Abstract

Repeated electrical stimulation results in development of seizures and a permanent increase in seizure susceptibility (kindling). The permanence of kindling suggests that chronic changes in gene expression are involved. Kindling at different sites produces specific effects on interictal behaviors such as spatial cognition and anxiety, suggesting that causal changes in gene expression might be restricted to the stimulated site. We employed focused microarray analysis to characterize changes in gene expression associated with amygdaloid and hippocampal kindling. Male Long-Evans rats received 1 s trains of electrical stimulation to either the amygdala or hippocampus once daily until five generalized seizures had been kindled. Yoked control rats carried electrodes but were not stimulated. Rats were euthanized 14 days after the last seizures, both amygdala and hippocampus dissected, and transcriptome profiles compared. Of the 1,200 rat brain-associated genes evaluated, 39 genes exhibited statistically significant expression differences between the kindled and non-kindled amygdala and 106 genes exhibited statistically significant differences between the kindled and non-kindled hippocampus. In the amygdala, subsequent ontological analyses using the GOMiner algorithm demonstrated significant enrichment in categories related to cytoskeletal reorganization and cation transport, as well as in gene families related to synaptic transmission and neurogenesis. In the hippocampus, significant enrichment in gene expression within categories related to cytoskeletal reorganization and cation transport was similarly observed. Furthermore, unique to the hippocampus, enrichment in transcription factor activity and GTPase-mediated signal transduction was identified. Overall, these data identify specific and unique neurochemical pathways chronically altered following kindling in the two sites, and provide a platform for defining the molecular basis for the differential behaviors observed in the interictal period.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10571-011-9672-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Kindling, Microarray, Hippocampus, Amygdala, NMDA receptor

Introduction

The kindling of seizures (Goddard et al. 1969; Racine et al. 1972; Racine 1972a, b) is associated with a constellation of significant and widespread changes in electrophysiology, neuroanatomy, molecular markers, and function. For example, kindling results in large increases in excitatory synaptic drive in the forebrain (Racine et al. 1986), as well as increases in inhibitory transmission in the dentate gyrus (Tuff et al. 1983a, b; Bronzino et al. 1991a, b) but decreased inhibition in other areas such as field CA1 (Kamphuis et al. 1988) and amygdala (Schinnick-Gallagher and Bradley Keele 1998). Morphological changes in the brain accompany kindling, including sprouting of the mossy fibers, the axons of dentate granule cells, into the hilus and field CA3 (Sutula et al. 1998). As well as producing excitatory effects (Shao and Dudek 2005), sprouting of the mossy fibers results in increased inhibitory effects (Sloviter et al. 2006), thereby accounting for the increased inhibitory drive described in the dentate gyrus after kindling. At the ultrastructural level, Geinisman et al. (1988) have described an increase in the proportion of highly efficacious perforated synapses within the kindled hippocampus, and Henry et al. (2008) have described an increase in perforated synapses in the neocortex following neocortical kindling. Numerous changes in molecular markers for various neurotransmitters have been described after kindling (Corcoran and Moshé 1998, 2005). In particular, investigators have provided evidence that kindling is associated with decreased function of GABA in many areas of the brain (Loscher and Schwark 1987), consistent with the hypothesis that epileptogenesis is in part due to disinhibition. Other research suggests that kindling involves increased excitatory effects of glutamate, particularly at certain subunits of the NMDA receptor (Lieberman and Mody 1998; Schinnick-Gallagher and Bradley Keele 1998; Behr et al. 2001). In parallel, there is evidence that kindling involves increased release or decreased reuptake of glutamate (Jarvie et al. 1990). Collectively these data suggest that the balance between excitatory and inhibitory drive is altered (Corcoran and Teskey 2009), which might lead to increased network-maintained bursting.

Functionally, kindling to a limited number of generalized seizures is followed by significant behavioral changes that typically are found to be specific to the region stimulated and behavioral tasks required. For example, kindling of hippocampal field CA1 results in deficits in spatial cognition (Leung et al. 1990; Hannesson et al. 2001), but fails to affect anxiety-like behavior (Hannesson et al. 2001) or object discrimination (Hannesson et al. 2005). In contrast, kindling of the amygdala or perirhinal cortex produces increased anxiety-like behavior but has no effect on spatial cognition, whereas perirhinal but not amygdaloid kindling disrupts object recognition memory (Hannesson et al. 2001, 2005, 2008). We note that although changes in affective behavior have been described after hippocampal kindling (Kalynchuk et al. 1998) and spatial deficits have been described after kindling of the amygdala (Beldhuis et al. 1992), these typically are associated with triggering of numerous seizures, which seems to lead to more widespread neuronal change and loss of behavioral specificity (Hannesson and Corcoran 2000). This is perhaps not surprising, given the widespread and reciprocal connections between the amygdala and hippocampus and the observation that electrical stimulation of either structure can lead to widespread functional changes in the other (Krettek and Price 1974, 1977; Colino and Fernandez de Molina 1986a, b; Canteras and Swanson 1992; Maren and Fanselow 1995; Pikkarainen et al. 1999; Abe 2001). In our view, therefore, the specificity of the behavioral changes associated with kindling suggests that such changes are due to alterations in the sites and circuits directly activated by kindling stimulation and not to more widespread changes associated with triggering of generalized seizures (Hannesson and Corcoran 2000; Teskey et al. 2006).

A cardinal characteristic of kindling is that the kindling-induced increase in susceptibility to seizures is extremely long-lasting and probably permanent (Wada et al. 1974). Together with the evidence reviewed above, this suggests that the underlying mechanism, the “trace” of kindling in Goddard’s terminology (Goddard and Douglas 1976) is due to a profound perturbation of cellular biology. Although the trace of kindling has been sought at various levels of analysis, we suggest that these data collectively raise the possibility that kindling involves fundamental molecular changes, either in the expression of mRNA (Kandel 2001) and/or in posttranslational changes in key protein products of gene activity, such as GAP-43 (Routtenberg and Rekart 2005).

Several previous studies have described changes in specific genes after kindling or induction of epileptic status with kindling-like stimulation (Lukasiuk et al. 2003; Gorter et al. 2006). Our approach to a microarray investigation of changes in gene expression after kindling in rats was somewhat different. We employed an ontological analysis (described in Kroes et al. 2006) in which we focused on co-regulation of multiple genes (gene sets) that are functionally related or related by involvement in a given biological pathway. Furthermore, our line of attack was to compare gene changes after kindling of two different structures, based on the finding that kindling is followed by significant and persistent behavioral effects that are specific to the area kindled, as discussed above. We asked whether kindling of the hippocampus, which produces changes in spatial cognition but not in affective behavior, is associated with changes in specific genes or gene sets in hippocampus and amygdala, whereas kindling of the amygdala, which produces increases in anxiety-like behavior but does not affect spatial cognition, is associated with a similar or different pattern of changes in genes in the hippocampus and amygdala. The strategy was to kindle from stimulation of the amygdala or the hippocampus to the same end-point, five generalized seizures, so that genetic changes resulting from seizures themselves were held constant in the kindled groups. We euthanized the rats 2 weeks after their last seizure, at a time when behavioral effects are evident (Hannesson and Corcoran 2000) but nonspecific ictal effects should have subsided. Thus, gene expression was measured under conditions in which the ictal consequences of kindling from the amygdala or hippocampus were the same, but the behavioral consequences were different.

Methods

Subjects

We used adult male Long-Evans rats from Charles Rivers Laboratories (St. Constant, Quebec, Canada), weighing 300–350 g at the time of surgery. Rats were housed in groups of three prior to surgery and individually housed thereafter. Food and water were freely available. Lights followed a 12 h:12 h light–dark schedule, with lights on at 7 a.m. Housing and experimental procedures were in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care. Approval was also given by the University of Saskatchewan Committee on Animal Care and Supply. Beginning 1 day after arrival in the facility, rats were individually handled for 3–5 min daily for 5 days before implantation of electrodes.

Surgical Procedure

Rats were anesthetized with 3% isofluorane and given a subcutaneous injection of a preoperative analgesic, anafen (1 ml/kg). They were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus, the skull was leveled, and bipolar nichrome wire electrodes (127 μm dia.) were implanted bilaterally in either the basolateral amygdala (coordinates relative to bregma: −2.7 mm [AP]; 4.6 mm [ML]; 8.8 mm [DV]), or into field CA1 of the dorsal hippocampus (coordinates relative to bregma: −2.7 mm [AP]; 4.6 mm [ML]; 8.8 mm [DV]). Five jewelers’ screws were used to secure the electrode assembly to the skull, with one screw over the anterior cortex serving as the reference electrode. The electrode assembly was affixed to the skull with dental acrylic, and a topical antibiotic/steroid, Topagen™ was applied to the wound.

