Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Evidence has emerged that cardiometabolic multimorbidity (CMM) is associated with dementia, but the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood.

METHODS

This population‐based study included 5704 older adults. Of these, data were available in 1439 persons for plasma amyloid‐β (Aβ), total tau, and neurofilament light chain (NfL) and in 1809 persons for serum cytokines. We defined CMM following two common definitions used in previous studies. Data were analyzed using general linear, logistic, and mediation models.

RESULTS

The presence of CMM was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of dementia, Alzheimer's disease (AD), and vascular dementia (VaD) (p < 0.05). CMM was significantly associated with increased plasma Aβ40, Aβ42, and NfL, whereas CMM that included visceral obesity was associated with increased serum cytokines. The mediation analysis suggested that plasma NfL significantly mediated the association of CMM with AD.

DISCUSSION

CMM is associated with dementia, AD, and VaD in older adults. The neurodegenerative pathway is involved in the association of CMM with AD.

Highlights

The presence of CMM was associated with increased likelihoods of dementia, AD, and VaD in older adults.

CMM was associated with increased AD‐related plasma biomarkers and serum inflammatory cytokines.

Neurodegenerative pathway was partly involved in the association of CMM with AD.

Keywords: cardiometabolic multimorbidity, dementia, neurodegeneration, plasma Alzheimer's biomarkers, population‐based study, serum cytokines

1. BACKGROUND

Dementia, a leading cause of functional disability among older adults, has reached epidemic proportions as the global population ages. 1 In China, the prevalence of dementia among individuals aged ≥60 years was around 6.0%, and the prevalence has been increasing since the 1990s. 2 , 3 Notably, the prevalence and incidence of dementia are both higher in rural than in urban populations in China, which might be partially attributed to the disparities between rural and urban residents in socioeconomic status (e.g., educational attainment and income), healthcare system, and management of cardiometabolic risk factors. 2

There is currently no cure for dementia. Identifying modifiable risk factors for dementia is crucial to the development of preventive interventions. Cardiometabolic diseases (CMDs), such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke, have been associated with an increased risk of dementia. 4 , 5 , 6 However, most of the previous studies have examined individual CMDs in association with dementia. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity (CMM), defined as concurrent presence of two or more CMDs, is highly prevalence in older people. 7 Previous studies have shown that CMM is predictive of multiple adverse health outcomes, such as mortality, 8 functional disability, 9 and depression. 10 In recent years, several population‐based studies have explored the association of CMM with cognitive phenotypes. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 For instance, data from the UK Biobank demonstrated that CMM was associated with an increased risk of dementia and poor cognitive performance, especially in processing and reasoning domains. 11 , 13 In addition, evidence from the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care–Kungsholmen (SNAC‐K) suggested that CMM could accelerate cognitive decline and progression to dementia. 12 These findings were further supported by pooled data from four large‐scale cohort studies across 14 countries. 14 However, the existing studies have been conducted primarily among Northern American and European populations. Given the global disparities in health and healthcare systems, especially the global rural health disparities in Alzheimer's disease (AD) and related dementias, 15 research findings from populations in high‐income countries and urban areas might not be generalizable to rural populations in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Furthermore, the extent to which CMM is associated with the main subtypes of dementia remains largely understudied. In addition, different definitions of CMM have been used in the current literature. Some previous studies have defined CMM based on three CMDs (i.e., diabetes, myocardial infarction, and stroke), 12 whereas others also include obesity as a CMD. 16 It is unclear to what extent variations in the definition of CMM may affect the association of CMM with dementia and subtypes of dementia.

In addition, the potential mechanisms underlying the association between CMM and cognitive phenotypes remain unclear. Chronic systemic inflammation associated with CMDs could modulate the metabolism of amyloid‐β (Aβ) and facilitate neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration 17 and, thus, may contribute to the development of dementia. Indeed, previous studies have shown that some cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes) are associated with AD‐related pathology in the brain. 18 However, the association of CMM with peripheral AD‐related biomarkers and inflammatory biomarkers has not yet been examined, and the extent to which these peripheral biomarkers may mediate the association of CMM with dementia remains unclear.

Using the data‐driven approach, we previously reported that metabolic cluster of multimorbidity (e.g., hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and chronic kidney disease) was associated with dementia, and vascular dementia (VaD) in particular. 19 In this population‐based study, we sought (1) to examine the association of CMM with all‐cause dementia, AD, VaD, and peripheral AD‐related and inflammatory biomarkers among older adults who were living in rural communities in China, and further (2) to explore the potential mediation effect of peripheral biomarkers in the CMM‐dementia/AD associations. We hypothesized that, depending on the definition of CMM, the presence and load of CMM might be differentially associated with dementia and subtypes of dementia, and that peripheral AD‐related and inflammatory biomarkers might partly mediate the association.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study participants

This was a population‐based cross‐sectional study. The study participants were derived from the Multimodal Interventions to delay dementia and disability in rural China (MIND‐China), which is a participating project in the World‐Wide FINGERS Network, a global network for risk reduction and prevention of dementia. 20 Briefly, MIND‐China engaged rural residents who were aged ≥60 years by the end of 2017 and living in the 52 villages of Yanlou Town, Yanggu County, western Shandong Province. In March–September 2018, a total number of 5765 residents (74.9% of all eligible persons) participated in the interdisciplinary baseline assessments, as previously reported. 20 Of these, we excluded 61 participants due to major psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, n = 8) and missing data on heart disease (n = 12), stroke (n = 3), and obesity (n = 38), leaving 5704 persons to study the associations of CMM with all‐cause dementia and subtypes of dementia. Of these, data on plasma biomarkers for amyloid and neurodegeneration were available in 1439 persons, which consisted of the plasma AD‐related biomarker subsample. In addition, serum inflammatory cytokines were measured in 1857 persons; of these, we excluded 48 participants due to the value below the limit of detection (n = 1) and outliers (outside three standard deviations [SDs] away from the mean, n = 47) in any of the three serum cytokines, that is, interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), interleukin‐8 (IL‐8), and tumor necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α), leaving 1809 persons for the analysis involving serum cytokines. The two peripheral biomarker subsamples were randomly selected using a cluster (village)‐based sampling approach from all the 52 villages of Yanlou Town plus participants who had blood samples available and who were diagnosed with AD (for plasma AD‐related biomarker subsample) or dementia (for serum inflammatory biomarker sample) from all the villages that were not randomly selected, as previously reported. 21 Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the study participants.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the study participants. IL‐6, interleukin‐6; LOD, limit of detection; MIND‐China, Multimodal Intervention to Delay Dementia and Disability in Rural China; NfL, neurofilament light chain; SD, standard deviation.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: We searched PubMed for relevant literature. Evidence from a few population‐based studies has emerged that cardiometabolic multimorbidity (CMM) is associated with dementia. However, the association of CMM with dementia among rural Chinese older adults has yet to be explored, and the mechanisms underlying their association remain poorly understood.

