Abstract

Fruit ripening is a highly coordinated process involving molecular and biochemical changes that collectively determine fruit quality. The underlying metabolic programs and their transitions leading to fruit ripening remain largely under-characterized in blueberry (Vaccinium sp.), which exhibits atypical climacteric behavior. In this study, we focused on sugar, acid and anthocyanin metabolism in two rabbiteye blueberry cultivars, Premier and Powderblue, during fruit development and ripening. Concentrations of the three major sugars, sucrose (Suc), glucose (Glc), and fructose (Fru) increased steadily during fruit development leading up to ripening, and increased dramatically by around 2-fold in ‘Premier’ and 2- to 3-fold in ‘Powderblue’ during the final stage of fruit ripening. Starch concentration was very low throughout fruit development in both cultivars indicating that it does not serve the role of a major transitory carbon (C) storage form in blueberry fruit. Together, these patterns indicate continued import of C, likely in the form of Suc, throughout blueberry fruit development. Concentrations of the predominant acids, malate and quinate, decreased during ripening, and may contribute to increased shikimate biosynthesis which, in-turn, allows for downstream phenylpropanoid metabolism leading to anthocyanin synthesis. Consistently, anthocyanin concentrations were highest in fully ripened blue fruit. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was performed using a ‘Powderblue’ fruit ripening transcriptome and targeted fruit metabolite concentration data. A ‘dark turquoise’ module positively correlated with sugars and anthocyanins, and negatively correlated with acids (malate, quinate), was identified. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of this module identified transcripts related to sugar, acid, and phenylpropanoid metabolism pathways. Among these, increased transcript abundance of a VACUOLAR INVERTASE during ripening was consistent with sugar storage in the vacuole. In general, transcript abundance of the glycolysis pathway genes was upregulated during ripening. The transcript abundance of PHOSPHOENOLPYRUVATE (PEP) CARBOXYKINASE increased during fruit ripening and was negatively correlated with malate concentration, suggesting increased malate conversion to PEP, which supports anthocyanin production during fruit ripening. This was further supported by the co-upregulation of several anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes. Together, this study provides insights into important metabolic programs, and their underlying gene expression patterns during fruit development and ripening in blueberry.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-74929-w.

Keywords: Organic acid metabolism, Starch, Sucrose, Sugar metabolism, Quinate

Subject terms: Physiology, Plant sciences

Introduction

Carbon (C) metabolism is critical to supporting the growth and metabolic demands of a fruit during various stages of its growth and development. Fruit photosynthesis supports only a relatively small part of the C requirements during its growth. For example, 10–15% of the C requirements during fruit growth and development in blueberry are supported by fruit photosynthesis, while the majority is fulfilled by C import from source tissues such as the leaf1. Thus, the fruit is a largely heterotrophic sink organ and substantially dependent on translocated sugars for synthesizing structural carbohydrates such as cell wall components, and non-structural carbohydrates such as starch and sugars, and to support its growth and maintenance metabolism requirements2. Sucrose (Suc) is the primary translocated sugar in many fruits like tomato, grape, strawberry, and banana3,4, while sorbitol (Sor) is the major translocated sugar in some fruits such as apple5. In plants that translocate Suc, unloaded Suc from the phloem can enter the sink tissue symplastically via plasmodesmata, or apoplastically following unloading into the cell wall/intercellular spaces and transport mediated by Suc transporters3,6,7. Alternatively, Suc can be metabolized in the apoplastic space into glucose (Glc) and Fructose (Fru) by cell wall invertases (cwINV) and transported into the cytosol via hexose transporters. In the sink cell cytosol, Suc can be hydrolyzed by cytosolic invertases (cINV), also known as neutral invertases (nINV) into Glc and Fru, or by sucrose synthase (SuSy) into Fru and UDP-Glc. Cytosolic Suc can also be transported into vacuoles and stored as such or following its metabolism by vacuolar invertases (vINV) into hexose sugars3,8. Consistently, acid invertases and SuSy are important contributors to determining sink strength2,9–12.

Following Suc catabolism, central C metabolism, via pathways such as glycolysis, pentose-phosphate pathway, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and the mitochondrial electron transport chain (mETC), allows for the synthesis of energy as ATP, and of multiple metabolic precursors. It is also the primary route for synthesis of organic acids that accumulate within fruits, such as malate, citrate, quinate, and shikimate, as well as multiple amino acids13. Sucrose catabolism and subsequent metabolism also allow for the synthesis of multiple cell wall components such as cellulose, cross-linking glycans and pectin14. It provides precursors for the synthesis of fatty acids, and secondary metabolites such as flavonoids and pigments15. Also, in some fruits, Suc metabolism contributes substantially to transitory starch synthesis and accumulation during early-mid fruit development. This transitory starch is often catabolized during late fruit development, thereby serving as a significant source of metabolized C in ripe fruit16,17.

Growth and metabolic demands vary across fruit development. Metabolic plasticity involving transitions in metabolic programs or metabolic re-programming during fruit development is essential to meet such varying demands18. One of the major metabolic transitions during fruit development is associated with the onset of ripening15,19,20. Previous studies have investigated metabolite compositions during fruit ripening-related transitions in multiple fruits such as tomato21, peach22, strawberry23, and grape24. These studies have identified a few common themes across these fruit types. Often, the major sugars accumulating in the fruit include Glc, Fru, and Suc, while the major acids are malate and citrate25. However, the patterns of accumulation of these sugars and acids appear to be fruit-type specific and reflect the metabolic shifts during ripening16,20,26,27. Metabolic re-programming allows for differential C allocation across various metabolic routes within the maturing fruit, thereby supporting the range of biochemical and textural changes associated with ripening.

A characteristic feature associated with the onset of ripening in some fruits such as tomato, apple, peach and banana, is the large increase in the rate of respiration, often referred to as the respiratory climacteric. Fruits that display a respiratory peak at the onset of ripening are termed as being climacteric28. A respiratory climacteric however is not observed in some fruits such as strawberry and grape, which therefore display non-climacteric ripening behavior28–30. Recently, research from our laboratory demonstrated that blueberry (rabbiteye and southern highbush species) fruit display atypical climacteric responses31. As in climacteric fruits, onset of ripening in blueberry fruit is associated with an increase in the rate of respiration as well as an increase in ethylene evolution. Particularly, the rate of respiration noted in blueberry fruit is comparable or greater than that noted in well-characterized climacteric fruits31. However, unlike in climacteric fruits, increase in ethylene evolution is not auto-catalytic, and is developmentally controlled, supporting its classification as an atypical climacteric fruit. Metabolic plasticity associated with the onset of such an atypical climacteric ripening program remains poorly characterized. Characterization of metabolic transitions during ripening in blueberry may therefore allow for deeper insights into fruit respiratory climacteric responses. Hence, the primary objectives of this study were to elucidate the molecular and metabolic programs in rabbiteye blueberry fruit during development and ripening. To this end, metabolite accumulation was quantified during multiple stages of fruit development and associated with changes in the transcriptome across different blueberry genotypes.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Fruit samples were collected from two rabbiteye cultivars, Premier and Powderblue, in 2020 from plants grown at the Durham Horticulture Farm, Athens, GA. Fruit were collected from five developmental stages: S4, S5, S6, S7, and S8 based on Zifkin, et al.32. Stages S4 and S5 were collected based on fruit size (S4: < 9 mm; and S5: 9–13 mm in diameter). Stages S6, S7, and S8 were collected based on fruit color (S6: 25–50% light pink peel; S7: predominantly light to dark pink peel with some blue; and S8: blue peel) (Fig. 1A). Stages S4 and S5 represent mid-fruit development. Ripening initiates at the S6 stage beginning with blue coloration at the calyx-end of the fruit. Stages S7 and S8 represent ripening progression with fully blue fruit formed by the S8 stage.

Figure 1.

Representative fruit from the developmental stages S4 to S8 showing transverse section (top panel), the pedicel-end (middle panel) and the calyx-end (bottom panel) of the fruit from ‘Powderblue’ (A). Stages S4 and S5 were collected based on fruit size (S4: < 9 mm; and S5: 9–13 mm in diameter). Stages S6, S7, and S8 were collected based on fruit color (S6: 25–50% light pink peel; S7: predominantly light to dark pink peel with some blue; and S8: blue peel). Fruit weight (B), Fruit diameter (C), Carbon dioxide (CO2; D) evolution, and Ethylene evolution (E) during the fruit developmental stages. Values are mean ± S.E. (n = 4). Different letter indicates significant differences in fruit development stages within a given cultivar, according to Fisher’s LSD (α = 0.05).

Fruit diameter and weight were measured using digital calipers and a precision weighing balance, respectively. Ethylene evolution and respiration rate were measured as described previously31. The experimental design was completely randomized design with four replications. All samples were frozen in liquid N2 and stored at -80 °C until further analysis.

Metabolite analysis

Sugars, acids, and amino acids were extracted according to Beshir, et al.33, with some modifications. Frozen fruit tissues were ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle in liquid N2. 125–150 mg of ground fruit tissue was extracted in 1.5 mL methanol containing 0.125 mg/mL of phenyl-β-D-glucoside as an internal standard. Methanol extracts were centrifuged at 22,000 g for 30 min at 4 ℃ and 100 µL of supernatant was transferred into a 300 µL glass insert (Insert glass flat bottom, Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ, USA) placed in a 2 mL gas chromatography (GC) vial (SureSTART vial, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA). The solvent was evaporated using a dry bath set at 45 ℃ under a constant flow of nitrogen gas. Subsequently, samples were derivatized by methoxymation followed by silylation. To achieve this, 50 µL of methoxamine (20 mg methoxamine in 1 mL pyridine) was added to each sample and heated at 50 ℃ for 30 min. Then, 100 µL of N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) + 1% trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) was added to each sample and heated at 50 °C for 30 min. Finally, 1 µL of derivatized sample was used to quantify metabolites on a gas chromatograph (GC-2014, Shimadzu, Japan).

