Abstract

Background

Past research has demonstrated that transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people often have negative experiences of healthcare. Exploratory research is needed to provide in-depth understanding of the healthcare experiences of TGD people. Primary care is a crucial element of healthcare, but past research has tended to overlook what contributes specifically to positive experiences of primary care for TGD adults.

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore positive experiences of TGD adults when engaging with primary care in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Methods

Semi-structured email interviews were conducted with 11 TGD adults aged 20- to 62-years-old, with a range of binary or non-binary genders living across Aotearoa New Zealand. The email interview method allowed nationwide recruitment and flexible interaction. All aspects of the study were led by a researcher who is part of the TGD community.

Results

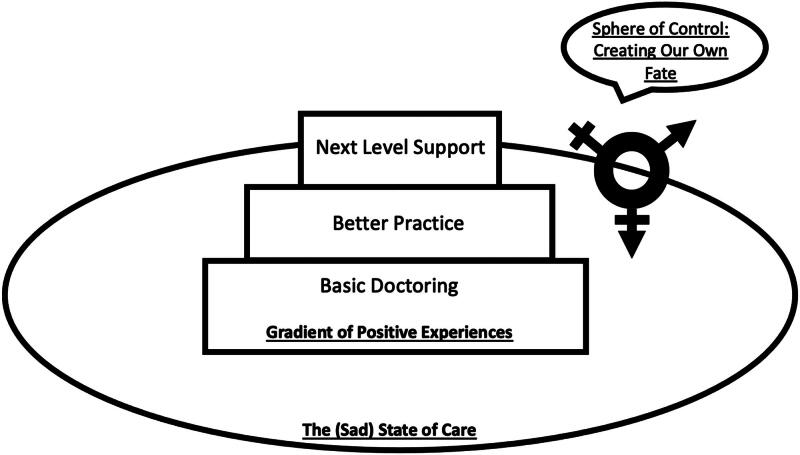

Three themes were formulated to explain TGD participants’ positive experiences with primary care. In order to contextualize positive experiences, participants described past negative experiences of healthcare and low expectations (Theme 1: The Sad State of Care). Participants also described exerting autonomy, for example by carefully selecting a general practitioner (GP) or choosing when to disclose transgender status to their GP (Theme 2: The Sphere of Control). Three levels were evident in positive experiences (Theme 3: The Gradient of Positive Experiences): basic professionalism, more desirable experiences of trans-specific competencies, and GPs as advocates for systemic change.

Discussion

TGD people experience positive interactions in primary care in a variety of ways, all of which are contextualized by the negative state of healthcare at present. TGD people create opportunity for autonomy while navigating healthcare, which requires a form of interacting that can be termed reactive self-determination. Training for health professionals could apply the gradient of positive experiences to scaffold appropriate primary care for TGD adults.

Keywords: Gender minorities, healthcare experiences, patient autonomy, professional standards, qualitative research, transgender health

Introduction

Existing health research with transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people shows an unacceptable picture of inequitable health outcomes (Nobili et al., 2018; Reisner et al., 2016). The literature consistently demonstrates that TGD adults whose gender experiences or presentations fall outside normative expectations experience discrimination, especially in healthcare, resulting in negative patient experiences (Klein & Golub, 2020; Safer et al., 2016; Stotzer et al., 2013). Transgender healthcare experience is an emerging area of study within which there has been very little research focused on exploring the positive healthcare experiences of TGD people. Past research has largely taken a deficit focus that misses the opportunity to understand positive experiences and inadvertently perpetuates avoidance of unacceptable treatment rather than ideal treatment as described by the community itself. Although some literature takes an empowering approach to TGD adults’ experiences with healthcare (Dewey, 2008; Gibson et al., 2016; Roller et al., 2015), overall there is a surprising lack of strengths-based focus in explorations of TGD people interacting with healthcare systems. By asking participants what they considered to be a positive experience, the data can aid in articulating what the ideal treatment should involve.

Positive experiences of healthcare vary within the TGD population along a spectrum (Kattari et al., 2016, 2019; Klein & Golub, 2020; Tan et al., 2022; Treharne et al., 2022b; Veale et al., 2019). Two past qualitative studies have intentionally explored positive healthcare experiences for TGD people. Ross et al. (2016) described how multilevel healthcare systems create barriers to accessing care for Canadian TGD people at the same time as opportunities for positive healthcare experiences. Based on the 10 interviews they conducted they also noted that patient-centered competencies are necessary to ensure positive experiences for TGD people. Tan et al. (2022) analyzed comments on healthcare from 153 participants as part of the larger Counting Ourselves nationwide survey in Aotearoa New Zealand. They described similar issues with multilevel healthcare systems shaping TGD people’s positive experiences of primary care in tandem with positive characteristics of healthcare professionals and enabling resources that facilitate access. The broader literature on transgender healthcare experiences describes multilevel mechanisms by which TGD people are disenfranchized from healthcare access (Bauer et al., 2009; Brotman et al., 2002; Cruz, 2014; Dewey, 2008; Klein & Golub, 2020; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017; Ross et al., 2016). The literature also demonstrates the many ways TGD participants would take action where they could, in an attempt to increase the likelihood of a desirable outcome (Bartholomaeus et al., 2021; Dewey, 2008; Dutton et al., 2008; Gibson et al., 2016; Pearce, 2018; Poteat et al., 2013; Roller et al., 2015; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017). Aside from Ross et al. (2016) and survey research addressing positive aspects of healthcare (Kattari et al., 2016, 2019; Klein & Golub, 2020; Treharne et al., 2022b; Veale et al., 2019), most existing literature on experiences of TGD healthcare has only incidentally included positive healthcare experiences through asking open-ended questions in qualitative research about healthcare interactions (Bartholomaeus et al., 2021; Gibson et al., 2016; Roller et al., 2015). Positive experiences are not described as an absolute in this past qualitative research, but instead are contextualized within largely inadequate systems. The literature illustrates this contextual nature of positive experiences by differentiating practitioners who were affirming but lacked knowledge, from practitioners who had knowledge but were not affirming, or from practitioners with both attributes (Bartholomaeus et al., 2021; Clark et al., 2018; Dewey, 2008; Treharne et al., 2022b). Small actions such as kindness and professionalism (Dewey, 2008; Tan et al., 2022), acknowledging experiential authority (Voronka, 2016), correctly gendering a patient (Gridley et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2022; Treharne et al., 2022b), and willingness to learn about TGD healthcare needs (Bartholomaeus et al., 2021; Treharne et al., 2022b) are examples of contributors to positive experiences within the literature.

