Abstract

Background:

Childhood maltreatment has great impact on physical and mental health. This study was designed to investigate the relationship between childhood maltreatment experience, social support, Anxiety and Depression, and traumatic stress symptoms in adults.

Methods:

There were 113 subjects aged 20-35 recruited. They filled out self-reported questionnaires, including the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form (CTQ-SF), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ), Chinese version of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), and Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), to measure symptom severity regarding childhood maltreatment, Anxiety and Depression, post-traumatic stress/complex post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSD/CPTSD), and social support. The symptom severity was compared between maltreatment and non-maltreatment groups. Regression and mediator analyzes were done to investigate the relationship between maltreatment experience, mental impact severity, and the role of social support.

Results:

There were 74.3% of participants who had been maltreated as children. Those who experienced maltreatment had more PTSD/CPTSD symptom severity than those who did not. Family support, but not friend support, mediated the relationship between maltreatment and PTSD/CPTSD symptom severity.

Conclusion:

Childhood maltreatment was associated with Anxiety and Depression and CPTSD symptom severity in young adults. Future prospective studies are warranted to investigate the role of family support in preventing consequences after maltreatment.

Main Points

Childhood maltreatment was associated with Anxiety and Depression and stress symptoms in adults.

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire was useful as a self-report measurement of the severity of maltreatment.

Family support mediated the relationship between maltreatment and complex PTSD symptoms.

Introduction

Childhood maltreatment is a social and public health problem that may lead to child mortality. It has a great impacts on mental health, substance/alcohol use, criminal behaviors, and physical problems such as obesity or metabolic syndromes when children grow into adulthood.1 Though child welfare has been addressed for decades, children are still exposed to maltreatment. The proportion of maltreatment among children in Asia has been investigated.2 There were 88.6% of primary school students in Taiwan who had been maltreated, 22.9% had been physically abused, 43.6% had been emotionally abused, 9.6% had been sexually abused, 69.3% had been emotionally neglected, and 66.4% had been physically neglected.3 It had been reported that 64.7% of college students in China had been mistreated. Among them, 17.4% were physically abused, 36.7% emotionally abused, 15.7% sexually abused, 54.9% physically neglected, and 60% emotional neglect.4 In Western countries, 62.2% of the people in Australia,5 33% in the UK6 and 43.7% in Sweden7 had been exposed to maltreatment.

People who have experienced maltreatment are likely to develop physical and mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, and psychotic symptoms.8 The treatment response for patients with mental disorders comorbid with maltreatment is usually poorer than for those who without.8 They have more suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, or self-injury behavior.9-11 Most survivors are exposed to more than a single type of maltreatment. For example, sexual abuse is often accompanied by physical abuse. Any type of trauma may be combined with the occurrence of psychological abuse or emotional abuse.12 The more exposure to multiple or high-intensity traumatic experiences in childhood, the higher the risk of developing psychiatric disorders in adulthood, such as severe post-traumatic stress symptoms, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and alcohol/drug addiction.13 In addition, exposure to prolonged maltreatment has a great impacts on the integrity of self-concept, emotional regulation, and interpersonal relationships, leading to complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). It would therefore complicate the treatment course.14-17

The level of support from family or peers is associated with the development of mental or physical symptoms among people experienced maltreatment.18 On the other hand, children exposed to prolonged and repeated maltreatment could have poorer emotion regulation as immature coping strategies, such as avoidance, dissociation, irritability, or self-criticism. It has even affected the individual’s social function.19 In addition, maltreatment could lead to low self-esteem and insecure attachment, which turned into lower perceived social support, increased interpersonal distress, and adaptive difficulty.20 These may in turn weaken the protective factors, thereby putting the victims at increased risk of depression, anxiety, or stress disorders.21-24 Peers could provide support by delivering enough information and letting victims know where to get resources such as to file a complaint or take legal action that could provide important assistance to such people.25 The peer support groups for those who have suffered the same experience can share how to get out of negative influences. The sense of intimacy among family members is a protective factor that can gradually build confidence in victims who have been maltreated and gradually restore their feelings of safety.26 The attachment with caregivers is essential for the development of children’s ability for resilience.20,27

The result of previous studies on childhood maltreatment might be limited by the fact that parents are often unwilling to disclose the maltreatment experience of their children. Children in Asia were found to be more suppressed and tend to hide such experiences and are unwilling to disclose them to people outside the family. Besides, maltreatment is a series of events. It is very likely that people who had been exposed to such experiences became accustomed to it and did not take it seriously. Therefore, it is hard to have reliable information if the studies were conducted on children or the parents of children who have encountered maltreatment.28 In addition, there was possible bias from clinical case studies to explore the impact of maltreatment for patients, diagnosed depression, anxiety, and/or PTSD since those subjects might be influenced by the disease symptoms once they become chronic and have distorted cognition or amplifying past traumatic experiences.29 This present study used a younger adult group and might have a less recalling bias since the time period from these childhood experiences is not long.30 They were in the early stages of adapting to society and facing many stresses. This study may help to understand the psychological reactions that occur under stress.31 Different from studies of clinical cases, this study conducted in the non-clinical population was more likely to provide important clues to social care and public health. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that adverse childhood treatment is a risk factor for mental symptoms in adulthood, and social support is a possible protective factor. Understanding it may be helpful to national public health policies.