Initially, metabolites were identified using an Agilent GC equipped with a quadrupole mass spectrometer (GC-MS, 6890 GC with 5973 MSD, Santa Clara, CA), using a small subset of samples. Subsequently, all samples were analyzed on a GC-Flame Ionization Detector (GC-FID) (GC-2014; Shimadzu, Japan) using a HP-5 fused capillary column (J&W Scientific, Fulsom, CA, USA) following the same method developed for the GC-MS. Helium was used as the carrier gas. Samples were injected using a split ratio of 20:1. The program of the GC was set as follows: 120 °C for 1 min, ramped at 4 °C per min to 180 ℃, held for 0.5 min at 180 °C, ramped at 0.5 ℃ per min to 185 ℃, held for 0.5 min at 185 ℃, ramped at 1 ℃ per min to 210 ℃, held for 0.5 min at 210 ℃, ramped at 10 °C per min to 260 °C, and finally held for 12 min at 260 °C. For metabolite quantification, a separate set of standard solutions was prepared for each of the identified metabolites. The standards were extracted and derivatized as described above and analyzed on the GC-FID. Standard curves generated individually for each metabolite were used for quantification and are presented as concentration on a fresh weight basis. The total amount of a given metabolite per fruit was calculated by multiplying the concentration of metabolite at that stage by the average fruit fresh weight.

Starch quantification

Fruit collected from the five developmental stages from 2020 as described above from the two cultivars were used. In addition, leaf, and fruit samples from S4, S5, and S6 stages from ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’ were collected at 9:00 am, 2:00 pm, and 7:00 pm in 2021. All samples were frozen in liquid N2, stored at -80 ℃, and subsequently ground as described above. Starch quantification was performed following the protocol in Smith and Zeeman34 with some modifications. Around 80–100 mg of finely ground tissue was extracted in 80% of 1.5 mL ethanol in a 2 mL tube with a snap lock-lid by incubation at 80 ℃ for 10 min, followed by centrifugation for 5 min at 12,500 g. The resulting supernatant was discarded and the above steps were repeated twice to ensure removal of all soluble sugars. Subsequently, 500 µL of autoclaved water was added to the pellet and samples incubated at 100 ℃ for 10 min. 500 µL of 35 units of amyloglucosidase was added, and samples were mixed using a shaker (HL-2000 HybriLinker, Analytik Jena, Upland, CA, USA) at 150 g for 24 h at 55 ℃. Finally, 25 µL of supernatant was mixed with 975 µL of buffer (0.1 M HEPES, 0.5 mM ATP, 1 mM NAD, 4 mM MgCl2). Development of NADH during the conversion of Glc to 6-phosphogluconolactone (catalyzed by the addition of hexokinase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) was measured at 340 nm using a spectrophotometer (GENESYS 10 S UV-VIS, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A standard curve generated from known quantities of Glc was prepared for quantification of starch in Glc equivalents.

Anthocyanin determination

For anthocyanin quantification, the protocol based on Downey and Rochfort35, was used with some modifications. Around 100–125 mg of sample was extracted in 1 mL of 50% (v/v) methanol. Samples were left undisturbed in the dark for 1 h, followed by sonication using a Bransonic 220 ultrasonic water bath (Marshall Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA) for 20 min. Samples were centrifuged at 22,000 g for 10 min at room temperature and the supernatant was purified through a 0.45 μm filter and transferred into a 2 mL GC vial. The injection volume was 30 µL.

Anthocyanins were initially identified and determined using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) at the Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Facility, University of Georgia. The elution times, m/z (mass/charge) ratios, and fragmentation of anthocyanin molecules are presented in Table S1. Compound identification was performed by comparing the m/z ratio and their fragmentation to previously published articles36,37. Anthocyanins accumulate during ripening initiation beginning from the S6 stage of development. A subset of samples (two replications) from S4 and S5 stages from the two cultivars were also analyzed. Since no anthocyanins were detected from these two stages, further analyses were performed on S6-S8 stages of fruit development.

Samples were analyzed on a high-performance liquid chromatography (HLPC) coupled with a photodiode array detector (PAD) (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). For both, LC-MS/MS and HPLC analyses, the same method, column, and flow rate were used. The discovery C-18 column (15 cm x 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Sigma-Aldrich Inc, ST. Louis, MO, USA) was used for this study. Two mobile phases were used: first 10% formic acid in water (Solvent A) and second 10% formic acid in methanol (Solvent B), with a 1 mL per min flow rate. The gradient flow rate was maintained as follows: 0 min, 10% B; 14 min, 12% B; 25 min, 16% B; 28 min, 25% B; 32 min 50% B; 35–38 min, 10% B. The HPLC chromatogram was recorded at 520 nm. A standard curve developed using various concentrations of malvidin-3-O galactoside (Mal 3-gal) was used for quantification of all anthocyanins. Total anthocyanin content was calculated as the sum of all anthocyanins identified.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis and gene ontology analysis

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was performed using differentially expressed genes (DEGs) obtained from a previous study38 from the authors’ laboratory, and selected metabolites determined in this study. For RNA Sequencing, fruit samples from the ‘Powderblue’ cultivar at the S4/S5 (pool of S4 and S5; Immature fruit), S6, S7, and S8 stages were used. Differentially expressed genes between each pair of fruit developmental stages were identified by employing a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of < 0.01 and a fold change cut-off of ≥ 2. Metabolites including Suc, Glc, Fru, starch, malate, citrate, quinate, shikimate, and total anthocyanin were selected based on their abundance during different fruit developmental stages. Since all anthocyanin compounds exhibited similar patterns during fruit development and ripening, only total anthocyanin content was used for WGCNA. Starch, although present in low concentrations, was used in this analysis owing to its significance in fruit carbohydrate metabolism and fruit ripening. For S4 and S5 stages, the average values of the metabolite concentration at these stages were used for the analysis. Using the DEGs, the stepwise network construction method was used for module detection. A soft threshold power of 20 was selected. The merge dynamic method was used for final module construction by cutting the height of 0.25 from the dynamic tree cut39. Analyses of correlation between the modules and the metabolites were performed using the function corAndPvalue from the ‘WGCNA’ package39. Correlation coefficients ≥ 0.80 (positive correlation) or ≤ -0.80 (negative correlation) and associated P-values < 0.05 were considered as significant. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed specifically using the WGCNA modules highly correlated with specific metabolites, using the AgriGO v2.0 tools40. The P-values were corrected using the FDR and GO terms with FDR < 0.05 were considered significantly enriched. Visualization of GO enrichment was performed using R-studio (R core 2023, Vienna, Austria).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Transcript abundance of sugar, acid, and anthocyanin-related genes was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) as described below. Total RNA was extracted using the modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method described previously41. After treatment with DNase, complimentary DNA (cDNA) was prepared using reverse transcriptase from 1 µg of total RNA. qRT-PCR analyses were performed using the PowerUP SYBR green master mix (ThermoFisher, United States) on the MX3005P quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) instrument (Agilent Technologies, United States). All genes used in this study were identified from a fruit transcriptome generated previously in our laboratory with the cultivar ‘Powderblue’42. The list of genes, and primers used for this study is presented in Table S2. Three reference genes were used for normalization of target gene expression: UBIQUITIN-CONJUGATING ENZYME (UBC28), RNA HELICASE-LIKE (RH8), and CLATHRIN ADAPTER COMPLEXES MEDIUM SUBUNIT FAMILY PROTEIN (CACSa). The mean PCR efficiency of each primer was calculated using LinReg PCR43. Relative quantity (RQ) values were calculated after PCR efficiency correction. To calculate normalized RQ values (NRQ) for a specific sample, the RQ values of that sample were normalized using the geometric mean of the RQ values from the three reference genes. Standard error was determined as described by Rieu and Powers44. NRQ values were used for statistical data analysis after log2 transformation. Relative expression of all genes is presented as fold change with reference to the transcript abundance of the given gene at the S4 developmental stage in ‘Powderblue’.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed and visualized using the R-studio 2023 (R core 2023, Vienna, Austria). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the significance of treatment effects. Multiple comparison tests were performed using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) at the 0.05 significance level. Principal components analysis (PCA) was performed using the FactoMineR and Factoextra software in R-studio. Contributions of the first two principal components, loading, and scree plots, are presented in this manuscript.

Results

Physiological characteristics of developing blueberry fruit

Fruit weight and diameter increased from the S4 to S5 stage by 2.3- and 1.4-fold in ‘Premier’, and 1.5- and 1.2-fold in ‘Powderblue’, respectively (Fig. 1B, C). Fruit weight and diameter remained similar during the S5 to S7 stages, except in ‘Premier’, where S6 fruit had slightly higher weight and diameter than S5 fruit (Fig. 1B, C). Subsequently, weight and diameter of fruit transitioning from the S7 to S8 stage increased by 1.5- and 1.1-fold in ‘Premier’ and 1.7- and 1.2-fold in ‘Powderblue’, respectively. ‘Premier’ had greater fruit weight and diameter than ‘Powderblue’ (Fig. 1B, C).

Respiration and ethylene evolution were similar at the S4 and S5 developmental stages (Fig. 1D, E). Between S6 and S7 stages, CO2 evolution increased by 1.6- and 1.5-fold in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’, respectively (Fig. 1D). Similarly, ethylene evolution increased from S6 to S8, by 2.1- and 1.8-fold in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’, respectively (Fig. 1E). Respiration rates were similar between ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’, however ethylene evolution was higher by 5.6-fold in ‘Premier’ than in ‘Powderblue’.

