Abstract

Objective

To determine whether a chemokine receptor type 2 antagonist, DMX-200 (repagermanium), in combination with an angiotensin receptor blocker, candesartan, improves clinical outcomes in people with COVID-19.

Design

Prospective, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting

Ten acute care hospitals in India.

Participants

Adults <65 years old intended for hospital admission with moderate/severe COVID-19 disease (respiratory rate ≥24 breaths per minute or oxygen saturation ≤93% on room air).

Intervention

DMX-200 120 mg two times per day, or placebo, on background of titratable candesartan commencing at 4 mg two times per day, for 28 days.

Main outcome measures

The primary endpoint was COVID-19 disease severity on a modified WHO Clinical Progression Scale (WHO scale) on day 14. Secondary outcomes included the WHO scale at days 28, 60, 90 and 180; intensive care unit (ICU) admission, respiratory failure or death within 28 days; length of hospitalisation; and requirement for ventilatory support or dialysis.

Results

Between December 2021 and August 2022, 518 people were screened, with 49 randomised to DMX-200 or placebo on a background of candesartan. The study was terminated early due to recruitment barriers, including an external requirement to restrict enrolment to adults <65 years old, contributing to a 91% screen failure rate. The median WHO Clinical Progression Scale (WHO scale) score at day 14 for both groups was 1 (IQR 1–1), indicating most participants were discharged with no limitations on activities by this time. Formal comparison was not performed due to the small sample size. One participant receiving DMX-200 died of COVID-19 disease progression. No participants required ICU admission, ventilation or dialysis. Median length of hospitalisation in both groups was 6 days (IQR 6–7 days). WHO scale scores were similar at 28, 60, 90 and 180 days.

Conclusion

Due to recruitment barriers, the study was unable to determine whether DMX-200 improves clinical outcomes in people with COVID-19.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05122182.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 infection, randomized controlled trial

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Interventions with biological plausibility to synergistically reduce lung inflammation in SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A bespoke algorithm for the safe titration of angiotensin receptor blockers in a clinical trial setting.

Discussion of barriers to recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic, including external restrictions on eligibility criteria and various pandemic-related delays affecting processes and materials, which may help inform preparation for future pandemics.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to catastrophic suffering and death, driving a need for new therapies to reduce disease severity. The primary cause of death from COVID-19 has been life-threatening pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).1 While there may be multiple mechanisms by which COVID-19 induces ARDS, the observation of elevated levels of proinflammatory messenger molecules (cytokines) in people with severe COVID-19 suggests contribution from a hyperinflammatory immune response.2 A key proinflammatory cytokine is monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1, also known as C-C motif chemokine ligand 2).2 In an observational study of 41 people with COVID-19, inpatients had higher concentrations of MCP-1 than those managed as outpatients, while the highest concentrations were observed in people admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).2 Additionally, other studies have suggested a pathological role of MCP-1 in viral lung disease and ventilator-associated pneumonia.3 4 MCP-1 mediates inflammation of tissues such as the lung by recruiting and activating the white blood cells known as monocytes, through interacting with the chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) on monocyte cell surfaces.3 This interaction can be opposed by DMX-200, a CCR2 antagonist also known as repagermanium. The potential role of CCR2 antagonism in reducing the severity of COVID-19, through the expected reduction in lung inflammation, has not been previously investigated.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS), which is a hormone system primarily known for its role in regulating blood pressure, fluids and electrolytes, also plays a crucial role in COVID-19 pathophysiology. The virus responsible for COVID-19, known as SARS-CoV-2, penetrates target cells by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is a component of the RAS system.5,7 By binding to the ACE2 receptor, the virus is able to pass into the cell through a process called endocytosis.5,7 Once inside the cell, the virus is able to replicate.8 In addition to facilitating viral entry, this endocytosis process may cause further complications by depleting the cell surface of the ACE2 receptors, which ordinarily serve an additional role in mediating an anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic cellular pathway.9 This pathway usually counterbalances a proinflammatory RAS pathway mediated through the angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor.9 The medications known as angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), which inhibit many effects of the RAS system and are commonly used in the management of high blood pressure, may help reduce the RAS-driven inflammatory response.9 For example, the ARB losartan was seen to reduce lung injury in an animal model of SARS-CoV, a related novel coronavirus that pre-dated SARS-CoV-2.9

