Abstract

Background

To better manage patients with a wide range of mental health problems, general practitioners would benefit from diagnostically accurate and time-efficient screening tools that comprehensively assess mental illness. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to identify screening tools that either take a multiple-mental disorder or a transdiagnostic approach. As primary and secondary outcomes, diagnostic accuracy and time efficiency were investigated.

Methods

The data bases MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, Psyndex and PsycINFO were searched. Studies reporting on multiple-mental disorder or transdiagnostic screening tools used in primary care with adult patients were included. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value served as measures of diagnostic accuracy. Time efficiency was evaluated by the number of items of a screening tool and the time required for its completion and evaluation.

Results

Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria. The majority of screening tools assessed multiple mental disorders separately. A sub-group of screening tools took a transdiagnostic approach by examining the spectrum of mood, anxiety and stress-related disorders. One screening tool used internalised, cognitive/somatic and externalised dysfunction as transdiagnostic domains of mental illness. Mostly, a sufficient sensitivity and specificity was reported. All screening tools were found to be time efficient.

Conclusion

The eleven identified screening tools can support general practitioners to identify patients with mental health problems. However, there was great heterogeneity concerning their diagnostic scope of psychopathology. Further screening tools for primary care are needed that target broad constructs of mental illness, such as transdiagnostic factors or personality dysfunction.

Keywords: Mental illness, primary care, general practitioner, index test, screening, transdiagnostic approach

KEY MESSAGES

Eleven screening tools assessing multiple mental health disorders or taking a transdiagnostic approach in primary care were identified.

The tools were time efficient, and offer a satisfactory diagnostic accuracy.

Future research should focus on screening tools that target transdiagnostic factors or maladaptive personality traits as informative constructs.

Introduction

Mental disorders are among the leading causes of the global health-related burden [1]. In 2023, almost half (46%) of respondents of a representative European survey reported an emotional or psychosocial problem [2]. Individuals with mental health problems tend to initially consult their general practitioner (GP) before seeking specialised psychotherapeutic services [3]. Thus, GPs play a crucial role in the management of mental disorders [4,5]. However, recognising mental disorders in primary care is challenging [6]. Potential difficulties may be physician-related (e.g. lack of experience in managing mental disorders [7,8]), patient-related (e.g. difficulties in acknowledging psychological distress [9]) and time-related (e.g. internationally, most GPs spend on average less than 10 minutes with a patient [10]). Another barrier is the high comorbidity rate between mental disorders in primary care [11]. Rather than using diagnostic criteria, the assessment of a patient’s mental health is usually guided by a GP’s general impression of a patient [12].

Due to these barriers, GPs could benefit from time efficient screening tools that reliably complement their diagnostic procedure and account for common mental disorders [13]. Instead of administering several single-disorder questionnaires, screening tools that assess multiple mental disorders could be promising [14]. Particularly useful might be multiple-mental disorder screening tools assessing depression, anxiety and somatoform disorders, as those are the most frequently observed mental disorders in primary care [11,15].

Although addressing comorbidity, the non-specific patterns rather than specific characteristics of mental illness in primary care remain a challenge for multiple-mental disorder screening tools [12,16]. Therefore, a transdiagnostic approach to screening for mental illness may be promising. Instead of defining symptomatic differences between mental disorders, it focuses on their commonalities, operating across or beyond single-disorder categories [17]. Transdiagnostic instruments may be employed in one of two ways: One possibility is to examine a broader spectrum of mental disorder symptoms, however, without entirely neglecting the criteria of conventional diagnostic frameworks (i.e. ICD [18] and DSM [19]) [20]. For instance, instead of screening for anxiety and depression separately, the spectrum of mood and anxiety-related disorders could be assessed. The second possibility is to screen for transdiagnostic factors, operating detached from standard diagnostic taxonomies [20]. Transdiagnostic factors are mechanisms that are hypothesised to underlie a range of mental disorders, contributing to their onset and persistence [21]. Several transdiagnostic factors have been proposed in previous research [22–24]. In terms of screening in primary care, transdiagnostic factors underlying ‘emotion-based disorders’ [25], such as anxiety and depression, may be particularly relevant [26,27]. Emotion-based disorders share an amplified experience of negative emotions (i.e. neuroticism), followed by an aversive reactivity to these emotions and the use of behavioural or cognitive coping strategies aimed at avoiding them [28]. Hence, screening tools assessing neuroticism, emotion regulation and/or emotion-based avoidance may serve GPs as transdiagnostic markers of their patients’ psychological distress.

To date, no other review has systematically searched for primary care screening tools that either assess multiple mental disorders separately or screen across or beyond conventional mental disorder classifications. Therefore, the aim of the current review was to systematically identify screening tools used in primary care which either (1) take a multiple-mental disorder approach or (2) target a transdiagnostic spectrum of symptoms or a transdiagnostic factor underlying mental illness. The primary outcome was the diagnostic accuracy of screening tools. As a secondary outcome, their time efficiency was assessed.

Methods

This systematic review and the following narrative synthesis adhere to the PRISMA guidelines [29]. The study protocol was registered at the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (ID: CRD42022382572) [30].

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search using the databases Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, Psyndex and PsycINFO was conducted. Further, the reference lists of relevant studies were hand-searched. The last search was performed on the 18 July 2024.

A block-building method was used to create the search string. The four blocks ‘primary care setting’, ‘questionnaire or screening tool’, ‘disorders or transdiagnostic factors’ and ‘diagnostic accuracy measures’ were defined (Appendix 1, Supplementary material).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if (1) they reported on a screening tool, i.e. an index test, assessing at least two mental disorders in the categories of depression, anxiety or somatoform disorders, or following a transdiagnostic approach; (2) the index test was compared with a well-established reference standard; (3) diagnostic accuracy measures of the index test were provided (i.e. sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) or values allowing their calculation); (4) the study population consisted of adult patients (5) attending primary care services administered by a GP.

