Abstract

Regulated exocytosis of neurotransmitter- and hormone-containing vesicles underpins neuronal and hormonal communication and relies on a well-orchestrated series of molecular interactions. This in part involves the upstream formation of a complex of SNAREs and associated proteins leading to the eventual fusion of the vesicle membrane with the plasma membrane, a process that enables content release. Although the role of lipids in exocytosis is intuitive, it has long been overlooked at least compared to the extensive work on SNAREs. Here, we will present the latest advances in this rapidly developing field revealing that lipids actually play an active role in exocytosis by focusing on cholesterol, 3′-phosphorylated phosphoinositides and phosphatidic acid.

Keywords: Cholesterol, Chromaffin cells, Exocytosis, Phosphatidic acid, Phosphoinositide

Introduction

Exocytosis is the cellular process that allows the fusion of membrane-bound secretory vesicles/granules with the cell plasma membrane and the consequent release of vesicular contents into the extracellular space. It is a fundamental cellular process involved in many physiological functions including cell migration, wound repair, neurotransmission, phagocytosis, protein secretion, and hormone release. Exocytosis occurs constitutively in all eukaryotic cells and is regulated in some cell types like neurons and endocrine cells in response to extrinsic stimuli leading to elevated cytosolic calcium. In most cells specialized for calcium-activated secretion, exocytotic vesicles/granules are present in at least two compartments, a readily releasable pool and a reserve pool which contains the vast majority of vesicles. Vesicles at the plasma membrane are apparently docked in two stages: non-primed (fusion incompetent) and primed (fusion competent).

Details of the molecular machinery underlying some of these steps have been described. For instance, interaction of vesicles with the plasma membrane is mediated by soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) found on secretory vesicles (v-SNAREs) and on the plasma membrane (t-SNAREs). Through coiled-coil interactions, these proteins form a stable complex, which thereby provide the energy necessary to pull membranes into close proximity rendering them fusion competent (Sutton et al. 1998). The mechanism of membrane fusion per se is an aspect that continues to be debated. SNAREs are able to drive liposome fusion in vitro (Weber et al. 1998), but with rather slow kinetics suggesting that additional factors are required for physiological membrane fusion. Lipids, the prime constituents of the fusing membrane, are obvious candidates. The first lipid to be firmly demonstrated to be critical for exocytosis was phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P 2) (for review, see Martin 2001), but more recently fatty acids have been also suggested to play an important function in neurotransmitter release (Darios et al. 2007). Hence, many observations are in agreement with a lipidic component in the fusion reaction. Moreover, the addition of exogenous lipids affects various biological fusion reactions at a stage that lies downstream of the SNARE complex formation (Mayer 2001). It is therefore likely that lipids are essential partners for proteins in the basic fusion machinery via the formation of an intermediate stage, the so-called hemi-fusion intermediate, followed by full membrane merger and formation of a fusion pore (Siegel 1999; Chernomordik and Kozlov 2003). In many regards, the issues now arising are directed toward establishing exactly where in the dynamic exocytotic process a given lipid actually functions. Furthermore, it is important to know if a given component of the exocytotic machinery is acting directly or indirectly (regulatory action) on membrane merging. Over the last decade to address this question, biochemical experiments in which membrane fusion is reconstituted in vitro have been combined with precise methods to quantify specific levels of individual lipid species, together with improved molecular and pharmacological tools to specifically manipulate cellular levels of a given lipid. Here, we will review current evidence concerning the potential roles of three distinct lipids (cholesterol, 3′-phosphorylated phosphoinositols, and phosphatidic acid) required for calcium-regulated exocytosis.

