Abstract

Background: Facial gender-affirming surgery (FGAS), one of many transition-related surgeries (TRSs), “feminizes” the faces of transgender and gender diverse (TGD) patients undergoing transition. However, it is difficult to demonstrate the medical necessity of FGAS in terms of postoperative quality of life (QoL) outcomes due to a lack of standardized assessment tools. Thus, FGAS remains largely unsubsidized in North America.

Methods: A systematic review of online databases was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines. Screening and quality assessment was conducted by two independent blinded reviewers (KJ and GR). For statistical analysis, data from different Likert-scale-like questionnaires were extracted and coalesced into three-point scales on a data table of seven QoL domains; “Pre-” and “Postoperative femininity,” “Psychological satisfaction,” “Social Integration and Functioning,” “Aesthetic Satisfaction,” “Physical Health,” and “Satisfaction with Surgical Results.”

Results: From 2000 to 2022, 1837 patients and 3886 procedures from 19 studies were included. Weighted averages across all QoL domains reflected statistically significant improvement compared to neutral following FGAS (p < 0.001). Three studies used the same questionnaire, which showed that out of all eight questions regarding facial appearance, FGAS patients most strongly agreed the surgery was important to their ability to live as a woman (mean = 4.56/5, n = 137). Secondary outcomes showed the most common complications were hardware palpability (3.45%, n = 145) and aberrant scarring (2.17%, n = 423) with an overall revision rate of 2.17% (n = 423). The most common procedure was fronto-orbital remodeling.

Conclusion: FGAS significantly improves QoL with minimal risk to life and supports the literature in defining FGAS as a medically necessary procedure comparable to other TRSs.

Keywords: Craniofacial, facial feminization surgery, gender affirmation surgery, plastic surgery, transgender

Background

The face is the foundation for social impressions and is a core element of an individual’s identity in our society. As such, transgender individuals’ transitions may involve changing their facial appearance to better outwardly express the gender congruent with their internal identity. This can be achieved through hormone therapy, injectables, and/or surgical interventions. Facial gender-affirming surgery (FGAS) is an overarching term to describe surgical procedures used to feminize the faces of transgender women and trans-feminine or gender diverse patients (Altman, 2012). FGAS dates back to the 1980s and was popularized by Dr. Douglas Ousterhout (Altman, 2012). Recently, FGAS has been gaining popularity, and that has been mirrored by the increase in internet search terms (Chaya et al., 2021).

Gender dysphoria is defined by an incongruence between a person’s sex assigned at birth and gender identity, which can impact a person’s day-to-day functioning and is common amongst transgender patients (Chaya et al., 2021). One of the primary goals of performing facial feminization surgery is to allow patients to experience gender euphoria, or a state of satisfaction, comfort, and/or confidence as a result of having one’s gender affirmed. However, in the United States and Canada, few insurance companies and only two Canadian provinces and territories offer coverage for FGAS; Nunavut and Yukon (Gadkaree et al., 2021; Mertz, 2022). Consequently, many patients are left with the choice between doing without or paying out of pocket. It has also been reported that lack of access to covered care may lead patients to seek procedures from nonaccredited providers, which can pose a serious safety risk to such patients (Berli et al., 2017).

FGAS procedures are chosen based on which areas of the face make patients feel most dysphoric and most commonly address the scalp, forehead, eyebrows, nose, mandible, and chin (Morrison et al., 2020). The goal of FGAS is to feminize the face to help align a patient’s external traits with their gender identity (Chou, Tejani, Kleinberger, & Shih, 2020). FGAS has been shown to have a significant improvement on one’s perception of their own femininity and how other people perceive them as feminine (Gupta, White, Trott, & Spiegel, 2022).

There is currently a debate as to whether FGAS should be considered “medically necessary” or purely esthetic (Dubov & Fraenkel, 2018). The procedures remain uncovered by many insurance policies, including the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) and the Régis de l’assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ), leaving women and trans-feminine individuals with the choice between doing without or paying out of pocket. The cost of FGAS varies, but can cost up to $40,000 for a full-face one stage surgery uninsured patients (Hu et al., 2021).

Several studies have demonstrated improvement in patient satisfaction, perception of femininity, and mental health after undergoing FGAS (Morrison et al., 2020). However, to date, there is no standardized tool used to assess the quality of life (QoL) for patients who undergo FGAS (Morrison, Crowe, & Wilson, 2017). The aim of this systematic review was to ascertain whether FGAS improves a patient’s QoL regardless of the measure used to assess QoL.

