Abstract

Background: Nonbinary people experience marginalization through discrimination, rejection, microaggressions, and stigma as a result of not always conforming to societal gender norms embedded in the gender binary. There is limited research about how nonbinary Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) living in the United States navigate societally enforced binary gender norms, which is especially important to understand given how racism and Euro-colonization have enforced the gender binary. Better understanding the internal strategies nonbinary people use to cope, embody affirmation, and regulate emotions in response to marginalizing experiences could increase understanding of how to best prevent and address the health disparities experienced by nonbinary people.

Aim: Drawing on the practices of interrogating norms central to queer theory with a sensitization to racism and settler colonialism, this study aimed to identify a framework to understand nonbinary peoples’ processes of navigating gender norms internally through their lived experiences with an awareness of how context impacts these processes.

Method: This qualitative interview study utilized construcitivist grounded theory methodology, guided by queer theory. Twenty-one nonbinary individuals were interviewed over Zoom with 15 being BIPOC.

Results: Participants navigated binary gender norms internally by self-defining affirmative nonbinary ways of being, noticing affirmation in a chosen community that allowed them to experience existing authentically outside of binary gender norms, and internally connecting to an embodied, authentic sense of gender within themselves and in community with other nonbinary people. These internal processes were influenced by two contextual factors: societal and cultural expectations of gender; and the contextual impacts of holding multiple marginalized identities.

Discussion: Understanding the contexts of the gender binary, racism, and cissexism that impact nonbinary people on a daily basis is crucial for mental health professionals, researchers, policy makers, and creators of gender inclusive education and support programs to support and affirm nonbinary people.

Keywords: BIPOC, discrimination, embodiment, gender binary, grounded theory, nonbinary

"It’s Like a Happy Little Affirmation Circle": A Grounded Theory Study of Nonbinary Peoples’ Internal Processes for Navigating Binary Gender Norms

Nonbinary gender identities are those that do not exclusively fall within the gender binary (i.e. Euro-colonized societal construct that men and women are the only two genders; a guiding societal ideology that is enforced in many Euro-colonized countries/Western societies; Chang et al., 2018; Imani, 2021; West & Zimmerman, 1987). Nonbinary people may experience gender as completely outside of the gender binary, somewhere between man and woman, both man and woman, or not experience themselves as having a gender at all (American Psychological Association, 2015; Chang et al., 2018). Nonbinary people experience marginalization through discrimination, rejection, microaggressions, and stigma as a result of not always conforming to societal gender norms embedded in the gender binary (e.g. that one must have a gender expression that aligns with their gender assigned at birth), and experience depression and anxiety at higher rates than binary transgender and cisgender people as a result (Budge et al., 2014; Harrison et al., 2012; Matsuno & Budge, 2017; Puckett et al., 2023). When considering the negative impacts this marginalization has on the mental health of nonbinary people, the increase in, and presence of, anti-transgender legislation in the United States (U.S.) is especially concerning (Tebbe et al., 2022).

To date, very few studies have addressed how nonbinary people cope with these experiences of marginalization and the majority of those that do combine binary transgender and nonbinary samples, which ignores the additional challenges experienced by nonbinary people who are navigating a U.S. society that privileges the gender binary. Further, very little is known about how nonbinary Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC)1 living in the U.S. navigate societally enforced binary gender norms, which is especially important to understand given how racism and Euro-colonization have enforced the gender binary (Bederman, 1995; Carter, 2007; Somerville, 2000). Better understanding the internal strategies nonbinary people use to cope, embody affirmation, and regulate emotions in response to marginalizing experiences could increase understanding of how to best prevent and address the health disparities experienced by nonbinary people. For example, scholars have begun to find that nonbinary people navigate societally imposed binary gender norms in ways that can contribute to their overall well-being such as experiencing self-affirmation of their gender (Beischel et al., 2022; Bradford et al., 2019; Bradford & Catalpa, 2019; McGuire et al., 2019). Given the unique stressors that nonbinary people experience, the purpose of the current study is to begin to address these gaps by exploring the internal processes (i.e. thought processes, emotional experiences) a racially diverse sample of nonbinary people in the U.S. use to navigate external binary gender norms in ways that contribute to their overall well-being.

Nonbinary gender identity in context

Nonbinary people in the U.S. are faced with developing their gender identity and existing in a societal context organized by cissexism that assumes binary genders are the norm, privileging cisgender people and marginalizing people who do not conform to the gender binary (Bauer et al., 2009; Matsuno & Budge, 2017). Nonbinary people often must navigate external expectations to perform gender in a binary prescribed way and/or cope with internalized messages of what “normal” cisgender or “normal” transgender identities look like (Bradford et al., 2019; Bradford & Syed, 2019; Croteau & Morrison, 2022). In a sample of 266 nonbinary individuals, scholars found that nonbinary people experience many forms of microaggressions, some being similar to those experienced by binary transgender people such as having their identity negated by others or seen as inauthentic and experiencing deadnaming (being called by one’s name given at birth rather than one’s gender-affirming, chosen name), as well as some microaggressions that are specific to nonbinary people such as experiencing exclusion from binary transgender people in transgender communities, and being referred to with binary gender terms that are incongruent with their nonbinary gender identities (Croteau & Morrison, 2022). Further, in qualitative studies, nonbinary people report pressure to medically transition to conform to binary gender norms, as well as a lack of representation in societal discourse and in the media (Bradford et al., 2019; Bradford & Syed, 2019; Fiani & Han, 2019). These pressures and lack of representation reflect the constructs of transnormativity (an ideological framework that legitimizes transgender people who medically transition and uphold binary gender norms; Johnson, 2016) and cisnormativity (a guiding societal ideology that assumes all people are/should be cisgender; Bauer et al., 2009). Transnormativity and cisnormativity have been documented as shaping experiences of nonbinary people by enforcing binary gender roles and the binary idea that gender expression has to be stable throughout the life course and align with normative expectations of gender identity (e.g. feminine people should wear dresses, masculine people should wear pants, and nonbinary people should be androgynous) as a way to confirm legitimacy of one’s gender identity (Bradford et al., 2019; Bradford & Syed, 2019; Fiani & Han, 2019). Nonbinary participants have expressed that these binary gender norms do not capture their experience of gender identity and that feeling de-legitimized by both cisgender and binary transgender people is a common experience (Bradford et al., 2019; Bradford & Syed, 2019; Fiani & Han, 2019). Thus, some studies have found that nonbinary people place a significant emphasis on being in community with similarly identified peers who are affirming of their experience of gender, especially when nonbinary people have multiple marginalized identities (Bradford & Syed, 2019; Fiani & Han, 2019).

Impacts of binary gender norms on mental health and Well-Being

The marginalizing, non-affirming, and microaggression experiences rooted in the enforcement of the gender binary faced by nonbinary people contribute to negative mental health outcomes linked to gender minority stress (Testa et al., 2015). The construct of gender minority stress—that transgender and nonbinary people experience additional stress and discrimination in daily life due to living in a society that privileges cisgender people (Testa et al., 2015)—is helpful for contextualizing how nonbinary people may respond to, and be affected by, the expectations of binary gender norms and discrimination based on gender identity. For example, studies have found that gender minority stress is associated with suicide attempts and depression in nonbinary samples (Brennan et al., 2017; Tebbe & Moradi, 2016; Valente et al., 2020). Additionally, more frequent experiences of nonbinary microaggressions are correlated with higher anxiety and depression, and lower self-esteem (Croteau & Morrison, 2022). While it is necessary to understand the impacts of marginalization on nonbinary peoples’ mental health, it is also important to note that nonbinary people experience joy and resilience connected to embodying their gender identity, as well as through support found in community with those who are affirming of nonbinary identities (Beischel et al., 2022; Bradford et al., 2019; Brennan et al., 2017).

