Abstract

Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is a ubiquitous, structurally complex multifunctional protein serine/threonine kinase that plays an important role in cell apoptosis via linking the ER stress and mitochondrial apoptosis pathways. Recently, CaMKII has been correlated with apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) activity and the ASK1-dependent apoptosis pathway through the direct phosphorylation of Thr845 of ASK1. The specific role of CaMKII in hypoxia–reoxygenation (H/R)-induced spinal astrocyte apoptosis, however, remains unclear. In this study, we investigated the effects of CaMKIIγ (an isoform of CaMKII) on spinal astrocyte apoptosis using an in vitro oxygen–glucose deprivation (OGD/R) model which mimics hypoxic/ischemic conditions in vivo. OGD/R increased cell death and the activation of CaMKII. Deletion of CaMKIIγ results in the reduced activation of CaMKII and apoptosis in astrocytes under OGD/R conditions. Notably, the deletion of CaMKIIγ induced ASK1 phosphorylation at Thr845 in astrocytes. The activation of JNK and p38 and the downstream effect of ASK1 were also reduced. These data suggest that CaMKIIγ is required for the CaMKII-dependent regulation of ASK1, affecting the apoptosis of a biologically important cell type under spinal cord injury.

Keywords: CaMKIIγ, Apoptosis, Astrocytes, Spinal cord injury, Rat

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) due to mechanical trauma, ischemia, or tumor invasion leads to incapacitating locomotor impairment and affects the productive age of individuals, resulting in enormous social and economic impacts. Recovery following SCI is limited due to axonal damage (Kurnellas et al. 2005), demyelination, and scar formation (McDonald and Belegu 2006).

Astrocytes are one of the first responders to SCI and remain viable longer than neurons, which are more sensitive to metabolic alterations (Zhao and Flavin 2000). Under hypoxic/ischemic conditions, astrocytes regulate blood flow (Takano et al. 2006) and secrete angiogenic, neurotrophic, and neuroprotective factors (Abbott et al. 2006). Therefore, astrocyte survival during ischemia could be crucial for preserving homeostasis and stimulating SCI recovery.

A number of factors have been implicated in astrocyte apoptosis, including the levels of Ca2+, (Ouyang et al. 2011; Kitao et al. 2010), ER stress (Benavides et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2008, 2010), free radicals (Swarnkar et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2011; Jung et al. 2010, Kim and Lee 2007), and mitochondrial dysfunction (Guo et al. 2012; Cabezas et al. 2012). Several investigators have shown that the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria are the primary targets of hypoxic/ischemic stress in astrocytes. For instance, it has been suggested that oxygen-glucose-serum deprivation leads to spinal cord astrocyte apoptosis during ER stress (Zhang et al. 2010). More recently, a study demonstrated that 17β-estradiol prevents cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction through an estrogen receptor-dependent mechanism in astrocytes following oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (Guo et al. 2012). Nevertheless, the precise intracellular mechanisms underlying Ca2+-mediated astrocyte apoptosis during ischemia-like injury have not been elucidated.

Therefore, identification of the Ca2+-initiated intracellular events that mediate the induction of apoptotic responses is of considerable interest for the development of specific techniques to target anti-apoptotic mechanisms under hypoxic or ischemic conditions. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is a ubiquitous, structurally complex multifunctional protein serine/threonine kinase with four isoforms, α, β, γ, and δ (Mayer et al. 1995). CaMKII is a well-known downstream effector of Ca2+ activity. Activated CaMKII induces apoptosis through apoptosis signaling kinase 1 (ASK1) and JNK pathway (Brnjic et al. 2010). It has been suggested that CaMKIIγ plays an important role in macrophage and endothelial cell apoptosis via linking the ER stress and mitochondrial apoptosis pathways (Timmins et al. 2009).

