Abstract

Brain pericytes regulate a variety of functions, such as microcirculation, angiogenesis, and the blood brain barrier in the brain. Recent studies have also shown that they are pluripotent in a manner similar to mesenchymal stem cells. Since, brain pericytes actively control these functions, these cells probably play an important role not only during brain ischemia, but also in the post-stroke period.

Keywords: Pericytes, Brain ischemia, Angiogenesis, Neurogenesis, Blood brain barrier

Introduction

Pericytes encircle endothelial cells in the capillaries as perivascular cells in almost all tissues and organs. They have been long considered to be the cells supporting capillaries, which are therefore equivalent to smooth muscle cells in the arteries or veins. However, recent studies have disclosed some surprising features which demonstrate that these cells actively control a variety of functions (Hirschi and D’Amore 1996; Dore-Duffy 2008). The density of pericytes is the highest in the brain (Frank et al. 1987; Shepro and Morel 1993), thus suggesting that these cells play an important role in the brain.

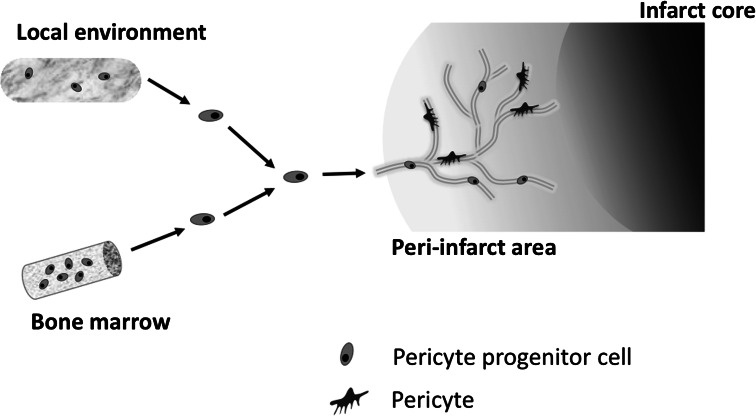

Brain pericytes are an essential constituent of neurovascular units and they are required for both the stabilization and maturation of the capillary as well as the blood brain barrier (Hirschi and D’Amore 1996; Balabanov and Dore-Duffy 1998; Rucker et al. 2000; Allt and Lawrenson 2001; Fisher 2009; Kamouchi et al. 2011). We have previously shown that cultured CNS pericytes respond to diverse extracellular stimuli including acidosis, high glucose, and reactive oxygen species (Wakisaka et al. 2001; Kamouchi et al. 2007; Nakamura et al. 2008, 2009). Recent studies have also revealed that these cells possess a pluripotential activity (Brachvogel et al. 2005, 2007; Dore-Duffy et al. 2006). After ischemic insult, pericytes strongly migrate into the peri-infarct area surrounding the necrotic tissue (Renner et al. 2003). They are recruited from bone marrow via either peripheral blood or the local microenvironment (Fig. 1), and most likely help to repair the injured brain after stroke (Kokovay et al. 2006; Lamagna and Bergers 2006; Kamouchi et al. 2011). In this review, we refer to previous studies suggestive of the roles of pericytes in brain ischemia and propose that brain pericytes play a pivotal role during ischemia and in the post-stroke period.

Fig. 1.

Pericyte progenitor cells are probably derived from bone marrow and then migrate into peri-infarct area via peripheral circulation after stroke. They may also originate from the immature cells in the local environment in the brain. Pericytes are considered to possess multipotent activity and are able to differentiate into different lineages similar to MSCs

Dysregulation of Microcirculation During and After Brain Iischemia

Recent in vivo studies have provided direct evidence that brain pericytes dynamically contracted or relaxed in response to neural activity (Peppiatt et al. 2006). The contraction of the cells obstructs the passage of erythrocytes and therefore impairs the microcirculation. In cultured human brain pericytes, reactive oxygen species induced a sustained increase in cytosolic Ca2+ which leads to the contraction of the cells (Kamouchi et al. 2007; Nakamura et al. 2009). In mouse brain during ischemia, pericytes have been shown to contract due to oxidative–nitrative stress and impair capillary flow (Yemisci et al. 2009). In a mouse focal ischemia model, the contraction of the cells occurred during the occlusion of the middle cerebral artery and this phenomenon was sustained over time, even after reopening of the occluded artery. Pericyte contraction caused by reactive oxygen species results in microcirculation failure, which may thus be one of the mechanisms that induce ischemia/reperfusion injury (Dalkara et al. 2011).

