Abstract

Glutamate excitotoxicity is thought to play an important role in Huntington’s disease (HD), which is caused by a polyglutamine expansion in the HD protein huntingtin (htt). Overactivation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), which include mGluR1 as well as mGluR5 and are coupled via phospholipase C to the inositol phosphate pathway, is found to be involved in mutant htt-mediated neurotoxicity. However, activation of mGluR5 also leads to neuronal protection. Here, we report that mutant htt can activate both mGluR5-mediated ERK and JNK signaling pathways. While increased JNK signaling causes cell death, activation of ERK signaling pathway is protective against cell death. Expression of mutant htt in cultured cells causes greater activation of JNK than ERK. These findings suggest that selective inhibition of the JNK signaling pathway may offer an effective therapeutic approach for reducing htt-mediated excitotoxicity.

Keywords: Huntington’s disease, mGluRs, ERK, JNK

Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD), which is characterized by symptoms of involuntary body movement, cognitive dysfunction, and psychiatric disturbance, is caused by a glutamine expansion (>36 glutamins) in the amino terminus of huntingtin (htt), a ubiquitously expressed 350-kDa protein (The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group 1993; Vonsattel and DiFiglia 1998; Ross 1995; Nance 1997). Mutant htt with an expanded polyglutamine (polyQ) tract causes selective neurodegeneration that preferentially affects medium-sized spiny neurons (MSNs) (Li et al. 1993; DiFiglia et al. 1995; Fusco et al. 1999; DiFiglia 1990). Despite extensive studies of htt and its role in HD pathogenesis, mechanisms underlying the selective neurodegeneration in HD are not fully understood.

Previous studies demonstrated that glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity plays an important role in the pathogenesis of HD (Beal et al. 1991; Storey et al. 1992; Nicoletti et al. 1996; Calabresi et al. 1999). Glutamate signaling via both ionotropic and metabotropic receptors may be linked with htt function and HD neuropathology. Mutant htt facilitates activity of NR1/NR2B NMDAR (Chen et al. 1999; Sun et al. 2001; Zeron et al. 2002), leading to Ca2+ influx and resulting in degeneration of MSNs in HD (Bezprozvanny and Hayden 2004; Tang et al. 2005). Emerging evidence has indicated that Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), which are positively coupled to phosphoinositide (PI) hydrolysis through Gaq proteins (Nakanishi 1994; Conn and Pin 1997), contribute to the underlying pathophysiology of HD. In particular, the survival of R6/2 HD transgenic mice is significantly increased following treatment with mGluR5 antagonists (Schiefer et al. 2004). In addition, the association of mutant htt and htt-associated protein 1(HAP1) with the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptor alters mGluR5-stimulated Ca2+ signaling (Tang et al. 2003). Specifically, htt is co-precipitated with mGluR1a, and mutant htt functions to facilitate optineurin-mediated attenuation of mGluR1a signaling (Anborgh et al. 2005). Although the results of studies outlined above support the hypothesis that Group I mGluRs-mediated excitotoxicity may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of HD, the evidence is indirect.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) signaling has been implicated in a number of neurodegenerative disorders, including HD. Glutamate is a major excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain and mediates effective extracellular signals that readily activate MAPKs in striatal neurons in vivo and in vitro (Wang et al. 2004). The MAPK superfamily comprises three major signaling pathways: the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERKs), the c-Jun N-terminal kinases or stress-activated protein kinases (JNKs/SAPKs), and the p38 family of kinases (Nozaki et al. 2001; Gallo and Johnson 2002). Recent studies demonstrated that mutant htt alters MAPK signaling pathways in PC12 and striatal cells and suggested that ERK1/2 protects against mutant htt-associated toxicity (Apostol et al. 2006). mGluRs seem to be a candidate for active regulation of the MAPK activity, given their connections to multiple intracellular signaling pathways (Marinissen and Gutkind 2001). These findings also raise the questions of whether mutant htt expression can alter the activity of mGluRs-mediated MAPKs and how such changes account for selective neuronal vulnerability.

We examined the role of mGluR5 in the selective cytotoxicity of mutant htt in cultured striatal neurons and HEK293 cells. We found that mutant htt augments mGluR5-mediated excitotoxicity. Selective mGluR5 activation in HEK293 cells coexpressing mGluR5 and mutant htt (htt-120Q) induced higher ERK and JNK phosphorylation than cells coexpressing mGluR5 and the normal htt (htt-20Q). Inhibition of these pathways leads to induction of both neurotrophic and cell death pathways. The functional relevance of these pathways has implications for novel therapeutic applications for HD.

