Abstract

p300 and its homolog cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CBP) are coactivators that were identified to participate in many biological processes including neural development and cognition. Their roles within the rodent spinal cord have not been reported systematically; in this study, their spatiotemporal distribution in the spinal cord of adult rat following chronic constriction injury (CCI) was studied. p300 and CBP expressed predominantly in nuclei in the gray matter of rat spinal cord. Rats undergoing CCI surgery showed increased p300/CBP immunoreactivity (IR) compared with normal control and sham-operated rats. The number of IR cells reached the peak at day 14 following CCI compared with those on day 3, 7, and 21, accompanied with significant behavioral changes of neuropathic pain. Cell-type determination by immunofluorescence at day 14 following CCI revealed that p300 and CBP expressed in neurons, but not in astrocytes or microglial cells. These results suggest that p300 and CBP are probably involved in the maintenance of neuropathic pain on spinal cord level. Furthermore, p300 and CBP may serve as a sensor only in neurons but not in astrocytes or microglia cells in the adult rat spinal cord.

Keywords: Neuropathic pain, CCI, p300, CBP

Introduction

Neuropathic pain is defined as pain after a lesion or disease of the peripheral or central nervous system (Treede et al. 2008; Haanpää et al. 2011), which is characterized by paresthesia, spontaneous pain, hyperalgesia, and allodynia. The pathophysiological mechanisms of neuropathic pain are divided into peripheral sensitization and central sensitization. As a consequence of hyperactivity of peripheral nociceptors after nerve injury, dramatic changes occur in the dorsal horn of spinal cord.

In dorsal horn neurons there are voltage-gated N-calcium channels to facilitate glutamate and release substance P (Tal and Bennett 1994), γ-aminobutyric acid inhibitory control from the interneurons (Moore et al. 2002; Coull et al. 2003), and intracellular cascades in particular the mitogen activated protein kinase system (Ji and Woolf 2001). All of the above contribute to central sensitization in neuropathic pain. Central sensitization could also be augmented by non-neural glial cells in the spinal cord. Spinal cord glia is activated after peripheral nerve injury and is caused to enhance pain by releasing neuroexcitatory glial proinflammatory cytokines and glutamate (Wieseler-Frank et al. 2005).

p300, the adenovirus E1A-associated 300 kDa protein, and CBP are found to play important roles in a wide range of biological processes in nervous system. p300 and CBP are two large, highly related lysine acetyltransferases that function as transcriptional coactivators for many sequence-specific transcription factors through the modification of chromatin (Goodman and Smolik 2000; Iyer et al. 2004). Epigenetic mechanisms silence the expression of pro or antinociceptive genes by inducing heritable changes in gene expression without changing the DNA sequence (Doehring et al. 2011). Histones are DNA-packaging globular proteins that can undergo posttranslational modifications at specific sites of their N-terminus including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, or ubiquitination (Kouzarides 2007).

The ability of p300 and CBP to activate transcription resides in its capacity to acetylate the core histone proteins associated with enhancer or promoter regions of the genes it activates, inducing conformation changes in chromatin and recruitment of auxiliary proteins to activated promoters (Turnell and Mymryk 2006). They also have the capacity to acetylate and regulate the activity of a variety of transcription factors including NFκB, AP-1, and CREB (Basu et al. 2007; Doehring et al. 2011). Enhanced acetylation of NFκB p50 by p300 is reported to increase p50 binding to COX-2 promoter and transcriptional activation (Deng 2002). It is also found that the up-regulation of p300 recruitment to the COX-2 promoter region is through increased CREB and c-Jun binding (Deng et al. 2004, 2007). Arising evidences suggest that COX-2 contributes to the mechanisms underlying hyperalgesia and allodynia at the spinal cord level in neuropathic pain model (Willingale et al. 1997; Ma 2003; Dudhgaonkar et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2010).