In line with intersectionality theory, nonbinary people’s experiences of discrimination are unique and more frequent when they hold multiple minoritized identities due to various systemic structures of oppression operating simultaneously (e.g. both racism and sexism; Crenshaw, 1991; Lampe et al., 2020; Rood et al., 2016). For example, nonbinary BIPOC in qualitative studies have expressed that they are more vulnerable to discrimination and have greater experiences of overt discrimination in public spaces because of racism compared to White people (Rood et al., 2016); in the same vein, White nonbinary participants have expressed an awareness of racial privilege, which can afford them more safety even though they have a marginalized gender identity (Conlin et al., 2019; Rood et al., 2016). There is a need to better understand how various social identities inform how nonbinary people navigate gender norms and cope with discrimination and minority stress.

A few studies illustrate that nonbinary people may be able to beneficially navigate these marginalizing gender binary societal norms through internal experiences, such as feeling proud, comfortable, and affirmed in their gender identity (Beischel et al., 2022; Brennan et al., 2017). Some nonbinary participants in a recent study on gender euphoria (i.e. experiencing joy and congruency in one’s gender identity) described feeling comforted and joyful in knowing that they personally define their gender and are not defined by people’s perceptions of them, as well as moments of knowing that they are valid in their identity regardless of their gender expression (Beischel et al., 2022). In other qualitative studies, nonbinary participants have commented on the freedom and authenticity they feel from being nonbinary and the possibilities created for all people that come from diverse gender expressions and gender identities (Bradford et al., 2019; Bradford & Syed, 2019). More research is needed to further understand how nonbinary people experience joy and freedom in their gender identities and how these internal experiences inform ways of navigating contexts (e.g. daily interactions in relationships, workplaces, societal pressures) that enforce or support binary gender norms.

Theoretical frameworks

This study draws on a queer theory perspective with attention to the influence of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991), colonization and colonialism, systemic racism, and eugenics “science” to inform a constructivist grounded theory methodological approach (Bederman, 1995; Carter, 2007; Somerville, 2000). Queer theory fundamentally challenges binary and essentialist conceptualizations of gender and sex, and calls into question the ideologies that center cisgender, heterosexual, and monogamous people as “normal” (Butler, 1990; Tilsen, 2013; Warner, 1999). Through queer theory, gender is seen as discursively socially constructed through relationships in historical and cultural contexts (Butler, 1990). Central to this study, queer theory offers a framework for understanding the active process of resisting, constructing, and navigating gender and gender norms as the essence of queer theory is the questioning of what’s deemed as normal and who has the power to define it (Butler, 1990; Doty, 1993; Tilsen, 2013). In using constructivist grounded theory, this study aims to theorize about and explain how these active processes are engaged in by nonbinary people, expanding on the theoretical ideas of queer theory.

Importantly, many scholars have articulated that queer theory must be understood with an intersectional analysis as identities and experiences cannot be understood outside of their political nature and societal structures of privilege and oppression (e.g. racism, classism, ableism; Allen & Mendez, 2018; Crenshaw, 1991; Hammonds, 1997; Muñoz, 1999). Muñoz (1999) describes “disidentification” as a way queer BIPOC survive and live in oppressive systems that do not support their identities in multiple ways (e.g. racism, cissexism, heterosexism) by navigating, negotiating, and creating lives that allow for the re-working of queer theory to encompass the realities of holding a racially marginalized identity. Further, this study is centered in an understanding of how the ongoing project of European settler colonialism historically and currently shapes the construct of the gender binary in the U.S. and many Euro-colonized countries (Iantaffi, 2020; Imani, 2021). The purposes of this study acknowledge how colonization and settler colonialism have shaped the intertwined systems of racism and cissexism that fuel the centering of White, gender-conforming people and the marginalizing, oppressing, and harming of BIPOC, transgender, nonbinary, and gender non-conforming people (Bederman, 1995; Carter, 2007; Iantaffi, 2020; Imani, 2021; Somerville, 2000). By using constructivist grounded theory methods informed by queer theory, this study seeks to be sensitive to the multiple marginalized identities nonbinary BIPOC hold and aims to explain how nonbinary BIPOC may negotiate, resist, and question the gender binary in a both/and way that allows for identifying with what is useful in creating affirmative worlds and/or disidentify with what is oppressive, constricting, or does not acknowledge the reality of racism and the need to organize around racial identity for collective action (Muñoz, 1999; Tilsen, 2013).

Present study

Given the mental health challenges nonbinary experience in response to marginalization, gender minority stress, and enforcement of the gender binary, it is necessary to understand how nonbinary people cope with and navigate binary gender norms. Drawing on the practices of interrogating norms central to queer theory with a sensitization to racism and settler colonialism, this constructivist grounded theory study provides a framework to understand nonbinary peoples’ processes of navigating gender norms internally through their lived experiences. Understanding these processes will inform the development of competent and ethical clinical strategies for mental health professionals to use when working with nonbinary clients, as well as provide implications for researchers, policy makers, and creators of gender inclusive education and support programs. In order to expand on the existing literature that has identified possible internal coping strategies of self-affirmation and gender euphoria (Beischel et al., 2022; Brennan et al., 2017), we asked the following research questions to identify the internal processes nonbinary people use to navigate gender norms: a) What contextual factors inform the processes nonbinary people use to navigate binary gender norms internally? b) How do nonbinary people navigate binary gender norms internally?

Methods

This study utilized construcitivist grounded theory methodology, which seeks to understand processes and answer “how” questions (Charmaz, 2006; Creswell & Poth, 2018) and is often used when a theory does not exist to explain a phenomenon or experience among a group of people (Creswell & Poth, 2018). Constructivist grounded theory does not seek to gather in-depth understandings of phenomena, but intentionally follows flexible principles that rely on interpretive portrayals of data to understand the process that is happening among participants (Charmaz, 2006). Through co-constructing theory by interviewing participants and interpreting the data, constructivist grounded theory methods can be used to identify moments of change that have implications for practice (Charmaz, 2006).

Participant recruitment

This study was part of a larger project on nonbinary people’s relationships to gender norms, worldviews, and therapy preferences. Nonbinary participants were recruited with purposeful sampling through social media (i.e. Facebook, Reddit), followed by snowball sampling because nonbinary communities can be well-networked with connections to others who would be interested in participating (Creswell & Poth, 2018). The first author posted a recruitment flyer with information about the study on their personal Facebook page and allowed for Facebook users to share the posting to their own personal pages to broaden recruitment. The recruitment materials were also posted in a Facebook social group for transgender and nonbinary BIPOC as well as Reddit sub-thread for nonbinary people. To be eligible, participants needed to identify with a gender identity that is not cisgender or binary (e.g. nonbinary, genderqueer, genderfluid), be between the ages of 18-65, live in the U.S., and speak English. Cisgender people and binary transgender people were excluded.

Procedures

Interested participants clicked on an anonymous Qualtrics survey link to complete the informed consent, demographic questions, and contact information, which served as a screener for eligibility. Fifty-five people provided contact information indicating they were interested in being interviewed. Because nonbinary BIPOC are underrepresented in scholarly research, the authors chose to intentionally focus on interviewing as many BIPOC as possible. All 27 BIPOC who expressed interest in participating were contacted, 15 of which scheduled an interview. To reach the sample size of at least 20-30 people recommended by Creswell and Poth (2018) for grounded theory studies, the first author then contacted the first 10 White people who responded to schedule an interview, 6 of whom responded, resulting in 21 total interviews.