Importantly, cellular and animal models suggest a functional interaction at the cell surface between CCR2 and the AT1 receptor,10 11 raising the possibility that joint CCR2 and AT1 antagonism could provide synergistic benefits in downregulating inflammatory pathways and improving patient outcomes.

The following study aimed to explore whether DMX-200, compared with placebo, improves COVID-19 severity among people hospitalised with the disease, on a background of ARB therapy. Subsequent phases, which are no longer proceeding, were planned to compare DMX+ARB dual therapy with ARB+placebo (Pbo), or a double placebo.

Methods

The reporting of the study methods below is consistent with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) and the CONSORT and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials Extension for RCTs Revised in Extenuating Circumstances (CONSERVE); the respective checklists are included as onlinesupplemental files 1 2.

Study design

Controlled evaLuation of Angiotensin Receptor blockers for COVID-19 respIraTorY disease 2.0 (CLARITY 2.0) was a prospective, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The initial phase II safety stage presented here was a requirement of local regulatory authorities, involving a planned 80 participants randomised to combination DMX-200+ARB or Pbo+ARB, with narrowed inclusion criteria as outlined below.

The plan, after recruitment was complete and following review of the safety data, was to proceed to a three-arm study of 600 participants to compare DMX-200+ARB with ARB+Pbo or double placebo. This stage was to be followed by a full-phase III study comparing DMX-200+ARB with the more successful comparator of ARB+Pbo or double placebo. An adaptive sample size calculation was to be performed including participants from all stages, to reach final participant numbers powered to definitively assess whether a treatment effect was present for the most successful treatment arm. The study protocol is available as an online supplemental file 3.

Participants

The study recruited participants from 10 hospital sites in India. All sites were tertiary hospitals able to provide comprehensive COVID-19 care, with full access to antiviral medications, oxygen, non-invasive ventilation and ICU care. Participants were aged 18 to <65 years old with a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection via reverse transcription PCR within the previous 10 days, with planned hospital admission for the management of moderate or severe COVID-19 infection. Moderate infection was defined as a respiratory rate of ≥24 breaths per minute or oxygen saturation of 90–93% on room air; severe infection was defined as a respiratory rate ≥30 breaths per minute or oxygen saturation of <90% on room air. The age and severity eligibility criteria were required by the responsible regulatory authority (Drug Controller General of India) to gain further information about the safety profile of DMX-200 before allowing expansion to a broader population in subsequent study stages.

Participants were required to have a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of ≥120 mm Hg, or SBP ≥115 mm Hg if receiving a non-RAS blood pressure-lowering agent which could be ceased. Exclusion criteria included current treatment with an ACE inhibitor (ACEi); an ARB or aldosterone antagonist, aliskiren or angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors; serum potassium >5.5 mmol/L; an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1.73m2; known biliary obstruction; known severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh-Turcotte score 10–15); or known viral hepatitis. All participants provided written or verbal informed consent.

Randomisation and masking

In this first stage of the planned research, study participants were randomised (1:1) to DMX-200 or placebo in a blinded process using the cohort design of the Medidata Randomisation and Trial Supply Management module (V.2021.1.0), with randomly permuted blocks of sizes two and four with stratification by site. Study participants and the clinical and research teams were blinded to treatment allocation. The placebo group received matched placebo identical in appearance and packaging to DMX-200. All participants were treated with open-label candesartan.