Kindling

One week after surgery, rats in the kindled groups received a train of conventional high-frequency kindling stimulation in either the amygdala or the hippocampus once daily. Electrical stimulation consisted of a 1-s train of balanced biphasic square-wave pulses. Each pulse (positive or negative) was 1.0 ms in duration and delivered at 60 pulse-pairs per second. EEG was collected digitally at 100 samples per second (Polyview 2.3, AstroMed, Inc, Warwick RI). Afterdischarge thresholds (ADTs) were determined at one of the electrodes. The initial stimulation current was set at 20 μA (base to peak) and increased in increments of 20 μA at 2 min intervals until an AD was evoked. The AD threshold (ADT) was arbitrarily defined as the minimal intensity of stimulation producing an AD outlasting the stimulation by at least 5 s. Stimulation at the ADT was applied once daily until five consecutive stage—five generalized seizures (Racine 1972b) had been triggered. Control and experimental (kindled) rats were exposed to the kindling environment simultaneously, but placed in different chambers. Controls were connected to a stimulation lead, but no current was passed. Experimental rats were connected to a lead, and kindling stimulation was passed to the appropriate electrode. Rats were not physically restrained and allowed to freely move, although a lead was connected to the stimulator and EEG recording apparatus in each group.

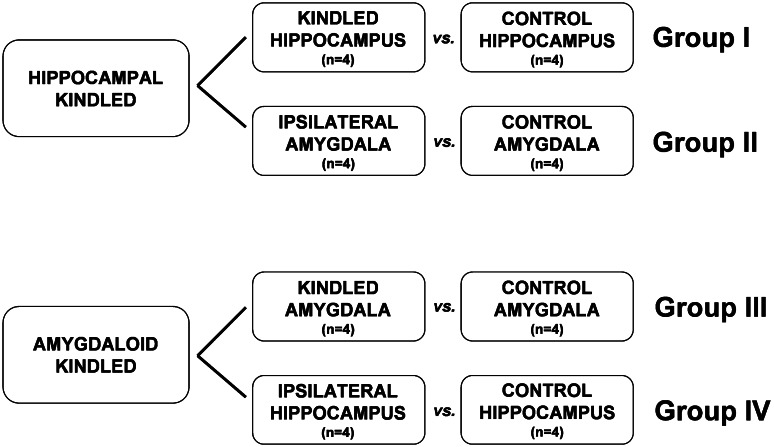

Tissue Dissection

Fourteen days after the last seizure, we euthanized the rats in a CO2 chamber. The brains were quickly removed and placed cortex down on a chilled aluminum cutting block (Heffner et al. 1980). Single-edge razor blades were inserted into channels cut at a right angle to the long axis of the block. When the razor blades were removed, coronal slabs 1.5–2.0 mm thick adhered to the blades, which were then placed on a plate suspended on crushed ice. Fine iris scissors were used to dissect the amygdala and, separately, the hippocampus, including both dorsal hippocampus and ventral hippocampus posterior to the amygdala, from both hemispheres of the brain. Samples of the amygdala were taken from Bregma −1.80 to −3.30 mm (AP). Samples of the hippocampus were taken from Bregma −2.12 to −6.04 mm (AP). Tissue samples were immersed immediately in an RNAse inhibitor (RNAlater, Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and stored at −20°C until microarray analysis. Samples from each region and each hemisphere were stored separately from each other. We used only the amygdala and hippocampus from the stimulated (i.e., kindled) hemisphere in our analyses; tissue from the contralateral (non-stimulated) hemisphere was not included. A schematic of the experimental strategy is shown below:

Focused Microarray Transcriptome Profiling

The genes comprising the in-house rat CNS microarray were compiled from currently available NCBI/EMBL/TIGR rat sequence databases and commercially available CNS arrays (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and strategically chosen to provide representation of greater than 90% of the major gene ontological categories. Individual 45-mer oligonucleotides complementary to sequences of 1178 cloned rat CNS genes (listed in Supplementary Table 1) were spotted in triplicate onto slides. For a full description of the microarray, please see Kroes et al. (2006, 2007). Microarray and data analysis were conducted as previously described in Kroes et al. (2006), (2007). Microarray analyses were performed on tissues from individual animals in triplicate. Total mRNA was isolated from the hippocampus and amygdala separately for individual kindled rats (RNeasy, Qiagen, USA), converted to amplified RNA (aRNA; Amino Allyl MessageAmpII, Ambion, USA), and indirectly labeled with Cy5 (experimental) or Cy3 (universal rat reference) (GE Healthcare, USA). Ten micrograms each of the purified Cy5-labeled (experimental) and Cy3-labeled (reference) aRNA targets (each labeled to 15–18% incorporation) were combined in a hybridization solution, denatured, and hybridized to the microarrays at 46°C for 16 h. Following sequential high-stringency washes, individual Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence hybridization to each spot on the microarray was quantified by a high resolution confocal laser scanner (ScanArray 4000XL, Packard Biochip Technologies, USA). Data were LOWESS normalized and extensively quality controlled and quantified by BlueFuse (BlueGnome, USA). The data were then analyzed by the Significance Analysis of Microarray (SAM) algorithm (v1.13, Stanford University), using a stringent False Discovery Rate (FDR) of <1%, followed by ontological data mining using GoMiner (Zeeberg et al. 2003) to identify enriched pathways, exactly as described in Kroes et al. (2006), Kroes et al. (2007). Briefly, the SAM analyses utilize an algorithm based on the Student’s t-test to derive statistically significantly differentially expressed genes between two groups of samples using a permutation-based determination of the median false discovery rate (FDR). The SAM algorithm reports the FDR as the percentage of genes in the identified gene list (rather than in the entire cohort of genes present on the microarray) that are falsely reported as showing statistically significant differential expression. The threshold of differential expression can be adjusted to identify different sizes of sets of putatively significant genes, and FDRs are modified accordingly. In our analyses, appropriately normalized data were analyzed utilizing the two class, unpaired analysis on a minimum of 5,000 permutations and was performed comparing expression data derived from kindled animals versus yoked control animals. The cut off for significance in these experiments was set at a stringent FDR of <1% at a specified 1.07-fold change.

qRT-PCR Analyses

To augment the microarray results, qRT-PCR was conducted as previously described (Kroes et al. 2006, 2007). Total mRNA was isolated from the hippocampus and amygdala separately for individual rats (RNeasy, Qiagen, USA), and converted to cDNA (SuperScript® III, Invitrogen, USA). qRT-PCR was performed using Brilliant SYBR Green qRT-PCR Master Mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) on an Mx3000P Real-Time PCR System with ROX reference dye. Gene-specific primers were designed to generate approximately 100 bp amplicons with PerlPrimer software and Primer 3 software. Primers were chosen within exons separated by large introns, when possible, and PCR quality and specificity were verified by gel electrophoresis and melting-curve dissociation analysis of the amplified product. Amplification parameters including primer concentrations, and annealing temperatures were optimized for each primer pair. Original input cDNA amounts were calculated by comparison to standard curves using purified PCR product as a template for the mRNAs of interest and were normalized to the amount of acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 mRNA. The sequences of the qRT-PCR primers used in the study were as follows:

NR1 (NM_017010) forward, 5′-ATGGCTTCTGCATAGACC-3′; reverse, 5′-GTTGTTTACCCGCTCCTG-3′.