The previous international studies of TGD people’s experiences of healthcare have been heterogeneous, including a range of methods, populations, and healthcare systems, but generally have found consistently poor health outcomes, negative experiences, and barriers to health for TGD people (Bauer et al., 2009; Cruz, 2014; Dewey, 2008; Gibson et al., 2016; Klein & Golub, 2020; Poteat et al., 2013; Ross et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2022; Treharne et al., 2022b). Other studies describe healthcare policy makers and providers as lacking foundational education about trans-specific healthcare needs (Bauer et al., 2009; Brotman et al., 2002; Davies et al., 2013; Gibson et al., 2016; Roller et al., 2015; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017; Rounds et al., 2013; Sanchez et al., 2009). While waiting times are often dictated by type and capacity of healthcare systems, TGD people describe waiting times as a significant barrier to accessing care (Bartholomaeus et al., 2021; Clark et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2013; Dutton et al., 2008; Gridley et al., 2016; Ross et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2022b). The anticipated or actual mistreatment in healthcare settings is also widely described as a barrier (Bauer et al., 2009; Brotman et al., 2002; Cruz, 2014; Dewey, 2008; Dutton et al., 2008; Gibson et al., 2016; Poteat et al., 2013; Roller et al., 2015; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017; Sanchez et al., 2009; Scheim et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2022; Treharne et al., 2022b). Although these healthcare failings are important to understand, this focus does not fully illustrate the resourcefulness and self-advocacy TGD people may apply and fails to provide examples of what TGD adults would find beneficial within healthcare. Therefore, there is a need for research that adds to the understanding of the experiences of TGD patients in primary care settings using an exploratory approach, as well as taking a strengths-based focus in asking about positive experiences.

The aims of this research were: (1) to explore what TGD adults in Aotearoa New Zealand considered to be positive interactions with primary care; and (2) to contribute to the improvement of primary healthcare by identifying good practice in primary care from TGD patient perspectives.

Methods

A qualitative study using semi-structured interviews was conducted asynchronously by email. The study was led by a trans researcher for their Master of Public Health qualification and supervised by cisgender academics with expertise in public health and health psychology both of whom reflected on how to support knowledge generated by and for trans and non-binary communities. The use of email interviews allowed TGD participants to respond in their own time about their experiences of care and provided opportunities for the lead researcher to reflect on initial answers and ask further questions as relevant in each case following methodological guidance (Braun & Clarke, 2013; Gibson, 2017). In addition, using email interviews allowed for inclusion of participants from across Aotearoa New Zealand, including more rural areas where online interviewing is not possible due to the lack of high speed internet. Aotearoa New Zealand currently has a regionally managed, publicly funded healthcare system, which is available to citizens, residents, and some work visa holders for little to no direct cost (Ministry of Health, 2011, 2017). All people in Aotearoa New Zealand have to engage with primary care to access public or private medical services, including specialist care. While there are significant variations by location, most medical transition services are also accessed through referrals by primary care physicians, known as general practitioners (GPs) in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Participants

A two-step process was used. First, an online eligibility and demographics questionnaire seeking TGD participants was circulated via social media, utilizing snowball sampling. Second, a purposeful selection of TGD respondents were invited to participate in the semi-structured email interviews in late 2019, based on aspects of diversity described below.

The inclusion criteria for this project were being aged 18-years-old or older, having seen a GP in Aotearoa New Zealand in the past two years, and considering oneself to be a part of the TGD community. The definition provided to all participants noted that we were seeking TGD participants of any binary gender (i.e. trans men or trans women), any non-binary gender (e.g. genderqueer people), or lack of gender (e.g. agender people), as well as non-Western concepts of gender, including Māori identities, such as whakawāhine (a culturally-specific term for trans women) or tangata ira tāne (a culturally-specific term for trans men). People with or without a history of, or desire for medical transitioning or gender affirmation surgeries were welcome to participate. The lead researcher and supervisors are all tauiwi (non-Māori) and we actively attempted to ensure the study was welcoming for Māori, Pasifika, and other non-European people following ethics guidance (Delany et al., 2015). We conducted Māori consultation on the terminology and protocols for the study following formal processes at the university where the study was based. We also received feedback via a community social media page for the study and from four local TGD community members who were consulted when preparing the study, two of whom are Māori.

Thirty TGD respondents from across Aotearoa New Zealand completed the eligibility and demographics questionnaire, and 24 were invited to be interviewed. As a way of attempting to avoid ethnic homogeneity, TGD people who are Māori (the indigenous peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand) were prioritized during selection for interviews, as were people with other non-European and migrant identities. Of the 24 who were contacted about being interviewed, 11 invitations received no response, and two participants confirmed interest but did not respond to the initial interview question. Therefore, 11 email interviews were conducted. Prioritized participant recruitment followed the purposeful sampling, interviewing as many as possible within the data collection timeframe.

The 11 interviewees were 20–62 years of age. Seven of the interviewees reported New Zealand European as their only ethnicity, and four self-reported one or more ethnicities, including Māori, Chinese, and non-New Zealand European. Six of the interviewees identified as non-binary, some of whom specified other gender identities (e.g. non-binary and transfeminine, non-binary and agender, non-binary man). The other five interviewees selected a binary gender only (three are women, two are men). In terms of sexual orientation, two interview participants indicated they are asexual, three bisexual, two pansexual, and four selected queer as their sexual identity. Three participants identified themselves as lesbians, and one identified as a gay man. No interview participants reported being straight or questioning. Three participants were employed full-time and six were employed part-time. Two participants were not in paid employed, one of whom was seeking employment. None of the participants reported being unable to work due to health. Two participants reported that their household income was not enough to cover essential bills (e.g. power, rent/mortgage) when they filled out the recruitment survey. Five participants reported receiving state income benefits.

