Abstract

Advances in transgenic technology as well as in the genetics of Alzheimer disease (AD) have allowed the establishment of animal models that reproduce amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, the main pathological hallmarks of AD. Among these models, 3xTg-AD mice harboring PS1 M146V, APP Swe and tau P301L human transgenes provided the model that most closely mimics human AD features. Although cortical cultures from 3xTg-AD mice have been shown to present disturbances in intracellular [Ca2+] homeostasis, the development of AD pathology in vitro has not been previously evaluated. In the current work, we determined the temporal profile for amyloid precursor protein, amyloid-β and tau expression in primary cortical cultures from 3xTg-AD mice. Immunocytochemistry and Western blot analysis showed an increased expression of these proteins as well as several phosphorylated tau isoforms with time in culture. Alterations in calcium homeostasis and cholinergic and glutamatergic responses were also observed early in vitro. Thus, 3x-TgAD cortical neurons in vitro provide an exceptional tool to investigate pharmacological approaches as well as the cellular basis for AD and related diseases.

Keywords: Amyloid-β, Microtubule-associated protein tau, Amyloid precursor protein, Alzheimer disease, Calcium, Cortical culture, 3xTg-AD mice

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common age-dependent neurodegenerative disorder that accounts for 60–70% of all dementia cases and afflicts more than 15 million individuals worldwide. The disorder is characterized for two hallmark pathologies: amyloid plaques, which consist of the amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) and intraneuronal aggregates composed of the microtubule associated protein tau. During the past two decades, the elucidation of susceptibility and causative genes for Alzheimer disease as well as the identification of the proteins involved in the pathogenic process has greatly facilitated the development of genetically altered mouse models. These models have played a major role in defining critical disease-related mechanisms and evaluating novel therapeutic approaches (Gimenez-Llort et al. 2007; Morrissette et al. 2008). To date, the most complete transgenic mouse model for AD is the 3xTg-AD mice which is characterized by the age-dependent build up of both plaques and tangles (Oddo et al. 2003b) and has proved to be extremely useful to mimic many aspects of the human disease (Oddo et al. 2003a). In the 3xTg-AD mice, the human transgenes are expressed under the transcriptional control of the Thy1.2 cassette (Caroni 1997). Since the expression and activity of Thy1.2-driven transgenes is very low until postnatal day 6–12 (Caroni 1997), this developmental delay could represent a potential drawback for in vitro studies in models obtained from 3xTg-AD mice. However, a threefold increase in the levels of APP and tau proteins has been shown in brain regions from embryonic day 15 (E15) 3xTg-AD mice (Smith et al. 2005b), and primary cortical cultures from embryonic and adult 3xTg-AD mice showed disturbances on intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis (Smith et al. 2005b; Gandia et al. 2008). Although primary cortical cultures from 3xTg-AD mice could provide a valuable tool for AD-related research, the temporal profile of Aβ and tau expression in this system has not been examined in detail, yet. Due to the high cost in terms of money and time of in vivo models for AD, the development of in vitro models able to completely reproduce the main hallmarks of AD at the molecular and cellular level seems of particular interest. Therefore, in this work we aim to characterize the expression of amyloid-β, amyloid precursor protein (APP) and tau expression in primary cortical neurons from 3xTg-AD mice. The suitability of primary cortical cultures from 3xTg-AD mice as an in vitro model for preliminary screening of therapies for AD as well as to study the cellular pathways involved in this disease has been evaluated by immunocytochemistry, Western blot and calcium fluorescence.

Methods

Animals and Cortical Cultures

A colony of homozygous 3xTg-AD mice and wild-type non-transgenic (NonTg) littermates was established at the animal facilities of the University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, where animals were used to obtain primary cortical cultures. All protocols were revised and approved by the University of Santiago de Compostela Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Primary cortical neurons were prepared from embryonic day 15–18 (E15–18) NonTg and homozygous 3xTg-AD mice as previously described (Vale et al. 1998, 1999; Garcia et al. 2006). Briefly, cerebral cortices were removed and dissociated by mild trypsinization at 37°C, followed by trituration in a DNAse solution (0.005% w/v) containing a soybean trypsin inhibitor (0.05% w/v). The cells were suspended in DMEM supplemented with p-amino benzoate, insulin, penicillin and 10% foetal calf serum. The cell suspension was seeded in 18 mm glass coverslips precoated with poly-d-lysine and incubated in 12 multiwell plates for 6–14 days in vitro (div) in a humidified 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere at 37°C. Cytosine arabinoside, 20 µM was added before 48 h in culture to prevent glial proliferation. Cortical neurons from control and 3xTg-AD mice were prepared and processed simultaneously.

Immunocytochemistry

For immunocytochemistry, NonTg and 3xTg-AD cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and subsequently labelled with the following primary antibodies: anti-APP/Aβ (NAB228: 1:50, Cell Signaling), anti Aβ 6E10 (raised against amino acids 1–16 of Aβ, 1:500, Signet), Tau 46 (Total Tau 1:500, Cell Signaling), anti-human tau HT7 (1:200, raised against amino acids 159–163), anti tau AT8 (recognizes phosphorylated Ser202, Thr205, 1:100), anti-tau AT100 (1:100, recognizes phosphorylated Thr 212 and Ser 214) and anti-tau AT270 (1:100, recognizes phosphorylated Thr 181), all of them from Thermo Scientific. Immunoreactivity was visualized using a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution, Molecular Probes, USA). Simultaneously, the neuronal actin cytoskeleton was stained with Oregon Green514 Phalloidin, which binds specifically to F-actin. The cells were incubated with 10 nM Oregon Green 514 Phalloidin in 1% BSA in phosphate buffered saline. For the human tau HT7 antibody, co-staining of the cortical neurons was performed in the presence of anti-tubulin fluor 488 conjugated. After washing, the coverslips were then mounted in 50% glycerol/NaCl/Pi and sealed with nail polish. Cells were analyzed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon, Mellville, NY) with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera (Hamamatsu Photonics KK, Japan).