NR2A (NM_012573) forward, 5′-AGTTCACCTATGACCTCTACC-3′; reverse, 5′-GTTGATAGACCACTTCACCT-3′

NR2B (NM_012574) forward, 5′-AAGTTCACCTATGACCTTTACC-3′; reverse, 5′-CATGACCACCTCACCGAT-3′

NR2C (U08259) forward, 5′-GGCCCAGCTTTTGACCTTAGT-3′; reverse, 5′-CCTGTGACCACCGCAAGAG-3′

NR2D (NM_022797) forward, 5′-GTTATGGCATCGCCCTAC-3′; reverse, 5′-CATCTCAATCTCATCGTCCC-3′

GRIA1 (X17184) forward, 5′-AAATTGCTTATGGGACATTG-3′; reverse, 5′-GCAGACTTCATGTATGTCCA-3′

GRIA2 (M36419) forward, 5′-GACTCTGGCTCCACTAAAGA-3′; reverse, 5′-AGTCCTCACAAACACAGAGG-3′

GRIM3 (M92076) forward, 5′-TATAGGCTTCACCATGTACAC-3′; reverse, 5′-AGGCGTAGCTTATCTGAGG-3′

EAAT1 (X63744) forward, 5′-CTCAATGAAGCCATCATGAG-3′; reverse, 5′-AATCACACCCATATCTTCCA-3′

EAAT3 (NM_013032) forward, 5′-GTCACCCTCATCATTGCC-3′; reverse, 5′-GGACAGCTTCTCCACGAT-3′

EAAT4 (U89608) forward, 5′-CCCTTTCCCTTCATCGGT-3′; reverse, 5′-AGGCATCGGAAAGTGATAGG-3′

PSD95 (M96853) forward, 5′-CAGGAGTTCACAGAGTGCTT-3′; reverse, 5′-GAGGTCTTCAATGACACGTT-3′

P0 (NM_022402) forward, 5′-CAGAGGTACCATTGAAATCC-3′; reverse, 5′-GTTCAACATGTTCAGCAGTG-3′

Results

The Development of Kindling

The ability to induce seizures is temporally dependent on whether animals are kindled in the hippocampus or in the amygdala. The characteristics of kindling from the hippocampus and the amygdala were similar to those described in the literature. The ADT (mean ± SEM) in the amygdala was 85.6 ± 8.2 μA, and the ADT in the hippocampus was 29.6 ± 3.4 μA, a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Amygdaloid stimulation led to the development of the first generalized seizure in 15.9 ± 1.8 stimulations; hippocampal kindling was significantly slower (P < 0.05) and led to the development of the first generalized seizure in 43.7 ± 6.2 stimulations. The duration of the first generalized seizure was 38.2 ± 6.1 s with amygdaloid kindling and 29.2 ± 2.2 s with hippocampal kindling, and this difference was not significant (P > 0.05).

Transcriptomic Analysis

The microarrays described in the Methods were used to identify genes associated with hippocampal and amygdaloid kindling by comparing the expression profile of kindled tissue with that of yoked controls. Analysis was performed with four individual specimens per group to decrease bias that may be introduced by donor-specific gene expression patterns. A reference experimental design was used. Kindled tissue (n = 4) and the corresponding tissue from yoked controls (n = 4) RNA samples were studied in triplicate with three microarray slides for each sample. As each oligonucleotide is spotted in quadruplicate on the array, there are a total of 72 expression measurements for each gene in each group. Study samples were labeled with Cy5 and universal rat reference samples (Stratagene) were labeled with Cy3 and hybridized to the arrays. Following LOWESS normalization and statistical evaluation of the data by Significance Analysis of Microarray (SAM) at for each of the paired kindled:yoked control comparisons, the following gene expression patterns emerged:

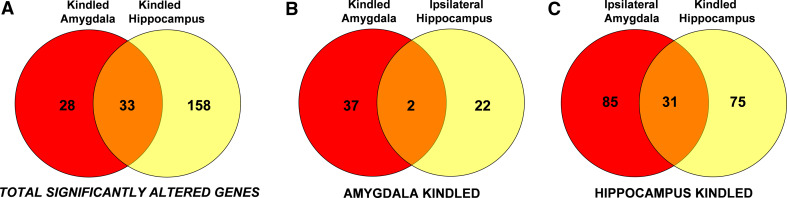

The number of genes identified differs in kindled hippocampus versus kindled amygdala. At a stringent FDR of <1%, 61 differentially expressed transcripts were identified following kindling in the amygdala and 191 transcripts identified following hippocampal kindling. Thirty three of the identified genes were common to both paradigms (summarized in Fig. 1).

The identities of affected genes and associated biological pathways identified differ between kindled hippocampus versus kindled amygdala. The individual identities of the differentially expressed genes in both the kindled and the ipsilateral tissue following amygdaloid and hippocampal kindling, as well as the major biological categories represented by these genes are summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4. Following ontological data mining using GoMiner to identify these enriched pathways, it becomes evident that the significantly enriched biological pathways identified in kindled tissue drastically differ depending upon the location of the kindling stimulation (comparison of Table 1 with Table 3).

- The numbers and identities of affected genes differ between kindled and non-kindled, ipsilateraltissues following hippocampal kindling or amygdaloid kindling. Among the 191 transcripts identified following hippocampal kindling, 31 (~16%) of the transcripts were common to both the kindled hippocampus and the ipsilateral amygdala. However, among the 61 differentially expressed transcripts were identified following kindling in the amygdala, only two (~3%) of these transcripts were common to both the kindled amygdala and the ipsilateral hippocampus (Fig. 1). There was no overlap in the identities of these commonly expressed gene sets between the hippocampally and amygdaloid-kindled tissues.

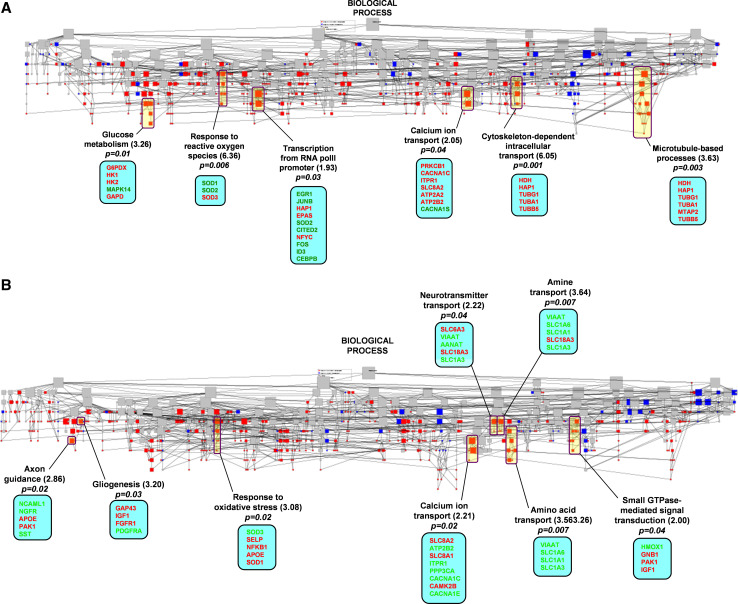

- Hippocampal kindling: Following hippocampal kindling, genes related to pathways involved in glucose metabolism, response to reactive oxygen species, RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription, intracellular transport, and cytoskeletal reorganization and biogenesis were enriched in the kindled hippocampal tissue. Conversely, and again following hippocampal kindling, pathways related to axon guidance, gliogenesis, response to stress, GTPase-mediated signal transduction, and transport of neurotransmitters, amines, and amino acids were enriched in the ipsilateral amygdala. Interestingly, genes in pathways related to calcium ion transport were enriched in both kindled and ipsilateral tissues, with upregulation of genes within this pathway primarily responsible for this enrichment in the kindled hippocampus and global downregulation of the pathway responsible for the enrichment in the ipsilateral amygdala (Fig. 2; Table 5).

- Amygdaloid kindling: Following amygdaloid kindling, pathways related to synaptic transmission, neurogenesis, cytoskeletal reorganization and biogenesis, cation transporter activity and neurotransmitter receptor activity were enriched in the kindled amygdala. In the ipsilateral hippocampus, pathways involved in cellular stress responses and protein metabolism, intracellular kinase signaling and cytoskeletal organization were significantly enriched (summarized in Table 5).

