Abstract

Corin is a protease that activates atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), a hormone in cardiovascular homeostasis. Structurally, ANP is similar to C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) crucial in bone development. Here, we examine the role of corin and ANP in chondrocyte differentiation and bone formation. We show that in Corin and Nppa (encoding ANP) knockout (KO) mice, chondrocyte differentiation is impaired, resulting in shortened limb long bones. In adult mice, Corin and Nppa deficiency impairs bone density and microarchitecture. Molecular studies in cartilages from newborn Corin and Nppa KO mice and in cultured chondrocytes indicate that corin and ANP act in chondrocytes via cGMP-dependent protein kinase G signaling to inhibit mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation and stimulate glycogen synthase kinase-3β phosphorylation and β-catenin upregulation. These results indicate that corin and ANP signaling regulates chondrocyte differentiation in bone development and homeostasis, suggesting that enhancing ANP signaling may improve bone quality in patients with osteoporosis.

Subject terms: Bone development, Bone

Studies in knockout mice and cultured chondrocytes indicate an important role of corin and atrial natriuretic peptide-mediated signaling in endochondral ossification and bone development.

Introduction

Endochondral ossification is a critical process in bone development, particularly in long bones, vertebrae, and craniofacial fragments1–3. During this process, mesenchymal stem cell-derived chondrocytes undergo a series of morphological and functional changes. In the growth plate of long bones, for example, resting chondrocytes are stimulated to become proliferative chondrocytes that form longitudinal cell columns. The proliferative chondrocytes are further transformed into hypertrophic chondrocytes that subsequently undergo apoptosis, which is followed by vascular invasion, matrix and mineral deposition, and osteogenesis. The sequential transformation in the chondrocytes is regulated by many factors, such as transcription factors, growth hormones, proteolytic enzymes, and signaling molecules1–6.

Natriuretic peptides are a group of structurally related hormones7,8. In mammals, there are three natriuretic peptides, i.e., atrial, B-type, and C-type natriuretic peptides (ANP, BNP, and CNP, respectively). The primary function of ANP and BNP is to control salt-water balance and cardiovascular function9–11, whereas CNP acts in diverse tissues to regulate cell differentiation and function7,8,12,13. One of the major functions of CNP is to promote chondrocyte differentiation in the growth plate of developing bones. In mice, Nppc (encoding the CNP precursor) or Npr2 (encoding the CNP receptor, also known as guanylyl cyclase b or natriuretic peptide receptor b) gene knockout (KO) impairs endochondral ossification and long bone growth14,15. In humans, NPPC and NPR2 mutations have been found in patients with autosomal dominant short stature (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 600296) and acromesomelic dysplasia 1, a severe form of dwarfism (OMIM 108961), respectively16–18. Gain-of-function mutations in the NPR2 gene have also been reported in patients with the Miura-type epiphyseal chondrodysplasia, characterized by tall stature (OMIM 615923)19–21. Currently, CNP analogs are used to treat children with achondroplasia22.

Evolutionarily, the natriuretic peptides were originated from the same ancestral gene in early vertebrates23. These peptides share a high degree of sequence and structural similarities. It is perplexing that only CNP, but not ANP or BNP, has been shown to play a key role in chondrocyte differentiation and bone development. In mice, deletion of the Nppc or Prkg2 (encoding protein kinase G II (PkgII), a primary mediator in CNP signaling) gene results in non-identical skeletal defects14,24–26. These data indicate that more molecules are yet to be discovered that may regulate natriuretic peptide-mediated endochondral ossification in developing bones.

ANP, BNP, and CNP are produced in the precursor form, i.e., pro-ANP, pro-BNP, and pro-CNP, respectively, which are activated by separate proteases7,8. Pro-ANP is activated by corin, a type II transmembrane serine protease originally identified in the heart27,28, whereas pro-CNP is processed by furin, a ubiquitously expressed proprotein convertase29. Both corin and furin were shown to process pro-BNP in vitro30,31. However, furin is likely the primary protease for pro-BNP processing in cardiomyocytes32. In mice and humans, corin deficiency prevents ANP, but not BNP, activation33,34. Consistent with its function in pro-ANP processing, corin is highly expressed in the atria and ventricles of the heart28. Defects in corin function impair ANP activation, causing cardiovascular disease, such as hypertension, preeclampsia, heart failure, cardiac fibrosis, arrhythmia, and stroke34–40.

In addition to the heart, corin expression occurs in non-cardiac tissues, including the kidney, skin, and intestines, where corin-mediated ANP activation enhances salt and water excretion41–43.Previously, Corin mRNA was detected in chondrocytes of mouse embryonic long bones, vertebrae, and facial bones28. Moreover, CORIN mRNA expression was reported in human mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue and bone marrows44,45. These findings suggest a role of corin and ANP in developing bones. The goal of this study is to examine the corin and ANP function and associated molecular mechanisms in chondrocyte differentiation and bone formation. We analyzed developing bones in Corin and Nppa (encoding the ANP precursor) KO mice. We also studied corin and ANP signaling pathways in mouse developing bones and cultured chondrocytes. Our results should help to define the significance of corin and ANP-mediated signaling in chondrocyte differentiation and bone development.

Results

Corin, Nppa, and Npr1 are expressed in developing bones

To examine Corin, Nppa, and Npr1 (encoding natriuretic peptide receptor a) (Npr-a) mRNA expression in developing bones, we did reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using mRNAs from newborn (P0) tibial cartilages of wild-type (WT) and Corin KO mice. Corin mRNA was detected in tibial samples from WT, but not Corin KO, mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Tibial Nppa, Npr1, Npr2 (encoding natriuretic peptide receptor b) (Npr-b), and Npr3 (encoding natriuretic peptide receptor c) (Npr-c) mRNAs were found in WT and Corin KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a). In controls, Corin and Nppa mRNAs were detected in the heart, but not the liver, of WT mice, whereas Npr1, Npr2, and Npr3 mRNAs were found in the liver and heart of WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a). In quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), tibial Corin mRNA levels were minimal in Corin KO mice, compared to those in WT mice, whereas Nppa, Npr1, Npr2, and Npr3 mRNA levels were comparable between WT and Corin KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 1b-f). These results indicate that Corin, Nppa, and Npr1-3 mRNAs are expressed in developing long bones in mice.

Endochondral ossification is delayed in embryonic and postnatal Corin KO mice

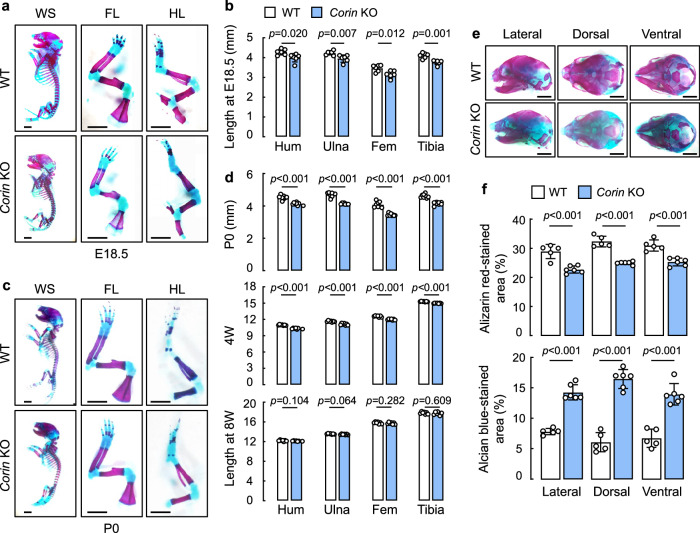

We stained skeletons from WT and Corin KO mice at embryonic day (E) 18.5 with Alizarin red (for bone) and Alcian blue (for cartilage). Skeletons from E18.5 Corin KO embryos were smaller than those from E18.5 WT embryos (Fig. 1a). Particularly, limb long bones, including the humerus, ulna, femur, and tibia in the Corin KO embryos were all shorter than those in the WT embryos (Fig. 1a,b), an indication of defective endochondral ossification. Similar results were found in Corin KO mice at birth (P0) and 4 weeks (W) of age (Fig. 1c,d). At 8 W of age, humeral, ulnar, femoral, and tibial lengths became similar between WT and Corin KO mice (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1. Analysis of skeletons and limb long bones in Corin KO mice.

a,c Whole skeletons (WS), forelimbs (FL), and hindlimbs (HL) from E18.5 (a) and newborn (P0) (c) WT and Corin KO mice were stained with Alizarin red (mineralized bone) and Alcian blue (cartilage). Images are representative of at least six mice per group. b,d Humeral (Hum), ulnar, femoral (Fem), and tibial lengths were measured in E18.5 (b), P0, 4-week (4 W)-, and 8W-old (d) WT and Corin KO mice. n = 6–8 per group. Data are mean ± SD and analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. e Skulls from E18.5 WT and Corin KO mice were stained with Alizarin red and Alcian blue. Representative lateral, dorsal, and ventral skull views were from 5–6 mice per group. Scale bars = 2 mm. f Alizarin red and Alcian blue stained areas in skull lateral, dorsal, and ventral views were quantified. Data are mean ± SD and analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 5–6 per group.

