Abstract

Glutamate, one of the major neurotransmitters in the central nervous system, is released into the synaptic spaces and bound to the glutamate receptors which facilitate normal synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, and brain development. Past studies have shown that glutamate with high concentration is a potent neurotoxin capable of destroying neurons through many signal pathways. In this research, our main purpose was to determine whether the specific soluble guanylyl cyclase activator YC-1 (3-(5′-hydroxymethyl-2′-furyl)-1-benzyl indazole) had effect on glutamate-induced apoptosis in cultured PC12 cells. The differentiated PC12 cells impaired by glutamate were used as the cell model of excitability, and were exposed to YC-1 or/and ODQ (1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one) with gradient concentrations for 24 h. MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl) assay was used to detect the cellular viability. Radioimmunoassay (RIA) was used to detect the cGMP (cyclic guanosine monophosphate) concentrations in PC12 cells. Hoechst 33258 staining and flow cytometric analysis were used to detect the cell apoptosis. The cellular viability was decreased and the apoptotic rate was increased when PC12 cells were treated with glutamate. Cells treated with YC-1 or/and ODQ showed no significant differences in the cell viability and intracellular cGMP levels compared with those of control group. The specific soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) inhibitor ODQ showed an inhibitory effect on cGMP level and aggravated the apoptosis of PC12 cells induced by glutamate. YC-1 elevated cGMP level thus decreased PC12 cell apoptosis induced by glutamate, but this effect could be reversed by ODQ. These results revealed that YC-1 might attenuate glutamate-induced PC12 cell apoptosis via a sGC–cGMP involved pathway.

Keywords: YC-1, Glutamate, ODQ, PC12cell, Apoptosis

Introduction

Glutamate, an excitatory amino acid, is one of the major neurotransmitters in the central nervous system (CNS). Glutamate is released into the synaptic spaces and binded to the glutamate receptors which facilitate normal synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, and brain development (Bleich et al. 2003; Conn 2003). However, excessive activation of glutamate receptors, particularly the N-methyl-daspartic acid (NMDA) receptor subtype, leads to the neuronal cell death (Choi and Rothman 1990). High concentrations of glutamate can accumulate in the brain and are thought to be involved in the etiology of a number of neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s disease (Coyle and Puttfarcken 1993; Lipton and Rosenberg 1994). A number of in vitro studies indicated that at high concentrations, glutamate was a potent neurotoxin capable of destroying neurons by apoptosis (Froissard and Duval 1994; Gerstner et al. 2009). Researchers have demonstrated several mechanisms by which glutamate initiates neurotoxicity such as the activation of calcium-dependent enzymes (Ankarcrona et al. 1996), nitric oxide synthase (NOS) (Dawson et al. 1996), and mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species (Urushitani et al. 2001), which initiate the neuronal cell death.

Guanylyl cyclase (GC) is an enzyme that synthesizes cGMP from GTP. There are two isoforms of GC, a membrane-bound form of GC called particulate guanylyl cyclase (pGC) that can be activated by natriuretic peptide (NP). The sGC is expressed in the cytoplasm of a large number of mammalian cells, and this isoform is mainly presented in cells of CNS, which can be directly activated by NO. Although NO was found to cause toxicity at the higher concentrations, many researches showed that it had neuroprotective effect when its concentration is low in certain kinds of cells, including PC12 cells, motor neurons and rat dorsal root ganglion neurons through a sGC–cGMP involved signal pathway (Estevez et al. 1998; Farinelli et al. 1996; Kim et al. 1999; Thippeswamy and Morris 1997).

PC 12 cell is a cell line derived from a rat adrenal medulla pheochromocytoma. The differentiated PC12 cells induced by nerve growth factor (NGF) have the typical characteristic of the neurons in form and function, and therefore are widely used as a model in vitro for the neuron research, such as the apoptosis and the differentiation of neurons (Greene, 1978; Ishima et al. 2008; Rukenstein et al. 1991). It has been reported that there were both sGC and pGC in PC12 cells. The increase of cGMP was found in both intracellular and extracellular levels when exposed to the NO donor sodium nitroprusside or the natruretic peptide (Fiscus et al. 1987).

YC-1, originally characterized as a potent sGC activator in platelets, is a specific sGC activator. It can make NO a far more potent activator of sGC (Hoenicka et al. 1999). In this study, YC-1 was used as the specific activator of sGC to elevate the cGMP levels of PC12 cells. We are going to determine whether YC-1 can decrease glutamate-induced PC12 cell apoptosis and whether sGC activity and elevation of the cGMP level are involved in regulating apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Materials

RPMI 1640 cell culture medium was purchased from GIBCO Invitrogen. MTT, NGF, glutamate, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), horse serum and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were all purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA. YC-1 and ODQ were purchased from Cayman. Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis detection kit was from Bipec Biopharma Corporation, USA. 125I-cGMP radioimmunoassay kit was purchased from Shanghai University of Chinese Medicine Isotope Room. Plastic culture microplates and flasks used in the experiment were supplied by Corning Incorporated (Costar, Corning, NY, USA).