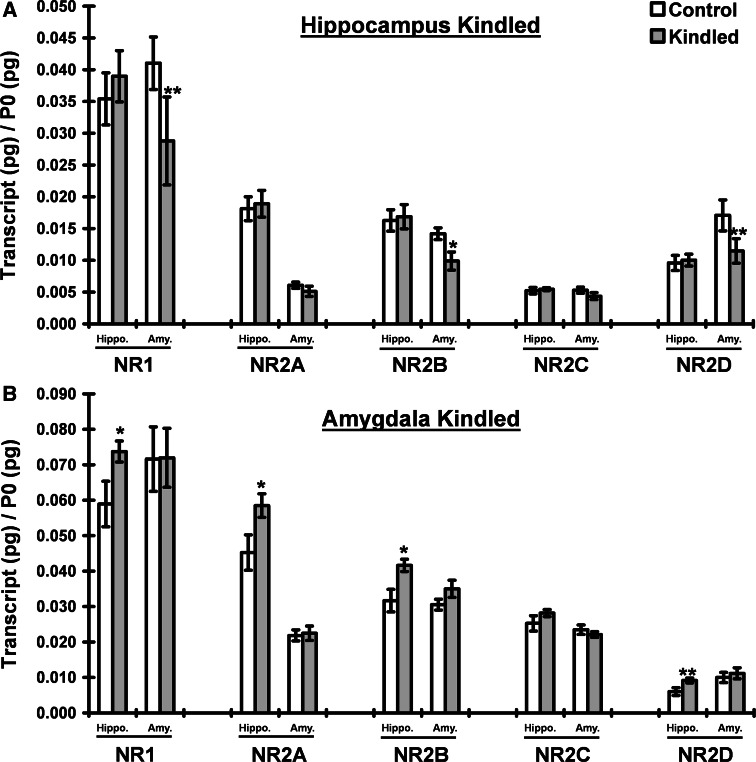

Genes within the glutamatergic signaling pathway are differentially regulated in hippocampally kindled tissues. The asymmetric changes in glutamatergic transcripts identified by microarray analysis in the hippocampally kindled tissues are summarized in Table 6. While all of the changes measured in the kindled tissue were due to upregulation of transcript levels (as compared to yoked control hippocampal tissue), the enrichment of glutamatergic transcripts in the ipsilateral amygdaloid tissue were primarily due to downregulation. The qRT-PCR corroboration of these changes is summarized in Table 4. In addition, due both to the direct role that NMDA receptor-mediated signaling in the hippocampus plays in the generation of epileptic seizures (Mody and Heinemann 1987) and the transcriptomic data generated in these studies, we also performed comprehensive qRT-PCR analysis of the NMDAR subunits (NMDAR1, NMDAR2A-D, and NMDA3A-B) in both kindled and ipsilateral tissues from hippocampally and amygdaloid-kindled animals (Fig. 3). The expression of NR3A and NR3B were below quantitation limits in all of the tissues analyzed. In the hippocampally kindled tissues, significant changes in NR1, NR2B, and NR2D were observed, all downregulated in ipsilateral amygdala. No significant changes in the kindled hippocampus were detected. Conversely, in the amygdaloid-kindled tissues, significant changes in NR1, NR2A, NR2B, and NR2D were observed, all upregulated in the ipsilateral hippocampus. No significant changes in the kindled amygdala were detected.

Fig. 1.

Venn diagrams comparing the common and exclusively expressed genes following kindling in either amygdala or hippocampus. a Statistically significant differentially expressed genes identified in kindled amygdala (i.e., following amygdaloid kindling) and kindled hippocampus (i.e., following hippocampal kindling). b Identified genes in the kindled amygdala and ipsilateral hippocampus following amygdaloid kindling. c Identified genes in the kindled hippocampus and ipsilateral amygdala following hippocampal kindling

Table 1.

Hippocampus-associated transcripts in hippocampal-kindled animals (<1% FDR)

| Gene ID | Fold changea |

|---|---|

| Cation transport | |

| γ-Aminobutyric acid receptor, subunit β1 | 3.47 |

| Solute carrier family 1 (glial high affinity glutamate transporter), member 3 (EAAT1) | 2.39 |

| Proteolipid protein | 1.83 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA1 (alpha 1) | 1.42 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, 2 | 1.31 |

| Potassium channel subunit (slack) | 1.26 |

| g protein-coupled receptor 51 | 1.26 |

| γ-Aminobutyric acid receptor, subunit β2 | 1.26 |

| Neurexin 2 | 1.26 |

| Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3 | 1.23 |

| Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 1 | 1.22 |

| ER transmembrane protein dri 42 | 1.21 |

| Limbic system-associated membrane protein | 1.20 |

| ATPase, Ca++ transporting, plasma membrane 2 | 1.19 |

| Tachykinin receptor 3 | 1.18 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDA2C | 1.18 |

| ATPase, Ca++ transporting, cardiac muscle, slow twitch 2 | 1.17 |

| Solute carrier family 8 (sodium/calcium exchanger), member 2 | 1.16 |

| Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily f, member 1 | 1.15 |

| Post synaptic density 95 protein (PSD-95) | 1.15 |

| Potassium voltage-gated channel, shaw-related subfamily, member 1 | 1.14 |

| Synaptosomal-associated protein 25 | 1.14 |

| Huntingtin-associated protein 1 | 1.13 |

| Kringle containing transmembrane protein | 1.13 |

| 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 1f | 1.12 |

| Solute carrier family 2, member 5 | 1.10 |

| Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, l type, alpha 1c subunit | 1.10 |

| Growth hormone 1 | 1.08 |

| Adenosine A3 receptor | 1.08 |

| ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, β3 polypeptide | −1.64 |

| CD9 antigen | −1.63 |

| CD48 antigen | −1.55 |

| Benzodiazepine receptor, peripheral | −1.48 |

| Transferrin receptor | −1.45 |

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, beta polypeptide 2 (neuronal) | −1.44 |

| CD63 antigen | −1.31 |

| Amiloride-sensitive cation channel 2, neuronal | −1.31 |

| Potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily j, member 4 | −1.27 |

| Potassium large conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily m, beta member 1 | −1.24 |

| 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 6 | −1.23 |

| Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, l type, alpha 1s subunit | −1.20 |

| Cytoskeletal organization/biosynthesis | |

| Tubulin, α1 | 1.91 |

| Tubulin, γ1 | 1.81 |

| Lamin a | 1.40 |

| Tubulin, β5 | 1.34 |

| Microtubule-associated protein 2 | 1.32 |

| Vimentin | 1.25 |

| Neurofilament, light polypeptide | 1.10 |

| Mitochondrial | |

| Nitric oxide synthase 1, neuronal | 1.35 |

| Monoamine oxidase b | −1.16 |

| Synaptic transmission | |

| Glutamate-ammonia ligase (glutamine synthase) | 1.18 |

| 4-Aminobutyrate aminotransferase | 1.10 |

| Neurogenesis | |

| Cholecystokinin | 1.53 |

| VGF nerve growth factor inducible | 1.21 |

| Insulin-like growth factor 1 | 1.18 |

| Nerve growth factor receptor (TNFR superfamily, member 16) | 1.07 |

| Glycolysis | |

| Hexokinase 1 | 2.31 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 1.73 |

| Hexokinase 2 | 1.41 |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | 1.17 |

| Protein metabolism | |

| Peptidylprolyl isomerase a | 1.49 |

| Heat shock 90kda protein 1β | 1.13 |

| Ribosomal protein L7a (predicted) | −1.55 |

| Calpain 2 | −1.23 |

| Calpain 8 | −1.19 |

| Signal transduction | |

| Guanine nucleotide binding protein, αo | 2.33 |

| Guanine nucleotide binding protein (g protein), β-polypeptide 2 like 1 | 1.34 |

| Guanine nucleotide binding protein, β1 | 1.17 |

| Transducin-like enhancer of split 4, e(spl) homolog (drosophila) | −1.32 |

| Serine/threonine kinase + ATP binding | |

| Protein kinase c, β1 | 1.41 |

| Fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 | 1.10 |

| Pregnancy upregulated non-ubiquitously expressed cam kinase | 1.08 |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | −1.26 |

| Casein kinase 1δ | −1.24 |

| Transcription | |

| H3 histone, family 3b | 1.57 |

| S100 protein, beta polypeptide | 1.29 |

| Interleukin 6 | 1.21 |

| Huntington disease gene homolog | 1.15 |

| Nuclear transcription factor-yγ | 1.14 |

| Endothelial pas domain protein 1 | 1.11 |

| Retinoic acid receptor, α | 1.10 |

| Superoxide dismutase 3, extracellular | 1.10 |

| Heat shock 27kda protein 1 | −1.95 |

| CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (c/ebp), β | −1.81 |

| Inhibitor of DNA binding 3 | −1.77 |

| fbj murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | −1.62 |

| CBP/p300-interacting transactivator, with glu/asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain, 2 | −1.54 |

| Early growth response 1 | −1.46 |

| Jun-b oncogene | −1.42 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein u | −1.32 |

| Superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial | −1.26 |

| Superoxide dismutase 1 | −1.18 |

| Other | |

| Neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type 3 | 1.87 |

| Hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase | 1.84 |

| Transgelin 3 | 1.32 |

| Neurogranin | 1.32 |

| Glutathione s-transferase α3 | 1.18 |

| Calmodulin 1 | 1.16 |

| Similar to nex-1 | 1.11 |

| Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 | 1.10 |

| Synaptojanin 2 | 1.09 |

| γ-Synuclein | −2.06 |

| Glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor family receptor α2 | −1.18 |

| Glucosaminyl (n-acetyl) transferase 1, core 2 | −1.18 |

| Casein kinase 2, β subunit | −1.14 |

| Fucosyltransferase 1 | −1.14 |

aThe fold change was calculated between mean values of hippocampal kindled (n = 4) and yoked control (n = 4) rats. Positive values are indicative of an increase, and a negative a decrease, in gene expression in kindled relative to control hippocampus

Table 2.

