Abstract

In rodents, loss of growth hormone (GH) or its receptor is associated with extended lifespan. We aimed to determine the signaling process resulting in this longevity using GH receptor (GHR)-mutant mice with key signaling pathways deleted and correlate this with cancer incidence and expression of genes associated with longevity. GHR uses both canonical janus kinase (JAK)2-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling as well as signaling via the LYN-ERK1/2 pathway. We used C57BL/6 mice with loss of key receptor tyrosines and truncation resulting in 1) loss of most STAT5 response to GH; 2) total inability to generate STAT5 to GH; 3) loss of Box1 to prevent activation of JAK2 but not LYN kinase; or 4) total knockout of the receptor. For each mutant we analyzed lifespan, histopathology to determine likely cause of death, and hepatic gene and protein expression. The extended lifespan is evident in the Box1-mutant males (retains Lyn activation), which have a median lifespan of 1016 days compared to 890 days for the Ghr−/− males. In the females, GhrBox1−/− mice have a median lifespan of 970 days compared to 911 days for the knockout females. Sexually dimorphic GHR-STAT5 is repressive for longevity, since its removal results in a median lifespan of 1003 days in females compared to 734 days for wild-type females. Numerous transcripts related to insulin sensitivity, oxidative stress response, and mitochondrial function are regulated by GHR-STAT5; however, LYN-responsive genes involve DNA repair, cell cycle control, and anti-inflammatory response. There appears to be a yin-yang relationship between JAK2 and LYN that determines lifespan.

Keywords: longevity, GH receptor mutants, sexual dimorphism, insulin sensitivity, oxidative stress, inflammation

Rodent models have been particularly useful in the study of mammalian longevity (1). These have revealed the roles of calorie restriction and insulin sensitivity in lifespan, together with the role of growth hormone (GH). It has been reported that GH-, prolactin-, and thyrotropin-deficient Snell and Ames dwarf mice have extended mean lifespans whereas GH transgenic mice are short lived (2). Specifically GH-deficient lit/lit mice also have extended lifespans (1), which was evident in GHR/BP-deleted mice as first reported by Coschigano's group (3).

In an effort to identify the molecular basis for GH-dependent postnatal growth, our group created mice harboring mutations in the GH receptor (GHR) coding sequence, including deletion of the receptor Box1 sequence, and truncations deleting varying extents of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) activation ability, allowing us to conclude that STAT5 activation is instrumental in GH-dependent growth (4). This supported the finding of Kofoed's group in humans identifying a mutant STAT5B as responsible for retarded postnatal growth (5). These mutant mouse strains have also allowed us to dissect the signaling basis for lifespan, given that we have shown the GHR can use both janus kinase (JAK)/STAT5 signaling and LYN/ERK signaling pathways independently (6, 7).

Recently we have defined the receptor binding sites for LYN and JAK2 around the Box1 region, revealing competition between these tyrosine kinase receptors and the role of Lyn in promoting GHR degradation in opposition to Jak2 (8). Importantly, we have also identified transcripts regulated by the Lyn/ERK pathway (7), one of which is necessary for the expression of HLA-G (HLA class I histocompatibility antigen, α chain G), a key immunosuppressive protein required for liver regeneration (9). Here we report insights into the role played by GH in longevity in C57BL/6 mice and its relation to the sexual dimorphism evident in the lifespan of these mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The C57BL/6 mouse lines comprise mice with 1) 30% STAT5 activation ability (Ghr569−/−, truncated at proline 569 with tyrosines 539 and 545 converted to phe); 2), no STAT5 activation ability (Ghr391−/−, truncated at 391); and 3) mice with an inability to activate JAK2 as well as STAT5 (GhrBox1−/−, all prolines of Box1 converted to alanine). In contrast, these mutants (Ghr569−/−, Ghr391−/−, and GhrBox1−/−) still retain the ability to activate SRC family kinase members (4, 6, 7). Receptor null mice (Ghr−/−), were originally provided by J. Kopchick and derived into a C57BL/6 background (10).

Longevity Study

These studies were carried out with University of Queensland Animal Ethics research approval IMB/231/11/NHMRC to M.J.W. and Y.C. (2014). Animals in the longevity study were housed in same-sex pairs and kept under a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 20 ± 2 °C with environment enrichment. Water and food (meat-free rat and mouse diet containing fish meal, SF00-100, 59.3% total carbohydrates, 4.2% total fat, 19.6% protein; Specialty Feeds) were available ad libitum. Solid pellets were replaced with wet mash of the same composition when mice were older than 2 years. All experiments were approved by and performed in accordance with the guidelines set by the University of Queensland Animal Ethics Committee. The animals were checked daily for health and survival and were handled for cage changes only. Animals that appeared to be near death (listless, unable to walk, and cold to the touch) or had large tumors or neoplastic growth approaching 10% of their body weight were euthanized, and the date of euthanasia was considered the date of death. Initial evaluation for the cause of death was based on any evident gross morphology changes (palpable tumors, lesions, etc) and classified into 1 of 3 categories: tumor, sick, and found dead as the cause of death. After death or euthanasia, all mice were fixed in toto in 10% formalin as near as possible to the time of death. Necropsy was performed on fixed carcasses and tissues collected and routine processed at the School of Veterinary Science, University of Queensland Gatton Campus for histopathological analysis to determine the exact cause of death.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

Mouse tissues were homogenized in Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen) using glass beads and RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was then further purified and DNase treated using RNeasy Mini Kit clean up protocol (Qiagen). RNA was reverse-transcribed using Superscript III (Invitrogen) using the random hexamers protocol and used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) with Sybr Green Technology (ABI) in the 7500HT Real Time Cycler (ABI), 7900 Real Time Cycler (ABI), or ViiA7 Real Time Cycler (ABI). For all qPCR experiments, triplicate reactions were performed for each gene including controls using a 2-step amplification program (initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 20 seconds and 60 °C for 30 seconds). A melting curve analysis step was added at the end of amplification, consisting of denaturation at 95 °C and reannealing at 55 °C for 1 minute each. A comparative Ct method was used to determine relative expression in samples. Primers for qPCR were designed using Primer Express 2.0 software (ABI). Final analysis was performed by calculating the change in Ct between the gene of interest normalized against the housekeeping gene β-2 microglobulin (B2M) and expressed as relative messenger RNA levels.

Western Blot Analysis

All tissues (∼100 mg) were homogenized in 500 μL of radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer using a handheld Kinematica Polytron homogenizer (Fisher Scientific) at full speed until no chunks were visible. Tissue homogenates were cleared by centrifugation at full speed for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Total protein was quantified by BCA Assay (Pierce) and resolved on Mini-PROTEAN Precast gradient gels (BioRad). The gel was immunoblotted using the semi-dry Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (BioRad). Membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin or 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were probed by incubating with specific primary antibody (Table 1). Blots were washed and incubated with 1:10 000 dilution of secondary anti-immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (GE Healthcare) in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were washed and proteins visualized with a chemiluminescent reagent (GE Healthcare) via exposure to x-ray film (Fuji Film). The x-ray film was imaged using Epson Perfection scanner. Samples for Western blotting were analyzed conjointly with our previous study (11), and some loading controls are also shown in that published work.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in this study

| Antibody (clone) name | Catalog No. | RRID | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH (14C10) | 2118 | AB 561053 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| β-TUBULIN (9F3) | 2128 | AB 823664 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| INSRβ (4B8) | 3025 | AB 2280448 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| HNF4α (H-1) | sc-374229 | AB 10989766 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| P-STAT3 Y705 (D3A7) | 9145 | AB 2491009 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| STAT3 (79D7) | 4904 | AB 331269 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| PGC1 | ab106814 | AB 10865490 | Abcam |

| Total Oxphos Rodent Antibody | ab110413 | AB 2629281 | Abcam |

| SIRT1 (DID7) | 9475 | AB 2617130 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| SIRT2 (D4S6J) | 12672 | AB 2636961 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| SIRT3 (D22A3) | 5490 | AB 10696895 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| SIRT6 (D8D12) | 12486 | AB 2636969 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| P-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) | 4511 | AB 2139682 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| p38 MAPK | 9212 | AB 330713 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| SDHB (E3H9Z) | 92649 | AB 3644290 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| COX IV | 4844 | AB 2085427 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| NRF1 (D9K6P) | 46743 | AB 2732888 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| NRF2 | 12721 | AB 2715528 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| SOD1 | 37385 | AB 3073954 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| FGF21 | sc-81946 | AB 2104609 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| IGF1Rβ (D23H3) | 9750 | AB 10950969 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| EGFR | 4267 | AB 2246311 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| Acetyl-α-lysine (K40) | 5335 | AB 10544694 | Cell Signaling Technology |

| NF-κB p65 (D14E12) | 8242 | AB 10859369 | Cell Signaling Technology |

Abbreviations: MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF, nuclear factor; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Results