Materials and Methods

Neuronal Culture

The brain tissue isolation procedure was in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for care and use of laboratory animals and approved by the Huazhong University of Science &Technology laboratory animal use committee. Primary striatal neurons were cultured from the brain striatum of rat fetuses at embryonic day 17–18. Striatum tissue was removed, dissociated, and plated at 1 × 106 cells/ml on poly-d-lysine coated 12-mm glass coverslips in 24-well (Corning Costar) culture plates in Neurobasal media containing 2% B27 supplement (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 0.5 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. At 7–8 DIV, a majority of cells were mature neurons with elongated processes and were used for constructs transfection. Cultured neurons were then transfected for 24 h with constructs encoding the N-terminal 208 amino acids of human htt with 20 (htt-20Q) or 120 (htt-120Q) glutamines. After washing with HEPES buffered saline solution (HBSS: 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.6 mM Na2HPO4, 0.6 mM KH2PO4, 5.6 mM d-glucose, 20 mM HEPES, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 0.9 mM MgSO4, and 10 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.4), transfected neurons were co-cultured with (for antagonist group) or without (for control and agonist group) 200 μM mGluR5 antagonist 2-methyl-6 [phenylethynyl]-pyridine (MPEP) for 30 min in HBSS, followed by treatment with (for agonist and antagonist group) or without (for control group) Group I agonist (R.S.)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) in HBSS for 1 h. Cultures were washed three times with HBSS, returned to fresh medium at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 h before being examined.

MAP2 Immunofluorescent Staining

After treatment, the cells on coverslips were rinsed three times with HBSS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.4) for 30 min at 37°C, permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100 in 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min at 37°C, and then returned to PBS. Fixed cultures were blocked with 10% BSA in PBS for 30 min at 37°C, incubated overnight in monoclonal MAP2 antibody (1:500 HM-2 clone, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 3% BSA/0.4% Triton X-100 in PBS at 4°C. Cultures were then rinsed three times with PBS and incubated with an Alexa 594-conjugated antibody against mouse IgG (1:1000, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in PBS for 60 min at 37°C. The coverslips were counterstained with DAPI (5 mM) for 5 min, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and then rinsed three times with PBS, mounted onto glass slides with PBS/glycerol (1:3), and sealed with clear nail polish. Fluorescence images were acquired with a CoolSnap HQ digital camera (Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ) connected to a Nikon TE2000S epifluorescence microscope. Texas red excitation/emission filters were used to visualize MAP 2 immunofluorescent microscopy, while DAPI filters were used for revealing the DAPI stained nucleus.

Cell Culture and Transfections

HEK293 cells were cultured and transfected using Lipofectamine. Cells were plated at a density of 20,000 cells/ml in 24-well culture dishes grown for 9–12 h before the transfection. To insure that cells expressing mGluR5 also expressed adequate levels of htt, we used a 2:1 ratio of cDNAs encoding mGluR5 and htt (N-terminal fragment of htt with 20Q or 120Q) with a total of 1 μg of plasmid DNA per 24-well plate. Using a ratio of 1 μg cDNA: 3 μl Lipofectamine (Gibco): 100 μl OPTIMEM (Gibco), cells were transfected for 6 h in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After the transfection, cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with fresh medium for 24 h. In each experiment, we used the rabbit polyclonal antibody EM48 (as a gift form Li, XJ) and rabbit polyclonal antibody mGluR5 (Sigma) to determine the transfection efficiency by western blotting. Plates of cells showing less than 50% transfection efficiency were not used for further experiments.

Excitotoxicity Induction

After the transfection (24–36 h), cells were washed twice with warm PBS and then incubated in a physiological salt solution containing: 140 mM NaCl, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 21 mM glucose, and 26 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.4. For the agonist stimulated group, 100 μM DHPG was applied for 1 h. For the antagonist treated group, cells were treated with MPEP for 30 min then exposed to DHPG for 1 h. The cells were incubated for 24 h in humidified 5% CO2, 37°C atmosphere and then examined.

Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates from cultures were sonicated and protein concentrations were determined. An equal amount of protein (30 μg/30 μl/lane) was separated on SDS-PAGE 10% gels. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and blocked in blocking buffer (5% non-fat dry milk in PBS and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h. The blots were incubated with primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies against pERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr 204), ERK1/2, pJNK (Thr183/Tyr 185), JNK, p-p38 (Thr180/Tyr 182), or p38, usually at 1:500–1000 dilution overnight at 4°C, which was followed by 1 h of incubation in goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) at 1:5000 dilution. Immunoblots were developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and the signals were captured into Kodak (Rochester, NY) Image Station 2000R. Kaleidoscope-prestained standards (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were used for protein size determination. The density of immunoblots was measured using the Kodak 1D Image Analysis software, and all bands were normalized to percentages of control values.

