Abstract

Artificial intelligence systems (AISs) gain relevance in dentistry, encompassing diagnostics, treatment planning, patient management, and therapy. However, questions about the generalizability, fairness, and transparency of these systems remain. Regulatory and governance bodies worldwide are aiming to address these questions using various frameworks. On March 13, 2024, members of the European Parliament approved the Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA), which emphasizes trustworthiness and human-centeredness as relevant aspects to regulate AISs beyond safety and efficacy. This review presents the AIA and similar regulatory and governance efforts in other jurisdictions and lays out that regulations such as the AIA are part of a complex ecosystem of interdependent and interwoven legal requirements and standards. Current efforts to regulate dental AISs require active input from the dental community, with participation of dental research, education, providers, and patients being relevant to shape the future of dental AISs.

Keywords: algorithms, biomedical ethics, Europe, machine learning, regulation, deep learning

Introduction

An artificial intelligence system (AIS) is “a machine-based system that can, for a given set of human-defined objectives, make predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing real or virtual environments” (OECD 2023). The interest in AISs in dentistry has been growing exponentially over the past years (Mörch et al. 2021; Mohammad-Rahimi et al. 2023). Dental AISs were proposed for tasks ranging from diagnostics to treatment planning, therapy support, practice and patient management, and dental research (e.g., for support materials development) and education (Li et al. 2022; Felsch et al. 2023). Notably, the application of AIS raises concerns about their quality, generalizability, robustness, fairness, and transparency, and regulatory bodies worldwide are developing and implementing frameworks to govern the use of AISs.

The complexities in regulating AISs are rooted in the pace of technological development; regulators struggle to establish frameworks in time and are also challenged to enforce them given the shortage of regulatory workforce equipped with sufficient expertise in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) (Hwang et al. 2019; Bates 2023). AISs further rely on sensitive data and the trust of patients, practitioners, and further stakeholders (Schwendicke et al. 2021; Hines et al. 2023; Rokhshad et al. 2023). On March 13, 2024, members of the European Parliament approved the Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA), which provides governance for any device that includes AI and “promote[s] the uptake of human centric and trustworthy artificial intelligence (AI) while ensuring a high level of protection of health, safety, fundamental rights” (European Commission 2024).

Regulatory frameworks are often neglected within the dental community, while they have broad relevance for manufacturers, researchers, educators, and clinicians alike. For researchers and manufacturers, regulation shapes the landscape into which any research or developed product shall be implemented; early consideration of regulatory aspects will help implementation and reduce the widely known implementation gap. Educators will need to consider regulatory frameworks both during the execution of clinical education and when developing their educational content. Providing knowledge to dental students about the real-life frameworks regulating clinical dentistry is of obvious importance. Last, clinicians require knowledge to adhere to any such frameworks and not accidently violate them. In the context of this article, the AIA imposes strategic points toward the development of dental AI, and requirements that clinically applicable AIS in dentistry will need to follow.

This review presents an overview of the AIA and describes how dental AISs will be regulated within the European Union (EU) through the funneling requirements of the AIA (Ma et al. 2022). As current efforts to regulate AISs require input from the dental community, the review is also a call for active engagement of dental stakeholders in shaping the regulatory landscape for dental AI.

AIA in the Context of Trustworthiness

The question of AIS trustworthiness has been a focus for years (Burden and Stenberg 2022), and trust (among other factors, such as expected usefulness and performance) and general attitudes toward technology (Kelly et al. 2023) have been found to significantly affect the willingness to use AISs. Trustworthiness of AISs is particularly relevant given the known biases of AISs as well as the high risk of automation bias of human AIS users (Cummings, 2004; Zerilli et al. 2022). Given this risk, untrustworthy (biased) AISs may lead to significant health decisions to the detriment of patients and/or the health care system.

Major international players have issued declarations emphasizing the necessity of regulating AISs to increase trustworthiness. The 2023 US Executive Order for Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence set new standards for AI safety, privacy protection, equity, civil rights, consumer and worker defense, innovation promotion, and global leadership, and it aims to establish an environment where AI serves the public good while safeguarding human rights, privacy, and security (The White House 2023). The Bletchley Declaration, signed by 28 governments and the EU, similarly emphasized the need for international cooperation in addressing AI-related issues (Bletchley 2023).