Association between metabolite composition and fruit development

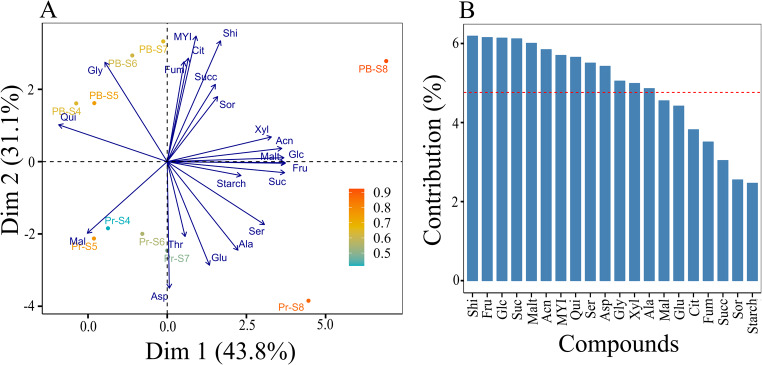

To determine the contribution of metabolites to fruit development and ripening across the two cultivars, PCA was performed (Fig. 2, Fig. S1). Overall, 74.9% of the variation in data was explained by the first two dimensions (Fig. 2A). Dimension 1 captured the variation across the developmental stages, where S4 to S8 stages displayed greater separation. Malate and quinate were mainly clustered with the S4 and S5 stages. In contrast, the major sugars and total anthocyanin were clustered with the S8 stage. Dimension 2 mainly revealed separation between the cultivars, ‘Powderblue’ and ‘Premier’ (Fig. 2A). Analysis of the loading plots indicated the contribution of each metabolite to the first two PCs (Fig. 2B). Most of the metabolites accounted for over 5% of the variance in the first two PCs, with the exception of malate, glutamate, citrate, fumarate, succinate, sorbitol, and starch, which contributed less than 5% each (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis (PCA) during fruit development and ripening (A). PCA biplot showing separation of metabolites across five developmental stages (S4-S8) in two cultivars, Premier (Pr) and Powderblue (PB) in the first two components. Glc: glucose, Fru: fructose, Suc: sucrose, Mal: malate, Asp: aspartate, Glu: glutamate, Cit: citrate, Qui: quinate, MYI: myo-inisitol, Ala: alanine, Succ: succinate, Gly: glycerate, Fum: fumarate, Ser: serine, Thr: threonine, Xyl: xylose, Sor: sorbitol, Malt: maltose, Shi: shikimate, Acn: Total anthocyanin. The color gradient legend is the relative representation of each developmental stage in the first two PCs with blue being low and orange being high representation. Contribution of each metabolite in the first two PCs (B). Red dashed line in B represents the 4.76% contribution level in the first two PCs.

The relationships among all metabolites were analyzed using Pearson’s correlations. Major sugars (Suc, Fru, Glc) were highly positively correlated with each other in both cultivars with correlation coefficients (r) ranging from 0.98 to 1.0 (Table S3). The sugars were negatively correlated with major acids, malate (r = − 0.80 to -0.87) and quinate (r =-0.87 to -0.95) (Table S3). Malate and quinate were positively correlated. No strong correlations (r > 0.80) were detected between starch and the major sugars (Glc, Fru, and Suc) in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’ (Table S3). Citrate was not correlated with any of the major sugars or acids (Table S3). Total anthocyanin was positively correlated with sugars (r = 0.85 to 0.94) and negatively correlated with malate (r =-0.91 in ‘Premier’, and r =-0.87 in ‘Powderblue’) (Table S3).

Changes in metabolite composition during fruit development

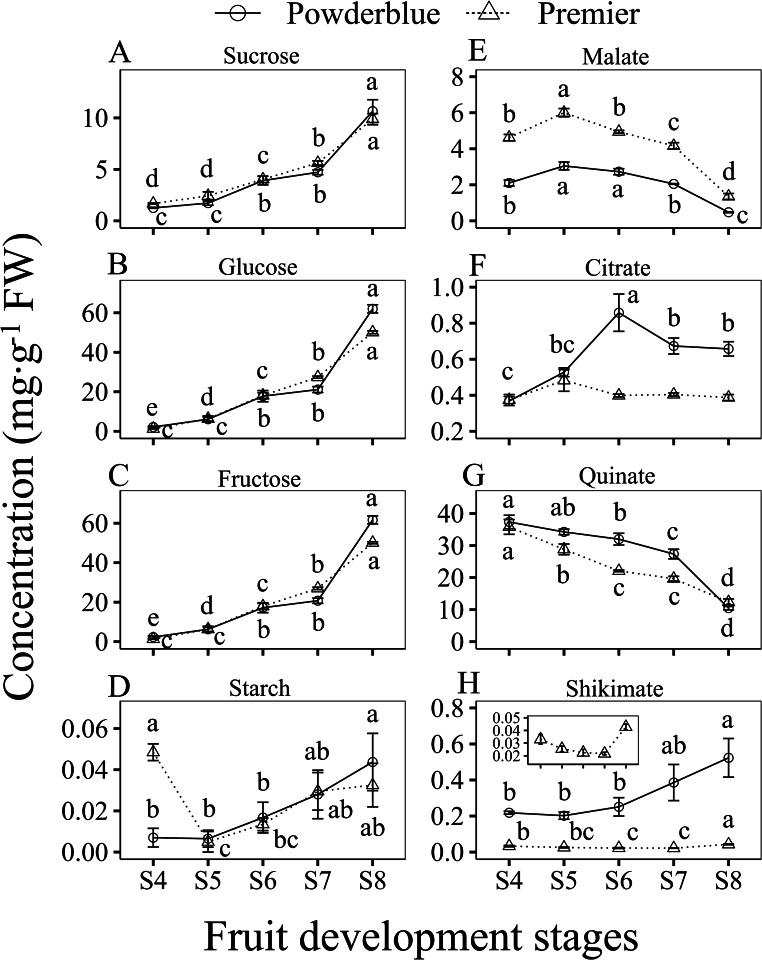

The patterns of sugar concentration during fruit development were similar in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’ (Fig. 3A-C). Overall, the concentrations of Suc, Fru, and Glc increased from the S4 to S8 stages by 5.9-, 40.0-, and 37.6-fold in ‘Premier’, and 8.5-, 28.7-, and 26.4-fold in ‘Powderblue’, respectively. The concentration of the three sugars increased steadily during mid-fruit development to early ripening (S4 to S7), then increased rapidly at later stages of ripening (S7 to S8). Sucrose, Fru, and Glc concentration increased from S7 to S8 by 1.8-, 1.9-, and 1.8-fold in ‘Premier’ and 2.3-, 3.0-, and 2.9-fold in ‘Powderblue’ (Fig. 3A-C). The total amounts of Suc, Fru, and Glc per fruit, followed a pattern similar to that of their concentrations, with all three sugars increasing during fruit development and ripening (Fig. S2A-C). Other sugars such as xylose and maltose, and sugar alcohols such as myo-inositol and Sor were detected, but displayed much lower concentrations (Fig. S4A-D). Of these, in general, xylose increased between S4 to S6 and maltose between S7 to S8 stages in both cultivars (Fig. S4B, D).

Figure 3.

Concentration of Sucrose (A), Glucose (B), Fructose (C), Starch (D), Malate (E), Citrate (F), Quinate (G), and Shikimate (H) from S4 to S8 development stages in two cultivars, Premier (dashed line with triangle) and Powderblue (solid line with circle). Inset in ‘H’ displays changes in shikimate concentration in ‘Premier’ on a different Y-axis scale for clarity. Values are mean ± S.E. (n = 4). Different letters above symbols indicates significant differences in fruit development stages within given cultivars according to Fisher’s LSD (α = 0.05).

Overall, the concentration of starch was very low throughout development, with concentrations of 0.035 mg/g FW in ‘Premier’ and 0.044 mg/g FW in ‘Powderblue’ at the S8 stage (Fig. 3D). The amount of starch per fruit was low but increased slightly during ripening in both cultivars (Fig. S2D). As starch concentration may be diurnally variable, starch measurements were performed from fruit at S4, S5, and S6 stages at three time points during the day (9:00 am, 2:00 pm and 7:00 pm) in the two cultivars (Fig. S3A-C). However, very low starch concentrations were noted at these fruit development stages across different times of the day. In the leaf, starch concentration steadily increased during the day, reaching a maximum value at 2:00 pm and 7:00 pm in ‘Premier’ and at 7:00 pm in ‘Powderblue’ (Fig. S3D). In comparison to 9:00 am, the leaf starch concentrations increased by 2.0 and 2.1-fold in ‘Premier’ and by 10.1 and 17.3-fold in ‘Powderblue’ at 2:00 pm and 7:00 pm, respectively.