In addition to the long bones, endochondral ossification also contributes to calvarial mineralization and suture fusion via a distinct stem cell population46. We found that skulls from E18.5 Corin KO embryos had less Alizarin red-stained mineralized bones but more Alcian blue-stained cartilages, compared to those from E18.5 WT embryos (Fig. 1e,f). These results indicated that craniofacial bone development was also impaired in Corin KO embryos.

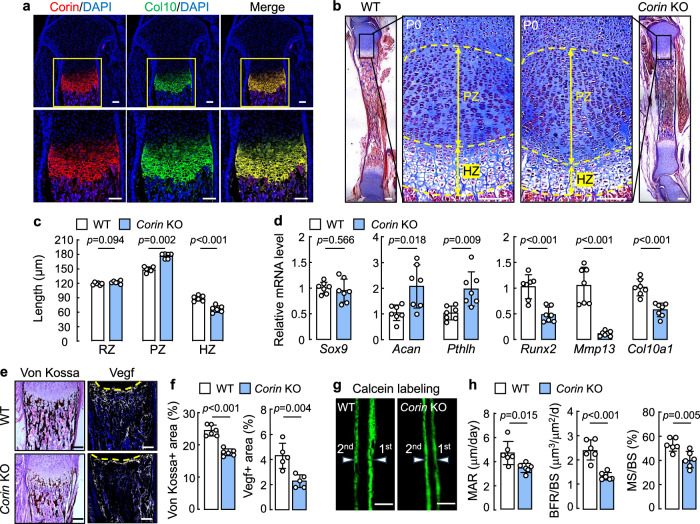

Corin deficiency impairs chondrocyte differentiation in the growth plate and bone formation

We immune stained corin in the growth plate from newborn WT mice. In tibial sections, corin protein was detected in hypertrophic chondrocytes, co-stained with collagen type X (Col10), a hypertrophic chondrocyte marker (Fig. 2a). Weak corin protein staining was also observed under the hypertrophic zone (HZ), probably in osteoblasts, where Col10 protein staining was absent (Fig. 2a). We measured the length of reserve zone (RZ), proliferative zone (PZ), and HZ in the tibial growth plate from newborn WT and Corin KO mice (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Compared to those in WT mice, the RZ length was similar, whereas the PZ was longer and the HZ was shorter in Corin KO mice (Fig. 2b,c). In qPCR with proximal tibial hyalin cartilages, Sox9 (encoding SRY-box transcription factor 9) mRNA levels were similar between newborn WT and Corin KO mice, whereas Acan (encoding aggrecan) and Pthlh (encoding parathyroid hormone-like hormone) mRNA levels were increased in newborn Corin KO mice (Fig. 2d). In contrast, hypertrophic chondrocyte-associated Runx2 (encoding Runt-related transcription factor 2), Mmp13 (encoding matrix metallopeptidase 13), and Col10a1 mRNA levels were reduced in newborn Corin KO mice (Fig. 2d). The mRNA expression profile was consistent with an increase PZ and a decreased HZ in the growth plate, suggesting that Corin deficiency may inhibit the progression of proliferative to hypertrophic chondrocytes in developing long bones.

Fig. 2. Corin expression in the growth plate and effects of Corin deficiency on bone formation.

a Co-staining of tibial corin and Col10 proteins in newborn WT mice. Scale bars = 100 μm. Images are representative of 3 experiments. b Masson’s trichrome staining of tibial sections from newborn WT and Corin KO mice. Proliferative zone (PZ) and hypertrophic zone (HZ) are indicated. Scale bars = 100 μm. c Reserve zone (RZ), PZ, and HZ lengths (mean ± SD) in newborn WT and Corin KO mice analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 6 per group. d mRNA expression in proximal tibial hyalin cartilages from newborn WT and Corin KO mice analyzed by qPCR. Data (mean ± SD) were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 7 per group. e Von Kossa and Vegf protein staining of tibial sections from newborn WT and Corin KO mice. Scale bars = 100 μm. f Quantified data (mean ± SD) of von Kossa and Vegf protein staining were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 5–6 per group. g,h Calcein labeling in the femoral cortical compartments from 3W-old WT and Corin KO mice. Green labeling from 1st and 2nd injections are indicated. Scale bars = 100 μm (g). Values (mean ± SD) of mineral apposition rate (MAR), bone formation rate over bone surface (BFR/BS), and mineralized surface over bone surface (MS/BS) were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 6 per group (h).

Like in newborn Corin KO mice, increased PZ and reduced HZ areas in the tibial growth plate were found in Corin KO mice at 1 W, 2 W, and 4 W of age (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c). By 8 W of age, PZ and HZ sizes became similar between WT and Corin KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c). Additionally, tibial sections from newborn Corin KO mice had less von Kossa staining (black) (for mineral deposits) and lower vascular endothelial growth factor (Vegf) protein staining (white) than those in newborn WT mice (Fig. 2e,f), an indication of impaired osteogenesis in newborn Corin KO mice.

In calcein double labeling, the femoral cortical compartment in 3W-old Corin KO mice had a reduced mineral apposition rate (MAR), an indicator of osteoblast activity and bone formation (Fig. 2g,h). Ratios of bone formation rate over bone surface (BFR/BS) and mineralized surface over bone surface (MS/BS) were also reduced in the Corin KO mice (Fig. 2g,h). Reduced Osterix (Osx) (an osteoblast marker encoded by the Sp7 gene) mRNA and protein levels were found in tibias from newborn Corin KO mice, compared to those in newborn WT mice, by qPCR, immune staining, and western blotting, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3a–e). By contrast, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) (an osteoclast marker encoded by the Acp5 gene) mRNA and protein levels in tibias were comparable between newborn WT and Corin KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 3f-j). These results indicate that Corin deficiency impairs chondrocyte differentiation, osteoblastogenesis, and bone formation in postnatal mice.

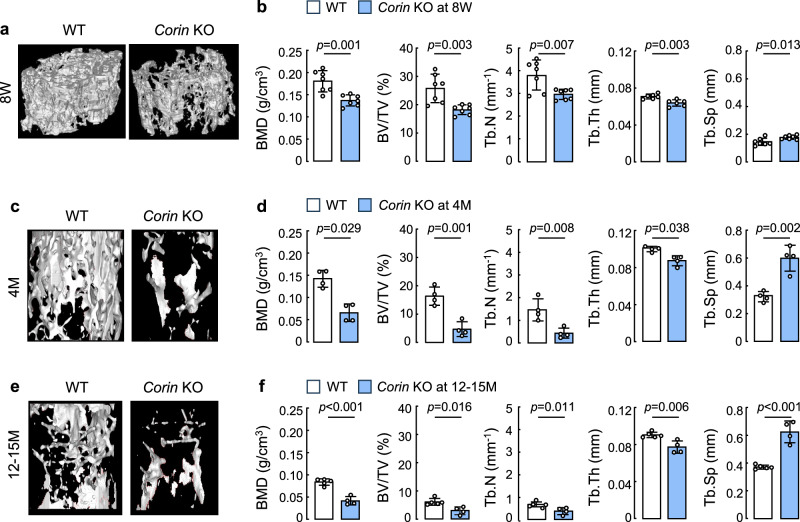

Corin deficiency impairs bone density and microarchitecture in adult mice

Corin protein undergoes ectodomain shedding on the cell surface47. Previously, reduced serum corin protein levels were found in patients with osteoporosis48. We conducted micro-computed tomography (microCT) analyzes in femurs from adult Corin KO mice. At 8 W of age, Corin KO mice had defective bone microarchitecture, as indicated by reduced values in bone mineral density (BMD), bone volume to tissue volume ratio (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), as well as increased trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), compared to those in age-matched WT mice (Fig. 3a,b). The defective femoral microarchitecture was also observed in Corin KO mice at 4 months (Fig. 3c,d) and 12–15 months (Fig. 3e,f) of age. An age-dependent decline in bone density was observed in both WT and Corin KO mice. The BMD values, however, were consistently lower in Corin KO mice than in age-matched WT mice (Fig. 3b,d,f). These results indicate an important role of corin in the maintenance of bone homeostasis in adult mice.