The AIA preceded most of these statements and focuses on “building an ecosystem of trust” for users, developers, and deployers, with dental AI further being regulated by mandatory provisions along the “triangle of trust” of (1) conformity assessment, which ensures responsible development and qualitative implementation; (2) national authorities’ role in overseeing market surveillance, enforcing AIA requirements, and fostering innovation through regulatory sandboxes; and (3) harmonized standards, which provide guidelines to comply with the AIA (Burden and Stenberg 2022).

The original draft of the AIA by the European Commission outlined 7 key requirements, all related and expected to foster trust in AISs (European Commission 2019): (1) human agency and oversight; (2) technical robustness and safety; (3) privacy and data governance; (4) transparency; (5) diversity, nondiscrimination, and fairness; (6) societal and environmental well-being; (7) and accountability. The US Executive Order reflects these requirements, demanding AISs to be “Safe and Effective Systems,” provide “Algorithmic Discrimination Protections,” ensure “Data Privacy,” allow “Notice and Explanation,” and enforce “Human Alternatives, Consideration, and Fallback.”

In the following sections, we will demonstrate the relevance of the AIA for the dental community and will then present the increasingly granular funnel of requirements that future dental AISs will have to pass, being regulated as both a dental device and an AIS. Finally, this article will discuss how this regulatory approach is evolving across the globe and how it will affect dentistry. It should be noted that our working objective was to present the philosophy of the AIA and the challenges that it will represent for the dental community. Providing examples of “good” or “bad” dental AIS according to the criteria laid out by the AIA was not our focus; also as an assessment is impossible in the absence of any clinical or technical documentation.

Requirements as a European Medical Device

The AIA is conceptually and fundamentally structured around a risk-based approach. It categorizes AISs into 4 distinct levels based on their potential risks: unacceptable (prohibited) risk, high risk (most clinically used dental AISs will fall into this category), limited risk, and minimal risk. Each category corresponds to a different degree of requirements and controls. Such an approach serves the dual purpose of promoting the uptake of AISs while adequately addressing the associated risks, and it draws on the principle of proportionality (Mahler 2022). The AIA further emphasizes the need for legal and ethical evaluations, including considerations of fundamental rights, data privacy, and nondiscrimination, which is similar to the data protection impact assessment found in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Mahler 2022).

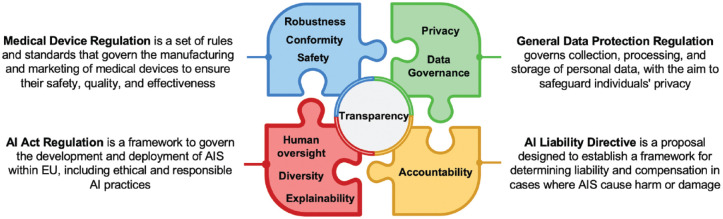

Notably, the AIA is an original but not totally independent document. It is linked to and embedded into a broader puzzle of European regulations, directives, and standards (Ma et al. 2022), which provide guidance on aspects such as data protection (e.g., the GDPR), medical device requirements (e.g., the Medial Device Regulation [MDR]), or liabilities around AI (e.g., the currently proposed AI Liability Directive [AILD]); these are therefore not specifically addressed within the AIA itself (Ma et al. 2022) (Fig.). For instance, the GDPR established a framework for data privacy promoting responsible use of data and safeguarding individuals’ rights. In the context of AISs, the need for a clear consent mechanism for collecting and processing personal data, robust data protection measures, and adherence to the principles of data minimization, purpose limitation, and individuals’ rights to access and delete their data are relevant examples of regulation coming from the GDPR. Procedurally, the AIA shares a range of commonalities with the MDR in requiring the demonstration of product safety and conformity, including risk management (AIA, Article 9) and technical documentation (AIA, Article 11) toward third parties (e.g., the European notified bodies). Similarly, postmarket monitoring of AISs described in the MDR is also planned within the AIA (AIA, Article 13) (European Commission 2024). The AILD aims to reinforce the accountability of actors by defining the responsibilities and liabilities of AISs not yet managed by civil liability. It acknowledges the responsibilities of both AIS users and providers, and it mirrors the liability regulation traditionally associated with hardware technologies and their manufacturers.

