Abstract

Background

The personalized care planning is a collaborative process used in managing long-term health conditions when the person and health professionals identify and discuss problems caused by or related to the health condition and develop a plan to address them.

Objective

The aim of the study was to map the evidence on the impact of personalized care planning management on health outcomes in persons with multiple long-term health problems in the community.

Methods

Scoping review was based on the Joanna Briggs Institute protocol; the search strategy was carried out in platforms and databases online; the participants are adults, with chronic disease or long-term health conditions, in the period from 2016 to 2021, in English, Spanish, and Portuguese; the exclusion criteria included studies of adults with dementia and intellectual disability; 22 studies were obtained. We applied critical appraisal, and two independent reviewers performed data extraction; data synthesis was performed in narrative form.

Results

Nursing interventions, the strategies used by nurses, and the production of health gains (maintaining the level of health and well-being) promoted by nurses through the proper management of personalized care planning were identified.

Conclusions

Nurses develop a wide range of interventions, using various strategies that promote health gains through the proper management of personalized care planning.

Contributions to the Practice

Personalized care planning focuses on people with multimorbidity, and the health gains reduce, also, the nurses’ workload.

Keywords: Chronic diseases, Long-term care, Nursing care plan, Patient care planning, Primary health care

Palavras Chave: Doenças crónicas, Cuidados de longa duração, Plano de cuidados de enfermagem, Plano individual de cuidados, Cuidados de saúde primários

Resumo

Contexto

O plano individual de cuidados é um processo colaborativo utilizado na gestão de condições de saúde a longo prazo, quando a pessoa e os profissionais de saúde identificam e discutem problemas causados ou relacionados com a condição de saúde e desenvolvem um plano para os resolver.

Objetivo

mapear as evidências sobre o impacto da gestão do Plano Individual de Cuidados nos resultados de saúde de pessoas com múltiplos problemas de saúde de longo prazo na comunidade.

Métodos

scoping review com base no protocolo do Joanna Briggs Institute; a estratégia de pesquisa foi realizada em plataformas e bases de dados online; os participantes são adultos, com doença crónica ou com condições de saúde de longa duração, no período de 2016 a 2021; os idiomas considerados foram inglês, espanhol e português; os critérios de exclusão incluíram estudos de adultos com demência e deficiência intelectual; foram recuperados 22 estudos. Foi aplicada uma avaliação crítica e dois revisores independentes realizaram a extração de dados; a síntese dos dados foi realizada na forma de narrativa.

Resultados

identificaram-se as intervenções de enfermagem, as estratégias utilizadas pelos enfermeiros e a produção de ganhos em saúde (manutenção do nível de saúde e bem-estar) promovidos pelos enfermeiros através da gestão adequada do plano individual de cuidados.

Conclusões

os enfermeiros desenvolvem um leque variado de intervenções, utilizando várias estratégias que promovem ganhos em saúde através da gestão adequada do plano individual de cuidados.

Contribuições para a prática

o plano de cuidado individual incide em pessoas com multimorbidade e os ganhos em saúde reduzem, também, a carga de trabalho do enfermeiro.

Introduction

The aging of the Portuguese population, the increased incidence of chronic diseases, and long-term health problems have been determining significant changes in society. Therefore, it is necessary to generate responses that mobilize the different existing resources to meet these people’s needs [1]. This is probably a reality that covers many countries, especially in Europe and North America.

We can add a concern from the end of the 20th century or the beginning of this century that the empowerment of citizens must be assumed by nurses as a priority. “Health promotion and disease prevention are two fundamental and transversal axes at all levels of health care provision” [1] [p. 5]. Nurses need to acquire skills and develop management competencies that allow them to overcome these challenges.

Also, and this could be our third presupposition, the participation of people in health decision-making is currently presented as a central theme in health policies. This is supported by the belief that people’s involvement and empowerment are essential to improve health outcomes. Starting from this aim, “… it is necessary to mobilize local communities for the protection and promotion of their health, through local health strategies, widely participated. To this end, it is important to invest in each citizen’s ability to make informed decisions about their health, throughout their life course” [2] [p. 8].

Anchored in these three assumptions, about long-term health problems, the role of nurses in empowering citizens, and the involvement of people in health decisions, starting with their own, draws a working horizon in which we inscribe the personalized care planning. In Portugal, the National Health Service’s Person-Centered Care states that support for self-care is based on partnership and working between the individual and the caregiver in a continuous process of communication, negotiation, and two-way decision-making, where both parties contribute to the care planning process to achieve the best possible outcomes for the person [3].

