Abstract

The low-neurovirulence Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis viruses (TMEV), such as BeAn virus, cause a persistent infection of the central nervous system (CNS) in susceptible mouse strains that results in inflammatory demyelination. The ability of TMEV to persist in the mouse CNS has traditionally been demonstrated by recovering infectious virus from the spinal cord. Results of infectivity assays led to the notion that TMEV persists at low levels. In the present study, we analyzed the copy number of TMEV genomes, plus- to minus-strand ratios, and full-length species in the spinal cords of infected mice and infected tissue culture cells by using Northern hybridization. Considering the low levels of infectious virus in the spinal cord, a surprisingly large number of viral genomes (mean of 3.0 × 109) was detected in persistently infected mice. In the transition from the acute (approximately postinfection [p.i.] day 7) to the persistent (beginning on p.i. day 28) phase of infection, viral RNA copy numbers steadily increased, indicating that TMEV persistence involves active viral RNA replication. Further, BeAn viral genomes were full-length in size; i.e., no subgenomic species were detected and the ratio of BeAn virus plus- to minus-strand RNA indicated that viral RNA replication is unperturbed in the mouse spinal cord. Analysis of cultured macrophages and oligodendrocytes suggests that either of these cell types can potentially synthesize high numbers of viral RNA copies if infected in the spinal cord and therefore account for the heavy viral load. A scheme is presented for the direct isolation of both cell types directly from infected spinal cords for further viral analyses.

Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV), an enteric pathogen of mice containing a single-stranded RNA genome of positive polarity, belongs to the Picornaviridae family (31). TMEVs can be divided into two groups based on neurovirulence following intracerebral (i.c.) inoculation of mice. High-neurovirulence strains, such as GDVII, produce a rapidly fatal encephalitis in mice. Low-neurovirulence TMEVs, such as BeAn and DA, cause a persistent infection of the central nervous system (CNS) in susceptible mouse strains that results in immune-mediated damage, as well as viral destruction of oligodendrocytes and, hence, demyelination (2, 9, 13, 36).

After i.c. inoculation of mice, the low-neurovirulence strains infect neurons in the gray matter of the brain and spinal cord during the acute phase of virus growth, which is followed by virus persistence in cells in the spinal cord white matter. During the persistent phase of infection, TMEV RNA and antigens have been found mainly in macrophages (24, 30) and to a lesser extent in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes (1). In contrast to the experience of other investigators, we have not detected virus antigen in astrocytes of SJL mice injected with 106 PFU of BeAn virus, which produces an onset of demyelinating disease more rapid than that observed after infection of these mice with DA virus (24, 34).

The ability of TMEV to persist in the mouse CNS has traditionally been demonstrated by recovering infectious virus from the spinal cord. Results of infectivity assays led to the notion that TMEV persists at low levels, usually with <104 PFU detected per spinal cord (6, 23). Northern hybridization to detect TMEV RNA has proven to be a sensitive method of analyzing TMEV persistence (3) and the relative abundance of TMEV RNA in spinal cords from infected mice (21).

In the present study, we analyzed the copy number of TMEV genomes, plus- to minus-strand ratios, and full-length species in the spinal cords of infected mice and infected tissue culture cells by using Northern hybridization. Considering the low levels of infectious virus in the spinal cord, a surprisingly large number of viral genomes was detected in persistently infected mice, even as late as postinfection (p.i.) day 223. The temporal graph of viral RNA copies in the acute phase versus the persistent phase of infection indicated that TMEV persistence involves active viral RNA replication. Analysis of cultured macrophages and oligodendrocytes suggests that either of these cell types can potentially synthesize high numbers of viral RNA copies if infected in the spinal cord and therefore account for the heavy viral load. A scheme is presented for the direct isolation of both cell types directly from infected spinal cords for further viral analyses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

BHK-21 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 7.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 6.5 mg of tryptose phosphate broth (Gibco/BRL) per ml at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Viral plaques were assayed on BHK-21 cell monolayers in 35-mm-diameter multiwell plates by staining with crystal violet after incubation for 4 days at 33°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere as previously described (37). N20 mature mouse oligodendrocytes (obtained from Anthony Campagnoni) (12) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium-F12 medium containing 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 10% FBS at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. M1-D cells were derived from the myelomonocytic cell line M1 by treatment with conditioned medium and maintained as previously described (20).

Mice and virus inoculations.

SJL (female), CBA, and C.B-17 mice, purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine), were caged and maintained in accordance with American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care standards and received autoclaved standard mouse chow and water ad libitum. Mice (6 to 8 weeks old) were anesthetized with 1 mg of pentobarbital intraperitoneally and inoculated in the right cerebral hemisphere with 106 PFU of virus.

Virus infections.

Nearly confluent BHK-21, N20, and M1-D cell monolayers in 100-mm-diameter dishes were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and infected with BeAn virus at a multiplicity of 10. Following 45 min of incubation at 24°C to allow virus attachment, cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS, infection medium (same as the growth medium used for each cell type, except that the FBS concentration was reduced to 0.5%) was added, and incubation was continued at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Isolation of CNS cells from spinal cords.

Spinal cords flushed from the spinal canals of mice with chilled PBS deficient in Ca2+ and Mg2+ were dissected into 1-mm pieces and dissociated into a single-cell suspension by incubation in 300 U of RNase-free type III collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, N.J.) per ml in Hanks balanced salt solution for 15 min at 37°C. Collagenase digestion was repeated several times or until tissue fragments no longer remained. Cell suspensions were then sieved through screens (Sefar American Inc., Kansas City, Kans.) of graded pore sizes (350, 209, 130, and 38 μm for oligodendrocytes and 350, 209, and 130 μm for macrophages). Passage though the 38-μm-pore-size screen ensured dissociation of oligodendrocytes from myelin and elimination of most macrophages. Oligodendrocytes were isolated by centrifugation through 0.9 M sucrose in 35-ml Oakridge tubes (40), followed by incubation of the resuspended cells on plastic petri dishes for 20 min at 37°C to remove any remaining macrophages. Greater than 90% of these cells stained with mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) 8-18C5 to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG). Macrophages were isolated on discontinuous Percoll gradients in 30-ml Oakridge tubes, harvested from the band at the 30 to 70% Percoll interface, and phenotyped by flow cytometry as previously described (10). This band contained, on average, 25% macrophages (MOMA-2 or Mac-1 positive) and 75% B and T lymphocytes; since B and T lymphocytes are not infected by TMEV, these cells could be assayed directly or macrophages could be obtained by panning for viral genome analyses.