Interpretation: This population‐based cross‐sectional study showed that the presence of CMM was associated with increased likelihoods of dementia, Alzheimer's disease (AD), and vascular dementia in rural‐dwelling older adults. In addition, CMM was associated with increased AD‐related plasma biomarkers (i.e., plasma amyloid‐β [Aβ]40, Aβ42, and neurofilament light chain [NfL]) and increased serum cytokines (e.g., interleukin‐6 [IL‐6], tumor necrosis factor‐ α [TNF‐α], and high levels of low‐grade inflammation). We further revealed that neurodegenerative pathway was partly involved in the association of CMM with AD.

Future directions: Future prospective cohort studies are warranted to clarify the temporal relationship of CMM with subsequent cognitive disorders and the underlying mechanisms, which may provide further evidence for preventive and therapeutic interventions by targeting CMM to delay the onset of dementia in rural older adults.

Compared with participants without data on peripheral biomarkers, those included in the biomarker samples were slightly younger and more likely to be women, smoke, be physically inactive, and have heart disease or stroke (p < 0.05), but those without and with data on peripheral biomarkers did not differ significantly in the distribution of apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype and other demographic factors, lifestyles, and health conditions (Supplemental Materials Table S1 and Table S2).

The MIND‐China protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at Shandong Provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong University in Jinan, Shandong, China. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants or informants. MIND‐China was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (registration no.: ChiCTR1800017758).

2.2. Assessment and definition of cardiometabolic diseases and multimorbidity

The following four CMDs were included in defining CMM: type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and visceral obesity. 22 , 23 Heart disease included ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure, which were ascertained according to self‐reported history of respective disorders or electrocardiographic (ECG) examination. 24 Type 2 diabetes was ascertained on the basis of self‐reported history of diabetes diagnosed by a physician or fasting blood glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L or current use of blood glucose‐lowering medication. Stroke was identified based on self‐reported history of stroke, clinical and neurological examinations, and medical records. Given the fact that visceral obesity as an independent risk marker for cardiovascular and metabolic morbidity and mortality is superior to body mass index (BMI), 25 , 26 , 27 we included visceral obesity, instead of BMI, as a CMD in one of the two CMM definitions. Visceral adiposity index was a sex‐specific index based on waist circumference (WC), BMI, triglycerides, and high‐density lipoprotein (HDL). 25 Visceral obesity was defined as visceral adiposity index ≥1.93 (age 60‐65 years) and ≥2.00 (age ≥66 years). 25 , 28

We defined CMM according to two definitions proposed in previous studies, that is, CMM was defined by concurrent presence of two or more CMDs over the three CMDs (i.e., type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke) (CMM‐I) 12 , 23 or over the four CMDs (i.e., visceral obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke) (CMM‐II). 14 , 16

2.3. Diagnosis of dementia, AD, and VaD

Dementia was clinically diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV), criteria, 29 in which a three‐step diagnostic procedure was followed, as previously reported. 20 In brief, trained clinicians and interviewers performed the first face‐to‐face interview, clinical examination, neurocognitive testing, and assessment of activities of daily living following a structured questionnaire. Then, the neurologists specialized in dementia diagnosis and care reviewed all the recorded information to make a preliminary judgment of dementia for participants who were suspected to have dementia. Finally, neurologists conducted the second face‐to‐face interview with people who were selected in Step 2 or with informants or both, and the diagnosis of dementia was made based on all the assessments. Dementia was further categorized into AD and VaD. AD was clinically diagnosed following the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association (NIA‐AA) criteria for probable AD dementia. 30 VaD was diagnosed following the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Association International pour la Recherche et I'Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS‐AIREN) criteria for probable VaD. 31

2.4. Measurements of plasma AD‐related biomarkers and serum cytokines

After overnight fasting, peripheral blood samples were collected into tubes coated with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) or into tubes containing EDTA‐K2 and a procoagulant separating gel, and then centrifuged following the standard procedure. Then, plasma and serum samples were collected respectively, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Plasma concentrations of Aβ40, Aβ42, total tau, and neurofilament light chain protein (NfL) were measured using a single‐molecule array (SIMOA) on the HD‐X platform (Quanterix Corp, MA) following the manufacturer's instructions (Wayen Biotechnologies Inc., Shanghai, China). The Human Neurology 3‐Plex A assay (N3PA) was used to measure Aβ40, Aβ42, and total tau, and NF‐light® advantage Kit for NfL. Two quality control (QC) samples and one pooled sample were detected in duplicates on each plate for all analyses. The intra‐ and interassay coefficients of variation for both QC samples were controlled within 13%.

Serum cytokines were measured using the Meso Scale Discovery V‐PLEX Proinflammatory Panel. 32 We included three inflammatory biomarkers in this analysis, that is, IL‐6, IL‐8, and TNF‐α. Two QC samples to monitor the intra‐ and interplate coefficients of variation. The intra‐ and interassay coefficients of variation for both QC samples were below 15%.

