. aeruginosa killing by neutrophils with or without ecotin. Two P. aeruginosa strains (PAO1, n = 5, and the CF clinical isolate, 10007, n = 3) were tested. Neutrophils were either untreated or treated with 555.6 nM of the indicated ecotins and infected with P. aeruginosa at a MOI of 10. Bacterial killing was measured by a microplate-based assay. Each symbol in the bar graph represents one neutrophil donor and the corresponding percent killing of P. aeruginosa. Mean ± S.E.M. of samples are shown. Comparison of percent killing by ecotin-treated neutrophils to untreated neutrophils was analyzed by One-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison test. B) The results of bacterial killing of S. aureus by neutrophils with or without treatment of ecotin. Two S. aureus strains were tested, USA300 (n = 6) and the CF clinical isolate, MRSA24 (n = 3). Neutrophils were either untreated or treated with 555.6 nM of each ecotin and infected with S. aureus at a MOI 10. Mean ± S.E.M. of samples is shown. Data were analyzed as described in (A). C) Human neutrophils were pre-treated with 30 % (v/v) of pooled CF sputum supernatants for 3.5 h according to the “CF sputum model”. After washing out excess sputum, the killing of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (n = 4) and S. aureus USA300 (n = 3) (1 MOI) were measured using the microplate-based killing assay. MOI, multiplicity of infection. Statistical differences were considered as ∗, p < 0.05.

Next, bacterial killing of S. aureus by neutrophils after ecotin treatment was measured with two strains, the reference stain USA300 and a CF clinical isolate MRSA24. As shown in Fig. 6B, none of the ecotins significantly inhibited S. aureus killing by neutrophils.

To mimic the environment of the CF airways, we used our established “CF sputum model” by incubating human neutrophils in a pooled mix of sputum supernatants received from at least 5 PwCF. After 3.5 h, CF sputum was washed away and neutrophils were exposed to ecotin and opsonized bacteria to test the potential effect of ecotin on bacterial killing of neutrophils under “CF airway-like” conditions [40,41]. None of the tested ecotins had any significant effect on killing of P. aeruginosa PAO1 or S. aureus USA300 by neutrophils under CF airway-like conditions (Fig. 6C).

To ensure that ecotins do not interfere with bacterial growth, ecotin and bacteria alone were incubated (without neutrophils), and the growth of indicated bacterial strains were determined overtime by measuring OD600. As shown in Fig. 7, when compared to untreated bacteria, there were no differences in the growth kinetics of bacteria with or without added ecotins. Altogether, ecotins do not impair neutrophil-mediated killing or growth of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus.

Fig. 7.

Ecotin does not impair the growth of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Kinetic growth curves of P. aeruginosa bacterial strains, PAO1 and PA1007, and S. aureus bacterial strains, USA300 and MRSA24, in the presence of 555.6 nM ecotin (without neutrophils). OD, optical density. Statistical differences were considered as ∗, p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

This study describes the ability of various ecotins to inhibit NE enzymatic activity in human CF sputum samples without compromising neutrophil-mediated bacterial killing of two dominant CF lung pathogens, P. aeruginosa or S. aureus. The ecotin homologs from C. rectus, C. showae, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa showed variability in their capacity to inhibit NE activity in the CF sputa while none compromised neutrophil-mediated bacterial killing and/or bacterial growth. C. rectus and C. showae ecotins displayed a strong inhibition of NE activity in CF sputa, with complete inhibition at the higher doses tested. In contrast, E. coli and P. aeruginosa ecotins were both weak inhibitors of NE activity in CF sputa and in some instances, failed to show any inhibitory action.