Methods

Search strategy

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline was used (Table 1). The search strategy was designed by KJ. The search strategy included search terms related to FGAS and terms related to the primary outcome, QoL. The full search strategy, including the terms used, can be seen in (Table 1).

Table 1.

A Table of the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the literature search.

| Parameters | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Journal characteristics | Prospective Retrospective Peer Reviewed English Published in any year Any country of origin |

Editorial, Case Report, Abstract, Presentation, Poster, Book Chapter, Opinion articles, Commentaries, Review articles (systematic & narrative) Non-Peer Reviewed Non-English or French |

| Sample characteristics | Human N > 1 Patient is transgender |

Non-human Not facial feminization surgery Patient is cisgender |

| Methods | Facial feminization surgery (any procedure) | Revision surgery Gender affirming surgery of any region other than the face Non-surgical modalities |

| Outcomes | Reports quality of life (validated and non-validated tools) | Does not report quality of life |

| Search Term | ((“face femin* surgery” OR “facial femin* surgery” OR “craniofacial femin* surgery”) OR ((face or facial or craniofacial) AND (“gender affirm* surgery” OR “gender confirm* surgery” OR “gender reassign* surgery”))) AND (“quality of life” OR “quality-of-life” OR QoL OR “health related quality of life” OR “health-related quality of life” OR HRQOL OR “FACE-Q” OR FACEQ OR “shortform” or “short form” OR euroqol* OR eq5d OR "eq 5d" OR hql or hqol OR “quality of wellbeing” OR “quality of well-being” OR qowb OR qwb OR hye or hyes OR Likert OR satisfaction OR SHS OR “happ* scale” OR “subjective happ*” OR “questionnaire” OR “quality adjusted life” OR “quality-adjusted life” OR “disutil*” OR rosser OR QESFF1) | |

Six bibliographic databases were searched: PubMed®, Cochrane Library®, Ovid®, Web of Science®, CINAHL®, and Scopus®. The search was conducted on June 19, 2022. References were manually screened by two independent reviewers (KJ and GR) from relevant review articles to identify if there were any studies that were not captured in the initial search. However, no additional sources were identified in this process.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined a priori. Prospective studies, retrospective studies, and randomized controlled trials written in English or French and published in peer-reviewed journals from the date of the search reporting on patient-reported QoL outcomes were included. Studies reporting pre- versus postoperative femininity as perceived by someone other than the patient themself were excluded from this analysis. While the primary goal of FGAS in the past was “passing,” or otherwise being seen as cisgender by third-party observers, there has been a paradigm shift in recent years toward privileging the internal perspective of one’s appearance over the outward gaze. Therefore, we tailored the scope of this research to assess subjects’ internal perspective of one’s own external appearance. All studies had to include separate QoL data for transgender women. Patients undergoing revision surgery were excluded because their reason for revision may skew their scores. Single case reports, reviews, animal studies, conference proceedings, abstracts, inaccessible manuscripts, and editorials were excluded (Table 1).

Study selection

The studies were extracted, analyzed, and duplicates were eliminated. Screening was conducted by two independent reviewers (KJ and GR) using Rayyan platform (Rayyan Systems Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA). For the primary screen, titles and abstracts were reviewed. Selected articles underwent full-text review for the secondary screening. The Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) score was used to assess the quality of all articles selected for the review and meta-analysis. Papers that failed to achieve a benchmark score of 60% or higher were excluded.

Data extraction

The two independent reviewers (KJ and GR) extracted data using the Google Sheet platform (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA). Any possible errors were reviewed and discussed to ensure correctness. Study type, number of patients, average age, type of FGAS, augmentation, pre-and post-operative QoL data, and common complication rates were extracted. Attempts were made to contact the authors of any study with incomplete QoL data or that mentioned conducting QoL assessments without reporting corresponding data in their paper.

Due to the lack of any standardized postoperative patient evaluation system for FGAS, part of the data extraction process entailed coalescing responses from different questionnaires into one cohesive data table for statistical analysis. This integration was possible due to the Likert-scale nature of the studies’ questionnaires. This data table consisted of seven domains to encompass the common themes among the information collected by the different questionnaires.