Upon receiving confirmation of interest in participating, the lead researcher sent an email which was consistent across all participants, containing: a preamble, the preliminary interview question, and the sign off. The preamble outlined the expectations around pacing, addressed best practice for email security, and provided a statement on how this research was seeking insights from those who are best positioned to comment on the issue, i.e. TGD people. The email sign off included a reminder about the pacing of the email interviews being up to the interviewee as well as a link to learn more about the project via social media, and resources to support people who had experienced medical mistreatment. All subsequent emails in the interview exchange included the same sign off. In follow-up emails, the body of the message was a tailored response containing a section mirroring what the participant had conveyed in their previous email, and then posing either follow-up questions or giving a wrap up statement indicating the end of the email interview process. The average number of exchanges in email interviews was four participant responses. The various components of the email interviews are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Email interview schedule.

|

If a participant responded to the invitation to participate in an email interview: Please read the following question and reply to this email at your own pace with as much detail as you feel is appropriate: Could you please recall and describe one or more positive experiences with your general practitioner (GP)? The experiences you describe can be anything from a story of an entire positive visit to a GP to a single example of something positive you saw or heard. Please describe what happened and what made it positive for you. Feel free to describe things that happened or feelings you had. You can share anything from before, during, and after the visit. You are welcome to add as many details as you want. Please note that these emails will be anonymized for the research, so any names of people or practices or locations will be removed. As this project is looking at positive experiences with GPs, regardless of the purpose of the visit, you do not need to include the medical aspects unless you feel any particular medical detail is relevant to telling me about your experience. Please feel free to add anything else that you would like me to know in relation to your healthcare experiences. |

| Recommendations for digital security during email interview participation (text included in initial email): |

| Thank you for your participation in this project. To protect your privacy, all emails in this interview will be kept in a password protected computer and not attached to your email address. If you have any concerns about privacy, you could delete emails about the study from your inbox and sent messages. We also recommend using a private email account that only you have access to, and avoiding using unsecured wi-fi. If you find recalling your experiences of healthcare unpleasant or difficult, please remember that you can withdraw from the project at any point in the email interview by emailing me to let me know. |

| Resources in sign off, included in each email exchange (text included in all emails): |

| This interview will not be live, but I will attempt to be as prompt as possible. You can respond at a time that is best for you, and I will follow up during my work day hours. For more information on this project and some resources please visit the social media page for this project: Link supplied To report inappropriate treatment from a medical professional, please contact Nationwide Health and Disability Advocacy Service Link supplied or the Health and Disability Commission Link supplied. |

| Description of mirroring used in email interviews: |

| Mirroring is the process of summarizing or describing what the participant says when answering an interview question. The mirroring process provided opportunity for participants to clarify within the interview process. Phrases like “…it sounded like…” or “…it seems like…” were used to provide the option for correcting the main researcher during the interviews. Mirroring could sound like “It sounded like you had a plan and were well prepared going into this appointment.” This process also allowed clarity in asking follow up questions pertaining to a specific aspect of something the participant said, such as “You mentioned that your current GP is consistently caring and respectful and that you have a lot of trust in her. Could you tell me more about how those qualities were positive for you?” |

| Examples of responsive follow-up questions: |

|

Analysis

The analysis followed the six stages of thematic analysis described by Braun and Clarke (2006). Data collection and analysis occurred concurrently using a constant comparative method (Glaser, 1965). The cyclical ongoing process systematically compared the data to previous interviews. After an interview was concluded, the data were imported from the interview protocol document into NVivo 12 (2019). The coding was selective for passages that related to the aim of exploring positive experiences with primary care, although this included focus on negative experiences as these were used to frame positive experiences, as explained in the themes. As suggested by Braun and Clarke (2013), the “pre-existing theoretical and analytical knowledge” (p. 206) of insider research informed the formulation of codes. A dynamic process was used to create the codes, incorporating new observations and understandings of the data as they were formulated. Ongoing review of the data was conducted in order to define and finalize the themes and subthemes.

Results

Three themes were formulated from the analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the themes and their interactions.

Theme 1: The sad state of care

Participants described a disenfranchizing healthcare context for TGD people within which their relatively rare positive experiences with primary care existed. This context is presented as a theme labeled ‘The Sad State of Care’. Negative experiences were described as essential to understand in order to make sense of rare positive experiences and included personal history of negative experiences that informed expectations and hearing about other TGD community members having negative experiences. The result was a perception of negative experiences with healthcare being ubiquitous for TGD people. Participants also frequently discussed the ways they anticipated negative experiences, such as mistreatment or denial of services. Participants acknowledged that while they were asked about the positive experiences, the larger context of their overall experiences was relevant to understanding their responses:

P9: I feel like I’m mostly complaining about bad things rather than focusing on the good, my bad. I guess it’s because it seems legitimately ridiculous to just type things like "it’s a good visit because the doctor knew more about medicine than me" without qualifying that.

Healthcare providers’ lack of knowledge around trans-specific healthcare was a barrier to care for participants in multiple ways. Participants were concerned that GPs were unable to provide appropriate care, or that they may be denied care on the basis of providers not understanding the essential nature of gender affirming care. Participants discussed the harmful ramifications of GPs not knowing the best practice for engaging with TGD patients, and choosing inaction over upskilling:

P7: “do no harm” is not “do nothing”, and that a refusal to act and support gender diverse patients is unethical! I think if we’re able to get that notion across - that deciding to withhold treatment because you’re worried about ‘doing harm’ to an uncertain patient is doing harm in itself

Participants felt they lacked control over their medical transition treatment plans. They considered this particularly important when healthcare professionals are unable to provide care due to lack of knowledge around medical transition services and pathways:

P2: I had been having trouble with finding someone who would actually listen to what I was saying, and take me seriously. My GP at the time felt too out of her depth and the endocrinology department was very dismissive. I could only get the bare minimum of care.

There was a strong tension between what participants noted they wanted or needed from their interactions with primary care providers and what they expected or anticipated from their interactions with those providers. Participants described addressing this mismatch between medical need and expectation of mistreatment or lack of knowledge by taking matters into their own hands and finding a sphere of control.

Theme 2: The sphere of control

While participants experienced the barriers to care illustrated in the previous theme, they also advocated for themselves and their communities in a variety of ways (Figure 1). This theme is centered on participants’ response to overcome the sad state of healthcare access for TGD people. They also described how they took control of their primary healthcare to empower themselves where they could. Participants exercising control was seen in their careful selection of a GP or choosing a specific moment to disclose transgender status to a GP. Seeking recommendations or insights from community resources was another core aspect of taking control of healthcare. Participants’ actions were carefully planned in the hope of improving the interaction or to increase the likelihood of positive outcomes in meetings with GPs.

As the pathway to medical transition is through GPs, who could limit access to those services, participants felt a limited amount of control over those services. Systematic approaches were used by participants to seek GPs who might be supportive; some participants used trial and error to find a good fit. Other participants engaged in active research, seeking recommendations from other community members and crowdsourcing knowledge:

P6: Generally emailing is the most I can do to prepare myself, as well as looking in rainbow Facebook pages for recommended GPs or warnings to stay away from certain ones.