The aim of this study was to examine the involvement of the CaMKII signaling pathway in astrocyte apoptosis after ischemia-like injury using an in vitro oxygen–glucose deprivation (OGD) model that mimics in vivo hypoxic/ischemic conditions. We demonstrated that CaMKII mediates astrocyte apoptosis via the activation of ASK1.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Rat spinal cord astrocytes were prepared from newborn Sprague-Dawley rats, 1–2 days after birth, and isolated and cultured according to previously described methods (Zhang et al. 2010). Briefly, the cells were enzymatically dissociated using 0.25 % trypsin (Gibco-BRL) for 6 min at 37 °C, and the suspension was then centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 min and cultured in 1:1 Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium:Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.224 % NaHCO3, and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin under the presence of 5 % CO2. Third or fourth passage cells were rendered quiescent through incubation in medium containing 0.5 % FBS for 4 days prior to the experiments. Confirmation of an astrocyte phenotype was based on the cells showing a typical morphology and positive staining for the astrocytic marker glial fibrillary acid protein.

Silencing of CaMKIIγ

Astrocytes were transduced with a CaMKIIγ knockdown lentivirus or control lentivirus (non-targeting sequences) and selected using 2 mg/L puromycin. The shRNA sequences targeting CaMKIIγ were generated at Shanghai Genechem Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). The target sequence was AACGTGGTACATAATGCTACA, as previously described (Kim and Lee 2007).

Oxygen–Glucose–Serum Deprivation/Restoration

To mimic ischemia-like conditions in vitro, the cell cultures were subjected to permanent glucose deprivation and hypoxia for 8 h, followed by restoration for various times (0, 2, 4, 6, 12, or 24 h). In the oxygen and glucose deprivation phase, the medium was washed with glucose-free Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) and changed to glucose-free DMEM (Gibco-BRL), and the cultures were subsequently placed in an airtight experimental hypoxia chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, San Diego, CA, USA) containing a gas mixture composed of 95 % N2/5 % CO2. After 8 h, the cells were cultured in standard medium under normoxic conditions for reoxygenation. The control astrocytes were not exposed to OGD (Zhang et al. 2010).

DHE Staining for Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Detection

DHE is oxidized by ROS, forming ethidium bromide, which emits red fluorescence when it intercalates with DNA (Benov et al. 1998). After OGD/R treatment, rat spinal cord astrocytes were incubated with 5 mM DHE (Sigma, USA) in PBS at 37 °C for 30 min under a humid atmosphere in the dark, washed twice with PBS, mounted, and visualized using an Olympus IMT-2 inverted microscope equipped with a xenon lamp and a 12-bit digital-cooled CCD camera (Micromax, Princeton Instruments), as previously described (Petronilli et al. 1999). For fluorescence detection, 568 + 25-nm excitation and 585-nm long-pass emission filter settings were used. The data were acquired and analyzed using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging).

Western Blotting

After treatment for the indicated time periods, the cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM TRIS (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.1 % sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1 % Triton X-100, and 1 % sodium deoxycholate) for 20–30 min on ice. The obtained protein concentrations were determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo, USA). The lysates were then incubated with 2× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and heated for 10 min at 95 °C. Equal amounts (25 μg/lane) of total protein were resolved through sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), and incubated with blocking buffer (Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 (TBST)/5 % nonfat dry milk) for 2 h at room temperature. The immunoblots were subsequently incubated with the indicated primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, followed by the appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody, and visualized via enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Millipore, USA) using hydrogen peroxide and luminol as a substrate with Kodak X-AR film. The autoradiographs were scanned using a GS-700 Imaging Densitometer (Bio-Rad). The following antibodies were used anti-ASK1, anti-phospho-AKSK1, and anti-caspase-3 were obtained from cell signaling technology (USA); anti-JNK1, anti-phospho-JNK, anti-p38, anti-phospho-p38, anti-β-actin, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG were procured from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA); and anti-CaMKII and anti-phospho-CaMKII were purchased from Abcam (USA).

