Abstract

Interspecies hybrids have nuclear contributions from two species but oocyte cytoplasm from only one. Species discordance may lead to altered nuclear reprogramming of the foreign paternal genome. We reasoned that initial reprogramming in same species cytoplasm plus creation of hybrids with zygote cytoplasm from both species, which we describe here, might enhance nuclear reprogramming and promote hybrid development. We report in Mus species that (i) mammalian nuclear/cytoplasmic hybrids can be created, (ii) they allow development and viability of a previously missing and uncharacterized hybrid class, (iii) different oocyte cytoplasm environments lead to different phenotypes of same nuclear hybrid genotype, and (iv) the novel hybrids exhibit sex ratio distortion with the absence of female progeny and represent a mammalian exception to Haldane’s rule. Our results emphasize that interspecies hybrid phenotypes are not only the result of nuclear gene epistatic interactions but also cytonuclear interactions and that the latter have major impacts on fetal and placental growth and development.

True interspecies hybrids with a hybrid nuclear genome and zygote cytoplasm are created and described for growth and metabolism.

INTRODUCTION

Fertilization unites two gametes each with a distinct epigenetic legacy created during gametogenesis. The maternal and especially the paternal epigenomes undergo extensive reprogramming after fertilization in preparation for embryonic genome activation (EGA), which, in the mouse, occurs in minor and major stages at the one-cell and two-cell stages, respectively (1). Epigenome changes are rapid in onset, dynamic, and embryo stage specific. They are also species-specific. The highly condensed protamine-rich paternal genome must undergo extensive reprogramming directed by stored maternal cytoplasmic elements. This involves multiple discrete steps including sperm chromatin decondensation (2), protamine phosphorylation and removal (3), rapid demethylation starting prior to paternal genome DNA replication (4, 5), replication-independent deposition of histone H3.3 (6–10), and subsequent nucleosome deposition (11, 12). Epigenetic regulation of the transcriptome also includes histone tail modifications (13, 14).

Given this dynamic reorganization and epigenome modification of a same species (intraspecies) paternal genome, it is reasonable to wonder if an interspecies paternal genome can recapitulate these same modifications. In some ways, this question is similar to the reprogramming demanded of somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) embryos and the analogous challenges to reprogramming encountered in interspecies SCNT (iSCNT). For the latter, it is known that, when the two species are substantially separated in evolution, developmental arrest around the time of EGA is almost always seen (15–19), indicative of failed EGA in evolutionarily divergent iSCNT embryos (19). iSCNT of more closely related species, however, can lead to advanced fetal development (20, 21) or birth of a live animal (22). Evolutionary distance alone, however, does not always predict hybrid development and viability as viable hybrids are sometimes evident in only one of the two reciprocal crosses between two species. This discordance between the two reciprocal crosses is known as Darwin’s corollary to Haldane’s rule (23). For example, small and large conceptuses, which are viable and nonviable, respectively, result from reciprocal interspecies crosses in Peromyscus (deer mice) (24–27) and Phodopus (dwarf hamster) (28, 29). In the genus Mus, hybridization of Mus domesticus females and Mus spretus males yield viable and small domM/sprP/domC hybrids (dom refers to domesticus, spr refers to spretus, and the M, P, and C superscripts refer to the reference maternal, paternal, and cytoplasm, respectively) but the reciprocal hybrid class sprM/domP/sprC cannot be readily produced.

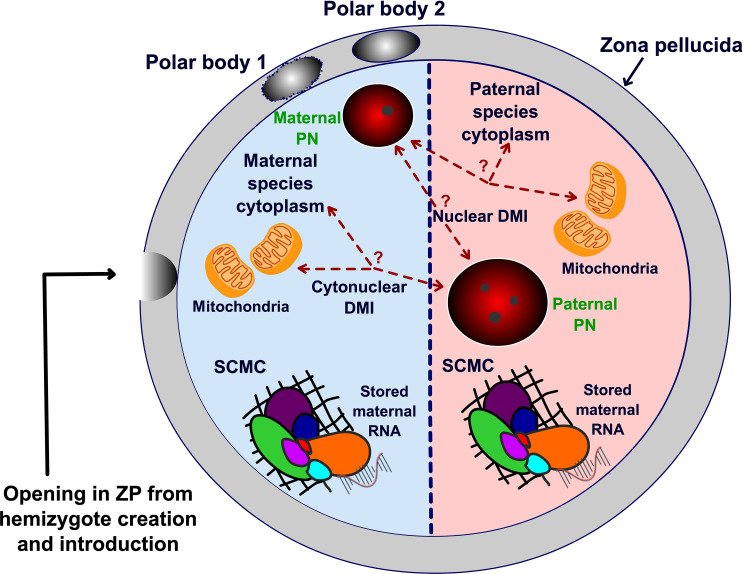

As a means to explain abnormal hybrid phenotypes between species, Dobzhansky, Muller, and Bateson proposed a model that invokes genetic incompatibilities (Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities or DMIs) in which epistatic interactions lead to reduced fitness between alleles of heterospecific origin (30–34). DMIs may be genic or cytonuclear in origin; however, distinguishing between these two possibilities is made difficult as oocyte cytoplasm, which includes self-replicating organelles, and a haploid maternal genome are co-inherited. For all these reasons, an ability to separate the maternal nucleus from the maternal cytoplasm would be a useful first step to address the DMI origin and assess if different species cytoplasms alter hybrid phenotype. We therefore adopted a nuclear and cytoplasmic transfer approach in two Mus species, Mus musculus domesticus and Mus spretus, that creates and then combines two single pronucleus hemizygotes together to reconstitute a diploid zygote, which has interspecies nucleus and cytoplasm. We refer to these novel embryo constructs as “true hybrids” to reflect their true dual species origin. These true hybrids differ from traditional hybrids in two important ways. First, fertilization is intraspecies so that the initial reprogramming of the paternal genome takes place with same species cytoplasm. Second, same species cytoplasm is present, albeit in a reduced amount, after hemizygote fusion. The role of the continued presence of this same species cytoplasm on development and phenotype in these true hybrids is appreciated by comparing hemizygote fusion with pronuclear transfer without cytoplasm (Fig. 1). To the extent that nuclear/cytoplasmic incompatibilities prevent normal hybrid growth and development, our true hybrids could possibly circumvent such outcomes and lead to the creation of hybrids that otherwise could not exist.

Fig. 1. Control single pronuclear and novel true interspecific hybrid zygotes are created as schematized.

Interspecies hybrids are created using nuclear and cytoplasmic transfer to evaluate if different species cytoplasms alter hybrid phenotype. Comparison of A versus B versus C allows determination of if paternal species zygote cytoplasm alters hybrid molecular and physical phenotype and potentially improves creation and survival of novel hybrids. I and II. Single paternal and maternal control pronuclear transfers between dom (dark red) and spr (dark blue) zygotes to create interspecies hybrid with zygote cytoplasm from only one species (spr: light blue; dom: light pink). Donor and recipient can be altered to determine cytoplasm origin. III. Creation and fusion of two hemizygotes to create interspecies hybrid with hybrid cytoplasm (yellow).

RESULTS

True hybrid creation

In our hands, laboratory breeding of dom female X spr male crosses yields viable progeny whereas the reciprocal cross does not. spr females caged with dom males never appeared pregnant, leading us to believe that this cross suffers from a reproductive barrier in either mating/fertilization or early embryo lethality. We observed decreased in vivo fertilization of oocytes from F1 (dom X spr) females when mated with dom but not spr males (table S1), consistent with a partial fertilization barrier even in the F1 backcross generation.

Microsurgery is a modification of methods initially described by McGrath and Solter (35). The creation of a true hybrid requires hemizygotes from each species, each containing a single pronucleus and ½ volume of zygote cytoplasm. Two hemizygotes are then fused together, thereby reconstituting a diploid biparental interspecies genome surrounded by hybrid cytoplasm. We created two hemizygotes, one with a zona pellucida (ZP) and one without. First, ZP-surrounded “recipient” hemizygotes are created with an enucleation pipette 20 to 22 µm in diameter to allow the removal of ½ volume cytoplasm along with a single pronucleus (movie S1). Second, donor hemizygotes of the second species are created by removal of the ZP followed by suction of one pronucleus and ½ volume cytoplasm into a nonbeveled 22 to 25 µm micropipette. The portion of the zygote that remains outside the nonbeveled pipette is then approached by a second large blunt and polished holding pipette. The exposed ½ zygote is then aspirated into the lumen of the holding pipette, and the two pipettes withdrawn until the cytoplasmic bridge between the two hemizygotes is stretched to a thread, separates, and reseals (movie S2). The zonaless hemizygote in the holding pipette is then expelled. The nonbeveled pipette containing the hemizygote is moved to a microdrop containing Sendai virus protein and a small volume aspirated. The nonbeveled pipette is now positioned adjacent to a holding pipette with the zona surrounded hemizygote carefully positioned so that the hole in the ZP is adjacent to the blunt tipped pipette. The blunt pipette is then advanced to deform the ZP and seal the space between the ZP and blunt pipette so that, when ejected, the zonaless hemizygote flows through the hole and into the perivitelline space (PVS). Leakage of the hemizygote outside the ZP means that the ZP and blunt pipette are not adequately positioned and must be realigned. When properly positioned, the zonaless hemizygote is then carefully injected into the PVS of the ZP surrounded hemizygote. It is critical to assign the parental origin to each pronucleus via its position in the zygote so that only biparental embryos are reconstructed. Fusion of the two hemizygotes is demonstrated in movie S3. Creation of control single pronuclear and true interspecific hybrid zygotes is diagrammed in Fig. 1.