The seven domains are defined as follows:

(A1 and A2) Pre- and Postoperative Femininity; “One’s own perception of one’s image that it is congruent with one’s identity as a female or feminine non-binary person,”

(B) Psychological Satisfaction; “One’s own satisfaction with one’s current feelings and mental state such that it is similar to the baseline of the general population. This definition includes reduction of gender dysphoria and excludes depression and anxiety screening which are deferred for narrative review,”

(C) Social Integration and Functioning; “How one feels in social situations and one’s perception of others’ reactions and treatment in public,”

(D) Esthetic Satisfaction; “Satisfaction with one’s attractiveness such that one would be considered ‘beautiful’,”

(E) Physical Health; “One’s physical wellbeing, ability to function pain-free in day-to-day tasks,”

(F) Satisfaction with Surgical Results; “Satisfaction with how the surgery successfully altered their physical appearance.”

Where possible, KJ and GR extracted the individual questions from the questionnaires, and the two reviewers independently sorted applicable questions to match aforementioned domains, excluding any questions that were irrelevant (e.g. quality of voice following chondrolaryngoplasty) or had undifferentiated response data (e.g. only a total mean score was reported instead of the mean score for each question, or for each Likert-scale tier). Therefore, some questionnaires were integrated in full, while others were integrated in part. Moreover, some questionnaires contributed data to all seven domains, while others contributed only to some or exclusively to one. The specific questionnaires integrated for statistical analysis as such are SF36v2, FACE-Q, Facial Feminization Patient Questionnaire (FFPQ), QESFF1, Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), Glasgow Benefit Inventory (GBI), and five original questionnaires.

Data analysis

Given the widely ranging heterogeneity among QoL scales currently used in the FFS literature, the authors sought to converge them in order to permit a reasonable data analysis. All 5-point scales were converted to a 3-point scale (from 0 to 2). In this simplified scale, 0 reflects below-average satisfaction or a worse outcome, 1 reflects a neutral outcome, and 2 reflects a satisfactory outcome or improvement. Meaning, more specifically, a score greater than 1.0 would indicate a degree of improvement, with 2.0 being 100% improvement, and any score less than 1.0 means a negative or worse result with 0.0 being the worst possible outcome. A score of 1.0, therefore, would reflect no change compared to the preoperative status. In addition, if responses were given as a function of percentages of each level on a Likert scale, the average value was calculated and translated into the closest round number on a 3-point scale.

In order to determine the effect of FFS on the QoL domains, a one-sample T-test was computed, using each category’s weighted average compared to the baseline neutral value: 1. In addition, an unpaired t-test was performed comparing pre- and postoperative femininity perception. For the three papers that utilized the FFPQ, weighted averages were computed. Finally, the secondary outcomes, or complications, were also analyzed by means of weighted averages. Statistical significance was set as p ≤ 0.05, and all statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS Version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y.).