Cell Viability Assays

Cell viability was determined by a modified 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTS) assay (Cell Titer 96; Promega), which is based on the conversion of tetrazolium salt 3- (4,5- dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl) 2-H-tetrazolium by mitochondrial dehydrogenase to a formazan product, as measured at an absorbance of 490 nm. HEK293 cells were plated in 24-well plates at a density of 20,000 cells/well. After transfection and drug treatment, 100 μl of MTS reagent (2.1 mg/ml) was added to each well. The cells were then incubated for 30–45 min at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The reaction was stopped by adding 125 μl of 10% SDS. The plates were read with a microplate reader (SPECTRAmax Plus; Molecular Devices, Palo Alto, CA) at 490 nm. Each data point was obtained using a triplet-well assay.

Results

Expressing N-Terminal Fragment of Mutant htt Enhances mGluR5-Mediated Excitotoxicity in Cultured Striatum MSNs and the Death of HEK293 Cells

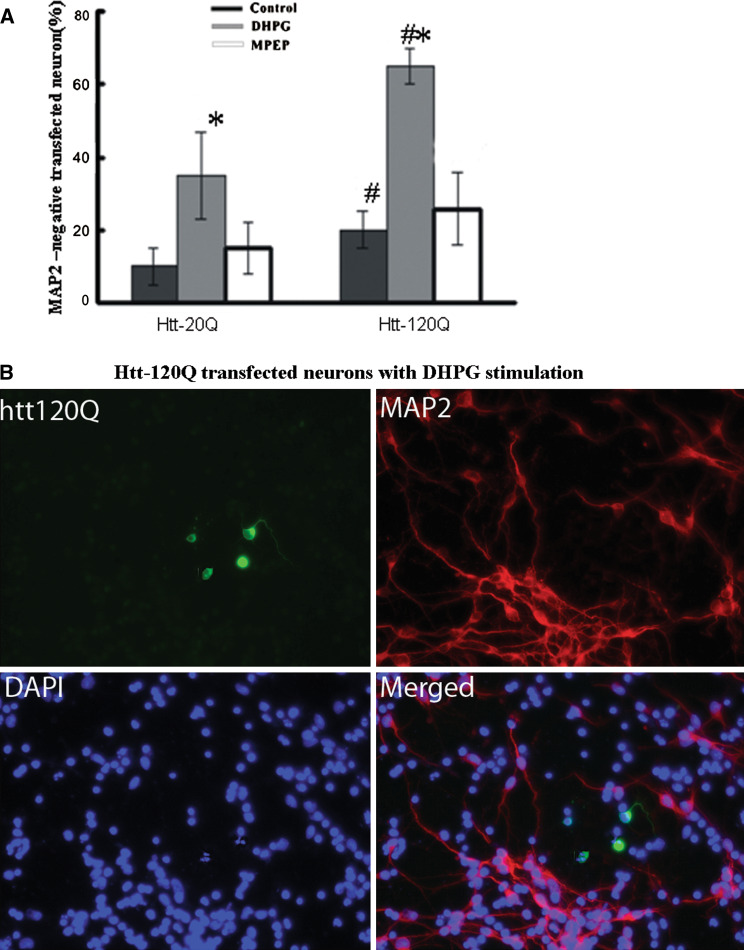

In order to determine whether expression of mutant htt could increase mGluR5-mediated cytotoxicity, we transfected cultured striatal MSNs with constructs expressing the GFP fusion protein containing the first 208 amino acids of human htt with 20Q (htt-20Q) or 120Q (htt-120Q) and cultured these cells with or without Group I mGluRs agonist DHPG (100 μM) for 1 h. Additionally, another group of cultured striatal MSNs were pre-incubated with MPEP, a mGluR5 antagonist, for 30 min before adding DHPG to the cells. In the absence of DHPG, htt-120Q neurons generally showed a decrease in the staining of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), a neuron-specific protein whose decrease reflects early neurodegeneration (Carrier et al. 2006). Following DHPG treatment, the number of MAP2-positive neurons in htt-120Q neuronal culture was significantly decreased as compared with htt-20Q neurons. However, MPEP, the mGluR5 antagonist, could reverse the number of MAP2-positive neurons in the neuronal culture to the same level as each control (htt-20Q or htt-120Q without DHPG). We counted transfected cells without MAP2-staining as neurodegenerative cells to identify mGluR5-mediated excitotoxicity. Although some microscopic fields showed clusters of degenerative cells, we blindly scored more than 300 cells from different (200×) microscopic fields for each group to obtain a representative sample from each slide. Using these criteria, we observed a significant increase in the number of MAP2-negative cells among those DHPG-treated htt-120Q neurons, compared with htt-120Q control neurons without DHPG or with DHPG-treated htt-20Q neurons (Fig. 1a). The fraction of degenerative neurons was 65 ± 5% for those htt-120Q neurons treated with DHPG, whereas only 35% of DHPG-treated htt-20Q neurons or 20% of htt-120Q control neurons were MAP2-negative. Quantitative analysis also showed there was no increase in DHPG-induced neurodegeneration when neurons were pretreated with the mGluR5 blocker MPEP. Also we used the 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole 2hci (DAPI) dye to identify apoptotic cells with nuclear fragmentation (Lei et al. 2008). We observed that a greater number of DHPG-treated htt-120Q neurons showed globular or blebbed nuclei, small and condensed nucleus, or chromatin condensation (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