Immunocytochemistry controls for the specificity of the detection methods were carried out by omitting the incubation step with the primary antibodies in one of each four consecutive coverslips. None of the coverslips run without primary antibody showed specific labelling comparable to that obtained with the primary antibodies. For confocal analysis, all laser parameters were first adjusted in control neurons and left unchanged for the analysis of the corresponding 3xTg-AD neurons.

Western Blotting

Cultured neurons were washed with cold PBS and lysed in 50 mM Tris—HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT, 2.5 mM PMSF, 40 mg/ml aprotinin, 4 mg/ml leupeptin, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mg/ml pepstatin A and 1 mg/ml benzamidine. Total protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay, with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Aliquots of cell lysates containing 20 µg of total protein in gel loading buffer (50 mM Tris—HCl, 100 mM dithiotreitol, 2% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.05% bromophenol blue, pH 6.8) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). The Snap i.d. protein detection system (Millipore) was used for blocking and antibody incubation. Non-specific binding was blocked with 0.25% non-fat dry milk dissolved in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20. The membranes were incubated with the same antibodies used for immunocytochemistry experiments. After removal of primary antibody, the membranes were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 10 min. The immunoreactive bands were detected using the supersignal west pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) and the Diversity 4 gel documentation and analysis system (Syngene, Cambridge, UK). Chemiluminescence was measured with the Diversity GeneSnap software (Syngene). The same membranes were stripped and reproved with anti-β-actin (BD Biosciences) as control for lane loading. Band intensity was analyzed off line by the Diversity Genetools software (Syngene) after correction for the intensity of the β-actin band. Values were expressed as the ratio of mean intensity for each antibody band divided by the β-actin band for each experimental condition.

ELISA

Extracellular amyloid beta in the culture medium was evaluated by the amyloid-β1–42 ELISA kit (SIGNET), following manufacturer protocols. Briefly, the kit provides coated plates with antibody that captures the Amyloid-β1–42 peptide by the amino-terminal. Standards containing known amounts of Aβ1–42 peptide and culture medium collected from control and 3xTg-AD cultures, at the same developmental stage, with unknown amounts of Aβ1–42 peptide were added to the wells and incubated. The plate was washed to remove unbound peptide and incubated for 2 h in the presence of a primary antibody that binds to the carboxy-terminal of the Aβ1–42 peptide. After incubation and washing, a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was added. After 25 min incubation, the plate was washed and the OPD substrate to visualize the bound Aβ1–42 peptide was added. The optical density was read at 495 nm in a Chamaleon multiwell plate reader.

Cell Labelling and Determination of the Cytosolic Calcium Concentration [Ca2+]c

Cultured cortical neurons of 6–10 days in vitro from NonTg and 3xTg-AD mice were loaded with the Ca2+ sensitive fluorescent dye Fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (Fura-2 AM; 2.5 µM) for 10 min at 37°C. After incubation, the loaded cells were washed three times with cold buffer. The glass coverslips were inserted into a thermostated chamber at 37°C (Life Science Resources, Royston, Herts, UK), and cells were viewed with a Nikon Diaphot 200 microscope, equipped with epifluorescence optics (Nikon 40-immersion UV-Fluor objective). The thermostated chamber was used in the open bath configuration, and additions were made by removal and addition of fresh bathing solution. The [Ca2+]c images were obtained from the images collected by double excitation fluorescence with a Life Science Resources equipment. The light source was a 175 W xenon lamp, and light reached the objective with an optical fibre. The excitation wavelengths for Fura were 340 and 380 nm, with emission at 505 nm. The calibration of the fluorescence versus intracellular calcium was made by using the method described by Grynkiewicz et al. (1985). For calcium imaging, experimental solutions were based on Locke’s buffer containing (in mM): 154 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5.6 Glucose, 3.6 NaHCO3 and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 adjusted with Tris. The pH of the buffer containing the different drugs used in this study was adjusted to 7.4 with Tris before addition to the cells. All experiments were carried out in duplicated.

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test was used to assess whether significant differences existed between neurons from control and 3xTg-AD cultures. All values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

In order to characterize the levels of expression of APP, Aβ and tau in primary cortical neurons from 3xTg-AD and NonTg mice, immunocytochemistry and Western blot techniques were employed. Primary cortical neurons from 3xTg-AD and control mice were always prepared, plated and processed simultaneously at all the developmental points evaluated.

APP and Aβ Expression in Primary Cortical Neurons from 3xTg-AD Mice

The Aβ peptide has been hypothesized to cause the pathologic and behavioral manifestations of AD, including synaptic dysfunction and loss, neurofibrillary tangle formation, neuronal degeneration, and impaired memory. In fact, intraneuronal Aβ immunoreactivity is one of the earliest neuropathological manifestations in 3xTg-AD mice, first detectable in neocortical regions and is apparent between 3 and 4 months of age in the neocortex of 3xTg-AD mice (Oddo et al. 2003a). In order to characterize Aβ expression in cortical cultures from 3xTg-AD mice, we first evaluated the expression of both APP and Aβ using two different primary antibodies.