The 21 participants in this study ranged in age from 19- to 38-years-old (M = 23.24). All participants were nonbinary, which included genderfluid, bigender, and agender identities (see Table 1 for participant demographics). The sample was diverse in terms of racial identity (71% BIPOC), sexual orientation (33% Queer), education (38% held high school degrees), and income. All participants identified that they had an awareness they were not cisgender and/or that the gender binary did not fit their identities from between 1 year ago to “since childhood” (M = 8 years). The participant who responded, “since childhood” shared that they were aware of their gender identity for approximately 27 years.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n = 21).

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender Identity | Race | Sexual Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alex | 22 | Non-Binary | White | Gay |

| Amihan | 23 | Genderqueer, Non-Binary, Genderfluid | African American/ Black, Asian American/ Asian ,Biracial/Multiracial | Lesbian |

| Bea | 25 | Non-Binary | Asian/Asian American | Bisexual |

| Daya | 24 | Non-Binary | Asian/Asian American | Queer |

| Emerson | 32 | Genderqueer, Non-Binary | White | Queer |

| Fall | 28 | Graygender | White | Bisexual |

| Jayce | 26 | Genderfluid | African American/Black | Bisexual |

| Jin | 20 | Non-Binary | Asian/Asian American | Bisexual |

| Jinx | 24 | Non-Binary | African American/Black | Pansexual |

| Jomar | 25 | Non-Binary | Asian/Asian American | Queer |

| Lil | 20 | Non-Binary | Asian/Asian American | Lesbian |

| Michelle/ Michael |

25 | Bigender | White | Androsexual |

| Ouran | 25 | Non-Binary, Agender | Asian/Asian American, White | Asexual-Sapphic |

| Reese | 22 | Non-Binary,Genderfluid | White, Latinx/Latino(a)/Hispanic |

Queer |

| Rumra | 23 | Non-Binary | African American/ Black, Asian American/ Asian, Biracial/Multiracial | Queer |

| Rusty | 38 | Non-Binary | White | Bisexual |

| Sawyer | 19 | Demigender/Demigirl | White | Lesbian |

| Silver | 23 | Non-Binary | Asian/Asian American | Pansexual |

| Still | 24 | Non-Binary | Latinx/Latino(a)/Hispanic | Queer |

| Willow | 20 | Non-Binary, Agender | African American/ Black | Lesbian |

| YR | 25 | Non-Binary, Nonbinary femme | Latinx/Latino(a)/Hispanic | Queer |

Interview protocol

This study involved individual participant interviews that followed a semi-structured interview guide. The interview questions were constructed based on the existing literature and the authors’ experiences as people with privileged and marginalized identities who work with nonbinary people in various settings. Sample questions from the interview guide include, “What helped you resist and/or respond in an affirmative-to-you way to gender norms and expectations for the gender you were assigned at birth?” and, “What has your experience (e.g. emotional, cognitive, day-to-day) of navigating gender norms been like?”. The interview guide was pilot tested in the initial interview and adapted for flow and clarity for the remaining interviews.

All interviews were conducted by the first author through Zoom. The first author is a White, nonbinary, queer person who works with transgender and nonbinary people in therapeutic and research settings. The first author disclosed their nonbinary identity at the beginning of each interview to situate their intentions for centering nonbinary peoples’ experiences in hopes of using findings from the study to inform nonbinary inclusive mental health treatment approaches, research, and policy. Before starting the recording, participants chose a pseudonym and were given the option to change their Zoom name to their pseudonym. Interviews ranged from 37 to 82 min. Participants were compensated with a $25 Amazon gift card. This study was approved by a University Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

In line with the grounded theory practice of simultaneously collecting and analyzing data, as the first author conducted interviews, they reviewed the transcripts and debriefed with one member of the coding team to aid in theoretical sampling (Charmaz, 2006). In constructivist grounded theory, theoretical sampling is used to refine and deepen the categories that are tentatively being formed through the process of going back and forth between analyzing data being collected and then intentionally collecting further data for the purpose of filling out categories (Charmaz, 2006). Grounded theory allowed for adapting the interview guide as interviews were conducted and more insight on the developing theory was gained (Creswell & Poth, 2018). For example, after interviewing several participants, the first author attuned to the emerging category of nonbinary representation in participants’ lives and how being connected to nonbinary community aided in participants embodying affirmative experiences of gender and navigating gender norms in authentic ways. The first author employed theoretical sampling by asking more questions about participants’ experiences with nonbinary community and the meaning that nonbinary friendship held for participants to further saturate this emerging category of “creating affirmation and authenticity” through experiencing community (Charmaz, 2006).Throughout the interviews, the first author was attuned to working toward theoretical saturation—gathering data with the intention of creating robust, distinct categories to conceptualize emerging theoretical explanations of the data (Charmaz, 2006). After conducting 21 interviews, the first author determined that theoretical saturation was reached based on the consistency of the emerging concepts and categories that were formed through data collection and theoretical sampling. In all, the interview guide was adapted by adding two additional questions, one that was focused on how nonbinary community impacted the ways participants internally navigated binary gender norms and another focused on how participants felt internally when they embodied their gender identity in affirming ways.

Initial, open coding

A team of six coders, including the first author, analyzed the data to answer the research questions. The coding team was comprised of individuals who held various racial and ethnic identities, gender identities, and sexual orientations, and there was representation from both marginalized and privileged positionalities across these identities. Throughout the analysis process, the coding team attended to queer theory ideas of resisting and critiquing gender norms as well as the influence of colonization, racism, and gender binary norms through memo writing and discussion (Bederman, 1995; Butler, 1990; Carter, 2007; Somerville, 2000; Tilsen, 2013; Warner, 1999). Each coder individually coded the first two transcripts by reading the entire transcripts and conducting line-by-line coding to become immersed in the data, tune into participant language and meaning, and develop an initial coding scheme (Charmaz, 2006). After each coder completed coding the first two transcripts, we met as a coding team for peer-debriefing to discuss our experience with the data and the coding process, codes that were salient and consistent across each coder, and how our identities informed how we were making sense of the data. We discussed until we reached consensus on a coding scheme to guide focused coding with the remaining transcripts (Charmaz, 2006).

Focused coding

Each coding team member coded six transcripts individually using the agreed upon coding scheme. To bolster credibility of the analysis, the first author assigned transcripts to each coding team member so that each transcript would be coded by at least two different coders with both insider and outsider experiences in relation to the participants’ identities to ensure diverse perspectives on the data. Through bringing these insider-outsider statuses to the analysis process, the coding team utilized constant comparisons of transcripts to ensure the codes fit across transcripts and that we were understanding the emerging theory across participants (Charmaz, 2006; Dwyer & Buckle, 2009). Throughout this coding process, each coder engaged in memo writing on how they were making sense of the data as a whole to contribute to theoretical coding—finding connections between categories of data that have emerged from the focused coding process (Charmaz, 2006).

Theoretical coding

Once all the transcripts were coded, the coding team met to discuss if the codes accurately represented participants’ data and reached consensus that the identified coding scheme represented the data well. The coding team then discussed ideas that were captured through memo-writing to identify categories through theoretical coding—grouping of ideas that have shared meanings and finding connections between categories (Charmaz, 2006). The coding team utilized theoretical coding to identify how contextual factors informed, and were connected to, the processes nonbinary people used to navigate binary gender norms internally.

Trustworthiness and credibility

To increase trustworthiness of the data analysis process, the coding team engaged in memo writing, self-reflexivity, and peer debriefing to discuss how their social identities and biases were informing how we were analyzing the data (e.g. Bermúdez et al., 2016). This included working to be aware of our insider-outsider stances and “the space between” these positions as we all had some experiences that made us insiders as well as some that made us outsiders in relation to the participants in this study (e.g. racial identity, ethnic identity, gender identity; Dwyer & Buckle, 2009). By acknowledging our insider-outsider statuses, we sought to be honest and transparent about our biases and how our personal experiences—both similar to and different from those of participants—impacted how we analyzed the data (Dwyer & Buckle, 2009). We also utilized member checking by inviting all of the participants to review and provide feedback on the final draft of the manuscript before submission. All participant feedback was incorporated into the manuscript. Lastly, an outside peer reviewer was invited to review the identified categories and to ask questions about how the coding team arrived at our findings.

