Abstract

The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-mediated intracellular Ca2+ releases in secretory cells play vital roles in controlling not only the intracellular Ca2+ concentrations but also the Ca2+-dependent exocytotic processes. Of intracellular organelles that release Ca2+ in response to IP3, secretory granules stand out as the most prominent organelle and are responsible for the majority of IP3-dependent Ca2+ releases in the cytoplasm of chromaffin cells. Bovine chromaffin granules were the first granules that demonstrated the IP3-mediated Ca2+ release as well as the presence of the IP3 receptor (IP3R) in granule membranes. Secretory granules contain all three (type 1, 2, and 3) IP3R isoforms, and 58–69% of total cellular IP3R isoforms are expressed in bovine chromaffin granules. Moreover, secretory granules contain large amounts (2–4 mM) of chromogranins and secretogranins; chromogranins A and B, and secretogranin II being the major species. Chromogranins A and B, and secretogranin II are high-capacity, low-affinity Ca2+ binding proteins, binding 30–93 mol of Ca2+/mol of protein with dissociation constants of 1.5–4.0 mM. Due to this high Ca2+ storage properties of chromogranins secretory granules contain ~40 mM Ca2+. Furthermore, chromogranins A and B directly interact with the IP3Rs and modulate the IP3R/Ca2+ channels, i.e., increasing the open probability and the mean open time of the channels 8- to 16-fold and 9- to 42-fold, respectively. Coupled chromogranins change the IP3R/Ca2+ channels to a more ordered, release-ready state, whereby making the IP3R/Ca2+ channels significantly more sensitive to IP3.

Keywords: Chromaffin cells; Secretory granule; Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; Chromogranins; Secretogranins

Introduction

Secretory cells are distinguished from other cells in that their main physiological function in an organism is to produce, store, and secrete a variety of small and large molecules of physiological importance. At the center of physiological functions of secretory cells lie the secretory granules, which have traditionally been thought to merely store and carry the secretory products until they are released in Ca2+-dependent regulatory secretory processes. The first signal in the regulated exocytosis is the sudden increase in the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations, which can result from either release from intracellular Ca2+ stores or influx from outside.

Despite the presence of high concentrations of Ca2+, reaching 15–40 mM (Haigh et al. 1989; Petersen and Tepikin 2008; Winkler and Westhead 1980), in secretory granules of secretory cells, the identity of intracellular Ca2+ source that leads to initiation of exocytotic processes has not been attributed to secretory granules until recently (reviewed in Yoo 2010). The first demonstration of IP3-induced Ca2+ release from secretory granules was done with bovine chromaffin granules (Yoo and Albanesi 1990), and the first evidence for the existence of the IP3R on secretory granule membrane has also been obtained from bovine chromaffin granules (Yoo 1994). Since then the IP3-sensitive Ca2+ store role of secretory granules has been shown with many different secretory cells such as pancreatic β-cells (Xie et al. 2006; Srivastava et al. 1999), acinar cells (Gerasimenko et al. 1996, 2006), airway goblet cells, mast cells (Nguyen et al. 1998; Quesada et al. 2001, 2003), in addition to chromaffin cells (Santodomingo et al. 2008).

In dual measurements of the intragranular Ca2+ as well as the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations in the immediate vicinity of secretory granules using optical sectioning method, it was demonstrated that the IP3-mediated Ca2+ release from secretory granules of airway goblet cells directly control the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations (Nguyen et al. 1998). The IP3-mediated intragranular Ca2+ releases and sequestrations were in exactly 180° out-of-phase with the oscillatory fluctuations of cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations in the immediate vicinity of the granules (Nguyen et al. 1998); the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations rose when the intragranular Ca2+ concentrations decreased, and the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations decreased when the intragranular Ca2+ concentrations rose, clearly demonstrating the control of cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations by secretory granules.

In addition to storing large amounts of Ca2+ inside, the sheer number of secretory granules in secretory cells, often numbering tens of thousands per cell (Burgoyne 1991; Huh et al. 2005a; Nordmann 1984; Plattner et al. 1997; Vitale et al. 1995), overwhelms other subcellular organelles in number as well as in total cell volume. Hence, secretory granules contain by far the highest amounts of cellular calcium, and in the case of bovine chromaffin cells secretory granules occupy ~20% of total cell volume (Burgoyne 1991; Huh et al. 2005a; Plattner et al. 1997) and contain >60% of total cell calcium (Haigh et al. 1989). Such a high Ca2+ storing capacity of secretory granules is due to the presence of large amounts (2–4 mM) of high-capacity Ca2+-storage proteins chromogranins A and B, along with some secretogranins of which secretogranin II being the major one (Helle 2000; Montero-Hadjadje et al. 2008; Taupenot et al. 2003; Winkler and Fischer-Colbrie 1992). Moreover, the IP3R/Ca2+ channels are richly expressed in the membranes of secretory granules: all three isoforms of IP3R are expressed in secretory granules (Srivastava et al. 1999; Yoo et al. 2001) and 58–69% of total cellular IP3R isoforms are represented in secretory granules of bovine chromaffin cells (Huh et al. 2005c). The overall role of secretory granules in IP3-dependent Ca2+ signaling in the cytoplasm of neuroendocrine cells has recently been reviewed (Yoo 2010). Hence, in the present review the specific functions of and the relationship between chromogranins and the IP3Rs in secretory granules will be discussed.