Angiogenesis After Stroke

In brain ischemia, angiogenesis-related genes are upregulated and angiogenic factors are produced in the brain (Zhang and Chopp 2002; Hayashi et al. 2003). In both the human and rodent brain ischemia, growth factors, cytokines/chemokines, and angiogenic mediators increase (Fan and Yang 2007). Studies using gene expression and a histochemical analysis have revealed significant changes in VEGF/VEGFR, angiopoietin/Tie, PDGF-B/PDGFR-β, TGF-β, and FGF signaling in a transient and permanent ischemia model in rats or mice (Zhang et al. 2002; Beck and Plate 2009). Because these angiogenic factors have significant effects on the pericyte functions; pericytes are probably involved in post-ischemic angiogenesis by controlling the formation and maturation of new vessels (Hirschi and D’Amore 1996; Gerhardt and Betsholtz 2003; Armulik et al. 2005; von Tell et al. 2006; Kamouchi et al. 2011).

After brain ischemia, endothelial cells are activated and vessel sprouting occurs in the boundary of ischemia (Chopp et al. 2007; Beck and Plate 2009; Xiong et al. 2010). Concomitantly, pericytes migrate and increase in the peri-ischemic area after ischemic insult (Armulik et al. 2005; Kamouchi et al. 2011) (Fig. 1). In the rabbit brain ischemic model, the number of granular pericytes significantly increased at 2 h after ischemia (Jeynes 1985). Moreover, the expression of PDGF-B and PDGFR-β was upregulated in the mouse focal cerebral ischemia model. The expression of PDGFR-β was specifically upregulated in the vascular structure, primarily in pericytes (Renner et al. 2003).