Results

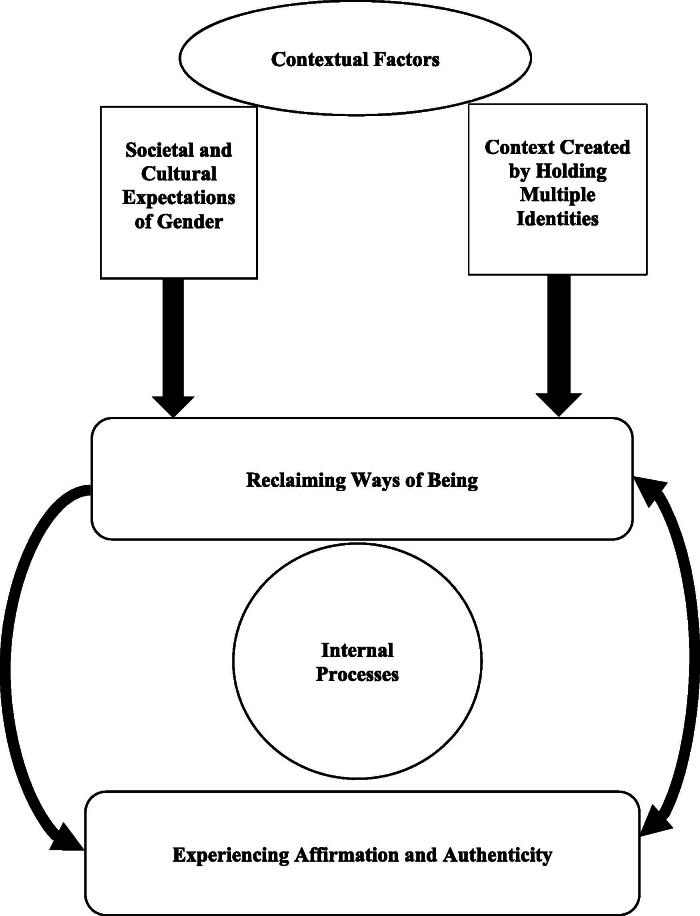

Through analyzing participants’ experiences using constructivist grounded theory methods, we identified a theoretical explanation of the processes nonbinary people use to internally navigate binary gender norms in their day-to-day experiences that was deeply informed by two categories that reflected contextual factors: a) societal and cultural expectations of gender; and b) the contextual impacts of holding multiple marginalized identities. Being mindful of these contextual factors, we also identified that nonbinary people use internal processes characterized by a) reclaiming ways of being that connected them to their authentic experience of gender and b) experiencing affirmation and authenticity, through active steps (i.e. intentional actions, conscious thought processes) that were affirming of their gender and selfhood. As participants experienced internal moments of noticing binary gender norms that did not align with their self-understanding of gender, they enacted internal reclaiming processes to embody nonbinary identity in self-affirming ways. These internal processes could not be separated from the contexts in which they were formed and actively encountered in participants’ lives (See Figure 1). It is important to acknowledge the limitation of grouping BIPOC experiences together as this limits the ability to focus on specifity of experiences tied to different racial identities. Results of this study should be interpreted by being mindful of the diversity of experiences among BIPOC participants as BIPOC communities are not homogenous, and their lived experiences are shaped by differential occurances of racism, colorism, and cultural histories and norms.

Figure 1.

Process model of nonbinary people internally navigating gender norms.

Contextual factors

Societal and cultural expectations of gender

Participants daily experienced a context of societal and cultural expectations of gender, which was demonstrated by participants being aware of how cisgender people perceived them. Participants described how they internally noticed how they were often perceived by cisgender people in ways that centered binary gender assumptions. This context impacted participants’ experiences of safety and comfort, as well as experiences of feeling authentic and being authentically seen by others. For example, Emerson commented on internally noticing the interplay between being perceived by others versus what gender presentation feels authentic to them:

Especially as I was starting to appear in public in dresses and heels and makeup, I would go through like, "Oh my gosh, people are going to stare at me, they’re going to confront me, I’m feeling unsafe in this moment, but I also feel like I want to do this."

Participants spoke about a range of experiences in which they were gendered as binary men or women based on perceptions of their gender presentation, such as having short hair, or perceived as transgressing gender dress code norms, which highlights the binary gender context that participants had to regularly navigate. The majority of BIPOC participants directly commented on how these societal and cultural expectations of gender exist at the intersection of race, ethnicity, gender, and culture because of European colonization, the societal enforcement of the gender binary, and racist gender norms. For example, Daya spoke to how the history of colonization impacts visibility and language for nonbinary BIPOC and creates a context that centers White gender norms:

But usually, queerness and trans is reserved for White people and the language surrounding it is English and other European, Eurocentric descriptions. And so those navigating it, as someone who’s grown up in the United States, but has a different cultural background is really uniquely difficult. Because technically, religiously and culturally within my culture, there’s a lot of gender fluidity, but because of colonization and Eurocentric values placed on Asian families and other countries’ families, there’s like this forced binary and it gets me angry because my parents have this idea of cisnormativity and heteronormativity, but it’s from colonization. It’s [cisnormativity and heteronormativity] not particularly from our culture, but we related it to our culture.

These societal and cultural expectations of gender informed by colonization, the gender binary, and Whiteness significantly impacted participants’ feelings of safety, experiences of feeling seen congruently, and the internal processes they used to embody their gender identities that cannot be separated from the context in which participants lived.

Context created by holding multiple identities

Consistent with intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, 1991), participants described throughout each interview how their multiple identities situated within systems of marginalization and privilege informed their experiences of internally navigating binary gender norms. Although the quotes in this category speak to participants’ personal experiences of holding multiple identities, this category developed as a contextual factor rather than internal processes of navigating gender norms illustrating how holding diverse identities creates a context in which participants are navigating binary gender norms in specific, nuanced ways in relation to the multiple identities they embody. Most of the BIPOC in this study described how the intersection of their race and gender impacts their level of safety when presenting in gender non-conforming ways and how sometimes their race is perceived first and erases the visibility of their gender, which informed their internal process of navigating binary gender norms. YR shared:

My being a second-generation Mexican immigrant and the ways that I have been racialized, just out in public and on social media sometimes, where I have been fetishized and exotified. That very much ties into the way that I’m being gendered by people. I think because of that, there’s always a level of resistance [to binary gender norms] there, with wearing what it is that I want, and even the ways that I may act.

Daya described their experience of erasure at the intersections of gender, race, culture, religion, and being a child of immigrants:

I know I say this to my partner a lot, but we always talk about how you could tell when there’s a White queer person walking around, but you cannot tell, or other people like the general public cannot tell when there’s a Person of Color that’s queer, genderqueer. And so, this idea of existing it’s gone. It’s erased, the moment I stepped out of the door, it’s erased. No matter what I do, it’s erased. So, it’s the idea of not being seen, like being a Person of Color and being queer and nonbinary, but also, it’s been enforced, through either the United States regulation of it, through my parent’s cultural and religious background, my parents are extremely religious. And although it’s coded as an Eastern religion, it still was colonized. And there’s a huge aspect of they’re all you have, like this immigrant narrative of like the family that you come here with to the United States is all you have. So, it’s like this immigrant narrative that you have to be conforming. If not, you will not have family…. I can’t talk about a separate one [identity] on its own, they’re very much just like together, but it just results in all this erasure and like you don’t matter, I think.