Personalized care planning “…is a collaborative process used in managing chronic health conditions in which people and health professionals identify and discuss problems caused by or related to the person’s health condition and develop a plan to address them.” It further suggests that it be developed through “… a conversation, or series of conversations, in which they jointly agree on goals and actions for the management of the person's health condition” [4] [p. 1].

Personalized care planning is a tool intended for people with various health problems to manage their health care. It allows them to record, in partnership with the health professionals who accompany them, the current situation and the goals set for a certain period, thus sharing the work and responsibility among all the commitments involved in this process. Personalized care planning allows monitoring of the actions and behaviors agreed upon to achieve these goals and evaluates the results reached [2].

Personalized care planning in Portugal is based on the use of the technology provided in the National Health Service Portal; alternatively, when justified, other digital or non-digital support can be used if the first is not available. This plan requires the nurse to monitor the records, the result of the planned actions, and the regular evaluation that each person performs in its implementation [5]. Therefore, these aspects embedded the concept of “good management,” in health care planning and implementation, related to goals, monitoring (also the accorded metrics), interventions, and continuous assessment.

Materials and Methods

To identify and describe the evidence on the management of personalized care planning in people with multiple long-term health problems in the community, we conducted a literature scoping review using the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology [6]. The project is registered in the OSF Registries database, available at osf.io/5uwpt or in DOI 10.17605/OSF. IO/5UWPT.

Review Question

The questions that guided the research and which were intended to be answered were as follows:

-

1.

What are the nursing interventions in managing personalized care planning in people with multiple long-term health problems in the community?

-

2.

What are the strategies used by nurses in the good management of personalized care planning in people with multiple long-term health problems in the community?

-

3.

Does the good management of personalized care planning by nurses produce health gains in people with multiple long-term health problems in the community?

We have followed the population, concept, context. Population refers to adult people – a person who has reached total growth or maturity. Adults are 19–44 years old, with multiple long-term health problems; concept refers to the importance of understanding the nurse’s management of personalized care planning; context relates to nursing care in the community.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The search included all types of published studies, available in full text, in which the participants are adults, with chronic disease or long-term health conditions, of both genders, where the intervention included collaborative planning in supporting the self-management of the person’s health problems (between the person and the nurse), in the period from January 1, 2016, to May 31, 2021, in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Exclusion criteria included studies of adults with dementia, intellectual disability, or communicable diseases, and studies with multidisciplinary teams in which a nurse was not identified as a member.

Search Strategy

The search strategy was carried out in platforms and databases: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Academic Search Complete, MedicLatina (Via EBSCO), no – Portugal Open Access Scientific Repository (RCAAP), ClinicalTrials.gov, Epistemonikos, National Biotechnology Information Center (NCBI) search database, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SCIELO), a manual search was made using the Google Academic Search tool, and indexed controlled vocabulary from each database was searched. Articles in which the research participants were adult participants (19–44 years) of both sexes, suffering from chronic diseases, in which the intervention includes a collaborative plan that supports self-management of the person’s health problems, and in which the different contexts of care provision were considered, namely, primary, or continuous health care were included. The search formulas were adapted to each database as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Databases and research strategy

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE with full text (Via EBSCO) | S1: (MM “Long-Term Care”) OR TI long term care OR AB long term care |

| S2: (MM “Chronic Disease”) OR TI Chronic Disease* OR AB Chronic Disease* | |

| S3: TI chronic illness OR AB chronic illness | |

| S4: TI “Nursing Care Plan*” OR AB Nursing Care Plan* | |

| S5: (MM “Patient Care Planning”) OR TI Patient Care Plan* OR AB Patient Care Plan* | |

| S6: (MH “Disease Management+”) OR TI Disease* Management OR AB Disease* Management | |

| S7: TI “personalized care Plan*” OR AB personalized care Plan* | |

| S8: (MM “Primary Health Care”) OR TI Primary Health Care OR AB Primary Health Care | |

| S9: (MH “Community Health Nursing”) OR TI Community Health Nurs* OR AB Community Health Nurs* | |

| S10: S1 OR S2 OR S3 | |

| S11: S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 | |

| S12: S8 OR S9 | |

| S13: S10 AND S11 AND S12 | |

| Limiters - Publication Date: 1 January 2016–31 May 2021; Age-Related: All Adult: 19+ years | |

| CINAHL plus with full text (Via EBSCO) | S1: (MM “Long Term Care”) OR TI long term care OR AB long term care |

