Abstract

CD4+ T cells play a major role in the host defense against viruses and intracellular microbes. During the natural course of such an infection, specific CD4+ T cells are exposed to a wide range of antigen concentrations depending on the body compartment and the stage of disease. While epitope variants trigger only subsets of T-cell effector functions, the response of virus-specific CD4+ T cells to various concentrations of the wild-type antigen has not been systematically studied. We stimulated hepatitis B virus core- and hepatitis C virus NS3-specific CD4+ T-cell clones which had been isolated from patients with acute hepatitis during viral clearance with a wide range of specific antigen concentrations and determined the phenotypic changes and the induction of T-cell effector functions in relation to T-cell receptor internalization. A low antigen concentration induced the expression of T-cell activation markers and adhesion molecules in CD4+ T-cell clones in the absence of cytokine secretion and proliferation. The expression of CD25, HLA-DR, CD69, and intercellular cell adhesion molecule 1 increased as soon as T-cell receptor internalization became detectable. A 30- to 100-fold-higher antigen concentration, corresponding to the internalization of 20 to 30% of T-cell receptor molecules, however, was required for the induction of proliferation as well as for gamma interferon and interleukin-4 secretion. These data indicate that virus-specific CD4+ T cells can respond to specific antigen in a graded manner depending on the antigen concentration, which may have implications for a coordinate regulation of specific CD4+ T-cell responses.

Virus-specific CD4+ T cells are thought to play a major role in successful viral clearance in acute hepatitis B and hepatitis C (1, 3, 7, 31). In memory CD4+ T-cell clones a relatively constant threshold number of T-cell receptors (TCRs) has to be triggered to induce CD4+ T-cell activation as determined by cytokine secretion (43). It is unclear, however, whether this threshold is regularly reached in vivo during different stages of viral infections. Previous studies of the T-cell response during viral hepatitis B and C have used saturating doses of antigen in vitro to detect antigen-specific proliferation or cytokine secretion. In contrast, during the natural course of viral hepatitis, the antigenic load varies by several orders of magnitude within a given compartment (e.g., peripheral blood) and even more between different compartments (e.g., blood and liver). There is evidence from a study on autoreactive human CD4+ T cells that, similar to what has been described for altered peptide ligands, low concentrations of specific peptide can induce partial T-cell activation (19). It is unknown whether this is also true for virus-specific CD4+ T cells that have been isolated from a real disease situation and to what extent the antigen concentration influences the induction of different effector functions. For example, tiny amounts of residual viral antigens may be able to promote long-term CD4+ T-cell memory following resolution of acute hepatitis B and acute hepatitis C (13, 30, 38). In these patients there is no evidence of tissue damage, suggesting that this low level stimulation of CD4+ T cells does not induce inflammatory responses. A detailed understanding of different levels of T-cell activation may contribute to our understanding of the coordinate regulation of the immune response in spontaneous viral clearance as well as to the development of T-cell vaccines for the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis.

During the last several years, considerable progress has been made in the understanding of the molecular basis of T-cell activation. (i) CD4+ T cells recognize antigens in the form of 8- to 12-amino-acid peptides bound to autologous HLA class II molecules (2). Despite a rather low affinity of the TCR for the peptide-HLA complex, specific CD4+ T cells can respond to antigen-presenting cells displaying as few as 50 to 100 specific peptide-HLA complexes (39). However, full T-cell activation has been estimated to require the triggering of approximately 8,000 TCRs (43). This seeming paradox could be explained by the observation that T cells interact with antigen-presenting cells for a prolonged time and that a single specific peptide-HLA complex may serially trigger up to a few hundred TCRs (39). (ii) Evidence has accumulated that the TCR is not just an on-off switch but may be able to transmit qualitatively distinct signals into T cells (15, 26, 27, 34). Minor modifications within the amino acid sequence of a specific peptide can lead to inactive peptides, weaker or stronger agonists and antagonists (32), or so-called altered peptide ligands (APL) (11). While APL selectively induce certain but not all effector functions or even T-cell anergy (36, 37), antagonistic peptides do not activate specific T cells but inhibit stimulation by the wild-type peptide (32). Although different patterns of phosphorylation of TCR subunits have been described after stimulation with APL, the molecular basis for this distinct TCR signaling is still incompletely understood (16, 21, 26, 27, 32). (iii) A high affinity between peptide and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) or a high antigen dose may promote the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Th1 cells, whereas a low affinity between MHC and peptide or a low antigen concentration favors the development of a Th2 cytokine profile (4).

In this study, we investigated the response of virus-specific memory CD4+ T cells to various concentrations of specific peptides and correlated the induction of effector functions with the level of TCR triggering. To this end, we used hepatitis B virus (HBV) core (HBc) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3-specific CD4+ T-cell clones which had been isolated during the early phase of acute hepatitis from patients who subsequently cleared the infection. Our data demonstrate that virus-specific CD4+ T-cell clones can respond to low antigen concentrations with up regulation of activation markers and adhesion molecules. A 30- to 100-fold-higher antigen concentration, which corresponds to the triggering of 20 to 30% of TCRs, is required to induce cytokine secretion or proliferation. The relevance of these findings for the coordinate regulation of the virus-specific T-cell response in acute and chronic viral infections is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptides.