Total-RNA isolation.

For cell cultures, Trizol solution (Gibco) was added directly to infected or uninfected monolayers in 100-mm-diameter dishes, whereas tissues (brains and spinal cords) were frozen in liquid nitrogen, broken into pieces, and placed in 13 and 1 ml of Trizol, respectively. Cells or pieces of tissue were homogenized with a Polytron (Beckman Instruments), and total RNA was isolated by following the manufacturer's recommendations. The quality and amount of RNA in spinal cord samples from individual mice were ascertained by examining 18S and 28S rRNAs by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Northern hybridization.

Total RNA from mouse tissues or cell cultures was ethanol precipitated, resuspended in RNA loading buffer [50% formamide, 7% formaldehyde, 0.04% bromophenol blue in 200 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (pH 7.0), 50 mM sodium acetate, 10 mM EDTA (MOPS buffer)], heated for 5 min at 95°C, and electrophoresed in a 1% agarose gel at 80 to 90 V for 1 h. The gel was soaked in distilled water for 15 min and in 5× SSC (20× SSC is 3 M NaCl plus 0.3 M Na citrate) with 10 mM NaOH for 30 min. RNA was passively transferred to a Bright-star plus nylon membrane (Ambion Inc.), treated with short-wavelength UV light for 2 min, and prehybridized with Ultra-hyb solution (Ambion) for at least 30 min at 42°C. A random-primed DNA probe specific for BeAn virus was derived from a 1.5-kb EcoRI fragment of BeAn cDNA spanning nucleotides 2772 to 4295 by using the Random Primed DNA Labeling Kit (Boehringer Mannheim) with a specific activity of at least 109 cpm/μg. The probe was added to the prehybridization solution, and hybridization was carried out overnight at 42°C. Membranes were washed once with 1× SSC–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 24°C for 20 min and three times with 0.2× SSC–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 68°C for 20 min each time, dried, and exposed to a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager screen to detect BeAn virus with the [α-32P]dCTP-labeled hybridized probe.

For dot blots, RNA was serially diluted and 10 μl was mixed with 20 μl of formamide, 7 μl of formaldehyde, and 2 μl of 20× SSC and samples were heated for 15 min at 68°C. Two volumes of 20× SSC was added, and samples were loaded onto a Minifold dot blot apparatus (Schleicher & Schuell) containing a nitrocellulose filter presoaked in 20× SSC for 1 h and washed with 10× SSC. Samples were vacuum drawn through the dot blot apparatus, and the filter was washed twice with 0.5 ml of 10× SSC, dried for 2 h at 80°C under vacuum, prehybridized, hybridized, and washed as described above.

Detection of minus-strand TMEV RNA.

A modified RNase protection method using reagents from the RPA III kit (Ambion) and Northern blots were used to detect double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (29). Briefly, total RNA from infected cells (in cell cultures or in tissue) was heated to 95°C for 5 min and incubated overnight at 42°C to anneal plus- and minus-strand viral RNA. Annealed RNA was treated with a 1:100 dilution of RNases A and T1 (RPA III kit; Ambion) for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was terminated with RNase inactivation-precipitation buffer and kept at −20°C to precipitate RNA. Resuspended dsRNA was blotted onto nitrocellulose filters and probed with α-32P-labeled BeAn DNA as described above. The signal in RNase-treated samples corresponds only to dsRNA, since RNase treatment digested excess plus strands that did not anneal to minus strands. The ratio of plus to minus strands was determined by parallel dot blots of RNase-treated and untreated RNAs, with 50% of the signal detected in RNase-treated samples representing the copy number of minus strands. Treatment of BeAn RNA from purified virions with RNase was used in experiments to control for the completeness of RNase digestion.

Flow cytometry.

For each experiment with cells from gradients, 0.1 × 106 to 0.5 × 106 cells were washed once in cold PBS (pH 7.2) containing 2.0% bovine serum albumin and 0.02% sodium azide, blocked by incubation with 10 μl of normal goat and human sera and Fc block (Pharmingen), and stained for surface antigens (CD3, CD19, Mac-1, and MOG) or treated with 0.3% saponin to permeabilize cell membranes for cytoplasmic staining (MOMA-2) as previously described (19).

Reagents and antibodies.

The following antibodies and reagents were used: 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD; DNA staining; Sigma), biotinylated mouse MAb 8-18C5 (anti-MOG; Minnetta Gardinier, Iowa City, Iowa), CD3-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (T lymphocytes), CD19-phycoerythrin (B lymphocytes; Pharmingen), cow glial fibrillary acidic protein (astrocytes; DAKO), rat MAbs MOMA-2 and Mac-1 (macrophages; G. Kraal, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Caltag, respectively), and goat anti-rat immunoglobulin G-FITC (mouse absorbed; Caltag).

RESULTS

Determination of viral genome copy numbers in infected tissues and cells.

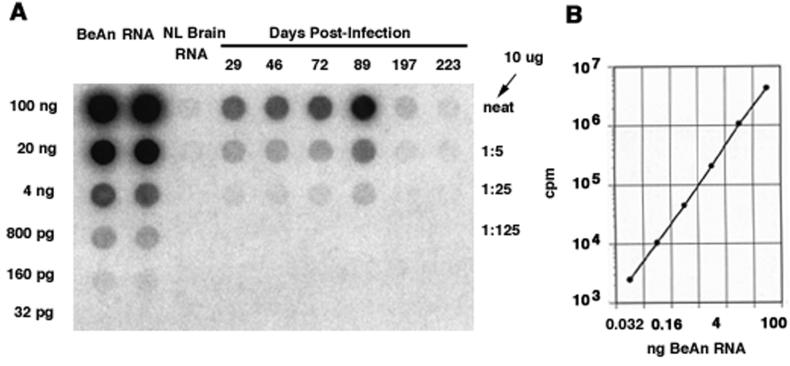

Total RNA from BeAn virus-infected mouse spinal cords was analyzed for BeAn viral genomes by using a Northern hybridization assay. RNA from infected tissues was blotted onto nitrocellulose filters along with known amounts of in vitro-transcribed BeAn viral RNA diluted in uninfected brain total RNA to generate a standard curve for the quantitation of viral RNA copies (Fig. 1A and B). Filters were scanned with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager before quantification. The detection limit for BeAn viral RNA by Northern hybridization was approximately 32 pg of RNA or 9 × 106 viral genomes (Fig. 1A and B).