Cell Culture

PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cells were obtained from Institute of Basic Medical Sciences Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. The cells were kept on plastic culture micro plates with RPMI 1640 (pH 7.4) supplemented with 5% FBS and 10% horse serum. In the presence of NGF, PC12 cells would differentiate into sympathetic-like neurons, the medium was then replaced to serum-free RPMI 1640 supplemented with 50 ng/ml NGF. The cells were cultured with the medium (with NGF) for 7 days, including changes every other day until the neurites were removed. Then the cells were cultured with the medium containing 10% FBS. All medium included 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 U/ml streptomycin. Cultures were propagated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Cell Viability Assay

The cell viability was assessed by using the MTT assay, which was based on the reduction of the dye MTT to formazan crystals, an insoluble intracellular blue product, by cellular dehydrogenases (Denizot and Lang 1986). Cells were seeded on 96-wells plates with 1 × 104 cells in 200 μl medium per well and cultured 24 h for stabilization. At the end of the exposure, 20 μl MTT was added to each well into a final concentration of 2 mg/ml and afterwards the cells were cultured for 4 h at 37°C. The medium was then removed carefully and 150 μl DMSO was added in and mixed with the cells thoroughly until formazan crystals were dissolved completely. This mixture was measured in an ELISA reader (Elx 800, Bio-TEK, USA) with a wave length of 490 nm. Experiment was divided into zero setting group, control group, and experimental group. The cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the viability of the control culture. Meanwhile, the concentrations of glutamate, YC-1 and ODQ used in assays of apoptosis and cGMP were based on the results of the MTT test.

Assay of cGMP Contents

At confluence, monolayer cells were incubated with indicated agents for 40 min. Then, cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate buffer solution (PBS) and collected in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH = 4.75) using cell scrape, then suspend and crush PC12 cells by ultrasonication. After the centrifugation (3,000 g for 15 min), the supernatant was used for the detection of cGMP content by using a 125I-cGMP radioimmunoassay kit.

Detection of Apoptotic Cells with Flow Cytometry

Apoptosis was assessed by annexin V-FITC and PI staining followed by analysis with flow cytometry (Beckman-Coulter, USA). The methodology followed the procedures as described in the annexin V-FITC/PI detection kit. The cultured cells were exposed to glutamate with the concentration of 15 mM for 24 h. Meanwhile, the cells were pre-treated with or without 10 μM YC-1, 40 μM ODQ for 30 min and followed by incubation. Eventually, the cells were resuspended in a 400 μl 1 × binding buffer solution with a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml, and the cells were stained with 5 μl annexin V-FITC and 10 μl PI for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Then the cell suspension was ready for the analysis by the flow cytometry.

Nuclear Staining Analysis by Hoechst 33258

To further address the death pattern, PC12 cells were stained with hoechst 33258 fluorochrome. The hoechst 33258 fluorochrome is sensitive to chromatin and is used to assess the changes in nuclear morphology. After treatments with glutamate, YC-1 and ODQ for 24 h, the differentiated PC12 cells were washed with PBS, stained with hoechst 33258 fluorochrome (5 μg/ml) for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. After washing twice more with PBS, the hoechst-stained nuclei were imaged with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX70, Japan). Ten random frames were imaged using fluorescence microscope for each concentration, and the number of total cells and apoptotic cells were obtained by counting. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated as follows:

|

Statistical Analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± SEM. Data were evaluated using ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison post hoc test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Glutamate Decreased PC12 Cell Viability

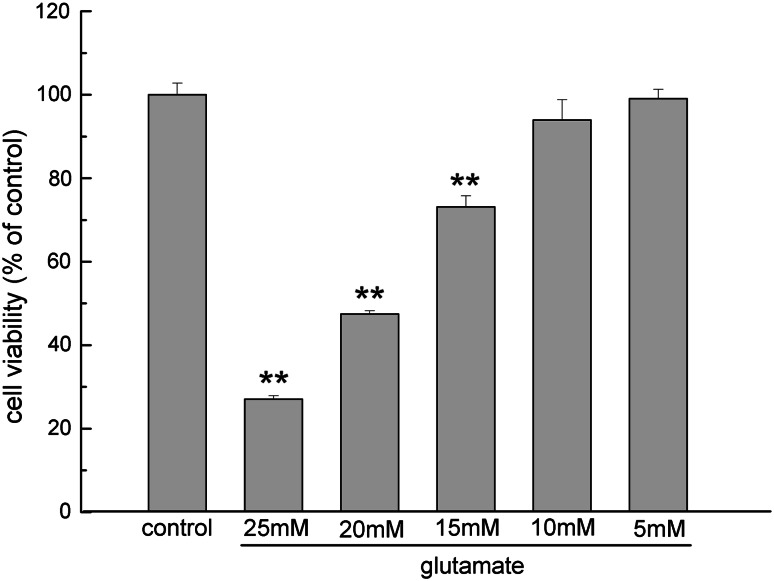

The viability of the differentiated PC12 cells was analyzed using the MTT assay. It was found that with the addition of glutamate to the culture medium for 24 h, the viability of the PC12 cells was significantly reduced in a dose-dependent manner compared with the unexposed cells (Fig. 1). Glutamate induced significant decreases in cell viability at the concentrations of 25, 20 and 15 mM (P < 0.01). The morphological changes of PC12 cells at 15 mM of glutamate under microscopy were such that they became smaller and irregularly shaped. Therefore, this glutamate concentration was used as the cell model of excitotoxicity for the following experiments.

Fig. 1.