| S2: (MM “Chronic Disease”) OR TI chronic disease* OR AB chronic disease* | |

| S3: TI chronic illness* OR AB chronic illness* | |

| S4: (MH “Nursing Care Plans+”) OR TI Nursing Care Plans* OR AB Nursing Care Plans* | |

| S5: (MM “Patient Care Plans”) OR TI Patient Care Plan* OR AB Patient Care Plan* | |

| S6: (MM “Disease Management”) OR TI Disease* Management OR AB Disease* Management | |

| S7: TI illness management OR AB illness management | |

| S8: TI personalised care plan* OR AB personalised care plan* | |

| S9: (MM “Primary Health Care”) OR TI Primary Health Care OR AB Primary Health Care | |

| S10: TI community health nurs* OR AB community health nurs* | |

| S11: (MM “Community Health Nursing”) | |

| S12: S9 OR S10 OR S11 | |

| S13: S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 | |

| S14: S1 OR S2 OR S3 | |

| S15: S12 AND S13 AND S14 | |

| Limiters - Publication Date: 1 January 2016–31 May 2021; Age-Related: All Adult: 19+ years | |

| Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Via EBSCO) | S1: TI personalised care plan* OR AB personalised care plan* |

| S2: TI individual care plan* OR AB individual care plan* | |

| S3: S1 OR S2 | |

| Limiters - Publication Date: 1 January 2016–31 May 2021 | |

| Cochrane central register of controlled trials (Via EBSCO) | S1: TI Nurs* Care Plan* OR AB Nurs* Care Plan* |

| S2: TI community health nurs* OR AB community health nurs* | |

| S3: TI long term care OR AB long term care | |

| S4: S1 OR S2 | |

| S5: S3 AND S4 | |

| Limiters - Publication Date: 1 January 2016–31 May 2021 | |

| Academic search complete (Via EBSCO) | S1: DE “LONG-term health care” OR TI long term health care OR AB long term health care |

| S2: (chronic disease or chronic illness or long term conditions or chronic conditions) OR TI (chronic disease or chronic illness or long term conditions or chronic conditions) OR AB (chronic disease or chronic illness or long term conditions or chronic conditions) | |

| S3: DE “NURSING care plans” OR TI Nursing Care Plan* OR AB Nursing Care Plan* | |

| S4: DE “PATIENT-centered care” OR TI patient centered care OR AB patient centered care | |

| S5: DE “DISEASE management” OR TI disease management OR AB disease management | |

| S6: DE “COMMUNITY health nursing” OR TI community health nursing OR AB community health nursing | |

| S7: S1 OR S2 | |

| S8: S3 OR S4 OR S5 | |

| S9: S6 AND S7 AND S8 | |

| Limiters - Publication Date: 1 January 2016–31 May 2021 | |

| MedicLatina (Via EBSCO) | S1: TI long term care OR AB long term care |

| S2: TI (chronic disease or chronic illness or long term conditions or chronic conditions) OR AB (chronic disease or chronic illness or long term conditions or chronic conditions) | |

| S3: TI nursing care plan* OR AB nursing care plan* | |

| S4: TI (patient-centered care or client-centered care or person-centered care) OR AB (patient-centered care or client-centered care or person-centered care) | |

| S5: TI disease management OR AB disease management | |

| S6: TI community health nursing OR AB community health nursing | |

| S7: TI primary health care OR AB primary health care | |

| S8: S1 OR S2 | |

| S9: S3 OR S4 OR S5 | |

| S10: S6 OR S7 | |

| S11: S8 AND S9 AND S10 | |

| Limiters - Publication Date: 1 January 2016–31 May 2021 | |

| Scientific electronic library online (SCIELO) | ((ab:(personalised care plan))) OR (individualized care plan) AND network:org AND -network:rve AND (year_cluster:(“2016” OR “2018” OR “2019” OR “2020” OR “2021”)) |

| Epistemonikos | (title:(Personalised care plan) OR abstract:(Personalised care plan)) AND (title:(Chronic Disease) OR abstract:(Chronic Disease)) |

| Limiters - last 5 years, adult | |

| National Biotechnology Information Center (NCBI) search database | (title:(Personalized plan of care) OR abstract:(Personalized plan of care)) AND (title:(Chronic Disease) OR abstract:(Chronic Disease)) |

| Limiters - last 5 years, adult | |

| ClinicalTrials.gov | Personalized Care Plan AND AREA[ConditionSearch] chronic illness AND AREA[StdAge] EXPAND[Term] COVER[FullMatch] “Adult” |