IP3Rs in Secretory Granules

Soon after the discovery of the IP3R in the membranes of bovine chromaffin granules (Yoo 1994), the presence of the IP3R in insulin-containing secretory granules of pancreatic β-cells has also been shown (Blondel et al. 1994). Although the presence of the IP3R in secretory granules of pancreatic β-cells has initially been questioned due to potential cross-reactivity of the IP3R antibody used in the study (Ravazzola et al. 1996) and some studies were not able to detect the presence of the IP3R (Mitchell et al. 2001), it is clear that the IP3Rs are heavily expressed in secretory granules of β-cells (Srivastava et al. 1999; Xie et al. 2006) and other cells. The bulk of the remaining cellular IP3Rs is distributed between the ER and nucleus, and the nuclear IP3Rs are primarily localized in numerous small IP3-sensitive nucleoplasmic Ca2+ store vesicles (Huh et al. 2006; Yoo et al. 2005).

Utilizing the information on the cellular volumes of each subcellular organelle in bovine chromaffin cells (Huh et al. 2005a), it is possible to estimate the relative concentrations and total amounts of each IP3R isoform in subcellular organelles of these cells (Huh et al. 2005c). By taking the respective IP3R concentration in the nucleus as 1, the relative concentrations of the IP3R1 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and secretory granules are shown to be 0.92–1.20 and 3.68–3.77, respectively (Huh et al. 2005c; Huh and Yoo 2003). Likewise, the relative concentrations of the IP3R2 in the ER and secretory granules are shown to be 0.87–1.55 and 3.05–3.48, respectively, while those of the IP3R3 in the ER and secretory granules are estimated to be 0.74–0.94 and 1.88–3.32, respectively (Huh et al. 2005c; Huh and Yoo 2003). These results indicate that the concentrations of the IP3Rs in secretory granules are 2–3-fold higher than those of the ER.

Furthermore, the relative amounts of each IP3R isoform present in each organelle were also estimated. Secretory granules of bovine chromaffin cells are shown to contain ~69% of total cellular IP3R1 while the ER contains ~15% (Huh et al. 2005c). Moreover, secretory granules contain ~64 and ~58% of total cellular IP3R2 and IP3R3, respectively (Huh et al. 2005c), while the ER contains ~20 and ~16% of total cellular IP3R2 and IP3R3, respectively (Huh et al. 2005c). These estimates show that the majority (58–69%) of cellular IP3Rs of bovine chromaffin cells is expressed in secretory granules. Though it is likely that the percentages of cellular IP3Rs expressed in secretory granules of other secretory cells will be lower than those of chromaffin cells given that the number of secretory granules in many secretory cells is lower than that of chromaffin cells, it nevertheless points out that the major portion of cellular IP3Rs is expressed in secretory granules. Considering that the relative concentrations of IP3Rs in secretory granules are 2–3-fold higher than those of the ER, it appears highly likely that secretory granules of secretory cells contain the most IP3Rs in most, if not all, types of secretory cells.

Interestingly, the relative concentrations of each IP3R isoform present in secretory granules that had been induced in otherwise nonsecretory NIH3T3 cells have also been shown to be 3–5-fold higher than those in the nucleus and ER (Huh et al. 2005b). Along with the expression patterns of the IP3Rs in the subcellular organelles of chromaffin cells, these results suggest that chromogranin-expressing secretory granules have intrinsic tendency to accumulate the IP3R/Ca2+ channels in the granule membranes, presumably due to the IP3R-binding properties of chromogranins A and B (Yoo et al. 2000) (see below). Though it is not possible to accurately estimate the relative amounts of each IP3R isoform in the subcellular organelles of the nonsecretory cells in which the formation of secretory granules is induced, owing to lack of information on the cell volume of each organelle, it appeared nonetheless apparent that secretory granules contain more of all three isoforms of IP3R than either the ER or the nucleus (Huh et al. 2005b).

Chromogranins in Secretory Granules

Besides the usual hormones, chromogranins A and B are the major constituents of most secretory granules, followed by significantly less abundant secretogranin II (Helle 2000; Montero-Hadjadje et al. 2008; Taupenot et al. 2003; Winkler and Fischer-Colbrie 1992). Hence these proteins are considered marker proteins of secretory granules, the signature organelle of a variety of secretory cells. Though the granin proteins are expressed in secretory granules of secretory cells, not all secretory granules express the same combinations of the granin proteins (Helle 2000; Montero-Hadjadje et al. 2008; Taupenot et al. 2003; Winkler and Fischer-Colbrie 1992). Bovine chromaffin cells express predominantly chromogranin A, followed by chromogranin B and secretogranin II, whereas humans and rats express more chromogranin B than other granins.