Progeny born

Before creation of interspecies true hybrids, we made control intraspecies dom embryo nuclear/cytoplasmic hybrids. Seven such progeny were born and survived to adulthood, indicating that the procedure is well tolerated. Table 1 lists five groups of hybrid and control embryos with the microsurgical manipulation performed, the resultant genotype of the embryo and the number of liveborn progeny for each. Control maternal or paternal intraspecies single pronucleus transfers were used to assess survival to birth in wild-type dom homozygotes following the transfer of a single maternal or paternal pronucleus. Twenty-nine percent of paternal pronucleus transfers and 23% of maternal single pronucleus transfers resulted in liveborn progeny (Table 1, B and D, respectively). In contrast, when a single domP paternal pronucleus was transferred into a spr zygote in an attempt to create sprM/domP/sprC hybrids, no liveborn offspring resulted (Table 1B versus Table 1A; X2 = 13.03, P < 0.001). This result shows that, even when mating/fertilization barriers are circumvented to create the missing sprM/domP/sprC hybrid class, an in utero lethal phenotype results. Two stillborns were observed in the sprM/domP/sprC hybrid group on C-section at the end of gestation, indicating that, in rare instances (<5%), development to term was approximated but not successful. An isolated placenta without a fetus was also found in a third pseudopregnant female that received sprM/domP/sprC embryos. We asked if creating the same hybrid genotype in two different non–spr cytoplasmic environments would restore viability. First, we transferred a sprM pronucleus into a dom zygote, creating sprM/domP/domC hybrids where the sprM/domP hybrid genome now resides in dom cytoplasm (Table 1C). In contrast to the same genotype in spr cytoplasm (Table 1A), in dom zygote cytoplasm, 6% of the sprM/domP hybrids were viable at birth and survived until adulthood. This 6% viability of the sprM/domP/domC genotype is significantly less than that observed in control maternal pronucleus domM/domP/domC transfer embryos (6% versus 23%; X2 = 4.164, P < 0.05), indicating reduced viability but does demonstrate that, in a different cytoplasmic environment, domC versus sprC, viability of the hybrid sprM/domP genome is possible.

Table 1. Creation of sprM/domP hybrids in hybrid cytoplasm rescues the sprM/domP nuclear genotype in hybrid cytoplasm, with a survival rate approaching that of single pronuclear transfer controls.

Viability of hybrids and controls. PN, pronuclear.

| Manipulation | Genotype | Livebirths/total | % | Experiment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | domP → sprM/sprP/sprC | sprM/domP/sprC | 0/64* | 0 | PN transfer |

| B | domP → domM/domP/domC control | domM/domP/domC | 20/70 | 29 | PN transfer |

| C | sprM → domM/domP/domC | sprM/domP/domC | 3/49 | 6 | PN transfer |

| D | domM → domM/domP/domC control | domM/domP/domC | 12/53 | 23 | PN transfer |

| E | sprM hemizygote ↔ domP hemizygote fusion true hybrid | sprM/domP/hybridC | 7/29 | 24 | PN + cytoplasmic transfer |

*Two stillborn and in a third conceptus, an isolated placenta without a fetus was noted. The association between categorical data was assessed by the chi-square test for the viability of hybrids and controls.

We also created sprM/domP hybrids in hybrid cytoplasm (Table 1E). Here, the viability of the true sprM/domP/hybridC hybrids was 24%, indicating rescue of the sprM/domP nuclear genotype in hybrid cytoplasm at a survival rate approaching that of single pronuclear transfer controls (23% versus 29%). Of the seven true hybrids born, one died at birth, and one was cannibalized by the mother, along with three dom control littermates, at 8 days of age. The remaining five pups survived to adulthood and lived for over 2 years. Confirmation of the dom paternal genome in the five surviving true hybrids was obtained by sequencing of a Sry polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplicon that contained three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between the dom and spr Sry gene (fig. S1). In each true hybrid, the SNPs were all dom in origin as expected. We therefore show that the missing sprM/domP nuclear genotype can be rescued if the mating/fertilization barrier is circumvented and if the cytoplasm of the zygote is not sprC. We note that increased survival was achieved with hybrid cytoplasm versus dom cytoplasm (24% versus 6%).

Birth and placental weights and postnatal growth in parental species and hybrids

Birth and placental weights of hybrids and controls are shown in Table 2. Day of delivery is designated postnatal day 0 (P0). Daily weights were measured until weaning (P21). Male and female mice are separated by sex determination measuring anogenital distance and placed in cages with a maximum of five mice each. After weaning, males and females were weighed weekly but, because hybrids were male only, only male control weights are shown for comparison (Fig. 2, A and B).

Table 2. spr cytoplasm combined with a dom paternal pronucleus leads to massive overgrowth with a mean birth weight and the most severe placentomegaly.

Growth of placenta and fetus in hybrids and controls.

| Manipulation | Genotype | Mean birth weight g (N) | Mean placenta weight g (N) | Placental/fetal weight ratio | Experiment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | domP → sprM/sprP/sprC | sprM/domP/sprC | 2.75 ± 0.23 (2)* | 0.92 ± 0.06 (3) | 0.33 | PN transfer |

| B | domP → domM/domP/domC control | domM/domP/domC | 1.58 ± 0.034 (7) | 0.12 ± 0.004 (7) | 0.08 | PN transfer |

| C | sprM → domM/domP/domC | sprM/domP/domC | 1.85 ± 0.07 (3) | 0.58 ± 0.06 (3) | 0.31 | PN transfer |

| D | domM → domM/domP/domC control | domM/domP/domC | 1.28 ± 0.031 (10) | 0.11 ± 0.012 (10) | 0.09 | PN transfer |

| E | sprM hemizygote ↔ domP hemizygote fusion true hybrid | sprM/domP/hybridC | 2.63 ± 0.17 (5) | 0.57 ± 0.02 (3) | 0.22 | PN + cytoplasmic transfer |

*The two fetuses were stillborn.

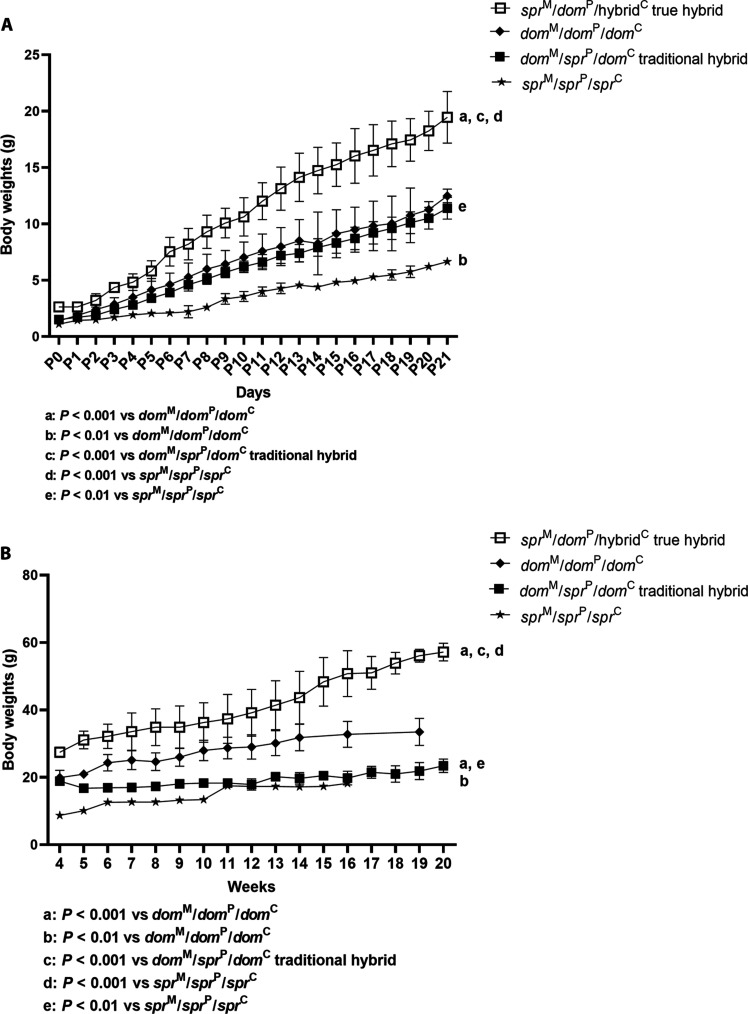

Fig. 2. sprM/domP/hybridC true hybrids show significantly increased body weight compared to the parental species, and this increased size persists postnatally.

(A) Preweaning weight in grams over time for parental species and hybrids. At birth, the sprM/domP/hybridC hybrids were 66% larger than the two parental species, dom. At 21 days, the same sprM/domP/hybridC hybrids were ~50% larger than the dom species (P < 0.001), and this increased size persists postnatally in weeks (P < 0.001). In vivo–generated control domM/sprP/domC embryos and domM/domP/domC embryos were transferred to CD-1 pseudopregnant females. (B) Weight in grams for dom, spr, and hybrid males through adulthood. The normality of the data was checked with the Shapiro-Wilk test, and because the data were normally distributed, group comparisons were analyzed by ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni test.