Studies were excluded if (1) the sample consisted of a special sub-group of the general population, e.g. military veterans, (2) the publication was not peer-reviewed and (3) not written in German or English. No restrictions were made with regard to the publication date or study design.

Study selection and data extraction process

Initially, all search results were exported to EndNote [31], with duplicates being automatically removed. The remaining data were exported to Rayyan [32] and deduplicated a second time (automatic and manually by BN). Screening of titles/abstracts and full-texts was performed independently by two authors (BN, KLu) in blind mode. Remaining titles and abstracts were assessed for eligibility [32]. Then, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the screening of full-texts. Disagreements were resolved at each stage through discussion among authors (BN, KLu, CE, KLo). Data extraction was conducted independently by three authors (CE, BN, KLu) using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Cooperation, 2018). The data extraction form included: study design, characteristics of the study sample (sample size, country, age), type of index test and reference standard used as well as diagnostic scope, diagnostic accuracy and time efficiency (i.e. number of items, time needed for completion and evaluation) of an index test. If full-text articles were unavailable or in case of missing data, the authors of a study were contacted.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Diagnostic accuracy was assessed by the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of the index tests.

As PPV and NPV are influenced by the prevalence (i.e. pre-test probabilities) of a disorder in the study population [33] and the samples of the included studies were not representative, those measures are only reported in Table 1. Also, due to the heterogeneity in the study samples’ characteristics as well as in the reference standards and diagnostic criteria used, no comparison of the diagnostic accuracy scores of the different index tests was performed.

Table 1.

Study characteristics, diagnostic accuracy and time efficiency measures of index tests.

| Index test | Study | Population | Sample size | Reference standard | Dimensions of the index test | Corresponding dimension(s) of the reference standard | Cut-off points | Diagnostic accuracy (%) |

Time efficiency

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | SP | PPV | NPV | ||||||||||

| SDSS-PC | Broadhead et al. (1995) | Primary care patients, USA, 18 - 70 years (M = 38.5) | n = 388 | SCID-P (DSM-III) | Major depression, 5 items | Matching diagnosis according to DSM-III | Any 2 items with yes | 90.4 | 77.2 | 39.7 | 98.0 |

|

|

| Generalised anxiety disorder, 2 items | Any 1 item with yes | 89.8 | 54.0 | 5.4 | 99.5 | ||||||||

| Panic disorder, 3 items | Any 1 item with yes | 78.3 | 80.0 | 20.8 | 98.2 | ||||||||

| Obsessive compulsive disorder, 2 items | Any 1 item with yes | 64.5 | 72.5 | 5.1 | 98.9 | ||||||||

| Suicidal ideation, 2 items | Any 1 item with yes | 43.6 | 90.6 | 50.8 | 87.8 | ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence, 2 items | Any 1 item with yes | 61.8 | 98.2 | 53.8 | 98.7 | ||||||||

| HADS | Bunevicius et al. (2007) | Primary care patients, Lithuania, 18 - 89 years (M = 52) | n = 503 | MINI (DSM-IV /ICD-10) | Depression, 7 items | Major depressive episode | ≥ 6 | 80.0 | 69.0 | 80.0 | 92.0 |

|

|

| Anxiety, 7 items1 |

|

≥ 9 | 77.0 | 75.0 | 53.0 | 90.0 | |||||||

|

|

≥ 9 | 76.0 | 73.0 | 49.0 | 90.0 | |||||||

|

|

≥ 11 | 100.0 | 77.0 | 11.0 | 100.0 | |||||||

|

|

≥ 9 | 95.0 | 63.0 | 9.0 | 100.0 | |||||||

| CMDQ | Christensen et al. (2005) | Primary care patients, Denmark, 18 - 65 years (M = 38.8) | n = 1785 | SCAN (ICD-10) | Any mental disorder (i.e. depression and/or anxiety), 8 items | Matching diagnosis according to ICD-10 | ≥ 3 | 72.0 | 72.0 | 50.0 | 88.0 |

|

|

| Depressive disorder, 6 items | ≥ 3 | 78.0 | 86.0 | 39.0 | 97.0 | ||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder, 4 items | ≥ 3 | 39.0 | 87.0 | 38.0 | 88.0 | ||||||||

| Any somatoform disorder2, 19 items | |||||||||||||

|

≥ 5 | 65.0 | 63.0 | 52.0 | 74.0 | ||||||||

|

≥ 2 | 74.0 | 65.0 | 51.0 | 77.0 | ||||||||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence, 4 items | ≥ 2 | 78.0 | 97.0 | 34.0 | 99.0 | ||||||||

| M-3 | Gaynes et al. (2010) | Primary care patients, USA, 18 - 92 years (M = 45.7) | n = 647 | MINI (DSM-IV /ICD-10) | Any mood or anxiety disorder (i.e. depression, anxiety, bipolar, post-traumatic stress disorder), 23 items | Matching diagnosis according to DSM-IV/ICD-10 | Screening positive for any of the disorder subscales | 83.0 | 76.0 | 65.0 | 89.0 |

|

|

| Major depressive disorder, 7 items | ≥ 5 | 84.0 | 80.0 | 54.0 | 95.0 | ||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder | ≥ 3 | 82.0 | 78.0 | 59.0 | 92.0 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder, 4 items | ≥ 2 | 88.0 | 76.0 | 20.0 | 99.0 | ||||||||

| Bipolar disorder, 4 items | ≥ 2 | 88.0 | 70.0 | 23.0 | 98.0 | ||||||||

| Not reported | Functional impairment, 4 items | Not reported | ≥ 2 | Not reported | |||||||||

