Abstract

Effects of a traditional Japanese medicine, yokukansan, which is composed of seven medicinal herbs, on glutamate-induced cell death were examined using primary cultured rat cortical neurons. Yokukansan (10–300 μg/ml) inhibited the 100 μM glutamate-induced neuronal death in a concentration-dependent manner. Among seven constituent herbs, higher potency of protection was found in Uncaria thorn (UT) and Glycyrrhiza root (GR). A similar neuroprotective effect was found in four components (geissoschizine methyl ether, hirsuteine, hirsutine, and rhynchophylline) in UT and four components (glycycoumarin, isoliquiritigenin, liquiritin, and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid) in GR. In the NMDA receptor binding and receptor-linked Ca2+ influx assays, only isoliquiritigenin bound to NMDA receptors and inhibited the glutamate-induced increase in Ca2+ influx. Glycycoumarin and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid bound to NMDA receptors, but did not inhibit the Ca2+ influx. The four UT-derived components did not bind to NMDA receptors. The present results suggest that neuroprotective components (isoliquiritigenin, glycycoumarin, liquiritin, and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid in GR and geissoschizine methyl ether, hirsuteine, hirsutine, and rhynchophylline in UT) are contained in yokukansan, and isoliquiritigenin, which is one of them, is a novel NMDA receptor antagonist.

Keywords: Ca2+ influx, Glycyrrhiza root, Neuroprotection, NMDA receptor, Yokukansan

Introduction

Yokukansan is one of the traditional Japanese medicines called “kampo” medicines in Japan. It is composed of seven kinds of dried medical herbs. This medicine has been approved by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan as a remedy for neurosis, insomnia, and irritability in children. Recently, yokukansan was reported to improve behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), such as hallucinations, agitation, and aggressiveness in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and other forms of senile dementia (Iwasaki et al. 2005a, b; Mizukami et al. 2009; Monji et al. 2009).

Recently, various basic studies were performed to clarify the mechanism underlying the effect of yokukansan. When we investigated the effects of yokukansan using the thiamine-deficient (TD) rat, which is known as an animal model for neurodegenerative disorders (Langlais and Mair 1990; Langlais and Zhang 1993; Hazell et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2007), yokukansan ameliorated TD-induced memory disturbance, BPSD-like symptoms, extracellular glutamate increase in the thalamus, and degeneration of neuronal cells and astrocytes in the brain stem, cerebral cortex, and hippocampus (Ikarashi et al. 2009; Iizuka et al. 2010). Langlais and Zhang (1993) and Todd and Butterworth (2001) also demonstrated the increase in extracellular glutamate concentrations in vulnerable regions of the brain, such as the thalamus in TD. As a rational explanation for the increase in interstitial levels of glutamate in TD rats, Hazell et al. (2001) demonstrated a selective downregulation of the astrocyte glutamate transporters regulating the extracellular glutamate concentration. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the decrease in glutamate uptake into rat cortical astrocytes cultured in TD conditions was ameliorated by treatment with yokukansan, suggesting that yokukansan may exert a protective effect against the glutamate excitatory neurotoxicity by amelioration of the dysfunction of astrocytes (Kawakami et al. 2009, 2010). In addition, we demonstrated that yokukansan potently bound to NMDA receptors, in particular to its glutamate and glycine recognition sites (Kawakami et al. 2009). These findings suggest that yokukansan may have a neuroprotective effect as an NMDA-receptor antagonist in addition to glutamate transport activation in astrocytes.

In this study, therefore, the effects of yokukansan on glutamate-induced cell death were examined using primary cultured rat cortical neurons. Subsequently, effects of the seven constituent herbs of yokukansan on the cell death were investigated separately to clarify the relative importance of the constituent herbs. Finally, the effects of components isolated from a constituent herb having the highest potency were investigated to clarify the essential components.

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures were approved by the Laboratory Animal Committee of Tsumura & Co and met the guidelines of the Japanese Association for Laboratory Animal Science.

Drugs and Reagents

Yokukansan and Its Constituent Herbs

Yokukansan is composed of seven dried medicinal herbs: Atractylodis lancea rhizome (4.0 g, rhizome of Atractylodes lancea De Candolle), Poria sclerotium (4.0 g, sclerotium of Poria cocos Wolf), Cnidium rhizome (3.0 g, rhizome of Cnidium officinale Makino), Japanese Angelica root (3.0 g, root of Angelica acutiloba Kitagawa), Bupleurum root (2.0 g, root of Bulpleurum falcatum Linné), Glycyrrhiza root (1.5 g, root and stolon of Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisher), and Uncaria thorn (3.0 g, thorn of Uncaria rhynchophylla Miquel). The dry-powdered extracts of yokukansan and its seven constituent medicinal herbs were supplied by Tsumura & Co (Tokyo, Japan).

Components in Uncaria Thorn and Glycyrrhiza Root

Seven components (rhynchophylline, isorhynchophylline, corynoxeine, isocorynoxeine, hirsutine, hirsuteine, and geissoschizine methyl ether) in UT and eight components (liquiritin, liquiritinapioside, isoliquiritin, liquiritigenin, isoliquiritigenin, glycyrrhizin, 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, and glycycoumarin) in GR were supplied by the Botanical Raw Materials Research Department of Tsumura & Co (Ibaraki, Japan).

Reagents for Cell Culture

Neurobasal Medium with B27 supplement, Neurobasal Medium with B27 supplement minus AO, heat-inactivated horse serum, penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY, USA). Papaine was purchased from Worthington (Lakewood, NJ, USA). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), DNase I, and glutamate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Other chemicals were purchased from commercial sources.

Reagents for MTT Assay

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Dojindo (Kumamoto, Japan).