Amygdala-associated transcripts in hippocampal-kindled animals (<1% FDR)

| Gene ID | Fold changea |

|---|---|

| Cation transport | |

| Arginine vasopressin | 1.70 |

| Growth associated protein 43 | 1.55 |

| Benzodiazepine receptor, peripheral | 1.50 |

| Solute carrier family 8 (sodium/calcium exchanger), member 2 | 1.27 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter), member 17 | 1.26 |

| Guanine nucleotide binding protein, β1 | 1.24 |

| Apolipoprotein e | 1.22 |

| Growth hormone 1 | 1.19 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDAR2D | 1.17 |

| ATPase, H+/K+ transporting, nongastric, α polypeptide | 1.16 |

| Potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily j, member 4 | 1.16 |

| Solute carrier family 18 (vesicular acetylcholine), member 3 | 1.15 |

| Solute carrier family 8 (sodium/calcium exchanger), member 1 | 1.13 |

| Cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript | 1.13 |

| Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 | 1.12 |

| Prostaglandin f receptor | 1.12 |

| Arginine vasopressin receptor 1b | 1.12 |

| Chloride channel 5 | 1.11 |

| Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, dopamine), member 3 | 1.11 |

| Selectin, platelet | 1.11 |

| Voltage-gated potassium channel subunit kv3.4 | 1.09 |

| Solute carrier family 1 (glial high affinity glutamate transporter), member 3 (EAAT1) | −1.56 |

| Somatostatin | −1.41 |

| Solute carrier family 32 (GABA vesicular transporter), member 1 | −1.41 |

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) a receptor, subunit gamma 3 | −1.39 |

| Galanin receptor 1 | −1.38 |

| Syntaxin 12 | −1.38 |

| ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, beta 3 polypeptide | −1.37 |

| Neuromedin b receptor | −1.27 |

| Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 1 | −1.26 |

| L1 cell adhesion molecule | −1.26 |

| Potassium voltage-gated channel, shaker-related subfamily, member 3 | −1.25 |

| Gastrin releasing peptide receptor | −1.22 |

| 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2b | −1.22 |

| Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily q, member 1 | −1.22 |

| Cortexin | −1.20 |

| Purinergic receptor p2x-like 1, orphan receptor | −1.19 |

| Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, l type, α1e subunit | −1.19 |

| Scavenger receptor class b, member 1 | −1.19 |

| β2 microglobulin | −1.19 |

| Nerve growth factor receptor (TNFR superfamily, member 16) | −1.18 |

| Glutamate receptor, metabotropic 3 | −1.18 |

| Dopamine receptor 4 | −1.18 |

| Adrenergic receptor, α1d | −1.17 |

| Solute carrier family 1 (neuronal high affinity glutamate transporter, member 1) (EAAT3) | −1.16 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDAR1 | −1.16 |

| Integrin β4 | −1.16 |

| ATPase, Ca++ transporting, plasma membrane 2 | −1.16 |

| Transforming growth factor β receptor III | −1.16 |

| 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 6 | −1.16 |

| Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, l type, α1c subunit | −1.15 |

| Potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily j, member 1 | −1.13 |

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, α-polypeptide 5 | −1.13 |

| Glycine receptor, α1 subunit | −1.12 |

| Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily f, member 1 | −1.11 |

| Amiloride-sensitive cation channel 1, neuronal (degenerin) | −1.11 |

| Potassium large conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily m, β member 1 | −1.11 |

| Solute carrier family 1 (high affinity aspartate/glutamate transporter), member 6 (EAAT4) | −1.10 |

| Transferrin | −1.10 |

| Potassium channel subunit (slack) | −1.08 |

| Amine biosynthesis | |

| Phenylethanolamine-n-methyltransferase | −1.16 |

| Arylalkylamine n-acetyltransferase | −1.11 |

| Cytoskeletal organization/biosynthesis | |

| Vimentin | −1.36 |

| Lamin a | −1.27 |

| Glycolysis | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 1.47 |

| γ-Enolase 2 | 1.39 |

| Hexokinase 2 | −1.57 |

| Serine/threonine kinase activity + ATP binding | |

| Ribosomal protein L7a | 1.26 |

| Tripeptidyl peptidase ii | 1.24 |

| p21 (cdkn1a)-activated kinase 1 | 1.23 |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 | 1.22 |

| CD9 antigen | 1.21 |

| Platelet derived growth factor, b polypeptide | 1.19 |

| Protein kinase c, γ | 1.14 |

| Bassoon | 1.14 |

| Superoxide dismutase 1 | 1.14 |

| β1 adrenergic receptor kinase | 1.13 |

| Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II γ | 1.10 |

| Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II β subunit | 1.10 |

| Microtubule-associated protein 2 | −1.95 |

| Kallikrein-8 | −1.51 |

| Neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type 3 | −1.38 |

| Protein phosphatase 3, catalytic subunit, α isoform | −1.35 |

| 5′ nucleotidase | −1.31 |

| Carboxypeptidase e | −1.29 |

| Praja 2, ring-h2 motif containing | −1.21 |

| Platelet derived growth factor receptor, α polypeptide | −1.20 |

| Superoxide dismutase 3, extracellular | −1.20 |

| Arginyl aminopeptidase | −1.19 |

| Peptidylprolyl isomerase a | −1.19 |

| Citron | −1.18 |

| Pregnancy upregulated non-ubiquitously expressed CAM kinase | −1.17 |

| Transcription | |

| Inhibitor of DNA binding 3 | 1.49 |

| Nuclear factor of kappa light chain gene enhancer in b-cells 1, p105 | 1.19 |

| Catenin (cadherin associated protein), β1, 88kda | 1.17 |

| Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group h, member 2 | 1.16 |

| Jun-b oncogene | −1.49 |

| CBP/p300-interacting transactivator, with glu/asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain, 2 | −1.43 |

| Taf9-like rna polymerase ii, TATA box binding protein (TBP)-associated factor, 31kda | −1.39 |

| H3 histone, family 3b | −1.30 |

| Androgen receptor | −1.20 |

| Other | |

| Myelin basic protein | 1.66 |

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | 1.37 |

| Laminin receptor 1 (ribosomal protein sa) | 1.33 |

| Glutamate-ammonia ligase (glutamine synthase) | 1.24 |

| Insulin-like growth factor 1 | 1.24 |

| Tubulin, α1 | 1.22 |

| Glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor family receptor alpha 2 | 1.14 |

| Prostaglandin f receptor | 1.12 |

| Kallikrein 8 (neuropsin/ovasin) | −1.51 |

| Dual specificity phosphatase 5 | −1.35 |

| Macrophage stimulating 1 (hepatocyte growth factor-like) | −1.17 |

| Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 | −1.12 |

| Nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible | −1.12 |

| Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | −1.12 |

| Phospholipase a2, group vi | −1.10 |

aThe fold change was calculated between mean values of hippocampal kindled (n = 4) and yoked control (n = 4) rats. Positive values are indicative of an increase, and a negative a decrease, in gene expression in kindled relative to control amygdala

Table 3.

Amygdala-associated transcripts in amygdaloid-kindled animals (<1% FDR)

| Gene ID | Fold changea |

|---|---|

| Synaptic transmission | |

| Opioid receptor, kappa 1 | 1.42 |

| Neuropeptide y | 1.37 |

| Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) a receptor, subunit γ3 | 1.32 |

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor, member 6 | 1.30 |

| Cortexin | 1.27 |

| β4 integrin | 1.26 |

| Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, l type, α1e subunit | 1.23 |

| Solute carrier family 8 (sodium/calcium exchanger), member 1 | 1.21 |

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, β polypeptide 2 (neuronal) | 1.20 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDAR1 | 1.19 |

| Tachykinin receptor 3 | 1.19 |

| Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily f, member 1 | 1.17 |

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, α polypeptide 5 | 1.16 |

| Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, l type, α1s subunit | 1.15 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit vic | 1.14 |

| Amiloride-sensitive cation channel 1, neuronal (degenerin) | 1.14 |

| Kringle containing transmembrane protein | 1.13 |

| Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily q, member 1 | 1.13 |

| 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 1f | 1.12 |

| Solute carrier family 1 (glial high affinity glutamate transporter), member 3 | −1.25 |

| Arginine vasopressin | −1.23 |

| 5-Hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 3a | −1.16 |

| Neurogenesis | |

| Apolipoprotein e | 1.36 |

| Fasciculation and elongation protein zeta 1 (zygin i) | 1.26 |

| Cytoskeletal organization/biogenesis | |

| β-actin | 1.34 |

| Tubulin, β5 | 1.24 |

| Citron | 1.19 |

| Microtubule-associated protein 1 a | 1.18 |

| Other | |

| Hexokinase 2 | 1.56 |

| Glutamate decarboxylase 1 | 1.31 |

| Lamin a | 1.29 |

| Peptidylprolyl isomerase a | 1.24 |

| Vimentin | 1.24 |

| Superoxide dismutase 3, extracellular | 1.23 |

| Transducin-like enhancer of split 4, e(spl) homolog (drosophila) | 1.19 |

| Superoxide dismutase 1 | 1.13 |

| Guanine nucleotide binding protein, β1 | 1.13 |

| Notch gene homolog 3 (drosophila) | −1.20 |

| Sry-box containing gene 10 | −1.14 |

aThe fold change was calculated between mean values of amygdala kindled (n = 4) and yoked control (n = 4) rats. Positive values are indicative of an increase, and a negative a decrease, in gene expression in kindled relative to control amygdala

Table 4.