Inappropriate or derogatory comments from GPs or staff were commonly anticipated, and some participants described having a specific contingency plan in place to protect themselves from potential negative interactions:

P6: I stay alert and wary and keep in mind that a new doctor might accidentally/intentionally say something rude, and am prepared to jump ship immediately if I feel offended.

Participants described a widespread perception that healthcare providers lacked trans-specific healthcare understanding, including having more transgender health-specific knowledge than their providers due to having community knowledge.

P4: I belong to a trans/nonbinary Facebook group, where a lot of the talk is about accessing hormones and surgery, and how difficult this is because of GPs not invested in the patient’s welfare, badly misinformed at best to transphobic at worst GPs, GPs who give misinformation or are uninformed about hormones, bad gynaecological/prostate and sexual health care, and bad communication in DHBs [District Health Boards] with regards to surgery (wait lists, surgeons available, waiting times).

While some participants believed that TGD people should be advocates and educators when engaging with the healthcare system, most discussed how GPs’ lack of knowledge on the existence of TGD people or medical transition needs was a negative.

P1: As I expected, my GP had no idea what i was talking about, but to his credit he admitted it and asked me for guidance…we need to be our own best advocates and educators.

There is a dissonance between being an authority with lived experience and practical knowledge through the community, while also being a patient at the mercy of the healthcare system. Participants described the common experience of knowing more about TGD healthcare than a healthcare provider. Some participants saw the need to be “patients as experts” as a natural requirement of seeking transgender healthcare, others found the expectation for TGD patients to provide that knowledge set disappointing:

P9: At my previous GP, I was on [hormone therapy] for over a year before I had any blood tests done, and it only happened because I asked for them. I think a basic working knowledge of trans healthcare is sort of the bare minimum we should expect.

There were also participants who found their GP asking for advice to be reassuring, in that the GP understood or recognized the participant’s expertise on transgender issues:

P4: I told her how pleased and proud I was her practice was making the effort, and she told me how she was eager to lead further training for other practices in the region. She asked me if there were any community rainbow groups I would recommend they work with, I told her of the ones I knew, many of which she was in the process of contacting. She also said she is keeping up with all the best practice and legal changes with regards to gender reassignment surgery, hormones, etc.

There was sometimes a sense of community building or using one’s knowledge to benefit other members of the TGD community. Some participants described being resigned to what they described as a deeply flawed medical system, while others were hopeful that it could improve, and some even saw themselves as potential agents of change.

The ways in which TGD participants were able to exert autonomy and work to ensure the least stressful situation when engaging primary healthcare was of note. The term reactive self-determination was therefore created to describe how the context of participants’ disenfranchisement is named as a cause of harm, while still acknowledging the dedication and work they put into improving the chances of positive interactions through their sphere of control. This term is useful in describing the negative interactions with healthcare that participants described in this theme, while simultaneously acknowledging patient decisions from a strengths-based perspective. Using the lens of reactive self-determination centers the autonomy of TGD participants, and their ingenuity and resourcefulness as a way of increasing the likelihood of positive experiences. Reactive self-determination is observable as an individual attribute, but the responsibility in addressing the barriers to care still lies with healthcare providers and healthcare systems.

Theme 3: Gradient of positive experiences

The third theme describes a Gradient of Positive Experiences that TGD participants had with GPs. Participants’ descriptions of positive experience varied from basic respect, all the way through to GPs being advocates for improving healthcare access for TGD community members. This gradient is comprised of three ordered subthemes: positive experiences of a basic nature, called Basic Doctoring (subtheme 3.1); followed by more desirable experiences of trans-specific competences in the subtheme, Better Practice (subtheme 3.2); and then an aspirational ideal, where some GPs were not solely providers of trans-competent care, but also advocates for systemic change to improve health outcomes for TGD people, the subtheme Next Level Support (subtheme 3.3).

Subtheme 3.1: Basic doctoring

The first subtheme within the Gradient of Positive Experiences, Basic Doctoring, contains examples of basic professionalism, kindness, and trust-building. This subtheme was comprised of straightforward examples of positive experiences with GPs. Many participants prefaced their descriptions with an explanation for why it was positive; most often expectations of mistreatment made the positive interaction a pleasant surprise. Some participants had an existing positive relationship with their GP that enabled them to come out about transgender-specific healthcare needs. This description was not of a one-off positive interaction, but of a history together, an ongoing building of a rapport. For example, one of the participants with an existing positive relationship with their GP describes how the GP’s understanding of intersectional issues, including reproductive rights, and weight stigma were part of building a positive relationship with this participant:

P4: We have a long history together, and being able to speak freely about a variety of issues with only positive and reinforced feedback has created a good working relationship.

Kindness and compassion stood out as simple things that were positive. Participants described how after having one positive experience they might be willing to see the GP a second time, and so on. The continuing process of being vulnerable with a GP and receiving a positive response, over and over again, created trust. For example, trust was described by one participant as an ongoing consistency of positive outcomes, potentially easily shattered by a negative one:

P5: I think the combination of small things is important. They probably boil down to 1) GP can actually provide the medical care needed, and 2) the GP is kind and understanding and listens to you. Which would be true for treatment beyond gender/transition related things too, and for all people! If you have one without the other it’s not going to be a positive experience at the GP. Both can be showed through small things… if you had a negative experience about one of these factors it will probably feel like a really big deal, but positive experiences with these things will feel like small pluses which add up to an impression of being looked after.

Visual cues, as well as social ones, were mentioned as examples of GPs building rapport or building trust with the participants. One participant explained that transgender-specific visual signaling might have made them feel comfortable coming out to their GP sooner:

P4: Positive signalling might be helpful too eg: a Safer Spaces pledge and/or Rainbow commitment poster, flags/pins. Sounds a bit basic, but I know I would have been open a lot earlier if my old practice had signalled like that.

Additionally, primary care intake forms were a potential way to create positive experiences, if done well:

P9: the options for gender on the form were ‘Male’, ‘Female’, or ‘Reason for "Other" status’, which is definitely better than just having male/female options, but still kind of an off-putting way of wording it - nobody’s being asked to give the ‘reason’ they’re ticking male or female. I think the most ‘inclusive’ option would probably be a write-in gender box for everybody rather than having any tick boxes? It’s not gonna hurt cis people to have to write ‘male’ or ‘female’ and it’d help to stop (literally) "Othering" everybody else.