Reagents for Competitive Binding Assay

[3H]CGP-39653 (NET-1050, specific radioactivity: 50 Ci/mmol), was purchased from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA, USA). Tris, l-glutamic acid, and HEPES were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Other chemicals were purchased from commercial sources.

Reagents for Ca2+ Influx Assay

Fluo 4-AM, a loading buffer (20 mM HEPES, 115 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 13.8 mM glucose, 1.25 mM probencid, 0.04% Pluronic F-127, pH 7.4), and a recording buffer (20 mM HEPES, 115 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 3.8 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 13.8 mM glucose, 1.25 mM probencid, pH 7.4) were purchased from Dojindo. Other chemicals were purchased from commercial sources.

Primary Culture of Rat Cortical Neurons

Primary culture was performed according to the methods of Arimatsu and Hatanaka (1986) and Perry et al. (2004) with minor modification. In brief, neopallia of 18-day-old Sprague–Dawley rat embryos (Charles River Laboratories, Yokohama, Japan) were dissociated with 9 units/ml papaine and 0.01% DNase I at 37°C for 15 min. The dissociation was terminated by addition of heat-inactivated horse serum, and the tissue fragments were centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in DMEM Ca- and Mg-free phosphate-buffered saline [PBS(−)] (1:1) and then mechanically disrupted by pipetting. The cell suspension was passed through lens paper to remove possible cell clumps. The cells were resuspended in Neurobasal Medium with B27 supplement and seeded onto poly-d-lysine-coated 96-well plates (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at a density of 105 cells/cm2 for 24 h, then the medium was changed to Neurobasal Medium with B27 supplement minus AO for 3 week. The purity of neurons in the culture was examined by an immunocytochemical stain using monoclonal antibody cocktail (MAB2300X, Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA), which reacts against key somatic, nuclear, dendritic, and axonal proteins distributed across the pan-neuronal architecture. We confirmed that at least 95% of cells were neurons. These results are consistent with that of previous report (Perry et al. 2004).

The effects of test substances on glutamate-induced cell death were evaluated by placing with medium, including a fixed concentration (100 μM) of glutamate plus various concentrations of test substances. After incubation for 24 h, the survival of cells was evaluated by a MTT reduction assay.

MTT Reduction Assay

The MTT reduction assay (Sakai et al. 1994) was performed as follows: About 20 μl of 5 mg/ml MTT dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added into each individual well and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of solubilization solution (10% SDS in 0.01 N HCl), and the blue formazan formed from MTT by the reaction was dissolved by additional incubation for 18 h at 37°C. Absorbance of the formazan solution was measured using a microplate reader at a test wavelength of 540 nm and a reference wavelength of 690 nm.

Competitive Binding to NMDA Receptors

Competitive binding of seven UT-derived components and eight GR-derived components to NMDA receptors was assayed on the glutamate recognition sites (Kawakami et al. 2009). The membrane fraction prepared from rat cerebral cortex was used for the binding assay. In brief, the cortex was dissected from brains of normal male Wistar rats (175 ± 25 g body weight) after decapitation and immediately homogenized in 20 volumes of ice-cold 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) using a Polytron homogenizer. After the pellets were washed by resuspension in the buffer and subsequent centrifugation (20 min, 48,000 × g), the final pellet (membrane) was suspended in 20 volumes of the buffer.

In the binding assay, 500 μl of the membrane suspension (2.5 mg) was incubated in duplicate with 20 μl of 2.0 nM [3H]CGP-39653 and 5.25 μl of various concentrations of each test compound at 4°C for 20 min. To define nonspecific binding, 1,000 μM l-glutamic acid was used. After incubation, the receptor–ligand complexes were isolated by rapid filtration through a Whatman GF/B filter using a Cell Harvester (Brandel MLR-48, Skatron Micro-96, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The trapped radioactive complex was washed four times by 3 ml of ice-cold 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer and dried. Radioactivity (counts per minute, cpm) trapped on the dried filter was measured by a liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer).

The specific binding was defined by subtracting nonspecific binding from total binding and expressed as the percentage inhibition using the following formula: Inhibition (%) = [1 − (c − a)/(b − a)] × 100, where a is the average cpm of nonspecific binding, b is the average cpm of total binding, and c is cpm in the presence of the test substance.

Measurement of Ca2+ Influx in Neurons

Intracellular fluorescent Ca2+ in cultured cortical neurons was measured using Fluo 4-AM in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions in 96-well black microplates (poly-d-lysine coated, BD Falcon) (Cho et al. 2010; Hemstapat et al. 2004). In brief, cultures grown 14–17 days in 96-well plates were loaded with 5 μM Fluo 4-AM in loading buffer for 60 min at 37°C. Loading was terminated by removing the loading buffer, and the recording buffer was added to each well. Then, a recording buffer containing glutamate or NMDA plus the test substance was added to the same well. Fluorescence intensity was determined at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 518 nm, respectively, using the Infinite M200 plate reader (Tecan, Grödig, Austria). Fluorometric data were collected before (control) and after addition of glutamate and the test substance to the same well. Blank intensity data were also determined in the experimental condition without cultured cells. The specific Fluo-4 fluorescence intensity (SI) in a test substance–treated sample or control was defined by subtracting the corresponding blank intensity. The effect of a test substance on glutamate or NMDA-induced Ca2+ influx into neurons was expressed as relative fluorescence intensity in relation to the control: fluorescence ratio of control = test substanceSI/controlSI.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. The statistical significance of differences between groups was assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Scheffé’s post hoc test. The significance level in each statistical analysis was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