Hippocampus-associated transcripts in amygdaloid-kindled animals (<1% FDR)

| Gene ID | Fold changea |

|---|---|

| Intracellular signaling | |

| Protein kinase c, β1 | 1.59 |

| Protein phosphatase 3, catalytic subunit, α isoform | 1.33 |

| Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II β subunit | −1.19 |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 | −1.17 |

| Synaptic transmission | |

| Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein | 2.34 |

| Dopamine receptor 4 | 1.28 |

| Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, α polypeptide 7 | −1.67 |

| Purinergic receptor p2y, g-protein coupled 1 | −1.25 |

| Sodium channel, nonvoltage-gated, type i, α polypeptide | −1.14 |

| Other | |

| Neuritin | 1.79 |

| Carboxypeptidase e | 1.33 |

| Nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible | 1.33 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 1.23 |

| β-Actin | 1.22 |

| Guanine nucleotide binding protein (g protein), beta polypeptide 2 like 1 | −1.86 |

| Tubulin, γ1 | −1.50 |

| Ribosomal protein L35a | −1.44 |

| Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | −1.36 |

| H3 histone, family 3b | −1.24 |

| Superoxide dismutase 1 | −1.21 |

| β2-Arrestin | −1.20 |

| Macrophage stimulating 1 (hepatocyte growth factor-like) | −1.16 |

| Dual specificity phosphatase 5 | −1.16 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein u | −1.16 |

aThe fold change was calculated between mean values of amygdala kindled (n = 4) and yoked control (n = 4) rats. Positive values are indicative of an increase, and a negative a decrease, in gene expression in kindled relative to control hippocampus

Fig. 2.

GOMiner-based ontological analysis identifies key biological pathways involved in hippocampal kindling-associated gene expression. The 114 differentially expressed genes identified by microarray analysis of the kindled hippocampus versus yoked controls (a) and the 116 differentially expressed genes identified of the ipsilateral amygdala versus yoked controls (b) from hippocampally kindled rats were imported into the GoMiner program to generate directed acylic graphs (DAG) for the biological processes and molecular functions represented by the changes and were based on current annotations in the GO database. Each node of the DAG represents one GO category at various levels. The distribution of these genes is represented by a different color at each node. The color indicates enrichment (red), depletion (blue) or no change (gray) of the genes compared with the distribution over all identified genes at that level. Red and green text within the blue insets represents those individual genes upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in kindled tissue compared to tissue from yoked controls. (Color figure online)

Table 5.

Summary of the ontological analyses in kindled tissues

| Biological process | Molecular function |

|---|---|

| Hippocampal kindling | |

| Right hippocampus versus yoked control | |

| Cytoskeletal organization/biogenesis (esp. µtubule-based processes) | Transcription factor binding activity |

| Cation transport (esp. Ca++ ion transport) | Cytoskeletal structural mol. activity |

| Response to oxidative stress | GTPase activity |

| Glucose metabolism/catabolism | |

| Right amygdala versus yoked control | |

| Neurite morphogenesis/gliogenesis (esp. axon guidance) | Carrier activity |

| Cation transport (esp. Ca++ ion transport) | Anion transport activity |

| Neurotransmitter/amine/organic acid transport | Calmodulin binding |

| GTPase-mediated signal transduction | |

| Amygdaloid kindling | |

| Left amygdala versus yoked control | |

| Synaptic transmission | Ion (esp. cation) transporter activity |

| Neurogenesis | Neurotransmitter binding/receptor activity |

| Sensory perception | |

| Cytoskeletal organization/biogenesis (esp. µtubule-based processes) | |

| Left hippocampus versus yoked control | |

| Cellular protein metabolism | Protein kinase activity (tyr and ser/thr) |

| Stress response | Oxidoreductase activity |

| Intracellular signaling (protein kinase/MAPK) | Nucleotide binding (esp. ATP) |

| Cytoskeletal organization |

Table 6.

Differentially regulated glutamatergic gene expression in hippocampally kindled tissues

| Gene | Fold change | P-value of qRT-PCR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microarray | qRT-PCR | ||

| Hippocampal-kindled hippocampus | |||

| Solute carrier family 1 (glial high affinity glutamate transporter), member 3 (EAAT1) | 2.39 | 1.11 | 0.444 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA1 (GRIA1) | 1.42 | 1.21 | 0.130 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA2 (GRIA2) | 1.31 | 1.30 | 0.030 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDAR2C | 1.18 | 1.04 | 0.608 |

| Post synaptic density 95 protein (PSD-95) | 1.15 | 1.03 | 0.795 |

| Hippocampal-kindled amygdala | |||

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDAR2D | 1.17 | −1.33 | 0.006 |

| Solute carrier family 1 (glial high affinity glutamate transporter), member 3 (EAAT1) | −1.56 | −1.30 | 0.046 |

| Glutamate receptor, metabotropic 3 (GRM3) | −1.18 | −1.30 | 0.009 |

| Solute carrier family 1 (neuronal/epithelial high affinity glutamate transporter, member 1 (EAAT3) | −1.16 | −1.16 | 0.043 |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDAR1 | −1.16 | −1.30 | 0.004 |

| Solute carrier family 1 (high affinity aspartate/glutamate transporter), member 6 (EAAT4) | −1.10 | −1.20 | 0.029 |

Fig. 3.

Kindling selectively alters NMDA receptor subunit mRNA levels in the hippocampus and amygdala. NMDA receptor subunit mRNA levels in the hippocampus and amygdala following ipsilateral kindling in the hippocampus (a) or amygdala (b). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM pg transcript/pg P0. Hippocampal kindling significantly altered NMDA receptor levels in the ipsilateral amygdala (F(1,98) = 25.0 P < 0.0001) but not in the kindled hippocampus. Amygdala kindling significantly altered NMDA receptor levels in the ipsilateral hippocampus (F(1,98) = 16.5 P < 0.0001) but not in the kindled amygdala (F(1,98) = 0.6 P > 0.05). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 Fisher PLSD post hoc tests comparing kindled versus yoked control (within-subjects). n = 10 rats per group

Discussion

Our study was designed to determine whether hippocampal kindling and amygdaloid kindling are associated with different effects on gene expression, when the endpoint of kindling is held constant. In this study, we kindled to five generalized seizures. As the kindled groups underwent the same number of stage 5 seizures, changes in gene expression were thus not a function of seizures per se but must instead reflect alterations in the specific neuronal circuits engaged by stimulating the hippocampus versus the amygdala. We note that although both groups were kindled to the same endpoint of generalized seizures, the amygdala and hippocampus differ in epileptogenicity. Thus, as has been described in many previous studies, the ADT was lower in hippocampus than in amygdala; conversely, significantly fewer stimulations of the amygdala than of the hippocampus were required to reach the defined endpoint of kindling. It might be interesting to determine whether differential effects on gene expression would be observed if the same number of stimulations was applied to each structure, although of necessity this would result in kindling reaching different endpoints.

For the transcriptome analyses, we used an in-house-fabricated, focused microarray platform that merits further elaboration. The quality of our platform has been rigorously evaluated in terms of dynamic range, discrimination power, accuracy, reproducibility, and specificity. The ability to reliably measure even low levels of statistically significant differential gene expression stems from coupling (a) stringently designed and quality controlled chip manufacturing and transcript labeling protocols; (b) rigorous data analysis algorithms; and (c) flexible GoMiner ontological analyses capable of demonstrating significant correlations between the expression of specific gene sets. Used together, these technologies provide maximal statistical rigor to transcriptomic analyses and are capable of demonstrating significant correlations between the expression of specific gene sets and complex phenotypic distinctions even if the expression of individual genes do not. When combined with robust qRT-PCR corroboration, this approach provides a powerful platform to identify fundamental, biologically relevant gene families significantly altered in regio-specific kindling.