The CGA concentration in bovine chromaffin granules is known to be >1800 μM (Simon and Aunis 1989; Winkler and Westhead 1980) while that in the ER is estimated to be >140 μM, whereas the CGB concentrations in the bovine chromaffin granules and the ER are estimated to be >200 and >120 μM, respectively (Yoo 2010). Unlike the more abundant chromogranins A and B, the third member of the granin protein family secretogranin II is expressed significantly less than chromogranins, and the amounts of SgII present in secretory granules and the ER of bovine chromaffin cells are estimated to be >30 and >10 μM, respectively (Yoo 2010). Taken together, chromaffin granules appear to contain ~6-fold more granin proteins than the ER, containing >2 mM compared to >0.3 mM of the ER. Interestingly, chromogranin B and secretogranin II, but not chromogranin A, are also expressed in the nucleus (Yoo et al. 2002, 2007), localizing in the numerous small IP3-sensitive nucleoplasmic Ca2+ store vesicles (Huh et al. 2006; Yoo et al. 2005).

Chromogranin A binds 32 mol of Ca2+/mol of protein with a dissociation constant (Kd) of 4.0 mM at a near physiological pH 7.5, but this Ca2+-binding capacity increases to 55 mol of Ca2+/mol with a Kd of 2.7 mM at the intragranular pH 5.5 (Yoo and Albanesi 1991). This pattern of more Ca2+ binding at pH 5.5 is also observed in chromogranin B that it binds 50 mol of Ca2+/mol with a Kd of 3.1 mM at pH 7.5, but this increases to 93 mol of Ca2+/mol with a Kd of 1.5 mM at pH 5.5 (Yoo et al. 2001, 2007). Similar pattern is also shown with secretogranin II that it binds 30 mol Ca2+/mol with a Kd of 3.0 mM at pH 7.5 but binds 61 mol Ca2+/mol with a Kd of 2.2 mM at pH 5.5 (Yoo et al. 2007). These results indicate that the granin proteins can bind significantly more Ca2+ at the intragranular pH 5.5 than at a near physiological pH, and this difference in the Ca2+-binding properties of the granin proteins at different pH milieus will apparently affect the Ca2+ storage capacity of these proteins in secretory granules and the ER. Hence, combined with the markedly higher concentrations of chromogranins and secretogranin II in secretory granules, the acidic intragranular pH will greatly facilitate more Ca2+ binding by the granin proteins, thereby resulting in 40 mM Ca2+ in secretory granules (Haigh et al. 1989; Winkler and Westhead 1980) compared to 3 mM Ca2+ in the ER (Meldolesi and Pozzan 1998; Garcia et al. 2006) that maintains a physiological pH.

Moreover, in accordance with the higher Ca2+ storage capacity at the acidic intragranular pH, even a slight increase in the intragranular pH by an alkalinization agent changes the Ca2+ storage property in secretory granules and induces Ca2+ releases from secretory granules (Camacho et al. 2006, 2008; Haynes et al. 2006; Mundorf et al. 1999, 2000), which has been shown to be sufficient to initiate secretory processes in bovine chromaffin cells (Camacho et al. 2008; Mundorf et al. 2000). Under normal conditions, most (>99.9%) of the intragranular Ca2+ stays bound to chromogranins and only a very small amount of granular Ca2+ stays in free state, ranging in 20–100 μM (Bulenda and Gratzl 1985; Gerasimenko et al. 1996; Mitchell et al. 2001; Nguyen et al. 1998; Quesada et al. 2003; Santodomingo et al. 2008). However, an increase in intragranular pH will reduce the degree of calcium binding by the granular chromogranins and increase the concentrations of free Ca2+, a condition conducive for release of more Ca2+ into the cytoplasm.

Interaction of the IP3R by Chromogranins and IP3R/Ca2+ Channel Modulation

As though to complement the presence of other parties in the same organelle, the IP3R/Ca2+ channels and chromogranins work side by side to coordinate the IP3-dependent intracellular Ca2+ storage and control roles of secretory granules. In addition to the high-capacity Ca2+ storage roles of chromogranins, both chromogranins A and B directly interact with the IP3Rs and modulate the IP3R/Ca2+ channels (Thrower et al. 2002, 2003; Yoo et al. 2000; Yoo and Jeon 2000). Yet chromogranins A and B differ significantly in both their IP3R binding strength and the IP3R/Ca2+ channel modulating activity (Figs. 1, 2).