| MBHS | McCord (2020) | Primary care patients, USA, 18 - 79 years (M = 47.6) |

n = 166 | MMPI-2-RF | Internalising dysfunction |

|

|||||||

|

|

≥ 3 | 73.3 | 78.3 | 55.9 | 88.6 | |||||||

|

|

≥ 3 | 81.0 | 72.4 | 50.0 | 91.7 | |||||||

|

|

≥ 5 | 72.1 | 75.4 | 50.8 | 88.4 | |||||||

|

|

≥ 1 | 56.3 | 75.2 | 48.0 | 80.7 | |||||||

| Somatic/Cognitive dysfunction | |||||||||||||

|

|

≥ 4 | 75.0 | 73.0 | 70.3 | 77.3 | |||||||

|

|

≥ 5 | 80.8 | 83.2 | 68.8 | 68.4 | |||||||

| Externalising dysfunction | |||||||||||||

|

|

≥ 3 | 65.0 | 50.3 | 15.2 | 91.3 | |||||||

|

|

≥ 4 | 76.7 | 85.2 | 53.4 | 94.2 | |||||||

|

|

≥ 4 | 77.3 | 82.5 | 40.5 | 95.9 | |||||||

| ADD | Means-Christensen et al. 2006 | Primary care patients, USA, 18 - 70 years, (M = 41.49) | n = 801 | CIDI-Auto (DSM-IV) | Major depression, 1 item | Matching diagnosis according to DSM-IV | Item with yes | 85.0 | 73.0 | 63.6 | 90.0* |

|

|

| Generalised anxiety disorder, 1 item | Item with yes | 100.0 | 56.0 | 44.8 | 100.0* | ||||||||

| Panic disorder, 1 item | Item with yes | 92.0 | 74.0 | 67.0 | 93.7* | ||||||||

| Social phobia, 1 item | Item with yes | 69.0 | 76.0 | 51.8 | 86.7* | ||||||||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder, 1 item | Item with yes | 62.0 | 83.0 | 47.5 | 89.4* | ||||||||

| Individual items as indicators for the presence of any of the five disorders | Respective item with yes | ||||||||||||

|

78.0 | 80.0 | 78.2* | 80.0* | |||||||||

|

87.0 | 68.0 | 71.6* | 85.4* | |||||||||

|

72.0 | 92.0 | 90.2* | 76.1* | |||||||||

|

51.0 | 93.0 | 89.1* | 63.4* | |||||||||

|

33.0 | 91.0 | 80.0* | 55.1* | |||||||||

| DUKE-AD | Parkerson et al. 1996 | Primary care patients, USA, 18 - 65 years (M = 40.4) | n = 413 | CES-D | Depression3 | Depressive symptomatology | Raw score of ≥ 5; final score of ≥ 304 | 73.9 | 78.2 | 72.6 | 79.3 |

|

|

| SAI | Anxiety | State anxiety | 78.7 | 74.6 | 62.5 | 86.7 | |||||||

| PRIME-MD | Rickels et al. 2009 | Primary care patients, USA, > 18 years (M = 45) | n = 211 | PRIME MD clinical evaluation guide (DSM-IV) | Anxious and depressive symptomatology (Anxiety, 2 items; Depression, 2 items) | Matching diagnosis according to DSM-IV | ≥ 3 | 97.5* | 64.5* | 78.0* | 95.2* |

|

|

| MHI-5 | Means-Christensen et al. 2005 | Primary care patients, USA, 18 - 81 years (M = 41) | n = 246 | PHQ | Total score, 5 items | Panic and/or major depressive disorder | ≤ 23 | 90.9 | 57.6 | 17.4 | 98.5 |

|

|

| PHQ (Depression subscale) | Depression, 1 item | Major depressive disorder | ≤ 4 | 88.2 | 61.6 | 14.6 | 98.6 | ||||||

| PHQ (Panic subscale) | Anxiety, 1 item | Panic disorder | ≤ 4 | 100.0 | 65.4 | 9.9 | 100.0 | ||||||

| Not reported | Loss of behavioural or emotional control, 2 items | Not reported | |||||||||||

| Psychological wellbeing, 1 item | |||||||||||||

| CMFC | Rogers et al. 2021 | Primary care patients, USA, 18 - 82 years (M = 47.10) | n = 234 | SCID-5-RV (DSM-V) | Major depressive disorder, | Matching diagnosis according to DSM-V |

|

||||||

|

|

94.0 | 65.0 | 41.0 | 98.0 | ||||||||

|

|

45.0 | 93.0 | 63.0 | 0.87 | ||||||||

| Generalised anxiety disorder, | |||||||||||||

|

|

93.0 | 63.0 | 47.0 | 96.0 | ||||||||

|

|

73.0 | 89.0 | 63.0 | 93.0 | ||||||||

| Bipolar disorder, | |||||||||||||

|

|

63.0 | 79.0 | 42.0 | 89.0 | ||||||||

|

|

50.0 | 97.0 | 81.0 | 89.0 | ||||||||

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, | |||||||||||||

|

|

94.0 | 61.0 | 38.0 | 98.0 | ||||||||

|

|

69.0 | 86.0 | 54.0 | 92.0 | ||||||||

| Somatic symptom disorder, | |||||||||||||

|

|

100.0 | 78.0 | 53.0 | 100.0 | ||||||||

|

|

93.0 | 86.0 | 63.0 | 98.0 | ||||||||

| Substance and alcohol use disorder, | |||||||||||||

|

|

80.0 | 92.0 | 70.0 | 95.0 | ||||||||

|

|

67.0 | 96.0 | 79.0 | 92.0 | ||||||||

| PDI-4 | Houston et al. 2011 | Primary care patients, USA, > 18 years (M = 50) | n = 343 | SCID (DSM-IV) | Major depressive episode, 4 items | Matching diagnosis according to DSM-IV | At least 3 of 4 X’s must be in grey-shaded regions6 | 80.0 | 80.0 | 58.0 | 92.0 |

|

|

| Generalised anxiety disorder, 4 items | 83.0 | 75.0 | 20.0 | 98.0 | |||||||||

| Mania, 4 items | 83.0 | 82.0 | 26.0 | 98.0 | |||||||||

| ACDS | Attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), 4 items | Matching diagnosis according to ACDS | 82.0 | 73.0 | 42.0 | 97.0 | |||||||

| Daily functioning, 1 item7 |

|

not reported | |||||||||||

Note:.