First, the expression of the APPSWE transgene product was evaluated with the anti-APP/Aβ mouse monoclonal antibody NAB228 which recognizes the residues 1–11 of the human beta amyloid peptide and full length APP, sAPP species excluding sAPPβ, C99 and Aβ. Although this antibody recognizes both the phospho and non-phospho forms of the protein, it has been shown to prefer the phosphorylated form in some systems (Levin et al. 1990). The antibody used in this study has been shown to cross-react with human, monkey and bovine sequences. Figure 1 shows staining with this antibody in cultured neurons from control and 3xTg-AD mice at different days in vitro (div). At 8 div APP/Aβ immunoreactivity was diffused in the cell bodies and neurites of control neurons (Fig. 1a); however, it was more intense in the cell bodies and neurites of cultured 3xTg-AD neurons (Fig. 1b). More evident differences in APP/Aβ expression between control (Fig. 1c) and 3xTg-AD neurons (Fig. 1d) were observed at 11 div. Again APP/Aβ expression was faint and restricted to cell bodies and neurites in control neurons, whereas transgenic neurons showed intense immunoreactivity all over the cell body and covering the nuclei in some of the neurons. Western blot analysis of APP/Aβ expression in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div using the NAB228 antibody is shown in Fig. 1e. Quantification of the western band intensity showed a significant (P = 0.01) threefold increase in APP/Aβ immunoreactivity in 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div (Control = 8.5 ± 0.2; 3xTg-AD = 28.1 ± 3.1). Next, Aβ expression was evaluated in primary cultures of cortical neurons using the human specific 6E10 antibody, which reacts with abnormally processed isoforms and precursor forms of the protein. Figure 2 shows immunocytochemistry and Western blot results with 6E10 corroborating the overexpression of Aβ in cultured transgenic neurons both at 8 and 11 div. Control neurons of 8 div exhibited a weak cytoplasmatic immunoreactivity with antibody 6E10 (Fig. 2a), whereas an intense staining was observed in most of the cultured 3xTg-AD neurons at the same time in culture (Fig. 2b) and in this case many neurons showed an increase in fluorescence all over the cell bodies and nuclei. A similar situation was found for control and 3xTg-AD cultures of 11 days in vitro (Fig. 2c, d). Figure 2e shows 6E10 western bands in control and 3xTg-AD neurons. Quantification of the western band intensity yielded a significant (P = 0.01) three- to five-fold increase in Aβ expression in 3xTg-AD neurons of 8 and 11 div, respectively (Fig. 2f). Since there is a strong correlation between soluble Aβ levels and the extent of synaptic loss and cognitive impairment in AD (McLean et al. 1999), secreted Aβ1–42 was detected in the culture medium using sandwich ELISA selective for Aβ1–42 peptides. The human Aβ1–42 peptide used in this kit shows an estimated 21% cross-reactivity with rodent Aβ1–42 peptide. Figure 2g shows a two-fold increase in extracellular Aβ1–42 steady-state levels in 3xTg-AD neurons of 7 div (P < 0.05 versus control neurons), whereas at 11 div secreted Aβ1–42 levels were three-fold higher in 3xTg-AD neurons. No differences in secreted Aβ levels between control cultures of 7 and 11 div were found and data from control neurons at both developmental stage were pooled together.

Fig. 1.

Confocal images showing APP/Aβ immunoreactivity (red) and co-staining of the cells with Oregon green 514 phalloidin (green) in control and 3xTg-AD neurons as measured with the antibody NAB228 that detects endogenous levels of APP/β-amyloid. a Control neurons of 8 div. b 3xTg-AD neurons of 8 div. c Control neurons of 11 div. d 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div. Scale bar is 20 µm. e Western blot analysis of APP and Aβ levels in control and 3xTg-AD cultures of 11 div. The upper panel shows APP/Aβ levels detected with the NAB228 antibody. In the lower panels, the same membranes were reblotted for β-actin. Representative of three experiments. f Mean of the ratio of the APP/actin band intensity in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div obtained from three different cultures. (Color figure online)

Fig. 2.

Overexpression of Aβ in 3xTg-AD cultures. The confocal images show Aβ immunoreactivity in control and 3xTg-AD neurons detected with the antibody 6E10 (red) and co-staining of the cells with Oregon green 514 phalloidin (green). a Control neurons of 8 div. b 3xTg-AD neurons of 8 div. c Control neurons of 11 div. d 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div. Scale bar is 20 µm. e Western blot analysis of Aβ levels in control and 3xTg-AD cultures of 11 div. The upper panel shows Aβ levels detected with the 6E10 antibody. In the lower panels, the same membranes were reblotted for β-actin. Representative of three experiments. f Mean of the ratio of the Aβ/actin band intensity in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div, obtained from three different cultures. g Extracellular levels of Aβ1–42 in the culture medium of control non 3xTg-AD and 3xTg-AD neurons as measured by ELISA. (Color figure online)

Human Tau Expression in Cortical Cultures of 3xTg-AD Neurons

A number of antibody epitopes have been described that distinguish Alzheimer tau from tau in normal brain tissue and are thus of diagnostic value. Many of these depend on phosphorylation, especially at Ser-Pro or Thr-Pro motifs, indicating an overactivity of proline-directed kinases or an underactivity of the corresponding phosphatases. While Alzheimer tau shows an elevated phosphorylation (Köpke et al. 1993), non-Alzheimer tissue also shows some phosphorylation at similar sites. This is particularly visible in biopsy material or fetal tissue (Zheng-Fischhofer et al. 1998). The tau pathology in 3xTg-AD mice in vivo closely mimics the distribution pattern that occurs in human AD brains initiating within pyramidal neurons of the CA1 hippocampus subfield and then later progresses to involve cortical structures (Oddo et al. 2003b).

The expression of tau was investigated by immunocytochemistry and Western blot with several antibodies against normal tau and its phosphorylated isoforms to evaluate the presence of tau pathology in primary cultures of 3xTg-AD neurons.