Subtheme 3.2: Better practice

The second subtheme within the Gradient of Positive Experiences, Better Practice, included GPs displaying a solid foundational knowledge of gender and transgender concepts, the specifics of medical transition needs, and the health system pathways to achieve them. These TGD-specific competencies are in addition to the professionalism required in all aspects of being a healthcare provider. Participants were often accustomed to being in the position of ‘expert’ and found it positive to have an interaction with a GP who provided a knowledgeable foundation:

P9: I realise it’s unreasonable to expect all doctors to know everything about all conditions, but it’s genuinely comforting to me that [my doctor] is the one that suggests testing my liver function, hormone levels etc.

Participants saw it as positive for GPs to understand both the needs of TGD patients, as well as how those needs might be met by services within the larger healthcare system in which participants received care. Understanding the systemic shortcomings and how gender and healthcare systems interacted was a way that GPs were able to meet the needs of participants. For example, one participant described the notes and gender markers put in their medical records by their GP, and that it was positive:

P7: She also was quite conscious of ways to work around and within the systems, and included a note in my file that simply read “does not need cervical smears - does not have a cervix”, which I appreciated in its avoidance of gendered language.

Subtheme 3.3: Next level support

The final subtheme within the Gradient of Positive Experiences, Next Level Support, describes the ways that, in addition to professionalism and good practice, GPs being advocates for the participants or the wider TGD community was the ideal state of positive experiences. Beyond understanding medical transition or identity-specific needs, these GPs were able to support participants as they engaged with other aspects of the healthcare system. Some GPs were described as even working for systemic changes to improve trans-competencies in healthcare or improve service access for TGD patients.

Understanding how TGD people’s interactions with other aspects of the healthcare system might relate to gender experiences and helping advocate for those people was one of the central ways that GPs showed Next Level Support. The experiences of this subtheme included GPs advocating for patients, enabling patients to self-advocate, as well as showing understandings of the larger systemic forces with which the participants had to contend:

P8: He made it positive by encouraging me to find a midwife that supported my gender identity and checking in with me that this was working out, always referring to me as a father etc. and using gender inclusive language whenever discussing pregnancy and nursing.

Discussion

This research sheds new light on what TGD adults in Aotearoa New Zealand consider to be positive interactions with primary care. The findings contribute to the improvement of primary healthcare by identifying good practice in primary care from TGD patient perspectives. The three themes provide concerning insight into expectations of poor healthcare experiences contrasted against the various ways TGD participants were able to advocate for themselves in order to access acceptable primary care. The themes show how TGD participants’ experiences of primary care are contextualized within an inhospitable system and anticipation of mistreatment.

The finding that participants anticipate negative interactions with health care supports and extends on past research, demonstrating it is a barrier to appropriate care (Gibson et al., 2016; Poteat et al., 2013; Veale et al., 2019). Overall, this study shows how TGD people are forced to make decisions to self-advocate, often choosing between two potentially harmful situations. Both the unfortunate state of healthcare options, as well as the ingenious ways TGD adults find ways to try and improve their experiences through what we term reactive self-determination are reflected in the wider literature (Bartholomaeus et al., 2021; Burns, 2006; Cruz, 2014; Dewey, 2008; Dutton et al., 2008; Gibson et al., 2016; Pearce, 2018; Poteat et al., 2013; Roller et al., 2015; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017; Ross et al., 2016; Rossman et al., 2017; Rounds et al., 2013; Scheim et al., 2013), but this interplay has not been explicitly named until now.

The findings of this research support the literature describing a range of ways healthcare is inaccessible to TGD adults: systemic failures of the healthcare system to provide essential care, lack of GP competencies, anticipation of mistreatment or a history of mistreatment (Brotman et al., 2002; Cruz, 2014; Dewey, 2008; Gibson et al., 2016; Kattari et al., 2019; Klein & Golub, 2020; Lykens et al., 2018; Poteat et al., 2013; Roller et al., 2015, 2015; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017; Sanchez et al., 2009; Scheim et al., 2013; Treharne et al., 2022a). Participants in this research have also described barriers to care, such as expecting long waiting lists and gatekeeping processes to gender affirming care, similar to findings of other research (Bartholomaeus et al., 2021; Clark et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2013; Gridley et al., 2016; Ker et al., 2021; Ross et al., 2016).

Many healthcare providers are not equipped to provide appropriate care for TGD patients (Bartholomaeus et al., 2021; Bauer et al., 2009; Poteat et al., 2013; Roller et al., 2015; Ross et al., 2016; Treharne et al., 2022a), but the participants in this study described exerting control over their own healthcare interactions by making the decision to move to a new practitioner. This aspect of TGD participants exerting autonomy is present throughout the findings of this research project. The wider literature supports this finding with TGD patients resisting barriers to healthcare through dedication, self-advocacy, and exerting agency (Dutton et al., 2008; Poteat et al., 2013; Roller et al., 2015), and making choices to improve access to health services (Gibson et al., 2016; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017; Rossman et al., 2017). Both the findings of this research, and the broader literature on TGD healthcare access, illustrate the sad state of healthcare access for TGD adults is a widespread issue.

The theme about spheres of control demonstrates the areas in which TGD participants were able to engage with the healthcare system while protecting themselves from potential harms, and increase the likelihood of positive experiences. Participants in this research described ways they managed this ‘lesser of two evils’ decision making: navigating choices between potential negative interactions, avoiding the interaction by postponing care, or attempting to mitigate the harms of either. The ways TGD people maintain agency when facing the sad state of healthcare is supported by the literature, with past research demonstrating how TGD people resist barriers to healthcare through dedication, self-advocacy, and exerting agency (Dutton et al., 2008; Poteat et al., 2013; Roller et al., 2015), as well as making choices to improve access to health services (Gibson et al., 2016; Romanelli & Hudson, 2017; Ross et al., 2016).

The metric by which TGD participants in this research categorized healthcare practitioners positively was more nuanced than the binaries of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ or ‘positive’ and ‘negative’. There was a tension in TGD participants naming positive experiences within a largely inadequate system. Some participants in this study acknowledged that even with improvements to the status quo, the overall experience was still not positive. In turn, experiences with practitioners fall on a gradient of positivity, dependent on a range of factors. Of the literature that has explored the experiences of TGD patients engaging with healthcare providers, little research has focussed on positive experiences specifically, with some exceptions such as the work of Ross et al. (2016). They found that provider characteristics are most often what defined a positive experience for transgender patients. When their participants were asked about positive experiences, they also described systemic failures that contributed to negative experiences (Ross et al., 2016). The positive experiences described by the participants of this study were not all of the same nature of positivity.