Malate, citrate, quinate, and shikimate were the major acids detected in the two blueberry cultivars (Fig. 3E-H). Among them, quinate was the predominant acid throughout fruit development, including in ripe fruit. During mid to late fruit development stages (S4 to S7), malate concentration surpassed that of citrate in both cultivars, while at stage S8, malate concentration was 3.5-fold greater in ‘Premier’ and citrate concentration was 1.4-fold greater in ‘Powderblue’ (Fig. 3E, F). The overall patterns of the concentration of organic acids during fruit development were similar in both cultivars. The concentrations of malate increased from S4 to S5 stages by 1.3- and 1.5-fold in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’, respectively, and subsequently continued to decline during later stages of fruit development in both cultivars (Fig. 3E). In ‘Premier’, malate concentration decreased by 1.2-, 1.2-, and 3.1-fold between S5 to S6, S6 to S7, and S7 to S8 stages, respectively. Similarly, in ‘Powderblue’, malate decreased by 1.3- and 4.3-fold between S6 to S7, and S7 to S8 stages, respectively. The concentration of citrate was similar in ‘Premier’ at all stages of fruit development analyzed in this study. In ‘Powderblue’, citrate concentration was highest at the S6 stage, increased by 1.6-fold from S5 to S6, then declined by 1.3-fold between S6 and S7, and remained similar between S7 and S8 stages (Fig. 3F). The concentration of quinate continuously decreased, whereas that of shikimate increased during fruit development and ripening (Fig. 3G, H). Quinate decreased by 1.2-, 1.3-, and 1.6-fold between S4 to S5, S5 to S6, and S7 to S8 stages respectively in ‘Premier’. Similarly, it decreased by 1.2-fold between S4 to S6, and S6 to S7, and by 2.6-fold between S7 to S8 stages, in ‘Powderblue’. On the other hand, shikimate increased by 1.9- and 2.1-fold between S6 to S8 stages in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’, respectively.

The amount of malate per fruit increased by 3.0-fold from S4 to S5, then remained similar till the S7 stage, after which it decreased by 2.1-fold in ‘Premier’ (Fig. S2E). In ‘Powderblue’, it increased by 2.2-fold from S4 to S5 stage, remained similar till S6, and decreased by 1.2- and 2.5-fold between S6 to S7 and S7 to S8 stages, respectively (Fig. S2E). The amount of citrate per fruit increased during ripening with 1.4- and 1.7-fold greater abundance in S8 fruit compared to S7 fruit in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’, respectively (Fig. S2F). In case of quinate, the amount increased by 1.9- and 1.4-fold between S4 and S5 in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’, respectively (Fig. S2G). It remained similar in ‘Premier’ from S5 to S8 stages. In ‘Powderblue’ it was similar from S5 to S7, and thereafter decreased by 1.5-fold between S7 and S8 stages. The amount of shikimate per fruit increased during fruit ripening, and the pattern was similar to that of its concentration (Fig. S2H). In addition, we also detected other organic acids such as succinate (both cultivars), fumarate (only in ‘Powderblue’), and glycerate (both cultivars) at very low concentrations (Fig. S4E-G).

Glutamate and aspartate were the major amino acids detected during fruit development and ripening. The concentration of glutamate remained similar at S4, S5, and S6 stages, then it increased by 1.2- and 1.4-fold from S6 to S7 and S7 to S8 stages, respectively, in ‘Premier’ (Fig. S4H). In ‘Powderblue’, glutamate concentration was similar at S4 and S5 stages, increased by 1.3-fold from S5 to S6, and then remained similar during later stages of fruit development. The concentration of aspartate was not different during fruit development and ripening in both cultivars (Fig. S4I). Overall, alanine, serine, and threonine concentrations at the S8 stage were very low being, 0.023, 0.04, and 0.015 mg/g FW in ‘Premier’, and 0.009, 0.029, and 0.014 mg/g FW in ‘Powderblue’, respectively (Fig. S4J-L).

At the S6 developmental stage, only one anthocyanin (Cyanidin 3-galactoside; Cya 3-gal) was detected in ‘Premier’ and three different anthocyanins (Cya 3-gal, Petunidin 3-galactoside/Cyanidin 3-arabinoside (Pet 3-gal/Cya 3-ara) were detected in ‘Powderblue’ (Table 1). At the S7 stage, seven different anthocyanin compounds (Cya 3-gal, Pet 3-gal/Cya 3-ara, Peonidin 3-galactoside (Peo 3-gal), Mal 3-gal, Peonidin 3-arabinoside (Peo 3-ara), and Malvidin 3-arabinoside (Mal 3-ara) were detected in ‘Premier’, whereas 10 were detected in ‘Powderblue’, with the three additional ones being Cyanidin 3-glucoside (Cya 3-glu), Peonidin 3-glucoside (Peo-3-glu), and Malvidin 3-glucoside (Mal 3-glu) (Table 1). At the S8 stage, 15 different anthocyanin compounds were detected. Concentration of anthocyanins was higher at the S8 stage compared to their respective concentrations at the S6 and S7 developmental stages. Mal 3-gal was the most abundant anthocyanin compound present in both cultivars. The total anthocyanin concentration in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’ increased between S7 to S8 stages by 24.1-fold in ‘Premier’, and 25.9-fold in ‘Powderblue’, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Concentrations of anthocyanin at different developmental stages in blueberry.

| Anthocyanin | ‘Premier’ (mg/100 g FW) | P-value | ‘Powderblue’ (mg/100 g FW) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S6 | S7 | S8 | S6 | S7 | S8 | |||

| Del 3-gal | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 16.60 ± 3.39 a | 0.0014 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 18.58 ± 1.88 a | <0.0001 |

| Del 3-glu | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.28 ± 0.12 a | 0.0453 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 9.75 ± 0.92 a | <0.0001 |

| Cya 3-gal | 0.40 ± 0.08 c | 1.93 ± 0.19 b | 14.85 ± 0.67 a | <0.0001 | 0.53 ± 0.14 b | 3.10 ± 0.92 b | 25.95 ± 2.87 a | 0.0001 |

| Del 3-ara | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 6.48 ± 1.34 a | 0.0015 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 11.35 ± 0.85 a | <0.0001 |

| Cya 3-glu | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.55 ± 0.06 a | <0.0001 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 1.03 ± 0.37 b | 14.15 ± 1.59 a | <0.0001 |

| Pet 3-gal & Cya 3-ara | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 1.00 ± 0.12 b | 21.03 ± 1.61 a | <0.0001 | 0.25 ± 0.05 b | 1.53 ± 0.46 b | 28.15 ± 2.05 a | <0.0001 |

| Pet 3-glu | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.38 ± 0.06 a | 0.0005 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 13.05 ± 0.87 a | <0.0001 |

| Peo 3-gal | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.50 ± 0.04 b | 6.63 ± 0.60 a | <0.0001 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.38 ± 0.14 b | 8.05 ± 0.39 a | <0.0001 |

| Pet 3-ara | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 5.5 ± 0.49 a | <0.0001 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 7.60 ± 0.38 a | <0.0001 |

| Peo 3-glu | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 1.10 ± 0.11 a | <0.0001 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.65 ± 0.19 b | 13.28 ± 0.70 a | <0.0001 |

| Mal 3-gal | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 1.15 ± 0.12 b | 34.15 ± 3.44 a | <0.0001 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.83 ± 0.24 b | 30.95 ± 0.80 a | <0.0001 |

| Peo 3-ara | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.18 ± 0.03 b | 1.68 ± 0.22 a | 0.0001 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.20 ± 0.04 b | 2.80 ± 0.11 a | <0.0001 |

| Mal 3-glu | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 1.60 ± 0.15 a | <0.0001 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.58 ± 0.18 b | 28.63 ± 0.77 a | <0.0001 |

| Mal 3-ara | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.40 ± 0.04 b | 11.85 ± 1.13 a | <0.0001 | 0.00 ± 0. 00 b | 0.45 ± 0.12 b | 16.13 ± 0.42 a | <0.0001 |

| Total Acn | 0.40 ± 0.08 b | 5.08 ± 0.49 b | 122.65 ± 10.33 a | <0.0001 | 0.75 ± 0.17 b | 8.83 ± 2.59 b | 228.40 ± 13.43 a | <0.0001 |

The data expressed as mean ± S.E. Different letters in each row per cultivars are significantly different according to Fischer’s LSD (α=0.05)

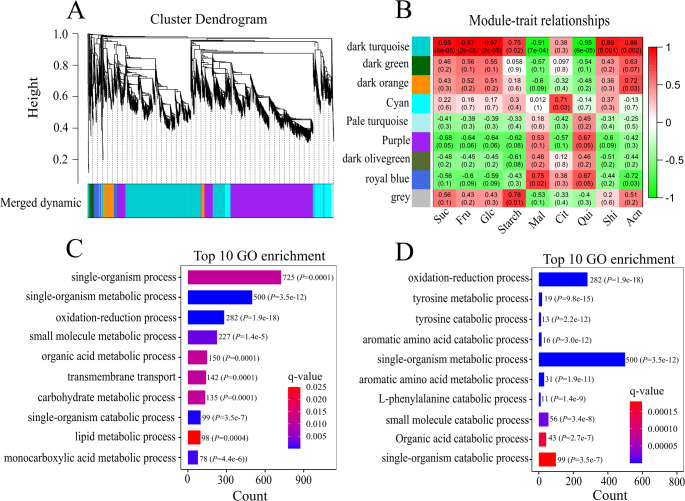

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis and gene ontology enrichment analysis

WGCNA using the ‘Powderblue’ fruit ripening transcriptome38, identified 9 modules (Fig. 4A). The majority of genes (40.8%) were assigned to the purple module, followed by the dark turquoise module (37.9%), whereas the grey (0.05%) and pale turquoise modules (0.89%) contained fewer genes (Fig. S5, Table S4). Correlation analysis among all modules and major metabolites revealed that the dark turquoise model was positively correlated with Suc (r = 0.95, P = < 0.0001), Fru (r = 0.97, P = < 0.0001), Glc (r = 0.97, P = < 0.0001), shikimate (r = 0.89, P = 0.001), and total anthocyanin (r = 0.88, P = 0.002) concentrations (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the dark turquoise model was negatively correlated with malate (r = -0.91, P ≤ 0.0001) and quinate (r = -0.95, P ≤ 0.0001) concentrations (Fig. 4B). The GO enrichment analysis of genes contained in the dark turquoise module revealed that the top 10 GO enrichment terms according to the number of genes present included single organism metabolic process, oxidation-reduction process, small molecule metabolic process, organic acid metabolic process, and carbohydrate metabolic process (Fig. 4C, Table S5). When ranked according to significance (lowest q- value), some of the top 10 GO enrichment terms included genes related to the oxidation-reduction process, aromatic amino acid metabolic and catabolic process (tyrosine metabolic and catabolic process, phenylalanine metabolic process), and organic acid catabolic process (Fig. 4D). The single-organism metabolic, oxidation-reduction, and aromatic amino acids metabolic process included genes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway, and the former two GO categories also included genes related to sugar, starch, and organic acid biosynthesis (Table S5-S8).