2.5. Measurement of covariates

The baseline assessment protocol in MIND‐China has been described in detail previously. 20 Briefly, trained clinicians and interviewers collected information on demographics, lifestyles, medical history, use of medications, and cognitive function through face‐to‐face interview, clinical examination, and laboratory tests. 33 Educational level was categorized into illiterate (no formal schooling), primary school, middle school, or above. Occupation was categorized into farmers versus nonfarmers. Smoking status and alcohol intake were categorized as ever smoking versus never smoking and current alcohol drinking versus nonalcohol drinking, respectively. Physical inactivity was defined as less than once a week of any form of physical exercise. Hypertension was defined as systolic pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic pressure ≥90 mmHg or current use of antihypertensive medication. 33 Hyperlipidemia was defined as total serum cholesterol ≥6.22 mmol/L, triglyceride ≥2.26 mmol/L, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥4.14 mmol/L, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol < 1.04 mmol/L, or current use of lipid‐lowering agents. 34 Severe depression was defined as the Geriatric Depression Scale‐15 (GDS‐15) score ≥12. 35 In addition, fasting peripheral blood samples were collected for laboratory tests, including routine biochemical examination (e.g., fasting blood glucose and lipids) and APOE genotyping.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the study participants were presented with frequencies (%) for categorical variables and median (interquartile range, IQR) for continuous variables with skewed distribution. We compared characteristics of the study participants by dementia status using the chi‐squared test for categorical variables, and Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables with skewed distribution. We analyzed CMDs both as a continuous variable (number of CMDs, range 0‐3 or 0‐4) and a categorical variable (CMM, yes vs. no). We used logistic regression models to analyze the associations of CMDs and CMM with dementia, AD, and VaD.

In the biomarker subsamples, we used the general linear regression models to examine the associations of CMDs and CMM with plasma AD‐related biomarkers and serum cytokines. Plasma NfL and Aβ40 concentrations and serum IL‐6, IL‐8, and TNF‐α levels were log‐transformed to reduce skewness. Figure S1 shows the density plots of plasma AD‐related biomarkers, serum cytokines, and log‐transformed variables (Supplemental Materials Figure S1). The three log‐transformed cytokines were converted to a standard z score, 32 and then z‐scores of the three serum cytokines were averaged to yield a composite score for low‐grade inflammation, as previously reported. 36 We reported the main results from the models that were adjusted for socio‐demographics (age, sex, education, and occupation), lifestyle behaviors (smoking, alcohol intake, physical inactivity), health conditions (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and severe depression), and APOE ε4 allele, but hyperlipidemia was not adjusted for when the independent (exposure) variable was CMM‐II or visceral obesity. To explore whether peripheral biomarkers could mediate the cross‐sectional association of CMM with cognitive outcomes, mediation models were fitted using the methods proposed by Baron and Kenny. 37 We estimated indirect effect, and the significance of the mediation was determined using 5000 bootstrapped iterations (“BruceR” package in R 4.4.1 software). The mediation models were controlled for age, sex, education, occupation, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical inactivity, hypertension, severe depression, and APOE ε4 allele.

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.4.1 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R‐project.org) for Windows and Stata Statistical Software, Release 17 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). A two‐tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of study participants

Of the 5704 participants, the median age was 70 (IQR = 7) years, 57.3% were female, and 40.5% were illiterate (Table 1). In total, 302 (5.3%) were diagnosed with all‐cause dementia, including 193 (3.4%) with AD, 98 (1.7%) with VaD, and 11 (0.2%) with other types of dementia. The overall prevalence of CMM‐I and CMM‐II in the total sample was 10.4% and 19.4%, respectively. Compared with dementia‐free participants, those with dementia were older, more likely to be female, less educated, more likely to be farmer, and less likely to smoke and drink alcohol (p < 0.001). Furthermore, compared to people without dementia, those with dementia were more likely to have hyperlipidemia, severe depression, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and visceral obesity (p < 0.05), and a higher prevalence of CMM (p < 0.001). Participants with and without dementia had no significant differences in the distributions of physical inactivity, hypertension, and APOE ε4 allele (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study participants in the total sample and by dementia status.

| Total sample | All‐cause dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics a | (n = 5704) | No (n = 5402) | Yes (n = 302) | p‐value |

| Age (y), median (IQR) | 70.0 (7.0) | 70.0 (7.0) | 76.0 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 3268 (57.3) | 3059 (56.6) | 209 (69.2) | <0.001 |

| Educational level, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Illiterate | 2308 (40.5) | 2104 (38.9) | 204 (67.5) | |

| Primary school | 2398 (42.0) | 2321 (43.0) | 77 (25.5) | |

| Middle school or above | 998 (17.5) | 977 (18.1) | 21 (7.0) | |

| Farmers, n (%) | 4920 (88.3) | 4663 (87.9) | 257 (94.8) | <0.001 |

| Ever smoking, n (%) | 2028 (35.6) | 1957 (36.2) | 71 (23.6) | <0.001 |

| Current alcohol drinking, n (%) | 1650 (28.9) | 1614 (29.9) | 36 (12.0) | <0.001 |

| Physical inactivity, n (%) | 1949 (35.1) | 1853 (35.0) | 96 (37.2) | 0.519 |

| APOE ε4 carriers, n (%) | 876 (15.9) | 826 (15.8) | 50 (17.9) | 0.414 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 3807 (67.3) | 3604 (67.2) | 203 (67.9) | 0.864 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 1387 (24.3) | 1298 (24.0) | 89 (29.5) | 0.038 |

| Severe depression, n (%) | 51 (1.0) | 39 (0.8) | 12 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 1343 (23.5) | 1254 (23.2) | 89 (29.5) | 0.015 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 899 (15.8) | 794 (14.7) | 105 (34.8) | <0.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 820 (14.4) | 763 (14.1) | 57 (18.9) | 0.027 |

| Visceral obesity, n (%) | 1471 (25.8) | 1374 (25.4) | 97 (32.1) | 0.012 |

| CMM‐I b | ||||

| No. of CMDs, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 3308 (58.0) | 3186 (59.0) | 122 (40.4) | |

| 1 | 1802 (31.6) | 1683 (31.2) | 119 (39.4) | |

| 2 | 522 (9.2) | 471 (8.7) | 51 (16.9) | |

| 3 | 72 (1.3) | 62 (1.1) | 10 (3.3) | |

| Presence of CMM, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 5110 (89.6) | 4869 (90.1) | 241 (79.8) | |

| Yes | 594 (10.4) | 533 (9.9) | 61 (20.2) | |

| CMM‐II c | ||||

| No. of CMDs, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 2581 (45.2) | 2488 (46.1) | 93 (30.8) | |

| 1 | 2019 (35.4) | 1915 (35.4) | 104 (34.4) | |

| 2 | 836 (14.7) | 761 (14.1) | 75 (24.8) | |

| 3 | 230 (4.0) | 204 (3.8) | 26 (8.6) | |

| 4 | 38 (0.7) | 34 (0.6) | 4 (1.3) | |

| Presence of CMM, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 4600 (80.6) | 4403 (81.5) | 197 (65.2) | |