MTT Assay

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was performed to evaluate cell survival. The cells were cultured at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate. After treatment for the indicated time periods, the MTT solution (5.0 mg/mL in phosphate buffered saline) was added (20.0 μL/well), and the plates were incubated for an additional 4 h at 37 °C. The resultant purple formazan crystals were dissolved in 150 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) per well. After 10 min, the plates were read on an ELX800 universal microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Elx800, USA). The assays were repeated in three independent experiments.

Annexin V/Propidium Iodide Double Staining and Cell Cycle Analysis

Annexin V/propidium iodide double staining and cell cycle analysis were used to detect cell apoptosis. Astrocytes were plated in 60-mm wells (3 mL, 1 × 106/well) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After treatment for the indicated time periods, the cells were collected and washed twice with ice-cold PBS buffer. The cells were subsequently resuspended in binding buffer at 1 × 106 cells/mL and incubated with annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (BD Biosciences, USA) to achieve double staining according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The mixture was incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature before analysis. For the cell cycle analysis, the collected cells were fixed at −20 °C in ice-cold 70 % ethanol overnight. After two washes with PBS, the cells were stained with propidium iodide and subsequently analyzed in a Beckman Coulter FC500 flow cytometry system using CXP software (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Statistical Analysis

Three or more separate repetitions were performed for each experiment. Statistical analysis was performed by Student’s t test or ANOVA. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D). P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of OGD/R on ROS Production in Astrocytes

When the cells were exposed to hypoxic conditions for 8 h and subsequently restored for various times (at 0, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h), the production of ROS was found to be time dependent (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of OGD/R on reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. a Dihydroethidium (DHE) fluorescence in cultured astrocytes. Scale bar 50 μm. Lane 1 control cells without OGD; Lane 2 OGD with deprivation for 0 h; Lane 3 OGD with deprivation for 6 h; Lane 4 OGD with deprivation for 24 h. b The quantification of fluorescence intensity presented in the bar graphs represents the average results from three different experiments; *P < 0.05. Lane 1 control cells without OGD; Lane 2 OGD with deprivation for 0 h; Lane 3 OGD with deprivation for 2 h; Lane 4 OGD with deprivation for 4 h; Lane 5 OGD with deprivation for 6 h; Lane 6 OGD with deprivation for 12 h; Lane 7 OGD with deprivation for 24 h

Effect of OGD/R on Apoptosis and CaMKII Activation in Astrocytes

The cells were exposed to hypoxic conditions for 8 h and subsequently restored for various times (at 0, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h). Phospho-CaMKII, the activated form of CaMKII, was found to be expressed in a time-dependent manner. In addition, the expression of the biochemical apoptosis marker caspase-3 was also markedly increased (Fig. 2). To prove whether ROS could cause apoptosis and CaMKII activation in astrocytes under OGD/R, the cells were pretreated with an efficient oxygen radical scavenger N-acetylcysteine (NAC, 100 nM) and then subjected to OGD/R (Gabryel et al. 2011). With NAC treatment, a markedly decrease in phospho-CaMKII and caspase-3 expression was found compare to those cells treated with OGD/R alone (Fig. 3). These observations suggested that OGD/R treatment induced apoptosis and activation of CaMKII in astrocytes, and CaMKII is the downstream target of ROS.

Fig. 2.

The effect of OGD/R on the expression of phospho-CaMKII, CaMKII, caspase-3, and β-actin (loading control) in astrocytes was analyzed via Western blotting. Lane 1 control cells without OGD; Lane 2 OGD with deprivation for 0 h; Lane 3 OGD with deprivation for 2 h; Lane 4 OGD with deprivation for 4 h; Lane 5 OGD with deprivation for 6 h; Lane 6 OGD with deprivation for 12 h; Lane 7 OGD with deprivation for 24 h

Fig. 3.