Procedures

Participants received either DMX-200 120 mg immediate-release capsule two times per day or a matched placebo, for 28 days. All participants received candesartan, an ARB, at an initial dose of 4 mg two times per day. The candesartan dose was reviewed at least daily and titrated to maximum tolerated up to 32 mg daily according to an algorithm based on blood pressure, potassium levels and eGFR changes (online supplemental figure S1, file 4). All other clinical care was provided according to local site practices.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was COVID-19 disease severity on a modified WHO scale on day 14. Secondary outcomes were the WHO scale at days 28, 60, 90 and 180; acute kidney injury, ICU admission, respiratory failure or death within 28 days; time to death; length of hospital or ICU admission; and requirement for ventilatory support or dialysis. Safety outcomes of interest included hypotension and hyperkalaemia, which are established risks of ARB use12 and deranged liver function tests, which may be associated with DMX-200 use.13

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis plan specified a Bayesian approach to evaluate the primary and secondary outcomes. The sample size for the initial 80 participant safety stage was determined by the Indian regulators as a pragmatic balance between conservative safety monitoring and streamlining the transition to less restrictive recruitment. If the study had continued, a review of safety and efficacy data was planned after 600 recruited participants to inform sample size re-estimation and comparator selection for the subsequent stage, through a Bayesian approach. All inferences were to be based on summaries from the joint posterior distribution of the model parameters, and all analyses were to be on an intention-to-treat basis. A statistical analysis plan is provided in the online supplemental file 5.

Given that the trial was terminated early with a small sample size and nearly all participants had recovered by day 14, a descriptive summary of the results is presented. A post-hoc analysis of oxygen-free status as a post-hoc exploratory outcome was undertaken.

Patient and public involvement

A consumer and community engagement committee assisted the trial steering committee, providing advice and feedback on trial aims and participant-facing materials.

Results

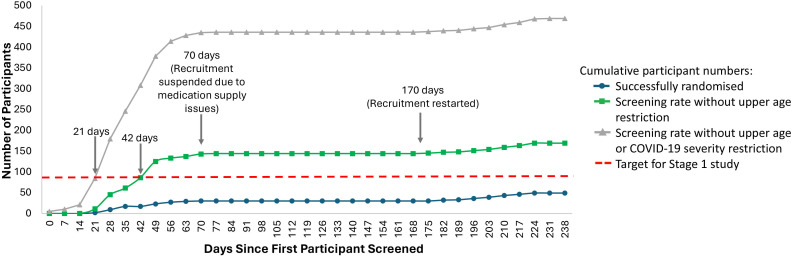

Between 21 December 2021 and 17 August 2022, 518 people were screened for eligibility, with 25 randomly assigned to DMX-200 and 25 to the placebo group (online supplemental figure S2). There was a 91% screen failure rate with the most common cause being age greater than the externally mandated age restriction of <65 years old. As a result of the recruitment challenges, the study was terminated after 50 participants were enrolled. The recruitment progress demonstrated the study would have likely completed the stage 1 target of 80 participants within 21 days of opening in the absence of the age and severity restrictions (figure 1). One participant was withdrawn from the placebo arm without receiving treatment after an error in screening, due to a negative result on a repeated SARS-CoV-2 test. Follow-up was complete for the remaining 49 participants.

Figure 1. Impact of external eligibility restrictions on recruitment rate for CLARITY 2.0 study participants. CLARITY 2.0, Controlled evaLuation of Angiotensin Receptor blockers for COVID-19 respIraTorY disease 2.0.

Within the limits of the small sample size, there were no major differences in baseline characteristics between the two arms (table 1). Overall, 92% of participants had received at least one COVID-19 vaccination.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of CLARITY 2.0 study participants.

| Variable | DMX-200 and candesartann=25 | Placebo and candesartann=24 | Totaln=49 |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 37.0 (33.0, 42.0) | 34.5 (30.8, 46.0) | 37.0 (32.0, 46.0) |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 9 (36) | 8 (33) | 17 (35) |