| Yes | 1104 (19.4) | 999 (18.5) | 105 (34.8) | |

| Plasma AD‐related biomarkers (n = 1439) | n = 1439 | n = 1299 | n = 140 | |

| NfL (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 12.5 (7.7) | 12.0 (6.8) | 18.7 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| Aβ42 (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 11.9 (3.7) | 11.8 (3.7) | 12.6 (4.3) | 0.020 |

| Aβ40 (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 169.0 (56.2) | 168.0 (54.4) | 188.0 (66) | <0.001 |

| Total tau (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio (×1000), median (IQR) | 69.8 (19.5) | 70.3 (19.5) | 65.4 (18.2) | 0.011 |

| Serum cytokines (n = 1804) | n = 1809 | n = 1623 | n = 186 | |

| IL‐6 (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.7) | 0.9 (0.7) | 1.0 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| IL‐8 (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 18.1 (21.1) | 18.1 (21.1) | 18.6 (21.4) | 0.836 |

| TNF‐α (pg/mL), median (IQR) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.9) | <0.001 |

Notes: Data are median (IQR) or n (%).

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid‐β; AD, Alzheimer's disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CMDs, cardiometabolic diseases; CMM, cardiometabolic multimorbidity; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; IL‐8, interleukin‐8; IQR, interquartile range; NfL, neurofilament light chain; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor‐α.

The number of participants with missing values was 130 for occupation, two for smoking, one for alcohol drinking, 158 for physical inactivity, 208 for APOE ε4 allele, 45 for hypertension, and 461 for severe depression. As a covariate in subsequent analyses, a dummy variable was created for each of the categorical variables to represent those with missing values.

CMM‐I was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following three cardiometabolic diseases: type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

CMM‐II was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following four cardiometabolic diseases: visceral obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

3.2. Associations of CMDs and CMM with all‐cause dementia, AD, and VaD (n = 5704)

Of the four individual CMDs, type 2 diabetes, stroke, and visceral obesity were significantly associated with an increased likelihood of all‐cause dementia and VaD (p < 0.05), but not AD (p > 0.05) (Supplemental Materials Table S3). Heart disease was not significantly associated with all‐cause dementia and subtypes of dementia (p > 0.05).

For the CMM‐I that was defined according to three CMDs (i.e., type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke), controlling for potential confounding factors, the number of CMDs was significantly associated with increased likelihood of all‐cause dementia (odds ratio [OR] = 1.73; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.47‐2.03) and VaD (3.11; 2.42‐4.00), but not AD. As a dichotomous variable, the presence of CMM was significantly associated with increased likelihood of all‐cause dementia (OR = 2.44; 95% CI 1.75‐3.41) and VaD (5.51; 3.45‐8.79), but not AD (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Associations of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with all‐cause dementia, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular dementia (n = 5704).

| All‐cause dementia | Alzheimer's disease | Vascular dementia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic multimorbidity | No. of subjects | n | Odds ratio (95% CI) a | n | Odds ratio (95% CI) a | n | Odds ratio (95% CI) a |

| CMM‐I b | |||||||

| No. of CMDs (range 0‐3) | 5704 | 302 | 1.73 (1.47, 2.03) ** | 193 | 1.22 (0.99, 1.51) | 98 | 3.11 (2.42, 4.00) ** |

| Presence of CMM | |||||||

| No | 5110 | 241 | 1.00 (reference) | 171 | 1.00 (reference) | 61 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 594 | 61 | 2.44 (1.75, 3.41) ** | 22 | 1.27 (0.78, 2.06) | 37 | 5.51 (3.45, 8.79) ** |

| CMM‐II c | |||||||

| No. of CMDs (range 0‐4) | 5704 | 302 | 1.57 (1.37, 1.79) ** | 193 | 1.20 (1.01, 1.42) * | 98 | 2.54 (2.07, 3.12) ** |

| Presence of CMM | |||||||

| No | 4600 | 197 | 1.00 (reference) | 144 | 1.00 (reference) | 45 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Yes | 1104 | 105 | 2.53 (1.91, 3.36) ** | 49 | 1.53 (1.06, 2.20) * | 53 | 6.12 (3.90, 9.61) ** |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMDs, cardiometabolic diseases; CMM, cardiometabolic multimorbidity.

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) was adjusted for age, sex, education, occupation, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical inactivity, hypertension, severe depression, and APOE ε4 allele when the CMM‐II was the independent variable, and additionally adjusted for hyperlipidemia when CMM‐I was the independent variable.

CMM‐I was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following three cardiometabolic diseases: type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

CMM‐II was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following four cardiometabolic diseases: visceral obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

For the CMM‐II that was defined based on four CMDs (i.e., visceral obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke), both the number of CMDs and the presence of CMM were significantly associated with increased likelihood of all‐cause dementia, AD, and VaD (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

The aforementioned associations of the number of CMDs and the presence of CMM with AD, dementia, and VaD could be roughly replicated in the subsamples of plasma AD‐related biomarkers and serum inflammatory biomarkers (Supplemental Materials Table S4 and Table S5).

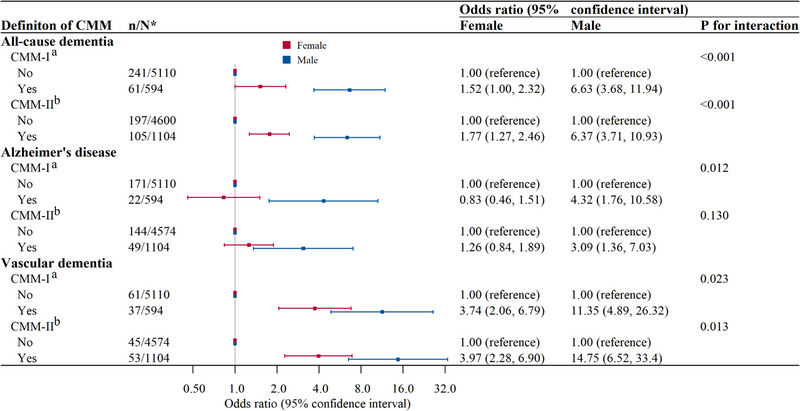

In the total sample, we detected a statistically significant or marginal interaction of sex with CMM‐I and CMM‐II on all‐cause dementia (p for interaction < 0.001), AD (p for interaction = 0.012 and 0.130, respectively), and VaD (p for interaction = 0.023 and 0.013, respectively). Further analysis stratified by sex showed that the associations of CMM with all‐cause dementia, AD, and VaD were stronger in males than in females (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of the associations of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with all‐cause dementia and subtypes of dementia by sex (n = 5704). *n/N indicates the number of cases (all‐cause dementia or subtypes of dementia)/the number of participants. aCMM‐I was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following three cardiometabolic diseases: type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. bCMM‐II was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following four cardiometabolic diseases: visceral obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) was adjusted for age, education, occupation, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical inactivity, hypertension, severe depression, and APOE ε4 allele when the CMM‐II was the independent variable, and additionally adjusted for hyperlipidemia when CMM‐I was the independent variable. APOE, apolipoprotein E; CMM, cardiometabolic multimorbidity.