Lifespan Extension

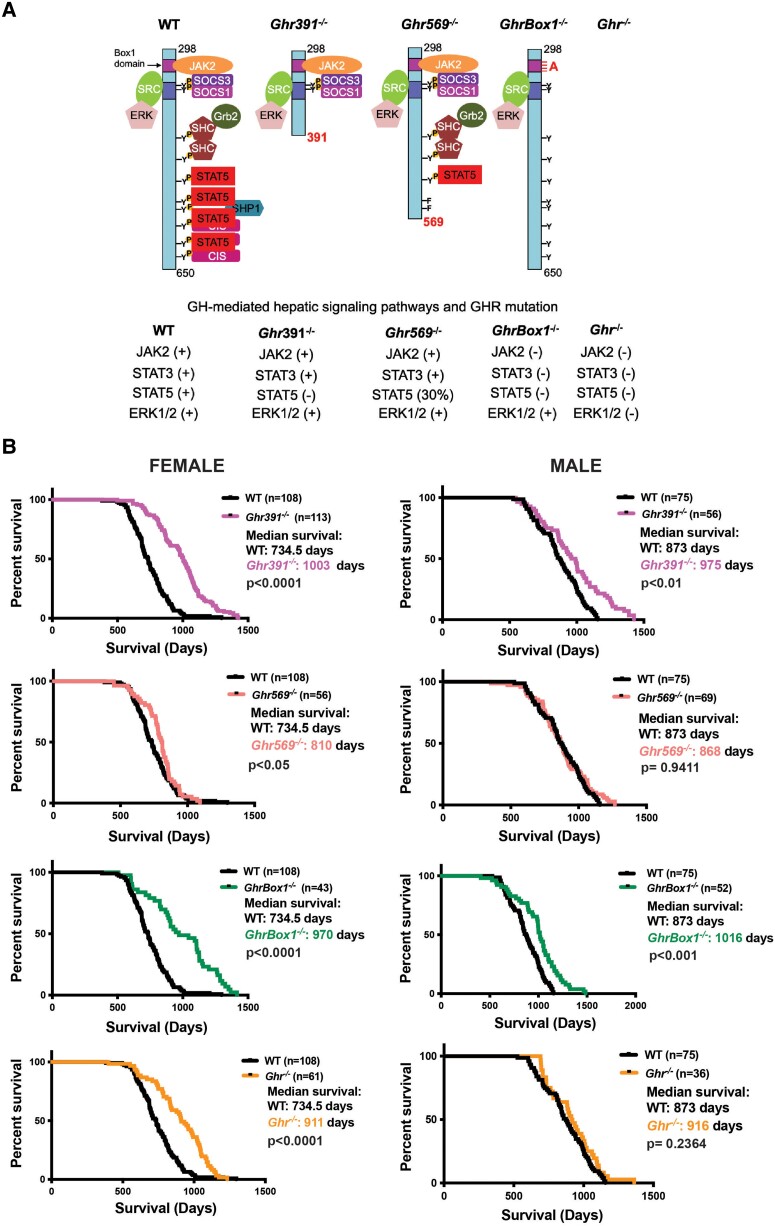

The schematic indicates GH-mediated signaling pathways activated across the Ghr knockin and knockout models. JAK2 signaling includes JAK2-STAT1/3/5 activation (Fig. 1A). Fig. 1B shows Kaplan-Meier plots of lifespan for the 4 Ghr mutants compared with wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice.

Figure 1.

Growth hormone (GH)-mediated LYN/ERK (SRC/ERK) signaling promotes lifespan extension in mice independent of sex. (A) GH-mediated signaling pathways for each Ghr-mutant mouse line used in this study. (B) The median survival of Ghr-mutant and wild-type (WT) mice. Differences in survival between groups compared to WT of the same sex were evaluated by Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test.

The Ghr569−/− female mutants with 30% residual GH-mediated STAT5 activation had a median survival of 810 days, hence a modest 11% increase in median lifespan extension, without any increase in maximal lifespan (see Fig. 1B). Removal of all GH-STAT5 activation by truncation at 391 (Ghr391−/−) resulted in a 36% increase in median lifespan and a statistically significant increase in maximal lifespan compared to WT females (see Fig. 1B). Removal of all GH-STAT5 activation and JAK2 activation, leaving LYN to act alone (GhrBox1−/−), resulted in a 32% increment in median lifespan with a statistically significant increment in maximal lifespan compared to WT females (see Fig. 1B). However, removal of GH-STAT5 activation (Ghr391−/−) as well as JAK2 and LYN activation (Ghr−/−) in females resulted in only a 24% increase in median lifespan and a lesser increase in total lifespan in comparison to WT females (see Fig. 1B). Evidently, LYN activation can extend lifespan more than total loss of receptor in females.

In males, the 569 truncation mutants (Ghr569−/−) showed no change in lifespan parameters, while the total loss of receptor (Ghr−/−) resulted in only a 5% increase in median lifespan and no change in total lifespan in these C57BL/6 mice (see Fig. 1B). However, as with the females, loss of GH-STAT5 activation (Ghr391−/−) in males resulted in a 11.5% increase in median lifespan and a statistically significant increase in total lifespan as compared to WT. When JAK2 signaling was also lost, while LYN activation remained (GhrBox1−/−), there was a 16% increase in median lifespan together with a statistically significant increment in total lifespan as compared to WT males.

We note that while the WT females had a shorter lifespan than the males, the effect of removing GH-STAT5 activation brought the female lifespan close to that of the mutant males. These data indicate that females are more sensitive to JAK-STAT5 shortening of lifespan, while LYN signaling through GHR is the main driver of lifespan extension in both sexes.

Histopathology

Table 2 summarizes cancer incidence at death in the 4 mutant strains. While the numbers in some categories are modest, some trends are clear. Loss of Ghr in the null (knockout) mice decreased the incidence of lymphoma both in male and female mice, as well as bronchioalveolar cancer and hepatocellular cancer in males. Removal of around 70% of GH-STAT5 activation ability (Ghr569−/−) had little effect on lymphoma or hepatocellular cancer incidence. Removal of all GH-STAT5 activation (Ghr391−/−) appeared to decrease the incidence of bronchioalveolar cancer in males but strikingly did not affect the incidence of lymphoma in males, although there appeared to be a decrease in females. There was, however, an increase in hepatocellular cancer in males and myeloid leukemia in females. Removal of both GH-JAK2 and GH-STAT5 signaling (GhrBox1−/−) resulted in decreases in lymphoma and bronchioalveolar cancer in males with a higher number in the miscellaneous category, indicating death from noncancer causes in most mice. Lymphoma incidence in GhrBox1−/−-mutant females was also reduced (as opposed to the Ghr391−/− GH-STAT5 signaling–deleted mice). Collectively, the data suggest that choice of GHR signaling pathway can alter not just the incidences but also the type of cancer in C57BL/6 mice.

Table 2.