| Open Access Scientific Repositories of Portugal (RCAAP) | Individual Care Plan |

| Google academic search | Individual Care Plan/Person-centered Care |

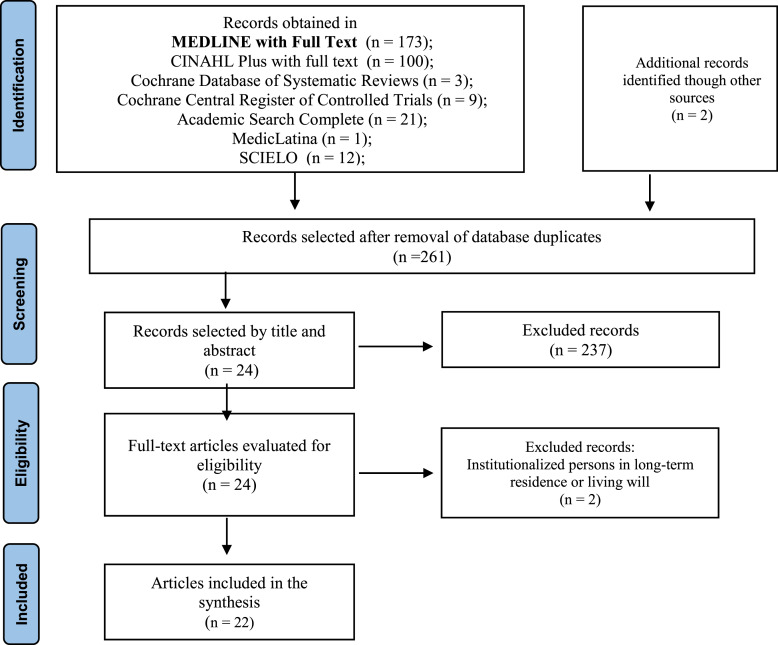

Selection of Studies

Based on the strategy described, 158 articles were accessed through scientific databases and online repositories: MEDLINE® (n = 173), CINAHL® (n = 100), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews® (n = 3), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials® (n = 9), Academic Search Complete® (n = 21), MedicLatina® (n = 1), SCIELO® (n = 12), and Google Scholar, making a total of 321 articles. Sixty duplicate articles were excluded. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and reading the title and abstract, 237 articles were rejected, and 2 articles were also excluded after their full reading due to the context of the investigation. A total of 22 articles were analyzed, as shown in Figure 1, showing the process of search, exclusion, and selection of the studies found. The PRISMA flow diagram is shown in Figure 1 for scoping reviews according to Joanna Briggs Institute, which identifies the stages of the search performed until the final number of articles to be included in this scoping review.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of selecting articles for review.

Results

We obtained 22 studies described in Table 2, and the data extraction process was performed according to the methodology for scoping reviews developed by the Joana Briggs Institute. Two reviewers extracted the data independently. The interpretation of the results was based on the questions that guided the research, so we presented them with a summary of the main characteristics and objectives.

Table 2.

Summary of the results of the included studies

| Author/country/year | Research goal |

|---|---|

| Dunn et al./UK/2021 [7] | The study aims to determine the impact of community nurse-led interventions on the need for hospital use among the elderly |

| Birke et al./Denmark/2020 [8] | Assess the feasibility of a complex person-centered intervention with multiple long-term problems in primary health care |

| Askew et al./Australia/2020 [9] | The exploratory case study in the home offered multidisciplinary care focused on the indigenous person with chronic illness in primary health care in an urban setting |

| Peart et al./Australia/2020 [10] | Explore the experience of health care professionals in coordinating care for people living with multimorbidity who need care coordination to help them manage their health |

| Sakellarides/Portugal/2020 [11] | The individual care plan is an essential tool for the effective management of people’s pathway through the services they need |

| Nyberg et al./Sweden/2019 [12] | The study aims to assess the feasibility of an application for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, its design, and study procedures, and to increase understanding of the potential effect of the tool to provide guidance for a future large-scale trial |

| Costa et al./Portugal/2019 [13] | Health literacy as a driver of people’s activation. Activation represents a person’s knowledge, technical ability, confidence, and motivation to self-manage their health and/or illness |

| Green and Jester/UK/2019 [14] | The English National Health Service Long-Term Plan outlines the goals for managing the increasing demand for the health service: decreasing hospital admissions, shorter lengths of stay through improved recovery pathways, increased management of people in primary health care, and ensuring a person-centered approach |