Results

Study characteristics

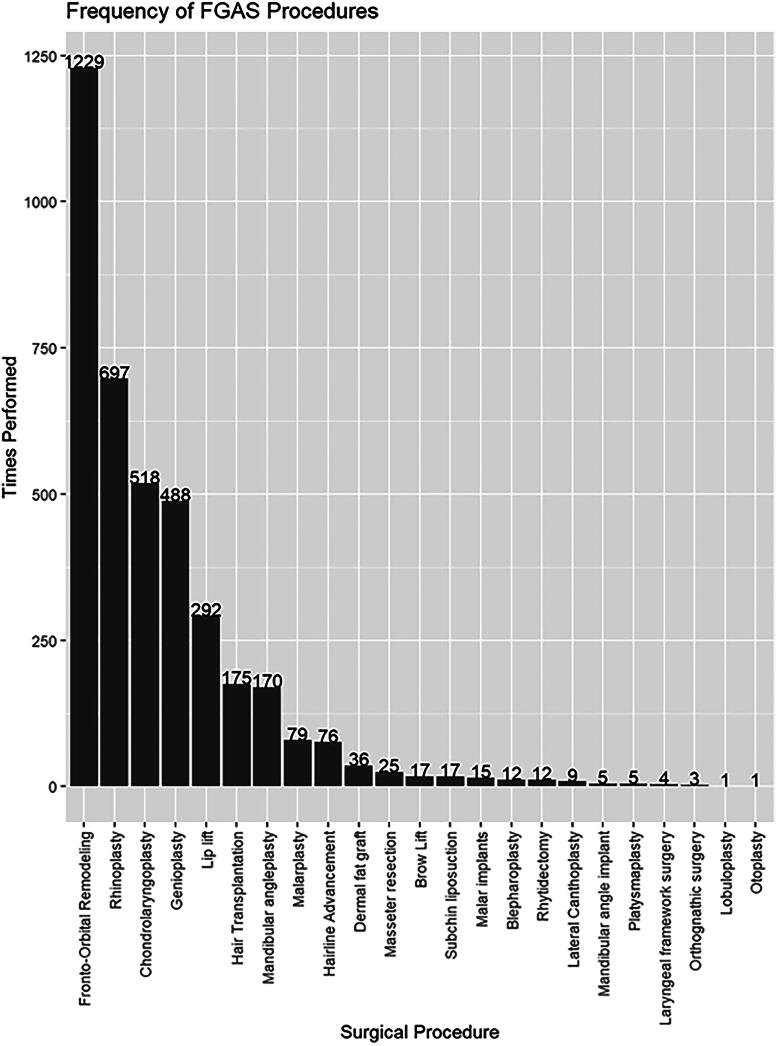

The search strategy identified a total of 1439 articles. After duplicates were removed, a total of 867 articles were screened using title and abstract. A total of 58 articles were selected for full-text review. Nineteen fit the inclusion criteria and were deemed suitable by both reviewers for data extraction (Table 2). All studies included received a MINORS Score of 60% or higher. A total of 19 studies were included in our systematic review, accounting for 1837 total patients. Their mean age was 38.6 ± 3.9 years (n = 1599) and their mean BMI was 26.0 ± 1.1 kg/m2 (n = 123). On average, 89.1% (n = 978/1098) of patients were on hormones and 17.0% (n = 174/1023) were smokers. Four patients (0.2%) identified as non-binary, while the rest identified as female. The three most common surgeries performed included fronto-orbital remodeling, rhinoplasty, and chondrolaryngoplasty (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Study characteristics & QoL assessment.

| Study | Location | Journal | No. Patients | Data collection period | Follow up period | Type of FFS | QoL assessment tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ainsworth & Spiegel, 2010 | USA | Quality of Life Research | 75 | 2007 | – | – | SF36v2 |

| Daurade et al., 2022 | France | Journal of Stomatology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | 21 | 2017–2019 | 6 months | Mandibular angle resection | 8 Item Questionnaire |

| Ganry & Cömert, 2022 | France | The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery | 16 | 2018–2020 | 6 months | Frontal sinus anterior wall setback, Frontal and zygomatic milling, Hairline advancement, Rhinoseptoplasty, Lateral canthoplasty, Blepharoplasty, Zygomatic osteotomy, Genioplasty, Mandibular angles surgery, Masseteric muscle resection, Upper lip lift, MASK lift, MACS lift, Lipofilling, Reduction Chondrolaryngoplasty, Orthognatic surgery | FACE-Q |

| Tawa et al., 2021 | France | Esthetic Surgery Journal | 45 | 2018–2019 | 6 months | Forehead impaction Mandibular angle reduction, Genioplasty | 6 Item Questionnaire |

| Morrison et al., 2020 | USA | Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery | 66 | – | 6 months | Brow reduction, Genioplasty, Rhinoplasty, Mandibular contouring, Hair transplant, Lip lift, Thyroid cartilage reduction, Brow lift, Hairline lowering, Upper/lower lid blepharoplasty, Dermal fat graft/lobuloplasty/midface lift/otoplasty | FFS Outcome & FFS Satisfaction |

| Raffaini, Perello, Tremolada, & Agostini, 2019 | Italy | The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery | 9 | 2003–2017 | 15 months | Mandibular reshaping, Thyroid cartilage chondroplasty, forehead orbital remodeling, rhinoplasaty | ANA Scale Self Evaluation |

| La Padula et al., 2019 | France | Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive, & Esthetic Surgery | 25 | 2015–2018 | 1 year | Frontal bone grinding, hairline advancement, rhinoplasty, malar implants, malar valgus osteotomy, facial lipofilling, grinding of the angles and mandibular rims, reduction of the masseter, angle implants, upper lip lifting, orthognathic surgery, genioplasy, subchin liposuction, reduction laryngoplasty | SWLS, SHS |