SE = Sensitivity; SP = Specificity; PPV = Positive predictive value; NPV = Negative predictive value; M = Mean.

SDSS-PC = Symptom-Driven Diagnostic System for Primary Care; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; CMDQ = Common Mental Disorder Questionnaire; M-3 = My Mood Monitor; MBHS = Multidimensional Behavioural Health Screen 1.0; ADD = Anxiety and Depression Detector; DUKE-AD = Duke Anxiety-Depression Scale; PRIME-MD = Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; MHI-5 = Mental Health Index-5; CMFC = Connected Mind Fast Check; PDI-4 = Provisional Diagnostic Instrument-4.

SCID-P = Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-III-R, version P; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; SCAN = Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; MMPI-2- RF = Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured-Form; CIDI-Auto = Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Auto; CES-D = Centre of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SAI = State Anxiety Inventory; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire;, SCID-5-RV = Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-V – Research Version, ACDS = Adult ADHD Clinician Diagnostic Scale version 1.2.

1 = the diagnostic accuracy of the HADS anxiety subscale was also tested for generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder and social phobia.

2 = the CMDQ comprises two subscales, scored separately, to assess a somatic symptom disorder.

3 = the exact number of DUKE-AD items corresponding to depression and anxiety was not reported.

4 = the DUKE-AD provides an overall score for anxiety and depression, but the diagnostic accuracy was calculated separately for both disorders.

5 = the exact number of additional items used for the second screening stage of the CMFC was mostly not reported.

6 = scoring of patients’ responses is done by using a transparent overlay on the PDI-4 that shows the required frequency level for each symptom to contribute to a provisional diagnosis.

7 = to avoid over-diagnosis, the item “often” must be marked on the daily functioning Likert-scale for a provisional diagnosis of ADHD and the item “sometimes” for all other diagnoses.

= calculated manually.

Secondary outcome

The time efficiency of the index tests was assessed using the number of items and the time required for their completion by patients and their evaluation by medical staff.

Quality assessment

The QUADAS-2 [34] framework was applied to determine the quality of included studies. Using the four domains ‘patient selection’, ‘index test’, ‘reference standard’ as well as ‘flow and timing’, their risk of bias was determined. For the first three domains, concerns about applicability were additionally examined. The overall risk of bias of a study was judged as ‘low’, ‘high’, or ‘unclear’ (Table 2). Quality assessment was carried out independently by two authors (BN, KLu) and disagreements were solved through discussion.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included studies using QUADAS-2 framework.

| Study | RISK OF BIAS |

APPLICABILITY CONCERNS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PATIENT SELECTION | INDEX TEST | REFERENCE STANDARD | FLOW AND TIMING | PATIENT SELECTION | INDEX TEST | REFERENCE STANDARD | |

| Broadhead 1995 | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Bunevicius 2007 | LOW | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Christensen 2005 | HIGH | UNCLEAR | LOW | HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Gaynes 2010 | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Houston 2011 | LOW | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| McCord 2020 | LOW | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Means-Christensen 2006 | LOW | HIGH | UNCLEAR | HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Means-Christensen 2005 | LOW | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Parkerson 1996 | LOW | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Rickels 2009 | LOW | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Rogers 2021 | LOWS | UNCLEAR | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

Results

Study selection

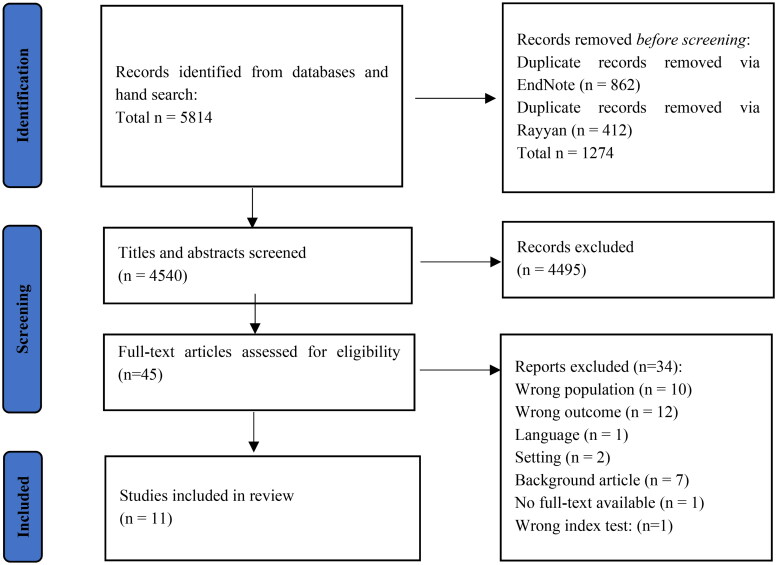

A total of 5814 studies were identified. After deduplication, the titles and abstracts of 4540 studies were screened. Of those, 45 studies remained for full-text screening. Finally, 11 studies were included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Study characteristics

Of the eleven included studies, nine studies were conducted in the USA [35–43], one in Lithuania [44] and one in Denmark [45]. The oldest study was from 1995 [35], the most recent one was published in 2021 [43]. All studies had a cross-sectional design. The sample size ranged between 166 and 1785 primary care patients (median = 388), with an overall mean age of 44.3 years.

The following 11 index tests were identified: Symptom-Driven Diagnostic System for Primary Care (SDDS-PC) [35], Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [44], Common Mental Disorder Questionnaire (CMDQ) [45], My Mood Monitor (M-3) [36], Multidimensional Behavioural Health Screen 1.0 (MBHS) [38], Anxiety and Depression Detector (ADD) [40], Duke Anxiety-Depression Scale (DUKE-AD) [41], Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) [42], Mental Health Index-5 (MHI-5) [39], Connected Mind Fast Check (CMFC) [43] and Provisional Diagnostic Instrument-4 (PDI-4) [37].