Glutamate-Induced Neuronal Death

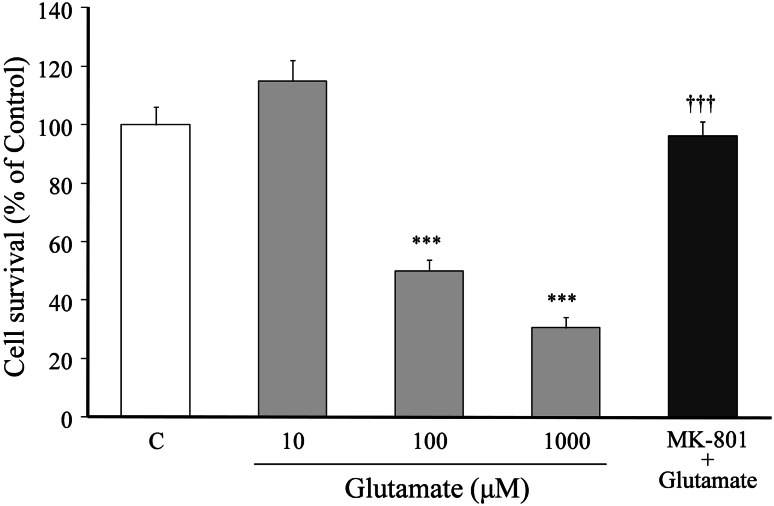

The relationship between glutamate concentration and neuronal death is shown in Fig. 1. Cell survival was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner by increasing medium glutamate concentrations (i.e., glutamate concentration-dependently induced cell death). The concentration of glutamate that induced 50% cell death was 100 μM. The 100 μM glutamate-induced cell death was completely inhibited by co-treatment with 20 μM MK-801.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between glutamate concentration and neuronal death. Primary cultured neurons were incubated for 24 h in the medium containing various concentrations (10–1,000 μM) of glutamate or 100 μM glutamate + MK-801 (20 μM). The medium for the control did not contain glutamate. Each value calculated as percentage of the MTT activity in control cells is represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ***P < 0.001 versus control (C), and ††† P < 0.001 versus 100 μM glutamate (G): one-way ANOVA + Scheffé’s test

Effect of Yokukansan on Glutamate-Induced Neuronal Death

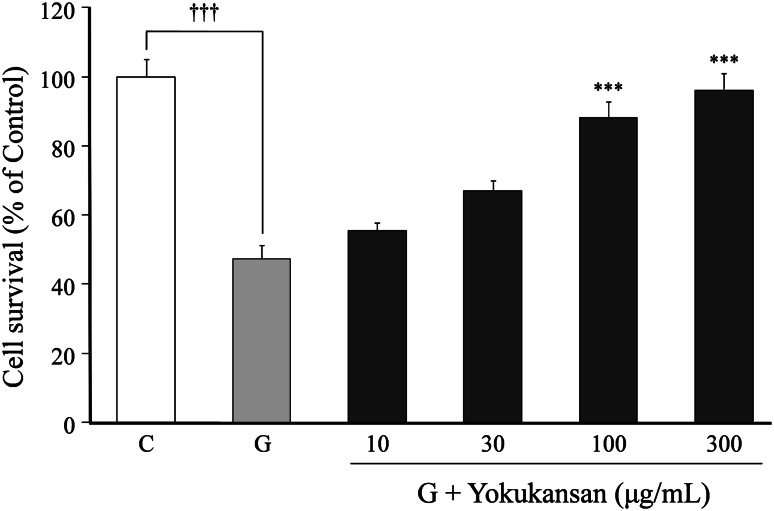

Effects of yokukansan on the 100 μM glutamate-induced cell death are shown in Fig. 2. Yokukansan (10–300 μg/ml) inhibited the glutamate-induced cell death in a concentration-dependent manner. Significant inhibition was observed at 100 μg/ml and higher concentrations.

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory effects of yokukansan on 100 μM glutamate-induced cell death. Primary cultured neurons were incubated for 24 h in the medium containing 100 μM glutamate or 100 μM glutamate + various concentrations (10–300 μg/ml) of yokukansan. The control medium did not contain glutamate. Each value calculated as a percentage of the MTT activity in control cells is represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ***P < 0.001 versus control (C) and ††† P < 0.001 versus glutamate (G): one-way ANOVA + Scheffé’s test

Effects of Constituent Herbs on Glutamate-Induced Neuronal Death

The effects of seven constituent herbs (Atractylodis lancea rhizome, Poria sclerotium, Cnidium rhizome, UT, Japanese Angelica root, Bupleurum root, and GR) of yokukansan on the 100 μM glutamate-induced cell death were examined at a fixed concentration of 20 μg/ml (Fig. 3). UT and GR had the most potent protective effect, and followed by Atractylodis lancea rhizome. No protective effects were observed for Poria sclerotium, Cnidium rhizome, Japanese Angelica root, and Bupleurum root.

Fig. 3.

Effects of seven constituent herbs of yokukansan on glutamate-induced neuronal death. Primary cultured neurons were incubated for 24 h in the medium containing 100 μM glutamate or 100 μM glutamate + one constituent herb (20 μg/ml): Atractylodis lancea rhizome (ALR), Poria sclerotium (PS), Cnidium rhizome (CR), Uncaria thorn (UT), Japanese Angelica root (JAR), Bupleurum root (BR), or Glycyrrhiza root (GR). The control medium did not contain glutamate. Each value calculated as a percentage of the MTT activity in control cells is represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ††† P < 0.001 versus control (C) and **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus glutamate (G): one-way ANOVA + Scheffé’s test