FIG. 1.

Method for quantitation of BeAn genomes in individual mouse spinal cords. Total RNA was extracted from spinal cords, blotted onto nitrocellulose filters, probed with an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled BeAn virus sequence, and quantified by phosphorimaging. (A) Northern dot blot of serial fivefold dilutions of a standard in vitro-transcribed BeAn virus RNA and representative spinal cord total RNAs from infected mice killed on the indicated days p.i. (B) Standard curve derived from Northern hybridization of known amounts of in vitro-transcribed BeAn virus RNA shown in panel A. The sensitivity of this technique was 9 × 106 viral genomes.

The amount of total RNA extracted from the spinal cords of infected mice varied, depending on the age or size of the mouse. To normalize the number of BeAn viral genomes in a mouse spinal cord based on the number of genomes per microgram of total RNA, the mean amount of total RNA per spinal cord ± the standard deviation (SD) (51.90 ± 34.82 μg; n = 48) was used because, on occasion, the spinal cord was not completely extracted from the spinal canal. For example, if 1 ng or 3 × 108 genomes of BeAn was detected in 10 μg of total RNA applied to filters in a Northern blot assay, the number of viral genomes per spinal cord was calculated as (3 × 108) × 51.9 μg/10 μg, or 1.56 × 109.

High levels of BeAn RNA copies detected in the spinal cords of persistently infected SJL mice.

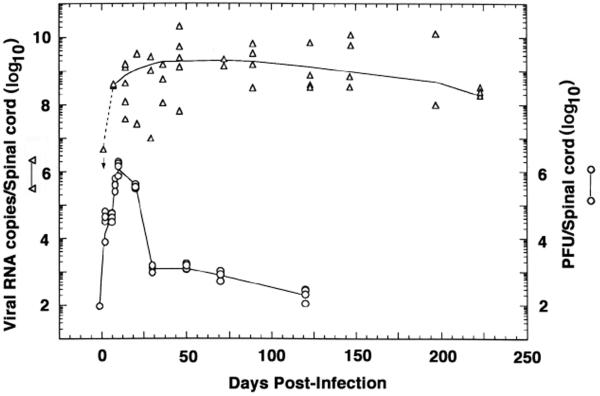

Northern hybridization revealed BeAn viral genomes in 64% (9 of 14) of the spinal cords of mice during the acute phase of infection (before p.i. day 21) and in 88% (30 of 34) of the samples during the persistent phase of infection (after p.i. day 28) (Fig. 2). The number of RNA copies increased until p.i. days 35 to 50, reaching a plateau between p.i. days 50 and 125 and slowly declining thereafter. These results demonstrate that the mean number (± the standard error) of viral genomes per cord during persistence (p.i. days 28 to 223) was (3.01 ± 0.55) × 109 (n = 30), a surprisingly large number of viral genomes during this phase.

FIG. 2.

(Top) Temporal detection of BeAn virus RNA copies in the spinal cords of infected mice using an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled BeAn sequence as a probe for Northern hybridization (left ordinate). The use of similar amounts of RNA in specimens was judged from 18S and 28S rRNAs following agarose gel electrophoresis. There was a rise in the number of viral RNA copies between p.i. days 7 and 28, as shown (the dashed line between p.i. days 0 and 7 is simulated), suggesting that active RNA viral replication is required for viral persistence, in contrast with viral infectivity (shown below). Samples with virus copy numbers below the level of detection (9 × 106 viral genomes) are not shown (two samples on day 7, three on day 21, two on day 29, one on day 36, and one on day 70). (Bottom) Temporal profile of viral infectivity (number of PFU per cord) of clarified spinal cord homogenates showing a decline in virus titers after p.i. day 14 (right ordinate).

In contrast, infectious virus remained in the range of 102 to 104 PFU per spinal cord between p.i. days 28 and 125 (Fig. 2). The ratio of viral genomes to PFU was on the order of 106:1 to 107:1 during the persistent infection phase, compared to a ratio of 103:1 during the acute infection phase, suggesting a restriction in the production of infectious virus after p.i. day 28 and/or neutralization of infectious virus by virus-specific antibodies or cellular immune responses (see below).

Size of BeAn viral genomes in the spinal cord.

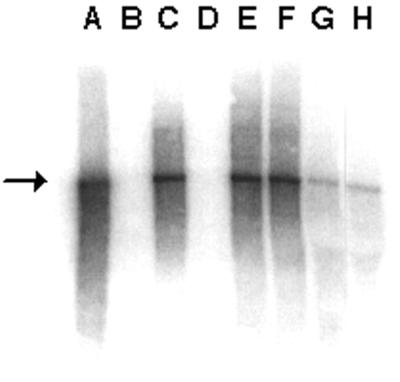

Northern hybridization to determine whether BeAn viral genomes were altered in size during the persistent phase of infection in mice revealed full-length genomes on p.i. days 46 and 70 (Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained on p.i. days 127 and 147 (data not shown). No subgenomic species were detected during the persistence phase.

FIG. 3.

Detection of full-length BeAn virus RNA genomes during persistent infection of mice. Total RNA was prepared from infected cells in culture or from mouse spinal cords. RNA was electrophoresed on a denaturing agarose gel, transferred to nylon filters, and probed with an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled BeAn virus sequence. A, 100 ng of in vitro-transcribed BeAn RNA; B, 1 μg of uninfected BHK-21 cell total RNA; C, 1 μg of BeAn virus-infected BHK-21 cell total RNA; D, 1 μg of uninfected N20 cell total RNA; E, 1 μg of BeAn virus-infected N20 cell total RNA; F, 1 μg of BeAn virus-infected M1-D cell total RNA; G, 10 μg of spinal cord total RNA at p.i. day 46; H, 10 μg of spinal cord total RNA at p.i. day 70. The arrow indicates full-length BeAn RNA.