Figure 4.

Gene cluster dendrogram (A) based on weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) of differentially expressed genes from the ‘Powderblue’ fruit transcriptome during development and the ripening stages IMG (pool of S4 and S5 fruit); Green (S6), Pink (S7) and Ripe (S8)38. Hierarchical cluster displaying the nine modules shown in nine different colors of differentially expressed genes during fruit development and ripening. Module-trait relationships (B) showing associations between modules (presented as nine colors along the Y-axis) and targeted metabolites along the X-axis according to the Pearson’s correlation (P < 0.05). Suc: sucrose, Fru: fructose, Glc: glucose, Mal: malate, Cit: citrate, Qui: quinate, Shi: shikimate, Acn: Total anthocyanin. The top 10 biological processes as per Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the dark turquoise module from WGCNA (C, D). Results are presented according to the highest number of genes present within a process (C) and most significant based on lowest q-value (D).

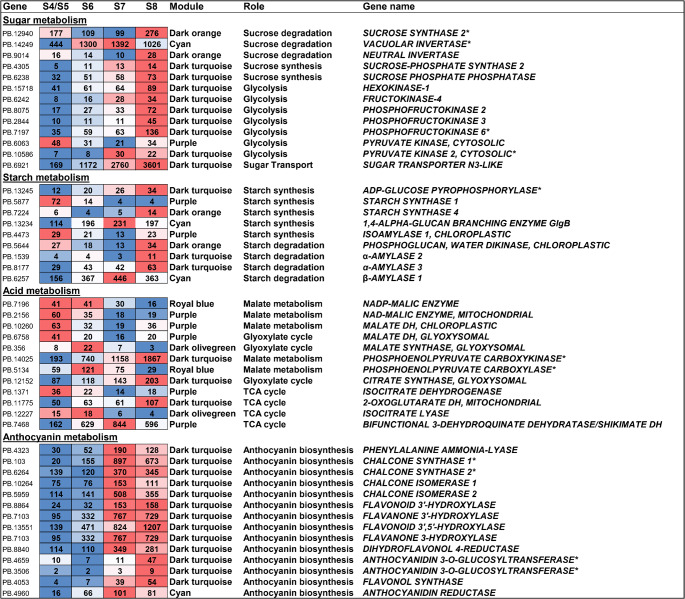

Expression analyses of genes involved in sugar, starch, acid, and anthocyanin metabolism

Since WGCNA suggested genes involved in the carbohydrate metabolic and aromatic amino acid metabolic processes to be highly correlated with targeted metabolites, we performed a comprehensive analysis to identify genes related to sugar, acid and anthocyanin metabolism. From the ‘Powderblue’ ripening transcriptome38, we identified differentially expressed genes associated with sugar metabolism and transport, glycolysis, malate metabolism, TCA cycle, glyoxylate cycle, and anthocyanin biosynthesis (Fig. 5, Table S6-S9).

Figure 5.

Heat map showing transcript abundance of sugar, starch, acid, and anthocyanin metabolism-related genes during fruit development and ripening from four stages (pool of S4 and S5, and S6, S7, and S8). The numbers in the heat map indicate trancript per million (TPM) values from the ‘Powderblue’ transcriptome38 with a blue to red gradient indicating a low to high TPM value. The different colored modules represents the inclusion of genes within the respective module based on weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). The transcript abudance of genes validated using qRT-PCR is indicated by asterisk after the gene name.

Enzymes involved in Suc degradation were most abundantly expressed in the S8 stage compared to the S4/S5 stage with the exception of vINV that was expressed more abundantly at the S6 and S7 stages compared with other stages, based on the transcript per million (TPM) values (Fig. 5, Table S7). For genes related to Suc synthesis, glycolysis and sugar transport, transcript abundance increased during fruit ripening with maximum expression at the S8 stage, with the exception of PYRUVATE KINASE 2 (PK2, PB.10586) that displayed highest transcript abundance at S7 stage, while another SUGAR TRANSPORT PROTEIN (PB.12267) decreased during fruit development and ripening (Fig. 5, Table S7). Mostly these genes were also present in the dark turquoise module (Table S7). Of all genes related to sugar metabolism, two genes exhibited high transcript abundance: vINV (PB.14249/PB.10450), and SUGAR TRANSPORTER N3-like (PB.6921) displayed TPM values of around 1,300 and 3,600, respectively (Fig. 5, Table S7).

Only two genes coding for enzymes related to starch degradation, 1,4-α-GLUCAN BRANCHING ENZYME (GBE) (TPM, around 231), and β-AMYLASE 1 (TPM, around 446) showed high transcript abundance during ripening with maximal values at the S7 stage (Fig. 5, Table S6). All other starch degradation-related genes exhibited relatively low transcript abundance. STARCH SYNTHASE 1 (SS1) and ISOAMYLASE 1 showed higher expression at earlier developmental S4/S5 stage whereas ADP- GLUCOSE PYROPHOSPHORYLASE (AGPase), SS4, α-AMYLASE 2, and 3 were more abundant at the S8 developmental stage. Among these, AGPase and α-AMYLASE were found in the dark turquoise module (Fig. 5).

Of all the acid metabolism related genes, the transcript abundance of NADP-MALIC ENZYME (NADP-ME), mitochondrial NAD-ME, chloroplastic and glyoxysomal MALATE DEHYDROGENASE (MDH), ISOCITRATE DEHYDROGENASE (IDH), and ISOCITRATE LYASE (ICL) were higher in the S4/S5 stage compared to the S8 stage (Fig. 5). Conversely, the transcript abundance of PHOSPHOENOLPYRUVATE CARBOXYKINASE (PEPCK), glyoxysomal CITRATE SYNTHASE (CS), and 2-OXOGLUTARATE DH (ODH), were greater in the S8, and BIFUNCTIONAL 3-DEHYDROQUINATE DEHYDRATASE/SHIKIMATE DH (DHQD/SDH) at the S7 stage than in the S4/S5 stage (Fig. 5, Table S8). PHOSPHOENOLPYRUVATE CARBOXYLASE (PEPC) transcript abundance exhibited an increase from S4/S5 to S6 stage, followed by a decrease during the remaining stages (Fig. 5). Of all the acid metabolism related genes, PEPCK displayed highest transcript abundance (TPM of approximately 1,800) and was also included within the dark turquoise module (Fig. 5).

All major anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes were more abundantly expressed in the S7 and S8 developmental stages compared to earlier developmental stages (Fig. 5, Table S9). Additionally, all anthocyanin biosynthesis genes, except ANTHOCYANIDIN REDUCTASE (ANR), were represented within the dark turquoise module (Figs. 4B and 5, Table S9).

Validation of gene expression with qRT-PCR analysis

Transcript abundance of selected genes related to sugar, acid and anthocyanin metabolism were validated using qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 6). In general, qRT-PCR results were similar to that observed with the ‘Powderblue’ transcriptome analysis. Transcript abundance of SuSy2 increased from S4 to S5, then remained similar until S7 stage, and increased from S7 to S8 by 2.1-fold in ‘Powderblue’. However, in ‘Premier’, SuSy2 transcript abundance remained similar during fruit development (Fig. 6A). The relative expression of vINV increased by 4.1- and 15.8-fold in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’, respectively, from S4 to S5 stages, and thereafter remained similar in both cultivars during the remaining stages (Fig. 6B). The AGPase transcript abundance slightly increased from S4 to S5 stages and remained similar during later developmental stages in ‘Premier’ and with no difference in ‘Powderblue’ (Fig. 6C). Transcript abundance of the rate-limiting enzyme in the glycolysis pathway, PHOSPHOFRUCTOKINASE (PFK), increased by 1.7-fold (S7 stage) and by 3.2-fold (S8 stage), compared to the S4 stage in ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’, respectively (Fig. 6D). The transcript abundance of cytosolic PYRUVATE KINASE (PK) was similar during fruit development in ‘Premier’. However, it increased from S4 to S5 stages by 11.1-fold, then remained similar during the remaining developmental stages in ‘Powderblue’ (Fig. 6E).

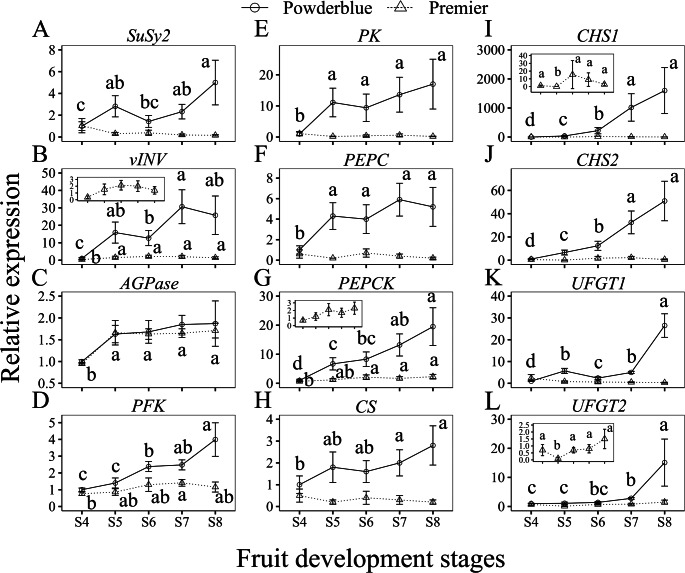

Figure 6.