The effect of glutamate on PC12 cells was detected by MTT assay. Cells were planted on the cell culture plates at the density of 1 × 105 cells/ml, and then treated with glutamate at different concentrations (25, 20, 15, 10 and 5 mM) for 24 h. The results were presented as a percentage of control group viability. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM of five determinations. ** P < 0.01 vs. control

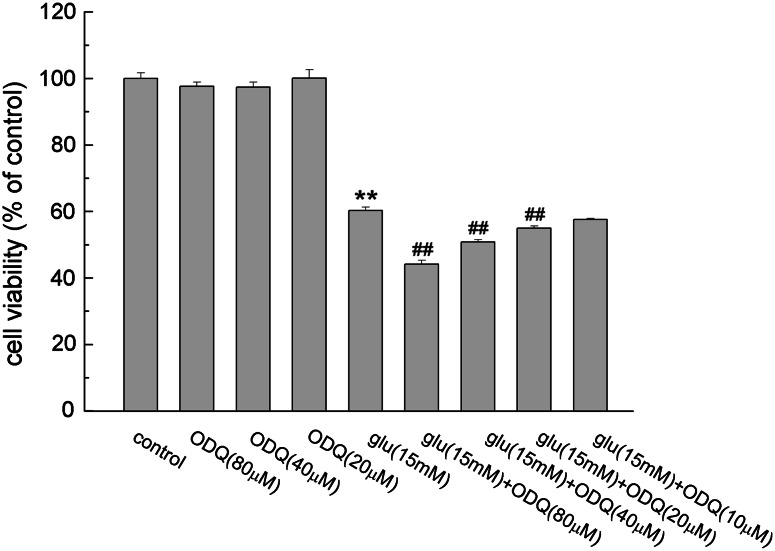

ODQ Potentiated Glutamate Toxicity

As shown in Fig. 2, the exposure of PC12 cells to 15 mM glutamate led to a 40% decrease of cell viability. ODQ, a specific inhibitor of sGC, caused no significant damage to the cells when added alone. But ODQ resulted in a decrease of cell viability in a dose-dependent manner when combined with glutamate (P < 0.01). ODQ aggravated glutamate-induced cell damage at concentrations of 20, 40 and 80 μM, and the cell viabilities were reduced to 54.93 ± 0.68, 50.84 ± 0.69 and 44.13 ± 0.38%, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Effect of ODQ on glutamate-induced PC12 cell damage. Cells were treated with different concentrations of ODQ alone or together with glutamate. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM of five determinations. ** P < 0.01 vs. control; ## P < 0.01 vs. Glu

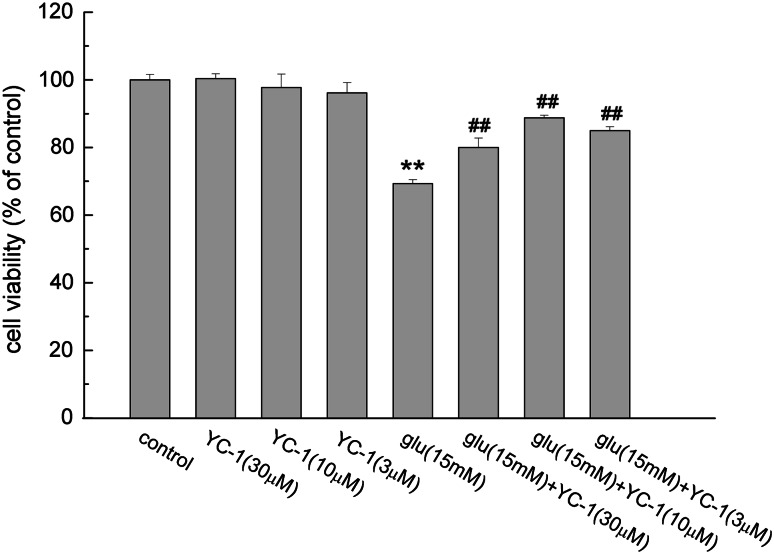

Effect of YC-1 on Glutamate-Induced Cell Damage

The results of MTT assay showed that YC-1 alone at the concentrations of 30, 10 and 3 μM had no difference in PC12 cell viability compared with that of the control group. But pretreatment with YC-1 could decrease the damage effect of glutamate on PC12 cells. YC-1 (10 μM) increased PC12 cell viability from 69.31 ± 1.16 to 88.73 ± 0.77% (P < 0.01, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The effect of YC-1 on glutamate induced PC12 cell damage. Cells were pretreated with or without YC-1 (30, 10, 3 μM) for 30 min. Then glutamate (15 mM) was added for another 24 h. After the incubation, the cell viability was assayed using MTT assay method as described in the “Material and Methods” section. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM of five determinations. ** P < 0.01 vs. control; ## P < 0.01 vs. Glu

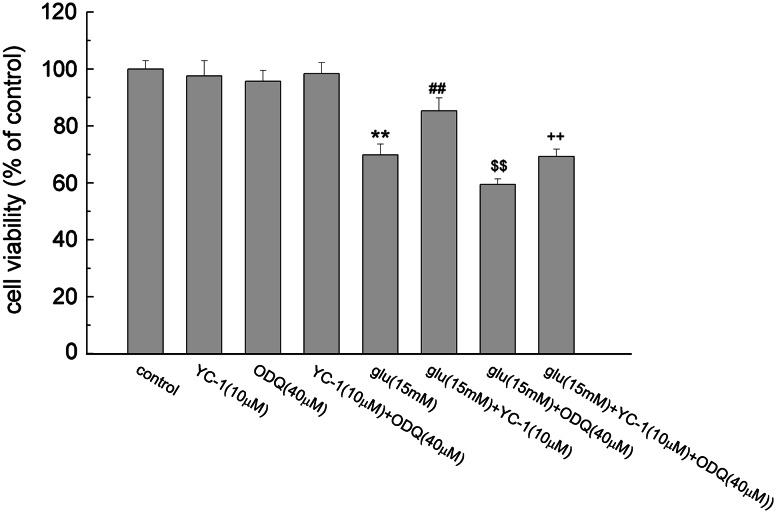

Effects of YC-1 and ODQ on Glutamate-Induced PC12 Cell Damage

Effects of YC-1 and ODQ together on the glutamate-induced PC12 cell death were tested by MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 4, YC-1 (10 μM) added with ODQ (40 μM) had no significant difference in PC12 cell viability compared with that of the control group. Compared with the glutamate group, 10 μM of YC-1 together with glutamate distinctly increased the cell viability (P < 0.01), decreased the PC12 cell death induced by glutamate. ODQ of 40 μM together with glutamate reduced the cell viability, caused even more serious damage to the PC12 cells (P < 0.01). The cell viability was lower than that of the YC-1 + glutamate group when treated with three agents for 24 h (P < 0.01), indicating that ODQ reversed the protective effect of YC-1.

