Abstract

Catecholamines are among first compounds released during stress, and they regulate many functions of the organism, including immune system, via adrenergic receptors (ARs). Spleen, as an immune organ with high number of macrophages, possesses various ARs, from which β2-ARs are considered to be the most important for the modulation of immune functions. Nevertheless, little is known about the regulation and involvement of ARs in the splenic function by stress. Therefore, the aim of this work was to measure the gene expression of ARs and several cytokines in the spleen of rats exposed to a single and repeated (14×) immobilization stress (IMO). We have found a significant increase in β2-AR mRNA after a single IMO, but a significant decrease in β2-AR mRNA and protein level after repeated (14×) IMO. The most prominent decrease was detected in the gene expression of the α2A- and α2C-AR after repeated IMO. However, changes in mRNA were translated into protein levels only for the α2C-subtype. Other types of ARs remained unchanged during the stress situation. Since we proposed that these ARs might affect production of cytokines, we measured gene expression of pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-18) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10 and TGF-β1) cytokines. We detected changes only in IL-6 and IL-10 mRNA levels. While IL-6 mRNA was increased, IL-10 mRNA dropped after repeated IMO. According to these results we suggest that changes of β2- and α2C-ARs participate in IL-6-mediated processes in the spleen, especially during chronic stress situations.

Keywords: Stress, Immobilization, Spleen, Adrenoceptors, Gene expression, Cytokines

Introduction

Physiological responses induced by stress involve activation of the sympathoadrenal system. Catecholamines (CAs)—norepinephrine (NE) and epinephrine (EPI)—are among the first compounds released during stress. Spleen is an organ with high number of macrophages, which are involved in immune response. Spleen also possesses a rich sympathetic innervation and vascular supply. Besides circulating CAs and CAs released from sympathetic nerve terminals, rat spleen contains also machinery to produce CAs de novo (Kubovcakova et al. 2001; Jelokova et al. 2002). Nevertheless, function of the endogenously produced CAs is not fully understood yet. There is an evidence that CAs are important regulators of many functions in the organism, including immune functions of spleen (Meltzer et al. 2004; Yin et al. 2006; Cao et al. 2007). CAs mediate their effects through adrenergic receptors (ARs). In the regulation of immune functions, the most important ARs are β-ARs, especially β2-ARs (Kohm and Sanders 2001). Because β2-ARs are localized on the surface of almost all immune cell types, they can regulate physiologically different immune functions like regulation of cytokine production, adhesion, chemotaxis of immune cells and many others (Kin and Sanders 2006). However, β2-AR-mediated functions may differ according to different conditions and different cell types (Kohm and Sanders 2001). On the other hand, only limited data exist concerning the function of other β-ARs in the spleen. Emeny et al. (2007) showed that splenic β1-AR reduced a defense against Listeria monocytogenes, and that β1-AR knockout (−/−) mice had increased cell-mediated immunity. Administration of β3-AR agonist increased the number but not the proliferation of CD4+ lymphocytes in the spleen (Borger et al. 1998; Lamas et al. 2003). However, Curtin et al. (2009) demonstrated involvement of β-ARs in gene expression of IL-10 and IL-19 in the rat spleen during psychosocial stress. Among α1-ARs subtypes, the α1B-AR and α1D-AR mRNA were found in the rat spleen, with prevalence of α1B-subtype (Rokosh et al. 1994). This type was shown to play a role in smooth muscle contraction of splenic capsule (Eltze 1996). Function of the α1D-AR in spleen is not known yet. The α1A-AR was detected only in human spleen (Faure et al. 1995; Kavelaars 2002) and all three α1-AR subtypes on human peripheral lymphocytes (Ricci et al. 1999; Tayebati et al. 2000). It can be speculated whether the α1-AR expression on lymphocytes appears also in healthy individuals or only under pathological circumstances (Elenkov et al. 2000). Pharmacological studies and expression profiles detected also α2A-, α2B- as well as α2C-subtypes in the rat spleen (Schauenstein et al. 2000; Elenkov and Vizi 1991). The α2-ARs were determined also on rat peripheral lymphocytes and lymphocytes isolated from lymphoid organs (Felsner et al. 1995; Stevenson et al. 2001; Bao et al. 2007), macrophages (Shen et al. 1994; Flierl et al. 2007) and platelets (Müller et al. 1995). It is known that rat spleen is one of the tissues containing a high number of α2C-subtype (Hieble 2000). The available data show involvement of α2-ARs in immune cell functions (Maes et al. 2000; Flierl et al. 2007; Elenkov 2008) as well as in the regulation of CA release via autoregulatory loop, mainly through pre-synaptically localized α2A- and α2C-AR subtypes (Philipp et al. 2002; Elenkov and Vizi 1991). Straub et al. (1997) described involvement of α1- and α2-ARs in splenic IL-6 secretion. These data suggest an importance of specific adrenergic receptor subtypes during different conditions on different immune cells and in different environment represented by immune organs and circulation. However, any systematic study on the influence of stress on the AR’s expression in the spleen has not been conducted so far. Therefore, the aim of our study was to measure gene expression and protein level of α- and β-adrenergic receptors in the spleen of rats under normal conditions and after acute and repeated stress exposure. We also tried to correlate expected changes in ARs with changes in gene expression of several cytokines.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–300 g, Charles River, Suzfeld, Germany) were used in our experiments. Animals were housed 3–4 per cage in a controlled environment (22 ± 2°C, 12 h light–dark cycle, lights on at 6 AM). In the process of a single immobilization, rats were immobilized once for 2 h and decapitated immediately after termination of the stress stimulus, as originally described (Kvetnansky and Mikulaj 1970). Repeated immobilization (IMO) stress was achieved by immobilizing rats for 14 consecutive days for 2 h daily, with subsequent decapitation immediately after the last IMO (Kvetnansky and Mikulaj 1970). In order to check the effect of the last immobilization, one group of rats (called the ‘adapted control group’) was immobilized 13 times for 2 h daily and decapitated 24 h after the last immobilization. Decapitation after 1 day of rest (“adapted control”) is a well-established stress procedure to investigate if changes induced by repeated immobilization (IMO) are really a consequence of adaptation to repeated stress or only a result of a last IMO (Kvetnansky and Mikulaj 1970).