3.3. Associations of CMM with plasma AD biomarkers and serum cytokines

In the plasma AD‐related biomarker subsample (n = 1439), controlling for potential confounders, the presence of CMM‐I was significantly associated with increased plasma NfL (β‐coefficient = 0.096; 95% CI 0.005‐0.186), Aβ40 (0.062; 0.018‐0.107), and Aβ42 (0.560; 0.020‐1.100) (p < 0.05), but not with plasma total tau and Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio (p > 0.05) (Table 3). We also analyzed CMM‐II in association with plasma AD biomarkers, which yielded results similar to those for the CMM‐I (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Associations between cardiometabolic multimorbidity and plasma Alzheimer's biomarkers (n = 1439).

| β coefficient (95% confidence interval) a , plasma Alzheimer's biomarkers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic multimorbidity | NfL (pg/mL), log‐transformed | Aβ40 (pg/mL), log‐transformed | Aβ42 (pg/mL) | Total tau (pg/mL) | Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, ×1000 |

| CMM‐I b | |||||

| No. of CMDs (range 0‐3) | 0.064 (0.026, 0.102) *** | 0.029 (0.010, 0.048) ** | 0.339 (0.110, 0.568) ** | −0.009 (−0.084, 0.066) | −0.082 (−1.316, 1.153) |

| Presence of CMM | 0.096 (0.005, 0.186) * | 0.062 (0.018, 0.107) * | 0.560 (0.020, 1.100) * | −0.018 (−0.194, 0.159) | −0.602 (−3.511, 2.308) |

| CMM‐II c | |||||

| No. of CMDs (range 0‐4) | 0.052 (0.020, 0.084) ** | 0.035 (0.020, 0.051) *** | 0.424 (0.235, 0.613) *** | 0.013 (−0.049, 0.075) | −0.004 (−1.029, 1.020) |

| Presence of CMM | 0.119 (0.051, 0.187) *** | 0.077 (0.043, 0.110) *** | 0.895 (0.491, 1.299) *** | 0.065 (−0.068, 0.197) | −0.060 (−2.248, 2.128) |

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid β protein; CMDs, cardiometabolic diseases; CMM, cardiometabolic multimorbidity; NfL, neurofilament light chain.

β coefficient (95% confidence interval) was adjusted for age, sex, education, occupation, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical inactivity, hypertension, severe depression, and APOE ε4 allele when the CMM‐II was the independent variable, and additionally adjusted for hyperlipidemia when CMM‐I was the independent variable.

CMM‐I was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following three cardiometabolic diseases: type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Of the 1439 participants, 132 (9.2%) were defined with CMM‐I.

CMM‐II was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following four cardiometabolic diseases: visceral obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Of the 1439 participants, 277 (19.2%) were defined with CMM‐II.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

In the serum cytokines subsample (n = 1809), when CMM was defined based on three CMDs (CMM‐I), neither the number of CMDs nor the presence of CMM‐I was significantly associated with any of the three examined serum cytokines and the composite score for low‐grade inflammation. By contrast, for CMM‐II, controlling for potential confounders, having CMM‐II was significantly associated with higher levels of serum IL‐6 (β‐coefficient = 0.203; 95% CI 0.084‐0.323), TNF‐α (0.318; 0.198‐0.437), and the composite score of low‐grade inflammation (0.170; 0.077‐0.263) (p < 0.001), but not with serum IL‐8 (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Associations of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with serum cytokines and low‐grade inflammation (n = 1809).

| β coefficient (95% confidence interval), serum cytokines a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic multimorbidity | IL‐6 (pg/mL) b | IL‐8 (pg/mL) b | TNF‐α (pg/mL) b | Low‐grade inflammation, composite score |

| CMM‐I c | ||||

| No. of CMDs (range 0‐3) | 0.033 (−0.033, 0.100) | −0.044 (−0.110, 0.023) | 0.051 (−0.016, 0.117) | 0.013 (−0.039, 0.065) |

| Presence of CMM | 0.057 (−0.098, 0.211) | −0.079 (−0.235, 0.076) | 0.108 (−0.047, 0.263) | 0.029 (−0.092, 0.149) |

| CMM‐II d | ||||

| No. of CMDs (range 0‐4) | 0.084 (0.029, 0.138) * | −0.008 (−0.063, 0.048) | 0.140 (0.086, 0.195) ** | 0.072 (0.029, 0.115) * |

| Presence of CMM | 0.203 (0.084, 0.323) ** | −0.010 (−0.130, 0.110) | 0.318 (0.198, 0.437) ** | 0.170 (0.077, 0.263) ** |

Abbreviations: CMDs, cardiometabolic diseases; CMM, cardiometabolic multimorbidity; IL‐6, interleukin‐6; IL‐8, interleukin‐8; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor‐α.

β coefficient (95% confidence interval) was adjusted for age, sex, education, occupation, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical inactivity, hypertension, severe depression, and APOE ε4 allele when the CMM‐II was the independent variable, and additionally adjusted for hyperlipidemia when CMM‐I was the independent variable.

Serum IL‐6, IL‐8, and TNF‐α were log‐transformed to reduce skewness, and then converted to standard z‐scores. The composite score for low‐grade inflammation was generated by averaging z‐scores of the three individual cytokines.

CMM‐I was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following three cardiometabolic diseases: type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Of the 1809 participants, 182 (10.1%) were defined with CMM‐I.