HBc-derived peptides (HBV amino acids [aa] 81–105 [SRDLVVSYVNTNMGLKFRQLLWFHI], HBV aa 145–158 [ETTVVRRRGRSPRR], and HBV aa 146–159 [TTVVRRRGRSPRRR]) and an HCV NS3-derived peptide (HCV aa 1248–1261 [GYKVLVLNPSVAAT]) were synthesized by Multiple Peptide Systems, San Diego, Calif., or Chiron Mimotopes, respectively; all peptides were purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography to >95%.

Specific CD4+ T-cell clones.

HBc-specific CD4+ T-cell clones (summarized in Table 1) were isolated from an individual with acute hepatitis B 2 weeks after the onset of hepatitis, just after the peak of aminotransferase levels and disappearance of serum HBV DNA. The minimal epitopes for these T-cell clones were defined previously as aa 93 to 103 (MGLKFRQLLWF; T-cell clones G9, G40, and G42) or aa 145 to 155 (ETTVVRRRGRS; T-cell clones G27, and G61) (8). All HBc-specific clones were HLA-DRB1∗1401 or HLA-DRB1∗1302 restricted.

TABLE 1.

Summary of HBV- and HCV-specific CD4+ T-cell clones

| Clinical dataa | T-cell clone | Time point of isolation (wk after onset) | Specificity | Cytokine profilebc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute, self-limited hepatitis B; male; 58 yr old; follow-up, 36 mo | G9 | 2 | MGLKFRQLLWFb (HBc aa 93–103) | Th0 |

| G40 | 3 | MGLKFRQLLWF (HBc aa 93–103) | Th1 | |

| G42 | 3 | MGLKFRQLLWF (HBc aa 93–103) | Th1 | |

| G27 | 2 | ETTVVRRRGRSb (HBc aa 145–155) | Th1 | |

| G61 | 3 | ETTVVRRRGRS (HBc aa 145–155) | Th0 | |

| Acute, self-limited hepatitis C; female; 64 yr old; follow-up, 16 mo | L11 | 4 | VLVLNPSVAc (HCV NS3 aa 1251–1259) | Th1 |

Epitope mapping and cytokine determinations are given in reference 9. The deduced amino acid sequence of the specific viral strain was previously determined and found to be identical to that of the peptides used in this study (8).

Epitope mapping and cytokine determinations are given in reference 6. The deduced amino acid sequence of the infecting viral strain was identical to that of the peptide used in this study (unpublished results).

HCV NS3-specific T-cell clone L11 (HLA-DRB1∗1101 restricted) was isolated from an individual with acute hepatitis C shortly after viral elimination, 6 weeks after the onset of acute hepatitis. The minimal epitope was previously determined as aa 1251 to 1259 (VLVLNPSVA) (6).

CD4+ T-cell clones were cultured in 96-well U-bottom plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) at a density of 1 × 104 to 5 × 104/well in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 10% human AB serum, and 20 U of recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2) (kindly provided by Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) per ml. The CD4+ T-cell clones were stimulated every 3 to 5 weeks with irradiated allogeneic peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (5 × 104/well) and 2 μg of phytohemagglutinin (HA16 [Murex Diagnostics, Dartford, United Kingdom]) per ml and were routinely used for experiments 3 to 4 weeks after the last restimulation, when expression of CD25 was back to baseline.

Proliferation assays.

Specific CD4+ T-cell clones were stimulated with different concentrations of specific peptide (0.0001 to 100 μg/ml) in the presence of irradiated autologous PBMC or the following HLA-matched lymphoblastoid cell lines (kindly provided by D. J. Schendel, Geselschaft für Strahlenforschung, Munich, Germany) (45): HO301 (DRA1∗0102, DRB1∗1302, DRB3∗0301, DQA1∗0102, DQB1∗0605, DPA1∗0201, DPB1∗0501) for T-cell clones G9, G40, and G42; TEM (DRA∗0101, DRB1∗1401, DQA1∗0101, DQB1∗05031, DPA1∗01, DPB1∗0401) for T-cell clones G27 and G61; and SPO010 (DRA1∗0101, DRB1∗1101, DRB3∗0202, DQA1∗0102, DQB1∗0502, DPA1∗01, DPB1∗02012) for T-cell clone L11. After 4 days, T-cell cultures were labeled by incubation for 16 h with 2 μCi of [3H]thymidine (specific activity, 80 mCi/mmol [Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom]). The cells were collected and washed on filters (Dunn, Asbach, Germany) using a cell harvester (Skatron, Sterling, Va.), and the amount of radiolabel incorporated into DNA was estimated with a beta counter (LKB/Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). Triplicate cultures were assayed routinely, and the results are expressed as mean counts per minute (cpm).

FACS analyses.