BeAn RNA copies in brains and spinal cords of CBA and C.B-17 scid mice.

Spinal cords of CBA mice persistently infected with BeAn show more severe pathological changes than do those of SJL mice, and crystalline arrays of virions have been detected in CBA mouse oligodendrocytes (2). These observations are indicative of a cytolytic infection of oligodendrocytes, where larger numbers of viral RNA copies are expected. BeAn infection of C.B-17 scid mice, lacking humoral and cellular immune viral clearance mechanisms (28), would also be expected to produce larger numbers of viral genomes than in SJL mice. Northern hybridization analysis of 8 CBA and 10 C.B-17 scid mice inoculated i.c. with virus (all of the CBA mice but only 6 of the C.B-17 mice survived for more than 21 days p.i.) revealed viral genome loads in their spinal cords (Table 1) similar to those in the spinal cords of SJL mice (Fig. 2). However, C.B-17 scid mice had on the order of 1011 RNA copies in the brain, in contrast to the <107 RNA copies found in those of SJL mice at a comparable time (Table 1). These results not only point to the persistence of TMEV primarily in the spinal cord but show that in an immunodeficient host, virus replication also takes place in the brain during the persistent phase of infection.

TABLE 1.

Abundance of BeAn viral genomes in the CNS of infected CBA and C. B-17 scid mice

| Mouse strain | Day p.i. | No. of CNS samples | Viral copy no.a

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spinal cord | Brain | |||

| CBA | 35 | 4 | 4.18 × 108 ± 2.8 | NDb |

| 44 | 4 | 2.13 × 109 ± 2.4 | ND | |

| C.B-17 scid | 20 | 1 | <107c | 9.3 × 1010 |

| 22 | 1 | 6.5 × 108 | 4.7 × 1011 | |

| 24 | 1 | 1.8 × 108 | 1.9 × 1011 | |

| 29 | 1 | 1.5 × 109 | 1.4 × 1011 | |

| 31 | 1 | 1.2 × 109 | 1.5 × 1011 | |

| SJL | 29 | 4 | NDd | <107 |

Mean ± SD.

ND, not done.

The detection limit of the Northern dot blot assay is 9 × 106 viral genomes per 10 μg of total RNA.

Please refer to Fig. 2 for similar data.

BeAn viral genome loads in oligodendrocytes and macrophages in culture.

Immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization analyses of spinal cords from mice persistently infected with TMEV indicate that the majority of infected cells in the spinal cord are macrophages, although oligodendrocytes and astrocytes may also be infected (1, 24). To provide information on the viral genome loads in specific infected cells in the mouse CNS, we measured the viral genome loads in a murine myelomonocytic cell line (M1) differentiated into macrophages (M1-D) (20) and a mature murine oligodendrocyte cell line, N20 (12); astrocytes were not tested because few have been detected in demyelinating lesions in BeAn virus-infected SJL mice and none of those were infected (24, 33). Cells were infected with BeAn virus at a high multiplicity, and viral RNA copies synthesized at 8 h p.i., i.e., the peak of viral RNA replication (data not shown), were analyzed by Northern hybridization and infectious virus was measured by standard plaque assay (Table 2). Lytic BeAn virus infection of BHK-21 cells, used as a control cell population, has been demonstrated (19). Each infected M1-D cell synthesized approximately 3 × 105 viral genomes, an amount similar to that in BHK-21 cells; however, the production of infectious virus was markedly reduced (5 PFU per M1-D cell, compared to 350 PFU per BHK-21 cell). In N20 cells, the number of viral RNA genomes and the level of infectious virus were similar to those in BHK-21 cells. Only full-length viral genomes were detected in these cell lines (Fig. 3). Thus, while both macrophages and oligodendrocytes can produce large numbers of TMEV genomes, infection in macrophages is restricted, with a block after viral RNA replication.

TABLE 2.

Abundance of BeAn viral genomes produced during infectiona of cell lines

| Cell line | No. of platesb | Amt (ng) of BeAn RNA/μg of cell RNA | Mean no. of genomes/ cell ± SD | No. of PFU/ cell | No. of genomes/ PFU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHK-21 | 3 | 95 | 3.46 × 105 ± 2.27 × 105 | 350 | 1,040 |

| N20c | 3 | 263 | 8.40 × 104 ± 4.80 × 104 | 200 | 420 |

| M1-Dd | 3 | 179 | 2.59 × 105 ± 0.95 × 105 | 5 | 5.18 × 104 |

High-multiplicity infection was stopped at 8 h when a cytopathic effect was present.

Monolayers were grown in 100-mm-diameter plates.

Mature murine oligodendrocyte cell line (note that the yield of total RNA per cell is 20-fold less than for the other two cell lines).

Differented murine macrophage cell line.

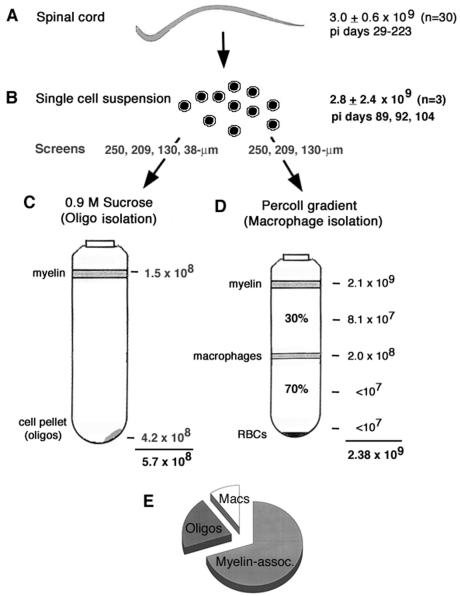

Viral genome loads in oligodendrocytes and macrophages isolated from infected spinal cords.