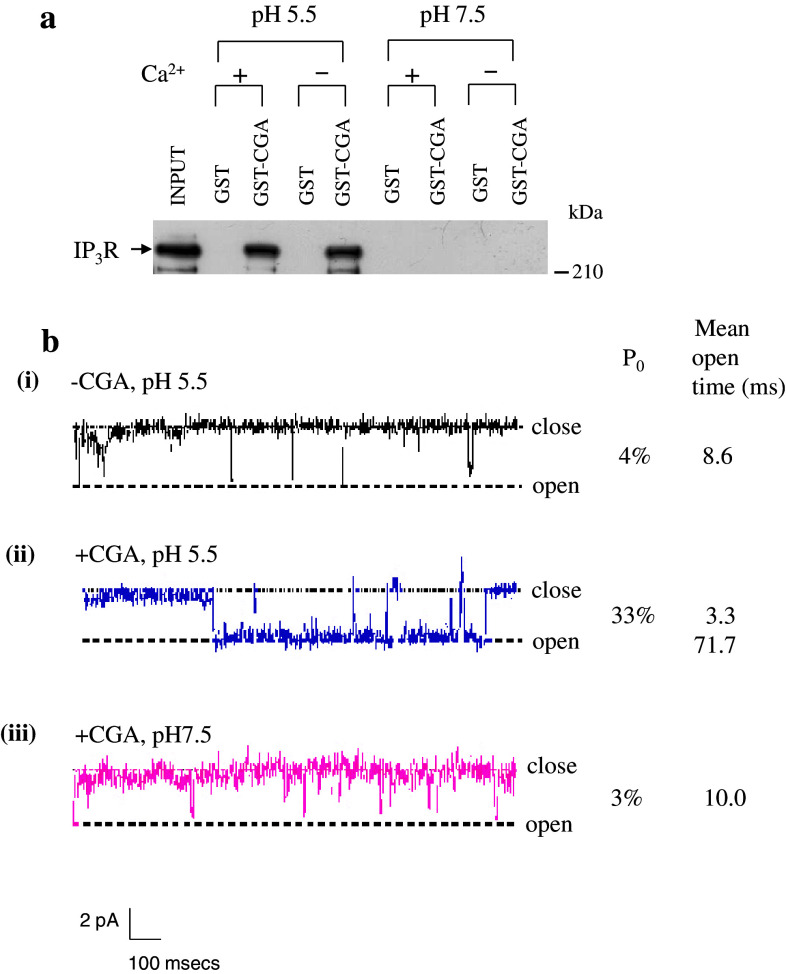

Fig. 1.

pH-dependent interaction of IP3R with chromogranin A and single channel activity of the IP3R/Ca2+ channel. a Purified IP3R (0.5–0.7 μg) was reacted with glutathione S-transferase (GST)–CGA fusion protein in the presence (2 mM) and absence of Ca2+ at pH 5.5 and 7.5, respectively. The bound IP3R was separated on a 7.5% SDS gel and immunoblotted using the IP3R antibody. Notice that CGA dissociated completely at pH 7.5. b Single channel activity of the IP3R incorporated into planar lipid bilayers in the absence and presence of CGA. Trace i, IP3R single channel activated by adding 2 μM IP3 to the cis compartment. Openings are defined as downward deflections from the base line. Trace ii, conditions are same as for trace i, except that CGA (1 μg) was added to the trans compartment at pH 5.5. Trace iii, the pH of the trans compartment was changed to 7.5. The open probability (P 0) and the mean open time of the channel are shown. a and b are modified from (Yoo et al. 2000) and (Thrower et al. 2002), respectively