Methods

Participants

Individuals aged from 20 to 35 in the community were invited to participate in this study. This study was conducted by convenience sampling. We used G power to calculate the sample size. The effect size was set as 0.2. The alpha value was 0.05 (power = 0.95). The sample size for 5 variables was 106. We announced the information regarding the criteria of recruitment and invited our team members to introduce their friends for participation in this study. The subjects filled out the online questionnaires after face-to-face explanation and informed consent. Almost 20% of them were college students, and 80% were within 10 years after graduation from school. There were no subjects recruited having clinical psychiatric disorders, or severe physical disorders. A total of 121 consent forms and 113 questionnaires were included for analysis. There were 6 subjects who did not finish the questionnaires. Two of the 121 subjects were considered screening failures since their questionnaires were invalid and excluded. There was a subject who had a history of depressive disorder, another one had a history of bipolar disorder. They both were not in the active phase and did not receive treatment. We included the individuals who could understand the process of study and comply to the requirement to fill out the questionnaires in the community. We did not exclude the subjects with a history of psychiatric disorder since their current condition to report their symptoms was not affected by it. The compensation for the participation in this study was 100 NTD (3.5 USD). The questionnaires were used to investigate the maltreatment experience during childhood, and their current anxiety, depression, traumatic symptoms, and social support from either friends or family. This study has been approved by Institute Research Board for ethical regulation.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the National Defense Medical Center, Tri-Service General Hospital Institutional Review Board (Approval Number: B202205006) on 26 Jan 2022. All included participants provided signed informed consent.

Questionnaires

There were 9 self-reported scales including Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form (CTQ-SF), International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ), and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Chinese version of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), and Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). All the above research questionnaires obtained the authorization and consent of the original author.

Measurements of Maltreatment

Short Form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF) has 28 items. It has 5 subscales including physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect.32 The internal consistency of the Chinese version, except for physical neglect (Cronbach alpha = 0.57), all other Cronbach alpha values were above 0.71. The test-retest reliability was r = 0.67-0.85.33

Measurements of CPTSD/PTSD Symptoms

The 11th revision of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) has introduced the diagnosis: complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). It includes the symptoms criteria for not only PTSD but also for disturbances in self-organization (DSO) which are characterized by affective dysregulation (e.g. heightened emotional reactivity, anger outbursts, feeling emotionally numb or dissociated), a negative self-concept (e.g. feeling diminished, defeated or worthless; pervasive feelings of shame, guilt), and enduring disturbances in relationships (e.g., feeling distant from others, having difficulty maintaining intimate relationships).34

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) has 18 items including PTSD and DSO dimensions. Each dimension consist of 3 subscales (PTSD: re-experience, avoidance, sense of current threat; DSO: emotional dysregulation, disturbance in self-esteem, difficulty in interpersonal relationships). It also includes the measurements of social, work, and life functions.34 The reliability and validity had been done for the Chinese version in Taiwan. The internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha values were above 0.90, and the test-retest reliability was 0.80-0.88.35 The test-retest reliability for ITQ showing correlation coefficients for CPTD total score = 0.88, PTSD subscale = 0.83, DSO subscale = 0.80 in our finding. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) is a 20-item, self-report, 5-point scale with each item corresponding to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria.36 The reliability and validity of the Chinese version had been done. The internal consistency of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95. The correlation analysis was carried out to compare with the questionnaire Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (r = 0.443; P = .001). The comparison of the mean score of PCL-5 between the clinical and control groups was analyzed by t-test (t = 3.087, P = .003) showing that there was a significant difference, indicating good reliability and validity.37

Measurements of Depression/Anxiety

Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI-II) is a self-reported scale with 4-point 21 items. It is used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms.38 The reliability and validity test of the Chinese version of this questionnaire showed internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94, the split-half reliability = 0.91. It has been compared with the Chinese Health Questionnaire (r = 0.69, P < .001). The cut-point score is mild 14-19, moderate 20-28, and severe 29-63.39 Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is a 21-item self-reported 4-point scale.40 The reliability and validity of the Chinese version was established. The internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95, the split-half reliability was 0.91, the Cohen’s kappa value was 1.0. It was consistent with the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (r = 0.72, P < .001), showing that this questionnaire has good reliability and validity.41

Measure of Possible Mediators: Family Support and Friend Support

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is a 12-item self-report scale with 3 dimensions including support from family, friends and significant others.42 The factor analysis of the Chinese version showed that the two-factor model had the greatest explanatory power and was divided into family and friend support. The scores of “Family support” and “Friend support” were calculated by the subscales of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). The internal consistency Cronbach alpha value was 0.89 (the Cronbach’s alpha value of family and friend support were 0.86 and 0.94, respectively).43

Statistics

We used IBM SPSS statistic 22, SPSS Amos 21and PROCESS 4.2 for analysis of the results. The descriptive statistics to understand the characteristics of the subjects, including gender, age, maltreatment experience, social support level, and the mean score of the severity of depression/anxiety, PTSD/CPTSD symptoms. We divided the recruited individuals into groups according to the scores of the CTQ scale. The subjects who met the cut-off point of maltreatment will be classified into the group of maltreatment, and the others will be the control group. We compared the difference in mean score of severity of symptoms between the two groups with Mann–Whitney U-test to see if the trauma group had more severe depression/anxiety or PTSD/CPTSD symptoms than the control group. As for the subjects who have maltreatment experience, we classified the subjects by the number of CTQ category experiences. Subjects were divided into more (≥ 3 subtypes), and fewer (2 or 1 subtypes), while those who had never experienced maltreatment were the control group. Kruskal–Wallis H-test was done to compare the mean score among the 3 groups to investigate whether experiencing more types of traumatic experiences would lead to more severe Anxiety and Depression or PTSD/CPTSD symptoms. Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn exam were performed for a post-hoc test if the variance is homogeneous. The collinearity was examined with statistics that eigenvalue and VIF showed no significant collinearity. The confidence intervals for B were also reported in both the main text and figures.