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) | 70.0 (62.0, 72.0) | 69.5 (63.0, 74.0) | 70.0 (62.0, 74.0) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| South Asian, n (%) | 25 (100) | 24 (100) | 49 (100) |

| Height (cm), median (IQR) | 164 (160, 168) | 164 (158, 169) | 164 (158, 169) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Current smoker | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Never smoked | 21 (84) | 22 (92) | 43 (88) |

| Previous smoker | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 5 (10) |

| Received at least one COVID-19 vaccination dose, n (%) | 24 (96) | 21 (88) | 45 (92) |

| Number of COVID-19 vaccination doses received, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 1 (4) | 3 (12) | 4 (8) |

| 1 | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 3 (6) |

| 2 | 23 (92) | 19 (79) | 42 (86) |

| COVID-19 vaccine brand*, n (%) | |||

| Covaxin (Bharat Biotech) | 9 (36) | 10 (42) | 19 (39) |

| Covishield (AstraZeneca) | 15 (60) | 11 (46) | 26 (53) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Chronic respiratory illness, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cancer (last 5 years), n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 5 (20) | 2 (8) | 7 (14) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 3 (6) |

| Severe liver disease, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Missing values for COVID-19 vaccine brand.

CLARITY 2.0Controlled evaLuation of Angiotensin Receptor blockers for COVID-19 respIraTorY disease 2.0

Candesartan was initiated in all participants at 4 mg two times per day in accordance with the protocol. Minimal dose adjustments were made and all were in accordance with the candesartan titration regimen.

For DMX-200/placebo dosing, one participant receiving DMX-200 had swallowing difficulty and ceased therapy after 3 days. One participant receiving placebo declined further study medication after 2 days of therapy but consented to ongoing follow-up. Both were included in their respective groups according to the intention-to-treat principle. Overall, mean adherence to prescribed therapy was 96% for DMX-200 doses and 95% for placebo doses.

The study was terminated early due to recruitment barriers, including the regulatory requirement to limit enrolment for the first 80 participants to adults <65 years old with moderate or severe COVID-19. There were also various pandemic-related delays affecting implementation processes and materials.

For the primary outcome of the WHO scale on day 14, the median score was 1 among 25 participants assigned to DMX-200 (IQR 1–1) and 1 among 24 participants assigned to placebo (IQR 1–1) (table 2), indicating that the majority of participants were not hospitalised and had no limitations on activities at this time point. A statistical comparison was not performed due to the small sample size.

Table 2. Modified WHO Clinical Progression Scale (WHO scale) scores at days 14 and 28 in people with COVID-19 randomised to DMX-200, or placebo, on a background of candesartan therapy.

| WHO scale score | Statistic | At day 14 | At day 28 | ||||

| DMX-200 n=25 | Placebon=25 | Totaln=49 | DMX-200 n=25 | Placebon=25 | Totaln=49 | ||

| Not hospitalised, no limitations on activities | n (%) | 23 (92) | 22 (92) | 45 (92) | 24 (96) | 23 (96) | 47 (96) |

| Not hospitalised, limitation on activities | n (%) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hospitalised, not requiring supplemental oxygen | n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hospitalised, requiring supplemental oxygen by mask or nasal prongs | n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hospitalised, on non-invasive ventilation or high-flow oxygen devices | n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Hospitalised, requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation | n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hospitalised, on invasive mechanical ventilation and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Death | n (%) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