| Lima Toivanen et al./Latin America and Caribbean/2018 [15] | Study to validate the use of a newly developed framework to evaluate the contribution of digital health to improving the delivery of integrated, person-centered services in primary health care in Latin America and the Caribbean |

| Fortin et al./Canada/2019 [16] | This study aimed to explore the effects of the intervention of chronic disease prevention and management services in primary health care on people with long-term health problems and their families in primary health care |

| Peterson et al./South Africa/2019 [17] | This study aimed to evaluate an integrated, task-shared collaborative care package for people with chronic illness and coexisting symptoms of depressive disorder and alcohol use |

| Lukewich et al./Canada/2018 [18] | The purpose of this study was to understand better the organizational attributes of teams in primary health care, focusing specifically on team composition, nursing roles, and strategies that support chronic disease management |

| Srinivasan et al./India/2018 [19] | The study evaluates the effects of integrating people’s mental health and chronic disease management in primary health care through a collaborative care model to improve the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of depression in rural India |

| Askerud and Conder/New Zealand/2017 [20] | The research synthesizes the experiences of people with long-term health problems about the quality of care of the case management model by nurses in primary health care |

| Khan et al./UK/2017 [21] | The study aimed to describe self-care and support behavior among people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and explore the behavior associated with a self-care plan |

| Bauer and Bodenheimer/USA/2017 [22] | This article explores the challenges and opportunities for nurses in primary health care in the 21st century. It examines the likelihood of expanded roles for nurses to improve quality and add capacity to the primary health care workforce |

| Leine et al./Norway/2017 [23] | The study explores the experiences of people with the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with a partnership-based nursing practice program in the home |

| Housden et al./Canada/2017 [24] | In Canada, primary health care reform has encouraged innovations, including nurse-led and group medical visits. Nurse-led visits provide an opportunity to examine the barriers and facilitating factors for implementing this innovation in primary health care |

| Sharma et al./USA/2016 [25] | An observational whether health coaching, whether it is effective for self-management and maintenance of cardiovascular risk factors after a health coaching intervention |

| Kvale et al./USA/2016 [26] | The study examined the person-owned survivor transition treatment for activated and empowered survivors, which is a coaching encounter based on the chronic treatment model that uses motivational interviewing techniques to engage breast cancer survivors |

| Ostlund et al./Sweden/2016 [27] | The purpose of this study was to describe what verbal behaviors/conversation types were recorded during motivational interviewing sessions between primary health care nurses and people with multiple health problems |

| Gálvez-Cano et al./Peru/2016 [28] | The study aims to gain insight into the person’s health status through a comprehensive geriatric assessment and allows the nurse to develop an individualized care plan in conjunction with the person/family’s interests and values |

Discussion

When assessing the impact of good, personalized care planning management on health outcomes in people with multiple long-term health problems in the community, three questions arise: what nursing interventions, what strategies nurses use, and what production of health gains. The nurses’ intervention focuses on the prevention and management of chronic disease. They support the empowerment of people for self-management of long-term chronic illness, therapeutic adherence, maintenance of health status and quality of life, and use of health services. As negative aspects, they report that people needed a more extended follow-up period to maintain motivation and knowledge acquisition [16].

The nurse’s intervention is based on the management of the care plan with the person, from assessment, counseling, teaching, and support in the informed decision [18], in the identification of cases, to monitoring throughout the person’s progress, with referral to the multidisciplinary team [19]. The nurse’s action with the person with long-term problems can also have interventions [7, 19, 23, 26]: the empowerment of the person for self-management of their long-term health situation, the support to the person in establishing goals and a plan to improve their health, the promotion of motivation and confidence for self-management, the discussion to identify modifiable behavioral risks and information so that the person can make their choices, the support in self-management, and increase the person’s capacity to manage (self-management) their long-term health situation.

Self-management support programs should be collaborative between health professionals and the person to help them acquire skills to understand and manage their therapeutic plans and disease exacerbations, enable them to adopt healthier behaviors, and manage the socio-emotional consequences of the disease more effectively [21]. Involving the person in the individual plan is a significant challenge for health care professionals managing long-term health conditions [21].

Nurses can use health coaching to engage people in self-management of their long-term health problems [25]. It is emphasized to promote coaching and training of the person to improve health behaviors and adherence to the therapeutic plan for people with chronic health conditions [23].

As for the work methodology, case management by the nurse enhances the empowerment and follow-up of people with long-term problems, associated with access, response time, availability, trust, and communication. These are attributes valued by people [20].