| van de Grift, Elaut, Cerwenka, Cohen-Kettenis, & Kreukels, 2018 | Netherlands | Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy | 7 | 2013–2014 | – | – | SWLS, SHS, UGDS, Symptoms Checklist-90 |

| Bellinga, Capitán, Simon, & Tenório, 2017 | Spain | JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery | 200 | 2010–2015 | 12 months | Rhinoplasty, Forehead reconstruction, Lip lift | 5 Item Questionnaire |

| Khafif, Shoffel-Havakuk, Yaish, Tordjman, & Assadi, 2020 | Israel | Facial Plastic Surgery & Esthetic Medicine | 4 | 2019 | 1–2 months | Chondrolaryngoplasty | 7 Item Questionnaire |

| Verbruggen, Weigert, Corre, Casoli, & Bondaz, 2018 | France | Annales de chirurgie plastique esthétique | 18 | 2017 | – | Fronto-orbital remodeling, Rhinoplasty, Malar implants, Upper lip lift, Remodeling of the mandibular angles, Genioplasty, Chondrolaryngoplasty | QESFF1 |

| Isung, Möllermark, Farnebo, & Lundgren, 2017 | Sweden | Archives of Sexual Behavior | 10 | 2015 | 6 months | TCS, AC subscale, GIA subscale, BIS total BIS head adn neck, HAD-D, HAD-A, SDS, EQ-5D | |

| Noureai, Randhawa, Andrews, & Saleh, 2007 | England | Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery | 12 | 1998–2004 | 1 year | Nasal feminization | Reported in results |

| Chou et al., 2022 | USA | Facial Plastic Surgery & Esthetic Medicine | 107 | 2017–2019 | 3 months | – | Pre and Post op FFS Outcome Evaluation |

| Simon et al., 2022 | Spain | Plastic & Reconstructive Journal | 837 | 2010–2019 | 12 months | Jaw and/or chin contouring, Forehead reconstruction, Hair transplantation, Rhinoplasty, Malarplasty, Lip lift, Adam’s apple contouring | 6 Item Questionnaire |

| Tang, 2020 | USA | The Layngoscope | 91 | 2016–2020 | 1 year | Laryngochondroplasty | GBI |

| Capitán, Simon, Kaye, & Tenorio, 2014 | Spain | Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery | 172 | 2008–2012 | 6 months | Forehead feminization | 5 Item Questionnaire |

| Davison, Clifton, Futrell, Priore, & Manders, 2000 | USA | Esthetic Plastic Surgery | 22 | – | – | Tracheal shave, Eleventh/twelfth rib resection, Rhytidectomy/platysmaplasty, Brow lift/blepharoplasty, Rhinoplasty, Laryngeal framework, Lip/cheek augmentation surgery | Reported in results |

| Bonapace-Potvin et al., 2023 | Canada | Esthetic Plastic Surgery | 100 | 2010–2021 | 6 months | Rhinoplasty, Scalp advancement, Laryngochondroplasty, V-line mandible reduction, Genioplasty, Lip lif, Malar implant | Reported in results |

Figure 1.

A Tabulation of all FFS surgeries performed across the studies enrolled in this review with the most frequently performed procedures toward the left. The x-axis shows the name of the procedure and the y-axis as well as bar labels show the number of times each was performed.