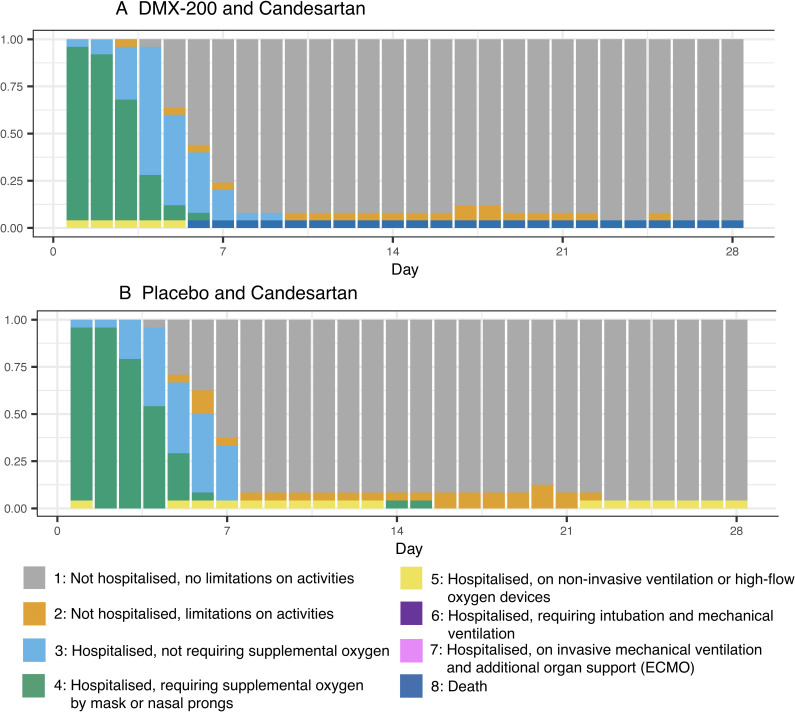

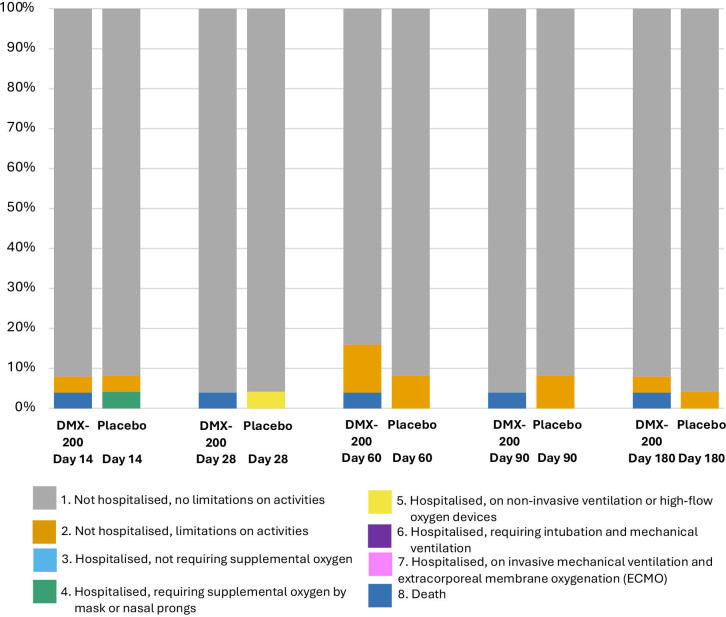

There were no clear between-group differences in WHO scale outcomes on days 28, 60, 90 or 180 (table 2, figures2A,B 3; online supplemental table S2, file 4). By day 180, a total of 47 participants had no limitation on activities and were not hospitalised (WHO scale of 1). One participant randomised to the DMX-200 arm died of COVID-19 disease progression, with no deaths in the placebo arm. By day 180, one participant in each group had a WHO scale of 2, indicating some limitations on activities but no current hospitalisation.

Figure 2. Modified WHO Clinical Progression Scale scores from day 0 to day 28 in people with COVID-19 randomised to (A) DMX-200 and candesartan and (B) Placebo and candesartan.

Figure 3. Modified WHO Clinical Progression Scale scores at days 14, 28, 60, 90 and 180 in people with COVID-19 randomised to DMX-200, or placebo, on a background of candesartan therapy.

The median length of hospital stay was 6 days in both groups (IQR 6–7 days). The median time to oxygen-free status was 4 days (95% credible interval (CrI) 4 to 6) in the DMX-200 group and 5 days (95% CrI 4 to 6) in the placebo group.

No participants required ICU admission, vasopressor support, ventilation or dialysis. There was one acute kidney injury event in a participant receiving placebo.

10 participants experienced an abnormal aspartate transaminase level (6 with DMX-200 and 4 with placebo), and 19 participants experienced an abnormal alanine transaminase level (8 with DMX-200 and 11 with placebo). With the exception of the single death, no other serious adverse events were recorded. The frequency of adverse events is listed in online supplemental table S1.