Some White participants acknowledged the privilege their White racial identity affords them, as well as how their Whiteness and nonbinary gender identity create mixed experiences of noticing some physical safety while also having to navigate marginalizing gender experiences due to not conforming to binary gender norms. For example, Emerson described:

I also think, of course, being White in this country allows me to walk into many, many spaces and feel comfortable. And then I think, I mean I would assume, just my interactions with other folks, the privilege that I carry as a White person means that they’re probably not going to confront me in the same that they would a Person of Color. I’d also say that within the queer community, the places that I’ve had the least acceptance are with White cis[gender] gay men. And some acceptance on like surface level, like, "Oh yeah, that’s cool." But even, my partner and I are polyamorous, and even changing my profile on Grindr, the people that would talk to me before who now won’t speak to me because I use they/them pronouns and I’m genderqueer.

Education

Participants discussed how having access to formal education provided space to explore their gender in unique and important ways, as well as providing them with a greater array of language to reflect their experiences. Willow shared:

So, I think it’s difficult navigating those norms, but I think my… also my academic experience with theory about… like gender theory and queer theory and stuff has been really helpful in consoling me or formulating my stances on certain things and how I practice certain things.

Social class

Multiple participants talked about how their social class impacted their ability to buy gender affirming clothing and access medical transition, which informed how they thought about and experienced navigating binary gender norms. For example, Jayce said:

So, I also want top surgery and it costs so much. I don’t have a therapist and I prefer not to have to go to a therapist to validate who I am and say that because I identify this way, I need to get top surgery. I know I need top surgery. So, I don’t have a therapist and top surgery cost so much through an informed consent [model] that I just get down sometimes.

Overall, participants’ multiple identities exist in a context that informs their experiences with noticing how they are gendered by others, how they understand themselves, and experiences of both visibility and erasure.

Processes of navigating binary gender norms internally

The ways that participants navigated binary gender norms internally were directly influenced by and in response to the external contexts described above (i.e. societal and cultural expectations of gender and context created by holding multiple identities). The internal processes participants described when explaining how they navigate binary gender norms were primarily characterized by intentional choices they made to connect and stay connected to their authentic selves as nonbinary people, whether that was in response to external affirmation or non-affirmation of their gender identity. Participants navigated binary gender norms internally by (a) reclaiming ways of being and (b) experiencing affirmation and authenticity. The majority of participants described reclaiming self-defined, affirmative ways of being as an initial process that then enabled them to create an internal experience of affirmation and authenticity in being nonbinary. Then, participants’ internal processes of reclaiming ways of being and experiencing affirmation and authenticity mutually informed one another in participants’ day-to-day lives (See Figure 1).

Reclaiming ways of being

Participants internally navigated binary gender norms by reclaiming ways of being that were congruent with their gender through (a) reclaiming self-knowledge, (b) reclaiming ancestral knowledge, and (c) critiquing gender norms.

Reclaiming self-knowledge

Several participants reflected on knowing how they wanted to embody gender when they were younger even if they were not given the space or language to claim these ways of being. Participants recalled memories of dressing and acting in ways that were congruent to them but that adults around them deemed nonconforming or abnormal, and that part of navigating gender norms in their current life involves connecting back to this historical knowledge of themselves to reclaim self-affirmed ways of being. For example, Michelle/Michael explained connecting to knowing about their own personal history and insight of themself as bigender and seeing examples of that in how as a kid they:

Would dress up as Prince Eric from The Little Mermaid, almost just as much if not more than Ariel. I would want to go in costume to Walmart and things. But I try to remember those moments of, yeah, it’s always been there. It’s always been part of me, and trying to remember a time where… I don’t know, it didn’t feel like I had left the nest yet, and all these societal expectations kind of started hitting me.

Reclaiming self-knowledge also was described by participants as noticing what felt affirming and congruent. For example, Ouran described an internal process of noticing which pronouns felt non-affirming of their gender:

And that was when I started to realize that also she/her pronouns were starting to bug me in 2017. I started to [cringe] a little bit every time I heard it when I was hearing it from teachers and students and then my friends. And I’d be like, why does this feel weird all of a sudden? Why is it starting to bother me? Yeah. It was just a sudden moment of, “oh, this isn’t right”.

Reclaiming ancestral knowledge

Many of the BIPOC in this study described the powerful affirmative influence of learning about gender knowledge that has existed for centuries in their familial culture but that was erased through colonization, as well as how White supremacy has shaped gender norms. This was sometimes described broadly by talking about the gender binary at large and how clothing is policed through the gender binary, as well as specifically by reflecting on personal cultures and histories that celebrate gender expansiveness and did not have the language of the gender binary until they were colonized. Amihan illustrated this idea:

But now I understand that the gendering of clothing is really part of a colonial project of the gender binary. So, I really follow folks like Alok Vaid-Menon in saying that clothes have no gender, it’s fine… And so, there’s always this really intense lens of gender that we’re taught to read everything through. So, unlearning that for me has been really important to take things, to just look at everything through different sociological lenses, to look not just at gender, but class, and race, and geography, and all of the other specific factors that make up the intersections of people’s identities. And to read with a broader context, as opposed to just through the very conditioned and colonial projects of the gender binary.

Another participant, Jomar, talked about learning about the history of the Philippines and connecting to personal ancestral knowledge:

I think also just rooted in learning that history about pre-colonial Philippines without romanticizing it for sure but just the acknowledgement that this [expansive, nonbinary understanding of gender] has existed for centuries, centuries before all these different countries came in to colonize the Philippines and it’s in my blood. It’s something that my ancestors have experienced and that’s been truly nice.

Willow expressed a related notion of feeling affirmed in their gender identity by consciously rejecting racist gendered narratives embedded in White supremacy and reclaiming affirmative ways of embodying their gender identity:

A lot of gender stereotypes concerning Black people hold us in a nonbinary light, I guess with… like Black women are, they’re women, but also very much masculinized and seen as holding two gender spaces, whereas Black men are seen as hyper masculine, but also sometimes [society saying] they need to be brought down to a level that is seen as emasculating to men or whatever. So, these are all negative things, but I guess trying to reclaim those narratives back from White supremacy is one way that I can conceptualize my gender identity.

Critiquing gender norms

Another mechanism participants used to internally navigate binary gender norms was to critique the norms and then embody an affirmative experience of their gender. One participant, Willow, talked about encountering norms for people who are assigned female at birth (AFAB) to wear make-up, as well as norms for nonbinary people to present androgynously, and how as a nonbinary person, they wear make-up in a way that affirms them but that is not based on societal binary gender norms:

So, I have been into makeup a little bit for a couple of years now, but I’ve really gotten into it over the summer and this year. And sometimes I wonder if… I used to get a little worried if I was… if people would be like, "Oh, that person is faking [being nonbinary]," or whatever, "since they like to do makeup and stuff." I have my own boundaries with makeup that have helped me feel more comfortable fitting that norm as an AFAB person. I love doing eyeshadow and I always like doing bright… I’m not trying to do a natural look or whatever, something… I like exploring different ways to do it and stuff, and I also don’t use foundation, which is my F*** you or whatever.

Other participants also talked about gendered norms for ways society may expect them to act or look. Specifically, participants described an internal process of noticing gender norms being prescribed to them, which made them uncomfortable, critiquing the norm, and affirming themselves through this process. For example, Rumra shared:

I do some community organizing and someone was helping me with a bunch of stuff and they were like, "On the day, don’t worry about it. I’m available to help carry stuff." I was like, "I’m gay. I carry stuff." It’s a kind of like more being like, "No…" Just the assumptions kind of make me uncomfortable. I do, and enjoy, a lot of activities that are typically feminine coded. I do a lot of cooking and baking and when my roommates are here, which they’re not currently, I cook for everyone. But then it’s like when the things I like doing or when the assumptions are made about what I can do are connected to the gender people perceive me as I’m like, "I’m immensely uncomfortable right now. Can we not?"