Fig. 3. MicroCT analysis of bone density and microstructure in adult Corin KO mice.

a–f Femurs from male WT and Corin KO mice at 8 weeks (8 W) (a,b), 4 months (4 M) (c,d), and 12–15 months (12–15 M) (e,f) of age were analyzed by microCT. Representative reconstructed 3D-images of femoral segments from 8W- (a), 4M- (c), and 12-15M-old (e) WT and Corin KO mice are shown. Values (mean ± SD) of bone mineral density (BMD), bone volume to tissue volume ratio (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test or nonparametric Mann–Whitney test. n = 4–7 per group.

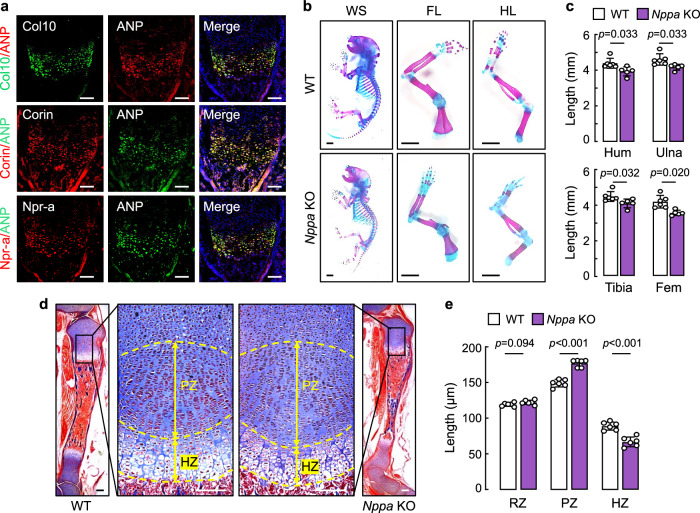

Chondrocyte differentiation and bone formation are impaired in Nppa KO mice

The function of corin in cardiovascular biology is mediated primarily via ANP activation34,49. If the corin function in bone development is also mediated by ANP activation, ANP should be expressed in the growth plate. In tibial sections from newborn WT mice, we showed that ANP was co-stained with Col10, corin, and Npr-a proteins in hypertrophic chondrocytes (Fig. 4a), indicating a corin and ANP pathway in the growth plate. To verify this hypothesis, we generated Nppa KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c) and analyzed their bones. Consistent with the findings in Corin KO mice, newborn Nppa KO mice also had smaller skeletons and shorter long bones, compared to those in newborn WT mice (Fig. 4b,c). In tibial sections from newborn Nppa KO mice, the PZ was greater and the HZ was smaller than those in newborn WT mice (Fig. 4d,e). In contrast, the RZ was comparable between newborn WT and Nppa KO mice (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 4d). Skulls from newborn Nppa KO mice also had less Alizarin red-stained mineralized bones and more Alcian blue-stained cartilages, compared to those in newborn WT mice (Fig. 5a,b).

Fig. 4. ANP and Npr-a expression in the growth plate and effects of Nppa deficiency on bone formation.

a Co-staining of ANP with Col10, corin, or Npr-a proteins in tibial sections from newborn WT mice. Scale bars = 100 μm. Images are representative of three experiments. b Whole skeletons (WS), forelimbs (FL), and hindlimbs (HL) from newborn WT and Nppa KO mice were stained with Alizarin red and Alcian blue. Images are representative of at least five experiments. Scale bars = 2 mm. c Values of humeral (Hum), ulnar, tibial, and femoral (Fem) lengths were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 5–6 per group. d Proliferative zone (PZ) and hypertrophic zone (HZ) in tibial growth plates from newborn WT and Nppa KO mice are indicated. Scale bars = 100 μm. e Values of reserve zone (RZ), PZ, and HZ lengths (mean ± SD) in WT and Nppa KO mice were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 6 per group.

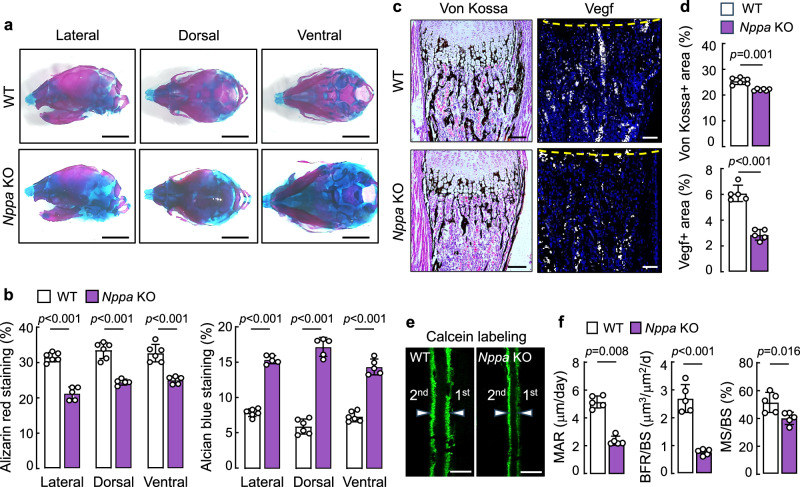

Fig. 5. Analysis of bone phenotype in Nppa KO mice.

a Skulls from newborn WT and Nppa KO mice were stained with Alizarin red and Alcian blue. Representative lateral, dorsal, and ventral skull views were from 5–6 mice per group. Scale bars = 2 mm. b Alizarin red and Alcian blue stained areas in skull lateral, dorsal, and ventral views were quantified. Data (mean ± SD) were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 5–6 per group. c–d Von Kossa and Vegf protein staining of tibial sections from newborn WT and Nppa KO mice (c). Quantified data (mean ± SD) (d) were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 5–6 per group. e,f Calcein double labeling in femoral sections from 3W-old WT and Nppa KO mice. Green labeling from 1st and 2nd injections are indicated. Scale bars = 100 μm (e). Values (mean ± SD) of MAR, BFR/BS, MS/BS were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 5 per group (f).

In tibial sections from newborn Nppa KO mice, reduced von Kossa (black) and Vegf protein (white) staining was observed, compared to that in newborn WT mice (Fig. 5c,d). In calcein double labeling, reduced values of MAR, BFR/BS, and MS/BS were found in the femoral cortical compartment in 3W-old Nppa KO mice (Fig. 5e,f). In microCT analysis, impairs bone density and microarchitecture were also found in the femurs from 8W-old Nppa KO mice, as indicated by reduced values of BMD, BV/TV, Tb.N, and Tb.Th, and increased values of Tb.Sp (Supplementary Fig. 4e,f). Additionally, impaired long and cranial bone development was observed in both male and female E18.5 Corin and Nppa KO embryos (Supplementary Figs. 5,6). Thus, the bone phenotype in Nppa KO mice was like that in Corin KO mice, indicating the importance of the corin and ANP pathway in bone development and homeostasis.

cGMP-PKG signaling in tibial cartilages is inhibited in newborn Corin and Nppa KO mice

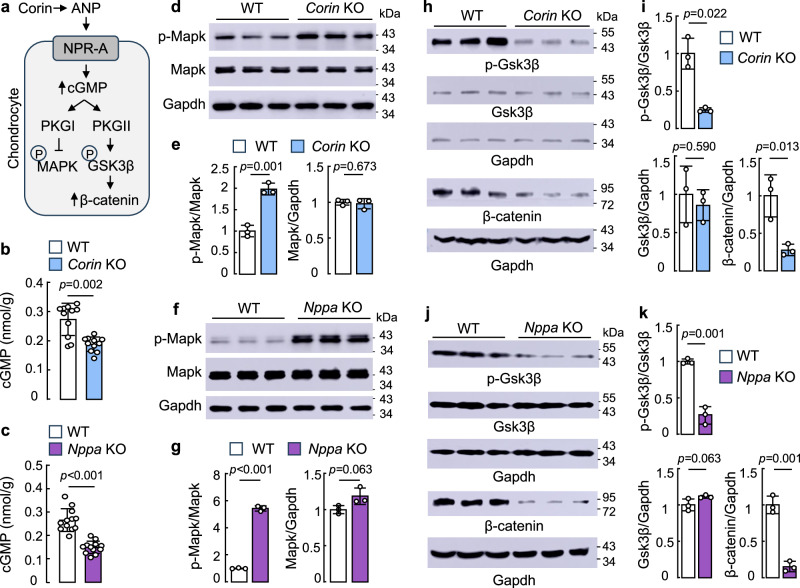

The ANP function in cardiovascular biology is mediated via NPR-A activation and intracellular cGMP production7,8. In chondrocytes, CNP-mediated NPR-B-cGMP-PKGI/II (also called cGKI/II) signaling promotes chondrocyte differentiation7,8. Possibly, a parallel corin/ANP-NPR-A-cGMP signaling pathway exists in chondrocytes to enhance PKGI-mediated inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation and PKGII-mediated glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) phosphorylation/inactivation and β-catenin upregulation, which are critical in chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation (Fig. 6a). In supporting this hypothesis, cGMP levels in tibial cartilage homogenates from newborn Corin (Fig. 6b) and Nppa (Fig. 6c) KO mice were lower than those from newborn WT mice.