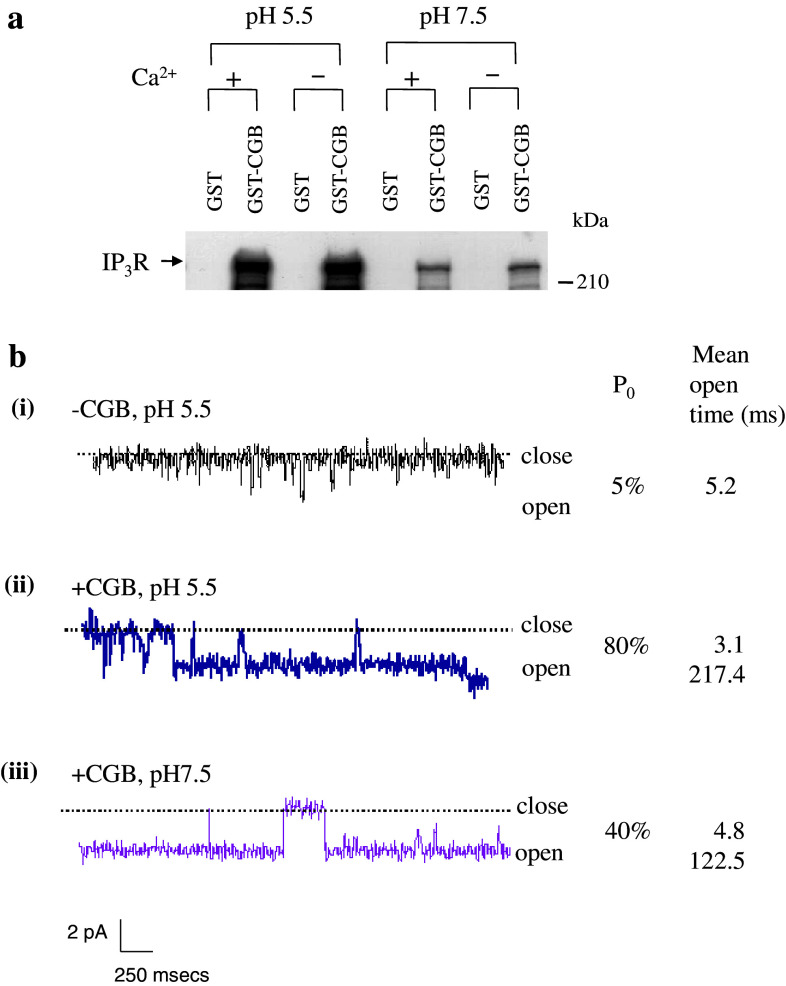

Fig. 2.

pH-dependent interaction of IP3R with chromogranin B and single channel activity of the IP3R/Ca2+ channel. a Purified IP3R (0.5–0.7 μg) was reacted with glutathione S-transferase (GST)–CGB fusion protein in the presence (2 mM) and absence of Ca2+ at pH 5.5 and 7.5, respectively. The bound IP3R was separated on a 7.5% SDS gel and immunoblotted using the IP3R antibody. Notice that some CGB still remained bound at pH 7.5. b Single channel activity of the IP3R incorporated into planar lipid bilayers in the absence and presence of CGB. Trace i, IP3R single channel activated by adding 2 μM IP3 to the cis compartment. Openings are defined as downward deflections from the base line. Trace ii, conditions are same as for trace i, except that CGB (1 μg) was added to the trans compartment at pH 5.5. Trace iii, the pH of the trans compartment was changed to 7.5. The open probability (P 0) and the mean open time of the channel are shown. a and b are modified from (Yoo et al. 2000) and (Thrower et al. 2003), respectively

Chromogranin A interacts with the IP3R only at pH 5.5, but dissociates completely from the IP3R at pH 7.5 (Fig. 1a), whereas chromogranin B interacts with the IP3R at both pH 5.5 and 7.5 (Fig. 2a), although the interaction at pH 7.5 is significantly weaker than at pH 5.5. This means that only CGB will bind the IP3Rs in the ER while both CGA and CGB bind the IP3Rs in secretory granules. Underscoring the physiological significance of the CGB interaction with the IP3Rs at pH 7.5, the CGB–IP3R coupling in the ER has indeed been shown to play essential roles in controlling the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations (Choe et al. 2004). Since the interaction of chromogranins to the IP3R changes the conformation of the IP3R/Ca2+ channel that it becomes a more ordered structure better suited for Ca2+ release in response to IP3 (Thrower et al. 2002, 2003; Yoo et al. 2000; Yoo and Jeon 2000), coupling of chromogranins to the IP3R/Ca2+ channel greatly increases the channel open probability and the mean open time.

The modulatory role of chromogranins on the IP3R/Ca2+ channels was first demonstrated in Ca2+ flux studies using CGA-encapsulated liposomes (Yoo and Jeon 2000). The IP3R/Ca2+ channels that are incorporated in the liposome opened and released intraliposomal Ca2+ in response to IP3, and the amount of Ca2+ released through the IP3R/Ca2+ channel was shown to be far greater in the presence of coupled chromogranins than in the absence (Thrower et al. 2003; Yoo and Jeon 2000). Further, in planar bilayer single channel recording studies the IP3R/Ca2+ channel was shown to have an open probability of 4% and a mean open time of 8.6 ms (Thrower et al. 2002) (Fig. 1b). But when chromogranin A was coupled with the IP3R/Ca2+ channel at pH 5.5, the open probability increased to 33%, a 8.2-fold increase, and the mean open time of the channel increased to 71.7 ms, a 8.3-fold increase (Thrower et al. 2002). However, when the pH was changed to 7.5, the IP3R/Ca2+ channel-activating effect of CGA virtually disappeared and the channel open probability and the mean open time returned to 3% and 10.0 ms, respectively (Fig. 1b), due to complete dissociation of CGA from the IP3R (Fig. 1a).

