Since 2012, many states have legalized cannabis use and sales. Public health effects of retail cannabis marketplaces are still emerging, and uncertainty remains about how specific regulations may optimize public safety.1 Partnerships between public health and regulatory agencies are critical, particularly for adverse event monitoring and response.

There are different causes of adverse events. Product quality–related causes of adverse health events, such as contaminated products or mislabeled tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) concentrations, may require immediate regulatory agency action, including product recalls and health alerts. Use-related causes, such as consuming too much or in a risky way, may require sustained actions like public health messaging campaigns to prevent harm.

Cannabis-related policies, such as those regulating product types, packaging, advertising, and licensee operations, can impact both cannabis business practices and cannabis use–related risks. They are a point of intersection for regulatory and public health agency interests.

One example of a shared concern is protecting children from unintentional ingestion of cannabis products. Cannabis edibles can be especially appealing to children when formed as gummies, chocolates, or cookies. Some children who accidentally consume cannabis edibles may have adverse health events that require medical interventions and hospitalization.2 States have addressed this concern through policies such as restricting edible product and packaging colors and images and through public health education like safe storage campaigns for parents of young children.3

POISON CENTER DATA: UNIQUELY VALUABLE FOR MONITORING

Poison center data can be a valuable resource for monitoring cannabis-related adverse events, including unintentional ingestion among children. All 55 US regional poison centers report data in real time to the America’s Poison Centers National Poison Data System (NPDS). Cases range from nontoxic exposures reported by people in their homes to severe toxicity in hospitalized patients reported by health care providers. Information is collected about the exposure situation, symptoms, and a standardized assessment of toxicity effects (e.g., mild, moderate, major). Beginning in 2017, poison centers added specific cannabis product codes (e.g., edibles, vaped products, concentrates). This provides unique information for monitoring adverse health events. Other common data sources such as hospital and emergency department systems use International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes that document cannabis involvement but not product type. Furthermore, emergency department coding and ICD-10-CM coding may significantly undercount cannabis-related visits.4

PUBLIC HEALTH EFFECTS OF CANNABIS EDIBLE PACKAGING POLICY

Here we offer an example of how poison center data on adverse events specifically supports inferences about the relationship between cannabis edible packaging policies and pediatric cannabis edible exposures. We focus on three of the first states to legalize adult-use cannabis: Colorado and Washington legalized in 2012 and started cannabis retail sales in 2014; Oregon legalized in 2014 and started early retail sales in 2015. In 2021 to 2022, prevalence of past-month cannabis use among people aged 12 years and older in these states was similar (19.3% in Colorado, 21.1% in Washington, 21.8% in Oregon).5

Washington and Oregon implemented changes in cannabis edible packaging policies after initial cannabis sales had largely stabilized,6 so changes in patterns of adverse events may be attributed to policy changes rather than introduction of a new market. Colorado serves as a reference group.

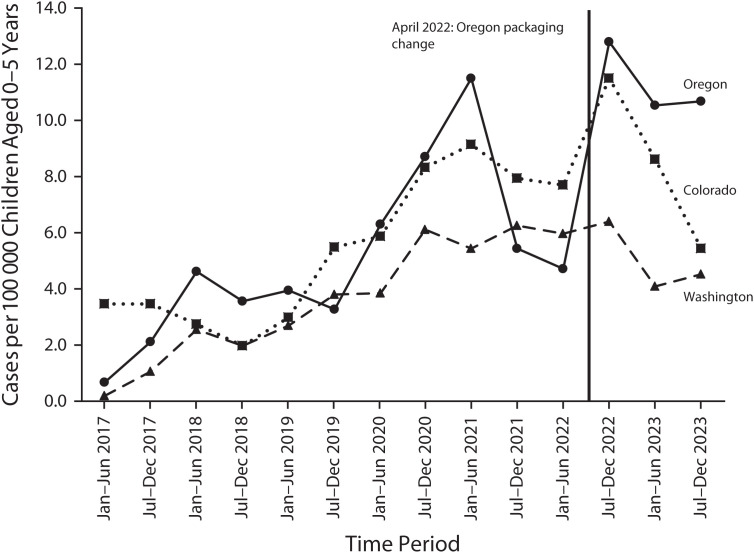

We obtained NPDS data on cannabis exposures reported to the states’ regional poison centers. Figure 1 shows state-level semiannual rates (January– June and July–December) of cannabis edible exposures among children aged 0 to 5 years, where the child exposed had at least minor health effects (i.e., excluding cases with no health effects).

FIGURE 1—

Cannabis Edible–Related Exposures Among Children Aged 0–5 Years: Colorado, Washington, and Oregon; America’s Poison Centers National Poison Data System (NPDS); 2017–2023

Note. Cases were defined as cannabis edible exposure (NPDS generic code 0310121) with final outcome classified as “minor” (e.g., vomiting or transient altered mental status or somnolence), “moderate” (e.g., obtundation, mild hypotension, or a single seizure), or “major” (e.g., respiratory depression, need for intubation and mechanical ventilation, or multiple seizures). Washington required single-unit packaging for edibles starting in February 2017. Oregon increased allowed tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in edibles starting April 2022. Additionally, Colorado restricted edible THC allowances from 200 mg to 100 mg per package in early 2018, potentially coinciding with the reduced number of cases.