Fig. 4.

The effect of YC-1 and ODQ on glutamate-induced PC12 cell damage. After the treatment of the indicated agents, the cell viability was detected using MTT assay. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM of five determinations. ** P < 0.01 vs. control; ## P < 0.01 vs. Glu; $$ P < 0.01 vs. Glu; ++ P < 0.01 vs. Glu + YC-1

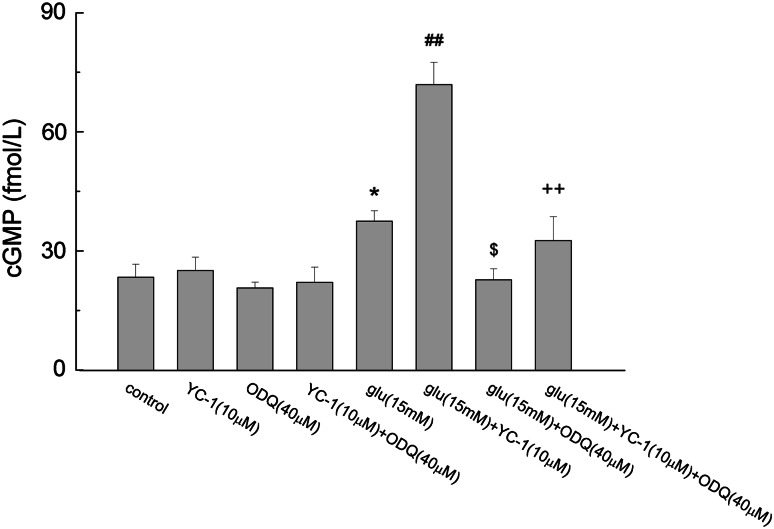

Effects of Glutamate, YC-1, and ODQ on cGMP Synthesis

PC12 cells were cultured with the presence of indicated agents, collected and assayed for intracellular cGMP levels with radioimmunoassay kit. As shown in Fig. 5, YC-1(10 μM) added alone or together with ODQ (40 μM) had no significant difference in intracellular cGMP level of PC12 cells compared with that of the control group. Glutamate increased the production of cGMP from 23.37 ± 3.27 fmol/L in control group to 37.50 ± 2.59 fmol/L (P < 0.05). Combination of YC-1 and glutamate significantly increased intracellular cGMP level to 71.9 ± 5.57 fmol/L (P < 0.01). ODQ decreased the effect of glutamate on cGMP production (P < 0.05). When treated with all three agents, the intracellular cGMP was 32.61 ± 6.03 fmol/L indicating that ODQ significantly inhibited the combination action of glutamate and YC-1 (P < 0.01).

Fig. 5.

The effect of glutamate, YC-1 and ODQ on cGMP production. Cells were treated with the indicated agents for 40 min, and intracellular cGMP was detected as described in the “Material and Methods” section. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM of the three determinations. * P < 0.05 vs. Control; ## P < 0.01 vs. Glu; $ P < 0.05 vs. Glu; ++ P < 0.01 vs. Glu + YC-1