The NE-inhibitory patterns of the tested ecotins in the CF sputa are different from our studies using purified human NE where no differences were observed: IC50 values (nM) for E. coli (4.64 ± 0.23), C. rectus (4.49 ± 0.25) and C. showae (4.78 ± 0.31) ecotins (34). The reason for this could possibly be explained by differences between purified human NE and the more complex CF sputum samples. Based on protein sequence alignments, the P. aeruginosa ecotin is more similar to the E. coli ecotin with approximately 60 % identity. There is low amino acid similarity between ecotin homologs from the Campylobacter species compared to E. coli and P. aeruginosa [34,37]. For example, the C. rectus and C. showae ecotins have 27 % and 33 % amino acid identity to the E. coli and 25 % and 27 % identity to the P. aeruginosa ecotin [34]. The two cysteines (Cys50 and Cys87) which form an intra-subunit disulfide bond in the E. coli ecotin are conserved [37]. However, the substrate binding pocket residues are different compared to E. coli [37] and these might influence the oligomerization capacity of the heterotrimeric E. coli ecotin-NE complex [42]. Altogether, these differences may play a role in the ability to bind and inhibit NE active sites in more complex media such as CF sputa. This idea is supported by our previous data showing that the C. rectus ecotin was capable of protecting a C. jejuni protein glycosylation mutant from proteolytic attack within chicken cecal samples by approximately 5 × 106 CFU more compared to the C. showae ecotin [37].

NE concentrations in CF sputum samples varies across a wide range in our study that is consistent with prior observations made by other groups [[53], [54], [55]]. Unfortunately, the same CF supernatants could not be tested in each figure as only limited amounts of these supernatants were available and some were only used in experiments for one or two readouts. The CF sputum contains NE in multiple compartments such as free NE released from neutrophils as well as NE bound to NETs or exosomes [13,25,56]. The differences between the ecotin species and their ability to inhibit NE in the complete sputa versus NETs could be due to the efficacy of ecotin to inhibit NE in the different compartments and to the differences in NE compartmentalization among different CF sputa. Dissecting the components of the CF sputa and the affinity for each ecotin to inhibit NE found in different compartments could help explain this result. Additionally, PwCF infected with P. aeruginosa may contain P. aeruginosa ecotin in their lung environment, which has been shown to bind to the biofilm exopolysaccharide matrix and likely protects neighboring P. aeruginosa cells from NE-mediated damage [57].

Despite P. aeruginosa ecotins being present in the CF lung, NE is active and causes severe damage of lung tissues. Therefore, P. aeruginosa ecotins may only be efficient in protecting the microbe from NE within biofilms, but the quantities of ecotin that are released are likely unable to inhibit lung tissue damage caused by NE. Our data suggests that addition of exogenous ecotin inhibits NE activity in the CF sputum while does not interfere with neutrophil-mediated killing of CF clinical isolates in vitro. These results raise the question whether ecotin could be of interest for studies on its potential to be a new NE-targeting therapeutic.

There are currently no approved NE inhibitors for human use. Sivelestat was used a positive control in this study as it has been shown to reduce NE activity, however, clinical trials deemed this drug ineffective in PwCF [45]. A meta-analysis analyzing the clinical trials performed with sivelestat in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome showed that the compound did not improve mortality and did not alter the duration of mechanical ventilation [58]. It has been shown that NE inhibition by sivelestat did not enhance the occurrence of infections, suggesting that NE inhibitors could improve lung function without worsening infections [45,59,60]. Therefore, new inhibitors against NE with a known mechanism of action are needed. Ecotin from C. rectus and C. showae showed the same inhibitory effects as sivelestat, with complete NE inhibition in the CF sputa.

Altogether, our study characterizes the effect of four ecotin homologs on their inhibitory activity of NE in CF sputa and neutrophil-mediated bactericidal responses. This is the first study to characterize the P. aeruginosa ecotin and its limited ability to inhibit NE in the CF sputum. This is also the first study to test ecotin as an NE inhibitor in CF airway disease. Our in vitro data suggest that the ecotins from C. rectus and C. showae have the potential to significantly reduce NE activity in the CF airways, however more studies are needed to determine the effect on the reduction of lung injury. Future studies will also test ecotin in the βENaC-Tg CF mouse model demonstrating a neutrophilic and NE-mediated, CF-like lung disease. Our team has characterized this mouse model and has observed significant lung inflammation mediated by neutrophils (64). The addition of ecotin in vivo to measure its effect on NE activity and lung injury would further confirm that ecotin has potential for therapeutic use in CF lung disease.