N-terminal mutant htt fragments enhance mGluR5-mediated excitotoxicity in cultured striatal MSNs. Cultured rat striatal neurons were transfected with GFP-htt-20Q or htt-120Q plasmids for 24 h then stimulated with drugs and labeled by antibodies to MAP2 and DAPI. a The percentage of MAP2-negative transfected neurons without DHPG stimulation or pre-incubated with MPEP 30 min before DHPG stimulation (MPEP). The data (mean ± SEM) were obtained from four to five independent experiments. Within -20Q or -120Q group, * P < 0.05 as compared with control neurons; Between -20Q and -120Q group, # P < 0.05 as compared with identically drug-treated neurons. b MAP2 (red) and DAPI (blue) immunofluorescent labeling of -120Q (green) transfected neurons with DHPG stimulation. Arrows show mutant htt neurons contain smaller, condensed, and fragmented nuclei; 2 μm. (Color figure online)

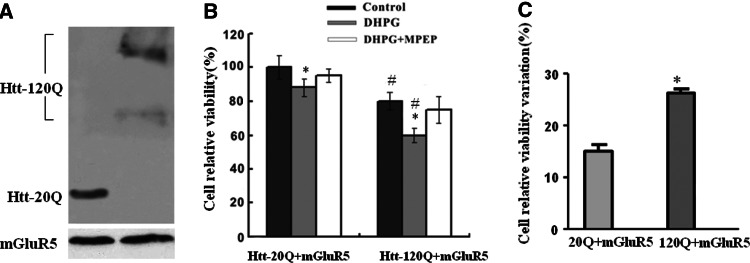

In order to confirm whether expression of N-terminal fragment mutant htt could increase mGluR5-mediated cytotoxicity, we used DHPG-treated HEK293 cells coexpressing mGluR5 and htt-20Q or htt-120Q to verify the observed DHPG-induced neuronal death. Cells transfected with htt-20Q or htt-120Q showed equivalent mGluR5 expression levels, as indicated by immunofluorescence staining and western blot analysis with the mGluR5 specific antibody (Fig. 2a). Transfected HEK293 cells were exposed to 100 μM DHPG for 1 h with or without MPEP pre-incubation. Using 3-(4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays, we found that HEK293 cells coexpressing mGluR5 and htt-120Q showed lower MTT values than cells coexpressing mGluR5 and htt-20Q (Fig. 2b, c). Importantly, the non-competitive mGluR5-selective antagonist MPEP (200 μM) prevented the decrease in MTT value (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

N-terminal mutant htt fragments enhance mGluR5-mediated cell death in HEK293 cells. a Western blotting of HEK293 cells that were co-transfected with mGluR5 and htt-20Q or htt-120Q. The blot was probed with anti-mGluR5 (bottom) and EM 48 (top). b MTT assays of HEK293 cells transfected with mGLuR5 and htt-20Q or htt-120Q and treated without DHPG (control), with DHPG alone, or with DHPG and MPEP (DHPG + MPEP) together. Within htt-20Q or htt-120Q groups, * P < 0.05 as compared with control cells; between htt-20Q and htt-120Q groups, # P < 0.05 as compared with identically drug-treated cells. c The cell relative viability variation was calculated as: (Control − DHPG)/Control × 100%. * P < 0.05 as compared with htt-20Q cells. Data are mean ± SEM of three to five transfections

Activation of mGluR5 Increases JNK and ERK Phosphorylation in HEK293 Cells Expressing N-Terminal Mutant htt

As described earlier, selective activation of mGluR5 induced a rapid and transient JNK and ERK phosphorylation in vivo and in striatal neurons (Choe and Wang 2001; Yang et al. 2006). We first set out to screen the effect of DHPG on the basal phosphorylation of three major MAPK subclasses (ERK, JNK, and p38) in HEK293 cells co-expressing mGluR5 and N-terminal fragments of htt-20Q or htt-120Q. Using immunoblotting, with antibodies that detect the phosphor and total-protein forms, we found that cells exposed to 100 μM DHPG for 5–15 min showed elevated levels of pERK1/2 and pJNK (Fig. 3). However, DHPG did not alter the basal levels of p38 and p-p38 (data not shown). These data demonstrated a positive linkage between mGluR5 and ERK or JNK phosphorylation in vitro. Specifically, the results showed a rapid and transient increase in ERK and JNK phosphorylation which reached its peak at 10 min without significant changes in total ERK and JNK levels. Compared to cells co-expressing mGluR5 and htt-20Q, cells co-expressing mGluR5 and htt-120Q showed a slight increase in the levels of pERK1/2 and pJNK1 (approximately 1.25–1.3-fold of the control cells) after DHPG treatment (Fig. 3a, b). Furthermore, the MAPK activity of MPEP pretreated htt-20Q and htt-120Q cells are the same as controls without DHPG treatment.

