Abstract

We analyzed length differences of eukaryotic, bacterial and archaeal proteins in relation to function, conservation and environmental factors. Comparing Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes, we found that the greater length of eukaryotic proteins is pervasive over all functional categories and involves the vast majority of protein families. The magnitude of these differences suggests that the evolution of eukaryotic proteins was influenced by processes of fusion of single-function proteins into extended multi-functional and multi-domain proteins. Comparing Bacteria and Archaea, we determined that the small but significant length difference observed between their proteins results from a combination of three factors: (i) bacterial proteomes include a greater proportion than archaeal proteomes of longer proteins involved in metabolism or cellular processes, (ii) within most functional classes, protein families unique to Bacteria are generally longer than protein families unique to Archaea and (iii) within the same protein family, homologs from Bacteria tend to be longer than the corresponding homologs from Archaea. These differences are interpreted with respect to evolutionary trends and prevailing environmental conditions within the two prokaryotic groups.

INTRODUCTION

Several studies reported that eukaryotic proteins are, on average, significantly longer than prokaryotic proteins and that, among Prokaryotes, bacterial proteins tend to be longer than archaeal proteins (1–6). As expected, these global relations do not always apply to individual protein families [see e.g. (7) for contrasting length relations of homologous families of membrane transport proteins]. It was also observed that the most conserved, functionally essential and/or highly expressed proteins tend to be longer (8–11). Biological events of diverse significance may be at the origin of the observed overall differences. A greater fraction of conserved, functionally important proteins in some proteomes could, for example, fully explain observed differences in protein lengths. Also, because proteins from different families and different functional classes have different lengths, an overall difference in protein length may reflect the variable proteome composition of different organisms (see Results). Finally, different criteria of genome annotation may affect the overall average length of the proteins in different organisms, as suggested for the overall small length difference observed between bacterial and archaeal proteins (4).

To investigate the role of conservation, functional specificities, annotation criteria and other factors in determining the average protein size in eukaryotic and prokaryotic species, we have analyzed the length of proteins from different classes of function and conservation. We were guided by the following questions: (i) are there differences in protein length among well-characterized proteins? (ii) do protein length differences appear in most or only in special functional classes of proteins? (iii) are differences in length due to proteins unique to each phylum or do they appear among proteins conserved between different phyla? (iv) do protein lengths correlate with environmental conditions and life styles? Our analyses confirmed the broad difference in length between eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteins. We were also able to conclude that the small overall length difference observed between bacterial and archaeal proteins is biologically significant and results from different evolutionary events and ecological conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteomes

We examined proteomes from 5 eukaryotic species, 16 archaeal species and 67 bacterial species (Table 1). For human sequences, we used the Ensembl genome database (12) Release 29.35b collection of ‘known and new’ proteins based on the NCBI 35 assembly of the human genome. These proteomes contained 104 394 eukaryotic proteins, 37 141 archaeal proteins and 191 518 bacterial proteins. Protein lengths were compared with respect to taxonomic, functional and ecological classes.

Table 1.

Proteomic collections

| Species | Abbreviation | |

|---|---|---|

| Eukaryota | Homo sapiensa | HUMAN |

| Drosophila melanogaster | DROME | |

| Caenorhabditis elegansa | CAEEL | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | YEAST | |

| Arabidopsis thalianaa | ARATH | |

| Euryarchaeota | Pyrococcus abyssi | PYRAB |

| Pyrococcus horikoshii | PYRHO | |

| Pyrococcus furiosus | PYRFU | |

| Archaeoglobus fulgidus | ARCFU | |

| Thermoplasma acidophilum | THEAC | |

| Thermoplasma volcanium | THEVO | |

| Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus | METTH | |

| Methanococcus jannaschii | METJA | |

| Methanosarcina acetivoransa | METAC | |

| Methanosarcina mazeia | METMA | |

| Methanopyrus kandleria | METKA | |

| Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 | HALN1 | |

| Crenarchaeota | Aeropyrum pernix | AERPE |

| Pyrobaculum aerophiluma | PYRAE | |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus | SULSO | |

| Sulfolobus tokodaii | SULTO | |

| γ-Proteobacteria | Escherichia coli K12 | ECOLI |

| Salmonella typhimurium | SALTY | |

| Salmonella enterica | SALTI | |

| Yersinia pestis CO92 | YERPE | |

| Shigella flexneria | SHIFL | |

| Wigglesworthia brevipalpisa | WIGBR | |

| Buchnera sp. APS | BUCAI | |

| Buchnera aphidicolaa | BUCAP | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | HAEIN | |

| Pasteurella multocida | PASMU | |

| Xanthomonas campestrisa | XANCP | |

| Xanthomonas axonopodisa | XANAC | |

| Xylella fastidiosa | XYLFA | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | PSEAE | |

| Vibrio cholerae | VIBCH | |

| Shewanella oneidensisa | SHEON | |

| β-Proteobacteria | Neisseria meningitides MC58 | NEIMB |

| Ralstonia solanacearuma | RALSO | |

| α-Proteobacteria | Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 Cereon | AGRT5 |

| Mesorhizobium loti | RHILO | |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti | RHIME | |

| Brucella melitensisa | BRUME | |

| Brucella suisa | BRUSU | |

| Caulobacter crescentus | CAUCR | |

| Rickettsia prowazekii | RICPR | |

| Rickettsia conorii | RICCN | |

| ɛ-Proteobacteria | Helicobacter pylori 26 695 | HELPY |

| Campylobacter jejuni | CAMJE | |

| Actinobacteria | Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37 Rv | MYCTU |

| Mycobacterium leprae | MYCLE | |

| Streptomyces coelicolora | STRCO | |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | CORGL | |

| Corynebacterium efficiensa | COREF | |

| Bifidobacterium longuma | BIFLO | |

| Firmicutes | Oceanobacillus iheyensisa | OCEIH |

| Bacillus subtilis | BACSU | |

| Bacillus halodurans | BACHD | |

| Staphylococcus aureus N315 | STAAN | |

| Listeria innocua | LISIN | |

| Listeria monocytogenes | LISMO | |

| Lactococcus lactis | LACLA | |

| Streptococcus agalactiae 2603 V/Ra | STRA5 | |

| Streptococcus mutansa | STRMU | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae TIGR4 | STRPN | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes M1 | STRPY | |

| Clostridium acetobutylicum | CLOAB | |

| Clostridium perfringensa | CLOPE | |

| Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensisa | THETN | |

| Ureaplasma urealiticum | UREPA | |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | MYCGE | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | MYCPN | |

| Mycoplasma pulmonis | MYCPU | |

| Mycoplasma penetransa | MYCPE | |

| Fusobacterium nucleatuma | FUSNN | |

| Cyanobacteria | Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | SYNY3 |

| Nostoc sp. PCC 7120b | ANASP | |

| Thermosynechococcus elongatusa | SYNEL | |

| Chlamydiae | Chlamydia trachomatis | CHLTR |

| Chlamydia muridarum | CHLMU | |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae CWL029 | CHLPN | |

| Spyrochaetes | Borrelia burgdorferi | BORBU |

| Treponema pallidum | TREPA | |

| Leptospira interrogansa | LEPIN | |

| Others | Deinococcus radiodurans | DEIRA |

| Chlorobium tepiduma | CHLTE | |

| Thermotoga maritima | THEMA | |

| Aquifex aeolicus | AQUAE |

aProteins from these species are not classified in the COG database and are excluded from the functional group analyses.

bThe COG classification of proteins from this species does not follow the standard coding and has been excluded from the COG analyses.