Percentage of death for each diagnosed cancer by genotype with number of mice for each type in parenthesis

| WT | Ghr569−/− | Ghr391−/− | GhrBox1−/− | Ghr−/− | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of death | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| BAA/BAC | 12 (3) | 4 (1) | 19 (6) | 6 (1) | 0 | 5 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (2) |

| Lymphoma | 36 (9) | 63 (17) | 45 (14) | 44 (8) | 53 (9) | 40 (17) | 17 (3) | 35 (7) | 14 (1) | 47 (9) |

| Hepatitis | 8 (2) | 4 (1) | 13 (4) | 11 (2) | 12 (2) | 12 (5) | 11 (2) | 5 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) |

| Histiosarcoma | 4 (1) | 0 | 6 (2) | 11 (2) | 0 | 9 (4) | 6 (1) | 5 (1) | 0 | 10 (2) |

| HCC/HCA | 20 (5) | 0 | 16 (5) | 0 | 24 (4) | 9 (4) | 6 (1) | 0 | 14 (1) | 0 |

| Hemangiosarcoma | 4 (1) | 0 | 3 (1) | 0 | 6 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Nephritis | 4 (1) | 0 | 0 | 11 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Histiocytoma | 0 | 0 | 3 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (1) | 0 |

| SCC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Rhabdosarcoma | 0 | 4 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (1) | 14 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Myeloid leukemia | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 | 6 (1) | 12 (5) | 0 | 10 (2) | 0 | 5 (1) |

| Miscellaneous | 8 (2) | 22 (6) | 0 | 16 (3) | 0 | 9 (4) | 61 (11) | 30 (6) | 43 (3) | 16 (3) |

| Total | (25) | (27) | (31) | (18) | (17) | (43) | (18) | (20) | (7) | (19) |

Abbreviations: BAA/BAC, bronchioalveolar adenoma/bronchioalveolar carcinoma; HCC/HCA, hepatocellular carcinoma/hepatocellular adenoma; Miscellaneous, death from nonneoplastic events or cause of death is unknown; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Characterization of Growth Hormone Receptor Knockin and Knockout Mouse Models

Hepatic expression profiles

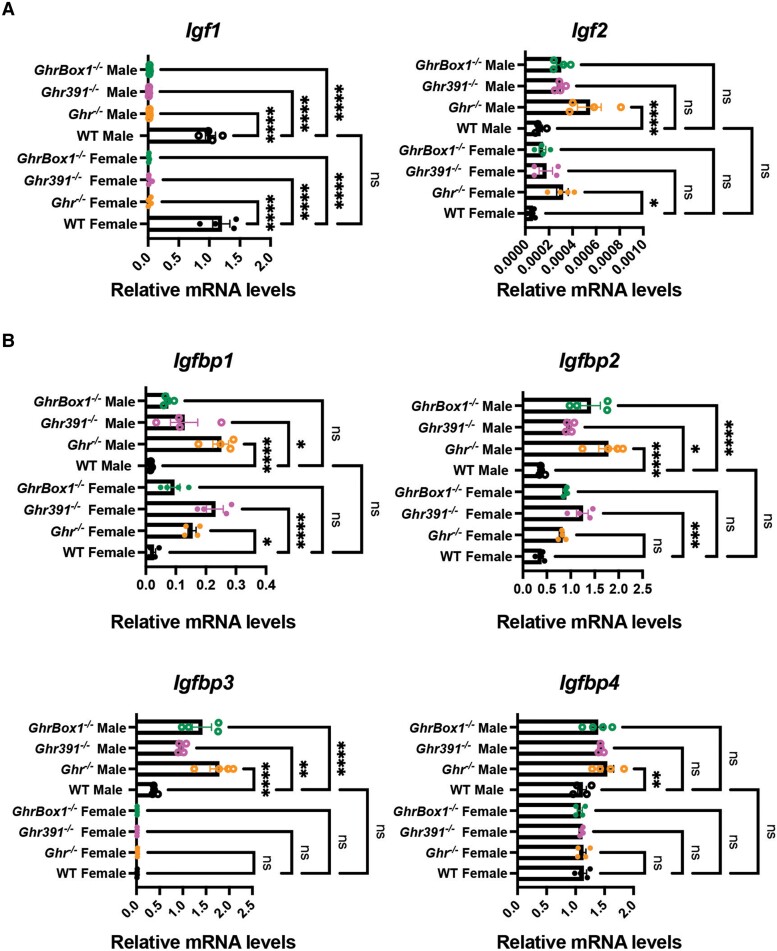

Insulin-like growth factor–related transcripts

Since the liver is the primary target for GH action and therefore an endocrine organ that regulates insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) levels, it is important to determine the molecular elements that are altered in various Ghr mutants that associate with increased protection against cancer and/or promote survival. We therefore assessed transcripts for IGFs and their binding partners in hepatic tissue from young mice (12 weeks) across both sexes. Fig. 2 shows profiles for Igf1/2-related transcripts. In addition to the reduction in Igf-1 transcripts, Igf-2 transcript, although present in low copy numbers, was elevated in all the mutants and achieved statistical significance in all female Ghr−/− mice and all Ghr male mutants (Fig. 2A). Other GH/IGF-1 axis parameters such as IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs) were differentially regulated in the mouse models. Igfbp-1 and -2 were significantly elevated in all Ghr mutants independent of sex. In addition, Igfbp-3 and -4 transcripts were either unchanged or marginally elevated (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Altered hepatic transcripts of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and IGF binding protein (IGFBP) in 12-week-old Ghr-mutant mice fed ad libitum. (A) Decrease in Igf1 and increase in Igf2 and transcripts in 12-week-old male and female mice. (B) IGFBPs were differentially regulated while being sexually dimorphic in its expression. Data represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4 mice/genotype). *P less than .05; **P less than .01; ***P less than .001; ****P less than .0001 compared to WT of the same sex by analysis of variance.

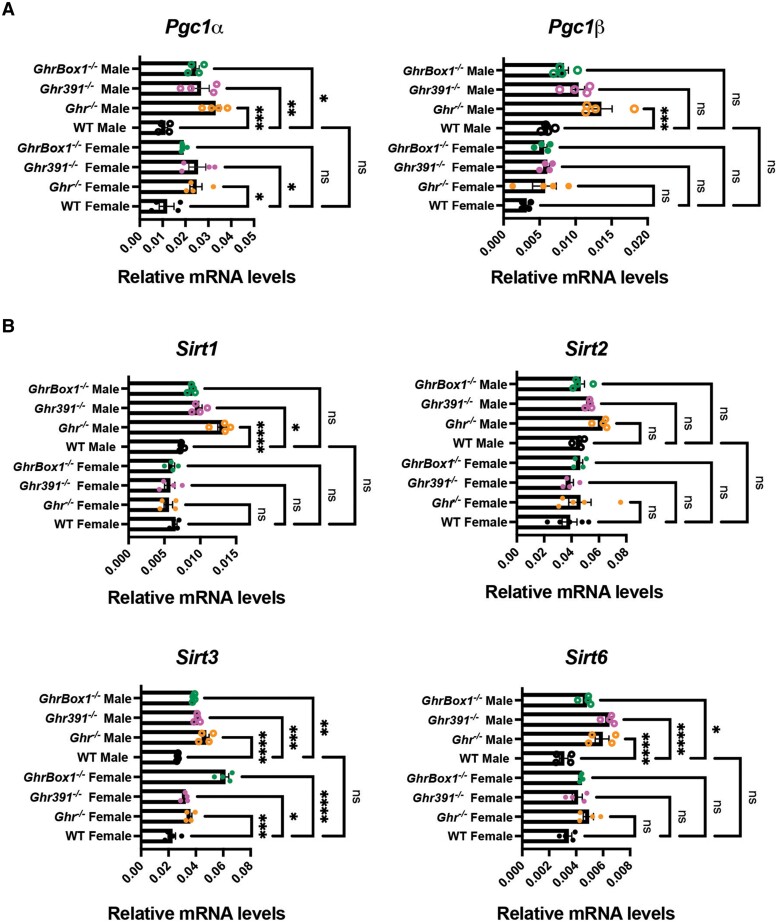

Sirtuins and Mitochondrial Biogenesis Regulators

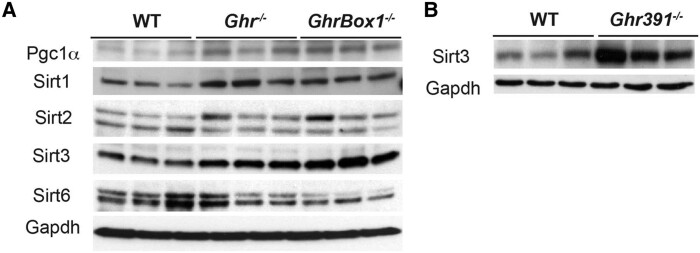

The mitochondrial biogenesis and function regulator Pgc1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α) transcript was statistically significantly elevated in the liver of all Ghr mutants (Fig. 3A). In contrast, Pgc1β transcript was elevated only in the Ghr−/− males (Fig. 3B). At the protein level, Pgc1 was elevated in male Ghr−/− and GhrBox1−/− livers (Fig. 4A and (11)).