Since a similar response was observed in the spleen after 14×IMO as well as after 7×IMO (unpublished data), we performed another experiment to verify if changes observed after repeated IMO are transient and reversible. Therefore, rats were immobilized for seven consecutive days for 2 h daily with subsequent decapitation 1 day (24 h, similar as in previous experiment) and 7 days of rest after the last IMO. From our previous experiments on other tissues we know that the interval 7 days of rest is long enough to “recover” from IMO (unpublished data). Control-unstressed rats were killed immediately after removal from their home cages in both experiments (14×IMO and 7×IMO). The Ethics Committee of the Institute of Experimental Endocrinology (Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava, Slovakia) approved all experimental procedures with animals used in this study in protocol no. RO-2804/07-221/3. After decapitation spleens were rapidly extirpated, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C for further analysis.

RNA Isolation and Relative Quantification of mRNA Levels by Reverse Transcription with Subsequent Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from frozen spleen by TRI Reagent (MRC Ltd., Cincinnati, OH, USA). The purity and integrity of isolated RNAs was checked on GeneQuant Pro spectrophotometer (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Reverse transcription was performed using 1.5 μg of total RNA and Ready-To-Go You-Prime First-Strand Beads (Amersham Biosciences) with pd(N6) primer (Amersham Biosciences) according to manufacturer’s protocol. PCR for specific ARs and cytokines was carried out as described previously (Myslivecek et al. 2006). Primers and annealing temperatures used are described in Table 1. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA was used as a housekeeper gene control for evaluation of PCR. Products were analyzed on 2% agarose gels. The intensity of individual bands was evaluated by analysis system STS 6220I (Ultra-Lum, Inc.) and PCBASE 2.08e software (Raytest, Inc., Dusseldorf, Germany).

Table 1.

Primers used to assess adrenergic receptor subtypes mRNA expression

| Gene | Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence | Annealing °C/time (s) | Size (bp) | Number of cycles | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β1-AR | Forward | 5′-GCCGATCTGGTCATGGGA-3′ | 65/60 | 326 | 32 | Myslivecek et al. (2006) |

| Reverse | 5′-GTTGTAGCAGCGGCGCG-3′ | |||||

| β2-AR | Forward | 5′-ACCTCCTTCTTGCCTATCCA-3′ | 65/60 | 540 | 32 | Myslivecek et al. (2006) |

| Reverse | 5′-TAGGTTTTCGAAGAAGACCG-3′ | |||||

| β3-AR | Forward | 5′-GCAACCTGCTGGTAATCACA-3′ | 60/60 | 418 | 36 | Myslivecek et al. (2006) |

| Reverse | 5′-GGATTGGAGTGACACTCTTG-3′ | |||||

| α1A-AR | Forward | 5′-CGAGTCTACGTAGTAGCC-3′ | 60/60 | 203 | 38 | Salomonsson et al. (2001) |

| Reverse | 5′-GTCTTGGCAGCTTTCTTC-3′ | |||||

| α1B-AR | Forward | 5′-GTCATCTCCATCGGGCCTCTCCT-3′ | 62/30 | 492 | 30 | Zhang et al. (2002) |

| Reverse | 5′-GTAGCCCAGCCAGAACACCACCTT-3′ | |||||

| α1D-AR | Forward | 5′-CGTGTGCTCCTTCTACCTACCC-3′ | 68/60 | 284 | 30 | Aubert et al. (2001) |

| Reverse | 5′-CGACGATGGCCAACGTCTTGG-3′ | |||||

| α2A-AR | Forward | 5′-GCGCCCCAGAACCTCTTCCTGGTG-3′ | 64/60 | 312 | 35 | Aubert et al. (2001) |

| Reverse | 5′-GAGTGGCGGGAAAAGGATGACGGC-3′ | |||||

| α2B-AR | Forward | 5′-AAACGCAGCCACTGCAGAGGTCTC-3′ | 60/60 | 456 | 38 | Aubert et al. (2001) |

| Reverse | 5′-ACTGGCAACTCCCACATTCTTGCC-3′ | |||||

| α2C-AR | Forward | 5′-CTGGCAGCCGTGGTGGGTTTCCTC-3′ | 64/60 | 426 | 36 | Hillman et al. (2005) |

| Reverse | 5′-GTCGGGCCGGCGGTAGAAAGAGAC-3′ | |||||

| GAPDH | Forward | 5′-AGATCCACAACGGATACATT-3′ | 60/60 | 309 | 30 | Terada et al. (1993) |

| Reverse | 5′-TCCCTCAAGATTGTCAGCAA-3′ | |||||

| TNF-α | Forward | 5′-CCAGACCCTCACACTCAGATCA-3′ | 62/45 | 278 | 30 | |

| Reverse | 5′-TCTCCTGGTATGAAATGGCAAA-3′ | |||||

| IL-1β | Forward | 5′-GACCTGTTCTTTGAGGCTGAC-3′ | 62/45 | 578 | 30 | O′Connor et al. (2003) |

| Forward | 5′-TCCATCTTCTTCTTTGGGTATTGTT-3′ | |||||

| IL-6 | Reverse | 5′-ATACCACCCACAACAGACCAGT-3′ | 65/60 | 467 | 36 | O′Connor et al. (2003) |

| Forward | 5′-GATGAGTTGGATGGTCTTGGT-3′ | |||||

| IL-18 | Reverse | 5′-GACAAAAGAAACCCGCCTG-3′ | 62/45 | 369 | 28 | |

| Forward | 5′-ATCCCCATTTTCATCCTTCC-3′ | |||||

| TGF-β1 | Reverse | 5′-GCAACAACGCAATCTATGACA-3′ | 62/45 | 301 | 26 | |

| Forward | 5′-CCCTGTATTCCGTCTCCTTG-3′ | |||||

| IL-10 | Forward | 5′-AACTGCACCCACTTCCCAGT-3′ | 65/60 | 333 | 37 | |

| Reverse | 5′-CACTGCCTTGCTTTTATTCTCAC-3′ |

Western Blot Analysis

Individual tissues were homogenized in solution containing 0.3 M sucrose, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.0, 5 mM PMSF (Pefabloc SC + Compete, EDTA free, Roche Diagnostic). Tissue homogenates were incubated on ice for 1 h. The cell debris was removed by brief centrifugation at 1,000×g for 15 min at 4°C. Thereafter, the supernatant was centrifuged for 45 min (45,000×g, 4°C). The pellet (crude membrane fraction) was dissolved in homogenization solution, and protein concentration was determined according to Lowry et al. (1951). Ten percent SDS-PAGE gels were used to separate 80 μg of protein. The gels were blotted for 1 h at 100 mA, and proteins were transferred to a supported nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond-C Extra, AP Biotech) using semi-dry transfer unit (TE 77 PWR, Amersham Biosciences, USA). Ponceau S (Sigma) staining of membranes was used to briefly verify protein transfer. Non-specific binding sites were blocked by immersing the membranes in 5% dry non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline Tween (TBST) for 1 h on a shaker at the room temperature. All subsequent washes and primary/secondary antibody incubations were also carried in TBST. Proteins of individual types of ARs were determined by 1-h incubation in polyclonal primary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., USA). Dilution factors and protein weights recognized by antibodies are described in Table 2. Following three washes in TBST for 10 min each, membranes were incubated for 1 h at RT with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary anti-goat or anti-rabbit antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., USA) diluted 1:10,000. Bands were visualized by ECL Western blotting detection system (ECL; Amersham Biosciences). Optical density of individual bands (OD/mm2) was analyzed by PCBASE 2.08e software (Raytest, Inc.).