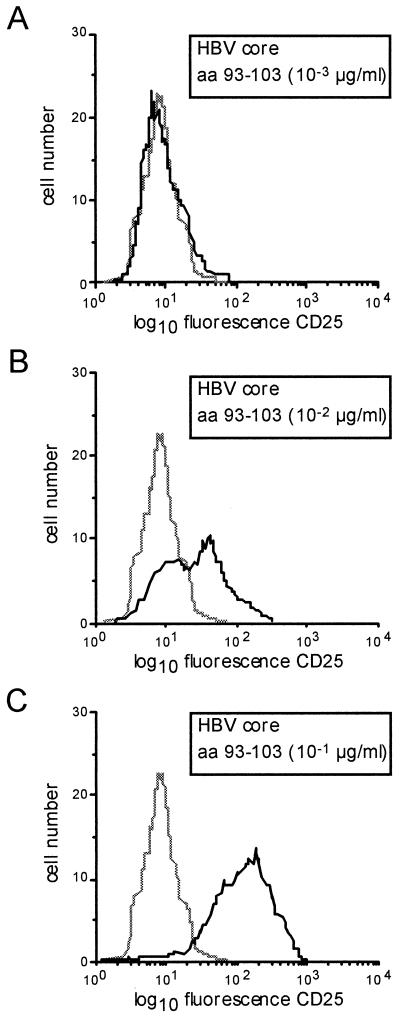

Triple immunofluorescence staining was performed on T-cell clones 16 to 24 h following antigenic stimulation with the following combinations of antibodies: CD25-fluorescein isothiocyanate (Coulter, Hialeah, Fla.), HLA-DR–phycoerythrin (PE), CD54-PE, CD69-PE (Becton-Dickinson, Hamburg, Germany), and CD4-Tricolor (Medac, Hamburg, Germany). FACS analysis was performed with a FACScan instrument (Becton-Dickinson) as described previously (17). Expression of surface molecules was determined as median fluorescence intensity. A typical histogram for the expression of CD25 in response to different antigen concentrations is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Representative histogram showing CD25 expression of a CD4+ T-cell clone at different antigen concentrations. HBc-specific CD4+ T-cell clone G40 has been stimulated with different antigen concentrations inducing no (A), half-maximal (B), and maximal (C) expression of CD25. Cells were gated for CD4 expression to exclude the lymphoblastoid cells that were used as antigen-presenting cells. The dotted line represents unstimulated control cells.

Lymphokine assays.

Specific T-cell clones were stimulated (105 cells/100 μl) with specific peptide in the presence of HLA-matched lymphoblastoid cell lines in a 1:1 ratio. Supernatants were collected after 24 h and stored at −80°C. Secretion of IL-4 and gamma interferon was measured by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay techniques as described previously (41, 42). Cytokine secretion by lymphoblastoid cell lines alone was always below the level of sensitivity.

Anergy induction.

T-cell clone G27 was used for anergy induction 3 to 5 weeks after the last stimulation with phytohemagglutinin. A total of 104 clone cells/well were stimulated with specific peptide (HBc aa 145 to 155 or aa 146 to 155) at various concentrations (0.1, 1.0, 10, or 100 μg/ml) in the presence of HLA-matched lymphoblastoid cell lines (3 × 104/well). After 24 h the cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline and restimulated with HBc aa 145 to 155 (10 μg/ml). Proliferation was determined after 4 days by measuring [3H]thymidine incorporation.

RESULTS

Low antigen concentrations induce CD25 and adhesion molecule expression in the absence of cytokine secretion or proliferation in virus-specific CD4+ T-cell clones.

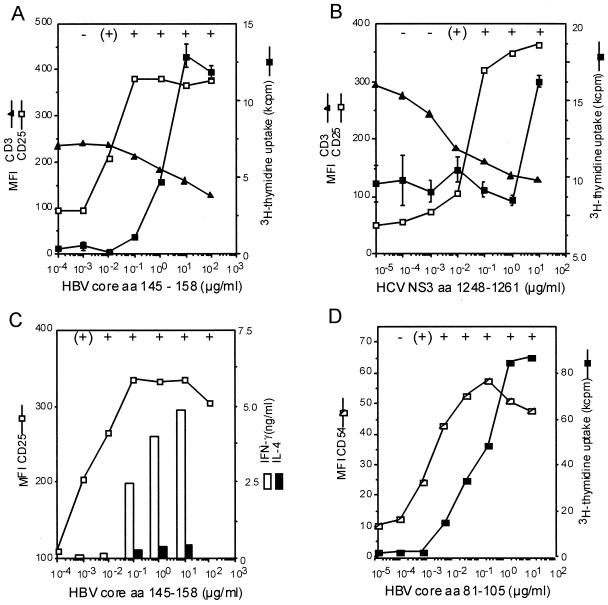

During the natural course of acute HBV or HCV infection, virus-specific CD4+ T cells are exposed to highly variable concentrations of viral antigen. To investigate how virus-specific CD4+ T-cell clones respond to different concentrations of specific antigen in vitro, we stimulated HBc- and HCV NS3-specific CD4+ T-cell clones, which had been isolated during viral clearance from patients with acute hepatitis, with specific peptide at concentrations varying from 100 pg/ml to 100 μg/ml in the presence of homozygous HLA-matched lymphoblastoid cell lines. CD3 and CD4 down regulation were used as substitute markers for TCR internalization (29, 44). The first detectable markers of T-cell activation were CD25 and CD54 (intercellular cell adhesion molecule 1 [CAM-1]) up regulation, increasing the cell size and cluster formation (Fig. 2); similarly, HLA-DR and CD69 expression increased (data not shown). An increase in the levels of these markers could be observed as soon as a decrease in the levels of TCR components CD3 or CD4 occurred (Fig. 2A and B). Typically, cytokine secretion and proliferation required 10- to 100-fold-higher antigen concentrations than did induction of CD25 (Fig. 2A to C) and CD54 expression (Fig. 2D). Whereas the expression of CD25 and adhesion molecules increased as soon as TCR internalization became detectable, a decrease in CD3 expression of 20 to 30% was required for T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion.

FIG. 2.