First, tau immunoreactivity in vitro was evaluated initially with the tau 46 antibody that recognizes steady-state levels of tau and binds to all six isoforms of the protein. This antibody cross-reacts with mouse, rat and human sequences. Figure 3 shows total tau immunoreactivity in control and 3xTg-AD cortical cultures. At 8 div, control neurons showed expression of the protein in neurites and cytoplasm (Fig. 3a). The pattern of tau expression was similar in cortical neurons from 3xTg-AD mice; however, staining was more intense in transgenic neurons (Fig. 3b). The differences in tau expression between control and 3xTg-AD neurons increased with time in culture and tau immunoreactivity was greatly increased in 3xTg-AD neurons versus control neurons at 11 div (Fig. 3c, d). Western blot analysis of tau expression in control and 3xTg-AD neurons showed a significant (P = 0.02) three-fold increase in tau levels in transgenic neurons of 11 div versus control neurons (Fig. 3e, f).

Fig. 3.

Total tau overexpression in cultured cortical 3xTg-AD neurons. The confocal images show tau immunoreactivity in control and 3xTg-AD neurons as measured with the Tau 46 antibody (red) and co-staining of the cells with Oregon green 514 phalloidin (green). a Control neurons of 8 div. b 3xTg-AD neurons of 8 div. c Control neurons of 11 div. d 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div. Scale bar is 20 µm. e Western blot analysis of total tau levels in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div. The upper panel shows tau levels detected with the tau 46 antibody. In the lower panels, the same membranes were reblotted for β-actin. Representative of three experiments. f Mean of the ratio of the tau/actin band intensity in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div obtained from three different cultures. (Color figure online)

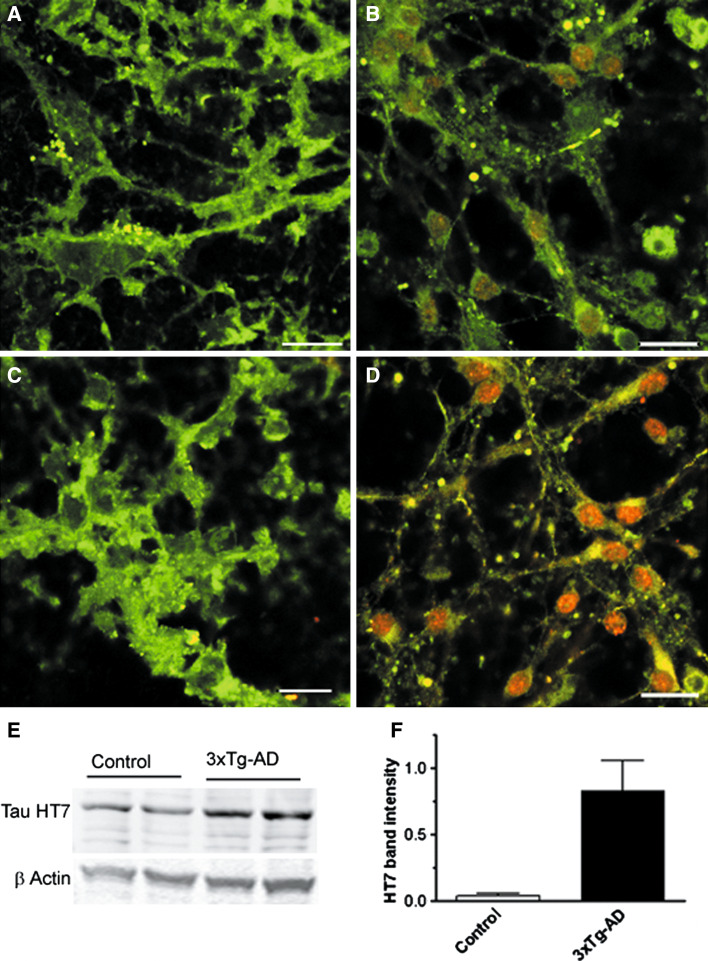

We next evaluated the expression of human tau in control and 3xTg-AD neurons using the human specific anti-tau monoclonal HT7 antibody. This antibody recognizes normal tau from human and bovine brain and PHF-tau and does not cross-reacts with tau from rat brain. The epitope of this antibody has been mapped on human tau between residues 159 and 163. Figure 4 shows confocal microscopy images indicating tau HT7 immunoreactivity in control and 3xTg-AD cultures. HT7 immunoreactivity was absent in neurites and cytosol in control cells of 8 div; however, some punctated staining associated to cellular debris was observed (Fig. 4a). However, at the same developmental stage, HT7 immunoreactivity was intense in 3xTg-AD cells and appeared to be covering all the cell body (Fig. 4b). A similar situation was found at longer culture periods as shown at 11 div for control (Fig. 4c) and 3xTg-AD neurons (Fig. 4d), therefore indicating an increase in the amount of human tau in primary cultures from 3xTg-AD mice. Figure 4e shows immunoblot bands for tau HT7 in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div. As observed in the immunocytochemistry experiments, a weak immunoreactive band was also detected in control neurons. Since tau HT7 is a human specific antibody, the weak band observed in control cultures is most likely to the binding of the antibody to cellular debris. Quantification of Western blot data for HT7 yielded a significant increase of about 20-fold (P = 0.04) for tau HT7 immunoreactivity in 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div (Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

Confocal microscopy images indicating human tau immunoreactivity in control and 3xTg-AD cultures of different developmental stages. Human tau was detected with the anti-tau HT7 antibody raised against residues 159–163 of the protein (red) and co-staining of the cells was performed with tubulin fluor 488-conjugated (green). a Control cells of 8 div. b 3xTg-AD cells 8 div. c Control cell 11 div. d 3xTg-AD cells 11 div. Scale bar is 20 µm. e Western blot analysis of HT7 levels in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div. The upper panel shows tau levels detected with the HT7 antibody. In the lower panels, the same membranes were reblotted for β-actin as loading control. Data representative of three experiments. f Mean of the ratio of the tau/actin band intensity in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div obtained from three different cultures. (Color figure online)