Eight of the identified index tests assess at least two mental disorders separately [35–37,39,40,43–45]. Four of those additionally [36,39,40,45] and two exclusively [41,42] provide an overall score along the spectrum of mood, anxiety and stress-related disorders. One index test [38] adopts an alternative classification of mental illness by assessing internalising, externalising and somatic/cognitive dysfunction.

A variety of reference standards was used. Psychiatric interviews were conducted in eight studies [35–37, 40, 42–45]. In the three other studies [38,39,41], validated questionnaires based on self-reports served for comparison.

Diagnostic accuracy and time efficiency of index tests

Diagnostic accuracy

Multiple-mental disorder index tests

The sensitivity and specificity scores of all identified index tests, together with their PPV and NPV are presented in Table 1.

Depression can be assessed with the SDSS-PC [35], HADS [44], CMDQ [45], M-3 [36], ADD [40], MHI-5 [39], CMFC [43] and PDI-4 [37]. Their sensitivity and specificity scores ranged from 78.0% (CMDQ) to 94.0% (CMFC, initial items) and from 61.6% (MHI-5) to 86.0% (CMDQ), respectively.

For index tests screening for any anxiety disorder (i.e. HADS [44], CMDQ [45] and M-3 [36]) sensitivity scores between 39.0% (CMDQ) and 82.0% (M-3) and specificity scores from 75.0% (HADS) to 87% (CMDQ) were found. Generalised anxiety disorder can be screened with the SDSS-PC [35], HADS [44], ADD [40], CMFC [43] and PDI-4 [37]. These index tests demonstrated sensitivity scores from 76.0% (HADS) to 100.0% (ADD) and specificity scores from 54.0% (SDSS-PC) to 75.0% (PDI-4). The presence of a panic disorder can be assessed with the SDSS-PC [35], HADS [44], ADD [40] and the MHI-5 [39], with sensitivity scores ranging from 78.3% (SDSS-PC) to 100.0% (HADS, MHI-5) and specificity scores between 65.4% (MHI-5) and 80.0% (SDSS-PC). Social phobia can be determined using the HADS [44] and the ADD [40]. The former reached a sensitivity of 95.0% and a specificity of 63.0%, while for the latter a sensitivity of 69.0% and a specificity of 76.0% were observed.

Somatic symptom disorder can be assessed by the CMDQ [45] and the CMFC [43]. The two somatisation-related sub-scales of the CMDQ showed a sensitivity of 65.0% and 74.0% and a specificity of 63.0% and 65.0%, respectively. For the initial item of the CMFC, a sensitivity of 100.0% and a specificity of 78.0% were stated.

Transdiagnostic index tests

The CMDQ [45], M-3 [36], ADD [40] and MHI-5 [39] additionally as well as the PRIME-MD [42] and the DUKE-AD [41] exclusively screen across the spectrum of mood, anxiety and stress-related disorders. With a reported sensitivity and specificity of 72.0% each, the CMDQ contains a subscale for detecting any mental disorder related to depression and anxiety. A positive screening for one of the M-3 subscales (i.e. depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder) was found with a sensitivity of 83.0% and a specificity of 76.0% to indicate the presence of at least one of those disorders. Similarly, any item of the ADD can be used as an indicator for any of the assessed mental disorders (i.e. depression, generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, post-traumatic stress disorder). The best sensitivity and specificity ratio is obtained with the panic disorder item (72.0%; 92.0%, respectively). The total score of the MHI-5 resulted in a sensitivity of 90.9% and a specificity of 57.6% to recognise a depression and/or panic disorder. For the overall score of the PRIME-MD, a sensitivity of 97.5% and a specificity of 64.5% was calculated to identify a depressive and anxious symptomatology. The diagnostic accuracy of the total score of the DUKE-AD covering both depression and anxiety was provided for both disorders separately, with sensitivity and specificity scores of 73.9% and 78.2% as well as 78.7% and 74.6%, respectively.

In contrast to the previous index tests, the MBHS [38] functions detached from the ICD and DSM to enquire mental illness. It contains a domain on internalising dysfunction (sub-scales: demoralisation, anhedonia, anxiety, suicidal tendencies), somatic/cognitive dysfunction (sub-scales: somatisation, cognitive issues) and externalising dysfunction (sub-scales: activation, disconstraint, substance misuse). The following sensitivity and specificity scores were derived: demoralisation: 73.3%/78.3%; anhedonia: 81.0%/72.4%; anxiety: 72.1%/75.4%; suicidal tendencies: 56.3%/75.2%; somatisation: 75.0%/73.0%; cognitive issues: 80.8%/83.2%; activation: 65.0%/50.3%; disconstraint: 76.7%/85.2%; substance misuse: 77.3%/82.5%.

Time efficiency

The index tests comprise between 4 and 37 items (median = 14 items). In the CMFC [43], the total number of items depends on the answers of a patient. Initially consisting of eight items, additional questions - ranging from 11 to 27 - are asked if a patient answers ‘yes’ to any of the eight questions.

The HADS [44], CMDQ [45], M-3 [36], MBHS [38], PRIME-MD [42] and MHI-5 [39] were reported to take less than 5 minutes to complete. The completion time of the CMFC [43] depends on the number of positively answered items in the first screening stage.

A timeframe of less than one minute was specified to evaluate the results for the CMDQ [45], M-3 [36], MBHS [38] and MHI-5 [39]. For the CMFC [43], the evaluation is carried out automatically as part of its digital application (Table 1).

Quality assessment

The quality of the eleven identified studies varied in terms of risk of bias. Only two studies were judged as ‘low’ on all domains [35,36] (Table 2).