Relative abundance of transcripts involved in sugar, acid, starch, and anthocyanin biosynthesis during the five stages of fruit development and ripening (S4 to S8) in two cultivars, Premier (dashed line with triangle) and Powderblue (solid line with circle). Inset displays changes in respective transcript abudance in ‘Premier’ on a different Y-axis scale for clarity. SUCROSE SYNTHASE 2 (SuSy2; A), VACUOLAR INVERTASE (vINV; B), ADP-GLUCOSE PYROPHOSPHORYLASE (AGPase; C), PHOSPHOFRUCTOKINASE (PFK; D), PYRUVATE KINASE (PK; E), PHOSPHOENOLPYRUVATE CARBOXYLASE (PEPC; F), PHOSPHOENOLPYRUVATE CARBOXYKINASE (PEPCK; G), CITRATE SYNTHASE (CS; H), CHALCONE SYNTHASE 1, 2 (CHS1, 2; I, J), ANTHOCYANIDIN 3-O-GLUCOSYLTRANSFERASE 1, 2 (UFGT1, 2; K, L). Values are mean ± S.E. (n = 4). Expression data for a given gene are presented relative to its expression in ‘Powderblue’ at the S4 stage of development. Different letters above symbols indicate that the means are significantly different across fruit developmental stages (within a cultivar) according to ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD (α = 0.05).

The transcript abundance of PEPC was similar during fruit development in ‘Premier’, but in ‘Powderblue’ its transcript abundance increased from S4 to S5 by 4.3-fold, then remained unchanged (Fig. 6F). In ‘Premier’, the transcript abundance of PEPCK increased by 3.0-fold from S4 to S6, and thereafter remained similar through the remainder of fruit development (Fig. 6G). In ‘Powderblue,’ the transcript abundance of PEPCK increased steadily and reached a maximum at the S8 stage (19.5-fold greater in S8 than S4) (Fig. 6G). The pattern of gene expression of mitochondrial CS was similar during fruit development in ‘Premier’. However, in ‘Powderblue’, it increased from the S4 to S5 stages by 1.8-fold, and then remained similar during later fruit development (Fig. 6H).

Among the anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes, the transcript abundance of CHALCONE SYNTHASE (CHS1, 2) and ANTHOCYANIDIN 3-O-GLUCOSYLTRANSFERASE (UFGT1, 2) were analyzed. In ‘Premier’, the transcript abundance of CHS1 decreased from S4 to S5, and then increased from S5 to S6 by 15.4-fold and thereafter remained similar during fruit ripening (Fig. 6I). The transcript abundance of CHS2 and UFGT1 were not significantly different across developmental stages in ‘Premier’ (Fig. 6J, K). Similar to CHS1, the expression of UFGT2 decreased by 7.0-fold from S4 to S5 stage, then increased by 7.0-fold from S5 to S6 in ‘Premier’ and remained similar during the rest of the stages (Fig. 6L). In ‘Powderblue’, the expression of CHS1, CHS2, UFGT1, and UFGT2 increased by 42.7-, 7.7-, 4.6-, and 13.7-fold from S5 to S8 stages (Fig. 6I-L).

Discussion

In the current study, the concentration of Suc, and its catabolism products, Fru and Glc, increased steadily during fruit ripening from the S4 to S7 stages. Interestingly, during the transition between S7 (fully Pink) and S8 (Ripe) stages, which represents ripening progression, the concentration of these sugars increased dramatically by 2-fold in ‘Premier’ and 2-3-fold in ‘Powderblue’. Increase in soluble sugar concentration during fruit development and ripening could potentially result from fruit photosynthesis, catabolism of stored C reserves or import from source organs. Fruit photosynthesis contributes significantly to fruit C requirements in blueberry but declines during later stages of fruit development38,45, suggesting that its contribution to the increase in sugar concentrations during ripening is limited. Breakdown of C stored in the form of starch reserves during later stages of fruit development is a significant contributor to increase in sugar concentration in many fruits such as tomato and apple17,46–48. However, in this study, we demonstrate that starch does not accumulate to appreciable levels in the blueberry fruit, at least from the S4 stage of fruit development, and is therefore unlikely to serve as a significant source for synthesis and accumulation of simple sugars during later stages of development. Other potential C storage forms such as the major organic acids, malate and quinate, did not display a decline in concentration or amount during later stages of fruit development equivalent to the increase in sugar concentration and amount. Hence, continuous import of C (likely as Suc) from source organs (leaves) occurs during most of fruit development, including during ripening progression, thereby allowing for the sustained increase in Suc, Fru and Glc concentrations and amounts in the blueberry fruit. These results also suggest that blueberry fruit harvested at the fully ripe stage will display enhanced flavor characteristics, particularly sweetness.

In some fruits such as tomato, grape and strawberry, cwINVs are implicated in Suc metabolism at least in the later stages of fruit development49–52. However, in this study, transcript abundance of cwINVs was undetectable from the transcriptome analyses38, suggesting that Suc breakdown to Glc and Fru in the apoplastic space is limited. These results imply that imported Suc is further metabolized or stored, upon entry into the cell. Among the cytosolic Suc catabolism enzymes, transcripts coding for SuSy and nINV were detected in blueberry, with higher transcript abundance of SuSy2 in comparison to nINV. However, the general transcript abundance of SuSy2 in ripe fruit was 5-fold lower than that of vINV. Hence, these results suggest that although active Suc catabolism occurs in the cytosol via SuSy, potentially greater catabolism, conversion into the constituent monosaccharides, and accumulation of the hexose sugars occur within the vacuole during blueberry fruit ripening (Fig. 7A). These results are supported by a previous study in southern highbush blueberry, where acid invertase protein abundance was found to be high during fruit ripening, although no discrimination was made between cwINV and vINV activities in that study53. High vINV expression has previously been noted to be important for maintaining cellular hexose concentration50. Further, greater Suc catabolism and higher hexose pool concentrations in sink tissues can help maintain or even increase the concentration gradient that allows for enhanced C import from source to sink tissues49,54. Positive associations between acid invertase activity and sugar content have been noted in muscadine grape and strawberry during ripening55,56. Results from this study suggest that compartmentalization of Glc and Fru in the vacuole may therefore allow for sustained Suc import throughout blueberry fruit ripening. Continued C import into the fruit, and accumulation of Suc and hexoses in sink cells is also accompanied by increased water transport into these cells, subsequently leading to an increase in fruit size and weight57. Consistently, such an increase in fruit size was noted in this study, especially between the S7 and S8 stages of ripening.

Figure 7.

Sugar (A), organic acid (B), and anthocyanin (C) metabolism pathways during fruit development and ripening in blueberry. Transcript abundance of genes during mid (S4/S5) and late fruit development (S7/S8) are presented in relation to the associated biochemical pathways. Red and green arrows indicate increased and decreased transcript abundance based on the transcriptome data38 between the mid and late fruit developmental stages, respectively. Asterisk next to the enzyme indicates validation of expression using quantitative RT-PCR analyses as depicted in Fig. 6. Solid black arrows indicate no change in the transcript abundance based on the transcriptome data of the enzyme between mid and late fruit developmental stages. Dotted blue arrows indicate steps where the corresponding transcript abundance was not identified in the transcriptome analyses. Dotted black arrows crossing organelle boundary indicate transport of the solute across compartments. A break in the arrows indicates a multi-step pathway.

Another route for Suc accumulation in sink cells is its re-synthesis from UDP-glucose and fructose-6-phosphate by sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) and sucrose phosphate phosphatase (SPP), a process referred to as the Suc-Suc cycle, as the above substrates are in-turn derived from Suc catabolism2. In the current study, transcript abundance of the two genes coding for these enzymes displayed an increasing trend during ripening (Figs. 5 and 7A). Further, additional SPS genes displayed high transcript abundance (TPM values) and increased during ripening by around 1.9-fold (Table S7). Consistently, increasing abundance of these enzymes was noted during ripening in southern highbush blueberry53. Hence, these data suggest that the Suc-Suc cycle partly contributes to Suc accumulation during ripening in blueberry, similar to that in fruits such as tomato, apple and grape11,50,58,59.

Another fate of the Suc imported into or synthesized within fruit during early stages of development is the synthesis of starch, which serves as a temporary C storage form17. In climacteric fruits such as tomato, starch concentration is highest in immature fruit (around 25 mg·g−1 FW), and declines at later stages17,47. These transient increases in starch reserves in early and mid-developmental stages likely contribute to the abundance of total soluble sugars in tomato during ripening60,61. In non-climacteric fruits, starch accumulation was high during immature fruit development: up to 7 mg·g−1 FW in strawberry, and around 0.507 mg·g−1 FW in grape at 14 days after anthesis (DAA); after which it declined during fruit maturation23,24,26. In these fruits, the contribution of starch to the final sugar amounts was negligible23,24. A comparison of eight fruit species differing in ripening behavior, indicated that climacteric fruits could be distinguished from non-climacteric fruits by their relatively higher net starch accumulation rates before the onset of ripening25. Further, degradation of starch and certain cell wall polymers has been associated with the ripening initiation of climacteric fruits19,25. In the current study, fruit starch concentrations were measured only during mid-development to ripening and were very low from the S4 to S8 stages (0.028–0.038 mg·g−1 FW). These results suggest that in blueberry, similar to that in non-climacteric fruits, starch reserves do not account for the dramatic increases in Suc and hexose sugar concentrations during ripening.