Results

A total of 113 people were included in this study, with a mean age of 26.4 (SD = 3.48), including 51 male and 62 female individuals. Eighty-five (74.3%) subjects reported that they had been exposed to maltreatment, among which emotional neglect was the most. A total of 64 (54.9%) subjects had been exposed to emotional neglect. Six (5.3%) of the subjects met the symptoms of CPTSD, 15 (13.3%) met the symptoms of PTSD, 43 (38.1%) met the symptoms of depression, and 26 (23%) met the symptoms of anxiety (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Data of the Subjects

| Variable | Mean (SD) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 51 (45.1) | |

| Female | 62 (54.9) | |

| Age | 26.40 (3.48) | |

| CTQ-total score | 39.62 (12.21) | 85 (74.3) |

| Physical abuse | 7.47 (3.48) | 34 (30.1) |

| Emotional abuse | 7.97 (3.42) | 37 (32.7) |

| Sexual abuse | 5.61 (1.74) | 24 (21.2) |

| Emotional neglect | 10.81 (4.60) | 62 (54.9) |

| Physical neglect | 7.76 (2.97) | 48 (42.5) |

| ITQ-total score | 11.71 (9.97) | 6 (5.3) |

| PTSD symptom | 5.62 (5.66) | 10 (8.8) |

| DSO symptom | 6.09 (5.28) | 14 (12.4) |

| PCL-5 | 12.51 (16.73) | 15 (13.3) |

| BDI | 10.88 (10.62) | 43 (38.1) |

| BAI | 7.61 (9.72) | 26 (23) |

| MSPSS | 65.71 (16.80) |

CTQ, childhood trauma questionnaire; ITQ, international trauma questionnaire; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; DSO, disturbance of self-organizations; PCL-5, PTSD checklist for DSM-5; BDI, Beck depression inventory; BAI, Beck anxiety inventory; MSPSS, multidimensional scale of perceived social support.

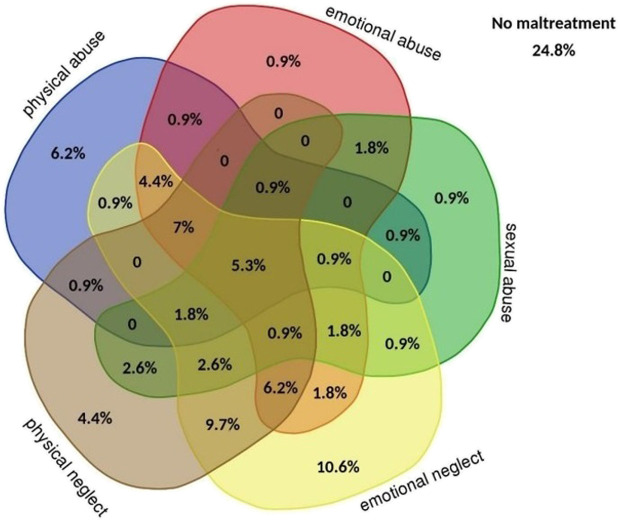

There were 26 (23%) subjects who had experienced one type of childhood trauma, 23 (20.4%) two types of traumatic experiences, 17 (15%) three types of traumatic experiences, 13 (11.5%) four types of traumatic experiences, and 6 (5.3%) five types of traumatic experience. There were 28 (24.8%) subjects who had never been exposed to maltreatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The proportion of different types of maltreatment. Maltreatment included emotional abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, and physical abuse by international trauma questionnaire classification.

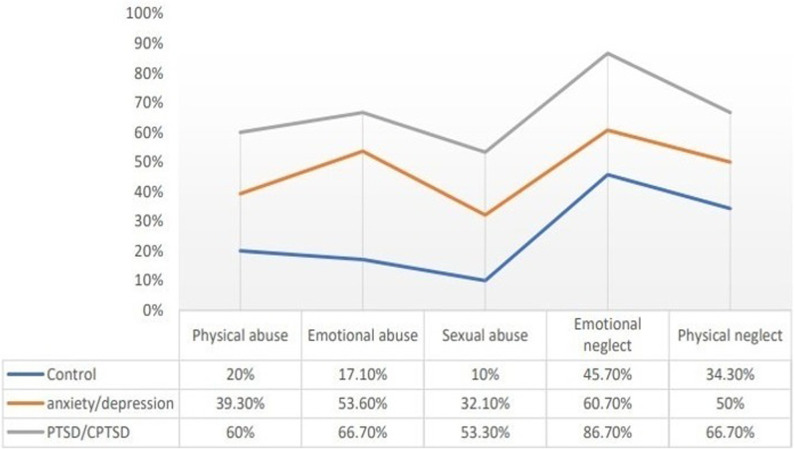

The proportion of exposure to different types of maltreatment among PTSD/CPTSD group was higher than depression/anxiety or control groups. There were 25 (89.3%) subjects of the depression/anxiety group who had been exposed to maltreatment, of which 53.6% had been exposed to emotional abuse, 60.7% emotional neglect, and 50% physical neglect. In the control group, 45 (65.2%) subjects were still exposed to maltreatment, of which emotional neglect is as high as 46.6% (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of proportion of maltreatment types between Anxiety and Depression, PTSD/CPTSD, and control groups. PTSD/CPTSD group contains those who met CPTSD or PTSD criteria and mood disorders (n = 16); Anxiety and Depression group contains those who met the criteria of mood disorders without reaching CPTSD or PTSD (n = 28); Control group contains those who did not met above criteria (n = 69).