CMM‐II was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following four cardiometabolic diseases: visceral obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Of the 1809 participants, 351 (19.4%) were defined with CMM‐II.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

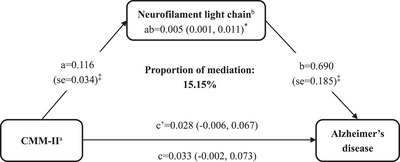

3.4. Mediation of peripheral biomarkers in the association of CMM with dementia, AD, and VaD

In the plasma AD‐related biomarker subsample (n = 1439), the mediation analysis showed that plasma NfL significantly mediated the association between CMM‐II and the likelihood of AD, with the proportion of mediation being 15.15% (p < 0.05) (Figure 3). Further mediation analysis by sex showed that the mediation of plasma NfL in the association of CMM‐II with AD was significant in both female and male participants, with the proportion of mediation being 16.7% and 16.4%, respectively. There was no significant mediation of plasma NfL in the association between CMM‐I and the likelihood of AD. In the serum cytokine subsample (n = 1809), no statistically significant mediation of serum cytokines in the association of CMM with dementia or subtypes of dementia was observed.

FIGURE 3.

Mediation effect of plasma NfL in the association of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with Alzheimer's disease. aCMM‐II was defined as the concurrent presence of two or more of the following four cardiometabolic diseases: type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and visceral obesity. bPlasma NfL was log‐transformed due to skewed distribution of original data. The β coefficients (95% confidence intervals) in all paths were adjusted for age, sex, education, occupation, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical inactivity, hypertension, severe depression, and APOE ε4 allele. AD, Alzheimer's disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CMM, cardiometabolic multimorbidity; NfL, neurofilament light chain. * p < 0.05, ‡ p < 0.001.

4. DISCUSSION

The main findings from this large‐scale population‐based study of rural‐dwelling older adults in China can be summarized as follows: (1) CMM, operationalized in two ways, was strongly associated with increased likelihoods of all‐cause dementia, especially VaD; (2) CMM‐I and ‐II were associated with increased plasma Aβ40, Aβ42, and NfL, whereas CMM‐II but not CMM‐I was associated with increased serum inflammatory cytokines, and (3) plasma NfL could partly mediate the cross‐sectional association of CMM‐II with AD.

Previously, epidemiological studies have frequently linked individual cardiovascular disorders (e.g., ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure) with cognitive decline and dementia. 38 , 39 Studies from the UK Biobank cohort 11 , 13 and the Swedish SNAC‐K cohort 12 have reported the association between CMM and an increased risk of dementia. Different CMDs were included when defining CMM in the previous studies. 12 , 16 , 23 , 40 Thus, we defined CMM by employing two definitions that were used in previously well‐designed studies. 12 , 41 We were able to assess whether CMM defined by different definitions were differentially associated with dementias and peripheral biomarkers. We found that CMM, defined by both definitions, was associated with increased likelihoods of all‐cause dementia, and VaD in particular. Of note, CMM was also evidently associated with an increased likelihood of AD only when visceral obesity was included in defining CMM (CMM‐II), indicating importance of visceral obesity in the association of CMM with AD. 42 In addition, we detected potential interactions of CMM with sex on all‐cause dementia and subtypes of dementia such that the associations of CMM with all‐cause dementia, AD, and VaD were stronger in men than in women. In line with this finding, previous studies have reported stronger associations of CMM pattern with reduced volumes of total brain tissue and gray matter in men than in women, 43 which might partially account for the sex‐specific differences in the association of CMM with dementia and subtypes of dementia.

While cumulative evidence supports the association of CMM with dementia, the underlying neuropathological mechanisms are not fully understood. A large‐scale case‐control study suggested that AD was associated with a reduced plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and elevated plasma NfL. 44 We observed that CMM was associated with increased plasma Aβ40, Aβ42, and NfL. Because plasma Aβ is predominantly affected by blood‐brain barrier (BBB) permeability in AD‐related brain regions, 45 the association of CMM with increased plasma Aβ could be attributed to CMM‐related vascular injury, leading to increased BBB permeability and more leakage of Aβ into blood. Plasma NfL is a biomarker of nonspecific neurodegeneration and neuroaxonal injury. Higher serum NfL concentration has been associated with covert MRI findings of vascular brain injury (e.g., burden of white matter hyperintensities), 46 which is in line with our finding that CMM was associated with higher NfL. Moreover, we found that plasma NfL, rather than Aβ40 or Aβ42, could partly mediate the cross‐sectional association of CMM with AD. These results were in line with the report from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging that cardiometabolic disorders and multimorbidity were cross‐sectionally associated with decreased cortical thickness in AD signature regions but not with amyloid accumulation in the brain, 47 and the report from the UK Biobank Study that CMM was associated with severe cerebral atrophy. 13 Taken together, these studies support the view that neurodegeneration may play a crucial role in linking CMM with AD in older adults.

It has been well established that chronic low‐grade systemic inflammation (e.g., elevated serum IL‐6 and TNF‐α) is involved in atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. 48 Thus, it can be expected that CMM is associated with increased serum cytokines (e.g., IL‐6 and TNF‐α). However, the strong association of CMM with serum cytokines was observed only when visceral obesity was one of the four CMDs in defining CMM (i.e., CMM‐II), but not with CMM‐I where visceral obesity was not included. Previous studies have shown that adipocytes can synthesize proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF‐α, IL‐6, and IL‐1β), 49 and that visceral adiposity is more proinflammatory than subcutaneous abdominal adiposity. 50 In addition, studies have suggested that chronic inflammation is a crucial event in the process of cognitive aging. 51 , 52 The Swedish SNAC‐K study showed that inflammation could confer further risk of dementia associated with multimorbidity burden. 53 We additionally explored the potential role of inflammatory pathways in the association of CMM and cognitive phenotypes. When controlling for multiple potential confounders, we did not find evidence for the important mediation effect of inflammation in the cross‐sectional association of CMM with dementia or subtypes of dementia.