Therefore, p300 and CBP likely play important roles in developing and maintenance of neuropathic pain in rat spinal cord. In order to better understand the mechanism, it appears necessary to know the dynamic changes of the two proteins in the spinal dorsal horn in neuropathic pain model. For this purpose, we performed immunohistochemical studies to investigate the changes of p300 and CBP expression in the rat spinal dorsal horn at several time points following chronic constriction injury (CCI). In addition, we evaluated the cell-type determination of these two proteins to explore their underlying mechanisms in neuropathic pain.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Thirty male Sprague–Dawley rats (220–250 g) were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Central South University. All procedures in this study were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Animal Care Committee of Central South University in China approved these procedures. Both animal numbers and suffering used were minimized. Rats were allowed to acclimate for one week after arrival; all animals had free access to food and water with a 12 h light/dark cycle maintained.

The surgery of CCI was prepared as a chronic neuropathic pain model (Bennett and Xie 1988). Each rat was anesthetized with 10 % chloral hydrate (300–350 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection. Then the left sciatic nerve was exposed at the mid-thigh level by blunt dissection. Four snug ligatures of 4–0 chromic gut were placed around the nerve after freeing from the surrounding loose connective tissue. The sutures were placed with just enough pressure to produce mild blanching of the epineurium visible under the operating scope. The interval among ligatures was about 1 mm. Sham surgery was identical except that no ligatures were placed on the sciatic nerves. All the sham and nerve ligations were performed by a single individual. CCI and sham-operated rats were sacrificed by perfusion at 3, 7, 14, and 21 days post surgery.

Behavior Tests

Behavior tests were used to validate the success of CCI surgery. Only rats showing mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia could be used in the following morphological analysis. Ipsilateral thermal hyperalgesia in all rats was monitored by Hargreaves Tes7370 (Ugo Basile, Comerio, Italy), and mechanical allodynia was monitored by 2390 Electronic von Frey Anesthesiometer (IITC Life Science, USA) as previously reported (Cunha et al. 2008). The TWL and MWT in each rat were tested before CCI, and on day 3, 7, 14, and 21 after CCI surgery.

Sample Preparation

Under deep anesthesia, rats were perfused through the ascending aorta with cold 300–400 ml 0.9 % NaCl, and then with 400–500 ml ice-cold 4 % paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4). Rats were sacrificed and their lumbar spinal cords (L4–6) were immediately removed. These samples were postfixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde for 8 h.

Immunocytochemistry Procedures

After dehydration, tissues were embedded with paraffin and cut transversely at 5 μm thickness. The sections were dewaxed and treated with 0.01 M citrate buffer at 80 °C for 20 min for antigen retrieval, followed by 3 % H2O2 for 5 min to eliminate the peroxidase activity. Then sections were blocked with 10 % horse serum for 1 h and incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-CBP antibody (dilution at 1:300; sc-7300, Santa Cruz, USA) or anti-p300 antibody (dilution at 1:300; sc-32244, Santa Cruz, USA) for 24 h at 4 °C, followed by incubation with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (dilution at 1:2,000; vector) for 2 h. After processed with Elite Vectastain ABC kit (dilution at A: 1: 200, B: 1: 200; Vector) for 2 h, the immunoprecipitates were developed by diaminobenzedine (DAB, dilution at A: 1: 200, B: 1: 300, C: 1: 200; Vector). In the interval of incubation, sections were washed with PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4) three times for 10 min. Negative controls lacked the primary antibody.

Images of immunohistochemistry were digitally captured using a Nikon N-STORM Professional CCD Camera. According to the % of maximal mean density level, the number of cells graded “+” was counted as immunoreactive cells (Chung et al. 2002). The mean value in each rat was used in subsequent statistical analysis.