Fig. 3.

Activation of mGluR5 increases JNK and ERK phosphorylation in HEK 293 cells expressing N-terminal mutant Htt fragments. HEK293 cells were transfected with mGluR5 and htt-20Q or htt-120Q and either untreated, treated with DHPG, or pre-incubated with MPEP for 10 min before DHPG treatment. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting. a Blots were probed with total ERK and phosphor-ERK specific antibodies. The levels of pERK were quantified and expressed as a ratio (pERK/ERK) for each sample. b Blots were probed with total JNK and phosphor-JNK specific antibodies. The levels of pJNK were quantified and expressed as a ratio (pJNK1/JNK) for each sample. Data are mean ± SEM of three to five transfections. * P < 0.05 as compared with control cells; # P < 0.05 as compared with the same drug-treated cells between htt-20Q and htt-120Q groups

MAPKs are involved in the transcription-dependent regulation of the cellular survival and death (Volmat and Pouyssegur 2001). Although JNK is always associated with cell toxicity, the role of ERK activation in neuronal cells is complex and has been found to be both protective and deleterious (Colucci-D’Amato et al. 2003; Cheung and Slack 2004; Chu et al. 2004). In order to identify the effects of altered MAPKs in mGluR5-mediated cytotoxicity in HEK293 cells expressing N-terminal fragment of mutant htt, we investigated the contribution of activated ERK and JNK to cell viability by pre-incubating the transfected cells with the ERK inhibitor, PD98059 (Kayssi et al. 2007) or the JNK inhibitor, SP600125 (Bennett et al. 2001). Levels of pERK1/2 and pJNK1 were evaluated by immunoblot analysis to determine the ERK and JNK activities. In the presence of the above inhibitors, both levels of pERK1/2 and pJNK1 were reduced to the same basal levels as that of cells expressing htt-20Q (Fig. 4a, b). These results suggest that PD98059 and SP600125 completely blocked DHPG-induced activation of ERK and JNK in HEK293 cells.

Fig. 4.

Activation of mGluR5-mediated ERK/JNK signaling pathway impacts cell viability in the htt-expressing HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells were transfected with mGluR5 and htt-20Q or htt-120Q and treated with or without (control) DHPG, or treated with DHPG by pre-incubation with the ERK pathway inhibitor PD98059 (DHPG + PD98059) or the JNK pathway inhibitor SP600125 (DHPG + SP600125). a Western blotting showed that the ERK inhibitor blocked DHPG-induced ERK activity in htt-expressing HEK293 cells. The blots were probed with total ERK or phosphor-ERK specific antibodies (left panel). The levels of pERK were quantified and expressed as a ratio (pERK/ERK) for each sample (right panel). b Western blotting showed that the JNK inhibitor blocked DHPG-induced JNK activity in htt-expressing HEK293 cells (left panel). The blots were probed with total JNK and phosphor-JNK specific antibodies. The levels of pJNK1 were quantified and expressed as a ratio (pERK/ERK) for each sample (right panel). c, d Cells were treated with drug for 1 h and, 24 h later, were examined by MTT assay. Data are mean ± SEM of three to five transfections. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 as compared with DHPG-treated cells in the same group. e Cell relative viability variation was calculated as: [(DHPG + Inhibitor) − DHPG]/DHPG × 100%, and then the absolute value was taken

We then tested the cell viability in the presence of MAPKs antagonists by MTT assays. Our data showed that decreased activation of ERK was associated with decreased cell viability for all groups of cells, while decreased activation of JNK correlated with increased cell viability (Fig. 4c, d). Compared to cells treated with DHPG alone, the decreased MTT value of cells treated with both DHPG and the ERK inhibitor PD98059 was 22% for htt-20Q cells versus 43% for htt-120Q cells, indicating a greater reduction of viability of htt-120Q cells. However, there was an increased MTT value for the DHPG and the JNK inhibitor SP600125 treated groups (5% for htt-20Q cells vs. 33% for htt-120Q cells) (Fig. 4). Furthermore, we observed that mGluR5-mediated alteration of JNK changes the MTT value more than mGluR5-mediated alteration of ERK, the change of cell relative viability variation between htt-20Q and htt-120Q was 2.3% for PD98059 versus 6.0% for SP600125 (Fig. 4e).