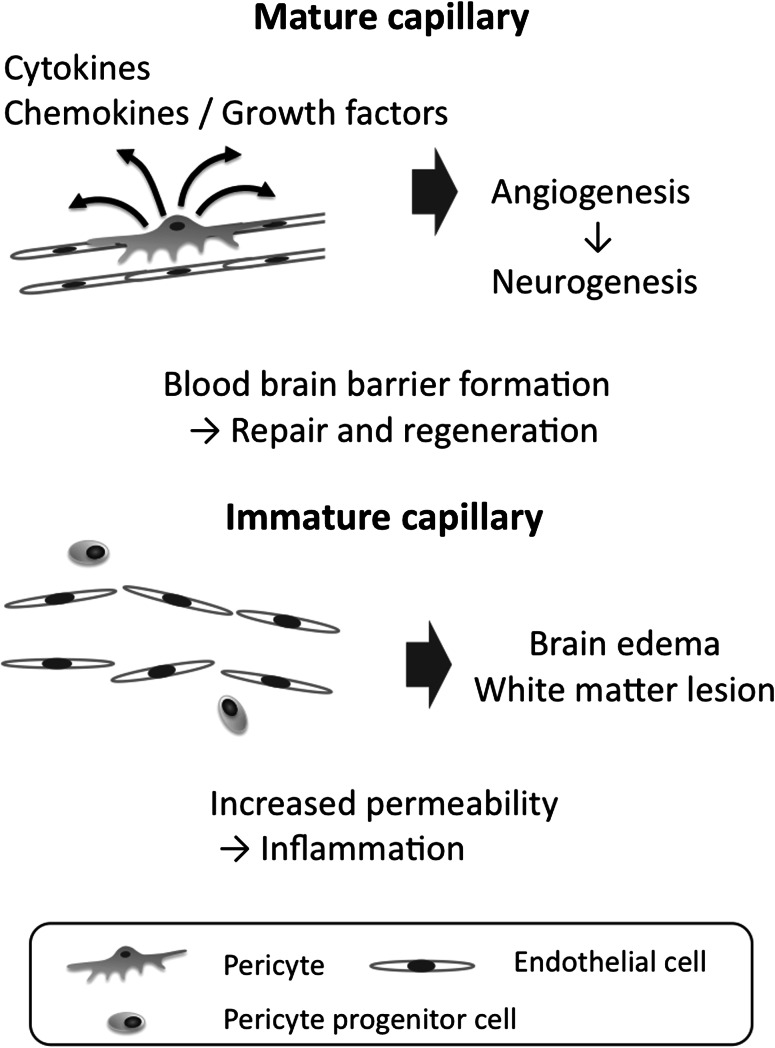

Brain ischemia stimulates endogenous neural progenitor cells and promotes neurogenesis (Zhang et al. 2005; Burns et al. 2009). The anatomical association and the close link in signaling indicate that angiogenesis is a crucial step for neurogenesis (Palmer et al. 2000; Thored et al. 2007). Adult neurogenesis occurs within the angiogenic niche. Vascular cells are required for neuronal recruitment and form a niche for neural stem cells (Palmer et al. 2000). Newly formed neurons are located in close vicinity of the remodeling vasculature, and the vascular system is necessary for the endogenous repair of damaged brain tissue (Okano et al. 2007). It is unclear whether neural progenitor cells require the blood vessel as a scaffold during migration into ischemic tissues or whether the stem cells are locally generated in the vascular niche (Jin et al. 2006). The administration of angiogenic factors induced angiogenesis and neurogenesis in rat embolic stroke models (Wang et al. 2004; Li et al. 2007). For example, SDF1 and angiopoietin-1 secreted during angiogenesis may contribute to neurogenesis (Lichtenwalner and Parent 2006; Ohab et al. 2006; Thored et al. 2007). Cultured human brain endothelial cells do not express SDF-1, whereas SDF-1 is expressed in brain pericytes (Seo et al. 2009). As a result, pericytes probably secrete a factor associated with homing, which is involved in neurogenesis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Activated endothelial cells degrade the extracellular matrix and migrate into the peri-infarct area. The cells proliferate and form immature lumens (immature capillary). The pericytes are recruited into the perivascular area and subsequently cover newly formed vessels, leading to the maturation and stabilization of the capillaries (mature capillary). Pericytes play pivotal roles in the maturation of newly formed vessels and the formation of BBB. The disruption of BBB due to pericyte dysfunction may cause brain edema and hemorrhagic infarction after ischemic stroke. At the perivascular position, they secrete a variety of cytokines and express surface proteins to interact with other cell types during the post-stroke period. Pericytes probably play an important role in the formation of the vascular niche, which is essential in neurogenesis. In addition, pericytes have an MSC activity, thus leading to the modulation of the immune response and inflammation. These functions contribute to the repair and regeneration of the injured brain after stroke

Combination therapy of stem cell factor and granulocyte colony stimulating factor induced the migration of bone marrow-derived cells in the brain parenchyma during chronic stroke in mice. In this condition, the number of bone marrow-derived endothelial cells increased, whereas the number of bone marrow-derived pericytes decreased (Piao et al. 2009). Pericytes may promote tissue repair by a balance between active angiogenesis under scarce pericytes and vessel maturation by rich pericyte coverage. The mobilization of the pericytes may contribute to neurogenesis through its interaction with endothelial cells, thereby constituting the vascular niche.

Function as Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) in the Brain

A large number of studies have demonstrated that post-ischemic cell therapy using transplantation of MSCs can improve ischemic damage in rodent brain ischemia models (Bliss et al. 2007; Zhang and Chopp 2009). Cell therapy is a novel therapeutic approach for stroke (Bliss et al. 2007). In human subjects with severe cerebral infarcts, intravenous infusion of autologous MSCs may improve the functional outcomes during the post-stroke periods (Bang et al. 2005). Clinical trials with post-stroke transplantation of autologous MSCs are ongoing (Honmou et al. 2011).

The precise mechanisms by which the transplantation of MSCs mitigates and repairs post-ischemic injury are still not fully understood. MSCs were able to produce growth and trophic factors in response to ischemic brain extracts (Chen et al. 2002). The treatment of MSCs enhanced angiogenesis in the peri-infarcted ischemic boundary zone in a rodent brain ischemia model (Chen et al. 2003; Pavlichenko et al. 2008). Angiogenesis induced by MSCs was associated with an increase in the levels of endogenous factors (Chen et al. 2003). Such tissue regeneration is probably caused not by the direct differentiation of MSCs into neurons, but by the trophic effects due to bioactive factors secreted from the cells (Caplan and Dennis 2006; Caplan 2009).

Implanted MSCs were located at perivascular positions in rat malignant gliomas and expressed pericyte markers (Bexell et al. 2009). MSCs are found as perivascular cells and secrete bioactive substances with immunomodulatory or trophic actions (Caplan 2009). In glioma angiogenesis, transplanted human skin-derived stem cells differentiated into pericytes. In addition, the transplanted cells released high amounts of human TGF-β1 but suppressed expression of VEGF (Pisati et al. 2007). When rats with middle cerebral artery occlusion were treated by the intravenous infusion of human bone marrow stromal cells, the number and density of NG2-positive cells (pericytes) increased with vessel sprouting (Chen et al. 2003). The transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells increased the number and density of NG2 cells and facilitated axonal sprouting and remyelination in rats subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion (Shen et al. 2006). In addition, the transplantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs) improved ischemic white matter lesions after bilateral common carotid artery stenosis in mice. Donor BMMNCs were located at the perivascular position of the microvessels and showed the morphological features of pericytes, thus suggesting that they can differentiate into pericytes (Fujita et al. 2010). Multiple mechanisms are linked to the protective effects of MSCs against ischemic injury, and pericytes are likely involved in this process.