Figure 3.

Altered mitochondrial biogenesis regulator and sirtuins transcripts in liver of 12-week-old Ghr-mutant mice fed ad libitum. (A) Mitochondrial biogenesis regulator Pgc1α transcripts were significantly elevated in Ghr mutants while Pgc1β was upregulated only in Ghr male mutants. (B) Key mitochondrial sirtuin, Sirt3 transcript was elevated in all the mutants independent of sex while Sirt1 and 2 were elevated mostly in Ghr−/− males and Sirt6 in Ghr−/− and Ghr391−/− males. Data represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4 mice/genotype). *P less than .05; **P less than .01; ***P less than .001; ****P less than .0001 compared to wild-type (WT) of the same sex by analysis of variance.

Figure 4.

Protein levels of mitochondrial and key sirtuins in liver of 12-week-old male Ghr-mutant mice fed ad libitum. (A) Increase in protein level of Pgc1, Sirt1 and 3 in Ghr−/− and GhrBox1−/− mutants. No change in Sirt2 isoforms was seen, whereas a decrease in Sirt 6 was observed in GhrBox1−/−. (B) Blots representative of n = 3 mice/genotype. Elevated Sirt3 protein in Ghr391−/− male mutant mice as compared to wild-type (WT). Blots representative of n = 3 mice/genotype.

Mammalian homologues of Sir2, the sirtuins showed sex and genotype differences at the transcript and protein level in these mouse models (see Figs. 3B and 4A). Sirt3 transcript was consistently elevated across all genotypes, and this was also evident at the protein level (see Figs. 3B, 4A, and 4B). Sirt1 transcript was significantly elevated only in the Ghr−/− male mice livers while the protein was elevated across all the genotypes in male mice as compared to WT. Transcripts for Sirt2 were only slightly increased in Ghr−/− males with no change at the protein level. Sirt6 transcripts were increased both in male and female Ghr−/− livers as well as in Ghr391−/− and GhrBox1−/− males, but the protein level was not increased in Ghr−/− and GhrBox1−/− male livers. Another observation made for the liver of all 3 male mutant models was increased levels of phosphorylated adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK) (11). AMPK, besides being an energy sensor, is an important player in mitochondrial biogenesis and reactive oxygen species detoxification in conjunction with SIRT1 and SIRT3.

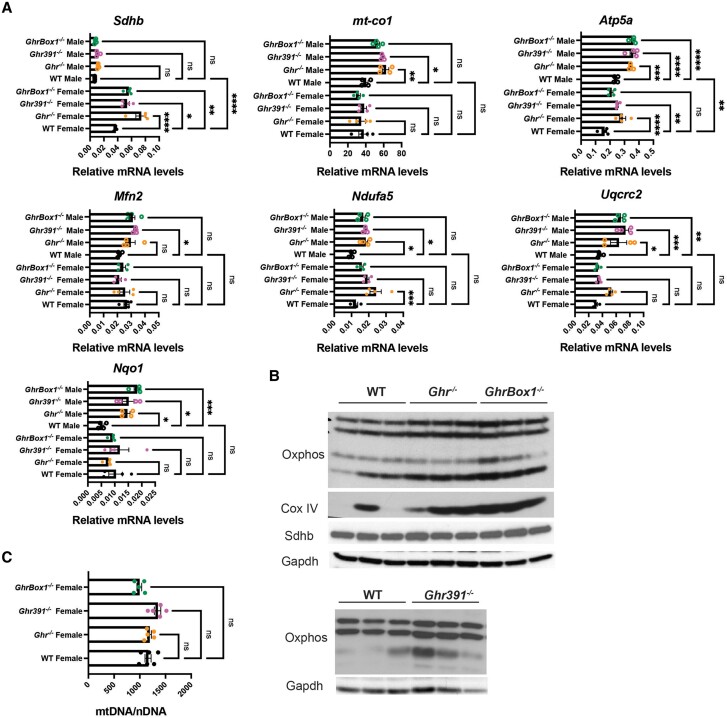

Increased Mitochondrial Function in Ghr Mutants

In addition to the elevated mitochondrial biogenesis markers Pgc1α and Pgc1β, transcripts for mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation enzymes were found to be elevated. These include mt-CO1, Uqcrc2, Atp5a, and Ndufa5, which were upregulated in most of the male mutants (Fig. 5A). In the case of female mutants, Sdhb was elevated across all the mutants, whereas Ndufa5 was increased only in Ghr−/− and Atp5a in Ghr−/− and GhrBox1−/− females (see Fig. 5). MFN2 (mitofusin2), involved in regulation of mitochondria morphology and function, was transcriptionally elevated in Ghr391−/− male Ghr mutants but not in females. The transcript for NAD(P)H dehydrogenase quinone 1, Nqo1, was significantly elevated in all the male Ghr mutants (Fig. 5A). This molecule has been associated with promoting anticarcinogenic and insulin sensitivity effects (12).

Figure 5.

Altered mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation enzymes transcripts and estimation of mitochondrial vs nuclear DNA in liver of 12-week-old Ghr-mutant mice fed ad libitum. (A) Hepatic transcripts for enzymes involved in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complex mt-CO1, Ndufa5 were elevated in Ghr-mutant males while ATP5a was elevated in all the mutant mice across both sexes; Uqcrc2 and Sdhb were elevated only in Ghr−/− male and female mice. Other mitochondrial function regulator genes mfn2 and nqo1 were elevated only in Ghr-mutant males as compared to wild-type (WT) mice. (B) Male Ghr−/−- and GhrBox1−/−-mutant mice livers have elevated levels of cytochrome C oxidase IV (COX IV), mitochondria transcription factor A (mTFAM) as well as OxPhos complexes I, III, and V. Additionally complex II was elevated in GhrBox1−/− mice and no change was evident in SDHA levels. (C) No change in mitochondrial numbers was evident in Ghr-mutant females as evident from lack of differences in mitochondrial vs nuclear genome. Data represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4 mice/genotype). *P less than .05; **P less than .01; ***P less than .001; ****P less than .0001 compared to wild-type (WT) of the same sex by analysis of variance.

Supporting these results, Western blot analysis revealed elevated levels of oxidative phosphorylation enzymes ATP5a (complex V), UQCRC2 (complex III), and NDUFB8 (complex I) in Ghr−/−, GhrBox1−/−, and Ghr391−/− and SDHB (complex II) both in GhrBox1−/− and Ghr391−/− mice (see Fig. 5B). Mt-CO-1 (complex IV), being heat labile, could not be probed in these blots, as the liver lysates were boiled before gel electrophoresis. One of the nuclear-encoded catalytic core subunits of mitochondria, cytochrome C oxidase IV (Cox IV), was elevated in Ghr−/− and GhrBox1−/− mouse livers, while mTFAM (mitochondria transcription factor A), which aids in transcription of mitochondrial genome, did not change. No change in levels of SDHA protein was observed in Ghr−/− and GhrBox1−/− male mice (see Fig. 5B).

It was important to address the question of whether the increase in mitochondrial OxPhos proteins observed was an outcome of the increase in mitochondria numbers. Estimation of the ratio of mitochondrial DNA vs nuclear DNA by qPCR using genome-specific primers was performed to address this question. It was clear that there was no change in mitochondria numbers in any of the Ghr-mutant female mice as compared to WT (Fig. 5C).