Datasets of selected proteins

We evaluated results using the set of proteins classified in the COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins) database (13,14) and the set of genomic proteins included in the Pfam (15–17) database of functional/structural domain alignments verified by human intervention (Pfam-A). The COG database classifies orthologous proteins in functional groups. At the onset of this study, classification of proteins into COGs was available for 2 eukaryotic proteomes (yeast and Drosophila melanogaster), 12 archaeal proteomes and 44 bacterial proteomes (Tables 1 and 2). COG data were obtained for prokaryotic organisms and yeast from the corresponding tables (*.ptt) available from the NCBI genomes ftp site (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes). Data for D.melanogaster were obtained from the classification table available at the COG website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG). All proteomes included in our analysis are also represented in the Pfam-A database.

Table 2.

Median protein lengths in eukaryotic, bacterial and archaeal organisms

| Speciesa | All species | Classified in COG | Classified in Pfam-A | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numberb | Medianc | Numberb | Medianc | Numberb | Medianc | |

| Eukarya | 104 394 | 361 | 5177 | 471 | 71 584 | 419 |

| HUMAN | 33 869 | 375 | – | – | 21 686 | 416 |

| DROME | 14 226 | 373 | 3092 | 492 | 13 091 | 475 |

| CAEEL | 21 124 | 344 | – | – | 13 316 | 391 |

| YEAST | 6315 | 379 | 2085 | 438 | 3953 | 448 |

| ARATH | 28 860 | 356 | – | – | 19 538 | 407 |

| Bacteria | 191 541 | 267 | 83 513 | 304 | 131 915 | 306 |

| ECOLI | 4289 | 278 | 3289 | 309 | 3483 | 303 |

| SALTY | 4553 | 271 | 3408 | 303 | 3527 | 300 |

| SALTI | 4767 | 253 | 3258 | 300 | 3118 | 300 |

| YERPE | 4083 | 268 | 2991 | 299 | 3003 | 304 |

| SHIFL | 4180 | 261 | – | – | 2613 | 304 |

| WIGBR | 654 | 268 | – | – | 571 | 291 |

| BUCAI | 574 | 282 | 558 | 284 | 544 | 285 |

| BUCAP | 545 | 279 | – | – | 536 | 285 |

| HAEIN | 1709 | 262 | 1470 | 286 | 750 | 314 |

| PASMU | 2014 | 286 | 1740 | 302 | 780 | 289 |

| XANCP | 4181 | 291 | – | – | 2976 | 325 |

| XANAC | 4312 | 286 | – | – | 3056 | 326 |

| XYLFA | 2832 | 201 | 1549 | 305 | 1544 | 305 |

| PSEAE | 5565 | 291 | 4355 | 310 | 4309 | 309 |

| VIBCH | 3828 | 259 | 2794 | 315 | 2731 | 312 |

| Chromosome 1 | 2736 | 273 | 2133 | 314 | ||

| Chromosome 2 | 1092 | 225 | 661 | 316 | ||

| SHEON | 4778 | 245 | – | – | 2913 | 308 |

| NEIMB | 2025 | 239 | 1448 | 291 | 1310 | 305 |

| RALSO | 5116 | 276 | – | – | 3518 | 310 |

| Chromosome 1 | 3440 | 271 | ||||

| Chromosome 2 | 1676 | 296 | ||||

| AGRT5 | 5402 | 280 | 3984 | 316 | 4062 | 307 |

| Circular chr. | 2785 | 258 | 2098 | 305 | ||

| Linear chr. | 1876 | 302 | 1424 | 329 | ||

| Plasmids | 741 | 273 | 462 | 316 | ||

| RHILO | 7275 | 269 | 5184 | 305 | 5107 | 303 |

| Chromosome | 6746 | 270 | 4888 | 304 | ||

| Plasmids | 529 | 243 | 296 | 327 | ||

| RHIME | 6205 | 281 | 4614 | 312 | 4669 | 308 |

| Chromosome | 3341 | 276 | 2602 | 302 | ||

| Plasmid A | 1294 | 265 | 890 | 310 | ||

| Plasmid B | 1570 | 303 | 1122 | 330 | ||

| BRUME | 3198 | 263 | – | – | 2322 | 300 |

| Chromosome 1 | 2059 | 252 | ||||

| Chromosome 2 | 1139 | 279 | ||||

| BRUSU | 3264 | 254 | – | – | 2351 | 301 |

| Chromosome 1 | 2116 | 239 | ||||

| Chromosome 2 | 1148 | 278 | ||||

| CAUCR | 3737 | 275 | 2551 | 317 | 2686 | 312 |

| RICPR | 834 | 283 | 687 | 295 | 672 | 299 |

| RICCN | 1374 | 173 | 861 | 247 | 769 | 264 |

| HELPY | 1566 | 266 | 1083 | 303 | 1052 | 315 |

| CAMJE | 1634 | 268 | 1309 | 294 | 1197 | 298 |

| MYCTU | 3918 | 287 | 2554 | 322 | 2213 | 326 |

| MYCLE | 1605 | 282 | 1145 | 326 | 1138 | 324 |

| STRCO | 7897 | 278 | – | – | 5330 | 317 |

| CORGL | 2993 | 275 | 1954 | 307 | 1985 | 314 |

| COREF | 2950 | 287 | – | – | 1961 | 323 |

| BIFLO | 1729 | 321 | – | – | 1286 | 341 |

| OCEIH | 3496 | 261 | – | – | 2583 | 295 |

| BACSU | 4100 | 256 | 2818 | 298 | 2974 | 297 |

| BACHD | 4066 | 261 | 2838 | 303 | 2916 | 300 |

| STAAN | 2625 | 257 | 1801 | 300 | 1542 | 293 |

| LISIN | 3043 | 255 | 2176 | 289 | 2234 | 291 |

| LISMO | 2846 | 267 | 2206 | 289 | 2211 | 292 |

| LACLA | 2266 | 251 | 1602 | 288 | 1690 | 281 |

| STRA5 | 2124 | 254 | – | – | 1480 | 290 |

| STRMU | 1960 | 250 | – | – | 1445 | 282 |

| STRPN | 2043 | 243 | 1465 | 287 | 1409 | 291 |

| STRPY | 1696 | 263 | 1178 | 294 | 1159 | 299 |

| CLOAB | 3848 | 262 | 2487 | 298 | 2634 | 299 |

| CLOPE | 2723 | 268 | – | – | 1997 | 303 |

| THETN | 2588 | 269 | – | – | 1903 | 306 |

| UREPA | 614 | 286 | 409 | 298 | 395 | 303 |

| MYCGE | 484 | 292 | 384 | 292 | 375 | 304 |

| MYCPN | 677 | 286 | 407 | 299 | 507 | 299 |

| MYCPU | 782 | 297 | 489 | 302 | 498 | 320 |

| MYCPE | 1037 | 304 | – | – | 664 | 315 |

| FUSNN | 2067 | 261 | – | – | 1432 | 303 |

| SYNY3 | 3169 | 274 | 2141 | 318 | 2344 | 306 |

| ANASP | 6129 | 256 | – | – | 3600 | 320 |

| SYNEL | 2475 | 272 | – | – | 1759 | 315 |

| CHLTR | 894 | 289 | 615 | 316 | 639 | 327 |

| CHLMU | 916 | 290 | 644 | 321 | 641 | 330 |

| CHLPN | 1052 | 289 | 646 | 324 | 716 | 333 |

| BORBU | 1637 | 220 | 635 | 318 | 981 | 265 |

| Chromosome | 850 | 286 | – | – | ||

| Plasmids | 787 | 179 | – | – | ||

| TREPA | 1031 | 293 | 708 | 331 | 691 | 337 |

| LEPIN | 4727 | 207 | – | – | 2243 | 309 |

| Chromosome 1 | 4360 | 206 | ||||

| Chromosome 2 | 367 | 223 | ||||

| DEIRA | 3182 | 264 | 2249 | 303 | 2050 | 307 |

| Chromosome 1 | 2629 | 257 | 1873 | 294 | ||

| Chromosome 2 | 368 | 304 | 265 | 347 | ||

| Plasmids | 185 | 303 | 111 | 336 | ||

| CHLTE | 2252 | 239 | – | – | 1431 | 311 |

| THEMA | 1846 | 284 | 1509 | 303 | 1459 | 304 |

| AQUAE | 1560 | 272 | 1321 | 291 | 1231 | 297 |

| Archaea | 37 141 | 247 | 18 219 | 283 | 24 067 | 288 |

| PYRAB | 1765 | 265 | 1450 | 281 | 1407 | 282 |

| PYRHO | 1801 | 257 | 1398 | 283 | 1312 | 285 |

| PYRFU | 2065 | 253 | 1627 | 273 | 1477 | 281 |

| ARCFU | 2420 | 243 | 1887 | 270 | 1720 | 276 |

| THEAC | 1482 | 269 | 1233 | 293 | 1083 | 301 |

| THEVO | 1499 | 259 | 1247 | 287 | 1074 | 304 |

| METTH | 1869 | 242 | 1382 | 273 | 1325 | 277 |

| METJA | 1770 | 241 | 1298 | 266 | 1260 | 272 |