Immunofluorescence Procedures

The immunofluorescence procedures of paraffin section before the antigen retrieval were the same as in the immunohistochemistry ones. Sections were blocked with 3 % goat serum for 1 h, incubated with anti-CBP antibody (dilution at 1:300; sc-369, Santa Cruz, USA) or anti-p300 antibody (dilution at 1:300; sc-585, Santa Cruz, USA) overnight at 4 °C, and incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (dilution at 1:200; vector) for 2 h, followed with red dihydroxyfluorene (dilution at 1:100; 16010045, Jackson) incubation for 2 h. Then the sections were blocked with 10 % horse serum for 1 h, incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-NeuN antibody (dilution at 1:500; MAB377, Chemicon, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-GFAP antibody (dilution at 1:800; MAB360, Chemicon, USA), or mouse monoclonal anti-Iba1 antibody (dilution at 1:200; ab15690, Abcam, USA) overnight at 4 °C, and incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse IgG for 2 h, followed with green dihydroxyfluorene (dilution at 1:200; 16010084, Jackson) incubation for 2 h. Sections were incubated without the primary antibody and processed as described above as negative controls. In the interval of incubation, sections were washed with PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4) three times for 10 min. Double-labeled immunofluorescent sections were scanned with a Leica confocal laser scanning microscope (TCS SP5, Mannheim, Germany).

Statistical Procedures

Behavior testing and morphological analyses were conducted in blinded fashion such that personnel responsible for collecting data did not know which treatment group a rat or a set of slides came from. Values were documented as mean ± SE on the mean (Ishihama et al. 2007). One-way analysis of variance was performed to investigate the difference of the behavioral test among groups and the data from immunocytochemistry, followed by SNK-Q test. P < 0.05 was considered to have statistically significance.

Results

CCI Induced Behavioral Changes of Neuropathic Pain in Rats

CCI rats suffering from neuropathic pain showed typical signs of pain sensitization such as toe closing, licking paw, and dorsiflexion. As shown in Fig. 1, the ipsilateral thermal withdrawal latency (TWL) and mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT) changes in all rats were illustrated. Values of TWL and MWT obtained before surgery from left sides had no statistical significance among all the groups (P > 0.05). Both ipsilateral TWL and MWT in CCI rats decreased obviously on day 3 after CCI surgery compared with those of before CCI or naive rats (P < 0.05), which suggested that thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia had become apparent in CCI rats. The states of decreased values on TWL and MWT persisted until day 21 following CCI (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Dynamic changes of the ipsilateral thermal withdrawal latency (TWL) and mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT) data (mean ± SEM) in rats. a Changes on thermal hyperalgesia in rats. b Changes on mechanical allodynia in rats. # P < 0.05 vresus naive control, *P < 0.05 versus sham-operated group

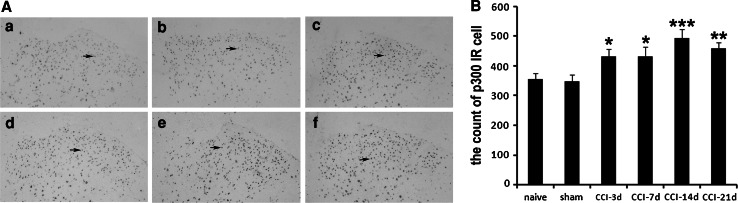

Expression of p300 in Spinal Cord Dorsal Horn

p300-like immunoreactivity (IR) was detectable in the ipsilateral side of spinal cords of all rats. As shown in Fig. 2, p300 was mainly located in the nuclei, scattered throughout the gray matter and the white matter. These cells tended to be more prevalent in the gray matter and appeared more numerous in CCI rats. The mean values of p300 IR cell in CCI groups were obviously higher than that in naive group and sham-operated group (Fig. 2A, P < 0.05). The number of p300 IR cell reached the peak on day 14 following CCI. The grayscale photograph of the dynamic p300 IR cell changes in different observational time is shown in Fig. 2B.