The two stillborn term sprM/domP/sprC fetuses derived from single paternal dom pronucleus transfer showed massive overgrowth with a mean weight of 2.75 ± 0.23 g at C-section compared to 1.58 ± 0.034 g for control intraspecies domP pronucleus transfers (Table 2A versus Table 2B). This represents a 75% increase in birth weight. The overgrowth of the three accompanying sprM/domP/sprC placentas was even more marked and averaged 0.92 ± 0.06 g in interspecies domP pronucleus transfer placentas, a marked 7- to 8-fold increase in placental weight for these lethal hybrids (0.92 ± 0.06 g versus 0.12 ± 0.004 g). Notably the same nuclear genotype, sprM/domP, in dom or hybrid cytoplasm showed less placentomegaly and, as noted before in Table 1, viability of some hybrids (6% dom cytoplasm; 24% hybrid cytoplasm) was observed. The sprM/domP/domC hybrids were larger than the dom control mice. In the true hybrids, birth weights were 66% larger than the controls (2.63 ± 0.17 g versus 1.58 ± 0.034 g; Fig. 3A) and similar in weight to the lethal single pronuclear transfer pups (2.75 ± 0.23 g). However, the true hybrid placental weight was smaller than the single pronuclear transfer placentas (0.57 ± 0.02 g versus 0.92 ± 0.06 g) and resembled the placentas observed in the sprM/domP/domC hybrid class (0.58 ± 0.06 g). In summary, our data show that different cytoplasms alter placental and fetal growth to a different degree in interspecies hybrids, leading to distinct growth phenotypes in the sprM/domP nuclear genotype in different cytoplasmic environments. spr cytoplasm combined with a dom paternal pronucleus led to the most severe placental overgrowth and was accompanied by embryonic lethality, dom cytoplasm resulted in more placental than fetal overgrowth, and hybrid cytoplasm had fetal overgrowth, which was also accompanied by enhanced viability. Placental overgrowth did not always correlate with fetal size.

Fig. 3. True hybrids are notably larger in size.

Four littermates from CD1 pseudopregnant female at postnatal days (P) 0 (A), 7 (B), 13 (C), and 23 (D). The black coat color pup is a C57BL/6J control. The three agouti (brown) pups are true hybrids (sprM/domP/hybridC). Scale bars, 1 cm [(A), (B), and (C)] and 2 cm (D).

Postnatal growth of hybrid animals

We characterized growth phenotype by daily weight measurements until weaning (Fig. 2A) and weekly weight measurements thereafter (Fig. 2B). Daily weights up until weaning consisted of both sexes, which are similar, while weekly weights after weaning compared only male weights because hybrids were always male. To determine the differences in weight gain between the groups, the differences were compared and a significant difference was found between the groups for both daily and weekly weight measurements (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively). The data indicate that (i) the spr (N = 12) (P < 0.01) and in vivo–generated traditional hybrid domM/sprP/domC animals (N = 12) are smaller than the control intermediate size dom animals (N = 17) through adulthood (P < 0.001), while (ii) the five surviving sprM/domP/hybridC true hybrids all had significantly increased weight compared to the larger dom parental species (P < 0.001) and this increased size persists postnatally (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2, A and B, Fig. 3, and fig. S2).

In summary, single male pronuclear transfer, which created the missing sprM/domP hybrid class, was unable to produce viable progeny in spr cytoplasm but decreased placental overgrowth and viability resulted in the same nuclear genotype in hybrid and dom cytoplasm. We believe that hybrid cytoplasm ameliorated the placental overgrowth and restored normal viability to this hybrid class.

Does F1 (domM X sprP) oocyte cytoplasm resemble true hybrid cytoplasm?

The cytoplasm of the F1 interspecies hybrid female oocyte contains stored nuclear genome products from both species. We observed that the sprM/domP nuclear genotype was inviable and with extreme fetal and placental overgrowth in spr cytoplasm but was viable and with less overgrowth with hybrid or dom cytoplasm. We interpret this observation to indicate that the paternal dom genome has an increased growth promoting phenotype in response to spr cytoplasm. If true, then a homozygous dom genotype in F1 domM/sprP cytoplasm could promote increased fetal/placental growth if stored nuclear encoded spr cytoplasmic elements resulted in domP genome growth promotion (but not spr maternal self-replicating elements owing to the dom maternal grandparent used to create the F1 female). To test this, zygotes from F1 females (domM X sprP) mated to dom males (F1M/domP/F1C) had the F1 maternal pronucleus replaced with a dom maternal pronucleus. Similarly, manipulated F1 females mated to spr males served as controls. The results show that embryos undergoing maternal pronuclear transfer developed to term at a high rate as did the control F1 embryos mated to spr males (Table 3). They also show that the homozygous dom nuclear genotype and thus the paternal dom genome in the F1 cytoplasm did not exhibit increased placental or fetal growth (Table 4A) and were similar to the control F1 embryos mated to spr males. We interpret this result to mean that the increased growth and lethality of sprM/domP/sprC hybrids most likely results from a cytoplasmic element present in sprC that, in combination with a paternal dom genome, results in extreme overgrowth and lethality. This putative spr cytoplasmic element appears to be absent from the cytoplasm of F1 oocytes derived from a dom grandmother.

Table 3. Embryos that underwent maternal pronuclear transfer develop to term at a high rate as does the control F1 embryos mated to spr males.

Viability of single pronucleus transfers in the F1 cytoplasm.

| Manipulation | Genotype | Livebirths/total | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | domM → F1M/domP/F1C | domM/domP/F1C | 14/36 | 39 |

| B | domM → F1M/sprP/F1C | domM/sprP/F1C | 7/16 | 44 |

Table 4. Homozygous dom nuclear genotype and the paternal dom genome in the F1 cytoplasm do not show increased placental or fetal growth and are similar to the control F1 embryos mated to spr males.

Growth of placenta and fetus in the F1 cytoplasm.

| Manipulation | Genotype | Mean birth weight g (N) | Mean placenta weight g (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | domM → F1M/domP/F1C | domM/domP/F1C | 1.36 ± 0.07 (14) | 0.11 ± 0.014 (14) |

| B | domM → F1M/sprP/F1C | domM/sprP/F1C | 1.21 ± 0.07 (7) | 0.08 ± 0.007 (7) |

Hybrid metabolism

To determine if increased growth in true hybrids was due to lean body versus fat mass, we used quantitative nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and measured respiratory parameters and behaviors with metabolic cages and open field tests in the sprM/domP/hybridC true hybrids, traditional hybrids (domM/sprP/domC), and parental strain controls (36). All measurements were made with male control mice matched for age with hybrid animals.

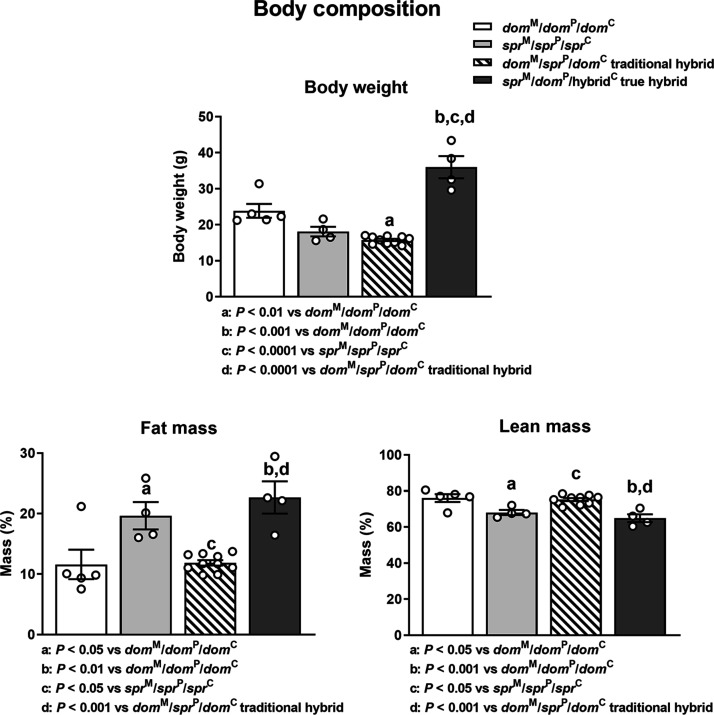

Investigation of body weight shows that the in vivo–generated domM/sprP/domC hybrid is significantly smaller than the dom parental species and similar to the smaller spr species (Fig. 4). As noted previously, the sprM/domP/hybridC true hybrid is significantly larger than either parental species (Fig. 4). The greatest difference in fat and lean mass is between the reciprocal hybrids with the domM/sprP/domC hybrid more closely resembling its maternal dom parent and the sprM/domP/hybridC cytoplasmic hybrid resembling the spr maternal parent (Fig. 4). Our true hybrids, with overgrowth, increased fat mass, and decreased lean mass, partially resemble maternal Eed gene early embryo depletion animals, which reflect epigenetic abnormalities in the Polycomb group 2 complex (37), although the growth differences in the Eed mice are much more modest than those seen in our interspecies hybrids. If this or another epigenetic abnormality explains true hybrid overgrowth and increased adiposity is unknown.

Fig. 4. sprM/domP/hybridC true hybrids showing overgrowth have increased fat mass and decreased lean mass.