The nurse should also encourage and empower people to be active participants in their health and with the teams for the co-construction of the collaborative care plan centered on the person, with the definition of their objectives, goals, priorities, and purpose of their health and well-being [9, 24], and should promote negotiation [8, 11]. The nurse is expected to strengthen the person’s motivation and commitment to behavior change, which involves partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation, shaping the conversation with the person to evoke and commit the person to behavior change [27] through motivational interviewing [10, 14].

Nurses should help people control their health problems by recognizing them and understanding their role and the importance of communicating and collaborating with people in their health management [10, 13]. The nurse thus assumes the role of a long-term care manager who shares care with the multidisciplinary team in meeting the needs of people with long-term health problems, assuming leadership of these specialized teams for managing people with multiple long-term complex health problems [7, 22].

Primary health care nurses support people in navigating the health care system and services, act as a point of contact as people complete their care plan, link them to an evaluation of their plan, and support self-management [10]. The nurse uses individualized, personalized responses according to the needs of each person with multiple long-term health problems as a strategy [16].

Nurses also use the process of systematic management and follow-up of people with multiple long-term health problems [18] through the definition of individualized/personalized plans, and information about healthy lifestyles [21]. Strengthening communication skills so that nurses place the person at the center of care allows for developing communication pathways and referrals for community support [17, 27].

The nurse also uses health coaching to manage long-term health problems in the community (follow-up/coaching between 12 and 24 months) [25] or uses coaching based on the chronic care model that uses motivational interviewing techniques to empower people [26].

Case management is centered on people with long-term health problems in the community, with an emphasis on education, self-management, and collaboration, so that people can manage their health condition [20] – the responsibility is shared between nurse and person to improve outcomes for health conditions such as diabetes and hypertension [22]. This practice is based on centered, individualized, personalized partnership between the nurse and the person with multiple long-term health problems [8, 9, 23], with the support of multidisciplinary nurse-led community teams [7, 24].

Person-centered practice is fundamental to evidence-based nursing practice, establishing a partnership with the person and respecting their wishes, adapted to their specific needs and preferences [10]. Optimizing the provision of person-centered nursing care involves community-based nursing care; keeping the person with multiple health problems at home favors the prevention of hospital admission as well as shortening the length of hospital stay, if necessary; partnership with people is at the center of care delivery throughout the National Health Service [14].

Comprehensive geriatric assessment can enhance a multidimensional and interdisciplinary diagnostic tool that assesses the person’s health in all its complexity [28]. It is worth mentioning the use of IT tools such as a digital application to support people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, co-created with nurses [12], or the digital application eHealth to support the management of health problems of people with multiple health problems [15] in a personalized care planning based on an information system as a challenge of multimorbidity.

Health literacy should be used as a driver of people’s activation. Activation represents a person’s knowledge, technical capacity, confidence, and motivation to self-manage health and/or disease [13] effectively motivating individual paths and managing essential instruments for the effective activation and management of people’s path through the services they need, through shared decisions throughout the care process and effective communication [11].

The health gains in people with multiple long-term health problems in the community, perceived as positive, were grouped into six major themes: awareness; improved knowledge; better motivation and empowerment; adoption, of healthy enhanced behaviors; improved health status; and improved quality of life [18]. Among these, the first three are identified as intermediate gains, since they contribute to the achievement of the other three, considered as, final gains – the adoption of healthy behaviors; improved health status enhanced quality of life. There are also gains in family members, according to their involvement, changing health behaviors [16].

Nurses provide a set of services that have the potential to produce gains in people with multiple long-term health problems, even without the support of an interdisciplinary team. A nurse makes profit gains when they are present in the multidisciplinary team, as in the control of hemoglobin A1c, fasting glycemia, blood pressure, and cholesterol in people with diabetes [18].

The model of collaborative care between nurses and the person with multiple long-term health problems shows significant gains, allowing 40% of the participants in the control group to recover, allowing the identification of 2.1 more cases of people with mental illness and multiple long-term health problems, also allowing the linking of community members to primary care, increasing awareness of mental health in the community, and reducing the stigma of mental health [19]. It also allows for health gains through identifying and managing the health status of people with mental illness, and other comorbid conditions, by nurses, and a reduction in depressive symptoms through nurse’s value of identification and treatment by the nurse was predictive and positive for both depression and alcohol disorders [17].