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical staining for p300. Transverse sections of rat lumbar spinal cord were incubated with anti-p300 antibody and detected with an ABC kit and DAB. A Representative images were shown from a to f (×100). a Basic expression of p300 in naive rats. b p300 expression on sham-operated rats. c p300 expression on day 3 after CCI surgery. d p300 expression on day 7 after CCI surgery. e p300 expression on day 14 after CCI surgery. f p300 expression on day 21 after CCI surgery. Representative p300 positive cells in the dorsal horn were pointed by arrows. B Mean p300 immunoreactivity cells by immunohistochemistry at layer I–III of the lumbar spinal dorsal horn in different time points after CCI surgery (n = 5 each). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to naive rats

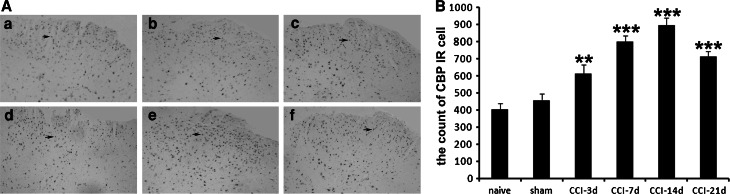

Expression of CBP in Spinal Cord Dorsal Horn

Immunoreactivity for CBP was widespread throughout the gray matter and the white matter of spinal cord. Similar to p300, CBP was also located in the nuclei (Fig. 3A). The results show that up-regulation of CBP expression was significantly higher in ipsilateral dorsal horn of lumber spinal cord after CCI surgery, peaked at 14d and persisted for at least 21d, but was occasionally observed in naive control and sham-operated rats (P < 0.05). Also, the analysis of dynamic p300 IR cell changes in different observational time is shown in Fig. 3B.

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical staining for CBP. A Representative images were shown from a to f (×100). a Basic expression of CBP in naive rats. b CBP expression on sham-operated rats. c CBP expression on day 3 after CCI surgery. d CBP expression on day 7 after CCI surgery. e CBP expression on day 14 after CCI surgery. f CBP expression on day 21 after CCI surgery. Representative CBP positive cells in the dorsal horn were pointed by arrows. B Mean CBP immunoreactivity cells by immunohistochemistry at layer I–III of the lumbar spinal dorsal horn in different time points after CCI surgery (n = 5 each). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to naive rats