Table 2.

Antibodies used in Western blot analysis

| Primary antibody | Raised in | Working dilution | Cross-reactivity | Molecular weight (kDa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β1-AR | Rabbit | 1:500 | Mouse, rat, human | 50.4 |

| β2-AR | Rabbit | 1:500 | Mouse, rat, human | 65 |

| β3-AR | Goat | 1:200 | Mouse, rat | 43 |

| α1B-AR | Goat | 1:500 | Mouse, rat, human | 70 |

| α1D-AR | Goat | 1:500 | Mouse, rat, human | 45 |

| α2A-AR | Goat | 1:500 | Mouse, rat, human | 70 |

| α2C-AR | Goat | 1:500 | Mouse, rat, human | 60 |

All provided by Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., USA

Tissue Catecholamine Determination

Catecholamine concentration in the spleen was determined by the modified radioenzymatic method with subsequent chromatography on thin layers (Peuler and Johnson 1977; Jelokova et al. 2002). Tissue was weighted, immediately homogenized in 0.1 M HClO4, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. An aliquot of the supernatant was taken and diluted with water to a final concentration of 1 mg tissue in 50 μl of solution. Rest of the method was the same as for plasma catecholamine quantification as described previously (Kvetnansky et al. 1978).

Statistical Analysis

Each value represents an average of 7–8 animals. Results are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical differences among groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) corrected by Bonferonni test. Statistical significance p < 0.05 was considered to be significant (SigmaStat, version 3.1, Systat Software, Inc., USA).

Results

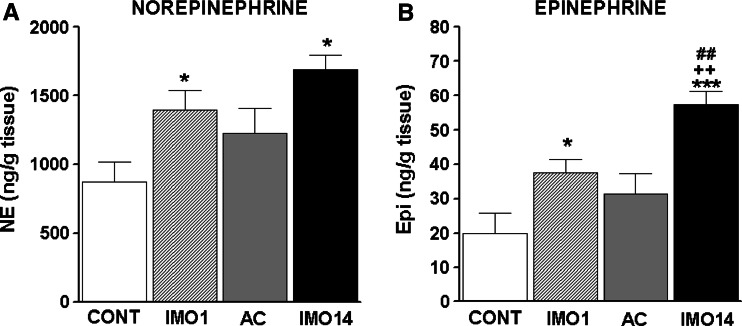

Immobilization stress increased the levels of NE as well as Epi in the spleen after single and especially after repeated IMO (14×) when compared to control, unstressed rats (Fig. 1). The levels of NE were much higher than those of Epi. The adapted controls (13×IMO + 1 day rest) were no longer different from non-stressed controls for both NE and Epi (Fig. 1). However, there was no difference between levels found after single and after repeated (14×) IMO for NE (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, the increase in Epi levels was more pronounced after repeated (14×) IMO compared to the increase after a single IMO (p < 0.01; Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Norepinephrine (NE; a) and epinephrine (Epi; b) concentration in the spleen of rats exposed to a single (1×) and repeated (14×) IMO (2 h daily). Single immobilization (IMO1; striped column) significantly increased concentrations of NE and Epi compared to the control, unstressed group of rats (CONT; empty column). Repeated IMO for 14 consecutive days (IMO14; black column) also revealed significant increase in NE and Epi compared to the control, non-stressed rats. Nevertheless, comparing this change to adapted control (13×IMO + 24 h rest; AC; gray column), significant increase was observed only in Epi levels. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM and represent an average of 7–8 animals. Statistical significance of IMO groups versus control (empty column) represents * p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.001; significance of repeated IMO versus adapted control (13×IMO + 24 h rest; AC; gray column) ++ p < 0.01; significance of repeated IMO versus single immobilization (IMO1; striped column) ## p < 0.01