Having a collaborative self-management plan was positively associated with adherence to the therapeutic plan, greater knowledge of the disease, increased participation in training and support groups as well as the quality of life; collaboratively, nurse interventions to support patient self-management reduce the need for hospitalization for respiratory cause and improve quality of life [21]. Maintaining the person in a nurse-managed health “coaching” program over time enhances the person’s health goals [17].

Case management increased self-confidence, promoted self-management of long-term health problems, and increased quality of life; having access to nurse case managers who were good communicators was also significant [20, 22, 26] and decreased the use of health care [7, 14, 23]. Co-goal setting and care planning focused on people with multimorbidity and reduced nurses’ workload [8]. It also promotes health status maintenance and improved health status perception by people with multiple long-term health problems as well as decreased rates of depression [20]. It provides greater knowledge and understanding of people and health care professionals and greater involvement of health care professionals and increases personal activation [24]. Motivational conversation predicts changes in desirable behaviors. Motivational previewing also helps identify symptoms to improve symptom and health management [27].

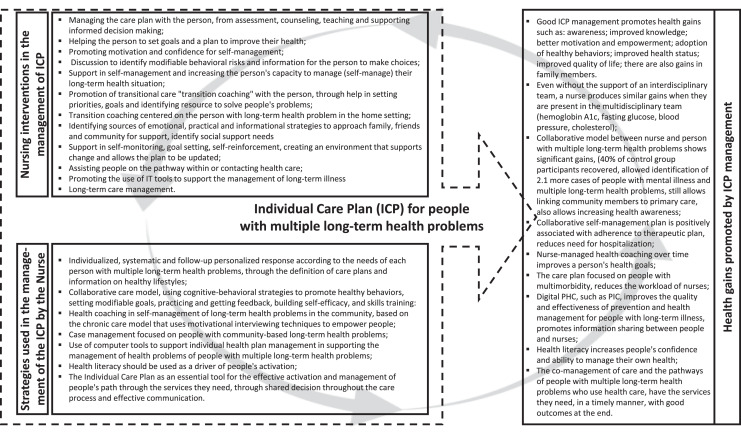

Health literacy increases people’s confidence and ability to manage their health [13]. The co-management of care and the pathways of people with multiple long-term health problems who use health care get the services they need, promptly, with good incomes at the end [11]. Based on the interpretation and synthesis of the evidence identified in the personalized care plannings, the results are summarized in Figure 2, mirroring our understanding of what contributes to the successful implementation of the personalized care planning.

Fig. 2.

Summary of nursing interventions, strategies, and health gains in the good management of personalized care planning.

Limitations of the Study

The comprehensive view of personalized care planning and the multiplicity of forms of organization of health systems at a global level may be a limitation to interpreting results. Future research should include an experimental or quasi-experimental methodology to identify the effectiveness and efficiency of specific nurse interventions in personalized care planning. On the other hand, it will be relevant to describe and identify public health policies and their implementation in practices to evaluate their effectiveness. We can consider as limitations the fact that we included studies in three languages (English, Portuguese, and Spanish) and available in full text, which may have reduced the number of studies with potentially interesting results for our subject.

Contributions to Practice

The systematization of evidence on personalized care planning allows nurses to identify interventions and strategies that produce gains in health and savings in nursing care. The success of personalized care planning in people with multiple long-term health problems needs to be systematically managed and evaluated concerning the health gains of the people involved and the nursing care indicators.

Conclusions

Our objectives were to identify and describe the evidence on managing personalized care planning in people with multiple long-term health problems in the community. We conclude the management of personalized care planning allows for a person-centered intervention by nurses; implementing strategies focused on prevention and health management in people with multiple health problems promotes the empowerment of people for self-management of long-term health problems through assessment, management, counseling, teaching, and support for informed decision-making together with the person. Good management of personalized care planning by the nurse promotes health gains in people with multiple long-term health problems.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

There was no funding for the study.

Author Contributions

The research strategy was defined by both authors; it was carried out by both authors separately on platforms and databases. The two authors independently extracted data. The interpretation was carried out and evaluated by both so that together they present the results with a summary of the main characteristics and objectives. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

There was no funding for the study.