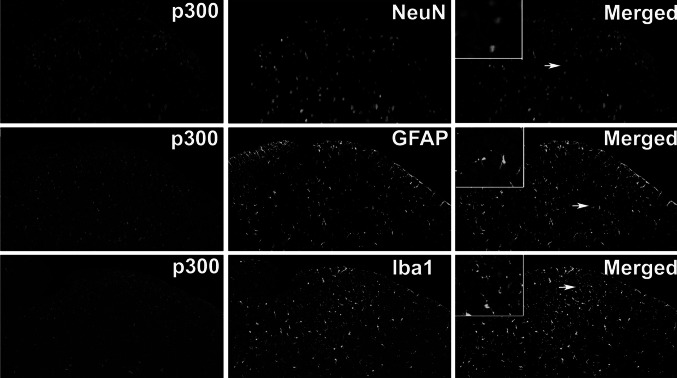

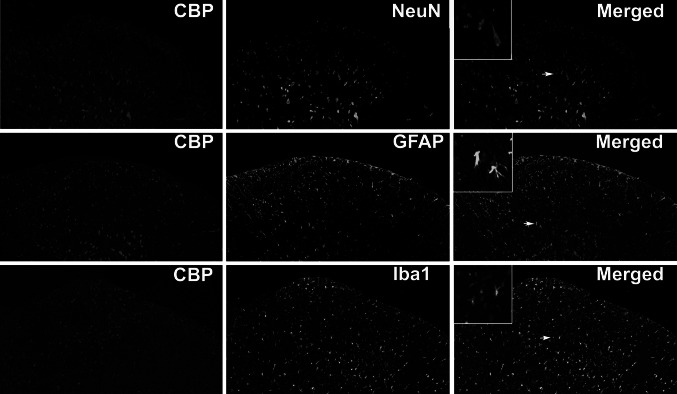

Cell-type Determination for p300 and CBP in Rats on Day 14 Following CCI

In order to identify the cell types that up-regulated p300 and CBP protein expressions after CCI, double immunofluorescence staining p300 or CBP was conducted with markers specific for neurons (neuron-specific nuclear protein, NeuN), astrocytes (Glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP), and microglia (ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1, Iba1). As shown in Figs. 4, 5, p300 or CBP immunoreactive cells were marked with red fluorescence, meanwhile neuron, astrocyte, and microglia were marked with green fluorescence. Almost all the GFAP immunoreactive cells and Iba1 immunoreactive cells were observed negative p300 expression (Fig. 4); the p300 immunoreactive cells were observed to have negative GFAP and Iba1 expression, but positive NeuN expression. p300 immunoreactive cells and NeuN immunoreactive cells merged perfectly (yellow) in the spinal dorsal horn, indicating that p300 may play a role through acting on neurons but not astrocytes or microglial cells after CCI surgery.

Fig. 4.

Cell-type determination for p300 in rat spinal dorsal horn. All experiments were performed with sections of L4–6 spinal cord, 14 day after CCI (×100), and high magnification photomicrographs of the cells to which the arrows point were displayed. Double immunofluorescence labeling for p300 and for cell-type-specific markers: NeuN neurons, GFAP astrocytes, Iba1 microglia cells

Fig. 5.

Cell-type determination for CBP in rat spinal dorsal horn. All experiments were performed with sections of L4–6 spinal cord, 14 day after CCI (×100), and high magnification photomicrographs of the cells to which the arrows point were displayed. Double immunofluorescence labeling for CBP and for cell-type-specific markers: NeuN neurons, GFAP astrocytes, Iba1 microglia cells

Similar results were also shown in the cell pattern determination of CBP. CBP immunoreactive cells merged well with NeuN positive cells (yellow, Fig. 5) but not GFAP positive cells or Iba1 positive cells. The merged images (yellow) indicated that CBP was located in neurons.

Discussion

The spinal cord, especially the spinal dorsal horn, is first emphasized for its critical role for ‘‘gating’’ pain, because it is the first set of synapses in the pain pathway and regulates the flow of afferent information to the central nervous system (Melzack and Wall 1965). In this study, first we reported the detailed analysis of the spatiotemporal distribution of p300 and CBP in the ipsilateral spinal dorsal horn of rats undergoing neuropathic pain. p300 and CBP immunoreactivity expressed densely in the spinal cord dorsal horn of L4–6, especially at layer I–III, which is the major area for nociceptive signaling processing. The time course of changes in p300 and CBP level and the difference in their levels in spinal dorsal horn matched the dynamic alternations of thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia. Characteristic changes of thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia following CCI were demonstrated by the values of TWL and MWT in each time point, which is in agreement with previous studies (Bennett and Xie 1988; Kim and Chung 1992; Üçeyler et al. 2010; Zou et al. 2011; He et al. 2012). The mechanisms underlying the increased immunoreactivity for p300 and CBP in rats undergoing neuropathic pain, and the functional implications of these increases, require further elucidation.

Increasing evidence suggests that neuropathic pain may involve aberrant excitability of the nervous system, notably in nociceptive and spinal dorsal horn neurons, resulting from multiple functional and anatomical alterations following peripheral nerve injury (Woolf and Salter 2000). The nociceptive neurons form synaptic contacts with spinal neurons with some project to higher brain structures and the others form local circuits within the spinal cord (McCleskey 2003). Double-labeled immunofluoresence was used to explore the underlying cell mechanism where p300 and CBP express. Colocalization of p300 and CBP with NeuN were observed in the spinal dorsal horn of rats on day 14 following CCI (Figs. 4, 5, first row), suggesting that there were p300 and CBP expression in dorsal horn neurons. This result is in some degree of consistence with previous study (Stromberg et al. 1999), varying levels of CBP is found to be of critical importance for differences in transcriptional regulation among rat neurons. CBP also acts in retinoic acid-dependent chromatin remodeling for motor neuron genes, thereby enabling proper motor neuron genesis and development (Lee et al. 2009).