After treatment of NAC or KN93, the cells were subjected to OGD, followed by deprivation for 6 h. The levels of phospho-CaMKII, CaMKII, caspase-3, and β-actin (loading control) were analyzed through Western blotting. Lane 1 control cells without OGD; Lane 2 control cells; Lane 3 cells treated with the NAC; Lane 4 cells treated with the KN93

CaMKIIγ is Essential for OGD/R-Induced CaMKII Activation

CaMKIIγ has been associated with apoptosis under oxidative and ER stress. To assess whether CaMKIIγ is required for OGD/R-induced CaMKII activation, we measured the activities of phospho-CaMKII in control and CaMKIIγ knockdown cells. The downregulation of CaMKIIγ affected OGD/R-induced phospho-CaMKII expression (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

After CaMKIIγ deletion using shRNA, the cells were subjected to OGD, followed by deprivation for 6 h. The levels of phospho-CaMKII, CaMKII, and β-actin (loading control) were analyzed through Western blotting. Lane 1 control cells without OGD; Lane 2 control cells; Lane 3 cells infected with the CaMKIIγ shRNA lentivirus; Lane 4 cells infected with the control lentivirus

Attenuation of OGD/R-Induced Apoptosis via Suppression of CaMKIIγ

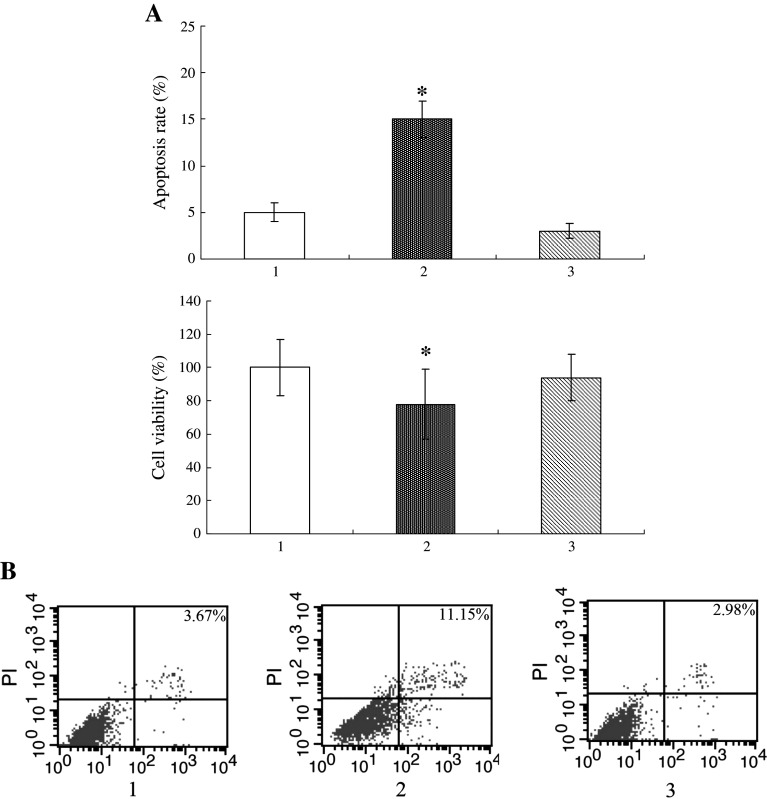

To prove whether CaMKII activation is involved in astrocytes apoptosis under OGD/R, the cells were pretreated with an CaM kinase inhibitor 2-[N-(2-hydroxyethyl)]-N-(4-methoxybenzenesulfonyl)amino-N-(4-chloro-cinnamyl)-N-methylbenzylamine (KN93, 10 μM) and then subjected to OGD/R (Mockett et al. 2011). With KN93 treatment, a marked decrease in phospho-CaMKII and caspase-3 expression was found compare to those cells treated with OGD/R alone (Fig. 3). We used an shRNA to downregulate CaMKIIγ expression to confirm the indispensable role of CaMKIIγ in OGD/R-induced apoptosis in astrocytes. The results of the MTT analyses (Fig. 5a) showed that OGD/R treatment reduced cell viability by approximately 78 % compared with control cells. However, 94 % cell viability was observed in CaMKIIγ knockdown cells under OGD/R conditions. Annexin V/propidium iodide double staining (Fig. 5b) revealed that the frequency of apoptotic cells was reduced from 15 % in the control group to 3 % in the CaMKIIγ-deleted group under OGD/R conditions (Fig. 5a). Thus, knockdown of CaMKIIγ significantly reduced OGD/R-induced astrocyte apoptosis and CaMKII is essential to the astrocyte apoptosis in OGD.