In a murine brain ischemia model, a certain population of bone marrow-derived cells was associated with perivascular cells having the characteristics of pericytes (Kokovay et al. 2006; Piquer-Gil et al. 2009). Data from recent studies are consistent with the idea that MSCs may originate from perivascular cells, and blood vessel walls may act as a reservoir for progenitor cells in multiple human organs (Crisan et al. 2008; Caplan 2009). The similarity between MSCs and pericytes leads us to consider that pericytes may therefore be a promising target for post-stroke therapy. In patients with acute stroke, Jung et al. (2011) showed the number of circulating PDGFRβ positive cells to increase and correlate with neurological improvement. Moreover, the PDGFRβ+ cells isolated from peripheral blood expressed MSC markers and were multipotent under various culture media. MSCs may therefore migrate toward the perivascular space and reconstitute or repair damaged tissues as pericytes (Fig. 1).

Regulation of the Blood Brain Barrier (BBB)

Hypoxia and hypoxia/reoxygenation lead to increased permeability and disruption of the BBB tight junction (Hawkins and Davis 2005). In addition, hypoxic stress increases vascular permeability through a transcellular route as well (Plateel et al. 1997; Cipolla et al. 2004). The alteration of the tight junctions is caused by time-dependent and phase-specific mechanisms (Sandoval and Witt 2008). Because, pericytes are important regulators of the organization of the BBB (Balabanov and Dore-Duffy 1998; Thomas 1999; Lai and Kuo 2005; Persidsky et al. 2006; Armulik et al. 2010; Kamouchi et al. 2011), these cells protect the BBB against ischemic or hypoxic insults (Fig. 2). In fact, an in vitro BBB model using co-culture system with brain endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes revealed that hypoxia-induced hyperpermeability of the endothelial monolayer was attenuated by contact with pericytes (Hayashi et al. 2004). Moreover, endothelial cells may be less responsive to hypoxic stress when co-cultured with pericytes (Hayashi et al. 2004). The effects of pericytes on hypoxia-induced disruption of brain endothelial permeability appear to be dependent on the severity of hypoxia. During mild hypoxia, pericytes accelerated the disruption in the short term and were only effective in preserving barrier function after prolonged exposure in a co-culture BBB model. Pericytes were more effective in preserving the barrier function than astrocytes during severe hypoxia (Al Ahmad et al. 2009).

In the pathological conditions of hypoxia or ischemia, morphological changes occur in the pericytes of the brain microvasculature. An ultrastructural study revealed that pericytes migrate from their original locations during the early stages of hypoxia in the cat brain (Gonul et al. 2002). In a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model, the basement membrane was disorganized and the pericytes were detached from the microvascular wall (Duz et al. 2007). The detachment of pericytes from the disorganized basal membrane may thus be the initial step for hyperpermeability in the ischemic brain. The migration of pericytes from the perivascular position into the interstitial space causes a significant dysfunction of the BBB during hypoxic or ischemic conditions (Fig. 2). In patients with cerebral microbleeds (microhemorrhage), electron microscopy showed iron to be present at the site of pericytes in the capillary wall. Therefore, pericytes may function as a gatekeeper via erythrophagocytosis after the opening of tight junctions (Fisher et al. 2010).

The recruitment of pericytes will be beneficial for improving ischemia-induced hyperpermeability. The transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells restores BBB permeability in the rat and mouse brain ischemia models (Borlongan et al. 2004a, b). The treatment of rats subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion with marrow stromal cell treatment decreased the amount of leakage through the BBB. Marrow stromal cell treatment upregulated angiopoietin1, Tie2, and occludin at the ischemic border (Zacharek et al. 2007). Bone marrow stromal cells may therefore positively contribute to the BBB function in either a direct or indirect manner through the alteration of BBB-related proteins during stroke.

White Matter Lesions

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is an autosomal dominant leukoencephalopathy syndrome. This disease is caused by the mutation of the Notch3 gene (Joutel et al. 1996). Notch3 is predominantly expressed in arterial smooth muscle cells and pericytes in humans (Joutel et al. 2000; Claxton and Fruttiger 2004). In CADASIL patients, capillaries exhibit pericytes with swollen nuclei. Electron microscopy revealed a thickened basement membrane and pericyte degeneration (Haritoglou et al. 2004). Extensive deposits of granular osmiophilic material were found within the basement membrane between the pericytes and endothelial cells (Kanitakis et al. 2002; Lewandowska et al. 2006). The mechanisms of white matter lesions due to mutated Notch3 have not yet been clarified (Joutel 2010). Cerebral vasoreactivity is impaired in CADASIL patients. The dysregulation of the capillary flow by mutated Notch3 proteins in pericytes may therefore underlie the pathogenesis of this condition.