The viral genome loads in specific cell types were analyzed by using spinal cords from four to eight infected mice sacrificed at each time point between p.i. days 60 and 120, when mononuclear infiltration and demyelination of white matter are extensive (M. Felrice, P. Kallio, R. Ramesh, and H. L. Lipton, submitted for publication). Single-cell suspensions were generated from the cords by collagenase treatment. The mean numbers of genomes in the whole spinal cord (3.0 × 109) (Fig. 4A) and in single-cell suspensions (2.8 × 109) (Fig. 4B) were similar, indicating that cells could be dissociated from the spinal cord without loss of viral RNA copies.

FIG. 4.

Method used to isolate oligodendrocytes and macrophages from spinal cords of persistently infected SJL mice. The viral RNA copy number determined by Northern hybridization is indicated at each step. (A) During the persistent phase of infection, the mean number (± SD) of viral genomes in whole spinal cords was 3.0 × 109 ± 0.6 × 109 (n = 30; data from Fig. 2). (B) The mean number (± SD) of viral genomes in single-cell suspensions after collagenase treatment of minced spinal cords, including cells in efflux from PBS-forced flushing of spinal canals, was 2.8 × 109 ± 2.4 × 109 (n = 3). (C) Representative experiment for isolation of oligodendrocytes by centrifugation through 0.9 M sucrose (most of the macrophages were eliminated from this gradient by passage of cells through a 38-μm screen). (D) Isolation of macrophages in Percoll gradients at the 30 to 70% interface (since only larger-pore-size screens were used to dissociate the cells, all of the cell types were present in this gradient). (E) Distribution of the viral genome load based on the combined data in panels C and D, i.e., 18% in oligodendrocytes (Oligos; 4.2 × 108/2.38 × 109), 8% in macrophages (Macs; 2.0 × 108/2.38 × 109), and 74% in the myelin fraction at the top of Percoll gradient (2.1 × 109/2.38 × 109 to 4.2 × 108/2.38 × 109). RBCs, red blood cells; assoc., associated.

Single-cell suspensions were then used to isolate either oligodendrocytes or macrophages by centrifugation through a sucrose or Percoll gradient, respectively; no similar method exists for direct isolation of astrocytes without incubation in vitro for 1 to 2 weeks at 37°C and the use of neonatal rather than adult rodents (35). Oligodendrocytes were isolated by passing the single-cell suspension through screens of graded sizes (250 to 38 μm), followed by pelleting through 0.9 M sucrose (Fig. 4C) and then panning on plastic to eliminate any remaining macrophages. Passage through the 38-μm-diameter screen not only dissociated oligodendrocytes from myelin membranes but also eliminated most macrophages (40). Two-thirds of the viral genomes were in the cell pellet rather than in the myelin layer after centrifugation of oligodendrocytes through 0.9 M sucrose. This number is equivalent to 18% of the total viral genome load in the experiment whose results are shown (Fig. 4E, legend).

Macrophages were isolated by passing the single-cell suspension through graded-size screens (250 to 130 μm) (Fig. 4D) and centrifugation through a discontinuous Percoll gradient, which left oligodendrocytes in the macrophage gradients (Fig. 4D). The majority (74%) of the viral genome load was found in the myelin fraction at the top of the gradient, while only 8% of viral genomes were found in the macrophage fraction at the 30 to 70% Percoll interface (Fig. 4E, legend). Table 3 gives the viral genome loads found in additional isolation experiments.

TABLE 3.

Abundance of BeAn viral genomes in oligodendrocytes and macrophages isolated from spinal cords of infected SJL mice

| Cell type and day p.i. | No. of micea | No. of cells/ mouseb (104) | No. of viral genomes/mouse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligodendrocytes | |||

| 72 | 4 | 45 | 1.85 × 107 |

| 101 | 4 | 55 | 4.75 × 107 |

| 111 | 4 | 76 | 6.5 × 108 |

| Macrophages | |||

| 60 | 8 | 15.6 | 5.48 × 107 |

| 81 | 8 | 9.9 | 2.46 × 107 |

| 85 | 6 | 24.2 | 4.63 × 107 |

| 137 | 6 | 19.5 | 1.36 × 108 |

The cells obtained from these mice were pooled.

Number of isolated oligodendrocytes or macrophages per mouse cord.

Since the majority of the viral load in the Percoll gradient was in the myelin debris, we analyzed the myelin debris by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig 5A and B, we were able to distinguish between myelin profiles and nucleated cells by using 7-ADD, a DNA stain, which revealed a number of cells in the myelin layer at the top of the Percoll gradient (1.97 × 106) equivalent to that in the macrophage fraction in Fig. 4D (1.60 × 106). Flow cytometry showed that one-fourth of the 7-ADD-stained cells in the myelin layer were macrophages, a number equivalent to that in the macrophage fraction (Fig. 5C and D), while only a small percentage were oligodendrocytes (data not shown). Therefore, an additional 8% of the viral genome load may have been present in macrophages trapped in the myelin debris. However, two-thirds of the cells from the single-cell suspensions were consistently lost on gradients (data not shown). Therefore, a large portion of the viral genome load in the myelin layer probably represents viral RNA released from lysed cells and adhering to myelin or sedimenting at the top of the gradient.

FIG. 5.

Flow cytometric analysis of cells in the myelin fraction at the top of the Percoll gradient in Fig. 4D. (A) Combined fluorescence and light photomicrograph of an aliquot of the myelin fraction allowed to settle onto a slide. Three nucleated cells stained with 7-AAD (anti-DNA) are shown amid many unstained myelin profiles. Aggregation of myelin profiles is, in part, due to settling and superimposition of some profiles. Magnification, ×400. (B) Forward- and side-scatter characteristics of the two components (cells and myelin profiles) in the myelin fraction indicative of size and granularity. (C) Forward- and side-scatter characteristics of 7-AAD-gated cells. Not shown is separation of the two components on the 7-AAD forward-scatter dot plot that enabled nucleated cells to be gated. (D) Dot plot of 7-AAD-gated cells in panel C stained with MOMA-2 (cytoplasmic staining) and goat anti-rat immunoglobulin G-FITC. Quadrants are set on cells stained only with the secondary antibody.

