Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by Chlamydia trachomatis serotypes L1, L2 and L3. Unlike other serotypes (A to K), those that cause LGV are invasive and preferentially target lymph tissue. LGV can be transmitted through vaginal, anal or oral sexual contact and can be prevented through the use of condoms or other barrier methods.

LGV infection begins with a small, painless lesion (which may go unnoticed) and can progress to painful enlargement of local lymph nodes, which may coalesce to form a bubo.1 If the infection is left untreated, lymphatic obstruction may result, which can lead to serious complications, such as destruction of the genitals or rectum (including rectal stricture), and can uncommonly lead to meningoencephalitis, hepatitis and death. As with other STIs, the presence of LGV increases the risk for acquisition and transmission of HIV infection, other STIs and other conditions caused by bloodborne pathogens, such as hepatitis C.

Until recently, LGV was rare in industrialized countries, although it is endemic in parts of Africa, Asia, South America and the Caribbean.2 However, cases in men having sex with men have been reported recently in Europe (starting in 2003 in the Netherlands, and additional cases being reported from Belgium, France, Germany, Sweden and Britain); cases have also been reported recently from the United States. These cases have been associated with concurrent HIV infection and hepatitis C, sex parties and higher-risk sexual activities (e.g., “fisting”).3

C. trachomatis infection is reportable in all provinces and territories in Canada, but only some provinces break down their surveillance data into cases caused by LGV serotypes and those caused by non-LGV serotypes. To monitor LGV in this country, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) has established a national surveillance system for LGV in partnership with the provinces and territories, which began in February 2005. The surveillance protocol, case definition and recommended treatment will be available as of June 5, 2005, at www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/std-mts.

Epidemiologic features

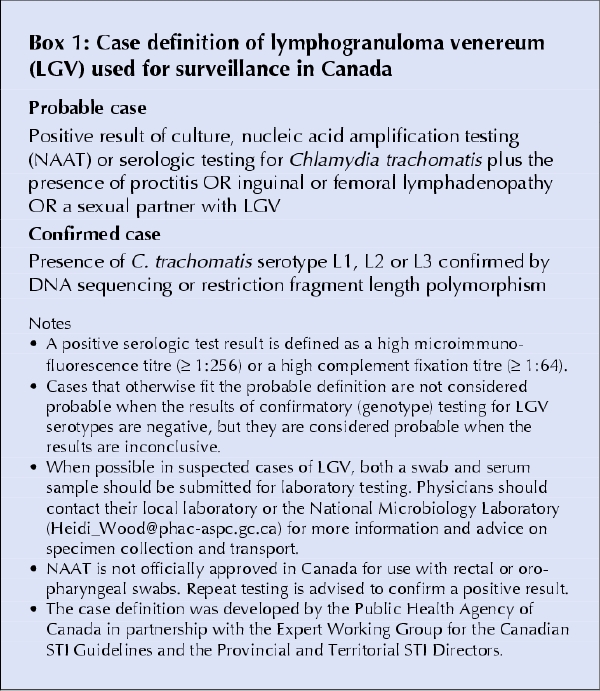

Box 1 presents the case definition used in Canada for national surveillance. Because culture and nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) do not distinguish between LGV and non-LGV serotypes, and because a high microimmunofluorescence titre (≥ 1:256) or a high complement fixation titre (≥ 1:64) only suggests LGV, a positive result with one of these methods requires confirmation with an LGV-specific test (restriction fragment length polymorphism or DNA sequencing).

Box 1.

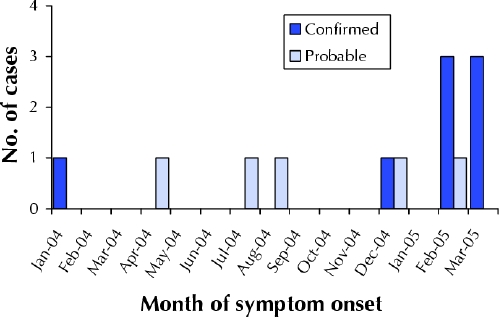

As of May 13, 2005, 22 LGV cases had been reported to the PHAC; 6 were probable and 16 confirmed according to the case definition. All genotyped strains of C. trachomatis were L2b, similar to the outbreak strain in the Netherlands. Of the 13 cases for which the date of symptom onset was known, the earliest onset was in January 2004 and the most recent on Mar. 21, 2005 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Epidemic curve of the 13 cases in Canada of lymphogranuloma venereum reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada for which the date of symptom onset was known.