Fig. 5.

After CaMKIIγ deletion using shRNA, the cells were subjected to OGD, followed by deprivation for 6 h. Apoptosis was detected in the astrocytes through examination of cell viability using the MTT assay (a) and annexin V/propidium iodide double staining (b). The quantitative analysis of apoptotic cells presented in the bar graphs represent the average results from three different experiments; *P < 0.05. Lane 1 control cells without OGD; Lane 2 control cells; Lane 3 cells infected with the CaMKIIγ shRNA lentivirus

The CaMKII/ASK1 Pathway Plays an Important Role in OGD/R-Induced Apoptosis

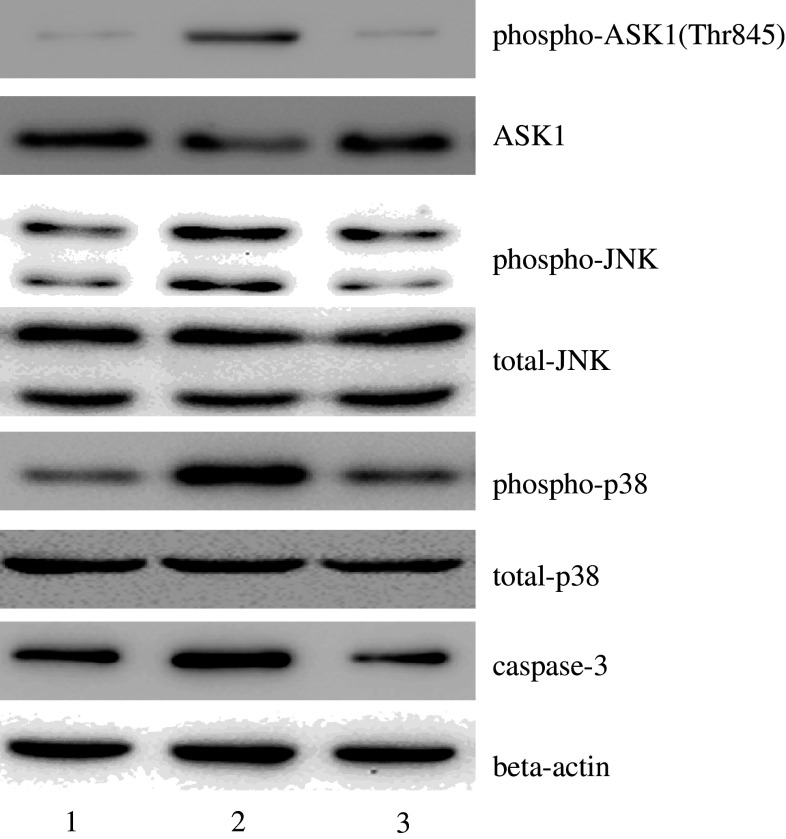

Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) plays key roles in apoptotic responses to oxidative and ER stress. To determine whether ASK1 is associated with CaMKII during OGD/R-induced apoptosis, CaMKIIγ knockdown cells were treated with OGD/R as described. Western blotting showed that the expression of caspase-3 was reduced in CaMKIIγ knockdown cells under OGD/R conditions, concomitant with reduced expression of the activated form of ASK1, phospho-ASK1 (Thr845). Furthermore, the expression of proteins downstream of ASK1, such as JNK and p38, was also reduced (Fig. 6). These data suggest that ASK1 acts downstream of CaMKII in OGD/R-induced apoptosis in astrocytes.