Pericytes may be involved in the process of hypertensive change in cerebral microcirculation. In SHR rats, pericyte-rich capillaries were found more frequently than in WKY rats (Herman and Jacobson 1988). In addition, granular and filamentous pericytes were shown to have distinct changes in the brain of stroke-prone SHR rats. Although, granular pericytes grew in size over time, the filamentous pericytes degenerated as hypertension developed. These changes may cause an increase in endothelial permeability (Tagami et al. 1990). The extravasation of macromolecules such as proteases and immunoglobulins contributes to the pathogenesis of white matter lesions (Ueno et al. 2002). The loss of pericytes is involved in the dysfunction of BBB, which causes plasma component leakage into both the vessel wall and the surrounding brain tissue (Fig. 2). Bell et al. showed brain pericytes to play a key role in the neurovascular functions using a PDGFRβ-deficient mouse. They proposed that a loss of pericytes resulted in neural injury in two ways: (1) through a reduction in brain microcirculation, thus leading to chronic perfusion stress and hypoxia and (2) by means of BBB breakdown with the accumulation of serum proteins and several vasculotoxic and/or neurotoxic micromolecules (Bell et al. 2010). As a result, the loss of pericytes may play a central role in neurodegeneration in the adult brain. Further elucidation of the association between pericyte loss and white matter lesions is thus called for.