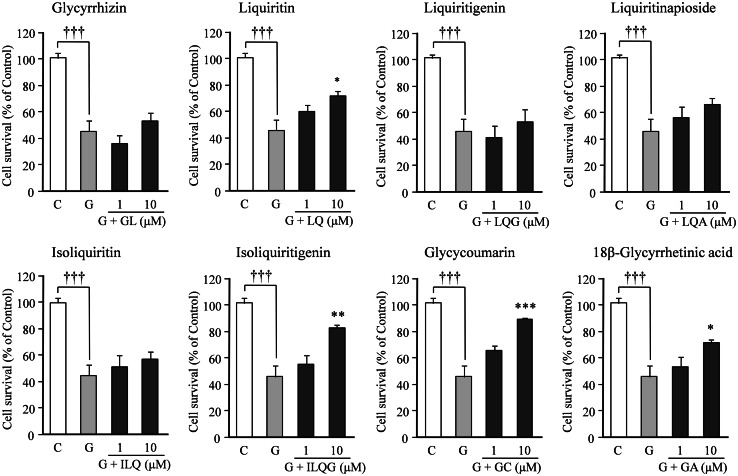

Effects of Seven UT-Derived Components and Eight GR-Derived Components on Glutamate-Induced Neuronal Death

The effects of seven UT-derived components on the 100 μM glutamate-induced cell death were examined at concentrations of 1 and 10 μM (Fig. 4). Hirsutine, hirsuteine, and geissoschizine methyl ether had the most potent protective effects, and followed by rhynchophylline. No significant protective effects were observed for isorhynchophylline, corynoxeine, and isocorynoxeine.

Fig. 4.

Effects of seven components of UT on glutamate-induced neuronal death. Primary cultured neurons were incubated for 24 h in medium containing 100 μM glutamate or 100 μM glutamate + one component (1 or 10 μM): rhynchophylline (RP), isorhynchophylline (IRP), corynoxeine (CX), isocorynoxeine (ICX), hirsuteine (HTE), hirsutine (HTI), or geissoschizine methyl ether (GM). The control medium did not contain glutamate. Each value calculated as a percentage of the MTT activity in control cells is represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ††† P < 0.001 versus corresponding control (C), **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus glutamate (G): one-way ANOVA + Scheffé’s test

The effects of eight GR-derived components on the 100 μM glutamate-induced cell death were also examined at concentrations of 1 and 10 μM (Fig. 5). The most potent protective effect was found in glycycoumarin, isoliquitigenin, and followed by 18β-glycyrretinic acid and liquiritin. No significant protective effects were observed for the other four components, such as glycyrrhizin, isoliquiritin, liquiritigenin, and liquiritinapioside.

Fig. 5.

Effects of eight components of GR on glutamate-induced neuronal death. Primary cultured neurons were incubated for 24 h in the medium containing 100 μM glutamate or 100 μM glutamate + one component (1 or 10 μM): glycyrrhizin (GL), liquiritin (LQ), liquiritigenin (LQG), liquiritinapioside (LQA), isoliquiritin (ILQ), isoliquitigenin (ILQG), glycycoumarin (GC), or 18β-glycyrretinic acid (GA). The control medium did not contain glutamate. Each value calculated as a percentage of the MTT activity in control cells is represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ††† P < 0.001 versus corresponding control (C), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus glutamate (G): one-way ANOVA + Scheffé’s test

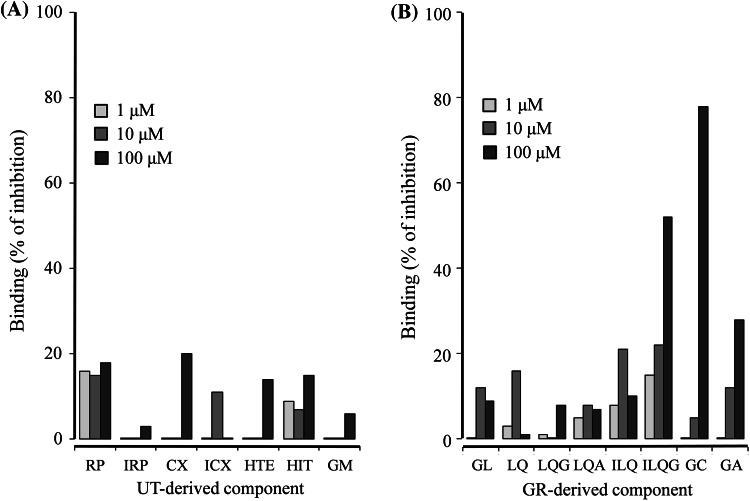

Binding of Seven UT-Derived Components and Eight GR-Derived Components to NMDA Receptors

The competitive binding assays of seven UT-derived components and eight GR-derived components to NMDA receptors were performed at the concentration range of 1.0–100 μM (Fig. 6). The seven UT-derived components did not bind to NMDA receptors (Fig. 6a). On the other hand, three of the eight GR-derived components, isoliquitigenin, glycycoumarin, and 18β-glycyrretinic acid, bound NMDA receptors in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Competitive binding of UT- (a) and GR-derived components (b) to glutamate recognition sites in NMDA receptors. The membrane fraction of the rat cerebral cortex was used for the binding assay. Binding of each component (1–100 μM) is expressed as percentage inhibition of each component against the total specific binding of a radioligand ([3H]CGP-39653) to glutamate binding site. Each value is expressed as the mean of duplicate determinations. UT-derived components were rhynchophylline (RP), isorhynchophylline (IRP), corynoxeine (CX), isocorynoxeine (ICX), hirsuteine (HTE), hirsutine (HTI), and geissoschizine methyl ether (GM). GR-derived components were glycyrrhizin (GL), liquiritin (LQ), liquiritigenin (LQG), liquiritinapioside (LQA), isoliquiritin (ILQ), isoliquitigenin (ILQG), glycycoumarin (GC), and 18β-glycyrretinic acid (GA)