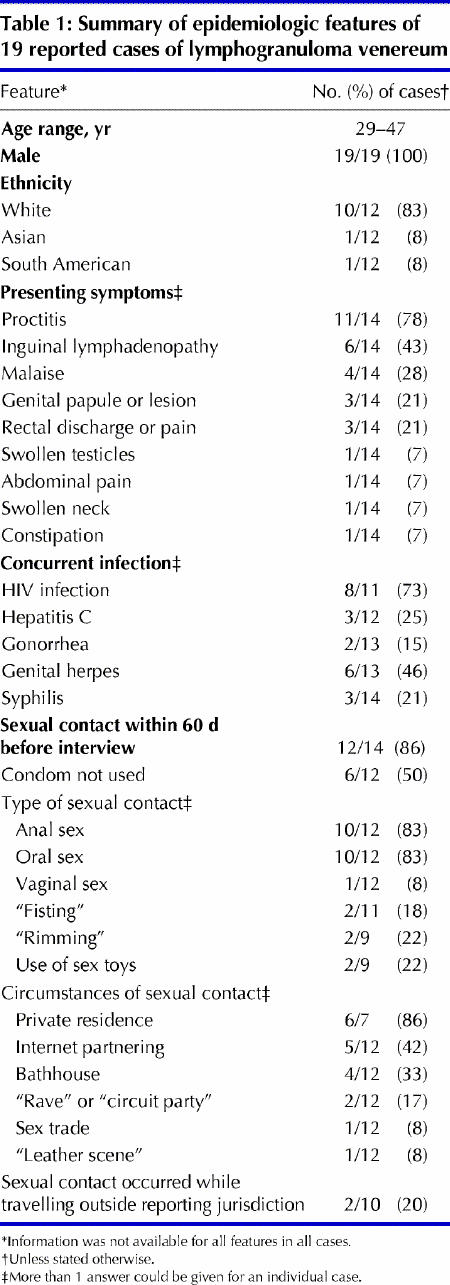

Epidemiologic data were available for 19 of the cases (Table 1). The cases appear to be unlinked. All 19 cases were among men. Proctitis and inguinal lymphadenopathy were the most common presenting symptoms. Of the 8 patients concurrently infected with HIV, 3 also had hepatitis C; for only 1 of these 3 men was historical information available on behaviour placing the patient at increased risk of hepatitis C (sharing injection drug equipment, fisting and rectal use of methamphetamine in the 60 days before interview).

Table 1

Of the 19 men, 12 reported having had sexual contact in the 60 days before their interview, 10 with male partners only (1–16 partners) and 1 with female partners only (2 partners); the remaining patient did not disclose partner information. Most often (in 6 [86%] of the 7 cases for which this information was available), sexual contact occurred in a private residence; bathhouse contact was reported by 4 men (33% of the 12) and finding partners on the Internet by 5 men (42% of the 12). None of the men reported having a sexual partner with known LGV. Although 2 of the men reported having had sex while travelling within Canada in the 60 days before their interview, none reported having had sex while travelling outside of Canada in this time frame.

Controlling transmission

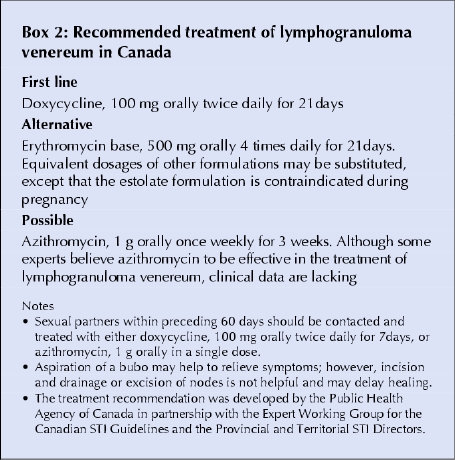

Efforts to control the transmission of LGV include prevention, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of the patient and sexual partners (Box 2). Diagnosis, often based on history and the clinical picture, can be difficult, given that the symptoms overlap with those of other STIs and other infections or conditions. Specialized testing for LGV can assist in diagnosis; whenever possible in suspected cases, both a swab (for culture or NAAT) and serum sample (for microimmunofluorescence or complement fixation testing) should be submitted. Some local laboratories are able to test specifically for LGV, whereas others would need to involve the National Microbiology Laboratory through their provincial laboratory. Physicians should contact their local laboratory or the National Microbiology Laboratory (Heidi_Wood@phac-aspc.gc.ca) for more information on collection, transport and testing of specimens.

Box 2.

In suspected cases, empiric treatment should be given for LGV (and for gonorrhea when clinically indicated) while the test results are awaited. Counselling and testing for other STIs, including HIV infection, hepatitis B and hepatitis C, are also recommended in such cases, given the rates of concurrent infection.

Cases of LGV should be reported to local health authorities. Currently in Canada, LGV appears to be primarily occurring among men having sex with men, a high proportion of whom have concurrent HIV infection, other STIs or hepatitis C. LGV is an emerging and significant public health concern.

Rhonda Y. Kropp Senior Public Health Analyst Sexual Health and Sexually Transmitted Infections Section Thomas Wong Director Community Acquired Infections Division Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Public Health Agency of Canada Ottawa, Ont. On behalf of the Canadian LGV Working Group

Acknowledgments

We thank the following members of the Canadian LGV Working Group for their critical involvement in both the collection of the enhanced surveillance data and the review and revision of the manuscript: Maritia Gully, Hugh Jones, Grant McClarty, Janice Mann, Gina Ogilvie, Frank Plummer, Michael Rekart, Lorraine Schiedel, Susanne Shields, Ameeta Singh, Marie Carole Toussaint, Sylvie Venne and Heidi Wood.

Footnotes

Fast-tracked article. Published at www.cmaj.ca on May 31, 2005.

References

- 1.Weir E. Lymphogranuloma venereum in the differential diagnosis of proctitis. CMAJ 2005;172(2):185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Bauwens JE, Orlander H, Gomez MP, Lampe M, Morse S, Stamm WE, et al. Epidemic lymphogranuloma venereum during epidemics of crack cocaine use and HIV infection in the Bahamas. Sex Transm Dis 2002;29:253-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gotz H, Nieuwenhuis R, Ossewaarde T, Bing Thio H, van der Meijden W, Dees J, et al. Preliminary report of an outbreak of lymphogranuloma venereum in homosexual men in the Netherlands, with implications for other countries in western Europe. Eurosurv Wkly 2004;8(4). Available: www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2004/040122.asp#1 (accessed 2005 May 25).