Induction of activation markers and effector functions in virus-specific CD4+ T-cell clones in relation to TCR internalization. Expression of CD25 and CD54 and T-cell clustering occurred at about 100-fold-lower antigen concentrations than did proliferation or cytokine secretion. Whereas for proliferation a certain threshold of TCR internalization had to be reached, expression of CD25 occurred as soon as TCR internalization became detectable. (A and B) This is shown for the relationship between CD3, CD25, and proliferation with the HBc-specific CD4+ T-cell clone G27 (A) and the HCV-NS3-specific CD4+ T-cell clone L11 (B). (C and D) The secretion of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and IL-4 in relation to CD25 expression is shown for HBc-specific CD4+ T-cell clone G61 (C), and the relation between CD54 and proliferation is shown with the HBc-specific CD4+ T-cell clone G9 (D). All experiments were at least repeated twice, and similar results were obtained with autologous PBMC and HLA-matched lymphoblastoid cell lines as antigen-presenting cells and were also valid for additional T-cell clones (G40 and G42). For all T-cell clones, the formation of cell clusters was evaluated microscopically: cluster formation was judged as absent if T cells were evenly distributed throughout the well, weak if some clusters could be identified whereas other cells were still outside the clusters, and strong if all the cells in the well were concentrated in clusters (see below). Cluster formation correlated strictly with the expression of CD25 and CD54. Symbols: −, absent; (+), weak; +, strong.

Expression of CD25 and adhesion molecules is functional.

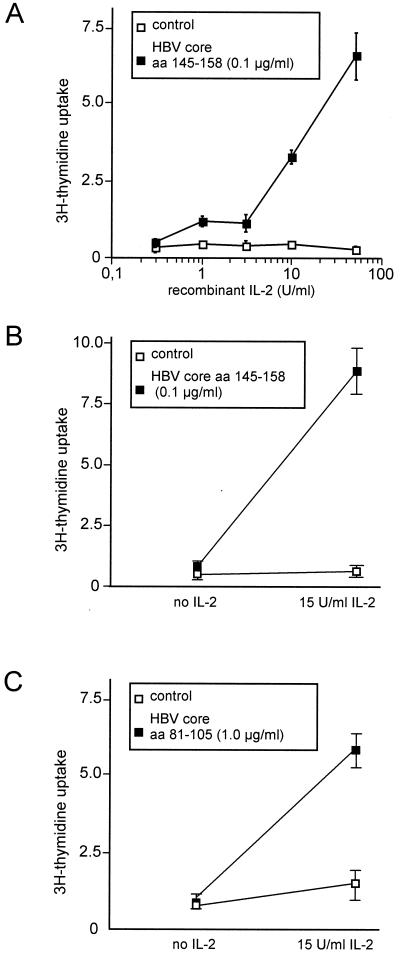

To test whether the expression of CD25 was functional, we stimulated the CD4+ T-cell clones G27, G40, and G61 with a suboptimal concentration of specific peptide and increasing concentrations of recombinant IL-2. Dose-dependent proliferation was induced in the peptide-stimulated cells but not in unstimulated cells (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Response to exogenous IL-2 in three CD4+ T-cell clones stimulated with a suboptimal antigen concentration. (A and B) T-cell clones G27 (A) and G61 (B) were stimulated with 0.1 μg of specific peptide (aa 145 to 158) per ml, which induces high expression of the IL-2 receptor CD25 but no proliferation. (C) Similarly, T cell clone G40 was stimulated with 1.0 μg of peptide aa 81 to 105 per ml. Exogenous IL-2 induces proliferation (solid squares), whereas no proliferation occurred in the absence of peptide stimulation (open squares).

Intercellular adhesion was judged microscopically as formation of cell clusters and correlated with the expression of activation markers and CD54 (ICAM-1). For all clones, cluster formation became detectable with similar kinetics to the expression of CD54, demonstrating the functional expression of adhesion molecules at low antigen concentrations (Fig. 2).

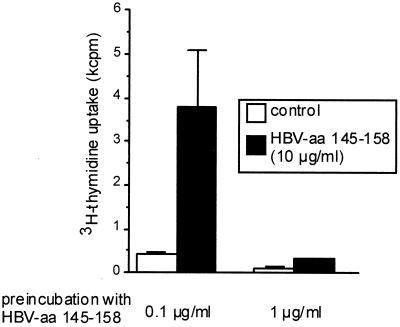

Induction of anergy in ThI clones requires full T-cell activation.

T-cell anergy has been discussed as a mechanism involved in self tolerance but also in the pathogenesis of chronic infections. Stimulation of virus-specific CD4+ T cells with low antigen concentrations induced CD25 expression but no cytokine secretion, while the response to exogenous IL-2 was maintained. These characteristics have frequently been referred to as the anergic phenotype (5, 33). Also, other researchers have claimed that suboptimal stimulation may induce anergy in CD4+ T cells (14). We therefore determined the threshold for anergy induction in an HBV-specific CD4+ T-cell clone (G27), which had previously been shown to be prone to anergy induction following stimulation with high concentrations of specific peptide (8). We found that for G27 the threshold for anergy induction corresponded to the threshold for induction of proliferation (Fig. 4). Stimulation with antigen concentrations that did not induce proliferation left the T-cell clone fully responsive to a higher antigen concentration.

FIG. 4.