Effects of GR-Derived Components on Glutamate-Induced Increase in Ca2+ Influx

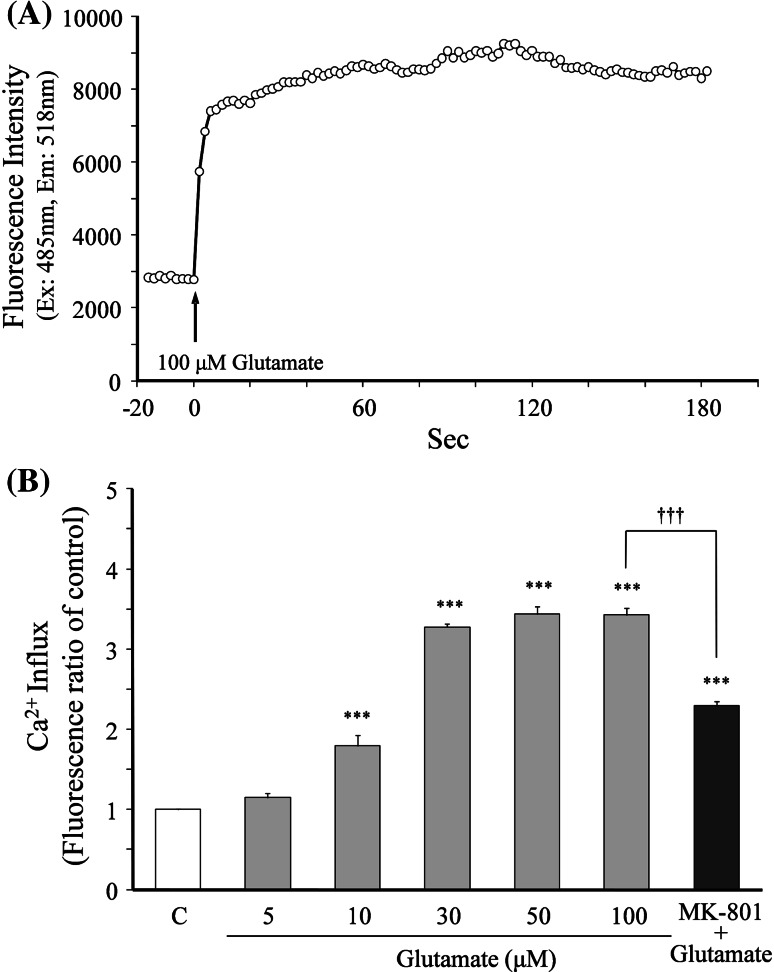

Prior to evaluation of the effects of various components on the glutamate-induced increase in Ca2+ influx, the optimal concentration of glutamate for induction of Ca2+ influx in neurons was examined (Fig. 7). Figure 7a shows the typical time–response curve of Ca2+ influx into neurons after 100 μM glutamate was added to the recording buffer. The Ca2+ influx level increased rapidly after the addition of glutamate, and the increased level reached a maximum within 60 s. The maximum level was maintained for at least 180 s (3 min) thereafter. Evaluation of the effects of the glutamate concentration (5–100 μM) on the Ca2+ level at 3 min showed that the Ca2+ influx increased in a concentration-dependent manner, and the increased level reached a plateau (maximum) at 30 μM and higher concentrations (Fig. 7b). The 100 μM glutamate-induced increase in Ca2+ influx was inhibited by 20 μM MK-801. Thus, 100 μM glutamate was selected as the optimal concentration to obtain the maximum response.

Fig. 7.

Glutamate-induced increase in Ca2+ influx. Intracellular fluorescent Ca2+ in cultured cortical neurons was measured using Fluo 4 as an indicator. a A typical time–response curve of fluorescence intensity in neurons after 100 μM glutamate was added to the recording buffer. Glutamate was added by an automated dispenser. Fluorescence measurements were taken at 2 s intervals for a total elapsed time of 200 s. b The relationship between the glutamate concentration and Ca2+ influx. The Ca2+ influx induced by glutamate (5–100 μM) was compared at 3 min after addition of glutamate. Each value is represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ***P < 0.001 versus control (C), and ††† P < 0.001 versus 100 μM glutamate: one-way ANOVA + Scheffé’s test

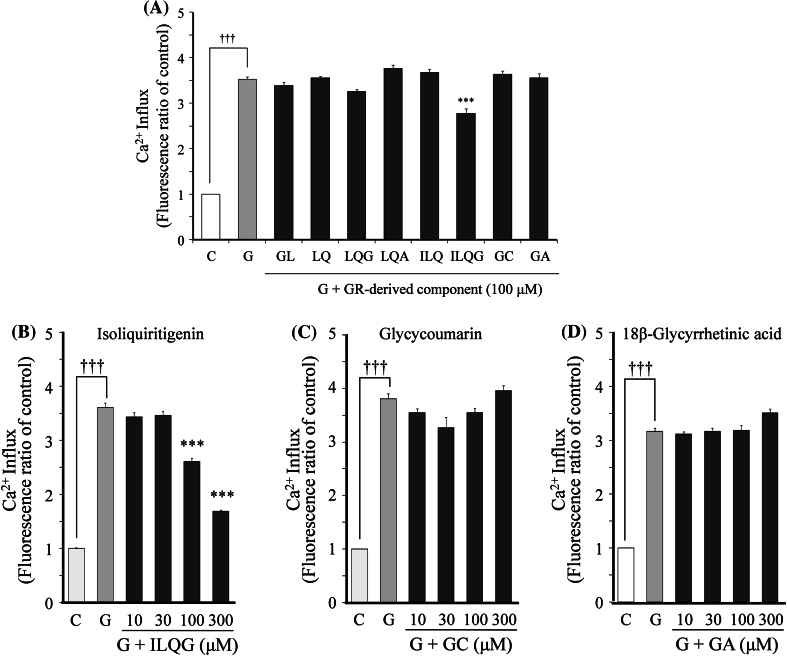

The effects of eight GR-derived components on the 100 μM glutamate-induced increases in Ca2+ influx were examined at a fixed concentration of 100 μM (Fig. 8a). Significant inhibition was found only by isoliquiritigenin, but not by glycycoumarin and 18β-glycyrretinic acid, which bind NMDA receptors. Isoliquiritigenin (10–300 μM) inhibited the increased Ca2+ influx in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 8b). This concentration-dependent inhibition was not observed for both glycycoumarin (Fig. 8c) and 18β-glycyrretinic acid (Fig. 8d).