Cholesterol

Cholesterol and sphingolipids cluster into discrete microdomains in cellular membranes. The ability of microdomains to sequester specific proteins and to exclude others makes them ideally suited to spatially organize cellular pathways. Hence, some cholesterol-enriched microdomains seem to concentrate components of the exocytotic/fusion machineries (Furber et al. 2009b, 2010). For instance, a number of recent studies examining the distribution of SNARE proteins in membrane domains in various cell types suggest that SNAREs, like SNAP-25 partially associate with detergent resistant, cholesterol-enriched microdomains (Chamberlain et al. 2001; Lang et al. 2001). Initial evidence for a positive role of cholesterol in calcium-regulated exocytosis comes from experiments in which the amount of cholesterol in membranes has been modified. For instance, cholesterol depletion by methyl-β-cyclodextrin strongly inhibits exocytosis in several cell models (Chamberlain et al. 2001; Belmonte et al. 2005; Churchward et al. 2005). In some cases, however, these effects may be attributed to a proximal effect of cholesterol depletion on calcium-signaling events. When studied in greater detail, it was found that cholesterol depletion directly affects the calcium-evoked release process itself in many cell types, although not always in the same manner. In insulin-secreting cells, cholesterol depletion increases a specific step of the sequential exocytotic reaction (Takahashi et al. 2004). In chromaffin cells, secretagogue-evoked stimulation triggers the formation of GM1/cholesterol-containing lipid microdomains at the level of exocytotic sites. These domains appear to be indispensable for catecholamine secretion and their formation is under the control of annexin A2/S100A10 heterotetramer formation (Chasserot-Golaz et al. 2005). More recently, S100A10 has been shown to be present in VAMP2/syntaxin microdomains at the plasma membrane in resting chromaffin cells using immunogold labeling of plasma membrane sheets combined with spatial point pattern analysis. Upon stimulation, S100A10 in turn recruits annexin A2 near SNARE complexes (Umbrecht-Jenck et al. 2010). This provides evidence that the recruitment of annexin A2 may lead to the formation of lipids microdomains close to SNARE complexes, thereby creating functional exocytotic sites where secretory granules undergo fusion. Altogether, this suggests a functional interplay between annexin A2-mediated lipid microdomains and SNAREs during exocytosis. Nonetheless, there are multiple nonspecific effects associated with the use of cylcodextrins (Zidovetzki and Levitan 2007) and only a targeted analysis can quantitatively establish whether or not cholesterol has direct roles in the exocytotic release step itself (i.e., the fusion mechanism). Such analyses necessitate the isolation of the fusion machinery from the bulk of the exocytotic pathway to enable more directed assessment of critical molecules.

For over a decade, now the stage-specific model of fusion-ready sea urchin egg cortical vesicles has been used to quantitatively dissect the roles of a number of molecules, including cholesterol, in membrane fusion (Churchward and Coorssen 2009; Churchward et al. 2005, 2008); for cholesterol, these quantitative analyses included the use of a number of selective reagents including cyclodextrins, exogenous cholesterol oxidase, polyene antibiotics, and competition with the native positive curvature reagent, lysophosphatidylcholine. Routine quantitative assays of all fusion parameters (as well as docking) is straightforward and of reasonably high throughput. Detailed analyses of fusion parameters (i.e., extent, Ca2+ sensitivity, and kinetics) and the protein and lipid composition of the vesicle membranes have revealed striking similarities with mammalian secretory vesicles. In this assay, cholesterol and specific structurally dissimilar lipids of comparable or greater negative curvature (phosphatidylethanolamine, α-tocopherol, and a diacylglycerol) were shown to be critical players in the fusion pathway, in a manner proportional to the amount of negative curvature each imparts to the contacting monolayers of apposed membranes (Churchward and Coorssen 2009; Churchward et al. 2005, 2008; Rogasevskaia and Coorssen 2006). Notably, lipids of lesser negative curvature, including phosphatidic acid, do not substitute well for cholesterol in these assays indicating that (i) there is a critical intrinsic curvature in terms of lipids that can function in the pathway of membrane merger and (ii) lipids such as phosphatidic acid are more likely to play a modulatory role.

Cholesterol most likely contributes to membrane fusion in two ways: (i) by virtue of its negative curvature, it promotes the formation of high curvature intermediate structures that underlie bilayer merger and (ii) by virtue of its capacity to form microdomains, it ensures the efficiency of fusion (i.e., Ca2+ sensitivity and kinetics) by tightly localizing other critical components that directly and indirectly modulate the release response. These findings are consistent with the majority of studies in neuroendocrine cells and neurons in which depletion of cholesterol results in multiple disruptions to the exocytotic pathway, ultimately resulting in reduced vesicular release. Overall, these studies, together with quantitative analyses of lipid components, indicate that cholesterol and specific other lipids act together to facilitate membrane fusion (Churchward and Coorssen 2009; Churchward et al. 2005, 2008; Rogasevskaia and Coorssen 2006). Thus, for different vesicles in different cell types, the local lipid environment may differentially regulate fusion pore formation, stability, and regulation. Such optimized local lipid compositions, acting in conjunction with proteins, likely serve to reduce energy barriers associated with the molecular reorganizations required to initiate membrane merger and the ensuing (sometimes transient) opening and expansion of the fusion pore. But which proteins are involved and localized to these cholesterol-enriched domains?