Conclusion

During and after brain ischemia, pericytes migrate and probably repair damaged tissue by controlling angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and the BBB function. Our knowledge regarding the functional roles of brain pericytes during brain ischemia is still limited in vivo. Further experiments using genetic manipulation targeting brain pericytes is thus needed to elucidate the importance of these cells in vivo. Up to now, no effective therapy to efficiently repair and regenerate the injured brain has been established. Continued progress in the study and research of pericyte biology may therefore provide important breakthroughs for post-stroke therapy.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by Coordination, Support and Training Program for Translational Research and Grand-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C 19590992, C 22590937) from The Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. We are grateful to Dr. Kuniyuki Nakamura for his helpful suggestions.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Al Ahmad A, Gassmann M, Ogunshola OO (2009) Maintaining blood–brain barrier integrity: pericytes perform better than astrocytes during prolonged oxygen deprivation. J Cell Physiol 218:612–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allt G, Lawrenson JG (2001) Pericytes: cell biology and pathology. Cells Tissues Organs 169:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C (2005) Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res 97:512–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A, Genove G, Mae M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, Johansson BR, Betsholtz C (2010) Pericytes regulate the blood–brain barrier. Nature 468:557–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanov R, Dore-Duffy P (1998) Role of the CNS microvascular pericyte in the blood–brain barrier. J Neurosci Res 53:637–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang OY, Lee JS, Lee PH, Lee G (2005) Autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in stroke patients. Ann Neurol 57:874–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck H, Plate KH (2009) Angiogenesis after cerebral ischemia. Acta Neuropathol 117:481–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, Singh I, LaRue B, Deane R, Zlokovic BV (2010) Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron 68:409–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bexell D, Gunnarsson S, Tormin A, Darabi A, Gisselsson D, Roybon L, Scheding S, Bengzon J (2009) Bone marrow multipotent mesenchymal stroma cells act as pericyte-like migratory vehicles in experimental gliomas. Mol Ther 17:183–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss T, Guzman R, Daadi M, Steinberg GK (2007) Cell transplantation therapy for stroke. Stroke 38:817–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlongan CV, Lind JG, Dillon-Carter O, Yu G, Hadman M, Cheng C, Carroll J, Hess DC (2004a) Bone marrow grafts restore cerebral blood flow and blood brain barrier in stroke rats. Brain Res 1010:108–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlongan CV, Lind JG, Dillon-Carter O, Yu G, Hadman M, Cheng C, Carroll J, Hess DC (2004b) Intracerebral xenografts of mouse bone marrow cells in adult rats facilitate restoration of cerebral blood flow and blood–brain barrier. Brain Res 1009:26–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachvogel B, Moch H, Pausch F, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Hofmann C, Hallmann R, von der Mark K, Winkler T, Poschl E (2005) Perivascular cells expressing annexin A5 define a novel mesenchymal stem cell-like population with the capacity to differentiate into multiple mesenchymal lineages. Development 132:2657–2668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachvogel B, Pausch F, Farlie P, Gaipl U, Etich J, Zhou Z, Cameron T, von der Mark K, Bateman JF, Poschl E (2007) Isolated Anxa5+/Sca-1+ perivascular cells from mouse meningeal vasculature retain their perivascular phenotype in vitro and in vivo. Exp Cell Res 313:2730–2743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns TC, Verfaillie CM, Low WC (2009) Stem cells for ischemic brain injury: a critical review. J Comp Neurol 515:125–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AI (2009) Why are MSCs therapeutic? New data: new insight. J Pathol 217:318–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AI, Dennis JE (2006) Mesenchymal stem cells as trophic mediators. J Cell Biochem 98:1076–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Li Y, Wang L, Katakowski M, Zhang L, Chen J, Xu Y, Gautam SC, Chopp M (2002) Ischemic rat brain extracts induce human marrow stromal cell growth factor production. Neuropathology 22:275–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhang ZG, Li Y, Wang L, Xu YX, Gautam SC, Lu M, Zhu Z, Chopp M (2003) Intravenous administration of human bone marrow stromal cells induces angiogenesis in the ischemic boundary zone after stroke in rats. Circ Res 92:692–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopp M, Zhang ZG, Jiang Q (2007) Neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and MRI indices of functional recovery from stroke. Stroke 38:827–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolla MJ, Crete R, Vitullo L, Rix RD (2004) Transcellular transport as a mechanism of blood–brain barrier disruption during stroke. Front Biosci 9:777–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton S, Fruttiger M (2004) Periodic Delta-like 4 expression in developing retinal arteries. Gene Expr Pattern 5:123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, Chen CW, Corselli M, Park TS, Andriolo G, Sun B, Zheng B, Zhang L, Norotte C, Teng PN, Traas J, Schugar R, Deasy BM, Badylak S, Buhring HJ, Giacobino JP, Lazzari L, Huard J, Peault B (2008) A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell 3:301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalkara T, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Yemisci M (2011) Brain microvascular pericytes in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol 122:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore-Duffy P (2008) Pericytes: pluripotent cells of the blood brain barrier. Curr Pharm Des 14:1581–1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore-Duffy P, Katychev A, Wang X, Van Buren E (2006) CNS microvascular pericytes exhibit multipotential stem cell activity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 26:613–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duz B, Oztas E, Erginay T, Erdogan E, Gonul E (2007) The effect of moderate hypothermia in acute ischemic stroke on pericyte migration: an ultrastructural study. Cryobiology 55:279–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Yang GY (2007) Therapeutic angiogenesis for brain ischemia: a brief review. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2:284–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M (2009) Pericyte signaling in the neurovascular unit. Stroke 40:S13–S15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, French S, Ji P, Kim RC (2010) Cerebral microbleeds in the elderly: a pathological analysis. Stroke 41:2782–2785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank RN, Dutta S, Mancini MA (1987) Pericyte coverage is greater in the retinal than in the cerebral capillaries of the rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 28:1086–1091 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Ihara M, Ushiki T, Hirai H, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Hiraoka M, Ito H, Takahashi R (2010) Early protective effect of bone marrow mononuclear cells against ischemic white matter damage through augmentation of cerebral blood flow. Stroke 41:2938–2943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H, Betsholtz C (2003) Endothelial-pericyte interactions in angiogenesis. Cell Tissue Res 314:15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonul E, Duz B, Kahraman S, Kayali H, Kubar A, Timurkaynak E (2002) Early pericyte response to brain hypoxia in cats: an ultrastructural study. Microvasc Res 64:116–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haritoglou C, Hoops JP, Stefani FH, Mehraein P, Kampik A, Dichgans M (2004) Histopathological abnormalities in ocular blood vessels of CADASIL patients. Am J Ophthalmol 138:302–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins BT, Davis TP (2005) The blood–brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev 57:173–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Noshita N, Sugawara T, Chan PH (2003) Temporal profile of angiogenesis and expression of related genes in the brain after ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 23:166–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Nakao S, Nakaoke R, Nakagawa S, Kitagawa N, Niwa M (2004) Effects of hypoxia on endothelial/pericytic co-culture model of the blood–brain barrier. Regul Pept 123:77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman IM, Jacobson S (1988) In situ analysis of microvascular pericytes in hypertensive rat brains. Tissue Cell 20:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi KK, D’Amore PA (1996) Pericytes in the microvasculature. Cardiovasc Res 32:687–698 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honmou O, Houkin K, Matsunaga T, Niitsu Y, Ishiai S, Onodera R, Waxman SG, Kocsis JD (2011) Intravenous administration of auto serum-expanded autologous mesenchymal stem cells in stroke. Brain 134:1790–1807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeynes B (1985) Reactions of granular pericytes in a rabbit cerebrovascular ischemia model. Stroke 16:121–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Wang X, Xie L, Mao XO, Zhu W, Wang Y, Shen J, Mao Y, Banwait S, Greenberg DA (2006) Evidence for stroke-induced neurogenesis in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:13198–13202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutel A (2010) Pathogenesis of CADASIL: transgenic and knock-out mice to probe function and dysfunction of the mutated gene, Notch3, in the cerebrovasculature. Bioessays 33:73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutel A, Corpechot C, Ducros A, Vahedi K, Chabriat H, Mouton P, Alamowitch S, Domenga V, Cecillion M, Marechal E, Maciazek J, Vayssiere C, Cruaud C, Cabanis EA, Ruchoux MM, Weissenbach J, Bach JF, Bousser MG, Tournier-Lasserve E (1996) Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia. Nature 383:707–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutel A, Andreux F, Gaulis S, Domenga V, Cecillon M, Battail N, Piga N, Chapon F, Godfrain C, Tournier-Lasserve E (2000) The ectodomain of the Notch3 receptor accumulates within the cerebrovasculature of CADASIL patients. J Clin Invest 105:597–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KH, Chu K, Lee ST, Bahn JJ, Jeon D, Kim JH, Kim S, Won CH, Kim M, Lee SK, Roh JK (2011) Multipotent PDGFRβ-expressing cells in the circulation of stroke patients. Neurobiol Dis 41:489–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamouchi M, Kitazono T, Ago T, Wakisaka M, Kuroda J, Nakamura K, Hagiwara N, Ooboshi H, Ibayashi S, Iida M (2007) Hydrogen peroxide-induced Ca2+ responses in CNS pericytes. Neurosci Lett 416:12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamouchi M, Ago T, Kitazono T (2011) Brain pericytes: emerging concepts and functional roles in brain homeostasis. Cell Mol Neurobiol 31:175–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanitakis J, Thobois S, Claudy A, Broussolle E (2002) CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy): a neurovascular disease diagnosed by ultrastructural examination of the skin. J Cutan Pathol 29:498–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokovay E, Li L, Cunningham LA (2006) Angiogenic recruitment of pericytes from bone marrow after stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 26:545–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CH, Kuo KH (2005) The critical component to establish in vitro BBB model: Pericyte. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 50:258–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamagna C, Bergers G (2006) The bone marrow constitutes a reservoir of pericyte progenitors. J Leukoc Biol 80:677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska E, Leszczynska A, Wierzba-Bobrowicz T, Skowronska M, Mierzewska H, Pasennik E, Czlonkowska A (2006) Ultrastructural picture of blood vessels in muscle and skin biopsy in CADASIL. Folia Neuropathol 44:265–273 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Jiang Q, Zhang L, Ding G, Gang Zhang Z, Li Q, Ewing JR, Lu M, Panda S, Ledbetter KA, Whitton PA, Chopp M (2007) Angiogenesis and improved cerebral blood flow in the ischemic boundary area detected by MRI after administration of sildenafil to rats with embolic stroke. Brain Res 1132:185–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenwalner RJ, Parent JM (2006) Adult neurogenesis and the ischemic forebrain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 26:1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kamouchi M, Kitazono T, Kuroda J, Matsuo R, Hagiwara N, Ishikawa E, Oobosi H, Ibayashi S, Iida M (2008) Role of NHE1 in calcium signaling and cell proliferation in human CNS pericytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294:H1700–H1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kamouchi M, Kitazono T, Kuroda J, Shono Y, Hagiwara N, Ago T, Ooboshi H, Ibayashi S, Iida M (2009) Amiloride inhibits hydrogen peroxide-induced Ca2+ responses in human CNS pericytes. Microvasc Res 77:327–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohab JJ, Fleming S, Blesch A, Carmichael ST (2006) A neurovascular niche for neurogenesis after stroke. J Neurosci 