Fig. 6.

After CaMKIIγ deletion using shRNA, the cells were subjected to OGD, followed by deprivation for 6 h. The expression of phospho-ASK1, ASK1, phospho-JNK, JNK, phospho-p38, p38, caspase-3, and β-actin (loading control) was analyzed through Western blotting. Lane 1 control cells without OGD; Lane 2 control cells; Lane 3 cells infected with the CaMKIIγ shRNA lentivirus

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated the important role of CaMKII in ischemia-like injury-induced apoptosis in cultured astrocytes. Most studies described that calcium is released from intracellular stores at late stages during the apoptotic process, and that calcium release may be a point-of-no-return to amplify the apoptotic process (i.e., the execution phase). In this study, the kinetics of CAMKII phosphorylation similar to caspase cleavage, suggesting that CAMKII is activated during the execution phase. The data presented herein also support the hypothesis that CaMKII activation through hypoxia–reoxygenation (H/R) injury is responsible for ROS production in astrocytes and contributes to the amplification of ischemia-like injury. Thus, the inhibition of CaMKII activation could represent a novel protective approach for SCI treatment.

The association between ischemic injury and increased astrocyte damage has been accepted for the past several years based on experimental data (Zheng et al. 2012; Ahmad et al. 2012; Tohda and Kuboyama 2011). Previous work has demonstrated that H/R generates a burst of ROS and leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and ER stress in astrocytes. ER stress–mediated UPR activation in these cells triggers a notable release of calcium from ER stores to the cytosol as well as the accumulation of mitochondrial calcium through a mitochondria-dependent proapoptotic cascade, which activates the calcium-signal transducer CaMKII (Timmins et al. 2009). Astrocytes exposed to OGD/R in vitro undergo apoptosis through both ER stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, suggesting that the activation of CaMKII is associated with OGD/R-induced apoptosis.

In this study, the results of the MTT analysis and annexin V/propidium iodide double staining showed that OGD/R could cause cell death. We also observed that OGD/R increased the expression of phospho-CaMKII, which is involved in the activation of CaMKII. These data suggest that OGD/R-induced apoptosis in astrocytes occurs as a consequence of ROS generation and CaMKII activation. There are four different, highly conserved genes encoding CaMKII: the α, β, γ, and δ genes (Mayer et al. 1995). CaMKIIγ plays an important role in macrophage and endothelial cell apoptosis via linking the ER stress and mitochondrial apoptosis pathways (Timmins et al. 2009). In this study, the deletion of CaMKIIγ resulted in reduced activation of CaMKII and apoptosis in astrocytes under H/R conditions, consistent with previously published data from endothelial cells (Bruno et al. 1994).

Several signaling pathways downstream of CaMKII related to the development of apoptosis have been elucidated. ASK1 is a MAP kinase that plays essential roles in stress-induced apoptosis. ASK1 is activated in response to a variety of stress-related stimuli through distinct mechanisms and subsequently activates MKK4 and MKK3, which in turn, activate JNK and p38 (Shiizaki et al. 2012; Manaenko et al. 2012). The activation of ASK1 activates JNK and p38 MAPK and induces apoptosis in several cell types through signals involving the mitochondrial cell death pathway (Nakagawa et al. 2011; Baregamian et al. 2009). Takeda et al. (2004) have shown that CaMKII directly phosphorylates ASK1. KN93 (an inhibitor of CaMKII) inhibits Ca2+-induced ASK1 phosphorylation, indicating that the phosphorylation of Thr845 in the activation loop of ASK1 is correlated with ASK1 activity and ASK1-dependent apoptosis (Kashiwase et al. 2005). Thus, we hypothesize that CaMKII mediates OGD/R-induced apoptosis in astrocytes via the ASK1 signaling pathway. In this study, the deletion of CaMKIIγ resulted in the reduced activation of CaMKII and phosphorylation of ASK1 at the Thr845 site in astrocytes under H/R conditions. The activation of JNK and p38, downstream of ASK1, was also reduced. These results demonstrated that CaMKII mediates apoptosis via ASK1 activation.