There is a rich history of thiol probes being used to study exocytosis, and this is particularly true of the urchin cortical vesicle fusion reaction. In contrast to the consistent inhibition of fusion with a variety of thiol reactive reagents, a particular startling finding has been that the simple alkylating reagent iodoacetamide promotes the Ca2+ sensitivity and kinetics of triggered release (Furber et al. 2009a, b, 2010). The site of action appears to be at or near a Ca2+ sensor, possibly affecting Ca2+ sensitivity and/or the triggering mechanism that initiates the fusion reaction. Adding membrane-intercalating ring structures to iodoacetamide (in the form of fluorescein) results in the complete loss of fusion stimulation. Thus, the inhibitory site that seems more directly involved in the fusion mechanism itself may be at or just within the membrane, whereas the potentiating site is more likely to be somewhat peripheral (perhaps in the cytosolic domain of a protein). Fluorescent analogs that can be used to promote the mechanism and simultaneously label the proteins involved will now be useful to identify the protein and/or lipid targets of these thiol probes. This approach combined with the isolation of cholesterol-enriched regions and 2D gel electrophoresis has resulted in the detection of a limited number of potential protein candidates that are currently being identified using mass spectrometry (Furber et al. 2009b, 2010). This integrated functional-molecular analytical approach, assessing protein and lipid contributions, promises to teach us much more about the fundamental mechanisms underlying the Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion steps of fast, regulated exocytosis. Thus, using the urchin system as a guide to identify fundamental molecular components, and integrating this with the powerful approaches and techniques that are so widely recognized in the study of neuroendocrine cells, we can begin to assign specific functional roles of cholesterol in membrane fusion during regulated exocytosis.

3′-Phosphorylated Phosphoinositides

Phosphoinosites (PI) are a class of phospholipids characterized by an inositol head group that can be phosphorylated on the 3, 4, and 5 positions to generate 7 isoforms that play pleiotropic roles in cell signaling and trafficking. In the last two decades, PI have emerged as key regulators of synaptic function (Osborne et al. 2001). Much of the work carried out on exocytosis have focused on the role played by PtdIns(4,5)P 2 in promoting priming and exocytosis (Eberhard and Holz 1991; Hay and Martin 1992, 1993; Hay et al. 1995; Holz et al. 2000; James et al. 2008). In this section, we highlight novel developments in the field with the discovery of a fine-tuning regulation of exocytosis by 3′-phosphorylated phosphoinositides in neurosecretory cells.

Positive Regulation of Exocytosis by PtdIns3P

There was conflicting evidence as to whether PI3-kinase could be involved in neuroexocytosis. This was mostly based on work carried out using broad-spectrum PI3-kinase inhibitors such as Wortmanin and LY294002. Only high concentrations of these inhibitors were found to have a negative impact on exocytosis (Chasserot-Golaz et al. 1998), leading to the conclusion that the inhibitory effect found could stem from an off-target effect. Interestingly, one isoform of the class II PI3-kinase, PI3K-C2α, is relatively insensitive to pan PI3-kinase inhibitors (Domin et al. 1997). First, PI3K-C2α was found to be enriched in a chromaffin granule preparation isolated from bovine adrenal chromaffin cells and colocalised with neurosecretory granule markers secretogranin II by immunofluorescence (Meunier et al. 2005). Second, expression of PI3K-C2α wild-type potentiated exocytosis is evoked by depolarization in PC12 cells. Most importantly, expression of a kinase-dead mutant completely blocked exocytosis suggesting that PtdIns3P synthesis from PI3K-C2α is necessary for exocytosis to occur. This was further demonstrated by taking advantage of the selective PtdIns3P sequestering ability of the 2xFYVE (Fab-Yotb-Vps27-Eea1 type of zinc finger) domain shown to similarly block exocytosis (Meunier et al. 2005). Experiments carried out on permeabilized chromaffin cells also reveal that perfusion of a functional anti-PI3K-C2α antibody that inhibits the PI3K enzymatic activity, selectively blocked ATP-dependent priming, a necessary step for the acquisition of fusion competence (Meunier et al. 2005). These sets of experiments point to a specific pool of PtdIns3P synthesized by PI3K-C2α, likely to be present on the membrane of a population of neurosecretory vesicles (Fig. 1).

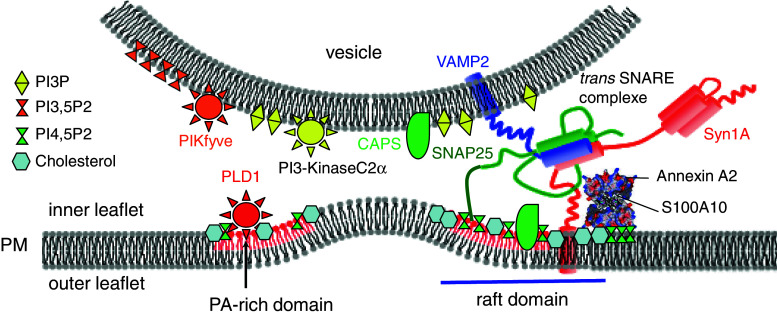

Fig. 1.