Figure.

Overview of how the Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) fits into the puzzle of governance established or proposed by the European Union.

Specific Requirements for Trustable Dental AISs

The AIA is a key document regarding the deployment of AISs in Europe. In the present review, we focus on 3 points that are most important for our community to ensure trust in dental AISs: transparency, explainability, and human-centeredness.

Transparency means disclosing any information along an AIS’s life cycle, including design purposes, data sources, hardware requirements, configurations, working conditions, expected usage, and system performance to a third party. In a complementary way, transparency also demands explainability (Kassekert et al. 2022; Ma et al. 2022). Explainability corresponds to the ability of an AIS to be able to provide information on the factors (image features, numerical variables) contributing to a particular decision in a way that is understandable and interpretable by the user. Explainability is 1 main key to creating trust between the different actors. Article 13 of the AIA mandates transparency and explainability to allow an individual to understand and interpret an AIS’s prediction, observation, or decision (Onitiu 2023; European Commission 2024).

Human-centeredness is implemented by enforcing human oversight (Onitiu 2023), as fleshed out in Articles 14 and 29 of the AIA (European Commission 2024), which aims at preventing or minimizing risks to health, safety, or fundamental rights that may emerge when high-risk AI systems are used in accordance with their intended purpose or under conditions of reasonably foreseeable misuse (Enqvist 2023). Article 14 further indicates that AISs shall be effectively overseen by natural persons, considering the risk of automation bias. Humans shall be able to interact with the AIA and to self-assess or challenge it. The World Health Organization (WHO) guidance on ethics and governance of AI for health (World Health Organization 2021) recommends the application of a “human warranty,” an a priori evaluation of an AIS by patients and clinicians. The French National Advisory Ethics Council for Health and Life Sciences (CCNE 2022) proposed to organize meetings involving all stakeholders (providers, deployers, patients, and experts) to provide such human warranty.

Further aspects of human-centeredness include diversity and fairness (Li et al. 2023). AISs have been found to potentially increase the marginalization of vulnerable groups and discrimination. The AIA demands that AISs should be made accessible to everyone, regardless of any disabilities or origins, and over their entire life cycle. On a macro level, the AIA also touches on societal and environmental well-being and sustainability.

This vision of human-centered AI is also found in the recent US Executive Order, which specifies that users should have the option to opt out of the AIS in favor of human alternatives when appropriate. Moreover, users should be able to get help from a human in case automated systems seem to malfunction, using a clear process for fallback and escalation.

Challenges and Questions for Dental AISs

Several challenges and questions emanate from the AIA. The first pertains to its reliance on third parties to certify conformity, as these have been burdened and overstretched for a period already, leading to delays in certifications. It is feared and conceivable that the additional extensive regulation required by the AIA will introduce further bottlenecks at the risk of slowing down dental research and innovation (Kassekert et al. 2022; Stegmann et al. 2023).

Second, the AIA challenges dental AI developers as well as regulators. While the current draft of the AIA provides some examples to introduce transparency and oversight in dental AI (such as the option of manually adjusting AI findings, the ability to switch off any AI input at any time, or the described requirement for feedback when an AIS seems to malfunction) (Enqvist 2023), there is, overall, limited guidance about the evaluation of these criteria in dentistry, which opens the way to further research in this area.

Third, the AIA only limitedly reflects the recently introduced (generative) foundation models, including large language models. Notably, these models are known to “hallucinate” (i.e., produce false content that is not distinguishable from true content without deep domain knowledge), with potentially grave consequences, particularly in medicine (Gilbert et al. 2023). Such models will require a particular focus on transparency, while it is not clear how exactly this should be realized and certified. The AIA also pays particular attention to these models, as they come with so-called systemic risk given the potentially large number of users and the resulting possible widespread harm to the European population. When an AIS is considered to present this type of risk, the AIA proposes a series of measures to strengthen control of the system (European Commission 2024). Dental research should move beyond pure assessment of these models (e.g., for dental education or patient communication) and aim to systematically gauge the associated potential risk emanating from these systems, as such risk mapping would then allow the development of clinical or technical mitigation measures.