Fig. 8.

Effects of GR-derived components on glutamate-induced increase in Ca2+ influx. a The effects of eight components on 100 μM glutamate-induced Ca2+ influx. b–d The effects of concentration of isoliquiritigenin, glycycoumarin, and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid on the glutamate-induced increase in Ca2+ influx. The effect of each component on the Ca2+ influx was evaluated at 3 min after addition of glutamate. Each value expressed as the fluorescence ratio of the control is represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ††† P < 0.001 versus control (C) and ***P < 0.001 versus glutamate (G): one-way ANOVA + Scheffé’s test. Glycyrrhiza root-derived components were glycyrrhizin (GL), liquiritin (LQ), liquiritigenin (LQG), liquiritinapioside (LQA), isoliquiritin (ILQ), isoliquitigenin (ILQG), glycycoumarin (GC), and 18β-glycyrretinic acid (GA)

Effects of Isoliquiritigenin on NMDA-Induced Increase in Ca2+ Influx

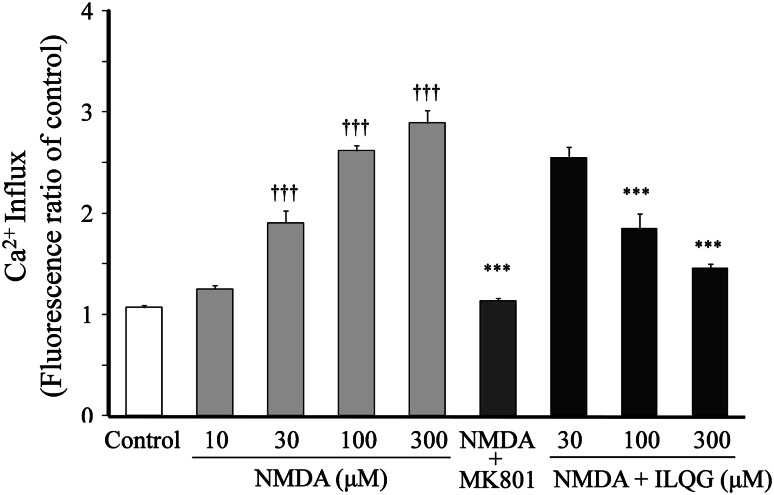

The effects of isoliquiritigenin on NMDA-induced increase in Ca2+ influx are shown in Fig. 9. NMDA (10–300 μM) increased the Ca2+ influx in a concentration-dependent manner. The 300 μM NMDA-induced increase in Ca2+ influx was completely inhibited by 1.0 μM MK-801. Isoliquiritigenin (30–300 μM) inhibited the increased Ca2+ influx in a concentration-dependent manner.

Fig. 9.

Effects of isoliquilitigenin (ILQG) on NMDA-induced increase in Ca2+ influx. The Ca2+ influx was measured using Fluo 4 as an indicator. The Ca2+ influx induced by NMDA (10–300 μM) was compared at 3 min after addition of NMDA. The effects of MK-801 (1 μM) and ILQG (30–300 μM) on the Ca2+ influx induced by NMDA were evaluated at 3 min after addition of 300 μM NMDA. Each value expressed as the fluorescence ratio of the control is represented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ††† P < 0.001 versus control and ***P < 0.001 versus NMDA (300 μM): one-way ANOVA + Scheffé’s test

Discussion

Glutamate is a neurotransmitter in glutamatergic neurons. Increase in excessive concentration of extracellular glutamate induces excitatory neurotoxicity. Astrocytes glutamate transporters regulate or protect the glutamate-induced neuronal death by uptake of the extracellular glutamate. We previously demonstrated that yokukansan possessed a neuroprotective effect against the glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity because of not only amelioration of dysfunction of astrocytes but also direct protection of neuronal cells (Kawakami et al. 2009). It has been suggested that some factors, such as glutamate receptor and cystines/glutamate antiporter system (System Xc−), are related to the direct protection against neurons (Schubert et al. 1992; Froissard and Duval 1994; Edwards et al. 2007). Neuronal cells have both glutamate receptors and System Xc−, but PC12 cells have only the System Xc−, suggesting that PC12 cell is a good tool for selective evaluation of test substances against oxidative stress, which is related to the System Xc− (Schubert et al. 1992; Froissard and Duval 1994; Edwards et al. 2007). Recently, we demonstrated that yokukansan inhibited the glutamate-induced PC12 cell death (Kawakami et al. 2011). When the effects of the seven constituents of yokukansan on the cell death were further examined, the highest potency of protective effect was found in UT, and followed by GR (Kawakami et al. 2011). Those protective effects were found in hirsutine, hirsuteine, and geissoschizine methyl ether, which also ameliorated a glutamate-induced decrease in the glutathione (GSH) level (Kawakami et al. 2011), suggesting that these components have protective effect that is not through glutamate receptors. However, the effects of yokukansan on glutamate receptor–mediated neuronal cell death remain unclear. In this study, therefore, we first examined the effects of yokukansan on glutamate-induced cell death using cultured neurons. As shown in Fig. 1, the cell death rate was increased by glutamate in a concentration-dependent manner, and it was completely inhibited by the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801. These results suggest that the neuronal cell death caused by the glutamate in this study is different from those in the PC12 cell experiment, i.e., NMDA receptors in addition to the System Xc−, at least, relates to the cell death in neurons. Yokukansan protected glutamate-induced neuronal death (Fig. 2), suggesting that yokukansan contains active components for neuroprotection.