Model highlighting the importance of lipids for membrane fusion. PtdIns3P and PtdIns(3,5)P 2 synthesis at the vesicle membrane positively and negatively regulate vesicle fusion competence, respectively. Cholesterol-rich lipid rafts concentrate PA at or near the exocytotic sites. PtdIns(4,5)P 2 accumulation at the same location will act synergistically with PA and cholesterol to recruit constituent of the fusion machinery and to create membrane curvature of the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane prior to merger. The Annexin A2 complex could play an important function in the synthesis or maintenance of these lipid microdomains. PtdIns(4,5)P 2 and PA may also regulate SNARE complex assembly and structure. CAPS potentially mediates the interaction of syntaxin and PtdIns(4,5)P 2. Other potential regulators of lipid turnover are omitted for clarity

Using the same 2xFYVE domain, PtdIns3P was indeed detected on a subpopulation of chromaffin granules (Wen et al. 2008). Most importantly, the PtdIns3P level was found to be up regulated on secretory vesicles during stimulation of exocytosis (Wen et al. 2008). This effect was sensitive to PI3K-C2α knockdown. Furthermore, PI3K-C2α activity appears to be directly up regulated by Ca2+ (Wen et al. 2008). These results provide the first direct evidence that a member of the PI3K family can be regulated by Ca2+ signaling. The molecular basis of this effect is, however, still unclear, but this series of experiments suggested that PtdIns3P production by PI3K-C2α on chromaffin granules could act as a signaling or recruitment factor to prime these vesicles prior to exocytosis through an effectors yet to be determined.

Negative Regulation Exocytosis by PtdIns(3,5)P2

The ability of other 3′-phosphorylated phosphoinositides to control exocytosis in neurosectreory cells has been further investigated. PIKfyve is a PI-kinase responsible for the production of PtdIns(3,5)P 2 (Shisheva et al. 1999). PIKfyve is highly enriched in the adrenal gland, PC12 cells, and brain extracts such as the cortex. In bovine chromaffin cells and PC12 cells, PIKfyve also colocalised with synaptotagmin I, a marker for neurosectory granules. The first functional clue that PIKfyve could be involved in exocytosis came with the use of YM201636 a PIKfyve selective inhibitor (Jefferies et al. 2008). YM201636 markedly potentiated depolarization-induced catecholamine release from bovine chromaffin cells and hGH release from PC12 cells (Osborne et al. 2008). Similar potentiation was found in PC12 cells engineered to knockdown PIKfyve by interference RNA (Osborne et al. 2008). In contrast, expression of PIKfyve wild type inhibited secretion in PC12 cells (Osborne et al. 2008). These experiments clearly pointed to a negative role played by PtdIns(3,5)P 2 in exocytosis. Importantly, the recruitment of PIKfyve was found to be sensitive to a high concentration of Wortmanin suggesting that PIKfyve could be recruited by PtdIns3P on large dense-core vesicle as a result of PI3K-C2α activation by Ca2+ (Fig. 1).

These studies highlight a novel and complex regulation of neuroexocytosis by 3′-phosphorylated phosphoinositide (Wen et al. 2010). PtdIns3P was found to be an essential factor promoting ATP-dependent priming in neurosecretory cells. It is intriguing that the additional phosphorylation on the 5′-position of PtdIns3P is sufficient to confer a completely opposite effect. This reveals a fine-tuning of exocytosis by two related 3′-phosphorylated phosphoinositides that could potentially control the number of vesicles undergoing priming in response to stimulation. At present it is not known whether PtdIns3P-positive secretory granules preferentially undergo exocytosis. It will be critical to find out at which stage of the secretory process this novel pathway is involved. Whether PI3K-C2α and PIKfyve are linked into the same pathway is possible, but needs to be further investigated. Many other questions remain unsolved such as the effectors involved. In view of the importance played by PIKfyve and associated proteins in neuronal function and survival (Chow et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2007), it is important to uncover specific PI effectors. One novel strategy, based on a proteomic approach has recently emerged (Osborne et al. 2007). More work is needed to identify PtdIns3P and PtdIns(3,5)P 2 effectors in exocytosis and neuronal degeneration.

Phosphatidic Acid

Although phosphatidic acid (PA) only occurs in small amounts in mammalian cells, it is a key metabolite in lipid biosynthesis with a very high turnover rate. Besides de novo synthesis through acylation of glycerol 3-phosphate or dihydroxy acetone phosphate, three alternative biosynthetic pathways can generate PA: phosphorylation of diacylglycerol by diacylglycerol-kinase, hydrolysis of phospholipids by phospholipase D (PLD), and acylation of lyso-PA (LPA) by LPA-acyltransferases. The local formation of PA is a recurring theme in intracellular membrane traffic. In particular, PA synthesis resulting from the activities of PLD, diacylglycerol-kinase, and the LPA-acyltransferase, BARS50, has been shown to modulate vesicle transport within the Golgi apparatus (Freyberg et al. 2003). The involvement of PA has also been suggested in regulated exocytosis, but in this case the pathway involved seems to be restricted to PLD-generated PA (Vitale et al. 2001; Zeniou-Meyer et al. 2007; Bader and Vitale 2009).