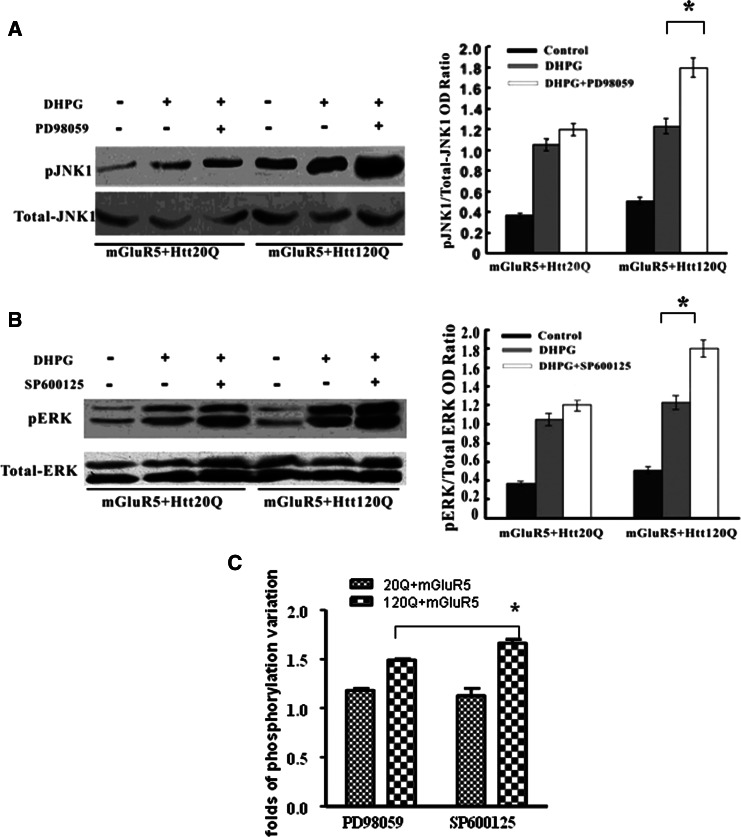

Cross-Talking Between mGluR5-Evoked ERK and JNK Activation in HEK293 Cells Expressing N-Terminal Fragment of Mutant htt

The above results suggest that mutant htt expression alters the mGluR5-induced potentiation of ERK and JNK signaling pathways. In the presence of mutant htt, mGluR5-induced elevation of JNK activity is greater than the increase of ERK activity. These results raise the question of why mutant htt can cause unequal mGluR5-mediated activation of ERK and JNK. Since the ERK and JNK signaling pathways may interact with each other, we then used the ERK antagonist PD98059 to test the DHPG-induced phosphorylation of JNK. On the contrary, the JNK antagonist, SP600125, was also applied to test the DHPG-induced phosphorylation of ERK. The results showed that in mutant htt-transfected cells, DHPG-induced pJNK1 elevated 1.5-fold in the presence of PD98059 compared to that in cells only exposed to DHPG (Fig. 5a). However, DHPG-induced pERK1/2 increased 1.8-fold in the presence of SP600125 (Fig. 5b). For htt-20Q cells, we did not find significant change of DHPC-induced phosphorylation after cells were treated with the antagonist. These data also imply that the antagonist of JNK, SP600125, has a great effect on altering mGluR5-induced ERK activation in the presence of mutant htt (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

mGluR5-induced ERK and JNK signaling pathway in HEK293 cells expressing N-terminal mutant htt fragments. Transient transfections were performed in HEK293 cells with mGluR5 and htt-20Q or htt-120Q constructs with drug treatment. a Western blots of the control, DHPG, DHPG + PD98059 treated cells were probed with total JNK and phosphor-JNK specific antibodies (left panel). The levels of pJNK were quantified and expressed as a ratio (pJNK1/JNK) for each sample (right panel). b Western blots of the control, DHPG, DHPG + SP600125 treated cells were probed with total ERK and phosphor-ERK specific antibodies (left panel). The levels of pERK were quantified and expressed as a ratio (pERK/ERK) for each sample (right panel). c The phosphorylation level variation was counted as DHPG combined inhibitor-treated phosphorylation level versus DHPG-treated level. * P < 0.05; data are mean ± SEM of three to five transfections