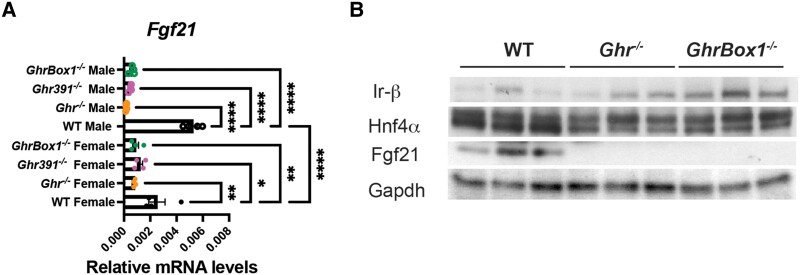

Increased Insulin Sensitivity in Ghr Mutants

The fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is a starvation hormone that is secreted by the liver and is negatively regulated by PGC1α (13), and overexpression of FGF21 has been shown to extend longevity (14) while Fgf21-lacking mice show no decrease in lifespan (15) The hepatic Fgf21 transcript was statistically significantly downregulated in all the mutants across both sexes with higher levels in mutant females than males (Fig. 6A). An important indicator of increased insulin sensitivity is the elevation of insulin receptor β subunit expression in male Ghr−/−, GhrBox1−/−, and Ghr391−/− liver at the protein level (Fig. 6B and (11)) with decrease in levels of negative regulator of IRβ and IRS1/2, Ptp1B in Ghr391−/− mutants (11). The Fgf21 protein was decreased as expected based on transcript level while Hnf4α protein was downregulated in the mutant livers (see Fig. 6B). A range of other insulin-sensitizing proteins and their transcripts were previously identified (11). Although all GHR mice with a lack of GH-mediated STAT5 activation are insulin sensitive, it is evident that insulin sensitivity does not dictate lifespan extension in males.

Figure 6.

Altered hepatic transcript involved in insulin signaling in liver of 12-week-old Ghr-mutant mice fed ad libitum. (A) Fgf21 was downregulated across all mutants in both sexes. (B) Protein levels of Ir-β increased while Hnf4α and Fgf21 decreased in livers of Ghr-mutant male mice. Data represented as mean ± SEM (n = 5mice/genotype). *P less than .05; **P less than .01; ***P less than .001; ****P less than .0001 compared to wild-type (WT) of the same sex by analysis of variance.

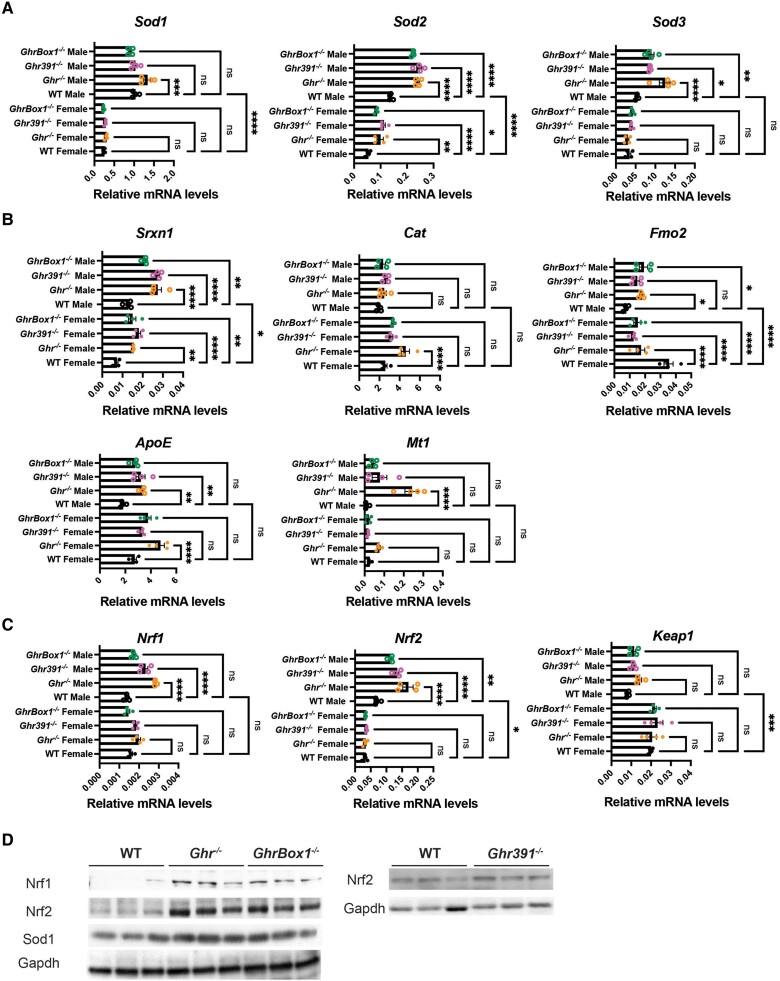

Increased Oxidative Stress Management and Reactive Oxygen Species Detoxification in Ghr-Mutant Mice

The key antioxidant enzymes that catalyze the dismutation of superoxide radicals into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide are superoxide dismutase (SOD1-3). Sod2 and Sod3 were elevated in all Ghr-mutant males while Sod1 was increased only in Ghr−/− males both at the messenger RNA and protein levels (Fig. 7A and 7D). In female Ghr mutants, Sod2 was significantly elevated in all the mutants. In addition, both Sod1 and 2 genes were sexually dimorphic across all genotypes, including WT. Sulfiredoxin encoded by Srxn1 provides oxidative stress resistance by reducing cysteine-sulfonic acid formed under oxidant exposure. The Srxn1 transcripts were significantly elevated in all the Ghr mutants both in males and females, with higher expression in males than females. The ubiquitous enzyme encoding the catalase gene, Cat, was transcriptionally elevated in all the mutants but reached statistical significance only in Ghr−/− female mutant (Fig. 7B). The catalase enzyme is involved in decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water, and oxygen in turn protects the cell from oxidative damage. Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) transcript was elevated in most Ghr mutants while the flavin-containing monooxygenase, Fmo2, which catalyzes oxidation of xenobiotics, was transcriptionally elevated in all the Ghr-mutant males but downregulated in all Ghr-mutant females. Additionally, male Ghr−/− mice exhibited elevated Mt1 (metallothionein 1) transcript with 3 times higher levels in males than females (see Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Altered hepatic transcripts involved in oxidative stress management in 12-week-old Ghr-mutant mice fed ad libitum. (A) Elevated transcripts of superoxide dismutase, Sod1, Sod2, Sod3 in males and Sod2 in female Ghr mutants. (B) Increased Srxn1, flavin-containing monooxygenase (Fmo2) and ApoE in male Ghr mutants and apolipoprotein E (ApoE), metallothionein 1 (Mt1), and Cat in female Ghr−/−. Decrease in expression of Fmo2 and increase in Srxn1 in female Ghr mutants. (C) Altered hepatic transcripts associated with reactive oxygen species detoxification in 12-week-old Ghr-mutant mice fed ad libitum. Elevated transcripts of Nrf1 and Nrf2 in male Ghr mutants and Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) specifically in Ghr−/− males, with Ghr mutants exhibiting sexual dimorphism in Nrf2 and its inhibitor Keap1. (D) Male Ghr−/−- and GhrBox1−/−-mutant mice livers have elevated levels of Nrf1 and Nrf2 antioxidant transcription factors with Ghr−/− liver also expressing higher SOD1 at protein level as compared to wild-type (WT). Elevated Nrf2 in Ghr391−/−-male mutant mice as compared to WT. Blot representative of n = 3 mice/genotype. Data represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4 mice/genotype). *P less than .05; **P less than .01; ***P less than .001; ****P less than .0001 compared to WT of the same sex by analysis of variance.

In addition to SODs, livers of male Ghr mutant mice had increased expression of nuclear factor (NF) erythroid 2–related factor respiratory factors, Nrf1 and Nrf2, both at the transcript and protein levels (Fig. 7C and 7D), with the latter being sexually dimorphic. NRFs are important transcription factors that activate numerous metabolic genes regulating cellular growth and nuclear genes important in respiration, heme biosynthesis, and mitochondrial DNA transcription. In addition, NRFs are responsible for mediating antioxidant response during stress and under the control of KEAP1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1), the transcript of which was increased specifically in Ghr−/− male mutants. Interestingly, there is a striking sexual dimorphic pattern between Nrf2 and Keap1 between male and female mice.