Tau is Hyperphosphorylated in Primary Cultures from 3xTg-AD Mice

Tau is typically hyperphosphorylated in paired helical filaments and Alzheimer brain cytosol (Iqbal and Grundke-Iqbal 2006). Therefore, we investigated the presence of abnormal phosphorylation of tau in cultures from transgenic and control mice by immunocytochemical and Western blot analyses using phosphorylation-dependent anti-tau antibodies. Among these antibodies, the phospho-tau antibody AT8 which recognizes a tau epitope doubly phosphorylated at serine 202 and threonine 205 (Porzig et al. 2007) was employed in immunocytochemistry and Western blot experiments. This antibody does not cross-react with normal tau sequences. Figure 5 shows that at 8 div in control cells AT8 immunoreactivity was very diffuse in cytosol and neurites (Fig. 5a), whereas a marked increase in the expression of the protein is obvious in the cell bodies and neurites of 3xTg-AD neurons (Fig. 5b) at the same developmental stage. Similarly, at 11 div control cells showed a diffuse staining (Fig. 5c) in the cytosol and neurites, whereas AT8 immmunoreactivity was increased in 3xTg-AD cells, with some cells showing also nuclear staining (Fig. 5d). Western blot analysis of AT8 expression in control and 3xTg-AD cultures was also performed at different times in culture. A representative Western blot of phospho tau expression, evaluated with the anti tau AT8 antibody, in control and 3xTg-AD cultures of 11 div is shown in Fig. 5e. In agreement with the immunocytochemistry experiments, AT8 western bands in control cells were weak and its intensity was increased in transgenic cultures. At this developmental stage, quantification of Western blot data for AT8 expression in control and 3xTg-AD neurons yielded a significant seven-fold increase (P = 0.002) in the levels of tau AT8 in primary cortical cultures from transgenic mice (Fig. 5f).

Fig. 5.

Phosphorylated tau immunoreactivity in control and 3xTg-AD cultures as detected with the phospho-tau antibody AT8 (tau phosphorylated at Ser202 and Thr205). Anti-tau AT8 immunoreactivity is shown in red and simultaneous co-staining of the cells was performed with Oregon green 514 phalloidin (green). a Control cells of 8 div. b 3xTg-AD cells 8 div. c Control cells 11 div. d 3xTg-AD cells 11 div. Scale bar is 20 µm. e Western blot analysis of phosphorylated tau levels in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div using the same antibody. The upper panel shows tau levels detected with the AT8 antibody. In the lower panels, the same membranes were reblotted for β-actin as loading control. Representative of three experiments. f Mean of the ratio of the tau/actin band intensity in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div obtained from three different cultures. (Color figure online)

Among the phosphorylation-dependent anti-tau antibodies, AT100 is one of the most widely used of these antibodies by virtue of the fact that it is a sensitive probe for staining tau pathology in brain (Mercken et al. 1992). Therefore, phosphorylation of tau in control and 3xTg-AD neurons was also evaluated with the anti-tau AT100 antibody, which recognizes tau phosphorylated at serine 212 and threonine 214. Figure 6 shows anti-tau AT100 immunoreactivity in control and 3xTg-AD neurons. At 8 div, control cells (Fig. 6a) showed a punctuate staining in neurites and some staining in cell bodies. However, at the same time in culture AT100 staining in cell bodies of 3xTg-AD neurons was clearly increased and, in some cases, the nuclei of 3xTg-AD neurons were not distinguishable from the rest of the cell body (Fig. 6b). At 11 div, the differences in AT100 immunoreactivity between control and 3xTg-AD neurons were even more easily perceptible in the immunocytochemistry experiments (Fig. 6c, d). Moreover, Western blot analysis of AT100 levels in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div showed a marked increase in AT100 band intensity in 3xTg-AD neurons as shown in Fig. 6e. At this time in culture, a weak immunoreactive band was observed in control neurons, whereas transgenic neurons showed a clear increase in AT100 band intensity. Quantification of the levels of AT100 from three different cultures of control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div yielded a significant (P = 0.008) increase in AT100 levels in 3xTg-AD neurons (Fig. 6f).

Fig. 6.

Confocal microscopy image showing phosphorylation of tau in control and 3xTg-AD neurons using the antibody anti-tau AT100 (tau phosphorylated at Thr212 and Ser214). Anti-tau AT100 immunoreactivity is shown in red and simultaneous co-staining of the cells was performed with Oregon green 514 phalloidin (green). a Control cells of 8 div. b 3xTg-AD cells 8 div. c Control cell 11 div. d 3xTg-AD cells 11 div. Scale bar is 20 µm. e Western blot analysis of phosphorylated tau levels in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div using the same antibody. The upper panel shows tau levels detected with the AT100 antibody. In the lower panels, the same membranes were reblotted for β-actin as loading control. Data are representative of three different experiments. f Mean of the ratio of the tau/actin band intensity in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div obtained from three different cultures. (Color figure online)