Discussion

Our results from cultured primary neurons and transfected HEK293 cells offer the evidence that expression of mutant htt promotes cell death mediated by mGluR5 activation. mGluR5 is a G protein-coupled receptor linked to the activation of phospholipase C, increase in intracellular inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) formation, and the release of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Previous studies demonstrated that mutant htt affects activation of mGluR5 receptor mediated Ca2+ signaling by sensitizing IP3 receptor (InsP3R1) to InsP3 (Tang et al. 2003, 2005). Our results suggest that mutant htt also has direct effects on mGluR5, as a much lower concentration of DHPG can activate mGluR5 in striatal neurons expressing mutant htt. Thus, glutamate signaling via both function-sensitized ionotropic and metabotropic receptors may contribute to MSN degeneration in HD. Although the function of mGluR5 is known to be affected by mutant htt, the role of mGluR5-activated MAPK signaling in mutant htt cells remains unknown. Our studies reveal that mutant htt not only affects mGluR5-evoked MAPK pathways to trigger cell death cascades, but also induces the compensatory downstream events. The evidence for this idea is that mutant htt also increases ERK phosphorylation in cultured cells. Since ERK often promotes cell survival, whereas JNK promotes cell death, mGluR5-induced MAPK alterations can upregulate both protective and deleterious pathways. Thus, the balance between these opposing pathways would determine the ultimate fate of the cell: survival or death. However, mutant htt causes a greater activation of JNK than ERK, which can account for its cytotoxicity.

In Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells, activation of mGluR5 increases ERK phosphorylation in a Ca2+-insensitive manner (Daggett et al. 1995). In striatal neurons, the Ca2+-dependent pathway only leads to the minor activation of ERK (Thandi et al. 2002). Different mGluR5 signaling activities in different cell types could contribute to the selective degeneration of striatal neurons in HD. Since there are two coordinated signaling pathways (a conventional IP3/Ca2+ vs. a Ca2+-independent MAPK pathway) that differentially participate in mGluR5-mediated signaling pathways but have opposing effects on cell survival or death, it is important to selectively inhibit cell death related signaling pathways to prevent striatal neuronal degeneration in HD. Moreover, as our studies suggest that mutant htt can activate mGluR5-mediated MAPK signaling to trigger these two pathways, it will be interesting to investigate how mutant htt activates these pathways, which will help us to develop an effective treatment for HD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 304302620 to H. L.).

Contributor Information

Shan-Shan Huang, Email: shanahuang3@gmail.com.

He Li, Email: heli@mails.tjmu.edu.cn.