Neurons in spinal dorsal horn receive sensory information and changes in nociceptive after peripheral nerve injury. However, neuropathic pain may not be purely the result of miscommunication between the neuron. An increasing number of studies demonstrate that changes after nerve injury also occur in spinal glial cells (Tsuda et al. 2005; Inoue and Tsuda 2009). CCI model, which creates exaggerated pain, is reported to activate astrocyte and microglia (Garrison et al. 1994). Both the two cell types upon activation can produce and release a variety of pain-enhancing substances. Early microglia activation leads in turn to activation of astrocyte, whose activation serves to the maintenance of enhanced pain responses over time in neuropathic pain states (Raghavendra et al. 2003; Ledeboer et al. 2005).

Double-labeled immunofluoresence of p300 and CBP with GFAP were also observed in the CCI rats on day 14 following the surgery. Although there are many studies that prove the critical role of spinal astrocytes in neuropathic pain after spinal nerve ligation (Ji et al. 2006; Kawasaki et al. 2008; Gao et al. 2009), in this study we had not examined any significant morphological manifestation of p300 and CBP in astrocytes on protein level (Figs. 4, 5, middle row). The involvement of p300 and CBP in different signaling pathways with consequences to regulate target gene expression is detected in rat astrocytes of central nervous system (Giri et al. 2004; Fonte et al. 2007) and human astrocytoma astrocytes (Zou et al. 2010). Double-labeling p300 and CBP with Iba1 were also performed. Similar to GFAP, p300 and CBP were not detected double-labeled with Iba1 (Figs. 4, 5, last row). Surprisingly, there are studies reporting that spinal microglia cells are activated in the dorsal horn in a wide variety of peripheral nerve injury models and implicated in neuropathic pain (Tsuda et al. 2009; Mei et al. 2011; Kobayashi et al. 2011; He et al. 2012).

Since we only explored the time point of 14 day after CCI surgery, which means a durative state of neuropathic pain, whether p300 and CBP express in astrocytes or microglial cells on the onset of neuropathic pain cannot be excluded. Or it is possibly because that there are no signal pathways which exist for p300 and CBP in CCI induced neuropathic pain on spinal cord level.

In summary, our results demonstrate the dynamic and increased expression of p300 and CBP in the spinal dorsal horn after CCI surgery, and notable p300 and CBP immunoreactive neurons on day 14 following CCI. The aggravated neuropathic pain is likely to be associated with the effects of p300 and CBP on neurons in the spinal cord, which are implicated in the maintenance of nociceptive hypersensitization. These results may provide useful data for investigating the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain on the two coactivators.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Grant (No. 81000478) from National Natural Science Foundation of China. We thank Prof. Jian-yi Zhang (Anatomy Department, Xiangya School of Medicine) for granting us anti-GFAP (MAB360).