Since ecotin is a bacterial protein, administering it to mammalian organisms carries the risk of inducing an inflammatory or antibody response. Therefore, the safety of administering ecotin, or its future derivatives, need to be carefully investigated. Ecotin was reported to exhibit a broad range of inhibitory activity against exogenous serine proteases such as trypsin, chymotrypsin, factor Xa, kallikrein, urokinase, factor XII, and NE [[34], [35], [36], [37],[61], [62], [63]]. Delivering ecotin directly to airways, therefore, likely represents a better approach to inhibit airway proteases without interfering with proteases in the blood or the gut lumen.

A limitation of the current study is the small number of CF subjects recruited and their sputum samples used. Also, only two strains of each CF pathogen were tested in the neutrophil killing assays. In the future, the effect of ecotins on NE will be expanded to sputum samples of a larger CF study cohort using more bacterial clinical isolates.

Lung function decline is the main cause of morbidity and mortality in PwCF, with NE correlating with decreased lung function. NE has been a target in PwCF for years with no successful, approved therapeutics thus far. Our future work will aim to better characterize the effect of ecotin, and its derivatives, on inhibiting NE activity and its consequences in CF.

Ethics statement

All human subject studies were performed according to the guidelines of the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. Healthy human subjects were recruited at the University of Georgia (UGA) and provided informed consent for blood donation for neutrophil isolation according to the protocol UGA# 2012-10769-06 approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Georgia.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health awards (R01HL136707-01A1 to B. Rada) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (003303I221 to B. Rada). This work was also supported by the Georgia CTSA Training Grant, TL1 TR002382 and UL1TR002378. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Data and code availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kayla M. Fantone: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Harald Nothaft: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Yeongseo Son: Formal analysis, Data curation. Arlene A. Stecenko: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Christine M. Szymanski: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization. Balázs Rada: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the CF Biospecimen Repository at the Children's Healthcare of Atlanta and Emory University CF Discovery Core for providing CF human samples. We would also like to thank all the healthy subjects for their blood donations and the staff of the UGA Clinical and Translational Research Unit for their support. We thank Joanna Goldberg at Emory University for providing the CF S. aureus clinical isolate, Samuel Moskowitz (Massachusetts General Hospital, currently: Vertex Pharmaceuticals) for providing the CF P. aeruginosa clinical isolate, and Cody Thomas, Clay Crippen and Bibi Zhou in the Szymanski laboratory at UGA for their efforts in providing ecotin preparations for testing.