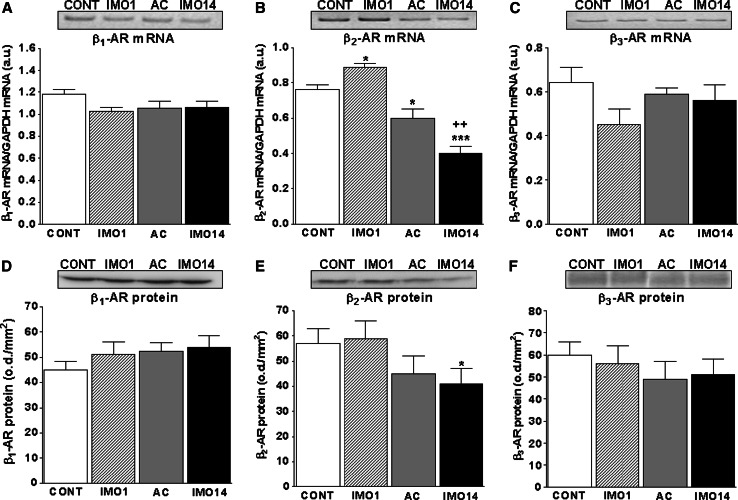

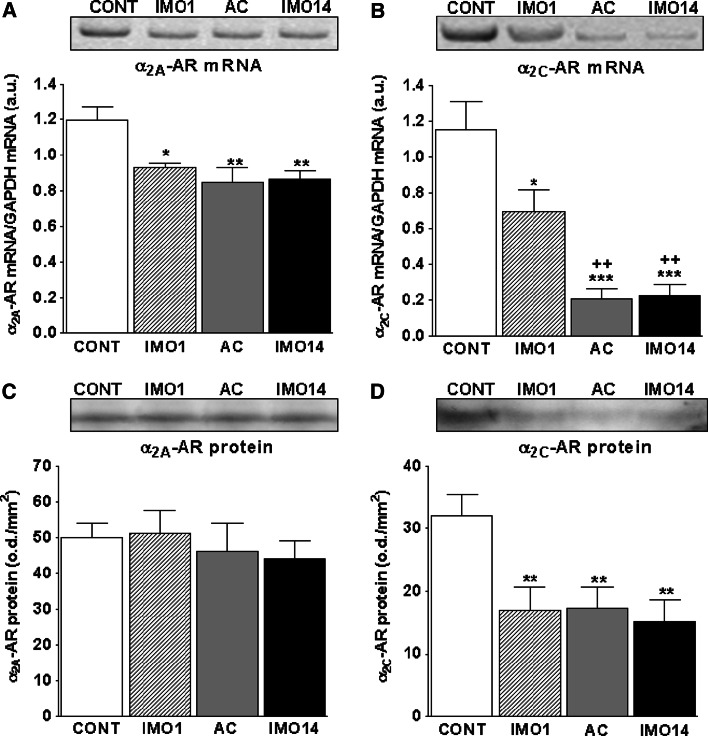

Using RT-PCR and Western blot, we detected expression of β1-, β2-, β3-, α1B-, α1D-, α2A- and α2C-ARs in control and stressed animals (Figs. 2, 3; Table 3). From among all detected receptors, we found a significant increase in the mRNA of β2-AR after a single IMO (p < 0.05) and significant decrease after repeated IMO (p < 0.001; Fig. 2b). Significant decrease in β2-AR after repeated IMO, compared to a single IMO, was observed also in protein levels (p < 0.05; Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2.

Gene expression and protein levels of β-adrenergic receptors in the spleen of rats exposed to a single (1×) and repeated (14×) IMO (2 h daily). Single immobilization (IMO1; striped column) significantly increased levels of β2-AR mRNA (b) compared to the control, unstressed group of rats (CONT; empty column). Repeated IMO for 14 consecutive days (IMO14; black column) as well as adapted control (13×IMO + 24 h rest; AC; gray column) revealed significant decrease of β2-AR mRNA (b) compared to control rats (CONT; empty column). The β2-AR protein level decreased only after repeated (14×) IMO (IMO14; e; black column). Both β1- and β3-AR’s mRNA (a, c) and protein levels (d, f) were not significantly changed by IMO. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM and represent an average of 7–8 animals. Statistical significance of IMO groups versus control, unstressed rats (CONT; empty column) represents * p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.001; significance of repeated IMO versus adapted control (13×IMO + 24 h rest; AC; gray column) represents ++ p < 0.01

Fig. 3.

Gene expression and protein levels of α2A- and α2C-adrenergic receptors in the spleen of rats exposed to a single (1×) and repeated (14×) IMO (2 h daily). Single immobilization (IMO1; striped column) significantly decreased levels of both α2A- and α2C-adrenergic receptor mRNA (a, b) compared to the control, unstressed group of rats (CONT; empty columns). Repeated IMO for 14 consecutive days (IMO14; black columns) as well as adapted control (13×IMO + 24 h rest; AC; gray columns) revealed also significant decrease of both α2A- and α2C-AR mRNA (a, b) compared to control, non-stressed rats (CONT; empty columns). Protein levels of α2C-AR were significantly decreased in both single (IMO1; striped column, d) as well as repeated IMO (IMO14; black column, d). Values are displayed as mean ± SEM and represent an average of 7–8 animals. Statistical significance of IMO stress versus control, unstressed rats (CONT; empty columns) represents * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001, significance of repeated IMO versus single IMO (IMO1; striped column) represents ++ p < 0.01

Table 3.

Gene expression and protein levels of α1B- and α1D-adrenergic receptor, gene expression of pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-18) and anti-inflammatory (TGF-β) cytokines in spleen of rats exposed to immobilization stress

| Group | mRNA (AU) | Protein (OD/mm2) |

|---|---|---|

| α1B-AR | ||

| Control | 0.57 ± 0.07 | 4,300 ± 590 |

| 1×IMO | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 5,100 ± 800 |

| 13×IMO + 24 h rest | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 5,600 ± 500 |

| 14×IMO | 0.82 ± 0.1 | 5,400 ± 700 |

| α1D-AR | ||

| Control | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 4,940 ± 700 |

| 1×IMO | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 5,880 ± 760 |

| 13×IMO + 24 h rest | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 4,870 ± 660 |

| 14×IMO | 0.78 ± 0.08 | 4,780 ± 780 |

| TNF-α | ||

| Control | 0.84 ± 0.05 | nt |

| 1×IMO | 0.7 ± 0.13 | nt |

| 13×IMO + 24 h rest | 0.88 ± 0.07 | nt |

| 14×IMO | 0.77 ± 0.06 | nt |

| IL-1β | ||

| Control | 0.84 ± 0.07 | nt |

| 1×IMO | 0.9 ± 0.12 | nt |

| 13×IMO + 24 h rest | 0.84 ± 0.04 | nt |

| 14×IMO | 1.02 ± 0.04 | nt |

| IL-18 | ||

| Control | 0.61 ± 0.07 | nt |

| 1×IMO | 0.82 ± 0.12 | nt |

| 13×IMO + 24 h rest | 0.67 ± 0.06 | nt |

| 14×IMO | 0.81 ± 0.05 | nt |

| TGF-β1 | ||

| Control | 0.75 ± 0.06 | nt |

| 1×IMO | 0.74 ± 0.09 | nt |

| 13×IMO + 24 h rest | 0.75 ± 0.05 | nt |

| 14×IMO | 0.88 ± 0.04 | nt |

No significant changes were found (p > 0.05)

nt not tested

The most significant changes were observed in the gene expression of α2-ARs (Fig. 3). Both α2A- and α2C-AR mRNA decreased significantly after a single IMO (p < 0.05), but this decrease was more pronounced after repeated IMO (p < 0.01; Fig. 3a, b). The drop in mRNA was significantly translated into protein only in the case of α2C-AR after single as well as after repeated IMO (p < 0.01; Fig. 3d).