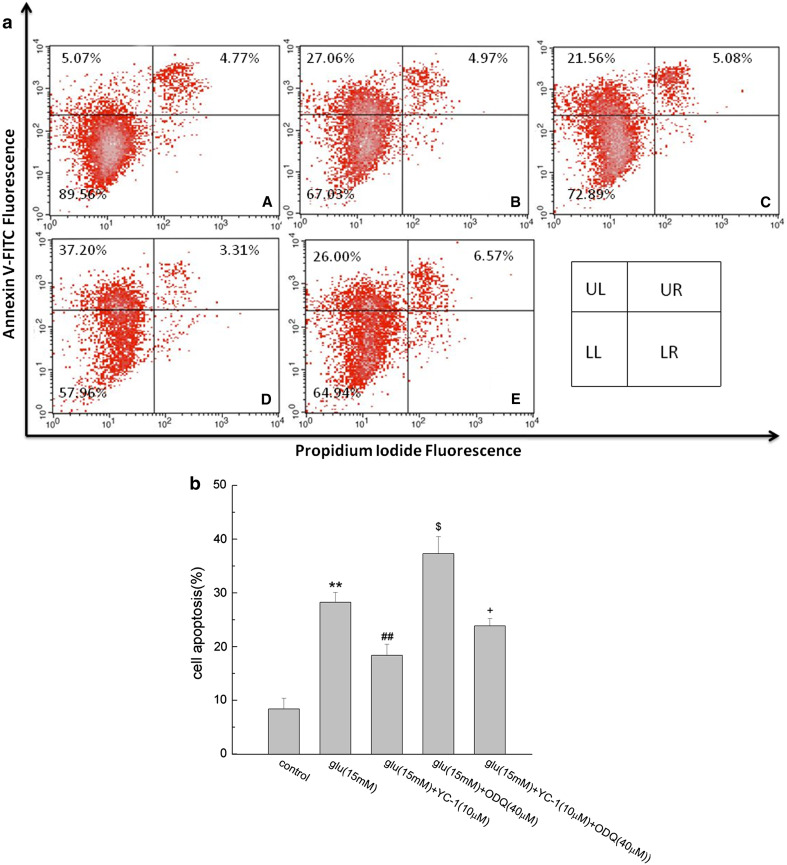

Effects of YC-1 and ODQ on Glutamate-Induced PC12 Cell Apoptosis

The PC12 cell apoptosis was confirmed by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 6, the percentage of early apoptotic cells was increased from 8.40 ± 1.97 to 28.24 ± 1.82% after the cells exposed to 15 mM glutamate for 24 h (P < 0.01). Compared with glutamate along, application of YC-1 together with glutamate decreased the apoptosis rate in PC12 cells (P < 0.01). ODQ together with glutamate brought an apoptosis rate of 37.31 ± 3.14%, aggravated glutamate-induced PC12 cell apoptosis (P < 0.05). When cultured with the three agents together, the apoptosis rate was lower than that of the YC-1 + glutamate group, implying that ODQ blocked the effect of YC-1 on glutamate-induced PC12 cell apoptosis (P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

The effect of YC-1 and ODQ on glutamate-induced PC12 cell apoptosis. After the treatment with indicated agents, cells were washed and collected for the determination of cell apoptosis as described in the “Material and Methods” section. In a, a dot plots showed intensity of Annexin V-FITC fluorescence on the Y-axis and PI fluorescence on the X-axis. LL, living cells (Annexin V-/PI-); UL, early apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI−); UR, late apoptotic cells (Annexin V−/PI−); LR: necrotic cells (Annexin V−/PI+). The percentage of the cells is presented in the area of respective quadrant profiles. A control, B Glu, C YC-1 + Glu, D ODQ + Glu, E YC-1 + ODQ + Glu. b showed the percentage of early apoptotic cells after analysis by flow cytometry. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM of three determinations. ** P < 0.01 vs. control; ## P < 0.01 vs. Glu; $ P < 0.05 vs. Glu; + P < 0.05 vs. Glu + YC-1

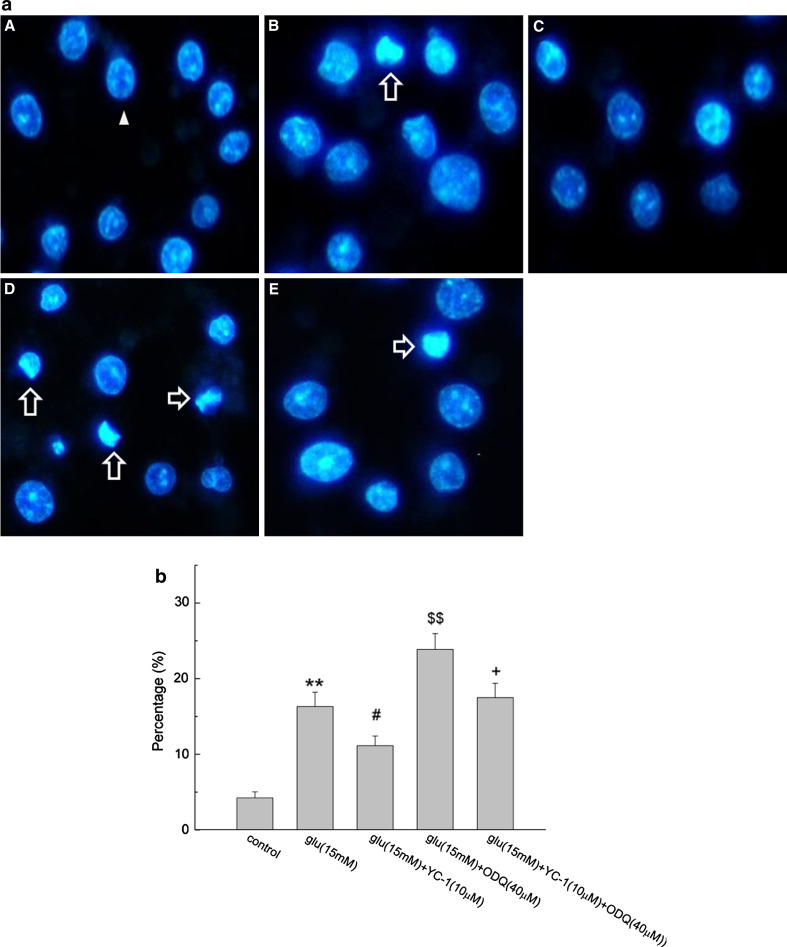

Morphological Assessment of Apoptosis by Hoechst 33258 Staining

The hoechst fluorochrome was able to diffuse through intact membranes of differentiated PC12 cells and stain their DNA. As shown in Fig. 7a, the nuclei exhibited dispersed and weak fluorescence in normal cells (marked by the arrowhead), the apoptotic cells (marked by the blank arrow) showed asymmetric hoechst 33258 staining of their nuclei as a result of chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation. As illustrated in Fig. 7b, after incubation with glutamate for 24 h, about 16.32 ± 1.89% of PC12 cells showed a typical cell apoptosis as revealed by typical chromatin condensation. Cells incubated with ODQ and glutamate revealed the marked condensed chromatin, and the number was significantly increased compared with that of glutamate group (P < 0.01). YC-1 decreased the glutamate-induced apoptotic rate of PC12 cells to 11.13 ± 1.28% (P < 0.05), while the apoptotic rate increased to 17.5 ± 1.87% when three agents were added together (P < 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Morphological assessment of apoptosis by hoechst 33258 staining. a Fluorescence microscope (400×) images. The arrowhead indicated normal nuclei, blank arrows indicated apoptotic nuclei. A control, B Glu, C YC-1 + Glu, D ODQ + Glu, E YC-1 + ODQ + Glu. b Percentage of apoptotic cells treated with the three agent together or respectively (n = 6,  ). ** P < 0.01 vs. control; #