Fig. 6. Analysis of corin and ANP-mediated signaling in tibias from Corin and Nppa KO mice.

a A model of corin and ANP-mediated signaling in chondrocytes. P: phosphorylation. b,c cGMP levels in tibial homogenates from newborn WT and Corin (b) or Nppa (c) KO mice. n = 11–12 per group. d–k Western blotting of p-Mapk, Mapk (d–g), p-Gsk-3β, Gsk-3β, and β-catenin (h–k) proteins in tibial cartilage homogenates from newborn WT and Corin (d,e,h,i) or Nppa (f,g,j,k) KO mice. Gapdh was a protein loading control. Protein bands on western blots were quantified. Quantitative data (mean ± SD) were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test. n = 3 per group.

Additionally, increased Mapk phosphorylation was observed in western blotting of tibial cartilage homogenates from newborn Corin (Fig. 6d,e) and Nppa (Fig. 6f,g) KO mice, compared to that in newborn WT mice. Gsk3β phosphorylation and β-catenin protein level were decreased in the tibias from newborn Corin (Fig. 6h,i) and Nppa (Fig. 6j,k) KO mice. Increased cGMP levels are known to increase PGKII expression50,51. In western blotting, PkgI protein levels were similar in the tibias between newborn WT and Corin or Nppa KO mice, whereas PkgII protein levels were reduced in newborn Corin (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b) and Nppa (Supplementary Fig. 7c,d) KO mice. We also examined T-cell factor 1 (Tcf1) protein expression, which could be a downstream effector of PKG and β-catenin signaling depending on cell types13,26,51,52. In western blotting, Tcf1 protein expression was reduced in the tibias from newborn Corin and Nppa KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 7e–h). These results indicate that Corin or Nppa deficiency impairs cGMP generation and PgkI/II signaling in tibial cartilages of newborn mice.

Levels of Indian hedgehog (Ihh) signaling proteins are reduced in tibias from newborn Corin and Nppa KO mice

Ihh signaling is an important mechanism in chondrocyte differentiation in developing bones1,2,53. In the growth plate, Ihh is produced in prehypertrophic and early hypertrophic chondrocytes2,54. We examined the expression of Ihh and its downstream effectors, the patched transmembrane receptor 1 (Ptch1) and zinc finger protein Gli1, in tibias from newborn Corin and Nppa KO mice. Decreased Ihh, Ptch1, and Gli1 mRNA levels and Ihh, Ptch1, and Gli1 protein levels were observed in qPCR and western blotting, respectively, in newborn Corin (Supplementary Fig. 8a–c) and Nppa (Supplementary Fig. 8d–f) KO mice. These results suggest that distorted chondrocyte populations, i.e., increased proliferative and decreased hypertrophic chondrocytes, in newborn Corin and Nppa KO mice may alter other signaling pathways in the growth plate.

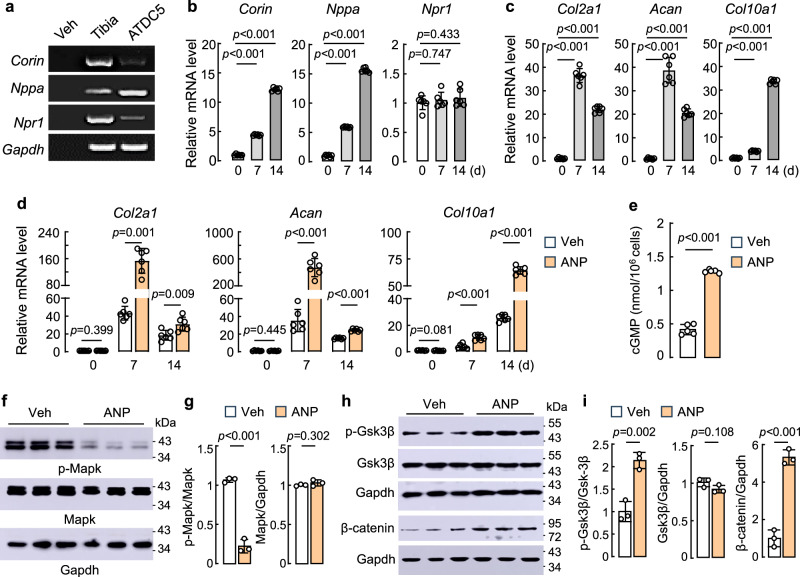

ANP enhances cGMP-PKGI/II signaling in cultured chondrocytes

We verified our findings in ATDC5 cells that can be induced to undergo chondrogenic differentiation in culture55. By RT-PCR, we detected Corin, Nppa, and Npr1 mRNAs in the tibia of newborn WT mice (control) and ATDC5 cells (Fig. 7a). In ATDC5 cells cultured with the induction medium, Corin and Nppa, but not Npr1, mRNAs were upregulated in a time-dependent manner, as shown in qPCR (Fig. 7b). Similarly, Col2a1 (encoding collagen type II α-1), Acan, and Col10a1 mRNA levels were increased in ATDC5 cells with the induction medium (Fig. 7c). The highest Col2a1 and Acan mRNA expression was observed on day 7, whereas the highest Col10a1 mRNA expression was observed on day 14 after the induction, which probably reflected the proliferative and hypertrophic phases in these cells. When the cells were treated with ANP, Col2a1, Acan, and Col10a1 mRNA levels were increased further, but the order of peak mRNA expression remained similar (Fig. 7d), indicating that ANP enhanced chondrogenic differentiation in culture. Consistently, the ANP-treated ATDC5 cells had elevated cGMP levels (Fig. 7e), reduced Mapk phosphorylation (Fig. 7f,g), and increased Gsk3β phosphorylation and β-catenin protein expression (Fig. 7h,i). Increased PkgII, but not PkgI, protein levels were also found the ANP-treated ATDC5 cells (Supplementary Fig. 8g,h). These results indicate that ANP enhanced cGMP-PkgI/II signaling and differentiation in cultured chondrocytes.

Fig. 7. Analysis of corin and ANP-mediated signaling in ATDC5 cells.

a RT-PCR analysis of Corin, Nppa, and Npr1 mRNAs in tibias from newborn WT mice (control) and ATDC5 cells. As a negative control, vehicle (Veh), instead of cDNA templates, was used in the reaction. b,c Relative Corin, Nppa, Npr1 (b), Col2a1, Acan, and Col10a1 (c) mRNA levels in ATDC5 cells before (0) or 7 and 14 days (d) with the induction medium were quantified by qPCR. d Relative Col2a1, Acan, and Col10a1 mRNA levels in ATDC5 cells before (0) or 7 and 14 d in the induction medium without (Veh) or with ANP (100 nM). n = 6 per group. e Intracellular cGMP levels measured by ELISA. n = 5 per group. f-i Western blotting of p-Mapk, Mapk (f,g), p-Gsk-3β, Gsk-3β, and β-catenin (h,i) proteins in ATDC5 cells after 7 days in the induction medium without (Veh) or with ANP. n = 3 per group. Quantitative data (mean ± SD) (g,i) were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test.