Relevance for the Dental Community

Dental AISs may reduce administrative burden, thereby increasing time devoted to patient care and communication, improving diagnostic accuracy, and allowing more targeted, safer, and better care at lower costs (Ayers et al. 2023). However, they could also provide inaccurate or misleading information, potentially leading to serious dental consequences. Dental researchers, industry, educators, clinicians, and further stakeholders are called to embrace the outlined regulatory requirements and jointly act toward trustworthy, generalizable, fair, transparent, and human-centered dental AI. This review calls for an active engagement of the dental community.

(1) Data protection and governance, fairness, or diversity should be actively considered when dental researchers are developing and evaluating AISs in dentistry. The current “extractive” model of data collection is under increasing scrutiny, as it may promote inequality, with data donors not participating in their data donation and convenience sampling affecting representativeness and generalizability, fostering unfairness. Innovative approaches to data collection, including incentivization and participation of data donors, along with safeguards toward data representativeness, generalizability, and fairness, should be established. Aspects of data protection and accessibility will need to be balanced, and concepts of data sharing or decentralized training (such as federated learning) should be embraced and implemented given the difficulty in anonymizing and pooling dental data (Rischke et al. 2022; Schneider et al. 2023).

(2) The community should strive to develop criteria, processes, and platforms for assessing AISs. Benchmarking dental AISs against representative and layered data sets, collected under considerations of the AIA requirements and so forth, should be established (ITU/WHO/WIPO 2023). Large-scale collaborative real-world research may be needed for this purpose and also to demonstrate that the performance of AISs does not degrade when confronted with new populations or deployed in new regions.

(3) The concept of uncertainty, inherent in any clinical diagnosis, should be focused on in more depth from both a technical and a usability perspective (Kang et al. 2021); this relates to both image analysis (e.g., in dental radiology) and prediction models as part of an AIS (e.g., AIS predicting tooth loss). Notably, interpreting such uncertainty estimates requires the dental community to build sufficient data literacy skills.

(4) The call for transparency comes with the requirement of explainable dental AISs, transforming them from “black boxes to glass boxes” (Rai 2020). Explainability has been successfully developed for dental computer vision tasks (image analysis), while text or speech remains more challenging. Dental research should actively contribute to the field, as domain knowledge will be needed to provide clinically useful mechanisms for explainability.

(5) Human oversight and human-centeredness of AISs, along with wider calls for societal and overall benefits, are new requirements. The risks of automation bias will need to be addressed when conforming to these new requirements (Parikh et al. 2019). Research is needed to investigate how dental AIS affects clinical decision-making, especially toward automation bias, and how to ensure that users continue to critically appraise an AI output against the clinical (or education, scientific, etc.) rationale and experience. One frequently discussed method to reduce automation bias is confirmation loops, while any such loop may decrease the usability of the AIS.

(6) Societal and environmental aspects, including sustainability, are mentioned in the AIA, but remain vague and will, for the foreseen future, only limitedly be enforceable. For dentistry, research technologies employing AI (such as material informatics) may positively affect sustainability (Yamaguchi et al. 2023). Generally, dental AISs should be scrutinized against the WHO’s Sustainable Development Goals (Ducret et al. 2022).

(7) The question of educating dental professionals toward AISs remains unaddressed by regulation. However, the first steps have been made in dental education, for example, by developing a core curriculum on AI in dentistry (Schwendicke et al. 2023), as well as by assessing the implementation and application of AISs in dental education (Ali et al. 2023).

Conclusion

Questions about the generalizability, fairness, and transparency of AISs have been raised, and regulatory and governance bodies worldwide are aiming to address these using various frameworks. Beyond safety and efficacy, trustworthiness and human-centeredness are increasingly seen as relevant aspects when regulating AISs. The AIA and similar regulatory and governance efforts in other jurisdictions mirror these sentiments and will affect dental AI research and development, as well as clinical, educational, and scientific implementation of AISs. The dental community needs to actively contribute to the evolving and increasingly complex regulatory and governance landscape, being an actor in this change while promoting an environment of trust and societal benefit of dental AISs.