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to identify multiple-mental disorder and transdiagnostic index tests used in primary care. As outcomes, diagnostic accuracy and time efficiency were assessed. Eleven index tests were identified. Most had a sensitivity and specificity above 70% for correctly identifying a depression, any or a specific anxiety disorder or a somatic symptom disorder. This is comparable to the diagnostic accuracy reported for other commonly used screening tools in primary care, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Generalised Anxiety Disorder Screener-7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) [46]. The index tests tended to have a lower specificity than sensitivity. Although acceptable for screening tools [47], the associated risk of misclassifying patients as positive cases [33] could lead to unnecessary stigmatisation [16] and increased workload for GPs [36]. It should be considered, however, that the results of index tests require confirmation by thorough testing using diagnostic tools [36,39,42,44]. A minority of index tests were reported to have a PPV below 10% (i.e. SDSS-PC [35], HADS [44], MHI-5 [39]). One reason could be the lower pre-test probability of mental illness in primary care. Compared with the psychiatric setting, primary care patients usually have not undergone any diagnostic pre-selection, reducing the likelihood that patients tested as positive actually have the disorder [48].

Regarding time efficiency, half of the index tests contain fewer than 14 items. With a maximum completion time of 5 minutes, these index tests can be considered short [49]. Notably, even studies of index tests with more than 14 items did not report a completion time above 5 minutes and an evaluation time exceeding one minute. Given the average primary care consultation time of less than 10 minutes per patient [10], all index tests appear to be administrable. Particularly feasible may be those index tests that take less than 3 minutes to complete [47].

To screen for multiple-mental disorders, the CMFC [43] may be the most promising index test for GPs. It covers a broad range of common mental disorders, i.e. depression, anxiety, somatoform disorder, substance abuse and ADHD [11,50]. In comparison - except of the CMDQ [45] - all other multiple-mental disorder index tests are limited by not including items on somatoform disorders [15,51]. Further, its computerised two-step diagnostic process enables a quick identification of distressed patients, followed by a more in-depth diagnostic investigation of those who screen positive. This may enhance diagnostic accuracy.

Suitable as overall markers for mental illness may be index tests that assess psychopathology dimensionally rather than categorically using a transdiagnostic approach [17]. The CMDQ [45], M-3 [36], MHI-5 [39], ADD [40], PRIME-MD [42] and DUKE-AD [41] each provide a subscale or total score to examine symptoms along the spectrum of mood, anxiety and stress-related disorders. Mostly, sensitivity and specificity scores above 70% was found. By examining a psychopathological spectrum but without neglecting the diagnostic criteria of conventional taxonomies, these index tests can be considered as ‘soft’ transdiagnostic index tests [20]. Overall, transdiagnostic index tests may be more compatible with common screening procedures in primary care, i.e. assessing patients’ mental health condition based on the general impression of GPs rather than on distinct diagnostic criteria [12]. However, the identified soft transdiagnostic index tests may be limited by their heterogeneous scope of psychopathology, e.g. PRIME-MD [42]: anxiety and depression-related pattern; M-3 [36]: dimension of depression, anxiety, bipolar and post-traumatic stress disorder. Consequently, GPs have to decide which screening scope is the best fit for their patients’ symptomatic profile.

The MBHS [38] might be a more practical approach to transdiagnostic screening for GPs. By assessing internalising, somatic/cognitive and externalising dysfunction, the MBHS functions detached from conventional diagnostic classifications and can therefore be labelled as a ‘hard’ transdiagnostic index test [20]. GPs may use the higher-order domains of dysfunction to anticipate a broad range of lower-order mental health problems in their patients (e.g. depression, anxiety, somatoform, substance abuse and ADHD-related symptoms). This approach is similar to other hierarchical taxonomies of psychopathology, such as the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) [52] and the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) [53]. Notably, the theoretical basis of the MBHS, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) [54], suggests another possibility for screening in primary care, i.e. the assessment of maladaptive personality traits and dysfunction. Similar to domains of psychopathological dysfunction, personality traits such as negative affectivity may serve as vulnerability markers of mental illness [55–58].

A functional bridge between higher-order domains of dysfunction and lower-order domains of mental health problems could be established by transdiagnostic factors [59]. Although included in the search strategy, no index tests specifically targeting transdiagnostic factors (e.g. emotion-based avoidance [60,61]) were identified. This indicates an additional area for further research. There is a growing number of transdiagnostic factors [22], many of which overlap in their conceptualisation [62]. Thus, index tests screening for the spectrum of mood, anxiety and stress-related disorders and those targeting transdiagnostic factors should cover broad and meaningful symptoms or mechanisms, e.g. underlying emotion-based disorders [23–25]. Otherwise, transdiagnostic index tests might not offer a substantial benefit to GPs compared to a conventional classification of mental disorders [5,8,12].

Strengths and limitations

This review is the first to systematically search for multiple-mental disorder and transdiagnostic index tests used in primary care, providing a comprehensive overview of the diagnostic scope, diagnostic accuracy and time efficiency of the index tests. Some limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the validity and reliability of the index tests were not investigated in detail. Second, the included studies were cross-sectional in design, had rather small sample sizes, collected data in only one or a few primary care practices and used heterogeneous reference standards. Third, the strict inclusion criteria may have excluded potentially valuable studies that, for example, targeted a different setting [63,64] or did not provide data on diagnostic accuracy [65]. Lastly, all but four of the studies [36–38,43] were published before 2010, which may affect the relevance of the index tests for current practice.