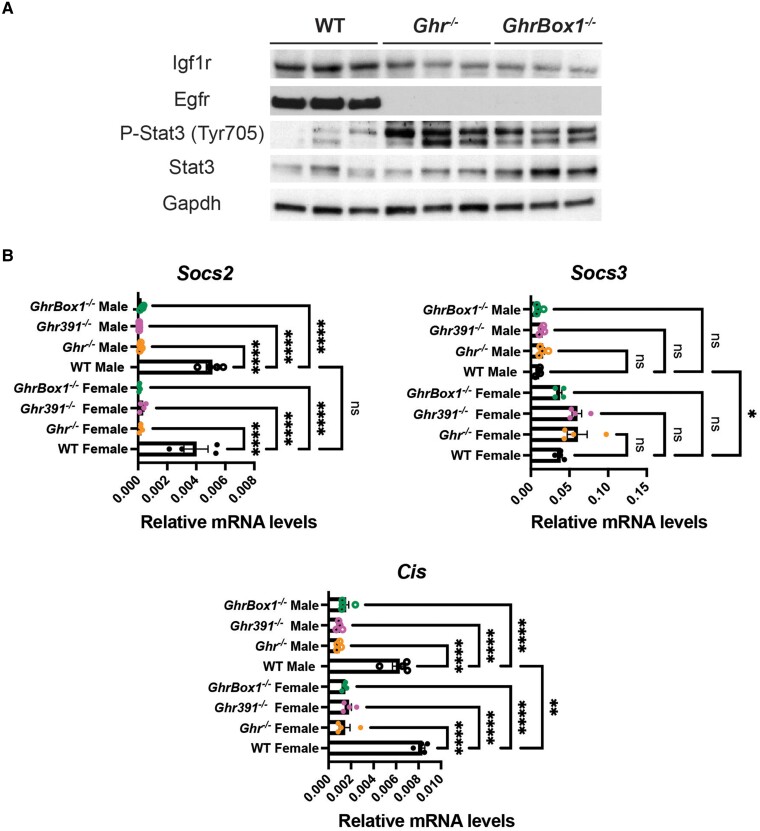

Key signaling elements that are elevated in cancers were downregulated at the protein level in Ghr-mutant mice. Besides the decrease in Igf1 transcript, its receptor Igf1r was also downregulated in the liver (Fig. 8A). The frequently mutated and elevated receptor in cancer, Egfr was also downregulated to undetectable levels in these Ghr mutants. There was an increased expression and activation of STAT3 in the liver potentially due to the loss of GH-induced STAT5 activation. There were also decreased transcripts for the tumor suppressors Socs2 and Cis across all the Ghr mutants, whereas no change was evident in Socs3 expression across the Ghr mutants (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

Altered protein levels of key factors involved in carcinogenesis in liver of 12-week-old male Ghr-mutant mice fed ad libitum. (A) Decrease in expression of Igf1r and Egfr in Ghr−/− and GhrBox1−/− mice and increase in expression of active and total Stat3. Blots representative of n = 3 mice/genotype. (B) Significant decline in Socs2 and Cis transcripts in Ghr-mutant mice while SOCS3 remains unaltered but sexually dimorphic. Data represented as mean ± SEM (n = 5mice/genotype). *P less than .05; **P less than .01; ***P less than .001; ****P less than .0001 compared to wild-type (WT) of the same sex by analysis of variance.

Decrease in Proinflammatory Factors in Ghr-Mutant Mice

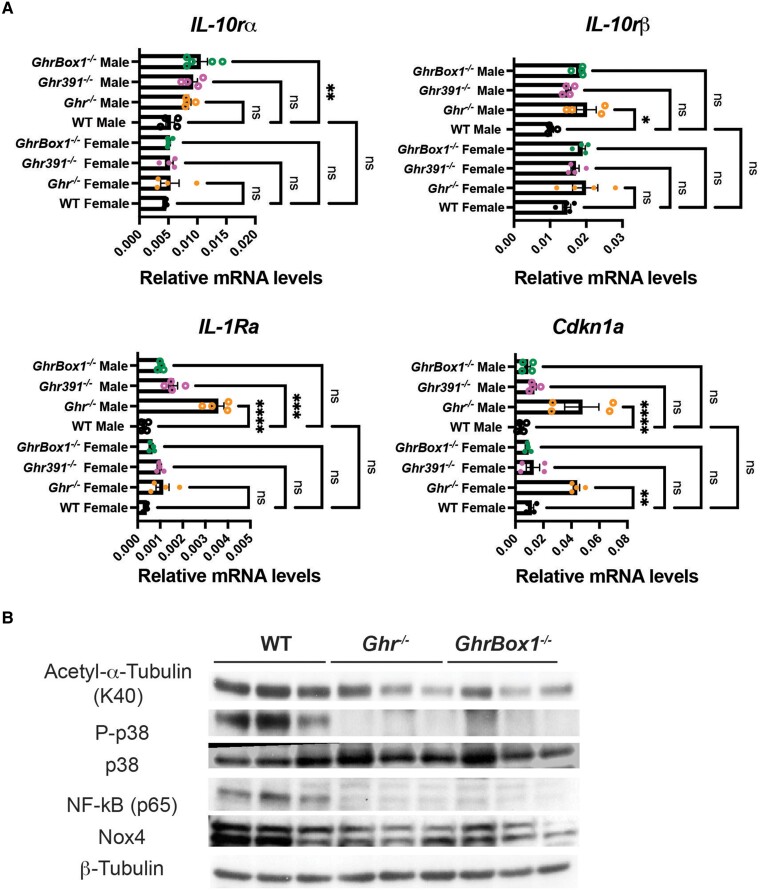

The anti-inflammatory cytokine receptor genes IL-10Rα and IL-10Rβ transcripts were elevated in all male Ghr mutants (Fig. 9A). In addition, there was an increase in the interleukin 1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) messenger levels that have been shown to bind nonproductively to the IL-1 receptor and inhibit binding of IL-1, thereby decreasing inflammation. Expression of IL-1RA had an overall increasing trend in all Ghr-mutant mice but attained statistical significance only in Ghr−/− males and females and Ghr391−/− males (see Fig. 9A). Transcription of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (Cdkn1a), which functions as a regulator of cell cycle progression at G1 and plays an important role in controlling DNA damage-induced G2 arrest (16), was elevated in Ghr−/− males and females (see Fig. 9A).

Figure 9.

Altered hepatic transcripts involved in inflammatory stimuli in 12-week-old Ghr-mutant mice fed ad libitum. (A) Elevated transcripts of IL-10rα and IL-10rβ in male Ghr mutant and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (Cdkn1a), in Ghr−/− males and females. No change was evident in IL-1β levels. (B) Decreased protein levels of inflammation modulators in livers of 12-week-old male Ghr mutants fed ad libitum. Decrease expression of acetylated tubulin (K40), phosphorylated p38 stress kinase, as well as inflammatory and immune response modulator nuclear factor (NF)κB p65 subunit and oxidative stress generator NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) in Ghr−/− and GhrBox1−/− mice. Blots representative of n = 3 mice/genotype. Data represented as mean ± SEM (n = 4 mice/genotype). *P less than .05; **P less than .01; ***P less than .001; ****P less than .0001 compared to wild-type (WT) of the same sex by analysis of variance.

The alterations in transcripts were accompanied by a decrease of other proinflammatory signal modulators at the protein level. There was a decline in levels of acetylated tubulin, an anti-inflammatory signal, as well as that of active stress kinase p38 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), indicative of elevated stress in WT mice (Fig. 9B). This was also supported by a reduction in NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) expression along with p65 subunit of NF-κB, which is a potent inflammation and oxidative stress generator.

Discussion

Hitherto, studies on the increased longevity as a result of removal of GH or its receptor have focused on JAK2-STAT5 signaling. In light of our demonstration (8) that a second tyrosine kinase, LYN, mediates JAK2-independent actions, competes for receptor binding with JAK2 and enhances receptor degradation, we needed to reassess the roles of these signaling elements in determining longevity.