Body weight, fat mass, and lean mass for the representative animals from B6 Mus domesticus and Mus spretus controls. Traditional hybrids are animals generated by in vivo matings of Mus domesticus females to Mus spretus males. True hybrids are sprM/domP/hybridC animals created by hemizygote fusion. The animals were not littermates. Group comparisons were ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

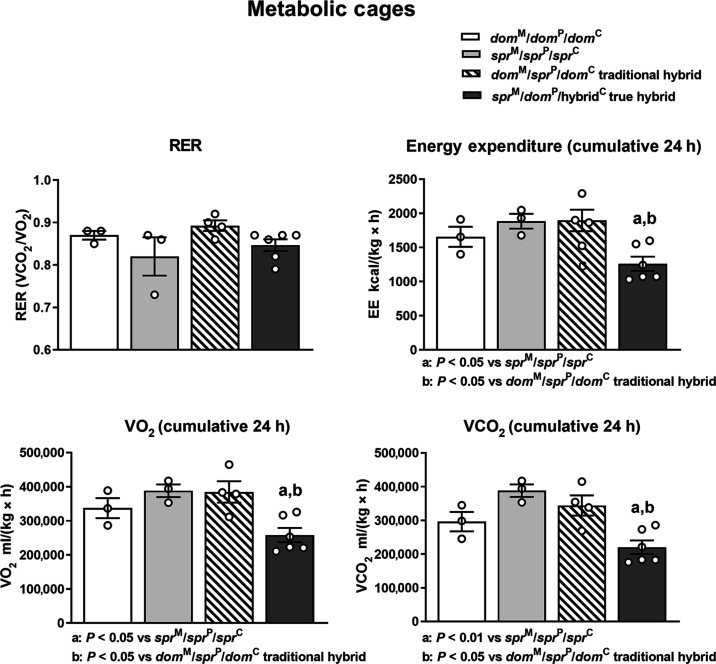

Respiratory measurements (Fig. 5) in metabolic cages revealed that the larger sprM/domP/hybridC true hybrids had lower energy expenditure, O2 consumption, and CO2 production. The RER (ratio of CO2 production to CO2 consumption) was not significantly different between true hybrids and the parental species. Thus, the true hybrids had significantly less energy expenditure than both the traditional hybrids and parental species.

Fig. 5. sprM/domP/hybridC true hybrids have decreased energy expenditure, VO2 consumption, and VCO2 production.

Metabolic measurements for the representative animals from B6 Mus domesticus and Mus spretus controls. Traditional hybrids are animals generated by in vivo matings of Mus domesticus females to Mus spretus males. True hybrids are sprM/domP/hybridC animals created by hemizygote fusion. The animals were not littermates. Group comparisons were analyzed by ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Open field tests showed the greatest difference in all three measurements (center, corner, and wall time) between the two parental species and both hybrids intermediate to the parental strains with the hybrids more closely resembling their respective paternal genome parents (fig. S3).

Placental phenotype

Placental abnormalities are present in rodent Peromyscus, Phodopus, and Mus interspecific hybrids (27, 29, 38–41). In our Mus hybrids, we observed the greatest placentomegaly in the sprM/domP/sprC hybrid group with less, but still substantial, placentomegaly in the true hybrid class (Table 2 and fig. S2). Histologically, we noted expansion and invasion of vertical columns of spongiotrophoblast and glycogen cells into the labyrinth zone (fig. S2), in agreement with an earlier description of these hybrids (38).

Sex ratio distortion and male sterility

Unexpectedly, we observed exclusively male progeny from our sprM/domP interspecies hybrids. Of the two stillborns and the single placenta that resulted from the transfer of a domP pronuclei into spr zygotes, sprM/domP/sprC all three were genotypically male. Of the seven true hybrids (sprM/domP/hybridC), again, all were male, and of the three sprM/domP/domC progeny that resulted from transfer of a single sprM pronucleus into a dom zygote, all three were male, leading to a total of 13 males and no females in these groups of sprM/domP hybrids (P < 0.005). This is in contrast to the in vivo–generated control traditional hybrid domM/sprP/domC offspring created by mating dom females to spr males where, of 32 offspring, 17 were female and 15 were male. Maternal dom pronucleus transfers performed in the F1 cytoplasm also resulted in equiproportional male and female progeny. Therefore, pronuclear transfer creating hybrid embryos after pronuclear residence in same species cytoplasm did not automatically result in sex ratio distortion (SRD). We only observed the SRD in sprM/domP hybrids where overgrowth was universal but viability depended on the cytoplasmic environment. This suggests that the SRD may result from female embryonic lethality as a part of a phenotypic spectrum with females having a more extreme lethal phenotype. Additional studies are needed to determine the cause and timing of lethality.

To determine male fertility, hybrid males were mated with females, and all were found to be sterile. No progeny were born from hybrid sprM/domP males. Matings were verified by copulation plug detection. Flushing uteri from mated females on the morning of plug detection never revealed sperm in the uterine lumen (no progeny after 10 or more vaginal plug-determined mating).

DISCUSSION

Cytonuclear incompatibilities in hybrids are problematic in that maternal cytoplasm and the maternal genome are inherited together in nature. We describe here an approach where the cytoplasm of the hybrid can be altered through microsurgical means. This allowed us to create true hybrid embryos with hybrid cytoplasm. We observed that such embryos were viable, whereas the same hybrid genome in maternal species–only cytoplasm was not. Our data strongly suggest that the presence of cytoplasm from the paternal species enhances hybrid development. We believe that enhanced development of true hybrids is due, in part, to more faithful reprogramming of the paternal genome in hybrid cytoplasm. The hybrid genome benefits from greater nuclear:cytoplasmic compatibility as well as the continued presence of self-replicating cytoplasmic elements. It will be of great interest to determine if our observations hold true in other interspecies hybrids where one of the reciprocal matings is similarly inviable, e.g., in Peromyscus (deer mice) and Phodopus (dwarf hamster) where matings result in opposite fetal/placental growth and viability outcomes with normal or small viable progeny in one hybrid and large embryonic lethal progeny in the other (27, 29), while, in Mus, small versus large placental growth phenotypes (39, 42) are observed. Genetic mapping in these three hybrids has been performed (26, 28, 29, 38, 43), and the X chromosome is the major source of hybrid placental/fetal growth abnormalities (26, 38, 40) in all three hybrid systems.

We sought to gain insight into Mus hybrids by observing the heretofore absent domM/sprP hybrid in different cytoplasms, i.e., spr, dom, and hybrid. Through the use of nuclear transfer, we could circumvent mating/fertilization barriers. We succeeded in creating the missing hybrid class initially by single pronuclear transfer where the dom male pronucleus is combined with a spr female pronucleus and cytoplasm but did not observe viability although the foreign paternal pronucleus spent a portion of the first cell cycle in same species cytoplasm. We observed near term but failed fetal development in the few conceptuses that developed to late term and very notable placentomegaly and increased fetal size, reminiscent of what was observed in Peromyscus and Phodopus hybrids. Relevant to our observations, Zechner et al. (38) described an exceptional single reciprocal cross sprM/domP fetus estimated to be at e17 of gestation that had placentomegaly (0.85 g), comparable to the 0.92 g placental size seen in our single pronucleus transfer sprM/domP conceptuses. Fetal size was said to be normal (38). Although it is almost impossible to obtain reciprocal cross (spr X mus) (38, 44), we report here the creation of several similar sprM/domP conceptuses and confirm the gross and comparable placentomegaly seen by these authors in their single conceptus. Our results differ in that all our conceptuses also had substantial fetal overgrowth. When the same hybrid sprM/domP genome is present in hybrid cytoplasm, decreased placentomegaly and viability are observed.

Given that hybrid cytoplasm in our true hybrids from the two species promotes growth and viability, we asked if the cytoplasm from F1 females would demonstrate a similar growth promoting effect. It did not. We interpret this result to suggest that the increased growth in sprM/domP conceptuses originates from an interaction of the dom paternal genome and spr cytoplasmic elements that are not nuclear encoded or, if they are, they are expressed uniparentally. It is important here to draw a distinction between “hybrid cytoplasm,” which results from fusion of two hemizygotes, versus the F1 cytoplasm derived from an F1 oocyte. The former has self-replicating elements from both species, whereas the F1 cytoplasm has only the matrilineal grandparental self-replicating elements. In addition, multimeric protein complexes and lattices may share a hybrid assembly in the F1 cytoplasm whereas assembly will be species-specific in hybrid cytoplasm. We note that, in Peromyscus (45) and Phodopus (40) pairing, the nuclear genome of one species with the mitochondria of the second species did not recreate the abnormal hybrid growth and viability phenotype.

Interspecies hybrids also offer a window into speciation and evolution (34). Over time, a number of hypotheses and predictions have arisen regarding the genetics and phenotypic characteristics of interspecies hybrids. One of the earlier observations of interspecies hybrids was codified by J. B. S. Haldane (46), which, with relatively few exceptions, states that the heterogametic sex is at a disadvantage compared to the homogametic sex, irrespective of which sex is male versus female in a given species. Interspecies crosses have been the mainstay for understanding the genetics of speciation, starting with the pioneering work of Dobzhansky, Muller, and Bates (30–34). However, genes do not exist in isolation, and an understanding of how a genome interacts with another species genome as well as its cytoplasm to ensure appropriate epigenetic gene reprogramming and interaction of genes with maternally inherited self-replicating cytoplasmic elements is critical, and the evolution of nuclear gene evolution has to be interpreted alongside cytoplasmic evolution.

Epigenetic changes in hybrids

Our understanding of epigenetic modification of imprinted genes has undergone rapid advancement in recent years. Rather than just a germline reset of cytosine methylation, more recent studies reveal modification, maintenance, and protection of genetic imprints as an ongoing dynamic process that continues after fertilization that requires maternal effect gene families involved in imprint gene protection and modification, e.g., the nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat containing (NLR) family and other maternal effect genes, that reside in the cytoplasmic subcortical maternal complex (SCMC) (47, 48). Some genes, e.g., NLRP7, MEI1, C11ORF80, and KHDC3L, lead to a recurrent biparental hydatidiform mole (49–54) where the embryo develops like an androgenone despite its biparental origin. Maternal effect SCMC genes also cause multilocus imprinting disorders. SCMC defects are critically important in early development as many stored RNAs of nuclear origin are present and organized in the cytoplasm and SCMC defects can perturb cytoplasmic elements such as the meiotic and mitotic spindle position and mitochondrial distribution (55). Cytoplasmically stored maternal gene products, therefore, despite their original nuclear origin, are transferrable with oocyte/early embryo cytoplasm. Oocyte stored SETD2 plays a critical role in DNA methylation and histone tail modification needed for maternal imprints with oocyte deficient in SETD2 arresting at the one-cell stage and preimplantation deficiency causing early postimplantation lethality (56). One-cell arrest can be circumvented with wild-type cytoplasm, but later postimplantation arrest cannot.