Preliminary experiments have shown a correlation between PLD activation and secretory activity in HL60 cells (Xie et al. 1991; Stutchfield and Cockcroft 1993). 1-Butanol, an inhibitor of PA accumulation, also strongly affects exocytosis in a number of different cell types (Xie et al. 1991; Stutchfield and Cockcroft 1993; Caumont et al. 1998; Choi et al. 2002). More recently, the development of molecular tools has enabled the identification of PLD1 as a key isoform responsible for PA synthesis during exocytosis (Vitale et al. 2001; Hughes et al. 2004; Waselle et al. 2005). Using an electrophysiological approach, PLD was shown to regulate the number of functional active sites at Aplysia synapses (Humeau et al. 2001). More recently capacitance recordings from chromaffin cells expressing PLD1 siRNA indicated that PLD1 controls the number of fusion competent secretory granules docked at the plasma membrane without affecting earlier recruitment steps (Zeniou-Meyer et al. 2007). Using the molecular probe Spo20p-GFP, PA was observed to accumulate at exocytotic sites (Zeniou-Meyer et al. 2007). The recruitment of Spo20p-GFP at the plasma membrane of stimulated cells was specifically impaired in cells depleted of PLD1, arguing that PLD1 is responsible for the synthesis of PA at the exocytotic site in stimulated neuroendocrine cells.

In addition to recruit and regulate various important proteins, PA is unique among anionic lipids because of its small and highly charged headgroup very close to the glycerol backbone and cone-shape. PA tends to form microdomains through intermolecular hydrogen bonding (Boggs 1987; Demel et al. 1992). A partial reduction in charge (e.g. upon divalent cation interaction) reduces electrostatic repulsion between the PA headgroups and increases attractive hydrogen bonding interactions, which may result in fluid–fluid immiscibility and the formation of microdomains enriched in PA (Garidel et al. 1997). These highly charged microdomains could induce conformational changes in associated proteins, serve as membrane insertion sites, or generate negative membrane curvature. Supporting this latter hypothesis, defects in hormone release caused by reducing PLD1 expression can be reversed by adding a lipid such as lysophosphatidylcholine that favors positive membrane curvature to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. The biophysical properties of PA also imply that it should rapidly disperse within planar membranes. One possible explanation for the accumulation of PA at the exocytotic site is the occurrence of a PA-binding site that prevents PA diffusion. Recently such binding of PA to protein with a highly basic motif has been identified in the plasma membrane-associated SNARE protein syntaxin-1 (Lam et al. 2008). A mutation in the polybasic juxtamembrane region of syntaxin-1, which prevents binding to acid phospholipids such as PA, strongly affected the exocytotic response of chromaffin and PC12 cells, suggesting that PA-binding may be required for the function of syntaxin (Lam et al. 2008). The observations that the secretory defect seen in cells expressing an acidic phospholipid-binding deficient syntaxin-1 could be completely rescued by over-expressing PLD1 is the first evidence supporting the idea that PA is critical for SNARE-mediated fusion events. In agreement, in vitro experiments have revealed that PA present in a t-SNARE containing membrane promoted fusion with a v-SNARE containing membrane (Vicogne et al. 2006), as well as SNARE complex assembly (Mima and Wickner 2009). Furthermore, the X-ray structure of this polybasic region of syntaxin-1 confirms that it is important for SNARE complex assembly and that a lipid such as PA may stabilize its orientation (Stein et al. 2009). Interestingly, cholesterol, another important lipid in membrane organization (see previous section), is also likely to reduce translocation of PA between membrane leaflets. Cholesterol at the granule-docking site adds a further constraint to the curvature properties of PA at the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (Kooijman et al. 2003). The byproduct of PA, DAG also facilitates the negative curvature of the plasma membrane (Kooijman et al. 2003). Thus a local elevation of PA at the granule-docking site may favor the formation of the hemi-fusion intermediate step leading to the fusion pore (Fig. 1).

PA has multiple functions in cells: in signal transduction events such as activation of PI-kinase; in protein recruitment as a lipid binding partner for key proteins; in the production of bioactive lipids such as DAG or LPA; and in the modification of membrane curvature. In fact, it is likely that PA is a critical lipid in any given physiological event through a combination of these functions. The recent identification of potent highly specific PLD inhibitors, together with the characterization of new PA-probes to follow the dynamics of PA in living cells at the sub-second timescale will undoubtedly prove to be valuable to dissect further the function of PA in regulated exocytosis.