Ratio of plus- to minus-strand viral RNA in infected spinal cords.

Picornaviruses synthesize 30 to 70 plus strands for each minus strand, a ratio that can serve as a measure of picornavirus RNA replication in an acute cytolytic infection (14, 29). The ratio of BeAn virus plus- to minus-strand RNA was in the range of 35:1 to 38:1 in BHK-21 cells, murine oligodendrocytes (N20), and differentiated macrophages (M1-D) (Table 4). Similar ratios were found in the spinal cords of persistently infected SJL mice. Thus, plus-strand viral RNA replication appears to be unperturbed in the mouse spinal cord and, taken together with the high viral genome load, this suggests that viral RNA replication is most likely normal in oligodendrocytes and macrophages in the spinal cord.

TABLE 4.

Ratios of plus- to minus-strand BeAn viral RNA in infected cells

| Cells | Ratios in individual expts | Mean ratio ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| BHK-21 | 23.9:1, 52:1, 40:1, 32:1 | 36.9 ± 12:1 |

| N20a | 22:1, 43:1, 49:1 | 38 ± 8.2:1 |

| M1-Db | 28:1, 26.5:1, 54:1, 40.7:1, 24.2:1 | 34.6 ± 12.5:1 |

| CNS cellsc | 31.1:1, 10:1, 14.6:1, 53.2:1 | 27.2 ± 19.5:1 |

Mature murine oligodendrocyte cell line.

Differented macrophage cell line derived from murine M1 cells.

Single-cell suspensions derived from the spinal cords of infected SJL mice at p.i. day 114. Isolated cells were pooled from two mice for each determination.

DISCUSSION

A heavy BeAn viral genome load but low levels of infectivity in the spinal cord during persistence.

Historically, TMEV persistence in susceptible mice has been determined by the recovery of infectious virus from spinal cords. Results of infectivity assays have led to the belief that TMEV persists at only low levels in the CNS and that infection is highly restricted at one or more steps in the viral life cycle. Northern hybridization analysis of viral genomes in total RNA extracted from spinal cords has provided a semiquantitative method that allows comparison of the amounts of TMEV RNA in different animals (3, 21). However, a linkage between detection of TMEV RNA and the total genome load has never been made. In this study, we used Northern hybridization to quantify viral genomes in TMEV-infected mouse spinal cords, the principal site of viral persistence. Between 108 and 1010 viral RNA copies were present in spinal cords of infected mice (mean, 3 × 109 genomes per spinal cord), even as late as p.i. day 223 (Fig. 2). These genome levels were unexpected but not without precedent. In persistent infections of other RNA viruses, e.g., human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) in humans (32), simian immunodeficiency virus in macaques (17, 41), chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency virus in macaques (15), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) in humans (38, 43), levels between 106 and 108 viral RNA copies per ml of plasma have been demonstrated. In fact, virus turnover rates in HIV-1 and HCV infections are remarkably similar and have been calculated to be on the order of 1010 virions per day (18, 42, 43). Half-life data acquired based on the use of antiviral inhibitors suggest that HIV-1 and HCV replicate continuously in vivo; analogous studies should help to determine whether this is also the case for TMEV persistence in mice.

In contrast to the heavy viral genome load found during TMEV persistence, levels of ≤104 PFU per cord have been detected by most investigators (for example, see references 6 and 23). Thus, the ratio of viral RNA copies to PFU during persistence is on the order of 106:1, or 3 orders of magnitude higher than that observed in acutely infected spinal cords, i.e., 5 × 103 (Fig. 2). This value for acutely infected spinal cords is in close accord with the particle-to-PFU ratio of 3.19 × 103 for BeAn virus infection of BHK-21 cells (16; also Table 2). The disparity between the viral genome load and infectious virus during persistence in vivo remains unexplained but probably reflects the neutralization of infectious virus by virus-specific antibodies and CD4+ T cells (CD8+ T cells do not appear to limit TMEV replication during persistent infection in susceptible mouse strains; 11, 22), as well as the restricted production of infectious virus by CNS macrophages, the predominant cell type supporting TMEV replication (24, 30). The effect of immune responses on the viral RNA-to-PFU ratio during persistence can be seen by using the DA virus-infected C.B-17 cord virus titers provided by Njenga et al. (28) at their latest time (day 13); in this case, ratios would be more on the order of 103:1. Restriction of TMEV infection has been reported in macrophages isolated from the mouse CNS (10) and in infected murine macrophages in culture, where a block in virus assembly rather than a block in viral RNA replication most likely accounts for the low levels of infectious virus in the face of substantial amounts of virus antigen (19, 39). The block in infectious TMEV production in the macrophage cell line M1-D contrasts with the productive infection in mature murine oligodendrocytes seen in this study (Table 2).

BeAn viral RNA replication is not restricted or aberrant during persistence.

Analysis of TMEV genome size in RNA extracted from persistently infected spinal cords revealed only full-length species (Fig. 3), indicating that subgenomic RNAs, such as those in defective-interfering (DI) particles, are not produced during persistent infection. This observation is consistent with the apparent resistance against the production of DI particles of picornaviruses compared to other RNA viruses, possibly due to a requirement for cis-acting elements within the capsid coding region for RNA replication (25–27). Furthermore, picornaviruses generally require many serial passages in cells for DI formation (reviewed in reference 7).

The ratios of TMEV RNA plus to minus strands were similar in cultures of macrophages, oligodendrocytes, and BHK-21 cells (approximately 35:1; Table 4) and consistent with the ratio reported for human poliovirus infection of HeLa cells (14, 29). The similar ratio in CNS cells suggests that TMEV RNA replication is not restricted during persistent infection, although this does not exclude this possibility in a single cell type, e.g., macrophages or glial cells. Cash et al. (5), using strand-specific probes and in situ hybridization, also demonstrated that the plus- to minus-strand ratio in spinal cord sections of DA virus-infected mice was similar to that in infected BHK-21 cells. However, those authors concluded that minus-strand synthesis was restricted, based in part on the low numbers of TMEV copies detected. In that study, the majority of infected cells in the spinal cord contained only 100 to 500 copies, with a small percentage containing as many as 9,000 copies. Subsequently, these methods were reported to have underestimated the number of TMEV RNA copies in cells (4). By contrast, our data indicate >105 viral RNA copies in oligodendrocytes and macrophages in culture and >109 copies per spinal cord. Although the number of infected cells is unknown, the genome load in spinal cords of infected mice is difficult to explain unless high numbers of TMEV RNA copies are present in most infected cells. Together, these data suggest that TMEV RNA replication is not restricted during the persistent phase of infection.