Through reclaiming self-knowledge of who participants knew themselves to be as nonbinary people, reclaiming ancestral knowledge that affirmed their experience of gender outside of enforced White, Euro-centric norms, and critiquing binary gender norms to embody affirmative experiences, participants internally navigated binary gender norms in ways that positively impacted their sense of self and well-being.

Experiencing affirmation and authenticity

The second way participants described processes of internally navigating binary gender norms encapsulated ways of consciously thinking through how they felt affirmed in their gender identity by noticing and embodying gender affirming experiences. Participants described these processes as (a) self-defining affirmative nonbinary ways of being, (b) noticing affirmation in chosen community, and (c) embodying freedom and authenticity.

Self-Defining affirmative nonbinary ways of being

The majority of participants talked about how they have paid attention to ways of presenting that felt most affirmative and authentic. Although many participants discussed dressing and presenting in ways that could be considered gender nonconforming based on gender binary, Euro-colonized standards, not all of the participants reported presenting in nonconforming ways. However, all participants did talk about feeling authentically nonbinary in the ways they chose to embody their gender regardless of how they were externally perceived. Jinx described how clothing expresses the balance they feel in their gender and being nonbinary:

Because when I put on makeup and when I put on feminine clothing I feel more—I wouldn’t say dominatrix—but I feel more confident and finessed and fabulous. And then when I’m wearing masculine clothing, I feel more humble. It’s a nice balance of me. I think it’s just because I’m breaking the binary by existing that gives me the confidence.

Jayce described a similar experience of noticing how their clothing choices felt affirming and authentic:

I feel my most self when I’m wearing a feminine top and masculine bottoms. I just feel like, "Man, I feel like my gender identity right now." Or vice versa, I might be wearing a skirt with a male’s button up or something and I just feel so beautiful.

Many participants, including Emerson, further elaborated on how an affirmative and authentic self-presentation gave them more confidence and created more of a sense of feeling connected to themselves and their gender identity:

I really enjoy having a beard in the fall and the winter. It’s warmer, it’s a lot more comfortable, but it’s also something that is assumed to be a masculine trait. And so even accepting this thing, and saying, "Yeah, but actually, it’s queer to me." I’m actually continuing to queer gender by having it. Like, have that… Throw on some lipstick, wear some fabulous clothes, and I’m just queering it all around. In those moments that I’m taking on one of those gender norms that is assumed as masculine, I’m trying to queer it in some way… I love it. And it really allows me to affirm myself, and… I mean, it also puts me out there more, which also, if I have pushback then I just want to show up even queerer and then I just affirm myself more. It’s like a happy little affirmation circle.

Noticing affirmation in chosen community

Most participants talked about experiencing affirmation when they did not have to navigate societal, binary gender norms, and that cultivating spaces in their homes and with chosen friends was important to feeling affirmed and authentic. These experiences were especially highlighted when participants talked about working from home because of the COVID-19 pandemic and how they noticed a sense of peace and relief from not having to worry about navigating societal expectations. Daya shared:

And the validation of my chosen family, not just validation, just not acknowledging it [gender expectations] in the best way, just existing with chosen family in a way that I feel at home…I kind of get to exist. I could be in the most cis[gender] looking outfit, but I would not be mis-gendered or perceived a certain way. I’m just seen as like another human body and not in a non-personal way, but more just I’m just another human and there’s not expectations to who I’m supposed to be and what I’m supposed to do.

Every participant in this study spoke to the feeling of affirmation and authenticity they experienced from being in community with other nonbinary people, especially with nonbinary people who shared similar other marginalized identities, as well as seeing themselves represented in various spaces. These experiences were ones in which participants internally noticed the affirmation that comes when in supportive nonbinary communities, and the provided freedom to embrace ways of doing gender that are affirming. Jin explained:

I always think about queer and trans people of color. That’s definitely the community I feel most at home with and very affirmed and… It’s nicer, because we just kind of can cease to view gender in this gross, Western binary way that’s very restrictive and honestly quite violent for some people in their experiences of gender. We can just be very free and fluid with it. That’s my ideal… Just I would like to exist there and not have to deal with anything else.

Embodying freedom and authenticity

Participants described how they feel when they embrace and embody their gender in ways that are most affirming, and that they internally held on to and embodied these experiences to navigate binary gender norms. In particular, participants described internal feelings of confidence, freedom, possibility, and creativity. Daya said, “I feel this validation that I’ve never… I could never feel from somebody else. It feels like this endless possibility to me, like this idea that it’s like a step closer to who I am. It’s like validating internally.” Other participants spoke to feelings of authenticity when they embody gender. Michelle/Michael expressed:

I think when I finally do it and I’m owning it and not worrying about other things going on, which is hard for me to do, I think… It’s exciting. It feels somehow like real comfortable for me, not the manufactured me that I feel like I was playing out in high school, where I was just hyper-performing being a woman. I don’t know, was trying to fit in as best as I could figure out in addition to all my other difficulties with doing that. It feels like I’m embracing how… I don’t know, how I’m interesting or compelling or… Yeah. Experience as a human being on several levels. Yeah. Something about it just feels more real.

Another participant, YR, illustrated what the freedom and joy of being nonbinary feels like to them:

I think some of the joy that I experience, how people have also created a community and identity within themselves. So, I’m thinking about neuro-queer, and what does that mean for neuro divergent and autistic folks who are queer and see their queerness and disability as enmeshed in this way of, you can’t separate one from the other. Seeing how other people are experiencing joy, and also creativity, it’s like I don’t have to fit myself into one box, or certain boxes. I could say, "Fuck you," to all that, and be who I am, and be all these things, and be one, or nothing, and it’s just who I am. I don’t know how to explain that level of freedom and level of validation that I felt with all of that. It’s like I’m finally coming into myself in a way that I was unable to when I was younger. So, I don’t know. I’m getting teary eyed just thinking about it.

Participants experienced affirmation and authenticity to navigate binary gender norms through important internal processes in self-defining affirmative nonbinary ways of being, noticing affirmation in chosen community, and embodying freedom and authenticity.

Discussion

This constructivist grounded theory study focused on identifying and understanding the contextually-dependent internal processes nonbinary people use to navigate binary gender norms. Analysis of the data yielded findings that expand the scholarly literature on the lived experiences of nonbinary people, especially nonbinary BIPOC, and the ways in which nonbinary people internally respond to, cope with, and navigate societally enforced binary gender norms (Beischel et al., 2022; Brennan et al., 2017; Truszczynski et al., 2022). It is evident from the participants in this study that the task of having to navigate binary gender norms in the U.S. exists because of societal and cultural enforcement of the gender binary. The lived experiences of the participants demonstrate that the history of colonizing practices European settlers used to enforce binary gender ideals on cultures around the world continue to impact the daily lives of nonbinary people (Iantaffi, 2020). Namely, nonbinary people in this study described being perceived in ways that reinforced binary expectations of gender expression. In line with scholars and historians who have detailed how the dominance of White people and White supremacy norms relied on policing gender conformity (Bederman, 1995; Carter, 2007; Iantaffi, 2020; Somerville, 2000), results from this study highlight the experiential impacts of colonialist, racist, and cissexist structures that inform how nonbinary people internally navigate gender norms.