| METAC | 4540 | 256 | – | – | 2677 | 306 |

| METMA | 3371 | 255 | – | – | 2141 | 294 |

| METKA | 1691 | 257 | – | – | 1067 | 272 |

| HALN1 | 2622 | 242 | 1746 | 297 | 1471 | 303 |

| AERPE | 1840 | 239 | 1191 | 293 | 1067 | 301 |

| PYRAE | 2603 | 208 | – | – | 1411 | 267 |

| SULSO | 2977 | 251 | 1983 | 294 | 1917 | 293 |

| SULTO | 2826 | 226 | 1777 | 284 | 1658 | 279 |

Statistical significance evaluations

We compared median protein lengths (the midpoint of all lengths arranged in order of magnitude) rather than average lengths between two sets of proteins to reduce the effect of outliers. The statistical significance of the difference in median length between the proteins of two sets was evaluated estimating the distribution of median length differences between samples created by randomly redistributing all sequences from the two sets into two new sets of the original sizes. For each determination, from 200 to 1000 independent data shufflings were implemented. We highlight the differences in median length observed in <1% of all shuffled samples (P < 0.01, boldfaced in the tables) and observed in the range 1–10% of all shuffled samples (0.01 ≤ P < 0.1, underlined in the tables). The significance of asymmetric counts of longer or shorter protein families comparing two evolutionary groups was evaluated on the basis of exact binomial probabilities or of their normal approximation.

RESULTS

We compared medians from the protein length distributions of eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteomes (Table 1) from the sets of proteins characterized in COGs (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) (13,14) or included in Pfam-A (15–17) alignments. We then used the COG database classification to investigate median protein length relations separately for different functional classes of proteins, among protein groups unique to Eukarya, Bacteria and Archaea and among protein groups shared by Bacteria and Archaea or Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes. We then compared proteins included in the Pfam database to evaluate the influence of domain structure in determining protein length differences between domains. Finally, we evaluated the influence of growth temperature on protein length.

Protein lengths across proteomes

Median protein lengths in all species and for the collections of 5 eukaryotic species, 16 archaeal species and 67 bacterial species are shown in Table 2. For prokaryotic organisms, the median lengths of individual chromosomes and of collections of plasmids are also indicated. The median length of the proteins annotated among Eukaryotes (361 amino acids) is much higher than in Bacteria (267 amino acids) and this in turn is higher than in Archaea (247 amino acids). These differences are significant (P < 0.001) and are in agreement with the previously published results (1,2,5). The median difference in length between Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes is unambiguous, whereas among Prokaryotes the distributions of median lengths of individual bacterial and archaeal species overlap. The median lengths of bacterial species that are higher than the median archaeal length are underlined in Table 2.

In evaluating the distribution of protein lengths in eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteomes, a major concern is the reliability of the dataset. In fact, eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteomes contain a large fraction of proteins of uncertain determination (14). Proteins described as putative, hypothetical, predicted, poorly characterized, uncharacterized or unknown in genome annotations of Eukaryotes, Archaea and Bacteria constitute 56.1, 51.5 and 51.7%, respectively, of all annotated proteins. A more reliable set of proteins is provided by the COG database (13,14), which identifies proteins conserved in different organisms and characterizes them in functional classes, and by the Pfam database (15–17) of well-curated alignments (Pfam-A), which characterizes proteins by the presence of conserved domains. The COG database provides a reasonable compromise between reliability of annotation and size of dataset. Although based on automated procedures, it has the advantage of using consistent criteria with no obvious biases over a large set of organisms. The Pfam-A database provides the advantage of human supervision. COG orthologs comprise 25.0% of all annotated proteins from DROME and YEAST (see Table 1 for abbreviations), 72.5% of all proteins from bacterial proteomes and 73.1% of all proteins from archaeal proteomes, whereas proteins in Pfam including domains verified by human intervention (Pfam-A) comprise 68.6% of all eukaryotic proteins, 68.9% of all bacterial proteins and 64.8% of all archaeal proteins. The median lengths of proteins that are classified in COG or in Pfam-A (Table 2) confirm the significant difference between the three domains observed for complete proteomes, yielding Eukaryotes ≫ Bacteria > Archaea.

Protein length differences in functional classes

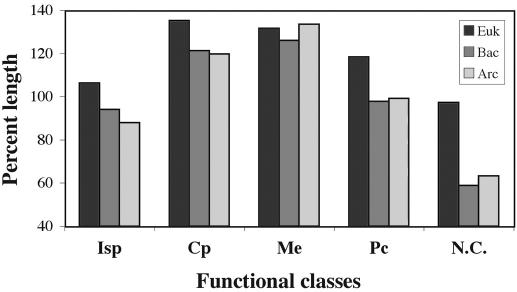

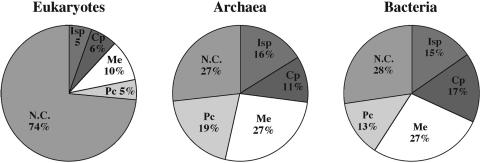

We analyzed protein lengths within functional classes of proteins defined in the COG database (Table 3). We noticed (Figure 1) that in all three phylogenetic domains (Eukarya, Bacteria and Archaea) proteins involved in the broad functional classes of cellular processes and metabolism are the longest in median value, followed by the sets of poorly characterized proteins, by the group of proteins involved in information storage and processing and finally by the non-conserved proteins that are not classified in the COG database. The representation of these broad functional classes in Eukarya, Bacteria or Archaea is shown in Figure 2. Among eukaryotic proteins, only those with prokaryotic homologs are classified in the COG database. These comprise only 26% of the eukaryotic proteomes, whereas 74% of the eukaryotic proteomes (yeast and Drosophila) are composed of relatively shorter proteins not found in Prokaryotes. Among Prokaryotes, the long proteins functioning in cellular processes are present in higher proportions in Bacteria than in Archaea, whereas Archaea have a higher proportion of the shorter, poorly characterized proteins (Figure 2).