Recommendations

Improvements for providing high quality TGD primary healthcare could be pursued through many different avenues. High-level systemic changes to the healthcare system would have wide reaching impacts on healthcare access for TGD adults. Improvements to healthcare system resourcing and transparency would allow more opportunity to build trust between TGD patients and providers given that these issues are often discussed during primary care visits. Improved working conditions might allow primary care providers more time for professional development to upskill on systemic issues, including ones relevant to TGD patients (a high-level change that would enable mid-level change). Governmental allotment of funding could allow for decreased waiting times for gender affirming care as well as universal access through subsidizing those services fully. Normalizing and increasing access to telehealth options would potentially increase equity by enabling access to essential care for TGD people who live rurally or in regions that have limited TGD-specific care options. This could have considerable benefits for all TGD patients in the era of COVID-19 and in countries with disparate population density or medical resource distribution.

Mid-level systemic changes could increase knowledge and professional resources for the providers of primary healthcare to TGD adults. Increasing their competencies on TGD healthcare needs would have significant impact without enacting change at a healthcare funding level. Best practice documents that are evidence-based and community-informed are ideal resources for the provision of gender affirming care. This includes both primary best practice documents, such as version 8 of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People (Coleman et al., 2022), and supplementary documents, such as the 2018 Guidelines for Gender Affirming Healthcare for Gender Diverse and Transgender Children, Young People and Adults in Aotearoa New Zealand (Oliphant et al., 2018). In addition to the suggestion for improvement, it is vital that these documents are known to those who might use them. Therefore, pathways for increased access to and awareness of these documents is also essential.

Healthcare providers’ familiarity with TGD health issues allowed for positive experiences for TGD patients, described in the Gradient of Positive Experiences theme, and supported by the literature (Bartholomaeus et al., 2021; Dutton et al., 2008). Increasing the avenues through which a GP can upskill in this area may increase opportunities for TGD patients to have more positive experiences. Continuing education courses on trans-specific healthcare needs would improve knowledge and empower GPs to engage with TGD people and communities respectfully and appropriately.

In addition to the uptake of educational and professional development courses, there are healthcare infrastructures that can enable positive experiences for TGD patients. In the Better Practice and Next Level Support subthemes of the Gradient of Positive Experiences theme, participants describe how their positive experiences were limited by medical information software and intake forms. The wider literature also discusses the ways in which these intake forms are often designed to reflect simplistic software fields and can therefore serve as a limitation to or a facilitator of positive experiences for TGD patients (Bartholomaeus et al., 2021; Dutton et al., 2008).

The small step of updating intake forms to be TGD inclusive could also provide a way to improve positive experiences for TGD patients. Even if a GP is limited by the clinician-facing medical software, the patient-facing intake forms can account for TGD patients. The Gradient of Positive Experiences theme and the wider literature describes intake forms as a fraught experience for TGD participants (Dutton et al., 2008). Trans-inclusive forms are a recommended improvement to support TGD patients (Clark et al., 2018; Dutton et al., 2008).

Individual-level service improvements would be decisions healthcare providers can make for themselves and their practices to increase the likelihood of positive experiences for their TGD patients. In addition to the midlevel initiatives, there are also individual actions that GPs can take to improve patient experience. Existing consultation models provide avenues by which a GP can build trust, show empathy, and establish a collaborative relationship with patients (Denness, 2013). Applying existing knowledge and consciously engaging with existing models while working with TGD patients could allow for more positive patient experiences. Some of the ways GPs can potentially improve the experiences of TGD patients would be ensuring they are following the recommendations provided by best practice documents and electing to participate in Continuing Medical Education and Continuing Professional Development.

Strengths and limitations

Qualitative methods are appropriate for exploring the feelings and experiences of people about accessing care, especially on sensitive topics or when working with vulnerable groups (Braun & Clarke, 2013; Gibson, 2017). The email interview method was particularly effective at eliciting data that would both explore the positive experiences of TGD adults, as well as providing practically useful results to inform best practice. The ability for the interviewer to consider subsequent responses as part of an email interview process is a strength in that it allowed more thoughtful and conscientious responses. Mirroring was used in the interviews, by reflecting back what the participants said in earlier parts of their email exchange, and providing an opportunity for participants to clarify or correct within the interview process. The participants were able to reread a prompt or question as many times as needed, to fully formulate their answer, which is a form of respondent validation.

Email interviews are more accessible to some participants, for whom meeting in person may be a high pressure social interaction, and a barrier to participation (Braun & Clarke, 2013). The anonymity of email interviews may have allowed participants to be more at ease and open in their responses; however, this method might have reduced the rapport building that can occur in face-to-face interviews. This reduced ability to build rapport with participants may explain those who expressed an interest in participating but did not reply to the opening email question. Interviews being conducted over email also allowed the research to involve participants from across the country, and not just a localized area.

The digital nature of both the recruitment questionnaire and the interviews may have been a barrier to participation, in that there may be limitations in access for people living in remote areas, or those with low socio-economic status or other potential participants who did not have consistent access to email, social media, internet, or technology. Addressing these barriers will be important for future research that builds on the findings of this study in other countries with distinct healthcare systems and distinct considerations about access to care across regions within countries. While this was a nationwide sample and attempts at maximum variation were made, the majority of participants were White, and people of other ethnicities were underrepresented as were people from certain parts of the country. As tauiwi (non-Māori), researchers were mindful of cultural safety and ethics as per local guidance (Delany et al., 2015; Edwards et al., 2023). Our study materials included details encouraging people with Māori and other Indigenous trans and nonbinary identities to participate, but our sample ended up with an underrepresentation of Māori as the Indigenous peoples of Aotearoa New Zealand. This may reflect barriers to participation such as being busy or mistrust of research among Māori and TGD people, despite our efforts to signal the research was culturally safe and led by a transgender researcher. Further effort is needed in future that has a wider scope and in collaboration with Māori researchers. Ideally, future research in Aotearoa New Zealand can include further consultation processes with Māori healthcare providers and Māori-led TGD groups about ways to advertise research and address any concerns, and similar protocols can be applied with Indigenous/marginalized people in other countries. In particular, we recommend that future research make use of a community advisory group working in a paid capacity and offering a range of interviewers with knowledge of relevant languages, including Māori for research in Aotearoa New Zealand. This could entail regional representatives including members of Indigenous communities and other marginalized communities such as refugees. Having a network of regional representatives could help to increase recruitment across a country or internationally by having a contact person who is knowledgeable of the regional social landscape and needs of TGD people in these areas and able to help ensure cultural safety. Innovative methods of engaging participants and working toward inclusion of Māori through Māori-led research hold promise for future research (Dyall et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2023; Kearns et al., 2021). We also note that there are considerable variations among TGD people, and future research will benefit from considering the breadth of TGD experiences more widely and with greater insider input than can be achieved in a project led by a transgender scholar-activist guided by cisgender supervisors. Collaborative research by networks of transgender scholar-activists hold much promise for expanding on the important contributions that this study makes.