P < 0.05 vs. Glu; $$ P < 0.01 vs. Glu; + P < 0.05 vs. Glu + YC-1

). ** P < 0.01 vs. control; #

P < 0.05 vs. Glu; $$ P < 0.01 vs. Glu; + P < 0.05 vs. Glu + YC-1

Discussion

Aging, which was companied by many neurodegenerative diseases, is characterized by a gradual and progressive loss of function over time, decreases health and well-being. In the aged brain, a consistent number of neurons undergo apoptosis, which may lead to the neurodegeneration in the long run (Floyd and Hensley 2002). Over the past several years, researchers have demonstrated that excitatory amino acids serve as the major excitatory neurotransmitters in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Neurons that contain excitatory amino acids play crucial roles in physiological functions such as learning and memory. But over-activity of the excitatory amino acid system can cause excitotoxicity. Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian CNS. Activation of glutamate receptors leads to increased intracellular calcium which binds to calmodulin and activates different enzymes, including NOS. But in many neurodegenerative diseases, the large amount of glutamate cause excessive activation of glutamate receptor, leading to calcium overload and over production of NO which can trigger a cascade of events eventually leading to apoptosis or necrosis (Ndountse and Chan 2009; Parathath et al. 2007).

A large number of studies have shown that GC-cGMP pathway may influence the process of cell death or cell apoptosis. NO as the sGC activator and NPs as the pGC activator were wildly used for this kind of research. NO can activate sGC and subsequently elevate cGMP levels thus mediate many of the physiological actions of NO such as vasodilation and the inhibition of platelet activation (Fiscus, 1988; Vanhoutte, 1997). Many researchers showed that basal sGC activity/cGMP levels were involved in protecting cells (such as neural cells, leukemia cells) against spontaneous development of apoptosis (Flamigni et al. 2001; Garthwaite and Garthwaite 1988). Kim et al. (1999) showed that NO protected neuronal PC12 cells from serum deprivation-induced apoptosis by elevation or maintenance of intracellular cGMP. NO donors have also been shown to protect against the onset of cell death in NGF-deprived sympathetic neurons in primary culture (Farinelli et al. 1996). Several studies also indicated that NPs may be neuroprotective by increasing cGMP levels (Fiscus et al. 2001). In serum-deprived PC12 cells, both ANP and BNP inhibited apoptotic DNA fragmentation and increased 24 h survival rate by causing prolonged cGMP elevation. Kuribayashi et al. (Kuribayashi et al. 2006) clearly showed that ANP could ameliorate NMDA-induced neurotoxicity via NPR-A in the rat retina which may be in part due to the NP-induced increase of cGMP level.

Although many reports showed that NO may play a protective effect through elevation of cGMP levels, its protective effect may be dependent of the type of cells, the concentrations of NO and the experimental conditions. Nitric oxide can also react with super-oxide radicals to form peroxynitrite, a highly toxic compound, causes neurotoxic effect. For its controversial effect in the nervous system, NO donor as a treatment for neural diseases will be limited.

YC-1 is a newly developed substance. In previous years, researchers indicated that it activated sGC independently of NO (Friebe et al. 1996; Hoenicka et al. 1999; Mulsch et al. 1997; Wu et al. 1995). Recently, it was indicated that it could weakly activate unligated sGC and synergistically activate the NO-bound forms of the enzyme (Derbyshire and Marletta 2009; Stasch and Hobbs 2009). sGC is a heterodimer consisting of two homologous subunits, α1 and β1. Low-level activation of sGC is achieved by the stoichiometric binding of NO (1-NO) to the heme cofactor in the β1 subunit (Cary et al. 2006). There is evidence that YC-1 binds to the N-terminus of the α1subunit, but the exact binding site is still unknown (Stasch et al. 2001). Studies have demonstrated that added with YC-1, rather than excess NO, can further activate low-activity 1-NO adduct by changing the structure of sGC (Cary et al. 2005, 2006; Ibrahim et al. 2010).

Studies with YC-1 have demonstrated that this compound is effective in relaxing the rat corpus cavernosum tissue, inhibits platelet-rich thrombosis and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in vivo through cGMP-dependent mechanisms (Hsieh et al. 2003; Miller et al. 2003; Wu et al. 2004). A role of YC-1 in the enhancement of long-term potentiation in learning and memory has also been proposed (Bredt 2003; Chien et al. 2005, 2008; Garthwaite et al. 2002). YC-1 has also become a valuable research molecule for studies of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α (Bleich et al. 2003; Funasaka et al. 2005). YC-1 decreased HIF-1α levels and showed the antitumor activity by blocking tumor angiogenesis and tumor adaptation to hypoxia (Pan et al. 2005; Yeo et al. 2003). But the results of Chun et al. (2001) showed that the effects of YC-1 were not related to the stimulation of sGC although YC-1 inhibited HIF-1-mediated hypoxic response.

YC-1has been reported to have protective effect on apoptosis of L1210 cells and vascular smooth muscle cells through a cGMP-involved pathway (Flamigni et al. 2001; Pan et al. 2004). Since glutamate is wildly used as the excitotoxitic model of neural cells and has the ability to activate NOS to produce more NO, YC-1 can sensitize sGC activation by nitric oxide and has very low cytotoxicity (Yeo et al. 2003), we proposed that YC-1 may play a positive role in the process of glutamate-induced PC12 cell apoptosis.