Table 3.

COG functional classification

| Information storage and processing (Isp) | |

| J | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| K | Transcription |

| L | DNA replication, recombination and repair |

| Cellular processes (Cp) | |

| D | Cell division and chromosome partitioning |

| O | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| M | Cell envelope biogenesis, outer membrane |

| N | Cell motility and secretion |

| P | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| T | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| Metabolism (Me) | |

| C | Energy production and conversion |

| G | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | Coenzyme metabolism |

| I | Lipid metabolism |

| Q | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| Poorly characterized (Pc) | |

| R | General function prediction only |

| S | Function unknown |

Figure 1.

Relative median length of proteins within major functional classes in Eukaryotes (Euk), Bacteria (Bac) and Archaea (Arc). Lengths are normalized by the global median length within each phylum. Major functional classes follow the definition in COG (see also Table 3): Isp, information storage and processes; Cp, cellular processes; Me, metabolism; Pc, poorly characterized. N.C. signifies proteins not classified in the COG database.

Figure 2.

Representation in eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteomes of proteins belonging to the major functional classes. Isp, information storage and processes; Cp, cellular processes; Me, metabolism; Pc, poorly characterized. N.C. signifies proteins not classified in the COG database.

Median protein lengths within all COG functional classes are shown in Table 4. Eukaryotic proteins feature a median length greater than prokaryotic proteins for every functional class. The greatest length difference, of ∼400 amino acids, is observed among proteins functioning in DNA replication, recombination and repair. For most other functional classes, differences in length are in the approximate range of 100–200 amino acids. The shortest eukaryotic proteins are those not classified in the COG database. Even these, however, are >200 amino acids longer than the corresponding prokaryotic proteins and are also longer than prokaryotic proteins from each major functional class (with overall median length ∼300 amino acids).

Table 4.

Median protein lengths in COG functional classes

| COG classa | Tot grpb | All COGs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUK | BAC | ARC | p(ΔBA)e | ||||||||

| Grpb | Seqc | Medd | Grpb | Seqc | Medd | Grpb | Seqc | Medd | |||

| Isp | 541 | 258 | 1157 | 399 | 434 | 17 621 | 252 | 345 | 4034 | 218 | 0.000 |

| J | 220 | 175 | 623 | 296 | 155 | 6110 | 208 | 155 | 1736 | 205 | 0.231 |

| K | 139 | 31 | 295 | 444 | 114 | 6122 | 240 | 75 | 1027 | 156 | 0.000 |

| L | 188 | 55 | 318 | 723 | 167 | 5389 | 315 | 116 | 1271 | 321 | 0.309 |

| Cp | 689 | 161 | 1355 | 507 | 667 | 19 275 | 325 | 279 | 2720 | 297 | 0.000 |

| D | 35 | 8 | 33 | 439 | 34 | 936 | 346 | 12 | 181 | 282 | 0.000 |

| O | 116 | 47 | 421 | 370 | 110 | 3167 | 270 | 62 | 584 | 246 | 0.012 |

| M | 166 | 24 | 82 | 449 | 166 | 4713 | 355 | 49 | 550 | 341 | 0.011 |

| N | 131 | 13 | 43 | 508 | 121 | 3194 | 320 | 38 | 368 | 292 | 0.077 |

| P | 167 | 50 | 338 | 538 | 164 | 4014 | 314 | 91 | 732 | 294 | 0.003 |

| T | 89 | 21 | 439 | 605 | 87 | 3251 | 323 | 28 | 305 | 253 | 0.001 |

| Me | 1005 | 438 | 2034 | 494 | 970 | 31 258 | 338 | 640 | 6625 | 331 | 0.000 |

| C | 228 | 85 | 377 | 480 | 210 | 5149 | 366 | 160 | 1620 | 346 | 0.000 |

| G | 178 | 61 | 456 | 519 | 175 | 6478 | 371 | 84 | 929 | 372 | 0.506 |

| E | 240 | 117 | 577 | 515 | 227 | 8268 | 356 | 163 | 1632 | 353 | 0.240 |

| F | 89 | 61 | 186 | 376 | 82 | 2396 | 274 | 65 | 586 | 244 | 0.002 |

| H | 147 | 73 | 184 | 393 | 137 | 3434 | 307 | 106 | 911 | 283 | 0.000 |

| I | 80 | 47 | 240 | 518 | 78 | 2658 | 313 | 41 | 515 | 360 | 0.000 |

| Q | 68 | 15 | 225 | 505 | 63 | 2875 | 294 | 22 | 432 | 261 | 0.000 |

| Pc | 1372 | 207 | 1057 | 444 | 1167 | 15 359 | 262 | 645 | 4840 | 246 | 0.000 |

| R | 501 | 146 | 962 | 459 | 423 | 9003 | 291 | 282 | 2806 | 274 | 0.000 |

| S | 897 | 64 | 95 | 318 | 764 | 6355 | 210 | 368 | 2035 | 202 | 0.018 |

| Chr | 2201 | 845 | 4791 | 481 | 2051 | 68 154 | 315 | 1261 | 13 379 | 299 | 0.000 |

| All | 3482 | 1027 | 5177 | 471 | 3162 | 83 513 | 304 | 1894 | 18 219 | 283 | 0.000 |

| N.C. | n.a. | n.a. | 15 492 | 365 | n.a. | 31 739 | 158 | n.a. | 6717 | 157 | 0.342 |

aChr = Isp + Cp + Me; All = Chr + Pc; N.C. = Not classified in COGs. See Table 3 for other class symbols.

bNumber of COG groups within each class.

cNumber of sequences.

dMedian length.

eProbability of the median length difference observed between bacterial and archaeal sequences.

Table 4 also shows that the overall relation between bacterial and archaeal proteins (bacterial longer than archaeal) is also valid within most individual functional classes. In Table 4, significant (P ≤ 0.01) length differences between bacterial and archaeal medians are shown in boldface and less significant differences (0.01 < P ≤ 0.10) are underlined. The most pronounced differences occurred for proteins functioning in transcription (240 amino acids median in Bacteria versus 156 amino acids median in Archaea), in signal transduction (323 amino acids versus 253 amino acids), and in cell division and chromosome partitioning (346 amino acids versus 282 amino acids). Smaller differences occurred for proteins in nucleotide transport and metabolism (274 amino acids versus 244 amino acids) or in secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport and catabolism (294 amino acids versus 261 amino acids). Proteins longer in Bacteria than in Archaea also stand out in most of the other functional classes, with median length differences in the range of 5–20 amino acids. Equivalent lengths were only observed in the functional classes of translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, DNA replication, recombination and repair, amino acid transport and carbohydrate transport and metabolism. A reverse relation, with archaeal proteins longer than bacterial proteins, was only found for proteins involved in lipid metabolism (313 amino acids in Bacteria versus 360 amino acids in Archaea).

The comparison of well-characterized proteins from Bacteria and Archaea confirms the biological significance of the overall length differences between bacterial and archaeal proteins. In this respect, it is interesting to emphasize that no length differences were observed for proteins that are not classified in COGs (Table 4, 157 amino acids in Archaea and 158 amino acids in Bacteria). This result, together with the observation that non-classified proteins are equally frequent in Bacteria and Archaea (Figure 2), indicates that the length difference between bacterial and archaeal proteins cannot be ascribed to over-annotation of short open reading frames in Archaea as previously suggested (4).