This population‐based study engaged older residents from a rural area in China who had low socioeconomic status and who received no or very limited formal education, and this sociodemographic group has been substantially underrepresented in dementia research. 15 In addition, we were able to explore the potential mechanisms linking CMM with dementia by integrating epidemiological and clinical data with blood biomarker data in subsamples. However, our study also has limitations. First, the cross‐sectional design cannot determine a causal relationship and the observed cross‐sectional associations are subject to selective survival bias and might represent a misestimation of the true associations because individuals with CMDs or CMM, especially when concurrently occurring with dementia disorders, are less likely to be included in the study owing to poor survival associated with these health conditions. Furthermore, the cross‐sectional design of the study should also be taken into account when interpreting the results from mediation analyses because they do not capture the temporal sequences of the exposures, mediators, and outcomes. Second, we were not able to explore the role of tau pathology due to lack of relevant plasma biomarkers (e.g., p‐tau181 and p‐tau217). 54 Finally, this study recruited participants from only one rural area in northern China, which should be kept in mind when generalizing the research findings to other rural populations.

In conclusion, this population‐based cross‐sectional study showed that CMM was associated with increased likelihood of all‐cause dementia and AD, and VaD in particular, among rural‐dwelling older adults. Our study further revealed that neurodegenerative pathway played a part in the cross‐sectional association of CMM with AD. These results increase our understanding of the association of CMM with dementia, AD, and VaD in older adults and the potential underlying neuropathological mechanisms. Future prospective cohort studies may provide additional insights in the temporal association of CMM with subsequent cognitive phenotypes, as well as the underlying mechanisms. This is highly relevant for the development of preventive and therapeutic interventions to promote cognitive health in aging and delay the onset of dementia.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

M. Kivipelto has served on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Combinostics, Eisai, Eli Lilly, and Nestle. Other authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest. Author disclosures are available in the Supporting information.

CONSENT STATEMENT

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, or in the case of dementias persons, from an informant (usually a guardian or a family member).

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ICMJE Disclosure Form

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely express our gratitude to all participants of the MIND‐China study for their invaluable contributions and to our colleagues at the Yanlou Town Hospital and the Department of Neurology in Shandong Provincial Hospital for their support and collaboration in data collection and management. This work was supported in part by grants from the STI2030‐Major Projects (grant no.: 2021ZD0201801, and 2021ZD0201808), the National Key R&D Program of China Ministry of Sciences and Technology (grant no.: 2017YFC1310100 and 2022YFC3501404), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.: 81861138008, 82011530139, 82171175, and 82200980), the Academic Promotion Program of Shandong First Medical University (grant no.: 2019QL020), the Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Program in Shandong Province (grant no.: YXH2019ZXY008), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant no.: ZR2021MH392 and ZR2021QH240), the Postdoctoral Innovation Project of Shandong Province, the Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Program (grant no.: 2021LCZX03), the Clinical Medicine Technology Innovation Program (grant no.: 202019080), and the Taishan Scholar Program of Shandong Province, China. DL Vetrano received the grant from the Swedish Research Council. T Ngandu received the grants from the EU Joint Programme–Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND), Nordforsk, the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, the Alzheimer's Research and Prevention Foundation, the Finnish Cultural Foundation, the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF) (sub‐award), European Union Horizon 2020, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation. M Kivipelto received the program grant from the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (grant no.: 2023‐01125) and grants from the Stiftelse Stockholms Sjukhem, the Center for Innovative Medicine (CIMED) at Karolinska Institutet, and the Alzheimer's Foundation (ALF). C Qiu received grants from the Swedish Research Council (grant no.: 2017‐05819 and 2020‐01574), and the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (grant no.: CH2019‐8320). The World‐Wide FINGERS Network and the FINGERS Brain Health Institute are supported by the Alzheimer's Disease Data Initiative. The funding agencies had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, the writing of this article, and in the decision to submit the work for publication.

Liu C, Liu R, Tian N, et al. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity, peripheral biomarkers, and dementia in rural older adults: The MIND‐China study. Alzheimer's Dement. 2024;20:6133–6145. 10.1002/alz.14091

Contributor Information

Tingting Hou, Email: houtingting@sdfmu.edu.cn.