The ontological analysis of the microarray data derived in these studies revealed that the effects of kindling on gene expression were unexpectedly complex and varied along several dimensions, both as a function of the site kindled and of the specific structure sampled. As detailed in the Results section, different numbers of affected genes were identified in the kindled amygdala versus the kindled hippocampus; the genes affected by amygdaloid kindling differ to a great extent from the genes affected by hippocampal kindling; kindling of the two structures differentially affects the patterns of expression in kindled and ipsilateral, non-kindled tissue. For example, hippocampal kindling resulted in changes in expression of a number of genes previously described to change following epileptogenesis associated with epileptic status (Lukasiuk et al. 2003; Gorter et al. 2006), including genes involved in cytoskeletal reorganization and neurogenesis, cellular stress responses, signal transduction, and dynamics of neurotransmitters and other molecules. Additionally, we detected changes in genes regulating synaptic transmission, cytoskeletal reorganization, cation transporter activity, and other processes after kindling the amygdala. Perhaps of greatest interest, kindling is associated with region-specific changes in genes related to glutamatergic neurotransmission, and specifically to site-specific changes in the genes for subunits of the NMDA receptor.

Changes in the expression of the NMDA receptor are of particular interest for understanding the potential mechanisms of epileptogenesis for several reasons. First, many studies have shown that kindling is associated with a long-lasting increase in the release of glutamate (Geula et al. 1988) and increased efficacy of NMDA receptors (Behr et al. 2001). Second, glutamatergic transmission plays a critical role in kindling. Many studies, including some early reports (e.g., (Holmes et al. 1990), have shown that nonspecific NMDA antagonists delay kindling and suppress kindled seizures. Furthermore, pharmacological data with subunit-specific antagonists have implicated the NR2A subunit (Chen et al. 2007) in establishment of kindling and the triggering of generalized kindled seizures and the NR2B subunit (Barton and White 2004) in the triggering of generalized kindled seizures. In addition, the relations between mutations in the postnatally expressed NR2A and epilepsy have been recently described (Endele et al. 2010). Risk haplotypes of the common NR1 subunit have been associated with infantile spasms, further implicating functional NMDA receptors in epileptogenesis (Ding et al. 2010). Thus, the association of kindling with changes in the expression of individual NMDA subunits is particularly compelling.

An important aspect of our study is the comparison of the effects of hippocampal and amygdaloid kindling. As discussed above, complex changes in gene expression occurred in the hippocampus and the amygdala, and, surprisingly, these differed in tissue obtained from hippocampal-kindled versus amygdaloid-kindled rats. Our data linking changes in gene expression with the behaviorial consequences of kindling in specific structures are complex. Regulation of the NR2B/NR2A ratio of synaptic NMDA receptors (summarized in Table 7) is thought to be a major determinant of the developmental and experience-dependent properties of synaptic plasticity (Yashiro and Philpot 2008). As some epileptogenic changes include increased expression of Ca2+-conducting glutamate receptors/channels, including NMDARs, they could affect metaplasticity as well (Perez-Otano and Ehlers 2005). It may be of importance to understand regulatory mechanisms such as metaplasticity both to gain insight into the mechanisms of epilepsy and to provide targets for promoting functional recovery and repair. Decreased enrichment of NMDA receptors might also reflect the neuronal degeneration that has been described with kindling (Lehmann et al. 1998; von Bohlenund Halbach et al. 2004), although this is unlikely in view of the increased gene expression seen in the amygdala after amygdaloid kindling. More likely, kindling of different sites leads to radically different changes in glutamatergic gene expression in vivo. Further experiments employing regional infusions of specific antagonists of NMDA receptor subunits are necessary to evaluate the functional significance of these changes.

Table 7.

NR2B:NR2A ratios in kindled tissues

| Tissue | Control | Kindled | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal kindled (duration ~44 days) | |||

| Hippocampus | 0.89 (±0.02) | 0.90 (±0.02) | n/s |

| Amygdala | 2.34 (±0.04) | 1.84 (±0.03) | P < 0.05 |

| Amygdaloid kindled (duration ~16 days) | |||

| Hippocampus | 0.71 (±0.05) | 0.71 (±0.04) | n/s |

| Amygdala | 1.40 (±0.02) | 1.58 (±0.05) | P < 0.05 |

These results may also have important implications for the design of antiepileptic agents because they suggest that NR2A- and NR2B-containing NMDAR subtypes may be the best targets. Perhaps partial agonists possessing selectivity towards these receptor subtypes will have the greatest antiepileptic potential for they would have the ability to inhibit excessive receptor activity without totally shutting down the receptor’s ability to perform normal neuronal functions. Two such partial agonists with clinical potential are D-cycloserine and GLYX-13 (Zhang et al. 2008; Burgdorf et al. 2009). It will be worthwhile to test whether these reagents have a therapeutic effect for treatment of epilepsies.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (to MEC) and The Falk Foundation, Chicago, IL, (to JRM). We thank Joanne Sitarski, Ken Wolfe, Nigel Otto, and Mary Schmidt for expert technical assistance.

References

- Abe K (2001) Modulation of hippocampal long-term potentiation by the amygdala: a synaptic mechanism linking emotion and memory. Jpn J Pharmacol 86:18–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton ME, White HS (2004) The effect of CGX-1007 and CI-1041, novel NMDA receptor antagonists, on kindling acquisition and expression. Epilepsy Res 59:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behr J, Heinemann U, Mody I (2001) Kindling induces transient NMDA receptor-mediated facilitation of high-frequency input in the rat dentate gyrus. J Neurophysiol 85:2195–2202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beldhuis HJ, Everts HG, Van der Zee EA, Luiten PG, Bohus B (1992) Amygdala kindling-induced seizures selectively impair spatial memory. 1. Behavioral characteristics and effects on hippocampal neuronal protein kinase C isoforms. Hippocampus 2:397–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronzino JD, Austin-LaFrance RJ, Morgane PJ, Galler JR (1991a) Effects of prenatal protein malnutrition on kindling-induced alterations in dentate granule cell excitability. I. Synaptic transmission measures. Exp Neurol 112:206–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronzino JD, Austin-LaFrance RJ, Morgane PJ, Galler JR (1991b) Effects of prenatal protein malnutrition on kindling-induced alterations in dentate granule cell excitability. II. Paired-pulse measures. Exp Neurol 112:216–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf J, Zhang XL, Weiss C, Matthews E, Disterhoft JF, Stanton PK, Moskal JR (2009) The N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor modulator GLYX-13 enhances learning and memory, in young adult and learning impaired aging rats. Neurobiol Aging [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Canteras NS, Swanson LW (1992) Projections of the ventral subiculum to the amygdala, septum, and hypothalamus: a PHAL anterograde tract-tracing study in the rat. J Comput Neurol 324:180–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, He S, Hu XL, Yu J, Zhou Y, Zheng J, Zhang S, Zhang C, Duan WH, Xiong ZQ (2007) Differential roles of NR2A- and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in activity-dependent brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene regulation and limbic epileptogenesis. J Neurosci 27:542–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colino A, Fernandez de Molina A (1986a) Electrical activity generated in subicular and entorhinal cortices after electrical stimulation of the lateral and basolateral amygdala of the rat. Neuroscience 19:573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colino A, Fernandez de Molina A (1986b) Inhibitory response in entorhinal and subicular cortices after electrical stimulation of the lateral and basolateral amygdala of the rat. Brain Res 378:416–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran ME, Moshé SL (eds) (1998) Kindling five. Plenum, New York [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran ME, Moshé SL (eds) (2005) Kindling six. Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran ME, Teskey CG (2009) Characteristics and mechanisms of kindling. In: Schwartzkroin P (ed) Encyclopedia of basic epilepsy research, vol 2. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 741–746 [Google Scholar]