Length differences of proteins unique to Eukarya, Bacteria or Archaea

A relevant question is whether the significant protein length differences observed in most functional classes are due to proteins unique to each class of organisms or are also present among homologs conserved between Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes or between Archaea and Bacteria. Here, we compared the lengths of proteins unique to each phylogenetic group. As mentioned before, in Eukaryotes proteins without prokaryotic orthologs were not classified in the COG database. These were shorter than those classified in COGs (medians 365 amino acids versus 471 amino acids) but still longer than the median bacterial (267 amino acids) or archaeal proteins (247 amino acids). Among Prokaryotes, 1588 families of protein orthologs have representatives only in Bacteria and 320 families are unique to Archaea (Table 5). Unique families of proteins comprise 23.9 and 10.9% of the bacterial and archaeal proteomes, respectively. Table 5 shows a substantial length difference (73 amino acids) between proteins unique to Bacteria (median 275 amino acids) and proteins unique to Archaea (median 202 amino acids). This difference was emphasized among well-characterized proteins involved in information storage and processing (Isp), metabolism (Me) or cellular processes (Cp), which were 58.6% longer in Bacteria than in Archaea (295 amino acids versus 186 amino acids). The overall length difference between unique bacterial and archaeal proteins is determined by two factors: (i) within all major functional classes of characterized proteins, unique bacterial proteins are ∼40% longer than unique archaeal proteins and (ii) unique bacterial proteins are mostly (73%) represented by metabolic proteins (Me) or proteins involved in cellular processes (Cp), which tend to be longer in all organisms (Figure 1), whereas unique archaeal proteins are mostly (79%) represented by generally shorter proteins involved in information storage and processing (Isp).

Table 5.

Median lengths of proteins unique to Bacteria or Archaea among Prokaryotesa

| COG class | BAC | ARC | p(Δ) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grp | Seq | Med | Grp | Seq | Med | ||

| Isp | 192 | 5771 | 240 | 103 | 1161 | 172 | 0.000 |

| J | 61 | 2178 | 166 | 61 | 653 | 145 | 0.009 |

| K | 62 | 1990 | 256 | 23 | 281 | 136 | 0.000 |

| L | 71 | 1607 | 276 | 20 | 227 | 369 | 0.000 |

| Cp | 406 | 8432 | 312 | 18 | 165 | 219 | 0.000 |

| D | 23 | 464 | 384 | 1 | 2 | 253 | 0.516 |

| O | 53 | 984 | 234 | 5 | 39 | 368 | 0.008 |

| M | 117 | 2492 | 348 | 0 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| N | 92 | 1990 | 269 | 9 | 99 | 197 | 0.000 |

| P | 74 | 1061 | 386 | 1 | 8 | 376 | 0.611 |

| T | 61 | 1447 | 254 | 2 | 17 | 287 | 0.402 |

| Me | 359 | 6757 | 331 | 29 | 145 | 237 | 0.000 |

| C | 64 | 1009 | 383 | 14 | 58 | 312 | 0.122 |

| G | 91 | 2010 | 339 | 0 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| E | 70 | 1062 | 389 | 6 | 25 | 273 | 0.000 |

| F | 20 | 440 | 214 | 3 | 29 | 189 | 0.053 |

| H | 36 | 862 | 286 | 5 | 27 | 181 | 0.000 |

| I | 37 | 927 | 300 | 0 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Q | 42 | 447 | 374 | 1 | 6 | 263 | 0.120 |

| Pc | 698 | 6744 | 228 | 176 | 1246 | 224 | 0.221 |

| R | 193 | 2520 | 284 | 52 | 471 | 273 | 0.105 |

| S | 524 | 4247 | 196 | 128 | 776 | 191 | 0.215 |

| Chr | 940 | 20 945 | 295 | 150 | 1471 | 186 | 0.000 |

| All | 1588 | 27 570 | 275 | 320 | 2709 | 202 | 0.000 |

Length differences of conserved proteins

We distinguished eukaryotic proteins with prokaryotic orthologs between those with only archaeal orthologs, those with only bacterial orthologs and those conserved in all three domains (see Supplementary Table S1). About 79% of the eukaryotic sequences with orthologs in Archaea but absent from Bacteria are involved in information storage and processing (Isp) and among these 60% function in translation. In contrast, sequences with orthologs present in Bacteria but absent from Archaea, or present in all three domains, are rather evenly distributed among functional classes, with a higher frequency (∼41%) of metabolic proteins (Me). In virtually all classes the median length of conserved eukaryotic proteins is significantly greater than the median length of the corresponding prokaryotic orthologs. Notably, eukaryotic proteins with bacterial orthologs are considerably longer (∼79%) than those with archaeal orthologs. This asymmetry applies to all four major functional categories (information storage and processing, cellular processes, metabolism, poorly characterized) and to most individual classes. The only exceptions are proteins functioning in post-translational modification, turnover and chaperoning and proteins functioning in transport and metabolism of inorganic ions.

We have shown that the overall length differences observed between bacterial and archaeal proteins are amplified among proteins unique to each of the two domains. It remains to be established whether length differences are also present among proteins conserved between Bacteria and Archaea. According to the COG database, 1574 families of orthologs are conserved between Bacteria and Archaea. These comprise 48.5 and 62.2% of the average bacterial and archaeal proteome, respectively. The results shown in Table 6 indicate that orthologs conserved between Bacteria and Archaea are also longer in Bacteria, with an overall significant length difference of 17 amino acids (compared with an overall length difference of 73 amino acids between unique proteins). Qualitatively similar length differences prevail within most functional groups of proteins.

Table 6.

Median lengths of orthologs shared by Bacteria and Archaeaa

| COG class | # Grp | BAC | ARC | p(Δ) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seq | Med | Seq | Med | |||