Comparison of metabolite profiles between climacteric and non-climacteric fruit did not indicate distinct shifts of intermediates related to glycolysis and the TCA cycle, suggesting a common regulatory mechanism across these two types of fruit ripening patterns20,62. In tomato, some studies suggest an increase in glycolysis-related enzyme activities to produce ATP and to support climacteric respiration63–65, while others suggest a decrease in glycolysis-related enzymes based on decrease in protein abundance during fruit maturation66,67. Similarly, in grape, despite the lack of a respiratory climacteric, dramatic changes in glycolytic intermediates were noted, with some studies suggesting a decrease in glycolytic intermediates20,68,69; while others indicating an increase70. In the current study, the majority of transcripts related to glycolysis such as FRUCTOKINASE (FK) and PFK increased during fruit ripening and were highly correlated with sugar concentration (present within the dark turquoise module). Consistently, in southern highbush blueberry, protein abundance of HK and PFK was upregulated during ripening53. These results indicate higher glycolytic activity during blueberry fruit ripening.

The primary organic acids, malate and citrate accumulate in rabbiteye blueberry fruit. However, malate is more abundant than citrate especially during mid-development and ripening initiation stages (S4-S7). Interestingly, in southern highbush blueberry cultivars, accumulation of citrate was greater in comparison to that of malate in green (S5), pink (S7), and ripe (S8) fruit, suggesting species specific variation in acid accumulation in blueberry53,71. During early fruit development, particularly during the cell expansion phase, accumulation of organic acids such as malate and citrate may contribute osmotically to facilitate turgor driven growth72. Malate can be synthesized from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), a glycolytic intermediate (Fig. 7B). PEP is first converted to oxaloacetate (OAA) by PEPC, which is an irreversible conversion, and to malate by cytosolic MDH, a reversible conversion. In grape and tomato, transcript abundance of PEPC and PEPC activity are high during early stages of fruit development suggesting conversion of OAA to malate72,73. In the current study, higher transcript abundance of several PEPC transcripts was noted at S5 and S6 stages and that of MDH, at all stages during ripening (Table S8). Based on increase in malate content until S7 stage in blueberry fruit, it is very likely that malate synthesis from PEP occurs during this period in blueberry fruit. It may be tempting to speculate that the subsequent decrease in malate concentration and amount between the S7 and S8 stages supports the respiratory climacteric in blueberry. A similar decrease in malate concentration was observed in grape and tomato15,20. Although malate has been suggested to serve as a substrate for respiration, alteration of malate levels through transgenic approaches resulted in relatively minor changes in respiration suggesting compensatory mechanisms that restore fruit metabolic status74. Further in grape, malate was a substrate for respiration during ripening initiation but not during the remainder of the ripening period, suggesting a relatively small contribution to ripening75. Similarly, stored malate was not dissimilated during ripening suggesting its insignificant contribution to fruit metabolism in peach76. Considering the high rate of respiratory CO2 release during ripening initiation in blueberry in this study and Wang, et al.31, the decrease in malate concentration and amount noted specifically at later stages of ripening suggest that it may not serve as the major direct substrate for respiration.

As mentioned previously, our data indicate that during ripening initiation the conversion from PEP to OAA and malate seems plausible due to expression of PEPC and increase in malate content (Fig. 7B). However, during ripening progression, high transcript abundance of PEPCK (> 1,000 TPM) and its association with the dark turquoise model (negatively correlated with malate) indicate that malate is used as a substrate to first generate OAA using MDH and then PEP by PEPCK77. A similar pattern of malate synthesis and degradation via MDH during the pre-véraison and post-véraison stages is noted in grapes73,78. This pathway can potentially allow for the use of PEP for gluconeogenesis, amino-acid biosynthesis and anthocyanin biosynthesis. The transcript abundance of other gluconeogenesis enzymes, PYRUVATE CARBOXYLASE (converts Pyruvate to OAA) and FRUCTOSE-1,6-BISPHOSPHATASE (Fru 1,6-bisphosphate to Fru-6-PO4) were low (TPM < 30), suggesting that similar to peach and grape, although gluconeogenesis is likely occurring in rabbiteye blueberry, it may have only a minor contribution to PEP consumption76,79. Alternatively, PEP serves as one of the substrates for quinate and shikimate biosynthesis. The shikimate pathway leads to the formation of aromatic amino acids that subsequently aid in the synthesis of anthocyanins and secondary metabolites. This potential conversion is supported by the increase in transcript abundance of DHQD/SDH, a gene coding for a bi-functional enzyme involved in the synthesis of shikimate from 3-dehydroquinate, an intermediate derived either from PEP (and erythrose-4-phosphate), or as a product of quinate catabolism (Fig. 7C). Further, the concentration of quinate decreased continuously during ripening including between the S7 to S8 stages, although the amount per fruit decreased only in ‘Powderblue’. The decrease in quinate concentration was mirrored by an increase in shikimate concentration (and amount), continuously during ripening in both cultivars.

We identified 15 different anthocyanins in ripe fruit. Among them, mal-3-gal concentration was greater in both ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’, similar to that reported in a previous study using these two cultivars80. Anthocyanin accumulation began with the onset of ripening (S6 stage) and reached peak values at the ripe (S8 stage) fruit. The coordinated increase in concentration of all anthocyanins in ripe fruit was associated with increase in transcript abundance of multiple anthocyanin biosynthesis genes during ripening (Fig. 7C). Similar to our results reported here, increase in transcript abundance of PAL, CHS, F3’H, FLS, CHS, UFGT, and ANS during bilberry and northern highbush blueberry fruit ripening was in fact associated with an increase in anthocyanin accumulation81,82. Together, these data indicate that PEP and quinate are likely targeted for shikimate synthesis to support anthocyanin accumulation during the later stages of ripening.

Conclusion

Glucose, Fru, and Suc are the major accumulated sugars during blueberry fruit ripening. Continued increase in these sugars during ripening indicates a need for sustained C import into fruit from source tissues throughout later stages of fruit development, including during ripening progression. Sucrose catabolism is active in the cytosol, but may be greater in the vacuole via vINV, leading to Glc and Fru accumulation. Starch accumulation from mid-development to ripening is not significant in blueberry fruit and is therefore not a major contributor to accumulation of sugars during ripening, further emphasizing the need for sustained C import. This is consistent with patterns in non-climacteric fruits and underscores the atypical climacteric ripening behavior noted in blueberry31. While the decrease in malate concentration observed in this study during fruit ripening may support the TCA cycle, it also supports the enhancement of anthocyanin biosynthesis, via synthesis of PEP along a pathway mediated by PEPCK. Overall, this study provides deeper insights into metabolic transitions during development and ripening of blueberry fruit.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1. Figure S1. Scree plot displaying the percentage of variability explained by each dimension in principal component analysis.

Supplementary Material 2. Figure S2. Amount per unit fruit weight of Sucrose (A), Glucose (B), Fructose (C), Starch (D), Malate (E), Citrate (F), Quinate (G), and Shikimate (H) during S4 to S8 developmental stages in two cultivars, Premier (dashed line with triangle) and Powderblue (solid line with circle). Values are mean ± S.E. (n=4). Different letters above symbols indicate significant differences across fruit development stages within a given cultivar according to Fisher's LSD (α=0.05).

Supplementary Material 3. Figure S3. Concentration of starch determined at various time points during the day. S4 stage (A), S5 stage (B), S6 stage (C) are fruit development stages, and leaf (D) in two cultivars, Premier (dashed line with triangle) and Powderblue (solid line with circle). Values are mean ± S.E. (n=4). Different letters above symbols indicate significant differences across fruit development stages within a given cultivar according to Fisher's LSD (α=0.05).

Supplementary Material 4. Figure S4. Concentration of Myo-inositol (A), Xylose (B), Sorbitol (C), Maltose (D), Succinate (E), Glycerate (F), Fumarate (G), Glutamate (H), Aspartate (I), Serine (J), Alanine (K), and Threonine (L) during various stages of fruit development in ‘Premier’ (dashed line with triangle) and ‘Powderblue’ (solid line with circle) blueberry. Values are displayed as mean ± S.E. (n = 4). Different letters above symbols indicate significant differences across fruit development stages within a given cultivar according to Fisher's LSD (α=0.05).

Supplementary Material 5. Figure S5. The number of genes present in each of the nine modules determined by weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA).

Supplementary Material 6. Tables S1 to S9: Table S1. Retention time, and mass spectral data of specific anthocyanins from ‘Premier’ and ‘Powderblue’. Table S2. Genes and primer sequences for qRT-PCR analysis. Table S3: Correlation analysis of metabolites during fruit development and ripening in 'Premier' and 'Powderblue' blueberry. Table S4. Differentially expressed genes in the dark turquoise module of WGCNA, with gene significance and p-value in relation to specific metabolites. Table S5. Biological process component of Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the dark turquoise module from WGCNA. Table S6. Heat map showing average value of transcript abundance (TPM) of starch metabolism-related genes from the 'Powderblue' blueberry fruit ripening transcriptome. Table S7. Heat map showing average value of transcript abundance (TPM) of sugar metabolism-related genes from the 'Powderblue' fruit ripening transcriptome. Table S8. Heat map showing average value of transcript abundance (TPM) of organic metabolism related genes from the 'Powderblue' blueberry fruit ripening transcriptome. Table S9. Heat map showing average value of transcript abundance (TPM) of anthocyanin metabolism-related genes from the 'Powderblue' blueberry fruit ripening transcriptome.(XLSX 387 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank John Doyle for helping with sample collection and the Department of Horticulture, University of Georgia for supporting TPA with a graduate research assistantship.