References

- 1. Portugal. Ministério da Saúde. Retrato da saúde 2018. Lisboa: Ministério da Saúde; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Portugal. Ministério da Saúde. SNS+ Proximidade: SNS+ Proximidade: mudança centrada nas pessoas. Lisboa: Ministério da Saúde; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. NHS England . NHS England personalised care & support planning handbook: the journey to person-centred care: core information. London: Coalition for Collaborative Care; 2026. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, Ryan S, Shepperd S, Perera R. Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD010523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barbosa P. Plano individual de cuidados no SNS. In: SNS Jornadas Hospitalares, Lisboa, 27-28 de fevereiro 2018, Escola Superior de Tecnologia da Saúde. Boas práticas em saúde. Lisboa: Administração Central do Sistema de Saúde; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peters M, Marnie C, Tricco A, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunn T, Bliss J, Ryrie I. The impact of community nurse‐led interventions on the need for hospital use among older adults: an integrative review. Int J Older People Nurs. 2021;16(2):e12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Birke H, Jacobsen R, Jønsson ABR, Guassora ADK, Walter M, Saxild T, et al. A complex intervention for multimorbidity in primary care: a feasibility study. J Comorbidity. 2020;10:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Askew DA, Togni S, Egert S, Rogers L, Potter N, Hayman N, et al. Quantitative evaluation of an outreach case management model of care for urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults living with complex chronic disease: a longitudinal study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peart A, Lewis V, Barton C, Russell G. Healthcare professionals providing care coordination to people living with multimorbidity: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(13–14):2317–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sakellarides C. Serviço Nacional de Saúde: dos Desafios da Atualidade às Transformações Necessárias. Acta Med Port. 2020;33(2):133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nyberg A, Tistad M, Wadell K. Can the COPD web be used to promote self-management in patients with COPD in Swedish primary care: a controlled pragmatic pilot trial with 3 month- and 12 month follow-up. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(1):69–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Silva Costa A, Arriaga M, Veloso Mendes R, Miranda D, Barbosa P, Sakellarides C, et al. A strategy for the promotion of health literacy in Portugal, centered around the life-course approach: the importance of digital tools. Port J Public Health. 2019;37(1):50–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Green J, Jester R. Challenges to concordance: theories that explain variations in patient responses. Br J Community Nurs. 2019;24(10):466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lima-Toivanen M, Pereira RM. The contribution of eHealth in closing gaps in primary health care in selected countries of Latin America and the Caribbean. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2018;42:e188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fortin M, Chouinard MC, Diallo BB, Bouhali T. Integration of chronic disease prevention and management services into primary care (PR1MaC): findings from an embedded qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Petersen I, Bhana A, Fairall LR, Selohilwe O, Kathree T, Baron EC, et al. Evaluation of a collaborative care model for integrated primary care of common mental disorders comorbid with chronic conditions in South Africa. BMC Psychiatr. 2019;19(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lukewich J, Edge DS, VanDenKerkhof E, Williamson T, Tranmer J. Team composition and chronic disease management within primary healthcare practices in eastern Ontario: an application of the Measuring Organizational Attributes of Primary Health Care Survey. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018;19(6):622–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Srinivasan K, Mazur A, Mony PK, Whooley M, Ekstrand ML. Improving mental health through integration with primary care in rural Karnataka: study protocol of a cluster randomized control trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Askerud A, Conder J. Patients’ experiences of nurse case management in primary care: a meta-synthesis. Aust J Prim Health. 2017;23(5):420–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Khan A, Dickens AP, Adab P, Jordan RE. Self-management behaviour and support among primary care COPD patients: cross-sectional analysis of data from the Birmingham Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Cohort. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bauer L, Bodenheimer T. Expanded roles of registered nurses in primary care delivery of the future. Nurs Outlook. 2017;65(5):624–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leine M, Wahl AK, Borge CR, Hustavenes M, Bondevik H. Feeling safe and motivated to achieve better health: experiences with a partnership-based nursing practice programme for in-home patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cli Nurs. 2017;26(17–18):2755–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Housden L, Browne AJ, Wong ST, Dawes M. Attending to power differentials: how NP-led group medical visits can influence the management of chronic conditions. Health Expect. 2017;20(5):862–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sharma A, Willard-Grace R, Hessler D, Bodenheimer T, Thom DH. What happens after health coaching? Observational study 1 year following a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(3):200–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kvale E, Huang C-HS, Meneses K, Demark-Wahnefried W, Bae S, Azuero C, et al. Patient-centered support in the survivorship care transition: outcomes from the patient-owned survivorship care plan intervention. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3232–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ostlund A-S, Wadensten B, Häggström E, Lindqvist H, Kristofferzon M-L. Primary care nurses communication and its influence on patient talk during motivational interviewing. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(11):2844–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gálvez-Cano M, Chávez-Jimeno H, Aliaga-Diaz E. Utilidad de la valoración geriátrica integral en la evaluación de la salud del adulto mayor. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Pública. 2016;33(2):321–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]