| Isp | 242 | 11 850 | 260 | 2873 | 246 | 0.001 |

| J | 94 | 3932 | 245 | 1083 | 255 | 0.105 |

| K | 52 | 4132 | 221 | 746 | 157 | 0.000 |

| L | 96 | 3782 | 336 | 1044 | 306 | 0.004 |

| Cp | 261 | 10 843 | 330 | 2555 | 302 | 0.000 |

| D | 11 | 472 | 318 | 179 | 283 | 0.021 |

| O | 57 | 2183 | 290 | 545 | 246 | 0.002 |

| M | 49 | 2221 | 359 | 550 | 341 | 0.000 |

| N | 29 | 1204 | 388 | 269 | 357 | 0.023 |

| P | 90 | 2953 | 302 | 724 | 293 | 0.058 |

| T | 26 | 1804 | 358 | 288 | 252 | 0.000 |

| Me | 611 | 24 501 | 340 | 6480 | 332 | 0.000 |

| C | 146 | 4140 | 364 | 1562 | 346 | 0.011 |

| G | 84 | 4468 | 390 | 929 | 372 | 0.020 |

| E | 157 | 7206 | 351 | 1607 | 354 | 0.312 |

| F | 62 | 1956 | 310 | 557 | 257 | 0.000 |

| H | 101 | 2572 | 312 | 884 | 285 | 0.000 |

| I | 41 | 1731 | 322 | 515 | 360 | 0.019 |

| Q | 21 | 2428 | 281 | 426 | 261 | 0.000 |

| Pc | 469 | 8614 | 281 | 3595 | 253 | 0.000 |

| R | 230 | 6483 | 294 | 2335 | 274 | 0.000 |

| S | 240 | 2108 | 234 | 1259 | 206 | 0.000 |

| Chr | 1111 | 47 209 | 321 | 11 908 | 311 | 0.000 |

| All | 1574 | 55 943 | 315 | 15 510 | 298 | 0.000 |

To determine whether these overall differences represent a trend common to most families or reflect strong asymmetries present in few families, we counted how many of the 1574 shared families of orthologs have a greater median length in Bacteria and how many are longer in Archaea. Table 7 shows that among all shared protein families almost twice as many (63.3%) involved longer sequences in Bacteria than in Archaea (boldface or underlined in Table 7 when the differences in counts have probability P ≤ 0.01 or 0.01 < P ≤ 0.10, respectively, see Materials and Methods). For comparison, 89.9% of 1027 protein families shared by Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes were longer in Eukaryotes (data not shown). Similar proportions (2:1) of longer bacterial proteins were observed within most functional categories. We also partitioned shared protein families by absolute length difference, i.e. distinguishing among all protein families those with an absolute length difference between bacterial and archaeal orthologs of <20 amino acids, in the range of 21–100 amino acids or >100 amino acids (Table 7). Remarkably, within each of these classes we observed similar proportions (2:1) of families with longer bacterial sequences. Similar results were obtained for a wide variety of other length intervals (data not shown). These results suggest that there are evolutionary pressures for proteins of different length in Archaea and Bacteria, acting both on protein families unique to each lineage and on proteins conserved between the two lineages. Among the latter, length differences seem both compatible with addition/deletion in different families of orthologs of small sequence element (e.g. <20 amino acids) or of entire structural domains (e.g. >100 amino acids).

Table 7.

Median length relations of orthologs conserved between Bacteria and Archaeaa

| COG class | Bacteria versus Archaea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Grp | Bacteria > Archaea | Archaea > Bacteria | |||

| # | % | # | % | ||

| Isp | 242 | 145 | 59.9 | 92 | 38.0 |

| J | 94 | 46 | 48.9 | 47 | 50.0 |

| K | 52 | 35 | 67.3 | 16 | 30.8 |

| L | 96 | 64 | 66.7 | 29 | 30.2 |

| Cp | 261 | 163 | 62.5 | 96 | 36.8 |

| D | 11 | 11 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| O | 57 | 34 | 59.6 | 23 | 40.4 |

| M | 49 | 33 | 67.3 | 15 | 30.6 |

| N | 29 | 16 | 55.2 | 12 | 41.4 |

| P | 90 | 50 | 55.6 | 40 | 44.4 |

| T | 26 | 20 | 76.9 | 6 | 23.1 |

| Met | 611 | 409 | 66.9 | 195 | 31.9 |

| C | 146 | 95 | 65.1 | 50 | 34.2 |

| G | 84 | 60 | 71.4 | 24 | 28.6 |

| E | 157 | 107 | 68.2 | 46 | 29.3 |

| F | 62 | 39 | 62.9 | 21 | 33.9 |

| H | 101 | 67 | 66.3 | 34 | 33.7 |

| I | 41 | 27 | 65.9 | 14 | 34.1 |

| Q | 21 | 15 | 71.4 | 6 | 28.6 |

| Pc | 469 | 284 | 60.6 | 178 | 38.0 |

| R | 230 | 145 | 63.0 | 81 | 35.2 |

| S | 240 | 140 | 58.3 | 97 | 40.4 |

| Chr | 1111 | 717 | 64.5 | 380 | 34.2 |

| All | 1574 | 997 | 63.3 | 556 | 35.3 |

| 1–20 amino acids | 750 | 469 | 62.5 | 281 | 37.5 |

| 21–100 amino acids | 567 | 366 | 64.6 | 201 | 35.4 |

| >100 amino acids | 246 | 162 | 65.9 | 74 | 34.1 |

Domain composition of eukaryotic, bacterial and archaeal proteins

To substantiate our speculations that the protein length relations between Eukarya, Archaea and Bacteria may be influenced by their composition in structural domains, we analyzed the domain composition of genomic proteins included in the Pfam-A database. In particular, we calculated the average number of domains per eukaryotic, bacterial or archaeal protein, and their median length. We repeated the analysis for domains classified in Pfam-A and for all domains classified in Pfam-A or Pfam-B (automatically generated). Table 8 shows that eukaryotic proteins tend to include substantially more domains per protein than bacterial proteins (2.16 versus 1.46 Pfam-A domains and 3.48 versus 2.09 Pfam-A+B domains, respectively). They also show that bacterial proteins tend to include marginally more domains than archaeal proteins (1.46 versus 1.39 Pfam-A and 2.09 versus 2.00 Pfam-A+B). The median length of each Pfam-A domain was substantially similar in the three phylogenetic groups (179–188 amino acids) but greater differences were observed including also Pfam-B domains, with domain lengths following the same overall ordering observed between proteins (eukaryotic domain 257 amino acids > bacterial domain 217 amino acids > archaeal domain 205 amino acids).

Table 8.

Structural/functional domains in eukaryotic, bacterial and archaeal proteomes

| Database | Domains | EUK | BAC | ARC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pfam-A | Total number | 154 979 | 192 680 | 33 372 |

| Mean number/seq. | 2.16 | 1.46 | 1.39 | |

| Median length/amino acids | 185 | 188 | 179 | |

| Pfam-A + Pfam-B | Total number | 249 163 | 275 630 | 48 060 |

| Mean number/seq. | 3.48 | 2.09 | 2.00 | |

| Median length/amino acids | 257 | 217 | 205 |

Protein length relations of mesophilic versus thermophilic Prokaryotes

Only 5 of the 67 bacterial proteomes in our collection are from thermophilic organisms: CHLTE [optimal growth temperature (OGT) 48°C], SYNEL (55°), THETN (75°C), THEMA (80°C) and AQUAE (96°C), of which only proteins from THEMA and AQUAE were classified in COGs. In contrast, only 3 of the 16 archaeal proteomes were from mesophilic organisms (HALN1, METAC and METMA), of which only proteins from HALN1 were classified in COGs. The archaeal thermophiles live under OGTs ranging from 60°C (THEAC and THEVO) to >100°C (PYRAB, PYRHO and PYRAE). Considering the disproportionate number of mesophilic organisms among Bacteria and the disproportionate number of thermophilic organisms among Archaea, the median protein length differences observed between Bacteria and Archaea may reflect differences between mesophiles and thermophiles. In the following analyses, we evaluated the relation of OGT with protein length. We then examined median protein lengths partitioning prokaryotic species into separate sets of bacterial mesophiles (BM, 62 species, 42 species for COG comparisons), archaeal mesophiles (AM, 3, 1), bacterial thermophiles (BT, 5, 2) and archaeal thermophiles (AT, 13, 11).

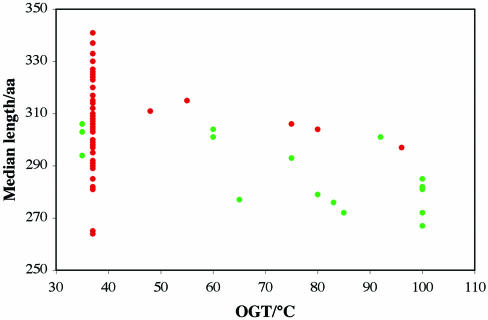

We compared the median protein length in a variety of datasets with the OGT of bacterial and archaeal organisms. In all comparisons we found a negative correlation of the protein length with OGT. The correlation was not significant for comparisons of all proteomic proteins (P = 0.239) and marginally significant for proteins classified in the COG database (P = 0.069). However, we found a highly significant correlation (P = 0.0018) for proteins classified in Pfam-A (Figure 3). Figure 3 also shows an overall tendency for proteins of bacterial thermophiles to be longer than proteins from archaeal thermophiles for all OGTs.