Author contributions

Author contributions: TPA and SUN conceived the study. TPA and SUN designed the experiment. TPA collected data and processed samples. TPA, SUN and AM analyzed and interpreted the data. TPA, AM, and SUN wrote and reviewed the manuscript. All authors wrote and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This publication was partly supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Agricultural Marketing Service through grant AM180100XXXXG014. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the USDA.

Data availability

All data presented in this study are provided as main figures, tables and supplementary materials.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Birkhold, K. T., Koch, K. E. & Darnell, R. L. Carbon and nitrogen economy of developing rabbiteye blueberry fruit. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 117, 139–145 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein, O. & Granot, D. An overview of sucrose synthases in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 435701 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemoine, R. et al. Source-to-sink transport of sugar and regulation by environmental factors. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 272 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaki, S. Metabolism and accumulation of sugars translocated to fruit and their regulation. J. Japanese Soc. Hortic. Sci. 79, 1–15 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bieleski, R. Accumulation and translocation of sorbitol in apple phloem. Australian J. Biol. Sci. 22, 611–620 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paniagua, C., Sinanaj, B. & Benitez-Alfonso, Y. Plasmodesmata and their role in the regulation of phloem unloading during fruit development. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 64, 102145 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun, D. M., Wang, L. & Ruan, Y. L. Understanding and manipulating sucrose phloem loading, unloading, metabolism, and signalling to enhance crop yield and food security. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 1713–1735 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du, M., Zhu, Y., Nan, H., Zhou, Y. & Pan, X. Regulation of sugar metabolism in fruits. Sci. Hort. 326, 112712 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fridman, E., Carrari, F., Liu, Y. S., Fernie, A. R. & Zamir, D. Zooming in on a quantitative trait for tomato yield using interspecific introgressions. Science. 305, 1786–1789 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch, K. Sucrose metabolism: regulatory mechanisms and pivotal roles in sugar sensing and plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 7, 235–246 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li, M., Feng, F. & Cheng, L. Expression patterns of genes involved in sugar metabolism and accumulation during apple fruit development. PloS ONE. 7, e33055 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, S., Chen, K. & Grierson, D. Molecular and hormonal mechanisms regulating fleshy fruit ripening. Cells. 10, 1136 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batista-Silva, W. et al. Modifications in organic acid profiles during fruit development and ripening: correlation or causation? Front. Plant Sci. 9, 416868 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verbančič, J., Lunn, J. E., Stitt, M. & Persson, S. Carbon supply and the regulation of cell wall synthesis. Mol. Plant. 11, 75–94 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrari, F. & Fernie, A. R. Metabolic regulation underlying tomato fruit development. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 1883–1897 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colombié, S. et al. Modelling central metabolic fluxes by constraint-based optimization reveals metabolic reprogramming of developing Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) fruit. Plant J. 81, 24–39 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaffer, A. A. & Petreikov, M. Sucrose-to-starch metabolism in tomato fruit undergoing transient starch accumulation. Plant Physiol. 113, 739–746 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beauvoit, B. et al. Putting primary metabolism into perspective to obtain better fruits. Ann. Botany. 122, 1–21 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colombié, S. et al. Respiration climacteric in tomato fruits elucidated by constraint-based modelling. New Phytol. 213, 1726–1739 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai, Z. W. et al. Metabolic profiling reveals coordinated switches in primary carbohydrate metabolism in grape berry (Vitis vinifera L.), a non-climacteric fleshy fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1345–1355 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gómez-Romero, M., Segura-Carretero, A. & Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Metabolite profiling and quantification of phenolic compounds in methanol extracts of tomato fruit. Phytochemistry. 71, 1848–1864 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lombardo, V. A. et al. Metabolic profiling during peach fruit development and ripening reveals the metabolic networks that underpin each developmental stage. Plant Physiol. 157, 1696–1710 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Souleyre, E. J. et al. Starch metabolism in developing strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) fruits. Physiol. Plant. 121, 369–376 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu, X. et al. Enzyme activities and gene expression of starch metabolism provide insights into grape berry development. Hortic. Res.4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Roch, L. et al. Biomass composition explains fruit relative growth rate and discriminates climacteric from non-climacteric species. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 5823–5836 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moing, A. et al. Biochemical changes during fruit development of four strawberry cultivars. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 126, 394–403 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oms-Oliu, G. et al. Metabolic characterization of tomato fruit during preharvest development, ripening, and postharvest shelf-life. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 62, 7–16 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paul, V., Pandey, R. & Srivastava, G. C. The fading distinctions between classical patterns of ripening in climacteric and non-climacteric fruit and the ubiquity of ethylene—An overview. J. Food Sci. Technol. 49, 1–21 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuentes, L., Figueroa, C. R. & Valdenegro, M. Recent advances in hormonal regulation and cross-talk during non-climacteric fruit development and ripening. Horticulturae. 5, 45 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seymour, G. B., Østergaard, L., Chapman, N. H., Knapp, S. & Martin, C. Fruit development and ripening. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 219–241 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, Y. W. et al. Atypical climacteric and functional ethylene metabolism and signaling during fruit ripening in blueberry (Vaccinium Sp). Front. Plant Sci. 13, 932642 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zifkin, M. et al. Gene expression and metabolite profiling of developing highbush blueberry fruit indicates transcriptional regulation of flavonoid metabolism and activation of abscisic acid metabolism. Plant Physiol. 158, 200–224 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beshir, W. F. et al. Dynamic labeling reveals temporal changes in carbon re-allocation within the central metabolism of developing apple fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1785 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith, A. M. & Zeeman, S. C. Quantification of starch in plant tissues. Nat. Protoc. 1, 1342–1345 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Downey, M. O. & Rochfort, S. Simultaneous separation by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectral identification of anthocyanins and flavonols in Shiraz grape skin. J. Chromatogr. A. 1201, 43–47 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prior, R. L., Lazarus, S. A., Cao, G., Muccitelli, H. & Hammerstone, J. F. Identification of procyanidins and anthocyanins in blueberries and cranberries (Vaccinium spp.) using high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 1270–1276 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu, X. & Prior, R. L. Systematic identification and characterization of anthocyanins by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS in common foods in the United States: fruits and berries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 2589–2599 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, Y. W. & Nambeesan, S. U. Ethylene promotes fruit ripening initiation by downregulating photosynthesis, enhancing abscisic acid and suppressing jasmonic acid in blueberry (Vaccinium ashei). BMC Plant Biol. 24, 418 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 9, 1–13 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian, T. et al. agriGO v2. 0: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community, 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W122–W129 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vashisth, T., Johnson, L. K. & Malladi, A. An efficient RNA isolation procedure and identification of reference genes for normalization of gene expression in blueberry. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 2167–2176 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, Y. W. & Nambeesan, S. U. Full-length fruit transcriptomes of southern highbush (Vaccinium sp.) and rabbiteye (V. Virgatum Ait.) Blueberry. BMC Genom. 23, 733 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruijter, J. et al. Amplification efficiency: linking baseline and bias in the analysis of quantitative PCR data. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, e45–e45 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rieu, I. & Powers, S. J. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR: design, calculations, and statistics. Plant. Cell. 21, 1031–1033 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Birkhold, K. T. & Darnell, R. L. Contribution of carbon and nitrogen reserves to vegetative and reproductive growth of rabbiteye blueberry. HortScience. 26, 682G-682 (1991).

- 46.Brookfield, P., Murphy, P., Harker, R. & MacRae, E. Starch degradation and starch pattern indices; interpretation and relationship to maturity. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 11, 23–30 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luengwilai, K. & Beckles, D. M. Starch granules in tomato fruit show a complex pattern of degradation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 8480–8487 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tijero, V., Girardi, F. & Botton, A. Fruit development and primary metabolism in apple. Agronomy. 11, 1160 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawaguchi, K. et al. Functional disruption of cell wall invertase inhibitor by genome editing increases sugar content of tomato fruit without decrease fruit weight. Sci. Rep. 11, 21534 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen-Quoc, B. & Foyer, C. H. A role for ‘futile cycles’ involving invertase and sucrose synthase in sucrose metabolism of tomato fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 881–889 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, X. Y. et al. A shift of phloem unloading from symplasmic to apoplasmic pathway is involved in developmental onset of ripening in grape berry. Plant Physiol. 142, 220–232 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan, H. Z. et al. Genome-wide analysis of the invertase genes in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). J. Integr. Agric. 20, 2652–2665 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li, X., Li, C., Sun, J. & Jackson, A. Dynamic changes of enzymes involved in sugar and organic acid level modification during blueberry fruit maturation. Food Chem. 309, 125617 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruan, Y. L. Sucrose metabolism: gateway to diverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 33–67 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kambiranda, D., Vasanthaiah, H. & Basha, S. M. Relationship between acid invertase activity and sugar content in grape species. J. Food Biochem. 35, 1646–1652 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Topcu, H. et al. Sugar, invertase enzyme activities and invertase gene expression in different developmental stages of strawberry fruits. Plants. 11, 509 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen, J. et al. Fruit water content as an indication of sugar metabolism improves simulation of carbohydrate accumulation in tomato fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 5010–5026 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grimplet, J. et al. Tissue-specific mRNA expression profiling in grape berry tissues. BMC Genom. 8, 1–23 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jing, S. & Malladi, A. Higher growth of the apple (Malus× Domestica Borkh.) fruit cortex is supported by resource intensive metabolism during early development. BMC Plant Biol. 20, 1–19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]