The results of these studies are the first to suggest that the generation of ROS under H/R conditions is coordinated, in part, through the CaMKII-dependent regulation of ASK1, affecting apoptosis in a cell type that is biologically important under SCI. Additional studies are warranted to obtain a better understanding of the biological significance of this effect with respect to astrocyte responses to SCI.

References

- Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E (2006) Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood–brain barrier. Nature Rev 7:41–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A, Genovese T, Impellizzeri D, Crupi R, Velardi E, Marino A, Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S (2012) Reduction of ischemic brain injury by administration of palmitoylethanolamide after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Brain Res 1477:45–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baregamian N, Song J, Bailey CE, Papaconstantinou J, Evers BM, Chung DH (2009) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 control reactive oxygen species release, mitochondrial autophagy, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase/p38 phosphorylation during necrotizing enterocolitis. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2:297–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides A, Pastor D, Santos P, Tranque P, Calvo S (2005) CHOP plays a pivotal role in the astrocyte death induced by oxygen and glucose deprivation. Glia 52:261–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benov L, Sztejnberg L, Fridovich I (1998) Critical evaluation of the use of hydroethidine as a measure of superoxide anion radical. Free Radic Biol Med 25:826–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brnjic S, Olofsson MH, Havelka AM, Linder S (2010) Chemical biology suggests a role for calcium signaling in mediating sustained JNK activation during apoptosis. Mol Biosyst 6:764–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno VM, Goldberg MP, Dugan LL, Giffard RG, Choi DW (1994) Neuroprotective effect of hypothermia in cortical cultures exposed to oxygen–glucose deprivation or excitatory amino acids. J Neurochem 63:1398–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas R, El-Bachá RS, González J, Barreto GE (2012) Mitochondrial functions in astrocytes: neuroprotective implications from oxidative damage by rotenone. Neurosci Res 13:3510–3524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabryel B, Bielecka A, Bernacki J, Łabuzek K, Herman ZS (2011) Immunosuppressant cytoprotection correlates with HMGB1 suppression in primary astrocyte cultures exposed to combined oxygen–glucose deprivation. Pharmacol Rep 63:392–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Duckles SP, Weiss JH, Li X, Krause DN (2012) 17β-Estradiol prevents cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction by an estrogen receptor-dependent mechanism in astrocytes after oxygen–glucose deprivation/reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med 52:2151–2160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung SE, Kim YK, Youn DY, Lim MH, Ko JH, Ahn YS, Lee JH (2010) Down-modulation of Bis sensitizes cell death in C6 glioma cells induced by oxygen–glucose deprivation. Brain Res 1349:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwase K, Higuchi Y, Hirotani S, Yamaguchi O, Hikoso S, Takeda T, Watanabe T, Taniike M, Nakai A, Tsujimoto I, Matsumura Y, Ueno H, Nishida K, Hori M, Otsu K (2005) CaMKII activates ASK1 and NF-kappaB to induce cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 327:136–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Lee MS (2007) STAT1 as a key modulator of cell death. Cell Signal 19:454–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitao T, Takuma K, Kawasaki T, Inoue Y, Ikehara A, Nashida T, Ago Y, Matsuda T (2010) The Na+/Ca2+ exchanger-mediated Ca2+ influx triggers nitric oxide-induced cytotoxicity in cultured astrocytes. Neurochem Int 57:58–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurnellas MP, Nicot A, Shull GE, Elkabes S (2005) Plasma membrane calcium ATPase deficiency causes neuronal pathology in the spinal cord: a potential mechanism for neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury. FASEB J 19:298–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manaenko A, Sun X, Kim C, Yan J, Ma Q, Zhang JH (2012) PAR-1 antagonist SCH79797 ameliorates apoptosis following surgical brain injury through inhibition of ASK1-JNK in