BeAn viral genome load in the spinal cord does not increase in an immunodeficient host.

The heavy viral load in the spinal cords of persistently infected SJL mice led us to expect even higher numbers of viral genomes in C.B-17 scid mice, which lack humoral and cellular immune clearance mechanisms and in which infectious titers are high (28), and in CBA mice, in which crystalline arrays of Theiler's virions indicative of productive infection have been observed in oligodendrocytes during persistent infection (2). Analysis of the viral load in these mouse strains revealed viral genome levels in the spinal cord similar to those in SJL mice. These results provide further evidence that viral RNA replication is not restricted in the spinal cords of SJL mice. However, cells in which TMEV replicates must differ in immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice, since macrophages infiltrating the spinal cord and serving as a major site of viral persistence in SJL mice are not observed in TMEV-infected C.B-17 scid mice (28). Interestingly, the viral load in the brains of C.B-17 scid mice was extraordinarily heavy, with viral RNA copies representing 0.3% of the total brain mRNA, in contrast to the undetectable viral genome levels in the brains of SJL mice, illustrating the effect of the immune system on BeAn virus replication in the brain.

BeAn virus persistence involves active viral RNA replication.

The infectivity plot in Fig. 2, indicating a logarithmic decline in infectious virus after the acute growth phase and a slow decline thereafter, suggests a restricted infection. By contrast, the temporal curve showing viral RNA copies indicated active and probably continuous viral RNA replication in TMEV persistence. In the transition from the acute (approximately p.i. day 7) to the persistent (beginning on p.i. day 28) phase of infection, viral RNA copy numbers steadily increased. This is the time frame in which the site of infection in the spinal cord shifts from gray to white matter, and macrophage infiltration (and demyelination) is first observed in white matter. The mechanism(s) underlying the shift in sites of infection are still unknown but may hinge on the developing virus-specific immune responses that limit viral spread during this time and on exclusive infiltration of white matter by macrophages. These data suggest that the rise in the number of viral RNA copies is due principally to replication in macrophages; however, further analysis of the temporal kinetics of viral RNA replication between p.i. days 7 and 28 is needed, including more time points and immunohistochemical analysis to relate these data to the extent of macrophage infiltration.