Conclusion

This study explored the positive experiences of TGD adults engaging with primary care, and expands upon what is understood about TGD experiences engaging with GPs. These findings and recommendations help to inform best practice and future research into TGD healthcare experiences. In seeking changes that could be implemented in primary care practices, these findings support recommendations through which positive healthcare interactions for TGD patients could be increased.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this paper would like to thank all the participants, whose input helped make this project possible.

Funding Statement

The authors reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Ethics approval

All procedures were conducted in accordance with ethical standards, and approval was granted by the University of Otago Human Ethics Health Committee (reference H18/128). Informed consent was obtained from all interviewees.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants did not agree for their data to be shared publicly so supporting data are not available.

References

- Bartholomaeus, C., Riggs, D. W., & Sansfaçon, A. P. (2021). Expanding and improving trans affirming care in Australia: Experiences with healthcare professionals among transgender young people and their parents. Health Sociology Review, 30(1), 58–71. 10.1080/14461242.2020.1845223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, G. R., Hammond, R., Travers, R., Kaay, M., Hohenadel, K. M., & Boyce, M. (2009). “I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives”: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 20(5), 348–361. 10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners (1st ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman, S., Ryan, B., Jalbert, Y., & Rowe, B. (2002). Reclaiming space-regaining health: The health care experiences of two-spirit people in Canada. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 14(1), 67–87. 10.1300/J041v14n01_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, C. (2006). Not So Much a Care Path. Yahoo discussion group. https://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20061116120000/http:/www.pfc.org.uk/files/steeple.pdf

- Clark, B. A., Veale, J. F., Greyson, D., & Saewyc, E. (2018). Primary care access and foregone care: A survey of transgender adolescents and young adults. Family Practice, 35(3), 302–306. 10.1093/fampra/cmx112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E., Radix, A. E., Bouman, W. P., Brown, G. R., de Vries, A. L. C., Deutsch, M. B., Ettner, R., Fraser, L., Goodman, M., Green, J., Hancock, A. B., Johnson, T. W., Karasic, D. H., Knudson, G. A., Leibowitz, S. F., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Monstrey, S. J., Motmans, J., Nahata, L., … Arcelus, J. (2022). Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health, 23(suppl. 1), S1–S259. 10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, T. M. (2014). Assessing access to care for transgender and gender nonconforming people: A consideration of diversity in combating discrimination. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 110, 65–73. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A., Bouman, W. P., Richards, C., Barrett, J., Ahmad, S., Baker, K., Lenihan, P., Lorimer, S., Murjan, S., Mepham, N., Robbins-Cherry, S., Seal, L. J., & Stradins, L. (2013). Patient satisfaction with gender identity clinic services in the United Kingdom. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 28(4), 400–418. 10.1080/14681994.2013.834321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delany, L., Ratima, M., & Morgaine, K. C. (2015). Ethics and health promotion. In Signal L. & Ratima M. (Eds.), Promoting health in Aotearoa/New Zealand (pp. 121–145). Otago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denness, C. (2013). What are consultation models for? InnovAiT, 6(9), 592–599. 10.1177/1755738013475436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. M. (2008). Knowledge legitimacy: How trans-patient behavior supports and challenges current medical knowledge. Qualitative Health Research, 18(10), 1345–1355. 10.1177/1049732308324247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, L., Koenig, K., & Fennie, K. (2008). Gynecologic care of the female-to-male transgender man. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 53(4), 331–337. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyall, L., Kepa, M., Hayman, K., Teh, R., Moyes, S., Broad, J. B., & Kerse, N. (2013). Engagement and recruitment of Māori and non-Māori people of advanced age to LiLACS NZ. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 37(2), 124–131. 10.1111/1753-6405.12029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards (Taranaki Iwi, Ngāruahine, Tāngahoe, Pakakohi, Ngāti), W., Hond (Taranaki Iwi, Ngāti Ruanui, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui, Te Ati), R., Ratima (Ngāti Awa, Whakatōhea), M., Tamati (Taranaki Iwi, Ngāti Ruanui, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui, Te A), A., Treharne, G. J., Hond-Flavell (Taranaki Iwi, Ngāti Ruanui, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui), E., Theodore (Ngāpuhi), R., Carrington (Te Arawa, Ngāti Hurungaterangi, Ngāti Taeotu), Ng, S. D., & Poulton, R. (2023). Tawhiti nui, tawhiti roa: Tawhiti tūāuriuri, tawhiti tūāhekeheke: A Māori lifecourse framework and its application to longitudinal research. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 53(4), 429–445. 10.1080/03036758.2022.2113411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, B. A., Brown, S.-E., Rutledge, R., Wickersham, J. A., Kamarulzaman, A., & Altice, F. L. (2016). Gender identity, healthcare access, and risk reduction among Malaysia’s mak nyah community. Global Public Health, 11(7-8), 1010–1025. 10.1080/17441692.2015.1134614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, L. (2017). Type me your answer”: Generating interview data via email. In Braun V., Clarke V., & Gray D. (Eds.), Collecting qualitative data: A practical guide to textual, media and virtual techniques (pp. 213–234). Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/9781107295094.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. 10.2307/798843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley, S. J., Crouch, J. M., Evans, Y., Eng, W., Antoon, E., Lyapustina, M., Schimmel-Bristow, A., Woodward, J., Dundon, K., Schaff, R., McCarty, C., Ahrens, K., & Breland, D. J. (2016). Youth and caregiver perspectives on barriers to gender-affirming health care for transgender youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(3), 254–261. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattari, S. K., Atteberry-Ash, B., Kinney, M. K., Walls, N. E., & Kattari, L. (2019). One size does not fit all: Differential transgender health experiences. Social Work in Health Care, 58(9), 899–917. 10.1080/00981389.2019.1677279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattari, S. K., Walls, N. E., Speer, S. R., & Kattari, L. (2016). Exploring the relationship between transgender-inclusive providers and mental health outcomes among transgender/gender variant people. Social Work in Health Care, 55(8), 635–650. 10.1080/00981389.2016.1193099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ker, A., Fraser, G., Fleming, T., Stephenson, C., da Silva Freitas, A., Carroll, R., Hamilton, T. K., & Lyons, A. C. (2021). ‘A little bubble of utopia’: Constructions of a primary care-based pilot clinic providing gender affirming hormone therapy. Health Sociology Review, 30(1), 25–40. 10.1080/14461242.2020.1855999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, C., Baggott, C., Harwood, M., Reid, A., Fingleton, J., Levack, W., & Beasley, R. (2021). Engaging Māori with qualitative healthcare research using an animated comic. Health Promotion International, 36(4), 1170–1177. 10.1093/heapro/daaa111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A., & Golub, S. A. (2020). Enhancing gender-affirming provider communication to increase health care access and utilization among transgender men and trans-masculine non-binary individuals. LGBT Health, 7(6), 292–304. 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykens, J. E., LeBlanc, A. J., & Bockting, W. O. (2018). Healthcare experiences among young adults who identify as genderqueer or nonbinary. LGBT Health, 5(3), 191–196. 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . (2011). Eligibility for publicly funded health services. New Zealand health system. https://www.health.govt.nz/new-zealand-health-system/eligibility-publicly-funded-health-services?mega=NZ%20health%20system&title=Eligibility%20for%20public%20health%20services