Conclusion

The stalk pore model for membrane fusion suggests that the merging of cis contacting monolayers gives rise to a negatively curved lipid structure called a stalk. The structure of this stalk depends on the composition of the cis monolayers (the outer leaflet of the vesicle and the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane). In agreement, it was recently shown that lipids appear to control the ability of SNARE proteins to engage membrane fusion (Melia et al. 2006) and to control SNARE complex assembly (Mima and Wickner 2009). The addition of a cone-shaped lipid such as cholesterol or PA, which have negative intrinsic curvatures, to the cis leaflets of contacting bilayers (Fig. 1), is thus believed to enhance membrane fusion (Chernomordik and Kozlov 2003). The tight organization of cholesterol-rich lipid raft domains and the potential association of SNAREs and fusogenic lipids to these structures might limit these curving forces to the inner leaflet of these domains (Fig. 1). Annexin A2 or a related protein could play an important role in the generation and maintenance of lipid domains. CAPS has also been suggested to play an important role in mediating phospholipid/syntaxin interaction (James et al. 2009). Interestingly, PtdIns(4,5)P 2 has also been suggested to associate with the inner leaflet of lipid raft domains (Hope and Pike 1996). This is especially interesting due to the vital function of PtdIns(4,5)P 2 and cholesterol in regulated exocytosis. Further, PtdIns(4,5)P 2 has been proposed to convert from an inverted cone-shaped structure to a cone-shaped form in the presence of calcium (Zimmerberg and Chernomordik 1999). Hence in addition to the already known positive feedback loop of PtdIns(4,5)P 2 and PA in their respective biosynthetic pathways, a local accumulation of PA and PtdIns(4,5)P 2 may have a synergistic effect on membrane curvature. The overall curvature of these structures is also probably tightly controlled by lipid composition. Today it is clear that lipids at or near exocytotic sites play fundamental roles in the exocytotic process and that they are an intricate part of the exocytotic machinery. The new tools that are emerging will allow dissection of this process in greater detail in the near future. But it appears evident that such studies will also have to take into consideration the cooperative or antagonist action of these different lipids. For instance, we still need to uncover how the various forms of phosphoinositides (as shown here for PtdIns3P and PtdIns(3,5)P 2) participate in the fine regulation of the exocytotic process by controlling vesicle dynamic and availability or how cholesterol and PA together modulate membrane topology. The goal is now to understand the molecular orchestration of these players and the individual tasks each plays in the molecular symphony of membrane fusion.

Acknowledgment

We want to thank the members of our laboratories and the collaborators who contributed to the work presented here. We wish to thank Dr Nancy Grant for critical reading of the manuscript. Work in NV’s group is supported by Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR-09-BLAN-0264-01 grant). JRC acknowledges support of the CIHR, NSERC, and the University of Western Sydney.

Footnotes

A commentary to this article can be found at doi:10.1007/s10571-010-9610-0.