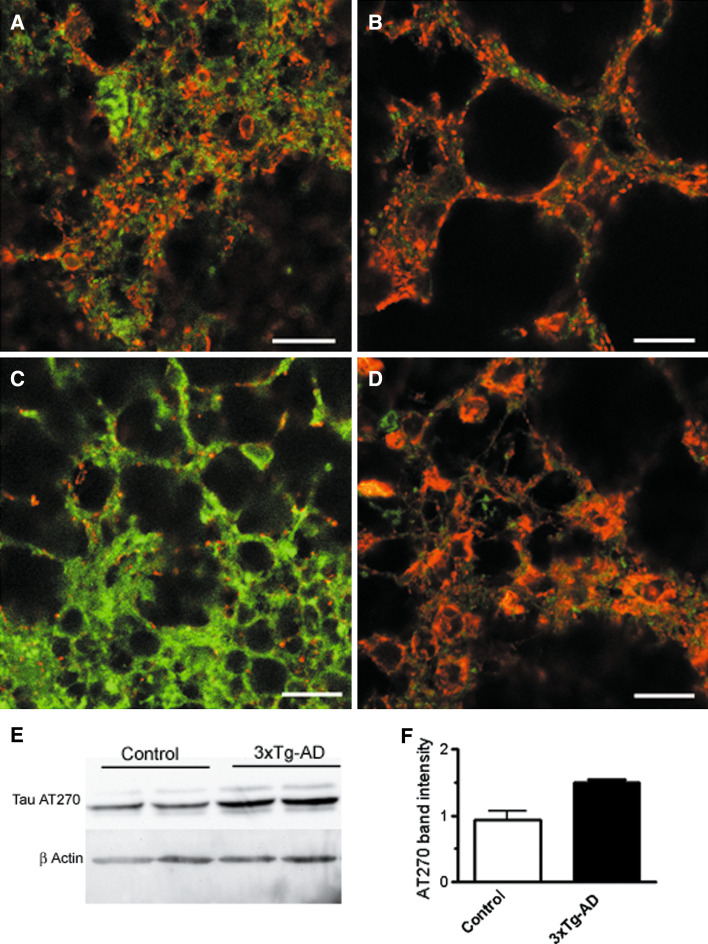

Finally, we evaluated the levels of expression of tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 using the antibody anti-tau AT270. This antibody recognizes PHF-tau, tangles and neurofilaments and cross-reacts weakly with normal tau. Figure 7 shows that AT270 immunoreactivity in control neurons of 8 div (Fig. 7a) was very diffuse in cell bodies and punctuate in neurites. In 3xTg-AD neurons of 8 div, AT270 immunoreactivity (Fig. 7b) was increased and many cells showed intense labelling in cell bodies. At 11 div, AT 270 staining in control cells was weak (Fig. 7c); however, most of the cells still showed a diffuse staining in cell bodies and neurites. In contrast, AT270 immunoreactivity in 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div (Fig. 7d) covered both the cell bodies and neurites of the vast majority of the cells in the field. A representative Western blot image of AT270 levels in control and 3xTg-AD cultures of 11 div is shown in Fig. 7e. Quantification of the AT270 bands obtained from three different cultures yielded a significant increase of about 50% in AT270 levels in 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div (Fig. 7f). Thus, tau is hyperphosphorylated at multiple residues in primary cortical cultures from the 3xTg-AD mice as occurs in AD brains.

Fig. 7.

Tau hyperphosphorilation in 3xTg-AD neurons as detected with the anti-tau AT270 antibody that shows tau phosphorylation at Thr181. Anti-tau AT270 immunoreactivity is shown in red and simultaneous co-staining of the cells was performed with Oregon green 514 phalloidin (green). a Control neurons of 8 div. b 3xTg-AD neurons 8 div. c Control neurons of 11 div. d 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div. Scale bar is 20 µm. e Western blot analysis of phosphorylated tau levels in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div using the same antibody. The upper panel shows tau levels detected with the AT270 antibody. In the lower panels, the same membranes were reblotted for β-actin. Representative of three experiments. f Mean of the ratio of the tau/actin band intensity in control and 3xTg-AD neurons of 11 div obtained from three different cultures. (Color figure online)

Primary Cortical Cultures from 3xTg-AD Mice Show Altered Calcium Homeostasis and Decreased Response to Glutamate and Acetylcholine

Recent developments point to a critical role for calcium dysregulation in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (Green and LaFerla 2008) and previous studies have shown enhanced Ca2+ responses to caffeine in 3xTg-AD cortical neurons in culture (Smith et al. 2005b). Therefore, we evaluated calcium homeostasis and neurotransmitter functionality in vitro by single cell fluorimetric analysis of calcium responses. Figure 8 shows an altered calcium homeostasis and decreased glutamatergic and cholinergic responses in cortical neurons from 3xTgAD mice. As shown in Fig. 8a, primary cortical neurons from 3xTg-AD mice showed a higher response to ionomycin when added in calcium free-medium, indicating an increase in the calcium release from intracellular stores. Additionally, addition of either 200 µM acetylcholine (Fig. 8b) or 50 µM glutamate (Fig. 8c) caused a smaller calcium increase in 3xTg-AD neurons, possibly indicating a decreased functionality of both acetylcholine and glutamate receptors in the in vitro model.

Fig. 8.

Calcium homeostasis is altered in cortical cultures from embryonic 3xTg-AD mice. a Calcium release from intracellular calcium stores is increased in primary cultures of 3xTg-AD neurons as evidenced after addition of ionomycin in a calcium-free medium. b Acetylcholine-evoked calcium entry is decreased in 3xTg-AD neurons and glutamate-induced calcium increase is also decreased in primary cortical cultures from 3xTg-AD mice. c Addition of drugs is indicated by the arrows. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of three different experiments, all performed in duplicate in cortical cultures from 6 to 10 div

Discussion

The results presented in this work provide the first analysis of the temporal profile of APP, Aβ and tau expression in primary cortical cultures from 3xTg-AD mice. During the last decade, excellent opportunities to screen drugs against Alzheimer disease have been provided by animal models of the disease. From these models, triple-transgenic 3xTg-AD mice most completely mimic the disease in humans (Oddo et al. 2003b). The neuropathological correlates of Alzheimer’s disease include amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. In these mice, the mouse Thy1.2 expression cassette has been demonstrated to drive transgene expression predominantly to the CNS (Caroni 1997); however, expression of the cassette driven transgenes seems to be low until postnatal day 6. Although primary cortical neurons established from embryos of 3xTg-AD mice have been previously shown to present alterations in intracellular calcium homeostasis (Smith et al. 2005b), there is no evidence of the in vitro pattern of expression of Aβ, tau and APP. Since relevant regions for AD, including the hippocampus and cerebral cortex, are among the regions containing the highest steady-state levels of the transgene-derived human APP and tau proteins (Oddo et al. 2003b), we sought to characterize the expression of these proteins in vitro. Using antibodies that recognize both human and mouse APP or tau, we evaluated the temporal profile for the expression of these proteins in primary cultured cortical neurons.