- Ministry of Health . (2017). Overview of the health system. New Zealand health system. https://www.health.govt.nz/new-zealand-health-system/overview-health-system

- Nobili, A., Glazebrook, C., & Arcelus, J. (2018). Quality of life of treatment-seeking transgender adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders, 19(3), 199–220. 10.1007/s11154-018-9459-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliphant, J., Veale, J., Macdonald, J., Carroll, R., Johnson, R., Harte, M., Stephenson, C., Bullock, J., Cole, D., & Manning, P. (2018). Guidelines for gender affirming healthcare for gender diverse and transgender children, young people and adults in Aotearoa. New Zealand, 131(1487), 11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, R. (2018). Understanding trans health: Discourse, power and possibility. Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat, T., German, D., & Kerrigan, D. (2013). Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 84, 22–29. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner, S. L., Poteat, T., Keatley, J., Cabral, M., Mothopeng, T., Dunham, E., Holland, C. E., Max, R., & Baral, S. D. (2016). Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: A review. Lancet (London, England), 388(10042), 412–436. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00684-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roller, C. G., Sedlak, C., & Draucker, C. B. (2015). Navigating the system: How transgender individuals engage in health care services: navigating health care. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(5), 417–424. 10.1111/jnu.12160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanelli, M., & Hudson, K. D. (2017). Individual and systemic barriers to health care: Perspectives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(6), 714–728. 10.1037/ort0000306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, K. A. E., Law, M. P., & Bell, A. (2016). Exploring healthcare experiences of transgender individuals. Transgender Health, 1(1), 238–249. 10.1089/trgh.2016.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossman, K., Salamanca, P., & Macapagal, K. (2017). A qualitative study examining young adults’ experiences of disclosure and nondisclosure of LGBTQ identity to health care providers. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(10), 1390–1410. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1321379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounds, K., Burns Mcgrath, B., & Walsh, E. (2013). Perspectives on provider behaviors: A qualitative study of sexual and gender minorities regarding quality of care. Contemporary Nurse, 44(1), 99–110. 10.5172/conu.2013.44.1.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safer, J. D., Coleman, E., Feldman, J., Garofalo, R., Hembree, W., Radix, A., & Sevelius, J. (2016). Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity, 23(2), 168–171. 10.1097/MED.0000000000000227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, N. F., Sanchez, J. P., & Danoff, A. (2009). Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. American Journal of Public Health, 99(4), 713–719. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.132035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheim, A. I., Jackson, R., James, L., Sharp Dopler, T., Pyne, J., & R. Bauer, G. (2013). Barriers to well-being for Aboriginal gender-diverse people: Results from the trans pulse project in Ontario, Canada. Ethnicity and Inequalities in Health and Social Care, 6(4), 108–120. 10.1108/EIHSC-08-2013-0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stotzer, R. L., Silverschanz, P., & Wilson, A. (2013). Gender identity and social services: Barriers to care. Journal of Social Service Research, 39(1), 63–77. 10.1080/01488376.2011.637858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K. K., Carroll, R., Treharne, G. J., Byrne, J. L., & Veale, J. F. (2022). I teach them. I have no choice”: Experiences of primary care among transgender people in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Medical Journal, 135(1559), 59–72. https://journal.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/i-teach-them-i-have-no-choice-experiences-of-primary-care-among-transgender-people-in-aotearoa-new-zealand [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treharne, G. J., Gamble Blakey, A., Graham, K., Carrington, S. D., McLachlan, L. A., Withey-Rila, C., Pearman-Beres, L., & Anderson, L. (2022a). Perspectives on expertise in teaching about transgender healthcare: A focus group study with health professional programme teaching staff and transgender community members. International Journal of Transgender Health, 23(3), 334–354. 10.1080/26895269.2020.1870189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treharne, G. J., Carroll, R., Tan, K. K. H., & Veale, J. F. (2022b). Supportive interactions with primary care doctors are associated with better mental health among transgender people: Results of a nationwide survey in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Family Practice, 39(5), 834–842. 10.1093/fampra/cmac005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veale, J., Byrne, J., Tan, K., Guy, S., Yee, A., Nopera, T., Bentham, R.; Transgender Health Research Lab . (2019). Counting ourselves: The health and wellbeing of trans and non-binary people in Aotearoa New Zealand. https://natlib-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=NLNZ_ALMA11333069400002836&context=L&vid=NLNZ&search_scope=NLNZ&tab=catalogue&lang=en_US

- Voronka, J. (2016). The politics of ‘people with lived experience’: Experiential authority and the risks of strategic essentialism. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 23(3–4), 189–201. 10.1353/ppp.2016.0017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants did not agree for their data to be shared publicly so supporting data are not available.