Our lifespan data reveal a role for LYN-GHR in extending lifespan that becomes evident in the absence of GHR-STAT5 signaling. Loss of around 70% of GH-STAT5 signaling is without effect on median lifespan in males and has no effect on total lifespan with only a small extension in median lifespan in females. However, total loss of GH-STAT5 signaling reveals substantial increases in total and median lifespan both in males and females. Removal of JAK2 as well as GH-STAT5 signaling in the Box1 mutant further increased the median lifespan in males with a similar maximum lifespan evident. Knockout of the receptor itself removes the influence of LYN signaling, so the median lifespan of these mice reduces almost to the same as WT for males. However, for female GHR-knockout mice, there is an increase both in median and maximal lifespan compared to WT mice, though less than for Ghr391−/− or GhrBox1−/− mice, implying that LYN signaling also contributes to extended lifespan in females. This sexually dimorphic response in lifespan of GHR-knockout mice has also been reported by Junnila's group in mice with GHR knockout in young (6-week-old) mice whereby males do not show lifespan extension in a C57BL/6 background, as for our study (17).

Histopathology analysis of cause of death in these mice revealed a high incidence of lymphoma in WT females (63%) but a lesser incidence in males (36%). These incidences are substantially decreased by removal of GH-STAT5 in 391 truncated females (44%), although not in males (53%), for which additional removal of GH-JAK2 signaling is required to reach 17% (see Table 2). Evidently the increased GH secretion in the absence of STAT5 is driving JAK2 to promote lymphomas without shortening lifespan in the Ghr391−/− males, presumably because LYN signaling compensates. The difference in female lifespan is concordant with the ability of constitutively active STAT5A/B to drive rapid mortality from CD8+ T-cell lymphoma accompanied by upregulation of cell cycle genes (18). Also, autocrine and paracrine GH induced in damaged senescent cells results in accumulated DNA damage through suppression of the DNA damage response by decreasing ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase activity and p53 (19), and this would further promote neoplastic transformation.

Sexual dimorphism in rodents affects hundreds of genes, and STAT5-dependent sexual dimorphism has been extensively studied by Laz and Waxman's groups, particularly with reference to rodent liver metabolism (20, 21). Males experience large pulses of GH with nadirs between pulses reaching close to zero, while in the female, GH pulses are weaker, but with a statistically significant baseline level. These patterns control STAT5 generation and its regulation of numerous enzyme transcripts through high- and low-affinity STAT5 binding sites on their promoters. They confer upregulation or downregulation on specific STAT5 targets. An examination of our WT mice data reveals sexually dimorphic expression of genes known to be related to longevity and antioxidant ability, which could account for the greater longevity in male C57BL/6 mice. These include antioxidant Sod1 and Sod2, implicated as longevity genes (22), which are expressed at higher levels in WT males, the tumor-suppressor gene Sdhb, antioxidant Srxn1, and Nrf2, oxidative stress response genes implicated in longevity, all expressed at higher level in WT male mice. Sod2 transcripts further increased with removal of STAT5, as do Srxn1 transcripts in both sexes.

Does the loss of these direct genomic actions of STAT5 account for all the life extension seen in Ghr391−/− and GhrBox1−/−? If this were so, then the lifespan of these mutants would match that of the Ghr−/− mice. However, inspection of the Kaplan-Meier survival data shows that Ghr391−/− and GhrBox1−/− lived significantly longer than the Ghr−/− mice. While it is possible that JAK2 could be acting without GH receptor tyrosine phosphorylations, the finding that Box1-mutant mice (GhrBox1−/−), which cannot bind JAK2, also exhibit lifetime extension indicates a role for the LYN/ERK pathway. Indeed, the tyrosine kinase LYN has been identified as 1 of 4 longevity genes in a candidate study of nonagenarian Korean men (23). This may fit with the observation that male humans with an exon 3 deletion in the GHR (d3-GHR) have exceptional longevity as GH stimulation of cells expressing d3-GHR show higher activation of extracellularly regulated kinase (ERK) compared to cells expressing WT GHR, while there was no difference in STAT5 activation (24).

Although originally implicated in B-cell receptor regulation (25), LYN has many roles and is widely distributed throughout the body, including myeloid cells, the nervous system, epithelial adipose and endocrine cells, and in many cancers (as is the GHR) (26, 27). It is involved in signaling by the B-cell receptor, the EPO receptor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor, and C-kit, with phosphorylation of many targets, including PI 3-kinase, FAK, PLCg, ras-GAP, and MAPK. LYN has important functions in hematopoietic cells from early stem/progenitor to multiple lineages of the lymphoid and myeloid systems. In immune cells, LYN has a central regulatory role in phagocytosis and the killing of infected and dying cells and release of inflammatory cytokines. Lyn-knockout mice develop an autoimmune disorder similar to systemic lupus erythematosus but are more susceptible to infection. This demonstrates the ability of LYN to act as a suppressor of toll-like receptor–induced inflammation and B-cell signaling via recruitment of phosphatases such as SHP1 and SHIP1 to ITAM motifs as well as its role as an initiator of signaling (the “duplicitous nature of LYN”). LYN exists in two alternatively spliced forms, LYN A and LYN B, which differentially regulate both immune and cancer cell signaling (26).

There is evidence that LYN promotes silencing of ATM-dependent checkpoint signaling during recovery from DNA double-strand breaks by decreasing phosphorylation of CHK2 and KAP1 (28). LYN is activated and translocated into the nucleus on DNA damage induction, and LYN regulates apoptosis both negatively and positively during the DNA damage response (28). GH acts through induction of WIP1 to dephosphorylate ATM and its effectors, suppressing the DNA damage response (29), which should result in increased cancer formation. Hence, Ghr−/− mice should be less cancer prone than GhrBox1−/− mice, although the small numbers in our study preclude a conclusion here.

Why then do Ghr−/− males display only WT lifespan, whereas Ghr391−/− and GhrBox1−/− mice display an extended lifespan? Inspecting our transcript data for differences between these 3 mutants, particularly between GhrBox1−/− mice with LYN signaling and Ghr−/− without this, reveals that Cdkn1 transcription is elevated in Ghr−/− (see Fig. 9 and (7)), but not in GhrBox1−/− or Ghr391−/−. Cdkn1 deletion improves stem cell function and lifespan in mice (30), suggesting that GhrBox1−/− or Ghr391−/− mice would have a greater lifespan than Ghr−/− mice, as observed. The Blm ReqQ-like helicase transcript is decreased in Ghr−/− relative to GhrBox1−/− (7), and Blm is required for fork stability during DNA repair. It senses DNA damage and recruits other repair proteins to the site of DNA breaks in an ATM-dependent manner (31). Loss of Blm results in cancer predisposition and genomic instability. Hence, we might expect Ghr−/− mice to have a shorter lifespan than Ghr391−/− or GhrBox1−/− mice. In addition to these two promoters of longevity, we have shown that GH-dependent LYN kinase signaling is necessary for liver regeneration through induction of HLA-G, a key anti-inflammatory protein (9), which is likely to further increase lifespan in Ghr391−/− and GhrBox1−/− mice relative to Ghr−/− mice.

LYN also promotes insulin-independent increased glucose utilization by cell membrane phosphoinositol glycans by inducing phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1). This leads to activation of PI3 kinase and an increase in translocation of Glut-4 to the cell membrane with increased glucose utilization. In turn, activation of the insulin receptor has been shown to increase autophosphorylation of LYN, suggesting a possible feedback loop (32). It is not clear how the upregulation of IRS2 transcript we observe in the Ghr−/− males relative to Ghr391−/− and GhrBox1−/− males relates to this (see Fig. 7), but decreased brain IRS2 extends the lifespan of overweight and insulin-resistant mice (33), and the Gly1957Asp variant has been associated with human longevity (34).

There may be other elements responsible for the increased lifespan seen in Ghr391−/−-and GhrBox1−/−truncated mouse mutants, but the lack of difference between the lifespan of Ghr−/− and WT male mice argues against a role for IGF1 in the absence of LYN signaling, since IGF1 is strikingly low in our Ghr−/− mice ((4) and Fig. 2). Similarly, the sharp decrease in EGF receptor transcripts (4) and protein (see Fig. 8) that results from loss of STAT5 appears to have no effect on male longevity in the Ghr−/− mice. The same can also be said for decreased IGF1 receptor protein (see Fig. 8) and increased Sirt3 and Pgc1a transcription (see Fig. 3). However, these considerations do not apply to female C57BL/6 mice, which conform to the prevailing view linking insulin sensitivity to longevity.