In this study, the effect of YC-1 on glutamate-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells was examined. MTT assay showed that YC-1 and/or ODQ had little effect on cell viability change. And intracellular cGMP levels did not show much difference compared with that of control group (P > 0.05). Hoechst staining and flow cytometry showed that glutamate (15 mM) induced profound cell apoptosis. The combination of glutamate and YC-1(10 μM) synergistically evoked cGMP formation, thus YC-1 reduced the glutamate-induced apoptosis. However, ODQ (40 μM) significantly inhibited the action of glutamate and YC-1, suggesting that the activation of sGC is involved in YC-1-mediated anti-apoptotic activity. Taken together, YC-1 attenuated glutamate-induced apoptosis in a cGMP-dependent manner.

In conclusion, this study suggested that glutamate induced a cGMP-independent apoptosis, while YC-1 prevented the glutamate action through a cGMP-involved signal pathway. But the downstream targets of cGMP in neural cells and the protective mechanism of cGMP on glutamate-induced cell apoptosis need further study.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by 100 projects of Nankai university for undergraduates, Tianjin research program of application foundation and advanced technology (10JCZDJC19100) and the national natural science foundation of China (31000509).

References

- Ankarcrona M, Dypbukt JM, Orrenius S, Nicotera P (1996) Calcineurin and mitochondrial function in glutamate-induced neuronal cell death. FEBS Lett 394:321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleich S, Romer K, Wiltfang J, Kornhuber J (2003) Glutamate and the glutamate receptor system: a target for drug action. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 18:S33–S40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredt DS (2003) Nitric oxide signaling in brain: potentiating the gain with YC-1. Mol Pharmacol 63:1206–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary SPL, Winger JA, Marletta MA (2005) Tonic and acute nitric oxide signaling through soluble guanylate cyclase is mediated by nonheme nitric oxide, ATP, and GTP. P Natl Acad Sci USA 102:13064–13069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary SPL, Winger JA, Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA (2006) Nitric oxide signaling: no longer simply on or off. Trends Biochem Sci 31:231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien WL, Liang KC, Teng CM, Kuo SC, Lee FY, Fu WM (2005) Enhancement of learning behaviour by a potent nitric oxide-guanylate cyclase activator YC-1. Eur J Neurosci 21:1679–1688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien WL, Liang KC, Fu WM (2008) Enhancement of active shuttle avoidance response by the NO-cGMP-PKG activator YC-1. Eur J Pharmacol 590:233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW, Rothman SM (1990) The role of glutamate neurotoxicity in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Annu Rev Neurosci 13:171–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun YS, Yeo EJ, Choi E, Teng CM, Bae JM, Kim MS, Park JW (2001) Inhibitory effect of YC-1 on the hypoxic induction of erythropoietin and vascular endothelial growth factor in Hep3B cells. Biochem Pharmacol 61:947–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ (2003) Physiological roles and therapeutic potential of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1003:12–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Puttfarcken P (1993) Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders. Science 262:689–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson VL, Kizushi VM, Huang PL, Snyder SH, Dawson TM (1996) Resistance to neurotoxicity in cortical cultures from neuronal nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. J Neurosci 16:2479–2487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denizot F, Lang R (1986) Rapid colorimetric assay for cell growth and survival. Modifications to the tetrazolium dye procedure giving improved sensitivity and reliability. J Immunol Methods 89:271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA (2009) Biochemistry of soluble guanylate cyclase. Handb Exp Pharmacol:17-31 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Estevez AG, Spear N, Thompson JA, Cornwell TL, Radi R, Barbeito L, Beckman JS (1998) Nitric oxide-dependent production of cGMP supports the survival of rat embryonic motor neurons cultured with brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci 18:3708–3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinelli SE, Park DS, Greene LA (1996) Nitric oxide delays the death of trophic factor-deprived PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons by a cGMP-mediated mechanism. J Neurosci 16:2325–2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscus RR (1988) Molecular mechanisms of endothelium-mediated vasodilation. Semin Thromb Hemost 14 Suppl:12–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscus RR, Robles BT, Waldman SA, Murad F (1987) Atrial natriuretic factors stimulate accumulation and efflux of cyclic GMP in C6-2B rat glioma and PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cell cultures. J Neurochem 48:522–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscus RR, Tu AW, Chew SB (2001) Natriuretic peptides inhibit apoptosis and prolong the survival of serum-deprived PC12 cells. Neuroreport 12:185–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamigni F, Facchini A, Stanic I, Tantini B, Bonavita F, Stefanelli C (2001) Control of survival of proliferating L1210 cells by soluble guanylate cyclase and p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase modulators. Biochem Pharmacol 62:319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd RA, Hensley K (2002) Oxidative stress in brain aging. Implications for therapeutics of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Aging 23:795–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friebe A, Schultz G, Koesling D (1996) Sensitizing soluble guanylyl cyclase to become a highly CO-sensitive enzyme. EMBO J 15:6863–6868 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froissard P, Duval D (1994) Cytotoxic effects of glutamic acid on PC12 cells. Neurochem Int 24:485–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funasaka T, Yanagawa T, Hogan V, Raz A (2005) Regulation of phosphoglucose isomerase/autocrine motility factor expression by hypoxia. FASEB J 19:1422–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite G, Garthwaite