- Ding YX, Zhang Y, He B, Yue WH, Zhang D, Zou LP (2010) A possible association of responsiveness to adrenocorticotropic hormone with specific GRIN1 haplotypes in infantile spasms. Dev Med Child Neurol 52:1028–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endele S, Rosenberger G, Geider K, Popp B, Tamer C, Stefanova I, Milh M, Kortum F, Fritsch A, Pientka FK, Hellenbroich Y, Kalscheuer VM, Kohlhase J, Moog U, Rappold G, Rauch A, Ropers HH, von Spiczak S, Tonnies H, Villeneuve N, Villard L, Zabel B, Zenker M, Laube B, Reis A, Wieczorek D, Van Maldergem L, Kutsche K (2010) Mutations in GRIN2A and GRIN2B encoding regulatory subunits of NMDA receptors cause variable neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat Genet 42:1021–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geinisman Y, Morrell F, de Toledo-Morrell L (1988) Remodeling of synaptic architecture during hippocampal “kindling”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:3260–3264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula C, Jarvie PA, Logan TC, Slevin JT (1988) Long-term enhancement of K+-evoked release of l-glutamate in entorhinal kindled rats. Brain Res 442:368–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard GV, Douglas RM (1976) Does the engram of kindling model the engram of normal long term memory? In: Wada JA (ed) Kindling. Raven, New York, p 18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard GV, McIntyre DC, Leech CK (1969) A permanent change in brain function resulting from daily electrical stimulation. Exp Neurol 25:295–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter JA, van Vliet EA, Aronica E, Breit T, Rauwerda H, Lopes da Silva FH, Wadman WJ (2006) Potential new antiepileptogenic targets indicated by microarray analysis in a rat model for temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci 26:11083–11110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannesson DK, Corcoran ME (2000) The mnemonic effects of kindling. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 24:725–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannesson DK, Howland J, Pollock M, Mohapel P, Wallace AE, Corcoran ME (2001) Dorsal hippocampal kindling produces a selective and enduring disruption of hippocampally mediated behavior. J Neurosci 21:4443–4450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannesson DK, Howland JG, Pollock M, Mohapel P, Wallace AE, Corcoran ME (2005) Anterior perirhinal cortex kindling produces long-lasting effects on anxiety and object recognition memory. Eur J Neurosci 21:1081–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannesson DK, Pollock MS, Howland JG, Mohapel P, Wallace AE, Corcoran ME (2008) Amygdaloid kindling is anxiogenic but fails to alter object recognition or spatial working memory in rats. Epilepsy Behav 13:52–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner TG, Hartman JA, Seiden LS (1980) A rapid method for the regional dissection of the rat brain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 13:453–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LC, Goertzen CD, Lee A, Teskey GC (2008) Repeated seizures lead to altered skilled behaviour and are associated with more highly efficacious excitatory synapses. Eur J Neurosci 27:2165–2176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes KH, Bilkey DK, Laverty R, Goddard GV (1990) The N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonists aminophosphonovalerate and carboxypiperazinephosphonate retard the development and expression of kindled seizures. Brain Res 506:227–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvie PA, Logan TC, Geula C, Slevin JT (1990) Entorhinal kindling permanently enhances Ca2(+)-dependent l-glutamate release in regio inferior of rat hippocampus. Brain Res 508:188–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalynchuk LE, Pinel JP, Treit D (1998) Long-term kindling and interictal emotionality in rats: effect of stimulation site. Brain Res 779:149–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis W, Lopes da Silva FH, Wadman WJ (1988) Changes in local evoked potentials in the rat hippocampus (CA1) during kindling epileptogenesis. Brain Res 440:205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER (2001) The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between genes and synapses. Science 294:1030–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krettek JE, Price JL (1974) Projections from the amygdala to the perirhinal and entorhinal cortices and the subiculum. Brain Res 71:150–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krettek JE, Price JL (1977) Projections from the amygdaloid complex to the cerebral cortex and thalamus in the rat and cat. J Comput Neurol 172:687–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes RA, Panksepp J, Burgdorf J, Otto NJ, Moskal JR (2006) Modeling depression: social dominance-submission gene expression patterns in rat neocortex. Neuroscience 137:37–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes RA, Burgdorf J, Otto NJ, Panksepp J, Moskal JR (2007) Social defeat, a paradigm of depression in rats that elicits 22-kHz vocalizations, preferentially activates the cholinergic signaling pathway in the periaqueductal gray. Behav Brain Res 182:290–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann H, Ebert U, Loscher W (1998) Amygdala-kindling induces a lasting reduction of GABA-immunoreactive neurons in a discrete area of the ipsilateral piriform cortex. Synapse 29:299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung LS, Boon KA, Kaibara T, Innis NK (1990) Radial maze performance following hippocampal kindling. Behav Brain Res 40:119–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman DN, Mody I (1998) Substance P enhances NMDA channel function in hippocampal dentate gyrus granule cells. J Neurophysiol 80:113–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loscher W, Schwark WS (1987) Further evidence for abnormal GABAergic circuits in amygdala-kindled rats. Brain Res 420:385–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiuk K, Kontula L, Pitkanen A (2003) cDNA profiling of epileptogenesis in the rat brain. Eur J Neurosci 17:271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, Fanselow MS (1995) Synaptic plasticity in the basolateral amygdala induced by hippocampal formation stimulation in vivo. J Neurosci 15:7548–7564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I, Heinemann U (1987) NMDA receptors of dentate gyrus granule cells participate in synaptic transmission following kindling. Nature 326:701–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Otano I, Ehlers MD (2005) Homeostatic plasticity and NMDA receptor trafficking. Trends Neurosci 28:229–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikkarainen M, Ronkko S, Savander V, Insausti R, Pitkanen A (1999) Projections from the lateral, basal, and accessory basal nuclei of the amygdala to the hippocampal formation in rat. J Comput Neurol 403:229–260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine RJ (1972a) Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. I. After-discharge threshold. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 32:269–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine RJ (1972b) Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation, II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 32:281–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine R, Okujava V, Chipashvili S (1972) Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. 3. Mechanisms. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 32:295–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine RJ, Burnham WM, Gilbert M, Kairiss EW (1986) Kindling mechanisms: I. Electrophysiological studies. In: Wada JA (ed) Kindling three. Raven, New York, pp 263–279 [Google Scholar]

- Routtenberg A, Rekart JL (2005) Post-translational protein modification as the substrate for long-lasting memory. Trends Neurosci 28:12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinnick-Gallagher P, Bradley Keele N (1998) Long-lasting changes in the pharmacology and electrophysiology of amino acid receptors in amygdala kindled neurons. In: Corcoran ME, Moshé SL (eds) Kindling five. Plenum, New York, pp 75–87 [Google Scholar]

- Shao LR, Dudek FE (2005) Detection of increased local excitatory circuits in the hippocampus during epileptogenesis using focal flash photolysis of caged glutamate. Epilepsia 46(5):100–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter RS, Zappone CA, Harvey BD, Frotscher M (2006) Kainic acid-induced recurrent mossy fiber innervation of dentate gyrus inhibitory interneurons: possible anatomical substrate of granule cell hyper-inhibition in chronically epileptic rats. J Comput Neurol 494:944–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutula T, Zhang P, Lynch M, Sayin U, Golarai G, Rod R (1998) Synaptic and axonal remodeling of mossy fibers in the hilus and supragranular region of the dentate gyrus in kainate-treated rats. J Comput Neurol 390:578–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teskey GC, Monfils MH, Silasi G, Kolb B (2006) Neocortical kindling is associated with opposing alterations in dendritic morphology in neocortical layer V and striatum from neocortical layer III. Synapse 59:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuff LP, Racine RJ, Adamec R (1983a) The effects of kindling on GABA-mediated inhibition in the dentate gyrus of the rat. I. Paired-pulse depression. Brain Res 277:79–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuff LP, Racine RJ, Mishra RK (1983b) The effects of kindling on GABA-mediated inhibition in the dentate gyrus of the rat. II. Receptor binding. Brain Res 277:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bohlen und Halbach O, Schulze K, Albrecht D (2004) Amygdala-kindling induces alterations in neuronal density and in density of degenerated fibers. Hippocampus 14:311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada JA, Sato M, Corcoran ME (1974) Persistent seizure susceptibility and recurrent spontaneous seizures in kindled cats. Epilepsia 15:465–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro K, Philpot BD (2008) Regulation of NMDA receptor subunit expression and its implications for LTD, LTP, and metaplasticity. Neuropharmacology 55:1081–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeberg BR, Feng W, Wang G, Wang MD, Fojo AT, Sunshine M, Narasimhan S, Kane DW, Reinhold WC, Lababidi S, Bussey KJ, Riss J, Barrett JC, Weinstein JN (2003) GoMiner: a resource for biological interpretation of genomic and proteomic data. Genome Biol 4:R28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XL, Sullivan JA, Moskal JR, Stanton PK (2008) A NMDA receptor glycine site partial agonist, GLYX-13, simultaneously enhances LTP and reduces LTD at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses in hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 55:1238–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.