Beginning in early 2017, Washington required all edible servings within packages (up to 10 servings at up to 10 mg THC) to be individually wrapped, with a “not for kids” package warning label containing the poison center phone number.7 This policy change was made in response to concerns about reports of accidental poisoning among young children; single-unit packaging is a proven method to reduce medication poisonings among children, creating barriers for child access and giving parents time to intervene.8 Figure 1 shows that Washington’s annual rate of child poisonings has increased over time, but to a lesser degree than in other states without single-unit packaging, including during the 2020 pandemic. Notably, Canada has a national policy that limits per-package THC to the same 10 milligrams that Washington allows per serving, and Canadian pediatric exposure rates were similar to Washington’s in 2021.9 This suggests that single-unit packaging may be an effective way to reduce child exposures.

By contrast, following the passage of a legislative proposal requested by industry representatives, Oregon increased the amount of THC allowed in cannabis edible packaging in April 2022 from 50 milligrams (10 servings at up to 5 mg each) to 100 milligrams (10 servings at up to 10 mg each), matching Washington’s and Colorado’s limits.10 This means the potential amount of THC that could be ingested by a child was doubled. Oregon retail products quickly reflected the rule change: the average THC in edibles sold was 47 milligrams in April 2021, 74 milligrams in April 2022, and 93 milligrams in April 2023 (Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission agency communication, May 9, 2024). Figure 1 shows that Oregon’s annual rate of child poisonings was historically close to Colorado’s and decreased in 2021 (potentially related to a state “safe storage” campaign). However, following Oregon’s mid-2022 edible policy change, rates of child poisonings increased substantially while Colorado’s and Washington’s were stable or decreased. Oregon’s cases have consistently had worse outcomes: in 2023, more than half of cases were classified as having moderate or major health effects, compared to less than 30% in Colorado and Washington. Although further investigation is warranted, this finding suggests that policies increasing potential THC exposure amounts could be associated with greater rates of adverse events among young children.

PUBLIC HEALTH EFFECTS AS CANNABIS POLICIES EVOLVE

Many states’ cannabis policies have changed over the past 10 years, and US federal policies are currently under debate. Our example involving an edible packaging change suggests that the period around policy change may be an especially critical time for public safety-centered partnerships.

Agencies should prepare to play important roles in monitoring and mitigating adverse events. For example, state public health agencies can help to connect regulators with data, including from partners such as regional poison centers, for assessment and evaluation; Colorado has established dashboards for public-facing tracking of adverse events reported to the state’s regional poison center and from other data sources.11 Local health departments can bring the perspectives of diverse communities and apply community-specific policies and education efforts. Regulatory agencies can establish systems like online or telephone hotlines for consumers to report problems from specific products that might need investigation, and then document responses. For example, the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission (OLCC) created a product recalls alert webpage to communicate about active public safety concerns.12 Notably, some regulatory agencies, including the OLCC and Washington’s Liquor and Cannabis Board, have established public health-focused positions within their agencies to routinely integrate health considerations with operations and strengthen coordination with public health systems.

Public health lenses need to be included systematically in ongoing cannabis regulatory design, oversight, and continuous improvement. Identifying best practices and policies for preventing adverse events will be possible when resources are committed not only to monitoring and response, but also to evaluation, application, and sharing of findings on the outcomes of any changes in policy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J. A. Dilley and E. M. Everson were supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (award 1R01DA039293, PI: J. A. D.).

The authors would like to thank partners from the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission (OLCC), as well as Richard Holdman and Wenhua Ren from Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, for providing data and review of this paper.

Note. The opinions in this editorial are those of the authors entirely and do not necessarily represent those of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or other agencies.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perlman AI, McLeod HM, Ventresca EC, et al. Medical cannabis state and federal regulations: implications for United States health care entities. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(10):2671–2681. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin A, O’Connor M, Behnam R, Hatef C, Milanaik R. Edible marijuana products and potential risks for pediatric populations. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2022;34(3):279–287. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000001132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Network for Public Health Law. THC limits for adult-use cannabis products. Available at: https://www.networkforphl.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/THC-limits-for-Adult-Use-Cannabis-Products.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2024.

- 4.Hendrickson RG, Dilley JA, Hedberg K, et al. The burden of cannabis-attributed pediatric and adult emergency department visits. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(12):1444–1447. 10.1111/acem.14275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National survey on drug use and health (NSDUH) interactive NSDUH state estimates . Available at: https://datatools.samhsa.gov/saes/state . Accessed June 11, 2024. .

- 6.Dilley JA, Johnson JK, Colby AM, Sheehy TJ, Muse EJ, Filley JR, Segawa MB, Schauer GL, Kilmer B. Cannabis retail market indicators in five legal states in the US: a public health perspective. Clinical Therapeutics. 2023;S0149-2918(23):00221-7. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2023.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Washington Poison Center . Not for kids. February 14, 2017. . Available at: https://www.wapc.org/programs/services/not-for-kids . Accessed May 10, 2024.

- 8.Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Geller RJ. Prevention of unintentional medication overdose among children. JAMA. 2020;324(6):550–551. 10.1001/jama.2020.2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myran DT, Tanuseputro P, Auger N, Konikoff L, Talarico R, Finkelstein Y. Edible cannabis legalization and unintentional poisonings in children. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(8):757–759. 10.1056/NEJMc2207661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oregon State Legislative Assembly . Senate bill 408, chapter 397. Effective June 23, 2021. . Available at: https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2021R1/Measures/Overview/SB408 . Accessed May 10, 2024.

- 11.Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Health data: Marijuana use/consumption. Available at: https://marijuanahealthreport.colorado.gov/health-data. Accessed May 10, 2024.

- 12. Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission. product recall notices . Available at: https://www.oregon.gov/olcc/Pages/product-recalls.aspx . Accessed May 10, 2024. .