Figure 3.

Relation of median length of genomic proteins included in the Pfam-A database of curated alignments and OGT of the corresponding organism. Each point represents the median protein length within each bacterial (red) or archaeal (green) species.

In Table 9, we compared the overall median protein lengths among thermophiles or among mesophiles from groups of orthologs conserved between Bacteria and Archaea (Shared) and of orthologs unique to each of the two lineages (Unique). In Table 10, we counted the number of shared families that are longer in bacterial or archaeal species of similar thermophilicity (BM versus AM and BT versus AT) and, within the same domain, the number of protein families that are longer in thermophiles or mesophiles (BT versus BM and AT versus AM). Among conserved proteins, there is only a small, non-significant length difference (0.01 < P ≤ 0.10, underlined in Table 9) between proteins from bacterial and archaeal species of similar temperature preferences (Table 9). Consistently, among mesophiles or thermophiles, the number of shared orthologous groups that are longer in Bacteria or Archaea is equally distributed between the two groups (Table 10). In contrast, comparisons of mesophilic versus thermophilic species within Bacteria or within Archaea show in both domains significantly more orthologous groups longer in mesophiles compared with thermophiles (P ≤ 0.01, boldface in Table 10).

Table 9.

Median length of orthologous groups from mesophilic or thermophilic Prokaryotesa

| Type of ortholog | # of groups | Set I | Set II | P(Δ) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Seq | Med | Archaea | Seq | Med | |||

| Shared | 977 | BT | 2036 | 306 | AT | 10 664 | 298 | 0.071 |

| 860 | BM | 36 891 | 317 | AM | 1481 | 309 | 0.064 | |

| Unique | 465 831 | BT | 794 | 267 | AT | 5810 | 244 | 0.002 |

| 2 250 187 | BM | 43 791 | 294 | AM | 265 | 206 | 0.000 | |

a# of groups is the number of COG groups in each comparison (the two different numbers shown for comparisons of Unique orthologs correspond to the unique groups found in Bacteria and Archaea, respectively. Pairwise comparisons between bacterial thermophiles (BT), archaeal thermophiles (AT), bacterial mesophiles (BM) and archaeal mesophiles (AM). See text and footnote of Table 4 for other abbreviations.

Table 10.

Number of conserved orthologous groups longer in bacterial or archaeal thermophiles and mesophilesa

| Set I | Set II | # Grp | Set I > Set II | Set II > Set I | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | |||

| BT | AT | 977 | 484 | 49.5 | 478 | 48.9 |

| BM | AM | 860 | 411 | 47.8 | 435 | 50.6 |

| BM | BT | 1390 | 947 | 68.1 | 422 | 30.4 |

| AM | AT | 961 | 585 | 60.9 | 361 | 37.6 |

aSee text and footnote of Table 7 for abbreviations.

A different picture emerges comparing the median lengths of orthologous groups of proteins that are present only in Bacteria or only in Archaea of similar temperature preferences (Table 9, Unique). In contrast to shared proteins, proteins unique to Bacteria tend to be significantly longer than proteins unique to Archaea (P ≤ 0.01, boldface in Table 9) independently of temperature, following the ordering: bacterial mesophiles (294 amino acid median) > bacterial thermophiles (267 amino acid median) > archaeal thermophiles (244 amino acid median) > archaeal mesophile (206 amino acid median).

DISCUSSION

It has been consistently reported (1–7) that eukaryotic proteins are generally longer than bacterial proteins and these in turn are marginally longer than archaeal proteins. We have concluded that the overall protein length differences observed between Eukarya, Bacteria and Archaea represent a genuine trend among the three Domains involving most functional groups of proteins. Well-characterized eukaryotic proteins are ∼55% longer (median values) than bacterial proteins. COG groups showing the greatest length difference between eukaryote and prokaryote proteins are listed in Supplementary Table S2. These proteins span all functional groups, including membrane-associated, cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins. What can account for the difference in length between eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteins? A greater length of eukaryotic proteins may reflect upon the greater complexity of the eukaryotic cell compared with the prokaryotic cell. Our analyses confirm previous suggestions (5,8) that eukaryotic proteins have a strong tendency to fuse into multi-domain and multi-functional units. It has been proposed that eukaryotic proteins are expanded by the addition of sequence motifs or structural domains that act as functional regulators (2). Compared with prokaryotic proteins, it may also be more difficult for eukaryotic proteins to associate in a crowded cytoplasmic space partitioned by a complex array of compartments. Fusion of interacting single-function proteins into multi-domain units may facilitate the interaction between functional units and diminish the need to produce proteins in greater amounts to achieve appropriate concentrations of their complexes. It seems plausible that the acquisition of longer, multi-functional proteins in eukaryote organisms may have evolved concomitant with the acquisition of multi-exon proteins. However, we do not find that yeast genes, with relatively few introns (of which many are in ribosomal proteins), code for proteins that are shorter than in more intron-rich genomes.

In contrast to the substantial length difference between eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteins, the length difference between median bacterial and archaeal proteins is relatively small and has been described as an artifact of genome annotation (4). In fact, predicted uncharacterized proteins tend to be shorter than conserved, functionally characterized proteins (8–11) and the inclusion in proteome annotations of a high proportion of putative proteins could bias the overall protein length (4). However, we found that putative proteins in Bacteria and Archaea have similar lengths and comprise similar proportions of the bacterial and archaeal proteomes. In contrast, we found that well-characterized proteins from most functional categories are significantly longer in Bacteria than in Archaea.

Our analyses suggest that differences in environmental temperature may govern the length biases observed between bacterial (mostly mesophilic) and archaeal (mostly thermophilic) orthologs. The small reduction in the median length of archaeal versus bacterial orthologs (median 17 amino acids) is consistent with the length reduction of disordered loops or N-terminal and C-terminal tails that presumably confers extra stability to proteins subject to high temperatures (18–23).

Although the differences in median length between bacterial and archaeal homologs are relatively small, length differences within specific orthologous groups suggest that a substantial proportion of bacterial orthologs differ from archaeal orthologs by the addition of entire structural domains. Groups of orthologs with the greatest difference between bacterial and archaeal median protein lengths are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Insertion or deletion of domains is common among bacterial or archaeal orthologs, as attested to by the wide range of protein lengths observed within many groups of orthologous sequences. In fact, in ∼70% of all prokaryotic groups of orthologs, bacterial or archaeal sequences span length differences of >100 amino acids. Our results suggest that bacterial proteins are more prone than archaeal proteins to domain-fusion.

We speculate that proteins tend to be longer among Bacteria in relation to the protected environment of many bacterial species. High temperatures and harsh environmental conditions may have instead favored the evolution of shorter, less complex and more stable proteins in archaeal species. In contrast to the modest length difference between shared proteins, proteins unique to Archaea are substantially (∼59%) shorter than proteins unique to Bacteria. Among the shortest proteins unique to Archaea are many ribosomal proteins, subunits of RNA polymerase, transcriptional regulators and RNA-binding proteins, whereas the longest archaeal-unique proteins function in DNA replication and protein turnover. Among Bacteria, the shortest unique proteins also include ribosomal proteins, but the majority are proteins contributing in cell envelope biogenesis, carbohydrate transport, cell motility and secretion, signal transduction mechanisms, amino acid transport and metabolism and ion transport and metabolism.