Primary cortical cultures from embryonic 3xTg-AD mice have previously been shown to present alterations in Ca2+ stores (Smith et al. 2005b) and disturbances in the intracellular calcium homeostasis are known to play a major role in AD pathology (Smith et al. 2005a). Therefore, the determination of the temporal profile for the overexpression of APP, Aβ and tau could provide a valuable tool to evaluate the potential effectiveness of AD treatments and therapies and to investigate the molecular basis of this disease. In embryonic 3xTg-AD mice brain, APP and tau levels were found to be three times elevated (Smith et al. 2005b); however, the expression of these proteins in vitro was not previously evaluated. Since the expression of the Thy1.2 gene products has been reported to be low until postnatal day 6 (Caroni 1997), it could represent a potential limitation for the use of the in vitro AD model. Therefore, we characterized the expression of APP, Aβ and tau in primary cortical neurons established from embryonic 3xTg-AD mice.

We found that the APP levels were dramatically increased in primary cortical cultures from 3xTg-AD mice as early as 8 div, and the differences between control and 3xTg-AD cultures increased with the time in culture. The increase in APP levels with neuronal differentiation is in agreement with previous reports indicating that neuronal differentiation is accompanied by increased APP expression and membrane retention of the protein as intact, full-length molecules that could serve as potential substrates for amyloidogenesis (Hung et al. 1992). In addition, we also observed an increase in Aβ levels in cortical cultures from 3xTg-AD mice. The increase in Aβ immunoreactivity was already evident in transgenic neurons of 6 div (data not shown), the earliest time in culture analyzed in this study. This finding is of particular importance since it is known that intraneuronal Aβ accumulation initiates the cognitive deficits associated with Alzheimer disease (Billings et al. 2005). Therefore, an early in vitro overexpression of Aβ highly increases the potential of in vitro cultures from 3xTg-AD mice to evaluate the cellular mechanisms associated with AD. Furthermore, biochemical analysis of Aβ levels by ELISA indicated that the levels of Aβ1–42 released to the culture medium were increased in cultures obtained from 3xTg-AD mice. The increased expression of Aβ in vitro was somehow unexpected since previous studies found similar Aβ levels in the brain of 3xTg-AD and control mice of 2 months of age. However, in control mice Aβ did not increase with age, whereas the levels in the 3xTg-AD mice steadily increased with age (Oddo et al. 2003b). The early overexpression of Aβ in cultured neurons from 3xTg-AD embryos could be attributable to unknown factors in the culture medium that modulate the expression of the Thy1.2 transgene products. It must be pointed out that the increase in intra- and extraneuronal Aβ in cultured 3xTg-AD neurons is relevant for the use of the in vitro model in AD-related research and to study the signalling pathways involved in the establishment of learning and memory. In fact, immediate-early genes relevant to learning and memory, such as Zif268, Nurr77, and Arc, are downregulated in areas of extracellular Aβ accumulation (Dickey et al. 2004).

Next, we evaluated the levels of tau expression in primary cortical cultures from 3xTg-AD mice. Although the gene encoding tau is not genetically linked to AD, this should not imply that tau pathology is irrelevant or innocuous in the pathogenesis of AD, because neurodegeneration induced by tau dysfunction has been described to play a pivotal role in the disease. In fact, tau pathology can be triggered by different mechanisms, both dependent and independent of Aβ (LaFerla and Oddo 2005). The simultaneous overexpression of tau and Aβ in mice and for instance in vitro seems crucial for studies of the molecular relationship between Aβ and tau and to test the effectiveness that anti-AD interventions have on both pathologies. This aspect has been highlighted by the observation that compounds designed to ameliorate AD pathology can have different effects on either Aβ or tau (Oddo et al. 2005). The results presented in this study indicate that the tau protein and several of its phosphorylated isoforms are overexpressed in cortical 3xTg-AD cultures at early stages in vitro. The tau protein consists of 441-amino-acid-long sequences and many anti-tau antibodies have been shown to recognize different sites of abnormal phosphorylation in AD. Increases for all the tau isoforms analyzed in this work were evident in primary cultures of 3xTgAD mice already at 6 div (data not shown). This fact is relevant for the use of the in vitro model to evaluate pharmacological approaches to AD since neurofibrillary degeneration is apparently required for the clinical expression of AD.

In the last years it has become evident that calcium homeostasis is altered in Alzheimer disease (Smith et al. 2005a; Green and LaFerla 2008). The results presented in this work are in agreement with the reported increase in the release of calcium from intracellular stores in cultured cortical 3xTg-AD neurons (Stutzmann et al. 2004, 2007; Smith et al. 2005b). Furthermore, glutamate and acetylcholine evoked calcium responses were decreased in cultured 3xTg-AD neurons. Therefore, this in vitro model could provide an excellent tool to evaluate the role of acetylcholine and glutamate neurotransmission in AD. The decrease in the calcium responses to acetylcholine and glutamate in 3xTg-AD cultures indicates that glutamatergic and cholinergic neurotransmission are compromised in the in vitro model as previously reported in vivo (Oddo and LaFerla 2006; Walton and Dodd 2007). Since two of the major neurochemical features of AD are the marked reduction of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and the altered glutamatergic neurotransmission, more work should be performed to elucidate the mechanisms that cause the in vitro decrease in glutamatergic and cholinergic responses.