References

- 1.Blankenship S., et al. What the future holds: cystic fibrosis and aging. Front. Med. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1340388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown S.D., White R., Tobin P. Keep them breathing: cystic fibrosis pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J. Am. Acad. Physician Assistants. 2017;30(5):23–27. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000515540.36581.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan M.A., et al. Progression of cystic fibrosis lung disease from childhood to adulthood: neutrophils, neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, and NET degradation. Genes. 2019;10(3) doi: 10.3390/genes10030183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinkmann V., et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stapels D.A., Geisbrecht B.V., Rooijakkers S.H. Neutrophil serine proteases in antibacterial defense. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015;23:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branzk N., et al. Neutrophils sense microbe size and selectively release neutrophil extracellular traps in response to large pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15(11):1017–1025. doi: 10.1038/ni.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlsson M., et al. Pseudomonas-induced lung damage in cystic fibrosis correlates to bactericidal-permeability increasing protein (BPI)-autoantibodies. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2003;21(6 Suppl 32):S95–S100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garner H.P., et al. Peroxidase activity within circulating neutrophils correlates with pulmonary phenotype in cystic fibrosis. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2004;144(3):127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J.S., Okamoto K., Rubin B.K. Pulmonary function is negatively correlated with sputum inflammatory markers and cough clearability in subjects with cystic fibrosis but not those with chronic bronchitis. Chest. 2006;129(5):1148–1154. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson R.L., et al. Duration of treatment effect after tobramycin solution for inhalation in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2007;42(7):610–623. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regelmann W.E., et al. Sputum peroxidase activity correlates with the severity of lung disease in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 1995;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer-Hamblett N., et al. Initial Pseudomonas aeruginosa treatment failure is associated with exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2012;47(2):125–134. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dittrich A.S., et al. Elastase activity on sputum neutrophils correlates with severity of lung disease in cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2018;51(3) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01910-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sagel S.D., Kapsner R.K., Osberg I. Induced sputum matrix metalloproteinase-9 correlates with lung function and airway inflammation in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2005;39(3):224–232. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oriano M., et al. Evaluation of active neutrophil elastase in sputum of bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis patients: a comparison among different techniques. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019;59 doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2019.101856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaggar A., et al. Matrix metalloprotease-9 dysregulation in lower airway secretions of cystic fibrosis patients. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2007;293(1):L96–L104. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00492.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcos V., et al. Free DNA in cystic fibrosis airway fluids correlates with airflow obstruction. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/408935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lepissier A., et al. Inflammation biomarkers in sputum for clinical trials in cystic fibrosis: current understanding and gaps in knowledge. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2022;21(4):691–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belaaouaj A., Kim K.S., Shapiro S.D. Degradation of outer membrane protein A in Escherichia coli killing by neutrophil elastase. Science. 2000;289(5482):1185–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doring G. The role of neutrophil elastase in chronic inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994;150(6 Pt 2):S114–S117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/150.6_Pt_2.S114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantin A.M., et al. Inflammation in cystic fibrosis lung disease: pathogenesis and therapy. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2015;14(4):419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawabata K., Hagio T., Matsuoka S. The role of neutrophil elastase in acute lung injury. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;451(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voynow J.A., Shinbashi M. Neutrophil elastase and chronic lung disease. Biomolecules. 2021;11(8) doi: 10.3390/biom11081065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papayannopoulos V., Staab D., Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase enhances sputum solubilization in cystic fibrosis patients receiving DNase therapy. PLoS One. 2011;6(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genschmer K.R., et al. Activated PMN exosomes: pathogenic entities causing matrix destruction and disease in the lung. Cell. 2019;176(1–2):113–126 e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park J.A., et al. Human neutrophil elastase induces hypersecretion of mucin from well-differentiated human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro via a protein kinase Cdelta-mediated mechanism. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;167(3):651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62040-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regamey N., et al. Airway remodelling and its relationship to inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2011;66(7):624–629. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.134106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sly P.D., et al. Risk factors for bronchiectasis in children with cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368(21):1963–1970. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sagel S.D., et al. Induced sputum inflammatory measures correlate with lung function in children with cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. 2002;141(6):811–817. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.129847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwahashi M., et al. Optimal period for the prophylactic administration of neutrophil elastase inhibitor for patients with esophageal cancer undergoing esophagectomy. World J. Surg. 2011;35(7):1573–1579. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakashita A., et al. Neutrophil elastase inhibitor (sivelestat) attenuates subsequent ventilator-induced lung injury in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007;571(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramos K.J., Pilewski J.M., Taylor-Cousar J.L. Challenges in the use of highly effective modulator treatment for cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2021;20(3):381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jobichen C., et al. Structural basis for the inhibition mechanism of ecotin against neutrophil elastase by targeting the active site and secondary binding site. Biochemistry. 