The IP3R/Ca2+ channel-activating effect of CGB is more pronounced than that of CGA: when CGB was coupled to the IP3R/Ca2+ channel at pH 5.5, the channel open probability increased from 5 to 80%, a 16-fold increase, and the mean open time increased from 5.2 to 217.4 ms, a 42-fold increase (Thrower et al. 2003) (Fig. 2b). But in contrast to CGA that dissociates completely from the IP3Rs at pH 7.5, CGB remains coupled at pH 7.5, albeit to a reduced degree (Yoo et al. 2000) (Fig. 2a). As though to reflect the weakened interaction at pH 7.5, the channel-activating effect of CGB at pH 7.5 was approximately half of that shown at pH 5.5, increasing the channel open probability 8-fold and the mean open time 24-fold (Thrower et al. 2003) (Fig. 2b). Yet the channel-activating effect of CGB at pH 7.5 was still greater than that shown with CGA at pH 5.5 (Thrower et al. 2002, 2003). The prominent role of CGB and the IP3R/Ca2+ channels is also manifested in neurons of hippocampus (Jacob et al. 2005; Nicolay et al. 2007) and in the neurites of neuronally differentiated PC12 cells (Johenning et al. 2002) that CGB and the IP3Rs are shown to play key roles in controlling the IP3-dependent Ca2+ concentrations in these cells.

Conclusion

The presence of chromogranins appears to be critical in the IP3-dependent intracellular Ca2+ control in secretory cells. Considering that the main function of secretory cells is to store and release a variety of bioactive molecules in response to subtle changes in cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations, under no other molecular arrangements in secretory granules is the coupling between the major intracellular Ca2+ channels in the form of the IP3R/Ca2+ channel and the proteins that double as the Ca2+ storage and the Ca2+ channel modulating proteins expected to control more effectively the IP3-dependent intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. Hence, consistent with the substantially higher concentrations of chromogranins in secretory granules than in the ER and the greater IP3R/Ca2+ channel-activating effects of chromogranins at pH 5.5 than at the pH of the ER, the secretory granule IP3R/Ca2+ channels are at least 6–7-fold more sensitive to IP3 than those of the ER (Huh et al. 2007; Yoo 2010).

The crucial roles of chromogranins and the IP3R/Ca2+ channels uncovered in chromaffin cells are also presumed to apply to other secretory cells. Secretory granules of pancreatic β-cells contain not only chromogranins (Giordano et al. 2008; Hutton 1989; Winkler and Fischer-Colbrie 1992) but also all the IP3R isoforms, and the IP3-induced Ca2+ release from the granules has been demonstrated to initiate insulin secretion (Srivastava et al. 1999; Xie et al. 2006). In addition, chromogranin B has recently been shown to be expressed in cardiomyocytes that are not considered traditional secretory cells, and was identified as a key regulator of the IP3-dependent Ca2+ release in cardiomyocytes (Heidrich et al. 2008), which has a strong implication in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. The significance of chromogranin–IP3R coupling is further confirmed in induced secretory granules, which result from transfected chromogranins in nonsecretory cells (Beuret et al. 2004; Huh et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2001), that the IP3Rs are cotargeted with chromogranins to the secretory granule membranes (Huh et al. 2005b). Taken together, these results suggest that the physiological partnership between chromogranins and the IP3R/Ca2+ channels in the Ca2+ homeostasis goes beyond neuroendocrine cells to include other non-traditional secretory cells, such as cardiomyocytes (Heidrich et al. 2008) and astrocytes (Hur et al. 2010).

Acknowledgment

The present work was supported in part by the CRI Program and BK21 Program (YSH) of the Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

A commentry to this article can be found at doi:10.1007/s10571-010-9552-6.