The maltreated group had significantly more symptom severity scores than the control group in depression (P < .001), anxiety (P = .001), CPTSD (P < .001), and PTSD (P = .003) symptoms. The maltreated group had significantly lower scores than the non-maltreated group in perceived social support (P = .001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparing Groups Between Maltreatment and Non-maltreatment Groups with Mann-Whitney U test

| Mean (SD) |

Z |

P |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maltreated group (n = 85) | non-maltreated group (n = 28) | |||

| ITQ | 13.78 ± 10.08 | 5.43 ± 6.42 | 3.99 | < .001 |

| PCL-5 | 14.95 ± 17.89 | 5.11 ± 9.43 | 2.93 | .003 |

| BDI | 12.86 ± 11.20 | 4.86 ± 5.27 | 3.88 | < .001 |

| BAI | 9.31 ± 10.56 | 2.46 ± 3 | 3.32 | .001 |

| MSPSS | 62.92 ± 16.55 | 74.18 ± 14.82 | −3.63 | < .001 |

ITQ, international trauma questionnaire; PCL-5, PTSD checklist for DSM-5; BDI, Beck depression inventory; BAI, Beck anxiety inventory; MSPSS, multidimensional scale of perceived social support.

Those who were exposed to more maltreatment (≥ 3 types) had more impact on symptom severity score than those exposed to “few maltreatments (1 or 2 types)” and “control group (0 type).” The group that had more maltreatment had more severe CPTSD (H = 31.08, P < .001), PTSD (H = 21.56, P < .001), depression (H = 24.69, P < .001), and anxiety (H = 20.80, P < .001) symptoms score than both group with few maltreatments and the control group. However, the participants who had been exposed to maltreatment had worse social support score (H = 18.48, P < .001) than the control group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Compare Symptoms Severity Among Groups with Kruskal–Wallis Test

| Mean (SD) |

H |

P |

Post-hoc |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group (n = 28) | Few (1, 2) maltreatments (n = 49) | More (≥ 3) maltreatments (n = 36) | ||||

| ITQ | 5.43 ± 6.42 | 10.08 ± 9.22 | 18.81 ± 9.08 | 31.08 | < .001 | 2 > 1 = 0 |

| PCL-5 | 5.11 ± 9.43 | 10.88 ± 17.61 | 20.5 ± 16.98 | 21.56 | < .001 < .001 < .001 |

2 > 1 = 0 |

| BDI | 4.86 ± 5.27 | 10.27 ± 11.18 | 16.39 ± 10.36 | 24.69 | 2 > 1 = 0 | |

| BAI | 2.46 ± 3 | 7.06 ± 10.72 | 12.36 ± 9.66 | 20.80 | 2 > 1 = 0 | |

| MSPSS | 74.18 ± 14.82 | 66.33 ± 16.32 | 58.28 ± 15.93 | 18.48 | < .001 | 2 = 1 < 0 |

Control group = 0; Group of few maltreatment = 1; Group of more maltreatment = 2

ITQ, international trauma questionnaire; PCL-5, PTSD checklist for DSM-5; BDI, Beck depression inventory; BAI, Beck anxiety inventory; MSPSS, multidimensional scale of perceived social support.