Anergy induction in HBV aa 145 to 155-specific CD4+ T-cell clone G27. Prestimulation with a proliferation-inducing peptide concentration (1 μg/ml) leads to unresponsiveness to subsequent restimulation with high antigen concentrations (10 μg/ml). In contrast, prestimulation with 0.1 μg/ml, which induces maximum expression of CD25 but no proliferation, leaves the T-cell clone fully responsive to subsequent stimulation with higher peptide concentrations (10 μg/ml).

T-cell activation does not depend on antigen affinity but on the kinetics of TCR internalization.

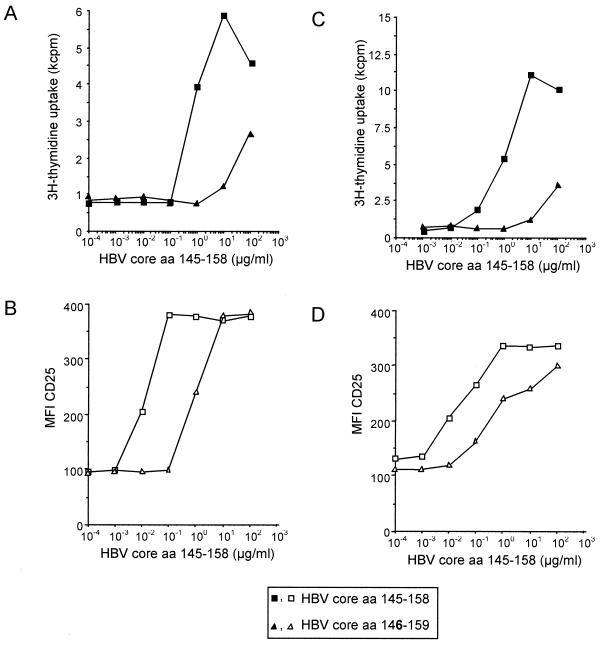

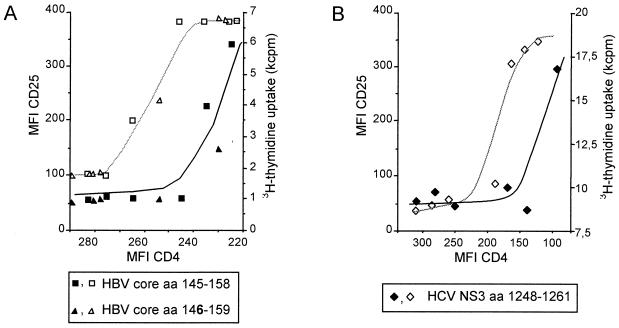

For T-cell clones G27 and G61, which are specific for the minimal epitope HBV aa 145 to 155, a low-affinity ligand which lacks the amino-terminal glutamic acid at position 145 (aa 146 to 159) was discovered, and its effect was compared to that of stimulation with a peptide containing the complete minimal epitope (aa 145 to 158). The low-affinity peptide aa 146 to 159 required 100-fold antigen concentration for the induction of CD25 expression (Fig. 5A and C) and proliferation (Fig. 5B and D) compared to the complete epitope, aa 145 to 158. Notably, independent of the antigen used for stimulation of clone G27, for any given level of TCR internalization, a similar T-cell response was observed (Fig. 6A) and a similar correlation between TCR internalization and the induction of different T-cell functions was found for other clones, as shown, for example, for the HCV NS3-specific T-cell clone L11 (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 5.

Induction of activation markers and effector functions with high- and low-affinity ligands. CD4+ T-cell clones G27 (A and B) and G61 (C and D) have been stimulated with various concentrations of peptide aa 145 to 158, which contains the minimal specific epitope (squares), and the low-affinity variant aa 146 to 159 (triangles). Induction of proliferation (A and C) and CD25-expression (B and D) required a 100-fold higher concentration of the low-affinity peptide aa 146 to 159.

FIG. 6.

Correlation of the degree of TCR internalization with the expression of CD25 (open symbols) and proliferation (solid symbols). (A) For HBV aa 145 to 158-specific CD4+ T-cell clone G27, the correlation of TCR internalization with the induction of T-cell effector functions was studied using the wild-type epitope (aa 145 to 158) and a low-affinity truncated variant (aa 146 to 159). Independent from the epitope used, for any given level of TCR down regulation, a similar degree of CD25 expression and proliferation, respectively, was observed. For both peptides, the individual measurements could be approximated by the same sigmoid-shaped curve. (B) A very similar correlation between TCR internalization and the induction of proliferation and CD25 expression is shown for the HCV NS3-specific CD4+ T-cell clone L11.

DISCUSSION

CD4+ T cells play a major role in host defense against viruses and other intracellular pathogens. The importance of a vigorous CD4+ T-cell response for a favorable outcome of such infections has been shown in many animal models and can be inferred in humans from the occurrence of opportunistic infections in patients with T-helper- cell deficiency states (24, 25, 28). On the other hand, an uncontrolled or overshooting T-cell response may lead to unnecessary and detrimental tissue damage, as seen, for example, in fulminant viral hepatitis or in postinfectious autoimmune disease. It is therefore obvious that a coordinate regulation of the immune response is required to achieve control of the infection on the one hand and to avoid excessive tissue damage on the other.