Discussion

The study recruited people aged 18 to <65 who were admitted to the hospital for moderate or severe COVID-19 and randomly assigned treatment to the CCR2 antagonist DMX-200 or placebo, for 28 days, on a background of candesartan. The trial was terminated early due to slow recruitment secondary to externally applied restrictions to trial eligibility criteria and pandemic-related delays affecting processes and materials. Due to the small sample size, it was not possible to assess the primary outcome of the difference in WHO scale at day 14. The majority of participants were discharged within 1 week; none required ICU admission, ventilation or dialysis; and there was no excess liver toxicity. One participant in the DMX-200 group died due to COVID-19 disease progression. The treatments were well tolerated. All participants safely received candesartan according to an algorithm titrated to blood pressure, eGFR and potassium. The algorithm appeared safe and could be considered for use in other trials, although the patient cohort was relatively stable and little titration was required.

The study encountered numerous logistical challenges, many of which were related to the pandemic such as delays in approval procedures, unpredictable disease onset frequencies in different regions and placebo supply chain issues. The chief barrier was the regulatory requirement of an initial safety stage with upper age limit and severity criteria, which was not anticipated at the time of the initial study design. The inclusion restrictions did not reflect the patient population being admitted for COVID-19 management and led to a 91% screen failure rate and severely limited recruitment. There were plans to open Australian and Malaysian study sites to compensate, but commencement in these locations was significantly delayed due to placebo supply chain issues. The success of large, pragmatic trials such as the RECOVERY14 and CLARITY15 trials shows the strength of embedding research in clinical systems to allow streamlined approval processes, rapid recruitment and early delivery of practice-changing results.

The question of the role of CCR2 antagonism in COVID-19 infection remains unanswered. There is sound biological plausibility of an effect; the levels of the ligand MCP-1 are markedly higher among those with severe COVID-19 disease,16 and the MCP-1/CCR2 axis strongly promotes macrophage infiltration into areas of active inflammation, which can contribute to tissue injury.17 The combination with RAAS blockade is of particular interest given the observed functional interaction between CCR2 receptors and the AT1 receptor in the RAS system, given that the RAAS system is itself involved in proinflammatory pathways,10 including in coronavirus infections.9 Phase I and II trials of DMX-200 have also demonstrated a good safety profile, including in combination with ARBs.18 Additionally, an alternative crystal formulation known as propagermanium has been used in Japan as a treatment for chronic hepatitis B since the 1980s and is generally well tolerated, although with increased rates of liver function derangement in this at-risk population.13

The role of RAS inhibition in COVID-19 management has been explored in two other recently published large trials and a number of other trials yet to be published. In the CLARITY study, 787 participants with predominantly mild disease received an ARB or placebo on hospital admission for COVID-19 and continued for 28 days.15 No benefit based on disease severity score was demonstrated. In the Randomised Embedded Multifactorial Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia trial, an ACE2 RAS modulation domain randomised participants hospitalised with COVID-19 to receive ACEi (n=257), ARB (n=248) or no ACEi or ARB (n=264) for 10 days or until discharge.19 In this population of patients who were predominantly critically ill, Bayesian analysis demonstrated a 95% posterior probability that ACEi or ARB worsened days free of organ support in this population, with a similar probability of worsening hospital survival. The ACE2 RAS modulation domain was subsequently closed due to lack of efficacy for ACEi and ARB. At the time of closure of the domain, 10 participants had also been randomised to combination DMX-200+ARB, with 6 of these having reached the primary outcome assessment point. Formal analysis was not performed.