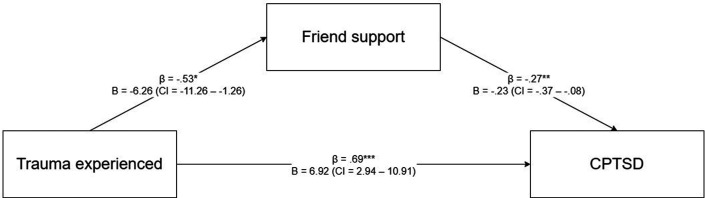

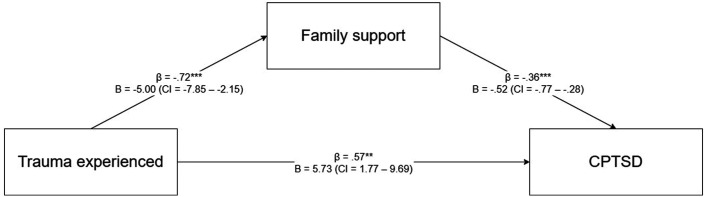

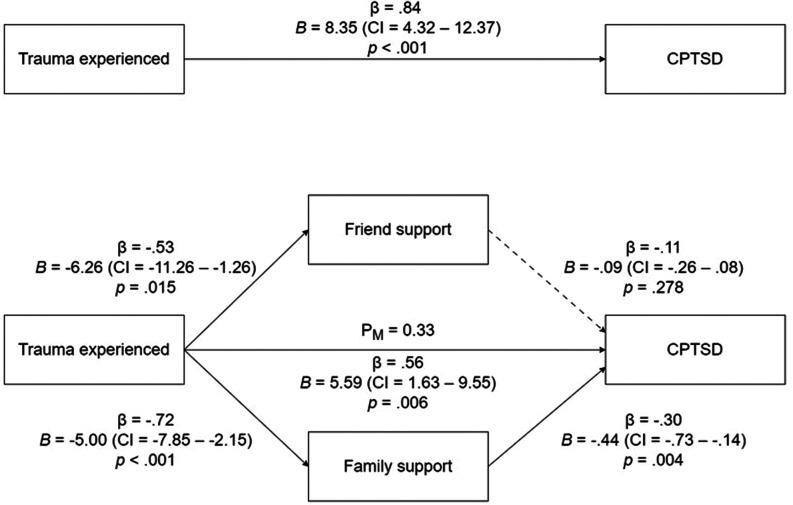

We used regression analysis to test the relationship between variables, and there was a partial mediating effect between maltreatment experience and peer support and family supportand CPTSD symptoms (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 2).

Supplementary Table 1.

The Regression Analysis to Test the Relationship Between Variables

| Independence variable | Dependence variable | B | CI | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTQ | ITQ | 8.35 | 4.32 – 12.38 | .36*** |

| Friend support | -6.26 | -11.26 – -1.26 | -.23* | |

| Family support | -5.00 | -7.85 – -2.15 | -.31** | |

| Friend support | ITQ | -.29 | -.44 – -.14 | -.34*** |

| Family support | -.64 | -.88 – -.39 | -.44*** |

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; ITQ, International Trauma Questionnaire. The score of “Family support” and “Friend support” were calculated by the subscales of MSPSS.

Supplementary Figure 1.

The partial mediating effect of friend support between maltreatment and CPTSD symptoms.

Supplementary Figure 2.

The partial mediating effect of family support between maltreatment and CPTSD symptoms. **p < .01, ***p < .001. CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; ITQ, International Trauma Questionnaire. The score of “Family support” and “Friend support” were calculated by the subscales of MSPSS.

This study used support from friends and family as mediating variables. Having experienced maltreatment may directly affect CPTSD symptoms (β = 0.84, B = 8.35 (CI = 4.32 -12.37), P < .001), and maltreatment experience can significantly predict friend support (β = −0.53, B = −6.26 (CI = −11.26 − −1.26), P = .015) and family support (β = −0.72, B = −5 (CI = −7.85 − −2.15), P < .001). Family support (β = −0.30, B = −0.44 (CI = −0.73 − −0.14), P = .004) also significantly affected CPTSD symptoms. Experiencing maltreatment had an impact on CPTSD symptoms. There was a significant indirect prediction effect (β = 0.56, B = 5.59 (CI = 1.63 − 9.55), P = .006). However, in this model, support from friends did not have a significant mediation effect on CPTSD (β = −0.11, B = −0.09 (CI = −O.26 − 0.08), P = .278) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The mediating effect of two dimensions of social support in the relationship between maltreatment and CPTSD systems. Maltreatment was categorical variable, having trauma experienced was coded as 1 and another as 0. CPTSD, complex posttraumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

In line with previous studies, our results indicated that childhood maltreatment was associated with PTSD/CPTSD symptom severity in adults. Support from peers and family was proposed to play roles as mediators in this relationship. Compared with other countries, the prevalence of childhood maltreatment in Taiwan was higher than in Western countries.5-7 Previous studies showed parenting styles in Eastern cultures often implemented as corporal punishment which was considered a usual experience. Previous studies indicated that social economy, social welfare policy, and domestic socioeconomic status could affect the incidence of child abuse. The rate of domestic violence in countries with lower economic levels or uneven distribution of resources was higher than in other countries. Meanwhile, mistreated children were less willing to seek help if the social assistance was less easy to apply. Above all, there’s a higher prevalence rate of children exposed to abuse or neglect in families with lower socioeconomic status or poor domestic ability.44 Therefore, improving the social support system and helping at-risk families timely would be the primary tasks for preventing childhood maltreatment.

In addition, chronic maltreatment might lead to impaired mentalization of survivors, making them difficult to understand or identify their own emotions. It often makes them prone to feeling emotionally numb to things and even developing dissociative responses to escape stressful events. It would also make such survivors less tolerant on frustration, and more likely to have negative emotional reactions when they encounter stress.45 Meanwhile, such emotional dysregulation makes it difficult for survivors to develop effective interpersonal strategies.46 Therefore, we speculated that they would feel uneasy and distrustful of others, making it difficult to establish or maintain a relationship, which weakens the survivors’ possible social support. Previous studies have also shown that maltreatment experiences have a great impact on brain development.47 Children who grew up in abused environments might have impact on the development of language and emotion-related brain areas, resulting in survivors being sensitive to the emotion recognition of anger, difficulty recognizing emotional expression from others, and difficulty expressing other emotions besides anger.48

Our results found that adults with childhood maltreatment experience are more likely to have traumatic stress symptoms. As we explored childhood experiences of maltreatment, we learned that these effects persisted into adulthood while we were using the ITQ questionnaire to investigate symptoms of complex post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. This group of people might suffer from problems with self-concept, problems in getting along with others, and emotional instability, and these traits happen to cause functional impairment in life adaptation.