J (1988) Cyclic GMP and cell death in rat cerebellar slices. Neuroscience 26:321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite G, Goodwin DA, Neale S, Riddall D, Garthwaite J (2002) Soluble guanylyl cyclase activator YC-1 protects white matter axons from nitric oxide toxicity and metabolic stress, probably through Na(+) channel inhibition. Mol Pharmacol 61:97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstner B, Lee J, DeSilva TM, Jensen FE, Volpe JJ, Rosenberg PA (2009) 17beta-estradiol protects against hypoxic/ischemic white matter damage in the neonatal rat brain. J Neurosci Res 87:2078–2086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene LA (1978) Nerve growth factor prevents the death and stimulates the neuronal differentiation of clonal PC12 pheochromocytoma cells in serum-free medium. J Cell Biol 78:747–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenicka M, Becker EM, Apeler H, Sirichoke T, Schroder H, Gerzer R, Stasch JP (1999) Purified soluble guanylyl cyclase expressed in a baculovirus/Sf9 system: stimulation by YC-1, nitric oxide, and carbon monoxide. J Mol Med 77:14–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh GC, O’Neill AB, Moreland RB, Sullivan JP, Brioni JD (2003) YC-1 potentiates the nitric oxide/cyclic GMP pathway in corpus cavernosum and facilitates penile erection in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 458:183–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim M, Derbyshire ER, Soldatova AV, Marletta MA, Spiro TG (2010) Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Is Activated Differently by Excess NO and by YC-1: Resonance Raman Spectroscopic Evidence. Biochemistry-Us 49:4864–4871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishima T, Nishimura T, Iyo M, Hashimoto K (2008) Potentiation of nerve growth factor-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells by donepezil: role of sigma-1 receptors and IP3 receptors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 32:1656–1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YM, Chung HT, Kim SS, Han JA, Yoo YM, Kim KM, Lee GH, Yun HY, Green A, Li J, Simmons RL, Billiar TR (1999) Nitric oxide protects PC12 cells from serum deprivation-induced apoptosis by cGMP-dependent inhibition of caspase signaling. J Neurosci 19:6740–6747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuribayashi K, Kitaoka Y, Kumai T, Munemasa Y, Isenoumi K, Motoki M, Kogo J, Hayashi Y, Kobayashi S, Ueno S (2006) Neuroprotective effect of atrial natriuretic peptide against NMDA-induced neurotoxicity in the rat retina. Brain Res 1071:34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA, Rosenberg PA (1994) Excitatory amino acids as a final common pathway for neurologic disorders. N Engl J Med 330:613–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LN, Nakane M, Hsieh GC, Chang R, Kolasa T, Moreland RB, Brioni JD (2003) A-350619: a novel activator of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Life Sci 72:1015–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulsch A, Bauersachs J, Schafer A, Stasch JP, Kast R, Busse R (1997) Effect of YC-1, an NO-independent, superoxide-sensitive stimulator of soluble guanylyl cyclase, on smooth muscle responsiveness to nitrovasodilators. Br J Pharmacol 120:681–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndountse LT, Chan HM (2009) Role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in polychlorinated biphenyl mediated neurotoxicity. Toxicol Lett 184:50–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan SL, Guh JH, Chang YL, Kuo SC, Lee FY, Teng CM (2004) YC-1 prevents sodium nitroprusside-mediated apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res 61:152–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan SL, Guh JH, Peng CY, Wang SW, Chang YL, Cheng FC, Chang JH, Kuo SC, Lee FY, Teng CM (2005) YC-1[3-(5′-hydroxymethyl-2′-furyl)-1-benzyl indazole] inhibits endothelial cell functions induced by angiogenic factors in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 314:35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parathath SR, Gravanis I, Tsirka SE (2007) Nitric oxide synthase isoforms undertake unique roles during excitotoxicity. Stroke 38:1938–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukenstein A, Rydel RE, Greene LA (1991) Multiple agents rescue PC12 cells from serum-free cell death by translation- and transcription-independent mechanisms. J Neurosci 11:2552–2563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasch JP, Hobbs AJ (2009) NO-independent, haem-dependent soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators. Handb Exp Pharmacol 191:277–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasch JP, Becker EM, Alonso-Alija C, Apeler H, Dembowsky K, Feurer A, Gerzer R, Minuth T, Perzborn E, Pleiss U, Schroder H, Schroeder W, Stahl E, Steinke W, Straub A, Schramm M (2001) NO-independent regulatory site on soluble guanylate cyclase. Nature 410:212–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thippeswamy T, Morris R (1997) Cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-mediated neuroprotection by nitric oxide in dissociated cultures of rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. Brain Res 774:116–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urushitani M, Nakamizo T, Inoue R, Sawada H, Kihara T, Honda K, Akaike A, Shimohama S (2001) N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-mediated mitochondrial Ca(2+) overload in acute excitotoxic motor neuron death: a mechanism distinct from chronic neurotoxicity after Ca(2+) influx. J Neurosci Res 63:377–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte PM (1997) Endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J 18 (Suppl E):E19–29 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wu CC, Ko FN, Kuo SC, Lee FY, Teng CM (1995) YC-1 inhibited human platelet aggregation through NO-independent activation of soluble guanylate cyclase. Br J Pharmacol 116:1973–1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CH, Chang WC, Chang GY, Kuo SC, Teng CM (2004) The inhibitory mechanism of YC-1, a benzyl indazole, on smooth muscle cell proliferation: an in vitro and in vivo study. J Pharmacol Sci 94:252–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo EJ, Chun YS, Cho YS, Kim J, Lee JC, Kim MS, Park JW (2003) YC-1: a potential anticancer drug targeting hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Natl Cancer Inst 95:516–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]