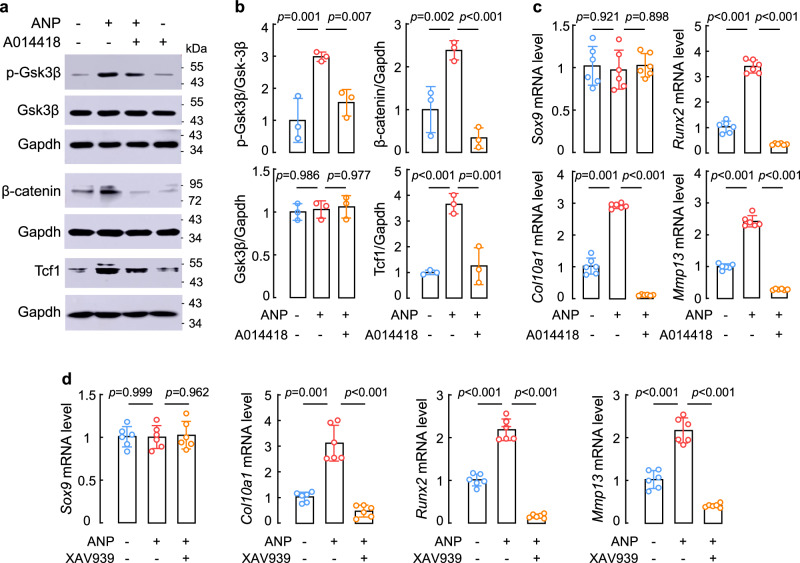

Effects of ANP on chondrocytes are blocked by GSK3β and β-catenin inhibitors

We next tested if GSK3β and β-catenin inhibitors block the effects of ANP on ATDC5 cells. We treated ATDC5 cells with ANP alone or together with AR-A014418, a selective GSK3β inhibitor56. As shown in western blotting, ANP-mediated Gsk3β phosphorylation and β-catenin and Tcf1 protein increase were inhibited by AR-A014418 (Fig. 8a,b). As indicated by qPCR, AR-A014418 treatment did not alter Sox9 mRNA levels, but blocked ANP-mediated upregulation of Col10a1, Runx2, and Mmp13 mRNA expression (Fig. 8c). Similarly, XAV939 treatment, which promotes β-catenin protein degradation57, in ATDC5 cells did not alter Sox9 mRNA levels, but prevented Col10a1, Runx2, and Mmp13 mRNA increase induced by ANP (Fig. 8d). These results are consistent with a role of ANP in enhancing cGMP-PKGI/II signaling to promote chondrocyte differentiation.

Fig. 8. Effects of Gsk3β and β-catenin inhibitors on ANP signaling and chondrogenic responses in ATDC5 cells.

a,b Western blotting of p-Gsk3β, Gsk3β, β-catenin, and T-cell factor 1 (Tcf1) proteins in ATDC5 cells cultured without (−) or with (+) ANP (100 nM), AR-A014418 (GSK3β inhibitor) (10 μM), and/or XAV939 (β-catenin inhibitor) (10 μM) (a). Protein bands on western blots were analyzed by densitometry (b). Quantitative data (mean ± SD) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. n = 3 per group. c,d Relative Sox9, Col10a1, Runx2, and Mmp13 mRNA levels in ATDC5 cells after 7 days in the induction medium without (−) or with (+) ANP, AR-A014418 (c), and/or XAV939 (d). n = 6 per group. Quantitative data (mean ± SD) were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

Discussion

For decades, ANP and CNP have been known for their primary functions in cardiovascular biology and chondrocyte differentiation, respectively. In this study, we uncovered an important corin and ANP function in chondrocyte differentiation and endochondral ossification, which is non-redundant with the CNP function in bone development. We showed that Corin and Nppa KO mice had more proliferative and less hypertrophic chondrocytes in the growth plate and shortened limb-long bones at birth. It has been shown that hypertrophic chondrocytes may undergo further differentiation to become osteoblasts and osteocytes in endochondral bone formation58–60. In line with these reports, we found less osteoblasts, decreased mineral deposition, and low Vegf protein expression in tibial sections from newborn Corin and Nppa KO mice. Impaired bone formation was also detected in the femurs from 3W-old Corin and Nppa KO mice. Previously, increased corin expression was reported in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal and induced pluripotent stem cells that underwent chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation45,61,62. Together, these findings are consistent, highlighting a critical role of corin and ANP in regulating chondrocyte differentiation, endochondral ossification, and bone formation.

Unlike in long bones that are formed via endochondral ossification, cranial bones are developed primarily via intramembranous ossification, although endochondral ossification also contributes to the formation of cranial base bones63. A recent study has shown that endochondral ossification, mediated via a distinct stem cell population, is critical in cranial bone mineralization and suture fission46. In our study, we detected increased cartilages and delayed bone formation and mineralization in skulls from newborn Corin and Nppa KO mice. These results indicated that corin and ANP-mediated endochondral ossification also participated in cranial bone formation. Currently, we do not have the evidence that corin and ANP are involved in intramembranous ossification. More investigations are required to exclude such a possibility.

As a transmembrane protease, corin is expected to function at its expression site. In immune-stained tibial sections from newborn WT mice, corin, ANP, and Npr-a proteins were co-localized in hypertrophic, but not proliferative, chondrocytes, suggesting that corin-mediated ANP activation and signaling may act as an autocrine mechanism to regulate the differentiation of specific chondrocyte population(s). In this regard, the CNP function in developing bones is also medicated via an autocrine, but not endocrine, mechanism64. Considering their distinct protein expression profile in hypertrophic chondrocytes, corin and ANP are likely to regulate the transition of proliferative to hypertrophic chondrocytes in the growth plate. Additional studies with chondrocyte conditional Corin and Nppa KO mice will be important to verify the autocrine function of corin and ANP in developing bones.

In chondrocytes, CNP signaling is mediated primarily via NPR-B-dependent cGMP generation and subsequent PKGI and PKGII activation8,65. In turn, PKGI inhibits fibroblast growth factor receptor 3-mediated signaling and MAPK phosphorylation, thereby promoting chondrocyte proliferation and extracellular matrix production. In parallel, PKGII phosphorylates and inactivates GSK3β, thereby upregulating β-catenin protein expression to induce hypertrophy in chondrocytes. Collectively, PKGI and PKGII signaling enhances chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. It appears that the corin and ANP function in chondrocytes is mediated by a similar mechanism, via NPR-A activation, to stimulate cGMP-dependent PKGI and PKGII activation and signaling. In agreement with this hypothesis, reduced cGMP levels, increased Mapk phosphorylation, decreased Gsk3β phosphorylation, and diminished β-catenin and Tcf1 protein levels were all observed in tibias from newborn Corin and Nppa KO mice. Conversely, ANP treatment increased cGMP levels, decreased Mapk phosphorylation, stimulated Gsk3β phosphorylation, and elevated β-catenin protein levels in ATDC5 cells. Moreover, the effects of ANP on PkgI and PkgII signaling and chondrogenic differentiation were blocked by Gsk3β and β-catenin inhibitors in ATDC5 cells.

If the ANP and CNP functions in chondrocytes are mediated via similar signaling pathways, why do the bone phenotypes in Corin and Nppa KO mice differ markedly from that in Nppc KO mice? Corin and Nppa KO mice, for example, did not exhibit severe dwarfism observed in Nppc KO mice14. Corin and Nppa KO mice had an increased PZ, whereas Nppc KO mice had a decreased PZ in the growth plate14. The apparent difference may be due to, in part, the differential ANP and CNP distribution in chondrocyte populations. CNP is mostly in proliferative and prehypertrophic chondrocytes14, whereas corin and ANP are primarily in hypertrophic chondrocytes. CNP signaling in proliferative chondrocytes is expected to promote cell growth, extending chondrocyte columns and hence the length of developing bones. On the other hand, ANP signaling in hypertrophic chondrocytes may have limited effects on chondrocyte proliferation and column growth in the growth plate. Indeed, CNP was much more potent than ANP in increasing fetal tibial length in organ culture66. Additionally, differential PKGI and PKGII distribution in the growth plate may also impact ANP and CNP signaling and function. PKGI is mainly in hypertrophic chondrocytes, whereas PKGII is primarily in late proliferative and early hypertrophic chondrocytes24. PKGII is a major downstream mediator in CNP signaling24–26. Conceivably, PKGI may play a more dominant role in mediating ANP signaling in hypertrophic chondrocytes. In hypertrophic chondrocytes, Ihh and its effectors are important in cell growth and differentiation1,2,53. In our study, reduced Ihh, Ptch1, and Gli1 mRNA and Ihh, Ptch1, and Gli1 protein levels were found in the tibias from newborn Corin and Nppa KO mice. The low mRNA and protein expression of the Ihh signaling molecules may reflect less hypertrophic chondrocytes in the growth plate of these KO mice. Alternatively, the corin and ANP pathway may regulate the expression of Ihh signaling molecules in hypertrophic chondrocytes. Further studies will be important to elucidate the molecular mechanisms that dictate the non-redundant ANP and CNP functions in specific chondrocyte populations and to understand if other pathways are compensated in Corin and Nppa KO mice.