26:13007–13016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano H, Sakaguchi M, Ohki K, Suzuki N, Sawamoto K (2007) Regeneration of the central nervous system using endogenous repair mechanisms. J Neurochem 102:1459–1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer TD, Willhoite AR, Gage FH (2000) Vascular niche for adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol 425:479–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlichenko N, Sokolova I, Vijde S, Shvedova E, Alexandrov G, Krouglyakov P, Fedotova O, Gilerovich EG, Polyntsev DG, Otellin VA (2008) Mesenchymal stem cells transplantation could be beneficial for treatment of experimental ischemic stroke in rats. Brain Res 1233:203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppiatt CM, Howarth C, Mobbs P, Attwell D (2006) Bidirectional control of CNS capillary diameter by pericytes. Nature 443:700–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Ramirez SH, Haorah J, Kanmogne GD (2006) Blood-brain barrier: structural components and function under physiologic and pathologic conditions. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 1:223–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao CS, Gonzalez-Toledo ME, Xue YQ, Duan WM, Terao S, Granger DN, Kelley RE, Zhao LR (2009) The role of stem cell factor and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor in brain repair during chronic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 29:759–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquer-Gil M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Zipancic I, Sanchez MJ, Alvarez-Dolado M (2009) Cell fusion contributes to pericyte formation after stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 29:480–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisati F, Belicchi M, Acerbi F, Marchesi C, Giussani C, Gavina M, Javerzat S, Hagedorn M, Carrabba G, Lucini V, Gaini SM, Bresolin N, Bello L, Bikfalvi A, Torrente Y (2007) Effect of human skin-derived stem cells on vessel architecture, tumor growth, and tumor invasion in brain tumor animal models. Cancer Res 67:3054–3063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plateel M, Teissier E, Cecchelli R (1997) Hypoxia dramatically increases the nonspecific transport of blood-borne proteins to the brain. J Neurochem 68:874–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner O, Tsimpas A, Kostin S, Valable S, Petit E, Schaper W, Marti HH (2003) Time- and cell type-specific induction of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta during cerebral ischemia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 113:44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker HK, Wynder HJ, Thomas WE (2000) Cellular mechanisms of CNS pericytes. Brain Res Bull 51:363–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval KE, Witt KA (2008) Blood–brain barrier tight junction permeability and ischemic stroke. Neurobiol Dis 32:200–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J, Kim YO, Jo I (2009) Differential expression of stromal cell-derived factor 1 in human brain microvascular endothelial cells and pericytes involves histone modifications. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 382:519–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen LH, Li Y, Chen J, Zhang J, Vanguri P, Borneman J, Chopp M (2006) Intracarotid transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells increases axon-myelin remodeling after stroke. Neuroscience 137:393–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepro D, Morel NM (1993) Pericyte physiology. FASEB J 7:1031–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagami M, Nara Y, Kubota A, Fujino H, Yamori Y (1990) Ultrastructural changes in cerebral pericytes and astrocytes of stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke 21:1064–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WE (1999) Brain macrophages: on the role of pericytes and perivascular cells. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 31:42–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thored P, Wood J, Arvidsson A, Cammenga J, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O (2007) Long-term neuroblast migration along blood vessels in an area with transient angiogenesis and increased vascularization after stroke. Stroke 38:3032–3039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno M, Tomimoto H, Akiguchi I, Wakita H, Sakamoto H (2002) Blood–brain barrier disruption in white matter lesions in a rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22:97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Tell D, Armulik A, Betsholtz C (2006) Pericytes and vascular stability. Exp Cell Res 312:623–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakisaka M, Kitazono T, Kato M, Nakamura U, Yoshioka M, Uchizono Y, Yoshinari M (2001) Sodium-coupled glucose transporter as a functional glucose sensor of retinal microvascular circulation. Circ Res 88:1183–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zhang R, Chopp M (2004) Treatment of stroke with erythropoietin enhances neurogenesis and angiogenesis and improves neurological function in rats. Stroke 35:1732–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Mahmood A, Chopp M (2010) Angiogenesis, neurogenesis and brain recovery of function following injury. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 11:298–308 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yemisci M, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Vural A, Can A, Topalkara K, Dalkara T (2009) Pericyte contraction induced by oxidative–nitrative stress impairs capillary reflow despite successful opening of an occluded cerebral artery. Nat Med 15:1031–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharek A, Chen J, Cui X, Li A, Li Y, Roberts C, Feng Y, Gao Q, Chopp M (2007) Angiopoietin1/Tie2 and VEGF/Flk1 induced by MSC treatment amplifies angiogenesis and vascular stabilization after stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27:1684–1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Chopp M (2002) Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietins in focal cerebral ischemia. Trends Cardiovasc Med 12:62–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZG, Chopp M (2009) Neurorestorative therapies for stroke: underlying mechanisms and translation to the clinic. Lancet Neurol 8:491–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZG, Zhang L, Tsang W, Soltanian-Zadeh H, Morris D, Zhang R, Goussev A, Powers C, Yeich T, Chopp M (2002) Correlation of VEGF and angiopoietin expression with disruption of blood–brain barrier and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22:379–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RL, Zhang ZG, Chopp M (2005) Neurogenesis in the adult ischemic brain: generation, migration, survival, and restorative therapy. Neuroscientist 11:408–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]