To clarify the essential component of yokukansan activity, we next examined the effects of the seven constituent herbs of yokukansan on glutamate-induced cell death and found that UT and GR possessed higher potency than other constituent herbs (Fig. 3). Further experiments to clarify the active compounds showed that four components (geissoschizine methyl ether, hirsuteine, hirsutine, and rhynchophylline) in UT (Fig. 4) and four components (glycycoumarin, isoliquiritigenin, liquiritin, and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid) in GR (Fig. 5) possessed higher potency for the neuroprotection at 10 μM concentration. This concentration is 3–50 times of those (0.014~0.246%) that were included in yokukansan (Hatano et al. 1991; Sakakibara et al. 1998; Ma et al. 2005; Kondo et al. 2007). The protective effect at lower concentrations was examined (0.001~0.1 μM), but no protection effect was observed in these concentrations. Therefore, the neuroprotective effect of yokukansan might be attributed to the synergistic effects of these active components rather than the effect of single active component.

We previously demonstrated that yokukansan potently bound to NMDA receptors (Kawakami et al. 2009). Therefore, we examined whether eight components showing neuroprotective effect have the binding to NMDA receptors. The competitive binding study showed that glycycoumarin, isoliquiritigenin, and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid in GR bound NMDA receptors, but the other GR-derived components and the seven UT-derived components did not (Fig. 6). To verify the results in this receptor-binding assay, we further examined the effects of GR components that showed NMDA receptor binding on Ca2+ influx into neurons. As expected (Lysko et al. 1989; Michaels and Rothman 1990), glutamate increased the Ca2+ influx into neurons, and the increased Ca2+ influx was inhibited by MK-801 (Fig. 7), suggesting that the present experimental condition was appropriate for evaluation of NMDA receptor-linked Ca2+ influx. Isoliquiritigenin clearly inhibited the glutamate-induced increase in Ca2+ influx, but two components (glycycoumarin and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid) showing NMDA receptor binding did not inhibit it (Fig. 8). As described already, we previously demonstrated that yokukansan potently bound to NMDA receptors (Kawakami et al. 2009). This previous binding data to NMDA receptors may be because of the sum including some components such as glycycoumarin and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, which were not linked to Ca2+ influx. Glutamate acts not only on NMDA receptors but also on metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) and AMPA receptors, which are expressed in culture murine cortical neurons, suggesting that these receptors influence NMDA receptor–mediated neuronal death (Bruno et al. 1995). We confirmed in preliminary study that isoliquiritigenin did not bind to mGluRs and AMPA receptors. In addition to these findings, we directly examined the effect of isoliquiritigenin on Ca2+-influx induced by a specific NMDA receptor ligand, NMDA, to confirm specificity of isoliquiritigenin against NMDA receptors (Fig. 9). Isoliquiritigenin inhibited NMDA-induced Ca2+-influx, suggesting that this component is a NMDA antagonist. Because the concentration (100 and 300 μM) for both NMDA-binding property and Ca2+-influx inhibition of isoliquiritigenin was higher than that (10 μM) for neuroprotection, it is difficult to explain the neuroprotective effect of yokukansan by NMDA antagonistic effect. However, this is the first evidence demonstrating that isoliquiritigenin has an inhibiting effect to NMDA receptors.