All together the data presented here demonstrated that primary cultures from 3xTg-AD mice constitute the first in vitro model for AD with simultaneous overexpression of APP, amyloid-beta and tau. Therefore, this system can provide a valuable approach to study the cellular and molecular basis of the disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded with grants from Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain: AGL2006-08439/ALI, AGL2007-60946/ALI, Ministerio Educación y Ciencia SAF2006-13642. From Xunta de Galicia, Spain: GRC 30/2006, PGIDIT 07MMA006261PR and PGIDT07CSA012261PR, PGDIT 07MMA006261PR, 2008/CP389 (EPITOX, Consellería de Innovación e Industria, programa IN.CI.TE.) and 2009/053 from Conselleria de Educación e Ordenación Universitaria. From EU VIth Frame Program: IP FOOD-CT-2004-06988 (BIOCOP), and CRP 030270-2 (SPIES-DETOX). From EU VIIth Frame Program: 211326-CP (CONffIDENCE); STC-CP2008-1-555612 (Atlantox). E. Alonso is recipient of a predoctoral fellowship from Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Spain.

References

- Billings LM, Oddo S, Green KN, McGaugh JL, LaFerla FM (2005) Intraneuronal Abeta causes the onset of early Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron 45:675–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroni P (1997) Overexpression of growth-associated proteins in the neurons of adult transgenic mice. J Neurosci Methods 71:3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey CA, Gordon MN, Mason JE, Wilson NJ, Diamond DM, Guzowski JF, Morgan D (2004) Amyloid suppresses induction of genes critical for memory consolidation in APP + PS1 transgenic mice. J Neurochem 88:434–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandia L, Montiel C, Garcia AG, López MG (2008) Calcium channels for exocytosis: functional modulation with toxins. CRC Press, Boca Raton [Google Scholar]

- Garcia DA, Bujons J, Vale C, Sunol C (2006) Allosteric positive interaction of thymol with the GABAA receptor in primary cultures of mouse cortical neurons. Neuropharmacology 50:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Llort L, Blazquez G, Canete T, Johansson B, Oddo S, Tobena A, LaFerla FM, Fernandez-Teruel A (2007) Modeling behavioral and neuronal symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease in mice: a role for intraneuronal amyloid. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 31:125–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KN, LaFerla FM (2008) Linking calcium to Abeta and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 59:190–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY (1985) A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260:3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung AY, Koo EH, Haass C, Selkoe DJ (1992) Increased expression of beta-amyloid precursor protein during neuronal differentiation is not accompanied by secretory cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:9439–9443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I (2006) Discoveries of tau, abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau and others of neurofibrillary degeneration: a personal historical perspective. J Alzheimers Dis 9:219–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köpke E, Tung YC, Shaikh S, Alonso AC, Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I (1993) Microtubule-associated protein tau. Abnormal phosphorylation of a non-paired helical filament pool in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 268:24374–24384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFerla FM, Oddo S (2005) Alzheimer’s disease: Abeta, tau and synaptic dysfunction. Trends Mol Med 11:170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Lee C, Rose JE, Reyes A, Ellison G, Jarvik M, Gritz E (1990) Chronic nicotine and withdrawal effects on radial-arm maze performance in rats. Behav Neural Biol 53:269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CA, Cherny RA, Fraser FW, Fuller SJ, Smith MJ, Beyreuther K, Bush AI, Masters CL (1999) Soluble pool of Abeta amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 46:860–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercken M, Vandermeeren M, Lubke U, Six J, Boons J, Van de Voorde A, Martin JJ, Gheuens J (1992) Monoclonal antibodies with selective specificity for Alzheimer Tau are directed against phosphatase-sensitive epitopes. Acta Neuropathol 84:265–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissette DA, Parachikova A, Green KN, Laferla FM (2008) Relevance of transgenic mouse models to human Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 284(10):6033–6037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, LaFerla FM (2006) The role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. J Physiol Paris 99:172–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Kitazawa M, Tseng BP, LaFerla FM (2003a) Amyloid deposition precedes tangle formation in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 24:1063–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM (2003b) Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron 39:409–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Green KN, Liang K, Tran L, Chen Y, Leslie FM, LaFerla FM (2005) Chronic nicotine administration exacerbates tau pathology in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:3046–3051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porzig R, Singer D, Hoffmann R (2007) Epitope mapping of mAbs AT8 and Tau5 directed against hyperphosphorylated regions of the human tau protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 358:644–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith IF, Green KN, LaFerla FM (2005a) Calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease: recent advances gained from genetically modified animals. Cell Calcium 38:427–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith IF, Hitt B, Green KN, Oddo S, LaFerla FM (2005b) Enhanced caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 94:1711–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzmann GE, Caccamo A, LaFerla FM, Parker I (2004) Dysregulated IP3 signaling in cortical neurons of knock-in mice expressing an Alzheimer’s-linked mutation in presenilin1 results in exaggerated Ca2+ signals and altered membrane excitability. J Neurosci 24:508–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzmann GE, Smith I, Caccamo A, Oddo S, Parker I, Laferla F (2007) Enhanced ryanodine-mediated calcium release in mutant PS1-expressing Alzheimer’s mouse models. Ann NY Acad Sci 1097:265–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale C, Damgaard I, Sunol C, Rodriguez-Farre E, Schousboe A (1998) Cytotoxic action of lindane in neocortical GABAergic neurons is primarily mediated by interaction with flunitrazepam-sensitive GABA(A) receptors. J Neurosci Res 52:276–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale C, Vilaro MT, Rodriguez-Farre E, Sunol C (1999) Effects of the conformationally restricted GABA analogues, cis- and trans-4-aminocrotonic acid, on GABA neurotransmission in primary neuronal cultures. J Neurosci Res 57:95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton HS, Dodd PR (2007) Glutamate-glutamine cycling in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int 50:1052–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng-Fischhofer Q, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Illenberger S, Godemann R, Mandelkow E (1998) Sequential phosphorylation of Tau by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and protein kinase A at Thr212 and Ser214 generates the Alzheimer-specific epitope of antibody AT100 and requires a paired-helical-filament-like conformation. Eur J Biochem 252:542–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]