The strengths of the present study included the use of patient-important outcomes to assess benefits, high levels of medication adherence and complete follow-up data. The chief limitation of the study was the restrictive inclusion criteria, leading to a small sample size that precluded meaningful evaluation of the study outcomes. The use of the WHO score at 14 days was a common metric of disease treatment at the time of the trial design, including in the CLARITY 1.0 trial,15 but may not have reflected the improvements in the natural history of COVID-19 over the trial period, likely related to uptake of vaccination and other therapies. This evolution could have reduced the ability of this metric to demonstrate an improvement 14 days after randomisation. If the study had continued, the primary outcome would not have been assessed until the completion of the 600 participant stage, creating an opportunity for a blinded decision to use WHO scores data from earlier in the treatment period to better capture the acute effects of the intervention. WHO score data were collected daily in the first 2 weeks for all participants, which would have enabled selection of a different time point in this period. The inclusion of participants with COVID-19 diagnosed up to 10 days prior to randomisation may also reduce the ability to detect an acute treatment effect, although equivalent or longer windows were used in other COVID-19 studies.15 19 Finally, the initial dosing of candesartan at 4 mg two times per day may have been insufficient to obtain sufficient AT1 receptor blockade, although our algorithm was designed to safely maximise dose in the individual participants according to tolerance.

To further explore the role of concomitant CCR2 antagonism and ARB therapy in COVID-19 management, future studies would need to have broader inclusion criteria, in particular including participants at higher risk of severe disease, such as those above 65 years old. This would require consideration of sites which do not have externally mandated recruitment restrictions. Developing system contingencies for placebo supply, other clinical trial materials and clinical trial processes would also help to protect against the unpredictability of trial development amidst a pandemic. The synergistic role of these treatments may also have applications outside of coronavirus infections which warrant further investigation; a phase III study of dual therapy in patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis is currently underway (NCT05183646).

Conclusions

Due to recruitment barriers leading to early termination, the study was unable to determine whether combination therapy of a CCR2 antagonist, DMX-200, and an ARB, candesartan, improves clinical outcomes in moderate to severe COVID-19 compared with neither treatment nor treatment with ARB alone. The study contributes some further safety information on the use of DMX-200 in hospitalised patients.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Footnotes

Funding: The study received financial support from Dimerix Bioscience Pty Ltd. DVO receives support through an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, the Royal Australian Society of Nephrology Jacquot Research Entry Scholarship and the NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre Postgraduate Research Scholarship.

Prepub: Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-081790).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by ethical approval. The protocol was approved by the Sydney Local Health District Ethics Review Committee (Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Zone) in Australia (X21-0391 & 2021/ETH11815, 21 December 2021) and by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation in India (GCT/CT04/FF/2021/24227 [GCT/27/21], 28 September 2021) as well as through the George Institute in India (Project Number 01/2021, 5 March 2021). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Data availability free text: Requests for deidentified individual patients or aggregate data should be directed to the corresponding author and will be reviewed and adjudicated by the steering committee. The study protocol is available as Supplemental File 3.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Collaborators: Steering Committee: Arlen Wilcox, Abhinav Bassi, Carol Pollock, Cheryl Jones, Greg J Fox, Louise M Burrell, Meg J Jardine, Sanjay D'Cruz, Sharifah Faridah Syed Omar, Thomas L Snelling, Vinay Rathore, Vivekanand Jha. Central Coordinating Committee: Meg J Jardine, Vivekanand Jha, Abhinav Bassi, Arlen Wilcox, Thomas L Snelling, Mark Jones, James Totterdell, Nikita Bathla, Katrina Diamante, Gerard Estivill Mercade, Rui Xie, Aishwarya Nair, Annelise Decaria, Nicola Abignano, Vinay Rathore, Atul Jindal, Sabah Siddiqui, Suprava Patel, Anjulata Sahu, Ashpak Bangi, Yasmeen Shaikh, Manish Kumar Jain, Madhavender Jain, Kapil Soni, Shivam R Kanje, Sanjeev Kumar Vimal, K. Kalyan Chakravarthy, P. Sathish Babu, Sanjay D’Cruz, Yuvraj Singh Cheema, Merlin Moni, Sivapriya G Nair, Sradha Kotwal. Drug Safety Monitoring Board: Richard Haynes, Gagandeep Kang, Guy Thwaites, Natalie Staplin, Stephane Heritier.