Among the possible epigenetic alterations in hybrids, genetic imprinting has attracted much attention as imprinted genes are expressed uniparentally and therefore could explain Darwin’s corollary to Haldane’s rule in reciprocal hybrids. First described as the reason why the Thp deletion, which contains the Igf2r imprinted domain (57), causes maternal only lethality (58) and as the cause of gynogenone and androgenone embryo lethality (58–60) imprinting is well situated to provide a rapid evolution of reproductive isolation and speciation either by canonical or noncanonical (61–63) imprinting. Canonical imprinting originates from gametogenic differentially methylated regions, leading to monoallelic gene expression in the subsequent generation, while a second noncanonical form involves Polycomb repressive complex regulation with monoubiquitination of histone H2A at Lys119 and histone H3 trimethylation at Lys27 in oocytes and early preimplantation embryos (61, 63) with subsequent differential methylation at some allele postimplantation (62).

Nonrandom paternal X chromosome inactivation [imprinted X chromosome inactivation (iXCI)] is observed in the somatic and extraembryonic cell lineage in marsupials (64), the extraembryonic lineage in rodents (65), but not in humans (66). Most noncanonical gene imprints specific to the placenta are not shared between species, e.g., mice and human (67–69), and data show that the human placenta exhibits extensive polymorphic imprinting (68, 70). Unlike canonical differentially methylated regions wherein differential methylation exists at imprinting centers, noncanonical imprinting with histone tail modifications have emerged as important components of imprinted gene and iXCI regulation (63, 71).

Altered epigenesis in nuclear gene reprogramming and imprinted gene expression, in hybrids, is likely to result from species-specific epigenetic gene regulation (72). Tilghman and colleagues suggested and demonstrated a loss of imprinting (LOI) in Peromyscus hybrids as a mechanism for growth and viability disturbances (26, 27). Investigations in other species e.g., Mus (73, 74), and Equus (75), Phodopus (28, 29), and Bovis (76), have revealed imprinted gene changes in hybrids. More recently, RNA transcription in dom X spr hybrids was investigated and revealed differentially expressed genes, including some imprinted genes, e.g., in the Kcnq1 imprinting cluster, in hybrids (44). Given the totality of the work examining a variable number of imprinted genes, some of which exhibit LOI but not necessarily altered expression in the proper direction to explain increased versus decreased growth and the absence of any direct evidence demonstrating causality, the role of imprinted genes in Darwin’s corollary to Haldane’s rule remains speculative, and a consensus has not emerged as to whether these changes truly explain Darwin’s corollary and reciprocal altered growth and viability hybrid phenotypes (77). Therefore, the role of imprinted gene deregulation in hybrid phenotype remains uncertain. Further work investigating epigenetic changes in traditional, nuclear transfer, and true hybrids is therefore warranted.

Placental changes in hybrids

The importance of the placenta in hybrid development is consistently acknowledged due to its central role in embryonic growth and development. The fact that the rescue effect of hybrid cytoplasm seems to be related to the placenta specific might suggest that a distinct set of incompatibilities underlie placental and embryonic/postnatal overgrowth. Recent studies have revealed many instances of monoallelic placental transcription in different species (61, 67, 70, 78–87). Failure to reprogram the imprinted genes Slc38a4, Sfmbt2, Jade1, Gab1, and Smoc1 (88–93), the Sfmbt2 gene miRNA cluster (89, 90), and the imprinted X chromosome (88, 91, 92) results in abnormal placentomegaly, spongiotrophoblast overgrowth, and large offspring syndrome of cloned SCNT mouse embryos. Removal of the histone mark H3K9me3 improves cloning efficiency (94). If histone modifications, gene and miRNA expression, and X chromosome inactivation are more normal in our true hybrids would be of interest.

Endogenous retroviruses in hybrids

Endogenous retrovirus (ERV) mobilization and altered expression have been seen in interspecies hybrids (41, 95). Evolutionary divergence could lead to increasing accumulation of species-specific ERV insertions. ERV elements were found to play an outsize role in the transcriptome of the oocyte and early embryo (96) and can lead to maternal allele gene repression in the early embryo and extraembryonic tissues (63, 84, 97, 98). ERV mobilization, integration, and alteration of the oocyte/embryo transcriptome could therefore serve as a reservoir of transcriptional variation and the development of different DMIs between species (72). A comparison of ERV-driven transcription between our Mus species and in our true hybrids is therefore of interest.

Sex ratio distortion

An unexpected observation in our investigation was the absence of female progeny in our sprM/domP hybrid embryos. We presume that the selective loss of female embryos occurred in early to mid-gestation because C-section of foster females did not yield many notable late gestation embryos or resorptions. Of interest is that a normal sex ratio at birth was seen in dwarf hamster Phodopus hybrids followed by fewer females later in life due to selective postnatal loss of females (29).

Further exploration of the SRD we describe here in Mus hybrids is warranted. The absence of female true hybrids is very notable, and the idea that some type of interaction between the paternal genome and hybrid cytoplasm causes failed X chromosome inactivation and early lethality in XX hybrids is certainly worth following up on. Precedent for selective loss of female embryos exists with mutations in the Polycomb group subunit proteins PCGF3 and PCGF5, (99) and the Smchd1 gene (100, 101), the latter important for gene imprint maintenance (102) resulting in failed X chromosome inactivation, failed trophoblast differentiation, and failed female embryogenesis. Also notable, knockout of the X-linked miR-465 cluster leads to a loss of female embryos and a distorted male:female ratio at birth (103). miR-465 regulates the placental Alkbh1 gene on chr 12, critical for trophoblast and spongiotrophoblast differentiation in the placenta. Knockout of Alkbh1 also leads to preferential female embryonic lethality (104).

Summary

Incompatibilities in interspecies hybrids are most often interpreted as negative epistatic interactions between nuclear genes (nuclear DMI), and less attention has been given to nuclear:cytoplasmic incompatibilities (cytonuclear DMI) (Fig. 6). Here, we describe a method where the presence of cytoplasm from both species can be present in a single interspecies hybrid. Our results revealed the ability of partial same species cytoplasm to restore viability to a previously unviable hybrid class. Of future interest is which element(s) present in the cytoplasm is/are responsible for this hybrid rescue. Both nuclear genome–encoded cytoplasmic stored products and independent self-replicating cytoplasmic elements are candidates. However, the lack of mechanistic studies to understand the molecular mechanism(s) leading to the observed change in survival of the hybrids and the low number of pups analyzed for the metabolic tests are the limitations of the study. Now that true hybrid creation has been realized and broadly characterized, future studies should perform molecular analysis of the hybrid genome to assess epigenetic modifications and the transcriptome in different cytoplasmic environments. Further experiments on endogenous retrovirus expression and the regulatory roles for mitochondria, SCMC, or stored maternal RNA are also potentially of great importance for the significance of this work. Such experiments should enhance our understanding of paternal genome reprogramming and speciation.

Fig. 6. Graphical representation of a true hybrid showing hybrid cytoplasm from two species.

Both nuclear and cytonuclear origin of DMIs are represented. SCMC, subcortical maternal complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Inbred Mus domesticus (C57BL/6J, stock no. 000664) and Mus spretus (Spret/EiJ, stock no. 001146) mice were obtained from JAX.org (Bar Harbor, ME). They were housed and maintained according to the regulations of the Yale Animal Resources Center following the recommendations of the Yale Institutional Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol no. 2017-20164). Outbred CD-1 vasectomized males and females were purchased from Charles River (Worcester, MA). All animals were provided with a nestlet material. Spretus animals were additionally given igloos and shredded paper to promote nesting behavior. Compared with the dom species, spr animals are hyperactive and exhibit increased perinatal mortality and poor reproduction. Females from each species were ovulated with 2.5 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) and human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) given 48 hours apart. Females were caged with same species males after HCG injection. Vaginal plugs were used to determine successful matings and one-cell stage embryos isolated (105). Microsurgery was performed starting at 20 hours after HCG (8 to 12 hours after the estimated time of fertilization) when zygotes were at the PN3 stage (106). When possible, two dom cell embryos were transferred to the contralateral oviduct of pseudopregnant females as a control. dom progenies have a black coat color, while spr and hybrid animals are agouti.

Microsurgery

Before surgery, embryos were incubated for 15 min in potassium simplex optimized medium (KSOM) (107) supplemented with cytoskeletal inhibitors cytochalasin B and demecolcine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, United States) at 37°C in 5% CO2, 5% O2, and 90% N2 (35). Microsurgery was performed using straight microinstruments in a microsurgery chamber. Microinstruments were fashioned as previously described (35, 105) using a Brown-Flaming horizontal pipette puller, a Narishige grinding wheel, and a de Fonbrune microforge. Microsurgery was performed in microdrops of KSOM medium supplemented with cytoskeletal inhibitors in 50-cS viscosity polysiloxane oil (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States)–filled microsurgery chamber using Leitz micromanipulators and a Nikon fixed stage microscope equipped with Nomarski optics.

One species retained its ZP, and the second species underwent zona removal with an acidic Tyrode’s solution with polyvinyl pyrrolidone (105) prior to microsurgery. Two hemizygotes, one from each species, each with one pronucleus and approximately ½ volume zygote cytoplasm (estimated through the use of an ocular micrometer), were fused within a ZP to create the nuclear and cytoplasmic hybrids.

Fusion of karyoplasts and hemiygotes was achieved with Sendai CF EX HVJ Envelope (HVJ-E) protein purchased from GenomOne (Osaka, Japan). Envelope protein was diluted according to the manufacturer’s specifications and stored in 10-μl aliquots at −80°C. On thawing, the envelope protein was diluted 1:20 with KSOM and lightly vortexed before creating a protein suspension microdrop in the microsurgery chamber.