The patients with PTSD symptoms characterized by dissociation, being intruded, or symptoms of avoidance and numbness are easy to be recognized by outsiders. However, patients with CPTSD might have symptoms of disturbances in self-organization (DSO) which may be easily ignored. In addition, the trauma of traditional PTSD is a major and significant life-critical event, which is different from the childhood experience of maltreatment. Therefore, the experience of maltreatment may easily go unnoticed and has not been dealt with appropriately. This study used CTQ to investigate the severity of childhood maltreatment and used a cut point to divide subjects into 0 and 1 since previous studies had found that almost all of them are repeatedly victimized and may suffer multiple maltreatment experiences. In addition to the overlap of types, they may also be repeatedly abused in time series. Therefore, it is hard for them to report the types or timeframe of such a chronic experience. Besides, the severity of the victimization and stress symptoms depends on the subjective feelings of the subjects. Those above might explain using CTQ as severity of maltreatment and CPTSD as outcome measurement in this study.

Our mediator analysis found that family support can slow down such symptoms, but peer support cannot have such protective effect. Previous studies confirmed that well social support can reduce the impairments caused by maltreatment.18,49 Social support may be related to many factors, such as a sense of identity, a sense of belonging, and a sense of efficacy which are all related.50The self-efficacy can mediate the relationship between social support and PTSD symptoms.51 The support that can be provided by the family environment or well parenting attitude. It includes having a secure attachment relationship and developing a low sensitivity to rejection in a good family environment, which can bring about protective effects.52 In addition to environmental factors, subjective cognitive status is also relevant. For example, it has been reported that the perceived status of social support will also affect whether it evolves into a protective factor for PTSD symptoms, which also includes the self-appreciation of maltreatment experience.53 The attributional cognitive state types such as negative or positive cognitive concepts may also be associated with maladaptive states.25 Though victims of more severe trauma might have worse cognitive status, and therefore they may also have worse symptoms. However, the victims who adopt positive attributions are less likely to have adjustment difficulties.

On the other hand, less social support may make them more susceptible to post-traumatic stress symptoms.54 People who lack social support after maltreatment may perceive the world as a dangerous place, and themselves untrustworthy. This type of cognitive problem is the core thinking that forms CPTSD.53 These type of people is not willing to state what they have experienced in the first place because it is more difficult for them to do so. The experience of abuse makes it more difficult to get attention and support from others.

It is believed that family support would reduce the harm of maltreatment to victims since the sense of security from the family may prevent victims from hiding their emotions. The good family environment helps self-referential perception of disclosure abilities and therefore are properly processed, thereby reducing the impacts of maltreatment.26,55 The relationship between the family is often a broad set of interpersonal associations. Rather than just the support given by significant others like friends, previous studies have found that the types of cognitive state after maltreatment are associated with family relationships which are a wide range of interpersonal relationships rather than specific relationships. It involved appraisal and attribution of maltreatment and therefore could reduce associated stress symptoms.53

Thusadequate intervention after evaluation of possible risk factors for poor family support might be helpful to prevent the impacts of maltreatment. Poverty, unemployment or mental disorders of caregivers, conflicts between parents and children, and neurodevelopmental disorders among children that public health workers should introduce social resources or collaborate with specialists to work for. The intervention could include either individual/group, or hospital/community care to assist parents.56

Regarding the social support brought by friends or peers, it was previously believed that the provision of information can also reduce the possibility of post-traumatic stress symptoms, because providing information or suggestions, whether it is providing advice, guidance. There is an opportunity for people to reappraise the situation of stressful events, thereby reducing the chance of traumatic stress symptoms.25 However, our study indicated that the support provided by friends is not as useful as family support which can reduce the severity of traumatic stress symptoms. It can be inferred that the young people included in this study may not have yet formed their interpersonal networks, or they may not be very stable, so protection in young adulthood comes from family support rather than from friends. In addition, some study shows that friends may tend to tolerate the victim’s trauma-related negative thinking rather than challenge it like family members, so the protective effect of friends’ support on traumatic stress symptoms may be low temporally at the time of evaluation.57

Limitations

Our study finding was limited by the design of cross-sectional measurement, and the information collection method was through filling in the online questionnaire, not from the diagnosis in the interview. The generalization of our finding might be limited to the non-clinical population although the self-reported questionnaires have been used and considered reliable for the evaluation of risk/protective factors in public health. In addition, it might be factors other than family/friend support as the mediators in the relationship between maltreatment and PTSD/CPTSD symptoms. Among them, the composition of the subjects in the community may be relatively heterogeneous. Large sample size and follow-up studies are warranted to verify the results of this study.

Conclusion

Our findings provided insight into the relationship between CPTSD symptoms and childhood maltreatment. We also found that family support plays a protective role in comparison with support from other people’s relationships. Therefore, we recommend that mental health workers should include awareness of maltreatment and provide appropriate support to parents in their parenting abilities. A longitudinal study to investigate the role of social support in the development of mental symptoms after maltreatment experience is also warranted.

Supplementary Materials

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants: TSGH-D-112120 and 112-2314-B-016-018-MY3.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Defense Medical Center, Tri-Service General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. (Approval No: B202205006, Date: 26 Jan 2022).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients who agreed to take part in the study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – C.B.Y.; Design – C.B.Y.; Supervision – C.B.Y.; Resources – C.B.Y.; Materials – C.B.Y., S.H.C.; Data Collection and/or Processing – C.B.Y., S.H.C., Y.W.Z.; Analysis and/or Interpretation – C.B.Y., S.H.C.; Literature Search – C.B.Y., S.H.C., Y.W.Z.; Writing – C.B.Y., Y.W.Z.; Critical Review – C.B.Y.