Education and social class were salient contexts that informed these processes of internally navigating gender norms. For example, participants in this study reflected on different levels of access to affirmative ways of presenting their gender tied to economic resources. Many, but not all, participants discussed how higher education gave them access to new language and knowledge that helped them identify and connect to experiences of affirmation in their nonbinary gender identities. Transgender and nonbinary scholars and activists advocate for increasing access to knowledge about the gender binary and history of transgender and nonbinary people as an important way to promote transgender and nonbinary inclusivity in society (e.g. Iantaffi, 2020; Vaid-Menon, 2020). Results from this study support expanding awareness and knowledge of transgender and nonbinary identities and experiences to bolster the mental health and well-being of nonbinary people and access to embodying affirmative understandings of nonbinary genders.

The societal context that privileges binary gender conformity understandably heightened the importance of participants experiencing community contexts with similarly identified peers. Expanding on existing literature that demonstrates the benefits of being connected to nonbinary communities and friends (e.g. Bradford & Syed, 2019; Fiani & Han, 2019), this study found that nonbinary people experience internal moments of solace in relationships with other nonbinary people as these community spaces run counter to the pervasiveness of the gender binary and all of its limitations and harmfulness. This is particularly true for nonbinary BIPOC and nonbinary people from Eastern cultures as being in community with queer and nonbinary people with similar racial and cultural identities provides moments of freedom from experiencing racism, cissexism, and Eurocentrism (i.e. privileging Western ways of being) that inform the ways nonbinary people internally create self-affirmation and authentic embodiment.

Understanding these contexts elucidates how participants navigated binary gender norms internally by self-defining affirmative nonbinary ways of being, noticing affirmation in a chosen community that allowed them to experience existing authentically outside of binary gender norms, and internally connecting to an embodied, authentic sense of gender within themselves and in community with other nonbinary people. These results expand on existing literature by underscoring the active processes nonbinary people use in their day-to-day lives to navigate gender norms in ways that positively impact their mental health and well-being (Beischel et al., 2022; Brennan et al., 2017; Puckett et al., 2019; Tebbe & Moradi, 2016; Valentine & Shipherd, 2018). Participants in this study experienced joy and freedom in embodying their nonbinary genders, which furthers the literature on experiences of gender euphoria among nonbinary people (Beischel et al., 2022). The few studies on how nonbinary people respond to or cope with marginalization, discrimination, and microagressions based on the gender binary have mostly relied on the gender minority stress framework or the transactional theory of stress and coping (e.g. Lazarus, 1993; Puckett et al., 2020; Testa et al., 2015; Truszczynski et al., 2022). Results from this study indicate that frameworks for promoting mental health and well-being that may better fit the experiences of nonbinary people need to include somatic-based embodiment and regulation practices (Dana, 2021; Gutiérrez, 2022; Iantaffi, 2020). Specifically, participants in this study spoke to ways of navigating binary gender norms that move beyond psychological coping and pride (Puckett et al., 2020; Testa et al., 2015) and aligned with somatic-based embodiment and regulation practices (e.g. mindfully noticing self-affirmation and embodying feelings of authenticity), which are essential to healing from societal-based marginalization and trauma (Dana, 2021; Gutiérrez, 2022; Iantaffi, 2020).

Emerging theory: Internal processes focused on experiences of affirmation

This constructivist grounded theory study identified an emerging theory and six theoretical propositions about how nonbinary people internally navigate binary gender norms, visually depicted in Figure 1. First, nonbinary people connect to experiences of affirmation of their gender identities through reclaiming gender-affirmed ways of being, and experiencing affirmation and authenticity within their gender identity. Second, when nonbinary people reclaim ways of being that are congruent with their nonbinary gender, this can open more internal, emotional, cognitive and embodied space to experience affirmation and authenticity for themselves. The one-way arrow from “reclaiming ways of being” to “experiencing affirmation and authenticity” in the process model (See Figure 1) represents that for some nonbinary people, reclaiming affirming ways of being occurred first and then informed their experiences of affirmation and authenticity. Third, the internal processes of reclaiming gender-affirming ways of being and experiencing affirmation and authenticity can be mutually influential once there have been initial experiences of reclaiming ways of being (demonstrated by the double arrow). For example, when participants experienced affirmation and authenticity through self-presentation or noticing affirmation in chosen communities, they also re-affirmed the importance of reclaiming ways of being (e.g. connecting to ancestral knowledge), which contributed to further experiencing affirmation in their gender. Fourth, internal processes used to navigate binary gender norms cannot be understood outside the context of societally and culturally enforced expectations of gender that are rooted in the Western gender binary, Euro-colonized ideals for gender and gender expression, and the upholding of White supremacy. Fifth, navigating binary gender norms is situated in one’s experience of all of the different identities they hold. Finally, internal processes of navigating binary gender norms encompasses nonbinary peoples’ knowledge of and connection to their affirmative experience of gender regardless of how they are presenting or being perceived. Thus, results from this study demonstrate an operationalization of the intellectual underpinnings of queer theory as participants used practical, actionable internal strategies to deconstruct and resist the gender binary to embody self-affirmation of their nonbinary gender identities (Butler, 1990; Doty, 1993; Tilsen, 2013).

Implications

This study has implications for ways that nonbinary people can be better supported in society to reduce health disparities and bolster well-being. Policy makers and programs focused on promoting nonbinary gender inclusivity should be conscious to not further enforce marginalizing binary gender norms rooted in cissexism, racism, and Euro-centrism. Understanding the role that European colonization has played in the constructing and enforcement of the gender binary is essential to intervening in the negative impacts of marginalization on nonbinary people and cultivating a more inclusive society (Iantaffi, 2020; Vaid-Menon, 2020). Nonbinary voices and experiences should be centered in these efforts.

Based on the results of this study, mental health professionals should work with nonbinary clients to connect to affirmative experiences of their gender identity and explore ways that embodying affirmation can assist clients in navigating marginalizing experiences and contexts. Especially relevant to the clinical implications of this study that included majority BIPOC participants is the need for mental health professionals to practice from culturally humble, intersectional frameworks to attune to the experiences of nonbinary BIPOC. Mental health professionals should be especially mindful of differential racialized experiences among BIPOC given the diverse breadth of experiences within these communities and the nuanced ways that racism, colorism, and cultural prejudices get enacted (Chang & Singh, 2016; Golden & Oransky, 2019). This study offers insight into assessment and intervention areas that may impact client well-being, including clients’ lived affirming experience of feeling connected to their gender, the deconstruction of binary gender norms by situating experiences of marginalization in the context of cissexism and racism, and the cultivation of practices to notice when clients experience joy and freedom in their gender identity (Chang et al., 2018; Iantaffi, 2020; McGeorge et al., 2021).

Because of the pervasiveness of gender norms tied to cisnormativity and transnormativity evident in this study, mental health professionals may need to normalize multiple narratives of being nonbinary to reinforce the notion that there is no one way to “correctly” be nonbinary. Mental health professionals could further explore with nonbinary clients their preferred meanings of gender expression/self-presenting, how to make their personal living spaces free from the norms perpetuated by society, and how to develop community with people who share similar identities, especially being mindful of the importance of representation for nonbinary BIPOC (Chang & Singh, 2016).

Limitations and Future research

Limitations in this study include that participants were self-selected through social media recruitment and interviews were conducted over Zoom, which limited the sample to people who engage in social media and had access to the internet through a computer or smartphone. Moreover, the majority of the sample had completed higher education, limiting the ability of this study to identify what processes of navigating gender norms look like across various educational backgrounds and socioeconomic statuses. Future research should focus on how diverse educational experiences and socioeconomic statuses inform nonbinary people’s experiences of navigating gender norms. Interviews were also conducted at a single time point; longitudinal research examining processes of navigating gender norms over time would further theory development on the processes nonbinary people use to navigate gender norms at different developmental stages.