Author Contributions

M. Ducret, F. Schwendicke, Contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, or interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; E. Wahal, D. Gruson, S. Amrani, R. Raphael, M. Mouncif-Moungache, contributed to data acquisition, analysis, or interpretation, drafted the manuscript. All authors have their final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: This study did not require ethical approval.

ORCID iDs: M. Ducret  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5462-6258

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5462-6258

F. Schwendicke  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1223-1669

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1223-1669

References

- Ali K, Barhom N, Tamimi F, Duggal M. 2023. ChatGPT—a double-edged sword for healthcare education? Implications for assessments of dental students. Eur J Dent Educ. 28(1):206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers JW, Poliak A, Dredze M, Leas EC, Zhu Z, Kelley JB, Faix DJ, Goodman AM, Longhurst CA, Hogarth M, et al. 2023. Comparing physician and artificial intelligence chatbot responses to patient questions posted to a public social media forum. JAMA Intern Med. 183(6):589–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DW. 2023. How to regulate evolving AI health algorithms. Nat Med. 29(1):26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bletchley 2023. The Bletchley declaration by countries attending the AI safety summit, 1–2 November 2023 [accessed 2023 Dec 15]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ai-safety-summit-2023-the-bletchley-declaration/the-bletchley-declaration-by-countries-attending-the-ai-safety-summit-1-2-november-2023.

- Burden H, Stenberg S. 2022. Regulating trust—an ongoing analysis of the AI Act, RISE Rep. 2022138 ISBN. ISBN 978-9, RISE Research Institutes of Sweden; [accessed 2024 May 23]. https://ri.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1716437&dswid=-1151. [Google Scholar]

- CCNE. 2022. Joint opinion Opinion no.141 CCNE & Opinion no.4 CNPEN: medical diagnosis and artificial intelligence: ethical issues [accessed 2023 Dec 15]. https://www.ccne-ethique.fr/en/publications/joint-opinion-opinion-no141-ccne-opinion-no4-cnpen-medical-diagnosis-and-artificial.

- Cummings M. 2004. Automation bias in intelligent time critical decision support systems. In: AIAA 1st Intelligent Systems Technical Conference. Reston, VA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics; [accessed 2024 May 23]. https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/6.2004-6313. [Google Scholar]

- Ducret M, Mörch CM, Karteva T, Fisher J, Schwendicke F. 2022. Artificial intelligence for sustainable oral healthcare. J Dent. 127:104344. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enqvist L. 2023. ‘Human oversight’ in the EU Artificial Intelligence Act: what, when and by whom? Law Innov Technol. 15(2):508–535. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2019. Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI, European Commission [accessed 2023 Dec 15]. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai.

- European Commission. 2024. European Parliament legislative resolution of 13 March 2024 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on laying down harmonised rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain Union Legislative Acts [accessed 2024 Apr 8]. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2024-0138_EN.html#title2.

- Felsch M, Meyer O, Schlickenrieder A, Engels P, Schönewolf J, Zöllner F, Heinrich-Weltzien R, Hesenius M, Hickel R, Gruhn V, et al. 2023. Detection and localization of caries and hypomineralization on dental photographs with a vision transformer model. NPJ Digit Med. 6(1):198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert S, Harvey H, Melvin T, Vollebregt E, Wicks P. 2023. Large language model AI chatbots require approval as medical devices. Nat Med. 29(10):2396–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines PA, Herold R, Pinheiro L, Frias Z, Arlett P. 2023. Artificial intelligence in European medicines regulation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 22(2):81–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang TJ, Kesselheim AS, Vokinger KN. 2019. Lifecycle regulation of artificial intelligence- and machine learning-based software devices in medicine. JAMA. 322(23):2285–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITU/WHO/WIPO. 2023. Global Initiative on AI for Health [accessed 2023 Dec 15]. https://giai4h.org/.