In addition to bone development, endochondral ossification and osteogenesis participate in bone repair and remodeling3,67. In Corin KO mice at 8 W of age, limb bone lengths became comparable to those in WT mice, which may reflect the plasticity of bone remodeling to compensate some developmental defects in endochondral ossification. A similar finding was reported in Mmp9 (encoding matrix metalloproteinase 9) KO mice, in which impaired chondrocyte differentiation in the growth plate was normalized by 8 W of age68. In microCT analyzes, we found reduced bone density and abnormal trabecular structures in femurs from 8W-old Corin and Nppa KO mice. In a previous study, femurs in 10W-old Corin KO mice were found to be stiffer and more brittle than those in WT mice69. In this study, we found that the defects in bone density worsened as Corin KO mice became older. Previously, decreased serum corin protein levels were found in patients with osteopenia and osteoporosis48. These data suggest that impaired corin and ANP function and signaling may be detrimental to bone remodeling and density, which may contribute to bone disease such as osteoporosis in elderly human populations. Further studies will be important to determine if other factors, e.g., dietary salt, may alter the corin and ANP function in bone homeostasis.

In summary, corin and ANP are important in cardiovascular homeostasis. Here, we show that corin and ANP also function in developing bones to regulate chondrocyte differentiation, osteogenesis, and bone formation. The corin and ANP function in chondrocytes is likely mediated via cGMP-dependent PKGI/II signaling. In adult mice, Corin and Nppa deficiency reduces bone density and impairs bone microarchitecture. These findings indicate that corin and ANP signaling and CNP signaling act separately in chondrocytes and osteocytes to regulate bone development and homeostasis. Our findings extend the knowledge regarding the biology of corin and ANP.

Methods

Mice

All experiments in mice were carried out with a protocol (202006A355) approved by the Soochow University Animal Ethics Committee. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. B6-Corintm1NJU/SU (referred to as Corin KO in this study) mice were generated by deleting Corin exon 442,43. The lack of Corin mRNA and protein expression in these mice was verified by RT-PCR and western blotting, respectively42,43. Corin KO mice had reduced ANP ( < 100 vs. ~700 pg/mL in WT mice), but not pro-ANP ( ~ 1160 vs. ~1200 pg/mL in WT mice), levels in plasma. B6-Nppatm1/SU (referred to as Nppa KO in this study) mice were created by deleting Nppa exons 1–3 with a CRISPR/Cas9 method (GemPharmatech, Nanjing, China) (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Genotyping was done by PCR (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The lack of Nppa mRNA expression in hearts from Nppa KO mice was verified by RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Among Corin and Nppa KO mice, the male to female ratio was approximately 1:1. Both strains of Corin and Nppa KO mice were bred into the C57BL/6 J background. WT C57BL/6 J and Corin and Nppa KO mice were housed in a temperature controlled specific-pathogen-free facility with 12-h light-dark cycles and free access to water and normal chow diet. In timed mating, detection of a vaginal plug was set as embryonic day (E) 0.5. For histological and molecular analyzes described below, tissues from E18.5 embryos and newborn mice of both genders were used.

PCR, RT-PCR and qPCR

PCR with genomic DNA and primers for the Sry (sex-determining region Y) gene was done to determine the gender of embryos. Total RNAs were extracted from cultured cells or fresh tissues (liver, heart, and tibias) from newborn WT and Corin or Nppa KO mice using Trizol reagent (15596018, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Reverse transcription was done using a kit (K1622, Thermo Fisher Scientific) to make cDNAs. Corin, Nppa, Npr1, Npr2, and Npr3 mRNAs were examined by PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis. qPCR was used to assess mRNA levels with the QuantStudio 6 real-time PCR system (A25742, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Gapdh (encoding glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) expression was used for data normalization. Supplementary Table 1 lists the oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

Skeletal staining

Mouse skeletons were stained with Alcian blue and Alizarin red. Briefly, 0.3% (w/v) Alcian blue (A9186, Sigma) in 70% ethanol and 0.1% (w/v) Alizarin red (71001954, Sinopharm Chemical Reagents, Shanghai, China) in 95% ethanol were prepared. The Alcian blue and Alizarin red solutions, glacial acetic acid, and 70% ethanol were mixed in a 1:1:1:17 (v/v) ratio and kept at 40 °C for 12 h. After removal of the skin, entrails, and adipose tissue, E18.5 and newborn mice were fixed in 95% ethanol for 48 h, followed by staining with the Alcian blue and Alizarin red solution for 48 h. The samples were de-stained in 1% KOH for 48 h, 1% KOH in 20% glycerol for 48 h, and 1% KOH in 50% glycerol for 48 h. After the cartilage turned blue and clear, the stained skeletons were stored in 100% glycerol. The whole skeletons and separated skulls and limbs were examined under an Asana microscope (Olympus, SZX16, Tokyo, Japan). The data were analyzed by Image-Pro-Plus software (Media Cybernetics, V5.1).

Immunofluorescent and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

The experiments were done with tibias from newborn mice. For frozen sections, tibias were incubated in 20% sucrose at 4 °C for 24 h and embedded in OCT reagent (4583, Sakura, Torrance, CA, USA). Serial 10 μm-thick sections were cut. For paraffin sections, the tibias were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned (4 μm in thickness). The sections were incubated with primary antibodies against corin (1:50, ab255812, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), ANP (1:50, ab190001, Abcam), Npr-a (1:200, GTX109810, GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA), Col10 (1:50, ab260040, Abcam or 1:50, sc-59954, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), and Vegf (1:200, MA1-16629, Invitrogen). After 12 h at 4 °C, the sections were washed and incubated with a secondary antibody labeled with Alexa-488 (1:500, A21202, Invitrogen), Alexa-594 (1:500, A11012, Invitrogen), or Alexa-647 (1:500, ab150131, Invitrogen) at room temperature for 2 h. After washing, a DAPI solution (0100-20, Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) was added to stain cell nuclei. The sections were examined under a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1000, Tokyo, Japan).

For IHC, paraffin tibial sections from newborn (P0) WT and Corin KO mice were dewaxed and stained with an antibody against Osx (1:1000, ab209484, Abcam) at 4 °C for 12 h. After washing, the sections were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (MaxVision, kit-5005, Maxim Biotechnologies, Fuzhou, China), counterstained with Hematoxylin, and examined under a light microscope (Leica DM2000 LED, Leica Geosystems, Heerbrugg, Switzerland).

Masson’s trichrome staining

Tibias from WT and Corin KO or Nppa KO littermates at P0 and 1–8 W were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 h. Before paraffin embedding, the tibias from 1-8W-old mice were decalcified in 0.5 M EDTA, pH 7.4, at 4 °C for 48 h. Five μm-sections cut with a microtome (RM2245, Leica, Nussloch, Germany) were placed on gelatin-coated slides (Citotest Scientific, 188105, Haimen, China), deparaffinized with xylene, dehydrated with gradient alcohol, stained with Masson’s trichrome (G1340, Solarbio Life Science, Beijing, China), and examined under a light microscope (DM2000 LED, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Growth plate measurements

The proximal tibial growth plate in the Masson’s trichrome stained sections was evaluated using Image-Pro-Plus software. The lengths of RZ, PZ, and HZ, parallel to chondrocyte columns, were measured based on cell morphology and arrangements. The RZ included tightly packed chondrocytes between the apical growth plate border and the top PZ edge. The PZ consisted of flattened columnar chondrocytes, whereas the HZ included large vacuolar chondrocytes. For each mouse, at least 2 sections were analyzed. Each study group had six mice.

Von Kossa staining

To evaluate mineral deposits, tibial sections from newborn mice were incubated in 1% silver nitrate for 20 min under UV light. Excess silver was removed by incubation in 5% sodium thiosulfate for 5 min, followed by hematoxylin and eosin staining. The sections were examined under a light microscope (DM2000 LED, Leica). Image J software was used to quantify the stained area.