In conclusion, through the use of mice with targeted mutations in the GHR signaling domain, we have shown that two tyrosine kinases acting in opposition determine lifespan. By activating STAT5, GH acts to shorten lifespan, with greatest effects in the female. Conversely, LYN kinase acting through the GHR acts to lengthen lifespan, potentially through modulating the DNA damage response. Further work will be required to define the mechanisms involved and the relationship of sex-dependent GH secretory pulses to both JAK2 and LYN activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof John Kopchick (Department of Biomedical Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, USA), who kindly provided the Ghr−/− mice (29), which we moved to a C57BL/6 background.

Abbreviations

- AMPK

adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase

- ApoE

apolipoprotein E

- Cox IV

cytochrome C oxidase IV

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FGF21

fibroblast growth factor 21

- Fmo2

flavin-containing monooxygenase

- GH

growth hormone

- GHR

growth hormone receptor

- IL-1RA

interleukin 1 receptor antagonist

- JAK

janus kinase

- KEAP1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NF

nuclear factor

- NRF

nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor respiratory

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- WT

wild-type

Contributor Information

Yash Chhabra, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, University of Queensland, St Lucia 4069, Australia; Faculty of Medicine, Frazer Institute, The University of Queensland, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102, Australia; Cancer Signaling and Microenvironment Program, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA 19111, USA.

Helle Bielefeldt-Ohmann, School of Chemistry & Molecular Biosciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia 4069, Australia.

Tania Louise Brooks, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, University of Queensland, St Lucia 4069, Australia.

Andrew James Brooks, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, University of Queensland, St Lucia 4069, Australia; Faculty of Medicine, Frazer Institute, The University of Queensland, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102, Australia.

Michael J Waters, Institute for Molecular Bioscience, University of Queensland, St Lucia 4069, Australia.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) (NHMRC grant No. 1025094 to M.J.W.) and startup funds from Fox Chase Cancer Center to Y.C.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during this study.

References

- 1. Liang H, Masoro EJ, Nelson JF, Strong R, McMahon CA, Richardson A. Genetic mouse models of extended lifespan. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38(11-12):1353‐1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Everitt AV. Food restriction, pituitary hormones and ageing. Biogerontology. 2003;4(1):47‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coschigano KT, Holland AN, Riders ME, List EO, Flyvbjerg A, Kopchick JJ. Deletion, but not antagonism, of the mouse growth hormone receptor results in severely decreased body weights, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor I levels and increased life span. Endocrinology. 2003;144(9):3799‐3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rowland JE, Lichanska AM, Kerr LM, et al. In vivo analysis of growth hormone receptor signaling domains and their associated transcripts. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(1):66‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kofoed EM, Hwa V, Little B, et al. Growth hormone insensitivity associated with a STAT5b mutation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(12):1139‐1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rowlinson SW, Millard K, Clyde-Smith J, et al. An agonist-induced conformational change in the growth hormone receptor determines the choice of signalling pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(6):740‐747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barclay JL, Kerr LM, Arthur L, et al. In vivo targeting of the growth hormone receptor (GHR) box1 sequence demonstrates that the GHR does not signal exclusively through JAK2. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(1):204‐217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chhabra Y, Seiffert P, Gormal RS, et al. Tyrosine kinases compete for growth hormone receptor binding and regulate receptor mobility and degradation. Cell Rep. 2023;42(5):112490‐112515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ishikawa M, Brooks AJ, Fernandez-Rojo MA, et al. Growth hormone stops excessive inflammation after partial hepatectomy, allowing liver regeneration and survival through induction of H2-Bl/HLA-G. Hepatology. 2021;73(2):759‐775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou Y, Xu BC, Maheshwari HG, et al. A mammalian model for Laron syndrome produced by targeted disruption of the mouse growth hormone receptor/binding protein gene (the Laron mouse). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(24):13215‐13220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chhabra Y, Nelson CN, Plescher M, et al. Loss of growth hormone-mediated signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) signaling in mice results in insulin sensitivity with obesity. FASEB J. 2019;33(5):6412‐6430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pearson KJ, Lewis KN, Price NL, et al. Nrf2 mediates cancer protection but not prolongevity induced by caloric restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;105(7):2325‐2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Estall JL, Ruas JL, Choi CS, et al. PGC-1alpha negatively regulates hepatic FGF21 expression by modulating the heme/Rev- Erb(alpha) axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106(52):22510‐22515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Y, Xie Y, Berglund ED, et al. The starvation hormone, fibroblast growth factor-21, extends lifespan in mice. Elife. 2012;1:e00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hill CM, Albarado DC, Coco LG, et al. FGF21 is required for protein restriction to extend lifespan and improve metabolic health in male mice. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. LaBaer J, Garrett MD, Stevenson LF, et al. New functional activities for the p21 family of CDK inhibitors. Genes Dev. 1997;11(7):847‐862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Junnila RK, Duran-Ortiz S, Suer O, et al. Disruption of the GH receptor gene in adult mice increases maximal lifespan in females. Endocrinology. 2016;157(12):4502‐4513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maurer B, Nivarthi H, Wingelhofer B, et al. High activation of STAT5A drives peripheral T-cell lymphoma and leukemia. Hematologia. 2020;103(2):216986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chesnokova V, Melmed S. GH and senescence: a new understanding of adult GH action. J Endocr Soc. 2022;6(1):bvab177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laz EV, Sugathan A, Waxman DJ. Hormone-regulated genes in intact rat liver. Sex-specific binding at low- but not high-affinity STAT5 sites. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(8):1242‐1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holloway MG, Cui Y, Laz EV, Hosui A, Hennighausen L, Waxman DJ. Loss of sexually dimorphic liver gene expression upon hepatocyte-specific deletion of Stat5a-Stat5b locus. Endocrinology. 2007;148(5):1977‐1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. GenAge website . Genes commonly altered during ageing, 2023. Accessed February 2024. genomics.senescence.info

- 23. Park JW, Ji YI, Choi Y-H, et al. Candidate gene polymorphisms for diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and cancer are associated with longevity in Koreans. Exp Mol Med. 2009;41(11):772‐781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ben-Avraham D, Govindaraju DR, Budagov T, et al. The GH receptor exon 3 deletion is a marker of male-specific exceptional longevity associated with increased GH sensitivity and taller stature. Sci Adv. 2017;3(6):e1602025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamamoto T, Yamanashi Y, Toyoshima K. Association of Src-family kinase Lyn with B-cell antigen receptor. Immunol Rev. 1993;132(1):187‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brian BF, Freedman TS. The Src-family kinase Lyn in immunoreceptor signalling. Endocrinology. 2021;162(10):bqab152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ingley E. Functions of the Lyn tyrosine kinase in health and disease. Cell Commun Signal. 2012;10(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fukumoto Y, Kuki K, Morii M, et al. Lyn tyrosine kinase promotes silencing of ATM-dependent checkpoint signalling during recovery from DNA double-strand breaks. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;452(3):542‐547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Apaydin T, Zonis S, Zhou C, et al. WIP1 is a novel specific target for growth hormone action. iScience. 2023;26(11):108117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Choudhury AR, Ju Z, Djojosubroto MW, et al. Cdkn1a deletion improves stem cell function and lifespan of mice with dysfunctional telomeres without accelerating cancer formation. Nat Genet. 2006;39(1):99‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ralf C, Hickson D, Wu L. The Bloom's syndrome helicase can promote the regression of a model replication fork. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(32):22839‐22846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Muller G, Wied S, Frick W. Cross talk of pp125FAK and pp59Lyn non-receptor tyrosine kinases to insulin-mimetic signaling in adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(13):4708‐4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taguchi A, Wartschow LM, White MF. Brain IRS2 signaling coordinates life span and nutrient homeostasis. Science. 2007;317(5836):369‐372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barbieri M, Rizzo MR, Papa M, et al. The IRS2 Gly1057Asp variant is associated with human longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65A(3):282‐286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during this study.