References

- Anborgh PH, Godin C, Pampillo M, Dhami GK, Dale LB, Cregan SP, Truant R, Ferguson SS (2005) Inhibition of metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling by the huntingtin-binding protein optineurin. J Biol Chem 41:34840–34848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostol BL, Illes K, Pallos J, Bodai L, Wu J, Strand A, Schweitzer ES, Olson JM, Kazantsev A, Marsh JL, Thompson LM (2006) Mutant huntingtin alters MAPK signaling pathways in PC12 and striatal cells: ERK1/2 protects against mutant huntingtin-associated toxicity. Hum Mol Genet 15(2):273–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal MF, Ferrante RJ, Swartz KJ, Kowall NW (1991) Chronic quinolinic acid lesions in rats closely resemble Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci 11:1649–1659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O’Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y et al (2001) SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:13681–13686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Hayden MR (2004) Deranged neuronal calcium signaling and Huntington disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 322:1310–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Centonze D, Pisani A, Bernardi G (1999) Metabotropic glutamate receptors and cell-type-specific vulnerability in the striatum: implication for ischemia and Huntington’s disease. Exp Neurol 158:97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier RL, Ma TC, Obrietan K, Hoyt KR (2006) A sensitive and selective assay of neuronal degeneration in cell culture. J Neurosci Methods 154:239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Luo T, Wellington C, Metzler M, McCutcheon K, Hayden MR, Raymond LA (1999) Subtype-specific enhancement of NMDA receptor currents by mutant huntingtin. J Neurochem 72:1890–1898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung EC, Slack RS (2004) Emerging role for ERK as a key regulator of neuronal apoptosis. Sci. STKE:PE45 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Choe ES, Wang JQ (2001) Group I metabotropic glutamate receptor activation increases phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein, Elk-1 and extracellular signal-regulated kinases in rat dorsal striatum. Mol Brain Res 94:75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT, Levinthal DJ, Kulich SM, Chalovich EM, DeFranco DB (2004) Oxidative neuronal injury. The dark side of ERK1/2. Eur J Biochem 271:2060–2066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci-D’Amato L, Perrone-Capano C, di Porzio U (2003) Chronic activation of ERK and neurodegenerative diseases. Bioessays 25:1085–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ, Pin JP (1997) Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 37:205–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daggett LP, Sacaan AI, Akong M, Rao SP, Hess SD, Liaw C, Urrutia A, Jachec C, Ellis SB, Dreessen J, Knopfel T, Landwehrmeyer GB, Testa CM, Young AB, Varney M, Johnson EC, Velicelebi G (1995) Molecular and functional characterization of recombinant human metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5. Neuropharmacology 34(8):871–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiglia M (1990) Excitotoxic injury of the neostriatum: a model for Huntington’s disease. Trends Neurosci 13:286–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase K, Schwarz C, Meloni A, Young C, Martin E, Vonsattel JP, Carraway R, Reeves SA, Boyce FM, Aronin N (1995) Huntingtin is a cytoplasmic protein associated with vesicles in human and rat brain neurons. Neuron 14:1075–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco FR, Chen Q, Lamoreaux WJ, Figueredo-Cardenas G, Jiao Y, Coffman JA, Surmeier DJ, Honig MG, Carlock LR, Reiner A (1999) Cellular localization of huntingtin in striatal and cortical neurons in rats: lack of correlation with neuronal vulnerability in Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci 19:1189–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo KA, Johnson GL (2002) Mixed-lineage kinase control of JNK and p38 MAPK pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3:663–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayssi A, Amadesi S, Bautista F, Bunnett NW, Vanner S (2007) Mechanisms of protease-activated receptor 2-evoked hyperexcitability of nociceptive neurons innervating the mouse colon. J Physiol 580(3):977–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y, Garrahan N, Hermann B, Becker DL, Hernandez MR, Boulton ME, Morgan JE (2008) Quantification of retinal transneuronal degeneration in human glaucoma: a novel multiphoton-DAPI approach. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49(5):1940–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S-H, Schilling G, Young WS III, Li X-J, Margolis RL, Stine OC, Wagster MV, Abbott MH, Franz ML, Ranin NG, Folstein SE, Hedreen JC, Ross CA (1993) Huntington’s disease gene (IT15) is widely expressed in human rat tissues. Neuron 11:985–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinissen MJ, Gutkind JS (2001) G-protein-coupled receptors and signaling networks: emerging paradigms. Trends Pharmacol Sci 22:368–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi S (1994) Metabotropic glutamate receptors: synaptic transmission, modulation, and plasticity. Neuron 13:1031–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nance MA (1997) Clinical aspects of CAG repeat diseases. Brain Pathol 7:881–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti F, Bruno V, Copani A, Casabona G, Knopfel T (1996) Metabotropic glutamate receptors: a new target for the therapy of neurodegenerative disorders? Trends Neurosci 19:267–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki K, Nishimura M, Hashimoto N (2001) Mitogen-activated protein kinases and cerebral ischemia. Mol Neurobiol 23:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA (1995) When more is less: pathogenesis of glutamine repeat neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron 15:493–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefer J, Sprunken A, Puls C, Luesse HG, Milkereit A, Milkereit E, Johann V, Kosinski CM (2004) The metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antagonist MPEP and the mGluR2 agonist LY379268 modify disease progression in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Brain Res 1019:246–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey E, Kowall NW, Finn SF, Mazurek MF, Beal MF (1992) The cortical lesion of Huntington’s disease: further neurochemical characterization, and reproduction of some of the histological and neurochemical features by N-methyl-d-aspartate lesions of rat cortex. Ann Neurol 32:526–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Savanenin A, Reddy PH, Liu YF (2001) Polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin promotes sensitization of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors via post-synaptic density 95. J Biol Chem 276:24713–24718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TS, Tu H, Chan EY, Maximov A, Wang Z, Wellington CL, Hayden MR, Bezprozvanny I (2003) Huntingtin and huntingtin-associated protein 1 influence neuronal calcium signaling mediated by inositol-(1,4,5) triphosphate receptor type 1. Neuron 39:227–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T-S, Slow E, Lupu V, Stavrovskaya IG, Sugimori M, Llinas R, Kristal BS, Hayden MR, Bezprozvanny I (2005) Disturbed Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis of medium spiny neurons in Huntington’s disease. PNAS 102(7):2602–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thandi S, Blank JL, Challiss RA (2002) Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors, mGluR1a and mGluR5 couple to extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation via distinct, but overlapping, signaling pathways. J Neurochem 83:1139–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Huntington’s Disease Collaborative Research Group (1993) A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Cell 72:971–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volmat V, Pouyssegur J (2001) Spatiotemporal regulation of the p42/p44 MAPK pathway. Biol Cell 93:71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonsattel JP, DiFiglia M (1998) Huntington disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 57:369–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, Tang Q, Samdani S, Liu Z, Parelkar NK, Choe ES, Yang L, Mao L (2004) Glutamate signaling to Ras-MAPK in striatal neurons: mechanisms for inducible gene expression and plasticity. Mol Neurobiol 29:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Mao L, Chen H, Catavsan M, Kozinn M, Arora A, Liu X, Wang JQ (2006) A signaling mechanism from Gaq-protein-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors to gene expression: role of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. J Neurosci 26:971–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeron MM, Hansson O, Chen N, Wellington CL, Leavitt BR, Brundin P, Hayden MR, Raymond LA (2002) Increased sensitivity to N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-mediated excitotoxicity in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neuron 33:849–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]