Conclusion

Binary gender norms are pervasive in U.S. society and culture, and nonetheless, nonbinary people find ways to experience and emobody affirmation in their gender identity through internal processes. Understanding the contexts of the gender binary, racism, and cissexism that impact nonbinary people on a daily basis is crucial for mental health professionals, researchers, policy makers, and creators of gender inclusive education and support programs to support and affirm nonbinary people. Results from this study show that nonbinary people using internal strategies to stay connected to their affirmed sense of gender through noticing and embodying gender affirming moments and resisting expectations of binary gender norms yields experiences of joy and freedom. By centering the experiences of nonbinary people in this study, especially nonbinary BIPOC, we hope that these results encourage bolstered support of nonbinary people in all facets of life and move us toward a more nonbinary inclusive world.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend deep gratitude and appreciation to those who participated in this study.

Note

We are using BIPOC to intentionally acknowledge the history of enslavement and genocide of Black and Indigenous peoples in the U.S. and how this shapes differential racialization experiences among BIPOC, and the on-going racial disparities experienced by Black and Indigenous people in the U.S.

Funding Statement

Funding for this project came from the Kansas State University- Robert H. Poresky Assistantship in Family Studies and Human Services.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Allen, S. H., & Mendez, S. N. (2018). Hegemonic heteronormativity: Toward a new era of queer family theory. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 70–86. 10.1111/jftr.12241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association . (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist, 70(9), 832–864. 10.1037/a0039906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, G. R., Hammond, R., Travers, R., Kaay, M., Hohenadel, K. M., & Boyce, M. (2009). “I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives”: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care : JANAC, 20(5), 348–361. 10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederman, G. (1995). Manliness and civilization: A cultural history of gender and race in the United States, 1880-1917. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beischel, W. J., Gauvin, S. E. M., & van Anders, S. M. (2022). “A little shiny gender breakthrough”: Community understandings of gender euphoria. International Journal of Transgender Health, 23(3), 274–294. 10.1080/26895269.2021.1915223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez, J. M., Muruthi, B. A., & Jordan, L. S. (2016). Decolonizing research methods for family science: Creating space at the center. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8(2), 192–206. 10.1111/jftr.12139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, N. J., & Catalpa, J. M. (2019). Social and psychological heterogeneity among binary transgender, non-binary transgender and cisgender individuals. Psychology & Sexuality, 10(1), 69–82. 10.1080/19419899.2018.1552185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, N. J., Rider, G. N., Catalpa, J. M., Morrow, Q. J., Berg, D. R., Spencer, K. G., & McGuire, J. K. (2019). Creating gender: A thematic analysis of genderqueer narratives. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2-3), 155–168. 10.1080/15532739.2018.1474516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, N. J., & Syed, M. (2019). Transnormativity and transgender identity development: A master narrative approach. Sex Roles, 81(5-6), 306–325. 10.1007/s11199-018-0992-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, S. L., Irwin, J., Drincic, A., Amoura, N. J., Randall, A., & Smith-Sallans, M. (2017). Relationship among gender-related stress, resilience factors, and mental health in a Midwestern U.S. transgender and gender-nonconforming population. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(4), 433–445. 10.1080/15532739.2017.1365034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budge, S. L., Rossman, H. K., & Howard, K. A. S. (2014). Coping and psychological distress among genderqueer individuals: The moderating effect of social support. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 8(1), 95–117. 10.1080/15538605.2014.853641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, J. B. (2007). The heart of whiteness: Normal sexuality and race in America, 1880-1940. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S. C., & Singh, A. A. (2016). Affirming psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people of color. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 140–147. 10.1037/sgd0000153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S. C., Singh, A. A., & Dickey, l m (2018). A clinician’s guide to gender-affirming care: Working with transgender and gender nonconforming clients. New Harbinger Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Conlin, S. E.,, Douglass, R. P.,, Larson-Konar, D. M.,, Gluck, M. S.,, Fiume, C., &, Heesacker, M. (2019). Exploring Nonbinary Gender Identities: A Qualitative Content Analysis. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 13(2), 114–133. 10.1080/15538605.2019.1597818 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1229039 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Croteau, T. A., & Morrison, T. G. (2022). Development of the nonbinary gender microaggressions (NBGM) scale. International Journal of Transgender Health, 1–19. 10.1080/26895269.2022.2039339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dana, D. (2021). Anchored: How to befriend your nervous system using polyvagal theory. Sounds True. [Google Scholar]

- Doty, A. (1993). Making things perfectly queer: Interpreting mass culture. University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, S. C., & Buckle, J. L. (2009). The space between: On being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 54–63. 10.1177/160940690900800105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiani, C. N., & Han, H. J. (2019). Navigating identity: Experiences of binary and non-binary transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) adults. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2-3), 181–194. 10.1080/15532739.2018.1426074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden, R. L., & Oransky, M. (2019). An intersectional approach to therapy with transgender adolescents and their families. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(7), 2011–2025. 10.1007/s10508-018-1354-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, N. Y. (2022). The pain we carry: Healing from complex PTSD for people of color. New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hammonds, E. (1997). Black (w)holes and the geometry of black female sexuality. In Weed E. & Schor N. (Eds.), Feminism meets queer theory (pp. 136–156). Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J., Grant, J., & Herman, J. L. (2012). A gender not listed here: Genderqueers, gender rebels, and otherwise in the national transgender discrimination survey. LGBTQ Public Policy Journal at the Harvard Kennedy School, 2(1), 13–24. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2zj46213 [Google Scholar]

- Iantaffi, A. (2020). Gender trauma: Healing social, cultural, and historical gendered trauma. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Imani, B. (2021). (). Read this to get smarter: About race, class, gender, disability & more. Ten Speed Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A. H. (2016). Transnormativity: A new concept and its validation through documentary film about transgender men. Sociological Inquiry, 86(4), 465–491. 10.1111/soin.12127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe, T. M.,, Reisner, S. L.,, Schrimshaw, E. W.,, Radix, A.,, Mallick, R.,, Harry-Hernandez, S.,, Dubin, S.,, Khan, A., &, Duncan, D. T. (2020). Navigating stigma in neighborhoods and public spaces among transgender and nonbinary adults in New York City. Stigma and Health, 5(4), 477–487. 10.1037/sah0000219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1993). Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55(3), 234–247. 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno, E., & Budge, S. L. (2017). Non-binary/genderqueer identities: A critical review of the literature. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9(3), 116–120. 10.1007/s11930-017-0111-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGeorge, C. R., Coburn, K. O., & Walsdorf, A. A. (2021). Deconstructing cissexism: The journey of becoming an affirmative family therapist for transgender and nonbinary clients. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 47(3), 785–802. 10.1111/jmft.12481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, J. K., Beek, T. F., Catalpa, J. M., & Steensma, T. D. (2019). The genderqueer identity (GQI) scale: Measurement and validation of four distinct subscales with trans and LGBQ clinical and community samples in two countries. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2-3), 289–304. 10.1080/15532739.2018.1460735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, J. E. (1999). Disidentifications: Queers of color and the performance of politics. University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Puckett, J. A., Aboussouan, A. B., Allura, L., Ralston, A. L., Mustanski, B., & Newcomb, M. E. (2023). Systems of cissexism and the daily production of stress for transgender and gender diverse people. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(1), 113–126. 10.1080/26895269.2021.1937437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett, J. A., Maroney, M. R., Wadsworth, L. P., Mustanski, B., & Newcomb, M. E. (2020). Coping with discrimination: The insidious effects of gender minority stigma on depression and anxiety in transgender individuals. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 176–194. 10.1002/jclp.22865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett, J. A., Matsuno, E., Dyar, C., Mustanski, B., & Newcomb, M. E. (2019). Mental health and resilience in transgender individuals: What type of support makes a difference? Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 33(8), 954–964. 10.1037/fam0000561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]