Yifeng Du, Email: du-yifeng@hotmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Collaborators GBDDF . Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(2):e105‐e125. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jia L, Du Y, Chu L, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults aged 60 years or older in China: a cross‐sectional study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(12):e661‐e671. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30185-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan KY, Wang W, Wu JJ, et al. Epidemiology of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia in China, 1990‐2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):2016‐2023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60221-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wolters FJ, Segufa RA, Darweesh SKL, et al. Coronary heart disease, heart failure, and the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(11):1493‐1504. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuzma E, Lourida I, Moore SF, Levine DA, Ukoumunne OC, Llewellyn DJ. Stroke and dementia risk: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(11):1416‐1426. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Selman A, Burns S, Reddy AP, Culberson J, Reddy PH. The role of obesity and diabetes in dementia. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(16):9267. doi: 10.3390/ijms23169267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM. Designing health care for the most common chronic condition–multimorbidity. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2493‐2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canoy D, Tran J, Zottoli M, et al. Association between cardiometabolic disease multimorbidity and all‐cause mortality in 2 million women and men registered in UK general practices. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):258. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02126-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Otieno P, Asiki G, Aheto JMK, et al. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity associated with moderate and severe disabilities: results from the study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE) wave 2 in Ghana and South Africa. Glob Heart. 2023;18(1):9. doi: 10.5334/gh.1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang ZT, Luo Y, Han L, et al. Patterns of cardiometabolic multimorbidity and the risk of depressive symptoms in a longitudinal cohort of middle‐aged and older Chinese. J Affect Disord. 2022;301:1‐7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lyall DM, Celis‐Morales CA, Anderson J, et al. Associations between single and multiple cardiometabolic diseases and cognitive abilities in 474 129 UK Biobank participants. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(8):577‐583. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dove A, Marseglia A, Shang Y, et al. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity accelerates cognitive decline and dementia progression. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(3):821‐830. doi: 10.1002/alz.12708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tai XY, Veldsman M, Lyall DM, et al. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity, genetic risk, and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022;3(6):e428‐e436. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00117-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jin Y, Liang J, Hong C, Liang R, Luo Y. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity, lifestyle behaviours, and cognitive function: a multicohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023;4(6):e265‐e273. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00054-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wiese LAK, Gibson A, Guest MA, et al. Global rural health disparities in Alzheimer's disease and related dementias: state of the science. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(9):4204‐4225. doi: 10.1002/alz.13104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao Y, Zhang H, Liu X, et al. The prevalence of cardiometabolic multimorbidity and its associations with health outcomes among women in China. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:922932. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.922932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bhat NR. Linking cardiometabolic disorders to sporadic Alzheimer's disease: a perspective on potential mechanisms and mediators. J Neurochem. 2010;115(3):551‐562. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06978.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Femminella GD, Taylor‐Davies G, Scott J, Edison P. Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging I. Do cardiometabolic risk factors influence amyloid, tau, and neuronal function in APOE4 carriers and non‐carriers in Alzheimer's disease trajectory? J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64(3):981‐993. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ren Y, Li Y, Tian N, et al. Multimorbidity, cognitive phenotypes, and Alzheimer's disease plasma biomarkers in older adults: a population‐based study. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;20(3):1550‐1561. doi: 10.1002/alz.13519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Y, Han X, Zhang X, et al. Health status and risk profiles for brain aging of rural‐dwelling older adults: data from the interdisciplinary baseline assessments in MIND‐China. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2022;8(1):e12254. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dong Y, Hou T, Li Y, et al. Plasma amyloid‐beta, total tau, and neurofilament light chain across the Alzheimer's disease clinical spectrum: a population‐based study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;96(2):845‐858. doi: 10.3233/JAD-230932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Piche ME, Tchernof A, Despres JP. Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2020;126(11):1477‐1500. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emerging Risk Factors C, Di Angelantonio E, Kaptoge S, et al. Association of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with mortality. JAMA. 2015;314(1):52‐60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cong L, Ren Y, Hou T, et al. Use of cardiovascular drugs for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease among rural‐dwelling older Chinese adults. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:608136. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.608136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Amato MC, Giordano C, Galia M, et al. Visceral adiposity index: a reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(4):920‐922. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Neeland IJ, Ross R, Despres JP, et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(9):715‐725. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30084-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Valenzuela PL, Carrera‐Bastos P, Castillo‐Garcia A, Lieberman DE, Santos‐Lozano A, Lucia A. Obesity and the risk of cardiometabolic diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20(7):475‐494. doi: 10.1038/s41569-023-00847-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Amato MC, Giordano C, Pitrone M, Galluzzo A. Cut‐off points of the visceral adiposity index (VAI) identifying a visceral adipose dysfunction associated with cardiometabolic risk in a Caucasian Sicilian population. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:183. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Association. AP . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth ed. (DSM‐IV). American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263‐269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS‐AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43(2):250‐260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y, Li Y, Liu K, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, serum cytokines, and dementia among rural‐dwelling older adults in China: a population‐based study. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29(9):2612‐2621. doi: 10.1111/ene.15416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Han X, Jiang Z, Li Y, et al. Sex disparities in cardiovascular health metrics among rural‐dwelling older adults in China: a population‐based study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):158. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02116-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Song P, Zha M, Yang X, et al. Socioeconomic and geographic variations in the prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of dyslipidemia in middle‐aged and older Chinese. Atherosclerosis. 2019;282:57‐66. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Asokan GV, Awadhalla M, Albalushi A, et al. The magnitude and correlates of geriatric depression using Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS‐15)—a Bahrain perspective for the WHO 2017 campaign ‘Depression—let's talk’. Perspect Public Health. 2019;139(2):79‐87. doi: 10.1177/1757913918787844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Janssen E, Köhler S, Geraets AFJ, et al. Low‐grade inflammation and endothelial dysfunction predict four‐year risk and course of depressive symptoms: the Maastricht study. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;97:61‐67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator‐mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173‐1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qiu C, Fratiglioni L. A major role for cardiovascular burden in age‐related cognitive decline. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(5):267‐277. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Imahori Y, Vetrano DL, Ljungman P, et al. Association of ischemic heart disease with long‐term risk of cognitive decline and dementia: a cohort study. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(12):5541‐5549. doi: 10.1002/alz.13114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. He L, Ma T, Cheng X, Bai Y. The association between sleep characteristics and the risk of all‐cause mortality among individuals with cardiometabolic multimorbidity: a prospective study of UK Biobank. J Clin Sleep Med. 2023;19(4):651‐658. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.10404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation. 2016;133(2):187‐225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang S, Zhang Q, Hou T, et al. Differential associations of 6 adiposity indices with dementia in older adults: the MIND‐China study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2023;24(9):1412‐1419.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2023.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shang X, Zhang X, Huang Y, et al. Association of a wide range of individual chronic diseases and their multimorbidity with brain volumes in the UK Biobank: a cross‐sectional study. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;47:101413. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stevenson‐Hoare J, Heslegrave A, Leonenko G, et al. Plasma biomarkers and genetics in the diagnosis and prediction of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2023;146(2):690‐699. doi: 10.1093/brain/awac128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bellaver B, Puig‐Pijoan A, Ferrari‐Souza JP, et al. Blood‐brain barrier integrity impacts the use of plasma amyloid‐beta as a proxy of brain amyloid‐beta pathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(9):3815‐3825. doi: 10.1002/alz.13014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fohner AE, Bartz TM, Tracy RP, et al. Association of serum neurofilament light chain concentration and MRI findings in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Neurology. 2022;98(9):e903‐e911. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000013229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vassilaki M, Aakre JA, Mielke MM, et al. Multimorbidity and neuroimaging biomarkers among cognitively normal persons. Neurology. 2016;86(22):2077‐2084. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liberale L, Montecucco F, Tardif JC, Libby P, Camici GG. Inflamm‐ageing: the role of inflammation in age‐dependent cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(31):2974‐2982. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Coppack SW. Pro‐inflammatory cytokines and adipose tissue. Proc Nutr Soc. 2001;60(3):349‐356. doi: 10.1079/pns2001110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fox CS, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116(1):39‐48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xie J, Van Hoecke L, Vandenbroucke RE. The impact of systemic inflammation on Alzheimer's disease pathology. Front Immunol. 2021;12:796867. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.796867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Uyar B, Palmer D, Kowald A, et al. Single‐cell analyses of aging, inflammation and senescence. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;64:101156. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Grande G, Marengoni A, Vetrano DL, et al. Multimorbidity burden and dementia risk in older adults: the role of inflammation and genetics. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(5):768‐776. doi: 10.1002/alz.12237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brickman AM, Manly JJ, Honig LS, et al. Plasma p‐tau181, p‐tau217, and other blood‐based Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in a multi‐ethnic, community study. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(8):1353‐1364. doi: 10.1002/alz.12301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

ICMJE Disclosure Form