We previously demonstrated that hirsutine, hirsuteine, and geissoschizine methyl ether showing neuroprotective effects in this study ameliorated glutamate-induced decrease in GSH (Kawakami et al. 2011). Therefore, the neuroprotective effect observed in this study might also be because of anti-oxidative effects, though further investigation is necessary in the future.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that neuroprotective components (isoliquiritigenin, glycycoumarin, liquiritin, and 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid in GR and geissoschizine methyl ether, hirsuteine, hirsutine, and rhynchophylline in UT) are contained in yokukansan, and isoliquiritigenin, which is one of them, is a novel NMDA receptor antagonist.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Arimatsu Y, Hatanaka H (1986) Estrogen treatment enhances survival of cultured fetal rat amygdala neurons in a defined medium. Brain Res 391:151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno V, Copani A, Knöpfel T, Kuhn R, Casabona G, Dell’Albani P, Condorelli DF, Nicoletti F (1995) Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors coupled to inositol phospholipid hydrolysis amplifies NMDA-induced neuronal degeneration in cultured cortical cells. Neuropharmacology 34:1089–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SC, Rhim JH, Son YH, Lee SJ, Park SC (2010) Suppression of ROS generation by 4, 4-diaminodiphenylsulfone in non-phagocytic human diploid fibroblasts. Exp Mol Med 42:223–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MA, Loxley RA, Williams AJ, Connor M, Phillips JK (2007) Lack of functional expression of NMDA receptors in PC12 cells. Neurotoxicology 28:876–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froissard P, Duval D (1994) Cytotoxic effects of glutamic acid on PC12 cells. Neurochem Int 24:485–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano T, Fukuda T, Liu YZ, Noro T, Okuda T (1991) Phenolic constituents of licorice. IV. Correlation of phenolic constituents and licorice specimens from various sources, and inhibitory effects of licorice extracts on xanthine oxidase and monoamine oxidase. Yakugaku Zasshi 111:311–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell AS, Rao KV, Danbolt NC, Pow DV, Butterworth RF (2001) Selective down-regulation of the astrocyte glutamate transporters GLT-1 and GLAST within the medial thalamus in experimental Wernicke’s encephalopathy. J Neurochem 78:560–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemstapat K, Smith MT, Monteith GR (2004) Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ in cultured rat embryonic hippocampal neurons using a fluorescence microplate reader: potential application to biomolecular screening. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 49:81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka S, Kawakami Z, Imamura S, Yamaguchi T, Sekiguchi K, Kanno H, Ueki T, Kase Y, Ikarashi Y (2010) Electron-microscopic examination of effects of yokukansan, a traditional Japanese medicine, on degeneration of cerebral cells in thiamine-deficient rats. Neuropathology 30:524–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikarashi Y, Iizuka S, Imamura S, Yamaguchi T, Sekiguchi K, Kanno H, Kawakami Z, Yuzurihara M, Kase Y, Takeda S (2009) Effects of yokukansan, a traditional Japanese medicine, on memory disturbance and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in thiamine-deficient rats. Biol Pharm Bull 32:1701–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K, Satoh-Nakagawa T, Maruyama M, Monma Y, Nemoto M, Tomita N, Tanji H, Fujiwara H, Seki T, Fujii M, Arai H, Sasaki H (2005a) A randomized, observer-blind, controlled trial of the traditional Chinese medicine Yi-Gan San for improvement of behavioral and psychological symptoms and activities of daily living in dementia patients. J Clin Psychiatry 66:248–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K, Maruyama M, Tomita N, Furukawa K, Nemoto M, Fujiwara H, Seki T, Fujii M, Kodama M, Arai H (2005b) Effects of the traditional Chinese herbal medicine Yi-Gan San for cholinesterase inhibitor-resistant visual hallucinations and neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. J Clin Psychiatry 66:1612–1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Z, Kanno H, Ueki T, Terawaki K, Tabuchi M, Ikarashi Y, Kase Y (2009) Neuroprotective effects of yokukansan, a traditional Japanese medicine, on glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity in cultured cells. Neuroscience 159:1397–1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Z, Ikarashi Y, Kase Y (2010) Glycyrrhizin and its metabolite 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid in glycyrrhiza, a constituent herb of yokukansan, ameliorate thiamine deficiency-induced dysfunction of glutamate transport in cultured rat cortical astrocytes. Eur J Pharmacol 626:154–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Z, Kanno H, Ikarashi Y, Kase Y (2011) Yokukansan, a kampo medicine, protects against glutamate cytotoxicity due to oxidative stress in PC12 cells. J Ethnopharmacol 134:74–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K, Shiba M, Nakamura R, Morota T, Shoyama Y (2007) Constituent properties of licorices derived from Glycyrrhiza uralensis, G. glabra, or G. inflata identified by genetic information. Biol Pharm Bull 30:1271–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlais PJ, Mair RG (1990) Protective effects of glutamate antagonist MK801 on pyrithiamine-induced lesions and amino acid changes in rat brain. J Neurosci 10:1664–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlais PJ, Zhang SX (1993) Extracellular glutamate is increased in thalamus during thiamine deficiency-induced lesions and is blocked by MK-801. J Neurochem 61:2175–2182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysko PG, Cox JA, Vigano MA, Henneberry RC (1989) Excitatory amino acid neurotoxicity at the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor in cultured neurons: pharmacological characterization. Brain Res 499:258–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma CJ, Li GS, Zhang DL, Liu K, Fan X (2005) One step isolation and purification of liquiritigenin and isoliquiritigenin from Glycyrrhiza uralensis Risch. using high-speed counter-current chromatography. J Chromatogr A 1078:188–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels RL, Rothman SM (1990) Glutamate neurotoxicity in vitro: antagonist pharmacology and intracellular calcium concentrations. J Neurosci 10:283–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizukami K, Asada T, Kinoshita T, Tanaka K, Sonohara K, Nakai R, Yamaguchi K, Hanyu H, Kanaya K, Takao T, Okada M, Kudo S, Kotoku H, Iwakiri M, Kurita H, Miyamura T, Kawasaki Y, Omori K, Shiozaki K, Odawara T, Suzuki T, Yamada S, Nakamura Y, Toba K (2009) A randomized cross-over study of a traditional Japanese medicine (kampo), yokukansan, in the treatment of the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 12:191–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monji A, Takita M, Samejima T, Takaishi T, Hashimoto K, Matsunaga H, Oda M, Sumida Y, Mizoguchi Y, Kato T (2009) Effect of yokukansan on the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neuropharmacol Biol Psychiatry 33:308–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SW, Norman JP, Litzburg A, Gelbard HA (2004) Antioxidants are required during the early critical period, but not later, for neuronal survival. J Neurosci Res 78:485–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai M, Miyazaki A, Hakamata H, Sasaki T, Yui S, Yamazaki M, Shichiri M, Horiuchi S (1994) Lysophosphatidylcholine plays an essential role in the mitogenic effect of oxidized low density lipoprotein on murine macrophages. J Biol Chem 269:31430–31435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara I, Takahashi H, Terabayashi S, Yuzurihara M, Kubo M, Higuchi M, Ishige A, Komatsu Y, Maruno M, Okada M (1998) Chemical and pharmacological evaluations of Chinese crude drug “Gou-teng”. Natural Medicines 52:353–359 [Google Scholar]

- Schubert D, Kimura H, Maher P (1992) Growth factors and vitamin E modify neuronal glutamate toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:8264–8267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd KG, Butterworth RF (2001) In vivo microdialysis in an animal model of neurological disease: thiamine deficiency (Wernicke) encephalopathy. Methods 23:55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang B, Fan Z, Shi X, Ke Z, Luo J (2007) Thiamine deficiency induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in neurons. Neuroscience 144:1045–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]