TRAP staining

TRAP staining was done with paraffin tibial sections from newborn WT and Corin KO mice using a commercial kit (G1492, Solarbio, Beijing, China). In brief, the sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and fixed with a TRAP fixative at 4 °C. After 1 min, the sections were washed with water, and incubated with a TRAP staining solution at 37 °C for 1 h. After washing with water, the sections were re-stained with methyl green for 1 min, sealed with neutral resin liquid, and photographed under a light microscope.

Calcein double labeling

To examine bone growth, 3W-old mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.1% calcein (C0875, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) (20 mg/kg body weight) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), followed by another injection in four days. Femurs were isolated three days later, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in ethanol solutions, embedded with methyl methacrylate, and sectioned (100 μm in thickness). The fluorescent calcein signals in cortical bone were observed under a microscope (Leica DMIL LED, Leica Geosystem, Heerbrugg, Switzerland). Values of MAR, BFR/BS, and MS/BS were measured using Image-Pro-Plus software.

MicroCT analysis

Femurs from mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 h and analyzed with the SkyScan 1176 scanner (Bruker, Aartselaar, Belgium) at a voxel resolution of 9 μm. The voltage and current of the scanner were 50 kV and 500 μA, respectively. The data were analyzed by CTAn software (Bruker). Trabecular bones were evaluated in the distal femoral metaphysis. Region of interest selected for trabecular bone analysis was 0.54 to 1.35 mm proximal to the growth plate of the distal femur, following the guidelines of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research70. Values of BMD, BV/TV, Tb.N, Tb.Th, and Tb.Sp were calculated. Three-dimensional images were reconstructed using Mimics software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium).

Cell culture

ATDC5 cells (iCell Bioscience, Shanghai, China) were cultured in DMEM/Ham’s-F12 medium (10-092-CVRC, Corning, New York, NY, USA) with 5% fetal bovine serum (U16001DC, EallBio Life Sciences, Beijing, China) at 37 °C. Chondrogenic differentiation was induced in the medium with 1% insulin/transferrin/sodium selenite (I3146, Sigma). The effects of ANP (100 nM, AS-20648, Anaspec, Fremont, CA, USA), AR-A014418 (GSK-3β inhibitor) (10 μM, S7435, Selleck, Houston, TX, USA), and XAV939 (β-catenin inhibitor) (10 μM, S1180, Selleck) on ATDC5 cells were tested in culture for 7 days with fresh medium changed every other day.

cGMP measurement

Proximal tibial hyaline cartilages from newborn mice were homogenized in PBS with a protease inhibitor mixture (1:100, 04693116001, Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland). Cultured ATDC5 cells were lysed with 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and the protease inhibitor mixture. cGMP levels in the tissue homogenates or cell lysates were examined by ELISA (ADI-900-013, Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blotting

Tibial tissues from newborn mice were lysed in RIPA solution (P0013B, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) with pooled protease/phosphatase inhibitors (1:100, 78442, Thermo Fisher Scientific). ATDC5 cells were lysed in a Tris-HCl solution (50 mM, pH 8.0) with 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, and mixed protease inhibitors (1:100, 04693116001, Roche Applied Science). Proteins were quantified with a BCA assay (23227, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The samples in loading buffer with 2.5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol (444203, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and western blotting. Antibodies used were against phospho (p)-Gsk3β (1:1000, 5558, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), Ihh (0.1 μg/mL, AF1705, R&D Systems, Minnesota, USA), Ptch1 (1:2000, AF5202, Affinity, Jiangsu, China), Gli1 (1:5000, 66905-1-Ig, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), p-Mapk (1:1000, 9154 T, Cell Signaling), Mapk (1:1000, 8727 T, Cell Signaling), Gsk3β (1:1000, 12456, Cell Signaling), Osx (1:1000, ab209484, Abcam), PkgI (1:1000, 3248S, Cell Signaling,), PkgII (1:1000, PA5-101156, Invitrogen), β-catenin (1:1000, ab32572, Abcam), Tcf1 (1:1000, 2203 T, Cell Signaling), TRAP (1:1000, ab191406, Abcam), Gapdh (1:10000, MB001H, Bioworld, Nanjing, China), and an horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000, BS13278, Bioworld). Gapdh was used as a control. Protein bands on the blots were analyzed by Amersham Imager 600 (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) and quantified by densitometry.

Statistics and reproducibility

Analyzes were done using Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Data normality was verified by Anderson-Darling, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, D’Agostino-Pearson, and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test or nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to compare two groups. One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison tests were used to compare multiple groups. The sample sizes and number of replicates in individual experiments were indicated. All data were presented as means ± SD. P values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171112 and 32471158 to ND), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20211074 to HZ), Suzhou Key Disciplines (SZXK202104 to HZ), Interdisciplinary Basic Frontier Innovation Program of Suzhou Medical College of Soochow University (YXY2304065 to TZ), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutes (to Soochow University).

Author contributions

ND, QW, and HZ conceived, designed, and supervised the project. ZZ, XM, CJ, WL, TZ, ML, SS, and MW conducted experiments, collected, and/or organized the data. ZZ, XM, CJ, ND, QW, and HZ analyzed and interpreted the data. ZZ, ND, HZ, and QW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and commented on the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Gretl Hendrickx and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Christina Karlsson Rosenthal.

Data availability

All relevant data are included in the published article and in the supplementary information. Images of the original blots/gels can be found in Supplementary Information and the original data sets used to make bar graphs in Supplementary Data 1. Additional data generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zibin Zhou, Xiaoyu Mao, Chun Jiang.

Contributor Information

Ningzheng Dong, Email: ningzhengdong@suda.edu.cn.

Qingyu Wu, Email: wuqy@suda.edu.cn.

Haibin Zhou, Email: zhouhaibin@suda.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-07077-6.