Declaration of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1. Baldwin JR, Wang B, Karwatowska L, et al. Childhood maltreatment and mental health problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quasi-experimental studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180(2):117 126. ( 10.1176/appi.ajp.20220174) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. UNICEF East Asia & Pacific. Maltreatment: prevalence, incidence and consequences in East Asia and the Pacific. 2012. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/eap/reports/child-maltreatment. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feng JY, Hwa HL, Shen ACT, Hsieh YP, Wei HS, Huang CY. Patterns and trajectories of children’s maltreatment experiences in Taiwan: latent transition analysis of a nationally representative longitudinal study. Child Abuse Negl. 2023;135:105951. ( 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105951) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fu H, Feng T, Qin J, et al. Reported prevalence of childhood maltreatment among Chinese college students: a systematic review and metaanalysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0205808. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0205808) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Higgins DJ, Mathews B, Pacella R, et al. The prevalence and nature of multi-type child maltreatment in Australia. Med J Aust. 2023;218(suppl 6):S19 S25. ( 10.5694/mja2.51868) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hanlon P, McCallum M, Jani BD, McQueenie R, Lee D, Mair FS. Association between childhood maltreatment and the prevalence and complexity of multimorbidity: a cross-sectional analysis of 157,357 UK Biobank participants. J Comorb. 2020;10:1 12. ( 10.1177/2235042X10944344) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tindberg Y, Janson S, Jernbro C. Unintentional injuries are associated with self-reported child maltreatment among Swedish adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(7):5263. ( 10.3390/ijerph20075263) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huang SH, Lin IJ, Yu PC, et al. Exposure of child maltreatment leads to a risk of mental illness and poor prognosis in Taiwan: a nationwide cohort study from 2000 to 2015. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4803. ( 10.3390/ijerph19084803) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Janiri D, Sani G, Danese E, et al. Childhood traumatic experiences of patients with bipolar disorder type I and type II. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:92 97. ( 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.055) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kapoor S, Freitag S, Bradshaw J, Valencia GT, Lamis DA. The collective impact of childhood abuse, psychache, and interpersonal needs on suicidal ideation among individuals with bipolar disorder: a discriminant analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2023;141:106202. ( 10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kothapalli J, Munikumar M, Kena T, et al. Childhood abuse and anxiety, depression - an interprofessional approach to optimize knowledge and awareness among young adult health professions students of Arunachal Pradesh, India. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2023;233:103837. ( 10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.103837) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Villodas MT, Morelli NM, Hong K, et al. Differences in late adolescent psychopathology among youth with histories of co-occurring abuse and neglect experiences. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;120:105189. ( 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105189) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Contractor AA, Brown LA, Weiss NH. Relation between lifespan polytrauma typologies and post-trauma mental health. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;80:202 213. ( 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.10.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hyland P, Murphy J, Shevlin M, et al. Variation in post-traumatic response: the role of trauma type in predicting ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD symptoms. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(6):727 736. ( 10.1007/s00127-017-1350-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Palic S, Zerach G, Shevlin M, Zeligman Z, Elklit A, Solomon Z. Evidence of complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) across populations with prolonged trauma of varying interpersonal intensity and ages of exposure. Psychiatry Res. 2016;246:692 699. ( 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.062) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Karatzias T, Murphy P, Cloitre M, et al. Psychological interventions for ICD-11 complex PTSD symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2019;49(11):1761 1775. ( 10.1017/S0033291719000436) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ford JD. Progress and limitations in the treatment of complex PTSD and developmental trauma disorder. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2021;8(1):1 17. ( 10.1007/s40501-020-00236-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cluver L, Fincham DS, Seedat S. Posttraumatic stress in AIDS-orphaned children exposed to high levels of trauma: the protective role of perceived social support. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(2):106 112. ( 10.1002/jts.20396) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fereidooni F, Daniels JK, Lommen MJJ. Childhood maltreatment and Revictimization: a systematic literature review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024;25(1):291 305. ( 10.1177/15248380221150475) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zamir O. Childhood maltreatment and relationship quality: a review of type of abuse and mediating and protective factors. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2022;23(4):1344 1357. ( 10.1177/1524838021998319) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bennett EM, Gray P, Lau JYF. Early life maltreatment and adolescent interpretations of ambiguous social situations: investigating interpersonal cognitions and emotional symptoms. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2023;16(1):1 8. ( 10.1007/s40653-022-00469-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braithwaite EC, O’Connor RM, Degli-Esposti M, Luke N, Bowes L. Modifiable predictors of depression following childhood maltreatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(7):e1162. ( 10.1038/tp.2017.140) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Münzer A, Ganser HG, Goldbeck L. Social support, negative maltreatment-related cognitions and posttraumatic stress symptoms in children and adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;63:183 191. ( 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Struck N, Krug A, Feldmann M, et al. Attachment and social support mediate the association between childhood maltreatment and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2020;273:310 317. ( 10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.041) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leifker FR, Marshall AD. The impact of negative attributions on the link between observed partner social support and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity. J Anxiety Disord. 2019;65:19 25. ( 10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.05.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Köhler M, Schäfer H, Goebel S, Pedersen A. The role of disclosure attitudes in the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity and perceived social support among emergency service workers. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:602 610. ( 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dvir Y, Ford JD, Hill M, Frazier JA. Childhood maltreatment, emotional dysregulation, and psychiatric comorbidities. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):149 161. ( 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lavoie J, Williams S, Lyon TD, Quas JA. Do children unintentionally report maltreatment? Comparison of disclosures of neglect versus sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;133:105824. ( 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105824) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beblo T, Driessen M, Dehn L. Memory deficits in patients with major depression: yes, they are trying hard enough! Expert Rev Neurother. 2020;20(5):517 522. ( 10.1080/14737175.2020.1754799) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Corrigan JP, Hanna D, Dyer KFW. Investigating predictors of trauma induced data-driven processing and its impact on attention bias and free recall. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2020;48(6):646 657. ( 10.1017/S135246582000048X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krause-Utz A, Walther JC, Kyrgiou AI, et al. Severity of childhood maltreatment predicts reaction times and heart rate variability during an emotional working memory task in borderline personality disorder. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2022;13(1):2093037. ( 10.1080/20008198.2022.2093037) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(2):169 190. ( 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cheng YC, Chen CH, Chou KR, Kuo PH, Huang MC. Reliability and factor structure of the Chinese version of childhood trauma questionnaire-short form in in patients with substance use disorder. Taiwan J Psychiatry. 2018;32(1):52 62. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cloitre M, Shevlin M, Brewin CR, et al. The International Trauma Questionnaire: development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(6):536 546. ( 10.1111/acps.12956) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chiu SH, Chiu YL, Yeh CB. The psychometric properties of the international trauma questionnaire in Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. 2023;33(1):28 37. ( 10.5152/pcp.2023.22572) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489 498. ( 10.1002/jts.22059) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fung HW, Chan C, Lee CY, Ross CA. Using the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) checklist for DSM-5 to screen for PTSD in the Chinese context: a pilot study in a psychiatric sample. J Evid Based Soc Work (2019). 2019;16(6):643 651. ( 10.1080/26408066.2019.1676858) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561 571. ( 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lu ML, Che HH, Chang SW, Shen WW. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Taiwan J Psychiatry. 2002;16(4):301 310. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893 897. ( 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Che HH, Lu ML, Chen HC, Chang SW, Lee YJ. Validation of the Chinese version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Formos J Med. 2006;10(4):447 454. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30 41. ( 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chou KL. Assessing Chinese adolescents’ social support: the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Pers Individ Dif. 2000;28(2):299 307. ( 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00098-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fry D, McCoy A, Swales D. The consequences of maltreatment on children’s lives: a systematic review of data from the East Asia and Pacific Region. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012;13(4):209 233. ( 10.1177/1524838012455873) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wagner-Skacel J, Riedl D, Kampling H, Lampe A. Mentalization and dissociation after adverse childhood experiences. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):6809. ( 10.1038/s41598-022-10787-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Herr NR, Rosenthal MZ, Geiger PJ, Erikson K. Difficulties with emotion regulation mediate the relationship between borderline personality disorder symptom severity and interpersonal problems. Personal Ment Health. 2013;7(3):191 202. ( 10.1002/pmh.1204) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Teicher MH, Samson JA. Annual Research Review: enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57(3):241 266. ( 10.1111/jcpp.12507) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cai J, Li J, Liu D, et al. Long-term effects of childhood trauma subtypes on adult brain function. Brain Behav. 2023;13(5):e2981. ( 10.1002/brb3.2981) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pollmann JB, Nielsen ABS, Andersen SB, Karstoft KI. Changes in perceived social support and PTSD symptomatology among Danish army military personnel. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(7):1389 1398. ( 10.1007/s00127-021-02150-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gottvall M, Vaez M, Saboonchi F. Social support attenuates the link between torture exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder among male and female Syrian refugees in Sweden. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2019;19(1):28. ( 10.1186/s12914-019-0214-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang Y, Bao Y, Liu L, Ramos A, Wang Y, Wang L. The mediating effect of self-efficacy in the relationship between social support and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among patients with central system tumors in China: a cross-sectional study. Psychooncology. 2015;24(12):1701 1707. ( 10.1002/pon.3838) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kalin NH. Trauma, resilience, anxiety disorders, and PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(2):103 105. ( 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20121738) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Woodward MJ, Eddinger J, Henschel AV, Dodson TS, Tran HN, Beck JG. Social support, posttraumatic cognitions, and PTSD: the influence of family, friends, and a close other in an interpersonal and non-interpersonal trauma group. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;35:60 67. ( 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.09.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ullman SE, Relyea M. Social support, coping, and posttraumatic stress symptoms in female sexual assault survivors: a longitudinal analysis. J Trauma Stress. 2016;29(6):500 506. ( 10.1002/jts.22143) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Duax JM, Bohnert KM, Rauch SA, Defever AM. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, levels of social support, and emotional hiding in returning veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(4):571 578. ( 10.1682/JRRD.2012.12.0234) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Altafim ERP, Magalhães C, Linhares MBM. Prevention of child maltreatment: integrative review of findings from an evidence-based parenting program. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024;25(3):1938 1953. ( 10.1177/15248380231201811) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fredman SJ, Vorstenbosch V, Wagner AC, Macdonald A, Monson CM. Partner accommodation in posttraumatic stress disorder: initial testing of the Significant Others’ Responses to Trauma Scale (SORTS). J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(4):372 381. ( 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.04.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a