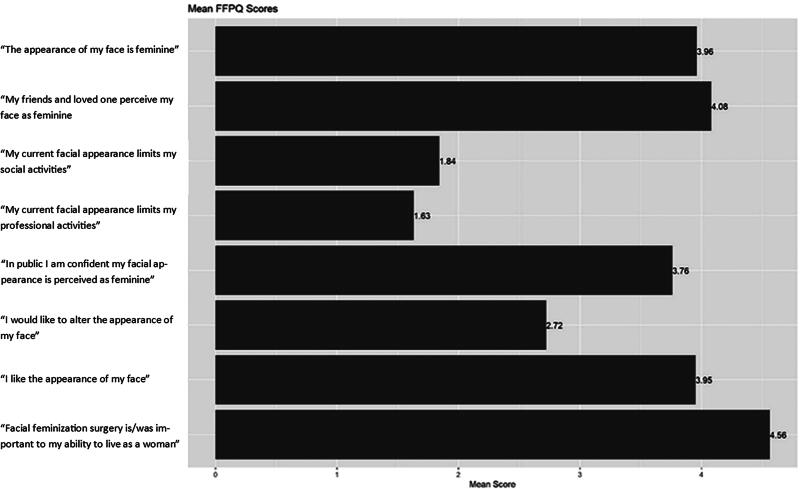

Data analysis

In terms of the seven pre-determined QoL categories, all were deemed to be significantly different (p < 0.001) from the neutral value: 1 (Table 3). In addition, the improvement between pre- and postoperative femininity perception was statistically significant (p < 0.001). In terms of the studies which utilized the FFPQ, postoperative patients seemed to most strongly agree with the fact that FFS was important to their ability to live as a woman (mean = 4.56/5, n = 137) (Figure 2). Finally, in terms of secondary outcomes or complications, hardware palpability (3.45%, n = 145) and aberrant scarring (2.17%, n = 423) were the most common complications with an overall mean revision rate of 2.17% (n = 423) (Table 4).

Table 3.

A Table showing the mean score per each of seven predefined quality of life domains (see Methods).

| n | Mean Score (0–2) | Weighted SD | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-op femininity perception | 1037 | 0.94 | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| Post-op femininity perception | 1287 | 1.56 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Psychological satisfaction | 184 | 1.47 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Social integration | 250 | 1.52 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Esthetic satisfaction | 175 | 1.62 | 0.36 | <0.001 |

| Physical health | 194 | 1.30 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with surgical results | 1598 | 1.61 | 0.18 | <0.001 |

A two-point scale is used with zero being the most negative response, and two being the most positive response. p-values were calculated from t-tests comparing each mean score to the neutral score of one. A p-value less than 0.05 is considered significant. The total number of datapoints (n) and weighted standard deviation (SD) are also shown.

Figure 2.

A Figure displaying the average score across three studies using the same questionnaire: the Facial Feminization Patient Questionnaire. The scores range from one (1); the least agreement with the statement, to five (5); the most agreement with the statement.

Table 4.

A Table showing the number of incidences (n), percent incidence, and weighted standard deviation (SD) of surgical complications as secondary outcomes of the study.

| n | Percent | Weighted SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection rate | 1221 | 0.70% | 0.38% |

| Seroma rate | 340 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Hematoma rate | 1315 | 1.16% | 1.85% |

| Thrombosis | 123 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Aberrant Scarring | 423 | 2.17% | 3.33% |

| Revision rate | 1260 | 2.94% | 2.02% |

| Permanent nerve damage | 1250 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Sinusitis | 517 | 0.19% | 0.40% |

| Hardware palpability | 145 | 3.45% | 2.32% |

Discussion

The current review demonstrates that across the available literature, FGAS consistently and significantly improves patients’ self-reported QoL. Particularly, the data shows that post-operatively, patients have significantly better than neutral psychological, social, and physical well-being. Additionally, the average response for self-perceived postoperative facial femininity is significantly greater than preoperative, supporting the positive effect the procedure has on self-image. Of the rated scoring scales, the category that demonstrated the most favorable result was that FGAS was important to live life as a woman.

The most common procedures noted in our study included fronto-orbital remodeling, rhinoplasty, chondrolaryngoplasty, and genioplasty. Notably, patients who undergo FGAS select procedures to reconstruct areas which are most dysphoric for them. For a variety of reasons, particularly financial reasons, patients might not be able to undergo all procedures that address every area that is most dysphoric for them. This may have also contributed to several assessed domains such as post-operative femininity perception, social integration, esthetic satisfaction, and satisfaction as not all goals can be achieved for an affordable cost. Therefore, if patients received full funding for FGAS, it is possible that the most common procedures could differ from what were identified in this study, and may be performed at more comparable frequencies.

Of all the procedures, complication rates are relatively infrequent, with the most common complications being hardware palpability, the need for revision procedures, and aberrant scarring. Like any surgery, complications may lead to slightly lower scores on QoL categories, such as liking the appearance of the face while still self-perceiving oneself as feminine and having a comparatively increased QoL. As these procedures become more widely adopted, strategies can be further developed to find new and innovative ways to reduce rates of hardware palpability.

These results suggest that FGAS are important tools that can be used to treat gender dysphoria and/or achieve gender euphoria. Additionally, this data substantiates the growing body of literature supporting FGASs as medically necessary procedures, similar to top surgeries (i.e. chest surgeries) or bottom surgeries (i.e. vaginoplasty, phalloplasty), which are currently covered, partially or fully, by many American insurance plans and all Canadian Provinces (Dubov & Fraenkel, 2018).