The scheme we used to isolate the two principal target cell populations, macrophages and oligodendrocytes, and determine the viral genome load more reliably than by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization was hampered by significant cell losses in cell recovery from gradients, including trapping of both cells and viral RNA from lysed cells in myelin debris. While infection of oligodendrocytes accounted for approximately 20% of the viral genome load in the gradients and a similar percentage by infection of macrophages, the rest of the viral genome load could not be assigned. Nonetheless, our isolation techniques do allow recovery of relatively pure populations of macrophages and oligodendrocytes and will enable further examination of TMEV infection in these cells taken directly from the spinal cord.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Matt Felrice and Brian Schlitt for technical assistance and Mary Lou Jelachich for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grant NS 37732 and The Leiper Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aubert C, Chamorro M, Brahic M. Identification of Theiler's virus infected cells in the central nervous system of the mouse during demyelinating disease. Microb Pathog. 1987;3:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blakemore W F, Welsh C J, Tonks P, Nash A A. Observations on demyelinating lesions induced by Theiler's virus in CBA mice. Acta Neuropathol. 1988;76:581–589. doi: 10.1007/BF00689596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bureau J-F, Montagutelli X, Lefebvre S, Guenet J L, Pla M, Brahic M. The interaction of two groups of murine genes determines the persistence of Theiler's virus in the central nervous system. J Virol. 1992;66:4698–4704. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4698-4704.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cash E, Brahic M. Quantitative in situ hybridization using initial velocity measurements. Anal Biochem. 1986;157:266–270. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90620-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cash E, Chamorro M, Brahic M. Minus-strand RNA synthesis in the spinal cords of mice persistently infected with Theiler's virus. J Virol. 1988;62:1824–1826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.5.1824-1826.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamorro M, Aubert C, Brahic M. Demyelinating lesions due to Theiler's virus are associated with ongoing central nervous system infection. J Virol. 1986;57:992–997. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.3.992-997.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charpentier N, Davila M, Domingo E, Escarmis C. Long-term, large-population passage of aphthovirus can generate and amplify defective noninterfering particles deleted in the leader protease gene. Virology. 1996;223:10–18. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen B, Przybala A E. An efficient site-directed mutagenesis method based on PCR. BioTechniques. 1994;17:657–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clatch R J, Lipton H L, Miller S D. Characterization of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity responses in TMEV-induced demyelinating disease: correlation with clinical signs. J Immunol. 1986;136:920–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clatch R J, Miller S D, Metzner R, Dal Canto M C, Lipton H L. Monocytes/macrophages isolated from the mouse central nervous system contain infectious Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) Virology. 1990;176:244–254. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90249-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dethlefs S, Brahic M, Larsson-Sciard E-L. An early, abundant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response against Theiler's virus is critical for preventing viral persistence. J Virol. 1997;71:8875–8878. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8875-8878.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster L M, Phan T, Verity A N, Bredesen D, Campagnoni A T. Generation and analysis of normal and shiverer temperature-sensitive immortalized cell lines exhibiting phenotypic characteristics of oligodendrocytes at several stages of differentiation. Dev Neurosci. 1993;15:100–119. doi: 10.1159/000111322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerety S J, Rundell K M, Dal Canto M C, Miller S D. Class II-restricted T cell responses in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelinating disease. VI. Potentiation of demyelination with and characterization of an immunopathologic CD4+ T cell line specific for an immunodominant VP2 epitope. J Immunol. 1994;152:919–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giachetti C, Semler B L. Role of a viral membrane polypeptide in strand-specific initiation of poliovirus RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1991;65:2647–2654. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2647-2654.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haaft P T, Verstrepen B, Uberla K, Rosenwirth B, Heeney J. A pathogenic threshold of virus load in simian immunodeficiency virus- and simian-human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Virol. 1998;72:10281–10285. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10281-10285.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertzler S, Luo M, Lipton H L. Mutation of predicted virion pit residues alters binding of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus to BHK-21 cells. J Virol. 2000;74:1994–2004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1994-2004.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsch V M, Fuerest T R, Sutter G, Carroll M W, Yang L C, Goldstein S, Piatek M, Jr, Elkins W R, Montefiori D C, Moss B, Lifson J D. Patterns of viral replication correlate with outcome in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques: effect of prior immunization with a trivalent SIV vaccine in modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J Virol. 1996;70:3741–3752. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3741-3752.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho D D, Neumann A U, Perelson A S, Chen W, Leonard J M, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jelachich M L, Bandyopadhyay P, Blum K, Lipton H L. Theiler's virus growth in murine macrophage cell lines depends on the state of differentiation. Virology. 1995;209:437–444. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jelachich M L, Brumlage C, Lipton H L. Differentiation of M1 myeloid precursor cells into macrophages results in binding and infection by Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus and apoptosis. J Virol. 1999;73:3227–3235. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3227-3235.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsson-Sciard E L, Dethlefs S, Brahic M. In vivo administration of interleukin-2 protects susceptible mice from Theiler's virus persistence. J Virol. 1997;71:797–799. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.797-799.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin X, Pease L R, Murray P D, Rodriguez M. Theiler's virus infection of genetically susceptible mice induces central nervous system-infiltrating CTLs with no apparent viral or major myelin antigenic specificity. J Immunol. 1998;160:5661–5668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipton H L, Melvold R. Genetic analysis of susceptibility to Theiler's virus-induced demyelinating disease in mice. J Immunol. 1984;132:1821–1825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipton H L, Twaddle G, Jelachich M L. The predominant virus antigen burden is present in macrophages in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelinating disease. J Virol. 1995;69:2525–2533. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2525-2533.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lobert P-E, Escriou N, Ruelle J, Michiels T. A coding RNA sequence acts as a replication signal in cardioviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11560–11565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKnight K L, Lemon S M. Capsid coding sequence is required for efficient replication of human rhinovirus 14 RNA. J Virol. 1996;70:1941–1952. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1941-1952.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKnight K L, Lemon S M. The rhinovirus type 14 genome contains an internally located RNA structure that is required for viral replication. RNA. 1998;4:1569–1584. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298981006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Njenga M K, Asakura K, Hunter S F, Wettstein P, Pease L R, Rodriguez M. The immune system preferentially clears Theiler's virus from the gray matter of the central nervous system. J Virol. 1997;71:8592–8601. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8592-8601.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novak J E, Kirkegaard K. Improved method for detecting poliovirus negative strands used to demonstrate specificity of positive-strand encapsidation and the ratio of positive to negative strands in infected cells. J Virol. 1991;65:3384–3387. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.3384-3387.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pena Rossi C, Delcroix M, Huitinga I, McAllister A, van Rooijen N, Claassen E, Brahic M. Role of macrophages during Theiler's virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:3336–3340. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3336-3340.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pevear D C, Calenoff M, Rozhon E, Lipton H L. Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of the picornavirus Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus indicates that it is closely related to cardioviruses. J Virol. 1987;61:1507–1516. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1507-1516.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piatek M, Jr, Saag M S, Yang L C, Clark S J, Kappes J C, Luk K-C, Hahn B H, Shaw G M, Lifson J D. High levels of HIV-1 in plasma during all stages of infection determined by competitive PCR. Science. 1993;259:1749–1754. doi: 10.1126/science.8096089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pope J G, Karpus W J, VanderLugt C, Miller S D. Flow cytometric and functional analyses of central nervous system-infiltrating cells in SJL/J mice with Theiler's virus-induced demyelinating disease. J Immunol. 1996;156:4050–4058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pope J G, Vanderlugt C L, Rahbe S M, Lipton H L, Miller S D. Characterization of and functional antigen presentation by central nervous system mononuclear cells from mice infected with Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus. J Virol. 1998;72:7762–7771. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7762-7771.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radany E H, Brenner M, Besnard F, Bigornia V, Bishop J M, Deschepper C F. Directed establishment of rat brain cell lines with the phenotypic characteristics of type 1 astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6467–6471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez M, Leibowitz J L, Lampert P W. Persistent infection of oligodendrocytes in Theiler's virus-induced encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:426–433. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozhon E J, Kratochvil J D, Lipton H L. Analysis of genetic variation in Theiler's virus during persistent infection in the mouse central nervous system. Virology. 1983;128:16–32. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruster B, Zeuzem S, Roth W K. Quantification of hepatitis C virus RNA by competitive reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction using a modified hepatitis C virus transcript. Anal Biochem. 1995;224:597–600. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw-Jackson C, Michiels T. Infection of macrophages by Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus is highly dependent on their activation or differentiation state. J Virol. 1997;71:8864–8867. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8864-8867.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szuchet S, Arnason B G W, Polak P. Separation of ovine oligodendrocytes into two distinct bands on a linear sucrose gradient. J Neurosci Methods. 1980;3:7–19. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(80)90030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson A, Ranchais J, Travis B, McClure J, Sutton W, Johnson P R, Hu S-L, Haigwood N L. Plasma viremia in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasma viral load early in infection predicts survival. J Virol. 1997;71:284–290. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.284-290.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei X, Ghosh S K, Taylor M E, Johnson V A, Emini E A, Deutsch P, Lifson J D, Ronhoeffer S, Nowak M A, Hahn B H, Saag M S, Shaw G M. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeuzem S, Schmidt J M, Lee J-H, Ruster B, Roth W K. Effect of interferon alpha on the dynamics of hepatitis C virus turnover in vivo. Hepatology. 1996;23:366–371. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]