Here we show that virus-specific CD4+ T cells can respond to low antigen concentrations by up regulation of activation marker molecules and adhesion molecules without secretion of cytokines or proliferation, which require 30- to 100-fold-higher antigen concentrations. What is the relevance of this finding for the virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response? For CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTL) it has been shown that only tiny amounts of antigen are required to induce the lysis of target cells whereas at least 100-fold-higher levels are required for cytokine secretion (40). For CTL, it appears biologically reasonable that specific CTL are extremely sensitive to low antigen concentrations, e.g., for killing of virally infected cells, but that their numbers expand only in the presence of higher levels of antigen. For CD4+ T cells, several immunological situations can be conceived in which a differential regulation of T-cell activation might be required. (i) The interaction between TCR and MHC-peptide complex is of low affinity and is not sufficient to maintain intercellular contact between an antigen-presenting cell and a specific T cell. The early induction of adhesion molecules by triggering of a few TCRs could contribute to stabilization of the cellular interaction and facilitate further triggering of TCRs to achieve full T-cell activation. (ii) Considering a circulating specific CD4+ T cell, it is conceivable that at some distance from the inflammatory site the CD4+ T cell is partially activated by low antigen concentrations. This partial activation may promote T-cell adhesion and IL-2 responsiveness without resulting in too early a secretion of inflammatory cytokines at a site still distant from the center of the inflammatory process. Following migration to the focus of disease, a higher antigen concentration may then trigger full T-cell activation and secretion of cytokines. Thus, a graded CD4+ T-cell response may contribute to the translocation of specific CD4+ T cells to the center of an inflammatory process and avoid tissue damage outside the disease focus. (iii) After various viral infections, a memory T-cell response is maintained for many years and is probably related to the presence of low levels of residual viral antigen. Partial T-cell activation may promote T-cell survival without the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, which might otherwise induce ongoing tissue damage.

What could be the implications of these observations for the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis B and C? Most studies of the virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response so far have used high antigen concentrations (1 to 10 μg of protein or peptide antigens per ml) and have determined either proliferation or cytokine secretion (either in the supernatant or by the enzyme-linked immunoslot assay). By this approach is has clearly been shown for both HBV and HCV that viral clearance is associated with a strong virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response, whereas in patients with chronic hepatitis B or C a virus-specific CD4+ T-cell response is either weak or absent. However, for chronic hepatitis C there are preliminary data suggesting that if CD4+ T cells are analyzed for antigen-induced CD25 expression, virus-specific CD4+ T cells can be detected in the absence of antigen-specific proliferation or cytokine secretion (H. M. Diepolder, N. H. Gruener, J. T. Gerlach, M.-C. Jung, R. M. Hoffmann, R. Zachoval, and G. R. Pape, Abstr. 6th Int. Symp. Hepatitis C Relat. Viruses, p. 65, 1999). A similar observation has been made with HCV-specific CD8+ T cells using HLA class I tetramers: in the peripheral blood of patients, HCV-specific CD8+ T cells were identified that did not produce cytokines and had a low potential for cytotoxicity (18, 23). Future studies are needed to clarify whether these virus-specific CD4+ T cells in chronically infected patients are of lower affinity or may have down regulated the TCR density, which could explain why full T-cell activation including cytokine secretion cannot be induced.

For both HBV and HCV, a high rate of viral mutations has been described and viral escape from immune responses is considered to be a major factor in the pathogenesis of chronic viral hepatitis. TCR triggering depends on the trimolecular interaction between the HLA molecule, the peptide, and the TCR and is therefore influenced by both the binding affinity of the peptide and HLA molecule and the binding affinity between the peptide-HLA complex and the TCR. It has previously been shown that single amino acid changes in a specific peptide can lead to APL. APL induce only incomplete T-cell activation, where certain effector functions are triggered but others are not (10, 12, 35). For two HBc-specific T-cell clones (G27 and G61 [Fig. 5]), we identified a low-affinity peptide ligand which lacks the amino-terminal amino acid of the minimal epitope. At standard concentrations (10 μg/ml), this peptide induced the expression of CD25 and intercellular adhesion but induced no proliferation. Interestingly, when the degree of TCR internalization was studied over a broad range of antigen concentrations, for any level of TCR internalization the variant peptide induced exactly the same response as did the wild-type peptide with regard to phenotype and proliferation. These data support the hypothesis, as previously suggested (19, 20, 22), that if TCR triggering is determined by TCR internalization, it is the quantity rather than the quality of TCR triggering that determines the T-cell response. Moreover, these findings imply that if the consequences of viral mutations on specific T-cell responses are studied, a broad range of antigen concentrations must be used to define the relevance of an individual mutation.

A previous study that looked at the hierarchy of T-cell responses to increasing doses of specific peptide found that two CD4+ T-cell clones specific for the same peptide of the autoantigen myelin basic protein differed significantly with regard to the sequence of T-cell effector functions that were induced (19). No such differences in effector function hierarchy were found in our six different CD4+ T-cell clones from two patients with different viral infections, suggesting that the hierarchy of T-cell functions may be more constant in virus-specific CD4+ T cells.

It should be noted that these observations have been made in CD4+ T-cell clones which have been expanded in vitro. Obviously the cloning procedure itself leads to a selection of T cells, and it is therefore never completely clear whether the clones are representative of the circulating specific CD4+ T cells in vivo. Also, some effector functions may change during in vitro culture. Nevertheless, our findings were very consistent in a set of different T-cell clones from different patients. Also, the durations of in vitro culture of individual clones were quite different, ranging from several weeks to years, and no significant differences were noted between these clones. Moreover, even if the behavior of the CD4+ T-cell clones that we observed cannot be generalized to all primed CD4+ T cells in vivo, it is likely to be part of a preexisting program that becomes active under certain circumstances. This important question can be addressed as soon as disease-specific HLA class II tetramers are available, which will allow the labeling of specific CD4+ T cells in freshly isolated PBMC without prior stimulation with antigen.