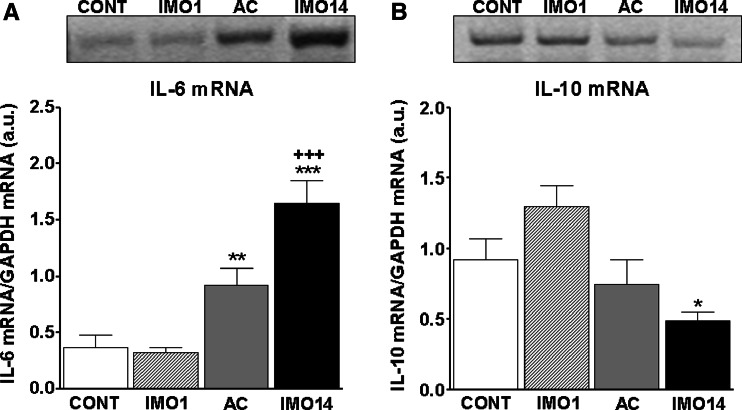

From among pro-inflammatory cytokines we detected significant changes only in the gene expression of interleukin-(IL)-6 (Fig. 4a), which increased after repeated (14×) IMO (p < 0.001) and was also still increased in adapted control group (p < 0.01; 13×IMO + 1 day rest; Fig. 4a). Anti-inflammatory IL-10 gene expression was not changed to such an extent (Fig. 4b), but we detected a significant decrease for IL-10 mRNA only after repeated (14×) IMO (p < 0.05; Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Gene expression of pro-inflammatory (IL-6) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokine in the spleen of rats exposed to a single (1×) and repeated (14×) IMO (2 h daily). Single immobilization (IMO1; striped column) did not reveal any significant changes in mRNA of IL-6 either of IL-10 compared to the control, unstressed group of rats (CONT; empty column). Repeated IMO for 14 consecutive days (IMO14; black column) as well as adapted control (13×IMO + 24 h rest; AC; gray column) revealed significant increase of IL-6 mRNA (a) compared to the control, non-stressed rats. The IL-10 mRNA (b) decreased significantly only after repeated IMO (IMO14; black column), but this change was not pronounced in such an extent as in IL-6 mRNA. Values are displayed as mean ± SEM and represent an average of 7–8 animals. Statistical significance of IMO stress versus absolute control (empty column) represents * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001, significance of repeated IMO versus adapted control (13×IMO + 24 h rest; AC; gray column) represents +++ p < 0.001

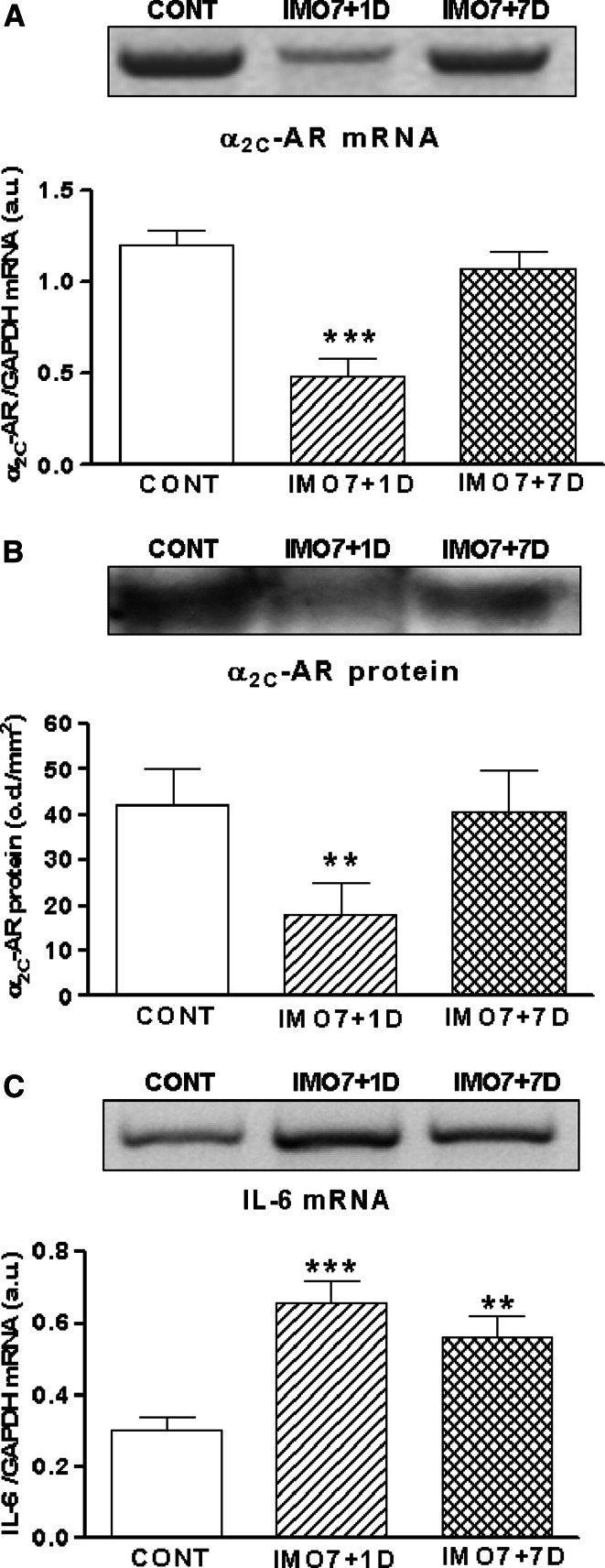

In order to check whether stress-induced changes of α2C-AR and IL-6 mRNA are stress-specific and reversible, we performed another experiment, in which rats were immobilized repeatedly (7×) for 2 h daily and sacrificed 1 day or 7 days of rest after the last IMO from their home cages. The interval 7 days of rest is long enough to “recover” from repeated IMO (unpublished data). Levels of α2C-AR mRNA (Fig. 5a) and protein (Fig. 5b) were still decreased 1 day after the repeated (7×) IMO (p < 0.01), but 7 days after the last IMO (7×) both values returned to control levels (Fig. 5a, b). We found significant increase of IL-6 mRNA 1 day (p < 0.001) and also 7 days of rest (p < 0.01) after repeated (7×) IMO (Fig. 5c). Only a tendency for a drop of IL-6 mRNA was observed 7 days after the last IMO. This suggests that IL-6 mRNA takes longer to return to control levels than α2C-AR mRNA and protein.

Fig. 5.

Gene expression and protein levels of α2C-adrenergic receptors and gene expression of IL-6 in the spleen of rats exposed to repeated IMO (7× for 2 h daily). Repeated IMO for seven consecutive days with 1 day rest (IMO7 + 1D; striped columns) revealed significant decrease of α2C-AR mRNA (a) and protein level (b) compared to control, unstressed group (CONT; empty columns). Seven days of rest after repeated IMO (IMO7 + 7D; hatched columns), the α2C-AR mRNA and protein turned back to control, non-stressed values (CONT; empty columns). The gene expression of IL-6 was significantly increased both 1 day (IMO7 + 1D; striped column) and 7 days of rest (IMO7 + 7D; hatched column) after repeated (7×) IMO compared to control rats (c). Values are displayed as mean ± SEM and represent an average of 7–8 animals. Statistical significance of repeated IMO + 1 day of rest versus control (CONT; empty column) represents ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001

We also detected the expression of the α1B-AR and α1D-AR in the spleen, but no significant changes were found either in mRNA or protein levels (p > 0.05; Table 3). Similarly, we found the gene expression of other pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-18) and anti-inflammatory (TGF-β1) cytokines, but there were no significant changes in their mRNA after single either after repeated IMO (p > 0.05; Table 3).