References

- 1.Kronenberg, H. M. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature423, 332–336 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kozhemyakina, E., Lassar, A. B. & Zelzer, E. A pathway to bone: signaling molecules and transcription factors involved in chondrocyte development and maturation. Development142, 817–831 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salhotra, A., Shah, H. N., Levi, B. & Longaker, M. T. Mechanisms of bone development and repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.21, 696–711 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortega, N., Behonick, D. J. & Werb, Z. Matrix remodeling during endochondral ossification. Trends Cell Biol.14, 86–93 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dy, P. et al. The three SoxC proteins–Sox4, Sox11 and Sox12–exhibit overlapping expression patterns and molecular properties. Nucleic Acids Res36, 3101–3117 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuscik, M. J., Hilton, M. J., Zhang, X., Chen, D. & O’Keefe, R. J. Regulation of chondrogenesis and chondrocyte differentiation by stress. J. Clin. Invest118, 429–438 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potter, L. R., Abbey-Hosch, S. & Dickey, D. M. Natriuretic peptides, their receptors, and cyclic guanosine monophosphate-dependent signaling functions. Endocr. Rev.27, 47–72 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn, M. Molecular physiology of membrane guanylyl cyclase receptors. Physiol. Rev.96, 751–804 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goetze, J. P. et al. Cardiac natriuretic peptides. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.17, 698–717 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishikimi, T. & Kato, J. Cardiac peptides-current physiology, pathophysiology, biochemistry, molecular biology, and clinical application. Biol. (Basel)11, 330 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang, W. et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide promotes uterine decidualization and a TRAIL-dependent mechanism in spiral artery remodeling. J. Clin. Invest131, e151053 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moyes, A.J. & Hobbs, A.J. C-type Natriuretic Peptide: A Multifaceted Paracrine Regulator in the Heart and Vasculature. Int J Mol Sci20, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Werner, F. et al. Ablation of C-type natriuretic peptide/cGMP signaling in fibroblasts exacerbates adverse cardiac remodeling in mice. JCI Insight8, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Chusho, H. et al. Dwarfism and early death in mice lacking C-type natriuretic peptide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA98, 4016–4021 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamura, N. et al. Critical roles of the guanylyl cyclase B receptor in endochondral ossification and development of female reproductive organs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA101, 17300–17305 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hisado-Oliva, A. et al. Mutations in C-natriuretic peptide (NPPC): a novel cause of autosomal dominant short stature. Genet Med20, 91–97 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartels, C. F. et al. Mutations in the transmembrane natriuretic peptide receptor NPR-B impair skeletal growth and cause acromesomelic dysplasia, type Maroteaux. Am. J. Hum. Genet75, 27–34 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasques, G. A., Arnhold, I. J. & Jorge, A. A. Role of the natriuretic peptide system in normal growth and growth disorders. Horm. Res Paediatr.82, 222–229 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miura, K. et al. An overgrowth disorder associated with excessive production of cGMP due to a gain-of-function mutation of the natriuretic peptide receptor 2 gene. PLoS One7, e42180 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miura, K. et al. Overgrowth syndrome associated with a gain-of-function mutation of the natriuretic peptide receptor 2 (NPR2) gene. Am. J. Med Genet A164a, 156–163 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hannema, S. E. et al. An activating mutation in the kinase homology domain of the natriuretic peptide receptor-2 causes extremely tall stature without skeletal deformities. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.98, E1988–E1998 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savarirayan, R. et al. C-type natriuretic peptide analogue therapy in children with achondroplasia. N. Engl. J. Med381, 25–35 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takei, Y. From aquatic to terrestrial life: evolution of the mechanisms for water acquisition. Zool. Sci.32, 1–7 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeifer, A. et al. Intestinal secretory defects and dwarfism in mice lacking cGMP-dependent protein kinase II. Science274, 2082–2086 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyazawa, T. et al. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase II plays a critical role in C-type natriuretic peptide-mediated endochondral ossification. Endocrinology143, 3604–3610 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawasaki, Y. et al. Phosphorylation of GSK-3beta by cGMP-dependent protein kinase II promotes hypertrophic differentiation of murine chondrocytes. J. Clin. Invest118, 2506–2515 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan, W., Wu, F., Morser, J. & Wu, Q. Corin, a transmembrane cardiac serine protease, acts as a pro-atrial natriuretic peptide-converting enzyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA97, 8525–8529 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan, W., Sheng, N., Seto, M., Morser, J. & Wu, Q. Corin, a mosaic transmembrane serine protease encoded by a novel cDNA from human heart. J. Biol. Chem.274, 14926–14935 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu, C., Wu, F., Pan, J., Morser, J. & Wu, Q. Furin-mediated processing of Pro-C-type natriuretic peptide. J. Biol. Chem.278, 25847–25852 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ichiki, T., Huntley, B. K. & Burnett, J. C. Jr BNP molecular forms and processing by the cardiac serine protease corin. Adv. Clin. Chem.61, 1–31 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semenov, A. G. et al. Processing of pro-B-type natriuretic peptide: furin and corin as candidate convertases. Clin. Chem.56, 1166–1176 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishikimi, T. et al. Pro-B-type natriuretic peptide is cleaved intracellularly: impact of distance between O-glycosylation and cleavage sites. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol.309, R639–R649 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen, S. et al. PCSK6-mediated corin activation is essential for normal blood pressure. Nat. Med21, 1048–1053 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baris Feldman, H. et al. Corin and left atrial cardiomyopathy, hypertension, arrhythmia, and fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med389, 1685–1692 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rame, J. E. et al. Corin I555(P568) allele is associated with enhanced cardiac hypertrophic response to increased systemic afterload. Hypertension49, 857–864 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui, Y. et al. Role of corin in trophoblast invasion and uterine spiral artery remodelling in pregnancy. Nature484, 246–250 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang, Y. et al. Identification and functional analysis of CORIN variants in hypertensive patients. Hum. Mutat.38, 1700–1710 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gladysheva, I. P., Sullivan, R. D. & Reed, G. L. Falling corin and ANP activity levels accelerate development of heart failure and cardiac fibrosis. Front Cardiovasc Med10, 1120487 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen, L. et al. Association between CORIN promoter methylation and stroke: Results from two independent samples of Chinese adults. Front Neurol.14, 1103374 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao, Y. et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the 3’ untranslated region of corin associated with cardiovascular diseases in a chinese han population: a case-control study. Front Cardiovasc Med8, 625072 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gu, X. et al. Corin deficiency diminishes intestinal sodium excretion in mice. Biol. (Basel)12, 945 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He, M. et al. The protease corin regulates electrolyte homeostasis in eccrine sweat glands. PLoS Biol.19, e3001090 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou, T. et al. Renal corin is essential for normal blood pressure and sodium homeostasis. Int J. Mol. Sci.23, 11251 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Charoenpanich, A. et al. Microarray analysis of human adipose-derived stem cells in three-dimensional collagen culture: osteogenesis inhibits bone morphogenic protein and Wnt signaling pathways, and cyclic tensile strain causes upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine regulators and angiogenic factors. Tissue Eng. Part A17, 2615–2627 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu, T. M. et al. Identification of common pathways mediating differentiation of bone marrow- and adipose tissue-derived human mesenchymal stem cells into three mesenchymal lineages. Stem Cells25, 750–760 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bok, S. et al. A multi-stem cell basis for craniosynostosis and calvarial mineralization. Nature621, 804–812 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang, J. et al. Ectodomain shedding and autocleavage of the cardiac membrane protease corin. J. Biol. Chem.286, 10066–10072 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou, H. et al. Reduced serum corin levels in patients with osteoporosis. Clin. Chim. Acta426, 152–156 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chan, J. C. et al. Hypertension in mice lacking the proatrial natriuretic peptide convertase corin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA102, 785–790 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramdani, G. et al. cGMP-dependent protein kinase-2 regulates bone mass and prevents diabetic bone loss. J. Endocrinol.238, 203–219 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoo, Y. M., Jung, E. M., Ahn, C. & Jeung, E. B. Nitric oxide prevents H(2)O(2)-induced apoptosis in SK-N-MC human neuroblastoma cells. Int J. Biol. Sci.14, 1974–1984 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flores-Costa, R. et al. Stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase exerts antiinflammatory actions in the liver through a VASP/NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome circuit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA117, 28263–28274 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vortkamp, A. et al. Regulation of rate of cartilage differentiation by Indian hedgehog and PTH-related protein. Science273, 613–622 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen, X., Macica, C. M., Nasiri, A. & Broadus, A. E. Regulation of articular chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation by indian hedgehog and parathyroid hormone-related protein in mice. Arthritis Rheum.58, 3788–3797 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yao, Y. & Wang, Y. ATDC5: an excellent in vitro model cell line for skeletal development. J. Cell Biochem114, 1223–1229 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kunnimalaiyaan, S., Gamblin, T. C. & Kunnimalaiyaan, M. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor AR-A014418 suppresses pancreatic cancer cell growth via inhibition of GSK-3-mediated Notch1 expression. HPB (Oxf.)17, 770–776 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang, S. M. et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature461, 614–620 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Descalzi Cancedda, F., Gentili, C., Manduca, P. & Cancedda, R. Hypertrophic chondrocytes undergo further differentiation in culture. J. Cell Biol.117, 427–435 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang, L., Tsang, K. Y., Tang, H. C., Chan, D. & Cheah, K. S. Hypertrophic chondrocytes can become osteoblasts and osteocytes in endochondral bone formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA111, 12097–12102 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang, G. et al. Osteogenic fate of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell Res24, 1266–1269 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou, H., Zhu, J., Liu, M., Wu, Q. & Dong, N. Role of the protease corin in chondrogenic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med12, 973–982 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu, D. et al. Systematic transcriptome profiling of hPSC-derived osteoblasts unveils CORIN’s mastery in governing osteogenesis through CEBPD modulation. J. Biol. Chem.300, 107494 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rengasamy Venugopalan, S. & Van Otterloo, E. The Skull’s Girder: A Brief Review of the Cranial Base. J Dev Biol9, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Nakao, K. et al. The Local CNP/GC-B system in growth plate is responsible for physiological endochondral bone growth. Sci. Rep.5, 10554 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yasoda, A. & Nakao, K. Translational research of C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) into skeletal dysplasias. Endocr. J.57, 659–666 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yasoda, A. et al. Natriuretic peptide regulation of endochondral ossification. Evidence for possible roles of the C-type natriuretic peptide/guanylyl cyclase-B pathway. J. Biol. Chem.273, 11695–11700 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Einhorn, T. A. The science of fracture healing. J. Orthop. Trauma19, S4–S6 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vu, T. H. et al. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell93, 411–422 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nordberg, R. C., Wang, H., Wu, Q. & Loboa, E. G. Corin is a key regulator of endochondral ossification and bone development via modulation of vascular endothelial growth factor A expression. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med12, 2277–2286 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bouxsein, M. L. et al. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J. Bone Min. Res25, 1468–1486 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in the published article and in the supplementary information. Images of the original blots/gels can be found in Supplementary Information and the original data sets used to make bar graphs in Supplementary Data 1. Additional data generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.