- Kang DY, DeYoung PN, Tantiongloc J, Coleman TP, Owens RL. 2021. Statistical uncertainty quantification to augment clinical decision support: a first implementation in sleep medicine. NPJ Digit Med. 4(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassekert R, Grabowski N, Lorenz D, Schaffer C, Kempf D, Roy P, Kjoersvik O, Saldana G, ElShal S. 2022. Industry perspective on artificial intelligence/machine learning in pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf. 45(5):439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S, Kaye S-A, Oviedo-Trespalacios O. 2023. What factors contribute to the acceptance of artificial intelligence? A systematic review. Telemat Informatics. 77:101925. [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Sakai T, Tanaka A, Ogura M, Lee C, Yamaguchi S, Imazato S. 2022. Interpretable AI explores effective components of CAD/CAM resin composites. J Dent Res. 101(11):1363–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Qi P, Liu B, Di S, Liu J, Pei J, Yi J, Zhou B. 2023. Trustworthy AI: From Principles to Practices. ACM Comput Surv. 55(9):1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Schneider L, Lapuschkin S, Achtibat R, Duchrau M, Krois J, Schwendicke F, Samek W. 2022. Towards trustworthy AI in dentistry. J Dent Res. 101(11):1263–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler T. 2022. Between risk management and proportionality: the risk-based approach in the EU’s artificial intelligence act proposal. Swedish Law Informatics Res Inst. 2021:246–267. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad-Rahimi H, Rokhshad R, Bencharit S, Krois J, Schwendicke F. 2023. Deep learning: A primer for dentists and dental researchers. J Dent. 130:104430. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2023.104430. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36682721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mörch CM, Atsu S, Cai W, Li X, Madathil SA, Liu X, Mai V, Tamimi F, Dilhac MA, Ducret M. 2021. Artificial intelligence and ethics in dentistry: a scoping review. J Dent Res. 100(13):1452–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2023. Updates to the OECD’s definition of an AI system explained [accessed 2024 May 23]. https://oecd.ai/en/wonk/ai-system-definition-update.

- Onitiu D. 2023. The limits of explainability & human oversight in the EU Commission’s proposal for the regulation on AI—a critical approach focusing on medical diagnostic systems. Inf Commun Technol Law. 32(2):170–188. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh RB, Teeple S, Navathe AS. 2019. Addressing bias in artificial intelligence in health care. JAMA. 322(24):2377–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai A. 2020. Explainable AI: from black box to glass box. J Acad Mark Sci. 48(1):137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Rischke R, Schneider L, Müller K, Samek W, Schwendicke F, Krois J. 2022. Federated learning in dentistry: chances and challenges. J Dent Res. 101(11):1269–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokhshad R, Ducret M, Chaurasia A, Karteva T, Radenkovic M, Roganovic J, Hamdan M, Mohammad-Rahimi H, Krois J, Lahoud P, et al. 2023. Ethical considerations on artificial intelligence in dentistry: a framework and checklist. J Dent. 135:104593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider L, Rischke R, Krois J, Krasowski A, Büttner M, Mohammad-Rahimi H, Chaurasia A, Pereira NS, Lee J-H, Uribe SE, et al. 2023. Federated vs local vs central deep learning of tooth segmentation on panoramic radiographs. J Dent. 135:104556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendicke F, Chaurasia A, Wiegand T, Uribe SE, Fontana M, Akota I, Tryfonos O, Krois J. 2023. Artificial intelligence for oral and dental healthcare: core education curriculum. J Dent. 128:104363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendicke F, Singh T, Lee J-H, Gaudin R, Chaurasia A, Wiegand T, Uribe S, Krois J. 2021. Artificial intelligence in dental research: checklist for authors, reviewers, readers. J Dent. 107:103610. [Google Scholar]

- Stegmann JU, Littlebury R, Trengove M, Goetz L, Bate A, Branson KM. 2023. Trustworthy AI for safe medicines. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 22:855–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The White House.2023. Executive order on the safe, secure, and trustworthy development and use of artificial intelligence [accessed 2023, Dec 15]. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/10/30/executive-order-on-the-safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence/.

- World Health Organization. 2021. Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health [accessed 2023 Dec 15]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029200.

- Yamaguchi S, Li H, Imazato S. 2023. Materials informatics for developing new restorative dental materials: a narrative review. Front Dent Med. 4:1123976. [Google Scholar]

- Zerilli J, Bhatt U, Weller A. 2022. How transparency modulates trust in artificial intelligence. Patterns. 3(4):100455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]