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no biomedical financial interest or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Basu S, Pathak S, Pathak SK, Bhattacharyya A, Banerjee A, Kundu M, Basu J (2007) Mycobacterium avium-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression occurs in a cyclooxygenase-2-dependent manner and involves phosphorylation- and acetylation-dependent chromatin modification. Cell Microbiol 9(12):2804–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GJ, Xie YK (1988) A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain 33(1):87–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YH, Kim EJ, Shin CM, Joo KM, Kim MJ, Woo HW, Cha CI (2002) Age-related changes in CREB binding protein immunoreactivity in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of rats. Brain Res 956(2):312–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull JA, Boudreau D, Bachand K, Prescott SA, Nault F, Sik A, De Koninck P, De Koninck Y (2003) Trans-synaptic shift in anion gradient in spinal lamina I neurons as a mechanism of neuropathic pain. Nature 424(6951):938–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha TM, Verri WA Jr, Valerio DA, Guerrero AT, Nogueira LG, Vieira SM, Souza DG, Teixeira MM, Poole S, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ (2008) Role of cytokines in mediating mechanical hypernociception in a model of delayed-type hypersensitivity in mice. Eur J Pain 12(8):1059–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng WG (2002) Up-regulation of p300 binding and p50 acetylation in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced cyclooxygenase-2 promoter activation. J Biol Chem 278(7):4770–4777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng WG, Zhu Y, Wu KK (2004) Role of p300 and PCAF in regulating cyclooxygenase-2 promoter activation by inflammatory mediators. Blood 103(6):2135–2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng WG, Montero AJ, Wu KK (2007) Interferon-suppresses cyclooxygenase-2 promoter activity by inhibiting C-Jun and C/EBP binding. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27(8):1752–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doehring A, Geisslinger G, Lötsch J (2011) Epigenetics in pain and analgesia: an imminent research field. Eur J Pain 15(1):11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudhgaonkar S, Tandan S, Kumar D, Naik A, Raviprakash V (2007) Ameliorative effect of combined administration of inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibitor with cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in neuropathic pain in rats. Eur J Pain 11(5):528–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonte C, Trousson A, Grenier J, Schumacher M, Massaad C (2007) Opposite effects of CBP and p300 in glucocorticoid signaling in astrocytes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 104(3–5):220–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YJ, Zhang L, Samad OA, Suter MR, Yasuhiko K, Xu ZZ, Park JY, Lind AL, Ma Q, Ji RR (2009) JNK-induced MCP-1 production in spinal cord astrocytes contributes to central sensitization and neuropathic pain. J Neurosci 29(13):4096–4108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CJ, Dougherty PM, Carlton SM (1994) GFAP expression in lumbar spinal cord of naive and neuropathic rats treated with MK-801. Exp Neurol 129(2):237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri S, Rattan R, Singh AK, Singh I (2004) The 15-deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 inhibits the inflammatory response in primary rat astrocytes via down-regulating multiple steps in phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt-NF-kappaB-p300 pathway independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Immunol 173(8):5196–5208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RH, Smolik S (2000) CBP/p300 in cell growth, transformation, and development. Genes Dev 14(13):1553–1577 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haanpää M, Attal N, Backonja M, Baron R, Bennett M, Bouhassira D, Cruccu G, Hansson P, Haythornthwaite JA, Iannetti GD, Jensen TS, Kauppila T, Nurmikko TJ, Rice ASC, Rowbotham M, Serra J, Sommer C, Smith BH, Treede R-D (2011) NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment. Pain 152(1):14–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He WJ, Cui J, Du L, Zhao YD, Burnstock G, Zhou HD, Ruan HZ (2012) Spinal P2X(7) receptor mediates microglia activation-induced neuropathic pain in the sciatic nerve injury rat model. Behav Brain Res 226(1):163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Tsuda M (2009) Microglia and neuropathic pain. Glia 57(14):1469–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama K, Yamakawa M, Semba S, Takeda H, Kawata S, Kimura S, Kimura W (2007) Expression of HDAC1 and CBP/p300 in human colorectal carcinomas. J Clin Pathol 60(11):1205–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer NG, Ozdag H, Caldas C (2004) p300/CBP and cancer. Oncogene 23(24):4225–4231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Woolf CJ (2001) Neuronal plasticity and signal transduction in nociceptive neurons: implications for the initiation and maintenance of pathological pain. Neurobiol Dis 8(1):1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Kawasaki Y, Zhuang ZY, Wen YR, Decosterd I (2006) Possible role of spinal astrocytes in maintaining chronic pain sensitization: review of current evidence with focus on bFGF/JNK pathway. Neuron