rats Neurobiol Dis [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 23000356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mayer P, Mohlig M, Idlibe D, Pfeiffer A (1995) Novel and uncommon isoforms of the calcium sensing enzyme calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II in heart tissue. Basic Res Cardiol 90:372–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JW, Belegu V (2006) Demyelination and remyelination after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 23:345–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockett BG, Gu′evremont D, Wutte M, Hulme SR, Williams JM, Abraham WC (2011) Calcium/calmodulindependent protein kinase II mediates group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent protein synthesis and longterm depression in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 31:7380–7391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa H, Hirata Y, Takeda K, Hayakawa Y, Sato T, Kinoshita H, Sakamoto K, Nakata W, Hikiba Y, Omata M, Yoshida H, Koike K, Ichijo H, Maeda S (2011) Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 inhibits hepatocarcinogenesis by controlling the tumor-suppressing function of stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase. Hepatology 54:185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang YB, Xu LJ, Emery JF, Lee AS, Giffard RG (2011) Overexpressing GRP78 influences Ca2+ handling and function of mitochondria in astrocytes after ischemia-like stress. Mitochondrion 11:279–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronilli V, Miotto G, Canton M, Brini M, Colonna R, Bernardi P, Di Lisa F (1999) Transient and long-lasting openings of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore can be monitored directly in intact cells by changes in mitochondrial calcein fluorescence. Biophys J 76:725–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiizaki S, Naguro I, Ichijo H (2012) Activation mechanisms of ASK1 in response to various stresses and its significance in intracellular signaling Adv Biol Regul [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 23031789 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Swarnkar S, Singh S, Goswami P, Mathur R, Patro IK, Nath C (2012) Astrocyte activation: a key step in rotenone induced cytotoxicity and DNA damage. Neurochem Res 37:2178–2189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano T, Tian GF, Peng W, Lou N, Libionka W, Han X, Nedergaard M (2006) Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci 9:260–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Matsuzawa A, Nishitoh H, Tobiume K, Kishida S, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Ichijo H (2004) Involvement of ASK1 in Ca2+-induced p38 MAP kinase activation. EMBO Rep 5:161–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmins JM, Ozcan L, Seimon TA, Li G, Malagelada C, Backs J, Backs T, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Anderson ME, Tabas I (2009) Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II links ER stress with Fas and mitochondrial apoptosis pathways. J Clin Invest 119:2925–2941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohda C, Kuboyama T (2011) Current and future therapeutic strategies for functional repair of spinal cord injury. Pharmacol Ther 132:57–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GH, Jiang ZL, Li YC, Li X, Shi H, Gao YQ, Vosler PS, Chen J (2011) Free-radical scavenger edaravone treatment confers neuroprotection against traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 28:2123–2134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Sun LG, Ye LP, Wang B, Li Y (2008) Lead-induced stress response in endoplasmic reticulum of astrocytes in CNS. Toxicol Mech Methods 18:751–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A, Zhang J, Sun P, Yao C, Su C, Sui T, Huang H, Cao X, Ge Y (2010) EIF2alpha and caspase-12 activation are involved in oxygen–glucose–serum deprivation/restoration-induced apoptosis of spinal cord astrocytes. Neurosci Lett 478:32–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Flavin MP (2000) Differential sensitivity of rat hippocampal and cortical astrocytes to oxygen–glucose deprivation injury. Neurosci Lett 285:177–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C, Han J, Xia W, Shi S, Liu J, Ying W (2012) NAD(+) administration decreases ischemic brain damage partially by blocking autophagy in a mouse model of brain ischemia. Neurosci Lett 512:67–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]