References

- Beuret N, Stettler H, Renold A, Rutishauser J, Spiess M (2004) Expression of regulated secretory proteins is sufficient to generate granule-like structures in constitutively secreting cells. J Biol Chem 279:20242–20249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondel O, Moody MM, Depaoli AM, Sharp AH, Ross CA, Swift H, Bell GI (1994) Localization of inositol trisphosphate receptor subtype 3 to insulin and somatostatin secretory granules and regulation of expression in islets and insulinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:7777–7781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulenda D, Gratzl M (1985) Matrix free Ca2+ in isolated chromaffin vesicles. Biochemistry 24:7760–7765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD (1991) Control of exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1071:174–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho M, Machado JD, Montesinos MS, Criado M, Borges R (2006) Intragranular pH rapidly modulates exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurochem 96:324–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho M, Machado JD, Alvarez J, Borges R (2008) Intravesicular calcium release mediates the motion and exocytosis of secretory organelles: a study with adrenal chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem 283:22383–22389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe CU, Harrison KD, Grant W, Ehrlich BE (2004) Functional coupling of chromogranin with the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor shapes calcium signaling. J Biol Chem 279:35551–35556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AG, Garcia-De-Diego AM, Gandia L, Borges R, Garcia-Sancho J (2006) Calcium signaling and exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. Physiol Rev 86:1093–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimenko OV, Gerasimenko JV, Belan PV, Petersen OH (1996) Inositol trisphosphate and cyclic ADP-ribose-mediated release of Ca2+ from single isolated pancreatic zymogen granules. Cell 84:473–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimenko JV, Sherwood M, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH, Gerasimenko OV (2006) NAADP, cADPR and IP3 all release Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum and an acidic store in the secretory granule area. J Cell Sci 119:226–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano T, Brigatti C, Podini P, Bonifacio E, Meldolesi J, Malosio ML (2008) Beta cell chromogranin B is partially segregated in distinct granules and can be released separately from insulin in response to stimulation. Diabetologia 51:997–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh JR, Parris R, Phillips JH (1989) Free concentrations of sodium, potassium and calcium in chromaffin granules. Biochem J 259:485–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes CL, Buhler LA, Wightman RM (2006) Vesicular Ca(2+)-induced secretion promoted by intracellular pH-gradient disruption. Biophys Chem 123:20–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidrich FM, Zhang K, Estrada M, Huang Y, Giordano FJ, Ehrlich BE (2008) Chromogranin B regulates calcium signaling, nuclear factor {kappa}B activity, and brain natriuretic peptide production in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 102:1230–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helle KB (2000) The chromogranins. Historical perspectives. Adv Exp Med Biol 482:3–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh YH, Yoo SH (2003) Presence of the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor isoforms in the nucleoplasm. FEBS Lett 555:411–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh YH, Jeon SH, Yoo SH (2003) Chromogranin B-induced secretory granule biogenesis: comparison with the similar role of chromogranin A. J Biol Chem 278:40581–40589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh YH, Bahk SJ, Ghee JY, Yoo SH (2005a) Subcellular distribution of chromogranins A and B in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. FEBS Lett 579:5145–5151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh YH, Jeon SH, Yoo JA, Park SY, Yoo SH (2005b) Effects of chromogranin expression on inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced intracellular Ca2+ mobilization. Biochemistry 44:6122–6132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh YH, Yoo JA, Bahk SJ, Yoo SH (2005c) Distribution profile of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor isoforms in adrenal chromaffin cells. FEBS Lett 579:2597–2603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh YH, Huh SK, Chu SY, Kweon HS, Yoo SH (2006) Presence of a putative vesicular inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive nucleoplasmic Ca2+ store. Biochemistry 45:1362–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh YH, Kim KD, Yoo SH (2007) Comparison of and chromogranin effect on inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate sensitivity of cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor/Ca2+ channels. Biochemistry 46:14032–14043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur YS, Kim KD, Paek SH, Yoo SH (2010) Evidence for the existence of secretory granule (dense-core vesicle)-based inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Ca2+ signaling system in astrocytes. PLoS One 5:e11973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton JC (1989) The insulin secretory granule. Diabetologia 32:271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob SN, Choe CU, Uhlen P, DeGray B, Yeckel MF, Ehrlich BE (2005) Signaling microdomains regulate inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated intracellular calcium transients in cultured neurons. J Neurosci 25:2853–2864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johenning FW, Zochowski M, Conway SJ, Holmes AB, Koulen P, Ehrlich BE (2002) Distinct intracellular calcium transients in neurites and somata integrate neuronal signals. J Neurosci 22:5344–5353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, Tao-Cheng JH, Eiden LE, Loh YP (2001) Chromogranin A, an “on/off” switch controlling dense-core secretory granule biogenesis. Cell 106:499–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldolesi J, Pozzan T (1998) The endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store: a view from the lumen. Trends Biochem Sci 23:10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Pinton P, Varadi A, Tacchetti C, Ainscow EK, Pozzan T, Rizzuto R, Rutter GA (2001) Dense core secretory vesicles revealed as a dynamic Ca2+ store in neuroendocrine cells with a vesicle-associated membrane protein aequorin chimaera. J Cell Biol 155:41–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Hadjadje M, Vaingankar S, Elias S, Tostivint H, Mahata SK, Anouar Y (2008) Chromogranins A and B and secretogranin II: evolutionary and functional aspects. Acta Physiol 192:309–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundorf ML, Hochstetler SE, Wightman RM (1999) Amine weak bases disrupt vesicular storage and promote exocytosis in chromaffin cells. J Neurochem 73:2397–2405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundorf ML, Troyer KP, Hochstetler SE, Near JA, Wightman RM (2000) Vesicular Ca2+ participates in the catalysis of exocytosis. J Biol Chem 275:9136–9142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T, Chin WC, Verdugo P (1998) Role of Ca2+/K+ ion exchange in intracellular storage and release of Ca2+. Nature 395:908–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolay NH, Hertle D, Boehmerle W, Heidrich FM, Yeckel M, Ehrlich BE (2007) Inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate receptor and chromogranin B are concentrated in different regions of the hippocampus. J Neurosci Res 85:2026–2036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann JJ (1984) Combined stereological and biochemical analysis of storage and release of catecholamines in the adrenal medulla of the rat. J Neurochem 42:434–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen OH, Tepikin AV (2008) Polarized calcium signaling in exocrine gland cells. Annu Rev Physiol 70:273–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plattner H, Artalejo AR, Neher E (1997) Ultrastructural organization of bovine chromaffin cell cortex-analysis by cryofixation and morphometry of aspects pertinent to exocytosis. J Cell Biol 139:1709–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada I, Chin WC, Steed J, Campos-Bedolla P, Verdugo P (2001) Mouse mast cell secretory granules can function as intracellular ionic oscillators. Biophys J 80:2133–2139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada I, Chin WC, Verdugo P (2003) ATP-independent luminal oscillations and release of Ca2+ and H+ from mast cell secretory granules: implications for signal transduction. Biophys J 85:963–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravazzola M, Halban PA, Orci L (1996) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor subtype 3 in pancreatic islet cell secretory granules revisited. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:2745–2748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santodomingo J, Vay L, Camacho M, Hernandez-SanMiguel E, Fonteriz RI, Lobaton CD, Montero M, Moreno A, Alvarez J (2008) Calcium dynamics in bovine adrenal medulla chromaffin cell secretory granules. Eur J Neurosci 28:1265–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JP, Aunis D (1989) Biochemistry of the chromogranin A protein family. Biochem J 262:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava M, Atwater I, Glasman M, Leighton X, Goping G, Caohuy H, Miller G, Pichel J, Westphal H, Mears D, Rojas E, Pollard HB (1999) Defects in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor expression, Ca2+ signaling, and insulin secretion in the anx7(±) knockout mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:13783–13788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taupenot L, Harper KL, O’Connor DT (2003) The chromogranin–secretogranin family. N Engl J Med 348:1134–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrower EC, Park HY, So SH, Yoo SH, Ehrlich BE (2002) Activation of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor by the calcium storage protein chromogranin A. J Biol Chem 277:15801–15806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrower EC, Choe CU, So SH, Jeon SH, Ehrlich BE, Yoo SH (2003) A functional interaction between chromogranin B and the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor/Ca2+ channel. J Biol Chem 278:49699–49706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale ML, Seward EP, Trifaro JM (1995) Chromaffin cell cortical actin network dynamics control the size of the release-ready vesicle pool and the initial rate of exocytosis. Neuron 14:353–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler H, Fischer-Colbrie R (1992) The chromogranins A and B: the first 25 years and future perspectives. Neuroscience 49:497–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler H, Westhead E (1980) The molecular organization of adrenal chromaffin granules. Neuroscience 5:1803–1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Zhang M, Zhou W, Wu Z, Ding J, Chen L, Xu T (2006) Extracellular ATP stimulates exocytosis via localized Ca release from acidic stores in rat pancreatic beta cells. Traffic 7:429–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH (1994) pH-dependent interaction of chromogranin A with integral membrane proteins of secretory vesicle including 260-kDa protein reactive to inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor antibody. J Biol Chem 269:12001–12006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH (2010) Secretory granules in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Ca2+ signaling in the cytoplasm of neuroendocrine cells. FASEB J 24:653–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Albanesi JP (1990) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-triggered Ca2+ release from bovine adrenal medullary secretory vesicles. J Biol Chem 265:13446–13448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Albanesi JP (1991) High capacity, low affinity Ca2+ binding of chromogranin A. Relationship between the pH-induced conformational change and Ca2+ binding property. J Biol Chem 266:7740–7745 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Jeon CJ (2000) Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor/Ca2+ channel modulatory role of chromogranin A, a Ca2+ storage protein of secretory granules. J Biol Chem 275:15067–15073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, So SH, Kweon HS, Lee JS, Kang MK, Jeon CJ (2000) Coupling of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and chromogranins A and B in secretory granules. J Biol Chem 275:12553–12559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Oh YS, Kang MK, Huh YH, So SH, Park HS, Park HY (2001) Localization of three types of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor/Ca2+ channel in the secretory granules and coupling with the Ca2+ storage proteins chromogranins A and B. J Biol Chem 276:45806–45812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, You SH, Kang MK, Huh YH, Lee CS, Shim CS (2002) Localization of the secretory granule marker protein chromogranin B in the nucleus. Potential role in transcription control. J Biol Chem 277:16011–16021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Nam SW, Huh SK, Park SY, Huh YH (2005) Presence of a nucleoplasmic complex composed of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor/Ca2+ channel, chromogranin B, and phospholipids. Biochemistry 44:9246–9254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Chu SY, Kim KD, Huh YH (2007) Presence of secretogranin II and high-capacity, low-affinity Ca2+ storage role in nucleoplasmic Ca2+ store vesicles. Biochemistry 46:14663–14671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]