In conclusion, our results suggest that CD4+ T cells from patients with self-limited acute hepatitis B or hepatitis C can respond in a graded manner to different antigen concentrations. If this observation can be generalized to specific CD4+ T cells in vivo, it may have implications for the regulation and trafficking of specific CD4+ T cells in general. Our results also suggest that a better knowledge not only of viral sequence variations but also of viral antigen concentrations in vivo may be required for a more complete understanding of the immunopathogenesis of viral infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Wilhelm-Sander-Stiftung (grant 94.072.3) and the European Commission (contract QLRT-PL1999-00356) within the 5th Framework Program.

We thank Antonio Lanzavecchia, Istituto di Ricerca in Biomedicina, Bellinzona, Switzerland, and Annegret de Baey, Micromet GmbH, Munich, Germany, for critical discussion; Alessandro Sette and Scott Southwood, Epimmune Inc., San Diego, Calif., for determinations of HLA-peptide-binding affinities; and Jutta Döhrmann, Carmen Amsel, and Carola Steiger for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cerny A, Chisari F V. Pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis C: immunological features of hepatic injury and viral persistence. Hepatology. 1999;30:595–601. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chien Y H, Davis M M. How alpha beta T-cell receptors ‘see’ peptide/MHC complexes. Immunol Today. 1993;14:597–602. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90199-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chisari F V, Ferrari C. Hepatitis B virus immunopathogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:29–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Constant S, Pfeiffer C, Woodard A, Pasqualini T, Bottomly K. Extent of T cell receptor ligation can determine the functional differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1591–1596. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeSilva D R, Urdahl K B, Jenkins M K. Clonal anergy is induced in vitro by T cell receptor occupancy in the absence of proliferation. J Immunol. 1991;147:3261–3267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diepolder H M, Gerlach J T, Zachoval R, Hoffmann R M, Jung M C, Wierenga E A, Scholz S, Santantonio T, Houghton M, Southwood S, Sette A, Pape G R. Immunodominant CD4+ T-cell epitope within nonstructural protein 3 in acute hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:6011–6019. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6011-6019.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diepolder H M, Hoffmann R M, Gerlach J T, Zachoval R, Jung M C, Pape G R. Immunopathogenesis of HCV infection. Curr Stud Hematol Blood Transfus. 1998;62:135–151. doi: 10.1159/000060476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diepolder H M, Jung M C, Wierenga E, Hoffmann R M, Zachoval R, Gerlach T J, Scholz S, Heavner G, Riethmuller G, Pape G R. Anergic Th1 clones specific for hepatitis B virus (HBV) core peptides are inhibitory to other HBV core-specific CD4+ T cells in vitro. J Virol. 1996;70:7540–7548. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7540-7548.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diepolder H M, Ries G, Jung M C, Schlicht H J, Gerlach J T, Gruener N H, Caselmann W H, Pape G R. Differential antigen-processing pathways of the hepatitis B virus e and core proteins. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:650–657. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evavold B D, Allen P M. Separation of IL-4 production from Th cell proliferation by an altered T cell receptor ligand. Science. 1991;252:1308–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.1833816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evavold B D, Sloan-Lancaster J, Allen P M. Tickling the TCR: selective T-cell functions stimulated by altered peptide ligands. Immunol Today. 1993;14:602–609. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evavold B D, Sloan-Lancaster J, Hsu B L, Allen P M. Separation of T helper 1 clone cytolysis from proliferation and lymphokine production using analog peptides. J Immunol. 1993;150:3131–3140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerlach J T, Diepolder H M, Jung M C, Gruener N H, Schraut W W, Zachoval R, Hoffmann R, Schirren C A, Santantonio T, Pape G R. Recurrence of hepatitis C virus after loss of virus-specific CD4(+) T-cell response in acute hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:933–941. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girgis L, Davis M M, de St Groth B F. The avidity spectrum of T cell receptor interactions accounts for T cell anergy in a double transgenic model. J Exp Med. 1999;189:265–278. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grakoui A, Bromley S K, Sumen C, Davis M M, Shaw A S, Allen P M, Dustin M L. The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grakoui A, VanDyk L F, Dowdy S F, Allen P M. Molecular basis for the lack of T cell proliferation induced by an altered peptide ligand. Int Immunol. 1998;10:969–979. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.7.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruber R, Reiter C, Riethmuller G. Triple immunofluorescence flow cytometry, using whole blood, of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes expressing CD45RO and CD45RA. J Immunol Methods. 1993;163:173–179. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90120-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruener N H, Lechner F, Jung M-C, Diepolder H M, Gerlach T, Lauer G, Walker B, Sullivan J, Phillips R, Pape G R, Klenerman P. Sustained dysfunction of antiviral CD8+ T lymphocytes after infection with hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2001;75:5550–5558. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5550-5558.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemmer B, Stefanova I, Vergelli M, Germain R N, Martin R. Relationships among TCR ligand potency, thresholds for effector function elicitation, and the quality of early signaling events in human T cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:5807–5814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itoh Y, Hemmer B, Martin R, Germain R N. Serial TCR engagement and down-modulation by peptide:MHC molecule ligands: relationship to the quality of individual TCR signaling events. J Immunol. 1999;162:2073–2080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kersh E N, Kersh G J, Allen P M. Partially phosphorylated T cell receptor zeta molecules can inhibit T cell activation. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1627–1636. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanzavecchia A, Lezzi G, Viola A. From TCR engagement to T cell activation: a kinetic view of T cell behavior. Cell. 1999;96:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80952-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lechner F, Wong D K, Dunbar P R, Chapman R, Chung R T, Dohrenwend P, Robbins G, Phillips R, Klenerman P, Walker B D. Analysis of successful immune responses in persons infected with hepatitis C virus. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1499–1512. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maloy K J, Burkhart C, Freer G, Rulicke T, Pircher H, Kono D H, Theofilopoulos A N, Ludewig B, Hoffmann-Rohrer U, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. Qualitative and quantitative requirements for CD4+ T cell-mediated antiviral protection. J Immunol. 1999;162:2867–2874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maloy K J, Burkhart C, Junt T M, Odermatt B, Oxenius A, Piali L, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. CD4(+) T cell subsets during virus infection. Protective capacity depends on effector cytokine secretion and on migratory capability. J Exp Med. 2000;191:2159–2170. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.12.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsushita S, Nishimura Y. Partial activation of human T cells by peptide analogs on live APC: induction of clonal anergy associated with protein tyrosine dephosphorylation. Hum Immunol. 1997;53:73–80. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(96)00273-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishimura Y, Chen Y Z, Kanai T, Yokomizo H, Matsuoka T, Matsushita S. Modification of human T-cell responses by altered peptide ligands: a new approach to antigen-specific modification. Intern Med. 1998;37:804–817. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.37.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oxenius A, Zinkernagel R M, Hengartner H. CD4+ T-cell induction and effector functions: a comparison of immunity against soluble antigens and viral infections. Adv Immunol. 1998;70:313–367. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padovan E, Casorati G, Dellabona P, Meyer S, Brockhaus M, Lanzavecchia A. Expression of two T cell receptor alpha chains: dual receptor T cells. Science. 1993;262:422–424. doi: 10.1126/science.8211163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penna A, Artini M, Cavalli A, Levrero M, Bertoletti A, Pilli M, Chisari F V, Rehermann B, Del Prete G, Fiaccadori F, Ferrari C. Long-lasting memory T cell responses following self-limited acute hepatitis B. J Clin Investig. 1996;98:1185–1194. doi: 10.1172/JCI118902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rehermann B, Chisari F V. Cell mediated immune response to the hepatitis C virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2000;242:299–325. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59605-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruppert J, Alexander J, Snoke K, Coggeshall M, Herbert E, McKenzie D, Grey H M, Sette A. Effect of T-cell receptor antagonism on interaction between T cells and antigen-presenting cells and on T-cell signaling events. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2671–2675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz R H. Models of T cell anergy: is there a common molecular mechanism? J Exp Med. 1996;184:1–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sette A, Alexander J, Grey H M. Interaction of antigenic peptides with MHC and TCR molecules. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;76:S168–S171. doi: 10.1016/s0090-1229(95)90108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sloan-Lancaster J, Evavold B D, Allen P M. Induction of T-cell anergy by altered T-cell-receptor ligand on live antigen-presenting cells. Nature. 1993;363:156–159. doi: 10.1038/363156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sloan-Lancaster J, Evavold B D, Allen P M. Th2 cell clonal anergy as a consequence of partial activation. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1195–1205. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sloan-Lancaster J, Shaw A S, Rothbard J B, Allen P M. Partial T cell signaling: altered phospho-zeta and lack of zap70 recruitment in APL-induced T cell anergy. Cell. 1994;79:913–922. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takaki A, Wiese M, Maertens G, Depla E, Seifert U, Liebetrau A, Miller J L, Manns M P, Rehermann B. Cellular immune responses persist and humoral responses decrease two decades after recovery from a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Nat Med. 2000;6:578–582. doi: 10.1038/75063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valitutti S, Muller S, Cella M, Padovan E, Lanzavecchia A. Serial triggering of many T-cell receptors by a few peptide-MHC complexes. Nature. 1995;375:148–151. doi: 10.1038/375148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valitutti S, Muller S, Dessing M, Lanzavecchia A. Different responses are elicited in cytotoxic T lymphocytes by different levels of T cell receptor occupancy. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1917–1921. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van der Meide P H, Dubbeld M, Schellekens H. Monoclonal antibodies to human immune interferon and their use in a sensitive solid-phase ELISA. J Immunol Methods. 1985;79:293–305. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(85)90109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Pouw Kraan T, Rensink I, Aarden L. Characterisation of monoclonal antibodies to human IL-4: application in an IL-4 ELISA and differential inhibition of IL-4 bioactivity on B cells and T cells. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1993;4:343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viola A, Lanzavecchia A. T cell activation determined by T cell receptor number and tunable thresholds. Science. 1996;273:104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viola A, Salio M, Tuosto L, Linkert S, Acuto O, Lanzavecchia A. Quantitative contribution of CD4 and CD8 to T cell antigen receptor serial triggering. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1775–1779. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang S Y E, Milford E, Hämmerling U, Dupont B. Description of the refernece panel of B lymphblastoid cell lines for factors of the HLA system: the B cell panel designed for the Tenth International Histocompatibility Workshop. In: Dupont B, editor. Immunobiology of HLA. New York, N.Y: Springer Verlag; 1989. pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]