We cannot account for the length difference between proteins unique to Bacteria or Archaea on the basis of environmental temperature. In fact, unique sequences tend to be longer in Bacteria also when comparing only thermophiles or only mesophiles. Functional and structural constraints limit protein adaptation to different environments. In particular, the divergence of homologous proteins with respect to bacterial and archaeal lineages must have been constrained by the functionality achieved in their common ancestor. The modest length differences that we observe among most protein groups shared by Bacteria and Archaea may reflect such constraints. In contrast, proteins that are present only in Bacteria or in Archaea have evolved their functionality (or have survived) in only one of the two evolutionary groups. The length difference that we observe between proteins unique to Bacteria or Archaea may relate to unconstrained adaptations to different bacterial or archaeal conditions.

Among the prokaryotic species in our collection, archaeal species are free-living, mostly in extreme environments, whereas bacterial species are adapted to a wide variety of ecological conditions and include endocellular parasites, obligate and facultative parasites of animals and plants, and species that spend different proportions of their life-cycle in free-environments (aqueous or terrestrial) where they are subject to stresses of a variable nature and amplitude. Small proteomes of parasitic organisms, such as Mycoplasma and Chlamydia, that live in a protected environment seem to have longer median proteins than most other species. Also, proteins tend to be longer in the obligate intracellular parasite Rickettsia prowazekii, but not in its close relative Rickettsia conorii. Long proteins also characterize Gram-positive Actinobacteria (high G+C Gram-positives), whereas short proteins are predominant in all Firmicutes (low G + C Gram-positives) except Mycoplasmas (Mollicutes). Different groups of Proteobacteria exhibit great protein length variability.

Factors other than growth temperature are likely to influence the median protein length among Prokaryotes and may underlie its great variability particularly among bacterial species. Less complex and more stable proteins can be expected among free-living species exposed to more intense stresses and environmental fluctuations. It has also been suggested that minimization of costs related to amino acid usages is a significant force in protein evolution (24,25). Minimization of the length of proteins can be an effective mechanism to reduce their cost. In this respect, a selective pressure for shorter, less expensive proteins would be more intense among those species that are likely to encounter starving conditions (e.g. free-living species versus parasites). Finally, a propensity toward longer proteins in Bacteria may be a consequence of the phenomenon of genome reduction among bacterial obligate parasites. Genes of low expression and poorly conserved are likely to be eliminated from the genomes of obligate parasites when under no or weak selection (26). Consequently, the proteomes of these species would be enriched in longer conserved proteins of fundamental function (9).

Our findings indicate that the differences in protein length between Eukaryotes, Bacteria and Archaea are biologically meaningful. They suggest that proteins present in Prokaryotes as single units have often fused in Eukaryotes into multi-domain units. Among Prokaryotes, extreme environmental conditions may account for the shorter length of archaeal proteins compared with their bacterial orthologs, through loop and terminal element deletions and a tendency among Archaea to evolve less complex single-domain proteins. There is a greater variability in median protein length between sequenced bacterial species than between archaeal species. This variability may reflect the diversity of the bacterial ecological adaptations, ranging from free-living in extreme environments to endoparasitic life-styles. The precise relation of protein length with environmental conditions is likely to be complex and remains to be explored.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant 2 RO1 GM010452. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by NIH Grant 2 RO1 GM010452.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Galperin M.Y., Tatusov R.L., Koonin E.V. In: Organization of the Prokaryotic Genome. Charlebois R.L., editor. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J. Protein-length distributions for the three domains of life. Trends Genet. 2000;16:107–109. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01922-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang P., Riley M. A comparative genomics approach for studying ancestral proteins and evolution. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2001;50:39–72. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(01)50003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skovgaard M., Jensen L.J., Brunak S., Ussery D., Krogh A. On the total number of genes and their length distribution in complete microbial genomes. Trends Genet. 2001;17:425–428. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02372-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karlin S., Brocchieri L., Trent J., Blaisdell B.E., Mrazek J. Heterogeneity of genome and proteome content in bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2002;61:367–390. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.2002.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tekaia F., Yeramian E., Dujon B. Amino acid composition of genomes, lifestyles of organisms, and evolutionary trends: a global picture with correspondence analysis. Gene. 2002;297:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung Y.J., Krueger C., Metzgar D., Saier M.H., Jr Size comparisons among integral membrane transport protein homologues in bacteria, Archaea, and Eucarya. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:1012–1021. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.1012-1021.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das S., Yu L., Gaitatzes C., Rogers R., Freeman J., Bienkowska J., Adams R.M., Smith T.F., Lindelien J. Biology's new Rosetta stone. Nature. 1997;385:29–30. doi: 10.1038/385029a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipman D.J., Souvorov A., Koonin E.V., Pachenko A.R. The relationship of protein conservation and sequence length. BMC Evol. Biol. 2002;2:20–29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mira A., Klasson L., Andersson S.G. Microbial genome evolution: sources of variability. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2002;5:506–512. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochman H. Distinguishing the ORFs from the ELFs: short bacterial genes and the annotation of genomes. Trends Genet. 2002;18:335–337. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubbard T., Barker D., Birney E., Cameron G., Chen Y., Clark L., Cox T., Cuff J., Curwen V., Down T., et al. The Ensembl genome database project. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:38–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatusov R.L., Koonin E.V., Lipman D.J. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tatusov R.L., Natale D.A., Garkavtsev I.V., Tatusova T.A., Shankavaram U.T., Rao B.S., Kiryutin B., Galperin M.Y., Fedorova N.D., Koonin E.V. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bateman A., Birney E., Cerruti L., Durbin R., Etwiller L., Eddy S.R., Griffiths-Jones S., Howe K.L., Marshall M., Sonnhammer E.L. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:276–280. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bateman A., Birney E., Durbin R., Eddy S.R., Howe K.L., Sonnhammer E.L. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:263–266. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bateman A., Coin L., Durbin R., Finn R.D., Hollich V., Griffiths-Jones S., Khanna A., Marshall M., Moxon S., Sonnhammer E.L., et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagi A.D., Regan L. An inverse correlation between loop length and stability in a four-helix-bundle protein. Fold. Des. 1997;2:67–75. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(97)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell R.J., Ferguson J.M., Hough D.W., Danson M.J., Taylor G.L. The crystal structure of citrate synthase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus at 1.9 Å resolution. Biochemistry. 1997;36:9983–9994. doi: 10.1021/bi9705321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson M.J., Eisenberg D. Transproteomic evidence of a loop-deletion mechanism for enhancing protein thermostability. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;290:595–604. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakravarty S., Varadarajan R. Elucidation of determinants of protein stability through genome sequence analysis. FEBS Lett. 2000;470:65–69. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar S., Nussinov R. How do thermophilic proteins deal with heat? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001;58:1216–1233. doi: 10.1007/PL00000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vieille C., Zeikus G.J. Hyperthermophilic enzymes: sources, uses, and molecular mechanisms for thermostability. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2001;65:1–43. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.1.1-43.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akashi H., Gojobori T. Metabolic efficiency and amino acid composition in the proteomes of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3695–3700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062526999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seligmann H. Cost-minimization of amino acid usage. J. Mol. Evol. 2003;56:151–161. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2388-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haigh J. The accumulation of deleterious genes in a population—Muller's Ratchet. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1978;14:251–267. doi: 10.1016/0040-5809(78)90027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.