Conclusion

Eleven index tests were identified that take a multiple-mental disorder and/or transdiagnostic approach to screen for mental illness in primary care. All index tests were found to be time efficient and mostly offer a satisfactory diagnostic accuracy. The CMFC [43] may be the most promising multiple-mental disorder index test. Among transdiagnostic index tests, the MBHS [38] can be regarded as an appropriate tool. Future research should focus on screening tools that target transdiagnostic factors or maladaptive personality traits as informative constructs for identifying mental illness in primary care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The POKAL-Group (PrädiktOren und Klinische Ergebnisse bei depressiven ErkrAnkungen in der hausärztLichen Versorgung [POKAL, DFG-GrK 2621]) consists of the following investigators: Markus Bühner, Tobias Dreischulte, Peter Falkai, Jochen Gensichen, Peter Henningsen, Caroline Jung-Sievers, Helmut Krcmar, Kirsten Lochbühler, Karoline Lukaschek, Gabriele Pitschel-Walz, Barbara Prommegger, Andrea Schmitt and Antonius Schneider. The following doctoral students are members of the POKAL-Group: Katharina Biersack, Vita Brisnik, Christopher Ebert, Julia Eder, Feyza Gökce, Carolin Haas, Lisa Pfeiffer, Lukas Kaupe, Jonas Raub, Philipp Reindl-Spanner, Hannah Schillok, Petra Schönweger, Clara Teusen, Marie Vogel, Victoria von Schrottenberg, Jochen Vukas and Puya Younesi.

Funding Statement

Research reported in this publication was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG-GrK 2621/POKAL-Kolleg) and endorsed by the German Centre for Mental Health (Deutsches Zentrum für Psychische Gesundheit [DZPG], grant: 01EE2303A).

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are not publicly available due to licencing restrictions. However, data are available upon reasonable request. Data requests may be directed at “Stiftung Allgemeinmedizin – The Primary Health Care Foundation” (www.stiftung-allgemeinmedizin.de). Mail: office@stiftung-allgemeinmedizin.de

References

- 1.Santomauro DF, Mantilla Herrera AM, Shadid J, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Commission . Mental health – Report; 2023. internet]: Publications Office of the European Union; [01 Aug 2024]. Available from: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2875/48999.

- 3.Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Häfner S, Petzold ER.. The role of primary care practitioners in psychosocial care in Germany. Perm J. 2007;11(1):52–55. doi: 10.7812/TPP/06-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective; 2008. [28 Oct 2023]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241563680.

- 6.WHO . Mental health in primary care: illusion or inclusion?; 2018. [27 Oct 2023]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.38.

- 7.Bower P, Knowles S, Coventry PA, et al. Counselling for mental health and psychosocial problems in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011(9):Cd001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown JD, Wissow LS.. Rethinking the mental health treatment skills of primary care staff: a framework for training and research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39(6):489–502. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinnema H, Terluin B, Volker D, et al. Factors contributing to the recognition of anxiety and depression in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0784-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irving G, Neves AL, Dambha-Miller H, et al. International variations in primary care physician consultation time: a systematic review of 67 countries. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e017902. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roca M, Gili M, Garcia-Garcia M, et al. Prevalence and comorbidity of common mental disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2009;119(1-3):52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanel G, Henningsen P, Herzog W, et al. Depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders: vague or distinct categories in primary care? Results from a large cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(3):189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talen MR, Baumer JG, Mann MM.. Screening measures in integrated behavioral health and primary care settings. In: Talen MR, Burke Valeras A, editors. Integrated behavioral health in primary care: evaluating the evidence, identifying the essentials. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013. p. 239–272. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulvaney-Day N, Marshall T, Downey Piscopo K, et al. Screening for behavioral health conditions in primary care settings: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(3):335–346. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4181-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mergl R, Seidscheck I, Allgaier AK, et al. Depressive, anxiety, and somatoform disorders in primary care: prevalence and recognition. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(3):185–195. doi: 10.1002/da.20192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linden M. Mental disorders in primary care. Adv Psychosom Med. 2004;26:52–65. doi: 10.1159/000079760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fusar-Poli P, Solmi M, Brondino N, et al. Transdiagnostic psychiatry: a systematic review. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):192–207. doi: 10.1002/wps.20631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organisation (WHO) . International classification of diseases, eleventh revision (ICD-11); 2019/2021 [13th Jul 2024]. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse11.

- 19.American Psychiatric Association (APA) . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalgleish T, Black M, Johnston D, et al. Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: current status and future directions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2020;88(3):179–195. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansell W, Harvey A, Watkins ER, et al. Cognitive behavioral processes across psychological disorders: a review of the utility and validity of the transdiagnostic approach. J Cogn Ther. 2008;1(3):181–191. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2008.1.3.181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaeuffele C, Schulz A, Knaevelsrud C, et al. CBT at the crossroads: the rise of transdiagnostic treatments. J Cogn Ther. 2021;14(1):86–113. doi: 10.1007/s41811-020-00095-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hazzard VM, Mason TB, Smith KE, et al. Identifying transdiagnostically relevant risk and protective factors for internalizing psychopathology: an umbrella review of longitudinal meta-analyses. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;158:231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antuña-Camblor C, Peris-Baquero Ó, Juarros-Basterretxea J, et al. Transdiagnostic risk factors of emotional disorders in adults: a systematic review. An Psicol. 2024;40(2):199–218. doi: 10.6018/analesps.561051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bullis JR, Boettcher H, Sauer-Zavala S, et al. What is an emotional disorder? A transdiagnostic mechanistic definition with implications for assessment, treatment, and prevention. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2019;26(2):e12278. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cano-Vindel A, Muñoz-Navarro R, Moriana JA, et al. Transdiagnostic group cognitive behavioural therapy for emotional disorders in primary care: the results of the PsicAP randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2021;52(15):1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timulak L, Richards D, Bhandal-Griffin L, et al. Effectiveness of the internet-based Unified Protocol transdiagnostic intervention for the treatment of depression, anxiety and related disorders in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2022;23(1):721. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06551-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barlow DH, Curreri AJ, Woodard LS.. Neuroticism and disorders of emotion: a new synthesis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2021;30(5):410–417. doi: 10.1177/09637214211030253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neulinger B, Lukaschek K, Lochbühler K, et al. Transdiagnostic screening tools for use in primary care: a systematic review [internet]: PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews; 2022. [01 Aug 2024]. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022382572.