Discussion

Similarly as in our previous studies (Jelokova et al. 2002), we have found increased catecholamine levels after acute and mostly after chronic immobilization (IMO) stress in the spleen. Levels of norepinephrine (NE) were much higher compared to epinephrine (Epi) what points to locally released NE stores from sympathoneuronal terminals as a consequence of the stress-induced stimulation. No difference was observed between levels found after single and after repeated (14×) IMO for NE. On the other hand, the increase in Epi levels was more pronounced after repeated IMO compared to a single IMO (Fig. 1). Increased Epi levels could reflect uptake from the circulation when a huge rise in circulating Epi appears as a result of sustained stress-induced adrenomedullary stimulation and Epi secretion (Kvetnansky et al. 1978). Moreover, it is known that spleen possesses expression of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT), which is activated especially after repeated IMO (Jelokova et al. 2002). Therefore, this endogenous production of Epi might also affect Epi concentration and play a specific function especially after repeated stress exposure.

We observed different regulation of individual types of splenic α- and β-adrenergic receptors (ARs) by IMO stress. We found an increase of β2-AR mRNA, but no significant changes in protein level after an acute IMO. It is possible that protein level of β2-AR takes longer to change, especially after the first stress experience. The rise in β2-AR is not extraordinary. Increased β2-AR expression and density were observed for example on human immune cells after short-term exhaustive exercise, but this parameter returned to control level after 30 min of rest (Graafsma et al. 1990; Murray et al. 1992). On the contrary, repeated stress exposure induced decrease in β2-AR mRNA and protein (Fig. 2b, e). We can hypothesize that the drop in β2-AR occurred due to agonist-induced receptor down-regulation as a result of sustained and increased CA stimulation during stress sessions (Itoha et al. 2004). However, most prominent changes were found in α2-ARs. Both α2A- and α2C-AR mRNAs decreased after single and repeated IMO (Fig. 3a, b), but only for α2C-AR mRNA these changes positively correlated with protein levels (Fig. 3b). This could be interpreted as absent or less important physiological function of α2A-AR compared to α2C-AR in the spleen during IMO stress. From our previous experiments on other tissues we knew that stress-induced changes in catecholaminergic system are transient, and interval 7 days of rest was long enough to recover from repeated stress-induced changes. We observed that decrease in α2C-AR is reversible, and 7 days of rest after repeated (7×) IMO both α2C-AR mRNA and protein reached again the un-stressed, control values. The gene expression of other types of ARs was not changed by single either repeated IMO stress.

On the other hand, from all cytokines investigated, we detected significant increase in interleukin-(IL)-6 mRNA after repeated IMO, but only mild drop in IL-10 mRNA after repeated IMO as well (Fig. 4). The levels of IL-6 mRNA were still increased 7 days of rest after the repeated IMO and did not return to control values like α2C-AR (Fig. 5c). It is possible that IL-6 mRNA takes longer to reach again the control values.

There is strong evidence that stress and subsequent CA release can modulate cytokine production. Many studies reported that CAs inhibited pro-inflammatory and stimulated anti-inflammatory cytokine production in plasma (Gomez-Merino et al. 2005; Calcagni and Elenkov 2006; Elenkov 2008; Giraldo et al. 2009; McNamee et al. 2010). Nevertheless, these authors also confirmed that under certain conditions, stress hormones may actually facilitate production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-18, TNF-α in the plasma and tissues. Moreover, pro-inflammatory cytokine production is modulated primarily via both β2- (Hanania and Moore 2004; McNamee et al. 2010; Mnich et al. 2010; Takahashi et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2010) and α2-ARs (Straub et al. 2000; Romero-Sandoval et al. 2005; Flierl et al. 2007; Bai et al. 2009). For example, Nakamura et al. (1999) reported inhibitory properties of β2-AR in IL-6 production in renal macrophages, while Straub et al. (2000) observed stimulation of IL-6 production via β2-AR in splenic macrophages. Discrepancies among authors appear also in α2-AR involvement in pro-inflammatory cytokine production. While several studies reported inhibitory effects of α2-AR in this process (Straub et al. 2000; Romero-Sandoval et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2008), others observed stimulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine production via α2-AR (Flierl et al. 2007; Bai et al. 2009). It was also observed that α2-ARs inhibit, while β2-ARs stimulate IL-6 production by splenic macrophages (Straub et al. 2000). According to these data, stimulation or inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines via β2- and α2-ARs is dependent on many factors, such as character of stimuli, cell type investigated, local versus systemic effects, tissue microenvironment or stimulated versus un-stimulated cytokine production (Gornikiewicz et al. 2000; Maes et al. 2000). While β2-AR is located on almost all immune cell types, α2-ARs appeared to be mainly distributed in the marginal zone of the white pulp as well as in the red pulp of the rat spleen (Fernández-López and Pazos 1994). This suggests dual role in splenic function—regulation of immune cell function in the red pulp (primarily of macrophages) and CA release from sympathetic nerve terminals (Elenkov et al. 2000; Mignini et al. 2003). According to our results we can only speculate that increased levels of CAs, especially after chronic stress, may down-regulate β2- and α2-ARs in the spleen. As a consequence of declined pre-synaptic α2C-AR protein and removed negative feedback control, more CAs are released into synaptic cleft during repeated stress exposure and are available to affect ARs on effector cells. We might further suggest that down-regulation of ARs on immune cells in the spleen may up-regulate IL-6 gene expression. Since Straub et al. (2000) reported that α2-ARs inhibit IL-6 production by splenic macrophages, it might be possible that significant down-regulation of these receptors found in our stress experiments diminishes suppressive effect on IL-6 production, as we observed increased IL-6 mRNA in the spleen after chronic stress. Moreover, these stress-induced changes are reversible and after elimination of stress stimulus and recovery in normal conditions all values return to control, unstressed levels. Nevertheless, further experiments are needed to confirm our presumptions and determine the exact mechanism and consequences of β2- and α2C-AR’s down-regulation and IL-6 up-regulation.

In summary, we have shown decreased gene expression and protein of β2-AR and α2C-AR and rapidly increased gene expression of IL-6 in the spleen of repeatedly immobilized rats. Different signaling through these receptors might affect immune function in spleen during stress. Nevertheless, this proposal remains to be elucidated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract No. APVV-0148–06 and by VEGA Grants 2/0133/08 and 2/0188/09.