Contributor Information

Daniel Vincent O'Hara, Email: daniel.ohara@sydney.edu.au.

Abhinav Bassi, Email: abassi@georgeinstitute.org.in.

Arlen Wilcox, Email: arlen.wilcox@sydney.edu.au.

Vivekanand Jha, Email: vjha60@gmail.com.

Vinay Rathore, Email: vinayrathoremd@gmail.com.

Sanjay D'Cruz, Email: sanjaydcruz@gmail.com.

Thomas L Snelling, Email: tom.snelling@sydney.edu.au.

Mark Jones, Email: mark.jones1@sydney.edu.au.

James Totterdell, Email: james.totterdell@sydney.edu.au.

Ashpak Bangi, Email: ashfak0077@yahoo.co.in.

Manish Kumar Jain, Email: doctormanishjain2@gmail.com.

Carol Pollock, Email: carol.pollock@sydney.edu.au.

Louise Burrell, Email: l.burrell@unimelb.edu.au.

Gregory Fox, Email: gregory.fox@sydney.edu.au.

Cheryl Jones, Email: cheryl.jones@sydney.edu.au.

Sradha Kotwal, Email: skotwal@georgeinstitute.org.au.

Sharifah Faridah Syed Omar, Email: sfaridah@ummc.edu.my.

Meg Jardine, Email: meg.jardine@sydney.edu.au.

on behalf of the CLARITY 2.0 trial investigators:

Nikita Bathla, Katrina Diamante, Gerard Estivill Mercade, Rui Xie, Aishwarya Nair, Annelise Decaria, Nicola Abignano, Atul Jindal, Sabah Siddiqui, Suprava Patel, Anjulata Sahu, Yasmeen Shaikh, Madhavender Jain, Kapil Soni, Shivam R Kanje, Sanjeev Kumar Vimal, K. Kalyan Chakravarthy, P. Sathish Babu, Yuvraj Singh Cheema, Merlin Moni, Sivapriya G Nair, Richard Haynes, Gagandeep Kang, Guy Thwaites, Natalie Staplin, and Stephane Heritier

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li YT, Wang YC, Lee HL, et al. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1, a Possible Biomarker of Multiorgan Failure and Mortality in Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2218. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong CK, Lam CWK, Wu AKL, et al. Plasma inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature New Biol. 2020;581:215–20. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeung ML, Teng JLL, Jia L, et al. Soluble ACE2-mediated cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 via interaction with proteins related to the renin-angiotensin system. Cell. 2021;184:2212–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.V’kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, et al. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:155–70. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11:875–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayoub MA, Zhang Y, Kelly RS, et al. Functional interaction between angiotensin II receptor type 1 and chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 with implications for chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan DP, Coy JW, Chahal KK, et al. The Angiotensin Receptor Blocker Losartan Suppresses Growth of Pulmonary Metastases via AT1R-Independent Inhibition of CCR2 Signaling and Monocyte Recruitment. J Immunol. 2019;202:3087–102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham HMA, White CM, White WB. The comparative efficacy and safety of the angiotensin receptor blockers in the management of hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases. Drug Saf. 2015;38:33–54. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0239-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirayama C, Suzuki H, Ito M, et al. Propagermanium: a nonspecific immune modulator for chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:525–32. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jardine MJ, Kotwal SS, Bassi A, et al. Angiotensin receptor blockers for the treatment of covid-19: pragmatic, adaptive, multicentre, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2022;379:e072175. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Wang J, Liu C, et al. IP-10 and MCP-1 as biomarkers associated with disease severity of COVID-19. Mol Med. 2020;26:97. doi: 10.1186/s10020-020-00230-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:313–26. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimerix reports positive phase 2 study results of DMX-200 in diabetic kidney disease [press release] 2020.

- 19.Lawler PR, Derde LPG, van de Veerdonk FL, et al. Effect of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor and Angiotensin Receptor Blocker Initiation on Organ Support-Free Days in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;329:1183–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.4480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.