2020;59(30):2788–2795. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eggers C.T., et al. The periplasmic serine protease inhibitor ecotin protects bacteria against neutrophil elastase. Biochem. J. 2004;379(Pt 1):107–118. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung C.H., et al. Purification from Escherichia coli of a periplasmic protein that is a potent inhibitor of pancreatic proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258(18):11032–11038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mikumo H., et al. Neutrophil elastase inhibitor sivelestat ameliorates gefitinib-naphthalene-induced acute pneumonitis in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;486(1):205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas C., et al. Characterization of ecotin homologs from Campylobacter rectus and Campylobacter showae. PLoS One. 2020;15(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagy Z.A., et al. Ecotin, a microbial inhibitor of serine proteases, blocks multiple complement dependent and independent microbicidal activities of human serum. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark E.A., et al. Molecular recognition of chymotrypsin by the serine protease inhibitor ecotin from Yersinia pestis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(27):24015–24022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.225730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fantone K., et al. Cystic fibrosis sputum impairs the ability of neutrophils to kill Staphylococcus aureus. Pathogens. 2021;10(6) doi: 10.3390/pathogens10060703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fantone K.M., et al. Sputum from people with cystic fibrosis reduces the killing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by neutrophils and diminishes phagosomal production of reactive oxygen species. Pathogens. 2023;12(9) doi: 10.3390/pathogens12091148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyoshi S., et al. Usefulness of a selective neutrophil elastase inhibitor, sivelestat, in acute lung injury patients with sepsis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2013;7:305–316. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S42004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayakawa M., et al. Sivelestat (selective neutrophil elastase inhibitor) improves the mortality rate of sepsis associated with both acute respiratory distress syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation patients. Shock. 2010;33(1):14–18. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181aa95c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayashida K., et al. Early administration of sivelestat, the neutrophil elastase inhibitor, in adults for acute lung injury following gastric aspiration. Shock. 2011;36(3):223–227. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318225acc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aikawa N., Kawasaki Y. Clinical utility of the neutrophil elastase inhibitor sivelestat for the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Therapeut. Clin. Risk Manag. 2014;10:621–629. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S65066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rada B.K., et al. Dual role of phagocytic NADPH oxidase in bacterial killing. Blood. 2004;104(9):2947–2953. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoo D.G., et al. Release of cystic fibrosis airway inflammatory markers from Pseudomonas aeruginosa-stimulated human neutrophils involves NADPH oxidase-dependent extracellular DNA trap formation. J. Immunol. 2014;192(10):4728–4738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sil P., et al. P2Y6 receptor antagonist MRS2578 inhibits neutrophil activation and aggregated neutrophil extracellular trap formation induced by gout-associated monosodium urate crystals. J. Immunol. 2017;198(1):428–442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sil P., et al. Macrophage-derived IL-1beta enhances monosodium urate crystal-triggered NET formation. Inflamm. Res. 2017;66(3):227–237. doi: 10.1007/s00011-016-1008-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahlen S.D., Clarridge J.E. 3rd, Oral abscess caused by Campylobacter rectus: case report and literature review. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47(3):848–851. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01590-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abdel-Magid A.F. Neutrophil elastase inhibitors as potential anti-inflammatory therapies. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;5(11):1182–1183. doi: 10.1021/ml500346u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Brien S.J. The consequences of Campylobacter infection. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2017;33(1):14–20. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.AbdulWahab A., et al. Sputum and plasma neutrophil elastase in stable Adult patients with cystic fibrosis in relation to chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization. Cureus. 2021;13(6) doi: 10.7759/cureus.15948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iwata K., et al. Effect of neutrophil elastase inhibitor (sivelestat sodium) in the treatment of acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern. Med. 2010;49(22):2423–2432. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeiher B.G., et al. Neutrophil elastase inhibition in acute lung injury: results of the STRIVE study. Crit. Care Med. 2004;32(8):1695–1702. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000133332.48386.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hagio T., et al. Inhibition of neutrophil elastase reduces lung injury and bacterial count in hamsters. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;21(6):884–891. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tseng B.S., et al. A biofilm matrix-associated protease inhibitor protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa from proteolytic attack. mBio. 2018;9(2) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00543-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aikawa N., et al. Reevaluation of the efficacy and safety of the neutrophil elastase inhibitor, Sivelestat, for the treatment of acute lung injury associated with systemic inflammatory response syndrome; a phase IV study. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;24(5):549–554. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou Z., et al. The ENaC-overexpressing mouse as a model of cystic fibrosis lung disease. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2011;10(Suppl 2):S172–S182. doi: 10.1016/S1569-1993(11)60021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tucker S.L., Sarr D., Rada B. Neutrophil extracellular traps are present in the airways of ENaC-overexpressing mice with cystic fibrosis-like lung disease. BMC Immunol. 2021;22(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12865-021-00397-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ulmer J.S., et al. Ecotin is a potent inhibitor of the contact system proteases factor XIIa and plasma kallikrein. FEBS Lett. 1995;365(2–3):159–163. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00466-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seymour J.L., et al. Ecotin is a potent anticoagulant and reversible tight-binding inhibitor of factor Xa. Biochemistry. 1994;33(13):3949–3958. doi: 10.1021/bi00179a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ireland P.M., et al. The serine protease inhibitor Ecotin is required for full virulence of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Microb. Pathog. 2014;67–68:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.