Glia Biol 2(4):259–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y, Xu ZZ, Wang X, Park JY, Zhuang ZY, Tan PH, Gao YJ, Roy K, Corfas G, Lo EH, Ji RR (2008) Distinct roles of matrix metalloproteases in the early- and late-phase development of neuropathic pain. Nat Med 14(3):331–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Chung JM (1992) An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain 50(3):355–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Takahashi E, Miyagawa Y, Yamanaka H, Noguchi K (2011) Induction of the P2X7 receptor in spinal microglia in a neuropathic pain model. Neurosci Lett 504(1):57–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T (2007) Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128(4):693–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledeboer A, Sloane EM, Milligan ED, Frank MG, Mahony JH, Maier SF, Watkins LR (2005) Minocycline attenuates mechanical allodynia and proinflammatory cytokine expression in rat models of pain facilitation. Pain 115(1–2):71–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee B, Lee JW, Lee SK (2009) Retinoid signaling and neurogenin2 function are coupled for the specification of spinal motor neurons through a chromatin modifier CBP. Neuron 62(5):641–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W (2003) Cyclooxygenase 2 in infiltrating inflammatory cells in injured nerve is universally up-regulated following various types of peripheral nerve injury. Neuroscience 121(3):691–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleskey EW (2003) Neurobiology: new player in pain. Nature 424(6950):729–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei XP, Zhou Y, Wang W, Tang J, Zhang H, Xu LX, Li YQ (2011) Ketamine depresses toll-like receptor 3 signaling in spinal microglia in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Neurosignals 19(1):44–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R, Wall PD (1965) Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science 150(3699):971–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KA, Kohno T, Karchewski LA, Scholz J, Baba H, Woolf CJ (2002) Partial peripheral nerve injury promotes a selective loss of GABAergic inhibition in the superficial dorsal horn of the spinal cord. J Neurosci 22(15):6724–6731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra V, Tanga F, DeLeo JA (2003) Inhibition of microglial activation attenuates the development but not existing hypersensitivity in a rat model of neuropathy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306(2):624–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg H, Svensson SP, Hermanson O (1999) Distribution of CREB-binding protein immunoreactivity in the adult rat brain. Brain Res 818(2):510–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal M, Bennett GJ (1994) Extra-territorial pain in rats with a peripheral mononeuropathy: mechano-hyperalgesia and mechano-allodynia in the territory of an uninjured nerve. Pain 57(3):375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, Hansson P, Hughes R, Nurmikko T, Serra J (2008) Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology 70(18):1630–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Inoue K, Salter MW (2005) Neuropathic pain and spinal microglia: a big problem from molecules in “small”glia. Trends Neurosci 28(2):101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Masuda T, Kitano J, Shimoyama H, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Inoue K (2009) IFN-gamma receptor signaling mediates spinal microglia activation driving neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(19):8032–8037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnell AS, Mymryk JS (2006) Roles for the coactivators CBP and p300 and the APC/C E3 ubiquitin ligase in E1A-dependent cell transformation. Br J Cancer 95(5):555–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üçeyler N, Biko L, Sommer C (2010) MDL-28170 has no analgesic effect on CCI induced neuropathic pain in mice. Molecules 15(5):3038–3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang X, Guo Q-L, Zou W-Y, Huang C-S, Yan J-Q (2010) Cyclooxygenase inhibitors suppress the expression of P2X3 receptors in the DRG and attenuate hyperalgesia following chronic constriction injury in rats. Neurosci Lett 478(2):77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieseler-Frank J, Maier SF, Watkins LR (2005) Central proinflammatory cytokines and pain enhancement. Neurosignals 14(4):166–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willingale HL, Gardiner NJ, McLymont N, Giblett S, Grubb BD (1997) Prostanoids synthesized by cyclo-oxygenase isoforms in rat spinal cord and their contribution to the development of neuronal hyperexcitability. Br J Pharmacol 122(8):1593–1604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Salter MW (2000) Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science 288(5472):1765–1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W, Wang Z, Liu Y, Fan Y, Zhou BY, Yang XF, He JJ (2010) Involvement of p300 in constitutive and HIV-1 Tat-activated expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein in astrocytes. Glia 58(13):1640–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W, Song Z, Guo Q, Liu C, Zhang Z, Zhang Y (2011) Intrathecal lentiviral-mediated RNA interference targeting PKCγ attenuates chronic constriction injury–induced neuropathic pain in rats. Hum Gene Ther 22(4):465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]