Embryo transfer

Two cell embryos were transferred to e0.5 CD-1 pseudopregnant females mated to CD-1 vasectomized males (105). Five to eight embryos were transferred to the oviduct either unilaterally or bilaterally (one incision of the dorsal midline) after general anesthesia. When practical, control embryos from natural matings were flushed out and transferred to e0.5 CD-1 pseudopregnant females to correct for uterine and maternal influences of CD-1 strain pseudopregnancy on growth and development because all manipulated hybrids of necessity gestated in pseudopregnant females. After surgery, the recipient CD-1 pseudopregnant females were recovered on a warming plate at 37°C and kept under observation until they regained full consciousness and locomotor activities. C-sections were performed at e18.5. The pups were placed with a few of the original pups of foster CD1 mothers, keeping the litter size between 6 and 10, depending on how many pups were retrieved.

Metabolism and body composition measurements

Indirect calorimetry was performed using an open-circuit, indirect calorimetry system (PhenoMaster, TSE Systems) as previously described (108, 109). In brief, mice nonlittermates were trained for 3 days before data acquisition to adapt to the food/drink dispenser of the PhenoMaster system. Afterward, mice were placed in regular type II cages with sealed lids at room temperature (22°C) and allowed to adapt to the chambers for at least 48 hours. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All parameters were measured continuously and simultaneously. Body composition, lean mass, and fat mass were analyzed with EchoMRI (EchoMRI LLC, United States).

Open field test

The open field test apparatus was a square, polyurethane arena (36.5 cm × 36.5 cm × 30 cm, Plexiglas). The animal was placed in the lower left corner of the apparatus. Time spent in the three areas (walls, center, and corners) was recorded for 30 min. Behavioral testing took place from 10 a.m. to 14 p.m. The apparatus was cleaned with 10% ethanol after each animal exposure. The ANY-Maze Software (Stoelting Company, Wood Dale, IL) was used to record and analyze behavioral data.

Genotyping of sprM/domP/hybridC true hybrids

DNA was isolated with a QIAGEN DNeasy kit. Before sequencing PCR product was purified with a QIAGEN PCR Cleanup kit. A 245-bp amplicon of the Sry gene was PCR amplified using primers CTG GGA TGC AGG TGG AAA AG (F) and GCT CTA CTC CAG TCT TGC CT (R) and sequenced at the Yale Keck sequencing facility. There were three SNPs between dom and spr DNA that differentiated the species origin of the paternal genome.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the GraphPad Prism 10 package. The normality of the data was checked with the Shapiro-Wilk test, and because the data were normally distributed, group comparisons were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Bonferroni test for weight measurements, and Tukey’s multiple comparison test for metabolism and body composition measurements, and for open field analysis as post hoc tests. The association between categorical data was assessed by the chi-square test for the viability of hybrids and controls and the in vivo fertilization rate of F1 oocytes. All data are presented as means ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to the memory of J.M., who passed away on 25 March 2024. J.M. was an outstanding physician-scientist whose pioneering work in the 1980s (59) provided crucial evidence for the mechanism of genetic imprinting, and his genetic counseling offered help for countless children and their families.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grants HDO72532-02 to J.M. and DKO98058, DK126447, AG067329, AG051459, and AG082190 to T.L.H.) and funds from the Department of Comparative Medicine, Yale School of Medicine.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: J.M., L.S., and T.L.H. Methodology: J.M., L.S., and L.V. Investigation: J.M., L.S., L.V., and T.L.H. Supervision: J.M. Writing—original draft: J.M. and L.S. Writing—review and editing: J.M., L.S., and T.L.H.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

The PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S3

Table S1

Legends for movies s1 to s3

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 to S3

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Abe K.-I., Funaya S., Tsukioka D., Kawamura M., Suzuki Y., Suzuki M. G., Schultz R. M., Aoki F., Minor zygotic gene activation is essential for mouse preimplantation development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E6780–E6788 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inoue A., Ogushi S., Saitou M., Suzuki M. G., Aoki F., Involvement of mouse nucleoplasmin 2 in the decondensation of sperm chromatin after fertilization. Biol. Reprod. 85, 70–77 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gou L. T., Lim D. H., Ma W., Aubol B. E., Hao Y., Wang X., Zhao J., Liang Z., Shao C., Zhang X., Meng F., Li H., Zhang X., Xu R., Li D., Rosenfeld M. G., Mellon P. L., Adams J. A., Liu M. F., Fu X. D., Initiation of parental genome reprogramming in fertilized oocyte by splicing kinase SRPK1-catalyzed protamine phosphorylation. Cell 180, 1212–1227.e14 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer W., Niveleau A., Walter J., Fundele R., Haaf T., Demethylation of the zygotic paternal genome. Nature 403, 501–502 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oswald J., Engemann S., Lane N., Mayer W., Olek A., Fundele R., Dean W., Reik W., Walter J., Active demethylation of the paternal genome in the mouse zygote. Curr. Biol. 10, 475–478 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talbert P. B., Henikoff S., Histone variants—Ancient wrap artists of the epigenome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 264–275 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elsaesser S. J., Goldberg A. D., Allis C. D., New functions for an old variant: No substitute for histone H3.3. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 20, 110–117 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo S.-M., Liu X.-P., Zhou L.-Q., H3.3 kinetics predicts chromatin compaction status of parental genomes in early embryos. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 19, 87 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loppin B., Bonnefoy E., Anselme C., Laurencon A., Karr T. L., Couble P., The histone H3.3 chaperone HIRA is essential for chromatin assembly in the male pronucleus. Nature 437, 1386–1390 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nonchev S., Tsanev R., Protamine-histone replacement and DNA replication in the male mouse pronucleus. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 25, 72–76 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C., Chen C., Liu X., Li C., Wu Q., Chen X., Yang L., Kou X., Zhao Y., Wang H., Gao Y., Zhang Y., Gao S., Dynamic nucleosome organization after fertilization reveals regulatory factors for mouse zygotic genome activation. Cell Res. 32, 801–813 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue A., Zhang Y., Nucleosome assembly is required for nuclear pore complex assembly in mouse zygotes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 609–616 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreu-Vieyra C. V., Chen R., Agno J. E., Glaser S., Anastassiadis K., Stewart A. F., Matzuk M. M., MLL2 is required in oocytes for bulk histone 3 lysine 4 trimethylation and transcriptional silencing. PLOS Biol. 8, e1000453 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ancelin K., Syx L., Borensztein M., Ranisavljevic N., Vassilev I., Briseno-Roa L., Liu T., Metzger E., Servant N., Barillot E., Chen C. J., Schule R., Heard E., Maternal LSD1/KDM1A is an essential regulator of chromatin and transcription landscapes during zygotic genome activation. eLife 5, e08851 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amarnath D., Choi I., Moawad A. R., Wakayama T., Campbell K. H., Nuclear-cytoplasmic incompatibility and inefficient development of pig-mouse cytoplasmic hybrid embryos. Reproduction 142, 295–307 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuo Y., Gao Y., Su G., Bai C., Wei Z., Liu K., Li Q., Bou S., Li G., Irregular transcriptome reprogramming probably causes thec developmental failure of embryos produced by interspecies somatic cell nuclear transfer between the Przewalski’s gazelle and the bovine. BMC Genomics 15, 1113 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung Y., Bishop C. E., Treff N. R., Walker S. J., Sandler V. M., Becker S., Klimanskaya I., Wun W. S., Dunn R., Hall R. M., Su J., Lu S. J., Maserati M., Choi Y. H., Scott R., Atala A., Dittman R., Lanza R., Reprogramming of human somatic cells using human and animal oocytes. Cloning Stem Cells 11, 213–223 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang K., Beyhan Z., Rodriguez R. M., Ross P. J., Iager A. E., Kaiser G. G., Chen Y., Cibelli J. B., Bovine ooplasm partially remodels primate somatic nuclei following somatic cell nuclear transfer. Cloning Stem Cells 11, 187–202 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beyhan Z., Iager A. E., Cibelli J. B., Interspecies nuclear transfer: Implications for embryonic stem cell biology. Cell Stem Cell 1, 502–512 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanza R. P., Cibelli J. B., Diaz F., Moraes C. T., Farin P. W., Farin C. E., Hammer C. J., West M. D., Damiani P., Cloning of an endangered species (Bos gaurus) using interspecies nuclear transfer. Cloning 2, 79–90 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White K. L., Bunch T. D., Mitalipov S., Reed W. A., Establishment of pregnancy after the transfer of nuclear transfer embryos produced from the fusion of argali (Ovis ammon) nuclei into domestic sheep (Ovis aries) enucleated oocytes. Cloning 1, 47–54 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loi P., Ptak G., Barboni B., Fulka J. Jr., Cappai P., Clinton M., Genetic rescue of an endangered mammal by cross-species nuclear transfer using post-mortem somatic cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 962–964 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turelli M., Moyle L. C., Asymmetric postmating isolation: Darwin’s corollary to Haldane’s rule. Genetics 176, 1059–1088 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dawson W. D., Fertility and size inheritance in a peromyscus species cross. Evolution 19, 44–55 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers J. F., Dawson W. D., Foetal and placental size in a Peromyscus species cross. J. Reprod. Fertil. 21, 255–262 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vrana P. B., Fossella J. A., Matteson P., del Rio T., O’Neill M. J., Tilghman S. M., Genetic and epigenetic incompatibilities underlie hybrid dysgenesis in Peromyscus. Nat. Genet. 25, 120–124 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vrana P. B., Guan X. J., Ingram R. S., Tilghman S. M., Genomic imprinting is disrupted in interspecific Peromyscus hybrids. Nat. Genet. 20, 362–365 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brekke T. D., Henry L. A., Good J. M., Genomic imprinting, disrupted placental expression, and speciation. Evolution 70, 2690–2703 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brekke T. D., Good J. M., Parent-of-origin growth effects and the evolution of hybrid inviability in dwarf hamsters. Evolution 68, 3134–3148 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.W. Bateson, “Heredity and variation in modern lights” in Darwin and Modern Science, A. C. Seward, Ed. (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1909), pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- 31.T. G. Dobzhansky, Genetics and the Origin of Species (Columbia Univ. Press, 1937). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller H. J., Isolating mechanisms, evolution, and temperature. Biol. Symp. 6, 71–125 (1942). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orr H. A., Dobzhansky, Bateson, and the genetics of speciation. Genetics 144, 1331–1335 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.J. A. Coyne, H. A. Orr, Speciation (Sinauer, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGrath J., Solter D., Nuclear transplantation in the mouse embryo by microsurgery and cell fusion. Science 220, 1300–1302 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tschop M. H., Speakman J. R., Arch J. R., Auwerx J., Bruning J. C., Chan L., Eckel R. H., Farese R. V. Jr., Galgani J. E., Hambly C., Herman M. A., Horvath T. L., Kahn B. B., Kozma S. C., Maratos-Flier E., Muller T. D., Munzberg H., Pfluger P. T., Plum L., Reitman M. L., Rahmouni K., Shulman G. I., Thomas G., Kahn C. R., Ravussin E., A guide to analysis of mouse energy metabolism. Nat. Methods 9, 57–63 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prokopuk L., Stringer J. M., White C. R., Vossen R., White S. J., Cohen A. S. A., Gibson W. T., Western P. S., Loss of maternal EED results in postnatal overgrowth. Clin. Epigenetics 10, 95 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zechner U., Reule M., Orth A., Bonhomme F., Strack B., Guenet J.-L., Hameister H., Fundele R., An X-chromosome linked locus contributes to abnormal placental development in mouse interspecific hybrid. Nat. Genet. 12, 398–403 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurz H., Zechner U., Orth A., Fundele R., Lack of correlation between placenta and offspring size in mouse interspecific crosses. Anat. Embryol. 200, 335–343 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brekke T. D., Moore E. C., Campbell-Staton S. C., Callahan C. M., Cheviron Z. A., Good J. M., X chromosome-dependent disruption of placental regulatory networks in hybrid dwarf hamsters. Genetics 218, iyab043 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown J. D., Piccuillo V., O’Neill R. J., Retroelement demethylation associated with abnormal placentation in Mus musculus x Mus caroli hybrids. Biol. Reprod. 86, 88 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zechner U., Shi W., Hemberger M., Himmelbauer H., Otto S., Orth A., Kalscheuer V., Fischer U., Elango R., Reis A., Vogel W., Ropers H., Ruschendorf F., Fundele R., Divergent genetic and epigenetic post-zygotic isolation mechanisms in Mus and Peromyscus. J. Evol. Biol. 17, 453–460 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hemberger M. C., Pearsall R. S., Zechner U., Orth A., Otto S., Ruschendorf F., Fundele R., Elliott R., Genetic dissection of X-linked interspecific hybrid placental dysplasia in congenic mouse strains. Genetics 153, 383–390 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arevalo L., Gardner S., Campbell P., Haldane’s rule in the placenta: Sex-biased misregulation of the Kcnq1 imprinting cluster in hybrid mice. Evolution 75, 86–100 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dawson W. D., Sagedy M. N., En-yu L., Kass D. H., Crossland J. P., Growth regulation in Peromyscus species hybrids: A test for mitochondrial-nuclear genomic interaction. Growth Dev. Aging 57, 121–133 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haldane J. B. S., Sex ratio and unisexual sterility in hybrid animals. Journal of Genetics 12, 101–109 (1922). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Begemann M., Rezwan F. I., Beygo J., Docherty L. E., Kolarova J., Schroeder C., Buiting K., Chokkalingam K., Degenhardt F., Wakeling E. L., Kleinle S., Gonzalez Fassrainer D., Oehl-Jaschkowitz B., Turner C. L. S., Patalan M., Gizewska M., Binder G., Ngoc C. T. B., Dung V. C., Mehta S. G., Baynam G., Hamilton-Shield J. P., Aljareh S., Lokulo-Sodipe O., Horton R., Siebert R., Elbracht M., Temple I. K., Eggermann T., Mackay D. J. G., Maternal variants in NLRP and other maternal effect proteins are associated with multilocus imprinting disturbance in offspring. J. Med. Genet. 55, 497–504 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elbracht M., Mackay D., Begemann M., Kagan K. O., Eggermann T., Disturbed genomic imprinting and its relevance for human reproduction: Causes and clinical consequences. Hum. Reprod. Update 26, 197–213 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moglabey Y. B., Kircheisen R., Seoud M., El Mogharbel N., Van den Veyver I., Slim R., Genetic mapping of a maternal locus responsible for familial hydatidiform moles. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 667–671 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van den Veyver I. B., Al-Hussaini T. K., Biparental hydatidiform moles: A maternal effect mutation affecting imprinting in the offspring. Hum. Reprod. Update 12, 233–242 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murdoch S., Djuric U., Mazhar B., Seoud M., Khan R., Kuick R., Bagga R., Kircheisen R., Ao A., Ratti B., Hanash S., Rouleau G. A., Slim R., Mutations in NALP7 cause recurrent hydatidiform moles and reproductive wastage in humans. Nat. Genet. 38, 300–302 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen N. M., Zhang L., Reddy R., Dery C., Arseneau J., Cheung A., Surti U., Hoffner L., Seoud M., Zaatari G., Bagga R., Srinivasan R., Coullin P., Ao A., Slim R., Comprehensive genotype-phenotype correlations between NLRP7 mutations and the balance between embryonic tissue differentiation and trophoblastic proliferation. J. Med. Genet. 51, 623–634 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nguyen N. M. P., Ge Z. J., Reddy R., Fahiminiya S., Sauthier P., Bagga R., Sahin F. I., Mahadevan S., Osmond M., Breguet M., Rahimi K., Lapensee L., Hovanes K., Srinivasan R., Van den Veyver I. B., Sahoo T., Ao A., Majewski J., Taketo T., Slim R., Causative mutations and mechanism of androgenetic hydatidiform moles. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 103, 740–751 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parry D. A., Logan C. V., Hayward B. E., Shires M., Landolsi H., Diggle C., Carr I., Rittore C., Touitou I., Philibert L., Fisher R. A., Fallahian M., Huntriss J. D., Picton H. M., Malik S., Taylor G. R., Johnson C. A., Bonthron D. T., Sheridan E. G., Mutations causing familial biparental hydatidiform mole implicate c6orf221 as a possible regulator of genomic imprinting in the human oocyte. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 451–458 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bebbere D., Albertini D. F., Coticchio G., Borini A., Ledda S., The subcortical maternal complex: Emerging roles and novel perspectives. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 27, gaab043 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu Q., Xiang Y., Wang Q., Wang L., Brind’Amour J., Bogutz A. B., Zhang Y., Zhang B., Yu G., Xia W., Du Z., Huang C., Ma J., Zheng H., Li Y., Liu C., Walker C. L., Jonasch E., Lefebvre L., Wu M., Lorincz M. C., Li W., Li L., Xie W., SETD2 regulates the maternal epigenome, genomic imprinting and embryonic development. Nat. Genet. 51, 844–856 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barlow D. P., Stoger R., Herrmann B. G., Saito K., Schweifer N., The mouse insulin-like growth factor type-2 receptor is imprinted and closely linked to the Tme locus. Nature 349, 84–87 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McGrath J., Solter D., Maternal Thp lethality in the mouse is a nuclear, not cytoplasmic, defect. Nature 308, 550–551 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGrath J., Solter D., Completion of mouse embryogenesis requires both the maternal and paternal genomes. Cell 37, 179–183 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Surani M. A. H., Barton S. C., Norris M. L., Development of reconstituted mouse eggs suggests imprinting of the genome during gametogenesis. Nature 308, 548–550 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang W., Chen Z., Yin Q., Zhang D., Racowsky C., Zhang Y., Maternal-biased H3K27me3 correlates with paternal-specific gene expression in the human morula. Genes Dev. 33, 382–387 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen Z., Yin Q., Inoue A., Zhang C., Zhang Y., Allelic H3K27me3 to allelic DNA methylation switch maintains noncanonical imprinting in extraembryonic cells. Sci. Adv. 5, eaay7246 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Inoue A., Jiang L., Lu F., Suzuki T., Zhang Y., Maternal H3K27me3 controls DNA methylation-independent imprinting. Nature 547, 419–424 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cooper D. W., VandeBerg J. L., Sharman G. B., Poole W. E., Phosphoglycerate kinase polymorphism in kangaroos provides further evidence for paternal X inactivation. Nat. New Biol. 230, 155–157 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takagi N., Sasaki M., Preferential inactivation of the paternally derived X chromosome in the extraembryonic membranes of the mouse. Nature 256, 640–642 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moreira de Mello J. C., de Araujo E. S., Stabellini R., Fraga A. M., de Souza J. E., Sumita D. R., Camargo A. A., Pereira L. V., Random X inactivation and extensive mosaicism in human placenta revealed by analysis of allele-specific gene expression along the X chromosome. PLOS ONE 5, e10947 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frost J. M., Moore G. E., The importance of imprinting in the human placenta. PLOS Genet. 6, e1001015 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hanna C. W., Penaherrera M. S., Saadeh H., Andrews S., McFadden D. E., Kelsey G., Robinson W. P., Pervasive polymorphic imprinted methylation in the human placenta. Genome Res. 26, 756–767 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okae H., Matoba S., Nagashima T., Mizutani E., Inoue K., Ogonuki N., Chiba H., Funayama R., Tanaka S., Yaegashi N., Nakayama K., Sasaki H., Ogura A., Arima T., RNA sequencing-based identification of aberrant imprinting in cloned mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 992–1001 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sanchez-Delgado M., Court F., Vidal E., Medrano J., Monteagudo-Sanchez A., Martin-Trujillo A., Tayama C., Iglesias-Platas I., Kondova I., Bontrop R., Poo-Llanillo M. E., Marques-Bonet T., Nakabayashi K., Simon C., Monk D., Human oocyte-derived methylation differences persist in the placenta revealing widespread transient imprinting. PLOS Genet. 12, e1006427 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Inoue A., Jiang L., Lu F., Zhang Y., Genomic imprinting of Xist by maternal H3K27me3. Genes Dev. 31, 1927–1932 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brind’Amour J., Kobayashi H., Richard Albert J., Shirane K., Sakashita A., Kamio A., Bogutz A., Koike T., Karimi M. M., Lefebvre L., Kono T., Lorincz M. C., LTR retrotransposons transcribed in oocytes drive species-specific and heritable changes in DNA methylation. Nat. Commun. 9, 3331 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shi W., Lefebvre L., Yu Y., Otto S., Krella A., Orth A., Fundele R., Loss-of-imprinting of Peg1 in mouse interspecies hybrids is correlated with altered growth. Genesis 39, 65–72 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shi W., Krella A., Orth A., Yu Y., Fundele R., Widespread disruption of genomic imprinting in adult interspecies mouse (Mus) hybrids. Genesis 43, 100–108 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang X., Miller D. C., Harman R., Antczak D. F., Clark A. G., Paternally expressed genes predominate in the placenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10705–10710 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen Z., Hagen D. E., Elsik C. G., Ji T., Morris C. J., Moon L. E., Rivera R. M., Characterization of global loss of imprinting in fetal overgrowth syndrome induced by assisted reproduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 4618–4623 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wolf J. B., Oakey R. J., Feil R., Imprinted gene expression in hybrids: Perturbed mechanisms and evolutionary implications. Heredity 113, 167–175 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Court F., Tayama C., Romanelli V., Martin-Trujillo A., Iglesias-Platas I., Okamura K., Sugahara N., Simon C., Moore H., Harness J. V., Keirstead H., Sanchez-Mut J. V., Kaneki E., Lapunzina P., Soejima H., Wake N., Esteller M., Ogata T., Hata K., Nakabayashi K., Monk D., Genome-wide parent-of-origin DNA methylation analysis reveals the intricacies of human imprinting and suggests a germline methylation-independent mechanism of establishment. Genome Res. 24, 554–569 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Okae H., Hiura H., Nishida Y., Funayama R., Tanaka S., Chiba H., Yaegashi N., Nakayama K., Sasaki H., Arima T., Re-investigation and RNA sequencing-based identification of genes with placenta-specific imprinted expression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 548–558 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Richard Albert J., Kobayashi T., Inoue A., Monteagudo-Sanchez A., Kumamoto S., Takashima T., Miura A., Oikawa M., Miura F., Takada S., Hirabayashi M., Korthauer K., Kurimoto K., Greenberg M. V. C., Lorincz M., Kobayashi H., Conservation and divergence of canonical and non-canonical imprinting in murids. Genome Biol. 24, 48 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kobayashi H., Canonical and non-canonical genomic imprinting in rodents. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 713878 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ishihara T., Griffith O. W., Suzuki S., Renfree M. B., Placental imprinting of SLC22A3 in the IGF2R imprinted domain is conserved in therian mammals. Epigenetics Chromatin 15, 32 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chuong E. B., Rumi M. A., Soares M. J., Baker J. C., Endogenous retroviruses function as species-specific enhancer elements in the placenta. Nat. Genet. 45, 325–329 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hamada H., Okae H., Toh H., Chiba H., Hiura H., Shirane K., Sato T., Suyama M., Yaegashi N., Sasaki H., Arima T., Allele-specific methylome and transcriptome analysis reveals widespread imprinting in the human placenta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 1045–1058 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Monk D., Arnaud P., Apostolidou S., Hills F. A., Kelsey G., Stanier P., Feil R., Moore G. E., Limited evolutionary conservation of imprinting in the human placenta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6623–6628 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barbaux S., Gascoin-Lachambre G., Buffat C., Monnier P., Mondon F., Tonanny M. B., Pinard A., Auer J., Bessieres B., Barlier A., Jacques S., Simeoni U., Dandolo L., Letourneur F., Jammes H., Vaiman D., A genome-wide approach reveals novel imprinted genes expressed in the human placenta. Epigenetics 7, 1079–1090 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cao W., Douglas K. C., Samollow P. B., VandeBerg J. L., Wang X., Clark A. G., Origin and evolution of marsupial-specific imprinting clusters through lineage-specific gene duplications and acquisition of promoter differential methylation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 40, msad022 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Inoue K., Kohda T., Sugimoto M., Sado T., Ogonuki N., Matoba S., Shiura H., Ikeda R., Mochida K., Fujii T., Sawai K., Otte A. P., Tian X. C., Yang X., Ishino F., Abe K., Ogura A., Impeding Xist expression from the active X chromosome improves mouse somatic cell nuclear transfer. Science 330, 496–499 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Inoue K., Hirose M., Inoue H., Hatanaka Y., Honda A., Hasegawa A., Mochida K., Ogura A., The rodent-specific MicroRNA cluster within the Sfmbt2 gene is imprinted and essential for placental development. Cell Rep. 19, 949–956 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Inoue K., Ogonuki N., Kamimura S., Inoue H., Matoba S., Hirose M., Honda A., Miura K., Hada M., Hasegawa A., Watanabe N., Dodo Y., Mochida K., Ogura A., Loss of H3K27me3 imprinting in the Sfmbt2 miRNA cluster causes enlargement of cloned mouse placentas. Nat. Commun. 11, 2150 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Matoba S., Inoue K., Kohda T., Sugimoto M., Mizutani E., Ogonuki N., Nakamura T., Abe K., Nakano T., Ishino F., Ogura A., RNAi-mediated knockdown of Xist can rescue the impaired postimplantation development of cloned mouse embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20621–20626 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Matoba S., Wang H., Jiang L., Lu F., Iwabuchi K. A., Wu X., Inoue K., Yang L., Press W., Lee J. T., Ogura A., Shen L., Zhang Y., Loss of H3K27me3 imprinting in somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos disrupts post-implantation development. Cell Stem Cell 23, 343–354.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang L. Y., Li Z. K., Wang L. B., Liu C., Sun X. H., Feng G. H., Wang J. Q., Li Y. F., Qiao L. Y., Nie H., Jiang L. Y., Sun H., Xie Y. L., Ma S. N., Wan H. F., Lu F. L., Li W., Zhou Q., Overcoming intrinsic H3K27me3 imprinting barriers improves post-implantation development after somatic cell nuclear transfer. Cell Stem Cell 27, 315–325.e5 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Matoba S., Liu Y., Lu F., Iwabuchi K. A., Shen L., Inoue A., Zhang Y., Embryonic development following somatic cell nuclear transfer impeded by persisting histone methylation. Cell 159, 884–895 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.O’Neill R. J., O’Neill M. J., Graves J. A., Undermethylation associated with retroelement activation and chromosome remodelling in an interspecific mammalian hybrid. Nature 393, 68–72 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Peaston A. E., Evsikov A. V., Graber J. H., de Vries W. N., Holbrook A. E., Solter D., Knowles B. B., Retrotransposons regulate host genes in mouse oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Dev. Cell 7, 597–606 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen Z., Djekidel M. N., Zhang Y., Distinct dynamics and functions of H2AK119ub1 and H3K27me3 in mouse preimplantation embryos. Nat. Genet. 53, 551–563 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mei H., Kozuka C., Hayashi R., Kumon M., Koseki H., Inoue A., H2AK119ub1 guides maternal inheritance and zygotic deposition of H3K27me3 in mouse embryos. Nat. Genet. 53, 539–550 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Almeida M., Pintacuda G., Masui O., Koseki Y., Gdula M., Cerase A., Brown D., Mould A., Innocent C., Nakayama M., Schermelleh L., Nesterova T. B., Koseki H., Brockdorff N., PCGF3/5-PRC1 initiates Polycomb recruitment in X chromosome inactivation. Science 356, 1081–1084 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Blewitt M. E., Vickaryous N. K., Hemley S. J., Ashe A., Bruxner T. J., Preis J. I., Arkell R., Whitelaw E., An N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea screen for genes involved in variegation in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7629–7634 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Blewitt M. E., Gendrel A. V., Pang Z., Sparrow D. B., Whitelaw N., Craig J. M., Apedaile A., Hilton D. J., Dunwoodie S. L., Brockdorff N., Kay G. F., Whitelaw E., SmcHD1, containing a structural-maintenance-of-chromosomes hinge domain, has a critical role in X inactivation. Nat. Genet. 40, 663–669 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wanigasuriya I., Gouil Q., Kinkel S. A., Tapia Del Fierro A., Beck T., Roper E. A., Breslin K., Stringer J., Hutt K., Lee H. J., Keniry A., Ritchie M. E., Blewitt M. E., Smchd1 is a maternal effect gene required for genomic imprinting. eLife 9, e55529 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang Z., Meng N., Wang Y., Zhou T., Li M., Wang S., Chen S., Zheng H., Kong S., Wang H., Yan W., Ablation of the miR-465 cluster causes a skewed sex ratio in mice. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 893854 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]