Limitations

This study is not without limitations which must be addressed. One such limitation is the lack of standardized patient questionnaires for FGAS. While we were able to derive data from various questionnaires used in the literature and perform statistical analyses compared to a neutral baseline, the optimal review would be performed on multiple studies with patient responses to questions dedicated to the QoL domains both before and after surgery using the same questionnaire. Additionally, FGAS is an umbrella term incorporating various facial plastic surgeries that are not performed uniformly on every patient, as the choice of procedure is tailored individually. For example, one study only performed rhinoplasty, some only performed chondrolaryngoplasty, and others performed a suite of procedures addressing the entire face. Notwithstanding, it is unlikely for this difference in procedure repertoires to significantly impact the findings since the patient’s perception of QoL improvements likely scales with the scale of the procedure(s) performed.

Conclusions

FGAS procedures significantly improve QoL across categories of perceived femininity, psychological well-being, social integration, esthetic satisfaction, and physical health compared to neutral. This review adds to the growing body of literature supporting broadening the definition of “medically necessary transition-related surgeries” to include FGAS.

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ainsworth, T. A., & Spiegel, J. H. (2010). Quality of life of individuals with and without facial feminization surgery or gender reassignment surgery. Quality of Life Research, 19(7), 1019–1024. 10.1007/s11136-010-9668-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman, K. (2012). Facial feminization surgery: Current state of the art. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 41(8), 885–894. 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinga, R. J., Capitán, L., Simon, D., & Tenório, T. (2017). Technical and clinical considerations for facial feminization surgery with rhinoplasty and related procedures. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, 19(3), 175–181. 10.1001/jamafacial.2016.1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berli, J. U., Capitán, L., Simon, D., Bluebond-Langner, R., Plemons, E., & Morrison, S. D. (2017). Facial gender confirmation surgery – Review of the literature and recommendations for Version 8 of the WPATH Standards of Care. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(3), 264–270. 10.1080/15532739.2017.1302862 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonapace-Potvin, M., Pepin, M., Navals, P., Medor, M. C., Lorange, E., & Bensimon, É. (2023). Facial gender-affirming surgery: Frontal bossing surgical techniques, outcomes and safety. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 47(4), 1353–1361. 10.1007/s00266-022-03180-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitán, L., Simon, D., Kaye, K., & Tenorio, T. (2014). Facial feminization surgery: The forehead. Surgical techniques and analysis of results. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 134(4), 609–619. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaya, B. F., Berman, Z. P., Boczar, D., Siringo, N., Rodriguez Colon, R., Trilles, J., Diep, G. K., & Rodriguez, E. D. (2021). Current trends in facial feminization surgery: An assessment of safety and style. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 32(7), 2366–2369. 10.1097/SCS.0000000000007785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, D. W., Bruss, D., Tejani, N., Brandstetter, K., Kleinberger, A., & Shih, C. (2022). Quality of life outcomes after facial feminization surgery. Facial Plastic Surgery & Aesthetic Medicine, 24(S2), S44–S46. 10.1089/fpsam.2021.0373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, D. W., Tejani, N., Kleinberger, A., & Shih, C. (2020). Initial facial feminization surgery experience in a multicenter integrated health care system. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 163(4), 737–742. 10.1177/0194599820924635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daurade, M., Brosset, S., Chauvel-Picard, J., Sigaux, N., Mojallal, A., & Boucher, F. (2022). Trans-oral versus cervico-facial lift approach for mandibular angle resection in facial feminization: A retrospective study. Journal of Stomatology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 123(2), 257–261. 10.1016/j.jormas.2021.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison, S. P., Clifton, M. S., Futrell, W., Priore, R., & Manders, E. K. (2000). Aesthetic considerations in secondary procedures for gender reassignment. Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 20(6), 477–481. 10.1067/maj.2000.111544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubov, A., & Fraenkel, L. (2018). Facial feminization surgery: The ethics of Gatekeeping in transgender health. The American Journal of Bioethics, 18(12), 3–9. 10.1080/15265161.2018.1531159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadkaree, S. K., DeVore, E. K., Richburg, K., Lee, L. N., Derakhshan, A., McCarty, J. C., Seth, R., & Shaye, D. A. (2021). National variation of insurance coverage for gender-affirming facial feminization surgery. Facial Plastic Surgery & Aesthetic Medicine, 23(4), 270–277. 10.1089/fpsam.2020.0226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganry, L., & Cömert, M. (2022). Low-cost and simple frontal sinus surgical cutting guide modeling for anterior cranioplasty in facial feminization surgery: How to do it. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 33(1), e84–e87. 10.1097/SCS.0000000000008064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, N., White, H., Trott, S., & Spiegel, J. H. (2022). Observer gaze patterns of patient photographs before and after facial feminization. Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 42(7), 725–732. 10.1093/asj/sjab434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, A. C., Dang, B. N., Bertrand, A. A., Jain, N. S., Chan, C. H., & Lee, J. C. (2021). Facial feminization surgery under insurance: The University of California Los Angeles Experience. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open, 9(5), e3572. 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isung, J., Möllermark, C., Farnebo, F., & Lundgren, K. (2017). Craniofacial reconstructive surgery improves appearance congruence in male-to-female transsexual patients. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(6), 1573–1576. 10.1007/s10508-017-1012-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khafif, A., Shoffel-Havakuk, H., Yaish, I., Tordjman, K., & Assadi, N. (2020). Scarless neck feminization: Transoral transvestibular approach chondrolaryngoplasty. Facial Plastic Surgery & Aesthetic Medicine, 22(3), 172–180. 10.1089/fpsam.2020.0021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Padula, S., Hersant, B., Chatel, H., Aguilar, P., Bosc, R., Roccaro, G., Ruiz, R., & Meningaud, J. P. (2019). One-step facial feminization surgery: The importance of a custom-made preoperative planning and patient satisfaction assessment. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery, 72(10), 1694–1699. 10.1016/j.bjps.2019.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertz, E. (2022, June 23). Gender-affirming health coverage by Canadian province, territory. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/8900413/gender-affirming-healthcare-province-territory-transgender/