Conflict of interest statement

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aubert M, Guiramand J, Croce A, Roch G, Szafarczyk A, Vignes M (2001) An endogenous adrenoceptor ligand potentiates excitatory synaptic transmission in cultured hippocampal neurons. Cereb Cortex 11(9):878–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai A, Lu N, Guo Y, Chen J, Liu Z (2009) Modulation of inflammatory response via alpha2-adrenoceptor blockade in acute murine colitis. Clin Exp Immunol 156(2):353–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao JY, Huang Y, Wang F, Peng YP, Qiu YH (2007) Expression of alpha-AR subtypes in T lymphocytes a role of the alpha-ARs in mediating modulation of T cell function. Neuroimmunomodulation 14:344–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borger P, Hoekstra Y, Esselink MT, Postma DS, Zaagsma J, Vellenga E, Kauffman HF (1998) Beta-adrenoceptor-mediated inhibition of IFN-gamma, IL-3, and GM-CSF mRNA accumulation in activated human T lymphocytes is solely mediated by the beta2-adrenoceptor subtype. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 19:400–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcagni E, Elenkov I (2006) Stress system activity, innate and T helper cytokines, and susceptibility to immune-related diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1069:62–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Hudson CA, Moynihan JA (2007) Chronic foot shock induces hyperactive behaviors and accompanying pro- and anti-inflammatory responses in mice. J Neuroimmunol 186(1–2):63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin NM, Mills KH, Connor TJ (2009) Psychological stress increases expression of IL-10 and its homolog IL-19 via beta-adrenoceptor activation: reversal by the anxiolytic chlordiazepoxide. Brain Behav Immun 23(3):371–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov IJ (2008) Neurohormonal-cytokine interactions: implications for inflammation, common human diseases and well-being. Neurochem Int 52(1–2):40–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov IJ, Vizi ES (1991) Presynaptic modulation of release of noradrenaline from the sympathetic nerve terminals in the rat spleen. Neuropharmacology 30:1319–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov IJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP, Vizi ES (2000) The sympathetic nerve—an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain a the immune system. Pharmacol Rev 52:595–638 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltze M (1996) Functional evidence for an alpha 1B-adrenoceptor mediating contraction of the mouse spleen. Eur J Pharmacol 311:187–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emeny RT, Gao D, Lawrence DA (2007) Beta1-adrenergic receptors on immune cells impair innate defenses against Listeria. J Immunol 178(8):4876–4884 15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure C, Gouhier C, Langer SZ, Graham D (1995) Quantification of alpha 1-adrenoceptor subtypes in human tissues by competitive RT-PCR analysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 213:935–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsner P, Hofer D, Rinner I, Porta S, Korsatko W, Schauenstein K (1995) Adrenergic suppression of peripheral blood T cell reactivity in the rat is due to activation of peripheral alpha 2-receptors. J Neuroimmunol 57(1–2):27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-López A, Pazos A (1994) Identification of alpha 2-adrenoceptors in rat lymph nodes and spleen: an autoradiographic study. Eur J Pharmacol 252(3):333–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, Nadeau BA, Chen AJ, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, McGuire SR, List RP, Day DE, Hoesel LM, Gao H, Van Rooijen N, Huber-Lang MS, Neubig RR, Ward PA (2007) Phagocyte-derived catecholamines enhance acute inflammatory injury. Nature 449(7163):721–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo E, Garcia JJ, Hinchado MD, Ortega E (2009) Exercise intensity-dependent changes in the inflammatory response in sedentary women: role of neuroendocrine parameters in the neutrophil phagocytic process and the pro-/anti-inflammatory cytokine balance. Neuroimmunomodulation 16(4):237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Merino D, Drogou C, Chennaoui M, Tiollier E, Mathieu J, Guezennec CY (2005) Effects of combined stress during intense training on cellular immunity, hormones and respiratory infections. Neuroimmunomodulation 12(3):164–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornikiewicz A, Sautner T, Brostjan C, Schmierer B, Függer R, Roth E, Mühlbacher F, Bergmann M (2000) Catecholamines up-regulate lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-6 production in human microvascular endothelial cells. FASEB J 14(9):1093–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graafsma SJ, Van Tits LJH, Willems PHGM, Hectors MPC, Rodrigues de Miranda JF, DePont JHHM, Thien T (1990) β2-Adrenoceptor up-regulation in relation to camp production in human lymphocytes after physical exercise. Brl J Clin Pharmacol 30:142S–144S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanania NA, Moore RH (2004) Anti-inflammatory activities of beta2-agonists. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 3(3):271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieble JP (2000) Adrenoceptor subclassification: an approach to improved cardiovascular therapeutics. Pharm Acta Helv 74:163–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman KL, Knudson CA, Carr PA, Doze VA, Porter JE (2005) Adrenergic receptor characterization of CA1 hippocampal neurons using real time single cell RT-PCR. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 139(2):267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoha C-E, Kizakia T, Hitomia Y, Hanawab T, Kamiyab S, Ookawarac T, Suzukic K, Izawad T, Saitohe D, Hagaf S, Ohnoa H (2004) Down-regulation of β2-adrenergic receptor expression by exercise training increases IL-12 production by macrophages following LPS stimulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 322:979–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelokova J, Rusnak M, Kubovcakova L, Buckendahl P, Krizanova O, Sabban EL, Kvetnansky R (2002) Stress increases gene expression of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase in spleen of rats via pituitary-adrenocortical mechanism. Psychoneuroendocrinology 27:619–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavelaars A (2002) Regulated expression of alpha-1 adrenergic receptors in the immune system. Brain Behav Immun 16:799–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kin NW, Sanders VM (2006) It takes nerve to tell T and B cells what to do. J Leukoc Biol 79(6):1093–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohm AP, Sanders VM (2001) Norepinephrine and beta 2-adrenergic receptor stimulation regulate CD4+ T and B lymphocyte function in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacol Rev 53(4):487–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubovcakova L, Micutkova L, Sabban EL, Krizanova O, Kvetnansky R (2001) Identification of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression in rat spleen. Neurosci Lett 310(2–3):157–160 14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Mikulaj L (1970) Adrenal and urinary catecholamines in rats during adaptation to repeated immobilization stress. Endocrinology 87(4):738–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Sun CL, Lake CR, Thoa N, Torda T, Kopin IJ (1978) Effect of handling and forced immobilization on rat plasma levels of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Endocrinology 103(5):1868–1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas O, Martinez JA, Marti A (2003) Effects of a beta3-adrenergic agonist on the immune response in diet-induced (cafeteria) obese animals. J Physiol Biochem 59(3):183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ (1951) Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193:265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Lin A, Kenis G, Egyed B, Bosmans E (2000) The effects of noradrenaline and alpha-2 adrenoceptor agents on the production of monocytic products. Psychiatry Res 96(3):245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamee EN, Ryan KM, Kilroy D, Connor TJ (2010) Noradrenaline induces IL-1ra and IL-1 type II receptor expression in primary glial cells and protects against IL-1beta-induced neurotoxicity. Eur J Pharmacol 626(2–3):219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer JC, MacNeil BJ, Sanders V, Pylypas S, Jansen AH, Greenberg AH, Nance DM (2004) Stress-induced suppression of in vivo splenic cytokine production in the rat by neural and hormonal mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun 18(3):262–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignini F, Streccioni V, Amenta F (2003) Autonomic innervation of immune organs and neuroimmune modulation. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol 23(1):1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnich SJ, Hiebsch RR, Huff RM, Muthian S (2010) Anti-inflammatory properties of CB1-receptor antagonist involves beta2 adrenoceptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 333(2):445–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller R, Steffen HM, Juretzko P, Bönner G, Krone W (1995) Plasma catecholamines, thrombocyte alpha 2- and lymphocyte beta 2-adrenoceptor densities in hypertensive patients with low or normal plasma renin concentrations. Angiology 46(3):221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DR, Irwin M, Rearden CA, Ziegler M, Motulsky H, Maisel AS (1992) Sympathetic and immune interactions during dynamic exercise. Mediation via a beta 2-adrenergic-dependent mechanism. Circulation 86:203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myslivecek J, Novakova M, Palkovits M, Krizanova O, Kvetnansky R (2006) Distribution of mRNA and binding sites of adrenoceptors and muscarinic receptors in the rat heart. Life Sci 79(2):112–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Johns EJ, Imaizumi A, Yanagawa Y, Kohsaka T (1999) Effect of beta(2)-adrenoceptor activation and angiotensin II on tumour necrosis factor and interleukin 6 gene transcription in the rat renal resident macrophage cells. Cytokine 11(10):759–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor KA, Johnson JD, Hansen MK, Wieseler Frank JL, Maksimova E, Watkins LR, Maier SF (2003) Peripheral and central proinflammatory cytokine response to a severe acute stressor. Brain Res 991(1–2):123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peuler JD, Johnson GA (1977) Simultaneous single isotope radioenzymatic assay of plasma norepinephrine, epinephrine and dopamine. Life Sci 21(5):625–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp M, Brede M, Hein L (2002) Physiological significance of alpha(2)-adrenergic receptor subtype diversity: one receptor is not enough. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283:R287–R295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci A, Bronzetti E, Conterno A, Greco S, Mulatero P, Schena M, Schiavone D, Tayebati SK, Veglio F, Amenta F (1999) Alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtypes in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Hypertension 33:708–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokosh DG, Bailey BA, Stewart AF, Karns LR, Long CS, Simpson PC (1994) Distribution of alpha 1C-adrenergic receptor mRNA in adult rat tissues by RNase protection assay a comparison with alpha 1B a alpha 1D. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 200:1177–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Sandoval EA, McCall C, Eisenach JC (2005) Alpha2-adrenoceptor stimulation transforms immune responses in neuritis and blocks neuritis-induced pain. J Neurosci 25(39):8988–8994 28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomonsson M, Oker M, Kim S, Zhang H, Faber JE, Arendshorst WJ (2001) Alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes on rat afferent arterioles assessed by radioligand binding and RT-PCR. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281(1):F172–F178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauenstein K, Felsner P, Rinner I, Liebmann PM, Stevenson JR, Westermann J, Haas HS, Cohen RL, Chambers DA (2000) In vivo immunomodulation by peripheral adrenergic a cholinergic agonists/antagonists in rat a mouse models. Ann N Y Acad Sci 917:618–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HM, Sha LX, Kennedy JL, Ou DW (1994) Adrenergic receptors regulate macrophage secretion. Int J Immunopharmacol 16(11):905–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson JR, Westermann J, Liebmann PM, Hörtner M, Rinner I, Felsner P, Wölfler A, Schauenstein K (2001) Prolonged alpha-adrenergic stimulation causes changes in distribution and lymphocyte apoptosis in the rat. J Neuroimmunol 120(1–2):50–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub RH, Herrmann M, Berkmiller G, Frauenholz T, Lang B, Schölmerich J, Falk W (1997) Neuronal regulation of interleukin 6 secretion in murine spleen: adrenergic and opioidergic control. J Neurochem 68(4):1633–1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub RH, Schaller T, Miller LE, von Hörsten S, Jessop DS, Falk W, Schölmerich J (2000) Neuropeptide Y cotransmission with norepinephrine in the sympathetic nerve-macrophage interplay. J Neurochem 75(6):2464–2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi HK, Mori S, Liu K, Wake H, Zhang J, Liu R, Yoshino T, Nishibori M (2010) Beta2-adrenoceptor stimulation inhibits advanced glycation end products-induced adhesion molecule expression and cytokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Eur J Pharmacol 627(1–3):313–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayebati SK, Bronzetti E, Morra Di Cella S, Mulatero P, Ricci A, Rossodivita I, Schena M, Schiavone D, Veglio F, Amenta F (2000) In situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry of alpha1-adrenoceptors in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Auton Pharmacol 20(5–6):305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada Y, Tomita K, Nonoguchi H, Yang T, Marumo F (1993) Expression of endothelin-3 mRNA along rat nephron segments using polymerase chain reaction. Kidney Int 44(6):1273–1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CL, Tsai PS, Huang CJ (2008) Effects of dexmedetomidine on regulating pulmonary inflammation in a rat model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan 46(4):151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D, Zhang Y, Stuart C, Miao J, Zhang Y, Li C, Zeng X, Hanley G, Moorman J, Yao Z, Woodruff M (2006) Chronic restraint stress modulates expression of genes in murine spleen. J Neuroimmunol 177(1–2):11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Taniguchi T, Tanaka T, Shinozuka K, Kunitomo M, Nishiyama M, Kamata K, Muramatsu I (2002) Alpha-1 adrenoceptor up-regulation induced by prazosin but not KMD-3213 or reserpine in rats. Br J Pharmacol 135(7):1757–1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Fievez L, Cheu E, Bureau F, Rong W, Zhang F, Zhang Y, Advenier C, Gustin P (2010) Anti-inflammatory effects of formoterol and ipratropium bromide against acute cadmium-induced pulmonary inflammation in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 628(1–3):171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]