References

- Bader MF, Vitale N (2009) Phospholipase D in calcium-regulated exocytosis: lessons from chromaffin cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1791:936–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte SA, Lopez CI, Roggero CM, De Blas GA, Tomes CN, Mayorga LS (2005) Cholesterol content regulates acrosomal exocytosis by enhancing Rab3A plasma membrane association. Dev Biol 285:393–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggs JM (1987) Lipid intermolecular hydrogen bonding: influence on structural organization and membrane function. Biochim Biophys Acta 906:353–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caumont AS, Galas MC, Vitale N, Aunis D, Bader MF (1998) Regulated exocytosis in chromaffin cells. Translocation of ARF6 stimulates a plasma membrane-associated phospholipase D. J Biol Chem 273:1373–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain LH, Burgoyne RD, Gould GW (2001) SNARE proteins are highly enriched in lipid rafts in PC12 cells: implications for the spatial control of exocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:5619–5624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasserot-Golaz S, Hubert P, Thiersé D, Dirrig S, Vlahos CJ, Aunis D, Bader MF (1998) Possible involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in regulated exocytosis: studies in chromaffin cells with inhibitor LY294002. J Neurochem 70:2347–2356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasserot-Golaz S, Vitale N, Umbrecht-Jenck E, Knight D, Gerke V, Bader MF (2005) Annexin 2 promotes the formation of lipid microdomains required for calcium-regulated exocytosis of dense-core vesicles. Mol Biol Cell 3:1108–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernomordik LV, Kozlov MM (2003) Protein-lipid interplay in fusion and fission of biological membranes. Annu Rev Biochem 72:175–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Kim M, Combs C, Frohman MA, Beaven MA (2002) Phospholipases D1 and D2 regulate different phases of exocytosis in mast cells. J Immunol 168:5682–5689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow CY, Zhang Y, Dowling JJ, Jin N, Adamska M, Shiga K, Szigeti K, Shy ME, Li J, Zhang X, Lupski JR, Weisman LS, Meisler MH (2007) Mutation of FIG 4 causes neurodegeneration in the pale tremor mouse and patients with CMT4J. Nature 448:68–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchward MA, Coorssen JR (2009) Cholesterol, regulated exocytosis and the physiological fusion machine. Biochem J 423:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchward MA, Rogasevskaia T, Hofgen J, Bau J, Coorssen JR (2005) Cholesterol facilitates the native mechanism of Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion. J Cell Sci 118:4833–4848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchward MA, Rogasevskaia T, Brandman DM, Khosravani H, Nava P, Atkinson JK, Coorssen JR (2008) Specific lipids supply critical intrinsic negative curvature—an essential component of native Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion. Biophys J 94:3976–3995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darios F, Connell E, Davletov B (2007) Phospholipases and fatty acid signalling in exocytosis. J Physiol 585:699–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demel RA, Yin CC, Lin BZ, Hauser H (1992) Monolayer characteristics and thermal behaviour of phosphatidic acids. Chem Phys Lipids 60:209–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domin J, Pages F, Volinia S, Rittenhouse SE, Zvelebil MJ, Stein RC, Waterfield MD (1997) Cloning of a human phosphoinositide 3-kinase with a C2 domain that displays reduced sensitivity to the inhibitor wortmannin. Biochem J 326:139–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard DA, Holz RW (1991) Regulation of the formation of inositol phosphates by calcium, guanine nucleotides and ATP in digitonin-permeabilized bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Biochem J 279:447–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyberg Z, Siddhanta A, Shields D (2003) “Slip, sliding away”: phospholipase D and the Golgi apparatus. Trends Cell Biol 13:540–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furber KA, Brandman D, Coorssen JR (2009a) Enhancement of the Ca2+-triggering steps of native membrane fusion via thiol-reactivity. J Chem Biol 2:27–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furber KA, Churchward MA, Rogasevskaia T, Coorssen JR (2009b) Identifying critical components of native Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion: integrating studies of proteins and lipids. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1152:121–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furber KL, Dean KT, Coorssen JR (2010) Dissecting the mechanism of Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion: probing protein function using thiol-reactivity. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 37:208–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garidel P, Johann C, Blume A (1997) Nonideal mixing and phase separation in phosphatidylcholine-phosphatidic acid mixtures as a function of acyl chain length and pH. Biophys J 72:2196–2210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JC, Martin TF (1992) Resolution of regulated secretion into sequential MgATP-dependent and calcium-dependent stages mediated by distinct cytosolic proteins. J Cell Biol 119:139–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JC, Martin TF (1993) Phosphatidylinositol transfer protein required for ATP-dependent priming of Ca2+-activated secretion. Nature 366:572–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JC, Fisette PL, Jenkins GH, Fukami K, Takenawa T, Anderson RA, Martin TF (1995) ATP-dependent inositide phosphorylation required for Ca2+-activated secretion. Nature 374:173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz RW, Hlubek MD, Sorensen SD, Fisher SK, Balla T, Ozaki S, Prestwich GD, Stuenkel EL, Bittner MA (2000) A pleckstrin homology domain specific for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns-4,5-P2) and fused to green fluorescent protein identifies plasma membrane PtdIns-4,5-P2 as being important in exocytosis. J Biol Chem 275:17878–17885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope HR, Pike LJ (1996) Phosphoinositides and phosphoinositide-utilizing enzymes in detergent-insoluble lipid domains. Mol Biol Cell 7:843–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes WE, Elgundi Z, Huang P, Frohman MA, Biden TJ (2004) Phospholipase D1 regulates secretagogue-stimulated insulin release in pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem 279:27534–27541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humeau Y, Vitale N, Chasserot-Golaz S, Dupont JL, Du G, Frohman MA, Bader MF, Poulain B (2001) A role for phospholipase D1 in neurotransmitter release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:15300–15305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, Khodthong C, Kowalchyk JA, Martin TF (2008) Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate regulates SNARE-dependent membrane fusion. J Cell Biol 182:355–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, Kowalchyk JA, Daily N, Petrie M, Martin TF (2009) CAPS drives trans-SNARE complex formation and membrane fusion through syntaxin interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:17308–17313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies HB, Cooke FT, Jat P, Boucheron C, Koizumi T, Hayakawa M, Kaizawa H, Ohishi T, Workman P, Waterfield MD, Parker PJ (2008) A selective PIKfyve inhibitor blocks PtdIns(3,5)P2 production, disrupts endomembrane traffic and retroviral budding. EMBO Rep 9:164–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman EE, Chupin V, de Kruijff B, Burger KN (2003) Modulation of membrane curvature by phosphatidic acid and lysophosphatidic acid. Traffic 4:162–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam AD, Tryoen-Toth P, Tsai B, Vitale N, Stuenkel EL (2008) SNARE-catalyzed fusion events are regulated by syntaxin1a-lipid interactions. Mol Biol Cell 19:485–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T, Bruns D, Wenzel D, Riedel D, Holroyd P, Thiele C, Jahn R (2001) SNAREs are concentrated in cholesterol-dependent clusters that define docking and fusion sites for exocytosis. EMBO J 20:2202–2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TF (2001) PI(4,5)P(2) regulation of surface membrane traffic. Curr Opin Cell Biol 13:493–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A (2001) What drives membrane fusion in eukaryotes? Trends Biochim Sci 26:717–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melia TJ, You D, Tareste DC, Rothman JE (2006) Lipidic antagonists to SNARE-mediated fusion. J Biol Chem 281:29597–29605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier FA, Osborne SL, Hammond GR, Cooke FT, Parker PJ, Domin J, Schiavo G (2005) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase C2alpha is essential for ATP-dependent priming of neurosecretory granule exocytosis. Mol Biol Cell 16:4841–4851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mima J, Wickner W (2009) Complex lipid requirements for SNARE- and SNARE chaperone-dependent membrane fusion. J Biol Chem 284:27114–27122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne SL, Meunier FA, Schiavo G (2001) Phosphoinositides as key regulators of synaptic function. Neuron 32:9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne SL, Wallis TP, Jimenez JL, Gorman JJ, Meunier FA (2007) Identification of secretory granule phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-interacting proteins using an affinity pulldown strategy. Mol Biol Proteomics 6:1158–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne SL, Wen PJ, Boucheron C, Nguyen HN, Hayakawa M, Kaizawa H, Parker PJ, Vitale N, Meunier FA (2008) PIKfyve negatively regulates exocytosis in neurosecretory cells. J Biol Chem 283:2804–2813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogasevskaia T, Coorssen JR (2006) Rafts define the efficiency of native Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion. J Cell Sci 119:2688–2694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisheva A, Sbrissa D, Ikonomov O (1999) Cloning, characterization, and expression of a novel Zn2+-binding FYVE finger-containing phosphoinositide kinase in insulin-sensitive cells. Mol Cell Biol 19:623–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel DP (1999) The modified stalk mechanism of lamellar/inverted phase transitions and its implications for membrane fusion. Biophys J 76:291–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A, Weber G, Wahl MC, Jahn R (2009) Helical extension of the neuronal SNARE complex into the membrane. Nature 460:525–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutchfield J, Cockcroft S (1993) Correlation between secretion and phospholipase D activation in differentiated HL60 cells. Biochem J 293:649–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton RB, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger AT (1998) Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature 395:347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Hatakeyama H, Okado H, Miwa A, Kishimoto T, Kojima T, Abe T, Kasai H (2004) Sequential exocytosis of insulin granules is associated with redistribution of SNAP25. J Cell Biol 165:255–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbrecht-Jenck E, Demais V, Calco V, Bailly Y, Bader MF, Chasserot-Golaz S (2010) S100A10 mediated translocation of annexin A2 to SNARE proteins in adrenergic chromaffin cells undergoing exocytosis. Traffic 11:958–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicogne J, Vollenweider D, Smith JR, Huang P, Frohman MA, Pessin JE (2006) Asymmetric phospholipid distribution drives in vitro reconstituted SNARE-dependent membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:14761–14766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale N, Caumont AS, Chasserot-Golaz S, Du G, Wu S, Sciorra VA, Morris AJ, Frohman MA, Bader MF (2001) Phospholipase D1: a key factor for the exocytotic machinery in neuroendocrine cells. EMBO J 20:2424–2434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waselle L, Gerona R, Vitale N, Martin TFJ, Bader MF, Regazzi R (2005) Role of phosphoinositide signaling in the control of insulin exocytosis. Mol Endocrinol 19:3097–3106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T, Zemelman BV, McNew JA, Westermann B, Gmachl M, Parlati F, Söllner TH, Rothman JE (1998) SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell 92:749–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen PJ, Osborne SL, Morrow IC, Parton RG, Domin J, Meunier FA (2008) Ca2+-regulated pool of phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate produced by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase C2alpha on neurosecretory vesicles. Mol Biol Cell 19:5593–5603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen PJ, Osborne SL, Meunier FA (2010) Dynamic control of neuroexocytosis by phosphoinositides in health and disease. Prog Lipid Res [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xie MS, Jacobs LS, Dubyak GR (1991) Activation of phospholipase D and primary granule secretion by P2-purinergic- and chemotactic peptide-receptor agaonists is induced during granulocyte differenciation of HL-60 cells. J Clin Invest 88:45–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeniou-Meyer M, Zabari N, Ashery U, Chasserot-Golaz S, Haeberle AM, Demais V, Bailly Y, Gottfried I, Nakanishi H, Neiman AM, Du G, Frohman MA, Bader MF, Vitale N (2007) Phospholipase D1 production of phosphatidic acid at the plasma membrane promotes exocytosis of large dense-core granules at a late stage. J Biol Chem 282:21746–21757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zolov SN, Chow CY, Slutsky SG, Richardson SC, Piper RC, Yang B, Nau JJ, Westrick RJ, Morrison SJ, Meisler MH, Weisman LS (2007) Loss of Vac14, a regulator of the signaling lipid phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate, results in neurodegeneration in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:17518–17523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zidovetzki R, Levitan I (2007) Use of cyclodextrins to manipulate plasma membrane cholesterol content: evidence, misconceptions and control strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768:1311–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerberg J, Chernomordik LV (1999) Membrane fusion. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 38:197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]