- Morrison, S. D., Capitán-Cañadas, F., Sánchez-García, A., Ludwig, D. C., Massie, J. P., Nolan, I. T., Swanson, M., Rodríguez-Conesa, M., Friedrich, J. B., Cederna, P. S., Bellinga, R. J., Simon, D., Capitán, L., & Satterwhite, T. (2020). Prospective quality-of-life outcomes after facial feminization surgery: An international multicenter study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 145(6), 1499–1509. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000006837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, S. D., Crowe, C. S., & Wilson, S. C. (2017). Consistent quality of life outcome measures are needed for facial feminization surgery. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 28(3), 851–852. 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noureai, S. A. R., Randhawa, P., Andrews, P. J., & Saleh, H. A. (2007). The role of nasal feminization rhinoplasty in male-to-female gender reassignment. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery, 9(5), 318–320. 10.1001/archfaci.9.5.318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaini, M., Perello, R., Tremolada, C., & Agostini, T. (2019). Evolution of full facial feminization surgery: Creating the gendered face with an all-in-one procedure. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 30(5), 1419–1424. 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon, D., Capitán, L., Bailón, C., Bellinga, R. J., Gutiérrez-Santamaría, J., Tenório, T., Sánchez-García, A., & Capitán-Cañadas, F. (2022). Facial gender confirmation surgery: The lower jaw. description of surgical techniques and presentation of results. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 149(4), 755e–766e. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000008969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C. G. (2020). Evaluating patient benefit from laryngochondroplasty. The Laryngoscope, 130(S5), S1–S14. 10.1002/lary.29075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawa, P., Brault, N., Luca-Pozner, V., Ganry, L., Chebbi, G., Atlan, M., & Qassemyar, Q. (2021). Three-dimensional custom-made surgical guides in facial feminization surgery: Prospective study on safety and accuracy. Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 41(11), NP1368–NP1378. 10.1093/asj/sjab032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Grift, T. C., Elaut, E., Cerwenka, S. C., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Kreukels, B. P. C. (2018). Surgical satisfaction, quality of life, and their association after gender-affirming surgery: A follow-up study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(2), 138–148. 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1326190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen, C., Weigert, R., Corre, P., Casoli, V., & Bondaz, M. (2018). [Development of the facial feminization surgery patient’s satisfaction questionnaire (QESFF1): Qualitative phase]. Annales de Chirurgie Plastique et Esthetique, 63(3), 205–214. 10.1016/j.anplas.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]