- 31.The EndNote Team . EndNote [computer program] [64 bit]. EndNote X9. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monaghan TF, Rahman SN, Agudelo CW, et al. Foundational statistical principles in medical research: sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(5):1–7. doi: 10.3390/medicina57050503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Broadhead WE, Leon AC, Weissman MM, et al. Development and validation of the SDDS-PC screen for multiple mental disorders in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4(3):211–219. doi: 10.1001/archfami.4.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaynes BN, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Weir S, et al. Feasibility and diagnostic validity of the M-3 checklist: a brief, self-rated screen for depressive, bipolar, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorders in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(2):160–169. doi: 10.1370/afm.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Houston JP, Kroenke K, Faries DE, et al. A provisional screening instrument for four common mental disorders in adult primary care patients. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCord DM. The multidimensional behavioral health screen 1.0: a translational tool for primary medical care. J Pers Assess. 2020;102(2):164–174. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2019.1683019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Means-Christensen AJ, Arnau RC, Tonidandel AM, et al. An efficient method of identifying major depression and panic disorder in primary care. J Behav Med. 2005;28(6):565–572. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Means-Christensen AJ, Sherbourne CD, Roy-Byrne PP, et al. Using five questions to screen for five common mental disorders in primary care: diagnostic accuracy of the Anxiety and Depression Detector. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(2):108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parkerson GR, Broadhead WE, Tse CK.. Anxiety and depressive symptom identification using the Duke Health Profile. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rickels MR, Khalid-Khan S, Gallop R, et al. Assessment of anxiety and depression in primary care: value of a four-item questionnaire. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109(4):216–219. Apr [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers R, Hartigan SE, Sanders CE.. Identifying mental disorders in primary care: diagnostic accuracy of the connected mind fast check (CMFC) electronic screen. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2021;28(4):882–896. doi: 10.1007/s10880-021-09820-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bunevicius A, Peceliuniene J, Mickuviene N, et al. Screening for depression and anxiety disorders in primary care patients. Depress. Anxiety. 2007;24(7):455–460. doi: 10.1002/da.20274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christensen KS, Fink P, Toft T, et al. A brief case-finding questionnaire for common mental disorders: the CMDQ. Fam Pract. 2005;22(4):448–457. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Byrd MR, Alschuler KN.. Behavioral screening in adult primary care. The primary care toolkit: Practical resources for the integrated behavioral care provider. New York, NY, US: Springer Publishing Company; 2009. p. 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider A, Dinant GJ, Szecsenyi J. [Stepwise diagnostic workup in general practice as a consequence of the Bayesian reasoning. ]. Z Arztl Fortbild Qualitatssich. 2006;100(2):121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchell AJ, Coyne JC.. Do ultra-short screening instruments accurately detect depression in primary care? A pooled analysis and meta-analysis of 22 studies. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(535):144–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sundquist J, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K, et al. Common adult psychiatric disorders in Swedish primary care where most mental health patients are treated. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):235. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1381-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gates K, Petterson S, Wingrove P, et al. You can’t treat what you don’t diagnose: An analysis of the recognition of somatic presentations of depression and anxiety in primary care. Fam Syst Health. 2016;34(4):317–329. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, et al. The hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. J Abnorm Psychol. 2017;126(4):454–477. doi: 10.1037/abn0000258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ben-Porath Y, Tellegen A.. Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory-2-restructured form (MMPI-2-RF) [database record]. [place unknown]: APA PsycTests; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fowler JC, Lamkin J, Allen JG, et al. Personality trait domains predict psychiatric symptom and functional outcomes. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2022;59(1):38–47. doi: 10.1037/pst0000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kerber A, Schultze M, Müller S, et al. Development of a short and ICD-11 compatible measure for DSM-5 maladaptive personality traits using ant colony optimization algorithms. Assessment. 2022;29(3):467–487. doi: 10.1177/1073191120971848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rek K, Kerber A, Kemper C, et al. Getting the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 ready for clinical practice: norm values and correlates in a representative sample from the German population. ; 2021.

- 58.Böhnke JR, Lutz W, Delgadillo J.. Negative affectivity as a transdiagnostic factor in patients with common mental disorders. J Affect Disord. 2014;166:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sauer-Zavala S, Southward MW, Semcho SA.. Integrating and differentiating personality and psychopathology in cognitive behavioral therapy. J Pers. 2022;90(1):89–102. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akbari M, Seydavi M, Hosseini ZS, et al. Experiential avoidance in depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive related, and posttraumatic stress disorders: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2022;24:65–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2022.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spinhoven P, Drost J, de Rooij M, et al. A longitudinal study of experiential avoidance in emotional disorders. Behav Ther. 2014;45(6):840–850. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schaeuffele C, Bär J, Buengener I, et al. Transdiagnostic processes as mediators of change in an internet-delivered intervention based on the unified protocol. Cogn Ther Res. 2022;46(2):273–286. doi: 10.1007/s10608-021-10272-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fink P, Ørbøl E, Hansen MS, et al. Detecting mental disorders in general hospitals by the SCL-8 scale. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(3):371–375. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kleinstäuber M, Exner A, Lambert MJ, et al. Validation of the Four-Dimensional Symptom Questionnaire (4DSQ) in a mental health setting. Psychol Health Med. 2021;26(sup1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1883685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hickie IB, Davenport TA, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Development of a simple screening tool for common mental disorders in general practice. Med J Aust. 2001;175(S1):S10–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are not publicly available due to licencing restrictions. However, data are available upon reasonable request. Data requests may be directed at “Stiftung Allgemeinmedizin – The Primary Health Care Foundation” (www.stiftung-allgemeinmedizin.de). Mail: office@stiftung-allgemeinmedizin.de